This chapter focuses on the main mechanisms implemented to tackle inefficiencies in justice services in Peru and compares it with OECD Member countries. It describes how countries have increasingly adapted new management, budgetary and digital tools to deal with trial length and case backlog, including case and court management, and how digitalisation and alternative dispute resolution mechanisms are being implemented to increase justice efficiency.

OECD Justice Review of Peru

5. Towards an efficient and seamless justice system in Peru

Abstract

5.1. Introduction

The efficiency of justice services is vital to upholding the rule of law and ensuring fair outcomes, guaranteeing timely and effective access to justice for all. Excessive judicial turnover or temporality in judicial employment (see Chapter 4) impedes justice efficiency. The time a court requires to analyse, process, and adjudicate a case serves as a key indicator of justice efficiency and represents an essential element underpinning the right to a fair trial. This right is safeguarded as a fundamental right in OECD Member country constitutions. Moreover, well-functioning judicial systems are crucial in shaping national economic performance. Lengthy civil proceedings can act as a hindrance to economic activity. The protection of property rights and enforcement of contracts encourage savings and investment while promoting the establishment of economic relationships. These factors contribute positively to competition, innovation, the development of financial markets, and economic growth, as seen in Chapter 2.

This chapter analyses how courts need to organise their resources (human, financial, physical premises, working procedures and management tools) to efficiently address citizen demands for fair and impartial justice. The proper allocation of judges and justice personnel is a key resource supporting smooth justice delivery, though it is not the sole factor. This chapter analyses several tools and mechanisms aimed at addressing inefficiencies in justice services. One approach involves redesigning judicial decision-making processes, while another entails further developing alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms for seeking settlements outside the courts. In some cases, well-defined ADR mechanisms can achieve more equitable, cost-efficient and faster case resolution, as discussed in Chapter 4.

Whether within or outside courts, enhancing the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in the justice system can improve efficiency by reducing case backlog and trial length. Technology can also serve as a powerful enabler of integrated, inclusive and people-centred justice ecosystems through process automation and data collection, creating new justice pathways and providing direct access to services. In fact, ICT is increasingly perceived as a vital tool for breaking physical access barriers to justice.

This chapter will explore how the effective use of justice resources and ICT tools can improve access to justice in Peru. It builds on comparisons with OECD best practices, as well as on the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) general principles and Guidelines to Increase Justice Efficiency and Quality, the OECD Recommendation on Access to Justice and People-Centred Justice Systems [OECD/LEGAL/0498] and the OECD Framework for People-Centred Justice for establishing and maintaining evidence-based mechanisms to support decision making, delivery and monitoring of people-centred justice services (CEPEJ, 2023[1]; OECD, 2021[2]).

5.2. Enhancing court efficiency: Decongestion measures, court and case management and the use of digital solutions

Court efficiency is critical for the seamless functioning of the justice system. It is influenced by several factors, including case backlog management, the adoption of digital solutions, and court and case management practices. This section highlights OECD Member country practices and the situation in Peru in these areas, identifying areas for improvement in ensuring the efficiency of court procedures.

5.2.1. Enhancing court efficiency in OECD Member countries

Case backlogs and decongestion measures

Case backlogs refer to pending court cases that remain unresolved within a legally established timeframe. This situation leads to substantial delays in solving court cases, increasing the cost of legal proceedings, contributing to legal uncertainty, and adversely impacting justice efficiency and people’s trust in the judicial system (commonly expressed as “justice delayed is justice denied”). The following factors typically contribute to these delays:

1. the structure of trial procedures and unnecessary procedural formalisms, leading to inefficient judicial decision making;

2. inefficiencies in the allocation of court resources, often resulting in fewer human resources and malfunctioning or obsolete ICT equipment; and

3. poorly designed performance appraisal schemes for judges, or the absence of incentives for high performance within the judiciary.

To reduce case accumulation in courts, some OECD Member countries have developed new management structures and tools to enhance the administration and delivery of justice in ordinary courts. For example:

Some OECD Member countries rely on temporary staff in periods of high demand, such as decongestion judges in Colombia and temporary replacement judges in Spain (Box 5.1).

Some countries have created special units or chambers within courts to help them reduce case backlogs, such as the United Kingdom, some EU countries, including the Netherlands, Canada, and the United States (Box 5.1). Meanwhile, countries like Austria have implemented early countermeasures initiated by the courts to reduce or avoid backlogs and expedite judicial proceedings (CEPEJ, 2020[3]).

Box 5.1. OECD practices in court decongestion strategies

In Colombia, courts facing longstanding congestion problems prompted the establishment of temporary specialised courts to address the backlog. Known as decongestion courts or fast-track courts, these include additional judges assigned temporarily to handle cases in the regular court system. Colombia has also created specialised Judicial Services Centres (Centros de Servicios Judiciales) in major cities such as Bogotá, Medellín, Cali and Barranquilla. These centres aim to expedite the resolution of oral procedure cases, particularly in family and civil law. These centres efficiently prioritise long-pending or highly important cases by streamlining procedures and providing additional human resources.

In the Netherlands, a central backlog team have been created in the courts, known as the “flying brigade”, a special task force helping courts reduce the backlog in civil and municipal divisions. Once cases are received, judges and court staff within the chamber prepare draft decisions that are then sent back to courts, providing the latter with more time and resources to hear pending cases or dispose of those with pending decisions. In addition, courts can assign cases to other, less busy courts.

Croatia has introduced specialised family departments in 15 municipal courts to strengthen the efficiency and quality of processing these sensitive cases. Judges assigned to these departments meet specific professional requirements. The President of the Supreme Court appoints them for a term of five years at the proposal of the president of the competent municipal court. Additionally, these departments are staffed with psychologists, sociologists and other domain experts. Regular mandatory trainings have been designed for judges and state attorneys.

As seen in Chapter 4, some OECD Member countries have also developed case and court management strategies to optimise court performance and reduce case backlogs. For instance, performance evaluation can play a key role in enhancing court efficiency. Judges’ behaviours are determined by incentives such as career prospects and salary, among other factors, to reduce trial length and increase overall court efficiency.

