Oliver Denk

Sebastian Königs

Oliver Denk

Sebastian Königs

Countries’ labour market and social policy response to the COVID‑19 crisis was fast, decisive and helped to avoid an economic and social meltdown. Two and a half years after the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic, this chapter takes stock of the crisis measures still in place, with a focus on the policy areas where action has been particularly important: job retention schemes; unemployment benefits; paid sick leave; active labour market policies; and specific policies for women, young people, frontline workers and racial/ethnic minorities. It also presents an overview of countries’ labour market and social policy challenges and priorities for 2022, including those due to the economic fallout from Russia’s unprovoked war of aggression against Ukraine.

OECD countries responded with unparalleled resolve to the COVID‑19 crisis. Labour market and social policies have been at the forefront of the battle to help to preserve jobs, incomes and livelihoods. By revealing weaknesses in labour markets and gaps in social protection, the crisis has also led some countries to review their long-term policy priorities. Two and a half years after the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic, this chapter takes stock of the measures still in place and presents an overview of countries’ labour market and social policy challenges and priorities in 2022.

The chapter relies largely on countries’ responses to a policy questionnaire that was circulated in autumn 2021. It focuses on the policy areas where action has been particularly important: job retention schemes; unemployment benefits; paid sick leave; active labour market policies; and specific policies for women, young people, frontline workers and racial/ethnic minorities.

Countries’ labour market and social policy response has overall been proportionate to the extraordinary depth of the COVID‑19 crisis. Thanks to the ad-hoc emergency measures taken to complement the standard response of labour market policies and social protection systems, countries were able to support workers’ jobs and incomes and lay the foundations for a strong recovery. By the end of 2021, crisis measures had largely been rolled back, except in the area of active labour market policies.

The urgency with which support had to be provided led in some areas to limited targeting, higher‑than‑needed expenditures and possibly incentive issues. Meanwhile, labour market inequalities may have grown as some groups of heavily affected workers outside of the reach of the standard system were not sufficiently covered by emergency measures. In some cases, policy reforms are needed to close such gaps in labour market and social policy and to further improve labour market resilience in the future; in other cases, the peculiarity of the COVID‑19 crisis may not justify reform. COVID‑19 also disrupted long‑prevailing consumption patterns, shifting demand to different sectors, firms and products; hence, policies to support worker reallocation to jobs in high demand will be particularly important.

The main insights by policy area are as follows:

Job retention schemes: At the height of the crisis in 2020, 37 of the 38 OECD countries had a short-time work or related wage subsidy scheme. Since then, as the recovery progressed, the use of these schemes has strongly declined, from 20% of dependent employment to 0.9% in April 2022 (on average among the countries with available data and a scheme in place at some point during the crisis). Thirteen OECD countries had terminated their schemes entirely by November 2021. Other countries began to target their schemes more tightly, by reducing access (i.e. restricting support to firms most affected) or generosity (i.e. lowering subsidy rates).

Unemployment benefits: Most OECD countries extended unemployment benefits by improving access, notably for workers with insufficient contribution records, lengthening maximum durations and raising benefit generosity to account for the great difficulty of finding work during the crisis. Nonetheless, many countries with comprehensive job retention schemes experienced only small increases in unemployment benefit receipt. By January 2022, only few of the benefit extensions introduced were still in place. Most countries also rapidly and pragmatically extended support for self-employed workers, who often did not benefit from job retention schemes and had lesser access to unemployment benefits. In light of this experience, several countries are currently exploring ways of extending income protection for self-employed workers.

Paid sick leave: Particularly in the early phase of the crisis, paid sick leave played a crucial role in containing the spread of the virus and in protecting workers’ health, jobs and incomes, and many countries quickly extended their systems to improve coverage and reduce employer costs. Attention has since shifted to providing workers affected by “long COVID‑19” with adequate income and employment support.

Active labour market policies (ALMPs): ALMPs have been a crucial component of countries’ crisis response. After being expanded in 2020, budgets increased further in 2021 for both public employment services (in some 80% of countries) and active labour market measures such as training and employment incentives (in 60% of countries). To respond to evolving challenges, countries have taken widespread action, including speeding up digitalisation, increasing remote service delivery and adapting policy design. ALMPs continue to play an important role to reduce worker shortages and support worker reallocation post-COVID‑19.

Labour market and social policies to support women: While more women than men lost their job in the initial phase of the crisis, women’s employment rate has by now improved relative to men’s over the crisis period. Yet, through its peculiar nature as a public-health crisis, COVID‑19 brought a number of specific challenges for women: they are over-represented in the health care workforce, although not generally among jobs with high COVID‑19 exposure; their unpaid work burden at home further increased as formal childcare services were disrupted; and victims of domestic violence were particularly exposed to their abusers during lockdowns. Many countries took measures in the areas of flexible forms of work, leave, childcare and income support to help parents, and often mothers, to cope with the additional unpaid work, and to tackle violence against women and girls.

Specific policies for young people: Young people, although less vulnerable to the virus itself, have been particularly affected by the COVID‑19 crisis. Unlike in previous crises, they received immediate policy attention. Youth labour market outcomes improved quickly with the economic recovery, but some young people may require additional attention and support. These include: young people who graduated during the crisis; unemployed or inactive young people who are not registered with public employment or social assistance services; students with insufficient financial means; and young people experiencing poor mental health.

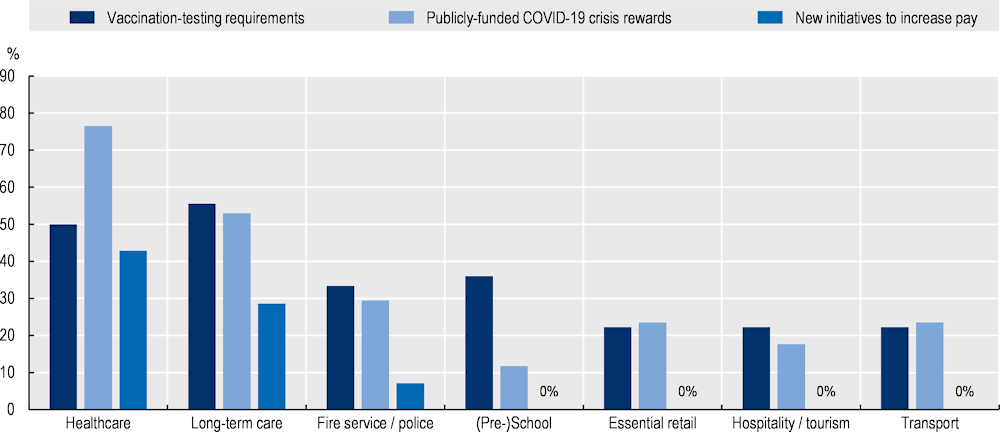

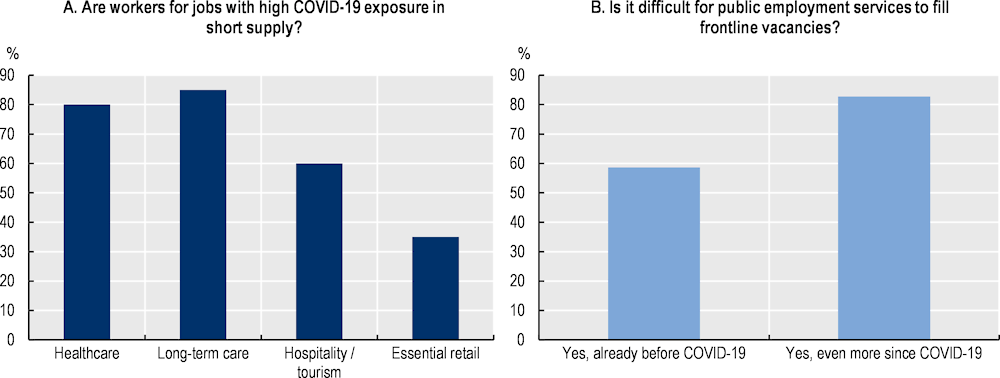

Specific policies for frontline workers: Frontline workers are workers who continued to work in their physical workplace and in proximity to others even at the height of the crisis, such as employees in health care, long-term care or essential retail. Countries have adopted a range of measures to reduce health risks and improve job quality for frontline workers, such as testing or vaccination requirements and initiatives to increase their pay. These measures do not go far enough, however, to permanently improve job quality and to address large worker shortages for frontline jobs.

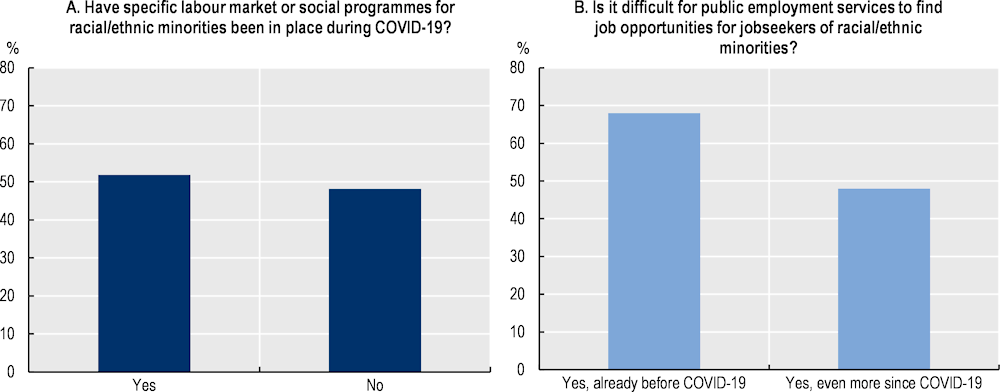

Specific policies for racial/ethnic minorities: Half of OECD countries with available data have had specific labour market or social policies in place to support racial/ethnic minorities in the crisis. Support often pre-dated COVID‑19, but it was particularly valuable in the crisis and sometimes complemented by additional measures. Yet, public employment services have experienced increasing difficulties in finding job opportunities for jobseekers from racial/ethnic minorities. A wider range of programmes, including initiatives to promote upskilling, reduce discrimination and improve labour market attachment, would help jobs of people from racial/ethnic minorities to be more resilient when the next crisis hits.

