The Assessment and recommendations present the main findings of the OECD Environmental Performance Review of Turkey and identify 36 recommendations to help Turkey make further progress towards its environmental policy objectives and international commitments. The OECD Working Party on Environmental Performance reviewed and approved the Assessment and recommendations at its meeting on 7 November 2018. Actions taken to implement selected recommendations from the 2008 Environmental Performance Review are summarised in the Annex.

OECD Environmental Performance Reviews: Turkey 2019

Assessment and recommendations

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

1. Environmentwal performance: Trends and recent developments

Turkey is the eighth largest OECD economy and the fastest growing. Real gross domestic product (GDP) increased by 83% over 2005-17, and the GDP per capita gap narrowed from 46% of the OECD average to 63% during the same period.

Since the last Environmental Performance Review (EPR) in 2008, Turkey has made progress in relatively decoupling its strong economic growth from a range of environmental pressures (air emissions, energy use, waste generation and water consumption). However, rapid economic, population and urbanisation growth is likely to aggravate these pressures. Integration of environmental protection into economic plans and implementation of key environmental policies with necessary financial and human resources need to be accelerated.

Transition to an energy-efficient and low-carbon economy

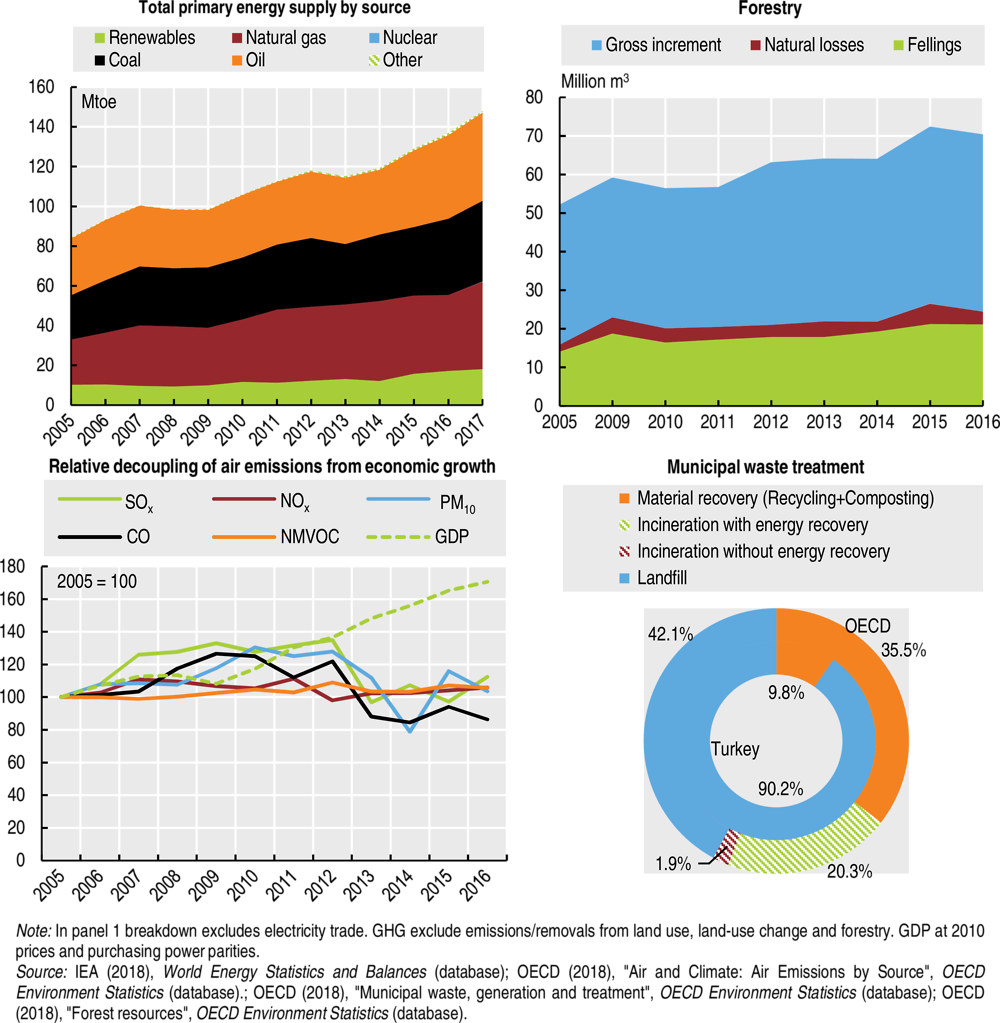

Turkey’s energy mix remains carbon-intensive, with fossil fuels representing 88% of total primary energy supply (TPES) (Figure 1), above the OECD average of 80%. The country is highly dependent on imported energy, notably oil and natural gas. Energy self-sufficiency is only 25%. Turkey’s energy demand growth is among the highest in the OECD: TPES has increased by 76% since 2005. This trend is expected to continue for the medium and long term (MEU, 2016a). Reducing energy dependency and improving energy security is a top policy priority. Turkey plans to reduce import dependency and ensure energy security by diversifying imports, integrating regional markets, increasing domestic production (especially lignite and renewables, but also nuclear energy), fostering energy efficiency, preventing wastage and reducing consumption. There could be tension between the objectives of reducing import dependency (by relying on domestic coal) and curbing air emissions (by replacing coal with imported natural gas in heating systems). Turkey has one of the largest coal plant developments in the world (IEA, 2016), which would make the energy mix more carbon- and emission-intensive.

The country has important renewable energy sources, which need to be better utilised. Turkey figures among the top world performers in installed capacity in recent years, especially in solar, wind, geothermal and hydropower (REN21, 2018). Recent competitive auctions for large-scale solar and wind projects have been successful in driving investment. Other off-shore wind and on-shore wind and solar projects have been planned as envisaged by the National Renewable Energy Action Plan. The share of renewables in TPES is higher than the OECD average. However, it has remained stable since 2005, as conventional energy sources have met most of the increase in energy demand. Energy intensity has decreased since 2005, but not at a steady pace, and remains dependent on economic conditions. The need to improve energy efficiency is highlighted in the 2017-23 National Energy Efficiency Action Plan (NEEAP) and several other policy documents. However, the overall target to save 23.9 Mtoe of primary energy consumption (24% of total consumption in 2016) by 2023 is not broken down by sector (Section 4). For instance, despite building and heating being a priority, there are no quantitative targets and timeframes for reducing energy consumption in private buildings. Existing measures, such as energy performance certificates and tax breaks on real estate income for energy-saving expenses, may fall short of the stated objectives. It is important to translate the energy efficiency objectives of the NEEAP into adequately funded plans with measurable targets.

Figure 1. Selected environmental performance indicators

Strong economic growth and high levels of energy consumption, together with a road‑dominated transport system, have caused large increases in greenhouse gas (GHG) and air pollutant emissions. Turkey’s economy has the highest GHG emission growth among OECD member countries. GHG emissions have followed closely GDP growth and have been relatively decoupled only in recent years. The government expects part of GHG emission mitigation to come from significant development of renewable energy, especially in the power sector, by increasing solar and wind generation capacity and better utilising the hydroelectric and geothermal potential.

Air pollution and quality are major concerns, especially in large cities and industrialised regions. Population exposure to fine particulate matter is higher than the EU standards and the World Health Organization’s guidelines. Coal-based heating systems and industrial and vehicle emissions are the main drivers of GHG and air pollutant emissions growth. Air pollution has relatively decoupled from economic growth in recent years. However, emissions have increased since 2005, except for carbon monoxide.

Limit values for most air pollutants are expected to align with EU standards by 2019. The 2008 Regulation on Ambient Air Quality Assessment and Management is mainly implemented through local Clean Air Action Plans (CAAPs). CAAPs have been enacted in 64 of 81 provinces. The main measures relate to industry, residential heating and road transport. Implementation is, however, slow due to high municipal staff turnover, frequent amendments to the legislation regulating roles and responsibilities, and limited technical and human resource capacity at the provincial and municipal levels, especially in less developed regions.

Given their weight in air emissions, road transport and power generation are areas for intervention. In the transport sector, the government needs to stimulate a modal shift from private road to public transportation, use integrated urban planning, promote alternative fuels and renewal of the truck fleet (Section 3). In the power sector, the use of coal should rely on efficient and clean coal technology. This would mean refurbishing or closing down old plants. The envisaged gradual substitution of coal with natural gas in residential heating would reduce local air pollution. These measures would also help reduce emissions of black carbon, a contributor to climate change.

