The assessment and recommendations present the main findings of the OECD Green Growth Review of Indonesia and identify 49 recommendations to help Indonesia make further progress towards greening its economy. The OECD Working Party on Environmental Performance reviewed and approved the assessment and recommendations at its meeting on 12 February 2019.

OECD Green Growth Policy Review of Indonesia 2019

Assessment and recommendations

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

1. Key environmental trends: An overview

Indonesia is the world’s fourth most populated country, and the largest archipelagic one. It possesses extensive tropical rainforests, which are home to some of the highest levels of biodiversity in the world. It is also endowed with vast energy and mineral resources. Economic and social progress since the 1997‑98 Asian financial crisis has been remarkable. Gross domestic product (GDP) has grown by more than 5% annually since the turn of this century, the poverty rate has been halved, living standards are rising and access to public services is improving. Natural resources are a mainstay of the economy, accounting for more than 20% of GDP and 50% of exports in 2017, and providing the livelihood of a large share of the population.

As in other emerging economies, fast development has increased environmental pressures from growing demand for land, water, materials, energy and transport. Although Indonesia has made progress in decoupling its strong economic growth from environmental pressures, unsustainable extraction of natural resources, pollution and environmental degradation remain serious challenges. The development of transport, waste management and water supply and sanitation services has not kept pace with population growth and urbanisation, creating environmental, economic and health costs, especially for vulnerable and poor people. Indonesia faces the complex challenge of maintaining strong and inclusive growth while addressing environmental pressures and risks that, if unchecked, will impede economic growth, development and citizens’ well-being.

The natural environment and archipelagic landscape are deeply rooted in the country’s cultural identity. Its tropical rainforests are home to iconic species, such as the orangutan and Sumatran tiger, and provide the livelihood of numerous traditional communities. Indonesians seem generally satisfied with their country’s state of environment (BPS, 2018) in spite of the challenges the country is facing. Continued efforts appear to be needed to enhance public awareness about the state of the environment, the carrying capacity of nature and its ability to provide ecosystem services, as well as the economic and health costs of environmental degradation. Dedicated campaigns and the integration of environmental education into school curricula, as has been done under the Green School programme, could help raise awareness. Efforts to strengthen the knowledge base and publicly disclose information on the state of the environment need to continue. In a welcome step, in July 2018 the government published a comprehensive report, The State of Indonesia’s Forests 2018. The authorities should also consider reviving regular State of the Environment reports (last published in 2014) and ensure regular publication of consistent reports at provincial level.

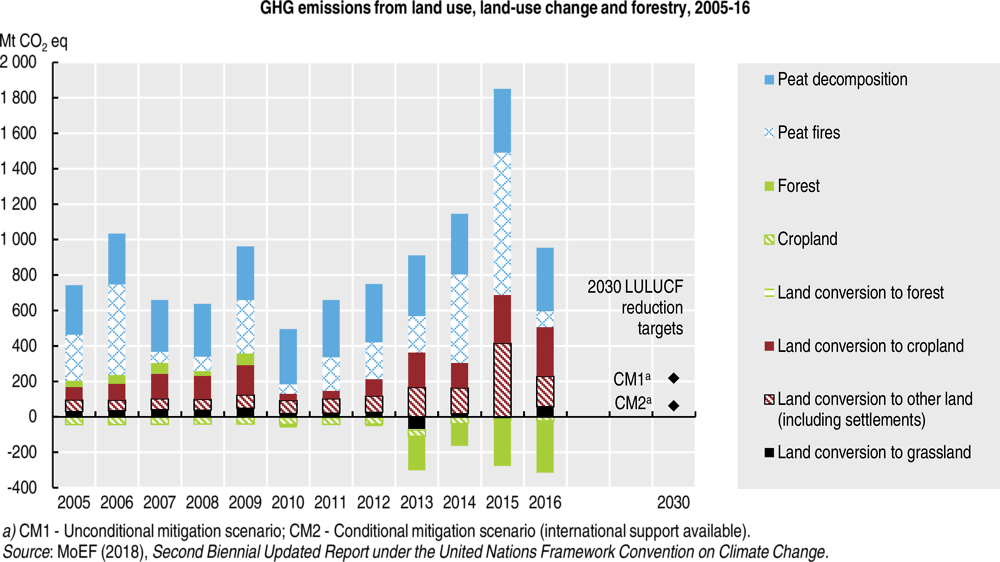

Accelerating climate change action to achieve mitigation targets

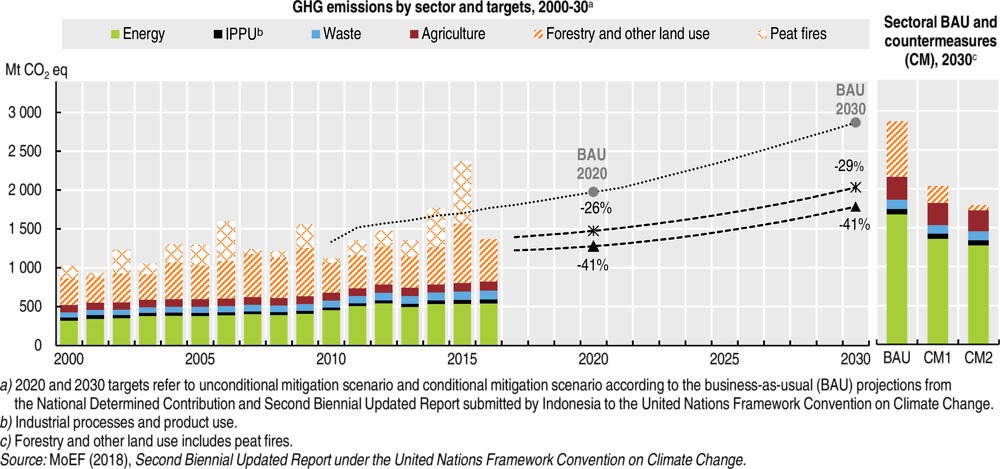

Indonesia plays an important role in meeting the international goal of keeping the global temperature rise to 2°C above pre‑industrial levels. The country is among the world’s ten largest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitters (WRI, 2018). Its emission intensity is nearly twice the OECD average.1 Indonesia’s GHG emissions, including land use, land‑use change and forestry (LULUCF), have risen by 42% since the turn of the century and are projected to grow even faster over the next 15 years under a business-as-usual (BAU) scenario (Figure 1) (MoEF, 2018a). This increase was driven by rising emissions from the energy and land‑use sectors. Land‑based emissions, mostly from forest and peat fires (Section 4), account for nearly half of total GHG emissions.

In 2009, Indonesia voluntarily pledged to reduce emissions by 26% from a BAU scenario by 2020 (and up to 41% conditional on international support). This was followed by a commitment to reduce emissions by 29% below BAU by 2030 (and up to 41% conditional on international support) in its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC). The government has reported that Indonesia is on track to meet its 2020 target. At the same time, it acknowledged that more effort was needed to bring emissions from forestry and energy on track with the 2030 target (MENKO, 2018). Indonesia is yet to commit to a long‑term emission reduction target beyond 2030, as called for in the Paris Agreement. The development of emission scenarios for beyond 2030 has, however, started.

Figure 1. Indonesia needs to accelerate climate action to achieve its 2030 mitigation targets

Most GHG emission reductions are expected to come from cuts in land-based emissions. Indonesia has made considerable progress in addressing such emissions, including through updated forest and peat regulations (such as a moratorium on new land use change permits on peatland and new regulations on peatland protection and management), establishment of the Peatland Restoration Agency, better law enforcement, social forestry programmes and efforts to control and prevent fires (Section 4). Thanks to such initiatives, the forestry sector was the biggest contributor to emission reduction in 2016 and 2017. Still, the target is ambitious (reaching close to zero net emissions in 2030 under the 41%‑reduction scenario) and will require continued improvement in forest governance and compliance with land‑use regulations.

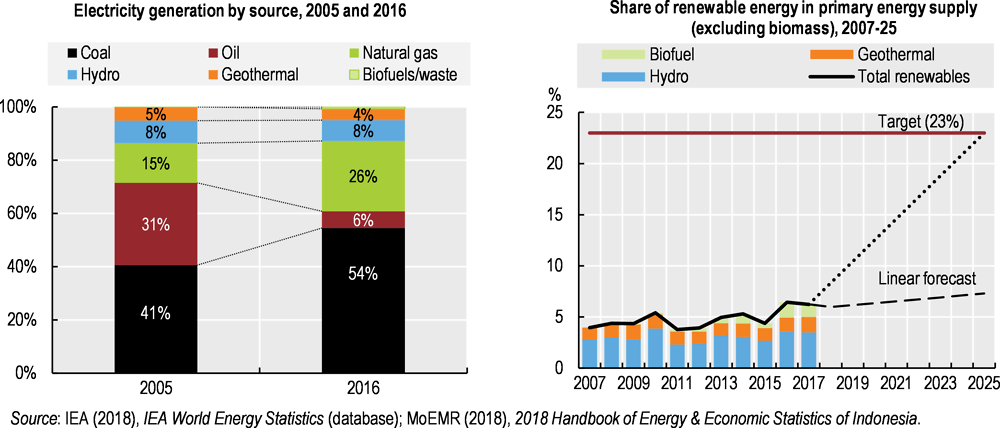

Efforts to decarbonise the energy sector need to be accelerated. Energy demand is growing rapidly as GDP, the population, living standards and energy access all increase. The energy supply heavily relies on fossil fuels, and GHG emissions from the sector are projected to more than double by 2030, even in the most ambitious reduction scenario (Figure 1). Indonesia is one of the world’s largest coal producers, and generates more than half its power from coal (Figure 2). This, combined with the fact that most plants use low‑efficiency technology, makes Indonesia’s power sector one of the most carbon-intense (IEA, 2018). While an increasing number of countries have committed to phase out unabated coal,2 Indonesia’s 2014 National Energy Policy envisages nearly doubling its use by 2025 (compared to 2015 levels) to achieve affordable electricity supply for all. This puts coherence with climate change objectives into question and creates a risk of stranded assets at large scale. While the government supports the development of renewables (Section 3), they need to expand much faster to meet the target of 23% of energy supply by 2025 (Figure 2). The government plans to review its energy policy to reconcile the energy security and low‑carbon development objectives.