Reducing trial length

Trial lengths are defined as the time needed to resolve a case in court, representing the duration it takes for the court to reach a decision at the first instance. Across OECD Member countries, factors associated with shorter trial lengths include:

court governance systems that either allocate broader managerial responsibilities to the chief judge or allow the hire of non-judge court managers

existence of specialised courts (such as administrative, commercial or family courts)

active management of case processing by courts through standardisation or other means

systematic production of statistics at the court level

implementation of timeframes, proven to be a useful tool for assessing court functioning and policies and subsequently improving the pace of litigation.

Timeframes serve as operational tools, offering concrete targets to measure the extent to which each court, and the administration of justice, pursue the timeliness of case processing and the principle of fair trial within a reasonable time. Setting timeframes is a fundamental step in measuring and comparing case processing performance and better conceptualising backlog, which is the number or percentage of pending cases not treated within the set or planned timeframe. According to OECD Member practices, each timeframe considers the case complexity, as suggested by the jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights (CEPEJ, 2016[7]).

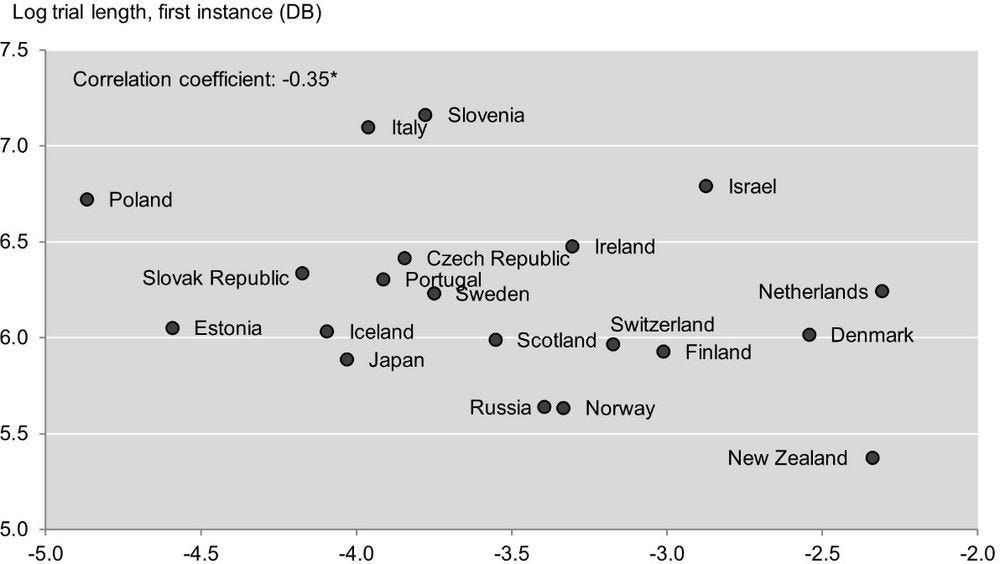

OECD Member countries have increasingly incorporated ICT tools and strategies to support judicial activity in accelerating and improving court performance and case-treatment fairness. Indeed, countries devoting a larger share of the budget to ICT investment display, on average, shorter trial lengths (Figure 5.1) (OECD, 2013[8]) (Palumbo, 2013[9]).They have achieved this by digitalising legal procedures (within the judiciary and in their interaction with users) and increasing the use of statistics by adopting a data-based approach to case monitoring. This approach allows for better prediction of case outcomes, reduces sentencing disparity, facilitates the monitoring of case progression and helps accelerate precedent analysis, as will be analysed in this chapter.

To reduce case length and court backlogs, most OECD Member countries have dematerialised their files through electronic case management or e-filing. While practices may vary, several OECD Member countries have implemented electronic filing systems to streamline judicial processes. In the United States, federal courts use the Case Management/Electronic Case Files (CM/ECF) system, allowing attorneys to file and retrieve court documents electronically. Many state courts have their own e-filing systems, including the New York State Unified Court Systems NYSCEF (US Courts, 2023[10]). Similarly, in Canada, several provinces, including Ontario’s Small Claims Court, have adopted electronic filing systems, using portals for e-filing and claim submissions (OECD, 2023[4]).

In 2021, the Council of Europe’s Working Group on e-Justice and Artificial Intelligence of its Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ-GT-CYBERJUST) developed guidelines on electronic court filing (e‑filing) and digitalisation of courts, including a checklist for countries to reflect on the basic requirements for deploying an e-filing system. Some of the most important CEPEJ guidelines related to implementing digital solutions in the judiciary should be understood as a systemic and comprehensive reform that goes well beyond the technological, e-filing and digitalisation of judicial procedures. These are ongoing processes within a complete service ecosystem, whether digital or not, rather than standalone projects with fixed implementation timelines. These guidelines are also based on the understanding that an e-filing system should uphold the principles of transparency, inclusiveness, accountability and accessibility (CEPEJ, 2021[11]).

Figure 5.1. The ICT share of the justice budget is inversely related to trial length

Source: (CEPEJ, 2022[5]), European Judicial Systems - CEPEJ Evaluation Report: 2022 Evaluation Cycle (2020 data).

However, a significant level of ICT development and diffusion does not necessarily translate into their practical application in the justice system, let alone a positive impact on the efficiency or quality of the public service of justice. It is indeed easier to quantify investments in technology and the degree of its dissemination than to measure ICT's actual use or impact on the efficiency and quality of justice, as these changes are more challenging to measure (CEPEJ, 2022[5]).

Effective court management and resource allocation are also crucial to ensuring shorter trial lengths and reducing case backlogs. Investing in the right areas can significantly increase courts’ efficiency. The efficient use of statistics and data-based approaches to case management and monitoring, when accompanied by the right ICT tools, infrastructure and training, is critical to clearing backlogs, improving court clearance rates and case disposition times, and enhancing the quality of justice delivery, as will be analysed in detail in the next section.

Measuring court efficiency: Clearance rates and disposition times

European OECD Member countries measure court efficiency as a function of case backlogs and trial length by measuring a court clearance rate and a case disposition time, as follows:

The clearance rate (CR) is the ratio obtained by dividing the number of resolved cases by the number of incoming cases in each period, expressed as a percentage. This rate shows how the court, or the judicial system, copes with the inflow of cases and allows comparison between systems regardless of their differences and particularities. When the result is lower than 100%, case backlog is increasing, and the court can resolve fewer cases than it receives. On the contrary, when the result is higher than 100%, case backlog is decreasing, and the court can resolve more cases than it received. In 2020, the median value of the clearance rate of European jurisdictions was stable and close to 100%, with only minor differences among instances and case types, implying that European jurisdictions have efficient case management systems with little, if any, case backlogs.