Transition to a resource-efficient economy

Turkey is a resource-intensive economy. Domestic material consumption has not decoupled from economic growth. As a consequence, material productivity has been decreasing since 2005, to only pick up in recent years thanks to high economic growth. The government has the double objective of reducing import dependency and making consumption sustainable. To that end, it aims at using domestic natural resource potential more effectively, reducing waste and moving away from a disposal-centred approach, and promoting a circular economy. However, the government does not have a dedicated material resource policy.

Waste management is key to reducing import dependency by promoting a more circular economy. Turkey has been making progress by aligning almost completely with waste-related EU directives and by reducing the generation of municipal and hazardous waste (EC, 2016). Although waste generation has decoupled from economic growth and progress has been made in recycling, most municipal waste is still sent to landfills, and only a small quantity is composted or recovered (Figure 1). Turkish authorities are seeking solutions to reduce the amount of municipal solid waste going to landfills and to increase recycling of materials. However, low investments at the local level remain a challenge. Furthermore, although the number of waste recovery facilities has increased, Turkey has been slow in improving hazardous waste treatment, and relevant legislation has not yet been fully implemented.

Legislative progress has been made in chemicals management. A regulation on chemicals registration, evaluation, authorisation and restriction was adopted in 2017. Legislation was harmonised with the EU Seveso II and III Directives. On the other hand, Turkey does not yet have a pollutant release and transfer register (PRTR) and does not provide open access to information related to chemical accidents. A draft PRTR regulation has been prepared, but its adoption is uncertain. The Rotterdam Convention on international trade of hazardous chemicals was ratified in 2017, and draft regulations have been prepared to align legislation with EU regulations on export and import of hazardous chemicals and on persistent organic pollutants.

Managing the natural asset base

Turkey is a hotspot of biodiversity and has made progress on conservation, increasing the coverage of protected areas. According to national data, combined terrestrial and marine protected areas accounted for 9% of the national territory in 2017. This is significantly lower than the Aichi target of 17% for terrestrial and inland water, and 10% for coastal and marine areas. The National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan has been revised in line with Aichi targets, but Turkey has not yet submitted national targets under the Convention on Biological Diversity. A number of conservation and monitoring activities are being carried out: there are plans to build bio-corridors along major roads and a nationwide 2013‑19 project on biodiversity monitoring and inventory. Research on site detection, protection of biodiversity and restoration of endangered species habitat is being done. Agro‑biodiversity research and genetic characterisation studies have also been carried out since 2001. However, habitat loss and fragmentation continue as a result of urban, transport and industrial expansion. Furthermore, responsibilities across ministries – namely the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry and the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization – need to be better co‑ordinated.

The country has made progress in expanding the forest cover thanks to afforestation, erosion control, rehabilitation of degraded forests and pasture, and artificial regeneration. Unlike in many other OECD member countries, natural and semi-natural areas, as well as forest cover, have increased. Turkey is among the OECD member countries with the lowest forestry use intensity. On the other hand, rapid urbanisation has led to urban sprawl encroaching on natural areas.

Turkey is not a water-rich country, and water resources are not distributed evenly. Renewable freshwater resources per capita are well below the OECD average, and projected population and water-use growth will increase water stress. Competition for water access across sectors is growing. This competition is expected to become more challenging with increased urbanisation, expansion of irrigation areas and climate change (OECD, 2016). Management plans are expected to be prepared for all river basins by 2023.

Water stress is aggravated by losses/leakages throughout the supply network, and water quality is becoming a serious concern. Overuse of natural resources, discharges of untreated industrial and domestic effluents into freshwater bodies and the sea due to unplanned and rapid urbanisation, insufficiency of wastewater treatment facilities (Section 5), and diffuse nitrogen and ammonia pollution from agricultural activities, all contribute to decreased water quality (MEU, 2016a). A marine pollution monitoring programme is being carried out, but eutrophication is a problem in several coastal areas.

Recommendations on energy, air pollution and natural resource management

Energy

Reduce the share of fossil fuels, especially coal, in the energy mix and increase the share of renewables, especially geothermal (in residential heating), solar and wind; set a revised energy transition roadmap with quantifiable targets by energy source to provide clear signals to investors.

Set measurable objectives in the NEEAP in the power, residential and transport sectors; provide more economic and fiscal incentives for energy efficiency investments in public and private buildings.

Air pollution

Formulate a comprehensive nationwide air pollution reduction strategy, integrated with energy and transport policies and plans; strengthen the implementation of local clean air programmes and ensure their alignment with nationwide objectives.

Material resources, waste and chemicals

Adopt a comprehensive and dedicated material resource policy going beyond waste management, with quantitative targets and an appropriate monitoring system.

Promote separate collection of different types of municipal solid waste; reduce the volume of biodegradable waste going into landfills and increase biogas generation; prepare local waste management plans while promoting inter-municipal collaboration.

Strengthen the institutional and administrative capacity to implement national programmes for prevention, preparedness and response to accidents involving hazardous substances; adopt a legal framework for collecting, and providing public access to, information on pollution releases by industry sector and by pollutant.

Biodiversity

Clarify roles and responsibilities for biodiversity protection across ministries; improve routine biodiversity monitoring and inventory activities; continue the work to establish bio-corridors connecting protected areas.

2. Environmental governance and management

Turkey’s environmental regulatory framework has been substantially strengthened since 2008, primarily as a result of continued efforts to harmonise its environmental legislation with directives of the European Union (EU). This demonstrates the country’s ambition to upgrade and modernise its environmental regulation. However, progress in implementing EU standards and best practices has been uneven across policy areas.

Institutional framework

Turkey has a centralised system of environmental governance, where most powers are exercised by the national government and its territorial institutions. Environment-related responsibilities are fragmented across several ministries. The Ministry of Environment and Urbanization (MEU) has key regulatory responsibilities, but other ministries develop and implement energy, water resource management and biodiversity protection policies.

Horizontal co‑ordination is facilitated by environmental boards at the national and provincial levels under the aegis of the MEU and water management committees at the central, river basin and provincial levels chaired by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF). However, not all of them meet frequently and systematically engage all stakeholders in decision making. Responsibilities for municipal environmental services are divided differently depending on the administrative status of the province, adding management complexity.

Regulatory requirements

In line with recommendations of the 2008 EPR, Turkey has made remarkable progress in bringing its environmental regulatory framework closer to the European Union’s environmental acquis. As a result, regulatory standards in many environmental domains have been strengthened. Despite the uncertainty of Turkey’s EU accession process, there is a need to continue aligning the country’s legislation with best international practices.

Progress in environmental evaluation of regulations and policies has been partial. Regulatory impact analysis that includes environmental considerations is carried out only for laws of major economic significance. A regulation on strategic environmental assessment (SEA) of plans and programmes was adopted in 2017. Its implementation (for new plans and programmes) will be phased in through 2023, but will not cover local spatial plans. So far there have been only pilot SEA projects. There is no ex post evaluation of policies or legislation.

The evaluation gap is particularly important in land-use planning, as emphasised in the 2008 EPR. Spatial plans at all administrative levels are aligned with development plans and, in the absence of SEA, address environmental concerns only to a limited extent. The development of integrated coastal zone plans has not been completed.

Environmental impact assessment (EIA) and permitting processes have been simplified by using electronic systems. However, there is room for improving the implementation of these instruments: the mechanism to ensure compliance with impact mitigation measures described in the EIA report needs to be strengthened. EIA is not used in the transboundary context. Turkey has introduced a consolidated environmental permit, but its conditions are not yet based on best available techniques (BAT) and favour end-of-pipe pollution control – it has only partly implemented the respective 2008 EPR recommendation. Temporary operation certificates allow installations to operate before they obtain an environmental permit. Turkey plans to introduce BAT-based permitting in 2024.

Compliance assurance

The MEU has made considerable efforts to build capacity of its inspectors through training and use of a software to plan, report and evaluate inspections. It is implementing risk-based inspection planning, scoring regulated facilities based on their environmental impact and compliance record. However, much remains to be done to make the compliance monitoring regime more efficient: less than 20% of inspections are planned, and inspection numbers had until 2017 been rising faster than non-compliance detection.

Environmental enforcement relies largely on administrative fines, whose total annual amount has nearly doubled in constant prices since 2008. Criminal sanctions may be used in addition to administrative ones. Turkish law establishes strict liability for damage to human health and property, but similar provisions regarding damage to soil, water bodies and ecosystems need to be strengthened. Turkey created a register of contaminated sites in 2015, but there is no planning or regular budget allocation for remediation of abandoned sites.

