Satoshi Araki

Andrea Bassanini

Andrew Green

Luca Marcolin

Satoshi Araki

Andrea Bassanini

Andrew Green

Luca Marcolin

There is evidence that monopsony power is pervasive and substantial in OECD economies. Monopsony is the situation that arises where firms have the power to set wages unilaterally, leading to inefficiently low levels of employment and wages. This chapter reviews the causes, incidence, consequences and policy responses to labour market monopsony, focusing especially on labour market concentration, which is a key determinant of monopsony because in concentrated markets, few firms offer employment opportunities for workers. Using a harmonised dataset of online job vacancies, the chapter provides the largest cross-country comparison of the incidence of labour market concentration to date. It also presents original estimates of the consequences of labour market concentration on job quality, using employer-employee data. The chapter concludes by reviewing policy responses available to address monopsony and help labour markets function closer to the competitive ideal.

Monopsony describes the situation in which employers possess unilateral wage‑setting power, and use it to set wages and employment below the levels that would prevail in a competitive market, where firms have to pay workers a “market rate” aligned with their productivity. Monopsony does not just imply lower wages for affected workers, but also a misallocation of resources: wages, employment and social welfare are lower when firms have monopsony power, compared to competitive labour markets.

This chapter explains why some firms have wage‑setting power, in particular in the case of labour market concentration where only a few employers compete in a market for workers. It provides novel statistics on the incidence of employment in concentrated labour markets, as well as the implications for job quality. Finally, the chapter discusses policies that directly reduce monopsony, improve the job quality of workers in uncompetitive labour markets and help labour markets function better for all workers.

Employers in monopsonistic labour markets are likely to depress employment and pay lower wages in order to reap higher profits. Labour market frictions that make it difficult to reallocate labour, employers offering unique sets of working conditions that tie workers to their workplace and highly concentrated markets (very few employers) are all reasons why firms may exercise monopsony power.

Key empirical findings include:

The empirical literature suggests that firm monopsony power is pervasive and substantial in OECD economies. One popular approach for measuring monopsony is to estimate the labour supply elasticity a given firm faces, namely the percentage reduction in the number of workers willing to work for the firm if it lowers the offered wage by 10% independently of other firms. Estimates of this elasticity found in the literature are often quite low. In other words, firm-level employment is far less responsive to wage changes than it would be if there were perfect competition. Even in markets where one would expect high competition – such as online labour markets – employer wage‑setting power is often substantial. However, while these estimates suggest the existence and pervasiveness of monopsony power, they do not identify the channels through which it affects the labour market.

This chapter finds that labour market concentration, one of the key determinants of monopsony power, is pervasive in a wide range of OECD countries. Using harmonised data of online job vacancies and the same labour market definitions across countries, this chapter finds that 16% of business-sector workers in 15 OECD countries are in labour markets that are at least moderately concentrated – according to the conservative definition frequently used by antitrust authorities – and 10% are found in highly concentrated markets. These figures can be considered a lower bound to the share of workers in concentrated markets.

Workers are not evenly distributed across concentrated markets. Workers in rural labour markets are more likely to be in concentrated labour markets, for example.

Workers who have been on the front line during the COVID‑19 crisis – those with substantial contact with colleagues or customers and thus with a higher than average risk of infection (see Chapter 1) – are more likely to work in concentrated labour markets. By contrast, workers in occupations amenable to telework tend to be found in much less concentrated markets.

A year into the COVID‑19 pandemic, labour market concentration was 10% higher, on average, in OECD labour markets. The rise was sharp at first, and probably driven by a significant drop in job openings at most firms during the first lockdown, with the remaining vacancies being posted by a few resilient employers. Since then, concentration has begun to fall back towards pre‑pandemic levels, in line with a progressive normalisation of hiring by firms.

Available evidence suggests that monopsonistic labour markets tend to be associated with lower employment, but more research is needed. Studies based on mergers tend to find that employment falls after a merger. The few studies using measures of labour market concentration also find that mergers reduce overall employment in the affected labour market. However, quantitative estimates remain very heterogeneous between studies, and there are unresolved methodological issues in the literature.

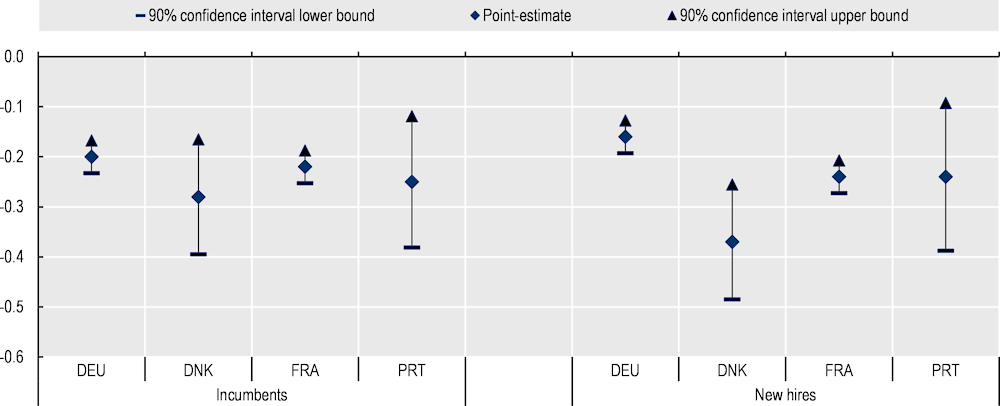

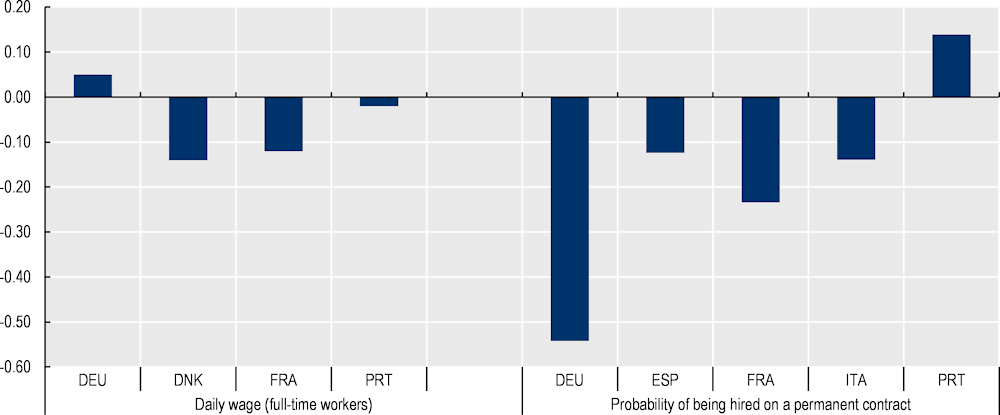

New evidence provided in this chapter relying on harmonised linked employer-employee data for a number of European OECD countries, confirms results from the literature, showing in particular that more concentrated markets result in lower wages. Estimated elasticities of wages to concentration are similar in Denmark, France, Germany and Portugal. A 10% increase in concentration from the average level is estimated to reduce daily wages of full-time workers by 0.2% to 0.3%. These estimates imply that the 10% of workers who are employed in the most concentrated labour markets experience a wage penalty of at least 5% compared with a worker in a labour market with the median level of concentration.

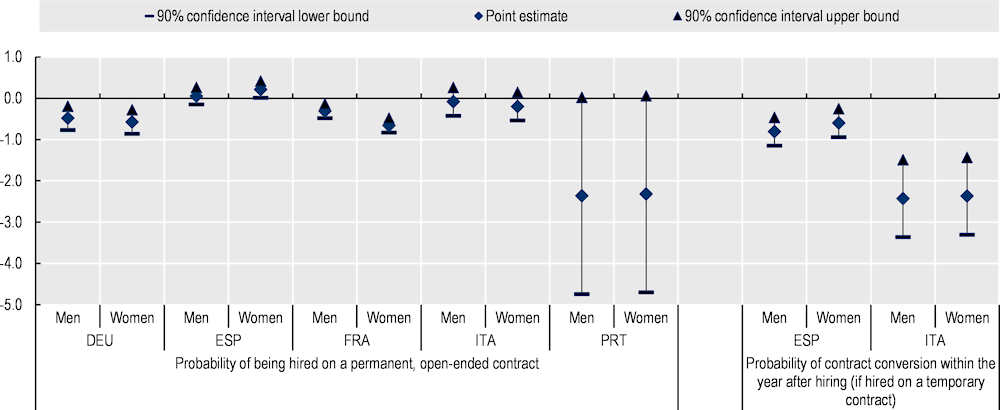

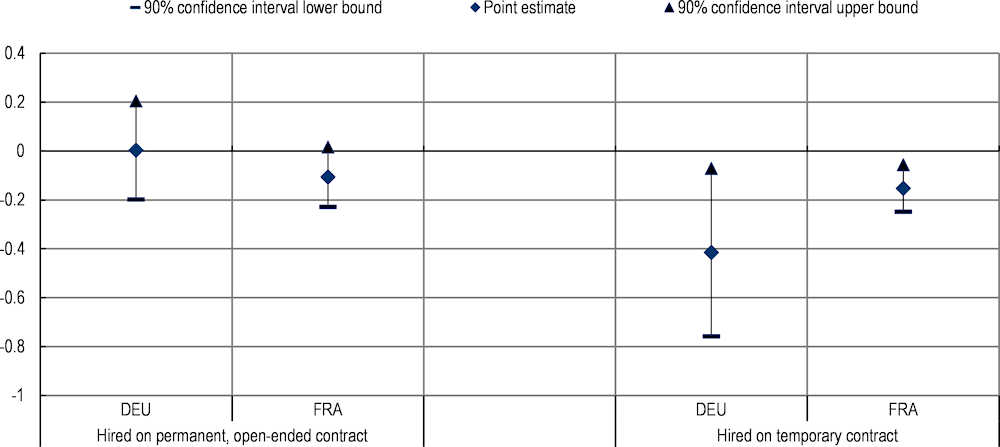

Other aspects of job quality are also affected. Regression analysis suggests that labour market concentration tends to increase the use of flexible contracts. In France, Germany and Portugal increasing concentration is estimated to reduce the probability of being offered an open-ended contract at hiring. The effect of a 10% increase in concentration can be up to 2.3% (for both Portuguese men and women).

Evidence from Spain and Italy suggests that, for those hired on a temporary contract, labour market concentration clearly depresses their chances of accessing a more stable position within the calendar year after hiring. The effect appears particularly large for Italy, where a 10% increase in concentration reduces the conversion rate by 2.5% for both men and women.