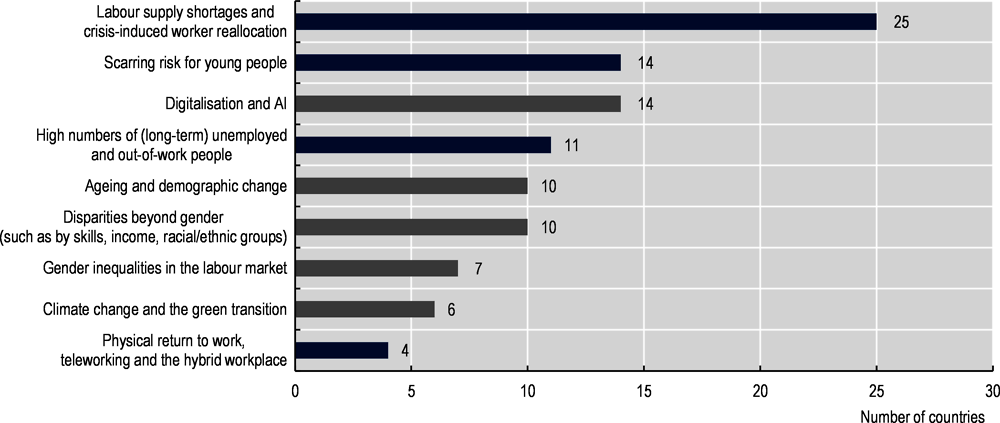

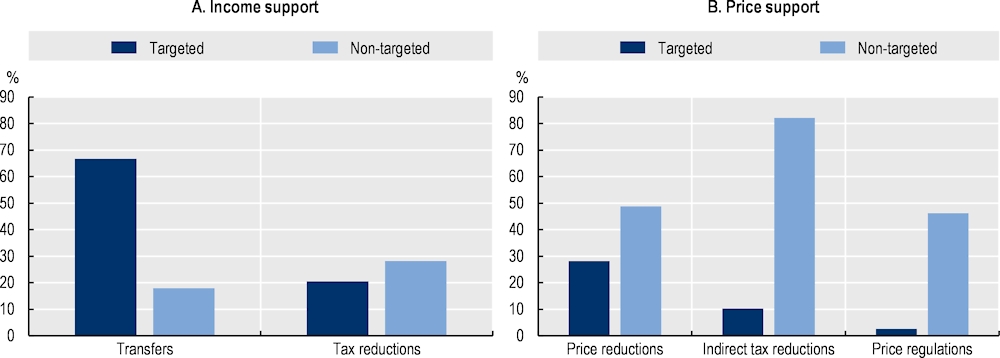

Policy challenges and priorities for 2022: Countries are having to strike a difficult balance between addressing the labour market challenges resulting from the COVID‑19 crisis, mastering the structural transformations underway and supporting a strong and inclusive labour market – all while dealing with the economic and social fallout from Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine. When asked in autumn 2021 about the main labour market challenges, countries’ concerns about the immediate crisis consequences trumped longer-term structural challenges. Key priorities in national recovery plans are strengthening employment services for jobseekers, supporting upskilling, improving labour market inclusion and shaping the transformation resulting from digitalisation and the green transition. The rise in inflation and the fallout from Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine have moved up high on the policy agenda: OECD countries have adopted measures to soften the impact of higher prices, notably of energy, on the cost of living and to help to integrate refugees from Ukraine.

The COVID‑19 pandemic led to an economic contraction not seen in OECD countries in more than half a century. Governments contained the labour market and social fallout from the crisis, shielding many workers and households against job and income losses. As this chapter shows, two and a half years after the COVID‑19 pandemic began, policy has moved on from the crisis response: few crisis measures are still in place and few have been converted into permanent policy that is on automatic stand-by in case of another shock.1

Yet, some of today’s most pertinent labour market and social policy challenges remain connected with the COVID‑19 crisis: significant worker shortages, rising prices and fears of scarring for vulnerable groups such as young people. Policy priorities in OECD countries have been shifting from crisis-fighting to tackling such legacies of the pandemic. COVID‑19 has also refocused policy makers’ attention on the digital and green transformations, while new challenges have emerged or been reinforced because of Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, in particular further increases in the cost of living and a high number of humanitarian migrants, especially in Ukraine’s European neighbours.

The chapter depicts where current labour market and social policy stands and where it is heading. Section 5 provides a detailed update of countries’ COVID‑19 policy response in the areas where action has been especially important: job retention schemes; unemployment benefits; paid sick leave; and active labour market policies. Section 5 puts the spotlight on specific policies for groups that faced particular difficulties during the COVID‑19 crisis: women, young people, frontline workers and racial/ethnic minorities. Section 5 looks beyond the COVID‑19 crisis and presents an overview of countries’ labour market and social policy challenges and priorities in 2022. Section 5 offers concluding remarks.

The analysis relies largely on the OECD Questionnaire on Policy Responses to the COVID‑19 Crisis that was circulated to all OECD countries in autumn 2021. Responses were received from 36 of the 38 OECD countries, though not all of these countries provided complete information for all policy areas. As the policy questionnaire was circulated before Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine, the parts in the chapter that rely on the questionnaire do not account for the latest geopolitical developments.

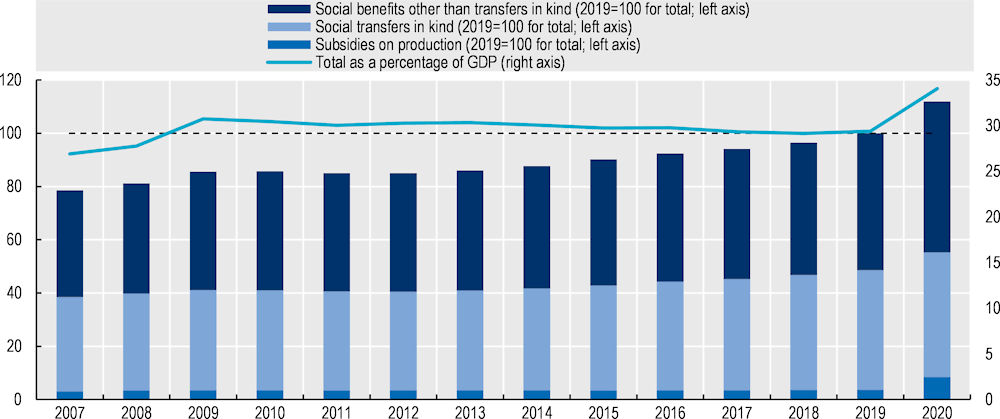

The COVID‑19 pandemic led to a major rise in government expenditure and public social expenditure. While detailed internationally comparable data on public social expenditure during the crisis are not yet available across OECD countries, national accounts can give a first indication of spending trends. According to these data, social expenditure – very broadly defined – increased by approximately 12% in real terms between 2019 and 2020 across 28 OECD countries on average (Figure 2.1). This figure refers to the sum of social transfers in kind (including for health care and education; +4%), social benefits other than transfers in kind (cash payments to households in form of social insurance, including pensions; +11%) and subsidies on production (+294%, with very large cross-country variation). Subsidies on production go beyond social transfers more narrowly and include government support to help employers to keep employees on their payroll (e.g. expenditure for job retention schemes) and government support to the self-employed (ISWGNA, 2020[1]).

Note: In national accounts social benefits to households are broken down into two categories: social benefits other than social transfers in kind and social transfers in kind. Social benefits other than social transfers in kind are typically in cash and so allow households to use the cash indistinguishably from other income, and include pensions and non-pensions benefits. Transfers in kind are related to the provision of certain goods or services (mainly health care and education) for free or at prices that are not economically significant. Subsidies on production are government payments to support enterprises, including by subsidising the payroll of COVID‑19-affected businesses to ensure that the employment relationship is maintained during the crisis. In this figure, the expenditure level is expressed relative to 2019 after adjusting for inflation using the consumer price index. The OECD average is calculated over 28 countries with available data for the entire period.

Source: OECD calculations based on the OECD Annual National Accounts, http://dotstat.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SNA_TABLE14A.

The increase in social expenditure for 2020 was considerably larger than during the global financial crisis (+9% between 2007 and 2010). It corresponds to an increase of 4.7 percentage points of GDP, from 29.4% to 34.1%. In percentage changes, this is broadly in line with the increase in government expenditure as a whole, which rose from 42.7% to 49.5% of GDP (OECD, 2021[2]).

The increase in social expenditure likely reflects primarily the rise in spending on unemployment support and job retention schemes. Across a selection of 17 European OECD countries for which early expenditure estimates are available by programme type, spending on unemployment (including job retention schemes) nearly doubled relative to GDP between 2019 and 2020 (+94%; Eurostat (2022[3])). This is a much larger increase than for the other spending categories, including health (+13%) and family payments (+12%). The large relative expenditure increases on unemployment do not translate into an even more substantial rise in overall social expenditure because, even during crisis times, spending on unemployment only accounts for a small part of overall social spending, about 6% in 2020. Nearly 70% of social spending in 2020 went to pensions as well as health care and sickness benefits.

When the COVID‑19 crisis erupted in spring 2020, nearly all OECD countries used job retention schemes to provide timely and broad-based support to firms and workers affected by physical-distancing restrictions. These job retention schemes sought to preserve jobs and incomes of workers at hard-hit firms by paying subsidies to lower firms’ labour costs against reductions in hours worked. They have taken the form of: i) short-time work schemes that subsidise hours not worked; or ii) wage subsidy schemes that subsidise hours worked but can also be used to top up the earnings of workers on reduced hours. In both cases, contracts of employees remain in force while their work is partially or fully suspended. The analysis of job retention schemes in this section builds on earlier work in the last two OECD Employment Outlooks (OECD, 2021[4]; 2020[5]) and two policy briefs (OECD, 2022[6]; 2020[7]).

Job retention schemes limited costly layoffs and re‑hiring over a temporary shutdown of economic activity. They are also unlikely to have come at the expense of lost productivity growth initially, since the COVID‑19 shock hit high- and low-productivity firms indiscriminately. Hence, it was not only, or mainly, low‑productivity firms that received the subsidy, and the subsidy did not distort the survival chances of firms (Cros, Epaulard and Martin, 2021[8]). As the health and economic situation evolved, concerns about the economic costs of job retention schemes increased. Such economic costs may come principally in two forms: government support may go to jobs that do not need to be supported; or support may go to jobs that will anyway not come back, or come back only after an extended period (e.g. certain segments of the entertainment industry), slowing reallocation of jobs across firms. Evidence from job retention schemes in Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom suggests that these distortive effects have grown as economies recovered (Andrews, Charlton and Moore, 2021[9]; Andrews, Hambur and Bahar, 2021[10]).

Of the 38 OECD countries, all except Mexico operated a universal job retention scheme in the early phase of the COVID‑19 crisis. In 17 OECD countries, a scheme had already been in place before COVID‑19, while 20 OECD countries did not have a scheme and introduced one during the crisis. The countries that had a scheme in place before COVID‑19 often widened its access and increased generosity considerably and in some cases introduced additional schemes (Canada, Denmark). By November 2021, the reference date of the policy questionnaire, 13 of the 20 OECD countries that had introduced a scheme terminated it; hence, 24 of the 38 OECD countries still operated a universal job retention scheme (Table 2.1). Several countries (the Czech Republic, Ireland, the Netherlands, the Slovak Republic), that in November 2021 had operated a scheme, subsequently terminated it.

