For more than three decades, Viet Nam has made remarkable economic progress. Active participation in global value chains has brought economic prosperity, but it also makes Viet Nam susceptible to external conditions, which have recently become more uncertain than before. While foreign investment has taken the lead of export-oriented manufacturing, a large number of small businesses play an important role in domestic economic activities. Economic hardship often hits small businesses and poorer households most severely. Moreover, a vast number of people are not yet covered by social security despite the acceleration of population ageing. This chapter discusses the macroeconomic and social impacts of the recent crises, notably the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and their policy implications for achieving robust and inclusive progress in the medium term, including the importance of further trade integration for Viet Nam.

OECD Economic Surveys: Viet Nam 2023

1. Key policy insights

Abstract

Viet Nam should aim at not only high but also sustained post-pandemic growth

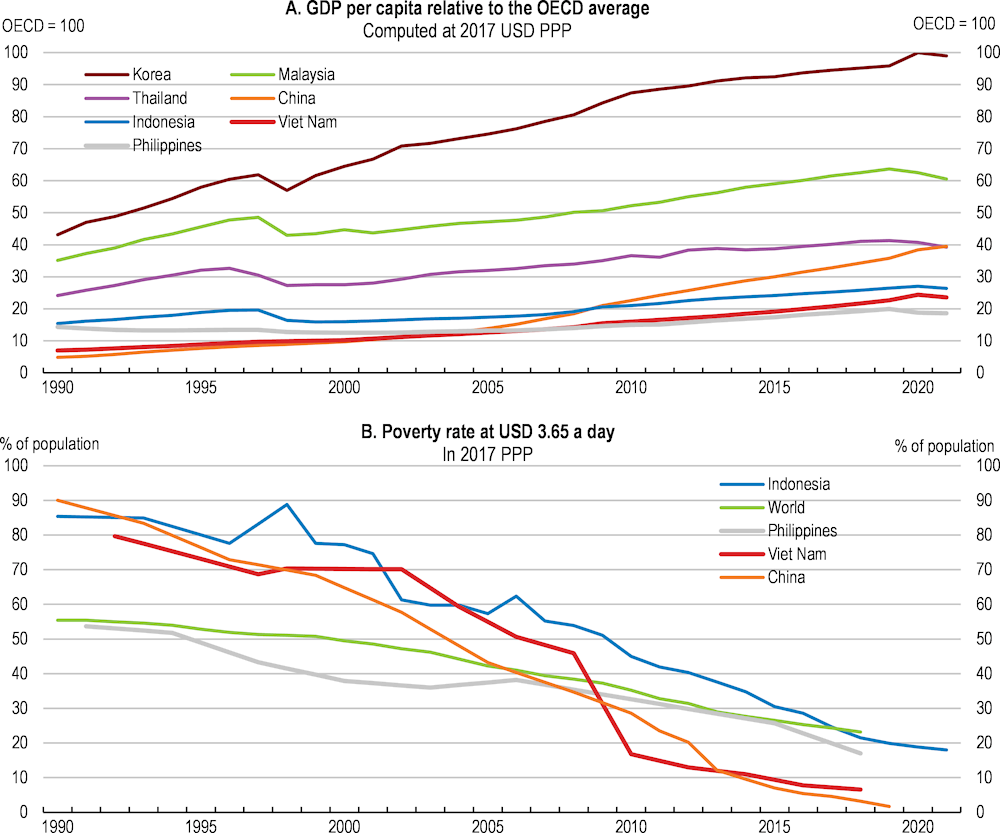

Viet Nam has performed impressively over recent decades. A bold policy package of market-oriented reforms, known as Doi Moi, started in 1986 and unleashed Viet Nam’s economic potential. Between 1990 and 2019, real GDP growth was strong, averaging 6.8%. Moreover, the economy proved resilient to a series of shocks. While many other Southeast Asian countries experienced severe recessions during the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997-1998 and the Global Financial Crisis in 2008-2009, the Vietnamese economy continued to grow. Robust growth has been underpinned by a sustained transition from an agrarian to an industrial economy: the share of agriculture in GDP declined from around 40% in the late 1980s to nearly 10% in 2020, although Viet Nam remains one of the largest rice exporters in the world. Together with abundant labour supply, greater trade openness attracted foreign investors, accelerating this economic transformation. The trade to GDP ratio, which was just 23% in 1986, is now almost 200%, one of the highest in the world. In addition to becoming a member of ASEAN (1995) and APEC (1998), accession to the WTO in 2007 further strengthened Viet Nam’s integration into the global economy. The share of ICT goods in total merchandise exports rose from 5% in 2007 to nearly 40% in 2020. As a result, Viet Nam attained middle-income country status in 2010. Per capita GDP reached 20% of the OECD average by end-2020, up from around 8% in 2000 (Figure 1.1, Panel A). The Vietnamese people benefitted considerably from this sustained period of high economic growth, as is shown by the dramatic decline in the poverty rate (Figure 1.1, Panel B).

In recent years, while navigating the health and economic impacts of the pandemic, Viet Nam has kept its long-term aspiration to attain high economic prosperity for the people. In particular, trade integration has gained stronger momentum (OECD, 2020[1]). Following the enactment of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership in 2019, a large-scale free trade agreement across the Asia-Pacific, Viet Nam ratified the European Union-Viet Nam Free Trade Agreement and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership during the pandemic. A number of necessary domestic reforms have already kicked off, such as the revised Enterprise Law to re-classify state-owned enterprises and the new Labour Code that will enhance workers’ rights. Moreover, building on the past experience of crisis management, tackling the pandemic has been highly successful so far, with Viet Nam achieving both lower COVID-19 mortality per capita than most other OECD countries and positive economic growth in 2020 (2.9%) and 2021 (2.6%). Similar to many other countries, the government mobilised a range of available monetary and fiscal policy tools, notably tax deferrals, tax cuts, loan restructuring and soft loans, to mitigate impacts on vulnerable households and businesses.

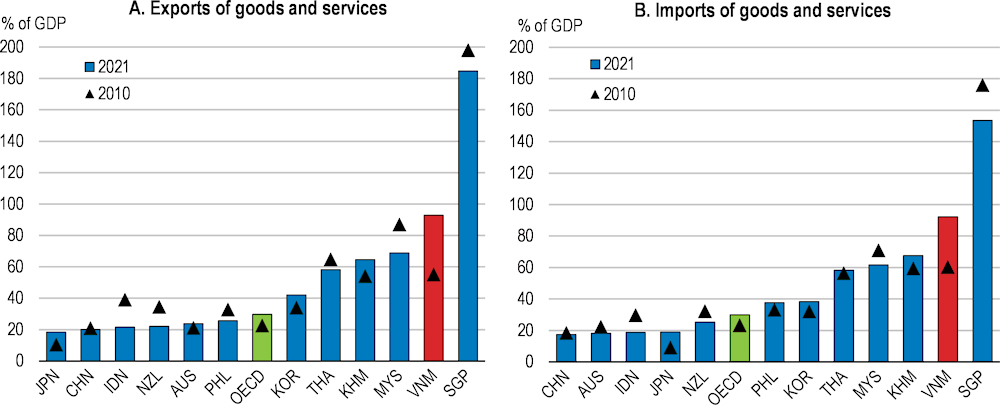

The government’s plans are detailed in the 10‑year Socio-Economic Development Strategy 2021‑2030 and the 5‑year Socio-Economic Development Plan 2021‑2025 and have a strong focus on achieving a more productive, inclusive and greener economy (Box 1.1). While the income gap compared with the OECD average is still large, Viet Nam also needs to prepare for significant population ageing. Despite rapid economic development, economic informality is high, and social protection is underdeveloped. Even before the pandemic, the expansion of Viet Nam’s international trade through opening markets faced a risk of weakening amid growing trade tensions. Moreover, the highly uncertain global environment that has arisen with the outbreak of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has added additional headwinds to the Vietnamese economy. High energy prices are pushing up inflation, eroding the purchasing power of vulnerable households. Global trade may be undermined for a long period as a consequence of the war. Nevertheless, the government aims for an ambitious average GDP growth rate of 7% by 2030 to attain upper middle-income country status.

To achieve this, the ongoing recovery will need to be followed by robust growth that is underpinned by higher labour productivity growth. In particular, the rapidly changing external as well as domestic environment has caused the government to reframe the Vietnamese model of growth. In particular, the Prime Minister has underscored the importance of “building a resilient and strategically autonomic economy while pursuing proactive international integration” (Harvard Kennedy School, Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, 2022[2]). In particular, strengthening trade integration is key to economic stability. Further trade integration will continue to benefit Viet Nam as before, but the integration will be deepened if trading partners are more diversified and exported products, including services, have a higher share of value added. A dynamic business sector will be the main driver of this economic transformation. Therefore, improvements to the business climate for both domestic and foreign investors will become increasingly crucial. Among other things, this will require the further diffusion of digital technologies. In order to improve resilience to economic shocks and to realise the smooth implementation of bold reforms, a sounder macroeconomic policy framework and a more comprehensive social protection system will be needed. At the same time, structural reforms, such as financial market reform, can also help stabilise macroeconomic conditions and enhance economic resilience.

Bold structural reforms are also crucial to ensure a robust recovery in the wake of the COVID pandemic and to avoid the “middle-income trap”. Latin American countries experienced a long period of economic stagnation during the 1980s (i.e. the “lost decade”). These countries accumulated large amounts of external borrowing during the 1970s period of high oil prices. When the global economy subsequently entered a recession amid rising policy rates in advanced economies, this triggered a debt crisis. In response, governments in the region cut public spending such as on infrastructure and social benefits. However, less attention was paid to supply-side reforms to stimulate business dynamism. Despite strong fiscal consolidation, government subsidies to state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in these countries were not reduced. It was not until the early 1990s when privatisation of SOEs accelerated across the region. While Viet Nam’s economic growth has been strong, a number of emerging-market economies have been faced with slowing growth when they have reached middle-income status (Felipe, 2012[3]). Rising income levels make labour-intensive manufacturing exports less competitive, while nurturing high value-added sectors requires extensive structural reforms, notably deepening trade integration, reducing regulatory burdens on businesses, investing in human capital and combatting corruption (Tran, 2013[4]). These broad reforms require huge policy efforts, underpinned by high institutional capacity of governments. Viet Nam has successfully implemented bold reforms in the past, such as Doi Moi, but step-by-step reform, which allows the government to concentrate its limited resources on difficult reform areas, will ensure sustained economic convergence.

The Socio-Economic Development Strategy 2021-2030 set out a new policy orientation of a “circular economy”, where all policies should be consistent with greener growth. In addition to this, a commitment to achieving net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 is bringing the climate transition into new focus. A Decision issued in July 2022 (896/QD-TTg) aims at mapping out a comprehensive climate change strategy, including more concrete policy directions to realise net zero emissions. The increase in energy prices as a result of the war in Ukraine has compounded the need for reducing the country’s reliance on fossil fuels, through accelerating the adoption of renewables, improving energy efficiency and raising the utilisation of other low carbon energy sources. The large investments needed to achieve the green transition require additional financial resources. Strong carbon reduction commitments, accompanied by the policy settings needed to achieve them, can help attract more funding for these projects, including from international sources. The further successful adoption of renewable energy sources can also attract more sophisticated FDI which is sensitive to total carbon footprints and thus promotes energy efficiency, producing a virtuous cycle to help decarbonise the domestic economy.

Against this backdrop, the main messages of this Economic Survey are:

Macroeconomic policies need to help enhance economic resilience. In the short run, the priority is to minimise the impact of high energy prices through targeted support for vulnerable households, rather than deploying further expansionary fiscal measures. In the medium term, it is crucial to strengthen the macroeconomic policy framework by improving fiscal sustainability through expanding the tax base. Social protection also needs to be strengthened and economic informality reduced.

To maintain high economic growth from the recovery, Viet Nam needs to further improve the business climate and facilitate the digital transformation. Reinvigorating business dynamism requires further streamlining regulations, increasing the transparency of regulatory processes and levelling the playing field among all market participants, including between state-owned enterprises and private entities.

To achieve the objective of reaching net zero emissions by 2050, sustaining high levels of investment in renewable energy and pursuing greater energy efficiency will be needed. This can be achieved through a comprehensive policy approach that prioritises effective public and private investment, conducive regulatory settings and market prices that better reflect carbon content.

Figure 1.1. Viet Nam's people benefitted from its uninterrupted economic progress

Box 1.1. Viet Nam’s political and economic system – a socialist-oriented market economy

Viet Nam’s political system consists of the Communist Party of Viet Nam, the State of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, socio-political organisations, socio-professional organisations and mass associations.

As a socialist country, the Communist Party of Viet Nam is the ruling and only legal political party in Viet Nam, which is stipulated in the Constitution as the “vanguard of the working class” and “the leading force for the State and society”.

The National Assembly is considered the highest level representative body of the people, the highest state power body of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam and the sole organ that has the constitutional and legislative rights and exercises the supreme power of supervision over all activities of the State. It has only one chamber.

The Government is the supreme administrative agency of the State and an executive body of the National Assembly. It consists of the Prime Minister, Deputy Prime Ministers, Ministers and Heads of ministerial-level agencies. The Prime Minister is the head of the Government and is elected by the National Assembly. Ministers are proposed by the Prime Minister and approved by the National Assembly. The Supreme People’s Court is also responsible to the National Assembly. The Chief of Justice is appointed by the National Assembly and judges are appointed by a selection committee headed by the Chief of Justice.

