This chapter provides recommendations on how Costa Rica could improve the governance of integrity policy making and implementation. There is a need to articulate and co-ordinate key integrity actors to promote co-operation and the mainstreaming of integrity policies into the whole of government, including the decentralised public administrations. While the recent National Strategy for Integrity and Prevention of Corruption is a milestone towards a comprehensive integrity system, the country needs a permanent integrity policy co-ordination mechanism. In addition, Costa Rica could further build on some successful experiences and strengthen the implementation of the ethics management model.

OECD Integrity Review of Costa Rica

1. Ensuring a co-ordinated and coherent public integrity system in Costa Rica

Abstract

Introduction

Costa Rica is amongst the oldest and most stable democracies in Latin America. The adoption of a new constitution in 1949, after a civil conflict in 1948, renewed the bases for the country’s political and economic development. It made the state a key player, entrusting it with the fulfilment of key social, economic, and (later) environmental rights, while maintaining important areas of the economy, like banking, electricity and telecommunications, as state monopolies. It also entrusted the state with the administration of health, education and housing, and spawned a network of autonomous institutions (BIT, 2020[1]). Compared to the region, there are more and stronger political, legal and administrative checks on the executive branch, developed during the latter decades of the 20th century. Costa Rica also saw a major expansion of the recognition of the rights of the population and a strengthening of mechanisms to safeguard and protect them (Vargas-Cullell et al., 2004[2]).

The country is displaying good results in the area of public governance, integrity and corruption compared with other countries in the region and with the OECD average. In 2021, Costa Rica scored 8.12 out of 10 in the Index of Public Integrity by the European Research Centre for Anti-Corruption and State-Building (ERCAS). This score is higher than the average for both Latin American countries and OECD countries (ERCAS, 2021[3]). The 2021 Corruption Perception Index (CPI) shows Costa Rica performing well (58/100) in comparison with Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) averages (43/100) and only slightly below OECD average (67/100) (Transparency International, 2021[4]). Petty corruption is significantly lower in Costa Rica than in other LAC countries, with only 7% of the citizens reporting to have paid a bribe to access public services in Costa Rica, versus an average of 21 % for Latin America and the Caribbean (Transparency International, 2019[5]). In the recent 2022 Capacity to Combat Corruption Index, Costa Rica surpassed Chile for the first time to rank second behind Uruguay (Americas Society, Council of the Americas and Control Risks, 2022[6]).

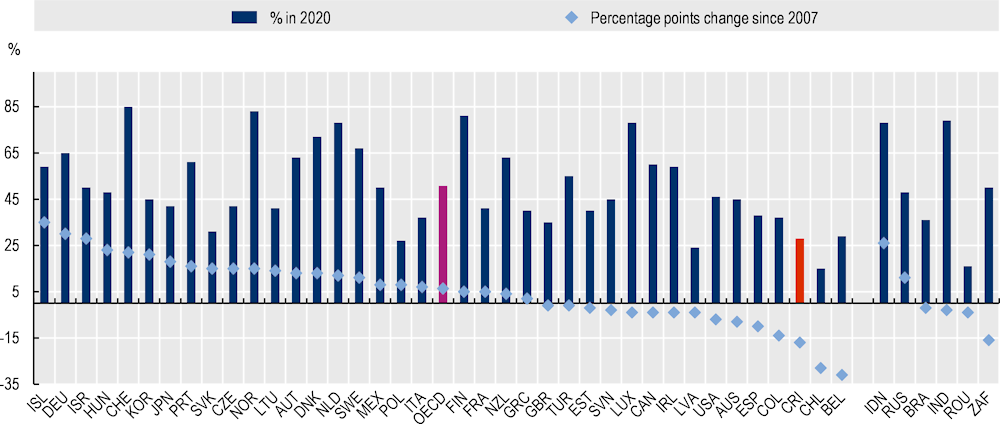

However, the country faces a growing need to consolidate the democratic gains, safeguard trust in government and build economic resilience. Similar to other countries, Costa Rica today is under pressure to deliver improvements in the quality of people’s lives, while global recession and economic inequality are rising. Many new challenges threaten economic and democratic stability. Amongst those challenges are the mitigation of the economic effects of COVID-19, the need to strengthen fiscal sustainability, to maintain low-carbon development and to strengthen macroeconomic stability (CABEI, 2020[7]). In fact, as shown in Figure 1.1, Costa Rica showed an important drop in confidence in national government. Between 2007 and 2020, trust dropped by 17 percentage points (OECD, 2021[8]).

Figure 1.1. Confidence in national government in 2020 and its change since 2007

Furthermore, a recent survey found that the COVID-19 pandemic has amplified integrity challenges for businesses in emerging markets, including Costa Rica. The survey showed that 63% of global respondents in emerging markets say it is difficult for organisations to maintain standards of integrity during difficult market conditions (EY, 2021[9]). Furthermore, Costa Rica has traditionally been perceived as a bastion of security in Central America. In recent years, however, the country has experienced record levels of violence, which authorities have blamed on its growing role as a drug transhipment point. Local crime groups are becoming more sophisticated and now pose a security threat for authorities as they become increasingly involved with transnational criminal organisations expanding their operations in Costa Rica, which typically cause corruption and instability (CrimeInsigth, 2019[10]). In 2018 and 2019, protests against a tax reform and an anti-union law shook the country, and in 2020, the government’s plans to strike a loan deal with the International Monetary Fund sparked renewed unrest (Freedom House, 2021[11]). Political reconfigurations have also affected stability; the historical dominance of the National Liberation Party (Partido de Liberacion Nacional, PLN) and the Social Christian Unity Party (Partido de Unidad Social Cristiano, PUSC) has waned in recent years, as newly formed parties have gained traction, leading to the collapse of the traditional two-party system. In 2018, seven parties won seats in the legislative elections. This has fragmented the electoral playing field and increased electoral volatility (Molina, 2021[12]; Freedom House, 2021[11]).

Finally, no country is immune to violations of integrity and corruption remains one of the most challenging issues facing governments today. In Costa Rica, recent investigations into alleged bribe payments by construction companies to officials of the National Roads Council (Consejo Nacional de Vialidad) with the intention of being awarded public works projects have evidenced existing vulnerabilities. They showed that the problem goes beyond the public sector and involves high-level executives in the private sector (case known as the “Cochinilla Case”) (LaPrensa, 2021[13]). Foreign bribery allegations have also had an impact on integrity issues in the country, as a major Costa Rican construction company signed a collaboration agreement with the Anti-Corruption Prosecutor's Office of Panama, to avoid a trial in a case of payment of gifts to officials of that country (OECD, 2020[14]). Furthermore, as evidenced in recent cases, integrity risks are becoming increasingly complex and include a wide range of practices in grey areas aimed at influencing public decision-making processes directly or indirectly, for example through lobbying activities or political finance (OECD, 2017[15]; OECD, 2021[16]).

Costa Rica is taking actions to avoid impunity. However, beyond the detection and sanctioning of specific cases, it is crucial that Costa Rica continues investing in prevention and strengthens its institutions to mitigate integrity risks. Indeed, to maintain the democratic and economic stability achieved over the last decades, establishing and continuously improving a coherent and comprehensive integrity system is a key ingredient. A system of sound public governance reinforces fundamental values, including the commitment to a pluralistic democracy based on the rule of law and the respect for human rights, and is one of the main drivers for trust in government (OECD, 2017[17]; Murtin et al., 2018[18]). The OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity provides policy makers with a vision for such a public integrity system based on international experiences and good practices (Figure 1.2). It shifts the focus from ad hoc integrity policies to a context dependent, behavioural, risk-based approach with an emphasis on cultivating a culture of integrity across the whole of society (OECD, 2017[19]).

Figure 1.2. The OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity: System, Culture, Accountability

The National Strategy for Integrity and Prevention of Corruption (Estrategia Nacional de Integridad y Prevención de la Corrupción, ENIPC) is an important step towards a resilient and strong integrity system in Costa Rica (ENIPC, 2021[20]). The ENIPC acknowledges the need of developing the governance of integrity as well as a national anti-corruption policy. Concretely, the ENIPC aspires to build a “coherent and comprehensive system of integrity and corruption prevention in Costa Rica that allows the articulation of the efforts of the public and private sectors and citizens” (ENIPC, 2021[20]). In this national dialogue initiated by the ENIPC, which is reviewed in more detail in Chapter 2, Costa Rica could consider and incorporate, to the extent possible, the recommendations provided in this OECD Integrity Review.

Governance of the public integrity system in Costa Rica

The goal of a public integrity system is to ensure the consistent alignment of, and adherence to, shared ethical values, principles and norms for upholding and prioritising the public interest over private interests in the public sector (OECD, 2017[19]). Country practices and experiences show that an effective public integrity system requires demonstrating commitment at the highest political and management levels of the public sector. In particular, this translates into developing the necessary legal and institutional frameworks and clarifying institutional responsibilities.