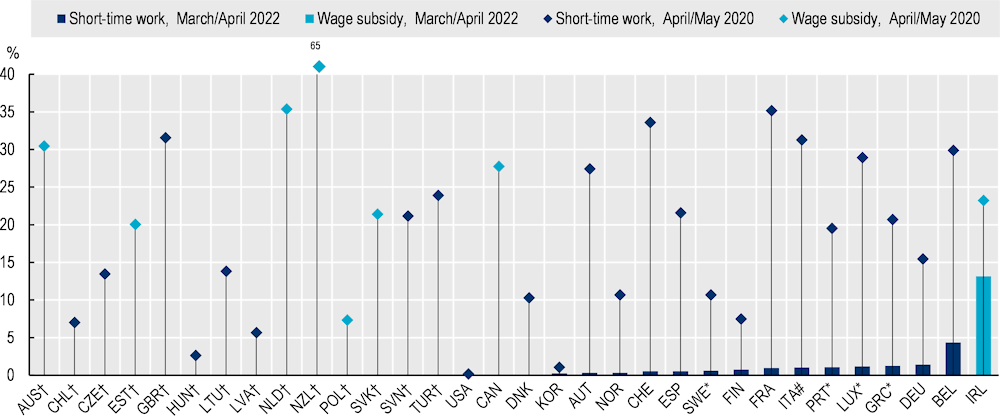

Countries supported an unprecedented number of workers at the beginning of the COVID‑19 crisis through job retention schemes, ten times as many as in the global financial crisis. The ending of the schemes in several countries in the context of a rapid recovery meant that the use of job retention support has fallen strongly: from a peak of 20% of dependent employment to 0.9% in March/April 2022 (on average among the OECD countries with available data and a scheme at some point during the crisis). There has also been a big decline in their use in the countries with schemes that still operated in March/April 2022. Ireland and Belgium were the countries that had the highest numbers of employees on job retention support (Figure 2.2). Belgium continued to make access to its short-time work scheme (chômage temporaire) easier, specifically for companies experiencing problems due to the war in Ukraine (for example supply of resources).

The reduced use of job retention support reflects two factors: lower demand by firms and workers for such support as well as reduced access and generosity offered by the programmes. As the recovery has been progressing, countries have increasingly targeted job retention support to firms and workers in two ways: i) by targeting it to firms, sectors or regions that have been particularly hard hit by physical-distancing restrictions; and ii) by reducing its generosity. The remainder of the section takes stock of the approaches that countries, which did not terminate their programme by November 2021, have taken to limit access and to limit generosity with the aim to target and scale down support.

Situation as of November 2021

|

OECD countries that had a job retention scheme in place already before COVID‑19 |

OECD countries that had introduced a job retention scheme during COVID‑19 that still operated in November 2021 |

OECD countries that had introduced a job retention scheme during COVID‑19 that was terminated by November 2021 |

OECD countries that did not have a job retention scheme during COVID‑19 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United States |

Chile, Colombia, Czech Republic, Greece, Ireland, Netherlands, Slovak Republic |

Australia, Costa Rica, Estonia, Hungary, Iceland, Israel, Latvia, Lithuania, New Zealand, Poland, Slovenia, Türkiye, United Kingdom |

Mexico |

Note: Canada and Denmark introduced additional job retention schemes during COVID‑19 that were terminated by November 2021. Greece introduced two job retention schemes, one of which was terminated by November 2021. The date for this table is 1 November 2021; countries may have terminated or reintroduced job retention schemes subsequently.

Source: National sources and OECD Questionnaire on Policy Responses to the COVID‑19 Crisis.

Note: Take‑up rates are calculated as a percentage of all dependent employees in Q1 2020. † Australia, Chile, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Türkiye and the United Kingdom: Scheme no longer operational or not widely available. *Latest data refer to February 2022 (Greece), December 2021 (Luxembourg), September 2021 (Sweden) and August 2021 (Portugal). # Italy: Data estimated based on the number of authorised hours. United States: Data refer to short-time compensation benefits; only 26 states in the United States have such a programme in place and data are not available at the federal level. No information on take‑up available for Colombia, Costa Rica, Iceland, Israel and Japan. No scheme present in Mexico.

Source: National sources.

Among the countries that as of November 2021 still operated a job retention scheme, several differentiated support by firm size, firm profitability, sector or region (Table 2.2). The intention of such differentiation is to target firms that were most affected by physical-distancing requirements, although some eligibility criteria may be the result of poor firm performance relative to competing firms, which reduces the effectiveness of targeting. Portugal, for example, adapted its scheme in mid‑2020, so that benefits are more generous for companies with greater turnover losses. In Austria, from mid‑2021 only firms in industries directly affected by the lockdown or that encountered a fall in sales of at least 50% between autumn 2019 and autumn 2020 received full job retention amounts. Korea provided special support to firms in 14 hard-hit sectors (including travel and tourism) and 7 “employment-crisis” regions. Japan introduced additional support to firms that shorten business hours in regions with a state of emergency or other government measures. However, half of the countries that as of November 2021 still operated a job retention scheme did not differentiate by firm size, firm profitability, sector or region (Belgium, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Norway, the Slovak Republic, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States).

Situation as of November 2021

|

Differentiation of job retention support |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

By firm size |

By firm profitability |

By sector |

By region |

|

Colombia, Italy, Japan, Korea, Spain |

Austria, France, Ireland, Korea, Netherlands, Portugal |

Austria, France, Italy, Korea, Luxembourg |

France, Japan, Korea |

Note: OECD countries that had a job retention scheme in place in November 2021 but did not differentiate support by firm size, firm profitability, sector or region: Belgium, Chile, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Greece, Norway, the Slovak Republic, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States. No information is available for Canada.

Source: OECD Questionnaire on Policy Responses to the COVID‑19 Crisis.

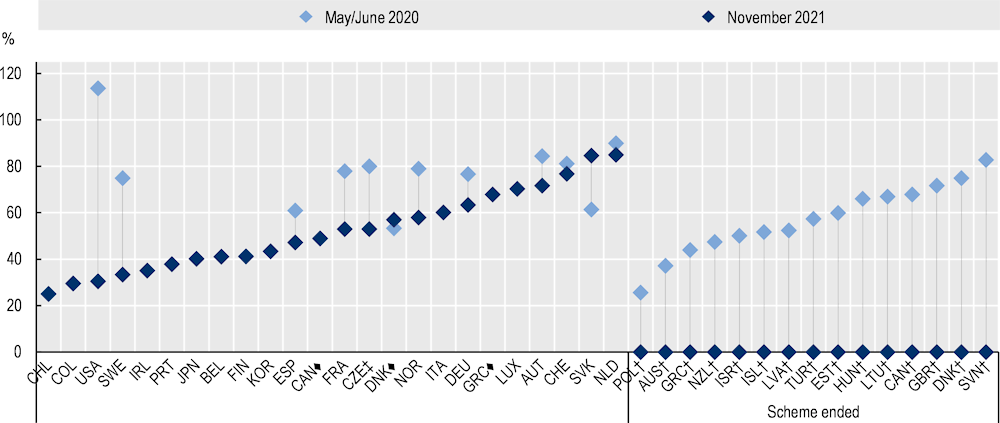

Of the 24 OECD countries that in November 2021 still operated a universal job retention scheme, 10 had reduced its generosity over the course of the COVID‑19 crisis. These reductions were especially large in the United States, Sweden, the Czech Republic and France (Figure 2.3). With the exception of the United States, the reduction in support came at least in part about by greater co-financing requirements for firms. Such co-financing has the advantage that it tends to improve the targeting of the financial support to firms and jobs in need and make it less attractive for workers to stay in jobs that will not become viable again. In line with this, take‑up rates for job retention support were close to three times as high in countries without co-financing as in countries with co-financing (as of November 2021), although with some heterogeneity across countries within each group. In the four countries that reduced government support the most (the United States, Sweden, the Czech Republic and France), these reductions have also been absorbed by workers in the form of lower incomes. Overall, despite these reductions, the public subsidy in November 2021 still tended to cover 50% of the labour cost of a worker who was on a job retention scheme on average in the countries that had a scheme in place. This is still well above the subsidy rates before the COVID‑19 crisis, even in the countries in which the scheme pre‑dates COVID‑19.

Adapting job retention schemes to the evolving crisis has been a major challenge, due to the high uncertainty about the outlook and varied effects of physical-distancing restrictions across groups of firms. The uncertainty about the future evolution of the health situation has made it difficult to plan ahead. Several countries that started scaling back job retention support had to scale it back up as the health situation worsened again. Adjusting eligibility and generosity too frequently may reduce the predictability of the system and undermine its effectiveness. At the same time, maintaining generous support and avoiding multiple adjustments runs the risk of unnecessarily increasing fiscal and economic costs. Overall, the crisis does not appear to have led to a greater adoption of permanent job retention schemes, as the majority of OECD countries that introduced a scheme have ended theirs.

Note: † No scheme in place or scheme not widely available. Canada: There used to be two schemes, the Work-Sharing Program (indicated as ♦, in place in November 2021) and the Canada Emergency wage subsidy (not in place in November 2021). The Czech Republic: May/June 2020 refers to Antivirus Regime 3A, and November 2021 refers to Antivirus Regime B. Denmark: There used to be two schemes, the system of division of labour Arbejdsfordeling (indicated as ♦, in place in November 2021) and the Wage compensation scheme Lønkompensation (not in place in November 2021). Greece: There used to be two schemes, Syn-Ergasia (indicated as ♦, in place in November 2021) and the Special purpose compensation for specific sectors (not in place in November 2021). Norway: The subsidy rate applies to the first 60 days. The calculations do not take mandatory employer contributions for private insurance into account (consistent with the OECD methodology of Taxing Wages). The date for this figure is 1 November 2021; countries may have terminated or reintroduced job retention schemes subsequently.

Source: National sources and OECD Questionnaire on Policy Responses to the COVID‑19 Crisis.

A priority going forward should be to learn from the experience of the COVID‑19 crisis and evaluate the effectiveness of job retention schemes in preserving jobs and supporting job creation. A key aspect of such evaluations should be to analyse the effectiveness of job retention schemes in protecting different groups of workers. Breakdowns of job retention support by different socio-demographic groups are often not available, preventing a more formal assessment of the distributional impact of job retention schemes. It would be important in the future that countries collect these statistics.

The OECD has undertaken one country evaluation to date for Switzerland; another evaluation is underway for Spain. Some OECD countries (Australia, Austria, France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Sweden) have evaluated their programmes or are planning evaluations for 2022‑24, while other countries (Canada, the Czech Republic, Germany, Hungary) have no such plans. The OECD study on Switzerland concludes that the short-time work scheme helped to preserve the jobs and incomes of different socio-demographic groups, including low-educated, temporary-contract and foreign‑born workers (Hijzen and Salvatori, 2022[11]). The Treasury evaluated Australia’s wage subsidy scheme after three and also six months and found that it was important for macroeconomic stabilisation, productivity and business recovery, and that it kept employees and employers connected (The Australian Government the Treasury, 2021[12]). The Cour des Comptes in France lauds the fast and massive rollout of the short-time work scheme, while pointing to insufficient cost control as a major issue (Cour des Comptes, 2021[13]).