The disposition time (DT) is the theoretical time necessary for a pending case to be resolved, taking into consideration the current pace of work. This indicator offers valuable information on the estimated length of proceedings. It is reached by dividing the number of pending cases at the end of a particular period by the number of resolved cases within that period, multiplied by 365 (days in one year). More pending than resolved cases will lead to a disposition time higher than 365 days and vice versa.

Some 42 European states provided data to the CEPEJ for calculating the CR and the DT in 2020. These states’ CR ranges from 95% to 200%, and DT is not higher than twice the median value, which comes to 298 days. Most of them have a CR slightly over or under 100% (Andorra, Czechia, Estonia, Kazakhstan, Monaco, Romania and the Slovak Republic). DTs differ to a greater extent, from 10 days in Kazakhstan and 30 days in Estonia to 265 days in Andorra.

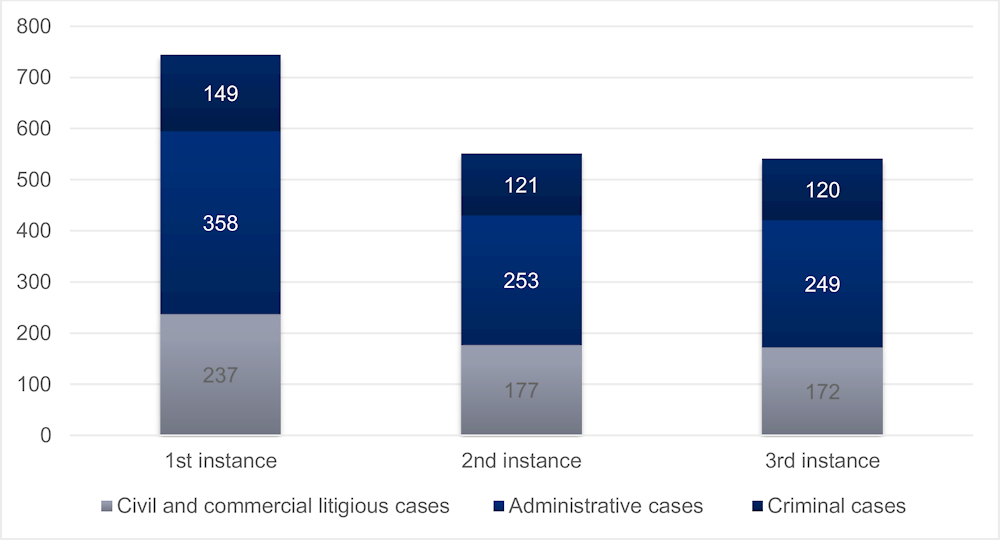

Regarding the DT for EU countries in 2020, the third (highest) instance courts took the lead (with 120 days for criminal cases, 249 for administrative cases and 172 for civil and commercial litigious cases). However, the differences between the second and the third instances are minor. At the same time, the only instance and case type that shows a reduction in DT is the civil and commercial litigious cases at the third instance. Nevertheless, in this cycle, the trends are very much shaped by the effects of the coronavirus (COVID‑19) pandemic, which most affected the productivity of the first-instance courts (Figure 5.2) (CEPEJ, 2022[5]).

Figure 5.2. European median disposition time by instance and by area of law, 2020

Source: CEPEJ (2022), European Judicial Systems - CEPEJ Evaluation Report: 2022 Evaluation Cycle (2020 data).

Court and case management

Effective court and case management ensures the efficiency and transparency of the judicial system, enables effective access to justice, and upholds the right to a fair trial. It involves the availability of systems, sufficient staff, and members of the judiciary to process cases, as well as measuring their efficiency and effectiveness. A responsive justice system ensures that the right mix of services is provided to the right users, areas of law, locations, and time (OECD, 2019[12]). Specifically:

Court management refers to the administration and organisation of the court system, including managing court resources, co-ordinating court processes, and providing support services to the judiciary and the public. The scope of action and main objective are similar in all OECD Member countries (i.e. human resources, technologies, premises, communication, targets and indicators). In most cases, court management involves balancing between achieving the necessary efficiency of the process and accountability while preserving the independence of the justice system. To facilitate this task, some countries, including Denmark, Finland, Norway, Portugal and Sweden, have created permanent dialogue capacity between judges, managers, the Ministry of Justice and court users (OECD, 2020[13]).

Case management, in turn, focuses on administering processes related to processing cases and bringing them to timely adjudication (Rooze, 2010[14]). It refers to the process of managing and overseeing legal cases to ensure their efficient and effective progression through the legal system. It involves organising and co-ordinating various aspects of the case, including procedural matters, deadlines, evidence disclosure and court appearances.

Due to the exponential increase of caseloads coupled with budgetary constraints, there has been increasing attention paid to court and case management practices in OECD Member countries. To respond to this challenge, OECD Member countries’ courts are developing a broad view of case management necessary to achieve timely, cost-effective and procedurally fair justice (Hannaford-Agor, 2021[15]). This has been done by implementing triage, a form of process management that fast-tracks incoming workflow by focusing on the most critical work first, removing unnecessary procedural barriers that complicate litigation, and better staffing court personnel and increasing technology resources, including data and performance management.

A common and effective tool developed in different forms across European and OECD Member countries to improve court performance is case weighting analysis (CWA) (Box 5.2). It was initially designed to identify the needs of judges by assessing the complexity of different case types based on the understanding that one case type differs from the other in the amount of judicial time and effort required to be processed.

Box 5.2. Successful case management tools: Case weighting analysis

Case weighting analysis was developed in the United States in the 1970s to help courts estimate their personnel needs, adjust staff distribution and support requests for more human resources. The practice has expanded to other countries in recent years, which, in turn, has broadened its uses. The CWA was developed to address output insufficiencies created by inadequate staffing, caseload distribution, uneven work units and human resources relative to the actual demand for judicial services. Recent applications have also attempted to address other problems, such as how to deal with significant variations in individual judges’ productivity, a tendency of judges to prioritise easier cases over more complex ones, and the impact of both on accumulating backlog.

The CWA innovation is the recognition that not all cases require the same amount of effort from judges and court staff. This implies that allocating or evaluating personnel according only to quantitative input or output numbers is insufficient. The CWA provides a means to define the level of effort invested in handling each case type. Converted to average case weights, the results can be used to determine reasonable caseloads and distribution of staff. A meaningful CWA requires a good case management information system with as many accurate statistics as possible.