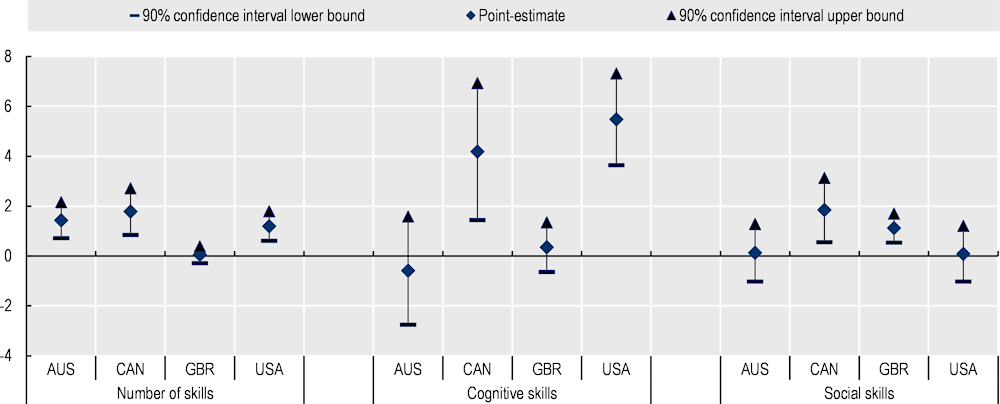

Another dimension affected by monopsony power is skill requirements. Monopsonistic employers tend to curb their labour demand, allowing them to be more selective when hiring. Regression analysis on online job postings finds that labour market concentration often increases skill requirements in posted job vacancies, both in the number of skills that are required, and the frequency with which cognitive and social skills are expected.

Policy can help make labour markets more competitive:

Existing evidence from the United States and Austria suggests that facilitating the enforceability of Non‑Compete Agreements (NCAs) unambiguously reduces job mobility and often depresses wages. NCAs are clauses in contracts that prevent workers from working to a competitor after they separate from their employer. There is evidence that employers frequently use NCAs to limit the outside options of their workers, even when they have no access to the employers’ confidential information or other intangible assets. The chapter discusses several options governments could consider to limit the spread of NCAs.

Other areas of regulatory and enforcement interventions concern occupational licensing, labour market collusion and horizontal mergers. In all these areas, regulators should devote more attention to the consequences of employers’ actions for the competitiveness of the labour market. In many cases, interventions could be undertaken by antitrust authorities, as well as labour authorities.

Interventions to promote collective bargaining could have a strong impact on monopsony power. Under collective bargaining, if workers have sufficient countervailing power, the parties may internalise the position of the firm in the product market so that negotiations may lead to a more efficient labour market outcome, with the greater rents generated in this way shared among the parties. In fact, the negative impact of concentration on wages has been found to be smaller where trade unions are stronger.

Minimum wages can also be used to curb the negative effects of monopsony and concentration. Under monopsony, minimum wages, if set at a reasonable level, lower the marginal cost of hiring at the lower end of the wage distribution. Therefore, minimum wages can raise both employment and wages in monopsonistic labour markets. Consistently, available evidence shows that existing minimum wages have minimal disemployment effects in concentrated markets.

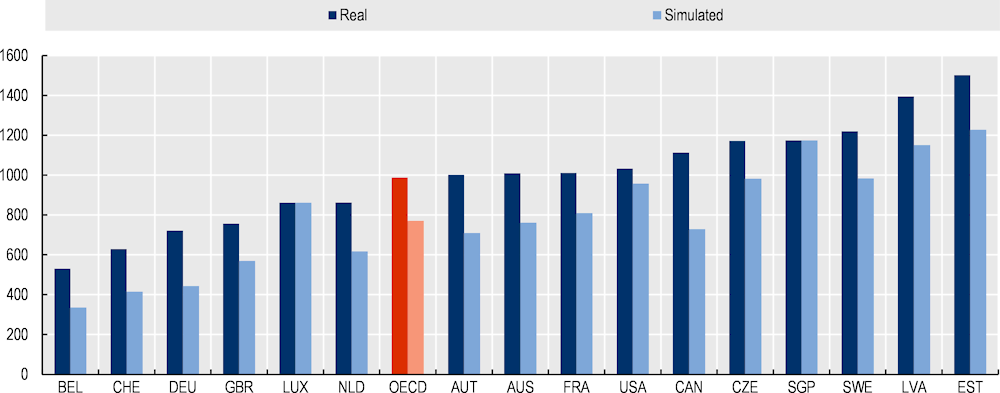

Policies to promote telework may help workers in concentrated markets. For workers in occupations suitable for teleworking, increased telework may allow them to accept positions in a wider geographic radius, increasing the set of employers who can bid for their labour. A simulation performed for this chapter suggests that opening jobs to full-time telework could decrease labour market concentration by about 20%, on average.

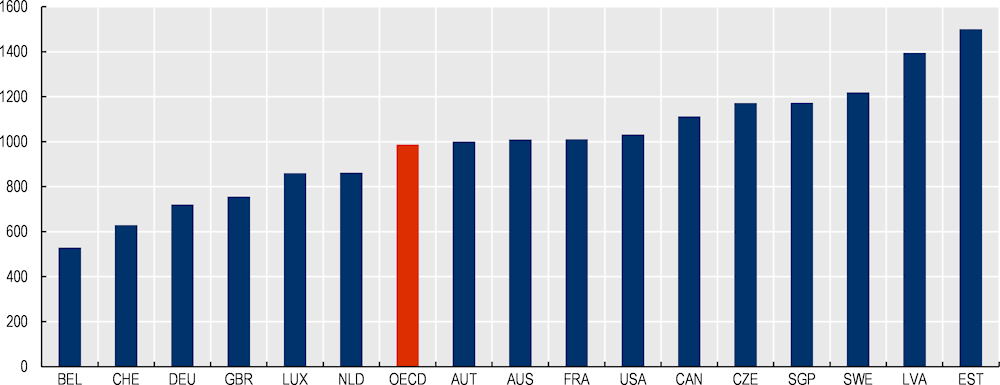

A simulation performed in the chapter suggests that aggregate labour market concentration would decrease by 18% on average across the OECD countries considered if workers could retrain and seek employment in alternative occupations. Reskilling and training policies therefore can play a role in improving labour market conditions when markets are monopsonistic.

If your employer threatens to lower your compensation, would you be able to quit, and quickly find a new job elsewhere with similar working conditions? For many workers, in the absence of policy intervention or some form of collective action, the ability to credibly quit for a higher-paying job is the main bargaining power they have. Moving from one employer to another is one of the strongest sources of wage growth because it allows workers to move up the “job ladder” to higher-paying firms (Topel and Ward, 1992[1]; Haltiwanger, Hyatt and McEntarfer, 2018[2]; Wang, 2021[3]) – see also Chapter 4. The ability to shop around easily for a new employer is a core mechanism for ensuring pay keeps pace with productivity, and it is one of the foundations of competitive labour markets.

When a worker is confronted with a labour market with many similar workers (sellers of labour) but only one or a few employers (buyers of labour), their bargaining power is greatly diminished, and it may be difficult to find a new employer. A classic and extreme example is a coal company that employs miners and also owns the only mine within a reasonable commuting distance. In such “company towns” there is really only one employer, so workers seeking a different employer would need to move to a different town often at considerable expense. The firm knows this, and unless there are some countervailing forces, it leaves workers at a disadvantage when bargaining for wages or working conditions. In labour markets, a worker’s compensation is not solely determined by their skills or productivity, but what they have the power to negotiate.

Monopsony is the situation that arises when competitive markets break down and workers cannot easily find enough suitable employment offers. The term encapsulates the situation of markets where few employers exist – labour market concentration. However, monopsony is more general, and arises even in markets with many employers. For example, a single mother whose employer provides subsidised childcare and flexible working hours may find many potential employers, but few offering the same set of working conditions tailored to her personal situation. Alternatively, a low-wage worker who has multiple jobs to make ends meet may simply not have the time to search for jobs effectively and attend interviews with prospective employers. In both of these situations, workers cannot profit from a market of many competing employers to bid wages up to their level of productivity, and instead must negotiate with a limited set of employers who therefore retain some unilateral wage‑setting power.

In line with the literature, this chapter defines monopsony as the situation that arises when firms retain discretion in setting wages and working conditions as opposed to the case of competitive markets where firms must pay workers the “market rate”, which aligns with their productivity.1 Employers in monopsonistic labour markets may use their bargaining power to inefficiently lower wages and depress employment in order to reap larger rents. This not only affects the distribution of rents between workers and firms, but the economy-wide allocation of resources. Monopsonistic labour markets should lead to lower employment and output than what would prevail if labour markets were perfectly competitive.

Policy, however, can directly address the misallocation of resources wrought by monopsony through direct interventions to realign bargaining power (regulation, antitrust policy, the role of social partners), as well as other, more indirect, policy tools (such as minimum wages). In addition, uncompetitive markets themselves may have important implications for other, only tangentially related, labour market policies such as employer-sponsored training. The resulting misallocation of resources from monopsony also justifies policy interventions regardless of labour market conditions: labour market tightness may result in better salaries and working conditions – although there is little evidence of this in the current recovery (see Chapter 1) – but it is unlikely to restore the outcomes of a competitive labour market.

Although research on monopsony goes back decades, the assumption that labour markets are competitive has persisted in most policy circles. The recent availability of high-quality data covering the near-universe of workers, firms, online job vacancies or mergers is forcing a re‑examination of this assumption. Researchers are now better able to compute the concentration of firms in a well-defined labour market directly. Concentration is a key source of monopsony power because in concentrated markets, workers’ outside options are limited. Concentration indexes are used by antitrust authorities as a rough proxy for market power to identify markets where action may be required – see e.g. US Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission (2010[4]). However, much of the current research on labour market concentration looks at the United States, and focuses on the effect of concentration on employment, wages or earnings while neglecting other job characteristics such as job insecurity, opportunities for promotion and progression, commuting distance and training. The cross-country studies that do exist, furthermore, have light country coverage and often use data which make cross-country comparisons challenging.

This chapter fills the gaps in this evolving literature by providing a cross-country evaluation of labour market concentration with an emphasis on policy. The first question of interest is the proportion of a country’s workers who are employed in concentrated labour markets. Using harmonised data on both online vacancies and matched employee‑employer data, the chapter provides the largest cross-country comparison to date of the share of workers facing concentrated labour markets. In addition to national averages, the chapter shows how certain vulnerable groups such as front-line workers may be disproportionately working in concentrated markets, as well as how market concentration has evolved over the COVID‑19 pandemic. The chapter then analyses the effect of concentrated markets on various aspects of labour market performance including employment, earnings, job security and skill demand.

Finally, the chapter reviews the current literature around policy responses to labour market monopsony and concentration. The discussion touches on policies that have a direct impact on the relative power of workers and employers, as well as on policies that can be mobilised to counteract the negative effects of power imbalances on labour market outcomes.

The chapter begins with the definition and examples of monopsony, before proceeding to considerations of measurement, economic consequences and policy responses. Section 3.1 defines monopsony first broadly as the likelihood of a worker quitting when faced with a reduction in wages – monopsonistic competition (Manning, 2003[5]) – but then more specifically for the case of concentrated labour markets characterised by a limited number of employers for many workers. Section 3.2 then presents cross-country estimates of concentration including a focus on key occupations and demographic groups, and an examination of how concentration has evolved over the COVID‑19 pandemic. Section 3.3 shows the effects of concentrated labour markets on employment, wages, job security and skill demand.2 Section 3.4 then reviews some direct policy responses as well as other policies which may have indirect consequences for monopsony in the labour market. Section 3.5 offers concluding remarks and identifies avenues for further policy research.

In monopsonistic labour markets, employers depress labour demand in order to reduce labour costs and reap higher profits from paying works less than their marginal productivity – see e.g. Boal and Ransom (1997[6]), Manning (2003[5]), Ashenfelter, Farber and Ransom (2010[7]) and Blair and Harrison (2010[8]). In other words, employment and wages are set at a lower level than what would be achieved in competitive markets, where employers must pay workers the market rate which aligns with their productivity. The misallocation induced by unilateral employer power suggests a role for governments to intervene and limit the scope of monopsonistic labour markets (see Section 3.4).