Income support for workers affected by job losses was a second pillar of governments’ efforts to cushion the effects of the COVID‑19 crisis on workers and households. In spite of the rapid introduction or expansion of job retention schemes, the COVID‑19 crisis caused massive job losses in the OECD area, although concentrated in a limited number of countries. At the end of 2020, around 22 million jobs had vanished in OECD countries compared with 2019 (OECD, 2021[4]). Finding new employment was difficult or impossible during lockdown periods, including for jobseekers that were already without work prior to the pandemic. Unemployment benefits and other out‑of‑work income support played a vital role in protecting workers and families’ livelihoods during these periods.

As restrictions to economic activity and social life were lifted, jobless numbers fell rapidly, particularly in Canada and the United States, where many millions of workers returned to their jobs following temporary layoffs. Total employment in the OECD returned to pre‑crisis levels at the end of 2021 and continued to grow in the first few months of 2022 – see Chapter 1. Still, substantial numbers of workers, including from sectors where the recovery was subdued, did not manage to return to employment and continued to rely on out-of-work support. In several countries, the support provided during the crisis has been shaping reform agendas, for example because the pandemic highlighted gaps in pre‑crisis support provisions, or because emergency measures altered perceptions of what constitutes adequate income protection.

The majority of OECD countries (32 out of 38) extended entitlements to unemployment benefits during the COVID‑19 crisis. Nearly all of these countries adopted measures during the initial pandemic wave in spring 2020, extending benefit entitlements along one or several of the following three dimensions (Table 2.3):2

Improving access (19 countries) by reducing or entirely waiving minimum contribution periods, or by covering groups of workers who had previously not been entitled (such as workers whose contract was terminated during a probationary period, workers on unpaid leave and workers who had quit their job for a new job offer that fell through when the crisis hit). A number of countries also introduced new unemployment assistance benefits or made extraordinary payments to jobseekers who were not entitled to receive any unemployment benefits.

Extending benefit durations (16 countries) by lengthening durations outright, or by automatically extending entitlements that expired during the peak of the crisis.

Raising benefit amounts (12 countries) by introducing temporary lump-sum top‑ups to unemployment benefits, raising replacement rates, or by lifting benefit floors or ceilings. A number of countries also suspended progressive reductions in benefit amounts for those with longer unemployment spells.

By lengthening benefit durations and raising generosity, countries accounted for the fact that jobseekers, and notably those who had already been unemployed when the crisis hit, had only poor chances of finding new work at a time when large parts of the economy were effectively at a standstill. The type and scope of countries’ benefit extensions depended partly on the accessibility and generosity of their income support systems at the onset of the crisis.

Extraordinary expansions in unemployment benefit entitlements for dependent workers relative to January 2020

|

Improved access |

Extended benefit duration |

Raised benefit generosity |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Spring 2020 |

January 2021 |

January 2022* |

Spring 2020 |

January 2021 |

January 2022* |

Spring 2020 |

January 2021 |

January 2022* |

|

|

Australia** |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|||||

|

Austria |

● |

||||||||

|

Belgium |

● |

● |

● |

||||||

|

Canada |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|||||

|

Chile |

|||||||||

|

Colombia |

● |

● |

|||||||

|

Costa Rica |

|||||||||

|

Czech Republic |

|||||||||

|

Denmark |

● |

● |

|||||||

|

Estonia** |

● |

● |

|||||||

|

Finland |

● |

● |

● |

||||||

|

France |

● |

● |

● |

||||||

|

Germany |

● |

||||||||

|

Greece |

● |

● |

|||||||

|

Hungary |

|||||||||

|

Iceland |

● |

● |

|||||||

|

Ireland |

● |

● |

● |

||||||

|

Israel |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

||||

|

Italy |

● |

● |

|||||||

|

Japan |

● |

● |

● |

||||||

|

Korea |

● |

● |

|||||||

|

Latvia |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|||||

|

Lithuania |

● |

● |

|||||||

|

Luxembourg |

● |

||||||||

|

Mexico |

|||||||||

|

Netherlands |

|||||||||

|

New Zealand** |

● |

● |

|||||||

|

Norway |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

Poland |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|||||

|

Portugal** |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|||||

|

Slovak Republic |

● |

||||||||

|

Slovenia |

● |

||||||||

|

Spain |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|

|

Sweden |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|||

|

Switzerland |

● |

||||||||

|

Türkiye |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|||||

|

United Kingdom |

● |

||||||||

|

United States*** |

● |

● |

● |

● |

|||||

|

# of countries |

19 |

12 |

5 |

16 |

11 |

3 |

12 |

12 |

6 |

Note: The table documents changes in either “first‑tier” unemployment insurance or “second‑tier” unemployment assistance programmes. A black dot for spring 2020 indicates that unemployment benefits were extended relative to the situation in January 2020. A black dot for January 2021 / January 2022 indicates that some of these extensions, or new extensions, were (still) in place, again relative to January 2020. A blank cell indicates that no extensions are in place (anymore) relative to the situation in January 2020. * Data for 2022 are preliminary; shaded cells for Israel indicate that information for 2022 is missing. ** Some unemployment benefit extensions are not shown in the table because they do not directly relate to the COVID-19 crisis: Australia and New Zealand increased earnings disregards and benefit levels after the expiry of their temporary COVID-19 measures in 2021 and 2022; Estonia made it possible for jobseekers to combine temporary work and receipt of unemployment benefits under certain conditions in September 2020; Portugal raised the amount of its Unemployment Social Allowance for households with children from 2022. *** Information for the United States refers to the federal level.

Source: OECD (2020[5]), OECD Employment Outlook 2020, https://doi.org/10.1787/1686c758-en, and the OECD tax-benefit database, oe.cd/TaxBEN.

The benefit extensions carried out at the onset of the crisis were nearly always explicitly temporary, often initially time‑limited up to summer 2020. As the pandemic evolved in autumn 2020, many countries extended or reinstated these measures, while others introduced new ones. This included, for example, an extension of the income‑related component of unemployment benefits in Iceland, the temporary introduction of an unemployment assistance benefit in Poland (the Solidary Allowance) and lump-sum payments to recipients of unemployment insurance and unemployment assistance benefits in Austria.

By January 2021, over half of all OECD countries (23 out of 38) still had some form of unemployment benefit extensions in place relative to the pre‑crisis situation in January 2020. Those were mainly measures initially taken during the first pandemic wave and then extended into 2021, sometimes with adjustments to maintain the greater access and coverage, the longer benefit durations (e.g. the Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation in the United States) or the higher benefit levels (e.g. the Coronavirus Supplement Payments in Australia, the suspension of benefit reductions for longer unemployment spells in Belgium and higher benefit floors and ceilings in Sweden). A few countries replaced earlier extensions through new, more targeted or less generous measures to account for the developing public-health and labour market situation. Canada, for example, phased out its Canada Emergency Response Benefits and instead introduced temporary changes to simplify access, increase benefit durations and raise generosity of its Employment Insurance programme. Some also introduced entirely new measures that were not directly related to those implemented in spring 2020: Estonia increased replacement rates during the first 100 days of benefit receipt, as well as the benefit floor and ceiling; France shortened the minimum contribution period from six to four months; and Korea introduced a new unemployment assistance scheme, the National Employment Support Programme.

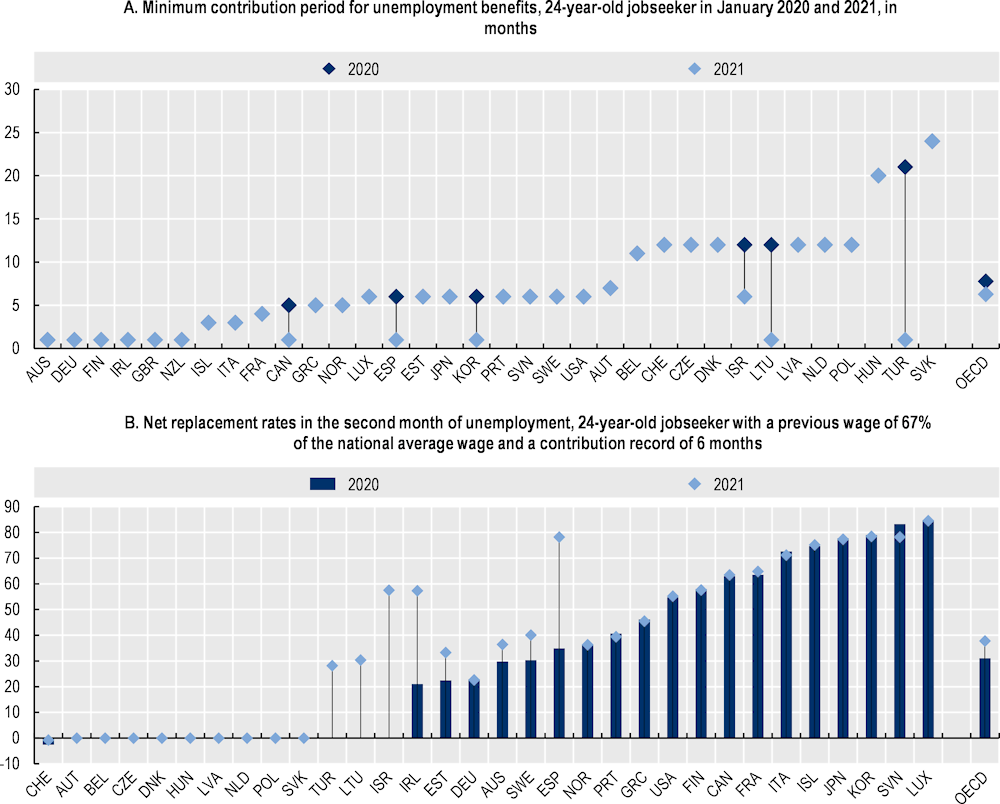

Together, these measures considerably eased access to unemployment benefits for some groups. In January 2021, a 24‑year‑old jobseeker with a single month of prior work was entitled to unemployment benefits in 11 OECD countries, up from six in January 2020 (Figure 2.4, Panel A). Lithuania, Spain and Türkiye had completely scrapped minimum contribution requirements, and Israel substantially eased them; such reductions in contribution requirements are especially consequential for labour market entrants. In Canada and Korea, benefit entitlements relate to newly introduced unemployment assistance benefits.