Experts who have worked on CWA caution that the technique is not apt to solve other problems beyond case allocation, affecting the judicial system. Aside from allocative efficiency or the improved distribution of personnel relative to caseloads, other problems may include limited access to justice for citizens and businesses, the lack of standardisation of procedures and practices between work units, significant variations in capacity and professionalism among judges and staff, a legacy of bureaucratic and inherently inefficient procedures, political pressures, corruption, etc. In most justice institutions, these issues are more of a concern than allocative efficiency. Nonetheless, if these additional issues do not represent insurmountable obstacles, a review of case-allocative and relative (within-system) technical efficiency may still be worthwhile, if it does not make anyone believe that all else is well or that a CWA can help solve those other, often more compelling, performance challenges.

Source: Hammergren, Harley and Petkova (2017), Case-weighting Analyses as a Tool to Promote Judicial Efficiency: Lessons, Substitutes, and Guidance (English), World Bank, Washington, DC, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/529071513145311747/Case-weighting-analyses-as-a-tool-to-promote-judicial-efficiency-lessons-substitutes-and-guidance.

5.2.2. Enhancing court efficiency in Peru

Case backlog and decongestion measures

With a CR of 91.7% in 2021 and 92.7% in 2022, Peru's judicial workload (carga procesal) is increasing, and the system is struggling to handle it Table 5.1 which in 2023 reached 3 235 606 cases (Lama, 2021[16]) (Poder Judicial, 2023[17]).

Table 5.1. Clearance rates in Peru, 2021 and 2022

|

2021 |

2022 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Incoming cases |

1 771 155 |

1 955 679 |

|

Resolved cases |

1 629 309 |

1 813 070 |

|

Clearance rate |

91.7% |

92.7% |

Source: Poder Judicial (2023), Plan de Descarga en el Poder Judicial 2024-2025, approved through Administrative Resolution No. 0255-2023-CE-PJ, from 3 July 2023, https://www.pj.gob.pe/wps/wcm/connect/417726004c04e019b48db5dd50fa768f/RESOLUCION+ADMINISTRATIVA-000255-2023-CE.pdf?MOD=AJPERES&CACHEID=417726004c04e019b48db5dd50fa768f

Peru’s Council for the Reform of the Justice System identified in the Public Policy for the Reform of the Justice System (2021-2025) four main reasons affecting court congestion in Peru:

1. First, a sometimes misleading assumption that case efficiency can be solved with additional human resources alone. Indeed, as seen in Chapter 4 and Table 5.1, court congestion keeps increasing even though the judiciary has constantly increased the number of judges (Poder Judicial del Perú, 2022[18]).

2. Second, the implementation of excessive court regulations that complexify and lengthen the process and case resolution. Although the judiciary has made significant progress in solving cases under the former Criminal Procedural Code, there are still open cases under the framework of the old Criminal Procedural Code, adding to case backlogs. Moreover, the lack of investment in justice officials’ adequate training has considerably hampered the smooth implementation of the new Criminal Procedural Code, which includes several provisions and reforms to reduce case backlogs and reduce trial length, as detailed in Chapter 2.

3. Third, as seen in Chapter 3, there is a lack of specialised courts to solve specific matters, especially regarding constitutional rights in all parts of the national territory. For example, in constitutional cases, court congestion is mainly due to a lack of constitutional judges and constitutional courts in the country. Another cause is the embryonic development of the administrative justice system in Peru (Chapter 4), which increases the preference of legal actors for constitutional proceedings instead of using administrative jurisdiction. In family cases, there is a high backlog in child support and alimony cases, where only 3% of these cases are solved in the first instance. In criminal cases, a lack of human and physical resources for the implementation of evidence (peritos/peritazgo) is one of the causes of long criminal trials.

4. Fourth, there is a lack of statistical information to help in decision making, such as caseloads and allocation of human resources, as seen in Section 4.2 in Chapter 4.

Overall, Peru faces similar challenges to those experienced by most OECD Member countries dealing with case backlogs caused by unnecessary procedural formalities, inefficiencies in the allocation of court resources (including obsolete ICT equipment), and inadequately designed performance appraisal schemes for judges, with little or no incentives for optimal performance in the judiciary.

To respond to these challenges, Peru has implemented several initiatives and programmes to reduce case backlogs.

As seen in Chapter 2, the new Criminal Procedural Code (Código Procesal Penal, CPP) provides several mechanisms for criminal procedural simplification, such as oral hearing, which accelerates case resolutions. Since 2006, the judiciary has gradually been implementing strategies to solve procedures under the old code, such as discharge plans in criminal judicial offices, to optimise time in the conduct of hearings. In addition, District Commissions have been implemented to monitor the work of courts by implementing better management and productivity measures to reduce case backlogs. Moreover, since the implementation of Results-based Budgeting (Presupuesto por Resultados, PpR) as a public management strategy in 2008 and in the context of the reform of criminal justice with the implementation of the new CPP, the Budgetary Programme 0086: Improving the Justice System Services of the Criminal Justice (Mejora de los Servicios del Sistema de Justicia Penal) was established in 2015. This programme links public budget allocation to specific products (goods and services) and indicators for implementing efficient and effective criminal justice mechanisms and services through the implementation of the new CPP. However, some of the mechanisms for criminal procedure simplification (see Chapter 2 on the new CPP) are still under-implemented by criminal courts in Peru, mainly due to the prevailing culture of willingness to solve conflicts and problems by starting legal cases and formal case resolution (Consejo para la Reforma del Sistema de Justicia, 2021[19]). This multisectoral programme includes the judiciary, the Public Ministry, the Ministry of Interior and the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights (Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos, MINJUSDH).

Moreover, recognising the significant presence of family cases in Peru’s case backlogs, a new budget programme was created in 2022. This programme aims to modernise the operations of judicial offices dealing with family cases by allocating public funds to implement specific results to accelerate the resolution of these cases. Some of these indicators include digitalising judicial processes, standardising judicial proceedings, promoting conciliation, judges training on the topic and on interpersonal communication, monitoring the implementation of actions and goals of the programme, and strengthening and supporting the work of the detrital commissions of the 33 High Courts where the programme is implemented.

