This chapter provides an overview of recent advances and remaining challenges related to public governance in Bulgaria, in particular persisting challenges in the fight against corruption, judiciary and public procurement. It also provides an overview of recent advances and remaining challenges relating to regulatory quality in Bulgaria.

OECD Investment Policy Review: Bulgaria

7. Public governance

Abstract

Introduction

Public governance has a significant influence on the climate for business and investment. Poorly designed or loosely applied regulations can slow business responsiveness, divert resources away from productive investments, hamper or delay entry into markets, reduce job creation, and generally discourage entrepreneurship. From an investor’s perspective, regulatory policy should provide strong guidance and benchmarks for action by officials and set out what investors can expect from the government regarding regulation. From the citizens’ point of view, regulation influences the quality of public services by shaping the behaviour of public and private actors and can influence citizens’ involvement in policy making.

The quality of public services also significantly influences the investment climate as well as the citizens’ life. In this regard, policies ensuring the transparency, predictability, and effectiveness of the regulatory framework for investment are essential to reduce or eliminate potential or existing obstacles faced by companies when they consider investing in a country.

Integrity is also a crucial determinant of a favourable investment climate. Comparative evidence suggests a link between trust in politicians and public officials, both from the business community and citizens, and the perception of corruption. Integrity tools and mechanisms, aimed at preventing corruption and fostering high standards of behaviour, help diffuse concerns by investors when considering investing in a country. Bribery and corruption also undermines the rule of law and the ethical values upon which democratic societies and their institutions are based.

Ever since the accession of Bulgaria to the EU, the country has made progress in improving the regulatory quality of public governance, control of corruption, and government effectiveness. As discussed in this chapter, Bulgaria has improved its anti-corruption framework. Despite the many encouraging steps undertaken by Bulgaria, the country nevertheless still suffers from a negative image with respect to the regulatory quality of public governance and corruption. Corruption continues to be viewed as being widespread, impacting decisions by entrepreneurs to invest in Bulgaria. Tailor-made specifications for particular companies and the unclear selection or evaluation criteria are also believed to be widespread practices in public procurement. Bulgaria’s civil service has also been seen as subject to a high degree of politicisation, a likely consequence of the communist legacy (EC, 2018b). There have also been strong suspicions of favouritism and political connections, especially at the local level, despite some significant steps taken by the government for ensuring the integrity of the country’s administrative system. Concerns have also been expressed regarding legal certainty and the quality of public services, which have been seen as affecting the decisions of entrepreneurs to invest in Bulgaria.1

Challenges persist in the fight against corruption

Corruption control is a basis for sound governance and an attractive investment climate. Effective rule of law is fundamental to a market economy and an inclusive society as it ensures that everyone is treated equally and consistently under well-defined laws. Despite Bulgaria’s progress in addressing corruption over the past 20 years or more, corruption continues to be perceived by investors as an important issue. According to the 2019 EU Flash Eurobarometer on businesses attitudes towards corruption in the EU, 85% of respondents operating in Bulgaria described corruption as widespread; 50% of respondents felt that corruption had increased in the previous years and more than 80% considered that bribery was the easiest way to obtain public services.2 In the Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) for 2020, Bulgaria ranked 69th – the worst ranking of an EU country along with Romania (69th) and Hungary (69th) among 183 countries surveyed. In the Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index for 2021 released in January 2022, Bulgaria ranked 78th among 180 countries surveyed, again the worst ranking of an EU country. Entrepreneurs have regularly considered that corruption was one of the biggest shortcomings when it comes to business conditions in Bulgaria compared to other countries in the region.

The judiciary – in principle the institution of choice for resolving commercial disputes or enforcing contracts- has not been trusted either. Courts have been perceived as corrupt and inefficient. Challenges with respect to Bulgaria’s judicial system have been highlighted in numerous reports by international organisations such as the European Commission and the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe. As a consequence, at the time of Bulgaria’s accession to the European Union in 2007, the country was placed under the EU’s Mechanism for Co‑operation and Verification (CVM) to ensure progress in judicial and anti-corruption reforms.

Combatting corruption requires simultaneous actions in many areas, encompassing both preventive and repressive measures. In this regard, Bulgaria, in line with good practices, has been following a holistic approach, engaging in reforms with a view of strengthening repressive measures and enhancing public integrity. Individual reforms have been part of the priorities in a series of long-term anti-corruption strategies.

For example, in the framework of its anti-corruption strategy covering the period 2015‑20, Bulgaria carried out reform of its legal and institutional anti-corruption framework, leading to a number of high-level investigations in 2020. The reforms also provided for public access to the property and interests declarations of senior public office holders. They also included the adoption of the Anti-Corruption and Forfeiture of Assets Act (AFAA), which introduced key principles relevant to the fight against corruption such as legality, transparency, independence, impartiality, including provisions on greater responsibility of senior public officials; publicity of the property of the persons holding higher public posts; respect and guarantee of citizens’ rights and freedoms. In addition, the AFAA established a single, specialised institutional structure – the Commission for Countering Corruption and Confiscation of Illegally Acquired Property (the Anti-Corruption Commission) – to enforce the law. Since then, the new anti-corruption strategy for the period 2021‑27 has been approved, with a new set of priorities, namely strengthening capacity to combat corruption; increasing accountability of local authorities; and creating an environment against corruption capable of timely responses (European Commission, 2021).3

Because of these actions, reforms undertaken by Bulgaria in the past few years have been assessed by international organisations as contributing positively to the fight against corruption (European Commission, 2020a; European Commission, 2021). Still, Bulgaria faces continuous challenges, for example with respect to the independence of the judiciary as highlighted by the European Parliament’s resolution on the rule of law and fundamental rights adopted in October 2020.4 A lack of tangible results in the fight against corruption has also been one of the key aspects of fuelling protests in 2020 and in the context of the April and July 2021 parliamentary elections. A solid record of accomplishment of final convictions in high-level corruption cases remains to be established. In addition, although a legal framework is in place with respect to conflict of interest, yet concerns exist as regards lobbying.

