This chapter introduces deforestation and forest degradation in the context of global supply chains. It presents the magnitude of the problem and its origins in commodity production and sourcing, along with the development challenges that can contribute to deforestation in different contexts.

OECD-FAO Business Handbook on Deforestation and Due Diligence in Agricultural Supply Chains

Forests and deforestation

Abstract

Healthy forests are vital to the three pillars of sustainable development: economic, social and environmental. Continued business growth and jobs in the agricultural sector, and global food security, depend on forests. Forest ecosystems are the largest terrestrial carbon sink, critical to meeting climate goals; they also regulate rainfall and water cycles and help to maintain stable local environments, which are essential to supporting livelihoods and sustainable agricultural production. Approximately 1.6 billion people depend on forests for their livelihood, including about 70 million Indigenous Peoples. Forests contain more than 60 000 different tree species and provide habitats for a large majority of animal species. (FAO, 2020[3]; FAO and UNEP, 2020[5]).

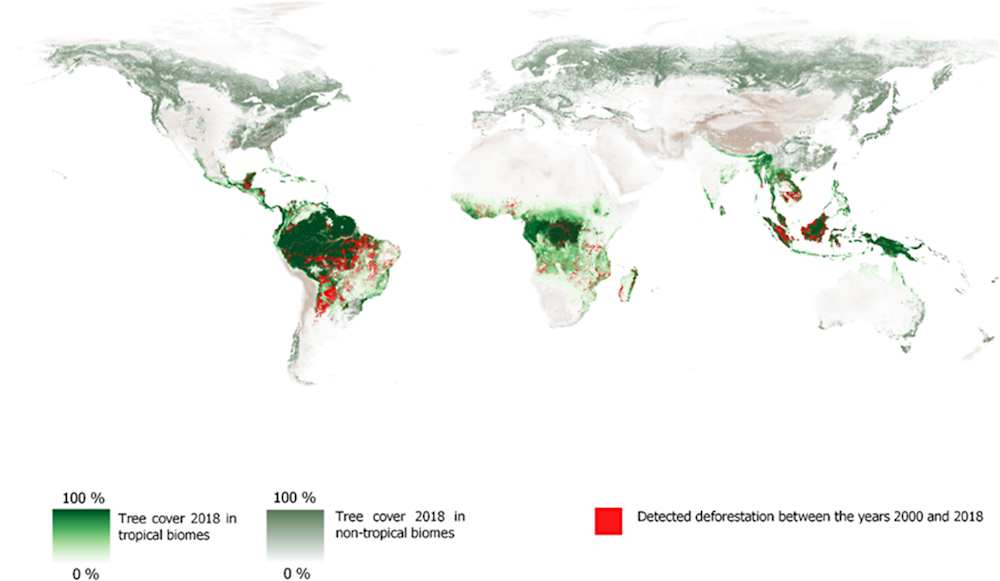

In 2020, 31% of the world’s land area – 4 billion hectares – was covered by forest. Since 1990 an estimated 420 million hectares of forests have been lost through deforestation (FAO, 2020[3]). From 2015 to 2020, the rate of deforestation was estimated at 10 million hectares per year, though afforestation and reforestation has supported forest recovery in some parts of the world (FAO, 2020[3]). Loss of forests, particularly natural forest, was especially high in the tropics over this period (see Figure 1).

Forest degradation is a result of unsustainable logging operations, wood fuel extraction, shifting agriculture, grazing or fires and affects forest ecosystems in tropical, temperate and boreal biomes alike. In all these cases the forest retains the capacity to regrow, but these activities typically reduce forest cover faster than it naturally recovers and affect the diversity of species hosted in those forests (FAO and UNEP, 2020[5]). While forest degradation is difficult to measure, studies suggest that it accounts for about one‑third of the overall impact of tree cover loss, measured in terms of carbon emissions (Federici, 2015[6]).

Figure 1. Deforestation, 2000‑2018

Source: FAO (2022[7]), FRA 2020 Remote Sensing Survey, https://www.fao.org/forest-resources-assessment/remote-sensing/fra-2020-remote-sensing-survey/en/

