Turkey has achieved progress over the last decade by increasing the share of population connected to sewerage and to wastewater treatment infrastructure. It has also invested significantly in river basin planning. This integrated approach to planning needs to be leveraged to help Turkey achieve its ambitious goals for urban wastewater management in the short to medium term. The chapter describes these achievements and barriers to achieving the urban wastewater management goals, and suggests opportunities for improvement.

OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Turkey 2019

Chapter 5. Urban wastewater management

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

5.1. State of play and trends

5.1.1. Urban wastewater in the context of water management

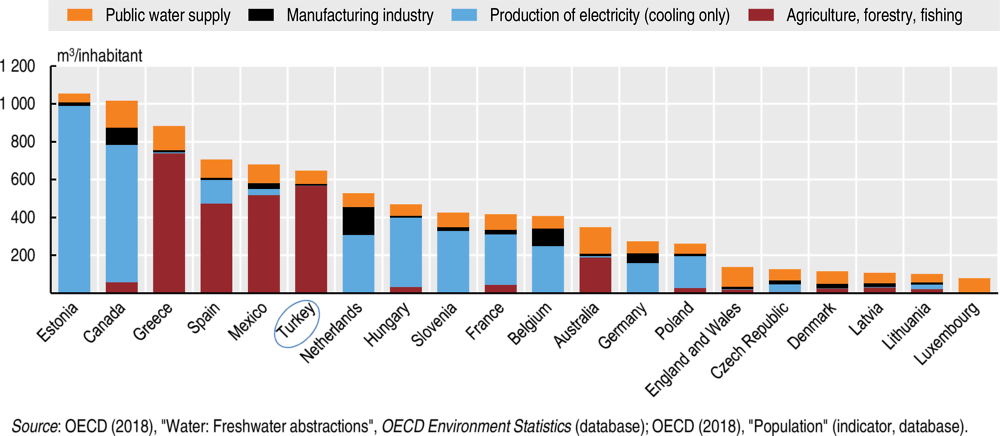

Based on the annual volume of water available per capita, Turkey is not a water-rich country. With population predicted to reach 100 million in 2030, the annual available amount of water per person will decrease. Population growth and the effects of climate change are expected to reduce water availability from less than 1 400 m3 per capita today to 1 120 m3 per capita by 2030. Water stress, defined as the ratio of water abstraction to available resources, is much higher than the average for OECD member countries (Chapter 1). The agricultural sector, especially irrigation (with almost 70% of total water abstraction), dominates water use in Turkey, as it does in several other OECD member countries, such as Greece, Spain and Mexico (Figure 5.1).

Figure 5.1. Irrigation dominates water use in Turkey

Throughout the country, water resources are unevenly distributed in time and space. Rivers often have irregular flows due to climate conditions and variations in topography. Water resources are considered limited in the highly urbanised and industrialised western part of Turkey.

Recent studies demonstrate that Turkey will soon become hotter, more arid and unstable in terms of precipitation patterns (Chapter 4). These changes, along with population growth, are expected to reduce water availability in many areas. This is of particular concern for basins such as Marmara, K. Menderes and Asi, where water availability is already less than 1 000 m3/capita. Agriculture and energy production will also increase pressure on water quantity and quality (IPCC, 2014).

Water-use efficiency is likely to play a prominent role in Turkey’s future water policy. Conserving the quantity and quality of water resources is essential for the country’s long-term growth and sustainability. Untreated wastewater makes water use downstream more expensive. Significant investment is required to provide access to appropriate levels of treatment across the nation, to renew infrastructure and to adapt to a changing climate.

Turkey can do more to target and manage water risks in a changing climate, especially in areas prone to hazards. Studies of current and projected impacts of climate change on urban wastewater systems are at initial stages. Flash floods in urban settlements and combined sewer overflows are issues of mounting significance. The EU-funded project on Enhancing Adaptation Action in Turkey is expected to study the impact on ecological services and vulnerable socio-economic sectors, including urban wastewater. It will focus on four pilot urban areas representing four climate zones (MEU, 2016a).

5.1.2. Pressures

Point and diffuse sources of pollution

Surface water quality, considered low in many water bodies, is deteriorating due to insufficient pollution control. The impact is reaching alarming levels in some large municipalities. Groundwater quality and levels are also of concern. Groundwater is often contaminated by leakages from wastewater infrastructure and municipal waste dump sites. Yet households and agriculture increasingly use groundwater as a resource.

The problem of discharges of untreated wastewater from urban and industrial areas is exacerbated by the buoyant economy (Gürlük and Ward, 2009). In 2016, about 4.5 billion m3 of wastewater was discharged from municipal sewerage. Over 14% of the residential wastewater was discharged without treatment, and about 38% of industrial wastewater was not treated before being discharged into water bodies (TurkStat, 2018). There is little documentary evidence that eutrophication is widespread in the country or primarily related to point source discharges (municipal wastewater or industrial wastewater) or agricultural run-off. However, Turkey has recently designated inland and coastal areas as “sensitive areas” or “potentially sensitive areas”.

Economic and social pressures on water abstraction

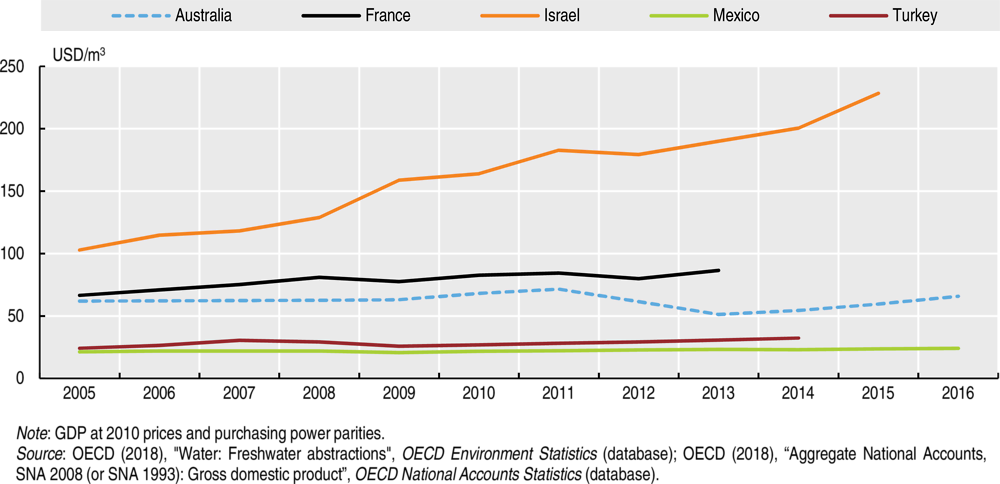

Water use in Turkey is less efficient than in high-income countries. For example, gross domestic product (GDP) per tonne of water used is only about 35% that of France. The value, which reached 32 USD/m3 in 2014, has not grown much in recent years (Figure 5.2). The inefficient use of water in agriculture results in over-abstraction of water from both surface water and groundwater in several river basins. Inefficient surface irrigation methods such as flooding, furrow and border are widespread (Chapter 1).