The Party Secretary, the President, the Prime Minister and the Chairperson of the National Assembly are considered the top leaders of Viet Nam. The President and the Chairperson of the National Assembly are elected by the National Assembly from its members. The President is the Head of State representing the nation.

Local governments consist of a People’s Council and a People’s Committee that are organised for each administrative unit. The members of People’s Councils are elected by the people. Delegation of powers to each level of local governments must be stipulated by laws. Each province and district also has its own Court.

Viet Nam is a socialist-oriented market economy. Although the State manages the economy through legislation, planning and policies, individual persons and organisations can conduct commercial activities unless laws forbid these activities. Land is possessed by the State but individuals can acquire the land use right from the State. Non-land properties owned by individuals are not nationalised. The State can purchase them at a market price in case it is necessary for specific reasons, such as national defence and development.

Macroeconomic policy should be gradually normalised

The economy showed resilience during the pandemic, but new challenges have arisen

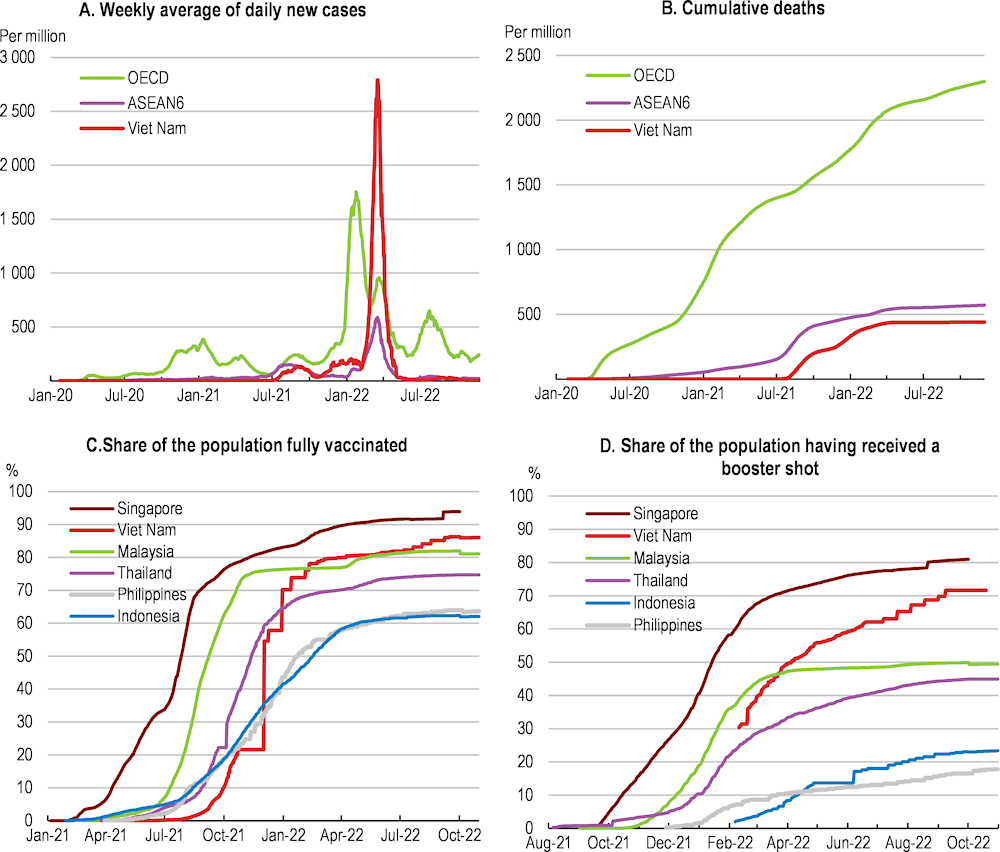

Overall, Viet Nam has withstood the economic shocks entailed by the pandemic well. This has owed a lot to the flexible but bold handling of the health crisis. Viet Nam succeeded in avoiding large infections until mid-2021 thanks to swift border closures and tight but short-lived confinement measures that were targeted at infected areas early in 2020 (Figure 1.2, Panels A and B). More stringent restrictions in response to the abrupt propagation of the Delta variant caused real GDP to decline in the third quarter of 2021. Nevertheless, the restrictions were quickly eased, in consideration of the serious economic and social ramifications of these measures. Vaccination started more slowly than in other Southeast Asian countries in 2021, but progressed rapidly (Figure 1.2, Panel C). The government set a target of fully vaccinating at least half of the population aged 18 and older by end-2021. By early January 2022, 70% of the population had been administered two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine, marking a much faster rollout than initially planned. From early 2022, the government further stepped up its living-with-COVID amidst the circulation of the Omicron variant, which was considered to be more contagious but typically less harmful. This has been accompanied by a rapid increase in the share of the population that has received a booster shot (Figure 1.2, Panel D). These measures helped contain the pandemic and revive the economy.

Figure 1.2. Viet Nam has managed the public health crisis well

Note: ASEAN6 is the population-weighted average of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. OECD is also population-weighted.

Source: Our World in Data, available at https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations.

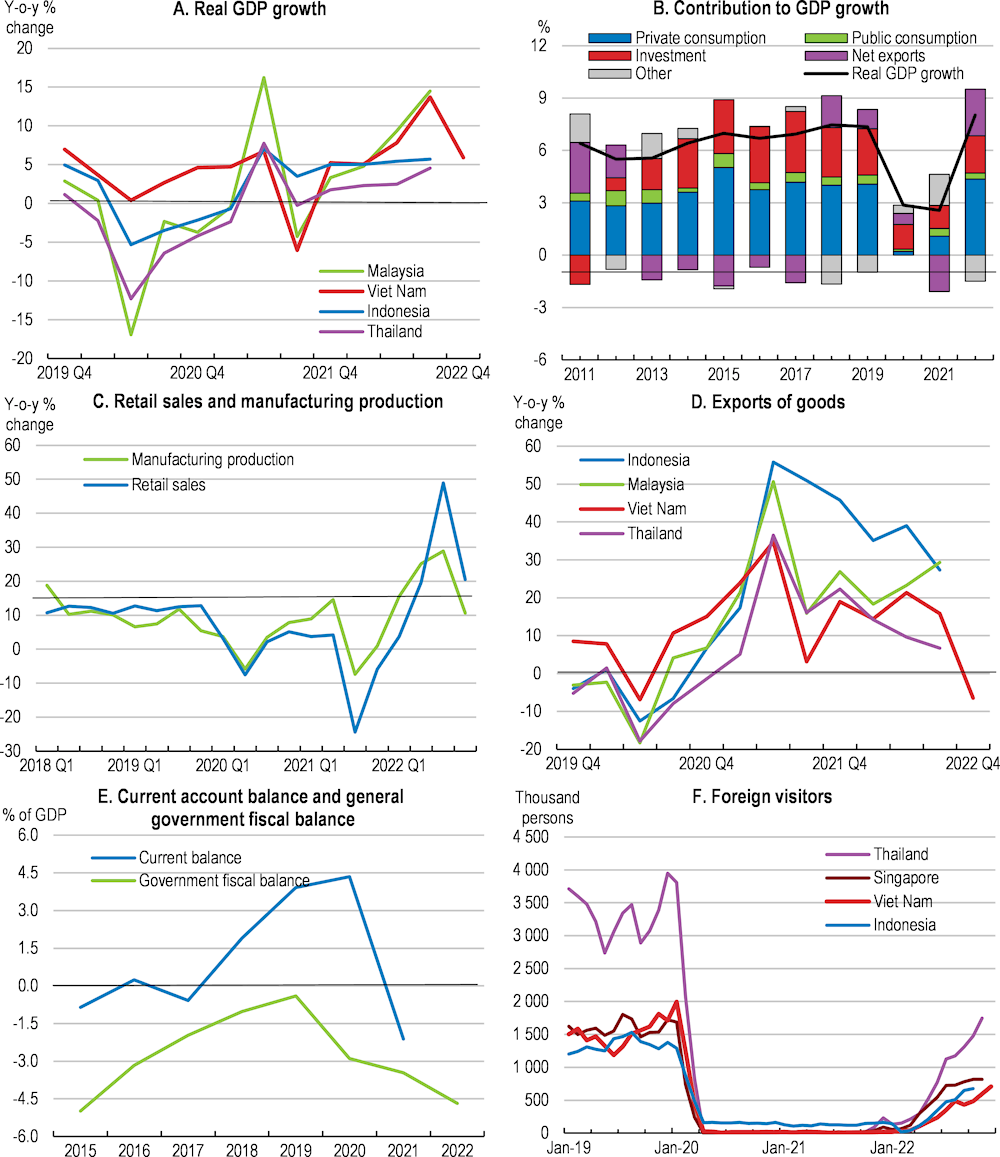

Figure 1.3. Recent macroeconomic developments

Note: In panel B, “Other” covers the change in stocks and the statistical discrepancy.

Source: CEIC and GSO.

Recent economic developments in Viet Nam are taking place against a backdrop of slowing global economic growth. Global industrial production and retail sales have been declining and survey evidence suggests notably weaker business and consumer confidence in most OECD countries. Inflation has risen steeply, reflecting a combination of factors. These include the impact of the war on energy and food prices, ongoing supply constraints and a solid global demand recovery following the onset of the pandemic. Higher prices are eroding household purchasing power and have prompted central banks around the world to raise official interest rates, weighing on investment activity. Looking forward, the OECD projects global GDP growth to slow sharply this year to 3.1%, around 1½ percentage points weaker than projected as at December 2021, and to remain weak at 2.2% in 2023.

Growth in Viet Nam has been robust since early 2020, apart from the contraction in the third quarter of 2021 (Figure 1.3, Panel A). Domestic demand has been particularly solid overall. Private consumption flattened in 2020, but did not plunge like in many other countries, and then picked up quickly in 2021 (Figure 1.3, Panel B). Retail sales data indicate that consumption continued rebounding strongly in the first half of 2022 after the huge contraction in the third quarter of 2021 (Figure 1.3, Panel C). Investment has buttressed growth. Viet Nam’s low infection rates have contributed to better business prospects for foreign investors. As a result, foreign investment (realised capital) already started increasing in the first half of 2022 (10% in January-July, year-on-year basis, in US dollar (USD) terms) following a small decline in 2020 and 2021 (-2% and -1%). Business activity has also been resilient, with industrial production recovering steadily from late 2021 (Figure 1.3, Panel C).

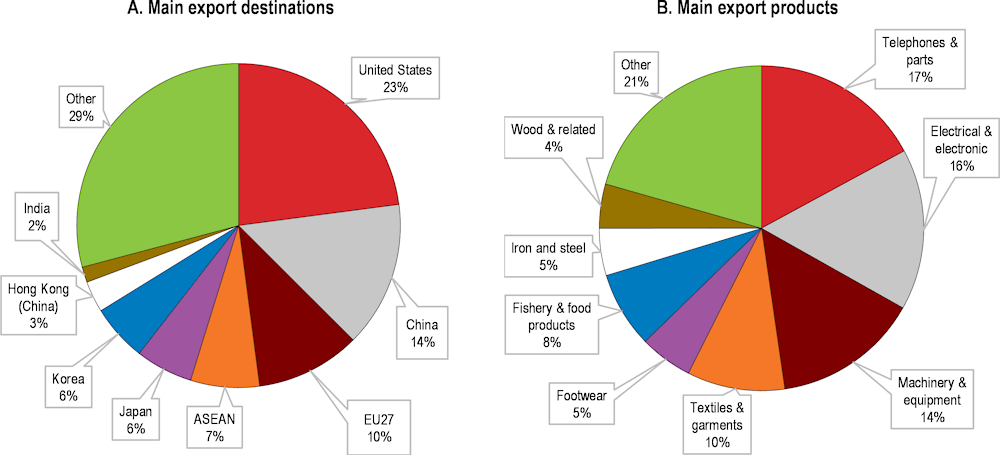

Figure 1.4. Exports by destination and product

Share of total exports, 2021

On the other hand, the contribution of external demand to growth was mixed. Overall, Viet Nam’s goods exports have been buoyant like in other Southeast Asian countries during the pandemic (Figure 1.3, Panel D). Exports to the United States and People’s Republic of China (hereafter China), which account for the largest share in Viet Nam’s exports (Figure 1.4), have been solid. Viet Nam imports a large amount of machinery and equipment, meaning that real imports tend to grow faster than real exports when the economy is expanding because of stronger investment demand, and vice versa (Figure 1.3, Panel B). As such, net exports contributed positively to GDP growth in 2020 amid softening investment. Volume of trade expanded strongly in the first half of 2021, but was affected in the second half of the year by the tougher sanitary restrictions and global supply chain disruptions, with exports slowing more than imports. Accordingly, the current account balance recorded deficits in 2021 (Figure 1.3, Panel E). Although it accounts for a smaller share than in other Southeast Asian countries, inbound tourism to Viet Nam grew fast before the pandemic. As the government reopened borders to most countries from April 2022, after almost two years of shutdown, the number of overseas visitors has gradually increased but still remains at very low levels (Figure 1.3, Panel F).