In a small number of countries, unemployment benefit levels were still higher in January 2021 than before the crisis, as shown by simulations of the OECD TaxBEN model. Calculations refer to net replacement rates, the share of previous net earnings replaced through unemployment benefits, after two months of unemployment for a 24‑year‑old jobseeker, assuming a six‑month work history (Figure 2.4, Panel B). Substantial increases in the net replacement rate in several countries reflect the fact that this jobseeker would not have qualified for unemployment benefits at all before the crisis. Indeed, relative to its pre‑crisis level, the net replacement rate increased most in countries that substantially lowered their minimum contribution requirements (Israel, Lithuania, Spain and Türkiye). The net replacement rate for a young jobseeker was also above pre‑crisis levels in Ireland (due to the continued Pandemic Unemployment Payment), Australia (Coronavirus Supplement Payments), and Estonia and Sweden (increased unemployment benefit levels).

By January 2022, a little less than two years into the pandemic, unemployment benefit extensions introduced during the crisis had expired in most of the countries for which information is already available. Exceptions include the Nordic countries, which had maintained reduced work requirements (Norway, Sweden), longer maximum benefit durations (Norway) or higher benefit levels (Iceland, Norway, Sweden). In Japan, the extended unemployment benefit durations introduced in June 2020 were still in place. Ireland’s Pandemic Unemployment Payment was briefly reopened for new applications as the country introduced new public‑health restrictions in December 2021. In Spain, the generous extensions to unemployment benefits were suspended in March 2022. In three countries, unemployment benefit extensions carried out during the crisis have been permanent: Korea’s new unemployment assistance programme, introduced in January 2021, remains in place; Estonia and Poland have maintained their higher unemployment benefit levels.

Note: Both panels include unemployment insurance and assistance benefits. 24‑year‑old living alone, with previous earnings at 67% of the national average wage. Data refer to 2019 and 2020 for New Zealand and the United Kingdom (TaxBEN implements COVID‑19 emergency measures already in 2020 for these countries as their reference date is at the beginning of their fiscal year in April, in contrast to 1 January for the remaining countries). The negative net replacement rate in Switzerland in Panel B reflects obligatory private health care contributions.

Source: OECD TaxBEN model (version 2.4.0) http://oe.cd/TaxBEN.

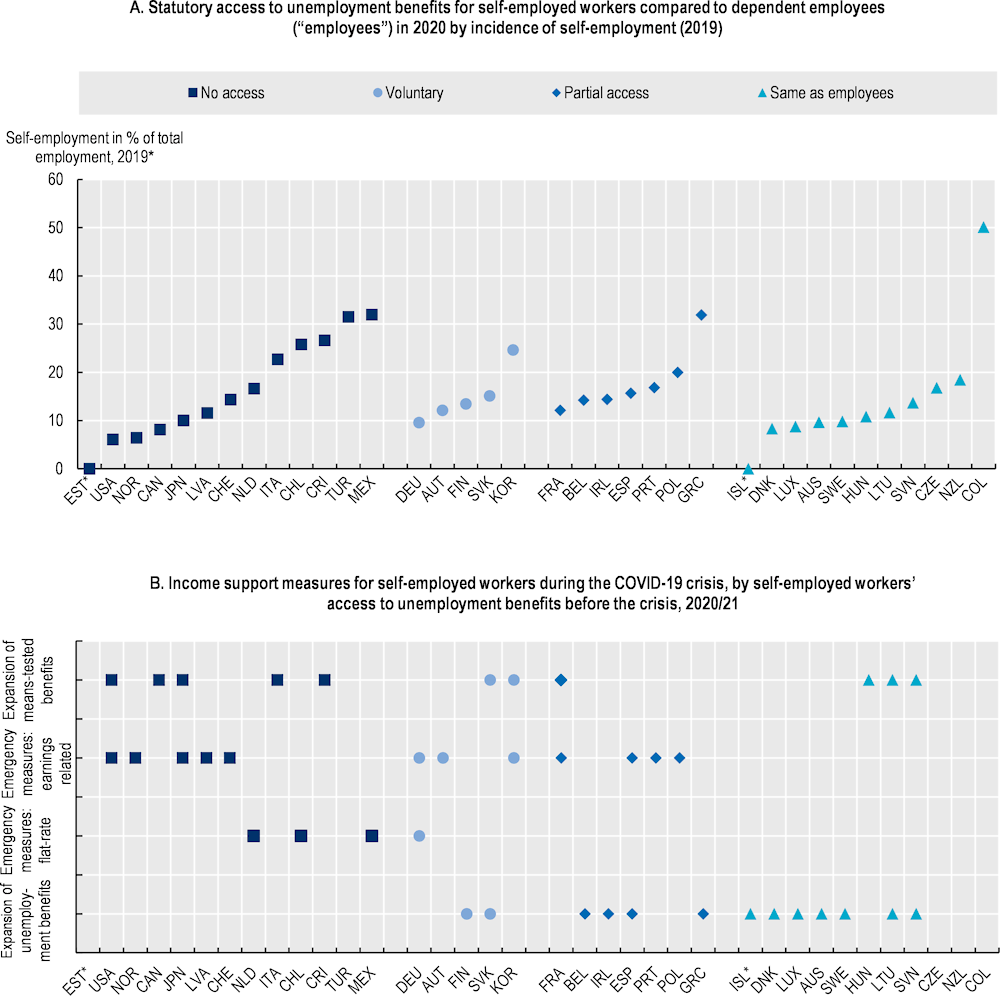

Self-employed workers have been particularly vulnerable to income losses during the crisis as typically they did not benefit from job retention schemes and often had less access to unemployment insurance benefits than dependent workers. At the onset of the crisis, only 11 of 36 OECD countries with available information offered self-employed workers the same unemployment protection as dependent employees; another seven offered partial access, i.e. with lower amounts and/or more stringent eligibility criteria than for dependent employees. In five countries, the self-employed had the option to join a voluntary unemployment insurance scheme, but membership rates were often low – under 1% of all self-employed workers in Austria and Korea, 3% in the Slovak Republic and 10‑15% in Finland (European Commission, 2022[14]; Park, 2020[15]). Thirteen countries did not offer any unemployment insurance benefits for self‑employed workers. This incomplete coverage left a significant part of the labour force exposed as the crisis hit: across the OECD on average, one in six workers are self-employed, with self-employment much more frequent in Mexico (one in three workers), Italy and Korea (one in four, Figure 2.5, Panel A).

At the onset of the COVID‑19 crisis, countries who already provided (some) self-employed workers with unemployment benefits were able to shore up support using existing structures: in Denmark, for example, self-employed workers could retrospectively join an unemployment insurance fund by paying a year’s contributions if they were affected by containment measures, and Ireland suspended minimum contribution requirements to its unemployment benefit programme.

Countries that had no systems in place to assess affected workers’ previous earnings and entitlements had to either create such structures quickly or to adapt their minimum income benefits. Austria, Norway, Switzerland and the United States, among other countries, introduced new emergency benefits for self‑employed workers that were tied to previous earnings or crisis-related losses. But carefully assessing previous income (especially the fluctuating income of the self-employed) takes time, particularly in the absence of established administrative procedures to do so. Some countries therefore relied on the self‑certification of losses, especially at the beginning of the crisis (e.g. Austria), risking precision in targeting. Others circumvented time‑consuming earnings assessments by providing flat-rate benefits (e.g. Canada, France, Italy). Chile, Germany, the Netherlands and to a lesser extent Mexico extended their existing minimum income programmes to make them more accessible to self-employed workers. These programmes are typically not designed for sudden (albeit catastrophic) income losses, but to support the long-term needs of low-income households, and are therefore often associated with careful means and asset tests. Extensions therefore included the easing or suspension of asset tests (thus allowing self-employed workers to draw benefits while keeping their business capital and any savings) and income tests on partner income (Figure 2.5, Panel B).

Already before the COVID‑19 crisis, many countries had been exploring how to shore up access to out‑of‑work benefits for self-employed and other non-standard workers. The pandemic made the need for equal access to out-of-work support for all labour market groups even more apparent: countries had to develop new programmes quickly without being able to carefully consider their design and implementation, leading to both gaps in emergency protection and overpayments. Unlike insurance‑based unemployment benefits, emergency support measures are also not balanced by contributions, perpetuating the existing differences in labour costs between employment forms (OECD, 2019[16]).

In light of this experience, several countries are currently considering extending income protection for self‑employed workers. Italy introduced a new unemployment benefit for the previously uncovered group of para-subordinate professionals (unlicensed professionals, such as web-designers, who are legally self‑employed but economically dependent on one or very few clients) on an experimental basis from 2021 to 2023. The benefit does not insure against total loss, but significant reductions in income (at least 50% over the last three years) and cushions half of this loss. It is therefore well tailored to the circumstances of freelancers relying on a small number of clients. Similarly, Germany is considering extending access to voluntary unemployment benefits for self-employed workers without an insurance record as dependent employees. In France, there are plans to extend unemployment support to those with unviable businesses (currently only those whose business has been closed by court order are eligible).

Note: Panel A: Gaps between dependent employees (full-time open-ended contract) and self-employed workers. If there are several legal forms of self‑employment in a country, the chart refers to the most prevalent form, excluding farming and liberal professions. For Italy, the chart refers to craftspeople, shopkeepers/traders and farmers, and not to para-subordinate workers, who are covered by a separate scheme. For Portugal, the chart refers to dependent self-employed workers. For Belgium, “partial access” refers to the droit passerelle, a separate non-contribution-based programme for self-employed workers. For Germany, “voluntary access” refers to the unemployment insurance benefit Arbeitslosengeld I, not to the needs-based unemployment assistance benefit Arbeitslosengeld II that self-employed workers may also claim. In the Czech Republic, self-employed workers are statutorily insured at half of their taxable income but may choose a higher contribution base. Partial access: self-employed workers are insured through a different scheme, receive lower benefit amounts and/or have more stringent entitlement criteria than dependent employees. “No access”: compulsory for dependent employees but the self-employed are included. * No data on the incidence of self-employment in Estonia and Iceland. Data on self-employment incidence refer to 2018 for Norway and 2015 for the Slovak Republic. Panel B: “Expansion of unemployment benefits” includes easier access (e.g. shortening of minimum contribution periods), longer durations or higher amounts. In countries that did not cover the self-employed previously, it may also mean that self-employed workers gained access. Similarly, expansion of means-tested benefits includes the easing of means and/or asset tests as well as increased amounts.

Source: OECD Questionnaire on Policy Responses to the COVID‑19 Crisis supplemented with information from the OECD Tax-Benefit Database (https://www.oecd.org/social/benefits-and-wages/); MISSOC (2020), Social protection of the self-employed, Spasova et al. (2017), Access to social protection for people working on non-standard contracts and as self-employed in Europe, and ESPN (2021), Social protection and inclusion policy responses to the COVID‑19 crisis for European countries; Government of Canada (2022), EI benefits for self-employed people for Canada; OECD (forthcoming), Income security during joblessness in the United States: Design of effective unemployment support for the United States. Incidence of self‑employment: OECD Labour Force Statistics, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/data/labour-force-statistics/summary-tables_data-00286-en.