Prosecution and sanctioning of corruption

The legal framework to fight corruption is largely in place. Significant progress has been achieved as regards the adoption of criminal legislation reforms and the establishment of law enforcement mechanisms specifically dedicated to the detection, prosecution and sanctioning of corruption (European Commission 2020a). Bulgaria’s actions have been guided inter alia by its obligations under relevant Council of Europe and EU instruments, the OECD Convention on Bribery of Foreign Public Officials and the UN Convention Against Corruption. Modern criminal legislation has been established, largely meeting international standards. Bulgaria has also paid attention to strengthen procedural means to make Bulgaria’s law enforcement agencies more efficient to detect and investigate corruption, although these concern primarily domestic corruption and organised crime with bribery of foreign public officials receiving much lower attention as assessed by the OECD Working Group on Bribery in the framework of Bulgaria’s Phase 4 Monitoring Report in October 2021.5 The institutional setting of the law enforcement system has been a particular focus of reforms as illustrated by the establishment of a unified anti-corruption commission under the 2018 AFAA (Box 7.1).

Box 7.1. The Commission for Countering Corruption and Confiscation of Illegally Acquired Property in Bulgaria

The Commission is an independent and specialised public agency entrusted with the implementation of anti-corruption and seizure policies been established by the Law on Anti-Corruption and Confiscation of Illegal Acquisitions (enacted SG No. 7 of 19 January 2018).

The Commission is the successor to the Commission for Confiscation of Illegally Acquired Property, established by the Law on Confiscation in favour of the State of Illegally Acquired Property (promulgated SG, No 38 of 18.03.2012), and the Commission for Establishment of Property Acquired from Criminal Activities, established by the Law on Seizure in favour of the State of Property Acquired from Criminal Activities (promulgated SG, No 19 of 01.03.2005).

For its activities, the Commission is accountable before the National Assembly of the Republic of Bulgaria. Bulgaria’s former Prosecutor General preside the Commission for Illegal Assets Forfeiture (CIAF).

The Commission is empowered to bring forfeiture proceedings for illegally acquired assets when is proved an unlawful acquisition of assets. Such a proceeding can take place if an investigation by the Commission establishes a discrepancy that exceeds BGN 150 000 (approximately EUR 75 000).

The Commission has also to ensure that there is no a conflict of interest among high-ranking officials. Any breaches to the rules on conflict of interest are subject to pecuniary sanctions from the Commission.

Source: The Anti-corruption and Forfeiture of Assets Act; the Commission for combating corruption and confiscation of illegally acquired property website.

Other ways to tackle and deter corruption have involved confiscation of assets, which is being carried out in Bulgaria both permanently and temporarily to recover property derived from corruption. It is widely acknowledged that the confiscation of the proceeds and instrumentalities of a crime constitutes an additional deterrent that may have as great an effect as a fine or prison term; the threat of confiscation is also a preventive measure, as it makes bribes solicitation less attractive to public officials. In this regard, Bulgaria has modern legislation in place, which makes it mandatory to confiscate the proceeds and instrumentalities of crime and largely complies with both the international and European standards concerning the asset recovery process.

Despite these encouraging developments, the lack of results in the fight against corruption has been source of concerns, as illustrated by civil protests in 2020 and Bulgaria’s 2021 parliamentary elections, which were all about corruption.6 While high-level corruption investigations cases increased in 2020, most of them did not have tangible results (European Commission 2020a and 2020b). Concerns have also been expressed with respect to alleged political influence and lack of political independence in the work of the Anti-corruption Commission since its chairperson and members are elected after a simple majority vote in the National Assembly (European Commission, 2020b). For example, in 2020, out of 33 decisions that the Supreme Court of Cassation issued on corruption cases, only two were revived in criminal proceedings (EC, 2021). According to the 2019 Eurobarometer survey on corruption published in June 2020, only 18% of surveyed people trusted the role of the Anti-corruption Commission in addressing cases of corruption – a decrease of 4% compared to previous years. Specific concerns have also been raised regarding the Prosecutor General’s power to influence cases and essential immunity from criminal investigation of himself.

As a result, according to the above mentioned Eurobarometer survey on EU citizens’ attitudes towards corruption, 80% of the Bulgarians interviewed considered corruption to be widespread in their country and 51% considered that corruption had increased in the previous three years. With respect to Bulgaria’s confiscation of assets system, when compared with countries such as Croatia, Moldova and Romania, it has been assessed as less developed than those found in Croatia and Romania (OSCE, 2018).

Judicial reform has advanced but challenges remain

Judicial reform in Bulgaria has advanced. Through the CVM, Bulgaria has undertaken actions to tackle major issues such as concerns about the lack of professionalism and impartiality of the judiciary with the overall objective to enhance the objectivity and transparency of magistrates, including through the election of the new Supreme Judicial Council (SJC), the highest administrative authority in Bulgaria’s judiciary (European Commission, 2017, 2018). For example, a reform adopted in 2015 led to a division of the SJC into two categories of professionals – the prosecutorial college (11 members) and the judicial college (14 members) – to prevent prosecutors and investigators from participating in individual decisions for judges.

Other reforms have aimed at strengthening the role of the anti-corruption agency and of specialised prosecutors as well as the Prosecutor General’s accountability. In 2020, the Constitutional Court clarified that a Prosecutor General cannot exert his supervisory and methodological guidance role in cases against himself. In early 2021, following recommendations by the Venice Commission, a law on accountability of the Prosecutor General, establishing a special prosecutor to investigate crimes committed by the Prosecutor General or his deputy, was adopted.7

As a result of these reforms, the performance of the justice system has been seen as improving. According to the EU Justice Scoreboard for 2018 and 2019, Bulgaria performed rather well with respect to the time needed to resolve civil, commercial and administrative cases, on the number of pending cases, as well as the average length of judicial review cases against decisions of consumer protection. The 2019 EU Justice Scoreboard showed other positive developments such as the fact that Bulgaria had one of the highest numbers of judges per 100 000 inhabitants or that Bulgaria is one of the few EU countries that provide the public with comprehensive online information about the judicial system (European Commission 2019a).