Figure 2. The expansion of renewable energy sources has been slow

The overarching framework for Indonesia’s climate strategy is the National Action Plan for Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions (RAN‑GRK), adopted in 2011 to implement its 2009 voluntary mitigation pledge. The NDC sets the post-2020 framework. An inter‑ministerial committee headed by the president was created to co‑ordinate climate action, but was later merged with the REDD+ agency to become a permanent directorate general in the MoEF to make co‑ordination of climate change policies more effective. All provinces have developed action plans for reducing GHG emissions.

The government is reviewing the RAN‑GRK in the context of the new 2030 commitment made under the NDC. It plans to align all sector mitigation targets with broader development objectives under the next medium‑term national development plan for 2020‑24, under the Low Carbon Development Indonesia initiative. This is complemented by initiatives to strengthen green budgeting and climate finance (Section 3). Continued efforts are needed to strengthen Indonesia’s national carbon accounting system in order to build a strong monitoring, reporting and verification system that would allow Indonesia to track progress and evaluate the effectiveness of climate policies. This includes improving the calculation of GHG emissions, the annual baseline and sector reduction targets (MENKO, 2018). Efforts are also needed to synchronise and improve the quality of provincial GHG emission data. In addition, the government plans to introduce an emission intensity target to better track the balance among economic, social and environmental objectives under the low‑carbon development initiative.

Indonesia’s geographical and socio‑economic conditions make it very vulnerable to natural disasters, including extreme weather and climate change (MoEF, 2017). The OECD projects that overall climate change damage will reach about 2.3% of GDP by 2060. The National Action Plan for Climate Change Adaptation (RAN‑API), adopted in 2014, is under review. Development of provincial action plans has been slow, with only 8 out of 34 provinces having adopted one by 2018. In 2016, the MoEF issued a ministerial regulation providing guidance for the formulation of local adaptation action plans. A vulnerability index is being prepared and could inform the development of a comprehensive evidence-based strategy including milestones that can be monitored and broken down subnationally. Nearly 2 000 villages have participated in the government’s Climate Village Programme, adopted in 2012, which aims to enhance communities’ resilience to climate change impacts and reduce their GHG footprint by promoting low-carbon lifestyles.

Developing a comprehensive strategy to address air pollution

According to OECD data, 95% of the population was exposed to harmful levels of air pollution (above the WHO guideline value) in 2017 (OECD, 2018a). Air pollution caused an estimated 215 deaths per million inhabitants in 2017 (OECD, 2018a). Transport, coal‑fired power generation and waste burning are major sources of pollution. Forest and peat fires have been driving year-to-year variability and pollution peaks across Indonesia and neighbouring Malaysia and Singapore, although efforts to reduce fires have started to bear fruit (Section 4). National data on ambient air quality are based on small samples, but efforts are under way to install continuous monitoring equipment in all major cities (to reach 40 cities in late 2018). A new electronic environmental reporting system for industrial facilities should broaden data collection on air emissions and could, in the medium term, help in the establishment of a comprehensive air emissions inventory.

Policy efforts to improve air quality focused on reducing industrial emissions and promoting sustainable urban transport. In 2017, the MoEF signed a long-awaited regulation stipulating Euro 4 emission standards for passenger cars, buses and trucks. Testing and enforcement of existing standards remain a challenge, however. The capital city, Jakarta, is leading the way, stepping up action to test vehicle emissions and better enforce standards. It also holds air quality forums with stakeholders, procures waste management trucks running on natural gas and restricts vehicle circulation through an odd-even system and car-free days, in addition to expanding public transport and electronic road pricing on highways. These measures will bring valuable lessons for other cities and provinces. National emission standards for the cement industry were raised in 2017. Standards for coal-fired power plants and the pulp and paper industry remain significantly less stringent than international standards. The government plans to introduce stricter standards for coal-fired power plants in 2019.

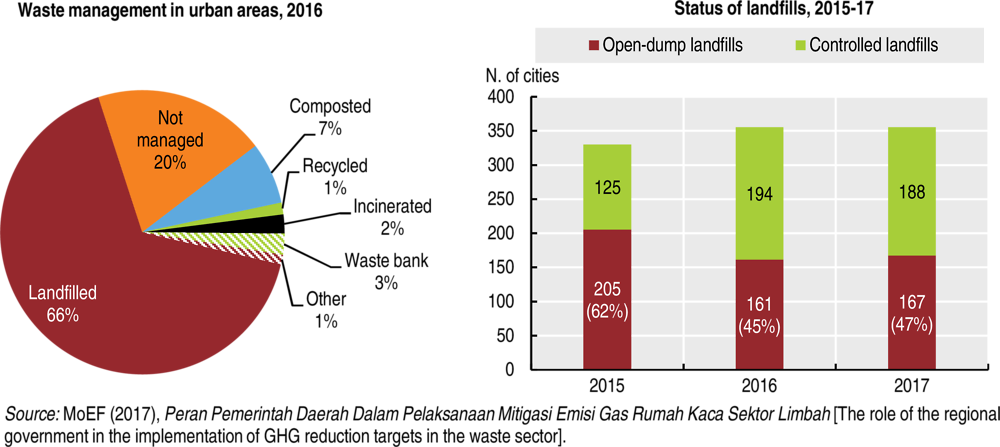

Narrowing the gap between legal waste provisions and actual practice

Indonesia has a good legal basis for waste management. The 2008 National Solid Waste Act calls for sound waste handling (collection, transport and landfilling) based on the “3R principle” (reduce, reuse and recycle) and mandates implementation of waste segregation. However, more effort is needed to close the gap between legal provisions and actual practices. On average, 30% of solid waste is not collected and managed. Several areas lack public waste service. Collected waste mainly ends up in landfills, nearly half of which are uncontrolled open dumps (although the number is decreasing) (Figure 3). The associated contamination of soil, air and water has severe environmental, economic and public health consequences that go beyond boarders. Indonesia is a major contributor to plastic marine debris, largely due to improperly disposed waste from land.

The government is stepping up efforts to address these challenges. The National Solid Waste Management Policy and Strategy aims to reduce 30% of waste by 2025 and properly manage the remainder. It requires local authorities to develop waste management strategies for 2025 (less than half of cities and regencies have waste strategies) and to regularly report on progress. Capacity building will be needed to help local governments develop achievable plans linked to local budgets and sustainable financing and investment strategies. The central government provides funding for waste infrastructure (such as sanitary landfills), but local capacity constraints have meant that facilities turned into open dumps over time. Improving information collection and statistics will be important for informing policy making and tracking progress.

Figure 3. Waste is mostly landfilled, and half of landfills are not environmentally sound

Waste banks (where people trade their waste against small amounts of money) have proved to be an innovative and effective tool to speed up the improvement of municipal waste services. With support from the national and provincial governments, almost 7 500 banks had been created across the country by early 2019, handling 2% of waste generated nationally. The banks are helping to raise public awareness and to promote waste segregation and the development of recycling capacity. They also generate socio-economic value by creating job opportunities and engaging the large workforce that is involved in informal recycling. Several successful pilot projects focus on improving local waste management. The challenge is to improve the situation at scale.

A recent decision by the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”) and other countries to restrict waste imports may increase waste flows to Indonesia (whose law allows for the import of a limited amount of non-hazardous plastic waste), presenting an opportunity to strengthen local markets, but also accentuating the need to scale up environmentally sound waste treatment facilities. Dedicating more resources to inspections, improving the permitting system (e.g. through stronger reporting obligations for operators handling waste) and setting administrative fines for unlawful practices could help strengthen enforcement. The MoEF is preparing a draft regulation on the development of a ten-year roadmap for extended producer responsibility programmes. Following good results from a pilot project, Indonesia also plans to introduce an excise tax on plastic bags. These plans should be speeded up and complemented by extended producer responsibility programmes for waste posing high risk to the environment, such as batteries, tyres and electronic waste. Involving the informal sector in such programmes and in the broader recycling infrastructure will be a critical success factor.