Figure 5.2. GDP per tonne of water used in Turkey trails behind the best performers

State of urban infrastructure for wastewater collection and treatment

A remarkable effort has been made to increase wastewater collection and treatment for people living in metropolitan areas. Between 2006 and 2014, Turkish water utilities connected an average of 4 800 people to a sewer and provided wastewater treatment to an additional 6 850 people daily. Over the same period, as its population increased by 7 million, Turkey extended sewer access to 14 million people, and access to wastewater treatment to 20 million people. It decreased the ratio of wastewater discharged without treatment from 36% (1 226 million m3) in 2006 to 14.3% (642 million m3) in 2016 (Turkstat, 2018). This significant progress was made with technical and financial support from national and international funds.

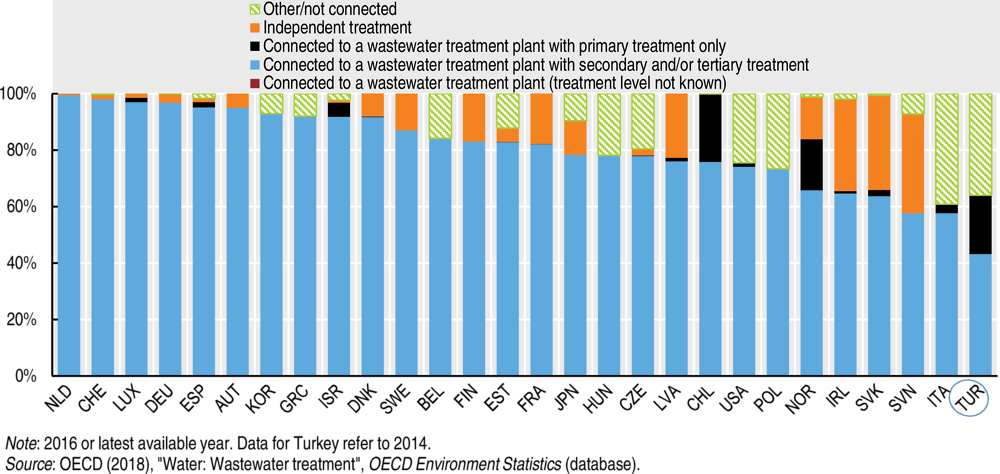

The share of the population served by wastewater treatment plants increased from 36% to 70% over 2004‑16 (Turkstat, 2018). However, the percentage of the population connected to secondary or tertiary wastewater treatment is still one of the lowest among OECD member countries (Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3. Access to wastewater treatment has increased, but remains among the lowest in the OECD

Turkey’s Regulation on Urban Wastewater Treatment (2006) reflects the requirements of the Urban Wastewater Treatment Directive (UWWTD), but there are problems with its implementation. For example, Turkey does not yet regulate or monitor water pollutants based on conditions of receiving water bodies at the basin level. Such differences in regulatory requirements may lead to unnecessarily high capital costs. They may also embed higher long-term operation and maintenance (O&M) costs when applied to new infrastructure. Turkey is committed to move towards full alignment with the UWWTD.

The impacts of climate change on resources and energy costs encourage policies that promote treated wastewater reuse and biological digestion of sludge wherever it makes economic sense. These could reduce costs and contribute towards water and energy security, serving both economic and environmental agendas. Turkey could benefit from increasing wastewater reuse, particularly in the water-stressed municipal areas.

Biogas production through digestion (and using it to meet utilities’ energy needs), sludge composting or reuse, and treated wastewater effluent reuse are not common practice in Turkey. A small number of pioneering municipalities have piloted these innovative practices. For example, biogas production through sludge digestion, sludge composting and reuse, was trialled in Ankara, while Konya evaluated treated wastewater reuse. Turkey most commonly disposes of sludge in landfills or through incineration. These expensive solutions do not exploit more sustainable reuse opportunities. Similarly, the use of sludge in agriculture is not common in Turkey, as it is in most EU countries (EC, 2016).

Storm water management

Higher intensity of precipitation events (heavy rains) from a changing climate will increase the amount of storm water needing treatment. Storm water in urban environments can be heavily polluted with nutrients, hydrocarbons, heavy metals, pesticides and animal waste. This polluted water is typically discharged untreated. In the case of combined sewers, large storms can result in raw sewage and polluted storm water bypassing the wastewater treatment facility (MEU, 2012).

The average annual rainfall in Turkey is 643 mm, and 7 of 25 basins receive rainfall below this average. Mountainous coastal regions receive abundant precipitation (1 000‑2 500 mm/year), while most parts of Central Anatolia and South-eastern Anatolia have precipitation of only 350‑500 mm annually. The lowest precipitation level (250‑300 mm/year) is in the environs of Lake Tuz (country submission).

Most sewerage systems in Turkey are combined systems, but there are some separate systems in Istanbul, Izmir and Antalya. There are no statistics available on the volume of untreated wastewater discharged through combined sewers or the number of annual overflow episodes.

In the context of future challenges related to climate change, Turkey assigns a high priority to storm water management. It could reduce the polluting effects of storm water overflows through water-wise urban design, use of natural water retention systems and improved management of networks connected with treatment plants. These activities require additional investments (BMI, 2014). In the framework of harmonisation with the UWWTD requirements, Turkey is considering investments to reduce storm water overflows and partially renew/improve infrastructure (e.g. in case of combined sewers).

5.2. Governance framework

5.2.1. Institutional arrangements

Turkey is taking important steps towards re-organising the institutional, policy and legislative framework of its water sector. Improved governance, increased institutional capacity and improved infrastructure for wastewater treatment are among the priorities for the Turkish government in the EU harmonisation process.