The legal framework for public integrity in Costa Rica

Over the past decade, Costa Rica has adopted measures aimed at consolidating its legal framework to enhance integrity (Box 1.1). The 1949 Political Constitution states the fundamental principle of public service. Jurisprudence of the Constitutional Chamber has derived from Article 11 the principles of responsibility, accountability, probity and impartiality and calls all public servants to act “with prudence, austerity, integrity, honesty, earnestness, morality and righteousness in the performance of their functions and the use of public resources entrusted to them” (OECD, 2017[21]).

Box 1.1. Main legal instruments in Costa Rica for Integrity and the fight against corruption

Complementing the Constitution, the two main anti-corruption and integrity regulations are the Criminal Code (Codigo Penal) of 1970 and Law 8422 of 2004, “Against Corruption and Illicit Enrichment in the Public Function” (Ley contra la Corrupción y el Enriquecimiento Ilícito, LCIE).

In addition, other provisions have strengthened the legal and institutional framework for integrity:

Law 8221 creates the Deputy Prosecutor for Probity, Transparency and Anti-Corruption (Fiscalía Adjunta de Probidad, Transparencia y Anticorrupción, FAPTA) at the Public Prosecution Office (Fiscalía General de la República, PPO) and the Anti-Corruption Unit of the Judicial Investigation Body (Organismo de Investigación Judicial, OIJ).

Law 8275 creates the Criminal Jurisdiction of Finance and Public Service.

Law 8292 General Law on Internal Control (Ley General de Control Interno, LGCI).

Decree 32333 of 2005 regulates the law against Corruption and Illicit Enrichment in Public Service (Ley contra la Corrupción y el Enriquecimiento Ilícito, LCIE).

Decree 33146 of 2006 regulates the “Ethical Principles of Civil Servants” (Principios Éticos de los Funcionarios Públicos).

Guideline D-2 of 2004, General Guidelines on Ethical Principles and Statements on Ethics to be followed by commanding officers, subordinate incumbents, officials of the Office of the Comptroller General of the Republic.

Source: OECD, based on OECD Questionnaire and desk research.

Official integrity actors and their responsibilities at the national level in Costa Rica

The promotion of public integrity typically involves many different official actors in the public sector that cover the various functions of an integrity system as defined in the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity (Table 1.1). While civil society and private sector of course also play a role, these official integrity actors include the “core” integrity actors, such as the institutions, units or individuals responsible for implementing, promoting and enforcing integrity policies, but also “complementary” integrity actors with key support functions such as finance, external audit, human resource management or public procurement (OECD, 2020[22]; OECD, 2017[19]).

Table 1.1. Main integrity functions in the public sector

|

SYSTEM |

CULTURE |

ACCOUNTABILITY |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Source: (OECD, 2020[22]).

The assignment of responsibilities for these integrity functions depends on the institutional and jurisdictional setup of a country. For example, some countries give core responsibilities for integrity to a central government body or a key ministry, whereas others will make this the responsibility of an independent or autonomous body. Typically, complementary integrity functions are assigned to the institutions responsible for education or human resource management, as well as supreme audit institutions, regulatory agencies and electoral bodies, for example. The OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity states the need of establishing clear responsibilities at the relevant levels (organisational, subnational or national) for designing, leading and implementing the elements of the integrity system for the public sector.

In Costa Rica, the main actors of the current integrity system are:

The Attorney General’s Office (Procuraduría General de la República, PGR) is part of the Ministry of Justice and Peace. It is the highest advisory, technical-legal body of Costa Rica’s public administration and the legal representative of the State in matters falling within its competence. Within the PGR, the Attorney for Public Ethics (Procuraduria de la Ética Pública, PEP) is the main responsible body for anti-corruption prevention and prosecution. Even though the PGR is attached to the Ministry of Justice and Peace, the law recognises the PGR’s functional independence in the exercise of its powers. In turn, the PGR indirectly has access to the executive and political leverage through the Ministry of Justice. At the time of this report, the PEP was composed of 31 officials, who are appointed based on proven ability and enjoy employment stability. Removal can only take place on grounds of justified dismissal or in the case of a forced reduction of services, as provided in Article 192 of the Political Constitution (OECD, 2017[21]).

The National Commission for Ethics and Values (Comisión Nacional de Ética y Valores, CNEV). The CNEV was established in 1987 by Executive Decree 17908-J and reformed by Executive Decree 23944 of 1994 to direct and co-ordinate the National System of Ethics and Values. The CNEV co-ordinates the Institutional Commissions on Ethics and Values (Comisiones Institucionales de Etica y Valores, CIEV). Overall, the CNEV is responsible for promoting, developing and strengthening ethics and values in the public sector, in private organisations and the Costa Rican society as a whole. Specifically, one of the core values promoted by the CNEV - next to respect, solidarity and excellence - is integrity, defined as acting consistently with the principles of truth and honesty in daily work and with transparency, justice and honourableness as guides to what’s just, correct and adequate. In turn, the CIEV are the implementing bodies of the CNEV that should exist in each ministry or agency of the executive branch, but that are only optional in the rest of the public administration (Executive Decree 23944-JC).

The Office of the Comptroller General of the Republic (Contraloría General de la República, CGR) is Costa Rica’s Supreme Audit Institution (SAI). It has full functional and administrative independence in the performance of its duties and reports to the legislative. Article 184 of the Political Constitution grants the CGR the power to supervise the execution and liquidation of the regular and extraordinary budgets and to examine and approve or not approve the budgets of the municipal governments and the autonomous institutions and supervise their execution and liquidation. In addition, the CGR provides guidelines regarding internal control and monitors and evaluates the internal control system. Furthermore, the CGR maintains a registry that keeps record of disciplinary sanctions to public servants and penalties applicable for non-justifiable increases in wealth (Chapter 3 and 5). The CGR has developed electronic tools to promote transparency and accountability and to measure the performance of the public administration (Chapter 2). Finally, the CGR is responsible for the assets declarations and for sanctioning public officials in case of inconsistencies or unjustified increases.

The Office of the Ombudsman of Costa Rica (Defensoría de los Habitantes de la República de Costa Rica) is responsible for protecting the rights and interests of the country’s population and reports to the legislative. Its mandate is to ensure that government authorities act within the boundaries of morality, justice, the constitution, legislation, conventions and general principles of the law. The Ombudsman participates in a wide range of anti-corruption activities including the Inter-institutional Transparency Network, delivers trainings, courses and workshops on corruption prevention and informs the public on how to file a complaint for corruption cases, for example.

The Deputy Prosecutor for Probity, Transparency and Anti-Corruption (Fiscalía Adjunta de Probidad, Transparencia y Anticorrupción, FAPTA) is responsible for criminal investigations and prosecutions. FAPTA has prosecutors in the capital San José and in regional offices. The Anti-corruption Unit of the Judicial Investigation Body (Organismo de Investigación Judicial, OIJ) supports FAPTA in conducting investigations. The OIJ is the judicial police established under the Supreme Court and conducts corruption investigations with the FAPTA. The OIJ may also receive and investigate complaints. Article 16 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (Código Procesal Penal, CCP) gives the PGR concurrent jurisdiction with FAPTA over corruption offences. The principal rationale for this arrangement is that the Costa Rican state is considered a victim in corruption cases. Therefore, the PGR participates in domestic corruption prosecutions to protect the state’s interest and seeks restitution from the offender (OECD, 2020[14]).

The Ministry of National Planning and Economic Policy (Ministerio de Planificación Nacional y Política Económica, MIDEPLAN) is in charge of formulating, co-ordinating, monitoring and evaluating the strategies and priorities of the Government. In addition, the recent Law on Public Employment (LMEP), which will enter into force on 10 March 2023, assigns the stewardship of the General Public Employment System to the MIDEPLAN, including providing guidance on ethics and conflict of interest, alongside the PEP (Chapter 3 and 5). Previously, this role has been assumed by the General Directorate of Civil Service (Dirección General del Servicio Civil, DGSC), although limited to the 47 entities of the Civil Service Regime (Régimen del Servicio Civil, CSR), covering approximately one-third of all public employees. Outside the CSR, most public institutions have their own legislation regulating public employment and HRM practices (OECD, 2017[21]). In fact, under the LMEP, the DGSC will continue to play a technical role.

The Ministry of the Presidency (Ministerio de la Presidencia) is in charge of ensuring that the priorities and policies of the President are mainstreamed in the executive. To this end, it co-ordinates the cabinet of ministers (Consejo de Gobierno) and plays a key role in promoting and following-up on public policies. The Ministry is also in charge of drafting legislation and leads the strategic relations with Congress towards legal reforms. Finally, it co-ordinates the transition period after changes in government. As such, the Ministry plays a key role in both promoting legal change and the implementation of integrity and anti-corruption policies. Note that the Ministry of Communication of the Presidency is leading Costa Rica’s open government policies.