Developing a national inventory of hazardous waste and chemical substances

More attention needs to be given to hazardous waste management. Indonesia has only one private engineered hazardous waste landfill (located in West Java). Most hazardous waste is temporarily stored by industries on site, subject to licensing provisions under the 2009 Environmental Protection and Management Law. Verification of storage conditions has been challenging due to a general lack of resources, and it is unclear what happens to the waste once the storage permit expires (MoEF, 2015a; MoEF, 2015b). Knowledge on hazardous waste management has improved (the number of companies monitored rose from 39 to 295 over 2012‑16), but continued improvement is needed. Additional hazardous waste treatment infrastructure in other parts of the country could facilitate proper management. The government has increased resources to control medical waste from hospitals, which is often disposed of in municipal landfills, and has built the country’s first medical waste incinerator in South Sulawesi province.

Indonesia has ratified all major international chemical conventions. As the chemical sector plays an increasingly important role in the economy, there is a need to improve data on chemicals. For example, data on the production of chemicals in Indonesia are limited. Also lacking are a comprehensive assessment of existing chemicals and data on pollutant releases. Regulations address only a small subset of hazardous substances among what likely amounts to thousands of chemicals used in the Indonesian market, and information requirements are limited (e.g. one-time registration and provision of a safety data sheet). There appears to be a need for a stronger regulatory framework that would allow for development of an inventory of chemical substances manufactured or imported in Indonesia. This in turn, in the medium term, would allow Indonesia to address pressures, carry out systematic investigation and undertake risk management of chemicals.

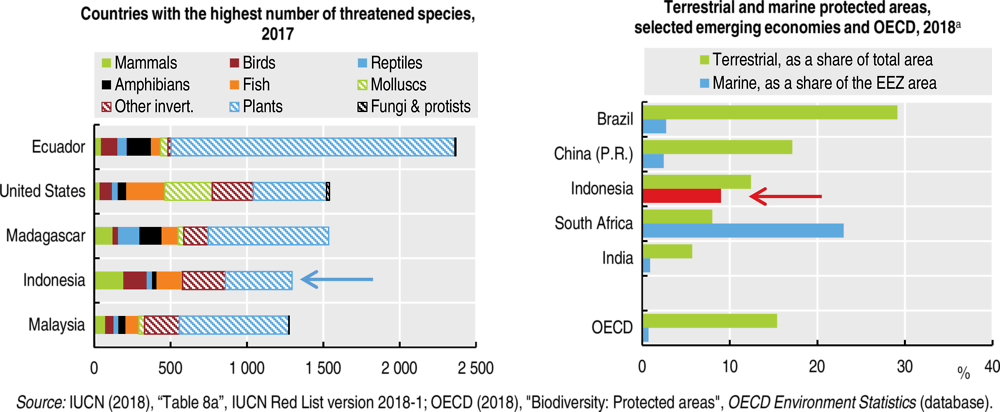

Accelerating implementation of the biodiversity strategy

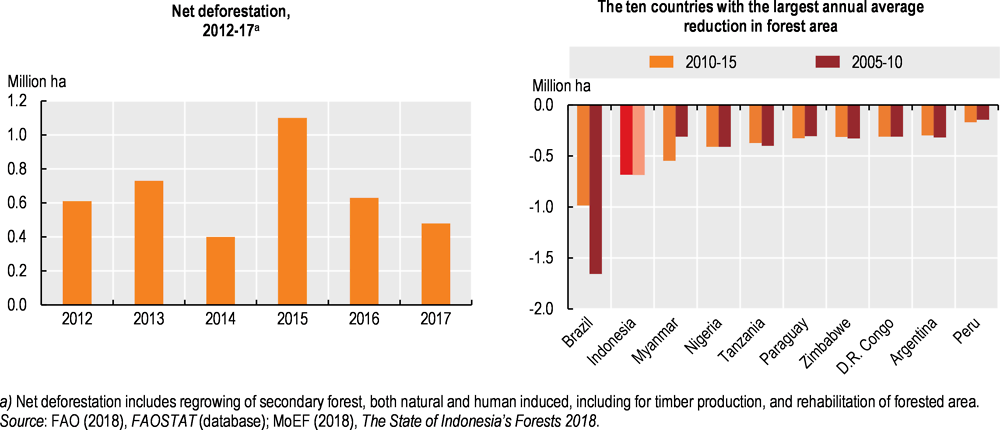

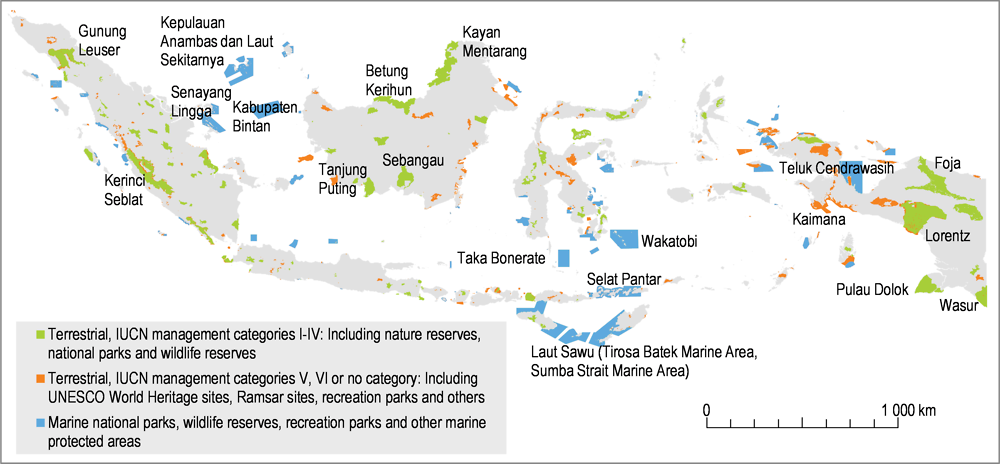

Indonesia is globally important as a centre for biodiversity. It is home to one of the world’s largest tropical forests, some 10‑15% of global flora and fauna species and some 18% of global coral reefs and mangrove habitats (CBD, 2018; Dirhamsyah, 2016). Its ecosystems face significant pressures from habitat loss due to deforestation and forest degradation, pollution, overexploitation, including for wildlife trafficking, invasive alien species and climate change (MoEF, 2014). Indonesia has lost 7% of its forests since 2005, the second largest area in absolute terms, after Brazil (FAO, 2018). In addition, it registers one of the highest rates of species decline worldwide (Waldron et al., 2017). Terrestrial and marine protected areas covered 12% of land and 2.8% of marine area, below the respective targets of 17% and 10% (Figure 4), and effective management remains a challenge. Additional land is protected in “protection forests”, “essential ecosystem areas” and “high conservation value forests” (Section 4).

The Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan 2015‑20 aims to address some key challenges for effective conservation, such as weak monitoring and evaluation at local level, insufficient human capacity, low political priority and lack of stakeholder participation (MoEF, 2014). The government is partnering with local communities to enhance effective management. Developing eco-tourism could be another means of expanding and better resourcing protected areas (OECD, 2018b). The national list of protected species was recently updated to more than 900 species, and 272 monitoring stations have been set up to monitor 25 priority species with a view to increasing their population by 10%. Indonesia has also strengthened efforts to combat illegal wildlife trafficking.

Figure 4. Protected areas could be expanded

Improving monitoring of groundwater levels and enforcement of permits

Freshwater resources are abundant, but unequal distribution, growing water demand and poor management are creating water stress in some areas. Land‑use change (notably deforestation) is contributing to both water stress and flood risk, which are projected to increase under continued urbanisation, economic growth and climate change. Indonesia seeks to achieve water security through watershed restoration and conservation and development of reservoir and irrigation networks.

Indonesia is one of the ten largest groundwater‑consuming countries (ADB, 2016a). Limited water supply infrastructure and polluted surface water have forced households and businesses to rely on groundwater. Large users must have an extraction permit, but awareness and enforcement of this requirement are often low. Illegal wells are common, and industrial water abstraction is not monitored (OECD, 2016). In a welcome step, the Jakarta government has announced to plans improve enforcement action for high-rise buildings. Small water providers (e.g. small-scale commercial or community-based groups) are not regulated. Given their overall number, the lack of regulation may threaten the sustainability of groundwater management in the long term. Over-extraction of groundwater has had wide-ranging consequences, including infiltration of saltwater and land subsidence (e.g. in Jakarta, Semarang and Bandung).

Expanding and improving sanitation facilities to reduce water pollution

Freshwater quality is poor and has declined over the past decade. Half of the rivers of Java, the most populated island, are considered polluted or heavily polluted. Wastewater from households (untreated domestic sewage) is the main source of water pollution, followed by solid waste disposal, industrial effluent, mining, agriculture and urban run-off. Monitoring on wastewater effluent is generally weak, but it is estimated that just 14% of wastewater is treated (OECD, 2016; ADB, 2016b). Various policy initiatives to reduce pollution discharge have achieved encouraging results, but their scale has been too small to significantly improve quality of the targeted rivers (MoEF, 2016a).