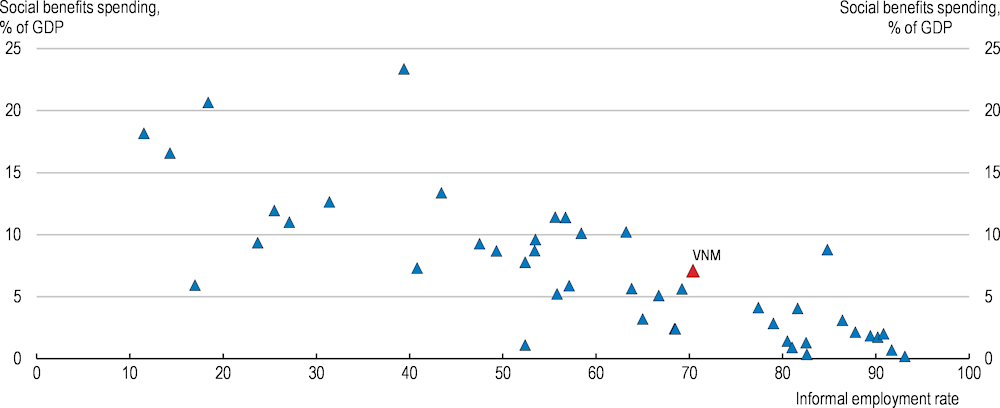

The external environment has become more uncertain since the beginning of 2022. Viet Nam has significantly expanded its participation in global trade over recent decades (Figure 1.5), which has contributed to its rapid economic development. Involvement in global supply chains promotes efficient use of economic resources and the adoption of new technologies through foreign investment. While over-stretched supply chains could be susceptible to shocks, Viet Nam’s expansion of trade has diversified both the composition of trading partners as well as the goods and services in trades. Viet Nam’s highly trade-dependent economy is thus not necessarily more vulnerable to external shocks. Nevertheless, recent unprecedented developments, notably the ongoing global pandemic and war in Ukraine, do pose additional challenges for the Vietnamese economy.

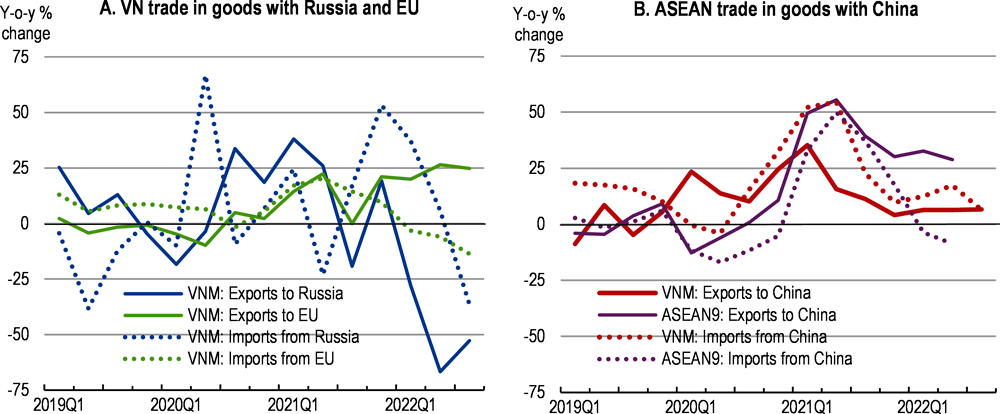

The war in Ukraine may affect Viet Nam’s economy through various channels, although the direct impact is limited. Trade with Russia and Ukraine is small (respectively, 0.9% and 0.1% of total goods trade in 2019), but bilateral imports of certain products are relatively important, such as coal and coal products (12% of total imports of coal and coal products were from Russia in 2021) and fertilisers (10% of total imports of fertilisers were from Russia in 2021). Exports to Russia declined sharply from March 2022 due to supply chain disruptions (Figure 1.6, Panel A). For a few agricultural products, Russia accounts for a material share of exports (for example, 5% of total exports of “coffee, tea, mate and spices” in 2021). Nevertheless, Russia’s share in Viet Nam’s total exports is small (1% of total goods exports in 2021). On the other hand, Viet Nam is one of the most popular ASEAN destinations for Russian tourists, second to Thailand (Russians accounted for 3.6% of total foreign visitors to Viet Nam in 2019).

A slowdown in the European economies would have a more significant impact on the Vietnamese economy (Figure 1.6, Panel A). Despite their declining share, European countries are important counterparts for Viet Nam’s trade (The EU’s share in goods trade was 17% in 2021). Nonetheless, the European Union–Viet Nam Free Trade Agreement, a preferential trade agreement effective from 2020, should help re-boost bilateral trade once the situation improves. Indirect impacts from the war are also being felt through rising price pressures. Already, high energy and commodity prices are putting upward pressure on inflation (Box 1.2).

Figure 1.5. Viet Nam has benefitted from active participation in global trade

Source: OECD, Economic Outlook database; World Bank, World Development Indicators database; CEIC.

Figure 1.6. Viet Nam has diverse and dynamic trade markets

China’s stringent pandemic controls have affected regional trade, but the impact on the Vietnamese economy was relatively limited. Amid the rapid propagation of the Omicron variant, China intensified its sanitary restrictions since end-2021. This included a severe lockdown from late March 2022 to end-May 2022 in Shanghai, which has the world’s largest container port. Direct impacts on trade differ between ASEAN countries depending on the composition and pattern of trade (Figure 1.6, Panel B). Some countries, in particular commodity exporting countries, maintained strong export growth in the first quarter of 2022 partly due to high prices (63% (year-on-year) for Indonesia and 28% for Malaysia). Other countries experienced softening export growth (4% in May for Thailand, following -7% in April and 4% in the first quarter of 2022). Exports rose 8% in Viet Nam both in the first and second quarter of 2022, after 4% in the fourth quarter of 2021. While some goods imports from China, which are crucial for Viet Nam’s manufacturing, such as machinery, equipment and parts, temporarily dropped (a 15% dip in March 2022 followed by a 7% decline in April and a 1% increase in May), industrial production has been less affected (Figure 1.3, Panel C). Overall, businesses managed their production using existing stocks of materials and alternative trade routes. In December 2021, due to the persistent propagation of the Delta variant in Southeast Asian countries, China tightened border controls, including the land borders with Viet Nam. The restrictions have been eased since then. Land trade accounts for around one quarter of trade between Viet Nam and China.

Nonetheless, further supply chain disruptions stemming from China’s changing public health situation may have a larger impact on Viet Nam than on other Southeast Asian countries. Viet Nam has significantly strengthened trade linkages with China over the past decade. China’s share in Viet Nam’s goods exports increased from 11% to 17% between 2012 and 2021, and from 25% to 33% for goods imports. Viet Nam has the highest share of imports from China among ASEAN-6 countries (the second highest, Indonesia was 29% in 2021). Most goods imports from China consist of machinery, equipment and parts (nearly 20% of total goods imports in 2021), which are important in the production of exported goods. Compared with other Southeast Asian countries, Viet Nam stands out for having deepened value chain linkages with China (Figure 1.8). On the other hand, some sectors would be able to benefit from supply chain disruptions in China if they managed to overcome supply constraints, as they could substitute Chinese exporters. China’s exports of textile and apparel temporarily dropped by 3% (year-on-year) in April-May 2022, while exports from Viet Nam continued growing by 19% in the first five months of 2022. The recently enforced Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a large preferential trade agreement, of which China is a member, should help prop up Viet Nam’s trade once the situation is improved.

Box 1.2. High energy prices may hinder economic growth

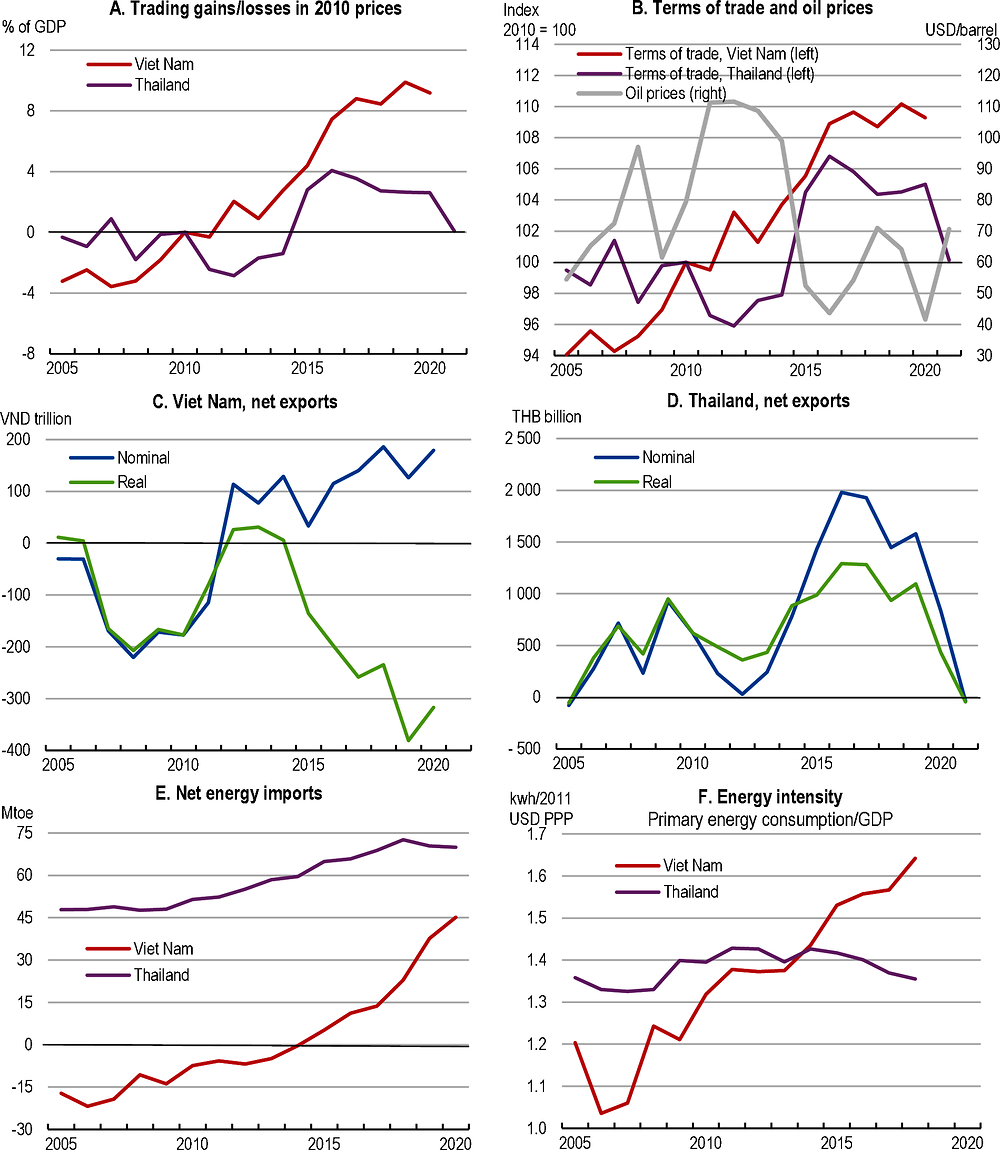

Real GDP represents the volume of goods and services produced or purchased during a certain period, but it does not express a nation’s purchasing power in real terms, when import and export prices change. For example, if export prices rise twofold while other conditions are the same, real GDP does not change, but the purchasing power of that country should improve as the revenue from trade increases. Therefore, in addition to GDP, Gross Domestic Income (GDI) is used to capture the changes in national income (United Nations et al., 2009[6]). Real GDI can be calculated by adding “trading gains/losses” to real GDP1.

Trading gains/losses for Viet Nam increased, particularly from 2015, similar to the experience in Thailand (Figure 1.7, Panel A). The terms of trade, which is the ratio of export and import deflators, improved significantly in both countries after 2014 thanks to declining fossil fuel prices (Figure 1.7, Panel B). Nevertheless, a closer look reveals some differences between these countries.

From the mid-2010s, Viet Nam maintained nominal net exports, but reduced real net exports (Figure 1.7, Panel C)2. On the other hand, Thailand increased nominal net exports, while maintaining real net exports (Figure 1.7, Panel D). This suggests that Viet Nam increased imports of products that became cheaper than in the reference year, while Thailand did not increase the purchase of these products, or Viet Nam reduced exports of products that experienced price increases and Thailand maintained exports of products that became more expensive3.

Indeed, Viet Nam became a net energy importer in 2014 (Figure 1.7, Panel E), and rapidly increased imports of crude oils and coal, while reducing exports of fossil fuels due to declining domestic production. Thailand has been a net energy importer, but the increase was more moderate over the same period (Figure 1.7, Panel E). Both countries improved their national income thanks to low fossil fuel prices, and Viet Nam benefitted from it by increasing its purchases of oil and coal.

Importing fossil fuels was economically appealing when prices were low, but the situation has changed. Rising prices now mean that the cost of fossil fuels in producing one unit of GDP growth has risen. Thus, energy intensity matters. Over the past years, Thailand improved or maintained energy intensity, while Viet Nam did not (Figure 1.7, Panel F). This helped Thailand contain fossil fuel consumption, resulting in only a moderate increase in energy imports in nominal terms. In the same way, improving Viet Nam’s energy efficiency can help reduce costs and achieve the carbon reduction goal of producing net zero emissions by 2050 (see Chapter 2).

1. Trading gain/loss = nominal net exports/numeraire deflator – real net exports. Some different prices could be used as a numeraire deflator. This report uses an average of exports and imports deflators, namely (nominal exports + nominal imports) / (real exports + real imports).

2. Levels of real net exports have no economic meaning, as they are changeable with the level of nominal net exports of the reference year.

3. Viet Nam’s national account uses fixed price index, so that deflators would have upward bias. Nevertheless, this does not affect the main thrust of the discussion in this Box.