Despite these encouraging policy developments, public perception of judicial independence has improved marginally. In 2018, only 30% of respondents from both public and businesses had a good opinion of the courts and judges in Bulgaria (compared to the EU averages of 56% and 48%, respectively). On the Global Competitiveness Report’s scale, which ranges from one (bad) to seven (best), Bulgaria’s judicial independence score for 2019 was 3.3. According to the 2019 EU Justice Scoreboard, perceptions among citizens and companies about the independence of the judiciary remained among the weakest in the EU, suggesting recurrent concerns about possible interference in the work of judges or pressure from economic and other interests. In 2021, according to 2021 EU Justice Scoreboard, the level of perceived judicial independence in Bulgaria remained low among the general public, having decreased slightly compared to 2020. Only 31% among the general public considered judicial independence to be ‘fairly or very good’. The level of perceived independence among companies remained average, with 43% considering it to be ‘fairly or very good’ (European Commission, 2021). Investors have been reporting that Bulgaria’s justice system not only does not support existing business operations, but also restricts existing opportunities for investment (World Bank, 2019).

Despite the progress made by Bulgaria with reforming the Prosecutor General, the combination of the Prosecutor General’s powers and position has been perceived as exerting influence, as the Prosecutor General may annul or amend any decision taken by any prosecutor which has not been reviewed by a judge (European Commission, 2021). As it has been noted by the Venice Commission and the EC, while the establishment of a separate judicial chamber has reduced the influence of the Prosecutor General on the career and discipline of lower court judges, it has increased the General Prosecutor’s influence on career and disciplinary questions concerning prosecutors and investigating judges and on the appointment or dismissal of heads of prosecutor’s offices (European Commission, 2020b). Similarly, despite progress made with respect to the SJC, its composition and functioning has continued to be subject to concerns by international organisations such as the Council of Europe.8 To safeguard judicial independence and the rule of law, Bulgaria should implement accountability mechanisms for the Prosecutor General and improve the governance of judges (OECD, 2021). In this respect, the absence of judicial review against a decision of a prosecutor not to open an investigation continued to raise concerns in 2021 (European Commission, 2021).

Another matter of concern has been the low confidence in the ability of the justice system to prosecute and implement convictions of those guilty of corruption: in 2017, only 24% of companies thought that corrupt people or businesses would be caught by prosecutors, much lower than the EU‑28 average of 43% (European Commission, 2017). In an October 2019 report, the European Commission noted that more work to detect and convict those engaged in corruption was needed (European Commission, 2019b). Despite significant efforts undertaken by Bulgaria to accelerate courts processes and balance out the uneven workload of judges, notably by amending the civil procedure code to allow cases to be distributed to other courts regardless of jurisdictions, and through amendments to the criminal procedure code, the capacity of the judiciary to deal with corruption and other cases has been an area of concern. As noted earlier in this Review, despite legislative efforts, digitalisation of justice is also still lagging behind in practice.

In summary, Bulgaria still faces institutional deficiencies, especially as far as the independence of the judiciary is concerned. There is scope for further strengthening Bulgaria’s judiciary to stimulate investor confidence and ultimately growth. This includes strengthening the independence of the prosecution system and more broadly the independence of the judiciary; increasing accountability of the justice system; ensuring more intensive training for judges; and further rebalancing the workload among courts. With respect to the latter, Bulgaria adopted in February 2021 a roadmap with an action plan to implement a new reorganisation of the court system (Box 7.2).

Box 7.2. Action plan for a new model of the judicial structures at district and appellate levels

With a decision of 2 February 2021, the Judges’ College of the SJC adopted a Roadmap and an Action Plan for reorganisation of the judicial structures at district and appellate levels, including the opening of territorial divisions at the regional courts.

The new model foresees:

To unite regional courts to reduce the number of cases to be heard in the regional courts.

To divide the staff of the regional courts into permanent and non-permanent staff. The permanent staff of judges will work only in the regional court, and the non-permanent will be part of the staff of the higher district court.

To increase significantly the number of judges in the district and appellate courts. The district courts will hear some of the cases currently triable by the regional courts, while the appellate courts will hear a large part of the appellate proceedings

To introduce a workload rate for judges in regional, district, and appellate courts to better foresee the needs of judges per region.

Source: Bulgaria, Reform of the Judicial Map, 2021.

Preventing undue relations between business and politics

Fair political parties’ funding is crucial not only for preventing the risk of corruption but also for protecting democracy. In 2019, Bulgaria’s parliament removed all limits for individual and corporate donations for political parties,9 a move that has been seen as potentially worsening corruption in Bulgaria. Analysts warned that unlimited donations from companies and private citizens could lead to an unhealthy merging of political and business interests.10

Bulgaria does not regulate lobbying activities either. There are no regulations establishing obligations for registration of lobbyists and no transparency standards and disclosure requirements are set in this field. The lack of specific legislation regulating lobbying in Bulgaria has been assessed as potentially increasing the risk of policy capture (European Commission 2020b). Notwithstanding establishing a solid regulation of lobbying is part of Bulgaria’s national action plan in response to the EC 2020 Rule of Law Report,11 concrete steps have not been taken yet (EC, 2021). In this regard, Bulgaria could make use of the Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying adopted by the OECD in 2010, which are international principles providing guidance on how to meet expectations of transparency in the public decision-making process.

Protecting sources of information

Reporting of wrongdoings can play a role in the detection of violations of anti-corruption legislation and public integrity standards (OECD, 2015). A solid legal whistle‑blower protection can encourage citizens to disclose cases of corruption and illegal conduct. In Bulgaria, there is no generic, freestanding whistle‑blower protection law.