Role of national and provincial governments

Water-related roles and responsibilities of different ministries were reshuffled in 2011. At the central level, the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF) and the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization (MEU) hold the main responsibilities for the water sector (Chapter 2). The MAF regulates and monitors performance of water supply services; the MEU does the same for sanitation. The Strategy and Budget Office of the Presidency (formerly Ministry of Development) is also involved in decision making.

The MEU determines treatment standards for wastewater treatment plants, issues discharge permits and monitors the performance of wastewater facilities. It also regulates wastewater tariffs and implements an operational programme for related investments.

The MAF develops policies for protection of water resources and their sustainable use, regulates water supply and co‑ordinates national water management. The MAF’s General Directorate of State Hydraulic Works (GDSHW) and General Directorate for Water Management (GDWM) are key authorities in managing water resources.

The GDWM, established in 2011, develops policies for protecting and sustaining water resources, and co‑ordinating and preparing river basin management plans (RBMPs) together with relevant stakeholders. The GDWM also identifies and monitors urban-sensitive areas and nitrate-sensitive areas. The GDSHW oversees investments in the supply of potable and industrial water, and, if required, in municipal wastewater treatment plants.

Development and investment bank

ILBANK, Turkey’s development and investment bank, provides credits to municipalities and acts as an agent in the administration of municipalities’ external loans. It has a major influence on municipal investments, a large share of which is in water supply and sanitation (WSS). It establishes the creditworthiness and therefore the acceptable debt level of all local governments.

Roles and responsibilities of municipalities

Municipalities provide water supply and sanitation services, as well as storm water management. In 1981, as a pragmatic response to water shortages and sewage problems in Istanbul, the government introduced a new service model in the city. It established a dedicated Water and Sewerage Administration (SKI) as a public utility owned by the municipality, but with an independent budget. The Istanbul SKI was entrusted to finance large WSS investments through international loans.

By 2014, Turkey had created 30 metropolitan municipalities by consolidating smaller ones in main urban areas, and created an SKI in each of them. The service area of metropolitan municipalities was extended to cover the entire province. As a result, 30 SKIs provide WSS services to 77% of the population (World Bank, 2016a). Other municipalities provide WSS services through a municipal department (about 847 municipalities with 16% of the population). Special provincial administrations provide services in non-municipal areas (rural population, about 5 million people) (TurkStat, 2014).

SKIs are also responsible for drainage and protection of water basins, even those outside the boundaries of their service area. The governance structures of SKIs include a general board, a management board and auditors. The Metropolitan Municipality Council serves as the general board of an SKI. Key responsibilities of the general board include review and approval of the five-year investment plan and annual investment programmes.

5.2.2. Interagency co‑ordination at the national and subnational levels

The government is moving to address fragmented governance for water and wastewater management. In 2012, it created a Water Management Co‑ordination Board to ensure inter-sectoral co‑ordination and co‑operation, to oversee an integrated basin management approach, and to develop strategies, plans and measures to achieve Turkey’s national objectives and international commitments. The programme of measures for each RBMP is submitted to the board for approval. However, the board has met only four times since its establishment.

In addition to the Water Management Co‑ordination Board, the Basin Management Central Committee co‑ordinates activities in the 25 basins and receives reports of Basin Management Committees. Multi-stakeholder Water Management Co‑ordination Committees in 81 provinces complete the water management structure. Turkey is committed to strengthening a legal basis for the central board and other water management committees.

Still, responsibility sharing between the main sectoral ministries (MAF and MEU) can be unclear, particularly in standards setting and investment approvals. This may lead to confusion, inefficiencies and delays. For example, any wastewater collection and treatment project requires approval of the GDWM (under the MAF) and of the MEU for a treatment plant, except investment projects developed by government institutions themselves. The MEU decides the level of treatment based on sensitivity of the receiving body. However, the MEU depends on the MAF, which determines the level of sensitivity. Furthermore, in many cases, approvals involve ministries of health, tourism and agriculture. Having to deal with so many institutions in decision making on wastewater collection and/or treatment investments makes it challenging for utilities to secure project approvals. It also requires utilities to manage contradicting conclusions or requirements.

The government has prepared a draft Water Law to eliminate overlapping responsibilities of different government authorities to ensure effective co‑ordination and enable public participation in water management practices. A national policy dialogue on water could be another opportunity for inter-sectoral co‑ordination (Box 5.1).

Box 5.1. National policy dialogues in Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia

National policy dialogues (NPDs) on water are the main operational instrument of the European Union Water Initiative (EUWI) component for Eastern Europe, Caucasus and Central Asia (EECCA).

NPDs, driven by demand from host countries, are policy platforms where stakeholders meet to advance water policy reforms. Meetings are attended by multiple stakeholders, such as ministries and other government institutions, parliamentary bodies, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), academia and the business community.

Discussions in NPD meetings are supported by robust analytical work and international best practice. For instance, reviews of water pricing benefit from assessments of affordability and competitiveness impacts of alternative pricing scenarios. Development of RBMPs builds on similar experiences in European countries.

The main outcomes are policy packages, such as legislative acts, national strategies, ministerial orders and plans for implementation. In many cases, these apply the principles of the EU water policy.

EECCA countries benefit from the ongoing EUWI NPDs in part through better co‑operation with EU Member States. Improved co‑ordination with donors on water issues helps increase cost-effectiveness of official development assistance provided by EU Member States, as well as other donors. Furthermore, NPDs provide opportunities to transfer best practices and knowledge from EU Member States and international organisations (foremost, the OECD and UN Economic Commission for Europe, which facilitate NPDs) to beneficiary countries.

The OECD has established similar platforms in Brazil, the Republic of Korea, Mexico and the Netherlands.

Source: OECD (2016a), Water Policy Reforms in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia.

5.2.3. Regulatory framework

Efforts to achieve harmonisation with EU legislation have influenced the development of Turkey’s water supply and sanitation regulatory framework. The tenth Development Plan assigns clear priority to improving sewerage and wastewater treatment infrastructure and ensuring its proper operation to meet discharge criteria identified for respective river basins.

Regulations and standards

Until recently, water pollution control and urban wastewater treatment regulations had different treatment standards for biological oxygen demand, chemical oxygen demand (COD) and total suspended solids (TSS). This led to many water utilities and private operators selecting for each parameter the more stringent requirement of the two regulations to comply with both. This issue was addressed as of 2018 when urban wastewater discharges became subject to the Regulation on Urban Wastewater Treatment only.

