This chapter analyses the disciplinary enforcement mechanisms applicable in the Costa Rican public sector. In particular, the chapter focuses on the coherence of the institutional and legal framework, harmonisation of disciplinary processes and improved institutional co‑ordination. Although recent efforts attempt at addressing these issues, further policy reforms are required to improve the quality of disciplinary processes and ensure fairness through the uniform application of rules. The chapter provides recommendations for developing a set of common disciplinary rules for public officials, providing central guidance on their effective implementation and assigning disciplinary responsibilities to specific agencies and functions within entities.

OECD Integrity Review of Costa Rica

5. Towards a coherent disciplinary system in Costa Rica

Abstract

Introduction

A coherent and comprehensive public integrity system requires enforcement mechanisms to be credible and effective and avoid impunity that could undermine the rule of law, trust in institutions and could provide the breeding ground for more unethical practices, apathy, and cynicism. Enforcement mechanisms are the necessary “teeth” and the formal means by which societies can ensure compliance and deter misconduct. Therefore, the OECD Recommendation on Public Integrity calls on adherents to ensure that enforcement mechanisms provide appropriate responses to all suspected violations of public integrity standards by public officials and all others involved in the violations (OECD, 2017[1]).

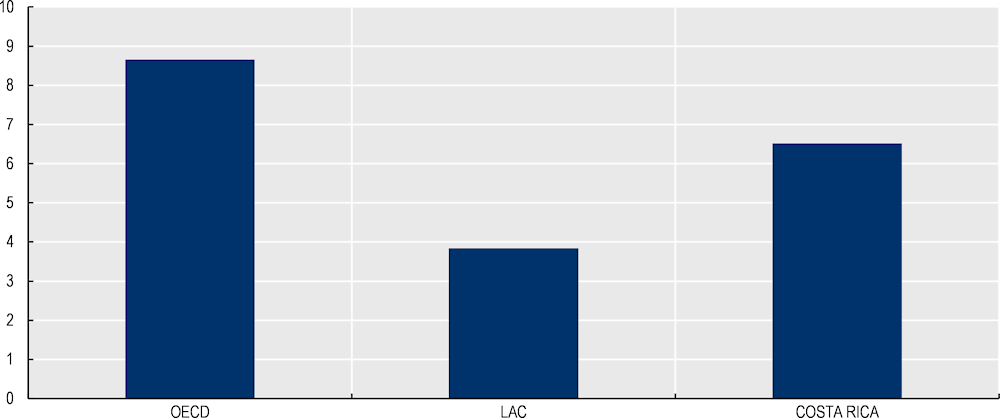

When examining the adequacy of enforcement mechanisms in promoting trust in the public integrity system as a whole, a key element to consider are the levels of perceived judicial independence. In Costa Rica, the judiciary is independent and the courts are widely trusted by citizens and the private sector (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2022[2]). The indicator for perceived Judicial Independence, as measured by the Index of Public Integrity, based on data from the World Economic Forum, shows that Costa Rica scores above the average of Latin American countries with available data, but below the OECD average (Figure 5.1). Compared to other countries in Latin America, according to Transparency International Global Corruption Barometer 2019, a majority of citizens (66%) also do not perceive judges and magistrates as corrupt. As far as formal guarantees of independence are concerned, due process rights are established in all criminal, administrative and civil processes by Articles 39 and 41 of the Constitution, as recognised by the Constitutional Chamber in resolutions numbers 15-1990 and 1739-92.

Figure 5.1. Perceived judicial Independence in Costa Rica, compared to OECD and Latin American average, 2021

Source: Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina, Ramin Dadasov, Roberto Martínez B. Kukutschka, Natalia Alvarado, Victoria Dykes, Niklas Kossow, and Aram Khaghaghordyan. 2021. Index of Public Integrity, European Research Centre for Anti-Corruption and State-Building (ERCAS).

This chapter focuses on the current disciplinary proceedings in Costa Rica. Disciplinary enforcement is grounded on the employment relationship with the public administration and the specific obligations and duties coming along with it. Breaching these obligations and duties leads to sanctions of an administrative nature, such as warnings or reprimands, suspensions, fines or dismissals. Disciplinary enforcement mechanisms help public administrations ensure effective accountability. They demonstrate that accountable institutions are liable for their decisions and actions and provide for a fair solution in cases of culpable breach of duty of their employees. Moreover, disciplinary sanctions communicates and reassures the validity of the norm. As a result, if carried out in a fair, co-ordinated, transparent and timely manner, disciplinary enforcement mechanisms can promote confidence in the government’s public integrity system, serving to strengthen its democratic legitimacy in relation to citizens’ expectations (OECD, 2016[3]; OECD, 2020[4]).

Overall, disciplinary enforcement plays an essential role within public integrity systems: it informs public officials’ daily work and activities more directly. In addition, the information generated by disciplinary systems have the potential to identify integrity risk areas where preventive efforts and mitigation measures are needed (OECD, 2020[4]).

Therefore, this chapter analyses in particular:

The extent to which integrity rules in Costa Rica are applied fairly, objectively and timely to all public officials.

The existence and effectiveness of mechanisms aimed at promoting co-operation and exchange of information between the relevant bodies, units and officials at the organisational, subnational and national level to avoid overlap and gaps.

How the disciplinary system in Costa Rica encourages transparency in relation to the effectiveness of the enforcement mechanisms and the outcomes of cases, in particular through developing relevant statistical data on cases.

Applying fairness, objectivity and timeliness in the enforcement of public integrity standards in the public administration.

Costa Rica’s framework for disciplinary sanctions is currently fragmented and does not cover the legislative branch

In Costa Rica, the General Law of Public Administration (Law 6227 of 1978, Ley General de la Administración Pública, LGAP) applies to all Costa Rican public institutions (323 as of March 2021). However, the LGAP, in article 367 excluded in matters of procedure what concerns personnel regulated by law or by autonomous work regulations. As a consequence, Costa Rica has a large number of specific institutional regulations with partial coverage (Box 5.1, see Figure 1.3 in Chapter 1 for an overview of the organisation of the Costa Rican public sector).

Box 5.1. Disciplinary frameworks in Costa Rica

Beyond the General Law of Public Administration (Law 6227, Ley General de la Administración Pública, LGAP), there are several regulations applying to specific areas of the Costa Rican public sector.

The Central Administration of the Costa Rican executive is regulated by the Civil Service Statute (Law 1581 of 1993, Estatuto de Servicio Civil) and establishes duties, obligations, disciplinary sanctions and special summary procedures. These are complemented by autonomous regulations of single Ministries, which govern the sanctioning procedures in greater detail. The Civil Service Statute applies only to public servants of the central administration’s executive branch paid by the public treasury and nominated by formal agreement published in the Official Gazette. Articles 3 and 4 exclude elected and appointed public officials, covering officials and employees who serve in positions of personal trust of the President or the Ministers, such as heads of diplomatic missions, the Attorney General, Provincial Governors, senior officials and ministry directors.

Public officials in the Foreign Service are regulated by Law 3530 (Foreign Service Statute - Estatuto del Servicio Exterior de la República).

The Police is regulated by Law 7410 (General Police Law - Ley General de Policía).

The territorially decentralised public administration (Administración Decentralizada Territorial), referring to municipalities, is regulated by Law 7794 (the Municipal Code). In addition, all 83 municipalities have their own Autonomous Service Regulations.

The institutionally decentralised public administration (Administración Decentralizada Institucional) does not have any regulation covering the 121 institutions and their 17 attached bodies. They have their own instruments for investigating, substantiating, and sanctioning misconduct, usually established in organic laws and Autonomous Service Regulations.