Until now, Bulgaria has been relying on specific provisions built into a number of different statutes: its Administrative Procedure Code (APC), the Labour Law Code, the Law on Civil Servants and the Anti-Corruption and Forfeiture of Assets Act (AFAA). Bulgaria’s legal framework for reporting corruption and protecting whistle‑blowers remains fragmented and does not provides sufficient guarantees and measures to encourage submission of alerts. For example, the provisions of the APC are applicable to the public administration sector only. According to the AFAA, anyone who has information about corruption or conflict of interests may signal it to the anti-corruption commission and such reporting cannot be anonymous: whistle‑blowers are required to disclose their names, address, telephone, fax and electronic address (Article 46 and Article 47, AFAA). Given that anonymous complaints are neither allowed nor protected, the Anti-Corruption Commission cannot thus use the information received from undisclosed sources (European Commission, 2021).

Fear of retaliation has been widely recognised as the main disincentive to report on other’s misconduct. According to the 2019 EC Special Eurobarometer, 39% of Bulgaria’s participants in the survey would not report a case of corruption because of fear of retaliation. Bulgaria’s civil society organisations and the public in general have been particularly critical of the current legal framework, which has been seen as insufficient in providing whistle blowers protection (European Commission 2020b).

Continuing efforts to improve the protection regime for whistle‑blowers will not only benefit Bulgaria’s overall anti-corruption system but also increase pressure on companies to set-up internal compliance programmes, as discussed in Chapter 8. In this respect, it should be noted that, as a result of the 2019 EU Whistleblowing Directive, which entered into force on 16 December 2019, Bulgaria was required to adopt a national whistleblowing legislation no later than December 2021. A Whistleblower Protection draft Act aiming to transpose the European Whistleblower Protection Directive was published on the Council of Ministers' portal for public consultations in April 2022.

Challenges also persist in the area of public procurement

Unfair or opaque procurement processes may send negative signals to businesses and mislead them into considering that corruption is part of the normal course of doing business in a country. In Bulgaria, general government public procurement accounts for approximately 12% of GDP, the same as the OECD average and below the 18‑20% average in the European Union percentage (OECD, 2016). Public procurement has been particularly important for the construction sector in the country, with approximately a third of total sector turnover deriving from public procurement in 2013.12 Given the important share of public procurement in the Bulgarian economy, consolidating the procurement system is important for attracting FDI (OECD, 2017).

Commendable progress has been made in modernizing public procurement in Bulgaria since the launch in 2014 of the National Strategy for the Development of the Public Procurement Sector (2014‑20), which aimed at enhancing the efficiency and lawfulness in the public procurement awards, and the adoption, in 2016, of the Public Procurement Act (PPA). The law transposes the EU directives on public procurement into the Bulgarian legislation and is therefore aligned with EU rules in particular with respect to the principles of equal treatment and non-discrimination; free competition; proportionality; and publicity and transparency (PPA, Article 2).

Since 2016, the Public Procurement Agency, which is an independent body established under the Ministry of Finance, has established itself as the leader regarding the implementation of Bulgaria’s PPA by ensuring a close inter-agency co‑operation for the implementation of common policy in the field of public procurement. In particular, the Agency is responsible for undertaking the following types of external control related to public procurement: control through random selection of public procurement procedures; control on certain negotiated procedures; control on specific modifications to public procurement contracts. Both the National Audit Office in Bulgaria and the Public Internal Financial Control Agency are in charge of the ex-post control by ensuring that procurement procedures comply with the provisions of the PPA. According to the PPA, the Commission on Protection of Competition (CPC) is charged with the public procurement appeal procedure while Supreme Administrative Court acts as a second-instance body.

Notwithstanding this new environment, the proportion of businesses that regard corruption in public procurement as very or fairly widespread in Bulgaria’s public opinion remains high. According to the 2019 Business Eurobarometer survey, 74% of businesses felt that corruption was very common in public procurement. According to another survey, conducted by the German-Bulgarian Industrial-Commercial Chamber in 2019, one of the main challenges for Bulgaria’s economy and business environment was the non-transparency of Bulgaria’s public procurement.13 Anecdotal evidence abounds that powerful private operators would exert pressure on the public administration to channel public procurement to major companies linked through circles of influence to them.

Echoing these concerns, the legislation governing public procurement has been amended on several occasions, with each amendments enhancing transparency and control. Reforms initiated to address irregularities and corruption-related issues have nevertheless been perceived by business as jeopardising legal certainty (European Commission, 2020). For example, the PPA was amended 11 times in 2018.14

Administrative capacity has been another challenge for the procurement system, causing delays (World Bank 2019), despite support provided by the OECD. For example, the OECD, in 2016, provided Bulgaria with technical assistance on setting training priorities and developing training materials for capacity building programmes in the public procurement sector.15 Yet, despite continuous training efforts, the professionalization of public purchasers, particularly at the municipal level, has remained challenging (European Commission, 2019b). E‑government reforms have reportedly progressed slowly and have not led to a significant improvement in the business environment (European Commission, 2020a), despite actions taken by Bulgaria in this regard. In 2020 mandatory use of the centralised e‑Procurement platform (CAIS EPP) was introduced at two stages: as of 1 January 2020 – for central administrative bodies and their territorial structures, the CPB for the needs of central administration, other public bodies established by a law, as well as big municipalities and contracting entities; as of 14 June 2020 – for all other contracting authorities and contracting entities.

There is room for developing expertise of public procurement specialists. The development of a skilled workforce in public procurement meeting high professional standards for integrity and knowledge would improve the public procurement system. Bulgaria should make additional efforts on further enhancing the operational capacity of PPA and countering corruption in public procurement, which could include greater use of e‑procurement tools.

Improving the quality of regulations

As noted in the introduction to this chapter, the quality of public regulation is another important component of a sound investment climate. According to the OECD Policy Framework for Investment, poorly designed or weakly applied regulations can slow business responsiveness, divert resources away from productive investments, hamper entry into markets, reduce job creation and generally discourage entrepreneurship. To reduce the stock of overtly burdensome, conflicting or poor-quality regulations and to address national and global challenges pertaining to systemic risks (e.g. protection of human health, safety or environment), governments need to articulate better regulations and make continuous progress in regulatory reforms. There are a number of tools at policy makers’ disposal to achieve these objectives, including better stakeholder engagement, the use of regulatory impact assessment (RIA) and ex post evaluation of regulations, as captured in the Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance (Box 7.3).