The MEU has power to require nitrogen and phosphorus removal in secondary treatment plants for settlements with at least 50 000 inhabitants to prevent eutrophication of water bodies. Indeed, Turkey has designated inland and coastal areas as “sensitive” or “potentially sensitive” to eutrophication. Turkey has identified water bodies sensitive to eutrophication. It has transposed relevant provisions of the EU Urban Wastewater Treatment and Nitrates Directives into national legislation.

RBMPs need to recognise trade-offs in wastewater collection and treatment. Nutrient removal requirements involve more complex and expensive treatment systems. They can also drive O&M costs up by more than 40%, mostly due to the cost of electricity and chemicals. In addition, nutrient removal generates about 30% more sludge, which can become a significant problem to handle. Long-term costs of sludge transportation and disposal to landfill, for example, are rarely quantified. Conversely, following UWWTD standards will avoid investments in urban wastewater treatment that would generate little or no social or environmental benefit.

Turkey is planning to address wastewater infrastructure deficiencies as part of priority setting for each river basin. This, in turn, is expected to be based on robust cost-benefit analysis and supported by financing strategies. The designation of “sensitive areas” should be reviewed once RBMPs are in place (by 2023) based on a better understanding of the receiving environment conditions.

Regulation of tariff structure and levels, as well as standards and quality of WSS services is carried out by two ministries (Section 5.2.1). Consolidating responsibilities for regulating economic aspects of WSS service provision within one government body would be advisable in the future.

The MAF has taken first steps to establish a benchmarking system for WSS services, including the structure and level of tariffs. These efforts are worth pursuing and expanding. Such a system should allow monitoring of actual performance of WSS facilities and costs of their services. This is critical for evaluating the impact of the sector’s policies and programmes, and ensuring public accountability for tariffs and public investments.

Furthermore, international good practices suggest that having an independent economic regulator is an effective way of driving performance and investment of WSS service providers through best practice guidelines, procedures and benchmarking. Portugal represents one example of independent economic regulation in the water sector (Box 5.2).

Box 5.2. The role of the regulator in Portugal

The Portuguese water and waste services regulation authority was created in 1997 to do the following:

ensure protection of water and waste sector users, focusing on improving quality of services and supervising the tariffs charged to end-users

ensure equality with regard to access to water and waste services

reinforce the public right to general information regarding the sector and each utility.

Under the scope of economic regulation, the Portuguese regulator (ERSAR) is committed to a tariff system that includes a tariff definition and structure, as well as rules for invoicing of services. Tariff-setting procedure follows the principles of recovery of investment and operating costs. It includes annual costs for maintenance and renewal of infrastructure and equipment. It also serves to drive utility efficiency and promote sustainable use of resources. Economic regulation by ERSAR also includes evaluation of each utility’s capital investment plan.

To accomplish these goals, ERSAR publishes a tariff regulation and general recommendations for tariff renewal to standardise tariff calculation by the utilities. Audits may analyse the basis for approved tariffs, assess their level of compliance with the tariff regulation and/or validate accounts and supplementary data as part of ex post economic and financial performance review. In the event of non-compliance with the tariff regulation, the regulator may alert the utility of the need to correct some aspects or issue binding instructions in this regard. Where justified, the regulator may open administrative procedures against the utility and apply penalties.

Source: ERSAR (2018), “Entidade Reguladora dos Serviços de Águas e Resíduos” [Regulatory Body for Water and Waste Services], Lisbon, Portugal.

5.3. Policies and instruments

5.3.1. Key strategies and policy objectives

Turkey has started to integrate targets of the Sustainable Development Goals into planning documents. The tenth National Development Plan (NDP) sets clear objectives and targets for the sustainable use and effective management of water resources. It is consistent with Goal 6 on ensuring availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all. The plan emphasises improving sanitation and wastewater treatment infrastructures in cities and encouraging reuse of treated wastewater. It also covers basin-level planning, integration of quantity and quality measures, enhanced co-ordination among different government authorities and increased water efficiency (MoD, 2014).

There is a strong need to support harmonisation of urban development planning with priorities set through river basin planning. Turkey has various national strategies, plans and programmes that deal with water resource management. A National Water Information System is expected to gather all water-related data to support integrated planning and decision making in the water sector.

The National Basin Management Strategy aims to determine a set of policies for sustainable management of basins. It defines objectives for relevant institutions, and promotes co‑ordination between public and private sectors, NGOs and scientific institutions. Turkey has already identified 25 hydrologic basins, defined “sensitive water bodies, urban-sensitive areas and nitrate-sensitive areas”, and completed a river basin protection action plan (a precursor of an RBMP) for each. RBMPs are expected to be developed by 2023 for all 25 basins.

Several institutions involved in water governance have developed their own strategies or plans relevant to WSS development. These include the National Basin Management Strategy, Basin Protection Action Plans, the National Climate Change Strategy and the National Climate Change Action Plan. The MEU has completed an investment prioritisation for wastewater and sanitation services, while the MAF has prepared a Drinking Water Action Plan for settlements. For both sectors, decisions on allocation of funds are taken by the Strategy and Budget Office of the Presidency.

The tenth NDP sets key sanitation targets for 2018. First, it aims at 95% for “the ratio of municipal population served by sewerage system to total municipal population”. Second, it aims at 80% for “the ratio of municipal population served by a wastewater treatment plant to total municipal population” (MoD, 2014). At the same time, according to the MEU’s Strategic Plan (2013‑17), 85% of municipal wastewater is expected to be treated by the end of 2017. The same plan, already being updated to cover 2018‑22, anticipates total coverage of municipal population by wastewater treatment services by the end of 2023.

5.3.2. Economic instruments and incentives

Approximation with the EU’s WFD requires the use of economic instruments, particularly water pricing, to cover the costs of water services. Economic instruments have a double purpose: providing incentives for sustainable water use by the various user groups and raising revenue. The latter is particularly important in Turkey, where water infrastructure needs financing for operation, maintenance and new investment. International good practices suggest that economic instruments work best when designed to address one particular objective (see Box 5.3 on the French experience).

Turkey is committed to moving towards full cost recovery in its water pricing. According to the 2010 Regulation on Procedures and Principles for Determination of Tariffs for Wastewater Infrastructure Facilities, wastewater fees are determined on the basis of full cost recovery. The Environment Law imposes the “polluter pays” principle: the polluter must clean up the damage or pay the costs incurred by the MEU for the clean-up.