The Costa Rican Institute on Drugs (Instituto Costarricense de Drogas, ICD) is attached to the Ministry of the Presidency. The ICD has instrumental legal personality for the performance of its activities and the administration of its resources and assets. The ICD was stablished by Law 8204 of 2001 and deals with issues related to drug trafficking (Law 7786 of 1998 and 8754 of 2009). Its work is related to the prevention and detection of money laundering. As such, the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) belongs to the ICD.

The Supreme Electoral Tribunal (Tribunal Supremo de Elecciones, TSE) was established by the Political Constitution of 1949. In practical terms, the TSE acquired the status of the fourth Power of the State, equalling the Legislative, Executive and Judicial Powers. The TSE performs four functions: Electoral administration; Civil registration; jurisdictional; and education on democracy. It plays a key function in safeguarding electoral integrity and democracy in Costa Rica.

This Integrity Review looks into responsibilities for the development of strategies and monitoring (Chapter 2), for managing conflict of interest (Chapter 3), transparency and integrity in public decision-making (Chapter 4) and in the disciplinary regime (Chapter 5). The remainder of this chapter analyses and provides recommendations on aspects of co-ordinating integrity policies to promote co-operation and mainstreaming integrity policies into the whole of government.

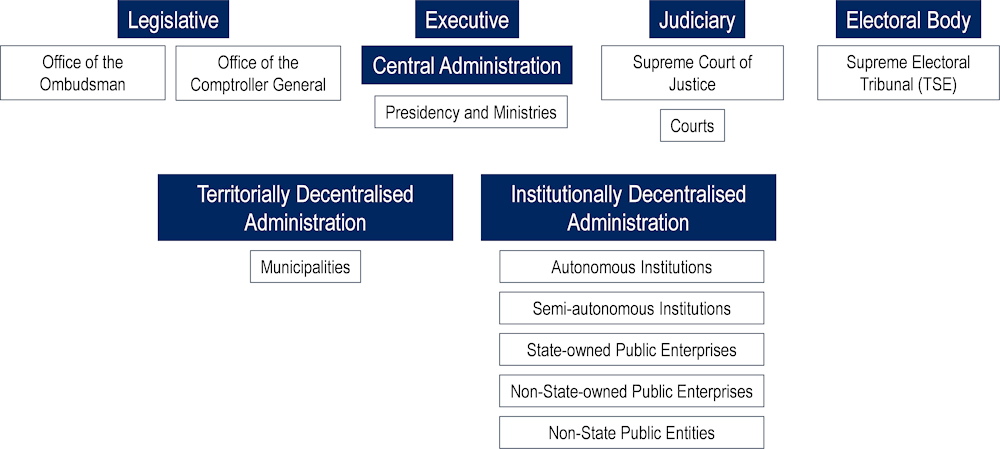

The topics reviewed are threefold. First, while a working group was established under the shared leadership of the PEP and Costa Rica Íntegra, the national chapter of Transparency International, to promote co-operation between the different integrity actors at the planning stage of the ENIPC, a more permanent and multipurpose co-ordination is needed in Costa Rica. Second, Costa Rica faces challenges in ensuring a coherent steering and implementation of integrity policies in the institutional decentralised public administration (Administración Decentralizada Institucional) and the territorial decentralised public administration (Administración Decentralizada Territorial). Figure 1.3 provides a simplified overview of the organisation of the Costa Rican public sector. Third, Costa Rica could further build on some successful experiences in mainstreaming integrity policies into public organisations, in particular by strengthening the CNEV and CIEV, by modernising its ethics management model (Modelo de Gestión Ética, MGE) and by leveraging the ethics audits promoted by the CGR.

Figure 1.3. The organisation of the Costa Rican public sector

Source: Simplified representation prepared by the OECD based on information provided by the MIDEPLAN.

Formalising inter-institutional co-ordination on public integrity policies

Leveraging on the co-ordination achieved during the construction of the ENIPC, Costa Rica could consider a permanent co-ordination commission that includes all relevant public integrity actors and a whole of society approach

The OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity invites countries to promote mechanisms for horizontal and vertical co-operation between the different relevant public integrity actors, including, where possible, with and between subnational levels of government. Such co-operation mechanisms can be formal or informal and aim at supporting coherence, avoiding overlap and gaps as well as sharing information and building on lessons learned from good practices (OECD, 2017[19]).

In fact, evidence suggests that reforms that aim to create or strengthen a values-based culture of sound public governance and integrity cannot be implemented through silo approaches. Crosscutting, multidimensional reform strategies forged through robust co-ordination across government silos to incorporate all relevant areas seem to work best (OECD, 2018[23]). A key advantage of gathering the relevant actors together is that integrity policies can take advantage of the various kinds of expertise around the table and ensure a broad implementation across the public sector by promoting ownership and commitment (OECD, 2019[24]).

Therefore, for an effective co-ordination across the public integrity system, all relevant actors and stakeholders should be articulated through a co-ordination mechanism. Such co-ordinating mechanisms are usually established to lead the anti-corruption reform efforts in a country, in particular the development, implementation and monitoring of a national anti-corruption strategy and policy. The anti-corruption mechanisms, councils, commissions or committees, typically consist of responsible government agencies and ministries. Beyond the executive, they sometimes involve representatives of the legislative and the judiciary and may involve civil society. They are usually assisted by a technical unit supporting the work of the co-ordination mechanism. Table 1.2 provides an overview of some co-ordination arrangements in selected Latin American countries.

Table 1.2. Selected public integrity systems in Latin America

|

Country |

Co-ordination Unit |

Co-ordination mechanism |

Includes legislative |

Includes judiciary |

Includes other actors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Argentina |

Secretary of Institutional Strengthening (Secretaría de Fortalecimiento Institucional) in the Executive Office of the Cabinet of Ministers |

Informal co-ordination through working groups System is in the process of being reformed |

No |

No |

No |

|

Brazil |

Office of the Comptroller General of the Union (Controladoria-Geral da União, CGU) |

Anti-corruption Inter-ministerial Committee (Comitê Interministerial de Combate à Corrupção, CICC) |

No |

Yes |

No |

|

Colombia |

Transparency Secretariat (Secretaría de Transparencia, ST) |

National Moralisation Commission (Comisión Nacional de Moralización, CNM) |

Yes |

Yes |

National Citizens' Committee for the Fight against Corruption (Comité Nacional Ciudadano para la Lucha contra la Corrupción) |

|

Chile |

Ministry of the General Secretariat of the Presidency (Ministerio Secretaria General de la Presidencia) |

Commission for Public Integrity and Transparency (Comisión para la Integridad Pública y Transparencia) |

No |

No |

An anti-corruption alliance was established as a working group with the private sector and civil society, but they do not participate in the co-ordination structure. |

|

Costa Rica |

n.a. |

Informal co-ordination, agreements between institutions |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

Ecuador |

Anti-corruption Secretariat (Secretaria Anticorrupción) |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

|

Mexico |

Executive Secretary of the National Anti-corruption System (Secretaria Ejecutiva del Sistema Nacional Anticorrupción, SESNA) |

Comité Coordinador del Sistema Nacional Anticorrupción |

No |

Yes |

Citizen Participation Committee (Comité de Participación Ciudadana) |

|

Peru |

Secretariat of Public Integrity (Secretaría de Integridad Pública, SIP) |

High-level Commission against Corruption (Comisión de Alto Nivel Anticorrupción, CAN) |

Yes |

Yes |

Includes private sector, unions, universities, media and religious institutions (with voice, without vote) |

Source: Based on (OECD, 2019[24]), updated with (OECD, 2021[25]), (OECD, 2021[26]), (OECD, 2021[27]) and Executive Decree 412 of 2022 (Ecuador).

Costa Rica currently does not have such a formal co-ordination mechanism involving all key integrity actors. There have been, however, a number of informal co-ordination initiatives. These arrangements have benefitted from a political culture based on trust rather than formal requirements. For example, there have been ad hoc collaborations between the CNEV and PEP consisting of legal reviews by the PEP of guides and manuals issued by the CNEV. Furthermore, some trainings have been conducted jointly for the institutions of the National System of Ethics and Values. Another example is an informal working group on enforcement established by the PEP, CGR, FATPA and the ICD. While an agreement has been signed by the leaders of the institutions, the decision made was to not further formalise the mechanism to maintain its flexibility. Consequently, no official agenda exists, but according to the interviews conducted, this working group has led to various joint efforts and has improved co-ordination, albeit on an ad hoc basis (OECD, 2017[21]).