Other initiatives on this matter include Corporative Family Modules (Módulos Corporativos de Familia). Created in 2018, these modules propose a new court management arrangement in which the courts' administrative functions are under the responsibility of a specific unit, freeing the judge of such tasks to perform only judicial ones. The judiciary has been implementing these modules nationwide for labour, family, and civil cases.

The increase in caseloads and insufficient tenured judges to handle the cases has led to the widespread use of temporary judges. This practice has become a significant issue in Peru’s justice system and a risk to judges’ impartiality (see Chapter 4). Notwithstanding, Peru has been implementing measures to reduce the number of temporary judges. Since the launch of the National Board of Justice (Junta Nacional de Justicia), it has implemented initiatives to appoint tenured judges and prosecutors to reduce the number of provisional judges, with the appointment in 2022 of 63 tenured judges.1 From June 2022 to June 2023, the share of tenured judges increased while the share of temporary judges diminished (see Chapter 4).

Although decongestion measures undertaken to improve case backlogs, such as those regarding the CPP and those implemented under family cases, might go in the right direction, they are neither comprehensive nor co-ordinated. These efforts should be designed and implemented alongside digitalisation measures and the adoption of tools to improve court efficiency. These measures should also be co-ordinated across case types (i.e. the decongestion measures undertaken under the CPP should be co-ordinated with those implemented in family cases) to have a greater impact on the justice system overall. Also, the impact of these measures should be measured in terms of CR and DT.

Peru could also implement additional measures to reduce trial length, such as setting timelines, improving court governance systems, creating more specialised courts, improving the systematic production of statistics at the court level and devoting larger shares of the justice budget to ICT.

Like many OECD Member countries, Peru has also implemented a series of justice digitalisation tools and reforms to reduce case backlogs and trial lengths, as summarised in Box 5.3.

Box 5.3. Peru’s justice digitalisation tools and reforms to reduce case backlog

Clearance rate (Indicador de carga procesal): The National Commission on Judicial Productivity (Comisión Nacional de Productividad Judicial, CNPJ) was created in 2008 within the judiciary to follow up on court congestion and propose to the Executive Council of the Judiciary actions and measures to tackle this issue. Its main mission is to collect data on the procedural burden in each transitory and permanent court. Based on this, it has established an indicator to measure court congestion, which is obtained by dividing the number of resolved cases by the number of incoming cases in each period, expressed as a percentage (same as the clearance rate). The CNPJ has also calculated each court's minimum and maximum percentage of procedural burden.

Integrated file management system (Sistema Integral de Gestión de Expedientes, SIGE): The integrated file management system is software developed by the Ministry of the Interior of Peru (MINITER) to help administer and monitor internal and external documentation. It helps organisations quickly locate and organise files, as well as effectively manage resources. The system provides an automated data management system that improves workflow and reduces costs by streamlining document-filing processes. The SIGE system helps manage databases and information systems, including documents, records, data, and images. It is also a powerful platform for virtually organising, sharing and tracking information, making it particularly useful for organisations with limited budgets. The system is designed to improve the accuracy and efficiency of document management and ensure record retention over time.

Electronic prosecution file (Carpeta Fiscal electrónica): The Public Ministry has also started to work on a tool including all digitalised prosecutorial procedures within a case, aiming to accelerate the implementation of justice from the first level of the provincial prosecutorial service to the supreme.

Source: (Consejo para la Reforma del Sistema de Justicia, 2021[19]), Política Pública de Reforma del Sistema de Justicia [Public Policy for the Justice System Reform], Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, https://www.gob.pe/institucion/consejo-de-justicia/informes-publicaciones/2021932-politica-publica-de-reforma-del-sistema-de-justicia; Information shared by Peru, August 2022.

The main organisational ICT reform to accelerate case management is the Judicial Electronic File (Expediente Judicial Electrónico, EJE), a digital case management system and the Peruvian equivalent of electronic case or court filing (ECF) or e-filing in OECD Member countries. This service allows users to access and process their cases online, eliminating the need for most on-site appearances at courthouses. Currently, a file is processed through the Electronic Reports Table (MPE), through which documents can be digitised, creating a set of information contained in metadata in a digital format accessible to all legal operators involved.

Judicial Electronic File

The EJE is an automated case management system (initially for non-criminal cases), which the judiciary launched as a pilot in 2017. Before instituting the EJE initiative, each judicial file was made of a set of papers and had to be physically moved from one place to another to obtain a response to the claim made and the resolution of the procedure (see Box 5.4).

Box 5.4. The implementation of the Judicial Electronic File by the Peruvian judiciary

The EJE is focused on assuring more expedited and transparent justice services using new information technology (IT) tools. This service allows users to access and process their cases online, eliminating the need for most on-site appearances at courthouses.

In 2015, the judiciary adopted the electronic signature and the e-Notification System (SINOE) to simplify and speed up these common judicial procedures. Although the SINOE has multiplied the use of EJE by four, this is not mandatory. Indeed, lawyers need to register and agree to receive any communication through this mechanism. In addition to this voluntary practice, activating the notification still requires that the initial notification be carried out physically. Also, as part of the EJE, the judiciary has begun implementing supporting modules to present documents or requests related to a case, such as the e‑child travels and e-debtors request. Significant advances have been made in providing court e‑services, achieved through microforms and electronic files for labour and commercial cases in Peru.

The judiciary has already piloted the EJE in 60 courts in the Lima District (19 commercial courts, 29 labour courts, 7 customs courts and 5 courts for market issues). Implementing the EJE in these courts has been an important first step to test the main framework for its effective operation. The pilots generated considerable savings in time and use of paper (World Bank, 2019[20]). To date, according to the information shared by the judiciary, the EJE is used in 20 High Courts and 33 Specialised Courts throughout the country: 17 in charge of labour cases, 8 in charge of civil cases and 8 in charge of family cases (mainly regarding violence against women). It appears that the EJE has had an impact on reducing procedural times; in the case of civil procedures, they recently transitioned from written to oral and reduced their procedural times due to the EJE.

Source: (Poder Judicial, 2023), Expediente Judicial Electrónico website [Judicial Electronic File], https://eje.pe/wps/wcm/connect/EJE/s_eje2/as_inicio/ (accessed 11 September 2022); (World Bank, 2019), Project Appraisal Document on a Proposed Loan in the Amount of US$85 million to the Republic of Peru for Improving the Performance of Non-criminal Justice Services, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/288961560045670620/pdf/Peru-Improving-the-Performance-of-Non-Criminal-Justice-Services-Project.pdf.