Box 5.3. French water policies rely on a combination of economic instruments

Since 2008, French water agencies charge seven types of taxes in the following categories:

Water pollution. For households, this tax is based on the annual volume of water billed. For cattle breeders, the tax is based on the size of the cattle herd. For industries, it is based on the annual discharge volume.

Sewerage system. This tax is paid by all users connected to a sewerage system and based on volumes of drinking water supplied.

Diffuse agricultural pollution. This is paid by retailers of pesticides with the rate varying according to toxicity of the substance.

Abstraction of water resources. This tax is paid by any water user, based on annual volume of withdrawals. Rates depend on water uses and water bodies.

Storage in low water periods. Owners of water reservoirs pay this tax.

Obstacles on rivers. This tax is for structures like aqueducts that could impact river characteristics such as flow patterns.

Protection of the aquatic environment. Fishers pay this tax through their unions.

In 2012, local authorities were granted the right to levy a tax to finance urban storm water management. It became the eighth water management tax in France.

In addition, France is considering charges to meet specific policy objectives. For instance, local authorities have recently been offered the possibility to charge for impervious surfaces. The objective is to discourage the extension of sealed surfaces – as they increase and accelerate run-off in cases of heavy rains – and to raise funds to finance the costs of storm water management.

Source: OECD (2012).

5.3.3. Information-based instruments

Water accounting provides a conceptual framework for organising economic and hydrological information. This enables consistent analysis of the contribution of water to the economy and of the impact of the economy on water resources.

The Turkish Statistical Institute (TurkStat), with its 26 regional offices, is the leading authority for overall data collection, statistical accounts, analysis and reporting services. The Department of Environment, Energy and Transport Statistics has been collecting and analysing data sets based on an OECD core set of environmental data and indicators since 1990. Data on water, wastewater, waste, air emissions, environmental employment, environmental expenditure and revenues, and environmental accounts are collected via questionnaires filled in by municipalities and other agencies.

Turkey does not have monetary water accounts or hybrid water accounts. Economic valuation of water and its application to making strategic decisions on water allocation would be an important step in making well-informed decisions in the water sector. TurkStat has implemented some pilot projects for the development of Physical Water Flow Accounts. These accounts refer to the abstraction of water resources, water use by different economic sectors and water flows back to the environment. The Strategy and Budget Office of the Presidency, TurkStat and the MAF are keen to conduct valuation to explore and better understand the economic contribution of water resources to economic growth and to modify the national accounts accordingly. Furthermore, the MAF is willing to integrate water valuation as a key component of river basin management (World Bank, 2016b).

A fragmented monitoring system impairs the assessment of performance of urban wastewater management. The Urban and Industrial Pollution Monitoring Program is carried out in six priority river basins (Ergene, K. Menderes, Gediz, K. Aegean, Sakarya and Susurluk) four times a year.

Some 250 parameters are subject to monitoring of environmental quality of surface water resources. In 2017, the MEU designed a roadmap for wastewater management. One of its elements was reducing the number of monitored polluting parameters and selecting them based on ambient water quality conditions at the basin level.

The Communiqué on Continuous Wastewater Monitoring Systems (2015) lays down procedures for online monitoring activities for wastewater treatment plants with capacity of 10 000 m3/day or above. Online monitoring stations measure seven parameters (pH, dissolved oxygen, temperature, flow, conductivity, COD and TSS). Monitoring results are collected from facilities through a real time system, and data are recorded in a centralised system.

Turkey will continue to improve monitoring of discharges and systematically reflect the pollution dilution and absorption capacity of the receiving water bodies as it may have an impact on the cost of treatment plant requirements. Turkey also needs a better understanding of ecosystem health to know whether water and land management and the controls on abstraction and pollution are effective and sustainable. Ecological conditions downstream of a major discharge can indicate whether permit limits are being regularly breached, in a way that occasional effluent samples might not be able to.

5.3.4. Performance of water utilities

There is no benchmarking system for the provision of WSS services that allows monitoring of actual performance of WSS facilities and of services they provide. Without proper information, government authorities cannot credibly assess whether objectives are adequate, investment plans are efficiently implemented or expected results are achieved. Reliable information is critical for evaluating sector policies and programmes, and ensuring accountability before the public for results achieved through tariff-revenue spending and other public investments.

The GDWM of the MAF has initiated a benchmarking system. The by-law that requests municipalities and SKIs to report to MAF annually on water losses, and to publish these reports on the Internet for one year, is a step in the right direction. However, a system that would require service providers to monitor, regularly report on key technical and financial performance indicators, and make this information available to the public, would further increase accountability (see Box 5.4 on the Portuguese experience).

Box 5.4. Measuring performance of water service providers in Portugal

The Portuguese water and waste services regulation authority (ERSAR) annually assesses the quality of service provided by almost 400 water and wastewater utilities against a series of 14 performance indicators.

The indicators have been developed to evaluate the efficiency or effectiveness of utility services. They address service coverage, affordability, flooding occurrences, cost recovery, sewer rehabilitation and method of sludge disposal. Each performance indicator has reference values for “good”, “average” and “poor” quality of service. Performance indicator results receive a green, yellow or red score in a “traffic light” rating system.

Data reported by utilities are validated through audits that assess data quality and reliability. Each data set is classified from “very reliable” to “less reliable” according to the source.

In parallel with the performance indicator assessment, ERSAR is pilot-testing three indices developed on the principle that good management of water and wastewater systems requires:

good knowledge of infrastructures, their state of conservation and operation

a good short-, medium- and long-term plan of activities

good understanding of the water and wastewater flows in the systems.

These indices are the Infrastructure Knowledge Index, the Infrastructure Asset Management Index and the Flow Measurement Index. Collectively, they allow the regulator to evaluate each aspect listed above and support the performance indicator assessment.

Evaluating the quality of service provision in this way allows ERSAR to regulate by benchmarking. It enables the establishment of baselines and definition of best practices, simulating a competitive environment within the sector. This enables utilities to get an independent perspective of their performance compared to other utilities with similar operating conditions.

Results of the benchmarking assessment are published. This introduces “peer pressure” and drives utilities to address their individual performance issues in the context of the sector as a whole.

Source: ERSAR (2018), “Entidade Reguladora dos Serviços de Águas e Resíduos” [Regulatory Body for Water and Waste Services], Lisbon, Portugal.