Finally, Law 2 (Labour Code, Código de Trabajo) applies to State owned and Non-State owned Public Enterprises.

Source: Information provided by Costa Rica through the OECD questionnaire.

Outside the public administration, the legislative, judiciary and the electoral bodies are covered by specific Laws:

The judiciary is covered by the Organic Law of the Judiciary (Law 7333, Ley Orgánica del Poder Judicial).

Public officials of the Legislative Branch are regulated by Law 4556 (Law on the Personnel of the Legislative Assembly, Ley de Personal de la Asamblea Legislativa). This Law does not apply to elected officials, however.

In the case of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, in addition to Law 3504 (Ley Orgánica del Tribunal Supremo de Elecciones TSE y del Registro Civil, Organic Law of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal), the personnel is regulated by the Autonomous Regulation of Services of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, based on Law 6227.

In addition to the LGAP and these specific regulations, there are other relevant Laws that cover the entire public sector: Law 7494 (Law on Administrative Contracting, Ley de Contratación Administrativa), Law 8131 (Law on Financial Administration of the Republic and Public Budgets, Ley de la Administración Financiera de la República y Presupuestos Públicos), Law 8292 (General Law of Internal Control, Ley General de Control Interno) and the Law against Corruption and Illicit Enrichment in the Public Function (Law 8422, Ley contra la Corrupción y el Enriquecimiento Ilícito en la Función Pública, LCCEI). These laws, together with the LGAP, are considered key instruments for the investigation, substantiation and sanctioning within their respective scopes. They cover all 326 public entities of the Costa Rican public sector, which must take them into account when developing their own procedures.

In particular, the LCCEI and its regulation (Decree 32333-MP-J of 12 April 2005) provide for additional violations, whose administrative sanctions are imposed by each public entity usually through their human resources or legal services. The de jure coverage of the LCCEI, just as the LGAP, is broad and aligned with Article 1 of the United Nations Convention against Corruption. The definition of public officials also includes elected and appointed public officials as well as any type of service or relationship or contact with the exercise of public functions.

Recently, Costa Rica has adopted a Law on Public Employment (Law 10159, Ley Marco de Empleo Público, LMEP), which aims to unify the public service regime applicable to all public officials in Costa Rica, including from autonomous and decentralised administration. The LMEP establishes the Ministry of National Planning and Economic Policy (Ministerio de Planificación Nacional y Política Económica, MIDEPLAN) as the leading entity for public employment and the Law enters into force on 10 March 2023. The scope of the law is broad and touches upon many issues related to the harmonisation of the Costa Rican civil service.

Amongst other reforms, the LMEP partially replaces the disciplinary processes established in the Civil Service Statute and defines in Article 21 a new set of rules on proceedings for disciplinary dismissal (Table 5.1). Nevertheless, these do not apply to the legislative and the judiciary, the electoral body and the autonomous entities. These autonomous entities can issue their own internal regulations or, if not existent, the following ones will apply: LGAP (Law 6227), public law rules and principles, the Labour Code and the Civil Procedure Code (Código Procesal Civil).

Appeals against sanctions others than dismissal can be lodged to the authority imposing the disciplinary dismissal, namely the head of the entity (jerarca institucional). In case of dismissals, officials under the Civil Service Statute can appeal to the Civil Service Tribunal (Tribunal de Servicio Civil), whose decision is final. Notably, the law does not indicate a specific deadline for notifying the decision of the head of the entity nor for the Civil Service Tribunal to resolve appeals lodged. However, article 352 of the LGAP is applied as a supplementary rule in both cases. Thus, the appeal case is concluded within 8 days according to the provisions of article 352 LGAP. In addition, the LMEP does not indicate which body will be responsible for appeals lodged by public officials working in institutions that are not covered by the Civil Service Statute. Overall, while the LMEP is indeed a step forward in the harmonisation of the legal framework, it only covers the proceedings for dismissal and its broad scope in Article 2 is again reduced to being applied only to the Central Administration according to Article 21.

Table 5.1. Comparative Overview of Costa Rica’s disciplinary dismissal process under the Civil Service Statute and LMEP

|

Dismissal process according to Civil Service Statute |

Dismissal process according to LMEP |

|---|---|

|

The Minister submits in writing the decision to dismiss the official to the Directorate General of Civil Service, stating the legal reasons and the facts on which it is based, except in the case of procedures for the dismissal of civil servants of the Ministry of Public Education, where the request is directed to the Civil Service Tribunal. |

Within a month after a head of an institution is notified, ex officio or by complaint, of a possible misconduct, a preliminary investigation is initiated. Upon conclusion of the preliminary investigation, the head of the institution may reach the decision to initiate the special administrative dismissal procedure |

|

The Directorate General of Civil Service informs the public official and gives him/her a non-extendable period of ten days from the date of receipt of the notification for defense. In case there no element of defense is raised, the official is dismissed. |

The single special administrative dismissal procedure is concluded within two months of its initiation, with the objective to ensure due process and its principles. The head of the institution appoints a body to lead the process, which shall formulate the charges in writing and shall provide the public employee with notice for a period of fifteen days, to examine all the evidence offered in an oral and private hearing. Within the indicated period, the public employee shall present, in writing, his or her defense and may offer any supporting evidence he or she deems appropriate. If the employee has not filed any opposition within the established time frame or if he/she has expressly stated his/her conformity with the charges against him/her, the head of the institution shall issue the dismissal resolution without further proceedings. |

|

If the charge or charges involve criminal liability or the reputation of the Ministry is at risk, the Minister may, in his initial note, order the provisional suspension of the person concerned from holding office, informing the Directorate General of the Civil Service thereof. |

If the charge or charges made against the employee or public servant imply criminal liability or when it is necessary for the success of the administrative disciplinary dismissal procedure or to safeguard the reputation of the Public Administration, the head of the institution may decree, in a reasoned resolution, the provisional suspension of the public employee. If criminal proceedings are initiated against the public employee, such suspension may be decreed at any time, as a consequence of an arrest or preventive detention order, or a final judgment with a custodial sentence. |

|

If the interested party objects within the legal time limit, the Directorate General of the Civil Service gathers the appropriate information, hears both parties, examines the evidence offered and any other evidence it deems necessary to order, within a non-extendable period of fifteen days. After that, it sends the file to the Civil Service Tribunal, which shall issue a ruling on the case. If the Tribunal deems it necessary, it may order an extension of the investigation, receive new evidence and take any other steps it deems appropriate for its better assessment. |

If the interested party objects within the legal time frame, the body directing the process shall resolve prior objections that have been presented and shall summon an oral and private appearance before the Administration, in which all pertinent evidence and arguments of the parties shall be admitted and received. Once the evidence has been examined, the preliminary objections filed within the ten-day period granted to oppose the transfer of charges have been resolved, and the conclusions have been presented by the parties or the period for such purpose has expired, the case file shall be duly investigated and the respective report shall be submitted to the head of the institution for the issuance of a final decision. The head of the institution shall decide to dismiss the public servant or shall declare the lack of merit, in which case the file is archived. However, if he/she considers that the misconduct has taken place, but that its seriousness does not warrant dismissal, he/she shall order an oral reprimand, a written warning or a suspension without pay for up to one month, depending on the seriousness of the misconduct. |

|

After the decision from the Civil Service Tribunal, the parties have a period of three working days to appeal it before the Administrative Tribunal of the Civil Service, whose decision will be final. |

The decision ordering the oral reprimand, written warning or suspension without pay for up to one month may be appealed before the body issuing the resolution, which will resolve the appeal for revocation. In case of public servants working in an institution covered by Law 1581, Civil Service Statute of May 30, 1953, and the appeal shall be resolved by the Civil Service Tribunal. The head of the institution shall submit to the Civil Service Tribunal, on appeal, the file of the corresponding administrative proceeding containing the sanction resolution as well as the resolution of the appeal for revocation, with an expression of the legal reasons and the facts on which both resolutions are based. |

Source: Developed by OECD based on the Civil Service Statute and LMEP.