In adopting the ENIPC, Costa Rica aimed at addressing existing silos and laid the foundation for increased co-operation through its participative approach. At the same time, while evidencing the potential benefit of such closer co-operation, the process of the ENIPC also has exposed challenges with respect to achieving an effective and more consistent co-ordination between actors of the public integrity system. For instance, the interviews conducted by the OECD showed that the degree of involvement of some relevant integrity actors during the ENIPC has been uneven. Relevant stakeholders such as local administrations or the Presidency and the Congress, who are vital to passing implementing legislation, were not very well informed about the process and had little knowledge about the ENIPC and their role. Similarly, some stakeholders mentioned during the virtual fact finding mission that at times it is difficult to understand who does what, which creates risks for duplications and overlaps. Furthermore, it was reported that constant changes of public officials in public entities are eroding the continuity of engagement and co-ordination efforts. Chapter 2 provides a more in-depth analysis and recommendations on how to build on the ENIPC and improve the strategic process.

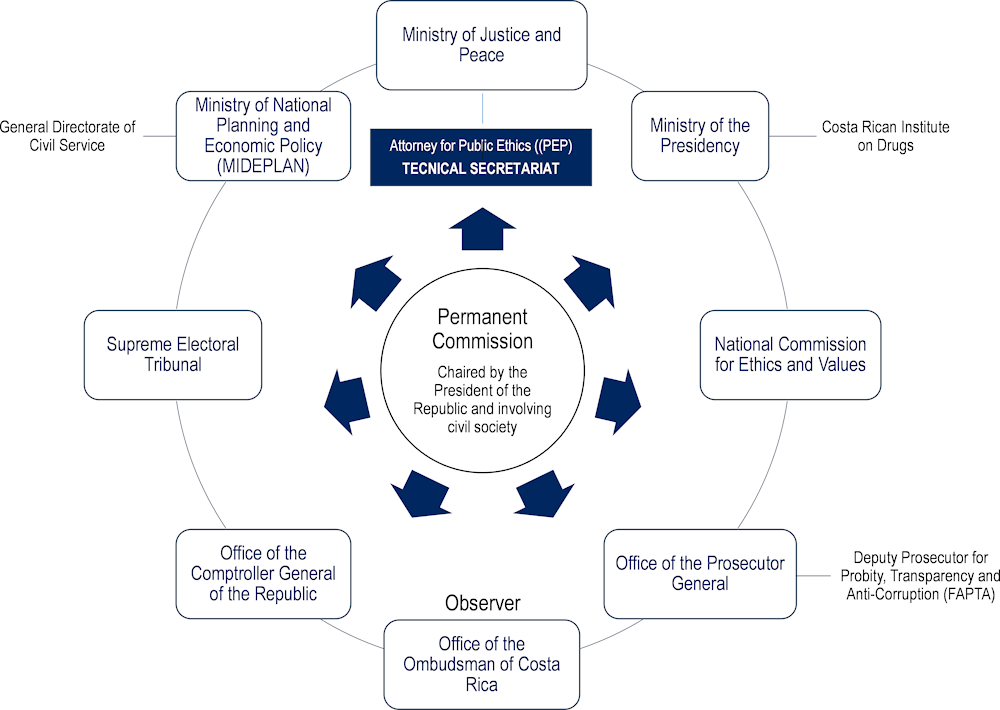

Therefore, to improve co-operation while recognising that several actors play a role in implementing different aspects of integrity policies, Costa Rica could consider establishing a formal permanent commission, ideally established by Law, as a co-ordination mechanism. During the virtual fact-finding, several actors expressed the need to move from the rather informal settings to a more formal co-ordination, building on the experience acquired during the preparation of the ENIPC. Enshrining the co-ordination mechanism in a Law would allow to build it on a stable foundation, more resilient to future changes in governments and policies. For example, the Colombian National Moralisation Commission has been established by Law 1474 of 2011 and the Peruvian High-Level Commission against Corruption (CAN) by Law 29976 of 2013 (OECD, 2017[28]; OECD, 2017[29]). Costa Rica could learn from the experiences of these countries and consider an arrangement that reflects its institutional landscape and context. Based on the analysis conducted by the OECD, Figure 1.4 provides a proposal for such a mechanism.

Figure 1.4. Proposal for a formal public integrity co-ordination mechanism in Costa Rica

Source: OECD.

As a clear signal of political commitment and to set the tone-at-the-top, the commission could be presided and led by the President of the Republic, as head of the State. The members of the commission should be represented by the heads of the institutions so that relevant decisions can be taken directly by the group. In the case of the Prosecutor General, this participation could be delegated to the specialised unit of the FAPTA. During the interviews conducted by the OECD, the Ombudsman Office voiced concerns with respect to its participation in such a mechanism. During the interviews, the Ombudsman emphasised the importance of maintaining and clearly signalling their independence. Even so, the Ombudsman Office brings relevant information and perspectives to the table and could significantly enrich the debates. Similar to the Ombudsman Office of Peru, the participation could therefore be restricted to voice but without the power to vote and its involvement be communicated as an observer. The proposal for the Technical Secretariat will be discussed in the section below.

In addition, Costa Rica should involve the civil society and the private sector in a more formal way to promote a whole-of-society perspective in the discussions.

Civil society: If civil society and academia feel comfortable with being involved and able to maintain and communicate their independence, such an involvement could be achieved by giving civil society, including academia, a permanent seat in the Commission. As with the Ombudsman, and for the same reasons, this representation could be with voice but without vote, to promote independent opinion. The organisation or person could be elected for a given period of time (e.g. two years). There are already similar practices in Costa Rica on which to build on. The National Open State Commission (Comisión Nacional de Estado Abierto) has two civil society representatives who are chosen by the Commission based on an application process open to any organisation that works on related issues. Similarly, the Institutional Commission of Open Parliament (Comisión Institucional de Parlamento Abierto) has an open call for applications and the directorate of the Legislative Assembly elects the representatives of civil society. In both commissions Costa Rica Íntegra, the national chapter of Transparency International, has applied and been elected. Alternatively to a permanent representation, civil society could be included by legally requiring the commission to regularly consult civil society and academia through formal and transparent channels. This could avoid potential issues with independence and representativeness, while ensuring broad opportunities for several organisations and academics to participate.

Private sector: Some private sector organisations and business associations consulted by the OECD in the context of this Integrity Review expressed that they appreciated the efforts that were made to involve them in the elaboration of the ENIPC. Others, however, stressed that they were not invited but would have liked to contribute their views. At the same time, they advocated for a more flexible, non-bureaucratic involvement. Therefore, the co-ordination commission could consider ways of regularly inviting private sector to provide inputs and feedback into the discussions while ensuring that these channels are transparent and open (Chapter 4).

The proposal for this commission contributes to the national dialogue in Costa Rica on achieving the Activity 1.1.1 of the ENIPC, which aims at proposing a governance model to organise and develop the work on integrity, control environment and anti-corruption. Ideally, Costa Rica could consider establishing such a commission before starting the development of the national integrity and anti-corruption policy as foreseen in Activity 1.2.1 of the ENIPC. The process of developing this policy could be one of the first concrete tasks of the new commission and allow to test and, if necessary, adapt its working regulations and procedures. Later, the commission would be responsible in steering and overseeing the implementation of the ENIPC and the policy, regularly discussing emerging integrity challenges, designing integrity legislation and guidance, as well as ensuring the mainstreaming of integrity policies through the whole of government and society. In addition, the commission could ensure a coherent communications strategy capable of providing citizens, private sector and public officials alike with an overarching idea of existing and planned integrity policies.

As discussed in the subsequent sections, this high-level commission could be supported by two technical sub-commissions, one on prevention and one on enforcement, and supported by a technical secretariat as general co-ordination unit, which could be assured by a strengthened PEP, building on its recent experience of co-ordinating the ENIPC.

Two technical sub-commissions, one on prevention and one on enforcement, could promote discussions on more technical levels and ensure continuity of policies

In addition to the high-level commission recommended above, to increase the ownership of its members and to make the most out of the knowledge around the table, Costa Rica could strengthen the technical discussions around integrity and anti-corruption policies by establishing two technical sub-commissions, one on prevention and one on detection and sanction. The technical sub-commissions would meet more regularly than the high-level commission.

In particular for the area of enforcement, there have been some already mentioned informal efforts in Costa Rica to co-ordinate on particular cases and actions, which could constitute the basis for a technical sub-commission discussing aspects related to detection, investigation and sanctioning of cases. Indeed, the FAPTA, the CGR and the PEP already meet regularly to discuss cases, including at the subnational level and law enforcement co-ordination has been achieved on specific cases. These same institutions have also been working on a platform to collect data on complaints to identify the sectors that are most vulnerable and prone to corruption in Costa Rica.