Monopsony encompasses the case of firms that have large discretion in setting wages (and, by extension, employment). Technically, the term characterises markets with one buyer of labour (employers) but many sellers (workers). However, at least as used in labour economics, the term monopsony encompasses a more general definition, where employers have wage‑setting power over workers and labour markets therefore deviate from the competitive ideal. In competitive labour markets, firms take wages as given by the market, and if any firm attempted to offer wages lower than the market-determined price, all of their workers would quit and/or hiring would be rendered impossible. In practice, labour markets exist on a spectrum between purely competitive (firms take wages as given), and completely monopsonistic (firms have complete wage‑setting power). Research on labour market monopsony concerns itself with theorising why firms may exercise unilateral wage‑setting power, and measuring its extent.

There are three broad reasons why firms may have unilateral wage‑setting power in the labour market. First, there may simply be too few firms relative to available workers. In a simple model in which few employers compete in a market with each other, firms employ fewer workers than in the competitive equilibrium and offer a lower wage (Boal and Ransom, 1997[6]). This is analogous to product markets where there are few buyers and many sellers. Labour markets of this type are often concentrated – they have too few employers. The measurement of labour market concentration constitutes one avenue of research on monopsony.

While this model is widely used in industrial organisation and retains salience for empirical work in labour economics, it does not take into account the specific characteristics of the labour market. Employers can have monopsony power even if markets are not concentrated, e.g. because of clauses in labour contracts which limit workers’ ability to look for alternative jobs (such as non-compete agreements, see Section 3.4.1).3 Alternatively, workers may have preferences for specific job attributes provided by the employer (see below).

For these reasons, another strain of thought, referred to as “Dynamic Monopsony” or “Modern Monopsony”, posits that workers must search for suitable employment opportunities. In these models, workers cannot immediately quit an employer and instantaneously find a new one, or instantaneously find a new job if unemployed. These search frictions imply that workers must wait for a suitable job offer, which provides firms with some wage‑setting power (Burdett and Mortensen, 1998[9]; Manning, 2003[5]). In addition to such “natural” search frictions, firms may actively introduce additional frictions in their labour market (e.g. through collusion among employers and non-compete agreements), thereby increasing their monopsony power vis-à-vis their workers (see Section 3.4.1).4

A third explanation derives monopsony power from workers’ preferences for firms besides the offered wage. For example, if employers offer different health insurance plans, or access to childcare, which vary in their generosity, workers may prefer certain firms even if they offer identical wages. Such preferences also extend to amenities such as “company culture”, or employer attributes like commuting distance (Card et al., 2018[10]). With such differentiated employers, workers may find it difficult to quit and find a suitably similar firm. Regardless of why firms offer different amenities, models that rely on workers’ preferences for differentiated firms result in wage‑setting power for firms.5

In all of the explanations for monopsony, firms obtain the ability to decrease wages while retaining most of their workers and their ability to hire. This relationship, the change in available workers for a given change in the wage offered, is called the elasticity of labour supply to a firm. Research on these elasticities represents one classical way to measure firm monopsony power. When this elasticity is low – changes in offered wages result in small changes in hires, quits or employment – this is evidence of some degree of monopsony power.

What is becoming increasingly evident from the literature is that monopsony is far more prevalent in labour markets than previously expected. In the language of labour economics, estimates of the labour supply elasticity facing the firm are small. In the ideal case of perfect competition own-firm labour supply elasticities would be infinite. Normally, single‑digit estimated elasticities, or lower, are considered to be evidence of monopsony power – see e.g. Manning (2003[5]).

In one of the largest reviews of the literature so far, the consensus estimates of the own-firm labour supply elasticity are in the single digits. Sokolova and Sorensen (2021[11]) examine 1 320 recent estimates of labour supply elasticities reported in 53 studies. They report own-firm labour supply elasticities around 3 for women and 4.2 for men on average among the most rigorous estimates. This corresponds to a 22% wage markdown from the worker’s marginal productivity, on average.

Reported own-firm elasticities tend to be lower in Australia, Canada and the United States than in Europe (Sokolova and Sorensen, 2021[11]). An OECD analysis of linked employer-employee data of 10 OECD countries6 finds the weighted average of the country-level estimates to be 2 (OECD, 2021[12]), which again, implies pervasive monopsony in the labour markets of these countries. Finally, Webber (2016[13]) finds significant variation in the firm’s wage‑setting power across the wage distribution, with the elasticity in the lowest quartile being only 0.22 (against an average estimate of 1.08).

Firms may hold unilateral wage‑setting power even when search frictions are considered to be a priori minimal, and the labour market in question appears to be perfectly competitive. Dube et al. (2020[14]) conclude that the elasticity of labour supply facing the requester on Amazon Mechanical Turk (“MTurk”) – a prominent online job market matching task requesters and workers – amounts to 0.14, suggesting substantial market power of requesters (firms) despite the apparent absence of search frictions – see also OECD (2019[15]), which dealt extensively with issues on monopsony for the own-account self-employed. Similarly, Caldwell and Oehlsen (2018[16]) run a field experiment in which they randomly assign higher wage rates to Uber drivers in the United States for one week. They estimate labour supply elasticities below 1 for both those who can work for a rival platform and those who cannot. Overall, there is growing evidence that monopsony power is pervasive, even in what one would assume to be the most competitive labour markets.

Monopsony power may affect women more than men, on average. The estimates of labour supply elasticities generally find a lower elasticity for women, and the wage markdown to a worker’s marginal productivity is around 6 percentage points higher for women than men (Sokolova and Sorensen, 2021[11]). There are plausible reasons for that. For example, there is evidence that women have different and more marked preferences for certain job amenities, especially in the case of mothers with young children, which reduces their bargaining power (Mas and Pallais, 2017[17]; Wiswall and Zafar, 2017[18]). In addition, women tend to search for jobs closer to their home, and they are ready to accept a significant wage penalty for a closer job, which exposes them to greater monopsony power (Le Barbanchon, Rathelot and Roulet, 2020[19]; Jacob et al., 2019[20]). Lastly, women’s caregiving responsibilities are also linked to their occupation choices. Women may choose occupations with less working hours and more flexibility (Goldin, 2014[21]), which may lead them into more concentrated labour markets.

More generally, one could expect that historically disadvantaged groups (such as youth, migrants and ethnic/racial minorities) are more exposed to monopsony power than insiders. Monopsony models predict that employment should be below what would prevail in a competitive market. Firms may therefore have their choice of workers and they may have discretion on whom they choose to hire for the jobs they make available. This could mean that they may prefer to employ workers with more labour market experience which would disadvantage youth (see Section 3.3.2). They can also choose to pay workers with comparable productivity but worse prospects for employer-to‑employer job mobility less than others, as shown for non-white workers in Brazil by Gerard et al. (2021[22]). In addition, in models of dynamic monopsony where even a small fraction of firms may discriminate against certain groups, workers in these groups are penalised with larger wage markdowns even in non-discriminating firms (Lang and Lehmann, 2012[23]; Cahuc, Carcillo and Zylberberg, 2014[24]). In most models of discrimination (assuming competitive or monopsonistic markets), firm entry should drive discriminating firms out of the market. However, concentrated labour markets likely have some barriers to firm entry, and one should expect they therefore contain a lower share of disadvantaged groups.

As mentioned in the previous sub-section, labour market concentration – i.e. the situation wherein labour markets are dominated by a few firms – is expected to result in monopsony power for these firms. When few firms dominate a given labour market, they may be able to affect wages through their own labour demand. It also means that workers are less likely to find similar suitable employers, or are more likely to meet the same firms while searching for suitable jobs (Manning, 2020[25]). Lastly, fewer employers are more likely to implicitly (or explicitly) co‑ordinate their wage setting – see Section 3.4.1. To the extent that the variety of suitable job offers depends on the number and relative size of the firms in a market, the elasticity of own-firm labour supply can be seen as a decreasing function of labour market concentration (Jarosch, Nimczik and Sorkin, 2019[26]).

In short, labour market concentration is likely one of the major sources of monopsony, and it therefore makes for an imperfect, easy-to-measure, empirical proxy for employer wage‑setting power.7 Namely, there should be a positive correlation between labour market concentration and employer wage‑setting power across markets (Jarosch, Nimczik and Sorkin, 2019[26]; Azar, Marinescu and Steinbaum, 2019[27]; Boal and Ransom, 1997[6]).

For this reason, among others, the use of concentration as an empirical measure of monopsony has exploded. In just the last few years, studies using labour market concentration to measure monopsony have appeared, using data from the United States (Azar et al., 2020[28]; Benmelech, Bergman and Kim, 2022[29]; Yeh, Hershbein and Macaluso, forthcoming[30]; Qiu and Sojourner, 2019[31]; Rinz, 2022[32]), the United Kingdom (Abel, Tenreyro and Thwaites, 2018[33]), France (Marinescu, Ouss and Pape, 2021[34]), Austria (Jarosch, Nimczik and Sorkin, 2019[26]), Portugal (Martins, 2018[35]), Norway (Dodini et al., 2020[36]), and more recently, cross-country studies (OECD, 2021[12]; Bassanini et al., 2022[37]) for a limited number of countries.8

One open question is whether the results of these studies reflect differences in data or methodology, or if they reflect real cross-country differences in the competitiveness of labour markets. This chapter builds on this previous work by presenting the largest cross-country coverage of labour market concentration in OECD countries with the greatest uniformity in the definition of a labour market.

Using data on the universe of online job vacancies, this section reports estimates of the share of workers in concentrated labour markets for 15 OECD countries, as well as for Singapore.9 This is the largest cross-country study of labour market concentration to date, and it is the only cross-country study to use a large harmonised dataset and labour market definition for cross-country comparability. In addition to country-level averages, the section shows how concentration impacts certain segments of the labour market including specific occupations, gender and youth, among others. The section concludes by analysing concentration dynamics over the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Whether a labour market is concentrated depends on how one defines the local labour market where a potential worker can reasonably expect to quickly find a suitable job. The literature typically defines labour markets with the combination of detailed economic classes (industry or occupation), and geography. In theory, the local labour market is an area that captures all employers to which a potential worker could reasonably commute. Some studies of labour market concentration use commuting zones or functional urban areas which are often designed empirically to capture observed home‑to-work flows (Foote, Kutzbach and Vilhuber, 2021[38]). Due to data limitations, this chapter uses Territorial Level 3 (TL3) regions, which are a higher level of geographic aggregation than commuting zones (see Box 3.1). Designed by the OECD, TL3 regions cover every OECD country, are generally stable over time, and are designed to be roughly comparable across OECD countries (OECD, 2016[39]).