Environmental authorities are not proactive in promoting green business practices. Turkey lags behind similar-size OECD economies in environmental management system certifications, which have declined since 2008. Green certification initiatives have been launched for hotels and the construction sector, but their uptake by businesses has been limited. The integration of environmental aspects into the country’s public procurement policies has been slow.

Environmental democracy

Turkey’s progress in ensuring public participation and access to information and justice on environmental matters has been uneven. The development of environmental legislation, policies and programmes is open to stakeholders through special consultative committees. The public has opportunities to participate in EIA, spatial planning and, potentially, SEA, but not in environmental permitting. However, any party has to prove that it is directly affected by an environment-related administrative decision to challenge it in court.

Some environmental information is available to the public, mainly through the MEU website. Environmental information held by public institutions is accessible upon request. However, this access is hampered by broadly interpreted “economic interest” restrictions and processing fees. Turkey does not have a PRTR (Section 1), and data on environmental impacts by individual companies are not publicly available.

The country has made progress in implementing environmental awareness programmes, mostly through distribution of printed materials on environmental impacts and good practices. The school curriculum integrates environmental matters into several science and social studies courses.

Recommendations on environmental governance and management

Institutional and regulatory framework

Strengthen the role of environmental boards in horizontal co-ordination of environmental aspects of energy, transport and other sectoral policies; reinforce the National Sustainable Development Commission and expand its institutional membership.

Implement the regulation on SEA for public plans and programmes, including all local spatial plans, and build related institutional capacity; expand regulatory impact analysis to secondary legislation and ensure consideration of potential environmental impacts of all regulatory proposals; introduce ex post evaluation of policies and legislation.

Strengthen the EIA system by systematically reflecting identified impact mitigation measures in environmental permits and implementing EIA in a transboundary context.

Make best available techniques the basis for setting conditions in environmental permits for high-risk installations; phase out temporary operation certificates.

Compliance assurance

Implement risk-based planning for environmental inspections in all provinces and define minimum inspection frequencies for different categories of installations.

Adopt legislation to impose strict liability for damage to soil, water bodies and ecosystems and establish appropriate remediation standards; create a fund for remediation of abandoned contaminated sites.

Use different information channels to deliver advice and guidance on green practices to the business community; expand sector-specific green certification programmes; establish binding environmental criteria for public procurement.

Environmental democracy

Enhance mechanisms for public participation in drafting environmental legislation, policies and programmes, as well as in the permitting process.

Remove restrictions and fees for access to environmental information held by public institutions; give the public access to environmental permits and compliance records using recently created electronic information systems; establish a PRTR open to the public.

3. Towards green growth

Turkey has made progress in several areas related to green growth since the 2008 EPR. Environmental and sustainable development considerations have been increasingly integrated into National Development Plans (NDPs), the main tool used to provide overall strategic direction. There are signs of emerging eco-innovation, particularly in the automotive and renewable energy sectors, and new industry-led initiatives in improving environmental sustainability. To fully shift towards green growth, Turkey would need to increase the scale and scope of this effort. The pace of growth and urbanisation is too rapid for incremental action to have a significant impact. Policies, such as fossil fuel subsidies and investment in new coal facilities, are slowing progress.

Framework for sustainable development and green growth

Turkey has made progress on some Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), but further effort is needed on environmental goals to transition towards a green growth path of development. Without accelerated action, air pollution, water scarcity and quality, and impacts of climate change will increasingly act as constraints on growth. Turkey is also at risk of missing out on market opportunities in environment-related products without scaling up policy measures supporting domestic eco-innovation across all sectors. Turkey could benefit from the Paris Collaborative on Green Budgeting launched by the OECD, France and Mexico in December 2017. This initiative helps governments to green fiscal policy and embed environmental objectives into their national budgeting and policy frameworks.

Additional effort is needed to drive co‑ordinated implementation of policy commitments across institutions and sectors, breaking down silos and improving programme evaluation to ensure efficient and effective progress. Turkey is ready to publish an initial set of about 80 SDG indicators based on available data. However, financing for data collection and generation, as well as effective communication of indicators, remains a challenge. Improved evaluation of programmes is needed to ensure continued progress.

Greening the system of taxes and charges

Turkey has among the highest rates of environmentally related taxes as a percentage of GDP in the OECD, largely as a result of high taxes on gasoline and diesel fuel. However, gaps remain: low taxes on coal and natural gas, higher taxes on gasoline than diesel, and substantial fuel tax exemptions. Vehicle taxes do not fully reflect the environmental costs of their use.

Energy taxes do not reflect the full environmental costs of fuel production and use. In 2015, 51% of carbon emissions from energy use were unpriced and only 21% of emissions were priced above EUR 30 per tonne of CO2 (OECD, 2018a). Broader and higher levels of carbon pricing would drive the investment and innovation needed to realise environmental objectives and capture economic opportunities in growing markets. Concerns related to the economic impact of reform can be addressed through careful design, gradual implementation, revenue recycling and complementary measures that support continued economic growth. Although Turkey has not committed to implement carbon pricing, a 2016 study for the MEU laid out a possible path towards cap and trade, recommending starting with a pilot emission trading system (ETS) for a period of two to three years before moving to a full cap and trade system (Ecofys, 2016). Turkish companies are already actively involved in the global voluntary carbon market.

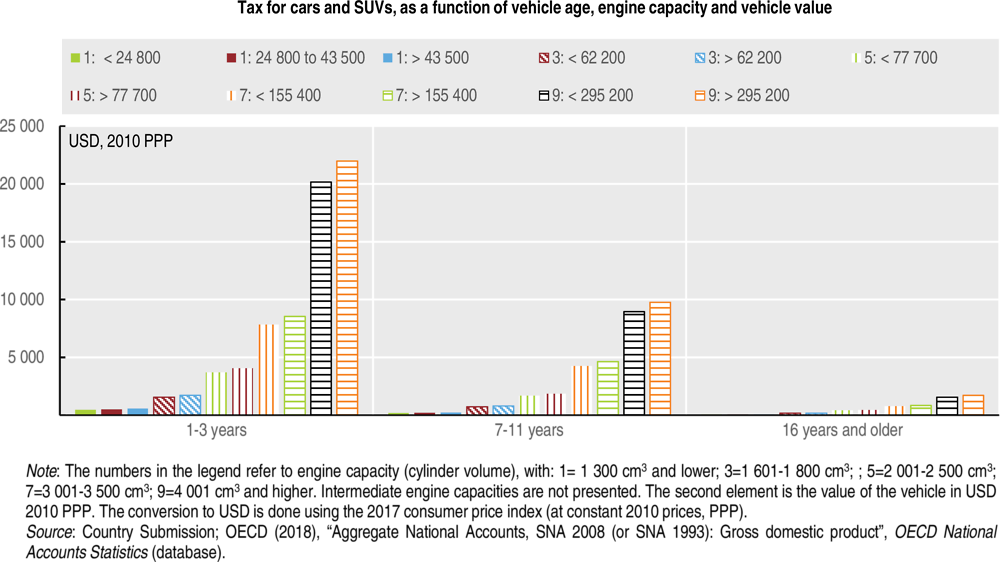

The transport sector is the second highest energy consumer and fastest growing source of GHG emissions. Turkey’s vehicle taxation system provides some environmental incentives, but generally pushes consumers towards older, used vehicles that are likely to have higher emissions. There are two types of vehicle taxes: a special consumption tax (SCT) paid at purchase and a motor vehicle tax (MVT) paid annually. The taxes are relatively high, meaning they have a tangible impact on consumer decision making. Since the SCT does not apply to purchases of used vehicles or leases, as is standard practice, consumers have a strong incentive to purchase older, used vehicles or enter into leases. To discourage the use of very old vehicles, the government introduced a new measure in 2018 that reduces the SCT if a vehicle 16 years and older is exported or scrapped. Both the SCT and MVT are higher for vehicles with larger engines, which generally aligns well with environmental objectives. Electric and hybrid cars are also encouraged by lower SCT rates. The MVT, which was increased at the beginning of 2018, provides an incentive for electric vehicles, but also has lower rates for older and cheaper vehicles (Figure 2). The taxes are not differentiated based on fuel or emissions, which contributes to increased demand for diesel vehicles (whose share rose from 34% of vehicles in 2005 to 50% in 2017) (TurkStat, 2018a).