Box 7.3. Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance

The OECD Council adopted the Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance in 2012. The Recommendation was the first international instrument to address regulatory policy, management and governance as a whole‑of-government activity that can and should be addressed by sectoral ministries, regulatory and competition agencies.

The Recommendation sets out the measures that Governments can and should take to support the implementation and advancement of systemic regulatory reform to deliver regulations that meet public policy objectives and will have a positive impact on the economy and society. These measures are integrated in a comprehensive policy cycle in which regulations are designed, assessed and evaluated ex ante and ex post, revised and enforced at all levels of government, supported by appropriate institutions. Many topics such as consultation and citizen engagement, regulatory impact assessment, multi-level coherence, risk and regulation, institutional responsibility for policy coherence and oversight, and the role of regulatory agencies are more developed that in earlier principles.

Together the Recommendation’s principles provide countries with the basis for a comprehensive assessment of the performance of policies, tools and institutions that underpin the use of efficient and effective regulation to achieve social, environmental and economic goals. Through its work programme, the Regulatory Policy Committee supports countries in their implementation. In particular, the OECD Regulatory Policy Reviews assess regulatory management capacities in different countries, including policies, tools and institutions for ensuring regulatory quality, using the Recommendation as an assessment framework.

Source: Source: OECD (2012)

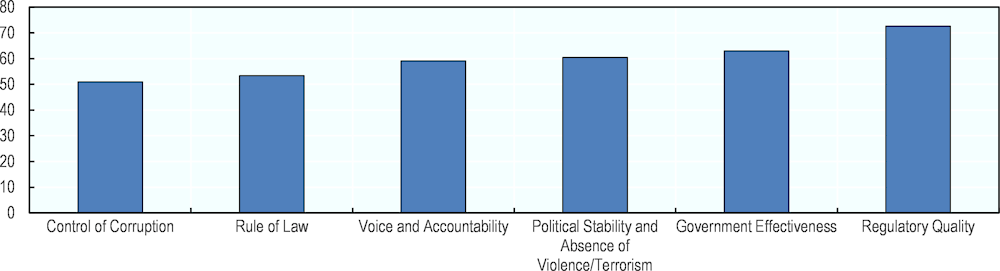

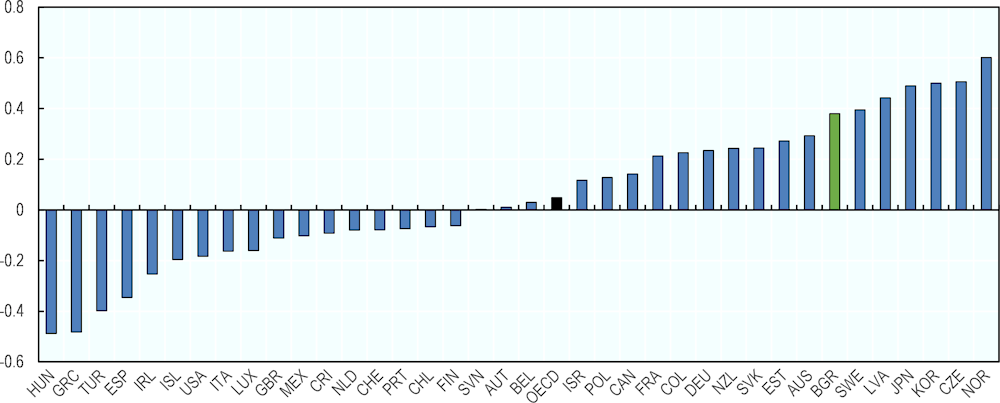

Overall, Bulgaria has made strides in improving the quality of its regulations, including as part of the process of adopting the EU acquis. As such, it scored best on regulatory quality across the different aspects measured by the World Bank’s World Governance Indicators in 2018, available for 155 economies globally (Figure 7.1).16 In addition, it is one of the countries that improved most its capacity in this area between 2000 and 2018, scoring much above the OECD average in this regard (Figure 7.2). While to some extent this captures the low starting point in Bulgaria, it is also indicative of an impressive catching up process, accomplished over the years.

Figure 7.1. Bulgaria’s rank on World Governance Indicators, 2018

Note: The percentile rank is calculated based on a given country’s score and that of 154 other ranked countries.

Source: World Bank’s World Governance Indicators (2018).

Figure 7.2. Change in the quality of regulations in Bulgaria, 2000‑18

Note: The graph shows a change in the country’s score on regulatory quality between 2000 and 2018.

Source: World Bank’s World Governance Indicators (2018).