Access to improved water and sanitation has increased, although access rates are still low compared to other Southeast Asian countries. The government’s indicative target is to reach 90% access to improved sanitation (including 20% safely managed sanitation) and 75% access to improved water by 2024. Promoting off-grid technology (septic tanks, decentralised sanitation), improving quality of septic tanks and supporting investment in small‑scale projects may be the best way forward, with investment in piped infrastructure being part of the solution in the medium to longer term. Continued efforts are needed to enhance the capacity of regulators and water suppliers at the local level. Treating wastewater is especially key since reclaimed water can be an alternative to groundwater, thus limiting depletion. Developing comprehensive strategies and policies for urban water supply, sanitation and urban wastewater management at the national and subnational levels would greatly aid in achieving targets in this sector.

Box 1. Recommendations on climate change, air, waste, water and environmental information

Climate change

Continue to develop a national climate change strategy under the Low Carbon Development Indonesia initiative to address the 2030 target and beyond. Integrate the 2030 target into the national development plan for 2020‑24 (as planned) and ensure that the long-term goals are broken down into short-term goals and clear responsibilities among actors. Strengthen capacity for assessing mitigation options, including their economic, environmental and social impact.

Continue to improve the quality of GHG emission data (both sectoral and provincial), annual baselines and sectoral mitigation targets in order to establish a credible reference making it possible to track progress and assess the effectiveness of climate policies.

Revise national energy policy to ensure consistency with climate change policy. Guide the energy transition through an emission reduction goal for the power sector, supported by market‑based instruments, to reduce its carbon intensity (e.g. through carbon pricing). Ensure that any new coal power plants are high-efficiency plants, that existing plants are refurbished and that the most inefficient plants are phased out. Plan for halting investment in unabated coal by 2030.

Air management

Continue to develop air quality monitoring systems. Expand information on air emissions from stationary sources and start to systematically collect data on emissions from mobile sources. Make the data publicly available and, in the medium term, work towards establishment of a national air emission inventory.

Develop a comprehensive and integrated strategy to address air pollution that covers all major pollution sources, with priority actions including i) updating emission standards for heavily polluting sectors such as coal-fired electricity generation and pulp and paper; ii) strengthening and enforcing vehicle emission and fuel quality standards; iii) promoting vehicle electrification, notably for motorcycles; v) protecting and investing in natural capital that contributes to the ecosystem service of air filtration; and iv) ensuring effective implementation of local clean air programmes in areas regularly exceeding air quality standards.

Waste management

Accelerate efforts to expand formal waste collection services to reach 100% of the population. Phase out open dumps and ensure that landfills meet environmental standards. Increase investment in waste disposal capacity, in line with projected future demand, and ensure that new infrastructure captures GHG emissions.

Formalise waste sorting and recycling, for instance through continued involvement of the informal sector in waste banks and by providing training and social empowerment (e.g. through co‑operatives).

Implement extended producer responsibility programmes for the most harmful and abundant products to limit the need for new disposal capacity, and reduce the environmental and health problems associated with improper management of dangerous waste. Consider supporting the construction of hazardous waste treatment infrastructure to cover eastern Indonesia.

Chemical management

Strengthen the legal framework for the management of industrial chemicals in order to create a national inventory of chemicals and provide authority for systematic assessment and management of chemicals as information evolves. Improve the monitoring of chemicals in the environment.

Water management

Implement integrated urban water management to enhance water safety. Expand piped water services to increase access to safe drinking water and reduce groundwater use. Enhance capacity of regulators and water supply providers, including for monitoring of groundwater levels and enforcement of permits. Develop long-term strategies to ensure water security for areas where water stress is projected to intensify, taking into account nature-based solutions.

Improve monitoring of water pollution and enhance pollution prevention and mitigation. Continue to expand and improve sanitation facilities by promoting off‑grid technology, faecal sludge management systems, investment in small‑scale projects and expansion of centralised sewerage networks in metropolitan areas, taking into account possible use of reclaimed water as an alternative to groundwater to limit depletion.

Information and education

Continue to undertake public communication campaigns to raise public awareness about the state of the environment. Foster environmental education to enhance understanding of the environmental, economic and health risks associated with pollution and environmental degradation. Further develop environmental education in school curricula.

Revive regular publication of the State of the Environment Report and consider establishing a green growth monitoring and reporting framework linking economic activity with environmental performance.

2. Environmental governance and management

Decentralised governance in need of better co-ordination

Since 2001, Indonesia has undergone far‑reaching political, administrative and fiscal decentralisation. As a result of this reform, provincial and local governments have gained more authority to manage their natural resources. There has been a significant increase in numbers of provincial and local regulations and policies. The 2014 Law on Local Government strengthened provinces’ role in development, spatial planning and land administration. However, environmental management at the provincial and local levels is inconsistent due to differences in institutional capacity. The 2009 Law on Environmental Protection and Management increased the power of the environment ministry to oversee compliance monitoring and enforcement activities by provincial and local governments. This led to interventions against wastewater disposal in the Citarum watershed and closure of illegal mines in Gunung Botak, for example. Since 2015, the MoEF has increasingly used such “second-line” enforcement.

The MoEF was formed in 2015 by a merger of the environment and forestry ministries. Indonesia’s environmental legislation is primarily sector-based, with several other ministries having important environmental responsibilities. The MoEF’s powers are more limited than those of sector ministries, and it lacks financial and human resources to fully exercise its mandate. Four so-called co‑ordinating ministries strive to address policy development fragmentation. Nevertheless, environmental management, particularly permitting and compliance assurance, often involves overlapping interests and institutional conflicts. Some regions have initiated inter-jurisdiction collaboration on environmental matters at the local level to help disseminate good practices and build capacity.

Building technical capacity for environmental assessment

Environmental impact assessment (EIA) is the backbone of the country’s environmental regulation. It is undertaken primarily at the local and provincial levels. Its use has improved in recent years due to stricter regulatory requirements and better guidance. However, many projects are still approved without appropriate EIA. In 2018, a practice of issuing provisional business licences through an online platform before the EIA is completed was introduced, which compromises consideration of alternatives in the EIA process. While there has been some progress, EIA documents still tend to be of low quality and overlook important potential environmental effects, and many authorities lack capacity for adequate assessment. EIA provides a key opportunity for public participation, but in practice it remains limited.

If an activity does not require EIA, the operator must submit an Environmental Management and Monitoring Program (EMMP) document or an even less onerous statement. These documents are usually very general, and local authorities review them only superficially. EIA or EMMP approval results in issuance of an environmental permit that does not cover wastewater discharges or waste management, which are governed by separate permits. Environmental permits rarely contain limits on polluting activities, are valid indefinitely and are not subject to periodic review (Sano, 2016).

Strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is increasingly used for spatial plans at the provincial and local levels, for some national and sector policies and, most recently, for national and local development plans. SEA is hindered by limited stakeholder and public involvement, limited technical capacity and insufficient monitoring and follow-up. Technical guidelines for SEA implementation are under development.

Data gaps and weak sanctions impede compliance assurance

Strengthening the enforcement of environmental and forestry legislation is a priority of the MoEF. Compliance monitoring and enforcement are hampered by low institutional capacity. Inspections are mostly reactive, responding to accidents, complaints and third-party reports of non-compliance. There are no systematic data on the regulated community, its compliance behaviour or enforcement sanctions. Enforcement approaches vary by jurisdiction and sanctions are inconsistently applied. Written warnings and compliance orders are by far the most used enforcement tool. The only administrative monetary penalties are fines for ignoring compliance orders. Despite an ongoing environmental certification programme for judges, criminal enforcement is limited by judicial capacity and procedural constraints (Sembiring, 2017).

The environmental liability regime is enshrined in law but its implementation started only recently, in the forestry sector. A requirement for operators to furnish guarantee funds to pay for eventual remediation of environmental damage exists but has not yet been put into practice, although progress has been made with the adoption of regulations on environmental economic instruments (in 2017) and an environmental fund (in 2018). The problem of contaminated sites for which no responsible party can be identified is particularly acute: district governments are meant to identify, assess and report them, but lack resources and political will to do so. The national government is only starting to compile an inventory of contaminated sites and has no programme or set of norms guiding remediation. Better use of technology can help trace the source of contamination and pursue responsible parties.

Efforts to promote green business practices are expanding. The number of, and adherence to, environmental certifications is low but rapidly rising. Special initiatives, such as the Green Industry Award and Green Industry Certification, encourage the greening of industrial performance. The government plans to introduce sustainable public procurement criteria over the course of 2021 and 2022. Almost 2 000 companies participate in the Program for Pollution Control, Evaluation, and Rating (PROPER), a voluntary, colour-coded rating system grading factories’ environmental performance against regulatory standards. However, just 6% of large industrial enterprises participate. PROPER has considerable potential as a compliance promotion programme. Disclosing the data underlying a rating (e.g. on emissions or effluents) would enhance transparency. A facility’s PROPER-related evaluation does not systematically entail enforcement measures in cases of serious non-compliance, however (Sembiring, 2017).

Box 2. Recommendations on environmental governance and management

Create formal mechanisms of horizontal and vertical co-ordination on environmental matters; expand MoEF oversight on provincial and local environmental policy implementation to cover SEA, EIA and permitting.

