This chapter discusses Indonesia’s progress in greening its economy on the path to sustainable development. It examines the policy and institutional framework for sustainable growth, then reviews the use of tax policy to pursue environmental objectives and progress in removing subsidies that can encourage environmentally harmful activities. The chapter also analyses public and private investment in environment-related infrastructure, such as that for water and sanitation, waste, energy and transport, and reviews promotion of environmental technology and green innovation as a source of economic growth and jobs. The role of development co‑operation is also discussed.

OECD Green Growth Policy Review of Indonesia 2019

Chapter 2. Towards green growth

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

2.1. Introduction

Following the economic downturn of the 1997‑98 Asian financial crisis, Indonesia enjoyed impressive economic growth, supported by a commodities boom and strong domestic demand. Gross domestic product (GDP) grew 5.3% per year, on average, from the turn of the century, helping the country significantly reduce poverty and raise living standards. Natural resources serve the country well, accounting for more than 20% of GDP and 50% of exports in recent years (Chapter 1). Indonesia’s exceptional natural assets also attract a growing number of tourists.

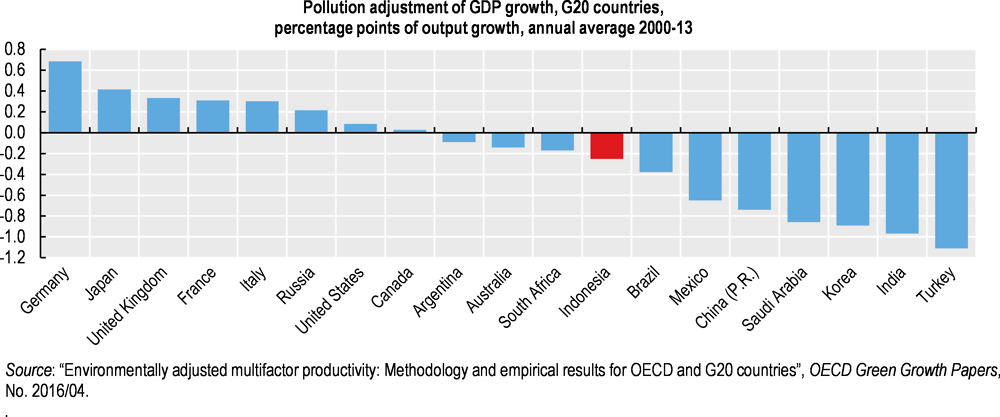

Indonesia expresses a strong commitment to green growth. However, conflicting sectoral development goals and difficulties implementing and enforcing environmental legislation mean pressures on the natural asset base have continued to increase (Chapter 1). OECD analysis shows that, if pollution had been accounted for, GDP growth would have been 0.3 percentage points lower per year (Figure 2.1). If the country does not transition to a greener growth model, GDP could be reduced by up to 7% per year by 2050, according to government estimates (MoF, 2015a). About a third of expected losses and damage are related to degradation of natural resources and ecosystem services, while the remainder relates to the impact of climate change. The poorest will be hit hardest by climate change, as they disproportionately rely on healthy ecosystems for their livelihoods and well-being. For example, forests and other ecosystems are estimated to account for 75% of GDP among rural communities (TEEB, 2010).

This chapter discusses Indonesia’s progress and remaining challenges in greening its economy. There are many opportunities to enhance both economic development and environmental sustainability. Seizing these will require better policy alignment, valuation of ecosystem services in economic planning and stronger use of market-based instruments. Reforming taxes on energy use, transport and natural resource extraction would help address environmental degradation cost-effectively while raising revenue for infrastructure and social spending. Better law enforcement and more cost-reflective pricing would boost investment in environment-related infrastructure, goods and services. Targeted support can alleviate the adverse impact of such reforms on poor and vulnerable populations.

Figure 2.1. Economic growth would be lower if pollution were accounted for

2.2. The policy and institutional framework for green growth

The principles of sustainable development and “a good and healthy environment as a basic human right” were added to Indonesia’s 1945 Constitution in 2002. This provides the basis for integrating green growth into the country’s development agenda. Indonesia has been active in international environmental co‑operation and committed to implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) adopted in 2015 as part of the UN 2030 Agenda, as well as its Nationally Determined Contribution adopted in the framework of the 2015 Paris Agreement.1

Sustainable development and green growth objectives are integrated in its well-established national development planning framework. This framework is based on long- and medium‑term national development plans that provide the basis for sector and subnational strategic plans as well as annual work plans and budgets.2 The 2005‑25 National Long-Term Development Plan provides a “pro-poor, pro-jobs, pro-growth and pro-environment” vision for the country’s development. The 2015-19 National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN), now in its third period, contains objectives and targets to improve environmental quality and acknowledges the need to manage natural resources sustainably. It integrates most of the SDG targets as well as the country’s climate change mitigation and adaptation targets (Chapter 1). Green growth principles and objectives have been mainstreamed into several provincial plans and strategies.

Despite these efforts, the national development planning architecture has not added up to a coherent policy framework for green growth. Sector plans and policies are not always well aligned with low-carbon or broader environmental and sustainable development goals, reflecting the precedence that economic and social development objectives tend to take over sustainability aspirations. The 2014 National Energy Policy, for example, sets a target of minimising oil consumption while increasing the share of renewable energy sources to 23% of total energy supply by 2025. Yet, at the same time, the policy aims to increase coal’s share to 30% – doubling its use in absolute terms (compared to 2015). This risks locking in high-carbon infrastructure on a wide scale, increasing the level of stranded assets and the overall cost of transitioning to a low-carbon economy (OECD, 2017a). It could also jeopardise the country’s efforts to reach its climate change mitigation objectives and will increase local air pollution. Similarly, rising production and export targets for oil palm – expansion of which has been a major driver of deforestation and peatland drainage (Chapter 3) – risk offsetting efforts to reduce deforestation and associated ecosystem degradation and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

The use of environmental impact assessment (EIA) and strategic environmental assessment (SEA), two key instruments to mainstream environmental considerations into sector policies, plans and projects, has improved in recent years. SEA is increasingly conducted for spatial plans at the provincial and local levels, and more recently for some national and sector policies. An EIA is required to obtain any sector-specific business licence for activities with a potential environmental impact. However, lack of data, limited capacity, weaknesses in transparency and public engagement, and insufficient monitoring and follow-up hamper the instruments’ effectiveness (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. Mainstreaming the environment into policies, plans and projects: A capacity challenge

Strategic environmental assessment

SEA began to be applied in the early 2000s and became a legal requirement in 2009. Law No. 32/2009 on Environmental Protection and Management requires SEA to be conducted for all development and spatial plans as well as any policies, plans or programmes with a potentially significant environmental impact or risk. SEA should include consideration of alternatives and assessment of the environment’s carrying capacity and cumulative effects, with particular emphasis on vulnerability to climate change and biodiversity. Government Regulation No. 46/2016 expanded the use of SEA to marine, coastal and small island zoning plans and provided a basis for a common approach to SEA.

Since 2009, over 100 SEA studies have been conducted, mostly for provincial spatial plans. There are also some examples of SEA for national sector policies (e.g. for the oil palm, coal and aquaculture sectors) as well as the Masterplan for the Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia’s Economic Development 2011‑25 (DANIDA, 2018). At the local (district) level, spatial plans rarely undergo SEA.

Since SEA often starts quite late in the planning process, limited attention has been given to consideration of alternatives. Many SEA reports present long lists of detailed recommendations, making it difficult for decision makers to set priorities. Follow-up monitoring of these recommendations is almost never carried out (DANIDA, 2018). There is a serious need to strengthen technical capacity to perform SEA at the local level and increase stakeholder and public involvement. The government has developed guidance on SEA procedures and requirements, including for regional and national development plans, which may help improve its application.

Environmental impact assessment

EIA is required prior to securing sector-specific business licences (e.g. for mining exploitation, construction or plantation). Since the 2001 decentralisation reform, EIA has been primarily implemented at the local and provincial levels. If projects do not require an EIA, the operator must submit an Environmental Management and Monitoring Program (EMMP) document or a Statement of Ability to Manage and Monitor the Environment. EIA or EMMP approval results in the issuance of an environmental permit. However, the permits rarely contain limits on polluting activities, are valid indefinitely and are not subject to periodic review (Sano, 2016).

EIA documents are often of poor quality and overlook important potential environmental effects due to the low competence of accredited consultants who prepare them and the lack of data that should form the basis of the analysis (Sano, 2016). Indonesia’s National Human Rights Commission expressed concern in 2015 that EIA documents were frequently manipulated by project proponents (Nugraha, 2015). Capacity of local commissions that review EIA documents is generally low and technical guidelines for the documents’ development and review are often of poor quality. Many projects are approved without appropriate EIA, or even without an environmental permit. A positive development was a 2016 regulation introducing criminal sanctions for officials who approve a project without EIA and operators who lack an environmental permit. This helped decrease the number of activities without appropriate environmental authorisation. In 2018, a practice of issuing provisional business licences through an online platform before the EIA is completed was introduced, which compromises consideration of alternatives in the EIA process.

Effective implementation of the low-carbon development plan will require strong institutional co‑ordination, with a clear division of responsibilities at all government levels. As in many countries, the institutional framework for environmental management and green growth is complex, with many line ministries involved in policy implementation and sometimes unclear division of responsibilities. The Ministry of Environment and Forestry (MoEF) has the main responsibility for ensuring environmental protection and natural resource conservation and is the main focal point for climate change. But with environmental legislation being primarily sector-based, several other ministries have important responsibilities for green growth, including those for agriculture, energy and mineral resources, public works, industry, transport and finance. In addition, Indonesia’s devolved administrative system (Chapter 1) makes subnational governments important partners for the green growth transition.