Figure 2. Motor vehicle taxes favour older, cheaper cars with smaller engines

Motorways in Turkey charge tolls based on distance travelled, and a number of bridges are also tolled. In cities, however, driving is not taxed by municipal governments. Turkey’s cities have some of the worst air pollution in Europe: 4 are in the top 100 most congested cities in the world (TomTom, 2018). Istanbul is the sixth most congested city. Experience in London, Stockholm, Milan and Singapore has shown that congestion pricing can reduce traffic volume, limit pollution and raise revenue that can be invested in valuable transportation infrastructure and public transit. Istanbul – the largest and most congested city in Turkey – would be the logical place to introduce more comprehensive congestion pricing, starting with district pilot projects and an active educational campaign for residents.

Turkey’s introduction of a feed-in tariff for renewable energy in 2010 provided a strong incentive for investment. Those that successfully bid for government renewable tenders are able to receive the feed-in-tariff, generating significant interest. However, there are some concerns that high contribution fees are delaying or stalling installation for some of the licensed solar projects. Progress will need to be closely monitored to ensure that incentives are sufficient to move forward with projects.

Eliminating environmentally harmful subsidies

Turkey continues to provide substantial environmentally harmful subsidies. Revised OECD estimates that incorporate new data and additional tax exemptions show that fossil fuel support is over nine times higher than estimated in 2008 (OECD, 2018b). Fuel tax exemptions for petroleum products represent most of this increase. The new fuel price stabilisation mechanism is expected to reduce tax receipts further. The highest tax expenditures are for high-emission bitumen and petroleum coke fuels. Coal production and fossil fuel exploration also continue to be subsidised.

Subsidising the use of coal by poor families is the most significant direct budgetary expenditure. Aimed at supporting vulnerable households, this policy contributes to continued use of coal as a heating fuel, which is a source of air pollution and has a direct negative impact on health. However, the government has been implementing a transition to natural gas heating as community pipeline access improves (Section 1). By the end of 2018, all provinces are expected to be supplied with natural gas, leading to a gradual removal of coal aid. Alternative renewable options may also be encouraged. There are already 120 000 households and greenhouses heated by geothermal or solar energy.

Turkey has made improvements regarding agricultural subsidies, with the elimination of a subsidy for water use and new payments for soil conservation and organic farming. However, most agricultural water pricing is not yet tied to the volume of water used, and subsidies for organic farming and good practices represent a small share of total support.

Investing in the environment to promote green growth

Public environmental spending, which is the main source of environment-related financing, has fluctuated since 2008. Most of it focused on waste, water and wastewater services, with very little spent on biodiversity protection. In addition to public resources, funds for environmental investments are provided by multilateral development banks, bilateral development agencies, the European Union and other external sources. Business environmental expenditures have grown since 2008, with a similar focus on wastewater management. Business spending in other environmental areas, such as air and climate, is very low.

Energy efficiency is an opportunity to reduce energy costs, as well as air pollution and GHGs. The government could consider enhancing current incentives to better capture this opportunity. Industrial establishments consuming more than 1 000 toe are already required to be certified to the ISO 50001 energy management system standard, but only 8% of large energy-intensive installations had been certified as of 2016 (Janssen, 2016). Voluntary agreements can also be reached to benefit from energy efficiency subsidies, but only 15 have been or are being completed. Carbon pricing and phasing out fossil fuel subsidies would also help drive greater investment in energy efficiency.

Infrastructure investment has been significant over the past decade. Over USD 100 billion of public and private funds has been invested in capital projects and infrastructure since 2012. Investment is expected to triple by 2023 to meet government objectives (Garanti and PwC, 2017). However, the ability to borrow in foreign markets and attract foreign investment may be affected by the significant drop in value of the Turkish lira in 2018 (OECD, 2018c). According to plans for 2023, the majority of investment will go to the energy and transportation sectors, making investment decisions critical for Turkey’s future environmental performance. Roads are expected to account for 25% of future infrastructure investment, compared to railways at 9% (Garanti and PwC, 2017). Modal shifts from road to rail and public transit will be increasingly important in addressing congestion and air pollution. Renewables (12%) and nuclear energy (11%) will dominate energy-related infrastructure investment, relative to coal power (5%) (Garanti and PwC, 2017). Ideally, all new major investments should go through cost-benefit analysis to consider environmental externalities such as air pollution and GHG emissions.

Investment needs are also substantial in environmental services: about USD 10 billion for water and wastewater, and about USD 7 billion for waste management by 2023 (MEU, 2016c). Irrigation infrastructure modernisation should be a priority within the context of looming water constraints, given that agriculture is the primary consumer of water. Modernisation has started: new projects are designed with drip and sprinkler irrigation, and open canals are turned into closed canal systems.

Turkey’s use of public private partnership (PPP) financial models for infrastructure financing has increased significantly, in line with OECD recommendations. However, it has mainly been used for airports, highways, energy and health infrastructure. A few water and rail projects have also used a PPP model. Turkey’s domestic financial sector plays an important role in infrastructure financing. However, in recent years foreign banks have been increasingly involved in PPP transactions. Nevertheless, more could be done to reduce real and perceived risks of environment-related investments for traditional investors. Green banks have been a successful tool internationally to reduce real or perceived risk associated with environmental projects. The USD 300 million Green Sustainable Bond issued by the Industrial Development Bank of Turkey in 2016 attracted significant international demand, highlighting the potential for expanded use of such instruments.

Promoting eco-innovation

To capture greater economic benefits from a transition to green growth, Turkey needs to scale up policies that expand the domestic market for environmental goods and services (EGS) and support Turkish innovators and entrepreneurs developing environmental solutions. In 2018, Turkey introduced ecolabel legislation that is in line with the EU Ecolabel Regulation. Broadening the coverage of environmental policies to a greater number of sectors and environmental issues, increasing stringency over time and phasing out subsidies and other policies that give existing products a competitive advantage will help to further expand the domestic market.

According to OECD Statistics, Turkey has historically not made significant investments in environment-related research and development (R&D) through to commercialisation in comparison to other OECD member countries. However, the government has recently developed policies that encourage R&D related to renewable electricity and electric vehicles. There are also several general R&D programmes that support clean technology, waste reuse and energy efficiency projects. Patent applications in environment-related technologies represent a relatively small percentage of total patent applications in Turkey (6% compared to the OECD average of 10.9% for 2012-14), but there are some recent signs of growth in the areas of environmental management, energy and buildings.

Turkey’s plan to develop a national electric car holds significant promise, given the country has the fifth largest automotive sector in Europe. The government also plans to stimulate domestic demand through investments in charging infrastructure and incentives for widespread clean vehicle use. Carbon pricing, vehicle emission standards and phasing out gasoline and diesel tax exemptions would also improve uptake.

The solar thermal industry also has potential. Turkey is already among the top five countries in the world using solar energy for hot water heating, but space heating has received less attention. Turkey has two solar companies that rank in the top 12 of global flat plate collector manufacturers. Phasing out subsidies for coal heating and increasing incentives for renewable and district heating would help expand the domestic market for Turkish companies. New heat supply legislation aimed at establishing a well-functioning domestic heat market is expected to be completed by the end of 2018.

Contributing to the global environmental agenda

Turkey is one of the largest recipients of official development assistance (ODA) commitments in the world, though its ranking has fluctuated significantly over the past decade. The proportion of aid that is environment-related has also fluctuated over time. Renewable energy has increased in importance since 2010. Turkey has also increased its disbursements since 2008, reaching 0.95% of gross national income in 2017 (OECD, 2018d). Turkey undertakes development co-operation activities with African, Central Asian and neighbouring countries, with some environmentally-related aid for water and sanitation, and energy efficiency improvements.

Turkey’s largest trading partner is the European Union. A recent analysis concluded that the customs union and other trade agreements have had a negligible impact on the environment. While increased economic activity has had a negative environmental effect, this has been offset by improved performance in energy and steel sectors. Turkey’s free trade agreements (FTAs) have included limited reference to environmental issues. Exceptionally, the Korean FTA included a full chapter on trade and sustainable development.

Although foreign direct investment has declined since 2008, it is expected to play a growing role in Turkey, particularly in the transportation and energy sectors. Chinese companies and state-owned enterprises, for example, are major investors in several Turkish coal power projects. Turkey is building its first nuclear power plant with Russian investment. Japan is also a growing source of investment, given the pending FTA, mainly in automotive consumer electronics, energy and food. Investors can influence environmental performance through their selection of projects, as well as through design and implementation.