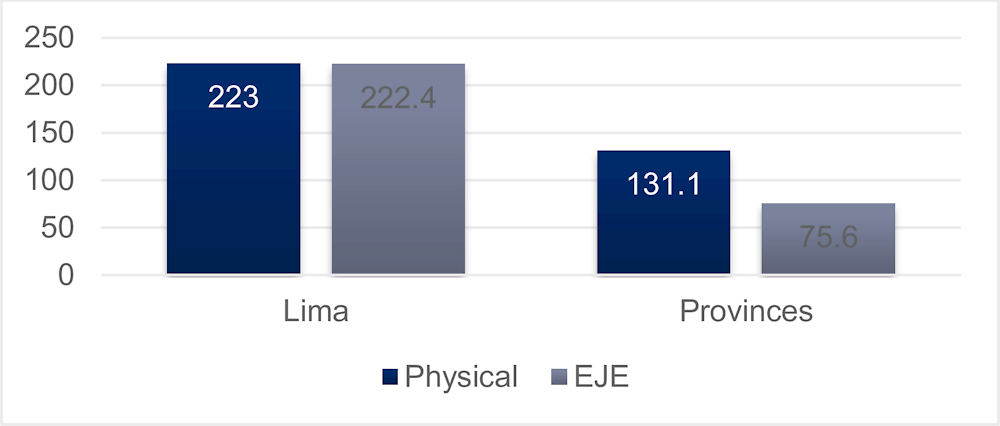

The EJE significantly reduced case length compared to physical paper filings, especially in rural areas. For example, in first-instance cases, for High Courts in the Department of Lima, it took 223 days to close a case using a physical file. Using the EJE, it takes 222.4 days (‑0.3% time reduction). For High Courts in the provinces, it took 131.1 days to close a case using a physical file; using the EJE, it takes 75.6 days (‑42% time reduction) (see Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3. Trial length in first instance: Physical file versus Judicial Electronic File (EJE)

Source: Peru’s judiciary (2022), information for the OECD.

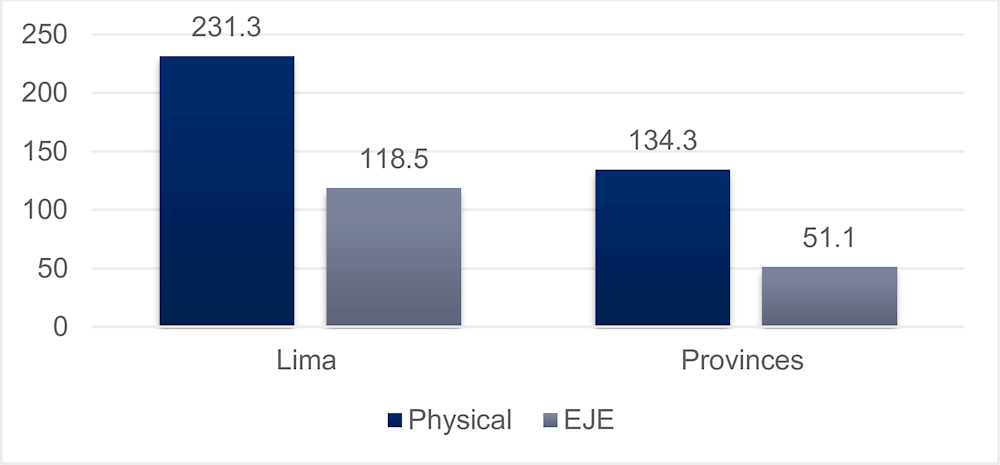

In second instance cases, for High Courts in the Department of Lima, it took 231.3 days to close a case using a physical file, while using the EJE, it takes 118.5 days (‑49% time reduction). For High Courts in the provinces, it took 134.3 days to close a case using a physical file, while using the EJE, it takes 51.1 days (‑62% time reduction) (see Figure 5.4).

Figure 5.4. Trial length in second instance: Physical file versus Judicial Electronic File (EJE)

Source: Peru’s judiciary (2022), information for the OECD.

Implementing the EJE for criminal cases has taken longer, primarily due to the recent nationwide completion of implementing the new CPP (see Chapter 3). However, stakeholders reported that thanks to international development assistance, Peru is now working to accelerate the implementation of the EJE in criminal procedures.

To successfully implement the EJE, justice institutions might consider establishing key common standards in terms of capacities and technological equipment to have the same level of digital development. In addition, the lack of interoperability, the digital gap (most evident in rural areas) and the lack of trainings for public officials on the EJE are still barriers limiting the optimal implementation of the EJE and its reach. Moreover, the impact of the EJE could be better monitored with more data on contexts and specific populations across the country. These data would help understand justice needs and how the EJE addresses or fails to address those needs in different areas.

Peru could also consider revising the e-filing system to respect the principles of transparency, inclusiveness, accountability and accessibility. There is still room for improvement in building institutional capacity and providing technological equipment to justice actors. This would ensure all parties have the same level of digital development to effectively implement the EJE and maximise its use across the system. There is also room for improvement to enhance public officials’ training on the EJE. Limited training and the lack of harmonised technological uptake thus still constitute barriers to the optimal implementation of the EJE. In addition, the impact of the EJE could be better monitored and evaluated to understand justice needs and whether they are being addressed effectively using the EJE.

Peru has taken a positive first step towards improving case management and digitalisation by implementing the EJE and measuring its impact. While the SIGE and the Electronic Prosecution file seem to have potential to follow this path, implementing monitoring and evaluation mechanisms could help fully assess their success.

Further, when measuring the impact of digitalisation tools in improving CR and DT, other aspects should be factored in, such as the impact of court management and resource allocation, the use of statistics and data-based approaches to case management and monitoring, infrastructure, and training. These aspects could be factored in, as the EJE alone does not resolve much if it only works within the judiciary, as many stakeholders may be involved in a case and thus require access to information.

Measuring court efficiency: Clearance rates and disposition times

The CNPJ has also undertaken significant reforms to address court congestion and implement actions and measures to tackle CR issues. Although this indicator is useful to measure the number of cases resolved or disposed of by the courts within a specific period, implementing additional measures, as is currently being done in OECD Member countries, can provide insights into the overall performance and effectiveness of the judicial system in Peru. This is important considering that operational challenges remain, and court congestion in Peru is still significant, as reflected in relatively low CR, high procedural burden, an average long trial length, and bottlenecks in several courts.