The government has striven to ensure co‑ordination among ministries and agencies and between government levels on green growth policy formulation and implementation (e.g. by merging the environment and forestry ministries). However, it lacks sufficiently effective arrangements. Apart from issue-specific presidential instructions that prescribe roles for individual ministries and sometimes create interagency working groups, there is no formal operational mechanism to address the fragmentation of responsibilities. Environmental management, especially with respect to permitting and compliance assurance, thus often entails overlapping interests and institutional conflicts. National co‑ordinating councils on climate change and land use have been dissolved. The four co‑ordinating ministries3 working to harmonise policy planning across line ministries could play a more effective role in ensuring policy coherence between sectors and assigning clear responsibilities with regard to efforts to reach low-carbon-economy targets. The establishment of formal vertical co‑ordination mechanisms could help ensure more effective co‑ordination between the central, provincial and district/city authorities.

Indonesia would benefit from building a dedicated monitoring framework to follow progress towards green growth. The MoEF publishes annual reports on selected environmental issues (e.g. air quality, water quality), although a comprehensive State of the Environment report has not been published since 2014 (Chapter 1). Efforts are made to enhance knowledge on the state and flows of natural capital (Box 2.2). Over the medium term, a monitoring framework could go further by linking economic activity with environmental performance; it could also include indicators on policy effectiveness regarding environmental challenges and on value added and jobs created in green sectors. Systematic reporting on such parameters can help raise awareness of the low-carbon, green transition, build consensus on it and increase ownership of it.

Box 2.2. Indonesia is strengthening natural capital accounting

Indonesia has done natural capital accounting for more than 30 years. Furthermore, Government Regulation No. 46/2017 on Environmental Economic Instruments mandated central and local governments to provide data and information to develop natural capital accounts. Statistics Indonesia (BPS) began compilation of an integrated environmental and economic accounting system called Sisnerling in the early 1990s and now develops annual asset accounts for forest resources, minerals and energy in line with international System for Environmental-Economic Accounting (SEEA) standards. As in many countries, low data quality, data fragmentation across institutions, limited data harmonisation and insufficient inter-institutional co‑operation more generally hamper practical use of this information in decision making. BPS has suffered considerable human resource and technical capacity constraints in developing Sisnerling.

Since 2013, Indonesia has collaborated with the Wealth Accounting and the Valuation of Ecosystem Services (WAVES) global partnership to strengthen, expand and facilitate the use of natural capital accounting in policy making. As part of the partnership, a pilot land-use account was done for West Sumatra and a land cover account for West and East Kalimantan.

Source: WAVES, 2016; WAVES, 2018.

2.3. Greening the system of taxes, charges and prices

2.3.1. Environmentally related taxes: an overview

Indonesia has considerably improved its tax system over the past decade in respect to both revenue raised and administrative efficiency. However, its revenue/GDP and tax/GDP ratios, at 14% and 12%, respectively, remain low by comparison with countries at a similar income level. This has been attributed to factors including high informality levels, low tax compliance levels, widespread tax exemptions and narrow tax bases. Subnational governments raise only about 10% of total tax revenue directly, relying substantially on central government transfers to fund public services (OECD, 2018a).

Revenue from environmentally related taxes is low by international comparison.4 The OECD estimates that the revenue reached IDR 98 trillion in 2016 (USD 7 billion) (Table 2.1), or 0.8% of GDP. The bulk of it stems from vehicle taxation, whereas transport fuel taxes account for the greatest share in most countries. In 2010‑13, revenue increased by 43% (in real terms), faster than GDP (Figure 2.2), driven by sharp growth in the vehicle fleet and rising energy consumption in road transport. Revenue declined slightly thereafter with a slowdown in vehicle sales, though these picked up again in 2017.

Figure 2.2. There is room to increase energy tax revenue

The tax structure in energy use, transport and natural resource‑based activities aligns poorly with environmental objectives and the polluter-pays principle. Tax rates generally do not reflect the cost of environmental damage; industry and other sectors, such as agriculture, are exempt from various taxes and charges; and pollution (e.g. air emissions, wastewater discharge) and products causing pollution (e.g. fertilisers and pesticides) are not taxed at all. Indonesia applies taxes on natural resource use, but low rates and weak enforcement limit their impact on consumption and production. Charges and fees for public services, such as water and waste collection, are inconsistently applied and too low to stimulate efficient use or finance service provision.

As the OECD’s 2018 Economic Survey indicates, well-designed green fiscal reform could help Indonesia boost much‑needed tax revenue while reducing pollution and other environmental externalities in a cost-effective way (OECD, 2018a). Although Indonesia’s fiscal position is in good shape, due in part to energy subsidy reform (Section 2.4), social and infrastructure spending needs are large. Taxing “bads”, such as pollution, can raise revenue at a lower economic cost than taxing “goods”, such as labour and corporate income, if good use is made of the revenue raised (OECD, 2017b). Government Regulation No. 46/2017 on Environmental Economic Instruments may provide momentum to reconsider and expand the use of taxes for environmental purposes, as well as instruments such labelling, sustainable procurement, tradable permits, subsidies, environmental insurance and the Environmental Management Fund.

Table 2.1. Transport taxes account for the bulk of environmentally related tax revenue

Revenue from key environmentally related taxes, 2016

|

Details |

Levied by |

Revenue sharing |

Revenue (IDR billion) |

Share of environmentally related tax revenue |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Energy taxes |

|||||

|

Motor vehicle fuel tax |

5% of retail price, excl. VAT; 7% in some regions |

Province |

70% to local gov. |

16 537 |

17% |

|

Street lighting tax |

Up to 10% of electricity consumption (retail price, excl. VAT) |

District |

- |

10 404 |

11% |

|

Vehicle taxes |

|||||

|

Luxury goods sales tax on vehicles |

Up to 125% of vehicle factory price |

State |

n/a |

1 834 |

2% |

|

Vehicle registration tax |

10% of vehicle resale price |

Province |

30% to local gov. |

28 288 |

29% |

|

Vehicle ownership tax (annual) |

Based on weight, engine size and vehicle’s assessed value |

Province |

30% to local gov. |

35 816 |

36% |

|

Other environmentally related taxes |

|||||

|

Surface water tax |

10% of water consumption |

Province |

70% to local gov. |

563 |

1% |

|

Groundwater tax |

20% of water consumption |

District |

- |

605 |

1% |

|

Parking tax |

30% of parking fees |

District |

- |

976 |

1% |

|

Swallow’s nest tax |

n/a |

District |

- |

9 |

0% |

|

Forestry taxes, fees and charges |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

3757 |

4% |

|

Total |

98 791 |

100% |

Source: OECD compilation, based on state and local revenue statistics and country submission.

There is room both to use existing taxes more effectively and to introduce new taxes. Opportunities include expanding energy taxation (and introducing carbon pricing), redesigning vehicle taxation to encourage people to buy low-emission cars and use public transport, and increasing and better enforcing taxes related to natural resource use in the forestry and fishery sectors. Water extraction fees need better enforcing and could be expanded. Indonesia should also consider introducing taxes on pollution (e.g. waste and wastewater release) and/or on products causing pollution (e.g. fertilisers, pesticides).

Many countries have used green fiscal reform to make their tax system less distortive and more growth- and employment-friendly, including Norway, the United Kingdom, Germany and Portugal. To advance on such reform, Indonesia could consider establishing a committee that would bring together stakeholders such as the ministries of finance, environment and forest, energy and mineral resources, agriculture, and industry. Past attempts to reform existing taxes or introduce new ones have met strong resistance from industry, but difficulty co‑ordinating relevant ministries has also played a role. The establishment of a green fiscal reform committee could help in analysing options and economic, social and environmental consequences of introducing green taxes. In France, a green tax commission was instrumental in adopting a carbon tax.

2.3.2. Taxes on energy use and carbon pricing

Indonesia does not tax energy use at the national level, nor does it have an explicit carbon tax or a carbon emission trading system. Only two low-level energy taxes are applied: a regional motor vehicle fuel excise tax and a local street lighting tax, which effectively acts as an electricity consumption tax. Thus nearly all energy not used for road transport – i.e. the bulk of energy use – is untaxed. Revenue from energy taxes amounted to 0.2% of GDP in 2016, compared to 1.2% of GDP in OECD countries (OECD, 2018b).

The main tax on energy use is the automotive vehicle fuel tax, imposed on petrol and diesel used in road transport. It is applied throughout the country, but levied at the regional level, with regionally differentiated rates. Law No. 28/2009 capped the rate at 10% of the sales price, but a 2014 presidential decree lowered the top rate to 5% (with a premium of 2% allowed outside Java-Madura-Bali due to the higher distribution costs). Fuels other than petrol and diesel (including biofuels, natural gas and liquefied petroleum gas, or LPG), as well as fuels for off-road transport (e.g. in the agriculture and fishery sectors), are not subject to the tax. The tax is lower for diesel than for petrol, but the effective rate on CO2 emitted in combustion of both fuels is low by international comparison. For example, the tax translates to an average effective tax of EUR 7.6 per tonne of CO2 emitted from fuel consumption in transport, far below the external cost of transport-related energy use and much lower than effective tax rates in India (EUR 49/t CO2), China (EUR 70/t CO2) or South Africa (EUR 95/t CO2). Only Brazil and Russia apply lower excise taxes on energy use in road transport (OECD, 2018c). However, the government is revising the national regulation to enable subnational governments to increase the fuel tax rate. Efforts are also under way to reduce subsidies to transport fuels (Section 2.4.1) by using a more targeted mechanism.

The street lighting tax is a small levy imposed by district governments on households. It is collected by the state-owned electricity company, PLN, and transmitted to local governments. It effectively is a residential electricity tax. Part of the revenue is allocated to provision of street lighting. The maximum rate is set at 10% for general consumers and 3% for industry and for petroleum and natural gas production; for self-generated power the rate is 1.5% (Hakim, 2016). Public institutions are exempt from the tax. Attempts to increase the rate for industry have met strong opposition from businesses.