In addition to TL3 regions, this chapter defines the relevant labour market using occupations instead of industries. Industries are designed based on the economic activity carried out in an establishment. Occupations are classified based on the skills and qualifications required of the worker, and are therefore portable across industries in most cases. Occupations are thus more suitable to define workers’ job search patterns, and to measure labour market concentration as a consequence. Using occupations is also consistent with evidence presented in certain famous cases of unlawful no-poaching agreements in the United States in the mid‑2000s (Koh, 2013[40]), which show that companies can produce different products while competing for the same workers. Hovenkamp and Marinescu (2019[41]) provide further examples. For Continental European countries, this chapter uses 4‑digit ISCO‑08, and 6‑digit SOC‑2010 for Anglophone countries.10

The standard measure of concentration in the labour market is the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) of either vacancies, new hires or employment in a local labour market. This is defined as the sum of the squared percentage shares of each firm in the market. The index ranges from 0, no market concentration, to 10 000, the case of a single firm controlling the entire market.11 Markets are considered concentrated according to the threshold for action used by antitrust authorities for product market concentration, which are typically very conservative (Nocke and Whinston, 2022[42]; Affeldt et al., 2021[43]). According to US antitrust authorities, high concentration markets display an HHI of 2 500 and above, and moderately concentrated markets an HHI of 1 500 to 2 500 – see e.g. US Department of Justice and Federal Trade Commission (2010[4]).12 These can be considered to yield a lower bound to the share of workers in concentrated markets.

This chapter uses data on online job postings from Emsi Burning Glass (EBG) to measure labour market concentration. EBG collects online job postings in many OECD countries, which contain information on the posting’s occupation, geography and firm (including industry), in addition to other characteristics such as skills and educational requirements. The data have been shown to have an almost full coverage of vacancies, and is increasingly representative of overall employment in the United States (Hershbein and Kahn, 2018[44]; Azar et al., 2020[28]). This chapter then validated the data coverage on the remaining OECD data for which EBG data are available and Singapore. Fifteen OECD countries and Singapore were assessed to have suitable coverage for inclusion in the chapter.13 With the exception of the analysis of concentration dynamics during the pandemic, the analysis in this section uses data from 2019.

After calculating HHI at the occupation by TL3 level, the cells were aggregated to the ISCO‑3 level using job posting weights and then they were weighted to employment using the occupation distribution in the business sector (omitting industries where public employment is sizeable)14 in each country available from labour force surveys (see Annex 3.B for a full description of data validation, construction and analysis). The final country-level estimates are adjusted to account for heterogeneity in the average population size of TL3 regions across countries (see Box 3.1).

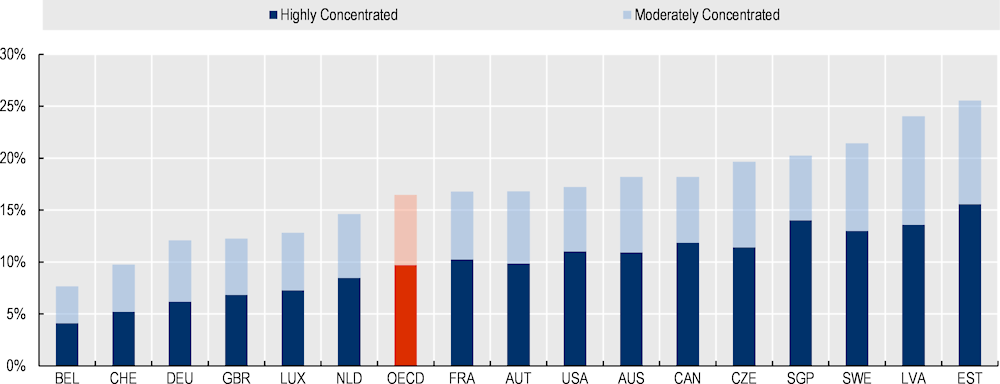

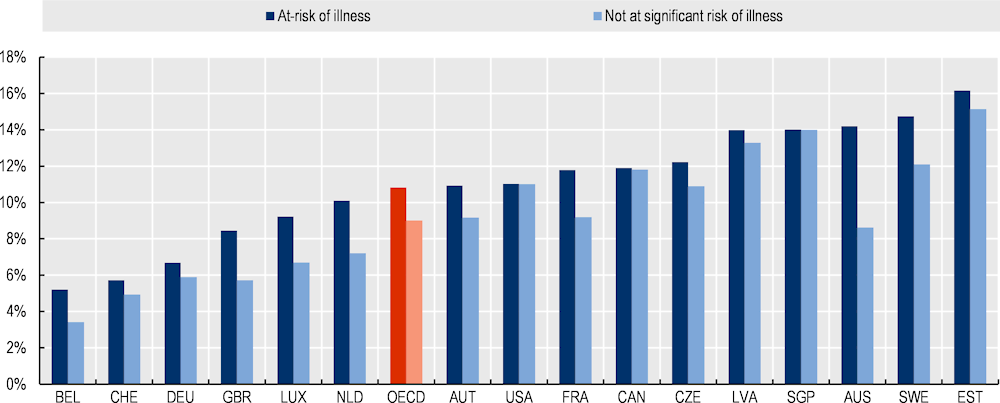

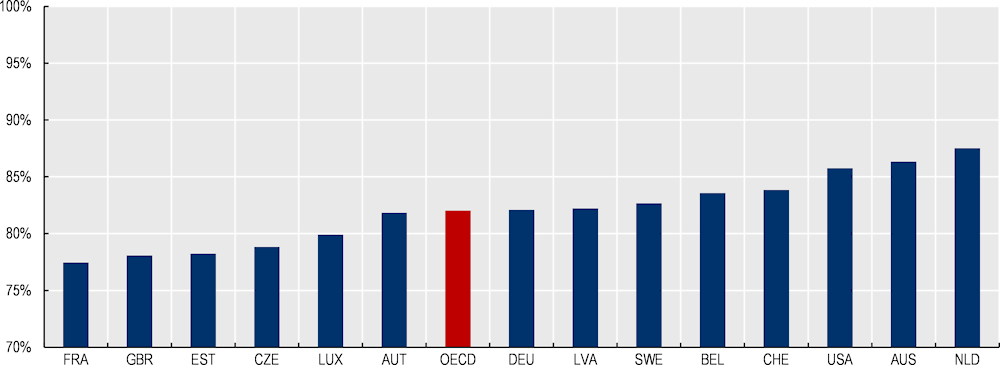

This chapter finds a sizeable share of workers in OECD countries work in markets that are moderately to highly concentrated. Figure 3.1 shows the share of workers in moderately concentrated labour markets (light blue) and the subset of those who are in highly concentrated labour markets (dark blue), as derived from estimates of HHI at the national level (Annex Figure 3.A.1). Just over 16% of workers find themselves in labour markets that are at least moderately concentrated, on average across OECD countries in the sample. Of those, more than half, or about 10% of the total, work in highly concentrated labour markets. The highest shares of workers in markets that are at least moderately concentrated are found in Estonia and Latvia with shares above 24%, while the smallest shares are found in Belgium and Switzerland with shares under 10%. The results in this section confirm that cross-country differences in labour market concentration are not simply due to differences in data or labour market definitions.15

Over a longer time series, concentration tends to be stable across OECD countries. The Emsi Burning Glass job posting data used in this chapter do not allow for the comparison of HHI over a long time period. However, using administrative data on new hires, OECD (2021[45]) finds that HHI is relatively stable from 2003 to 2017 in an average of 7 OECD countries.16 There is likely variation across countries in this trend, however. For example, Rinz (2022[32]) finds a modest decrease in local labour market concentration in the United States from around 2000 to 2009, and then a modest increase during the financial crisis.

These results are relevant because, all else equal, workers in these markets are likely paid wages below what their productivity would suggest in a competitive market. A similar argument can be made for other measures of job quality (see Section 3.3.2). While this applies to all workers whether they find themselves in concentrated markets or not, one should be especially careful for workers in markets which are moderately or highly concentrated.

In addition, one needs to place these estimates in their proper context. First, the thresholds used in this analysis to determine whether a market is concentrated are high (see the discussion of HHI above), and these estimates can therefore be viewed as a lower bound of workers in concentrated markets. Second, these estimates are of labour market concentration, and they therefore only represent one source of monopsony power. Even in markets that do not meet the thresholds for concentration, workers may still be subject to other sources of monopsony power (see Section 3.1). Finally, this chapter does not analyse the causes of the reported cross-country differences in labour market concentration. Countries differ, for example, in the composition of the labour market in terms of occupations, sectors, and commuting patterns which can directly affect concentration (see below). A structured analysis of the determinants of labour market concentration is left to future analyses.

Notes: OECD average is an unweighted average of countries in the sample excluding Singapore. Moderately concentrated markets are markets with a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) between 1 500 and 2 500. Highly concentrated markets have an HHI greater than 2 500. Labour markets are defined by job vacancies in 6‑digit SOC by TL3 regions for Anglophone countries and 4‑digit ISCO by TL3 regions for remaining countries. Shares are adjusted to a uniform population size of 200 000 of TL3 regions following Azar et al., (2020[28]). Employment shares are obtained by weighting HHIs using 2019 employment data from labour force surveys at the ISCO 3‑digit level (omitting ISIC sections O, Public administration and defence; P, Education; Q, Human health and social work activities; and T, Activities of households) and job postings at the same level of disaggregation at which HHIs are defined. Singapore’s weights include all ISIC sections.

Source: OECD analysis of Emsi Burning Glass data, European Union Labour Force Survey (European Union countries, Switzerland and the United Kingdom), Current Population Survey (United States), Canadian Labor Force Survey (Canada), Australian Labour Force Survey (Australia), The Ministry of Manpower (Singapore).

The demarcation of local labour markets to identify monopsony power is challenging, especially in a cross-country context, and a consensus on methodology is yet to be reached (Azar et al., 2020[28]; Manning, 2020[25]; Naidu, Posner and Weyl, 2018[46]; Hovenkamp and Marinescu, 2019[41]). Too narrow a market restricts the set of workers’ outside options and inflates firms’ wage‑setting power, while the opposite holds true for too large a market. The definition of a local labour market involves a labour market statistics interacted with the combination of geographical units and economic units (occupations or industries).

Frequently used geographic units are commuting zones – e.g. Azar et al. (2020[28]), Marinescu, Ouss and Pape (2021[34]), Benmelech et al. (2022[29]), Berger et al. (2019[47]), Rinz (2022[32]) – or administrative units – e.g. Modestino, Shoag and Ballance (2016[48]). While administrative units may not fully capture travel-to-work flows in an area, definitions of commuting zones are not necessarily comparable across countries. EU-OECD functional urban areas (FUA) are defined using the same methodology for all countries as urban centres and catchment areas thereof (Dijkstra, Poelman and Veneri, 2019[49]). As such, FUAs leave out rural areas. Ascheri et al. (2021[50]) use FUAs, but their analysis is therefore limited to urban areas.

In light of these considerations and the availability of information in the EBG dataset, HHIs in this chapter are calculated based on TL3 regions, unless otherwise specified. TL3s correspond to sub-national administrative units1 that are roughly comparable across countries (OECD, 2021[51]), even though their size and number can differ across countries. In order to improve their comparability further, however, an adjustment factor is obtained by regressing aggregate concentration statistics on the logarithm of the country-specific population average of TL3 regions. This adjustment factor is then applied to each statistic in order to obtain figures for an average regional population of 200 000 people, which roughly corresponds to commuting zones in the United States, and allows therefore an easy comparison with figures obtained by Azar et al. (2020[28]) – see also Annex 3.B.