A sub-commission on enforcement could discuss and propose reforms on more technical levels, which could then be approved at the level of the high-level commission and brought to the legislator, if required. According to Costa Rican authorities interviewed by the OECD, enforcement would benefit from a more formal structure for sharing relevant case information. This would in turn contribute to the fulfilment of criminal policy objectives, the developing a strategy to address the links between corruption and organised crime, encouraging the sharing of relevant case information, standardise criteria for reporting and accessing information by law enforcement agencies, amongst others. For example, the FAPTA would like to have direct access to asset declarations, now managed by the CGR, to use this as evidence in high profile cases of illicit enrichment (Art. 46 Illicit Enrichment Law). Similarly, FAPTA, who largely depends on internal data from other agencies (including the judiciary), finds it difficult to access and analyse information because of the quality of the data and a lack of homogenous system. The sub-commission could also explore the development of agreements between agencies to ensure consistency in the data reported and work towards establishing a strategy for the use of data analytics, or establishing a shared judicial police section for anti-corruption investigations. Such a shared judicial police service may include auditors specialised in economic and financial crimes as well as criminologists that can provide in-depth criminal analysis. The sub-commission could also leverage on the “virtual desk” led by FAPTA and ensure that this initiative is properly known by and co-ordinated with all relevant actors.

In turn, on the preventive side, the responsible sub-commission could in particular monitor the implementation of the ENIPC and steer the development of the forthcoming integrity policy. Later, the sub-commission would play a key role in monitoring the implementation of the policy, producing evidence using relevant indicators and informing the high-level commission about possibly required actions to adjust to new challenges, priorities or opportunities (Chapter 2). Furthermore, the sub-commission on prevention could identify and discuss generic corruption risks and the effectivity of mitigation measures to fine-tune integrity risk management methodologies and to provide better guidance on integrity risk management throughout the whole public administration, including in the institutionally and territorial decentralised administrations. The sub-commission could also discuss improvements of existing integrity policies such as the implementation of ethics codes, communication and awareness raising strategies, policies to improve transparency and integrity in political decision-making processes (Chapter 4), regulations and guidance on managing conflict of interest (Chapter 3) and could align with the General Public Employment System, created recently by the Law on Public Employment (Law 10159, Ley Marco de Empleo Publico, LMEP), led by the MIDEPLAN.

Together, both sub-commissions would help ensuring the technical foundations for the discussions and decisions in the high-level commission and contribute to the technical quality of integrity policies in Costa Rica. The technical sub-commission could also contribute to strengthen continuity beyond changes in government and of the heads of the respective members of the high-level commission (or “jerarcas”). Together, both sub-commission could also improve the identification of criminal macro trends and promote the use of data and statistics that, in turn, may lead to improve the evidence-base for the preventive work (Chapter 2). Depending on the agenda that is being discussed, the technical experts participating in these sub-commissions could vary from meeting to meeting and therefore contribute to mainstreaming knowledge and responsibilities within the participating integrity actors. These technical experts would be responsible for briefing their respective head of agency and to follow-up any decisions taken in the commission or sub-commission in their respective institutions. If required for the discussions, experts from civil society and academia, public officials from other relevant public actors not regularly participating in the high-level commission (e.g. the ministry of public education, the ministry of health or the ministry of public works and transport), or from the private sector could be invited to contribute from their perspective and specific knowledge.

Costa Rica could assign the responsibility for central institutional co-ordination of integrity policies to the Ministry of Justice and the Attorney for Public Ethics, or consider establishing a new, independent authority

Beyond ensuring political commitment at the highest level, experience with similar arrangements in other countries indicate that, to allow for a proper functioning of such a co-ordination mechanism, it is important that there is a technical support unit with the required mandate, summoning power, capacities and appropriate financial resources to convene the relevant actors, organise the meetings, the agendas, steer the discussions and prepare background information. For example, the Anti-Corruption Council in Georgia is supported by the Secretariat in the Ministry of Justice, the Inter-ministerial Working Group in Albania by a secretariat within the Cabinet of Ministers, the National Moralisation Commission of Colombia by the Transparency Secretariat located in the Vice-presidency office and the High-Level Commission against Corruption (CAN) of Peru by the Public Integrity Secretariat (Secretaria de Integridad Pública, SIP), attached to the Presidency of the Council of Ministers (see Table 1.2 above).

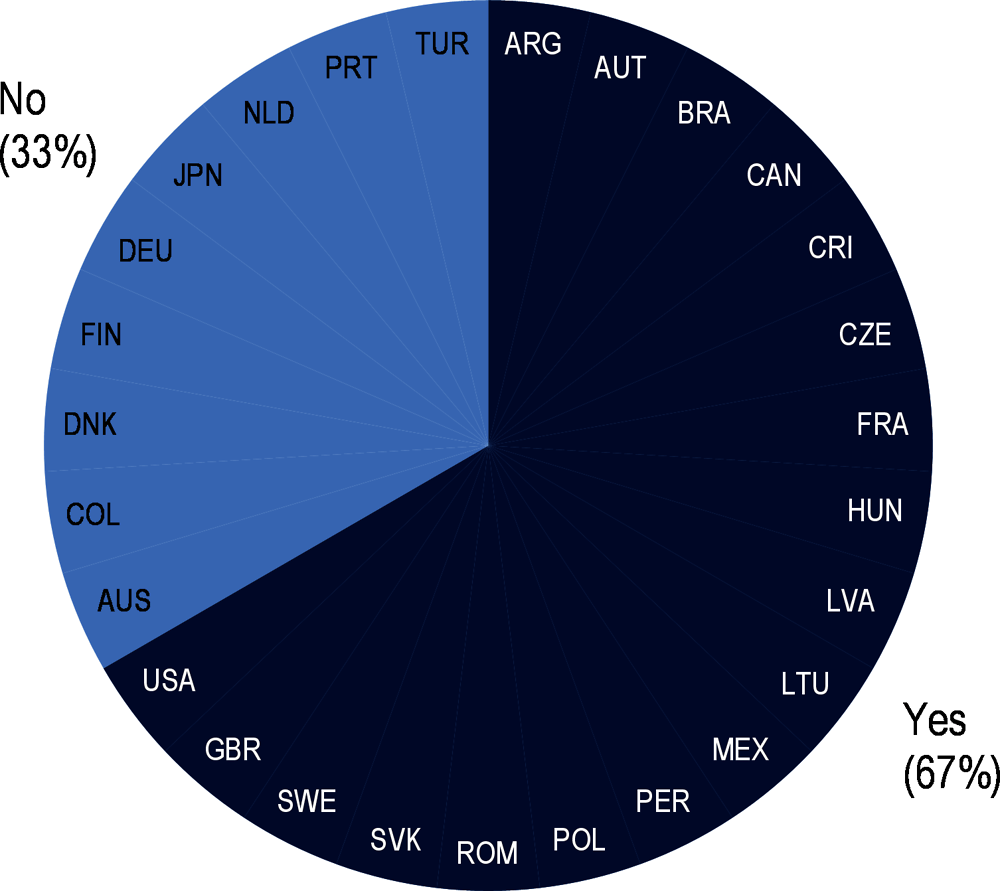

In Costa Rica, the Attorney for Public Ethics (PEP) is currently the competent national authority of Costa Rica under the United Nations Convention against Corruption, the contact point for the Mechanism for Follow-up on the Implementation of the Inter-American Convention against Corruption (MESISIC) and represents Costa Rica in the OECD Working Party of Senior Public Integrity Officials (SPIO). There, it has been active in exchanges of good practices and the dialogue on integrity amongst OECD countries and in Latin America. While the OECD Working Group on Bribery (WGB) in its phase 2 evaluation recommended that a single public body should be tasked with overseeing the implementation of the national strategy and action plan (OECD, 2020[14]), the PEP de facto already played this role in co-ordinating the development of the ENIPC, liaising with the entities from the public sector, the private sector and civil society. This role has been acknowledged in the OECD Public Integrity Indicators (Figure 1.5). Nonetheless, according to the interviews conducted for this review, formalising this role as the central co-ordinating role is a much-needed step to strengthen co-ordination, communication and for creating synergies between the existing integrity actors.

Figure 1.5. PII: Existence of a central co-ordination function responsible for co-ordinating the implementation, monitoring, reporting and evaluation of the action plan

Based on the process of the ENIPC and its mandate, the PEP is of course the natural candidate to carry out this role of the technical secretariat. Being located in the executive and under the political leadership of the Ministry of Justice and Peace, but with functional independence and independent judgment in the performance of its attributions, the PEP is also both close to the public administration and able to promote the trust required to enable a better co-ordination between the executive and law-enforcement agencies. In this task, the PEP could be further supported in particular by the MIDEPLAN to leverage its experience with planning and monitoring of public policies as well as its new role in the context of the LMEP, involving responsibilities related to the management of conflict of interest and the disciplinary enforcement.