Figure 1.7. Improving energy efficiency would help strengthen the resilience against price hikes

Source: CEIC; IEA; and Our World in data (https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/energy-intensity?tab=chart&country=VNM~THA).

Figure 1.8. Viet Nam has deepened value chains with China

Origin of value added in gross manufacturing exports

Note: ASEAN is calculated as a simple average.

Source: OECD, Trade in Value Added database.

Since the onset of the pandemic, the government has adopted a series of stimulus packages to mitigate the anticipated economic impacts (Table 1.1). With its flexible and bold prevention measures for the pandemic, Viet Nam was able to avoid serious outbreaks in 2020. In 2021, following the strict lockdowns and the associated large economic contraction, the government promptly adopted several relief measures for affected households and businesses from July. Although there were some initial implementation issues for some measures, such as cash transfers to poor households, overall additional spending to affected sectors was implemented in an effective and timely manner. The government also employed revenue-side measures, such as reductions and exemptions of taxes and fees, and extensions of tax and land rent payments (tax deferrals). According to IMF estimates, above-the-line measures including additional spending and foregone revenues amounted to 1.8% of GDP by October 2021, as compared to an average of 4.6% across 142 emerging-market and low-income developing economies (IMF Fiscal Affairs Department, 2021[7]). Against this background, in early 2022, the government adopted an additional monetary and fiscal stimulus package, the Socio-Economic Recovery and Development Programme, amounting to 4.1% of GDP, allocating half of it to investment, which was appropriate. Nevertheless, the implementation of large infrastructure projects in the Programme has not yet started. By early September 2022, only 14% of the whole package had been disbursed. Off-budget measures, such as, exemption of utility bills and tuition fees for affected households, a suspension of social contribution payments, and soft loans provided by state-owned banks, also made a large contribution (0.7% of GDP for 2020-2021, excluding soft loans) compared with spending measures.

Table 1.1. Additional fiscal spending was small during the pandemic

Size of stimulus packages, % of GDP

|

|

2020 |

2021 |

2022 and onward |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Implemented |

Implemented |

Planned |

|

Revenue measures |

1.8 |

1.5 |

0.8 |

|

of which extensions of tax and land rent payment |

1.5 |

1.2 |

0.8 |

|

of which reductions and exemptions of taxes, fees and charges |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

|

Spending measures |

0.3 |

1.2 |

2.6 |

|

of which investment |

.. |

.. |

2.1 |

|

Off-budget measures |

.. |

.. |

0.7 |

|

Total |

2.2 |

2.7 |

4.1 |

Source: Ministry of Finance.

Table 1.2. Macroeconomic indicators and projections

Percent changes from previous year unless specified

|

|

2021 |

2022 |

2023 |

2024 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Output and demand |

||||

|

Real GDP |

2.6 |

8.0 |

6.5 |

6.6 |

|

Consumption |

2.3 |

7.2 |

5.8 |

5.8 |

|

Private |

1.9 |

7.8 |

6.3 |

6.4 |

|

Government |

4.7 |

3.6 |

2.5 |

2.3 |

|

Gross fixed investment |

3.7 |

6.0 |

5.0 |

5.3 |

|

Private |

7.8 |

7.3 |

6.0 |

6.3 |

|

Government |

-6.1 |

2.4 |

2.1 |

2.2 |

|

Net changes in inventory (contribution to GDP growth, % point) |

1.8 |

-1.5 |

- |

- |

|

Exports of goods and services |

7.4 |

8.4 |

5.4 |

6.9 |

|

Imports of goods and services |

15.8 |

2.2 |

4.3 |

5.9 |

|

Net exports (contribution to GDP growth, % point) |

-2.1 |

2.7 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

|

Inflation and capacity utilisation |

||||

|

Consumer price inflation |

1.8 |

3.2 |

4.3 |

3.7 |

|

Unemployment (% of labour force) |

3.2 |

2.3 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

|

Output gap (% of potential GDP) |

-3.6 |

-1.6 |

-1.0 |

-0.6 |

|

Public finances (% of GDP) |

||||

|

Government fiscal balance |

-3.4 |

-4.3 |

-3.6 |

-2.9 |

|

Expenditures |

21.9 |

21.2 |

20.5 |

20.0 |

|

Revenues |

18.5 |

17.0 |

17.0 |

17.2 |

|

Government gross debt |

38.7 |

38.8 |

38.7 |

38.2 |

|

External sector and memorandum items |

||||

|

Trade balance (% of GDP) |

4.3 |

6.3 |

2.8 |

2.9 |

|

Current account balance (% of GDP) |

-2.1 |

-0.9 |

0.4 |

1.2 |

|

Nominal GDP (USD billion, at the market exchange rate) |

366.1 |

410.6 |

451.7 |

494.4 |

Note: Data for 2023 and 2024, as well as fiscal data for 2022, are OECD projections. The breakdown of private and government investment are based on OECD calculations. Net changes in inventory include statistical discrepancy. Updated GDP is used to calculate fiscal indicators.

Source: General Statistics Office (GSO); Ministry of Finance; State Bank of Viet Nam; CEIC; OECD Economic Outlook database and OECD projections.

Despite the growing concerns over global trade and supply chain disruptions, the Vietnamese economy is projected to manage to keep its growth momentum from 2022 onward. Real GDP is forecast to grow by 6.5% in 2023 and maintain the speed at 6.6% in 2024 (Table 1.2). Domestic demand will keep gathering pace as sanitary restrictions are being removed. Business investment will be solid as foreign investment is resuming. Government investment, included in the latest stimulus package, is also anticipated to prop up growth. Nevertheless, high energy and food prices are weighing on economic prospects. In particular, although the poverty rate is anticipated to further decline (World Bank, 2022[8]), purchasing power of households is being affected and private consumption growth will be moderate after the strong rebound from the bottom of the third quarter in 2021. The prolonged war in Ukraine is weighing on global trade, and supply chains are being disrupted. Nevertheless, the direct impact of the war on Viet Nam is limited and external demand is expected to be stable. China’s changing COVID policy is adding further uncertainty to regional trade, but this would also help push up Viet Nam’s relative attractiveness as an investment destination. In this context, implementing structural reforms, particularly reforms to improve the business climate, is crucial to realise a robust recovery and to boost growth in the medium term (Table 1.3). However, this requires significant and ongoing efforts. For example, it took almost five years for South Africa to halve the gap with the OECD average in terms of state control, which is captured by the sub indicator of “scope of state-owned enterprises” in the OECD Product Market Regulation indicator (the 2008 and 2013 vintage). Hungary succeeded in closing the gap with the OECD average in the same index but it took almost ten years from the late 1990s.

Table 1.3. Illustrative GDP impact of recommended reforms

Difference in GDP per capita level, %

|

Measure |

Description |

1 year after the reform |

10 years after the reform |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Lower regulatory barriers measured by the overall Product Market Regulation indicator |

Fully closing the gap to the OECD average |

0.2 |

1.1 |

|

Reduce scope of state control measured by the corresponding Product Market Regulation indicator (“scope of state-owned enterprises”) |

Closing 1/4 of the gap to the OECD average |

3.2 |

9.2 |

|

Lower barriers to trade and investment measured by the corresponding Product Market Regulation indicator (“barriers to trade and investment”) |

Fully closing the gap to the OECD average |

1.0 |

7.3 |

Note: Simulations are based on the framework of (Égert and Gal, 2016[9]). The framework assumes that structural reforms affect GDP per capita through changes in multi-factor productivity, capital intensity and the employment rate. The OECD Product Market Regulation (PMR) indicators are used to measure the progress of structural reforms. Coefficients of reform impacts are calculated for each policy measure by using cross-country data covering OECD countries and some emerging-market economies. Results show the effect on the level of GDP per capita 1 year and 10 years after the reform is completed compared to a baseline scenario with no policy changes.

Source: OECD calculations.

Risks are largely tilted to the downside. The global pandemic is not yet over, and the emergence of more contagious virus variants would require re-imposition of strict sanitary restrictions, intensifying supply chain disruptions. If the global economy went into a recession due to rising inflation and the related tightening of monetary policy, as well as the prolonged war in Ukraine, this could severely affect highly trade-dependent Viet Nam. If China’s growth decelerates, external demand could become more volatile and experience periods of persistent weakness. Inflation that remains unexpectedly higher than currently anticipated could erode households’ purchasing power and stall the recovery, increasing the incidence of poverty. A more rapid monetary policy tightening in advanced economies would put downward pressure on exchange rates and would require an abrupt tightening of monetary policy in Viet Nam, harming the nascent recovery. This would also require fiscal tightening which could further weaken domestic demand. On the upside, stronger than expected growth of the US economy, owing to healthy household and corporate balance sheets, could further boost exports. Amid an increasingly uncertain external environment, foreign investors could also increasingly appreciate the stable investment climate of Viet Nam. These risk factors, both to the downside and upside, add uncertainties to the short-term economic projections. The potential impacts of some low-probability risks that are not assumed in the projection profile are summarised in Table 1.4.

Table 1.4. Events that could lead to major changes to the outlook

|

External shocks |

Potential impacts |

|---|---|

|

Energy crisis |

A sudden stoppage of energy imports and extremely high energy prices could harm broader economic activities with hyperinflation. |

|

Pandemics |

The emergence of new deadly zoonotic diseases would dent the overall economy and cause large-scale social distress. |

|

Natural disasters |

Extreme weather, such as floods and droughts, could overwhelm the existing coping capacity and bring about wide-ranging dislocation of economic activity, including cuts in electricity supply and shortage of food. |

|

Geopolitical crises |

The escalation of tensions or other serious social unrest in the region would entail long-lasting supply chain disruptions and deteriorate sentiment of foreign investors. |

Substantial policy space could be used if downside risks eventuate

In the short run, the policy priority is to prevent domestic demand from contracting, particularly household consumption which accounts for nearly 70% of GDP. As the recovery is under way and inflationary pressures are rising, further expansionary fiscal support is not required. In addition to cutting the value-added tax rate (from 10% to 8% between February and December 2022), the government cut the environmental protection tax, which is a tax on fossil fuels, by 50% from April 2022 and an additional 25% from July (effective until December 2022). The tax rate of the preferential import duty was also reduced for unleaded motor gasoline from August 2022 (from 20% to 10%). Nevertheless, as a gradual fiscal consolidation is required (see below), including through increasing the collection of government revenue, such measures are not desirable in the medium-term. If high inflation remains more persistent than currently expected, a targeted approach to fiscal support that does not encourage demand for fossil fuels would be preferable. An example would be cash transfers that are limited to vulnerable households. Viet Nam has an annually updated poverty list, “Poor List”. Previous studies suggest that, although better than in other emerging market economies, the list has some leakages (Kidd et al., 2016[10]), and this should be improved by cross-referencing different administrative information using digital technologies. A large number of people do not pay taxes (mostly due to low incomes) and this limits the use of the tax database for tightly targeting fiscal transfers, although it has already been digitised. Since the onset of the pandemic, the government has been accelerating the digitalisation of a citizenship database (i.e. personal identification). This could be linked to other databases, such as those for social security and health insurance, in order to improve targeting. Supporting the capacity building of local governments is also crucial as they are the entities of actual implementation. At present, there are considerable differences between regions in the capacity of local governments. Moreover, public investment projects should be executed as planned in order to avoid any unanticipated demand fluctuations. In particular, transportation infrastructure that supports logistics and inter-regional connectivity should be accelerated given the potential for further supply disruptions. The 2019 Law on Public Investment simplified procedures and strengthened the decentralisation of investment management, which is conducive to facilitating budget disbursement (Madani, Nguyen and Nguyen, 2021[11]). Further simplification of procedures and regulation should be considered. Nevertheless, acceleration of public investment should not come at the expense of the quality of investment projects. Budget allocation could better take into account local governments’ implementation capacity, which considerably varies between jurisdictions (Madani, Nguyen and Nguyen, 2021[11]). In this regard, a framework for ex post evaluation introduced in the previous 2014 Law on Public Investment should be applied more actively to domestically funded projects of local governments in the medium term, as it is rarely conducted (World Bank, 2018[12]).

Public healthcare capacity should also be enhanced to prepare for possible large-scale COVID-19 outbreaks. Sufficient public healthcare capacity is also crucial to avoid severe restrictions, which have implications for sentiment of households and businesses. During the pandemic, healthcare facilities were under significant strain in some areas, especially in the third quarter of 2021, and this made it inevitable for the government to adopt strict sanitary measures. As soon as the restrictions were eased in October 2021, a number of people living in urban areas (“urban migrants”) returned to their hometowns because of lockdown fatigue. Indeed, one previous study suggests that some urban migrants put more emphasis on quality of life than monetary earnings (Luong, 2018[13]). Ineffective coordination between the central and local governments in some cases caused disruptions in domestic food supply chains, and complicated procedures slowed the disbursement of cash handouts. As of mid-December 2021, approximately 2.2 million urban migrants left their living places, resulting in a shortage of labour during the initial stage of economic re-opening in the urban areas, where most industrial capacity exists.