Corporate social responsibility initiatives are growing in the Turkish private sector, with particular interest from large, export-oriented companies that are conscious of the trend towards increased demand for sustainable products and suppliers. The Borsa Istanbul (Turkey’s stock exchange) established a Sustainability Index in 2014 to help institutional investors find companies that have high environmental, social and governance performance. The Turkish government could encourage expansion of these initiatives through information provision, guidelines and financial incentives.

Recommendations on green growth

Framework for sustainable development and green growth

Continue prioritising sustainability and green growth in public policies, better align fiscal policies and budget allocations with environmental commitments, leveraging all available domestic and international sources of financing.

Continue to integrate SDGs into NDPs and action plans across institutions and sectors; enhance implementation efforts; finance data collection needed to monitor progress and programme effectiveness.

Greening the system of taxes and charges

Reform the system of vehicle and fuel taxation to remove exemptions and integrate emissions criteria; introduce congestion pricing in Istanbul to limit traffic and air pollution.

Closely monitor the uptake of incentives for renewable energy to ensure that fees, project size requirements and approval processes do not deter investment.

Eliminating environmentally harmful subsidies

Phase out tax exemptions for fossil fuel consumption; gradually replace coal aid to poor families with support for transition to cleaner alternatives.

Tie water pricing in agriculture to the volume of water used and increase financial incentives for organic and other environmentally friendly practices.

Investing in the environment to promote green growth

Improve consideration of environmental externalities in evaluation of major investments by using tools such as comprehensive cost-benefit analysis.

Expand the use of instruments that leverage private sector investment in environmental projects, including public-private partnerships for rail and public transit, green banks to reduce risk for traditional investors, and green bonds.

Promoting eco-innovation

Evaluate strategic opportunities identified in domestic and global EGS markets; develop an integrated approach to support clean technology entrepreneurs from early stage R&D through to commercialisation and export.

Strengthen the policy framework for eco-innovation by increasing spending on environmental R&D, supporting technology demonstration and commercialisation with an expanded number of clean technology incubators, and integrating greater awareness of EGS market opportunities into education and skills programming.

Contributing to the global environmental agenda

Promote corporate social responsibility initiatives such as sustainability reporting, certification, internal environmental performance targets and investment in environmental projects.

4. Climate change

Climate change impacts are already being observed in Turkey, with an increase in annual mean temperature, changes in precipitation patterns across the country and the seasons, and increasing numbers of climate-related hazards such as floods and droughts (TSMS, 2018). Turkey needs to ramp up both mitigation and adaptation to reduce the risks and costs arising from climate change to the society, the environment and the economy.

GHG emissions profile and trends

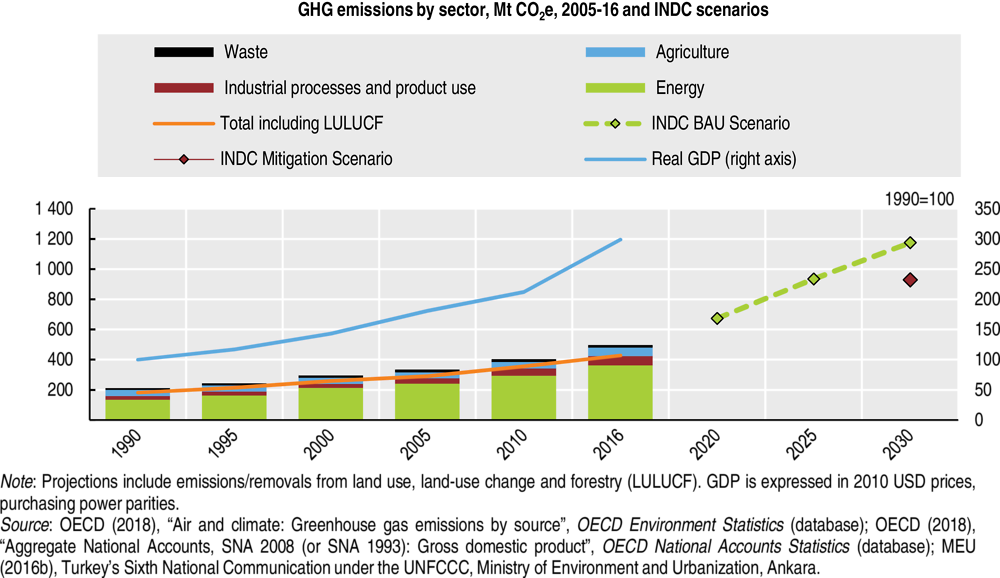

Driven by strong economic and population growth, rising income levels and continued reliance on a carbon-intensive fuel mix, Turkey’s increase in GHG emissions over the past decade (+49% over 2005-16, excluding land use, land-use change and forestry, LULUCF) was the largest in the OECD. Although there has been a relative decoupling in emissions in recent years and a decline in emissions intensity due to accelerated renewable energy development and improvements in energy efficiency, this decline is lower than in other member countries. Although still below the OECD average, emissions per capita are rapidly increasing. Turkey is in the top ten most emitting OECD countries, with close to 500 MtCO2e in 2016. The growing economy and population are expected to continue pushing GHG emissions upwards.

Despite its continued growth in GHG emissions, Turkey is alone within the OECD in not putting forward any mitigation target for 2020. It did, however, set a mitigation target for 2030 as part of its Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC) under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. Turkey ratified the Kyoto Protocol in 2009 and has signed, but not yet ratified, the Paris Agreement. The country aims to limit the increase in GHG emissions to up to 21% below its business-as-usual scenario. This means that absolute levels of GHG emissions can still more than double between 2015 and 2030 in the mitigation scenario (Figure 3). At this stage, Turkey does not plan a peak in its GHG emissions. CO2 savings from current and planned policy measures have not been estimated (UNFCCC, 2016).

Figure 3. Greenhouse gas emissions are expected to continue growing rapidly

Policy and institutional framework

Since the 2008 Environmental Performance Review (EPR), Turkey has taken the important step of developing and adopting its National Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan (NCCS 2010 and NCCAP 2011). These aim to lay the ground for the transition to a low‑carbon economy. However, the NCCAP lacks verifiable and quantifiable targets related to emission levels, as well as information on the expected mitigation impact and cost of the policies and measures. The overall status of implementation of mitigation and adaptation actions in the NCCAP remains unknown due to limited monitoring and evaluation. In addition, Turkey has announced targets for renewable energy and energy efficiency, which, however, vary from one policy document to another.

Renewable energy sources are developing rapidly but Turkey still relies heavily on fossil fuels. In order to reach its INDC, it aims to continue to increase the use of renewable energy (solar, wind, hydro and geothermal) and develop nuclear energy, increase energy efficiency in power plants and industrial installations, and improve its transport system. However, more efforts are needed in power generation and transport, where there is potential for decreasing CO2 intensity through fuel switching and energy efficiency. Turkey also relies on the sink capacity of its expanding forests to partially offset its increasing emissions.

Maintaining warming below 2°C relative to pre-industrial levels requires cutting GHG emissions levels to near zero by the end of the century (IPCC, 2014). It is advisable for Turkey to develop a long-term low-carbon strategy that would set a peak in GHG emissions and ensure that infrastructure investments are compatible with both energy security and climate goals (e.g. any new coal plants use best available technologies, and/or are compatible with carbon capture and storage). Energy and climate policies are not aligned and could potentially lead to some assets no longer able to provide an economic return due to changes associated with the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Climate change policies are developed by the Co-ordination Board on Climate Change and Air Management. This board gathers public and private institutions, as well as observers from other organisations, academia and NGOs on an ad-hoc basis. Tasked with implementation of the NCCS, it should also facilitate the discussion and integration of climate issues into other multi-stakeholder mechanisms such as the Economy Co‑ordination Board.

As a centralised state, Turkey is equipped to ensure top-down measures, but local aspects of climate change need to be better integrated into adaptation policies and measures. Action at the local level is starting to pick up with about ten municipalities (covering about 16% of the population) adopting climate change plans, but most of them only cover mitigation. The government needs to support local authorities in developing climate change adaptation plans both technically and financially.

Under the UNFCCC’s Paris Agreement, developed countries have committed to mobilise climate finance to assist developing countries in implementing climate change activities. This includes funding via bilateral and multilateral funds, such as the Global Environment Facility, the Green Climate Fund and other specific funds. Turkey sees access to the Green Climate Fund as one of the key negotiation points before ratifying the Paris Agreement. Turkey seeks to ensure equal treatment with countries having similar economic development levels under the UNFCCC and to receive international financial, technological, technical and capacity building support.