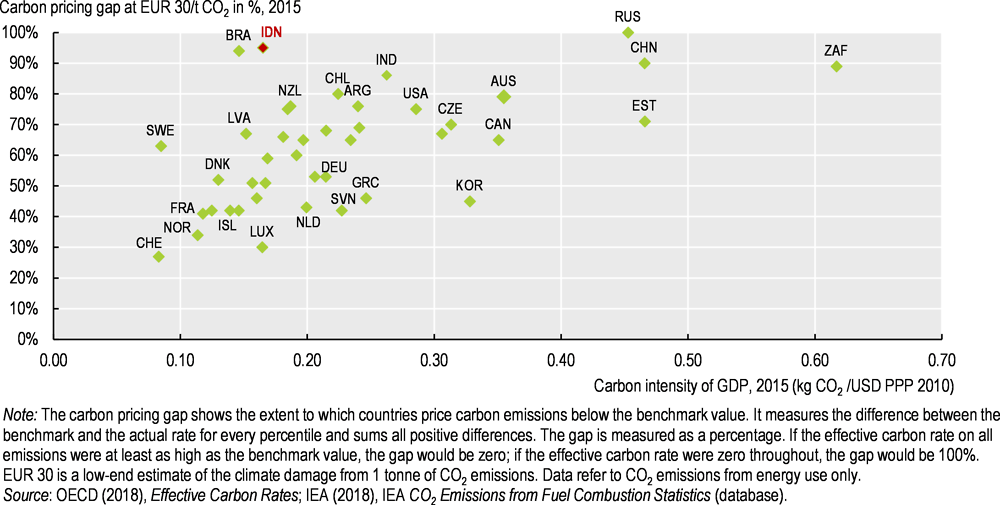

The limited use of taxes on energy use means CO2 emissions from energy use are virtually untaxed. In 2015, only 16% of CO2 emissions from energy use were priced (the second lowest value among 42 OECD and G20 countries), and none were priced above EUR 30 per tonne of CO2, which is a conservative estimate of the climate damage from 1 tonne of CO2 emissions (OECD, 2018d). Among emerging economies, Indonesia has the second highest carbon pricing gap, at EUR 30 per tonne of CO2, highlighting its lag in use of cost‑effective policies to decarbonise the economy (Figure 2.3). In addition to low taxes, Indonesia applies policies that reduce energy production costs and end-user prices relative to other forms of investment or consumption, thereby effectively running counter to energy taxation. Examples include subsidies for energy production and consumption, and domestic sales mandates (Section 2.4). As a consequence, energy prices are well below their associated social and environmental cost.

Figure 2.3. Energy taxes do not reflect the climate cost of fuel use

The government considered introducing a carbon price in 2009, when the Ministry of Finance published a green paper on climate change identifying policy options that would help the country reach its international climate change commitments. The paper recognised that energy prices were below social costs and recommended gradually removing energy subsidies and introducing carbon pricing, as well as complementary measures to promote energy efficiency and low‑emission technology. It proposed using international public financing and incentivising regional governments to undertake carbon abatement measures in the land-use sector through the intergovernmental fiscal transfer system. The paper argued that cost-effective climate policy would give Indonesia an early-mover and competitive advantage relative to other countries in the region (MoF, 2009).

The green paper proposed applying a carbon tax on fossil‑fuel combustion for electricity generation and large industrial installations as of 2014, at USD 10 per tonne of CO2. It was estimated this would raise IDR 95 trillion (USD 7 billion) by 2020. In line with international practice, the paper suggested gradually increasing the tax rate and using part of the revenue to alleviate the impact of higher prices on vulnerable communities through cash transfers, or supporting low-emission technology and efficiency improvements in business. Modelling conducted for the paper indicated that a relatively low carbon tax of USD 10/ t CO2 could reduce emissions from fossil‑fuel combustion by around 10% compared to business as usual by 2020 without negatively affecting growth or poverty reduction aspirations, especially if the revenue was recycled (MoF, 2009). No legislation has been introduced to impose the tax. However, Presidential Regulation No. 77/2018 provides a legal framework for carbon trading and reception of international grants or funds for emission reduction. Establishment of emission limits, e.g. for selected industries, would support effective implementation of a carbon trading mechanism in Indonesia.

In the absence of an explicit carbon tax, bringing energy taxes closer to the marginal social costs associated with its use is all the more important for greening the economy cost‑effectively. It would also help Indonesia raise tax revenue while making the adoption of renewables or low-emission technology more attractive. A first step would be to lift the 5% cap and raise the regional automotive fuel tax to a level that more realistically reflects externalities of fuel use. Further, a price signal needs to be established in non-road sectors (which account for the majority of energy use). This can be done either through an explicit carbon price (as suggested in the 2009 green paper) or fuel excise taxes, which put a price on the carbon content on fuel and therefore have a similar potential to change polluting behaviour. Acting sooner, while energy demand is still relatively low and the adverse impact on industry and residential and commercial energy use would be limited, would help put the economy on a sustainable low-carbon growth path at lower cost (OECD, 2018a). Indonesia can build on the experience of other middle-income countries that are implementing carbon pricing mechanisms (Box 2.3). The government has begun to study potential carbon pricing mechanisms, including a cap and trade system for the power sector, the pulp and paper industry and the cement sector.

2.3.3. Transport taxes and charges

Economic growth, rising incomes, population growth and urbanisation have increased the number of cars and motorcycles in use. This has led to rising energy consumption, emissions of GHGs and local air pollutants, and crippling congestion (Chapter 1). As the motorisation rate is expected to continue to rise, fiscal policies have a role to play in managing the associated environmental impact and, ultimately, encouraging a shift towards more sustainable mobility modes, which current vehicle taxation does not sufficiently do. Indonesia’s vehicle taxes are not linked to environmental and economic externalities of transport use, such as GHG emissions, air pollution and congestion, and thus are behind international best practice. Road pricing is limited to toll roads on Java and Sumatra.

Vehicle taxes

Revenue from vehicle taxes is significant, amounting to 0.5% of GDP in 2016 (compared to 0.4% of GDP, on average, in the OECD) (OECD, 2018b). Vehicle taxes are an important source of revenue for subnational governments, accounting for about 20% of their total tax income. The revenue has increased markedly since 2010, reflecting sharp growth in the vehicle fleet (Figure 2.2). A slight decline in revenue over 2013‑16 reflected a slowdown in vehicle sales, which recovered in 2017‑18.

Box 2.3. Carbon pricing instruments in middle-income economies

Worldwide, 67 jurisdictions used some kind of explicit carbon pricing in late 2017 and many more effectively price carbon through excise taxes. Among carbon pricing instruments, carbon taxes have been particularly attractive to developing and emerging economies due to their simple administration compared to emission trading systems (ETS). Carbon taxes can be added to existing fuel tax systems and there is no need to measure actual emissions at a large number of plants. A tax can also generate revenue from the informal sector. Flanking measures (e.g. lump-sum or targeted transfers) can help mitigate the adverse affordability impact for the most vulnerable households as well as competitiveness concerns. The examples below showcase some middle-income countries that recently launched, or are about to launch, carbon pricing mechanisms to meet their Paris Agreement commitments.

Colombia began imposing a carbon tax on 1 January 2017 on fossil fuels used for combustion, with exemptions for natural gas consumers outside the petrochemical and refinery sector. Companies may pay the tax using offset credits from projects in Colombia that are verified by accredited auditors. The expected revenue of USD 229 million a year is earmarked for the Colombia Peace Fund, which supports activities such as watershed conservation, ecosystem protection and coastal erosion management.

Mexico, like Indonesia, has long regulated energy prices, with fossil fuels sold at subsidised rates. Since 2014, reforms have reduced energy subsidies and later increased taxes on the main transport fuels. Mexico introduced a carbon tax that applies to most fossil fuels. The price and tax reform went into effect gradually, with initially low prices, to increase policies’ political acceptability. Mexico is now considering introducing an ETS. In 2017, it launched a year-long ETS simulation exercise to strengthen national capacity regarding the design, organisation and operation of an ETS. Over 90 companies in the power, steel, cement, refining and chemical sectors are participating voluntarily to get experience using registries and logging transactions.

A similar ETS simulation is being launched in Thailand over 2018‑20, building on a voluntary ETS in 2015‑17, when the system was first tested.

After multiple delays, South Africa’s parliament approved a carbon tax in February January 2019 at ZAR 120 (about USD 7.5/t CO2). Only certain entities above set thresholds (e.g. total installed thermal capacity of 10 MW) will report emissions and pay the tax in the first phase, to 2022. Complementary tax incentives and revenue recycling measures aim to minimise the impact on electricity prices and energy-intensive sectors such as mining, iron and steel. The reform will be revenue neutral.

Source: World Bank, 2017a; KPMG, 2018; OECD, 2018d; Arlinghaus and van Dender, 2017; Reuters, 2019.

Indonesia applies two types of one-off purchase taxes, in addition to VAT: a vehicle registration (or transfer of title) tax and a luxury-goods sales tax. The vehicle registration tax, levied at the provincial level, is up to 20% of the sale price for the first car.5 This means older and likely more polluting cars pay less tax. The luxury sales tax is an ad‑valorem tax on the factory price. The rate can be up to 125%, depending on engine size, vehicle type and whether the car was imported or produced domestically. The tax increases with engine size, incentivising purchases of smaller cars that tend to be more fuel efficient. However, the tax design provides some perverse incentives, for example by exempting pickup trucks, which emit high levels of local air pollutants and GHGs. Certain types of low‑emission cars, such as hybrids and electric vehicles, which are both imported, face high import duties.

The vehicle ownership tax is levied annually at the provincial level. Law No. 28/2009 provides that its rate is based on two elements: the vehicle’s assessed value and its weight (to reflect the degree of road damage or pollution it causes). The link with vehicle weight is not well promoted and people typically believe the tax is based only on value (MoF, 2015b). Thus, in the absence of stronger awareness‑raising efforts, it is unlikely to have an impact on consumer choice. As the value of a car, and thus the tax liability, decreases over time, the tax potentially creates an incentive against renewal of the vehicle fleet towards more fuel-efficient cars. Indeed, the overall tax burden on used cars is lower in Indonesia than in other Asia-Pacific countries (APEC, 2016). Coupled with the relatively high purchase taxes, this means people have few incentives to replace old vehicles with new, potentially more fuel-efficient and less polluting cars.