When analysing the typology of sanctions in the legislation mentioned above, there is some degree of homogeneity. Nonetheless, differences exist in the multiple and diverse legal provisions regulating the exercise of disciplinary power with respect to the description of the offences and the details of the procedures. In ascending degree, the typical sanctions are:

Verbal (oral) reprimand (or warning or reprimand)

Written reprimand (or warning or reprimand)

Suspension from work without pay (salary)

Dismissal without responsibility, revocation of appointment or separation from public charge.

Costa Rica could develop a set of common disciplinary rules to streamline its overall disciplinary framework across the public sector and ensure fairness, clarity and a coherent level of disciplinary accountability

Fairness is key in safeguarding citizens’ and public officials’ trust in enforcement mechanisms and in the rule of law more generally. Adherence to fairness standards is particularly relevant in cases of integrity violations, which may have high political significance and impact, especially if top-tier elected and appointed officials are involved. The concept of fairness is overarching, encompassing a number of general principles of law, such as access to justice, equal treatment and independence of the judiciary. Homogeneity of integrity-related duties and responsibilities increases legal certainty and favour understanding and alignment of public officials with the expected ethical behaviours.

In Costa Rica, however, as emphasised in the previous section, the overall disciplinary framework is currently highly fragmented. While there is some degree of homogeneity among the types of sanctions provided for in the various laws and regulations, there are many differences across categories of public officials, in terms of not only procedure but also concerning the description of the offences contained in the various regulations.

This fragmentation and lack of homogeneity of the disciplinary framework was pointed out as a key weakness during the fact-finding mission interviews and a focus group conducted by the OECD with officials responsible for disciplinary enforcement. The officials emphasised that the lack of a uniform legal framework is one of the elements that undermines the efficiency and effectiveness of disciplinary enforcement. Costa Rica’s recently adopted National Strategy for Integrity and Prevention of Corruption (Estrategia Nacional de Integridad y Prevención de la Corrupción, ENIPC) also identifies this lack of a homogenous legal framework, especially concerning the sanctions, as one of the key weaknesses of disciplinary enforcement in the country that needs to be addressed (ENIPC action 2.4.1.). In fact, the 2021 Capacity to Combat Corruption Index emphasises that corruption challenges in Costa Rica are mainly caused due to the complex judicial proceedings and regulatory gaps in the country (Americas Society et al., 2021[5]).

Therefore, Costa Rica could ensure the alignment of the disciplinary framework and introduce greater homogeneity by developing a set of common rules applying to all public officials, which could then be complemented by regulations of specific entities or sectors. For example, the actors of the co-ordination mechanism proposed in Chapter 1 could be assigned the responsibility to prepare a legislative proposal aiming to achieving such an alignment.

The legislative proposal could seek to develop a new instrument addressing the subject matter in a more comprehensive way, including institutional issues relating to the assignment of disciplinary responsibilities, with the objective to introduce a uniform disciplinary framework applicable to the whole public administration. Alternatively, the reform proposal could take into account the existing legal framework and integrate a set of common disciplinary rules to the General Law of Public Administration (Law 6227 of 1978) which applies to the entire public sector, or the new LMEP. Finally, another option to consider could be the codification of the current disciplinary rules found in existing laws. This would address the issue of fragmentation and allow a more systematic arrangement of the applicable framework, thus ensuring clarity of law.

As for the elements to be harmonised, priorities could be given to:

The typologies of sanctions, as proposed by the ENIPC.

The criteria to define offences and a minimum set of offences to be sanctioned in any entity, including breaches of integrity rules and principles.

The standard proceedings for all types of offences with some basic procedural principles and due process rights to be guaranteed.

These rules could continue allowing justified exceptions for autonomous bodies, which should try, however, to align as much as possible their own regulations, especially with regards to due process principles, typologies of sanctions, basic offences and procedural foundations. As a result, Costa Rica would develop a uniform and coherent disciplinary system applying to the officials of the central and the decentralised administrations (both the territorial and institutional ones), which nonetheless would be able to take into account the specificity and autonomous status of some entities, as done in other OECD countries.

Indeed, in several countries disciplinary powers are exercised at the organisational level. However, guidance provided at the central level ensures a harmonised implementation of the disciplinary framework across the entire public administration. For example, the Civil Service Management Code in the United Kingdom recommends compliance with the Advisory, Conciliation and Arbitration Service (ACAS) Code of Practice on Disciplinary and Grievance Procedures and notifies departments and agencies that the code is given significant weight in employment tribunal cases and will be taken into account when considering relevant cases. The Australian Public Service Commission (APSC) has also published a comprehensive Guide to Handling Misconduct, which provides clarifications of the main concepts and definitions found in the civil service code of conduct and other applicable policies/legislation as well as detailed instructions to managers regarding the implementation of proceedings. In Brazil, the Comptroller General of the Union (Controladoria-Geral da União, CGU) provides various tools for guidance to respective disciplinary offices, including manuals, questions and answers related to most recurrent issues, and an email address to clarify questions related to the disciplinary system (OECD, 2020[4]). A similar approach is followed in Malta, where the Public Service Commission (PSC) is endowed with the power to provide rulings and direction on the interpretation of the regulations if the need arises, as well as to enquire into the disciplinary control exercised by Heads of Departments. The PSC also exerts a monitoring role to ensure compliance across line departments. To this end, it carries out on-the-spot compliance assessments and desk-based checks, on disciplinary/criminal cases instituted against public officers (Public Service Commission, 2021[6]).

Costa Rica could consider expanding the disciplinary authority of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal to include the imposition of sanctions for corruption-related violations and establishing a comprehensive set of disciplinary rules for members of Parliament

Sanctions are integral to meaningful regulation and to the overall legitimacy of a parliamentary regulation system. As in any fair disciplinary regime, sanctions for disciplinary violations committed by members of Parliament have to be proportionate to the severity of the offence and the number of infractions (OSCE, 2012[7]). To achieve this, parliamentary regulation systems may include a wide range of sanctions, from relatively weaker penalties that can be seen as “reputational”, through fines and temporary suspensions from office. The ultimate political sanction – loss of a parliamentary seat – should be reserved to very serious offences only (OSCE, 2012[7]).

In Costa Rica, the disciplinary framework applying to members of the supreme powers is regulated by Article 43 of Law 8422 for disciplinary violations related to corruption, which covers deputies, councilmen, municipal mayors, magistrates of the Judicial Branch and of the Supreme Court of Elections, and ministers of Government, The relevant sanctions are administered by the Comptroller and Deputy Comptroller General of the Republic (Contralor y Subcontralor Generales de la República), the Ombudsman of the Republic and the Deputy Ombudsman (Defensor de los Habitantes de la República y el Defensor Adjunto), the Regulator General and the Attorney General of the Republic (Regulador General y el Procurador general de la República), or the directors of autonomous institutions, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (Tribunal Supremo de Elecciones), the Supreme Court of Justice (Corte Suprema de Justicia), the Council of Government (Consejo de Gobierno), the Legislative Assembly (Asamblea Legislativa) or the President of the Republic, depending on the case.

Although Article 43 regulates disciplinary administrative liability of these public officials, the competence for the imposition of disciplinary sanctions regarding the indicated positions remains unclear since the adoption of the law in 2004 and even up to date. Consultations with stakeholders carried out for the purposes of this Integrity Review indicated that the reason for this institutional uncertainty is the lack of more specific rules or regulations. As a rule of thumb, the appointing authority has the competence to remove any public official in case of misconduct and, accordingly, to impose disciplinary sanctions. However, this general rule requires further technical legal instruments that would enable its implementation and thus, remains inactive in practice.