Build capacity of provincial and district authorities in SEA, EIA and environmental permitting; ensure consideration of alternatives in environmental assessment; integrate wastewater discharge and hazardous waste storage permits into environmental ones, and ensure their periodic review as well as regular self-reporting of permitted businesses.

Introduce administrative fines for non-criminal offences and provide detailed and uniform guidance to inspectors and the police on the use of enforcement tools; build judicial capacity to handle environmental cases.

Implement the system of financial guarantees from businesses to constitute funds for remediation of damage to soil, water bodies and ecosystems; compile a nationwide inventory of contaminated sites and design a programme for their gradual remediation in collaboration with provincial and district governments; adopt technical standards and guidelines for environmental remediation.

Improve disclosure of information about industrial environmental performance (e.g. on emissions of air pollutants and wastewater effluent collected through PROPER) and, in the medium term, work towards setting up a pollutant release and transfer register.

3. Towards green growth

Indonesia expresses a strong commitment to sustainable development and has integrated green growth elements, as well as most Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), into its national development planning framework. The 2015‑19 National Medium-Term Development Plan (RPJMN) contains targets to improve environmental quality, incorporates the climate change mitigation targets to 2020 and acknowledges the need to manage natural resources sustainably. However, conflicting sector development goals and policies, along with challenges in policy co‑ordination, have meant that pressures on the natural asset base have continued to increase. Difficulties in implementing and enforcing environmental legislation are compounding these issues.

Concerns about the economic and social impact of environmental degradation have stimulated efforts to more effectively integrate environmental considerations into development planning. The Low Carbon Development Indonesia initiative highlights remarkable efforts to build modelling capacity and strengthen the evidence base on economy-environment links. The plan will, for the first time, reflect the contribution of the environment to the economy and the impact of the economy on the environment. It will provide an opportunity to explicitly identify and resolve conflicting sector policy objectives and to align infrastructure investment plans and fiscal reform with long-term sustainable development strategies. Low-carbon policy scenarios will become major inputs to the 2020‑24 RPJMN. Achieving green growth goals will require more effective co‑ordination across ministries and levels of government. A specific monitoring framework on key green growth objectives could help increase transparency and allow evaluation of policies’ effectiveness.

Using market-based incentives to support the green economy transition

The transition to a greener economy requires stronger market-based incentives. Revenue from environmentally related taxes in 2016 reached 0.8% of GDP, a relatively low value compared to most OECD and G20 countries. Most of the revenue stems from vehicle taxation, while in most OECD and G20 countries, a majority comes from transport fuel taxes. Overall, the tax system does not capture the cost of environmental damage and lacks alignment with environmental objectives and the polluter-pays principle. Government Regulation No. 46/2017 on environmental economic instruments, expected to be fully implemented by 2020, aims to reconsider and expand the use of taxes for environmental purposes.

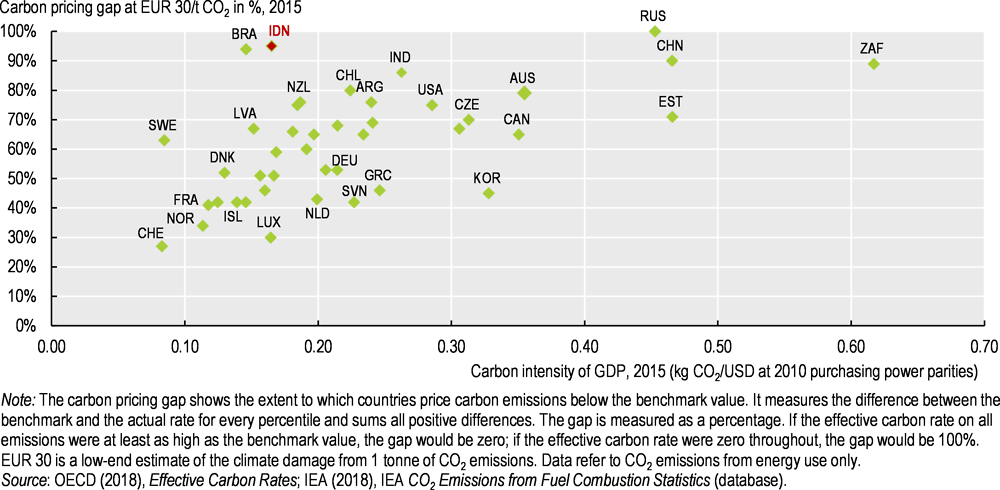

Moving towards cost-reflective pricing in the energy sector

A major opportunity for better use of prices for the green growth transition lies in the energy sector. Bringing energy prices closer to their true environmental, social and economic cost is a crucial step if Indonesia is to meet its energy security and sustainability goals. Currently, energy prices in Indonesia are well below their true costs owing to a combination of low energy taxes and energy subsidies. Only two low-level energy taxes are in place at subnational levels: a regional motor vehicle fuel tax and a local street lighting tax. Hence, 84% of CO2 emissions from energy use are unpriced. The fuel tax, an excise tax that is capped by national regulation at 5% of the sale price, is low by international standards. It amounts to an average effective tax of EUR 7.6 per tonne of CO2 emitted from fuel consumption in transport, much lower than the rates in India (EUR 49/t CO2), China (EUR 70/t CO2) or South Africa (EUR 95/t CO2) (OECD, 2018c). Indonesia’s carbon pricing gap is thus one of the largest among OECD and partner countries (Figure 5). The government is revising the national regulation to enable subnational governments to increase the fuel tax rate. Efforts are also under way to reduce fuel subsidies by using a more targeted mechanism.

Figure 5. The effective price on carbon is low

The government began considering a carbon tax in 2009, but little progress has been made since. A 2009 Green Paper on Climate Change proposed introducing a tax amounting to USD 10/t CO2 on fossil‑fuel combustion for electricity generation and large industrial installations as of 2014. In line with international best practice, the suggestion was to gradually increase the rate (by 5% per year to 2020) and to use part of the revenue to alleviate the impact of higher prices on the poor and on vulnerable communities. It was estimated that the tax would reduce CO2 emissions from fossil‑fuel combustion by 10% compared to BAU by 2020 without negatively affecting growth or poverty reduction aspirations. No legislation has been introduced to impose the tax. However, Presidential Regulation No. 77/2018 provides a legal framework for the establishment of a carbon market. Indonesia should continue to pursue options for pricing carbon emissions. OECD research shows that the EU Emissions Trading System has effectively reduced emissions without harming firms’ competitiveness (Dechezleprêtre, Nachtigall and Venmans, 2018).

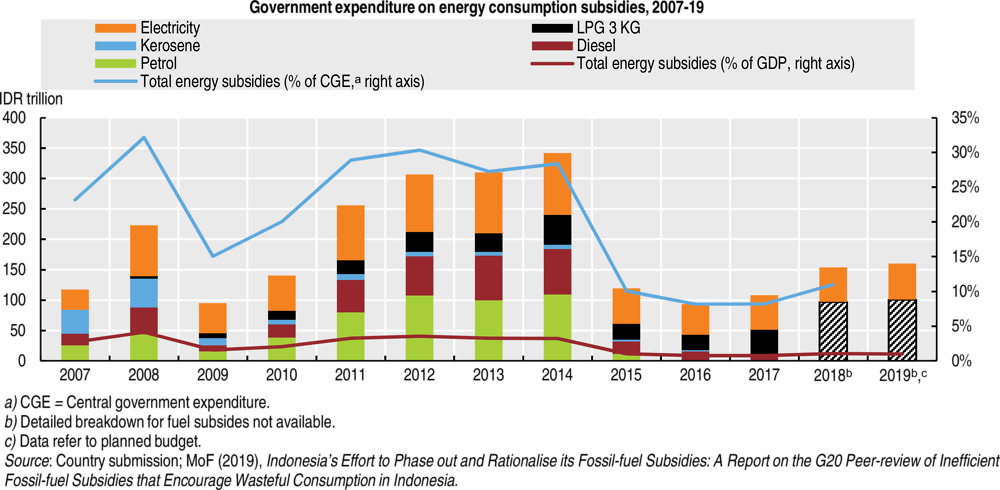

Continuing to phase out fossil-fuel subsidies

Much progress has been made in reducing subsidies to fossil‑fuel consumption. Indonesia has a long history of subsidising end-user prices for petrol, diesel, electricity and other energy products to keep energy affordable for the poor, increase energy access and raise household purchasing power (private consumption contributes more than half of GDP). Until 2014, consumption subsidies amounted to about 30% of government expenditure, equal to nearly 4% of GDP. Pressured by an increasingly large fiscal burden, the government has embarked on major reforms, linking domestic transport fuel prices to international prices and better targeting electricity subsidies to needy households. This helped cut subsidy expenditure by roughly half between 2014 and 2015 alone (Figure 6), freeing resources for infrastructure and social development. Subsidies to fossil fuel-producing industries are estimated to be considerable, but considered necessary to maintain the purchasing power of low-income groups. Indonesia’s engagement in international forums, including through participation in a peer review on fossil-fuel subsidy reform under the auspices of the G20, helped shed light on the subsidies (OECD, 2018d).