Peru would also benefit from measuring DT to identify the average time a case takes to be resolved once it enters the court system. Other indicators, such as case backlog (the number of pending cases not resolved within a certain timeframe), the efficiency of appeals (average time for an appeal to be decided), and the backlog rate in appellate courts, could also be useful. Measuring judicial productivity by assessing the number of cases handled by individual judges or judicial officers within a given period can indicate efficiency in case management. Finally, user satisfaction can be measured through surveys or collecting feedback from court users, providing insight into their satisfaction levels and perceptions of the court system's efficiency. It is, however, important to note that the accuracy of these measures depends on the availability and precision of data, highlighting the importance of improving data management, as discussed later in this chapter.

Court and case management

As seen in Chapter 4, the Executive Council of the Judiciary is responsible for case and court management. It holds administrative, budgetary, educational, digital and regulatory functions. The National Commission for Judicial Productivity and its Office for Judicial Productivity depend on the Executive Council and oversee the development of performance management policies and guidelines, monitor the functioning and productivity of the jurisdictional bodies, and propose actions for better judicial production.

In Peru, case management is primarily understood as case allocation and is based only on quantitative data. This means a case will be allocated based on a judge’s competency (specialisation) and caseload. However, the allocation does not account for judges’ needs, for example, assessing the complexity of different case types. Unlike many OECD Member countries that use CWA, Peru currently focuses on a quantitative analysis, which considers only the number of cases. It is essential to analyse the type of cases, recognising that each case type requires a different amount of judicial time and effort to process.

The judiciary has implemented monitoring activities to strengthen judicial productivity, improve the quality of decisions and accelerate the process to conclude cases. This has translated into particular attention being paid to monitoring and evaluating the jurisdictional offices with a low level of resolution of cases or inconsistencies regarding caseload, the settlement of cases processed with the old CPP, and other monitoring initiatives with a quantitative approach focused on the number of active and finished processes to promote.

While most initiatives aimed at promoting case management efficiency rely on a quantitative approach, the judiciary has recognised the need to strengthen its role in implementing measures with a qualitative approach to case management.

Regardless of the considerable advances that the CR and the EJE initiatives have meant for increasing the efficiency of the justice system, there is scope to develop case weighting and court performance indicators along with more qualitative approaches to measuring performance, in line with the trends in OECD Member countries. In this sense, judicial resources, such as judges and budgets, could be better allocated across the judiciary by implementing court and case management strategies, for example, across the country.

As Peru has been transferring part of the court's activities from real-time to digital– transforming them into e-courts – the judiciary has also begun implementing digital mechanisms to facilitate judges’ access to information, as seen in the previous section. It also granted them easier access to the decisions at key stages of the process (including admission, notification and sentence) and documents or requests related to a case (such as the e-reception desk, e-child travels and e-debtors request) and quick execution of decisions or preventive measures ordered by the court (such as e-seizures, e-judicial auction and e-edict). However, it is important to recall that court digitalisation should go together with other measures beyond ICT tools, such as the decongestion measures cited above.

5.3. The efficiency of ADR mechanisms

5.3.1. The use of ADR mechanisms in OECD Member countries

ADR mechanisms refer to the diverse ways people can resolve disputes outside a trial or court process. Common ADR comprises all mechanisms for resolving legal disputes without resorting to litigation processes in a court of law; these include mediation, arbitration and conciliation. ADR mechanisms may provide speedier, generally confidential, less formal, and sometimes less costly settlements to disputes between private parties. These alternative solutions are not supposed to replace ordinary justice but to complement it by reducing case backlogs and length. As explained later, a people-centred justice system should include ADR and informal options to provide a wide range of justice services that respond to people’s needs. Justice services should be readily accessible to anyone experiencing legal needs to help them resolve their problem.

ADR mechanisms may provide effective and efficient alternatives to litigants, drive settlements, assist courts in reducing caseloads, reduce costs and increase access to justice. Also, because they depend on the will of the parties, ADR services may preserve personal and business relationships, prevent future litigation, and increase the predictability of the process. In many judicial systems in OECD Member countries and beyond, ADR services have been recognised as an effective case management tool.

The trend in many OECD Member countries is that parties increasingly rely on ADR mechanisms as an alternative to formal court proceedings. Some opt for standalone, out-of-court proceedings, while others include them (especially conciliation) as part of an intervention of the courts. In any case, reforms aimed at strengthening ADR are still relevant for some OECD Member countries, while in others, the widespread use of ADR is a longstanding reality.

Recourse to mandatory court-related mediation also seems to be increasing. For example, in Belgium, following a 2019 reform, a judge may, at the beginning of proceedings, impose a recourse to mediation, ex officio or at the request of one or more parties if s/he considers that a reconciliation is possible. In Austria, the judicial system provides for mandatory mediation in diverse legal fields: some tenancy law matters before going to court; some family law matters based on an order issued by the judge; the family court can order a mandatory informative session if this is necessary for the best interest of the child; in criminal matters, a reference should be made to the withdrawal of the prosecution (diversion) – victim-offender mediation. Lithuania presents the most recent example in terms of ADR expansion. As of 2020, parties must try to resolve a family dispute through mediation before going to court, except for victims of domestic violence. Moreover, the court may order mandatory mediation in certain civil cases when an amicable resolution is likely. Free-of-charge trainings for mediators in Lithuania have increased the number of mediators in recent years (CEPEJ, 2022[5]).

A clear and comprehensive legal framework is an essential step for supporting the effective introduction and implementation of different ADR services. The availability of ADR mechanisms also affects the demand for judicial services. Indeed, disputes can be effectively and efficiently resolved through various ADR mechanisms, such as online dispute resolution, mediation and arbitration. The challenge for law makers is to design a justice system that supports parties in bringing their disputes to the right forum, depending on the nature and severity of the dispute. Hence, offering a range of ADR options is the best way to meet a pluridimensional and multifaceted demand. A practice adopted in some countries is that ADR services are developed and evaluated with input and feedback from the legal community, court users and other stakeholders. Law and policy makers could thus consider the needs of specific populations and adapt ADR services to them.