More specifically, while the Rules of Procedure of the Legislative Assembly (Reglamento de la Asamblea Legislativa) establish in Chapter II a disciplinary regime for deputies, this refers only to the imposition of sanctions in case the Assembly is unable to meet due to lack of attendance and does not establish any disciplinary liability for integrity-related violations. Apart from this, in the Legislative Assembly there is no mandate for the investigation of violations committed by deputies or any other regulation regarding their administrative discipline.

Under the current regime and according to Article 262 of the Electoral Code, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal is the instance that revokes the credentials of the president, the vice presidents of the Republic and the deputies to the Legislative Assembly, but only for causes established in the Constitution. Additionally, Article 43 of Law 8422 establishes that the Supreme Electoral Tribunal is also the authority imposing sanctions to members of the Supreme Powers for violations described in that law. However, this only applies for elected officials at the municipal level (Administración Decentralizada Territorial) and does not cover the deputies. This creates a regime of privilege in favour of deputies, who, unlike other public officials, are currently outside the application of the Law 8422, as they cannot be sanctioned with the loss of their credentials for violation of the duty of probity.

Recent initiatives (Bill 22226 and the draft reform of Article 112 of the Constitution) seek to address these gaps. According to these, disciplinary liability of members of Parliament is established and violations of duty may result to loss of credentials, in the cases and in accordance with the “procedures established by law”. Notably, the cases and procedures applicable have not yet been defined by law, thus creating a legal gap, hindering the enforcement of the sanction, and ultimately creating perceptions of impunity. Due to this legal gap, no specific instance is established for these cases, but rather the investigation is referred to the Attorney for Public Ethics (Procuraduría de la Ética Pública, PEP) and the Supreme Tribunal of Elections, as well as the Plenary of the Legislative Assembly, which are named as the competent bodies to apply the regime of liability of Members of Parliament for violations of the duty of probity and to impose the corresponding sanctions, according to Article 8 of the draft Bill 22226.

In addition to the above, according to Article 21 of the LMEP, the Legislative Branch shall apply the dismissal process foreseen for public officials in accordance with their internal regulations and their own laws or statutes, depending on the case. The reason for this is that the “self-regulation” regime applying to members of Parliament is enshrined in the Constitution. In that sense, the position of members of Parliament is incompatible with a hierarchical employment relationship, in which the head of the institution would oversee the disciplinary process, as is the case with other categories of public officials. Because members of Parliament are “directly appointed” by the people, there is no body of constitutional rank that has the power to impose sanctions on them. In so far it seems that while this is a step towards harmonising the various disciplinary provisions applying in different categories of public officials, it remains unclear how this can be implemented in practice in combination with the relevant constitutional provisions.

Although under the current legislative framework, all public officials fall under the regime of law 8422 and thus also its article 39 establishing administrative disciplinary sanctions, Article 40 of the Law requires that these sanctions are imposed by the body holding disciplinary authority in each public entity. In the case of the deputies and as explained above, this body remains yet to be determined. As a result, the current system is insufficient to guarantee the enforcement and promotion of parliamentary standards. To avoid cultivating a climate of impunity, Costa Rica could consider amending article 262 of the Electoral Code to expand the disciplinary authority of the Supreme Electoral Tribunal over deputies, so that it includes corruption related violations established in Law 8422. This will allow to streamline the disciplinary rules of Law 8422 through the Electoral Code, thus establishing the Supreme Electoral Tribunal as the disciplinary authority responsible for the imposition of sanctions to members of Parliament, including deputies, and avoiding any legal gaps arising from the special constitutional status of these officials. Indeed, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal would be constitutionally well equipped to undertake this role. In fact, according to Article 9 of the Constitution of Costa Rica, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal is equipped with the rank and independence of the Powers of the State and is exclusively and independently in charge of the organisation, direction and supervision of the acts related to elections, as well as other functions attributed to it by the Constitution and the laws. In addition, the Supreme Electoral Tribunal consists of members of the Supreme Court of Justice, which enables it to resolve complex constitutional issues arising from the enforcement of disciplinary regulations to members of the Parliament.

As a next step, Costa Rica could consider establishing a transparent procedure for scaling from softer to tougher measures as the severity of the offense increases. Having a consistent approach to imposing sanctions is vital to avoid any suggestion that their application is discretionary, to promote best practice and to guarantee that individuals covered by the integrity framework understand what is expected of them (House of Commons Committee on Standards, 2020[8]). Additionally, although no two cases of misconduct are identical, individuals have the right to be dealt with no more severely or more leniently than another in a similar set of circumstances (House of Commons Committee on Standards, 2020[8]). This could be achieved by defining in the Rules of Procedure of the Legislative Assembly a list of aggravating and mitigating factors that should be considered when revising cases to impose sanctions, including, for example, standard sanctioning thresholds, to the extent possible. Good practice from other jurisdictions can be used as a basis to propose a wide set of proportionate sanctions as well as the aggravating and mitigating factors that could be used to analyse specific cases (Box 5.2).

Box 5.2. System of sanctions for breaches of integrity-related violations by Members of Parliament

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, the Integrity Investigation Board receives and investigates complaints regarding violations of the Code of Conduct by MPs. If the Board establishes a violation of the Code of Conduct, a recommendation for a sanction can be made in the report that is sent to the Presidium (executive committee of the House of Representatives). Possible sanctions are clearly delineated in the Regulations on Supervision and Enforcement of the Code of Conduct for Members of the House of Representatives of the States-General, under Chapter 5: Sanctioning. These include:

an instruction, a measure that obliges a MP to rectify a violation of the Code of Conduct,

a reprimand, including a public letter from the Presidium addressed to a MP in which the act that led to a violation is rejected, and

a suspension, including the exclusion of a MP for a period of up to one month from participation in plenary sittings, committee meetings or other activities held by the House.

Additionally, the explanatory notes of the Regulations provide more details outlining in which circumstances certain sanctions are utilised. For instance, reprimands can be seen as a warning to the MP, while suspension is the most severe form, which is only utilised in the event of a breach of secrecy or confidentiality. The Regulations also stressed that the sanction of suspension is flexibly framed so that the measure can be tailored appropriately and proportionately to the nature and severity of the violation.

United Kingdom

In its report Sanctions in respect of the conduct of Members (2020), the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards of the United Kingdom sets out a table listing sanctions recommended in individual standards cases since 1995, which are considered to be useful and meaningful sanctions for MPs who are found to be in breach of the Code of Conduct for MPs. The sanctions are arranged in, approximately, ascending order of seriousness:

|

Possible sanction or remedy |

Notes |

Decision making body |

|---|---|---|

|

Words of advice or warnings given by Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards or others |

Warnings to remain active for twelve months |

Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards |

|

Requirement to attend training Training courses include:

Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards to be able to require MP to attend other bespoke training or coaching as decided |

Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards to receive report from provider of training on attendance and engagement of MP and to follow up one year after training completed. |

Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards |

|

Letter of apology to complainant (ICGS only) or to Committee |

Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards to approve text in ICGS cases |

Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards |

|

Apology on point of order or by personal statement (formal apology in the Chamber) which (in ICGS cases) might be in conjunction with letter of apology to complainant |

Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards to approve text of letter Committee on Standards to require personal statement apology |

Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards |

|

Withdrawal of services / access from MP (not from office or constituents), for example exclusion from catering facilities or library Services. (Could be used in ICGS cases) |

In conjunction with security team / catering staff / library staff Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards to decide on length of exclusion |

Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards |

|

MP not to be permitted to serve on Select Committee |

Committee on Standards to decide on length of exclusion |

Committee on Standards |

|

MP not to be permitted to travel abroad on parliamentary business |

Committee on Standards to decide on length of exclusion |

Committee on Standards |

|

MP to repay part or all of cost of investigation |

Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards to decide/advise on the sum to be repaid |

Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards / Committee on Standards |

|

MP to be suspended from service of the House, without pay |

House of Commons, on recommendation from Committee on Standards |

|

|

MP to be expelled |

House of Commons, on recommendation from Committee on Standards |

Additionally, drawing on the Committee’s past conclusions in a range of cases, the Parliamentary Commissioner for Standards proposes a list of aggravating and mitigating factors:

|

Aggravating factors |

Mitigating factors |

|---|---|

|

Non-cooperation with the Commissioner or the investigation process; concealing or withholding evidence |

Physical or mental ill health, or other personal trauma |

|

Seniority and experience of the Member |

Lack of intent to breach the rules (including misunderstanding of the rules if they are unclear) |

|

Racist, sexist or homophobic behaviour |

Acting in good faith, having sought advice from relevant authorities |

|

Use of intimidation or abuse of power |

Evidence of the Member’s intention to uphold the General Principles of Conduct and the Parliamentary Behaviour Code |

|

Deliberate breach or acting against advice given |

Acknowledgement of breach, self-knowledge and genuine remorse |

|

Motivation of personal gain |

|

|

Failure to seek advice when it would have been reasonable to do so |

|

|

A repeat offence, or indication that the offence was part of a pattern of behaviour |

|

|

Any breach of the rules, which also demonstrates a disregard of one or more of the General Principles of Conduct or of the Parliamentary Behaviour Code. |

Strengthening the institutional framework and promoting mechanisms for co‑operation

In view of developing a uniform disciplinary system, Costa Rica could mandate the MIDEPLAN as the lead agency issuing overall disciplinary enforcement policies, including the development of centralised guidance to entities with technical support from the General Directorate of Civil Service

Disciplinary systems require the leadership of an entity or body in charge of guiding disciplinary areas to ensure uniform application of related rules and sanctions. According to the OECD experience, these actors are commonly in charge of supporting co-ordination and providing advice through channels for continuous communication and organising venues for regular meetings with entities. In addition, they are often well positioned to strengthen the capacity of disciplinary areas and to support them in building and sustaining cases when needed. In particular, those co-ordinating entities can provide tools and channels to guide and support investigative bodies in preparing cases through guides, manuals, or other tools to establish contact, such as dedicated hotlines or electronic help desks addressing doubts or questions related to disciplinary matters and procedures.

Costa Rica does not currently have a central institution leading on disciplinary matters for the whole public administration. However, as mentioned above, the new Law on Public Employment (LMEP) assigns the stewardship of the General Public Employment System to the MIDEPLAN, which also has the steering role of public employment pursuant to Law 9635 of 2018.

Based on this decision (and the decision against a dedicated Ministry of Public Employment), and given the responsibilities assigned to the MIDEPLAN that are potentially relevant for the disciplinary function (Box 5.3), it would be straightforward to assign the steering of the disciplinary regime to the MIDEPLAN. Indeed, based on its mandate, the MIDEPLAN establishes, directs and co-ordinates general policies, provides advice and support to all public institutions and defines guidelines and administrative regulations aimed at the unification, simplification and coherence of employment in the public sector. In relation to disciplinary enforcement, the MIDEPLAN is already planning to create a platform under its mandate, which could be used to give the institutional planning units the responsibility to develop disciplinary processes under the MIDEPLAN guidance.

Box 5.3. The MIDEPLAN’s responsibilities in the Law on Public Employment related to disciplinary measures

Establishing, directing and co-ordinating the issuance of public policies, national public employment programmes and plans.

Issuing general provisions, guidelines and regulations aimed at the standardisation, simplification and coherence of public employment.

Managing and keeping the integrated public employment platform up to date.

Directing and co-ordinating the execution of inherent competences in the field of public employment.

Collecting, analysing and disseminating information on public employment of the entities and bodies for the improvement and modernisation of these.

Co-ordinating with the Attorney Office of Public Ethics to issue general provisions, guidelines and regulations for the instruction of public servants on the duties, responsibilities and functions of the position, as well as the ethical duties that govern the public service.

Source: Law on Public Employment (Law 10159, Ley Marco de Empleo Publico, LMEP).

In turn, the General Directorate of Civil Service (Dirección General del Servicio Civil, DGSC) has been developing technical competencies on processes of the human resources management system in the Civil Service Regime and could continue to assume a technical leadership in support to the MIDEPLAN and public entities. As such, its functions under the current regime include the recruitment and selection of administrative, artistic and teaching posts, performance management, training, provision of technical assistance, classification and appraisal of posts, human resources auditing and dismissal, as well as permanent advice at political-economic levels. With specific regard to disciplinary enforcement, pursuant to the General Law of Public Administration, the DGSC is part of the summary proceedings. In particular, it receives the dismissal requests from public entities, gives the accused the possibility to intervene and submits the file to the Civil Service Tribunal for final decision. In this context, the DGSC provides guidance on this to entities, as done for example in relation to the presentation of dismissal requests to the Directorate itself (Circular DG-CIR-010-2018, Lineamientos para la presentación de la “Gestión de Despido” ante la DGSC), which was issued in 2018 to address inconsistencies in documents with the objective to improve the process and to ensure its efficiency.

With regards to the changes brought under the recently introduced LMEP and according to Article 23c of the Law, the Training and Development Center (Centro de Capacitación y Desarrollo, CECADES) of the DGSC, in strict adherence to the guidelines issued by the MIDEPLAN, will be in charge of providing technical assistance, monitoring and controlling the training activities carried out the institutions covered by the Civil Service Statute, with the exception of the teaching sector. Furthermore, as described above, the LMEP introduced some changes to the disciplinary dismissal process, which affects the current mandate of the DGSC, but it does not prevent it from using its technical expertise to support the MIDEPLAN in providing central guidance on the implementation of disciplinary processes. In fact, DGSC is rightly placed to undertake this supporting role in the field of its competences so far, as one of the key pillars of the General System of Public Employment according to Article 6 of LMEP.

Overall, providing centralised guidance on disciplinary issues and processes through MIDEPLAN with technical support from DGSC would help avoid inconsistencies arising from the autonomy of decentralised bodies and special categories of public officials, such as the judiciary and the legislative branch. With due consideration of the different applicable regimes, the oversight and co-ordination provided under the leadership of MIDEPLAN will help ensure a more uniform application of the disciplinary system in addressing common challenges and promoting the exchange of good practices. This can be achieved through the establishment of channels for continuous communication and venues for regular meetings with entities with the view to strengthen the capacity of disciplinary enforcement officials and support them in building and sustaining cases.

Furthermore, MIDEPLAN in cooperation with DGSC could consider providing entities with tolls and channels to guide disciplinary officials in preparing cases consistently, such as guides, manuals, or other tools to establish direct contact (e.g. dedicated hotlines or electronic help desks addressing doubts or questions regarding disciplinary matters and procedures. Administrative judges with experience in disciplinary matters from a judicial perspective could be engaged to support with the development of the guidance materials, in order to ensure that the rights of the accused are safeguarded across the Costa Rican public sector by use of key concepts of administrative due process that could be applied consistently.