One argument against unemployment protection for the self-employed is that running a business does – and should – imply risk, because self-employed workers control the success of their businesses in ways that employees do not. Providing them with unemployment insurance can therefore be prone to significant moral hazard – with no employer to confirm a layoff it is difficult to establish whether a loss of income is caused by a (prior) lack of effort or external circumstances leading to business failure (OECD, 2018[17]). However, not all self-employed activity is equally entrepreneurial, some self-employed workers are economically dependent on one or very few clients, and moral hazard can also be a challenge for dependent employees. Careful policy design and complementary measures can mitigate moral hazard, e.g. making benefit receipt conditional on active job search and other activation measures, including training (OECD, 2019[16]). As countries seek to ensure effective social protection in a changing world of work, one pragmatic way to circumvent moral hazard problems would be to insure self-employed workers only for income losses during sector- or even economy-wide shocks, as opposed to idiosyncratic ones (Franzini and Raitano, 2020[18]). This would limit moral hazard (although seasonality needs careful consideration), and provide protection in future crises, along with access to activation, training and employment support services. Only partially insuring the risk of job loss can also lower contributions relative to standard workers, an advantage given that the self-employed are necessarily liable for both employee and employer contributions.

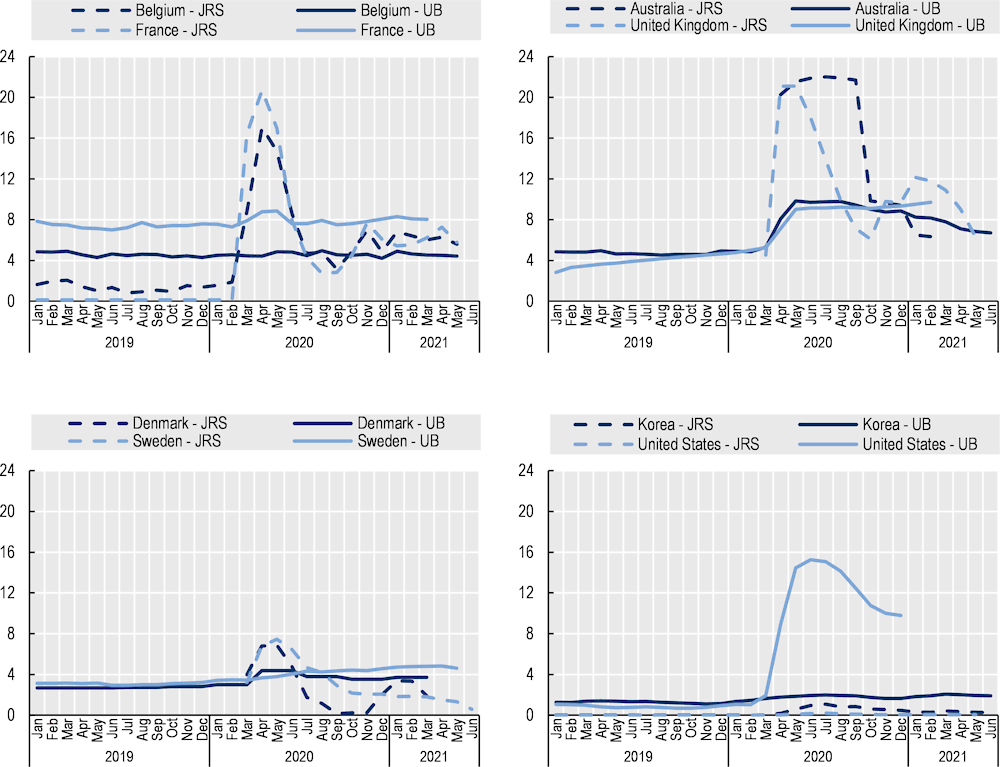

In spite of countries’ measures to improve the access to, and coverage of, unemployment benefits during the crisis, including for self-employed workers, receipt numbers have mostly remained low.3 This is illustrated in Figure 2.6, which depicts for a selection of countries with available data trends in the monthly number of recipients of unemployment benefits, and job retention support, between 2019 and mid‑2021, expressed relative to the working-age population. Countries with comprehensive job retention schemes experienced massive temporary inflows into these systems in the initial phase of the crisis while unemployment benefit receipt rates remained largely stable. This applies to Belgium and France (Panel A), two countries with pre‑existing short-time work schemes, where unemployment benefit receipt numbers remained virtually flat. Australia and the United Kingdom experienced even slightly larger inflows into their newly established wage subsidy schemes, while unemployment benefit receipt rose by 4‑5 percentage points (Panel B). Also in Denmark and Sweden, two countries where the reduction in working hours during the crisis was lower (OECD, 2021[4]), the pre‑existing job retention schemes that got activated (in Sweden) or extended (in Denmark) in March 2020 absorbed most of the labour market shock. At the peak of the crisis, around 7% of the working-age population received job retention support, while the share of unemployment benefit recipients rose by only about 1 percentage point (Panel C). These trends contrast with the numbers observed in the United States, where the pre‑existing job retention scheme – the Short‑Time Compensation – remained marginal throughout the crisis. Here, the labour market shock was nearly fully absorbed by the generously extended unemployment benefit system, and the number of claimants, including workers on temporary layoff, reached nearly 16% of the working-age population. In Korea, the labour market shock largely translated into reductions in hours worked while the receipt numbers for both job retention support and unemployment benefits remained very low in international comparison (Panel D).4 This may partly reflect weak benefit coverage of the non‑employed in Korea (OECD, 2021[4]).

Note: In some countries, the figures represent an aggregation across different schemes of the same benefit type. For Denmark, France and Sweden, complete JRS figures are missing before March 2020. For Denmark, JRS numbers refer to two schemes, the pre‑existing work sharing scheme and the wage compensation scheme introduced in March 2020; monthly figures for both UB and JRS were interpolated from quarterly time series. For the United States the figures reported are claimant, not recipient, numbers. JRS figures deviate from those shown in Figure 2.2 mainly because they are expressed relative to the working-age population, not dependent employment. For details on the programmes included for each country and methodological notes, please consult the SOCR-HF database.

Source: OECD Social Benefit Recipients – High-Frequency database (SOCR-HF), https://www.oecd.org/fr/social/soc/recipients-socr-hf.htm.

These trends illustrate the different – and lesser – role that out-of-work income support has played during the COVID‑19 crisis compared to previous economic downturns. In previous crises, unemployment insurance benefits represented the “first line of defence” of social protection systems, supporting the incomes of workers who lost their jobs often for extended time periods. During the global financial crisis, for example, the number of unemployment insurance benefit recipients relative to the working-age population rose by 90% between 2007 and 2009 across the OECD and declined only little in 2010 (OECD, 2014[19]). During the current crisis, broadly accessible and generous job retention schemes represented this “first line of defence” in most countries, temporarily protecting jobs rather than just incomes, and taking most of the pressure off unemployment benefit systems.

During the COVID‑19 pandemic, paid sick leave5 played a crucial role in containing the spread of the virus and protecting simultaneously workers’ health, jobs and incomes (OECD, 2020[20]). First, paid sick leave complemented other epidemic containment measures, reinforcing their action. The introduction of temporary paid sick leave for COVID‑19‑related diseases in the United States, for example, contributed to an 18% decrease in full-time presence at the workplace and an 8% increase in staying at home, as evident from cellular mobile data (Andersen et al., 2020[21]). Its introduction led to an estimated one daily prevented COVID‑19 case per 1 300 workers, or a 56% lower case number (Pichler, Wen and Ziebarth, 2020[22]). Second, paid sick leave contributed to protecting workers’ health by providing income support to workers (potentially) exposed to the virus, therefore permitting them to self-isolate. Survey data for Israel collected in the lead‑up to the COVID‑19 outbreak indicated that 97% of adults reported they would quarantine if their wages were compensated, whilst compliance would drop to 57% without such compensation (Bodas and Peleg, 2020[23]). Third, paid sick leave helped to preserve jobs by reducing pressure on unemployment benefit systems and job retention schemes. Job losses in the United States between 8 March and 25 April 2020, measured by the number of initial unemployment insurance claims, were larger in the 38 states that did not have statutory paid sick leave policies in place (Chen et al., 2020[24]). Fourth, paid sick leave supported workers’ incomes by ensuring an uninterrupted continuation in income for those either affected by the virus or otherwise asked to self-isolate. The temporary expansion of paid sick leave in several countries to parents who had to take care of children as schools were closed further strengthened its role as an income security instrument (OECD, 2020[20]).

Most OECD countries reacted to the outbreak of the COVID‑19 pandemic with paid sick leave extensions of various types, improving the accessibility and increasing the generosity of the system. Most of the measures taken, however, were temporary and remained limited to people affected by COVID‑19. The main measures included:

Easier access and broader coverage: some countries facilitated access to benefits by delaying or waiving the need for medical certification or allowing online applications. Other countries lowered the qualification requirements to entitlement to paid sick leave. Canada, for example, initially reduced the entitlement requirements from 600 to 120 insurable hours of employment (increased again to 420 hours as of September 2021). Over 25 OECD countries eased or extended access to sickness benefits for self-employed workers who were sick with COVID‑19 or in quarantine (OECD, 2020[20]). Before the pandemic, self-employed were entitled to sickness benefits in many countries, but access was often limited or voluntary (OECD, 2019[25]).

Access to paid sick leave during quarantine: more than half of all OECD countries extended benefit coverage also to quarantined workers or introduced new crisis payments for both sick and quarantined workers. Australia, for example, introduced a special unemployment benefit that people who are sick from COVID‑19 can claim as soon as they have exhausted their accrued employer-provided sick-pay entitlements (OECD, 2020[20]).

Abolition of waiting periods: about one in three OECD countries temporarily abolished waiting periods, thus improving workers’ income security and slightly raising the implied income replacement rates. France, for example, waived its waiting period for both employer-provided sick pay and sickness benefits. Ireland increased benefit levels and the maximum duration of its sickness benefits, and waived the waiting period (OECD, 2020[20]).

Exemptions of employer costs: about one in three OECD countries also introduced measures to support or eliminate employer costs for sick pay (ESPN, 2021[26]). In Luxembourg, for example, a temporary legal change allowed the National Health Fund to pay for the sick leave from the first day instead of taking over only after the end of the month of the 77th sick day.

Introduction of hitherto non-existing entitlements: before the pandemic, two OECD countries stood out as having no statutory regulations on paid sick leave in place. Both countries decided to react. The United States, which had no federal paid sick leave requirements6 before the pandemic, introduced two weeks of mandatory paid sick leave for workers with COVID‑19‑related symptoms or in quarantine, paid by the employer initially but fully reimbursed by the federal government (the programme expired in 2021). Korea provided exceptional sickness benefits through its 2015 Epidemic Act to workers who were hospitalised because of COVID‑19 (OECD, 2020[20]).