Some subnational governments have started to more explicitly incorporate environmental objectives directly into vehicle taxation. Jakarta and East Java provinces, for example, impose additional annual ownership taxes on each car after an individual’s first car in a bid to deter car ownership. However, this is commonly avoided by registering cars to different names (MoF, 2015b). Jakarta also imposes additional surcharges on passenger vehicles with engines of more than four cylinders or weight above 1.5 tonnes, such as SUVs (SmartExpat, 2017). Generally, heavy vehicles, such as trucks, continue to enjoy big tax breaks and face less than 50% of the tax burden on cars (APEC, 2016).

The national government reduced the luxury sales tax for so‑called low-cost green cars to zero, provided they are assembled locally with at least 40% local content. This is aimed at boosting local demand and increasing motorisation while promoting greener technology. To be defined as a low-cost green car, a vehicle must have an engine smaller than 1 200 cc (15 00 cc for diesel cars) and get at least 20 km per litre. There is some evidence that this has increased sales of such cars (MoF, 2015b). The government is reviewing the tax incentive to encourage a broader set of low-emission vehicles (i.e. beyond small low-cost cars), including electric cars and hybrids. A local content requirement is likely to be in place. This may impede diffusion of zero-emission cars, given the lack of domestic supply.

There remains substantial scope to make motor vehicle taxes better influence purchasing decisions. The World Bank (2018a) estimates that better aligning motor vehicle taxes with environmental externalities from vehicle use and transforming the luxury goods tax into a specific excise tax (to avoid transfer pricing) could increase revenue by 0.6% of GDP. One option would be to link the main taxes (e.g. registration and ownership taxes) to parameters such as fuel efficiency or emissions of GHG and local air pollutants, as several OECD countries do. The government has begun discussions on switching vehicle taxation from engine size to emission levels. Linking vehicle taxes to fuel efficiency would be particularly justified in Indonesia, where no fuel efficiency standards exist and where fuel taxation is very low. Reducing import tariffs and local content requirements would help accelerate diffusion of fuel-efficient and low-emission cars.

Road pricing

Road pricing has increased with the construction of some 1 000 km of toll roads, albeit mainly in Jakarta. As the government moves to electronic road pricing, variable pricing (e.g. linked to congestion and pollution levels) could be considered. This would allow charging of higher prices and encourage drivers to switch to other transport modes (e.g. public transport) when roads are busy or ambient air quality is above the national or local standard. The government may also consider broader congestion pricing (outside toll roads) in heavily congested areas, such as central Jakarta (Chapter 1). An electronic congestion charging system has been under consideration by the Jakarta government, and infrastructure construction was initiated, but implementation has been delayed. In the meantime, an odd-even system6 was introduced, which potentially incentivises wealthy households to purchase a second vehicle.

2.3.4. Taxes and fees on natural resource extraction

Water abstraction and use

Two charges are levied on water resource abstraction: a surface water tax (at the provincial level) and a groundwater tax (at the local level). Both are based on “obtained water value”, which is set in local regulations and depends on the water source, location, abstraction method, utilisation purpose, volume, quality and environmental conditions. Nationwide, the two taxes yielded revenue of about IDR 600 billion (USD 45 million) each in 2016 (about 0.4% of total subnational tax revenue). The tax rate and revenue can vary widely across the country, however. In the Sukabumi district of West Java, for example, the local groundwater tax provides nearly 20% of local revenue (Sunarti and Hayati, 2017).

A significant share of water use is exempted from the groundwater tax, including domestic use, irrigation for agriculture and small water suppliers (depending on regional regulation). Many larger users operate without a water abstraction permit and hence do not report and pay for the water they abstract. In Jakarta, it has been estimated that only 8% of annual groundwater abstraction is reported (Sunarti and Hayati, 2017). The tax is thus unlikely to encourage sustainable groundwater management.

The critical situation of many aquifers (Chapter 1) requires enhanced effort to control and enforce groundwater regulations, including taxation. The government is hesitant to remove tax exemptions for households, which is understandable given that the majority of Indonesians lack access to piped water networks and thus rely on alternative sources such as wells. An expansion to other users (e.g. small commercial groundwater providers using wells) could be considered: it would help reduce pressures on aquifers while increasing local government revenue and capacity to invest in water supply. For example, Rio de Janeiro state in Brazil uses part of the revenue from water abstraction charges to fund investment in wastewater collection and treatment (OECD, 2015a). Mexico uses a portion of its revenue to support payment for ecosystem service programmes that encourage conservation in watersheds, forests and other priority areas for biodiversity.

Fiscal treatment of other natural resources

Indonesia’s wealth in natural resources is an important source of tax and non-tax revenue. In addition to general taxes (on value added, corporate income, property, etc.), natural-based sectors are subject to taxes, fees and charges on resource use, revenue, permits and concessions, and public services. This revenue is reported in the annual budget as “non-tax state revenue” (penerimaan bukan pajak, or PNBP) for the oil, gas, mining, forestry, fishery and geothermal sectors. As not all of these fall under the OECD definition of environmentally related taxes and as no detailed breakdown is available, PNBP revenue is not included in the earlier discussion of environmentally related taxes.7

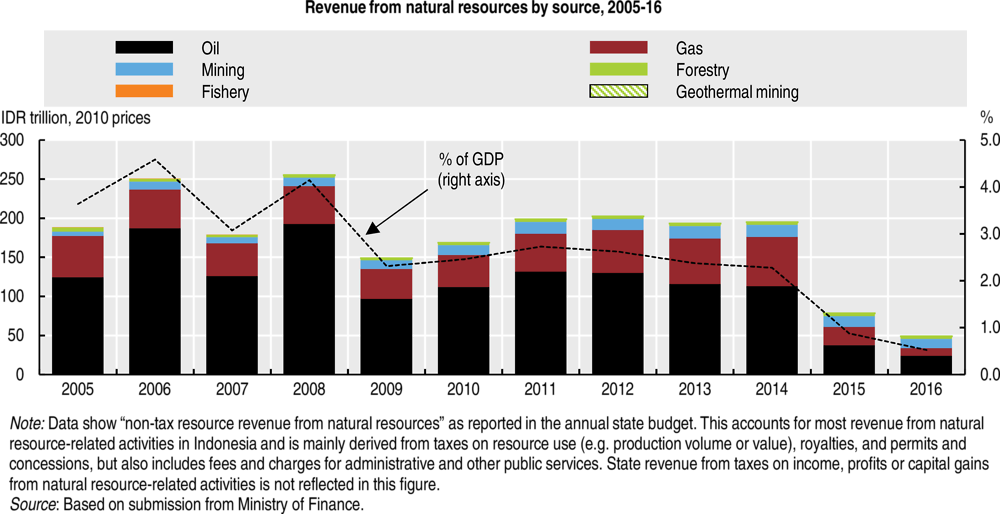

In 2005‑14, PNBP revenue from natural resources averaged 3% of GDP annually, mostly from crude oil and natural gas (Figure 2.4). The sharp fall in international oil and gas prices in 2014 led to a dramatic decline in revenue in 2015 and 2016, which was compounded by an unattractive fiscal regime that weighed on activity and revenue (OECD, 2018a). Revenue from renewable resources (forestry and fisheries as well as geothermal energy) increased in absolute terms, but remains small at about 0.05% of GDP.

Figure 2.4. PNBP revenue from natural resource use has declined markedly

Since the 2001 decentralisation reform, revenue is shared between the central and subnational government levels according to specific formulas (Table 2.2).8 The reform delegated more authority to subnational governments to manage natural resources, increased their share in natural resource-related revenue and provided them with revenue-raising power (Ardiansyah, Akbar and Amalia, 2015). Decentralisation brought challenges as well, however, including governance problems and weak capacity for monitoring and law enforcement at the local level, leading to illegal and unsustainable extraction, especially in mining and forestry. This weighs on revenue while creating environmental costs. Strengthening law enforcement and land-use governance is a condition for a more efficient fiscal regime as well as effective and sustainable land use more generally.

Table 2.2. Municipalities enjoy the lion’s share of revenue from natural resources

|

Sector |

Revenue source |

Percentage share (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Central government |

Provincial government |

Producer district/ municipality |

Other districts/ municipalities in the province |

|||

|

Oil |

84.5 |

3 |

6 |

6 |

||

|

Natural gas |

69.5 |

6 |

12 |

12 |

||

|

Mining |

Land rent |

20 |

16 |

64 |

- |

|

|

Royalty (exploration and exploitation) |

20 |

16 |

32 |

32 |

||

|

Forestry |

Reforestation levy |

60 |

- |

40 |

- |

|

|

Resource rent |

20 |

16 |

32 |

32 |

||

|

Land rent |

20 |

16 |

64 |

- |

||

|

Fisheries |

20 |

- |

80 |

- |

||

|

Geothermal |

20 |

16 |

32 |

32 |

||

Note: 0.5% of the revenue sharing from oil and gas is allocated to provinces and local governments as an additional fund for education (earmarked grant).

Source: Budi et al., 2012.

Oil, gas and mining

Most non-tax revenue is raised from oil and gas extraction via production-sharing contracts, which split the extracted resource between the government and the contractor. Non-tax revenue from mining mainly stems from royalties and land rent. The overall government take from resource extraction is relatively high in the oil sector but lower in mining (NRGI, 2015; Arnold, 2012). Royalty rates have long been governed by provisions in individual mining contracts and licences, which are not disclosed. The 2009 Mining Law replaced the system of individual contracts with one based on concessions, or mining business permits, in which taxes and royalties are paid according to the general law, rather than negotiated contracts.9 This shift should help increase transparency about tax and royalty payments of individual companies. Indonesia’s participation in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is also helping improve transparency in the sector. In March 2018, the government announced that beneficial ownership of mines must be revealed (OECD, 2018; PwC, 2018).