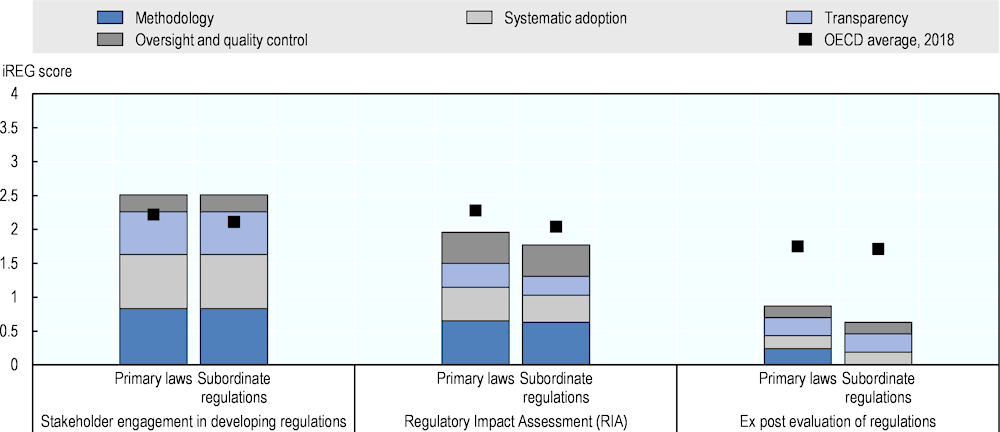

Most recently, Bulgaria has also made legislative changes aiming at improving specific aspects of regulatory quality, as highlighted in the OECD report on quality of regulatory practices across the EU Member States (OECD, 2019) and in the OECD Regulatory Policy Scan of Bulgaria (OECD, 2022). In particular, Bulgaria has significantly reformed its regulatory management system as a result of the entry into force of the Law on Normative Acts in 2016. The law extended minimum consultation periods with stakeholders to 30 calendar days,17 and resulted in the establishment of a central consultation portal, which is now better integrated with Bulgarian impact assessments for regulatory proposals (OECD, 2019). Before being adopted, a draft regulation needs to be made available both at the main internet page of the initiating institution and via the central consultation portal (www.strategy.bg) where stakeholders can also provide their comments.18 The portal also provides direct feedback to participants that explains how their submission has helped shape final regulatory proposals. As a result of these changes, in 2018, Bulgaria scored above average on stakeholder engagement in developing regulations on OECD Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance (iREG) (Figure 7.3). Still, relative to the EU average, it needs to strengthen the oversight function and transparency of the stakeholder engagement process. To this end, “Standards for Holding Public Consultations” were adopted by the Council for Administrative Reform in 2019.

The law also introduced a new RIA system, whereby regulatory proposals are now subject to either a partial or full assessment requirement. Bulgaria established an oversight body for RIA quality control at the end of 2016 (see Box 7.3 for an overview of the institutional set-up for regulatory oversight in Bulgaria). The methodological framework applicable to the executive branch was developed: a Guidance for Ex Ante Impact Assessment and a Guidance for Ex Post Impact Assessment were adopted by the Council of Ministers in 2019 and 2020, respectively. Annual Reports on the RIA are adopted by the Council for Administrative Reform, identifying the progress, but also the weaknesses and challenges. Still, mainly due to the need to further systematise the use of RIA at parliamentary level as well as increase its transparency, Bulgaria is scoring slightly below the OECD average in this area.19 As part of its RIA, Bulgaria has also started introducing an SME Test to assess the effects of proposed regulations on SMEs, and developed a business guide for SMEs (see Chapter 6). In addition, it is worth noting that the same RIA and consultation requirements apply to the transposition of EU regulations in Bulgaria as domestic regulations although Bulgaria does not routinely undertake consultations or impact assessment at the development or negotiation stage but only once the regulations is being transposed into domestic law (Table 7.1).

Box 7.4. Institutional setup for regulatory oversight

The Council of Ministers is responsible for promoting overall regulatory policy in Bulgaria, including in relation to stakeholder engagement, RIA, and ex post evaluation. An oversight body in the Administrative Modernisation Directorate of the Council of Ministers in Bulgaria is responsible for quality control of regulatory management tools. No evaluations have yet been conducted in Bulgaria to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of any of its regulatory management tools.

The Council for Administrative Reform, established under Decree 192 of 5 August 2009, acts as an advisory body to the Council of Ministers for the co‑ordination of regulatory burden reduction on both business and citizens.

Source: OECD (2019).

Figure 7.3. Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance (iREG): Bulgaria, 2018

Note: The more regulatory practices as advocated in the OECD Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance a country has implemented, the higher its iREG score. The indicators on stakeholder engagement and RIA for primary laws only cover those initiated by the executive (42% of all primary laws in Bulgaria).

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Survey and its extension to all EU Member states; see OECD (2019).

Finally, yet importantly, since the entry into force of the law, all new laws, codes and sub-statutory acts of the Council of Ministers are subject to ex post evaluation within five years of their entry into force. Still, even though ex post evaluations are conducted in Bulgaria, they are limited in number and in scope, primarily focusing on administrative burdens for business. Assessing a wider range of impacts would help to ensure that regulations remain appropriate over time. This is an area where Bulgaria lags most behind both the EU and OECD averages according to iREG indicators and could make further progress. The expiry in 2021 of the five‑year period for holding ex post evaluations and the adoption of a comprehensive methodological document (Guidance for Ex Post Impact Assessment) is expected to provide a favourable base for improvement. As discussed in Chapter 6, advances in reviewing, streamlining and improving the stock of existing regulations can help reduce administrative burdens with positive effects on business climate. Yet, the experience thus far has been mixed, including in regards to meeting specific quantitative reduction target, and remains an ongoing challenge.

Table 7.1. Requirements to use regulatory management tools for EU-made laws: Bulgaria

|

Stakeholder engagement |

Regulatory impact assessment |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Development stage |

|||

|

The government facilitates the engagement of domestic stakeholders in the European Commission’s consultation process |

No |

|

|

|

Negotiation stage |

|||

|

Stakeholder engagement is required to define the negotiating position for EU directives/regulations |

No |

RIA is required to define the negotiating position for EU directives/regulations |

Yes |

|

Consultation is required to be open to the general public |

NA |

|

|

|

Transposition stage |

|||

|

Stakeholder engagement is required when transposing EU directives |

Yes |

RIA is required when transposing EU directives |

Yes |

|

The same requirements and processes apply as for domestically made laws |

Yes |

The same requirements and processes for RIA apply as for domestically made laws |

Yes |

|

Consultation is required to be open to the general public |

Yes |

RIA includes a specific assessment of provisions added at the national level beyond those in the EU directives |

No |

|

|

|

RIA distinguishes between impacts stemming from EU requirements and additional national implementation measures |

NA |

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Survey and its extension to all EU Member states, http://oe.cd/ireg, see OECD (2019).