Limited additional measures were taken to strengthen paid sick leave systems as further waves of the pandemic unfolded, but about half of the extensions made during the first pandemic wave or during the first year were still in place in December 2021 (Table 2.4). A number of countries with only basic sick leave systems, or no such system at all, are considering structural reforms. This includes in particular Ireland, which published a draft Sick Leave Bill with statutory employer-provided sick pay in November 2021 (yet to be approved by parliament at the time of writing), Korea, which is piloting a government‑provided sickness benefit from July 2022 onwards, and New Zealand, which is currently developing a government‑provided social insurance that will cover both unemployment and temporary sickness.7

Extensions in paid sick leave for employees (employer-provided sick pay and/or government-provided sickness benefits) since January 2020, situation as of December 2021

|

|

Extensions still in place |

Extensions expired |

|---|---|---|

|

Reduction in waiting period |

Chile, Denmark, Estonia, France, Portugal, Spain, Sweden |

Canada, Ireland, Latvia |

|

Increase in benefit level |

Australia, Belgium, Chile, Finland, Greece, Italy, Korea, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, Spain |

Canada, Czech Republic, Ireland, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, United States |

|

Reduction in employer costs for sick pay |

Austria, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Korea, Norway, Spain, Sweden |

Latvia, Luxembourg, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, United States |

Note: All changes are limited to COVID‑19 except in Belgium, Norway and Sweden where the measures include all types of illness. The changes refer to measures affecting employees though some include self-employed. Countries with missing information are not reported.

Source: OECD Questionnaire on Policy Responses to the COVID‑19 Crisis; OECD (2020[20]), “Paid sick leave to protect income, health and jobs through the COVID-19 crisis”, https://doi.org/10.1787/a9e1a154-en; ESPN (2021[26]), Social protection and inclusion policy responses to the COVID‑19 crisis, https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?langId=en&catId=89&newsId=10065&furtherNews=yes.

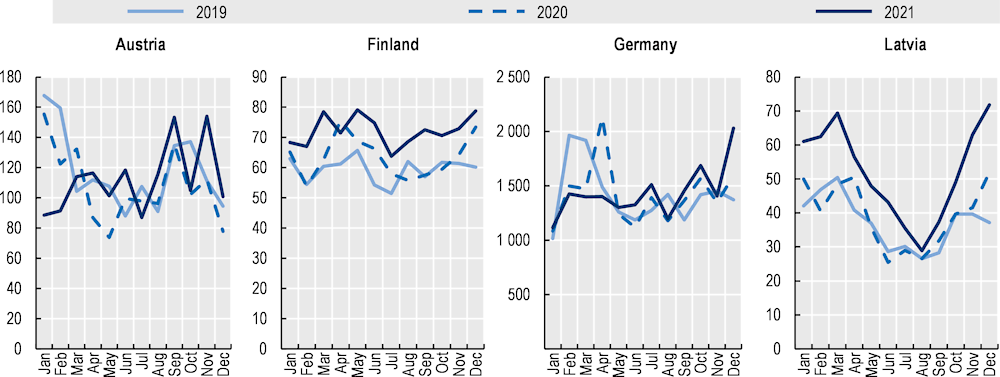

The changing role of paid sick leave systems over the course of the pandemic, and their interaction with other policy interventions, is reflected in benefit take‑up. Data for four European countries show a notable increase in take‑up at the onset of the pandemic in spring 2020 in Finland and Germany and smaller upticks in Latvia and possibly Austria (Figure 2.7). The rapid shift to teleworking in many occupations and the introduction or expansion of generous job retention schemes limited further rises in paid sick leave numbers. Workers became less exposed to the virus, and if they were, many continued receiving job retention support rather than having to go on paid sick leave. As a result, take‑up up rates declined again. In the subsequent phases of the crisis, changes in take‑up reflect the development of the pandemic and societies’ public-health responses – with variation over time and across countries in vaccination, incidence, and hospitalisation rates, the abolition of extensions implemented in paid sick leave systems, and the recognition of “long COVID‑19” as an occupational disease (see below). The most recent available data, for late 2021, show an increase in take‑up of paid sick leave with the emergence of the Omicron variant, when – in the context of high vaccination rates and a much lower hospitalisation risk – higher COVID‑19 infection rates did not prompt costly containment measures such as lockdowns. Indeed, many countries responded to rising incidence rates and associated worries about the continuation of essential services and infrastructure by easing quarantining rules rather than further adjusting paid sick leave regulations or introducing further confinement measures. Overall, the take‑up of paid sick leave in the four countries has only been a little higher during the COVID‑19 pandemic than in 2019, and “traditional” seasonal variation has often been larger than the variation during the pandemic.

Note: Monthly averages for Finland and Latvia, numbers at the beginning of the month for Germany and at the end of the month for Austria. The data for Finland and Latvia exclude recipients of employer-provided sick pay, i.e. the first nine respectively ten days of sick leave.

Source: Administrative data available online (Finland, Germany) or provided by national authorities (Austria, Latvia).

It is still early days to draw clear lessons for the functioning of paid sick leave systems and the extensions taken during the crisis because empirical evidence on take‑up, health outcomes, and the impact on labour markets and poverty prevention are still limited. Simultaneous adaptations and increases in other benefits, such as job retention schemes, limit the specific lessons that can be learned for paid sick leave schemes alone.

One take‑away is that a good way of preparing for future pandemics, or even future COVID‑19 waves, would be to implement mechanisms that, in times of crisis, automatically and temporarily extend paid sick leave entitlements and reduce employer costs.8 Only few OECD countries have reacted to the COVID‑19 pandemic by introducing, or improving, such legislation. Others could consider to follow their lead.

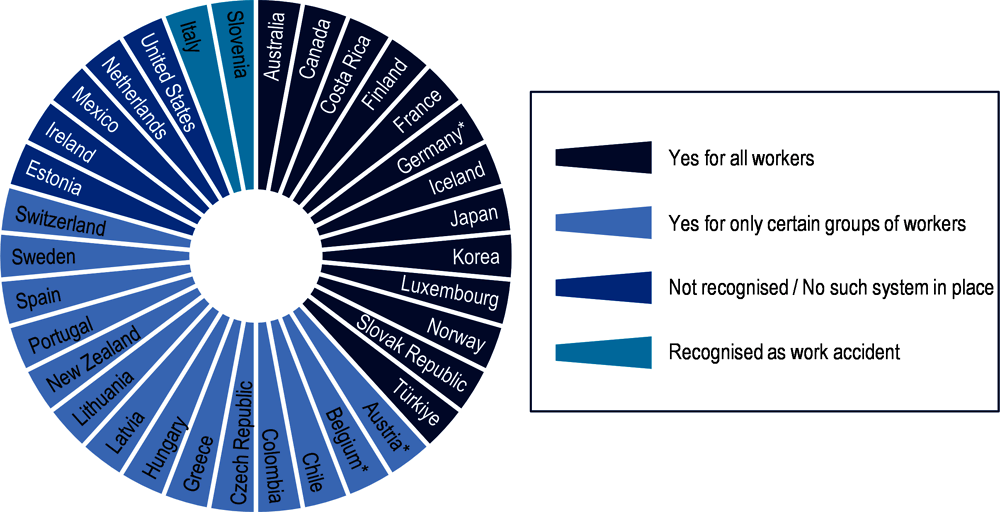

Moving out of the acute phase of the pandemic, the support for the many people with long COVID‑19 needs to become a top priority, especially as their return to work appears to be difficult (HSE, 2021[27]). Many OECD countries are moving ahead by recognising COVID‑19 as a work injury or an occupational disease (ILO, 2020[28]). This may give workers access to longer-term compensation of lost earnings (“workers’ compensation”), better coverage of medical expenses and better return-to-work support.

More than half of all OECD countries now consider COVID‑19 to be an occupational disease, at least for specific groups of workers (Figure 2.8). The main economic sectors considered as risk groups for COVID‑19 include health care, residential care, and social work (Eurostat, 2021[29]), all characterised by female‑dominated workforces. In Austria, the number of sectors covered is larger and includes occupations in public and private welfare (schools, kindergartens and nurseries), medical laboratories and prisons. In Japan, sick workers are entitled to workers’ compensation if they require recuperation care and long-term leave because of “long COVID‑19” symptoms. In Italy and Slovenia, contraction of COVID‑19 at work entitles workers to compensation under the claim of an accident at work. In Germany, infections with COVID‑19 can be recognised as an accident at work for all groups of workers, with rather tight regulations, and as an occupational disease for workers working in health services, welfare services and laboratories. A few other countries make a similar distinction.

Note: “*” may recognise COVID‑19 as an occupational disease or work accident. Countries with missing information are not reported.

Source: Country responses to OECD Questionnaire on Policy Responses to the COVID‑19 Crisis and Eurostat (2021), https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/en/web/products-statistical-reports/-/ks-ft-21-005.

In practice, access to workers’ compensation benefits may be easier, and the number of recognised cases ultimately larger, in countries that recognise COVID‑19 as an occupational disease only for workers in certain economic sectors or occupations.9 In such cases, the requirements for proving infection risks may be, and typically are, lighter, because the risk is high and the infection route often clear. By contrast, in countries that cover all sectors in principle, rules can be much tighter.

Active labour market policies (ALMPs) assist jobseekers and people at risk of losing their job in finding or remaining in quality employment. They also support employers in finding employees with the right skills. ALMPs encompass the provision of labour market services (employment services and administration of benefits) and active labour market measures (training, employment incentives, sheltered and supported employment and rehabilitation, direct job creation and start-up incentives).10 Throughout the COVID‑19 crisis and recovery ALMPs have played a crucial role, and they will continue to be of importance in the face of new labour market needs.

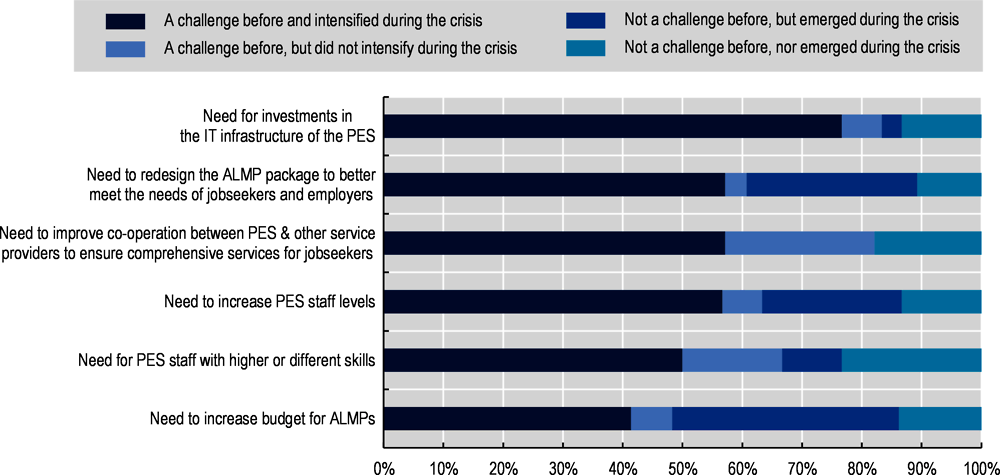

Prior to the onset of the pandemic, the majority of public employment services (PES)11 already faced significant challenges. For many countries, this took the form of ongoing needs to further invest in the IT infrastructure of the PES, shortages of (skilled) staff and challenges related to effective co‑operation with other organisations. Many countries were also struggling with providing appropriate support for jobseekers with multiple or severe employment obstacles (90% of the OECD countries for which data are available) and young jobseekers (83% of countries).