5.4. Investment and financing

5.4.1. Investment needs

Construction of sewerage and wastewater treatment infrastructure has gained momentum since the mid-1980s. Significant further investment will be required to provide access to levels of treatment consistent with EU requirements in the context of a growing population and needs to adapt to a changing climate.

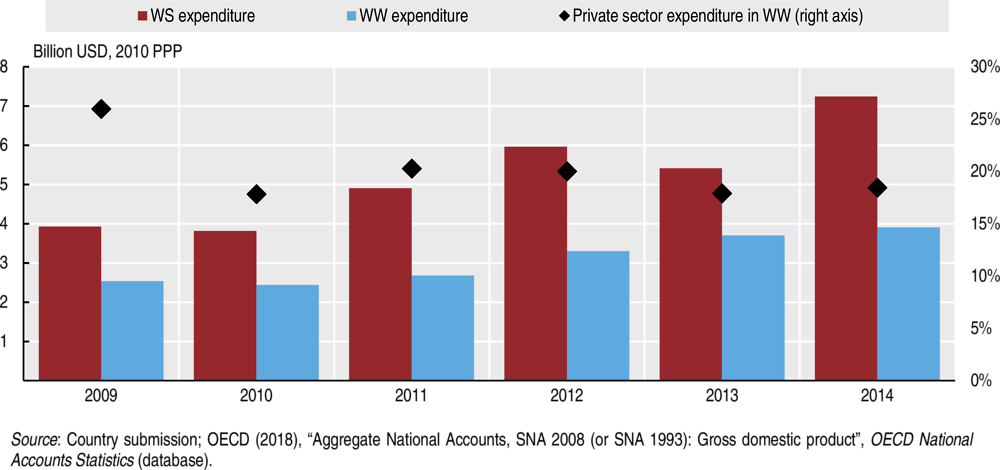

Expenditures of water utilities increased rapidly over 2009‑14 (Figure 5.4). The role of the private sector (private operators and domestic commercial financial institutions) in expenditure financing of wastewater management (e.g. build-operate-transfer schemes) is more prominent than in water supply. Notwithstanding the expenditure growth associated with the extension of the wastewater network and new wastewater treatment facilities recently put into operation, the share of private sector involvement remained quite stable, at about 20%. By contrast, water supply expenditure remains almost 100% public sector-financed.

Figure 5.4. Water supply and wastewater treatment expenditures are growing fast

Projected water infrastructure investment needs

The preliminary 2006 estimate of investment costs of compliance for the EU environmental acquis, including industrial, agricultural and urban infrastructure, was about TRY 110 billion (2017 USD 17.6 billion). The water and wastewater sectors have particularly high capital investment costs compared to other sectors. The total investment for the water and wastewater sector is estimated at around USD 9.8 billion until 2023 (MEU, 2016b).

The Wastewater Treatment Action Plan (2015‑23), prepared by the MEU in 2015 and updated in 2017, estimated the total investment cost of the wastewater treatment plants to be renovated or constructed by 2023 at TRY 8.9 billion (about 2017 USD 1.4 billion). The necessary renewal of sewerage networks would cost TRY 8.7 billion (2017 USD 1.4 billion) by 2023. In addition, the cost of new sewerage networks planned to be constructed until 2023 has been estimated at TRY 9.6 billion (2017 USD 1.5 billion). The total cost of the investments to be made until 2023 for urban wastewater infrastructure is thus estimated at TRY 27.5 billion (2017 USD 4.4 billion). A recent study estimated the costs of Turkey’s compliance with the UWWTD at USD 5.4‑6.6 billion in additional investments (World Bank, 2016a).

Turkey has to ensure the efficiency of new investments, including full consideration of future O&M costs and social implications. To meet wastewater treatment requirements over time, Turkey may consider gradual implementation, which is applied by some EU Member States such as Croatia and Bulgaria.

5.4.2. Financing strategy and capacity

Turkey has so far relied on international assistance programmes as an important source of finance for wastewater collection and treatment. Shifting to more predictable sources of finance such as tariffs for wastewater collection and treatment, with additional funding for storm water management, would put the sector on a more robust financial path.

Wastewater tariffs: Cost recovery and affordability

To ensure sustainability of environmental infrastructure services, the Turkish legislation empowers all wastewater infrastructure administrations to set up full-cost recovery water and wastewater user fees (i.e. tariffs covering installation, maintenance, operation, monitoring of wastewater treatment plants and other related services).

SKIs apply different water and wastewater tariffs depending on customer group. For example, the household tariff is discounted by up to 50% for customers with disabilities and veterans and by 25% for customers in a new SKI service area. This prevents tariffs from signalling the cost of pollution and of service operation. Targeted social measures are a more efficient use of taxpayers’ money than low tariffs that benefit people who could afford a larger share of the costs of service provision. Water and wastewater tariffs also vary significantly from one service area to another. For example, Gaziantep, Denizli, Istanbul, Izmir and Mersin have among the highest tariffs. In addition, a 2018 regulation provides for maximum and minimum tariff levels for each service area.

The available financial information does not allow to judge whether the tariff revenues are sufficient to cover O&M costs. It is reported that SKIs recently established in new metropolitan municipalities still show lower financial sustainability, while “old” SKIs have a reasonably high collection rate of tariff revenues.

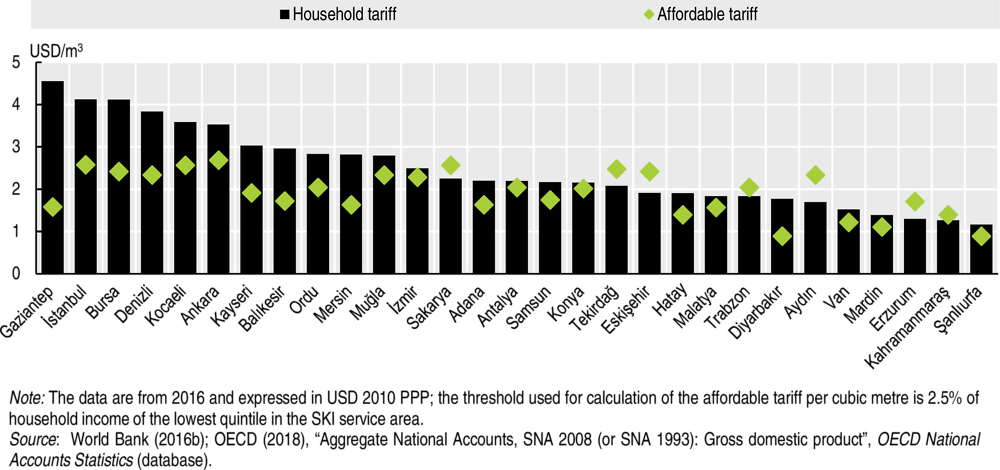

Only a small number of utilities still have capacity for tariff increases to finance new investments (Figure 5.5). Most utilities will have to implement cost-efficiency measures to accommodate higher capital costs within affordability constraints. Still, the share of wastewater fees in the total WSS tariff is less in Turkey than in most OECD member countries, where they account for roughly half of the total (OECD, 2012). This leaves some room for their increase based on a thorough assessment of the cost of pollution and service provision.