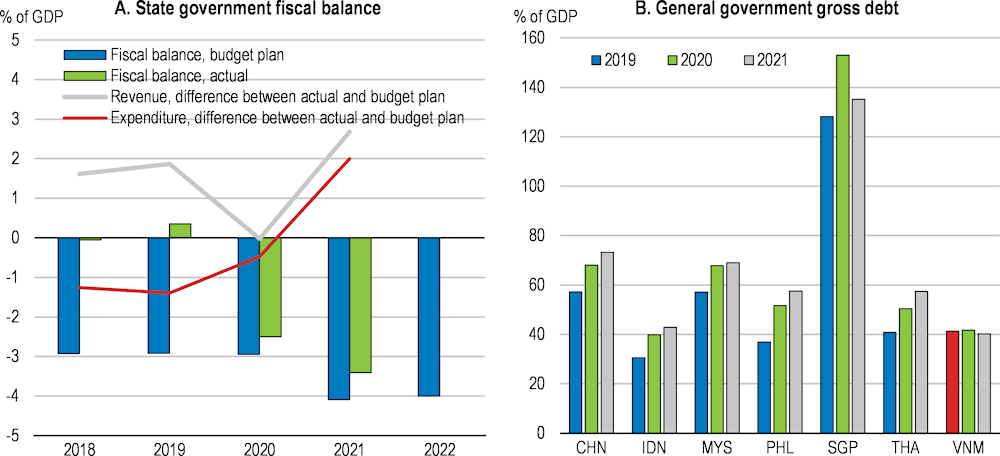

Improving the management of budget disbursement has become increasingly important to strengthen the effectiveness of fiscal policy, notably its counter-cyclicality. In 2020, while additional fiscal spending in the stimulus packages was small, the government accelerated the disbursement of the planned budget. As a consequence, while the actual current expenditure increased less than the initial plan (the actual nominal growth was 2.5% and the planned was 12.1%; planned growth is the changes from the final budget of the previous year), government investment (“development investment”) rose much higher than planned (36.6%, while planned was 11.6%). This appropriately supported the economy. In contrast, according to the latest budget estimates, the actual spending considerably slowed in 2021, despite the adoption of additional stimulus packages. While current expenditure increased by 4.8%, government investment plummeted by 10.5%. This was partly due to a lack of labour, increasing costs of construction materials and physical constraints associated with the severe lockdowns, and the rebound from the high spending levels in the previous year. In general, budget disbursements should not be interpreted as real progress in public work and government consumption as there are always execution lags. Nevertheless, the significantly volatile fiscal spending implies inefficient management of budget disbursement. Indeed, in Viet Nam, differences between planned budget and actual spending are large (see below). The gap has been caused by various factors. Coordination not only between ministries but also between different levels of governments should be improved. In particular, budget carryovers from the previous year are still large despite government efforts to reduce them, including the introduction of the Law on State Budget 2015, which aims to narrow the scope of carryover expenditure. The quality of budget planning, including the accuracy of revenue and spending estimation, and implementation could be improved (IMF, 2022[14]).

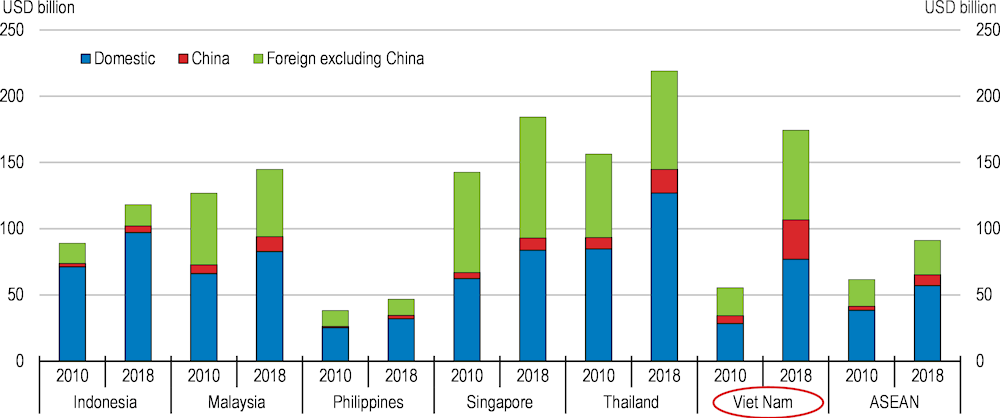

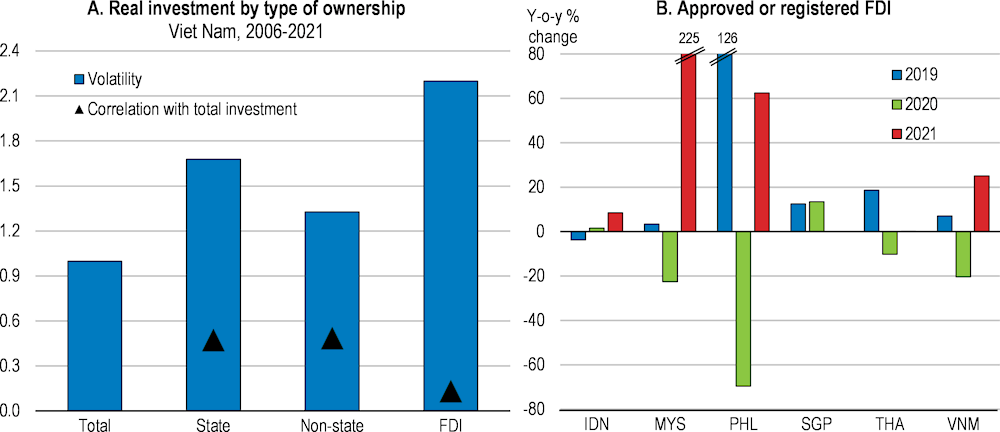

Stimulating foreign investment is also a priority. Although its fluctuations have a small impact on overall investment trends due to its small share in total investment (approximately 20%), foreign investment is more sensitive to general economic conditions (Figure 1.9, Panel A). Some Southeast Asian countries saw a strong upsurge of foreign investment (registered capital) in 2021, more than offsetting the contraction in 2020 (Figure 1.9, Panel B). On the other hand, Viet Nam’s rebound in 2021 was rather moderate, partly due to the severe lockdown in the third quarter of 2021. Southeast Asian countries have implemented policies to improve their business climate even during the pandemic. The Philippines, where a large rebound was recorded in 2021, pledged to reduce corporate tax rates from 2021, and recently decided to open up services markets further. Viet Nam has already reduced multiple de jure barriers to foreign entry. Nevertheless, more could be done, particularly for implementation. In Viet Nam, FDI management, such as licensing, is under the remit of provincial governments. However, the administrative capacity varies between provinces, potentially creating additional costs for businesses. Coordination between central and provincial governments could also be enhanced. In addition to capacity building, more involvement of local governments in national policy-making process would be helpful (Tran, 2019[15]). Moreover, foreign investment often necessitates the cross-border flow of skilled foreign workers. While pandemic-induced border closures have been lifted, Viet Nam has scope for reducing restrictions on cross-border mobility of skilled workers as suggested by the OECD Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (see Chapter 2). Promoting foreign investment in sectors which can support decarbonisation efforts, such as the renewable energy and transport sector, can have positive effects on the green transition through various channels, including via technology spillovers (OECD, 2022[16]). This requires not only strengthening policies that provide favourable conditions for climate-friendly investment, such as investment incentives or promotion, but also setting up domestic environmental standards (e.g. fuel efficiency regulations) that are well aligned with national climate objectives.

Figure 1.9. The pandemic affected FDI inflows differently between Southeast Asian countries

Note: For panel A, the annual growth rates of investment are used for calculation. Volatility is defined as the coefficient of variance. For panel B, 2021 data is not yet available for Singapore.

Source: CEIC.

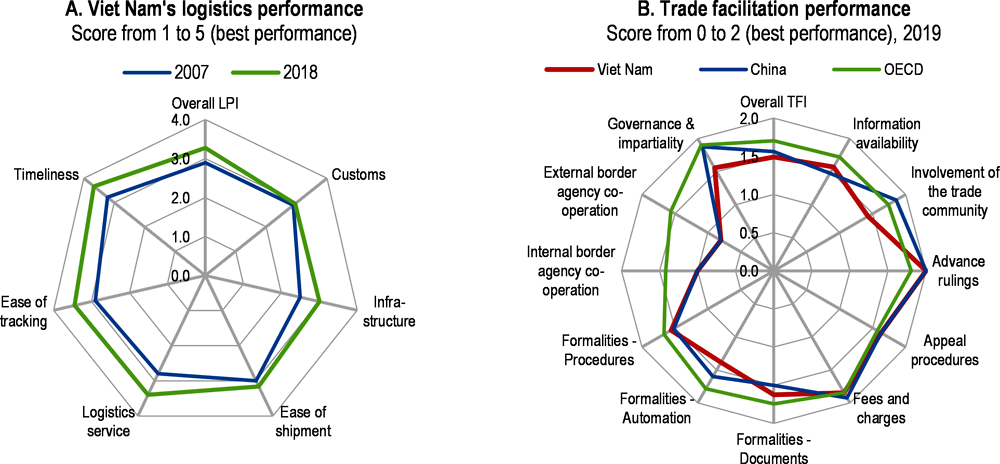

Recent supply chain disruptions underscored the importance of trade facilitation. Trade facilitation can also help remove obstacles to economic re-opening towards full capacity. Viet Nam has made substantial progress since 2015 when the country ratified the Trade Facilitation Agreement of the World Trade Organisation (Figure 1.10, Panel A). Integrated information systems, the National Single Window and the ASEAN Single Window, were successfully introduced by the strong National Trade Facilitation Committee (UNCTAD, 2020[17]). Nevertheless, there is scope for improvement. Specialised inspection, which is a border clearance procedure conducted by line ministries for 30-35% of traded goods, is time-consuming (USAID, 2021[18]). The government is planning to issue a Decree to harmonise procedures for imported goods. To realise effective implementation, strengthening coordination and monitoring functions of the National Trade Facilitation Committee is crucial, both at the national and regional levels. Currently, the Committee is focused on the operation of Single Windows (USAID, 2021[18]). Expanding stakeholder engagement especially with SMEs, which would benefit most from trade facilitation, can make the Committee’s policy coordination and monitoring more effective, as it will give more up-to-date demand-side information to the Committee.

Moreover, compared with other trade facilitation measures, progress in cross-border coordination is slow (Figure 1.10, Panel B) (Ha and Lan, 2021[19]). Even during the pandemic, the implementation of trade facilitation advanced in a number of countries, including in the Southeast Asian region (Asian Development Bank, 2021[20]), but this did not necessarily entail greater cross-border cooperation. Regional cooperation could bring about more benefits than unilateral efforts, in particular for highly trade-dependent countries, such as Viet Nam. While infrastructure connecting countries in the region has been developed, trade facilitation measures specific to land transport between countries are still weak. In response, the Great Mekong Subregion Cross-Border Transport Facilitation Agreement (GMS-CBTA), a legal framework to facilitate cross-border land transport in the region, has been ratified by Cambodia, China, the Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand, and Viet Nam (Asian Development Bank, 2021[21]). The GMS-CBTA is expected to remove barriers through information exchange and policy harmonisation, and Viet Nam should be more active in implementing this programme.

Figure 1.10. Viet Nam's trade facilitation performance could be further improved

Note: The overall LPI is a summary indicator of logistics sector performance, combining data on six core performance components. The 2019 trade facilitation performance series introduces new measures across all dimensions and particularly in the area of external and internal border agency co-operation, procedures, automation, documents, information availability and involvement of the trade community.

Source: World Bank, Logistics Performance Index, https://lpi.worldbank.org/; OECD, Trade Facilitation Indicators, http://www.oecd.org/trade/indicators.htm.

Trade integration should be deepened further. Similar to other ASEAN countries, Viet Nam has actively been participating in a number of preferential trade agreements. At present, 15 agreements are in force (seven made by ASEAN) and two others are being negotiated. Viet Nam benefits greatly from pursuing free and open trade with wider regions. Vietnamese businesses now have access to markets more extensively and intensively than before. Consumers and businesses are also better off from Viet Nam's open markets with a variety of imported goods and services now available at lower prices. Indeed, previous studies suggest that the recently enforced Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, large preferential trade agreements in Asia Pacific region, will push up Viet Nam's aggregated real income by 3.4% and 1.0% respectively compared with the baseline in the next ten years – one of the largest impacts among ASEAN countries (Park, Petri and Plummer, 2021[22]).

An open, diversified and transparent trade system can also provide a basis for economic resilience. At the beginning of the pandemic, a strong surge in demand caused global shortages of personal protective equipment. However, overall global value chains (GVCs) acted to cushion the impact, as in previous catastrophic events, such as the Great East Japan Earthquake and severe floods in Thailand in 2011 (OECD, 2020[23]). For example, global production and trade of essential goods, such as face masks increased rapidly to meet demand. Indeed, previous studies suggest that localisation and re-shoring would be likely to lower the levels of real GDP and stability in the face of shocks (OECD, 2021[24]). The business sector is in an essential position to enhance its own supply chains. Stable, transparent and predictable trade and investment policy can facilitate diversification of GVCs and reduce uncertainty for businesses (see Chapter 2). Governments can also invest in critical infrastructure to secure essential flows of products, people and information.