Turkey benefits from significant levels of funding through bilateral and multilateral channels, especially for mitigation activities. About USD 3 billion per year in climate finance was committed to Turkey in 2015-16, primarily in loans provided by multilateral banks. Further information on the use of public and private domestic finance would be required to properly analyse all financing trends for mitigation and adaptation.

Mitigation efforts across sectors

Mitigation in energy supply and power generation

Energy use, which accounts for most of Turkey’s GHG emissions, is expected to continue to increase. About half of Turkey’s carbon emissions from energy use do not face a price signal (Section 3). Renewables are growing, but Turkey’s energy supply is still highly reliant on fossil fuels (88%). It imports three-quarters of its energy supply, making energy security a concern. Turkey intends to make further use of domestic coal to strengthen energy security, but domestic supply has been complemented by growing imports of coal. Coal accounts for a large proportion (33%, 2017) of Turkey’s electricity supply, and the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources’ Strategic Plan indicates that coal-fired power will remain an important part of the electricity mix. The carbon-intensity of electricity generation from coal is above the OECD average and – unlike in many other member countries – has been increasing (IEA, 2018). In addition to carbon-intensive coal plants, Turkey also has the largest coal power plant development programme in the OECD (IEA, 2016). This is creating a high carbon lock-in risk due to the large capital costs and long infrastructure lifetimes.

Turkey has almost reached its renewable energy target (30% of renewable energy in its electricity mix) set for 2023, in part due to the introduction of feed-in tariffs. It has a significant potential for further developing renewable energy sources (for electricity and non-electricity uses) and recognises their critical role in reducing import dependence and mitigating climate change. It will be important to continue to increase the proportion of low-carbon electricity and define a new and more ambitious longer-term target for renewable electricity that would send a clear signal to investors. In this context, the implementation of the National Renewable Energy Action Plan (NREAP) should be monitored without further delay.

Mitigation in energy use

Continued efforts to improve energy efficiency are needed to support climate change mitigation, as well as energy security. Energy efficiency gains have contributed only marginally to reducing energy consumption (IEA, 2016). Turkey has recently adopted a NEEAP with a set of measures (Section 1), but it lacks official sectoral targets (MENR, 2018). Some measures (mainly grants) to encourage industry to adopt energy-efficient practices have been implemented. Turkey has developed a regulation in line with the EU 2002 Directive on Energy Performance of Buildings, but still does not reflect all the changes made to the directive in 2010, notably on minimum energy performance requirements.

Further efforts are needed to progress towards the 2011 NCCAP aim to reduce GHG emissions from transport. They have nearly doubled since 2005 and are expected to continue to rise. Most of these emissions come from road transport due to increasing road use and of relatively old and diesel cars that are taxed lower than gasoline cars on a carbon content basis (Section 3). There has been some development in the use of different transport modes in freight and passenger transport and clean vehicle technologies.

Mitigation in other sectors

Turkey has been successful in increasing its forest area, which represents an important sink for CO2 emissions. It intends to increase the sink capacity of its forests as a measure to reach the INDC, but this action represents a small part of the country’s mitigation potential. Continuing to improve monitoring is essential to explore possibilities of enhancing the role of the LULUCF sector in sequestrating carbon. Improving waste management is also important for mitigation and brings other co-benefits (Section 1).

Although emissions from agriculture have increased less dramatically than in other sectors, they are still on the rise. Emissions from this sector are difficult to address as there are fewer low-cost mitigation options. Some support measures for farmers to improve the sustainability of their practices have emerged (e.g. payments for soil conservation, concessional loans for adoption of good agricultural practices). Agricultural policies need to continue to integrate both mitigation and adaptation and encourage the uptake of cost-effective climate-friendly measures (OECD, 2016).

Adaptation to climate change

Climate change impacts and vulnerability

Turkey is already experiencing an increase in annual mean temperature, number of climate-related hazards and changes in precipitation patterns. Projected climate change impacts include reduced availability of surface water and more frequent arid seasons, with changes occurring unevenly across regions. Growing demand coupled with altered water regimes is expected to put further pressure on the water sector, already exposed to water stress. Droughts are expected to become more frequent and affect yields, putting food security at risk.

Adaptation efforts to date have concentrated on understanding risks arising from change in the climate, particularly to water resources. Progress has been made in modelling future changes, with the first national projections prepared by the Turkish State Meteorological Service. Continuing to fine-tune these projections, including clarifying the treatment of uncertainty, is important to better understand the degree of probability and related adaptation costs.

Building a solid evidence base will help Turkey make a socio-economic case for action and prioritise policy options. The knowledge gap is still important in terms of understanding sectoral vulnerability, and socio-economic impacts at the regional and local scales, as well as quantifying costs of these impacts. Turkey needs to sustain efforts to assess the vulnerability to climate change of its ecosystems (e.g. forests, biodiversity), economy (e.g. agriculture, tourism) and society (e.g. health). Other cross-cutting issues such as infrastructure (e.g. energy, water and transport) and disaster risk management also deserve particular attention, as they will be directly affected by climate change and can in turn contribute to aggravating exposure to risk and vulnerabilities.

Implementation and monitoring

Following the NCCS and its action plan, Turkey published a National Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan (NASAP) in 2011, which contributed to better understanding the impacts of climate change across its economy and society. Acknowledging the potential for improvement, Turkey is planning revision of the NASAP. The cross-ministerial adaptation working group convenes regularly and has the possibility of bringing adaptation to the attention of the Co-ordination Board on Climate Change and Air Management. There is considerable scope for better mainstreaming climate change adaptation into public sector operations such as policy or project appraisal.

Monitoring and evaluation of adaptation actions is useful for assessing whether policies have reached their stated goals cost-effectively and for ensuring accountability. However, it has been limited to date. It is difficult to assess progress towards the NASAP objectives, which are too broadly defined and not supported by measurable indicators. The absence of monitoring and evaluation also limits the possibility of identifying barriers to implementation. Some potential barriers include the lack of priority setting among actions and identified budget allocated to adaptation measures.

Mainstreaming adaptation

Adequately mainstreaming adaptation is key to ensuring that different sectors and people, whose vulnerability can be exacerbated by climate change, are prepared. Although Turkey has indicated that it aims to integrate climate adaptation into actions in relevant sectors, mainstreaming activities are still at an early stage and have largely focused on developing the evidence base. There is limited consideration of adaptation issues in many socio-economic sectors. Work is ongoing to better understand the diseases linked to climate change and to build capacity in the health sector.

Efforts to mainstream adaptation are mainly taking place in the water sector, where water plans need to take into account future climate impacts on water regimes. All 25 river basins have protection plans (Section 5). Expected to be completed by 2023 for all basins, comprehensive river basin management plans (RBMPs), as well as flood and drought management plans, require prior study of climate change impacts.

Forests, which are central to Turkey’s mitigation efforts, are at risk from climate change impacts (e.g. due to forest fires). Efforts to address these risks are focusing on monitoring the impacts and taking related precautionary measures. As a party to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification, Turkey has established a range of targets in its National Report 2016‑30 related to land degradation neutrality and has taken initial steps in mainstreaming adaptation into the LULUCF sector.

Several climate-sensitive economic sectors need to anticipate and better prepare for climate impacts through vulnerability assessments. Turkey needs to continue to increase efficiency of its massive water use in agriculture (e.g. by modernising the irrigation network) to increase resilience to drought. There is also a need to further integrate adaptation in infrastructure planning as climate change and extreme weather events can alter demand patterns and cause damage to energy, waste and transport infrastructure. Turkey is making progress on integrated coastal zone plans. These plans are important to address the risk of erosion, flooding, sea level rise and saltwater intrusion, aggravated by intensive economic activity. It is equally important to better mainstream adaptation in tourism, which accounts for about 4% of GDP and 10% of employment.

To date, response to natural disasters has largely been in reaction to earthquakes. With increasing climate-related extreme weather events (heat waves, floods, droughts), Turkey is shifting towards a disaster risk management approach to anticipate, reduce and address these events. The development of early warning systems to protect human lives from extreme weather events needs to continue. The Disaster and Emergency Management Authority has presented the Climate Change and Disasters Related to Climate Change Roadmap (2014-23) whose implementation needs to be monitored.

Recommendations on climate change

Policy framework and international commitments

Ratify the Paris Agreement and strengthen the INDC; establish a long-term (2050) low-emission and resilient development strategy that integrates climate and energy objectives.