Figure 5.5. Household water and wastewater tariffs exceed affordability limits in many provinces

The EU Water Framework Directive stipulates that the tariff be set to allow a transparent vision of the cost recovery level. Implementation of the cost recovery principle requires that capital investments of utility services be financed from profits and depreciation of fixed assets. However, these funds are often insufficient to finance large investment needs.

In Turkey, when a municipality uses a loan to finance its capital investments, the full-cost recovery tariff includes a provision for debt service. However, to ensure capacity to pay, the tariff level should consider customer affordability. An affordable tariff per cubic metre is expected to be below 2.5% of the household income of the lowest quintile in the SKI service area in line with the current tariff regulation. Applying this threshold to all income groups does not provide proper incentives for water saving and deployment of cost recovery capacity of households (World Bank, 2016a).

To continue financing new investments from tariffs, the majority of Turkish municipal utilities will have to consider cost-efficiency measures. In this context, an economic regulator (Section 5.3.2) would help to respect an affordable tariff for poorest households, supported by targeted social measures, without compromising the full-cost recovery principle.

Domestic public finance and international aid

Turkish municipalities are supported by international loans and grants of the World Bank, the European Investment Bank, KFW and the Japan International Co‑operation Agency. The European Union also provides financial support under the EU harmonisation process in different areas. During the 2007‑13 budget period, the mechanisms of EU financial assistance to candidate and potential candidate countries were consolidated into a single Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA).

Over 2011‑17, the total water and wastewater investments by the Department of European Union Investments of the MEU reached USD 564 million. The European Union covered 85% of the cost of these projects, with the balance coming from the MEU and municipalities. In 2014, a Multi-Annual Action Programme on Environment and Climate Action for Turkey was approved under the IPA2 period with a maximum total contribution of EUR 182 million for 2014‑16. While in the previous IPA period thematic concentration of the Environment Operational Programme was mainly on water and waste, this programme, in addition, focuses on climate action.

Extensive international assistance requires capacity to develop and implement projects. Training and capacity building are critical to the efficiency and long-term technical and financial sustainability of wastewater service provision. While the importance of training and capacity building is well understood and acknowledged in Turkey, a comprehensive programme to build capacity of WSS service providers is yet to be established.

TurkStat reported USD 2.1 billion of expenditures in the wastewater sector in 2015-16 under the Wastewater Treatment Action Plan, while the EU contribution for the same two-year period remained about USD 136 million. This shows that the national budget, municipalities and water companies continue bearing major capital costs in the sector.

ILBANK was created to provide technical and financial support to municipalities. Funding is mainly provided from the national budget. The amount of investments by ILBANK over 2003‑15 is TRY 4.7 billion (USD 2.1 billion) for 648 sewerage projects and TRY 1.6 billion (USD 1.1 billion) for 182 wastewater treatment projects.

The government provides grants covering 50% of project costs to municipalities whose population is below 25 000. ILBANK extends long-term loans to municipalities for the remaining 50% of the project cost and supervises project implementation. ILBANK may also extend loans to municipalities with population above 25 000 under a decision of the Higher Planning Council. From 2011 to date, the total finance provided to municipalities for 1 028 projects is almost TRY 5.9 million (USD 3.9 million) (MoD, 2014).

The MEU provided about TRY 220 million (USD 146.4 million) to support 1 060 wastewater infrastructure development projects over 2008‑17, which accounted for 18% of total conditional financial aid to municipalities. Up to 50% of energy expenditures of wastewater treatment plants operated in conformity with the legislation is compensated by the MEU. Within this scope, for example, incentive payments made to municipalities in 2016 were in the region of TRY 38 million (USD 8.1 million).

5.4.3. Options to meet finance needs

Increasing operational efficiency and innovative solutions

The MEU has set a 2023 target to provide wastewater treatment service to the entire municipal population. This target will be difficult to meet. Challenges faced in financing wastewater treatment plant construction seem to be the biggest constraint in reaching that target.

A range of innovative options could be explored to reduce costs and increase water and energy security. Technical solutions such as biogas production through sludge digestion can help reduce energy costs. Non-technical options include aggregating small utilities to generate economies of scale and make the best use of larger infrastructure. Indeed, in 2014, Turkey started to consolidate WSS services at the level of metropolitan municipalities. This trend will continue with amalgamation of smaller municipalities in coming years. This framework has encouraged service providers to finance large-scale investments through international loans under the Treasury Guarantee Scheme.

More efficient O&M of assets can reduce costs, while improving water security and services. Urban utilities in OECD member countries increasingly rely on computer tools, inspection robots and geographical information systems to gain precise knowledge of the state and performance of their assets, particularly those buried underground. This knowledge allows them to better phase their maintenance and renewal investments to improve system reliability, particularly with regard to repairing damaged pipelines. Innovative tools help enlarge the scale and scope of infrastructure monitoring, and extend the time horizon for asset management (OECD, 2015).

Replacing and expanding wastewater systems under a traditional engineering approach is very capital-intensive. It is worth exploring more efficient, lower-cost alternatives such as constructed wetlands for wastewater treatment (Box 5.5). These options should be compared using proper cost-benefit analysis.

Box 5.5. Ecosystems provide cost-effective wastewater treatment

Making use of processes occurring in natural ecosystems can be a lower-cost alternative to advanced wastewater treatment plants. Sewage treatment functions – equivalent to tertiary treatment processes – can be found in different natural and semi-natural systems, including floating aquatic plants and constructed wetlands.