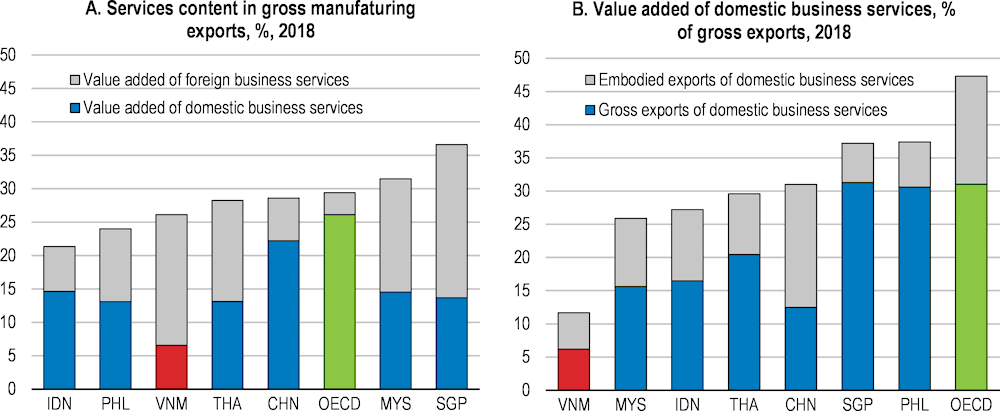

The services sector can play a more important role in Viet Nam's international trade, not least through indirectly exporting their products through manufacturing goods. Services inputs, such as marketing and design, are important determinants of manufacturing competitiveness. Moreover, information and communication technologies have blurred the boundary of manufacturing and services. Different from traditional manufacturing goods (e.g. fabrics and steel), modern manufacturing goods contain considerable services elements (e.g. operating systems in computers). Indeed, the value-added of business services embodied in manufacturing goods accounts for nearly 30% of total value-added of manufacturing exports from OECD countries (Figure 1.11, Panel A). However, manufacturing exports from Viet Nam embody smaller amounts of services and the share of domestically produced services is much smaller. Looking forward, there is scope for Viet Nam to increase the value-added of its manufacturing exports by increasing product sophistication with domestically supplied services inputs, such as quality design and software. The digital transformation is one of the key determinants to deepen the sophistication of domestic production. In this regard, foreign direct investment in digital sectors can help promote the digital transformation of the domestic economy. To attract digital FDI, Viet Nam needs to further improve the business climate, including for the digital economy, such as privacy protection, and digital skills of workers (Matthew, 2020[25]) (see Chapter 2).

There is also the potential to increase direct exports of Vietnamese services. A number of countries have expanded their direct exports of business services, such as financial and ICT servicers, whereas Viet Nam somewhat lags behind (Figure 1.11, Panel B). Expanding direct service exports will diversify and strengthen Viet Nam’s integration to international trade. To nurture the services sector, improving the business climate is particularly crucial (see Chapter 2). In this regard, preferential trade agreements that encapsulate services can be a strong driving force for domestic services market reforms (OECD, 2020[26]). In addition, as services are more labour intensive than manufacturing, developing skills should be a priority. Some business services, such as financial and consultant services, are digitally deliverable and trade in such items has been expanding (Asian Development Bank, 2022[27]). Therefore, improving digital skills from the currently low levels will be conducive to developing business services sectors (see Chapter 2).

Figure 1.11. Business services account for a small share in Viet Nam's exports

Monetary policy needs to keep inflation expectations well anchored

Viet Nam has a unique monetary policy framework together with a managed float system of currency exchange. Its central bank, the State Bank of Viet Nam, is a ministerial organisation of the central government, and its independence is not explicitly defined. The governor is a member of Cabinet appointed by the National Assembly based on the Prime Minister’s proposal. The policy objective of monetary policy is the stability of the currency denoted by the inflation rate, and the National Assembly is responsible for monetary policy, including determining policy targets based on the government’s projections. In addition to inflation, credit growth targets are also set and annually reviewed. As the policy implementation body, the central bank sets policy rates, the refinancing rate and discount rate. It also imposes credit growth ceilings to banks individually (see below). The central bank manages the exchange rate with regard to a basket of some major foreign currencies and guides its daily fluctuation within the pre-announced bands for the US dollar (USD) (currently ±5%).

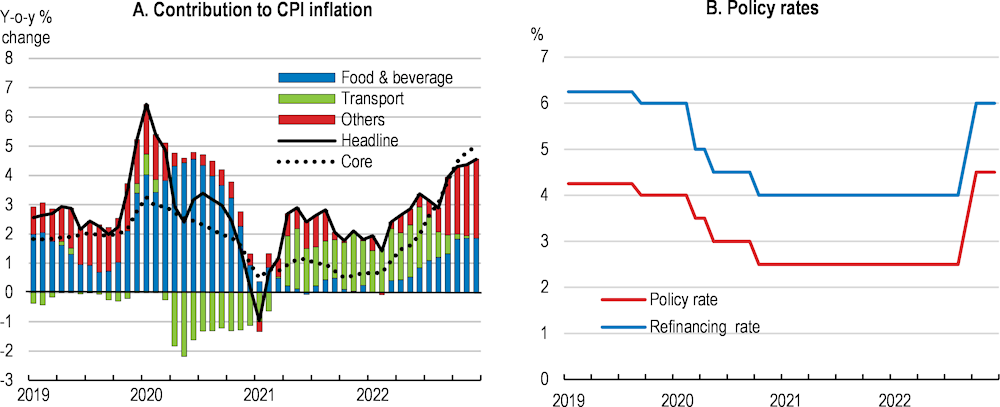

From the onset of the pandemic to mid-2022, monetary policy was largely supportive of growth. The real interest rate on 10 year government bonds was 0.4% in the first seven months of 2022 compared with 1.5% in 2019. This accommodative stance of monetary policy was appropriate in the low inflation environment, with headline inflation remaining stable over the past two years. Low energy prices during 2020 offset a food price hike stemming from outbreaks of African swine fever (Figure 1.12, Panel A). While energy prices rebounded in 2021, core inflation was subdued amid weak demand constrained by sanitary restrictions, particularly through the middle of the year. Responding to the economic slowdown caused by the lockdown measures within and outside of the country in early 2020, the central bank had reduced the refinancing rate from 6% to 4% between March and October 2020 (the discount rate from 4% to 2.5%), and maintained its accommodative policy stance (Figure 1.12, Panel B). In the same period, the central bank also reduced interest payments offered to buy security instruments through open market operations (OMO) from 4% per annum to 2.5%. The stable exchange rate has also helped tame inflation. While the currencies of other Southeast Asian countries experienced a large swing between depreciation and appreciation in the foreign exchange market, the Viet Nam dong (VND) has been less volatile.

Figure 1.12. Monetary policy has been supportive of growth, while inflation has been stable

Both headline and core inflation have picked up since early 2022. In addition to economic reopening, the war in Ukraine has been pushing further up energy and commodity prices, which already started rising in 2021. Like other net importers of energy or commodities, Viet Nam’s headline inflation is susceptible to the swings of such commodities on international markets (Figure 1.13). Although less than in countries with fully floating currency regimes (i.e. where currencies weaken), rapid increases of import prices would raise input prices, affecting broader inflation. Moreover, although economic slack still remains, demand has picked up rapidly following the removal of most sanitary restrictions by early-2022. Some upstream prices have already risen. The producer price index for manufacturing increased by nearly 4% (year-on-year basis) from the fourth quarter of 2021, the highest increase since 2013. As discussed earlier, the government temporarily reduced the environmental protection tax on fossil fuels from April 2022, in addition to the already-determined cut in the value-added tax rate. In addition, the government is considering reducing the value-added tax and special consumption tax on fossil fuels. However, a more targeted approach, notably cash transfers to vulnerable households would help ensure that further support does not excessively stimulate demand. In addition, such an intervention would not encourage demand for fossil fuels to the same extent as the reductions in taxes on fossil fuels.

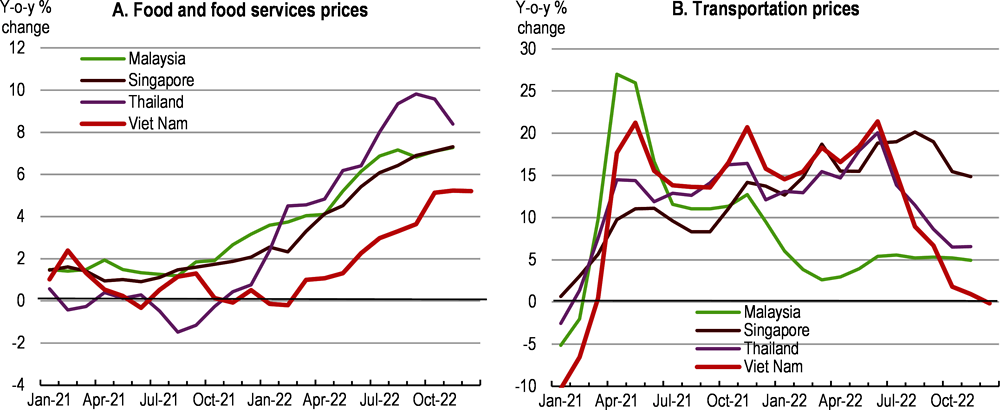

Food prices will be an important determinant of future overall inflation. Similar to other Southeast Asian countries, food accounts for a large share of the household consumption basket (CPI weight: Viet Nam 33.6%, Malaysia 28.4% and Thailand 40%). The current increase of inflation has mostly been led by the increase of “transportation” prices, reflecting higher energy prices, although its pace has become moderate since August 2022. Prices of other items, including “housing and construction materials” that contains energy inputs and “foods and foodstuffs” have also begun edging up, but the increase of food prices has been moderate compared with other Southeast Asian countries (Figure 1.14). In particular, while the prices of “eating outside” have been increasing (7% y-o-y in September), the increase of “foodstuff” prices (i.e. food such as perishables, that has a CPI weight 21.3%) has been moderate (3% y-o-y in September). Viet Nam’s high self-sufficiency of staples, such as rice, could contribute to more moderate price increases of foodstuff compared with some other countries. However, Thailand, whose food-sufficiency is similarly high, has already seen the price of “raw food” rising significantly (11% y-o-y in September). Prices of perishable foods are affected by local weather conditions but also costs of various inputs, such as fertilisers as well as energy which are largely determined in global markets. The war in Ukraine has been pushing up international prices of fertilisers. Prices in urban areas, which often lead price developments in the country as a whole, are picking up (foodstuff in Hanoi increased 5% y-o-y in July followed by 3% both in August and in September).

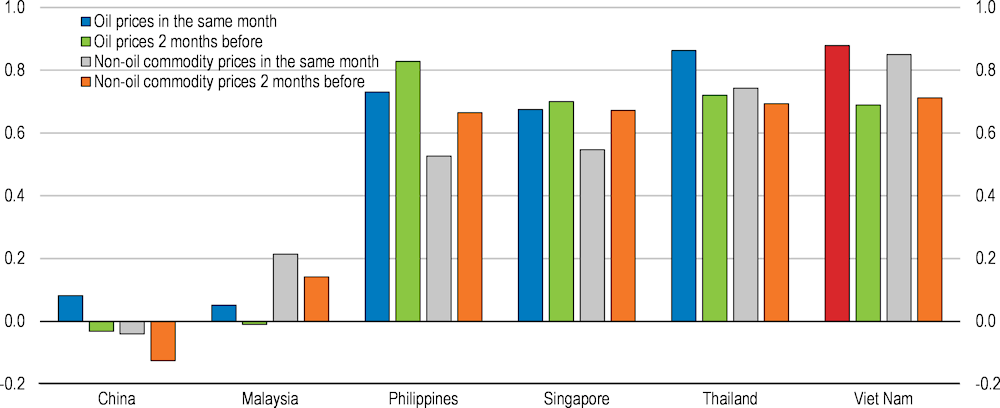

Figure 1.13. The increase in global energy and commodity prices has pushed up inflation

Correlation between the consumer price index and the oil and non-oil commodity prices, January 2015 - December 2019

Note: Correlation coefficients are calculated for the year-on-year changes of consumer price index and the global oil (Brent) or non-oil commodity prices. The coefficients vary between 1 and -1, with a value closer to 1 (respectively -1) means positive (respectively negative) correlation. 0 means no correlation.

Source: CEIC; OECD, Economic Outlook database.

Figure 1.14. Both food and energy prices are increasing in Southeast Asian countries

Going forward, monetary policy needs to be vigilant against upward risks to inflation, while seeking for gradual normalisation of its policy stance over the projection period. Under the assumption of continued economic recovery, the policy rates would surpass the pre-pandemic levels towards end-2023, while inflation is forecast to be 4.3% in 2023, before slightly slowing to 3.7% in 2024. The central bank already started to change its policy stance amid increasing inflationary pressures and currency depreciation. The policy rates were raised both in September and in October 2022 (the refinancing rate was raised from 4% to 6% and the discount rate from 2.5% to 4.5%). In addition, in October 2022, the central bank widened the range of daily exchange rate fluctuation from ±3% to ±5%. The uncertain external environment poses a difficult dilemma for the path of normalisation and necessitates a clearer division of labour between monetary and fiscal policies. Monetary policy should focus on price stability, while fiscal policy should support vulnerable groups in light of higher energy costs. Delaying unwinding of the highly accommodative stance of monetary policy would increase the risk of higher inflation expectations becoming embedded. As formal employees are not the majority of workers, official wage indicators are not necessarily a good indicator of impending inflation pressures in Viet Nam. Nevertheless, wages have increased rapidly partly due to the slow recovery of labour supply (the minimum wage was raised in July 2022 by 6% on average). Moreover, differences in interest rates between major trading partners may put downward pressure on the currency, further pushing up domestic inflation. However, the continued and intensified war in Ukraine will weaken external demand and high energy and food prices will erode purchasing power of households and profit margins of businesses. Although economists that participate in the Consensus Economics Survey (the sole measure of inflation expectations) expect inflation to moderate to 2.8% on average in 2024 (as of October 2022), it ranges from 2.5% to 5.5%. This suggests that the inflation outlook is highly uncertain, but monetary policy may need to tighten earlier than currently anticipated if there are signs that the upside risks materialise.