Figure 6. Fossil-fuel subsidies have dropped

While energy consumption support dropped markedly, not all price reforms have been implemented as announced, putting into question the stability and durability of reform. Subsidies to petrol (RON 88) were officially abolished in 2015, yet domestic prices have not been adjusted to rising global oil prices since mid‑2016. In March 2018, the president announced that petrol and electricity prices would be kept stable until at least the end of 2019 to ensure affordable energy for poor households, and diesel subsidies were increased in mid‑2018. In 2017, the government launched the “single fuel price” policy, which aims to harmonise fuel prices and address inequality across the archipelago. It is questionable whether the state-owned petroleum company, Pertamina, will be able to deliver set fuel prices without government subsidies.

Universal, ill-targeted energy subsidies disproportionally benefit wealthier households and therefore are less efficient in addressing poverty and inequality concerns than direct support to vulnerable households. Indonesia should instead rigorously stick to its subsidy reform timetable. Current efforts to better target electricity and liquefied petroleum gas subsidies should continue. In the medium term, subsidies should be replaced with targeted support to the vulnerable via conditional cash and non-cash transfer programmes. Work should continue to systematically track subsidies to fossil‑fuel production.

Aligning vehicle taxation to environmental performance

In addition to fuel pricing, other fiscal measures should be considered to manage the environmental impact of transport. This is becoming a growing concern as the rapidly rising motorisation rate is contributing to air pollution and crippling congestion in cities. The national and some provincial governments have begun to consider environmental dimensions in tax design, for example through a reduced luxury goods tax for so-called low-cost and green cars. Rather than applying exceptions to certain car types, Indonesia could link its main vehicle taxes (e.g. registration and ownership taxes) to parameters such as fuel efficiency and CO2 and local air pollutant emissions – an option the government is already considering. The experiences of Israel and Chile could provide guidance. The World Bank (2018) estimates that better aligning motor vehicle taxes with environmental externalities of vehicle use and transforming the luxury goods tax into a specific excise tax (to avoid transfer pricing) could increase state revenue by 0.64% of GDP. Well-designed traffic congestion pricing can help address congestion while raising revenue for improvement of transport services.

Establishing a commission for comprehensive green fiscal reform

Green fiscal reform can help Indonesia reduce pollution and other environmental externalities cost-effectively, while raising much‑needed revenue for infrastructure and social spending. OECD experience has shown that establishing green fiscal reform committees can help bring consensus among stakeholders, reduce resistance from business and facilitate co‑ordination among government bodies. As part of a broader green fiscal reform, Indonesia should consider introducing taxes on pollution or products causing pollution and waste. The planned introduction of a plastic bag excise tax is a step in the right direction. Other taxes on pollution (including fertiliser, pesticides and wastewater releases) should be considered. Currently, fertiliser use is heavily subsidised. Efforts are under way, however, to better target the subsidy.

Efforts to combat illegal extraction of natural resources, such as timber, fish and metals, and to strengthen land‑use governance and law enforcement should continue. These challenges weigh on tax revenue and create environmental costs. It is estimated that only one-third of potential revenue from Indonesia’s main forestry levies was collected between 2003 and 2014 (KPK, 2015). In addition, Indonesia should consider improving the structure and raising the rates of royalties, especially in the forestry sector, in order to collect full economic rent on natural resource use. While the government increased the forest user fee for mining and plantation companies in 2014, the two most important levies on timber extraction have not been adjusted for nearly two decades, eroding their potential to promote sustainable forestry and to allow the government to capture economic rents on natural resource use. Indonesia’s participation in the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative is driving governance improvements in that sector.

Investment in the green economy is increasing

Public environmental expenditure has declined in recent years, amounting to 0.9% of the central government budget in 2017 (BPS, 2017). The MoEF budget was cut significantly in 2017, forcing the ministry to prioritise high‑impact projects. Subnational spending on the environment varies widely. Initiatives such as a climate change budget tagging system and the Green Planning and Budgeting Strategy are enhancing transparency of environment-related spending and will help the government align national expenditure and revenue processes with climate and other environmental goals. Results show that about 1% of central government expenditure was devoted to green economy investment in 2011‑14 (MoF, 2015). This was below investment needs and also below expenditure on environmentally harmful subsidies for fossil‑fuel consumption (which reached 27% of central government expenditure in 2011‑14). Budget support to the green economy has since increased significantly, reaching 5.4% of the state budget in 2018.

Enhancing incentives for investment in waste, water and sanitation

The government has made it a priority to tackle Indonesia’s infrastructure gaps and significantly increase public spending. This will boost the economy and represents an opportunity to provide much‑needed funding for environment-related infrastructure. Water, sanitation and waste management services remain severely underfunded. Their fees and tariffs are too low to cover the cost of service provision, let alone investment. In response, a special allocation fund has been set up to financially assist local governments in managing their drinking water companies. Strengthening cost recovery will be important to reach the entire population and improve services. This will require higher user fees, for those who can afford to pay; targeted cross-subsidies may be needed to ensure service provision to poorer users. Improving service quality and providing transparency on revenue use will be paramount in securing users’ willingness to pay. At the same time, there is a strong rationale for central government subsidies for basic service delivery in areas currently lacking it.

Implementing the sustainable finance regulation

Private investment in the green economy is nascent, reflecting a lack of demand for green credit and high risk associated with green investment. Indonesia launched its first green sukuk (Islamic bonds) in 2018. It also set up the Tropical Landscapes Finance Facility in 2016 to leverage private long-term finance for projects and companies that stimulate green growth and improve rural livelihoods. The Financial Services Authority has taken steps to enhance financial sector engagement in sustainable growth. A 2017 regulation made Indonesia one of the first countries with regulation on sustainable finance. Continued capacity building will be needed to enhance the understanding and practical application of sustainable financing principles among regulated institutions. In the medium term, the regulation could be used to limit access to finance for businesses operating without an environmental permit (or not complying with it), making it a potentially powerful tool for enforcing environmental law.

Renewables, energy efficiency and sustainable transport are priority areas

Investment in clean energy has been increasing, but remains small relative to investment in oil, gas and coal. At USD 1.6 billion in 2017, investment in renewable energy sources also falls short of the estimated USD 15 billion needed per year to meet the 23% renewables target (IESR, 2017; BNEF, 2018). To encourage investment in renewables, the government has put in place several incentives, but they have not led to investment as hoped, for various reasons. In 2017, feed-in tariffs for renewables were replaced with a mechanism capping tariffs in accordance with average regional electricity generation costs. This makes renewables investment attractive in remote areas, where generation costs are high, but renders renewables projects economically unviable in other parts of the country, especially where most of the population and economic activity are concentrated, or where electricity is oversupplied.

Developing a plan to scale up renewables

The cost of renewables is high in Indonesia, compared with other countries in the region. This makes it hard for renewables to compete with cheap and abundant coal (most of which is low-grade). Investment in the sector is associated with high risk, given political uncertainty (i.e. lack of a long-term carbon price signal), regulatory instability (dozens of regulatory adjustments over 2017), off-take risks, and burdensome and slow licensing and land acquisition processes. The latter have been eased recently, including through the development of an online submission system for permitting. Local‑content requirements further increase costs, at least in the short run. Reducing these risks will require a comprehensive, transparent and achievable plan for renewables development, backed by strong and sustained political commitment.

Continuing improving energy efficiency…

A stronger focus on energy demand management would help avoid the need for expansion of energy supply. Meeting Indonesia’s goal of reducing energy intensity by 1% per year to 2025 would avoid 341 Mt CO2 eq between 2017 and 2025 (IEA, 2017). There is significant scope to improve efficiency further. The government adopted energy efficiency measures, including energy performance standards for lighting, appliances and buildings, as well as energy management requirements for large industry that appear to have lowered its energy intensity. While the private sector has made some effort to raise energy efficiency, for example through PROPER, compliance is not yet comprehensive and some standards are too lax to have a significant effect on the market. Given the substantial economic and environmental benefits of energy efficiency, Indonesia should continue to strengthen and effectively implement energy efficiency measures.

…and investing in public transport infrastructure

Investment in the transport sector is, as in many countries, heavily tilted towards roads. Investment in public transport has increased, in particular through large-scale projects in Jakarta. The government also plans to build urban mass rapid transit systems in more than 20 other cities. Besides public transport investment, Indonesia’s policy to reduce GHG emissions from transport has focused on promotion of biodiesel. Electrification of urban transport (particularly motorcycles) can bring important benefits for urban air quality, although the effect on GHG emissions may be modest, given the carbon intensity of the power sector. The potential for electric vehicles is held back by the lack of a regulatory framework, supporting infrastructure (e.g. charging stations) and supporting policies (e.g. fiscal incentives). A presidential decree on electric vehicles is under development to address these barriers.

Strengthening eco-innovation and green markets

Balancing the focus of energy-related R&D budgets

Indonesia is less R&D-intense than other Southeast Asian countries and fast-growing economies such as India and China (OECD, 2013). However, there is encouraging growth in the number of patent applications for climate change-related technology. Policy action to stimulate innovation is increasing, including through the launch of the Indonesian Science Fund, the country’s first research funding institution, in 2016. In a welcome step, Indonesia pledged to increase the state R&D budget on clean energy ninefold over five years, although with most resources devoted to developing cleaner fossil energy. A greater focus on demand-side management (energy efficiency) would be a good complement to the current focus on the supply side. More technology neutrality in energy R&D funding would help ensure that the most cost-effective technology is pulled into the market (IEA, 2015).