Natural treatment systems represent the most cost-effective option in terms of both construction and operation, providing certain conditions are met. Operating costs, such as energy, are minimal compared to other treatment methods. However, natural systems have high land requirements and require frequent inspections and constant maintenance to ensure smooth operation. Furthermore, natural biological systems can produce effluents of variable quality depending on the time of year and type of plant, although they can handle fluctuating water levels.

According to the Centre for Alternative Wastewater Treatment, the capital costs of ecologically based wastewater treatment systems is USD 126-303 per m³ treated per day, while for traditional systems it is USD 593-741 per m³. Aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems are used for sewage treatment in a number of locations throughout the world, providing both low-cost sanitation and environmental protection.

Source: OECD, 2012.

Reflecting on future infrastructure needs for urban water management, countries now recognise that large-scale centralised systems may no longer be viable. This is due to high maintenance costs and resource needs, strong path dependency (particularly, when cities are already equipped with extensive grey infrastructures) and limited capacity to adjust to shifting conditions (urbanisation, climate change). The analysis holds true for water supply and wastewater infrastructure, storm water collection and drainage. Careful infrastructure decisions need to be made in light of these considerations and to be linked to long-term planning.

Private sector financing

Options for using private investment sources to fund urban water management include water service operators, financiers (who do not operate water services) and property developers. Private operators’ capacity to generate efficiency gains can help to reduce financing needs. Most OECD member countries consider some form of private-sector participation as an option to channel additional sources of financing to bridge upfront investment needs.

Turkey is planning to expand public-private partnerships for construction and operation of wastewater treatment plans in the coming years. However, these partnerships may succeed only if they are a result of a well-designed policy and institutional framework, and will require independent regulation of the sector (Section 5.3.2).

Mobilising commercial finance, in particular domestic sources, is another option to attract additional financing to the water sector. Blended finance (e.g. using development finance as collateral) is a promising approach to scale up financing flows for water. Further, blended finance can significantly improve the risk-return profile of water-related investments for commercial financiers and private operators. However, attracting these finance sources also requires policy reforms of the water sector to promote efficiency gains, cost reduction and cost recovery (OECD, 2018).

Recommendations on urban wastewater management

Institutional and regulatory framework

Continue to strengthen the institutional framework by clarifying roles and responsibilities in the water sector.

Adjust wastewater treatment standards based on consideration of carrying capacity of receiving water bodies and robust cost-benefit analysis to avoid excessive capital and operational infrastructure costs; consider phased implementation of treatment requirements.

Consider consolidating responsibilities for regulating economic aspects of WSS service provision within one government body.

Strategic planning

Develop a single water strategy that would cover all water management aspects at the national level and be aligned with economic development and urban planning objectives.

Harmonise national and municipal planning of water infrastructure development and management; use river basin planning to determine the level of ambition, priorities and financing needs.

Investment and financing

Develop and endorse robust and realistic financing strategies that cover O&M costs of existing assets, new investments and further developments identified in RBMPs.

Issue national guidelines for improving WSS services; encourage better utility O&M performance to facilitate financing of further investments and O&M costs and keep tariffs affordable.

Innovation

Continue aggregating small utilities to generate economies of scale and make the best use of larger infrastructure; introduce other new business models for water and wastewater utilities.

Continue expanding the role of the private sector to improve performance and leverage private financing, particularly from domestic sources.

References

BMI (2014), Turkey Water Report, Business Monitor International, London, www.dk-export.dk/media/1321242/bmi-turkey-water-report-q1-2015.pdf.

EC (2016), Turkey 2016 Report, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/pdf/key_documents/2016/20161109_report_turkey.pdf.

Gürlük, S. and F. Ward (2009), “Integrated basin management: Water and food policy options for Turkey”, Ecological Economics, Vol. 68/10, Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 2666-2678, https://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/ecolec/v68y2009i10p2666-2678.html.

IPCC (2014), Climate Change 2014, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.), Geneva.

MEU (2016a), State of the Environment Report for Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, Ankara.

MEU (2016b), EU Integrated Environmental Approximation Strategy 2016-2023, Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, Ankara.

MEU (2012), Climate Change Action Plan, Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, Ankara, http://iklim.cob.gov.tr/iklim/Files/IDEP/%C4%B0DEP_ENG.pdf.

MoD (2014), The Tenth Development Plan, Ministry of Development, Ankara, www.mod.gov.tr/Lists/RecentPublications/Attachments/75/The%20Tenth%20Development%20Plan%20(2014-2018).pdf.

OECD (2018), “Financing water: Investing in sustainable growth”, OECD Environmental Policy Paper, No. 11, www.oecd.org/water/Policy-Paper-Financing-Water-Investing-in-Sustainable-Growth.pdf.

OECD (2017), Diffuse Pollution, Degraded Waters, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris,

OECD (2016a), Water Policy Reforms in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia, OECD National Policy Dialogues on water in EECC, Paris, www.oecd.org/env/outreach/EUWI%20Report%20layout%20English_W_Foreword_Edits_newPics_13.09.2016%20WEB.pdf.

OECD (2016b), OECD Council Recommendation on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.oecd.org/environment/resources/Council-Recommendation-on-water.pdf.

OECD (2016c), “Water, growth and finance”, Policy Perspectives, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.oecd.org/environment/resources/Water-Growth-and-Finance-policy-perspectives.pdf.

OECD (2015), Water and Cities: Ensuring Sustainable Futures, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264230149-en.

OECD (2014), The Governance of Regulators, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264209015-en.

OECD (2013), Water Security for Better Lives, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.oecd.org/publications/water-security-9789264202405-en.htm.

OECD (2012), A Framework for Financing Water Resources Management, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264179820-en.

OECD EAP Task Force (2010), Proceedings from the Regional Meeting on Private Sector Participation in Water Supply and Sanitation in EECCA, www.oecd.org/env/outreach/48493702.pdf.

TurkStat (2018), Water Statistics (database), Turkish Statistical Institute, www.turkstat.gov.tr/PreTablo.do?alt_id=1019 (accessed 16 October 2018).

World Bank (2016a), Turkey Sustainable Urban Water Supply and Sanitation, World Bank, Washington, DC, www.worldbank.org/en/country/turkey/publication/turkey-sustainable-urban-water-supply-and-sanitation-report.

World Bank (2016b), Turkey's Future Transitions: Systematic Country Diagnostic, World Bank, Washington, DC, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/783401489432683796/pdf/112785-SCD-PUBLIC-TR.pdf.