Despite these improvements, at times significant changes to applicable rules and regulations may nevertheless take place in the parliament without an obligation of prior consultation or impact assessment. For example, the National Centre for Parliamentary Research (NAPR) has shown in a recent analysis, covering the period April 2017‑December 2019, that 37% of the adopted normative acts amend other legal acts (NAPR, 2019). Such amendments are currently not subject to the requirement of conducting public consultation nor a RIA. In addition, public consultation and RIA are required only for the first reading of the proposed regulation in the National Assembly. Changes can potentially be introduced by legislators and voted on without the necessity to consult stakeholders (although amendments that contradict the principles or the scope of the proposed regulation should a priori not be discussed).20

As signalled in recent reports of the European Commission, Bulgaria continues introducing legislative amendments through amendments to other acts via transitional provisions and adopting important amendments between the first and second reading in the National Assembly without public consultation which affects not only the quality of regulation but also the rule of law (EC 2020 and 2021 Rule of Law report). To help ensure alignment with the available international best practices and further improve the quality of its regulations, Bulgaria should also implement any recommendations identified as part of the OECD Regulatory Policy Scan of Bulgaria (OECD, 2022).

Outlook and policy recommendations

An assessment of Bulgaria’s public governance leads to a number of general conclusions. Bulgaria has made perceptible progress by strengthening its anti-corruption institutional framework: over the past decade, Bulgaria has consolidated its legal and institutional framework concerning judicial reform and the fight against corruption. In spite of these reforms, businesses’ trust in the government’s ability to combat against corruption remains low. Bulgaria continues to face challenges, for example with respect to the independence of the judiciary and the lack of results in the fight against corruption – which led to protests in 2020 and a surge of votes for anti-corruption parties at the time of the parliamentary elections in 2021. A solid record of accomplishment of final convictions in high-level corruption cases remains to be established.

In addition, although Bulgaria has taken steps to improve its legal framework with respect to conflict of interest (a verification system for asset declaration and conflict of interest is in place), there is limited evidence as to the effectiveness of these measures as highlighted in the July 2021 European Commission Rule of Law Report (European Commission 2021). Concerns also exist as regards lobbying. Bulgaria should make concrete efforts to improve the political funding system, notably by imposing limitations on donations and subjecting political parties to the disclosure of financial resources and auditing.

Public procurement in the country has been modernised with the gradual introduction of the eProcurement platform and regular amendments to the legislation governing public procurement, with each version enhancing transparency and control but this has also affected legal certainty, an issue that the country should address. Given that the public procurement system in Bulgaria suffers from low trust by businesses and citizens alike, the country could make use of the OECD Principles for Integrity in Public Procurement while undertaking additional reforms.

Bulgaria has also made strides in improving the overall quality of its regulatory system. For example, recent legislative changes improved the legal framework for publishing draft laws, conducting public consultations, and preparing regulatory impact evaluations and improved the regulatory oversight. Still, in the area of conducting ex post evaluations of regulations, Bulgaria can achieve further progress to reach the levels found in other OECD countries. In particular, reducing administrative burdens and mixed feedback in reaching quantitative reduction targets point that this area is an ongoing challenge and will require further effort to review and, wherever possible, streamline most burdensome regulations.

Policy recommendations

Build on the progress made in improving the overall quality of regulations by systematising and improving the oversight and transparency of regulatory processes. In particular, ensure that the requirements of prior publication, public consultations and ex ante regulatory impact assessment of draft regulations are respected in practice at the parliamentary level. Also, advance on conducting ex post evaluations to reduce administrative burdens and implement any specific recommendations identified as part of the 2022 OECD Regulatory Policy Scan of Bulgaria.

Continue ongoing reforms to combat corruption, notably by perfecting Bulgaria’s public integrity framework. Significant challenges remain concerning the effectiveness of measures related to the integrity of public administration, lobbying and whistleblowing protection. With respect to the latter, develop an adequate framework for the protection of whistle‑blowers in compliance with the 2019 EU Whistleblowing Directive, which requires EU Member States to adopt a national whistleblowing legislation no later than December 2021 and launch a campaign to enhance officials and the public’s acceptance of whistleblowing.

Continue judicial reforms to strengthen judicial independence and increase public confidence; implement an effective and transparency accountability mechanism for the Prosecutor General in line with international standards.

References

Centre for study of democracy (2016), Управление на обществените общества България: корупционни риски и криминална прокуратура [Public procurement governance in Bulgaria-corruption risk and criminal prosecution], Sofia, https://csd.bg/bg/publications/publication/governance-of-the-bulgarian-public-procurement-sector-corruption-risks-and-criminal-prosecution/

European Commission (2021), 2021 Rule of Law Report: Country chapter on the rule of law situation in Bulgaria, SWD (2021) 703 final, Brussels 20 July 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/2021_rolr_country_chapter_bulgaria_en.pdf

European Commission (2020a), Country report Bulgaria 2020,

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1584543810241&uri=CELEX%3A52020SC0501

European Commission (2020b), 2020 Rule of Law Report Country chapter on the rule of law situation in Bulgaria, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/bg_rol_country_chapter.pdf.

European Commission (2019a), The 2019 Justice Scoreboard, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/justice_scoreboard_2 019_en.pdf

European Commission (2019b), Report from the European Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: On Progress in Bulgaria under the Co‑operation and Verification Mechanism, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/progress-report-bulgaria‑2019‑com‑2019‑498_en.pdf.

European Commission (2018a), Report from the European Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: On Progress in Bulgaria under the Co‑operation and Verification Mechanism,

https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/progress-report-bulgaria-com‑2018‑850_en.pdf.

European Commission (2018b), Public administration characteristics and performance in EU28: Bulgaria, http://ec.europa.eu/social/BlobServlet?docId=19942&langId=en.

European Commission (2017a), Report from the European Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: On Progress in Bulgaria under the Co‑operation and Verification Mechanism, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/comm‑2017‑750_en_0.pdf.