Formulate a sector-by-sector action plan to 2030 with emissions reduction goals for mitigation and updated adaptation objectives, prioritised short-term actions aligned with 2050 goals; identify resource requirements and financing for implementation.

Monitoring and evaluation

Establish a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation system with clear roles and responsibilities overseen by the Co-ordination Board on Climate Change and Air Management; identify and use suitable performance indicators for each action; prepare regular reports and make them available to the public; regularly monitor and evaluate the implementation of all other climate-related policy documents (e.g. Drought Management Plans, the NREAP and the NEEAP).

Mitigation

Reduce carbon intensity of power and heat generation by increasing energy efficiency and renewable energy use (e.g. through co-firing of biomass) and by closing or renovating old coal-fired power plants; ensure that new coal plants are efficient, equipped with carbon capture and storage or can be retrofitted with it.

Promote clean transport by encouraging a modal shift to public transportation, cleaner freight and passenger vehicles (e.g. with taxes and regulatory instruments).

Set priority actions and quantitative energy efficiency targets by sector, support measures across sectors and regularly monitor and evaluate their cost-effectiveness as part of the implementation of the NEEAP.

Increase the short-term renewable energy target and set longer-term targets; clarify subsector targets and ensure consistency across targets and objectives; encourage the use of renewable energy sources in transport.

Adaptation

Strengthen mainstreaming of adaptation into relevant policy areas (e.g. key economic sectors, ecosystems, infrastructure) and in policy and project appraisal.

Further improve scientific knowledge on climate change vulnerability and impacts, including social aspects, to make an economic case for action; continue to develop early warning systems for extreme weather events; design an online platform for climate data that is user-friendly for policy makers and other stakeholders.

Support local authorities in preparing their climate change adaptation plans by building technical capacity and improving access to geographically disaggregated data at the local level; ensure that adaptation plans are supported by robust and realistic financing strategies.

5. Urban wastewater management

Turkey has made significant progress in urban wastewater management as a result of continuous investments of national and international funds, increase in institutional capacity, and legal and institutional reforms (including amalgamation of small municipalities). In particular, access to wastewater collection network and treatment facilities has increased, but remains among the lowest in the OECD. Approximately 14% of residential wastewater is discharged without treatment, and 38% of industrial wastewater is not treated before being discharged into water bodies (TurkStat, 2018b). Water quality monitoring has improved considerably since the 2008 EPR, and similar progress is needed in the wastewater sector.

At the same time, strategic documents focus on investment in line with the stringent national effluent standards that in some aspects go beyond EU requirements. This may carry risks of excessive capital costs, technology lock-in, a knock-on increase of operation and maintenance (O&M) costs and, ultimately, rising consumer tariffs.

Population growth, agricultural activities and energy production will increase pressure on water quantity and quality. Climate change will add more uncertainty to water availability and needs. In this context, Turkey is committed to further improving planning and monitoring at the river basin level to target and manage priority water-related risks.

Institutional and regulatory framework

Two ministries regulate and monitor performance of water supply and sanitation (WSS) services. The MEU determines treatment standards for wastewater treatment plants, and issues and enforces discharge permits. The MAF develops policies for protection and sustainable use of water resources, regulates water supply and co‑ordinates national water management. Each ministry regulates and monitors performance of its respective aspects of WSS services.

Turkey is committed to strengthening the national Water Management Co‑ordination Board and similar lower-level boards, created in 2012 to foster co-operation across government bodies and with other stakeholders, including water users (Section 2). A successful transition towards more efficient wastewater collection and treatment requires engagement with stakeholders at the national, basin and local levels, to set realistic levels of ambition, priorities and financing strategies.

The forthcoming Water Law is expected to clarify roles and responsibilities of different government authorities, as well as enable public participation in water management practices. Turkey is moving towards regulating and monitoring water pollutants based on conditions of receiving water bodies at the basin level. This is a key issue to be addressed in RBMPs, as it will drive requirements for additional effluent treatment.

Strategic planning

Turkey has started to integrate water-related SDGs into planning documents (Section 3). The government has invested considerable resources in recent years in preparing RBMPs, as well as drought and flood management plans. Consistent with the principles of the EU Water Framework Directive, Turkey has identified 25 hydrological basins, defined “sensitive water bodies, urban-sensitive areas and nitrate-sensitive areas” within them, and completed 25 river basin protection action plans.

Several ministries have drafted strategies to support WSS development in their respective areas. The MEU has prioritised investments in wastewater and sanitation services. The MAF prepared a Drinking Water Action Plan for settlements. The National Water Information System gathers all water-related data to support integrated planning and decision making in the water sector.

Turkey has several strategies, plans and programmes that deal with water resource management. However, an overall national water strategy would help to reflect progress to date, consolidate the efforts and streamline criteria of allocating funding for infrastructure development. At the local level, priorities set through river basin planning need to be reflected in urban development plans.

Investment and financing

Turkey’s Environmental Law requires polluters to contribute to all investment, operation and maintenance in proportion to their pollution load and wastewater flow rate. In line with this principle, all wastewater infrastructure administrations have established full cost-recovery wastewater tariffs.

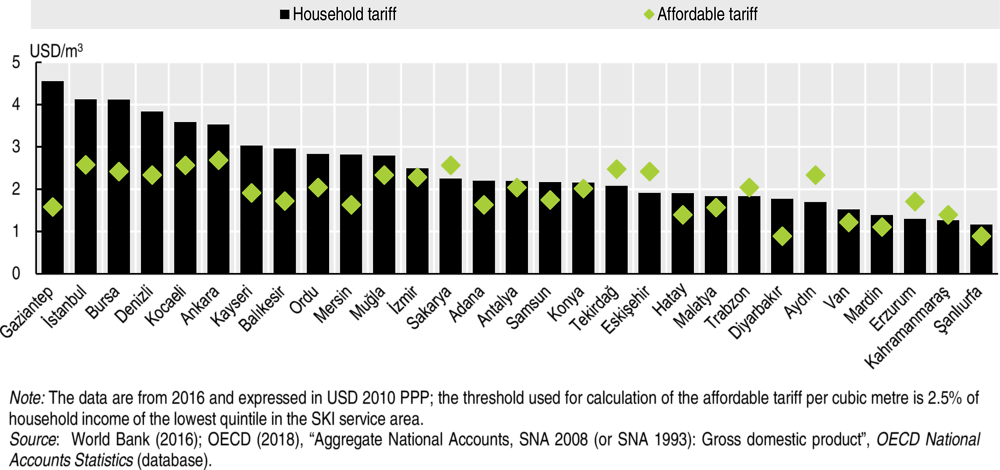

Turkey has identified water bodies sensitive to eutrophication. It has transposed relevant provisions of the EU Urban Wastewater Treatment and Nitrates Directives into national legislation. However, in some cases treatment requirements may go beyond what is necessary to achieve quality standards of receiving water bodies. This may increase investment costs and have lasting consequences for O&M costs. For example, additional nutrient removal can increase operating costs by more than 40% and generate 30% more sludge. These considerations could lead Turkey to review its designation of sensitive areas. Only a small number of Turkish water utilities have potential for tariff increase to finance new investments without harming the poorest households (Figure 4). Affordability of wastewater services should be monitored in view of potential social implications.

Figure 4. Household water and wastewater tariffs exceed affordability limits in many provinces

The MEU has prepared regulations and guidelines for determination of wastewater tariffs. Indeed, most utilities will have to implement cost efficiency measures to accommodate growing capital costs in tariffs. Turkey may benefit from prioritisation and stepwise design and construction of wastewater infrastructure. This approach is applied by a number of EU Member States, including Croatia and Bulgaria.

The MAF has taken first steps to establish a benchmarking system for the provision of WSS services, including the structure and level of tariffs, and quality of service. These efforts are worth pursuing and expanding. Such a system should allow monitoring of actual performance of WSS facilities and costs of their services. This is critical for evaluating the impact of the sector’s policies and programmes, and ensuring public accountability for tariffs and public investments.

Innovation

A number of innovative practices to drive progress in the water and wastewater sector, such as wastewater reuse and sludge digestion, are being explored in Turkey. They combine both technical and non-technical innovations and are applied at different scales. Innovative technical practices have potential to reduce capital and operational costs and contribute to water and energy security. For example, biogas production through sludge digestion can help meet wastewater utilities’ energy needs. Looking for new management solutions, Turkey plans to extend PPPs, already implemented in other sectors (Section 3), to construction and operation of wastewater treatment plants.

Recommendations on urban wastewater management

Institutional and regulatory framework

Continue to strengthen the institutional framework by clarifying roles and responsibilities in the water sector.