However, to ensure the successful steering of integrity policies, Costa Rica could consider strengthening the PEP along several lines:

First, the legal mandate for steering and co-ordination of integrity and anti-corruption strategies and policies should be included explicitly amongst the PEP’s functions. The mandate would in particular include acting as the central co-ordination unit and technical secretariat responsible for supporting the high-level commission and for providing guidance to both sub-commissions, helping to shape the agendas, facilitate the work and ensuring the exchange of information between the participating members. The PEP, with political support from the Ministry of Justice, should be able to articulate closely and regularly with the Ministry of the Presidency, so that decisions related to the preparation of draft legislation and the relationship with the National Congress can be jointly planned and implemented and to ensure that integrity policies find their way into the agenda of the Cabinet of Ministers. Special attention should be giving to assuring co-ordination with the MIDEPLAN, CNEV and CIEV, in particular to mainstream public ethics and conflict-of-interest management in the whole of the public sector and the whole of society.

Second, the PEP should clearly separate into two distinct internal areas its work related to the reception and processing of administrative complaints for acts of corruption, lack of ethics and transparency in the exercise of public functions, on the one hand, from the preventive functions related to prevention and the steering, co-ordination and monitoring of integrity policies, on the other hand. Both areas should have a separate internal budget, a separate staff with specific required skills and should be able to develop a distinct communication strategy. Indeed, experience and research evidences the benefit of clearly separating enforcement from prevention roles, especially also because enforcement priorities often prevail over prevention, both in terms of time and resources (OECD, 2019[30]; OECD, 2018[31]). Especially in an institution like the Office of the Attorney General, that has a strong legal culture and focuses on cases, it is key to implement internal institutional arrangements that safeguard an area that is policy-oriented and focuses on prevention. The area requires different perspectives and different skills as currently present in the Office of the Attorney General and are only nascent in the PEP.

Finally, Costa Rica could also consider entrusting the preventive area of the PEP with a broader role and gradually incorporate a whole of government approach to integrity policies in Costa Rica. This may include centre of government steering of integrity policies, particularly, in the institutionally decentralised sector and providing clearer guidance for the territorially decentralised public sector, while respecting the autonomy and enable differentiated local integrity policies that respond to different priorities, needs and opportunities across the territory (OECD, 2021[32]).

This potential reform of the PEP would ideally go along with an internal organisational development exercise aimed at defining and sharpening the PEP’s new strategic focus, priorities, boundaries and internal co-ordination and communication channels. In addition, the PEP could increase its own transparency and accountability, for instance, by strengthening its own website and by preparing public reports and statistics on its activities and results.

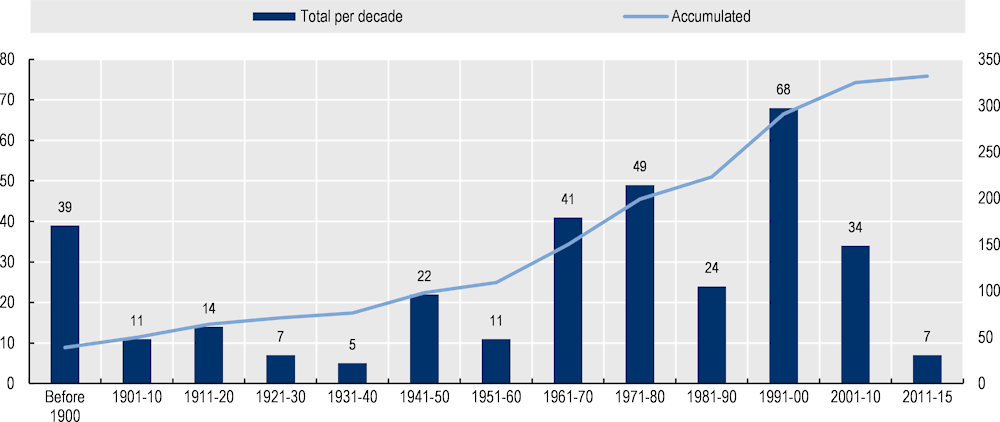

As an alternative option, Costa Rica could also consider the opportunity provided by the ENIPC to establish a new integrity agency in Costa Rica, with administrative and financial independence, as well as an own legal capacity and budget, in charge only of prevention, central co-ordination and monitoring of integrity policies. First, such an agency would enable an even clearer distinction between the roles of prevention and enforcement in Costa Rica. Second, a new independent agency could send a clear message to the public sector, to law enforcement agencies and to society as a whole that there is a commitment to avoid any politisation of the integrity and anti-corruption agenda. In turn, the PEP could then concentrate on its current role as attorney of the State, recovering assets from corruption cases and fighting for recognising the social costs of corruption, as well as on the reception and processing of administrative complaints related to corruption. However, it is unclear whether the potential benefits of this alternative option can justify the administrative and financial costs of creating a new institution. Taking into account the context in Costa Rica, where there has been criticism related to the creation of too many institutions (Academia de Centroamérica, 2016[33]), such an option should be considered very carefully by the legislator (Figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6. Number of created public institutions in Costa Rica, 1900-2015

Mainstreaming integrity policies into the whole public administration

Costa Rica faces a cross-cutting challenge of implementing integrity policies in the institutionally (ADI) and territorially (ADT) decentralised public administrations

Countries around the world are facing the challenge of ensuring a coherent and effective implementation of integrity policies throughout their public administration, sometimes referred to as the challenge of mainstreaming. Typically, gaps exist between the normative requirements of the framework and actual effective implementation. In line with the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity, implementation goes beyond a formal compliance with the existing regulations and should achieve real change in organisational cultures and behaviours (Rangone, 2021[34]; OECD, 2018[31]). In particular, the challenge involves translating and anchoring standards into a wide variety of organisational realities.

A coherent implementation of integrity standards may also be more difficult because of different levels of autonomy and independence between branches of government, between levels of government and between entities within the public administration. Indeed, as mentioned above and shown in Figure 1.3, Costa Rica’s public sector, beyond the division between branches, with the legislative, the judiciary and the Supreme Electoral Court, further divides the public administration into three levels:

The Central Administration (Administración Central) at the national level, with the ministries.

The Institutionally Decentralised Public Administration (Administración Descentralizada Institucional, ADI), with autonomous institutions, semi-autonomous institutions, state owned enterprises, non-state public enterprises, non-state public entities.

The Territorially Decentralised Public Administration (Administración Descentralizada Territorial, ADT), with the 84 municipalities.

Most entities of the institutionally decentralised sector were created in the 1940s as autonomous institutions with a mandate of policy making as well as service delivery, such as health, energy and education. A more recent wave of newly created public institutions primarily consists of subsidiary bodies, representing “policy implementation shortcuts” to attain greater administrative and budgetary flexibility (OECD, 2017[21]). Organisations that belong to the ADI are enjoying autonomy with respect to the internal management of public ethics. There is no requirement to implement a code of conduct or ethics and no specific guidance on how to develop such a code or to train and provide guidance to staff.

In turn, the territorially decentralised public sector in Costa Rica has a total of 84 Municipalities and 8 Municipal District Councils (MIDEPLAN, 2019[35]). Law 7794 of 2008, better known as the Municipal Code, governs the structure, operation, characteristics, organisation and scope of the country's municipal system. According to the Code, each “canton” (administrative territorial units) is composed of municipalities (administrative body) and councils (oversight) (MIDEPLAN, 2019[35]). According to Law 4325, municipalities have financial and administrative autonomy and full discretion over the implementation of national policies at the local level. This provision gives autonomy to municipalities to implement their own integrity and anti-corruption policies. The central government can only provide general guidelines to this level. The MIDEPLAN provides tools and guidance for planning at the local level and, if needed, establishes formal agreements. Additionally, the Municipal Development and Advisory Institute (Instituto de Fomento y Asesoría Municipal, IFAM) is an autonomous institution that provides regulatory support and trainings to municipalities.

Integrity is the responsibility of all public officials, independent of the branch or sector they are working in. Following the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity, and in line with Art. 2 of the United Nations Convention against Corruption definition of public officials, the public sector includes:

“…the legislative, executive, administrative, and judicial bodies, and their public officials whether appointed or elected, paid or unpaid, in a permanent or temporary position at the central and subnational levels of government. It can include public corporations, state-owned enterprises and public-private partnerships and their officials, as well as officials and entities that deliver public services (e.g. health, education and public transport), which can be contracted out or privately funded in some countries.” (OECD, 2017[19])

In particular, integrity leadership at all levels within a public organisation is essential to demonstrate commitment to integrity. With their function of being ethical leaders and providing an example, public managers play a crucial part in the effective promotion of an integrity culture (OECD, 2017[19]; OECD, 2009[36]; OECD, 2020[22]). For example, in Colombia, the Integrated Planning and Management Model (Modelo Integrado de Planeación y Gestión, MIPG) requires public managers to periodically report on their actions related to integrity, transparency and other cross-cutting issues (Función Pública, 2017[37]). In France, senior management are personally responsible and ultimately accountable for the effective implementation and promotion of an organisation’s integrity programme (Agence Française Anticorruption, 2020[38]). Not at least, planning is an important tool to trickle down policies from the national level to the organisational levels, including in the territory (Chapter 2).