In the medium- to long-term, Viet Nam could consider reviewing the monetary policy framework and exchange rate regime to further enhance economic resilience along with its economic development. Similar to Viet Nam, a number of emerging market economies adopt integrated monetary policy frameworks that use foreign exchange intervention and/or capital flow management tools as key monetary policy instruments in addition to interest rates. Emerging market economies tend to be vulnerable to external shocks, such as swings in cross-border capital flows and this poses policy dilemmas. For example, lower policy rates to deter large capital inflows may overstimulate domestic demand and raise asset prices, increasing financial market instability. Integrated policy frameworks could mitigate these policy trade-offs under certain conditions, such as vulnerability to external shocks (Adrian et al., 2020[28]). Indeed, previous studies suggest that, under Viet Nam’s current policy framework that combines foreign exchange intervention and credit growth guidance, fluctuations of economic indicators, such as inflation, to external shocks is likely to be smaller compared with a policy framework solely relying on interest rates (Epstein et al., 2022[29]). Nevertheless, long-term potential costs of this policy framework would also need to be considered. For example, exchange rate intervention and capital controls could delay further developments in financial markets which have become important for Viet Nam (see below). Past international experience suggests that foreign exchange intervention could also affect investors’ assessment of currency risks and heighten potential vulnerabilities in the financial market. If movements in the foreign exchange market are structural, intervention would not be effective in stabilising the exchange rates.

Against this background, Viet Nam could consider modernising its monetary policy framework, narrowing policy targets, and moving to a more flexible exchange rate regime once the financial markets are liberalised and developed further. A number of eastern European countries have successfully made such a transformation in their monetary and foreign exchange frameworks. As Viet Nam’s linkages to global trade further expand, it will be particularly crucial to adopt a more flexible foreign exchange regime. A flexible exchange rate regime allows the currency to depreciate when the terms of trade worsen, which makes exports more competitive and thus can cushion the external shock, while a fixed exchange rate system cannot (Broda and Tille, 2003[30]). Moreover, under rigid exchange regimes, domestic financial conditions are more likely to be affected by global financial shocks than under flexible regimes (Obstfeld, Ostry and Qureshi, 2017[31]), and tighter fiscal discipline is required to avoid current account imbalances (Khatat, Buessing-Loercks and Fleuriet, 2020[32]). Transition to a more flexible exchange rate regime will allow the State Bank of Viet Nam to focus on narrower policy targets, notably the inflation target, which can contribute to more stable macroeconomic conditions. This policy transition should be made in tandem with enhancing central bank independence (IMF, 2019[33]). Currently, operational independence is loosely defined, as both the Prime Minister and the Governor can determine administrative tools and measures of monetary policy. To this end, establishing a collective decision-making body (i.e. monetary policy committee) which is appointed by the National Assembly and given operational autonomy independently from the Cabinet will be necessary (National Assembly Economic Committee, 2012[34]). Inflation is lower and more stable in countries where central banks conduct monetary policy independently. According to the Prime Minister’s Decision No.986/QD-TTg on the “Development Strategy of Vietnam Banking Sector to 2025, with Orientations to 2030” issued in 2018, the government considers gradually increasing the independence of the State Bank of Viet Nam in its conduct of monetary policy. Moreover, enhancing the banking sector is essential for a better functioning of transmission mechanism for monetary policy (see below). The interbank market also needs to be developed further. Currently, due to the thin trade volume, interbank rates are volatile.

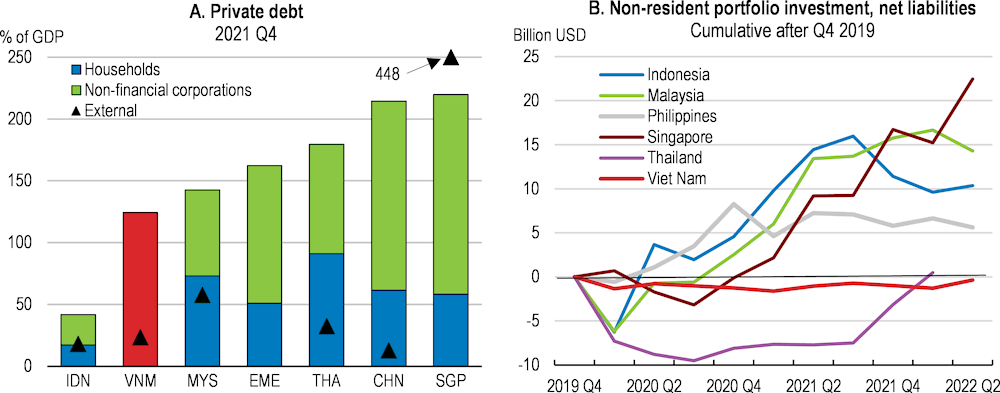

Financial markets need to be strengthened for smooth resource reallocation

Banks are resilient, but need to closely monitor the rise of non-performing loans

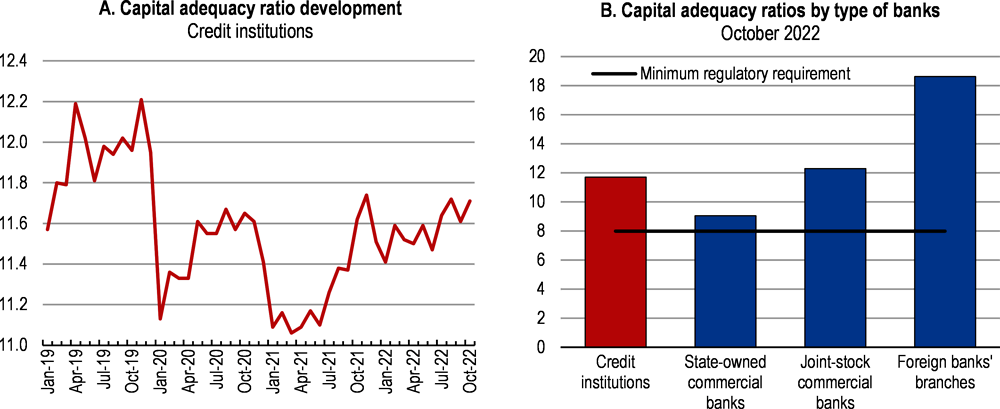

Viet Nam’s banking sector was well-prepared when the pandemic hit, thanks to past efforts to improve the sector’s resilience (World Bank, 2021[35]). In the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, while the economy kept growing overall, banks suffered from a rise in bad debts following a boom and burst in the housing market. In 2012, the government adopted a roadmap to reform the banking sector, reducing the number of institutions. Although not a signatory, the government announced in 2016 that major banks would need to meet regulations similar to Basel II by January 2020 (extended to 2023 due to the pandemic). At the same time, Viet Nam stepped up its non-performing loan (NPL) resolution framework. The Viet Nam Asset Management Corporation (VAMC) was set up in July 2013, and a new bankruptcy law adopted in 2014. Resolution 42, which gives more autonomy to debt buyers, was adopted in 2017 as a pilot policy framework.

During the pandemic, the central bank introduced temporary measures to support affected households and businesses. A debt restructuring programme was adopted in 2020 (Circular 01 issued in 2020) and then extended twice (Circular 03 and 14 issued in 2021). While debt restructuring is implemented, banks do not need to change (i.e. downgrade) the classification of restructured loans. Sufficient capital buffers allowed banks to effectively implement debt restructuring without experiencing financial stress. Capital adequacy ratios have slightly declined but not deteriorated (as of March 2022, the capital adequacy rate requirement of 8%, which is compatible to Basel II, was applied to 85 institutions out of 96 commercial banks) (Figure 1.15). Nevertheless, to avoid worsening the profitability and capital buffers of the banking sector, banks have been requested to pay dividends to shareholders in shares rather than in cash. In addition, preferential loans were provided to affected sectors by state-owned banks.

Figure 1.15. Most commercial banks seem to have sufficient capital buffers

As these emergency treatments, particularly debt restructuring, have been removed along with the economic recovery, enhanced supervision has become more important. The construction, trade and services sectors, which have been affected severely by the pandemic, accounted for large share of bank loans outstanding (9%, 24% and 38% respectively at the end of 2021, while manufacturing was 19%). Nevertheless, the on-balance sheet non-performing loan (NPL) ratio has been low and stable, although it edged up slightly in 2020 and early 2021(Figure 1.16, Panel A). The quick economic recovery has helped contain the NPL ratio, but the temporary measures could also conceal the worsening of asset quality. For example, estimates by the IMF suggest that the NPL ratio, which includes off-balance sheet NPLs enshrined in the Viet Nam Asset Management Corporation, would rise by around 2.5 percentage points from 2019 to 2020 if regulatory forbearance were not taken into account (IMF, 2021[36]). The temporary measures would unnecessarily help nonviable businesses survive for a longer time, deteriorating bank profitability. This could also hinder a better resource allocation in the whole economy through resources being tapped in low performing firms. As the temporary debt restructuring measure expired in June 2022, loan quality should be adequately recognised and banks need to make necessary provisions or write-offs in accordance with the debt classification applied to normal economic conditions, while avoiding a deterioration of their balance sheets. To this end, the State Bank of Viet Nam needs to enhance supervision of individual banks.

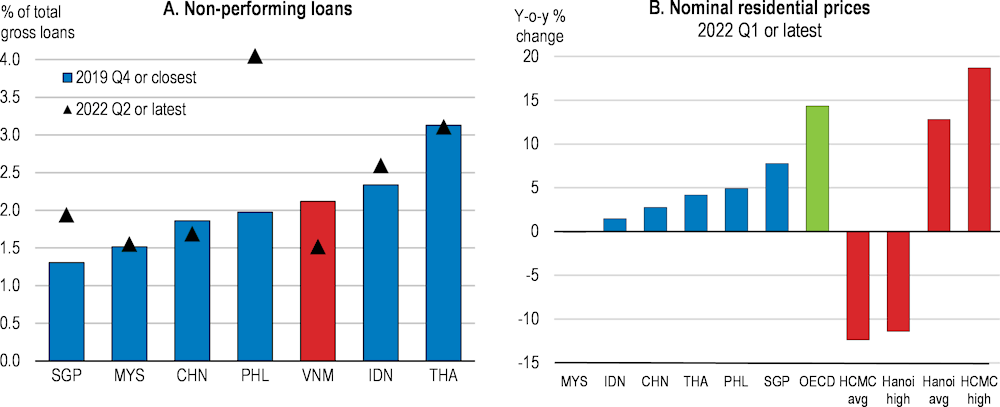

Figure 1.16. The economic recovery has helped to manage non-performing loans

Note: Panel B: data for Malaysia is -0.10. For Viet Nam, data shown refer to the high-end market and the average prices in Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi.

Source: Panel A: IMF, Financial Soundness Indicators database; Monetary Authority of Singapore; and State Bank of Viet Nam. Panel B: BIS, Property Prices; OECD, House Prices Indicators database; CBRE and Cushman-Wakefield for Viet Nam.

In addition, market-based solutions for NPLs could also be further strengthened. Compared with on-balance solutions, such as stringent provision or write-offs, removing NPLs from banks’ balance sheets through direct sales could avoid deterioration of bank capital and profitability (OECD, 2021[37]). Viet Nam has already moved in this direction. In April 2022, the effective period of Resolution 42 was extended from August 2022 to the end of 2023. Nevertheless, there is scope for improvement (Nguyen, 2021[38]). As asset seizure relies on bona fide cooperation of debtors, creditor rights could be further enhanced by stipulating clearly in regulation that ordinary investors can seize collateral without court arbitration (Asian Development Bank, 2021[39]). Entry of foreign investors could be more encouraged by easing restrictions related to property ownership. In addition, the Viet Nam Asset Management Corporation (VAMC) could focus more on direct purchase of NPLs, so that it would benefit from scale economies (Hoang, Nguyen and Le, 2020[40]). The VAMC can buy NPLs from credit institutions either directly at market value or in exchange for special bonds. In the latter case, the VAMC’s role is passive, just supporting NPL resolution by credit institutions, and unresolved debts will be returned to the credit institutions after five years, which means that NPLs are not permanently transferred but tentatively ring-fenced in the VAMC. To strengthen the VAMC’s leverage, its charter capital has increased from VND 500 billion to 5 trillion between 2013 and 2019, but should be further increased, as it is smaller than total NPLs in the whole banking system (VND 424 trillion as of August 2021, as identified under Resolution 42 (Nguyen, 2021[38])). The authorities should also consider reducing charter capital after a pre-determined period in order to facilitate overall NPL resolution processes.