Improvement to management of the mining sector will be as important as higher royalty rates to increase state revenue. The 2009 Mining Law, which gave subnational governments the authority to grant mining licences, has led to a marked increase in the number of licences issued. Yet limited management, oversight and enforcement capacity at the local level, along with the lack of a single cadastre, left room for overlapping licences and mining in prohibited locations such as protected forests, along with unsustainable mining practices and illegal or misreported mining, resulting in a loss of government revenue (EITI, 2015). In 2017, mineral and coal mining companies owed the government some IDR 5.1 trillion (USD 380 million) (Esterman, 2017). To address this, the government has tightened regulations and introduced a “clean and clear” certification system under which mining companies must prove they meet financial and other technical requirements. A continued push for transparency in the issuance of mining permits will help ensure better oversight and enforcement of permit law and pave the way for a more efficient fiscal regime.

Forestry

Revenue from the use of forest resources is small and declined from around 0.11% in 2005 to 0.03% of GDP in 2016. The main levies in terms of revenue generation are payments to the Reforestation Fund (Dana Reboisasi, or DR) and the Forest Resource Rent Provision (Provisi Sumber Daya Hutan, or PSDH), although other revenue streams have increased in size since the mid-2000s.10 Both levies are based on the volume of timber extracted, with rates depending on species, timber grade and where it was harvested.11

The DR rate and the benchmark price of the PSDH (on which the rate is based) are too low to capture a significant share of economic rent. The rates have remained largely unchanged since the turn of the century, despite rises in market prices for timber. Inflation alone eroded about 75% of the real value of the PSDH benchmark price between 1999 and 2014 (KPK, 2015). In March 2012, the Ministry of Trade nearly doubled the benchmark price, but after vigorous opposition from the forest industry it reverted to the previous level a month later. For such fees to work effectively towards efficient and sustainable resource use, it is important for the government to use objective standards that reflect environmental externalities of resource extraction in determining rates, rather than responding to political pressure.

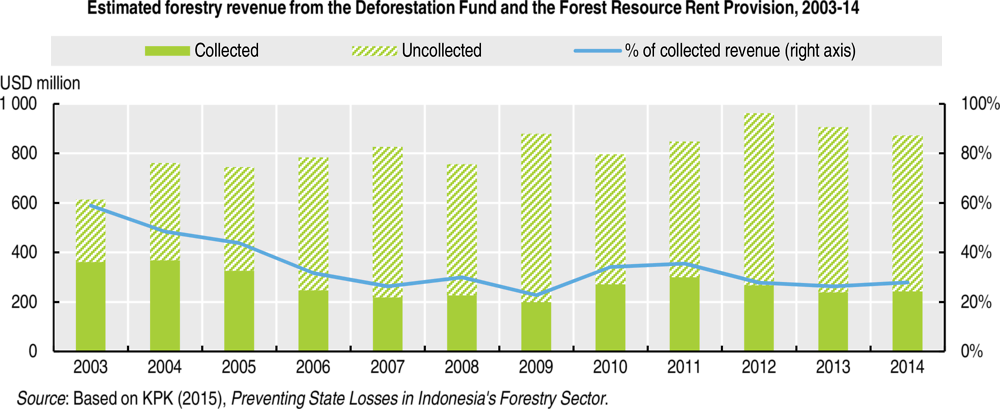

Between 2003 and 2014, only one-third of potential revenue from the DR and the natural forest component of the PSDH were collected, leading to forgone revenue of USD 539 million to USD 749 million a year (Figure 2.5). This has been attributed to insufficient management of data on reported timber production and revenue collection, inadequate controls, ineffective law enforcement and the prevalence of a shadow economy for illegally harvested timber (KPK, 2015). The launch of the online Forest Product Administration Information System in 2016, which aims to improve data collection, analysis and dissemination of timber forest products, will help redress this situation.

Figure 2.5. Two-thirds of potential revenue from concessions in natural forests is not collected

The failure to better capture economic rents from timber production has implications not only for tax collection, but also for forest management sustainability (KPK, 2015). Since the early 2000s, there has been a shift from selective logging in natural forests (a model for sustainable forest management) to timber harvesting from plantations and land clearing (where harvesting costs are significantly less) (Chapter 3). As a step in the right direction, the government issued new rates for the Forest Estate User Fee, a concession levy collected from mining and plantation companies, to better capture economic rents from forestry use. Raising the DR, PSDH and other fees should also be considered.

Fisheries

Revenue collection from the fishery sector has long been sluggish due to significant illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. For example, the Ministry for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries estimates that only 40% of the nearly 9 900 operational ships with capacity of more than 30 gross tonnes (GT) are legally licensed. Aggressive undersizing of vessels further reduces revenue from the sector. The World Bank (2015) estimates that USD 20 billion worth of maritime resources are stolen per year by foreign and local fishing companies. Commercial fishing companies are subject to a licence fee, a fish levy and service fees. These apply to all vessels with capacity above 30 GT, or more than a 90 horsepower engine, and operating outside 12 nautical miles. The amount is based on the size of fishing fleets; higher rates apply to foreign fleets (Winter, 2009).

The government has accelerated efforts to collect more revenue: it has banned transhipment at sea, required all boats over 30 GT to use vessel monitoring systems, initiated a controversial campaign of sinking illegal (foreign) boats, and increased the budget of the Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries (OECD, 2018a). This helped revenue more than quadruple between 2015 and 2016 (to reach IDR 300 billion), even though the volume of total marine fish capture slightly decreased. Efforts to improve monitoring and law enforcement on fishery activities should continue. In the medium‑term, expansion of the fishery levies to smaller vessels should be considered, given that small-scale fishing makes up 95% of Indonesian fishery management (Chapter 1).

2.4. Reforming environmentally harmful subsidies

2.4.1. Support to fossil‑fuel consumption and production

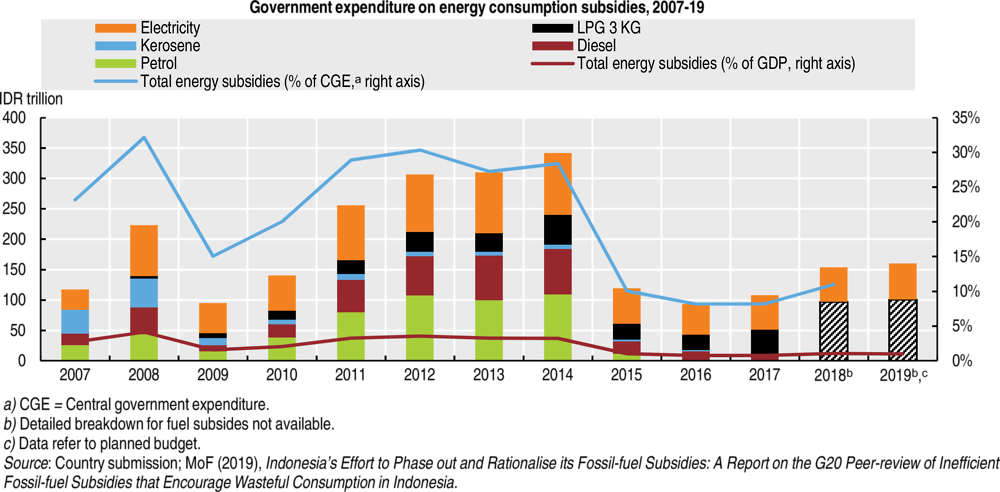

Indonesia has made great strides in reducing fossil-fuel subsidies in recent years. The country has a long history of subsidising energy use to keep energy affordable for the poor, increase energy access and raise household purchasing power. The bulk of support has stemmed from the government subsidising end-user prices for petrol, diesel, electricity and other energy products. Until 2014, these subsidies accounted for roughly 30% of central government expenditure, equal to nearly 4% of GDP (Figure 2.6). At the same time, subsidies were poorly targeted and highly regressive. Pressured by an increasingly large fiscal burden, the government has embarked on major reforms aimed at ensuring fiscal sustainability and better targeting. This helped cut subsidy expenditure by roughly half between 2014 and 2015 (Figure 2.6), freeing revenue for infrastructure and social programmes.

However, not all price reforms have been implemented as announced, putting into question the stability and durability of reform. Expenditure for fossil‑fuel consumption support still amounted to IDR 95 trillion in 2017 (nearly four times the amount of energy-related tax revenue) and soared to IDR 153 trillion (USD 10.7 billion) in 2018. The government does not systematically track subsidies to fossil‑fuel production, although it began to compile and quantify such measures in the framework of the G20 peer-review process on phasing out inefficient fossil-fuel subsidies (see OECD, 2018e for details). Such information will help the government understand whether the subsidies are achieving their objectives cost‑effectively. It will also help identify inefficient measures and prioritise ones to be phased out. To date, no plans exist to reduce production-based subsidies.

The government should implement a step-by-step phase-out of fossil-fuel subsidies and rigorously stick to its timetable, rather than responding to short-term budgetary or political pressures. The subsidies are holding back Indonesia’s transition to a sustainable energy system, taking much-needed resources from the budget while also discouraging energy conservation and the switch to cleaner alternatives. Transparency about subsidy costs, benefits of their removal and strategies for compensation can help build public acceptance and support. Equity and poverty reduction concerns are best addressed through direct support to vulnerable households, rather than subsidies for energy use. Recent OECD analysis shows that increasing taxes on electricity can reduce energy affordability risk if parts of the additional revenue is transferred back to households (Flues and van Dender, 2017). Indonesia could build on its experience in using social safety net programmes to reduce the impact of price increases on the poor.