Nonetheless, dedicated “integrity actors” in public entities can contribute to overcome the challenge of mainstreaming integrity policies to ensure implementation and to promote organisational cultures of integrity. International experience shows the value of having a specialised and dedicated person or unit that is responsible and can be held accountable for the internal implementation and promotion of integrity laws and policies (OECD, 2009[36]; G20, 2017[39]; OECD, 2019[24]). In Peru, for example, Offices of Institutional Integrity have to be established throughout the national public administration and in local governments, with the Secretariat for Public Integrity as governing body (OECD, 2019[40]; OECD, 2021[41]). In Brazil, the established Public Integrity System of the Federal Executive Branch (SIPEF) aims at mainstreaming integrity policies with the Office of the Comptroller General (CGU) as central organ and Integrity Management Units (UGI) in all entities of the federal executive branch (OECD, 2021[26]).

In Costa Rica, an important, yet beyond the Central Administration voluntary tool for mainstreaming, exists currently in the area of ethics management: the National Commission of Values (CNEV) and the Institutional Commissions on Ethics and Values (CIEV). This section covers the essential role played by both the CNEV and the CIEV as catalysts of the integrity system. The CIEV, in particular, could provide the foundation for more functional dedicated and professionalised integrity units. The next sections also emphasise the role played by the CGR, which can set incentives to implement integrity and ethics standards throughout the entire public administration, including the decentralised sectors, through its external audit function as well as through the guidelines on “ethical audits”.

Costa Rica could reach the Decentralised Public Administrations through dedicated integrity units, building on the Institutional Commissions on Ethics and Values (CIEV) and strengthening the National Commission of Values (CNEV)

In Costa Rica, as early as 1987, the National Ethics and Values Commission (CNEV) was created by Executive Decree 17908-J, to carry out the objectives of the National Plan for the Rescue of Values, with the participation of Ministries and other institutions of the central administration. To strengthen the actions of the CNEV, Executive Decree 23944-JC of 1994 established the Institutional Commissions on Ethics and Values (CIEV) as implementation units of the CNEV that should exist in each ministry or agency of the executive branch and that are optional in the rest of the public administration (ADI and ADT). Incentives for implementing a CIEV were indirectly provided through the CGR’s Institutional Management Index (Índice de Gestión Institucional, IGI), where having such a commission in place improved the score. The IGI was last implemented in 2019 and is being replaced by the Management Capacity Index (Índice de Capacidad de Gestión, ICG; see Chapter 2, Box 2.3).

The Executive Decree establishes that the objective of the CNEV and CIEV is to promote ethics and to contribute to the efficiency of the public sector. The CNEV is supporting the implementation of the ethics management model (Modelo de Gestión Ética, MGE). The MGE includes, amongst others, the establishment of a CIEV, periodic assessments of institutional ethics (diagnosis), steering the development of an organisational Ethics Code or an Ethics Manual, implementing communication campaigns and providing advice to the CIEV in designing training programmes on ethics, as well as support on how to include ethics into key institutional processes (Box 1.2). The guidance provided by the CNEV clearly separates public ethics from legal and disciplinary issues, which can be regarded as a good practice following behavioural insights on how to promote a culture of integrity based on shared common values (OECD, 2018[31]). This clear separation should be maintained.

Box 1.2. The Ethics Management Model in Costa Rica

Costa Rica promotes the ethics management model (Modelo de Gestión Ética, MGE) in public organisations based on self-regulation. An institution wishing to implement the MGE has to implement the following steps:

Positioning: It requires the formalisation of the commitment of the highest authority of the institution (“jerarca”) and the establishment of an Institutional Commission on Ethics and Values (Comisiones Institucionales de Etica y Valores, CIEV), which can be supported by a technical unit. The CIEV has to receive training, define its work plans and monitor its actions.

Diagnosis and definition of the Ethical Framework: The participatory identification of the values leading to the drafting of a Code of Ethics or Conduct, an Ethics Policy and its action plan.

Communication and training: Requires communicating the shared values, the manual or code and other elements of the institutional ethical framework and the creation of feedback and consultation mechanisms for civil servants. In this step, the institution also needs to envisage training in a systematic and permanent way.

Alignment and insertion of ethics in institutional management systems: Includes implementing the Ethics Policy and its action plan to address the findings and deficiencies determined by the diagnosis. This action plan should be part of the strategic annual institutional plan of the institution (Planes Estratégicos Institucionales, PEI). Ethics should be mainstreamed in human resource management and other management processes, such as financial management, procurement, transfer of resources, granting of permits, administrative procedures, information management, managing conflict of interest or dealing with complaints amongst others.

Monitoring and evaluation: All implemented actions have to monitored and regularly reviewed in view of identifying corrective actions. The “Ethics Audits” promoted by the CGR and internal audit are part of this evaluation stage.

Even if issuing non-mandatory guidance, the CNEV, the CIEV and the MGE, can be considered as goo practices and a key step towards ensuring mainstreaming of public integrity in the whole of the public sector, including the central government, the autonomous bodies, decentralised sector and municipalities (OECD, 2017[21]). Currently, 84 out of 326 public institutions have implemented such a commission. Beyond the Central Administration, the CGR, the Ombudsman, the Judiciary, 9 municipalities and several institutions from the ADI have implemented a CIEV.

Nonetheless, the CNEV and the CIEV face several challenges.

First, the CNEV and the CIEV typically have capacity and financial constraints. Executive Decree 23944 of 1994 does not state whether CNEV or the CIEV will have funding or an administrative structure covered by the general budget. These challenges to fulfilling their mandate was confirmed during the fact-finding conducted by the OECD, where several stakeholders mentioned the lack of dedicated and specialised human resources and financial resources as main barriers an effective functioning of the CNEV and the CIEV.

Second, the members of the CIEV are public officials that are not exclusively dedicated to the commission. This comes along with challenges already highlighted in other contexts, in particular with respect to continuity, the development of specific knowledge and capacities as well as the ability to build trust relationships, which require time (OECD, 2017[43]; OECD, 2021[26]; OECD, 2019[40]). In fact, in a focus group carried out by the OECD, members from CIEV expressed the need to have support from the legal and human resources areas, as well as some basic training in relevant legal regulations. They also expressed the need to receive more guidance from the CNEV on integrity risk identification and management procedures. Out of the 65 CIEV, only five have a technical unit supporting the members of the commission and which could address some of the challenges mentioned.

Third, the mainstreaming of public ethics at organisational level requires strong political will from high-level management (“jerarcas”) to decide and support an effective implementation of the MGE. According to the OECD interviews and focus group, this political will and “tone-at-the-top” at the highest level is, however, often weak or absent. Ethics management is rarely seen as a priority by high-level management. Consequently, many institutions of the public sector are not implementing the MGE and those who do, often do not ensure that sufficient resources are dedicated to it.

Fourth, according to Decree 23944, the head of the entity (“jerarca”) designates the members of the CIEV and determines the number of its members. Once established, these members elect a president. The OECD interviews indicated that there is little to no guidance for the “jerarca” on how to select these members, as well as little guidance for the selected officials with respect to their roles and responsibilities. Indeed, the OECD interviews evidenced that some public officials in CIEV even misunderstand their role and want to push for a more punitive approach. This could create confusion and endangers the currently clear focus on prevention.

Costa Rica could address these issues, leveraging the solid foundation provided by the CNEV, the CIEV and the MGE, and move towards more robust and effective integrity management and integrity units, while maintaining the current clear focus on prevention and promotion of public ethics.

To do so, Costa Rica could consider, in the first place, a legal reform that provides a clear mandate for the CNEV and the CIEV, full co-ordination powers for the CNEV and appropriate resources for the functioning of both. As foreseen in the ENIPC, the reform should consider implementing the MGE, including the establishment of a CIEV, in all institutions of the Costa Rican public sector. As such, the CIEV could become the articulating link with the co-ordination commission recommended above to ensure that integrity policies are effectively implemented at organisational levels. Especially at the municipal level, the implementation of guidance on public ethics is incipient, but an increasing number of municipalities are making first steps in implementing ethics manuals and/or codes following the CNEV guidelines and some have implemented CIEV. The CNEV could take advantage of and learn from these already existing CIEV at municipal level and provide targeted guidance to the territorial levels.

Second, Costa Rica could start a dialogue on the possibility to transform the current CIEV into dedicated integrity units with full time and professionalised and specialised staff. This unit could either replace the CIEV completely, or if the commissions shall be maintained, could be the technical secretariat that supports the CIEV and leads the internal co-ordination of the implementation of the MGE. Such a unit could be inspired by emerging successful practices in Peru, with the implementation of the Integrity Model (Modelo de Integridad) and the Offices of Institutional Integrity (Oficinas de Integridad Institucional) (OECD, 2019[40]), or by Brazil, with the Public Integrity System of the Federal Executive Branch (SIPEF) including the establishment of Integrity Management Units (UGI) (OECD, 2021[26]). At a minimum, the guidelines issued by the CNEV should encourage high-level management to assign additional staff (a technical secretariat) and budget to the CIEV.