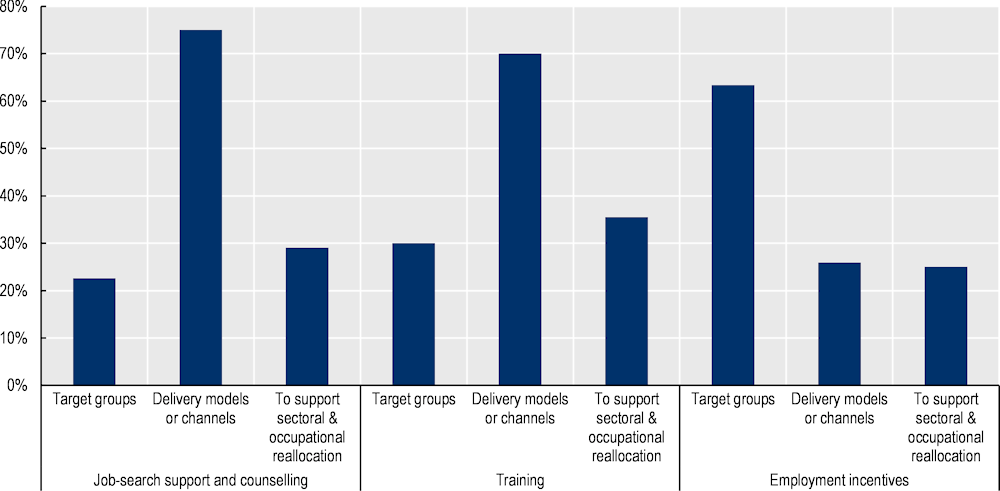

COVID‑19 not only brought new challenges, but also exacerbated many pre‑existing challenges faced by the PES – see Figure 2.9. In particular, for many countries the COVID‑19 crisis contributed to the emergence of, or intensified, the need to redesign the ALMP package to better align it with the labour market situation (86% of countries), to make investments in IT infrastructure (79%), to increase staffing levels (79%) and to further increase the budget for ALMPs (79%). In addition, the pandemic put on hold plans by some PES to change their internal functioning or implement major digital projects which became less of a priority in the actions required to address the consequences of the pandemic (European Commission, 2021[30]).

Note: Statistics based on 30 country responses (AUS, AUT, BEL, CHE, CHL, CRI, CZE, DEU, DNK, ESP, EST, FIN, FRA, GRC, HUN, IRL, ISL, ITA, JPN, KOR, LTU, LUX, LVA, MEX, NZL, POL, PRT, SVK, SVN, SWE).

Source: OECD Questionnaire on Policy Responses to the COVID‑19 Crisis.

The need to redesign the package of ALMPs is reflected also in the enhanced difficulties during the crisis in finding job opportunities for, and providing supports to, jobseekers facing major or multiple obstacles and young jobseekers (noted by 79% and 76% of countries respectively). This often requires resource‑intensive individualised ALMPs in co‑operation with other service providers such as health and social services (OECD, 2021[31]). The COVID‑19 crisis also contributed to challenges in supporting employers, with more than four‑in‑five countries having experienced increased difficulties in filling vacancies in certain frontline occupations.

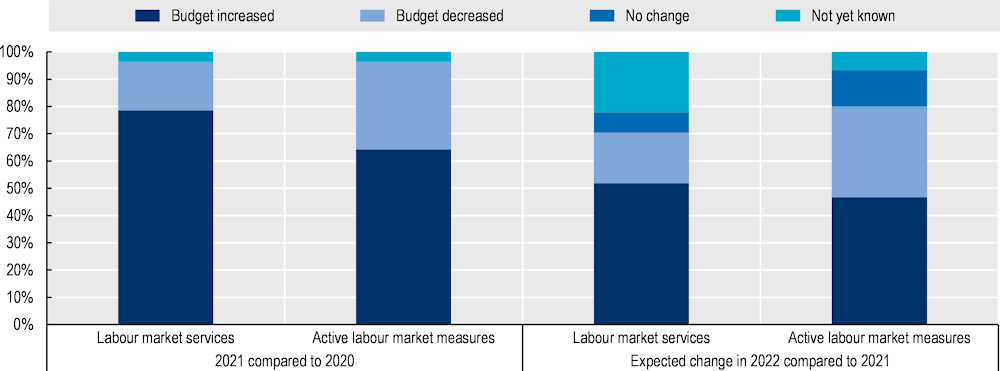

At the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic in 2020, countries responded rapidly by increasing their budgets for PES and other ALMPs (OECD, 2021[32]). Despite the increased needs and budgets, actual spending did not increase in all countries and for all types of ALMPs, as the provision of ALMPs faced significant challenges during the times of stricter confinement and physical-distancing rules. The increase in public spending was generally higher for passive labour market policies (unemployment benefits, job retention schemes). The increases in actual spending on ALMPs and passive labour market policies were in many countries higher than the increase in the number of unemployed, as both types of policies aimed to prevent unemployment and income losses before these could materialise, thus covering groups beyond the (registered) unemployed.

Faced with ongoing high demand for ALMPs in 2021 and having established better ways to provide ALMPs in the context of the challenging health situation, heightened levels of public spending on ALMPs continued in 2021 for many countries (Figure 2.10). Budgets for labour market services increased in almost four‑in‑five countries in 2021 relative to 2020. This effect was somewhat more muted for active labour market measures, for which public expenditure increased in 64% of countries for 2021. Within the basket of active labour market measures, training and employment incentives saw the highest share of countries increasing expenditure for 2021. Indeed, investing in training measures and well-targeted employment incentives can be particularly effective in supporting the labour market during a crisis and the subsequent recovery (Card, Kluve and Weber, 2018[33]; OECD, 2021[4]; 2021[34]).

However, not all countries opted to tread the same path, with approximately one‑in-five countries decreasing expenditure for labour market services in 2021 relative to 2020 (Canada, the Czech Republic, Finland, Luxembourg, Mexico). This trend was sharper for public expenditure on active labour market measures, where one‑in-three countries reduced public expenditure in 2021 relative to 2020. This reduced expenditure in some countries was likely due to a combination of factors, including the significant pressure on public finances since the onset of the pandemic and the fact that the peak in unemployment had been reached during 2020 for many countries.

Looking forward, among countries where budgetary decisions for 2022 were known at the end of 2021, two‑in-three expect to further increase the budget for labour market services in 2022 relative to 2021, and one‑half for active labour market measures. Overall, this means that in 2022 ALMP budgets will be significantly higher than in 2019 before COVID‑19, even though OECD-wide employment recovered its 2019 level already at the end of 2021 – see Chapter 1. These trends highlight a broad recognition within many countries of the ongoing role to be played by ALMPs in promoting labour market outcomes. Countries should also be aware of the risks associated with withdrawing budgets too quickly as, for example, truly committing to enhanced digitalisation will take substantial investments before these generate efficiency and effectiveness gains.

Note: Labour market services includes public (or private, with public financing) provision of employment services and administration of benefits: statistics based on 29 country responses (AUS, AUT, BEL, CAN, CHE, CHL, CRI, CZE, DEU, DNK, ESP, EST, FIN, FRA, GRC, HUN, ISL, ITA, JPN, KOR, LTU, LUX, LVA, MEX, NZL, PRT, SVN, SWE, USA). Active labour market measures includes training, employment incentives, sheltered and supported employment and rehabilitation, direct job creation and start-up incentives: statistics based on 31 country responses (in addition: IRL, TUR).

Source: OECD Questionnaire on Policy Responses to the COVID‑19 Crisis.

The significant increase in resources put in place as a result of the pandemic cannot be assumed to have necessarily enhanced effectiveness and coverage of ALMP provision. Continuous monitoring and evaluation of policy measures will be important to ensure that resources are only allocated to those areas which have a proven track record of providing effective support to jobseekers and employers.

In response to the COVID‑19 crisis, PES across the OECD adapted their strategies and operating models to better deliver their services. In almost three‑in-four countries, the PES have made, or plan to make, changes to the way in which they work with employers. This exceeds by far the extent of reported changes in other areas. For example, Lithuania’s PES plan to establish a separate employer services team to work strategically with employers on national level. Slovenia is working to further develop its existing formal national partnership with employer associations on a regional and local level to find new solutions for tackling labour market bottlenecks. For many countries, such changes go hand-in-hand with efforts to enhance digitalisation of services and processes, including increased online outreach efforts and implementing online job-matching and recruitment services. Australia, for instance, created a new Jobs Hub, which helps to connect jobseekers with employers and provides tools to aid jobseekers in identifying jobs that match their skills profile.

A high share of countries have also adjusted, or plan to adjust, their PES case management strategy, in terms of the frequency or intensity of job search assistance for jobseekers (66% of countries) and in how tasks are allocated among PES staff (57%). In bringing about change in this area, some countries (including France, Iceland, Japan, Lithuania, Mexico, Slovenia) have increased or plan to increase the intensity of supports provided to certain groups of jobseekers, such as individuals at high risk of becoming long-term unemployed, women, young people and migrants. In addition, more than half of countries have adapted job search requirements for jobseekers. In some cases, this took the form of a temporary suspension or relaxation of job search obligations for jobseekers during confinement periods, while more recently countries have been taking steps to strengthen these requirements again.

Across almost all areas of change to PES operating models and strategies, both implemented and planned, changes are associated with greater digitalisation efforts. This includes developments in reaching out to jobseekers and the inactive (e.g. Italy’s development of apps to reach out to young people out of work), improving the profiling of clients (e.g. Luxembourg’s use of artificial intelligence in a new jobseeker profiling method) and enhancing the job-matching process (e.g. Flanders’ development of a Talent API to compare supply and demand of new vacancies with client files and CVs). The United States seeks to reduce administrative burdens across public sector agencies (including employment services) and calls on them to design and deliver services that people of all abilities can navigate, use technology to modernise and simplify processes, and consider ways to reduce the “time tax” in getting people the services they need.