Figure 2.6. Indonesia has significantly cut subsidies to fossil‑fuel consumption

Petrol and diesel

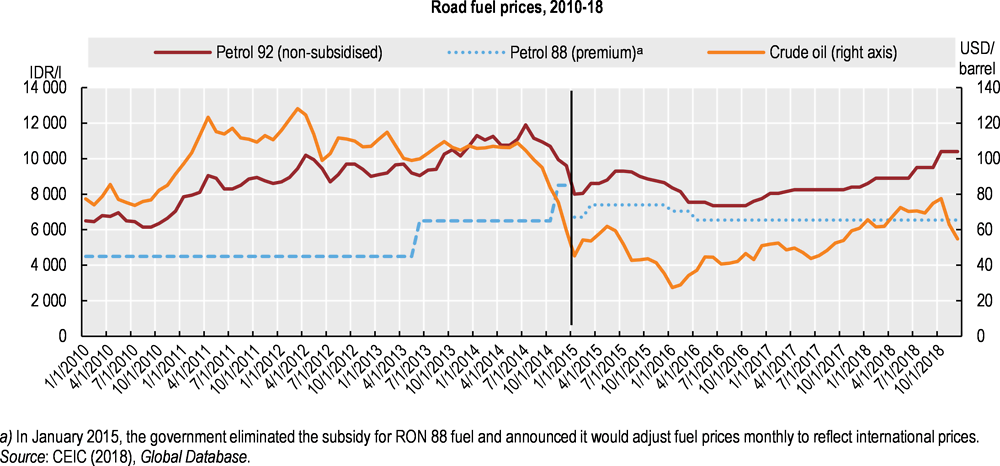

End-user prices of transport fuels have been subsidised for decades. Subsidies have mainly involved the government compensating the state-owned energy company Pertamina for the low end-user prices the company is allowed to charge on its RON 88 petrol (called “premium” in Indonesia) and diesel sales. In 2013, the government raised premium petrol prices by 44% and diesel prices by 22%, bringing them closer to market prices (Figure 2.7). This upward adjustment, the first since 2008, was accompanied by cash transfers to 15.5 million households over four months, as well as increased spending on education and health. A second increase followed in November 2014. Aided by the unexpected decline of global crude oil prices, the government effectively eliminated the subsidy for premium petrol in January 201512 and fixed the diesel subsidy at IDR 1 000/litre (USD 0.07/l) below market prices, followed by a reduction to IDR 500/litre (USD 0.035/l) in 2016. The combination of subsidy reform and lower oil prices reduced the subsidy budget for premium petrol and diesel by more than 90% over 2014‑16 (Figure 2.6).

The government announced it would adjust RON 88 prices to international prices every month, but has been reluctant to do so in practice. Fuel prices have remained constant since April 2016 even though global crude oil prices have risen (Figure 2.7). In March 2018, the president announced that fuel and electricity prices would be kept stable until at least the end of 2019; in June 2018, diesel subsidies were increased from IDR 500/l to IDR 2000/l (The Jakarta Post, 2018a).

Figure 2.7. Subsidies for fuel have not been adjusted to oil market prices since 2016

In January 2017, the president launched a single fuel price policy (introduced through Energy Ministry Regulation No. 7174/2016) to improve equity and social justice by levelling fuel price disparity across the archipelago. Fuel retail prices in remote areas are up to three times higher than prices in Java because logistical, operational and development costs are higher. Implementation of the new policy will require significant infrastructure investment by Pertamina. It will also dramatically raise the company’s operating costs, by up to an estimated IDR 900 billion per year (Indonesia Investments, 2016), as fuel distributors operating in remote and underdeveloped areas will be entitled to higher profit margins to encourage distribution in these areas. Pertamina was initially expected to cover the costs incurred under the single fuel price policy without additional subsidies, effectively shifting the subsidy burden from the state budget to Pertamina. The company initially planned to finance this through a cross-subsidy from its other business activities, notably the sale of non-subsidised fuels. Yet in the first year the policy was in effect, the company already reported losses of IDR 5 trillion (GSI, 2018). In November 2017, it was announced that the government would compensate Pertamina up to USD 1.3 billion (in addition to subsidies) for the fuel sale costs associated with the single fuel price policy as well as the freezing of fuel prices (Jakarta Globe, 2018). In the long term, investment in the necessary infrastructure should ensure access to energy more efficiently than artificially levelling fuel prices.

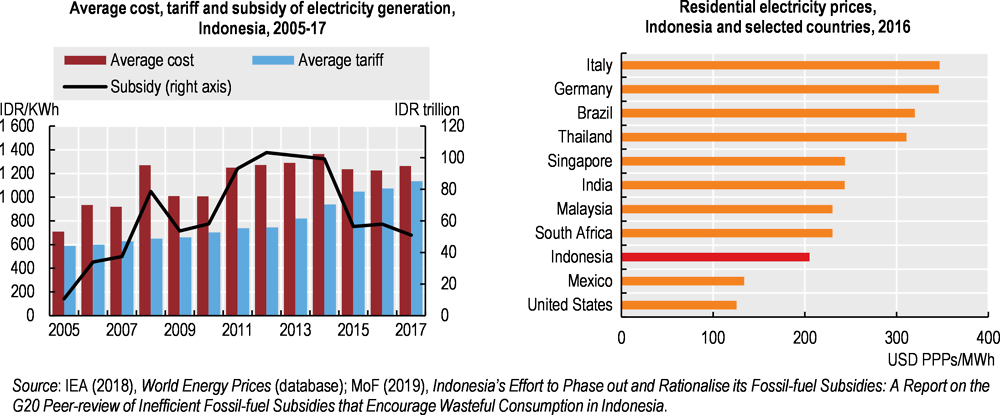

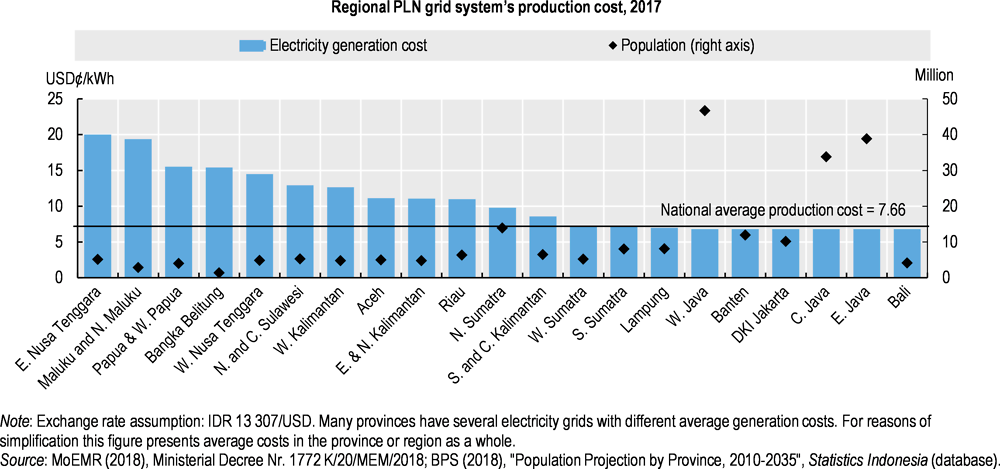

Electricity

As with the petrol and diesel subsidy, the government subsidises electricity in terms of end-user prices. It sets electricity tariffs (which the parliament must approve) and compensates PLN for the difference between the retail tariff and the average cost of generating electricity. In the early 2010s, average retail tariffs were about two-thirds of PLN’s production costs. The gap has narrowed as the government began to better target the subsidy, but tariffs remain below cost, on average, and low by international comparison (Figure 2.8).

Between 2013 and 2017, subsidies to 30 million electricity consumers were phased out (OECD, 2018e). Electricity tariffs for these consumers were gradually increased until they reached market value, and now a monthly price adjustment mechanism keeps them at a level that would match PLN’s production costs. At the end of 2016, only lower-income households (defined as subscribers of 450‑VA and 900‑VA electricity) remained subsidised – which still represented about 70% of PLN’s customers. The government later split tariffs within the 450‑VA and 900‑VA classes into subsidised (for poor households) and non-subsidised (for wealthier households). The split was made possible by the availability of new household income data, based on Indonesia’s unified poverty database. The non-subsidised rate was charged to wealthier 900‑VA customers in 2017, reducing the number of subsidised consumers from 23 million to 4 million. Tariff adjustment for wealthier 450‑VA consumers was also planned, but later suspended (OECD, 2018e).

Between 2013 and 2017, the average electricity tariff increased by 40% and the subsidy was reduced by half (Figure 2.8). As the government announced it would keep electricity prices constant through at least 2019, the electricity subsidy allocation in the 2018 state budget was set to increase. The subsidised tariffs continue to be significantly below production cost (e.g. the tariff for households with a 450‑VA power connection is IDR 417, or USD 3.1 cents, per kilowatt hour, compared to production costs of IDR 1 260 in 2017).

Figure 2.8. Electricity tariffs are below the cost of supply

Kerosene and LPG

The government has long subsidised the end-user price of kerosene, which is widely used for cooking. In 2007, it introduced the Kerosene-to-LPG Conversion Program in a bid to tackle rising government expenditure on kerosene subsidies while improving access to clean cooking fuel (LPG has higher energy intensity and emits less pollution than kerosene). The programme encouraged the shift by distributing a free stove, one fill and an additional 3‑kg LPG cylinder to households, while in the meantime gradually withdrawing kerosene from distribution agents in the areas where the conversion packages had been distributed.

The programme led to a drop in kerosene use from 7.8 billion kg in 2008 to 0.5 billion kg in 2016, while LPG consumption jumped from 0.5 billion kg to 6 billion kg (OECD, 2018e). The subsidy budget for kerosene fell by IDR 45 trillion, and spending for LPG rose by IDR 21 trillion (Figure 2.6). There is a balance to be struck between the priority of ensuring access to clean cooking, on the one hand, and keeping LPG subsidies manageable while not encouraging wasteful energy consumption, on the other.

The budget burden associated with the LPG subsidy has been rising. The government has not adjusted the price of subsidised LPG (IDR 12 750 per 3‑kg cylinder) since 2008, nor has it narrowed the target groups. Anyone can buy 3‑kg LPG cylinders at subsidised prices, including wealthy and large consumers, and there is evidence that larger LPG cylinders are illegally being refilled from subsidised 3-kg cylinders and sold to large consumers. Acknowledging the need for reform, the parliament proposed providing the LPG subsidy only to the poorest 40% of households (and microbusinesses managed by those households), replicating the experience of the electricity subsidy reform. The LPG reform was to be implemented in 2017 but has been postponed twice due to revisions in the subsidy system and difficulties designing the reform, including the administrative and physical infrastructure of a smart-card system.