In addition, Costa Rica should strengthen both the CIEV and the MGE along several lines:

To signal an improved framework, the CNEV could consider moving from the use of “ethics management” to “integrity management”. Indeed, one high-level authority expressed concern during the OECD fact-finding about old-fashioned or religious connotations coming along with “ethics” in Costa Rica and that could undermine a broad acceptance amongst public officials. In fact, while earlier OECD publications refer to “ethics”, recent publications prefer the term “integrity” (OECD, 2009[36]). However, to avoid any confusion in Costa Rica, communication should emphasise that integrity management and units do not and should not have a role related to enforcement.

Indeed, the CNEV should continue to clarify that these units are entirely dedicated to prevention, promoting cultures of organisational integrity and ensuring the implementation of integrity policies within the public administration. CIEV (or potential future integrity units) should not be receiving complaints, investigating cases or much less have a role in sanctioning. International experience shows that such enforcement roles draw resources from prevention activities, creates confusion amongst public officials and undermines establishing the CIEV as a safe haven where public officials can raise concerns and doubts without fear of reprisal.

The current MGE, transformed into an Integrity Management Model (Modelo de Gestión de Integridad), could assign more explicitly to the CIEV (or potential future integrity units) the role of articulating internally different areas relevant to promoting an organisational culture of integrity and supporting the high authority and public managers. This support to public officials could focus in particular on providing orientation on managing conflict of interest (Chapter 3), identifying and dealing with ethical dilemmas and supporting integrity risk management. Articulation and co-ordination, in turn, is particularly relevant with existing or future disciplinary units (Chapter 5) and with the human resource units. These human resource units have recently been empowered by the LMEP and could play a key role in promoting integrity throughout the human resource management process and ensure capacity building through the planning of training opportunities for public officials. A revised Integrity Management Model could also provide clear criteria for indicators to monitor the implementation and evaluate the effectiveness of the MGE.

Finally, the CNEV could consider promoting a more active communication between the different CIEV (or potential future integrity units) and creating a bank of good practices that could help guide decision-making processes, including at the subnational level.

Third, the current practice of developing institutional Ethics Codes or Manuals allow to reflect the specific context of the respective institutions. However, despite that Decree 33146 of 2006 is regulating the “Ethical Principles of Civil Servants” (Principios Éticos de los Funcionarios Públicos), OECD interviews indicated a lack of a homogenous understanding of what are the shared principles and values of the Costa Rican public sector. Furthermore, the “Manual of Ethics for Civil Servants” (Manual de Ética en la Función Pública) was developed by the DGSC and sets policies for the 47 entities of the civil service regime. However, this Manual was not developed in co-ordination with the CNEV, evidences the sometimes lacking co-ordination in Costa Rica and further undermines a homogenous understanding of public ethics in the public administration.

Therefore, steered by the CNEV, Costa Rica could initiate a participative review and identification of shared ethical values for the whole public sector to promote clarity and build ownership. The CIEV (or potential dedicated integrity units) could then apply and if necessary complement those shared values to reflect the specificities of each institutional context. Costa Rica could be inspired by relevant participative approaches followed by several countries in defining core values and principles (Box 1.3). Such a process could also increase the commitment of high-level management to develop the necessary legal and institutional frameworks to implement these values as well as to lead by example and display high standards of personal propriety.

Box 1.3. Participative development of shared values in Australia, Brazil and Colombia

Australia

In the past, the Australian Public Service Commission used a statement of values expressed as a list of 15 rules. In 2010, the Advisory Group on Reform of Australian Government Administration released its report “Ahead of the Game”, which recognised the relevance of a robust values framework and a values-based leadership in driving performance. The report recommended that the Australian Public Service (APS) values could be revised, tightened, and made more memorable. The values were updated to follow the acronym “I CARE”: Impartial; Committed to service; Accountable; Respectful; Ethical.

Brazil

With support from the OECD, the Office of the Comptroller General of the Union (Controladoría Geral da União, CGU) led in 2020 a participative process to identify the core Values of the Federal Public Service in Brazil (Valores do Serviço Público Federal). After an extensive consultation process, civil servants identified which are today the seven Values of the Federal public service: Integrity, Professionalism, Impartiality, Justice, Engagement, Kindness and Public Vocation. Each value comes along with a brief description of what the value means, which provided the opportunity to add similar values that pointed into the same direction.

Colombia

In 2016, the Colombian Administrative Department of Public Administration (Departamento Administrativo de la Función Pública, DAFP) initiated a process to define a General Integrity Code. Through a participatory exercise involving more than 25 000 public servants through different mechanisms, five core values were selected: Honesty; Respect; Commitment; Diligence; Justice. In addition, each public entity has the possibility to integrate up to two additional values or principles to respond to organisational, regional and/or sectorial specificities.

Sources: Australian Public Service Commission, https://www.apsc.gov.au/working-aps/aps-employees-and-managers/aps-values; Departamento Administrativo de la Función Pública, Colombia https://www.funcionpublica.gov.co/web/eva/codigo-integridad; (OECD, 2021[26]).

Costa Rica could consider establishing co-ordination mechanisms at territorial level to reach out to municipalities and ensure integrity policies are informed by by the specific contexts and effectively implemented

To achieve impact in building a culture of integrity, reaching the territorial level, particularly municipalities, is key (OECD, 2019[24]). Therefore, Costa Rica could consider establishing co-ordination mechanisms at the territorial level that would complement the high-level co-ordination commission and its sub-commissions at the national level. The rationale for such co-ordination mechanisms consists in promoting the implementation of integrity policies and the MGE in municipalities. As such, these co-ordination mechanisms could include, beyond the CIEV, other relevant integrity actors at territorial level, mirroring the high-level commission recommended above. They would be the link with the commission at the national level and would, in the future, be responsible for steering territorial integrity plans (Chapter 2).

Box 1.4 provides information on similar arrangements in Peru and Colombia, which could inspire a solution responding to the Costa Rican context. In Costa Rica, however, the focus could be placed more on reaching the municipalities and could therefore be established at the level of the seven provinces or at the level of the eight Municipal Councils at district level.

Box 1.4. Peru’s and Colombia’s co-ordination arrangements at the territorial level

The Regional Anti-corruption Commissions in Peru

Regional Anti-corruption Commissions (Comisiones Regionales Anticorrupción, CRA) were established in Peru through Law 29976, which also created the High-level Commission against Corruption (Comisión de Alto Nivel Anticorrupción, CAN). The CAN is the national body promoting horizontal co-ordination and advancing the coherence of the anti-corruption policy framework in Peru.

The Peruvian model takes the institutional competences of its members as a fundamental premise for the articulation at the level of the CAN and the CRAs. The focus of both spaces is set on promoting strategic co-ordination and a joint policy formulation between all key integrity actors at the national and regional level. As such, the incorporation of regional governments in the CRA does not pose a threat to the role of control and investigation, but on the contrary, represents an opportunity to generate an integrated regional approach to confront corruption. The idea is that each actor brings in its own expertise, authority and realm of influence to implement activities that are nevertheless co-ordinated and aim to reinforce one another. While the initial outset to create these CRA is laudable by bringing together the different actors responsible for integrity, reforms are needed to make the CRAs more effective and sustainable without only relying on the political will and support of the heads of the entities comprising the CRAs (OECD, 2021[41]).

The Regional Moralisation Commissions in Colombia

Law 1474 of 2011, the Anti-corruption Statute (Estatuto Anticorrupción), redefined the legal framework to fight corruption and sought to strengthen mechanisms to prevent, investigate and sanction corruption in Colombia. Created by Law 1474, the Regional Moralisation Commissions (Comisiones Regionales de Moralización, CRM) are co-ordination bodies at departmental level. Together with the National Moralisation Commission (Comisión Nacional de Moralización, CNM), they are part of the Co-ordination Committee of the National Integrity System created by Law 2016 of 2020. Members are the regional representatives of the Inspector General, the Prosecutor General, the Comptroller General and the Council of the Judiciary (Consejo Seccional de la Judicatura) as well as the Departmental, Municipal and District Comptrollers (Contraloría Departamental, Municipal y Distrital). The CRMs are in charge of investigating, preventing and sanctioning corruption in the regions.

In many departments, they have achieved better co-ordination among the control authorities. They also have promoted training and awareness-raising activities or carried out joint audits in critical areas. Despite this initial progress, the CRM have not yet been able to deliver their full potential. In particular, their work to prevent corruption is limited as this would require and enhanced dialogue and co-operation between the CRM and the departmental and key municipal governments to co-ordinate corruption prevention activities (OECD, 2021[32]).