Indonesia’s environmental technology market is among the ten largest in the world, at USD 6.9 billion in 2017 (ITA, 2017). Market barriers remain substantial, however. Even as environment regulations have become more stringent, slow implementation and lack of enforcement limit their effect on demand for environmental goods and services (EGS). In addition, local content requirements and lack of transparency in public tenders hinder foreign investment in the sector. Domestically, continued efforts are needed to build technical skills to implement advanced environmental systems and to improve asset management in public projects. Green public procurement has considerable potential to stimulate demand for, and supply of, EGS in Indonesia, where public procurement already accounts for about 30% of the government budget. The MoEF is co‑ordinating an inter‑ministerial team on preparation of sustainability criteria for public procurement of products and services, as well as list of goods and services meeting the criteria.

Indonesia is among the few countries to have made corporate social responsibility mandatory by law. Several positive initiatives are under way to promote good environmental management by businesses, including development of Green Industry Standards (initially voluntary), a Green Industry Certification Body and a Green Industry Authorization Committee by the Ministry of Industry. PROPER has been the central government’s innovative attempt to incentivise better business practices by ranking companies for performance. It has shown positive results in compliance promotion, but should not be an alternative to enforcement. To amplify the public pressure effect of PROPER ratings, the government needs to invest more in consumers’ environmental awareness, continue to develop strict green public procurement policies and work with investors and banks to limit access to finance for poorly performing companies.

The role of development co‑operation and trade

Indonesia has been among the ten largest recipients of official development assistance (ODA) worldwide in recent years. ODA targeting climate change mitigation has significantly increased since 2011, driven by energy and transport infrastructure projects, while ODA to general environmental protection, agriculture and water and sanitation has declined. The country launched the Indonesia Climate Change Trust Fund in 2010 as its first climate finance institution. While the level of funding has been low, 76 mitigation projects have been financed through the fund. These projects reduced GHG emissions by 9 Mt CO2 eq at relatively low cost (USD 1.5/t CO2 eq). In 2010, Norway pledged USD 1 billion if Indonesia reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. So far, 13% has been disbursed for policy milestones and support to preparatory work. Indonesia is preparing a mechanism to receive international climate finance from Norway and other partners for demonstrated results (Section 4).

With nearly half of exports coming from natural resource-based activities, Indonesia would benefit from the inclusion of environmental provisions in regional trade agreements. Trade and investment restrictions aimed at developing local industry should be carefully reviewed, as these measures pose a heavy burden on imported products and could negatively affect the diffusion of environmental services and technology not supplied domestically. As a member of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation alliance, Indonesia pledged to cut most-favoured nation applied tariffs to 5% or less by 2015 on environment‑friendly goods contained in 54 product categories. Indonesia partly missed the deadline, with a dozen tariff lines or specific products not yet in compliance, but lowered some tariffs in 2017 and announced plans to reduce remaining tariffs gradually by 2021 (ICTSD, 2016).

Continuing to fight illegal wildlife trade

As a member of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, Indonesia has put in place several measures to control wildlife trade. Illegal trade has become one of the main pressures on biodiversity: its volume quadrupled between 2010 and 2017, reaching an estimated value of USD 1.2 billion (Gokkon, 2018). In addition to the growing international market, Indonesia represents a huge domestic market. Strengthening traceability, compliance and enforcement agencies, promoting inter‑agency collaboration and a multi-door approach, raising awareness and closing regulatory loopholes that prevent successful prosecution are important components of stronger law enforcement. Partnering with civil society organisations and using social media channels could facilitate monitoring of wildlife trade.

Box 3. Recommendations on green growth

Framework

Fully follow through with SEA of the 2020-24 RPJMN. Implement the System of Environmental-Economic Accounting Central Framework to properly value the country’s natural capital in economic planning at the national and subnational levels.

Getting prices right

Make better use of environmentally related taxes and charges with a view to better applying the polluter-pays principle. Consider establishing a dedicated commission to develop options and pathways for comprehensive green fiscal reform. Items for reform include:

Moving towards cost-reflective energy pricing (bringing the implicit price of carbon to positive levels) by continuing to phase out fossil-fuel subsidies, while gradually raising the regional fuel tax and expanding energy/carbon taxation to non-road sectors such as industry. Regularly adjust fuel prices to global oil prices and continue to better target electricity and LPG subsidies. In the medium term, replace energy subsidies with cash transfers for poor households. Introduce an explicit carbon price, even if initially very low.

Align vehicle taxation to environmental performance, for example by linking tax rates to fuel efficiency and the emission of CO2 and local air pollutants to encourage the purchase of more fuel-efficient and low-emission vehicles.

Continue to enhance transparency and law enforcement related to forest concessions as well as mining and fishery permits. Review the structure and rates of royalties, especially in the forestry sector, in order to collect full economic rent on natural resource use. Continue efforts to better enforce water abstraction fees.

Introduce the planned plastic bag excise tax. Consider introducing taxes on air pollutants and wastewater discharge.

Reorient agricultural production support away from market price and direct input support towards productivity and income-enhancing investment (e.g. R&D, education, infrastructure, creation of value added, restoring ecosystem services). Replace fertiliser subsidies with more productive and sustainable support programmes for farmers.

Investment

Enhance incentives for investment in waste, water and sanitation by gradually increasing user fees to make service providers more independent, commercially and financially robust and capable of funding capital investment. Poor households should be compensated through existing conditional cash transfer programmes or other social protection programmes. Support local institutions in improving service quality (a prerequisite for ensuring citizens’ willingness to pay) and enhance enforcement capacity.

Continue to build capacity among financial institutions to comply with the sustainable finance regulation and to improve their contribution to financing of climate and green economy-related projects. Explore options on how the regulation could be used to promote compliance with environmental law.

Develop a comprehensive, transparent and achievable plan to scale up renewables, backed by high-level commitment and buy-in from all stakeholders. Remove regulatory barriers and streamline processes for granting permits. Develop mechanisms to reduce the risk premium on finance for renewables (e.g. using guarantees). Work towards a level playing field by phasing out subsidies benefiting coal, oil and natural gas production.

Increase the stringency of energy performance standards (particularly for air conditioning) and enhance enforcement and compliance with energy efficiency regulations.

Develop support measures for adoption of electric vehicles, particularly electric motorcycles.

Environment-related goods and services and innovation

Balance the focus of energy-related R&D budgets under Indonesia’s Mission Innovation commitment to adequately support research on renewables and energy efficiency, in addition to cleaner fossil fuels.

Scale up the Sustainable Consumption and Production programme across ministries; continue to build product certification programmes; consider extending sustainable procurement to smallholders (e.g. those involved in social forestry and agricultural products).

Reform trade barriers such as local content requirements and foreign equity restrictions, which prohibit Indonesia from adopting modern clean energy technology.

Continue to fight illegal wildlife trade, prioritising protection of the most endangered species and partnering with civil society to enhance law enforcement.

4. The land‑use, ecosystems and climate change nexus

Achieving a sustainable land‑use sector is pivotal for green growth

Indonesia’s rich natural resources have enabled continued economic growth and provided livelihoods for millions of people. Land-based activities such as mining, agriculture, forestry and fishing account for 20% of GDP overall, and for more than 50% in the provinces of East Kalimantan, Riau and Papua. The agricultural sector accounts for 30% of employment and represents the main economic activity of roughly half the households living close to forest areas (BPS, 2014). In addition to its economic role, the land has high ecological value as well as strong spiritual, medicinal and cultural significance, particularly for indigenous communities.

Development of natural resources has increased pressure on ecosystems. Continuing conversion of forests, peatlands, mangroves and other ecologically valuable land to agriculture, expansion of industrial timber plantations, urban development, industry, and pollution from mining and agriculture are among the main concerns. Progress has been made with respect to long-standing weaknesses in the enabling environment for land management. They include lack of clarity about land status, inadequate permitting arrangements and insufficient monitoring and enforcement. These issues have contributed to the spread of illegal activities and created incentives to clear primary forest and peatland, which are less likely to be subject to ownership disputes. Achieving a sustainable land‑use sector is pivotal to meet the Paris Agreement targets and the SDGs, and, ultimately, to unleash Indonesia’s full green growth potential.

The government’s perspective on land use increasingly emphasises the need to balance social, environmental and economic developmental values. This is reflected by its commitment to democratise allocation of forestry resources and prevent deforestation and forest degradation. Balancing the three values will require greater policy consistency, institutional strengthening and capacity development. In particular, there is a need to better align the legal classification of land with its physical characteristics, combined with strengthened enforcement efforts to ensure that policy goals are realised in practice.