As far as the economic unit is concerned, Berger et al. (2019[47]), Benmelech et al. (2022[29]), Rinz (2022[32]) and OECD (2021[45]) calculate HHIs by industry, whereas Azar et al. (2020[28]), Martins (2018[35]), Marinescu, Ouss and Pape (2021[34]), and Azar, Marinescu and Steinbaum (2022[52]) do so by occupation.2 This chapter calculates HHIs by occupation3 for two reasons. First, empirical evidence shows occupation switches imply a wage penalty even controlling for employer and industry switches – see Kambourov and Manovskii (2009[53]), Gathmann and Schonberg (2010[54]) – they cause losses in occupation-specific human capital. Second, the use of industries is likely to conflate product market and labour market concentrations, even though one can exist without the other – see Manning (2020[25]), Hovenkamp and Marinescu (2019[41]), Redding and Rossi-Hansberg (2017[55]).4 In fact, there is evidence that firms operating in different industries can still collude to control the labour market of the same occupation (Hovenkamp and Marinescu, 2019[41]; Gibson, 2021[56]).

Two additional elements need to be chosen to compute the HHI. The variable over which firm shares are computed (usually employment, hires or vacancies), and the relevant time period. Due to data availability, the analysis in this chapter is based on quarterly vacancies, except in Section 3.3.2. An HHI based on employment seems to be a reasonable measure of concentration both in a classical, static model of monopsony and in a stationary search and matching model with granular search, where concentration affects workers’ outside options (Boal and Ransom, 1997[6]; Jarosch, Nimczik and Sorkin, 2019[26]). However, in a non-stationary environment, downsizing firms may have a positive share of employment without hiring so that they do not effectively contribute to the number of outside options in the labour market. In this case, a measure based on job vacancies or new hires better captures the fact that labour market concentration is a key determinant of monopsony power (Marinescu, Ouss and Pape, 2021[34]; Bassanini, Batut and Caroli, 2021[57]; Azar, Marinescu and Steinbaum, 2022[52]).

Finally, this chapter computes HHIs on a quarterly basis. Many papers compute flows over annual intervals due to data availability. However, Azar et al. (2020[28]) compute HHI quarterly, arguing that that an annual interval is manifestly too long to capture outside options. This chapter follows on that lead and computes HHIs on a quarterly basis.

1. For Australia, Canada and the United States, TL3 corresponds to groups of sub-national administrative units. For Luxembourg, there is only one TL3 region assigned to the whole country. One TL3 region is assigned to the whole of Singapore for the current analysis.

2. Other dimensions are sometimes explored in some studies – see e.g. Azar et al. (2020[28]) Dodini et al. (2020[36]).

3. Four-digit ISCO‑2008 is used for European countries (excluding the United Kingdom) and 6‑digit US SOC‑2010 is used for Australia, Canada, Singapore, the United Kingdom and the United States.

4. For example, evidence exists that product market concentration has a negative impact on productivity. Neglecting to take this into account when estimating the impact of labour market concentration on wages may underestimate the effect of concentration on wages.

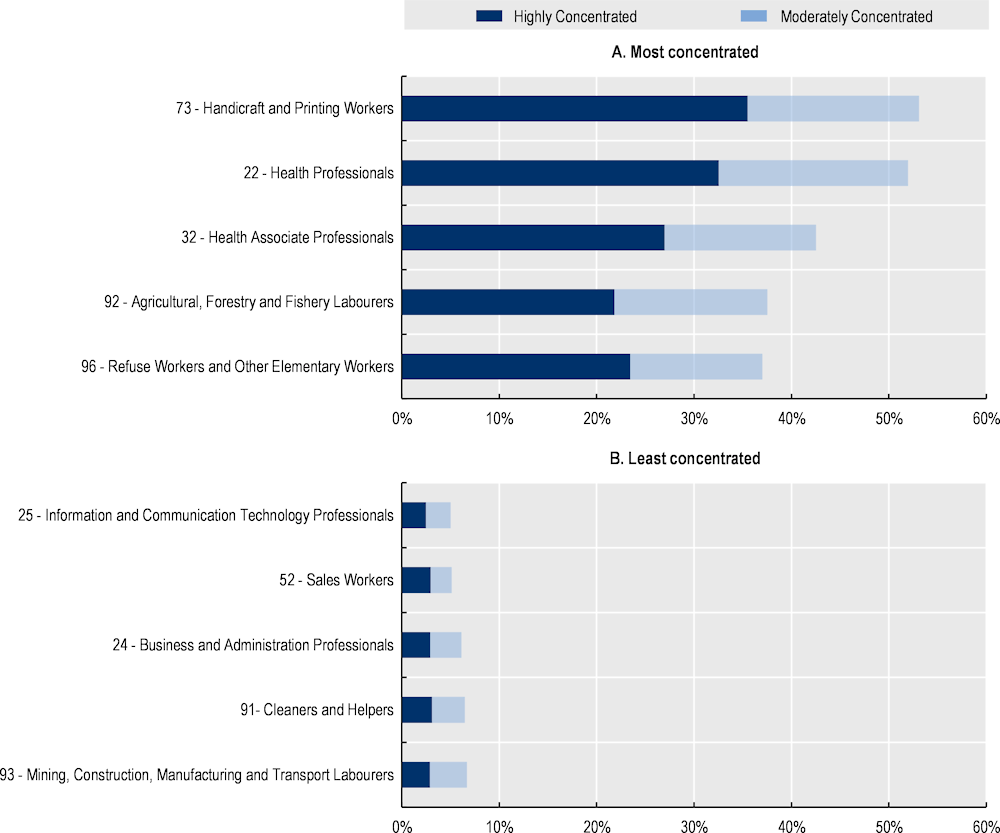

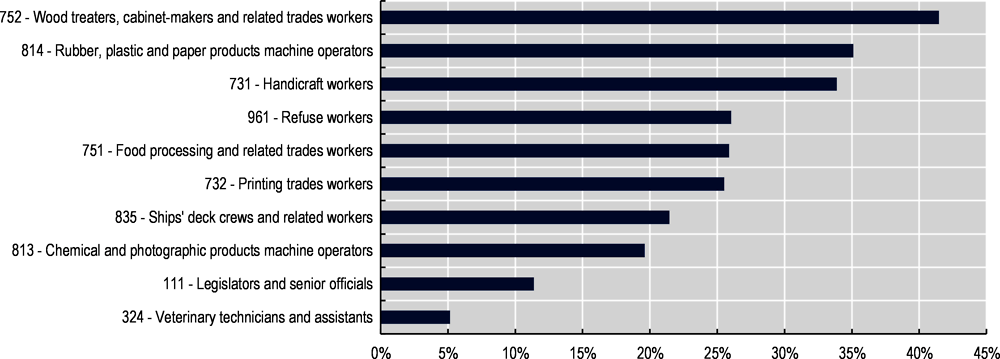

A few blue‑collar occupations and health-related labour markets tend to be more concentrated. Figure 3.2 depicts the average share in concentrated markets by 2‑digit ISCO occupation.17 The occupations which are the most concentrated, on average, are handicraft and printing workers, and health professionals, where over 50% of business-sector employment in these occupations is found in concentrated markets.18 In addition to those two occupations, the top five most concentrated occupations include other blue‑collar occupations – such as agricultural, forestry and fishing labourers and refuse workers.

The least concentrated occupations are information and communication technology professionals, sales workers and business administration professionals where less than 7% of workers in these occupations are found in concentrated markets. The least concentrated occupations are not confined to high-skill, high-wage professionals. General cleaners and helpers and sales workers are also present in the least concentrated occupations, likely because workers in these occupations are typically employed in numerous small establishments and shops. In short, occupations in the least concentrated markets appear to be employable in a wide variety of industries, which would grant them more employment options.

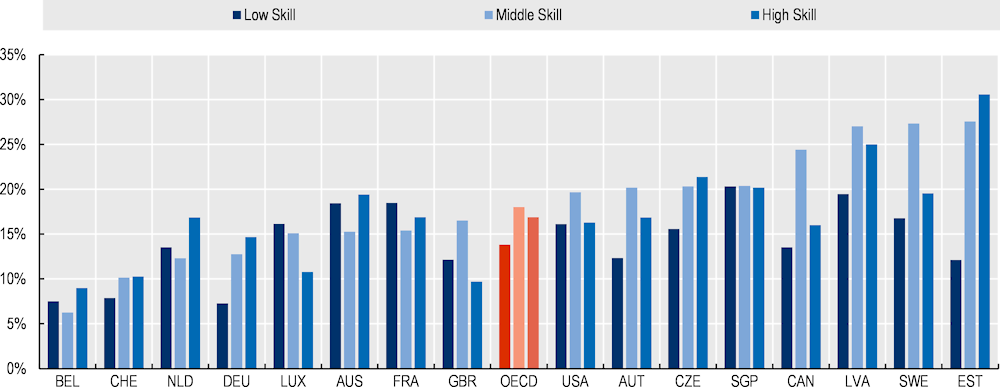

The analysis in this chapter also finds that workers in middle‑skill occupations are the most likely to be in concentrated labour markets. Low-skill workers face the lowest concentration and high-skill workers the next highest after middle‑skill workers. This pattern is not particularly robust across countries, however (Annex Figure 3.A.2). The declining employment share of middle‑skill jobs, and the rise in job polarisation and deindustrialisation is a well-documented fact across many OECD countries (OECD, 2017[58]; OECD, 2020[59]). As the employment shares of middle‑skill jobs shrink, the remaining workers may face a smaller and smaller pool of potential employers who continue to use the production technologies to employ them.

In addition to occupation, the other key dimension of a labour market is geography. Larger labour markets, in particular cities, have long been hypothesised (with increasing empirical evidence) to allow more efficient matches between firms and workers (Petrongolo and Pissarides, 2006[60]; Andersson, Burgess and Lane, 2007[61]; Bleakley and Lin, 2012[62]; Dauth et al., 2018[63]). A worker searching for job is more likely to find a suitable employer when there are many potential employers, and vice versa. Labour markets are more efficient when they are thick. The same logic applies to market concentration as measured by HHI: workers should find it easier to quit and find a new employer when there are more potential employers.

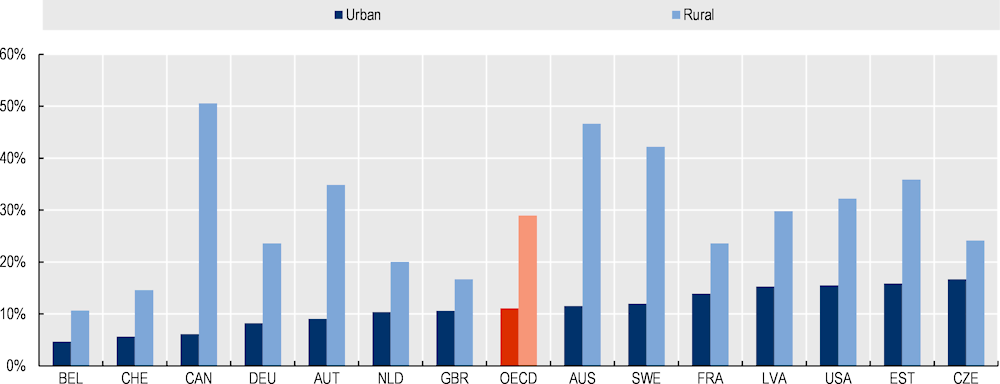

Urban areas are less concentrated than rural geographies in all countries for which data are available. Figure 3.3 uses the OECD definition for metropolitan regions, which includes TL3 regions that have more than 50% of their population living in a functional urban area of over 250 000 people (Fadic et al., 2019[64]). On average across OECD countries in the sample, rural regions (29%) have about two and half times more people working in moderately concentrated markets than urbanised regions (11%). The largest differences are in Canada and Australia, two countries with large urban centres but also geographically large, but sparsely populated provinces including remote areas.