Impacts of agricultural production on forests

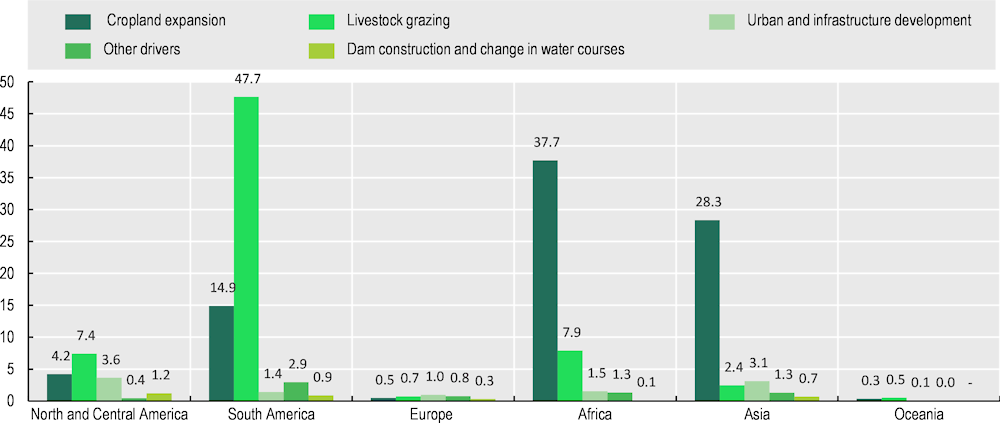

Agricultural production can both drive deforestation and be negatively impacted by deforestation. FAO’s global Remote Sensing Survey of forest resources estimates that from 2000‑18 nearly 90% of global deforestation was a result of agricultural expansion, including 52% from cropland expansion and 38% from livestock grazing (FAO, 2021[8]). Figure 2 illustrates the main drivers of deforestation by region. Similarly, deforestation, coupled with climate change, can also greatly impact agricultural production, which can in turn have significant impacts on food availability and demand.1

Figure 2. Main deforestation drivers across the world’s regions

Source: FAO (2022[7]), FRA 2020 Remote Sensing Survey, https://www.fao.org/forest-resources-assessment/remote-sensing/fra-2020-remote-sensing-survey/en/

A range of factors underpin the link between deforestation and agricultural production (Geist, 2002[9]). While growth and development have raised millions out of poverty, they have also increased demand for food and led to changes in lifestyles and diets as people consume lower volumes of staple foods and more meat, dairy products, fruit and vegetables, and processed foods. These trends are projected to continue (OECD-FAO, 2021[10]) as the global population is anticipated to reach 9.7 billion people by 2050 (UN, 2019[11]). Taking dietary changes and other factors into account, this implies a growth in food demand of 35‑56% (Van Dijk, 2021[12]), potentially increasing demand for land and pressure on forests.

The liberalisation of trade and business has encouraged the growth of global supply chains; an estimated one‐third of agri-food exports are now traded within global value chains (FAO, 2022[13]). While the act of deforestation takes place at specific locations upstream in the supply chain, downstream firms and suppliers play a critical role in ensuring that the risk of deforestation is addressed within the commodity supply chains from which they source.

It should be noted that a significant proportion of the clearance of forests for agriculture has been illegal. A comprehensive survey published in 2021 estimated that 69% of the conversion of tropical forests for agriculture that had taken place between 2013 and 2019 had been conducted in violation of national laws and regulations (Forest Trends, 2021[14]). Illegal logging (for timber) remains a serious concern in many countries, with an estimated value in international trade at between USD 50‑150 billion a year (World Bank, 2019[15]).

Agricultural commodities and deforestation

Based on studies of the drivers discussed above, deforestation linked to agriculture has often been associated with a select group of commodities (Pendrill, 2019[16]). However, business, demand and trade can oscillate over time. Neither supply nor demand is fixed, and growth in demand for new agricultural products can drive deforestation in other contexts, including in temperate climates.

International attention is commonly given to the impacts on forests of certain commodities which have seen increased production and export over recent decades, often dependent on expanding land for agricultural use by reducing forest cover. Commodities cultivated or grown in an area after it is deforested are considered as “direct drivers” of deforestation. It is the manner in which these commodities are produced, not the commodities themselves, however, that links them to deforestation.

A small group of commodities have received wider attention because recently deforested lands are often used for their production. These include beef, dairy products and leather from cattle, soybeans, palm oil, cocoa, coffee, wood and rubber. Consequently, public and private responses and multi-stakeholder initiatives have tended to adopt commodity-specific approaches in their efforts towards more sustainable production models, respecting forests. Examples include the Amazon Soy Moratorium signed in 2006 where 90% of companies in the Brazilian soy market committed to avoiding the purchase of soy grown on recently deforested areas in the Brazilian Amazon. Likewise, the governments of Côte d’Ivoire and Ghana and 35 leading cocoa and chocolate companies have joined together in the Forest and Cocoa Initiative to eliminate cocoa related deforestation and restore forest areas.

Global initiatives on deforestation

Many efforts are being made to decouple commodity production from deforestation. While meeting international targets associated with deforestation, particularly those adopted before 2020 (see Table 1) have proved challenging, they have stimulated action by a wide range of companies producing, trading and using commodities associated with deforestation. Commitments to eliminate or reduce deforestation in corporate supply chains have become common in companies trading in and using timber, palm oil and cocoa; they are less common for other commodities. An analysis of 675 companies in 2021 disclosing forest risk in their supply chains to CDP found that 66% possessed a policy related to deforestation, while 38% had a general or commodity-specific company-wide no-deforestation / conversion policy (CDP/AFI, 2022[17]).

Table 1 provides examples of the wide range of international initiatives on deforestation associated with agricultural and timber supply chains since 2010;2 these include initiatives such as soft law, SDGs, private sector initiatives, as well as multi-stakeholder initiatives.