Oil, gas and coal production

Fossil fuel-producing industries benefit from fiscal incentives that aim to encourage reserve discovery and boost output (see OECD, 2018e for a detailed discussion). Estimates suggest that subsidies to coal producers alone amounted to at least USD 645 million in 2015 (Attwood et al., 2017). Several of the measures are still in place. The majority of the subsidies are tax incentives to the mining and processing industries (e.g. reduced VAT and corporate income taxes) and support to coal-fired power plants. In partnership with PLN, coal-fired electricity generators can apply for preferential loans, loan guarantees and subsidised credit. This policy, intended to secure power plant investment, is part of a 35 GW power capacity extension programme. Since 88% of Indonesia’s electricity generation is based on fossil fuels, the measures can be considered a government subsidy encouraging fossil‑fuel use.

Fossil‑fuel production is further supported through the domestic market obligation (DMO) policy. DMOs require oil, natural gas and coal producers to sell part of their output (usually between 15% and 25%) on the domestic market at heavily discounted prices. As DMOs provide Pertamina refineries and PLN power stations with cheaper feedstock, they can be characterised as producer support, even if they reduce the revenue of upstream companies (OECD, 2018e). In 2018, the government capped the price of coal sold to local power plants at USD 70/Mt for 2018‑19 (30% below the Indonesian reference price for equivalent coal sold for export) to allow for the announced electricity price freeze to the end of 2019 without overburdening PLN’s budget (Pardede, 2018). A price ceiling for natural gas is under discussion (The Jakarta Post, 2018b).

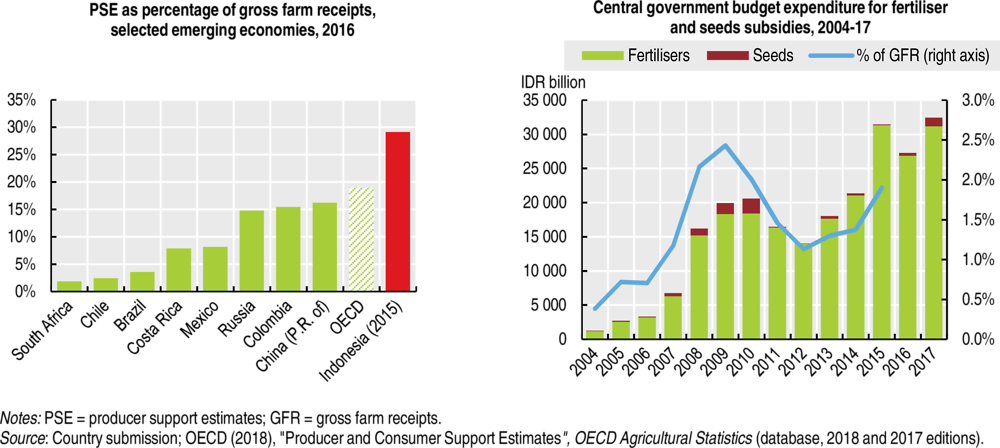

2.4.2. Support for agricultural production

Indonesia provides significant support to agriculture to foster its goal of food self-sufficiency.13 Support to farmers, as measured by the producer support estimate, reached 29% of gross farm receipts in 2015 (or 4.6% of GDP) (Figure 2.9). The vast majority of support is provided through market price support and support to fertiliser manufacturers, which are among the most market-distorting forms of support and potentially environmentally damaging (OECD, 2015b). Market price support is mainly provided though minimum prices for certain commodities (e.g. sugar, soybeans, paddy rice) and via trade policies (e.g. import restrictions and export taxes for certain products). These interventions have created significant gaps between domestic and world market prices (reaching nearly 100% for rice in 2015-16), increasing food costs for consumers, hampering the competitiveness of the agricultural sector and triggering international disputes. The World Trade Organization ruled against Indonesia on 18 trade restrictions in 2016‑17, including import bans on some products, selling restrictions and storage requirements for importers.

Budget expenditure for fertiliser subsidies increased more than tenfold (in real terms) between 2005 and 2017, when IDR 31 trillion (USD 2.3 billion) was budgeted (Figure 2.9). The steep increase was partly due to subsidised prices having been held constant despite growing fertiliser production costs. While subsidies are intended for small farmers (those producing on less than 2 ha), around one-third of fertiliser subsidies were misallocated in 2015 and largely benefited the largest farms (OECD, 2016a). In addition to economic inefficiency, such subsidies encourage wasteful use and pollution. Field studies in Lombok indicate fertiliser consumption above optimal levels (MoF and GIZ, 2017). The government plans to reform the subsidy, potentially using a smart card to better target the subsidy to small farmers.

Figure 2.9. Support to farmers has grown significantly

An alternative, more efficient way to support farmers’ income could be to provide vouchers that farmers then use for the type and quantity of inputs they want. More generally, a larger share of support should be allocated to general services, such as training and extension services; this share is relatively low in Indonesia (5.2% of total support in 2013‑15) and mostly benefits infrastructure development (84%) rather than agricultural innovation (7%) and knowledge transfer (4%) (OECD, 2018f). In addition, public financial support to industrial plantations (notably oil palm) and forest plantations should be redirected towards income support or environmental sustainability objectives, including ecosystem restoration (Chapter 3).

2.5. Investing in the environment to promote green growth

2.5.1. Public environmental expenditure

Budget allocation to the environment

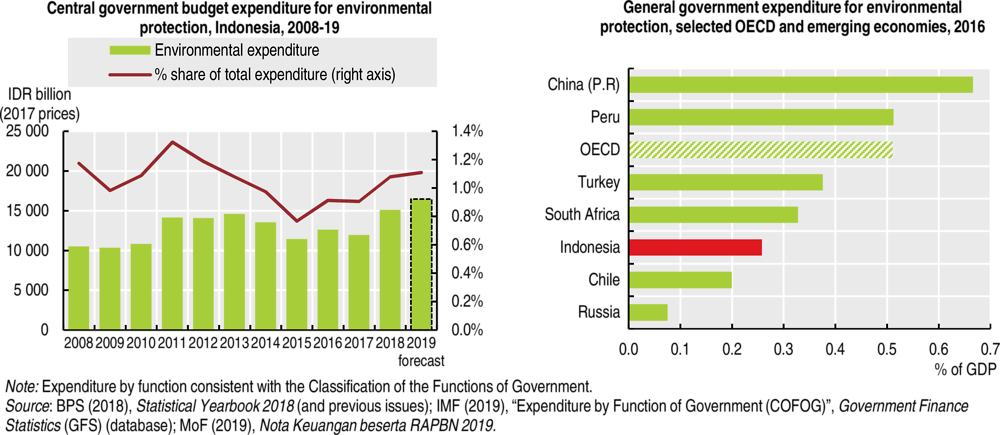

Until 2015, central government budget expenditure for the environment was on a declining trend. However, the 2018 budget raised the share to 1.1% – an absolute increase of 30% from 2017 (Figure 2.10). A breakdown of environmental expenditure in Indonesia is not available, but it includes waste and wastewater management, pollution control and natural resource conservation. The budget allocation to the MoEF has continued on a declining trend, from 1% of the total budget in 2013 to 0.8% in 2017 (GoI, 2018).14 Subnational environmental spending varies widely, from less than 0.1% of the provincial 2017 budget in West Java to more than 2% in Jakarta and South Kalimantan (MoF, 2017).

Figure 2.10. Environmental expenditure is set to rise

Green planning and budgeting

Indonesia has made major steps in tracking public finance related to climate change and is working to establish broader mechanisms to track investment promoting green growth. The 2012 Mitigation Fiscal Framework, developed by the Ministry of Finance, provided a first assessment of public finance used for climate change mitigation action. It found that 0.9% of the central government budget was invested in such action in 2012. While this represents an increase from 2008, when 0.3% was spent, maintaining that level of financing in real terms would mean Indonesia reaching just 15% of its 2020 mitigation target (MoF, 2014). Domestic climate finance is allocated almost entirely through the central government and through budget expenditure rather than grants, loans or revolving funds (CPI, 2014). A 2018 presidential decree established the Environmental Management Fund Agency to channel funds for environmental purposes, including international grants and revenue from carbon trading mechanisms.

In 2014, the Ministry of Finance launched the Green Planning and Budgeting Strategy to identify the “green economy gap” and develop scenarios on how to fill it, using both public and private resources. The strategy identified 21 priorities for green economic growth, including forest, peatland and coral protection. If fully met, the priorities could prevent most loss and damage from natural resource depletion and climate change. Analysis conducted under the strategy found that public green economy investment remained relatively stable at around 1% of central government expenditure in 2011‑14 (MoF, 2015a). This compares to 29% for fossil‑fuel consumption subsidies in the same period (although that share dropped to below 10% in 2016; see Figure 2.6). To maintain strong GDP growth of around 7% a year in a green economy scenario (one in which losses and damage from natural resource degradation would be avoided), public expenditure on green economy investment would need to rise to 3.8% by 2025 (MoF, 2015a).

In 2015, the government introduced a climate mitigation tagging system. Activities with climate mitigation purposes were tracked in six key ministries for the 2016 and 2017 state budgets; activities for climate change adaptation were tagged in 2017. The resulting data showed that state budget support to climate change increased from IDR 72 trillion (USD 5.4 billion), or 3.5% of the state budget, in 2016 to IDR 121 trillion (USD 8.5 billion), or 5.4% of the state budget, in 2018 (MoF, 2019). Of the 2018 budget share, 60% targeted mitigation and 40% adaptation. Allocations were highest for the Ministry of Public Works and Housing and the Ministry of Transport; the ministries that are expected to achieve the largest GHG emission reductions (the MoEF and the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources) received relatively small allocations. The experience gained from climate tagging should be assessed to inform extension to other areas of the green economy, including “traditional” environmental protection programmes. The planned expansion of budget tagging to subnational levels will yield useful information about local climate investment and could help identify and address potential bottlenecks in access to finance at the local level.