Notes: Average of Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Estonia, France, Germany, Latvia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. ISCO 2‑digit occupations “61” and “95” omitted due to irregular cross-country coverage. Moderately concentrated markets are markets with a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) between 1 500 and 2 500. Highly concentrated markets have an HHI greater than 2 500. Labour markets are defined by job vacancies in 6‑digit SOC by TL3 regions for Anglophone countries and 4‑digit ISCO by TL3 regions for remaining countries. Employment shares are obtained by weighting HHIs using 2019 employment data from labour force surveys at the ISCO 3‑digit level (omitting ISIC sections O, Public administration and defence; P, Education; Q, Human health and social work activities; and T, Activities of households) and job postings at the same level of disaggregation at which HHIs are defined.

Source: OECD analysis of Emsi Burning Glass data, European Union Labour Force Survey (European Union countries, Switzerland and the United Kingdom) and Current Population Survey (United States).

The finding confirms results from the literature that rural labour markets are more concentrated. Azar et al. (2020[28]) and Bassanini, Batut and Caroli (2021[57]) find a decrease in HHI as the size of commuting zones increases in the United States and France, respectively. Using the same urban-rural definition as this chapter (but different data and definition of labour market), OECD (2021[45]) similarly finds a large urban-rural difference in the share of workers in concentrated labour markets.

Notes: The OECD average is an unweighted average of all countries in the sample. Luxembourg and Singapore have no rural regions and are omitted. Urban regions are TL3 regions that have more than 50% of their population living in a functional urban area of over 250 000 people (Fadic et al., 2019[64]). Moderately to highly concentrated markets are markets with a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) of 1 500 or more. Labour markets are defined by job vacancies in 6‑digit SOC by TL3 regions for Anglophone countries and 4‑digit ISCO by TL3 regions for remaining countries. Shares are adjusted to a uniform population size of 200 000 of TL3 regions following Azar et al., (2020[28]). Employment shares are obtained by weighting HHIs using 2019 employment data from labour force surveys at the ISCO 3‑digit level (omitting ISIC sections O, Public administration and defence; P, Education; Q, Human health and social work activities; and T, Activities of households) and job postings at the same level of disaggregation at which HHIs are defined.

Source: OECD analysis of Emsi Burning Glass data, European Union Labour Force Survey (European Union countries, Switzerland and the United Kingdom), Current Population Survey (United States), Canadian Labor Force Survey (Canada), Australian Labour Force Survey (Australia).

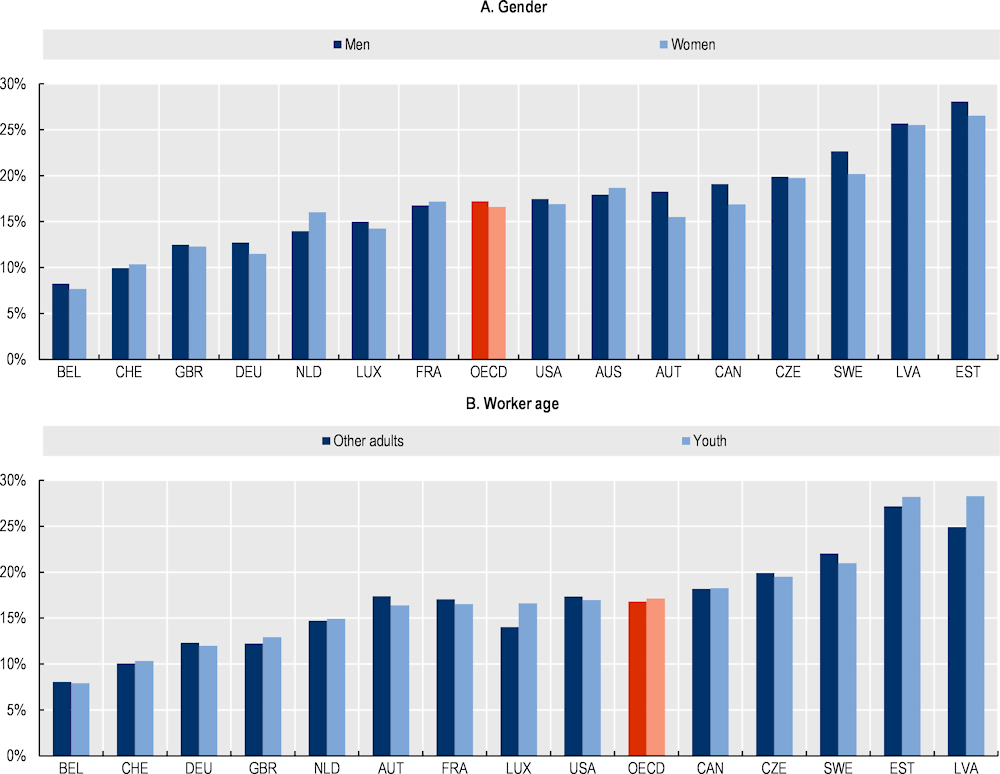

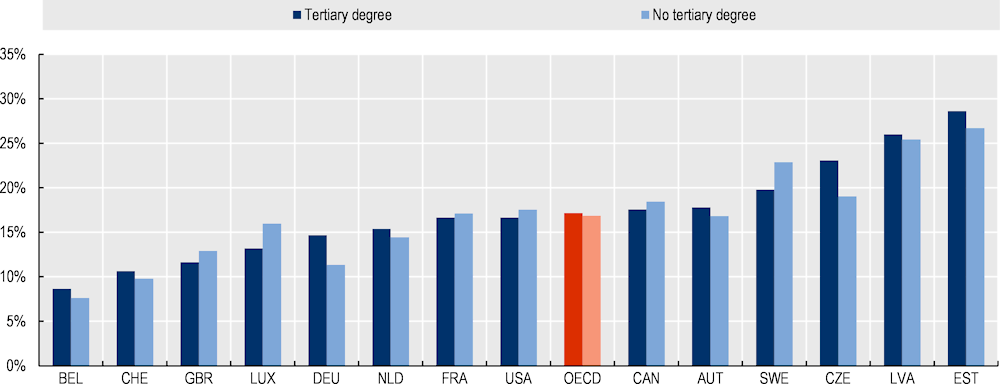

This chapter finds little evidence that women are more likely than men to work in concentrated labour markets. Figure 3.4 (Panel A) shows the share of men and women in moderately to highly concentrated labour markets. On average, 16.6% of women are in labour markets that are at least moderately concentrated, compared to 17.2% of men. Estonia, Latvia and Sweden have the highest shares of women in markets that are at least moderately concentrated, each with shares over 20%. However, in those countries, the share of men in concentrated markets is also high and even exceeding the share of women.

Just as with women, there is little difference in the share of youth in moderately to highly concentrated labour markets compared to other adults. The share of youth and other adults in labour markets that are at least moderately concentrated is around 17% for both, on average (Figure 3.4, Panel B). The highest shares of youth in concentrated labour markets are also in Latvia, Estonia and Sweden.

Notes: OECD average is unweighted average across countries in sample. Youth employment is defined as ages 15‑29, and other adults age 30 and above. Moderately to highly concentrated markets are markets with a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) of 1 500 or more. Labour markets are defined by job vacancies in 6‑digit SOC by TL3 regions for Anglophone countries and 4‑digit ISCO by TL3 regions for remaining countries. Shares are adjusted to a uniform population size of 200 000 of TL3 regions following Azar et al., (2020[28]). Employment shares are obtained by weighting HHIs using 2019 employment data from labour force surveys at the ISCO 3‑digit level (omitting ISIC sections O, Public administration and defence; P, Education; Q, Human health and social work activities; and T, Activities of households) and job postings at the same level of disaggregation at which HHIs are defined.

Source: OECD analysis of Emsi Burning Glass data, European Union Labour Force Survey (European Union countries, Switzerland and the United Kingdom), Current Population Survey (United States), Canadian Labor Force Survey (Canada), Australian Labour Force Survey (Australia).

While the share of workers in concentrated markets does not differ appreciably by gender or age (or level of education – see Annex Figure 3.A.3), concentration is only one measure of monopsony power. As discussed in Section 3.1, there are other aspects of monopsony apart from concentration that may differentially affect vulnerable groups. Furthermore, concentration may still impact some labour market outcomes unevenly across groups of workers, as shown in Section 3.3.2.

The onset of the COVID‑19 crisis saw workers split into three groups: those who were able to work from home (telework), those who found themselves unemployed or on reduced working hours, and those who continued to work in their physical workplace and in proximity of other people during the pandemic, or front-line workers – see Chapter 1. The gradual abatement of lockdowns and the recovery of the labour market have greatly diminished the ranks of the unemployed and those on short-time work (OECD, 2021[65]). However, more than two years after the onset of the pandemic, the dichotomy between those who must work in person, and workers who may work from home, is still relevant – see Chapter 1.

Labour market concentration may degrade occupational safety if investing in a safe work environment is costly for employers. Employers in concentrated markets may not need to offer a safe work environment to attract and retain good workers. If front-line workers are in concentrated markets, therefore, they could face a heightened risk of infection. Many OECD governments have instituted various protective measures for workers who are required to work, and therefore stand a chance of infection (OECD, 2020[66]) – see also Chapter 2. In countries or regions where such precautions are not mandated, or where workers nonetheless find them inadequate, often one’s only recourse is to quit, and find a job with an employer with better safety measures. Moreover, the ease with which a worker can credibly quit can by itself spur greater safety measures. Whether front-line workers face monopsonistic labour markets is, all things equal, an important aspect of their occupations’ safety and job quality.

Figure 3.5 depicts the share of workers in highly concentrated labour markets by whether their occupation is required to work in person, and whether, because of close contacts with colleagues or customers, they have a high risk of infection with COVID‑19 on the job compared to those who do not (Basso et al., 2022[67]). On average, about 11% of these workers at significant risk of COVID‑19 infection are found in highly concentrated labour markets compared to a little over 9% of those who are not. The largest gaps are found in Australia, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom. In contrast, there is little difference in the shares in highly concentrated markets in the United States and Singapore. Women, the low-educated and workers on temporary contracts among other more economically vulnerable groups are over-represented among at-risk workers (Basso et al., 2022[67]; DOL, 2022[68]).