European Commission (2017b), Businesses’ attitudes towards corruption in the EU, Flash Eurobarometer 457, December 2017

NAPR (2019), Study of the legislative activity of the 44 National Assembly, www.strategy.bg/Publications/View.aspx?lang=bg-BG&categoryId=&Id=301&y=&m=&d=&fbclid=IwAR1P1CLY2H02ODkYQBM23622hA9qkXmSCDXDkEvLaiHqLLcVQgv3h233CIQ

OECD (2022), Regulatory Policy Scan of Bulgaria, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.bia-bg.com/uploads/files/analysis/OECD-Regulatory-Scan-of-Bulgaria.pdf

OECD (2021), OECD Economic Surveys: Bulgaria, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/19990626

OECD (2020) OECD Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance (iREG), www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/indicators-regulatory-policy-and-governance.htm.

OECD (2019), Better Regulation Practices across the European Union, OECD Publishing, Paris, www.doi.org/10.1787/9789264311732‑en.

OECD (2018), Anti-Corruption and Integrity Guidelines for State‑Owned Enterprises, OECD Publishing, www.oecd.org/fr/gouvernementdentreprise/anti-corruption-integrity-guidelines-for-soes.htm

OECD (2017), General guide on the public procurement legislative environment in Bulgaria,

OECD Publishing, www.oecd.org/governance/procurement/toolbox/search/guide‑public-procurement-legislation-bulgaria.pdf.

OECD (2016), Public Procurement Training for Bulgaria: Needs and Priorities, OECD Publishing, www.oecd.org/governance/procurement/toolbox/search/public-procurement-training-bulgaria_EN.pdf.

OECD (2015), Policy Framework for Investment- 2015 Edition, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264208667-en.

OECD (2013), Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying: 10 Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying, www.oecd.org/corruption/ethics/Lobbying-Brochure.pdf.

OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://oe.cd/374.

OSCE (2019), Opinion on the Act on Amendment of the Act on the 2019 State Budget of the Republic of Bulgaria, 3 December 2019, www.osce.org/odihr/441685

OSCE (2018), Asset Recovery: A Comparative Analysis of Legislation and Practice – Bulgaria, Croatia, Moldova and Romania, www.rai-see.org//wp-content/uploads/2018June 20180611-AssetRecovery_OSCE_final.pdf

State Agency for National Security (2020), National Risk Assessment of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing, published on 9 January 2020, www.dans.bg/en/msip-091209-menu-en/results-from-national-risk-assessment.

Transparency International (2004), Tools to Support Transparency in Local Governance, https://images.transparencycdn.org/images/2004_TI_UNHabitat_LocalGovernanceToolkit_EN.pdf.

World Bank (2019a), Understanding Barriers to doing Business – Survey Results of how Justice System impacts the Business Climate in SEE,

World Bank (2019b), Оценка на системата за обществени поръчки в Република България [Evaluation of the public procurement system in the Republic of Bulgaria], www2.aop.bg/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Bulgaria-RAS-Procurement-Report-Component‑3‑BG.pdf.

Notes

← 1. See “Foreign Investment has collapsed say Bulgarian industrialists”, BalkanInsight, 28 August 2018.

← 2. See Special Eurobarometer 502, Corruption, December 2019, https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm/Survey/getSurveyDetail/instruments/SPECIAL/yearFrom/1974/yearTo/2020/surveyKy/2247.

← 3. In the framework of this new stratwegy, new priorities have been established as regards high-risk sectors, including strengthening capacity to combat corruption; increasing accountability of local authorities; and strengthening the ability of insitutions to provide timely responses to alledged cases of corruption.

← 4. European Parliament resolution on the rule of law and fundamental rights in Bulgaria, 2 October 2020, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/B-9-2020-0309_EN.html.

← 7. See Law supplementing the Code of Criminal Procedure, https://parliament.bg/bg/laws/ID/163448.

← 8. GRECO Fourth evaluation round – Second compliance report, recommendation V, paras. 13‑15; CCJE Bureau, 2019 edition of the Report on judicial independence and impartiality in the Council of Europe member States.

← 10. See “Bulgaria slashes state subsidy, allows unlimited donations for political parties”, Euractiv, 5 September 2019, www.euractiv.com/section/elections/news/bulgaria-slashes-state-subsidy-allows-unlimited-donations-for-political-parties/

← 11. In November 2020, Bulgaria adopted a “Plan for the implementation of measures in response to the recommendations and the identified challenges in the European Commission’s Rule of Law Report” (Action Plan), covering issues related justice system, anti-corruption framework, media pluralism, and media freedom, other institutional issues related to checks and balances.

← 12. Based on data in the Public Procurement Register, the total value of awarded public procurement contracts for works as a result of public procurement procedure is, as follows:

2017 – 2, 591, 723 563 BGN (VAT excluded).

2018 – 2, 937, 885 708 BGN (VAT excluded).

2019 – 8, 831, 743 878 BGN (VAT excluded).

2020 – 2, 650, 237 291 BGN (VAT excluded)

← 14. Council of Ministers Administration (2019), Impact Assessment Annual Report 2018.

← 15. Under the project “Support for the Design and Implementation of the Bulgarian Public Procurement Training and Development Programme in the Frame of ESIF Ex-ante Conditionality Action Plan”.

← 16. See Kaufmann, Kraay and Mastruzzi (2010) for the methodology.

← 17. In exceptional cases, the project developer may set another time limit, but not less than 14 days.

← 18. There are no restrictions for participating in the public consultation (a registration in the portal is required).

← 19. It is worth noting that the OECD indicators on stakeholder engagement and RIA for primary laws cover processes carried out by the executive, which initiates approximately 42% of primary laws in Bulgaria. While there are requirements to conduct RIA to inform the development of primary laws initiated by parliament, they are relatively less stringent than those for laws made by the executive.

← 20. According to Art 43(3) of the Rules of Procedure for the Organisation and Activity of the National Assembly “On the proposals submitted by Members of Parliament for a second vote, the chairman of the leading commission may request an opinion from non-governmental organizations.” According to Art 84(2) of the Rules of Procedure for the Organisation and Activity of the National Assembly: “During the second voting shall be discussed only proposals of Members of Parliament, received by the order of art. 83, as well as proposals of the committee responsible, included in its report. Editorial corrections are also allowed. Proposals that contradict the principles and scope of the bill passed at the first vote are not discussed and voted on”.