The MIDEPLAN could introduce criteria for assigning disciplinary responsibilities to a specific function within entities

Enforcement actions should only be taken based on the law, and those enforcing the law should therefore, act objectively. Objectivity should apply through all phases of all enforcement regimes. In disciplinary proceedings, decisions – at least at the first instance level – are usually taken by administrative bodies, which are not always judicial in nature. Since members of those disciplinary bodies are not judges but civil servants, procedural safeguards should be in place to guarantee that their actions are free from internal or external influence, as well as from any form of conflict of interest (OECD, 2020[4]).

At a minimum, these procedural safeguards can include the following components:

Outlining the mandate and responsibilities of disciplinary institutions as a clear basis for their existence.

Ensuring that personnel responsible for disciplinary proceedings are selected based on objective, merit-based criteria (particularly senior-level positions).

Ensuring that personnel responsible for disciplinary proceedings enjoy an appropriate level of job security and competitive salaries in relation to their job requirement.

Ensuring that personnel responsible for disciplinary proceedings are protected from threats and duress, so as to not fear reprisals.

Ensuring that personnel responsible for disciplinary proceedings have autonomy in the selection of cases to take forward.

Ensuring that personnel responsible for disciplinary proceedings receive timely training in conflict-of-interest situations and have clear procedures for managing them.

In Costa Rica, the LMEP assigns new responsibilities and decision-making powers relating to the disciplinary process to each public entity. In fact, according to Article 21 of the LMEP (Table 5.1), the head of each public entity is exclusively responsible for reaching the decision to launch a preliminary investigation to examine the merit of a complaint about a possible misconduct and to determine whether the special administrative dismissal procedure should be carried out. While this is a common approach across many jurisdictions (e.g. Malta, Mexico, Thailand), the above procedural safeguards could be applied as a checks and balances mechanism to ensure the objectivity of decisions taken and the integrity of the disciplinary process.

Especially in small sized entities, there is a risk that personal ties of officials involved in the disciplinary proceedings might affect the outcome of cases. One way of ensuring the principle of fairness in disciplinary proceedings would be to equip the accused person with the right to object to the body appointed by the head of the institution to lead the special administrative dismissal procedure if, for example, there is a personal involvement or connection with any of its members or other causes that would prevent impartiality (OECD, 2021[10]). In Costa Rica, this is ensured through the institute of recusal established in the Articles 230 and following of the LGAP, which allows the public official subject to the disciplinary process to request the removal of civil servants appointed as the governing body on grounds of impartiality.

Overall, principles and guarantees of fairness should be mentioned explicitly in any guidance tools or regulations regarding disciplinary proceedings with the objective to uphold the highest integrity standards and prevent any form of undue influence that may jeopardise the validity of disciplinary decisions. A relevant good practice can be found in the General Guidelines for the analysis of alleged irregularities in the framework of internal audits of the Office of the Comptroller General in Costa Rica. The General Guidelines establish the principles of investigating alleged misconduct, including the principle of legality, timeliness, independence and objectivity (Office of the Comptroller General, 2019[11]). Similarly, the Manual on Disciplinary Cases of the Public Service Commission of Malta states that the disciplinary board investigating the case should ensure that it carries out its functions fairly and impartially throughout the hearing of the case (Public Service Commission, 2021[6]).

In the context of the Costa Rican disciplinary framework, the lack of specific criteria for placing or structuring an area in charge of disciplinary authority may create risks to the impartiality and objectivity of the process. Indeed, the only reference in relation to the disciplinary function within public entities is that the power to impose a disciplinary sanction rests in the hierarchy of the respective institution. The MIDEPLAN issued the Nomenclature Guide for the Internal Structure of Public Institutions and the Guide for Administrative Manuals (Guia de Nomenclatura para la Estructura Interna de las Instituciones Publicas and Guía de Manuales Administrativos), but neither of them refers to an area in charge of disciplinary authority.

In practice, the head of the entity typically assigns the investigation and substantiation of disciplinary proceedings to the legal or human resources areas, which are de facto in charge of the disciplinary function. However, the decision-making power regarding the launch of the investigation and the administrative dismissal procedure lies with the head of the institution. Some public entities have established specific administrative units for disciplinary procedures, such as the Ministry of Public Education, the Ministry of Public Security, the Ministry of Finance, the National Registry, the Judiciary and the Ministry of Justice. Experience from the Brazilian public sector has shown that this approach of establishing dedicated disciplinary areas within entities works well in practice.

Drawing from the practice of these Ministries and to further guarantee the objectivity of disciplinary enforcement, but also to give it greater visibility and prominence within public entities, the MIDEPLAN could take gradual steps to formalise and develop disciplinary areas in public entities. For that purpose, it could identify entities, which are more at risk of disciplinary breaches, including integrity breaches, as well as public entities that have developed a more advanced institutional model, which could be considered as a model for replication elsewhere. Based on that, the MIDEPLAN could gradually require the establishment of a disciplinary area in public entities if certain criteria are met. These criteria could include the level of risks but also the size of the entity, for example.

For entities that would not be required to have a dedicated disciplinary area, additional guidance should be provided as to the minimum requirements to be followed in terms of capacity and expertise when the disciplinary function is assigned to other areas such as legal affairs or human resources management. These criteria and requirements could be established, for example, in the Nomenclature Guide for the Internal Structure of Public Institutions.

In case of very small entities or small municipalities with very few resources, Costa Rica could explore providing disciplinary services through shared services (OECD, 2021[10]). As far as the shared model is concerned, several countries have been implementing similar approaches in the field of internal audit, to address challenges arising from reduced budgets. For example, the UK has been working on developing a shared audit services model by consolidating internal audit services, moving from the departmental structure to a single integrated audit service, the Government Internal Audit Agency (GIAA). The GIAA is responsible for providing individual departmental audit and assurance services across government and the development of the profession across government. This model could be used in an adapted version for establishing dedicated but shared disciplinary offices that would be legally authorised to carry out disciplinary investigations. The principle behind creating shared offices is to have sufficient numbers of disciplinary investigators grouped for the development of capabilities. Moreover, it results in various benefits deriving from the building of expertise, leading practices and improving the efficiency and quality of the overall system while reducing the financial cost (OECD, 2017[12]; OECD, 2021[10]).

When developing the criteria for the assignment of disciplinary responsibilities to a specific function within entities, particular attention should be paid to clearly separating the disciplinary function from ethical management. As elaborated in Chapter 1, the Costa Rican public sector is implementing an ethics management model (Modelo de Gestión Ética, MGE) with the support of the National Commission for Ethics and Values (CNEV) and the Institutional Commissions on Ethics (CIEVs), which are the implementing bodies of the CNEV in ministries and agencies of the executive branch. CNEV and CIEV promote ethics in the public sector and are responsible for providing relevant guidance through the development of an Ethics Code or Manual, communication campaigns and ethics training programs among others. Their role, which aims at building a trusting relationship, should remain clearly distinct from disciplinary issues and enforcement policies, which are by nature distrustful (OECD, 2018[13]). Therefore, disciplinary authority at the entity level should be exercised by a different function and CIEV units should not be involved in any stage of the disciplinary process.

Costa Rica could increase the capacity and stability of staff working on disciplinary matters and of the Civil Service Tribunal

The fair enforcement of a sanctioning regime also depends on adequate investigative resources and skilled staff. Providing training and building the professionalism of enforcement officials helps address technical challenges, ensures a consistent approach, and reduces the rate of annulled sanctions due to procedural mistakes and poor quality of legal files. This can be achieved through guidance and training that builds knowledge of how different regimes function and can be used in parallel with each other, and that increases capacity to use special investigative techniques for integrity violations. Capacity-building activities can also focus on strengthening technical expertise and skills in fields such as administrative law, IT, accounting, economics and finance – which are necessary areas – to ensure effective investigations. In practice, many enforcement authorities face challenges in recruiting adequate staff and attracting specialised experts. However, capacity costs should be weighed against the costs of non-compliance, such as the decline in accountability and trust as well as the direct economic losses (OECD, 2018[14]).