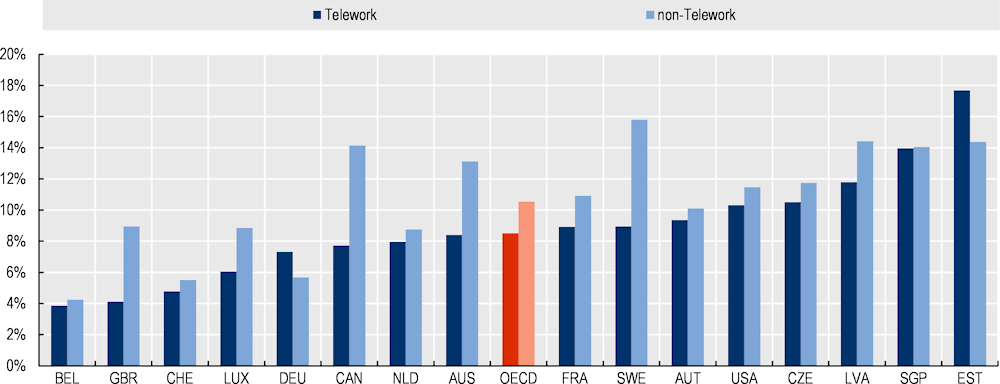

The other defining feature of labour markets during the pandemic were workers who had the option of working from home. Workers who are able to telework are those in occupations where one can work from home without physically interacting with co-workers or customers, based on the tasks that are typically performed on their job according to the US Occupational Information Network database (Dingel and Neiman, 2020[69]; Basso et al., 2022[67]).

Notes: The OECD average is an unweighted average of countries in the sample excluding Singapore. ISCO 3‑digit level Occupations are defined as “unsafe” or “at risk of infection” following Basso et al. (2022[67]). ISCO group 951 is omitted due to poor suitability of conversion from O*NET to ISCO. Highly concentrated markets are markets with a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) of 2 500 or more. Labour markets are defined by job vacancies in 6‑digit SOC by TL3 regions for Anglophone countries and 4‑digit ISCO by TL3 regions for remaining countries. Shares are adjusted to a uniform population size of 200 000 of TL3 regions following Azar et al., (2020[28]). Employment shares are obtained by weighting HHIs using 2019 employment data from labour force surveys at the ISCO 3‑digit level (omitting ISIC sections O, Public administration and defence; P, Education; Q, Human health and social work activities; and T, Activities of households) and job postings at the same level of disaggregation at which HHIs are defined. Singapore’s weights include all ISIC sections.

Source: OECD analysis of Emsi Burning Glass data, European Union Labour Force Survey (European Union countries, Switzerland and the United Kingdom), Current Population Survey (United States), Canadian Labor Force Survey (Canada), Australian Labour Force Survey (Australia), The Ministry of Manpower (Singapore).

Compounding the a priori occupational health disparity with front-line workers, workers who are able to telework are found in less concentrated labour markets. On average, 9% of workers in occupations amenable to telework are in highly concentrated markets on the eve of the COVID‑19 crisis, compared to 11% of those workers who cannot telework (Figure 3.6).

In addition to protecting workers from the virus, the shift to telework during the pandemic may have improved the labour market prospects of these workers. Workers who can telework may search in a wider labour market than simply their local living area. This has the potential to further lower local employers’ monopsony power, and increase bargaining power for workers who can telework (Section 3.4.2).

Notes: The OECD average is an unweighted average of countries in the sample excluding Singapore. Whether an occupation is amenable to telework is defined as “safe” occupations in Basso et al. (2022[67]) at the ISCO 3‑digit level. ISCO group 951 is omitted due to poor suitability of conversion from O*NET to ISCO. Highly concentrated markets are markets with a Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) of 2 500 or more. Labour markets are defined by job vacancies in 6‑digit SOC by TL3 regions for Anglophone countries and 4‑digit ISCO by TL3 regions for remaining countries. Shares are adjusted to a uniform population size of 200 000 of TL3 regions following Azar et al., (2020[28]). Employment shares are obtained by weighting HHIs using 2019 employment data from labour force surveys at the ISCO 3‑digit level (omitting ISIC sections O, Public administration and defence; P, Education; Q, Human health and social work activities; and T, Activities of households) and job postings at the same level of disaggregation at which HHIs are defined. Singapore’s weights include all ISIC sections.

Source: OECD analysis of Emsi Burning Glass data, European Union Labour Force Survey (European Union countries, Switzerland and the United Kingdom), Current Population Survey (United States), Canadian Labor Force Survey (Canada), Australian Labour Force Survey (Australia), The Ministry of Manpower (Singapore).

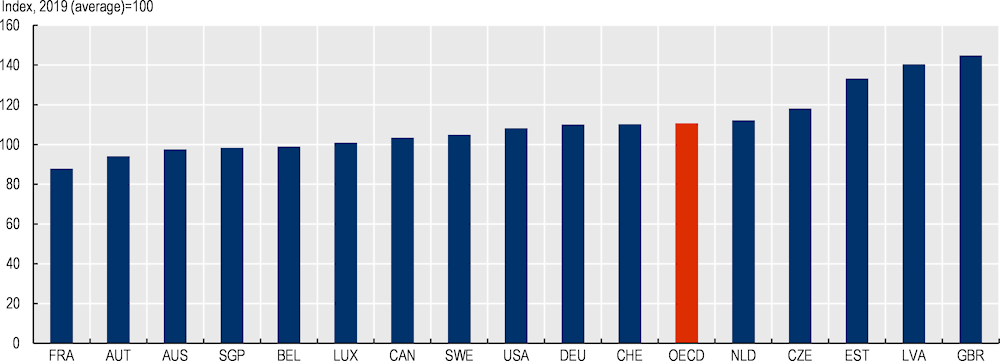

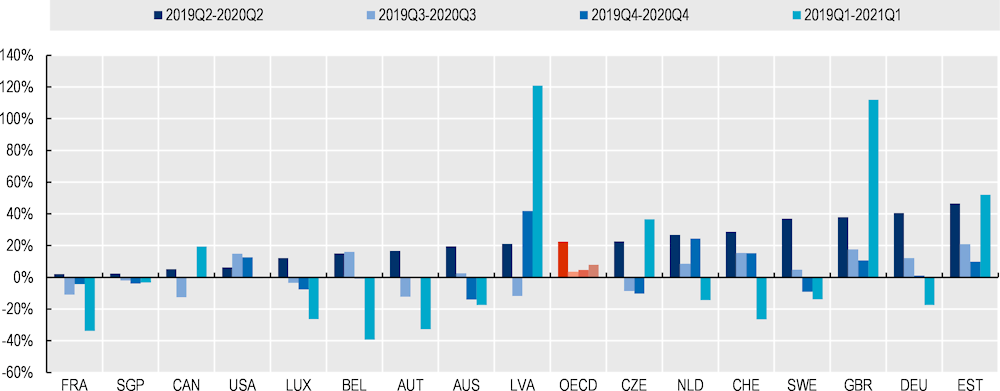

One year into the pandemic, labour market concentration increased. Figure 3.7 shows the change in concentration from 2019 to the average of 2020Q2‑2021Q1.19 Concentration increased by 10% over this time period on average across the OECD countries in the sample, with the United Kingdom, Latvia and Estonia recording the largest growth. In France, Austria, Australia and Belgium, the HHI in the year following the onset of the pandemic was on average below its pre‑crisis level.

Notes: Average of the four quarters of 2019=100 for each country. The beginning of 2021 is an average of 2020Q2‑2021Q1. OECD average is an unweighted average of countries in the sample excluding Singapore. Labour markets are defined by job vacancies in 6‑digit SOC by TL3 regions for Anglophone countries, and 4‑digit ISCO by TL3 regions for the remaining countries. HHI estimates are adjusted to a uniform population size of 200 000 for TL3 regions following Azar et al., (2020[28]). Employment shares are obtained by weighting HHIs using 2019 employment data from labour force surveys at the ISCO 3‑digit level x quarter level (omitting ISIC sections O, Public administration and defence; P, Education; Q, Human health and social work activities; and T, Activities of households) and job postings at the same level of disaggregation at which HHIs are defined. Singapore’s weights include all ISIC sections.

Source: OECD analysis of Emsi Burning Glass data, European Union Labour Force Survey (European Union countries, Switzerland and the United Kingdom), Current Population Survey (United States), Canadian Labor Force Survey (Canada), Australian Labour Force Survey (Australia), The Ministry of Manpower (Singapore).

These average values of concentration one year into the pandemic mask dynamics at the quarterly level. The average HHI grew by over 20% year over year in the second quarter of 2020 (Annex Figure 3.A.4). By the third and the fourth quarter of 2020, HHIs continued to grow, on average, but many countries were experiencing year-over-year declines in their aggregate HHI. By the first quarter of 2021, HHIs had decreased sharply in most countries.20 This suggests that the run-up in concentration at the beginning of the pandemic is starting to abate, and the HHI is converging back toward pre‑pandemic levels.

These patterns likely reflect the limited number of firms posting job vacancies during the acute stages of the pandemic, and the progressive normalisation of hiring in more recent periods. For example, some firms not hit by mandatory foreclosures, kept posting job openings even during the peak of the pandemic, causing a temporary increase in labour market concentration. The dynamics could also reflect an initial stark increase in concentration in certain sectors that represented a larger share of employment in 2019,21 e.g. retail. However, as a large share of workers who would have otherwise sought new job opportunities refrained from doing so because of the pandemic (OECD, 2021[65]), it is not clear that the described movements in labour market concentration translated into actual changes in the wage‑setting power of employers.

The analysis in the previous section finds that labour market concentration is pervasive across OECD countries. However, if labour market concentration leads to monopsony power, one should expect concentration to be associated with changes in employment and wages. This section presents evidence of the effect of concentration on job quantity (employment) and quality (wages). The section begins by reviewing the literature on changes in employment in more concentrated markets, as well as how concentration affects wages. In addition to the literature, this section provides new cross-country empirical estimates of the effect of concentration on earnings, job security and job stability using matched employer-employee data. The estimates also disentangle the effects of concentration on different groups including youth and women. The section concludes by showing how labour market concentration affects the skill composition of labour demand.

Monopsony in the markets for inputs (including labour) can have a negative impact on prices (wages and benefits) and quantities (overall employment). In principle, one would expect to find a clear relationship between measures of monopsony or labour market concentration and employment (see Section 3.1). In practice, however, few studies have documented this relationship due to the difficulty of identifying the effect of labour market concentration independently from other confounding factors while simultaneously solving potential reverse causality issues.

Most of the studies in the literature focus on plant takeovers and mergers. These studies typically find a negative effect of mergers or takeovers on employment at merged firms or acquired plants. A number of early studies have looked at takeovers and found negative effects on employment – for example Lichtenberg and Siegel (1990[70]). Takeovers, however, may not result in greater concentration and market power if they are simply the result of a change in ownership with the acquiring entity operating in other, unrelated markets. More recent studies have focused directly on horizontal mergers, which are more likely to result in increased concentration, with similar results – that is, negative effects of mergers on employment levels of merged firms, see Conyon et al. (2001[71]), for the United Kingdom, Lehto and Böckerman (2008[72]) for Finland, Siegel and Simons (2010[73]) for Sweden, Arnold (2021[74]) for the United States, and the cross-country study of Gugler and Yurtoglu (2004[75]), covering European countries and the United States.22

The limit of merger studies is that they usually cannot disentangle changes in product market competition and, often, efficiency gains from mergers from changes in labour market competition. Policy responses are obviously different when the effect on employment derives from efficiency gains instead of inefficient demand restraints. In one of the very few studies trying to isolate directly the economy-wide effect of labour market concentration on employment, Marinescu, Ouss and Pape (2021[34]) examine its impact on new hires in France, controlling for both productivity and product market concentration. Relying on a standard leave‑one‑out instrumental variable strategy for identification (see Box 3.2 below), they find a very large negative effect of concentration on new hires: taking their estimates at face value, increasing the concentration index at the sample mean by 10% would imply a reduction in the number of new hires in a given local labour market by as large as 3%.23 However, such large effects could suggest a problem of misspecification, related for example to the fact that the number of new hires is indirectly an input into the measure of concentration.24 For this reason, these results should be taken with some caution.