Adjust wastewater treatment standards based on consideration of carrying capacity of receiving water bodies and robust cost-benefit analysis to avoid excessive capital and operational infrastructure costs; consider phased implementation of treatment requirements.

Consider consolidating responsibilities for regulating economic aspects of WSS service provision within one government body.

Strategic planning

Develop a single water strategy that would cover all water management aspects at the national level and be aligned with economic development and urban planning objectives.

Harmonise national and municipal planning of water infrastructure development and management; use river basin planning to determine the level of ambition, priorities and financing needs.

Investment and financing

Develop and endorse robust and realistic financing strategies that cover O&M costs of existing assets, new investments and further developments identified in RBMPs.

Issue national guidelines for improving WSS services; encourage better utility O&M performance to facilitate financing of further investments and O&M costs and keep tariffs affordable.

Innovation

Continue aggregating small utilities to generate economies of scale and make the best use of larger infrastructure; introduce other new business models for water and wastewater utilities.

Continue expanding the role of the private sector to improve performance and leverage private financing, particularly from domestic sources.

References

EC (2016), Turkey 2016 Report. Communication on EU Enlargement Policy, European Commission, Brussels, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/sites/near/files/pdf/key_documents/2016/20161109_report_turkey.pdf.

Ecofys (2016), “Roadmap for the consideration of establishment and operation of a greenhouse gas emissions trading system in Turkey”, report commissioned by the Ministry of Environment and Urbanisation, Ankara, www.ecofys.com/en/publications/roadmap-for-an-emissions-trading-system-in-turkey/.

Garanti and PwC (2017), Capital Projects and Infrastructure Spending in Turkey: Outlook to 2023, Garanti BBVA Group and PwC Turkey, January 2017, www.pwc.com.tr/en/hizmetlerimiz/danismanlik/sirket-birlesme-ve-satin-almalari/yayinlar/turkiye-altyapi-yatirim-harcamalari-raporu.html.

IEA (2016), Energy Policies of IEA Countries: Turkey 2016, Energy Policies of IEA Countries, International Energy Agency, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264266698-en.

IEA (2018), “Emissions per kWh of electricity and heat output”, IEA CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion Statistics (database), International Energy Agency, https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00432-en (accessed 2 September 2018).

IPCC (2014), Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Pachauri, R.K. and L.A. Meyer (eds.), www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar5/syr/AR5_SYR_FINAL_SPM.pdf.

Janssen, R. (2016), “Turkey: Industrial energy efficiency strategy”, 17 October 2016, Energy Efficiency in Industrial Processes, Brussels, www.ee-ip.org/articles/detailed/7cc969ab93f80c76a54ecc339c544ae9/turkey-industrial-energy-efficiency-strategy/.

MENR (2018), Energy Efficiency Action Plan (2017-23), Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources, Ankara, www.yegm.gov.tr/document/20180102M1_2018_eng.pdf.

MEU (2016a), Environmental Indicators 2015, Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, Ankara.

MEU (2016b), Turkey’s Sixth National Communication under the UNFCCC, Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, Ankara.

MEU (2016c), EU Integrated Environmental Approximation Strategy 2016-2023, Ministry of Environment and Urbanization, Ankara.

OECD (2018a), Effective Carbon Rates 2018: Pricing Carbon Emissions Through Taxes and Emissions Trading, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264305304-en.

OECD (2018b), OECD Analysis of Budgetary Support and Tax Expenditures, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.oecd.org/site/tadffss/data/.

OECD (2018c), OECD Economic Surveys: Turkey 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-tur-2018-en.

OECD (2018d), “Creditor reporting system: Aid activities”, OECD International Development Statistics (database), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/data-00061-en (accessed 30 October 2018).

OECD (2016), “Innovation, agricultural productivity and sustainability in Turkey”, OECD Food and Agricultural Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264261198-en.

REN21 (2018), Renewables 2018. Global Status Report, Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century, Paris, www.ren21.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/17-8652_GSR2018_FullReport_web_final_.pdf.

TomTom (2018), “TomTom Traffic Index: Measuring Congestion Worldwide” website, www.tomtom.com/en_gb/trafficindex/list?citySize=LARGE&continent=ALL&country=ALL (accessed 26 February 2018).

TSMS (2018), State of the Climate in Turkey in 2017, Turkish State Meteorological Service, Ankara, www.emcc.mgm.gov.tr/files/State_of_the_Climate_in_Turkey_in_2017.pdf.

TurkStat (2018a), Transportation Statistics: Number of Road Motor Vehicles by Kind of Fuel Used (database), Turkish Statistical Institute, www.turkstat.gov.tr/PreTablo.do?alt_id=1051 (accessed 11 June 2018).

TurkStat (2018b), Sectoral Water and Wastewater Statistics (database), Turkish Statistical Institute, http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/PreTablo.do?alt_id=1019 (accessed 16 October 2018).

UNFCCC (2016), Report of the Technical Review of the Sixth National Communication of Turkey, UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, New York.

Annex 1.A. Actions taken to implement selected recommendations of the 2008 OECD Environmental Performance Review of Turkey

|

Recommendations |

Actions taken |

|---|---|

|

Chapter 1. Environmental performance: Trends and recent developments |

|

|

Continue, and strengthen, efforts to improve energy efficiency in the energy, transport, industry, residential and services sectors, to capture related multiple benefits, including those of reduced air pollution and reduced greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. |

Turkey adopted a National Energy Efficiency Action Plan in 2017, building on the 2012 Energy Efficiency Strategy. The plan does not contain sectoral targets or indicators to measure progress. |

|

Continue to promote the use of cleaner fuels for motor vehicles and for residential uses. |

Motor vehicles produced after 1 January 2018 are subject to the latest EU emission limits. Coal will be gradually replaced by natural gas in residential heating. |

|

Strengthen efforts to integrate air quality concerns into transport policy, including modal shift from road to public transport (e.g. railways), with appropriate cost-benefit analysis of investments and co-operation among levels of government and relevant sectors; extend the use of cleaner motor vehicles. |

The government is implementing a scrapping programme for old vehicles and plans to stimulate domestic demand through investments in charging infrastructure and incentives for clean vehicle use. Tram and train routes are expanding, but private road vehicles largely dominate. |

|

Continue and strengthen efforts to improve the information base for air management, including additional pollutants in the air emission inventories; extending ambient air quality monitoring; adopting and implementing the draft Regulation on Air Quality Evaluation. |

The Air Quality Assessment and Management regulation (2008) is being revised to harmonise it with the EU Clean Air for Europe Directive. Ambient standards for pollutants will become more stringent by 2024 (no timeframe yet for PM2.5). New air quality monitoring stations meet EU requirements. |

|

Reduce water pollution from agriculture (e.g. identification of nutrient vulnerable zones, action plans to address pollution, codes of good agriculture practices, effective inspection and enforcement). |

A Regulation on the Protection of Waters against Agricultural Nitrate Pollution was adopted in 2014. Nitrate pollution is monitored. Support payments are made for environmentally friendly agricultural techniques. |

|

Continue efforts to promote water monitoring, promote the analysis of health and economic impacts of water pollution. |

A Regulation on Monitoring of Surface Water and Groundwater was adopted in 2014. Monitoring programmes have been prepared for several river basins. |

|

Prepare and adopt a framework law to cover all areas of nature and biodiversity. |

A Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan for 2018-28 is under preparation. Framework legislation on biodiversity protection has not yet been adopted. Turkey has not submitted national targets under the Convention on Biological Diversity. |

|

Create protected areas so as to reach the 10% domestic target by 2010; establish them in an interconnected network; complete, adopt and implement management plans for all protected areas. |

The share of protected areas has increased and reached 9%, which is still far from the Aichi targets. The shares of terrestrial and marine protected areas have not been made public. |

|

Continue afforestation and sustainable forestry efforts; continue and expand all erosion combating efforts. |

Turkey expanded natural and semi-natural forest areas and plans to further increase forest cover by 1.3 million hectares by 2023. Turkey is among the OECD member countries with the lowest forestry use intensity. |

|

Finalise the inventory of endangered species; publish the corresponding Red List; improve statistics and indicators on biodiversity. |

A nationwide biodiversity monitoring and inventory project is to be completed by 2019. Good inventory data have been collected on plants, but not on animal and fungi species. No Red List has been published; Turkey provides IUCN-compatible data only to the European Environment Agency. |

|

Chapter 2. Environmental governance and management |

|

|