As described above, in Costa Rica those who actually carry out disciplinary proceedings within entities, such as developing disciplinary files and materials, are typically officials belonging to areas, which vary from one institution to another, most commonly located in units responsible for human resource management and legal services. According to the information collected through the OECD questionnaire, to support disciplinary areas in carrying out these proceedings, the Comptroller General Office, the Attorney General Office and the Judiciary offer training courses on the exercise of disciplinary powers as a tool to strengthen institutional capacities. Apart from this specific activity, each institution defines training needs. In the case of the Executive Branch, in the Central Administration covered by Law 1581, there are Institutional Training Plans (Planes Institucionales de Capacitación, PIC) where all the needs are integrated. The Directorate General of the Civil Service’s Centre for Training and Development (Centro de Capacitación y Desarrollo, CECADES) is in charge of providing the training units or equivalent units of the Executive branch with the advice and technical support necessary for the effective fulfilment of their functions. While some Institutional Training Plans identify the ‘administrative and disciplinary proceedings’ among their training needs, (e.g. the Institutional Training Plan 2021 of the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock) there seems no regular programme or activity devoted to build capacity of officials dealing with disciplinary matters.

The need to strengthen disciplinary capacity in public entities has been emphasised during a focus group discussion with officials with disciplinary responsibility pointed out to the lack of a capacity-building plan on the matter, as well as the more general need to increase the human, financial and technological capacity of officials working on disciplinary matters. As raised by the focus group, this capacity gap affects the quality of legal documents, whose weaknesses eventually lead to cases not complying with procedural rules and standards, and thereby being annulled. A related and more general issue is the level of staff rotation which is a further obstacle to build capacity and retain knowledge and experience in carrying our disciplinary proceedings, which eventually affects the efficiency of disciplinary enforcement, levels of impunity and the respect of due process rights. Similar challenges concern the staff of the Civil Service Tribunal, which counts 3 official judges and 3 alternate judges as well as X officials to deal with an average of 200 cases per year. In addition, these judges are currently not employed full time, which does not only prevent the development of knowledge and expertise, but also creates a risk for the objectivity of their decision-making. This will change, however, with the entry into force of the LMEP, which transforms the Civil Service Tribunal into a permanently staffed institution. Indeed, the lack of training and capacity building activities is a critical shortcoming and initiatives to address this should be given a strategic vision, for example by developing the relevant activities centrally under the leadership of MIDEPLAN in cooperation with the DGSC, as elaborated in previous sections. In addition, strategic planning of such activities should take careful consideration of possible duplication of functions, and make use of existing structures and resources.

Some of the challenges, such as the high level of staff rotation, concern the broader public employment framework of Costa Rica. At the same time, some specific efforts could be made to strengthen the capacity of disciplinary areas, also considering the changes brought to the legal framework through the LMEP. First, public entities could ensure that they are adequately staffed with officials dealing with disciplinary enforcement and promote, to extent possible, stability and development of relevant knowledge and experience. Second, they could offer more continuous support and have courses on ‘administrative and disciplinary proceedings’ organised on a regular basis to train new staff and build capacity of the disciplinary function, especially in cases where rates of staff rotation are higher. In this context, CECADES – in co-ordination with the MIDEPLAN and the DGSC – could offer technical support and develop standard courses and materials on disciplinary enforcement, which could then be adapted and further developed by single entities. For this purpose, they leverage the potential of virtual resources and develop both an online repository of key materials as well as a set of on-line courses as done in Brazil (Box 5.4). The development of these resources in Costa Rica could first focus on foundational issues and then address on needs and priorities identified by disciplinary areas and officials. Furthermore, the standardisations of legal documents (e.g. templates of decisions, investigation documents, etc.) could contribute to speed and transparency and improve their quality, thus avoiding potential annulments due to non-compliance with procedural rules and standards.

Box 5.4. Disciplinary knowledge and on-line courses in Brazil

The Comptroller General of the Union (Controladoria-Geral da União, CGU) has developed a Programme for Development and Continuous Improvement in Internal Affairs. The Programme includes specialised online courses on the anti-corruption law, relevant sanctions and key elements of the disciplinary administrative process covering the following topics:

Federal Executive Branch Correction System.

Disciplinary Law – legislation principles, duty to investigation, legal accountability.

Disciplinary Responsibility – requirements, subjective and objective scope.

Investigative and Accusatory Procedures – Preliminary Summary Investigation, Investigative Inquiry and Property Inquiry, Accusatory Inquiry and Disciplinary Administrative Proceedings.

Administrative Disciplinary Process – phases, procedural communications, legal frameworks, sanctions and Final Report.

Data processing: Access to Information Law and General Data Protection Law.

The course modules provide practical guidance on the disciplinary process regarding the admissibility of evidence, preliminary investigations, composition and requirements for members of investigative and prosecution committees, methods of procedural communications, burden of proof, confidentiality issues and statutes of limitations among others.

In addition, the CGU provides an open Knowledge Base, which is freely accessible online. The Knowledge Base is open to contributions from all correctional units in the country and gathers norms, manuals, jurisprudence, good practices, procedures and other information relevant to the disciplinary process of the Federal Executive Branch.

With reference to the Civil Service Tribunal, which according to the LMEP will become the only appeal instance, its capacity could be strengthened by progressively increasing the number of appointed full time judges, increase its staff proportionally with the number of cases being dealt with, and provide adequate technical capacities and tools to eventually adapt to the changes that the draft civil service law may bring. This support should continue to ensure the autonomy of the Tribunal and not influence in any way its decision-making processes.

It should be noted that currently, some entities lack a second instance in disciplinary proceedings (e.g. ARESEP). This is a critical inconsistency caused by the interim regime currently in force until the implementation of the LMEP. More specifically, the LMEP establishes in Article 49D that the Administrative Tribunal of Civil Service will be mandated to resolve, within a period of two months, the appeals that are lodged against decisions of the Civil Service Tribunal, excluding the issue of dismissals, which are currently heard in sole instance, as well as other matters submitted to it by law. According to fact-finding interviews conducted for the purposes of this Integrity Review, the law with this amendment leaves the Administrative Tribunal of Civil Service practically void of functions, because on the one hand, there are no appeals to be examined that are not related to the issue of dismissals, and on the other hand, the law does not specify the “other matters submitted to it by law”. At the same time, additional inconsistencies are caused as the LMEP does not amend the legal provisions currently in force according to which, the Civil Service Tribunal rules in sole instance (e.g. Article 14 of the Statute currently in force).

In order to ensure that all public sector entities have established a second instance of appeal and to avoid any possible waste of the resources of the Administrative Tribunal of Civil Service, the Civil Service Tribunal could strengthen its capacity by establishing a two-chamber system to examine appeals coming from the statutory regime and those coming from the decentralised public sector..

The need to strengthen disciplinary capacity is also underscored by the ENIPC, which has set – among its objectives – the promotion of awareness-raising, education and continuous training activities on the disciplinary regulations that sanction non-compliance with the duties of public service, improper, fraudulent and corrupt conduct, in order to ensure the effective handling of administrative disciplinary procedures and the imposition and enforcement of sanctions. For this purpose, the ENIPC defined as one of its actions to “empower the body responsible for the implementation of the sanctions process” with the aim to improve the effective and compliant application of the disciplinary framework.