Overall, these results suggest that labour market concentration tends to have a negative impact on employment, although more research is needed to establish the magnitude of this effect. However, job quantity is only one aspect of labour market performance and job quality is equally important. The next section analyses the possible effects of concentration on job quality.

There is a large empirical literature that has tried to estimate the effect of employers’ market power on job quality, although most available studies focus only on the impact on wages and earnings. The literature on the effects of mergers on wages in the merging firms has yielded mixed results – see e.g. Lichtenberg and Siegel (1990[70]), Currie, Farsi and Macleod (2005[76]) and Siegel and Simons (2010[73]). More recent studies have shown that the impact of mergers on wages in a labour market tend to be larger, the greater the impact of the merger on labour market concentration – see e.g. Prager and Schmitt (2021[77]) and Arnold (2021[74]). Recent studies have also looked at the impact of reforms leading to enhanced firm entry, divestitures or greater outside options, thereby unambiguously increasing competition, and have typically found positive effects of these reforms on wages – see e.g. Hensvik (2012[78]), Hafner (2021[79]), Thoresson (2021[80]) and the literature on non-compete agreements discussed in Section 3.4.1 below.

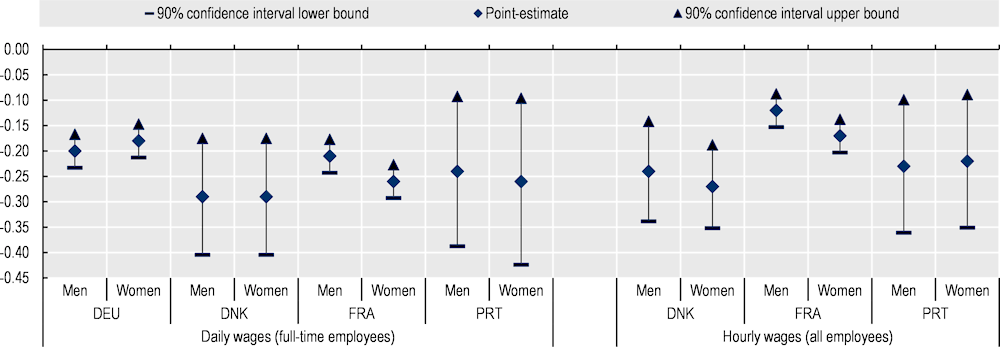

A large recent literature has estimated directly the impact of local labour market concentration on wages in the United States.25 There is also a growing body of recent evidence covering other OECD countries.26 Most of these studies use instrumental variable techniques to deal with potential endogeneity issues (see Box 3.2). The estimated elasticity of wages to concentration typically ranges between ‑0.01 and -0.05. That is, when concentration doubles the wage falls by between 1% and 5%, with larger estimates being found only in a few of the US studies.27 However, the heterogeneity of the measures of concentration and the differences in the specifications used make it difficult to compare point estimates across countries.28

In order to present comparable cross-country estimates, this section relies on Bassanini et al. (2022[37]), who analyse the impact of labour market concentration on wages and job security using harmonised linked employer-employee data for a number of European OECD countries (see Box 3.2 for a detailed discussion of the specification).29

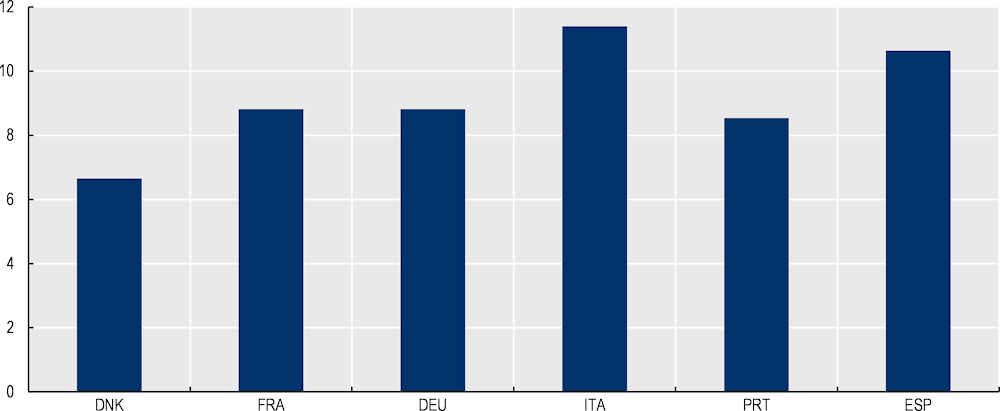

In the four countries for which comparable wage data are available (Denmark, France, Germany and Portugal) the estimated elasticity of wages to labour market concentration varies between ‑0.02 (in Germany) and ‑0.03 (in Denmark) in the case of daily wages for full-time workers (Figure 3.8).30 In other words, at the sample average, increasing labour market concentration by 10% lowers the daily wage by 0.2% to 0.3%.31 This may seem low at first glance, but these results must be interpreted considering that concentration distributions are quite dispersed. In all these four countries, the ratio of the 9th decile of the distribution of HHIs to the median HHI is between 6.7 (in Denmark) and 8.8 (in Germany and France, see Annex Figure 3.A.5). Taken at face value, these estimates therefore imply that, all other things equal, the 10% of workers who are employed in the most concentrated labour markets experience a wage penalty of at least 5% with respect to the median worker. And a few of them, those in markets with concentration well above the 9th decile, suffer from a much greater wage penalty.32

Overall estimated elasticities for different countries remain close to one another. This is remarkable, given the significant differences across the labour markets of these countries – see e.g. OECD (2018[81]). These estimates also appear close to most of the other estimates in the literature, including for countries not included in our sample.33 These two observations, taken together, cautiously suggest that the pattern presented in Figure 3.8 is likely to be more general, and rigorously estimated average wage elasticities are likely to belong to this range in other OECD countries not shown in the chart.

Bassanini et al. (2022[37]) estimate the effect of labour market concentration on wages and job security on samples of linked employer-employee data on the following groups: all workers, full-time workers and new hires. They use the following specification:

where stands for the dependent variable, is a vector of individual and plant-level controls, are fixed effects (with parentheses indicating fixed effects that are not included when the equation is estimated only on the sample of new hires), indexes the worker, the plant, the firm-by-municipality couple,1 the local labour market, the industry and is the year. stands for the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index calculated using the share of each employer in new hires in the local labour market defined by 4‑digit occupation and cross-country comparable functional geographical areas, so that , where is the occupation and is the geographical area.2 The dependent variables include: the logarithm of daily and hourly wages; and dummy variables for having started an open-ended contract at hiring, or having the contract converted into an open-ended one within one year. Due to data limitations, wage equations are estimated only for Denmark, France, Germany and Portugal, while job security equations are estimated for France, Germany, Italy and Spain. In each country, household workers, self-employed, and those working in agriculture and outside the business sector are excluded from the sample.

Ordinary least squares (OLS) cannot consistently estimate the above equation if there is a time‑varying factor that is correlated with both the local HHI and the dependent variables and is not proxied for by existing control variables. For example, positive or negative shocks to local labour supply are likely to affect the wage offers that workers are ready to accept and the number of firms that find it attractive to operate in the local labour market, thereby biasing OLS estimates of the above equation. To solve this problem, many papers3 resort to a leave‑one‑out instrument à la Hausman, which is popular in the trade and industrial organisation literatures.4 In practice, in local labour market at time is instrumented with the average of in all other functional areas for the same occupation and time period – where is the number of firms with positive number of hires in a given year. The same strategy is followed as regards estimates presented in this chapter.

1. The firm-by-municipality fixed effect plays a key role as it allows controlling for labour productivity and product market competition at both the national and local level. The only other study using the same fine‑grained control for productivity and product market competition is Bassanini, Batut and Caroli (2021[57]). Qiu and Sojourner (2019[31]), Marinescu, Ouss and Pape (2021[34]) and Benmelech, Bergman and Kim (2022[29]) include labour productivity, as measured by accounting data, as a control variable without, however, addressing its endogeneity.

2. In the main specification functional geographical areas are composed of OECD functional urban areas (OECD, 2012[82]) and remaining large portions of NUTS3 regions, the latter being added to ensure a mixture of urban and rural areas. Results are however robust to using either functional urban areas or NUTS3 regions only.

3. Azar, Marinescu and Steinbaum (2022[52]), Rinz (2022[32]), Martins (2018[35]), Qiu and Sojourner (2019[31]), Marinescu, Ouss and Pape (2021[34]), Bassanini, Batut and Caroli (2021[57]), OECD (2021[12]) and Popp (2021[83])

4. See e.g. Hausman, Leonard and Zona (1994[84]), Nevo (2001[85]), and Autor, Dorn and Hanson (2013[86]).

Source: Bassanini et al. (2022[37]), “Labour Market Concentration, Wages and Job Security in Europe”, https://docs.iza.org/dp15231.pdf.

Notes: The chart shows point-estimates and confidence intervals of wage elasticities to changes in the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) of the local labour market, defined as couples of 4‑digit occupations and functional areas. The estimates are obtained from a linear regression including individual fixed effects, firm-municipality-year fixed effects, industry and plant fixed effects (where different from firmXmunicipality), annual dummies for workers‘ age, being employed in the previous year, being a new hire and working part-time. The logarithm of HHI is instrumented with the average of the log inverse number of firms in other functional areas for the same occupation. Standard errors are clustered at labour-market year level.

Source: Bassanini et al. (2022[37]), “Labour Market Concentration, Wages and Job Security in Europe”, https://docs.iza.org/dp15231.pdf.

The similarity of the estimated wage elasticities across countries, and their close alignment with the literature, suggest that it is possible to use the literature to infer how these elasticities might have changed over time. The estimates in this chapter were obtained on a limited number of years which does not allow studying trends in the wage elasticity over time. Given the close conformity of these estimates, one can use the wider literature as a guide as to how these elasticities may have evolved over time. For example, using a different concentration measure, OECD (2021[12]) find that this elasticity has become on average more negative in the last two decades. In other words, even though labour market concentration has not increased – see Section 3.2.3, its impact has become stronger over time. One possible explanation might be the concomitant reduction of collective bargaining and the weakening of trade unions (OECD, 2019[15]), which may be increasingly less able to act as a countervailing power – see Section 3.4.1.

In the four countries for which the analysis is possible, there is no systematic gender difference in wage elasticities to labour market concentration. This may appear surprising in view of the literature on separation elasticities that has tended to find smaller elasticities for women than for men (Manning, 2003[5]; Hirsch, Schank and Schnabel, 2010[87]; Webber, 2016[13]; Vick, 2017[88]). The estimates in Figure 3.8, however, should not be interpreted as implying that women are exposed to the same degree of monopsony power as men. As discussed in Section 3.1, women tend to search for jobs closer to their home and are ready to accept a significant wage penalty for a closer job. As a result, the same level of concentration implies fewer acceptable alternative jobs for women, and therefore lower wages. But increasing concentration may still have a similar percentage effect on the rarefication of available alternatives for both men and women, consistent with the gender pattern shown in Figure 3.8.