Table 1. Examples of international initiatives on deforestation

|

Date |

Organisation / Initiative |

Commitments |

|---|---|---|

|

2008 through 2015 |

UN Framework Convention on Climate Change – REDD, then REDD+, Framework |

Guide activities in the forest sector that reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, as well as the sustainable management of forests and the conservation and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries. |

|

2010 |

Consumer Goods Forum (global industry network of retailers, manufacturers and service providers) |

Zero net deforestation in membership’s supply chains by 2020 in key commodities: soy, palm oil, timber / paper and pulp, beef. |

|

2012 |

Tropical Forest Alliance (global partnership of governments, companies, civil society, Indigenous Peoples, local communities, UN agencies) |

Reduction in tropical deforestation associated with the sourcing of commodities such as palm oil, soy, cattle products and paper and pulp. Promotes and supports regional multi-stakeholder initiatives. |

|

2014 |

New York Declaration on Forests (signatories now include over 200 national and local governments, companies, and civil society, community and Indigenous Peoples’ organisations) |

At least halve the rate of loss of natural forests globally by 2020, strive to end natural forest loss by 2030; support private‑sector goal of eliminating deforestation from production of agricultural commodities by no later than 2020; significantly reduce deforestation derived from other economic sectors by 2020. |

|

2015 |

UN Sustainable Development Goals |

SDG 15.2: “By 2020, promote the implementation of sustainable management of all types of forests, halt deforestation, restore degraded forests and substantially increase afforestation and reforestation globally.” (Also SDG 12.6: “Encourage companies, especially large and transnational companies, to adopt sustainable practices and to integrate sustainability information into their reporting cycle.”) |

|

2020 |

Consumer Goods Forum Forest-Positive Coalition of Action |

Coalition of major companies aiming to support deforestation- and conversion-free enterprises through multi-stakeholder, integrated land use initiatives in key production landscapes. Commodity-specific roadmaps for action for soy, palm oil, cattle and pulp and paper. |

|

2021 |

Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use (signed by 141 countries at the 26th UN Climate Change Conference [COP26]) |

“Work collectively to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030 while delivering sustainable development and promoting an inclusive rural transformation”. Specific commitments include to: “facilitate trade and development policies, internationally and domestically, that promote sustainable development, and sustainable commodity production and consumption, that work to countries’ mutual benefit, and that do not drive deforestation and land degradation”. |

|

2021 |

Forest, Agriculture and Commodity Trade (FACT) Dialogue Roadmap for Action (statement by 27 governments and EU (representing largest producers and consumers of internationally traded agricultural commodities) at COP26) |

Aims to promote sustainable development and trade of agricultural commodities while protecting and sustainably managing forests and other critical ecosystems; Includes indicative actions on trade and market development; smallholder support; traceability and transparency; and research, development and innovation. |

A number of consumer countries have seen the emergence of initiatives aimed at ensuring that the entire national market is supplied with certified sustainable commodities – particularly for palm oil and cocoa – by a target date; sometimes these voluntary initiatives include governments too. Similar alliances have developed in several producer countries, such as the Zero-Deforestation Agreement on Palm Oil in Colombia. A number of producer countries have also developed their own national standards and certification schemes for specific commodities; examples include the Indonesian and Malaysian Sustainable Palm Oil standards and the African Standard for Sustainable Cocoa.

Recent years have also seen the emergence and uptake of commodity-focused multi-stakeholder roundtables and engagement platforms for collective action – such as the Africa Sustainable Commodities Initiative – and voluntary sustainability standards and associated certification schemes (see Annex A). Several financial institutions have adopted commitments not to provide finance for activities associated with deforestation.3

Legislation on deforestation and risk-based due diligence

In response to rising concerns over climate change and deforestation, some governments are introducing obligations for enterprises to conduct due diligence to address a range of risks in their operations and supply chains, including deforestation. These obligations complement the initiatives mentioned above and include:

General corporate obligations of due diligence, applying to an enterprise’s entire operations and supply chains, not specific to any sector or product, and not linked to placing products on the market.

Requirement for due diligence to be undertaken with regard to particular criteria (e.g. legal production, or zero-deforestation) before specified products can be placed on the market, imported or exported.

The implementation of risk-based due diligence as described in this Handbook, according to the OECD-FAO Guidance may support enterprises to meet such obligations.4

Notes

← 1. The OECD FAO Agricultural Outlook 2022‑31 illustrates the growing need to promote sustainable agricultural production, including adapting to different region-specific contexts to balance food production with other crops and the conservation of natural resources (OECD-FAO, 2021[10]).

← 2. In addition to these global initiatives, many regional and national initiatives exist to combat deforestation in agricultural supply chains.

← 3. See for example the Financial Sector Commitment on Eliminating Commodity-driven Deforestation announced at COP26 (UN, n.d.[23]) while at COP 27 countries in the Forest and Climate Leaders’ Partnership promised to hold each other accountable for a pledge to end deforestation by 2030. https://www.euronews.com/green/2022/11/07/cop27-more-than-25-countries-band-together-to-keep-deforestation-pledges-made-in-glasgow

← 4. See the background note on Translating a risk-based due diligence approach into law for further information. http://mneguidelines.oecd.org/translating-a-risk-based-due-diligence-approach-into-law.pdf