Deforestation rates are decreasing, but remain high

Indonesia’s forest cover has continued to decline since 2005, despite the introduction of strengthened policies to combat deforestation. However, deforestation rates have decreased considerably since a peak in 2015 (Figure 7). While there is limited quantitative information on the drivers of deforestation, expansion of agricultural production into forests is a particular concern. Growth in production of some commodities, notably palm oil, has mainly been achieved by expansion of planted areas. Rapid expansion of industrial timber concessions has also increased use of primary forest and peatland. The islands of Sumatra and Kalimantan, where oil palm and timber plantation has been highest, registered the most forest loss over the past decade. Illegal activities are likely to be a driver of deforestation.

Figure 7. Deforestation has declined since 2015, but remains high

Peat fires and peat decomposition are driving GHG emissions

Land conversion and fires involved in that process are a significant source of GHG emissions. While emissions vary significantly from year to year, the land‑use sector accounted for about half of Indonesia’s total GHG emissions over the past decade (Figure 1) (MoEF, 2018a). The majority of emissions stem from drainage or burning of peatlands (Figure 8), which is both rich in carbon and subject to extensive land‑use change. Peatlands are drained and set aflame for clearing. Peatland drainage leads to direct emissions as the peat decomposes until the carbon stock has been released. Dried peatland is combustible and the fires are hard to extinguish, meaning land can burn for weeks, particularly in dry years. In 2015, a notably dry year, peat fires emitted 800 Mt CO2 eq (MoEF, 2016b), 33% of Indonesia’s total GHG emissions. The economic and health costs associated with the fires were estimated at USD 16 billion (World Bank, 2016).

Intact natural forests are essential for sustaining ecosystem services

The sustainable management of Indonesia’s forest and peatlands is of global importance. Indonesia is one of the world’s most biodiverse countries, but also home to two of its 25 biodiversity hotspots. Land‑use change, notably deforestation, and pollution from agriculture and mining have reduced biodiversity and hindered the functioning of ecosystem services. For example, 14% of Indonesia’s watersheds are in a critical state, largely due to land-based sectors’ activities, increasing flood frequency in downstream communities (BPS, 2014). Around one-third of birds and nearly half of mammals in peat swamp forest are endangered (Posa, Wijedasa and Corlett, 2011). Habitat loss included replacement of natural habitats with monoculture plantations, which support lower species diversity than natural forest and attract pests that affect surrounding habitats and plantations (Petrenko, Paltseva and Searle, 2016; Meijaard et al., 2018).

Figure 8. Peat decomposition and fires are the main sources of land-based emissions

Coherence between policy objectives could be improved

Indonesia has made a number of national-level commitments with implications for land use. For example, actions in the LULUCF sector are expected to deliver more than half the GHG emission reductions in the NDC. At the same time, land management is expected to support food security, agricultural production, access to land for the poor, energy security and protection of Indonesia’s rich biodiversity, along with contributing to sustained economic growth. The 2015‑19 RPJMN explicitly recognised the importance of sustainable development and the role of spatial planning, and adopted targets from the NDC and the RAN-API. The elaboration of sector targets in the RPJMN, however, does not appear to have fully considered interaction between objectives, particularly given competition for finite land (Bellfield et al., 2017).

The 2020‑24 RPJMN provides an opportunity to support greater alignment of sector targets affecting land use. Setting credible land‑use targets, combined with strengthened enforcement and technical assistance for smallholders, could help provide longer-term clarity. The targets would give a signal to the public and private sectors to invest in improving productivity on existing land rather than expanding production into forest. BAPPENAS has developed sophisticated modelling capacity that will help in understanding the relevant links and analysing the consequences of various development choices for natural capital.

Land allocation, permitting and enforcement are improving

Progress has been made with respect to addressing historical challenges in the enabling environment for land management. This includes efforts to clarify the legal status of land, strengthen permitting arrangements and improve monitoring and enforcement.

Streamlining the issuance of land‑use permits

Permits are the main regulatory tool used to control land use and land‑use change. However, responsibility for issuing permits is spread among national ministries and government levels. As a result, transaction costs for applicants are high and there is confusion about which permits are required for which activities. There are widespread challenges concerning improper issuance of permits, as well as activities taking place without the required permits. The government is streamlining the process of issuing permits and enhancing efforts to verify that existing permits were issued correctly. In 2015, the president called for a simplified permitting process, and an online submission system was introduced in 2018. The switch to online databases can facilitate cross-checking to help identify potential irregularities. The MoEF is reviewing and evaluating permits in the forestry sector in accordance with the Presidential Instruction on Moratorium in Primary Forest and Peatland, Government Regulation No. 57/2016 on peatland management and the Presidential Instruction on Moratorium for new oil palm plantation permits.

One feature of the permitting process complicates protection of areas with high ecological value. Holders of permits for agricultural use are required to clear the area covered by the permit. Those wish to leave some forest land remaining risk having their concession permit revoked and transferred to another party (Daemeter Consulting, 2015). Expanding the legal mechanisms for protecting land of high conservation value would help address this challenge.

Clarifying the legal status of land

Land is managed according to a legal classification that is supposed to be based on the land’s function. In practice, this legal status was often ambiguous due to the existence of conflicting maps. Land’s legal status could also differ from its physical condition or ecological value, hampering efforts to direct production towards areas of lower ecological value. For example, land that is legally classified as forest (known as state forest) may lack trees, while forested land exists outside state forest areas.

Indonesia has made significant progress in addressing inconsistencies in spatial planning through the One Map initiative. The initiative aims to create a unified map, with 85 thematic layers specifying the status of land throughout Indonesia, at a scale of 1:50 000. It is also expected to present development objectives in consistent spatial maps. The process of creating the map has revealed overlapping claims and thus raises the need to correct and harmonise geospatial information in relation to the situation on the ground. To facilitate transparency, in line with the objectives of One Data, the new government data policy, the government is providing increased access to mapping data online. Maximising public access to mapping information will support transparency, facilitate research into deforestation drivers and aid in detection of illegal activities.

Developers of spatial plans are required by law to consider land’s ecological capacity in terms of water, ecosystems and agriculture. However, there is a need for further guidance and targets to help national, provincial and district governments put the law into practice. Efforts to better understand the value of natural capital would help in this process. The Global Green Growth Institute has trained local officials to better understand the role of natural capital. In addition to such capacity development, it would be helpful to have greater use of SEA at the local level and further research into the ecological and economic value of different types of land.

The One Map initiative makes it possible to create a unified land registry, which in turn will complement efforts to reallocate land to landless communities (notably through agrarian reform and social forestry, described later in this section). There is also a potential to better align the legal and physical characteristics of land by streamlining the land swap process, in which degraded state forest land can be exchanged for standing forest elsewhere. Administrative complexity has hindered the use of land swaps (Rosenbarger et al., 2013), limiting the ability to direct production to degraded land rather than high conservation value areas (Daemeter Consulting, 2015).

Peatland mapping remains a challenge

In addition to delineation of administrative boundaries, accurate physical mapping of peatlands remains a significant technical challenge. Land with deep peat is particularly important in ecosystem service provision. For example, carbon stocks below ground can be an order of magnitude higher than those above ground. Areas of deep peat are a useful proxy for the areas with the greatest carbon sequestration (Law et al., 2015). Regulations, guidance and methodologies exist for mapping peat, but there is a need for a detailed and comprehensive peatland map to guide policy decisions. Indonesia’s mapping agency has used a USD 1 million prize fund to encourage domestic and international researchers to find cost-effective, reliable approaches to enhance peatland mapping. The award will go to the group that develops the best methodology.

Strengthening compliance monitoring and enforcement is a government priority

Weaknesses in monitoring and enforcement of compliance with land‑use regulations have led to substantial losses of state revenue, encroachment into state lands and non-compliance with environmental regulations (KPK, 2015). Barriers to enforcement include lack of resources on the part of enforcement agencies and difficulty in securing convictions due to corruption and ambiguity over the legal status of land.

As a result of insufficient enforcement, designation of land as protected has been of limited effectiveness in preventing deforestation (Gaveau et al., 2012). Indeed, land under strict protection suffered increased deforestation rates over 2000‑10 (Brun et al., 2015). This can be attributed to insufficient funding, capacity gaps and increasing economic and development pressure (Waldron et al., 2017). Providing local communities with a stake in the sustainable use of these areas will be essential for increasing the effectiveness of protection measures.

Indonesia is taking steps to strengthen enforcement of laws related to environment and forestry. The institutional capacity of the MoEF’s Directorate General of Law Enforcement (DGLE) is being increased. In addition to its 16 existing provincial law enforcement offices, the DGLE recently established 19 new offices, so it is now present in all provinces. It then hired additional forestry police, civil investigators and inspectors. Use of technology, such as satellite monitoring, is being increased to facilitate detection of illegal activities.

The government has strengthened co‑ordination among ministries to improve enforcement. In 2015, the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK), along with MoEF and other ministries with natural resource portfolios, established the National Movement to Save Natural Resources. It serves as a platform for reviews and supervision regarding natural resource management in particular provinces (e.g. Papua). It is also used by the DGLE to co‑ordinate law enforcement activities. In addition, the MoEF and KPK conduct regular monitoring. The ministry has set up a law enforcement intelligence centre for co‑operation in the use of data and information from other bodies, such as the Ministry of Law’s Directorate of General Law Administration.