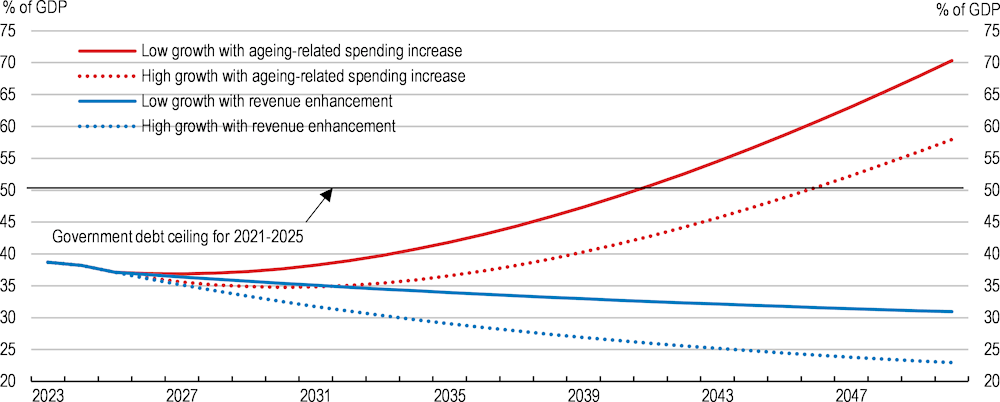

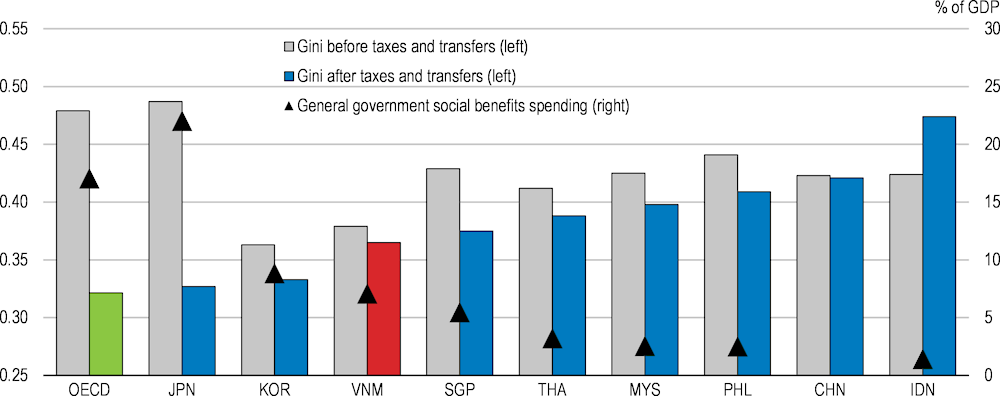

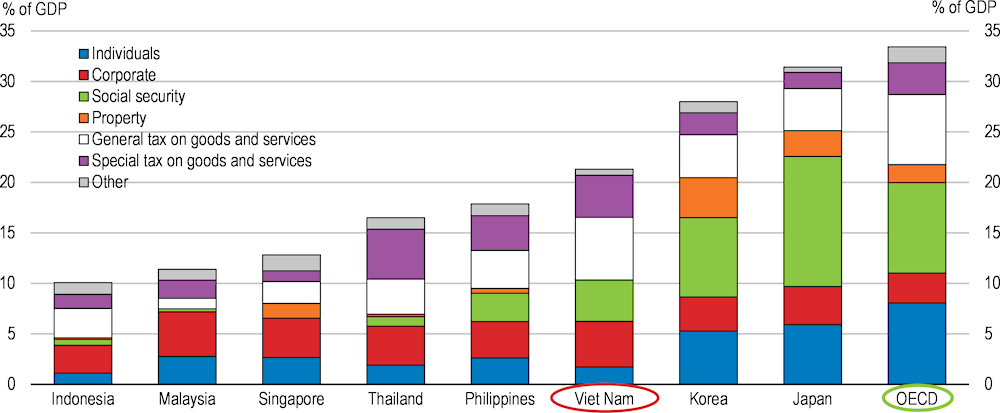

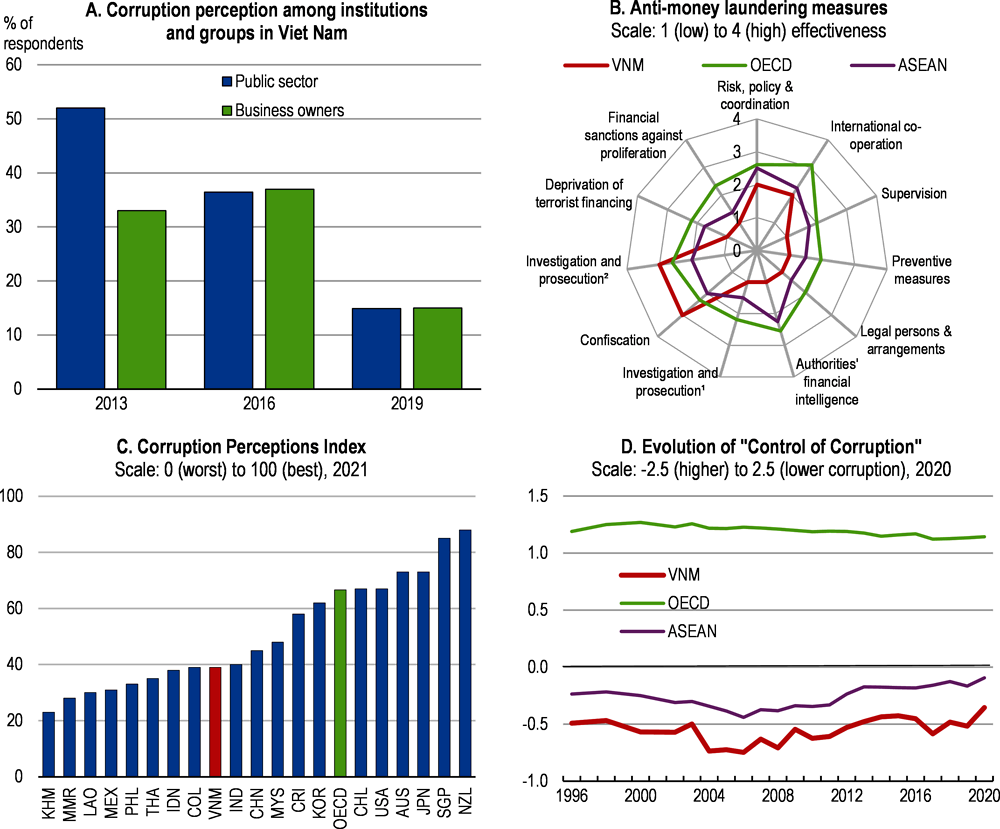

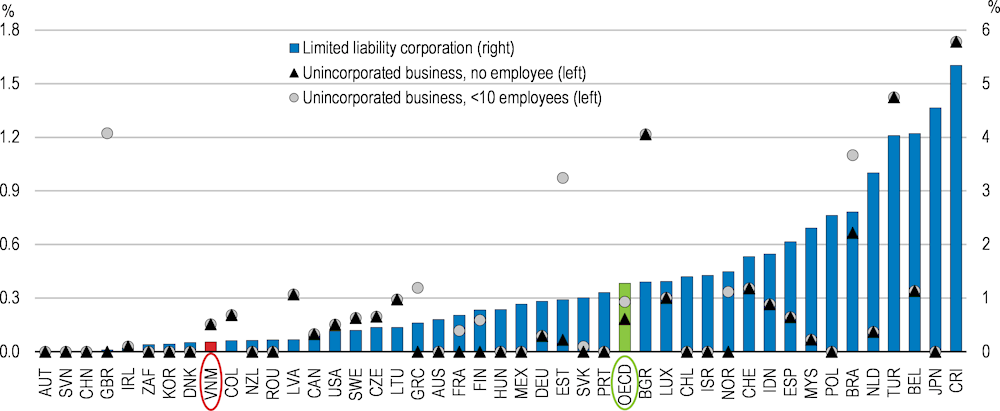

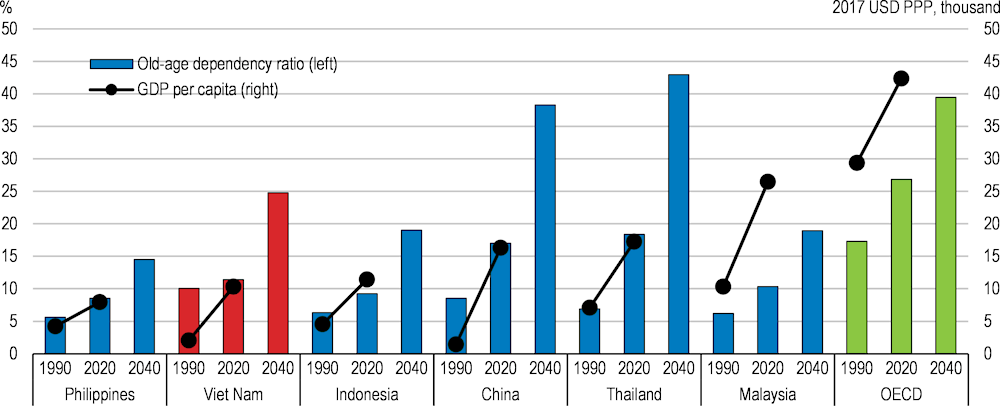

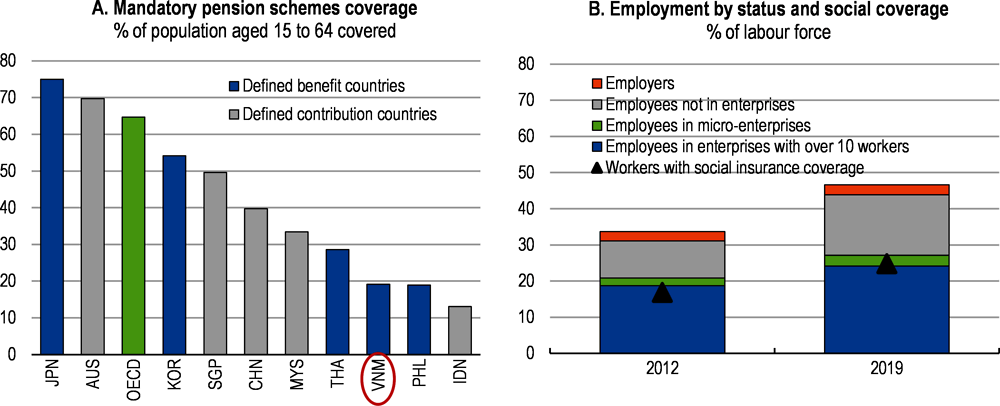

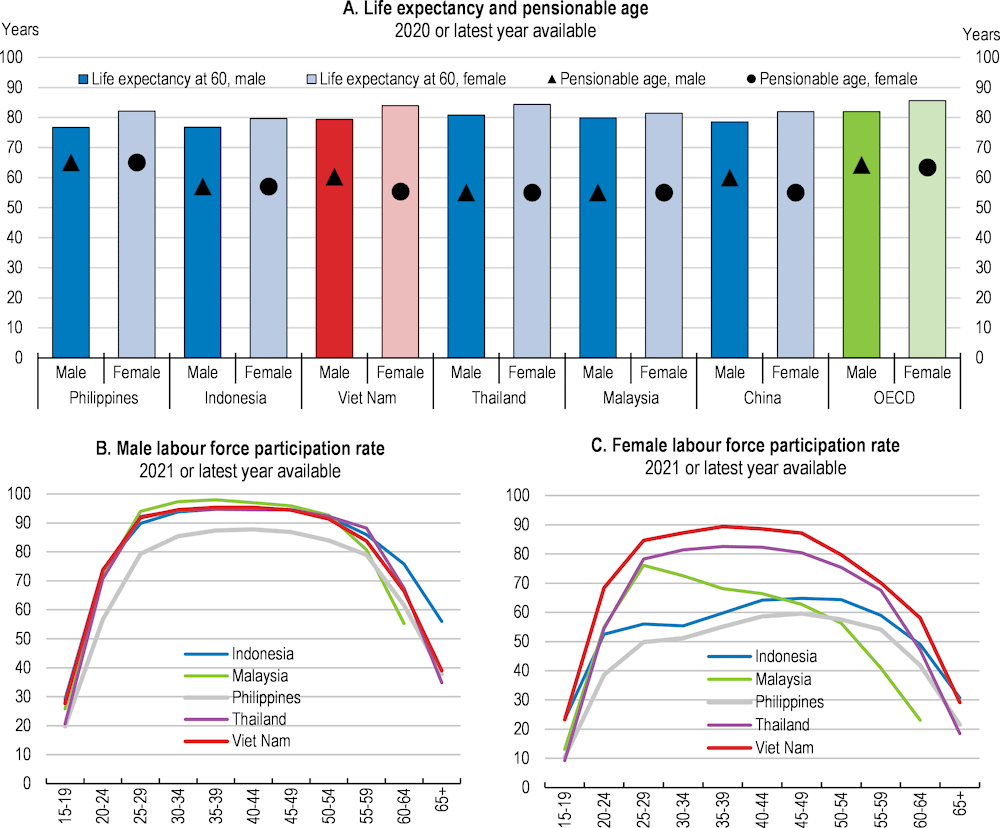

The government could establish more enabling environments for the functioning of the NPL market. Insolvency processes should be sped up, as slower bankruptcy procedure could increase risk premiums and thus lower asset value (OECD, 2021[37]). It has been pointed out that, in Viet Nam, the process of court decision and its enforcement concerning NPL resolution is often lengthy and delayed with backlogs (Asian Development Bank, 2021[39]) (Nguyen, 2021[38]). Viet Nam could consider introducing a fast-track process and improving out-of-court procedures in the context of a more comprehensive insolvency framework for businesses and households (see Chapter 2). The current court process for bankruptcy is rarely used as it is cumbersome and time-consuming. Moreover, a number of European countries established a platform that collects NPL data and serves as a central data warehouse (OECD, 2021[37]). These platforms help improve market transparency, so that they can expand diversity of transaction assets and induce new investors. In 2021, Viet Nam launched a trading floor to nurture the secondary NPL market. The remit of this NPL exchange could be expanded to the collection and storage of debt data.