Costa Rica could establish mechanisms and digital tools facilitating investigative co-ordination and co-operation between disciplinary bodies and other areas or actors in charge of administrative and criminal enforcement

Authorities responsible for disciplinary enforcement may become aware of facts or information relevant to another enforcement regime and they should notify them with fact and information that may be relevant to establish other kinds of responsibilities. This exchange of information should flow both ways, with other enforcement entities informing disciplinary authorities. Co-ordination mechanisms are thus vital to ensure that information is swiftly exchanged and enforcement mechanisms are mutually supportive. This is recognised by international instruments, which require state parties to take measures to encourage co-operation with and between their public authorities and law enforcement, both proactively (whenever an authority comes across a possible corruption offence) and upon request of the investigating and prosecuting authorities (United Nations, 2003[15]; Council of Europe, 1999[16]). Mechanisms for co-ordination among relevant institutions also help identify common bottlenecks, ensure continuous exchange of experiences, and discuss formal or informal means to improve enforcement as a whole.

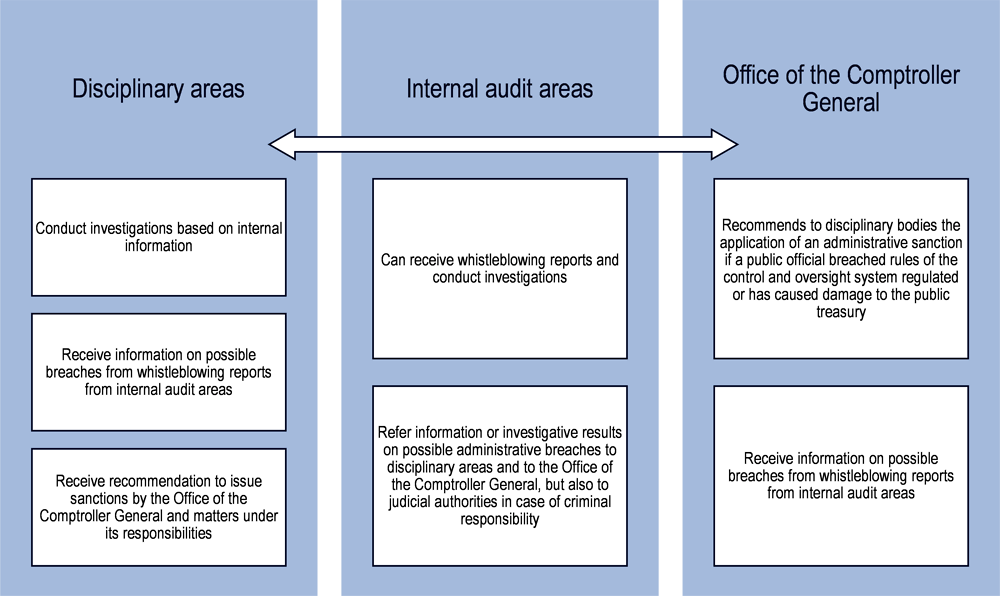

In Costa Rica, beyond the internal disciplinary competence of the head of the entity and managers, the legal framework gives the possibility to investigate administrative irregularities in the public service to the internal audit function of entities and to the Office of the Comptroller General (CGR) depending on the subject matter. The CGR can recommend to the competent body the application of an administrative sanction – warning, suspension and dismissal – if a public official breached rules of the control and oversight system regulated by Law 7428 of 2004 or has caused damage to the public treasury. The competent authority has to comply with the recommendation issued by the CGR, unless, within eight working days from the date of communication of the act, a duly reasoned and substantiated request for review is filed by the head of the entity. The CGR may issue a reasoned resolution declaring the civil liability of a public official and its pecuniary amount when it ascertains a damage against public funds, arising from a flagrant and manifested illegal act.

Next to the CGR, each public entity has to count with an internal audit function reporting to the head of the entity but also receiving technical guidance and oversight from the CGR. Its main function is, pursuant to Law 8292 of 2002, to perform the independent, objective and advisory activity that provides assurance to the entity or body to validate and improve its operations, as well as to contribute to the achievement of the institutional mission and objectives. Based on Law 7428 and Law 8422, the internal audit function is empowered to deal with complaints submitted by citizens, establishing the duty to maintain confidentiality with respect to the identity of the complainants and those under investigation, as well as the information, documents and other evidence gathered during the formulation of the report or investigation. As such, internal audits have the power to carry out investigations in response to the presentation of a complaint, at the request of an administrative body or even ex officio. In practice, this means that the investigations carried out by the internal audit functions are used as an input for the head of the entity to assess the possibility of opening an administrative procedure, without prejudice to any other action that is deemed appropriate. In this context and as already mentioned before, the CGR has developed a set of “General guidelines for the analysis of alleged irregularities” (Lineamientos Generales para el análisis de presuntos hechos irregulares) which provides a basic framework for the proper and transparent execution of the investigative work of public sector audits within the scope of internal audit functions’ competencies, also covering issues of co-operation and collaboration. (Office of the Comptroller General, 2019[11]) (Box 5.5)

Box 5.5. Guidelines on investigative co-ordination and co-operation for internal audit areas

With respect to co-ordination and collaboration, the guidelines establish that in the course of investigations, internal audits may provide support to each other, such as advice, inputs, or exchange of experiences. Depending on the case, joint analysis may be carried out, which however does not compromise the autonomy of each audit. Likewise, any other entity or body of the public administration may support the internal audits in the analysis of allegedly irregular facts.

At the same time, the guidelines establish that after the initial analysis of each case, the internal audit unit may proceed with the following actions:

Refer the matter to the relevant internal authorities of the institution in cases, which should be dealt with in the first instance by the Active Administration (administración activa) and the latter has not been made aware of the situation, or is conducting an investigation into the same facts.

Refer the matter to external administrative or judicial authorities, in case this is deemed necessary due to the particularities of each case or in case there is an ongoing investigation about the same facts.

When the investigative procedures demonstrate the existence of sufficient elements to consider – at least to a degree of probability – the occurrence of alleged disciplinary violations, the internal auditor shall prepare a statement of facts. The statement shall be forwarded to the body exercising disciplinary authority or to the competent authority for its attention, as appropriate. The same process is also followed in case of suspected crimes, where the internal auditor is required to prepare a criminal complaint. The complaint is then forwarded to the Public Prosecutor’s Office for further action.

Finally, according to the Guidelines, when Internal Audit prepares a statement of facts or a criminal complaint, it has a duty to co-operate with other competent authorities at all subsequent stages where it is required to do so. However, this co-operation is limited to the product produced, the actions taken and the criteria used.

Because of this context, various areas or actors contribute to investigating possible administrative breaches and thereby ensuring disciplinary liability (Figure 5.2). However, besides the guidance illustrated in Box 5.5 there are no mechanisms or tools for the exchange of information to build disciplinary cases and, according to the information collected during the fact-finding mission, this has been even more challenging during the COVID-19 situation. Similarly, in the absence of a formal coordination mechanism, the administrative authority consults with the judicial authority on an ad hoc basis, when exchange of information or further coordination is required.

Figure 5.2. Interactions of various actors in the investigation of administrative breaches

Source: Developed by OECD.

Formally established legal and operational rules and conditions for sharing relevant information and ensuring co-ordination among entities involved can ensure swift access to critical information for the initiation or evidential support of proceedings. According to information collected through the OECD questionnaire developed for the purposes of this review, there is one case of standardised cooperation in the Costa Rican public sector between the Supreme Court of Justice and the Ministries of Public Security and of Public Works and Transport (Circular 17-2004, Agreement 26-2018). The circular and the agreement stipulate that the judicial offices of the country are required to inform the Ministry of Public Security and the Ministry of Public Works and Transport of any complaint of possible abuse of authority from the Traffic Policy. The Circular also includes the required information to be shared (i.e. basic information regarding the cases, alleged offence under investigation and status of the case), thus ensuring a standardised form of communication between the involved stakeholders.