2.5.2. Greening the financial sector

Private investors will have to play a key role in meeting Indonesia’s green economy investment needs, in terms of both increased finance for green infrastructure and better integration of climate and other sustainability factors into finance and investment in general. To date, there has very little private green financing in Indonesia. Only 1.2% of total bank lending was considered green, according to a Bank Indonesia survey of 29 banks in 2012; the share was still considered negligible in 2015 (MoF, 2015a; Volz et al., 2015). This has been related to lack of demand for green credit (which is linked to low energy prices and weak enforcement of environmental standards) as well as lack of supply and capacity constraints in the financial sector (e.g. lack of experience with green lending and limited capacity to assess associated risk).

The Financial Services Authority (OJK)15 has taken steps to enhance the financial sector’s engagement in sustainable growth. It developed a Roadmap for Sustainable Finance, set up a national network of climate finance experts (an inter-ministerial working group), joined the Sustainable Banking Network and published guidebooks on sustainable finance for the industry. In 2017, as part of the roadmap, OJK issued a regulation on Application of Sustainable Finance for Financial Services Institutions, Issuer Companies and Public Companies, making Indonesia one of the first countries to have a regulation on sustainable finance. It outlines sustainable finance principles and obliges financial institutions to develop a sustainable finance programme and formally report on it to OJK through annual business plans, in addition to publishing public sustainability reports. The aim is to encourage lenders to assess potential borrowers based not only on financial but also social and environmental sustainability standards. The requirement will be rolled out gradually, starting with larger banks in 2019. Sanctions for non-compliance are administrative in nature (written warnings and compliance orders). Continued capacity building will be needed to enhance the understanding and practical application of sustainable finance principles among regulated institutions. As a next step, Indonesia could consider restricting access to finance for businesses that operate without, or do not comply with, an environmental permit. This would be a powerful tool to enhance environmental law enforcement.

In February 2018, Indonesia launched its first green bonds. The five-year “green sukuk” bonds (i.e. they comply with Islamic finance norms) are worth IDR 16.7 trillion (USD 1.25 billion). Cicero, a leading global provider of green bond assessments, rated the issue medium green – the second highest on a four-point scale. A 2017 OJK regulation stipulates that at least 70% of the proceeds from any green bond issue must be used to finance environment-friendly projects. The government intends to use all the proceeds of the 2018 issue to finance climate change mitigation and adaption activities, but stated that future issues could consider broader environmental projects, including on biodiversity and forest conservation. Indonesia has pledged to publish independently audited annual reports on the spending and impact of its bonds (Allen, 2018).

Public support measures such as specific credit lines and soft loans with technical support can help shift the risk-return relationship for commercial investors, making investment more attractive to them. Blended finance16 is gaining attention as a mechanism to attract private sector resources, both internationally and in Indonesia. In 2016, Indonesia launched the Tropical Landscapes Finance Facility to leverage private and long-term finance to projects and companies that stimulate green growth and improve rural livelihoods (Box 2.4). Blended finance has also been used to finance the mass rapid transit system in Jakarta. Both initiatives will provide lessons on using development finance and other public resources to attract private finance, thus informing the eventual establishment of similar mechanisms for other green sectors where investment risk is considered high (e.g. renewables, water and sanitation).

Box 2.4. The Tropical Landscapes Finance Facility

The Tropical Landscapes Finance Facility (TLFF), launched in 2016, uses public funding to unlock private finance for sustainable land use, including in agriculture and ecosystem restoration, and for investment in renewables. The TLFF co‑ordinates between government, the private sector and communities to foster positive change on a broad scale. Investment opportunities are impact focused and seek to involve marginalised communities as active partners. The TLFF consists of a loan fund and a grant fund. BNP Paribas and ADM Capital act as fund managers while the United Nations Environment Programme manages the secretariat. The inaugural deal, closed in early 2018, is a USD 95 million bond supporting socially inclusive, climate-friendly production of natural rubber. It is Asia’s first corporate sustainability bond.

Source: TLFF, 2018.

2.5.3. Investment in environment-related infrastructure

Indonesia has wide infrastructure gaps that hamper economic and social development. The World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report (WEF, 2017) cited inadequate infrastructure as a key problem in doing business (along with corruption, inefficient bureaucracy and restricted access to financing). At the same time, Indonesia’s ranking with regard to infrastructure improved from 90 in 2010 to 52 in 2018, out of 138 countries. Years of underinvestment have led to an estimated infrastructure deficit of USD 1.5 trillion (World Bank, 2017b), constraining growth, limiting the pace of poverty reduction and contributing to environmental pressures.

Recognising the challenge, the government targeted additional investment (private and public) to the transport, water, energy and other key sectors, amounting to USD 415 billion over 2015-19 (equivalent to 7% of GDP per year). The increase was in part made possible by the dramatic reduction in public spending on fossil-fuel subsidies (Section 2.4.1). Due to the long lifespan of infrastructure, failure to invest in the right type of infrastructure in the next 10 to 15 years would lock Indonesia into a GHG-intensive development pathway and risk stranding many assets (OECD, 2017a).

The private sector needs to play a bigger role in filling the infrastructure gap. Infrastructure investment largely relies on public finance, with the government accounting for 55% of total infrastructure investment in 2015 and state-owned enterprises (SOEs) most of the rest. The private sector contribution is relatively small, having declined to 9% over 2011‑15. The government has strongly emphasised improving the business climate and some progress has been made. A pipeline of projects was developed, on the public-private partnership model, though the complex legal landscape for the model resulted in delays and cancellation of some projects. Steps are being taken to simplify burdensome land acquisition processes, a major deterrent for private investors. Improving the transparency and efficiency of SOEs, which crowd out private capital in some sectors, would further help in mobilising private investment, as would reducing foreign investment restrictions and deepening local banking and capital markets (OECD, 2018a; World Bank, 2017b).

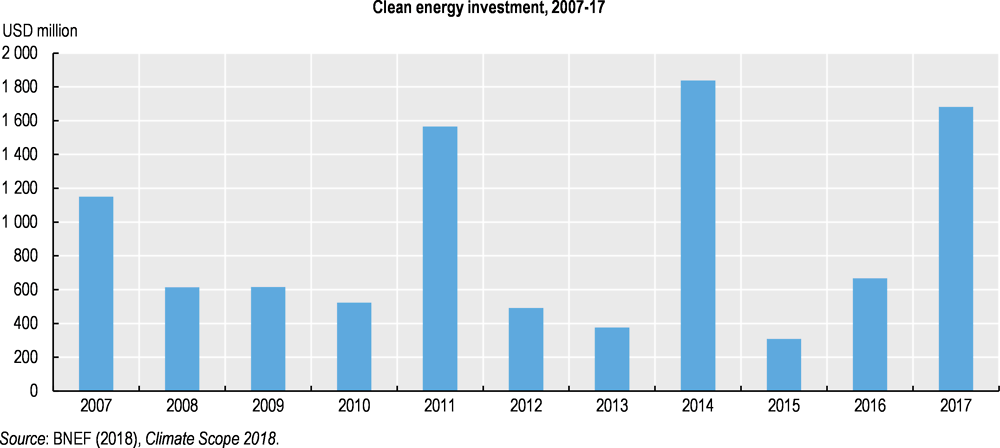

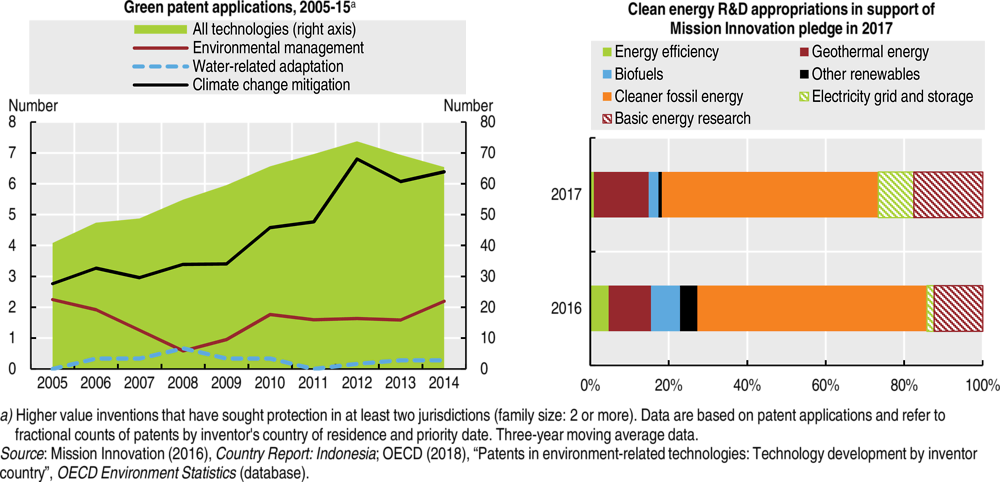

Investment in clean energy

Investment in renewables reached USD 1.6 billion in 2017 (Figure 2.11). This falls short of the estimated USD 15 billion a year needed to meet the target of sourcing at least 23% of energy supply from renewables by 2025 (IESR, 2017). Most renewables investment is channelled to geothermal energy and, to a lesser extent, biofuels – areas in which Indonesia is positioning itself as a global leader. Investment in wind and solar energy has been sluggish (REN21, 2018). Overall, investment in the energy sector remains heavily tilted towards fossil fuels. The government expected just 5% of total energy sector investment in 2018 to target renewables, with the majority going to the electricity sector (33%) as well as oil, gas and coal (62%) (The Jakarta Post, 2018c).

Various government incentives to attract clean energy investment have not led to new investment as hoped. The measures include feed-in tariffs (FiTs) for renewable electricity, ambitious biofuel blending mandates, fixed tax incentives such as income tax rebates, accelerated depreciation, exclusions from VAT and import duties, and the establishment of the 2009 Clean Technology Fund and 2017 Geothermal Fund. Weak political commitment, frequent policy changes and patchy implementation of government policy by PLN (which has a monopoly on electricity distribution) make renewables investment a risky undertaking, raising financing costs and thus reducing the economic viability of individual projects. Regulatory barriers such as slow land acquisition and permitting processes have further undermined investor confidence. Foreign equity restrictions and local content requirements raise projects costs, especially as local manufacturing industries (e.g. for solar PV) are relatively small (IISD, 2018; IRENA, 2017).