That said, evaluating the utility and efficiency of ADR depends on access to robust data and data collection practices. In fact, courts and ADR service providers need to rely on solid data and information systems to evaluate and measure the success of the services (in a way that also considers the user’s perspective), as well as identify trends and potential demands for additional or different programmes or identify any need for altering how the services are provided (OECD, 2021[21])

5.3.2. The use of ADR mechanisms in Peru

To increase the efficiency of its justice services, Peru has advanced in implementing ADR mechanisms (Box 5.5). There are four main types of ADR in Peru: conciliation, mediation, arbitration (including popular arbitration) and extrajudicial conciliation, as seen in Chapter 3.

Box 5.5. Recent reforms in Peru to improve ADR mechanisms (2008 onwards)

Centre for Popular Arbitration (Centro de Arbitraje Popular, or Arbitra Perú): The centre was created by the MINJUSDH in 2008 to settle minor disputes below PEN 99 000 Peruvian soles (EUR 24 750). The matters under its scope are evictions, claiming monetary debts, assuming obligations of doing or not doing, conflicts on property and possession, contract rescinding, division and partition of goods, contracts with the state, and annulment of contracts. The contract in dispute shall contain an arbitration clause or a covenant on arbitration. The plaintiff chooses the arbiter among the arbiters certified by the MINJUSDH. The claimant shall pay a small fee of PEN 70.29 (EUR 17.6) for using the Arbitra Perú service. In general, the assessment of popular arbitration is positive, even if it does not fully reach remote areas and rural communities. The ministry has also created a public service of conciliation free of charge, as seen in Chapter 6.

Mass conciliation exercises (Conciliación): Following Colombia’s example, in 2021, the MINJUSDH implemented these exercises throughout the country by providing conciliation services free of charge to citizens, aiming to reach the greatest possible number of people (most of them virtually). These are 3-day sessions, reaching an average of 150-180 conciliations per month. The matters that can be taken to conciliation include alimony, child support, custody, child visitation, eviction, payment of debts, compensation, issuance of public deed, property distribution, breach of contract and offer of payment.

Source: OECD fact-finding mission, March 2022. Peru’s responses to the OECD Questionnaire, July 2022.

5.3.3. Arbitration

Arbitration is constitutionally recognised as an alternative to the settlement of property-related disputes and is separate from the judiciary. The parties decide to resolve their conflicts by voluntarily submitting their case to the decision of an arbitrator or expert tribunal in the disputed matter. The parties may submit disputes to arbitration for which they have free disposition pursuant to law, as well as those authorised by law or international treaties or agreements. This legal framework has contributed to improving arbitration practices in the country (Montezuma Chirinos, 2018[22]).

Arbitration in Peru is a simple, short, and less formal process that ends with the arbitration “award” or compensation deciding the outcome of the dispute. The agreement to submit a case to an arbitration jurisdiction must be made in writing and based on consensus (civil and commercial arbitration, consumer arbitration, securities arbitration, etc.). Arbitration awards are final, and there is no recourse available against them, except in the case of arbitration awards that have incurred in one of the causes for annulment, usually associated with the violation of due process. In such cases, the aggrieved party can appeal to the judiciary. The entire arbitration process takes approximately 3 months, including the period for issuing the arbitration award, which is 30 days.

Popular arbitration, a service provided by the MINJUSDH, is also an ADR mechanism in which a third party, an arbitrator, facilitates mediating conflicts between two parties. In 2008, the MINJUSDH created the Centre for Popular Arbitration (Arbitra Perú) to solve conflicts, especially among micro and small business enterprises (MSMEs), professionals and civil society in general. However, this centre is only located in Lima, and the hearings are virtual. It numbers 179 arbitrators. The price of this service is PEN 70.29 (EUR 17.6), and it sees cases with claims for up to PEN 99 000 (EUR 24 750). Besides managing the Centre for Popular Arbitration, the MINJUSDH also shares information and promotes this service.

Based on information provided by the MINJUSDH, only 39 people used this service in 2021, with the most prevalent cases being eviction and the obligation to pay a sum of money, which were 34 out of the 39 total. However, of the 39 cases initiated in 2021, only 21 were concluded. This analysis indicates a low usage rate of the arbitration service, pointing to the necessity for broader dissemination and promotion. Crucially, there is a need to establish mechanisms that enable access for individuals outside Lima, particularly those with limited or no technological proficiency. The modest number of concluded cases also prompts questions regarding the service's effectiveness. Expanding the types of cases handled by the MINJUSDH and ensuring effective access to justice for users of arbitration services is essential. Enhancing the data and information system is also imperative. Currently, the MINJUSDH lacks a comprehensive system, relying instead on basic Excel tables for limited data. A more robust system would enable the government to understand the low uptake of this service, identify barriers to its use, and strategise on making the service more effective and centred on the needs of Peruvians. Chapter 6 provides more information on this service.

5.3.4. Mediation

In Peru, mediation serves as an alternative to prosecution, especially in youth criminality. The MINJUSDH, guided by the principle of opportunity, proposes an agreement with the victim.

While there is currently no legal framework for mediation in Peru, including the accreditation of the mediators and the establishment of mediation centres, the MINJUSDH recently approved a new Official Calendar for the progressive application of the Adolescent Criminal Responsibility Code (Supreme Decree No. 008-2023-JUS). The Code, approved in 2017 (Legislative Decree 1348) and its Regulation (Reglamento) in 2018 (Supreme Decree No. 004-2018-JUS), promotes the avoidance of criminal prosecution for minor cases involving adolescents. It encourages the intervention of a mediator or conciliator (duly trained on the issue) to facilitate dialogue between the parties to reach an agreement on the reparation to the victim, including restorative justice practices. Since 2018, the MINJUSDH has led the Permanent Multisectoral Commission composed of the Ministry of Interior, the Public Ministry and the Judicial Power to ensure the implementation of the Adolescents Criminal Responsibility Code (Legislative Decree 1348, Third Complimentary Final Disposition) (Presidenta de la Republica, 2023[23]). A previous calendar to implement the Code had been modified three times in the last two years, postponing its implementation in various regions (DS. 003-2022-JUS; DS. 010-2022-JUS; DS. 003-2023-JUS).

According to the new calendar, the Code will be implemented incrementally, starting in April 2024 in some judicial districts, with the full implementation scheduled for completion in 2028 (El Peruano, 2023[24]).

5.3.5. Judicial and out-of-court conciliation

Judicial conciliation is regulated in the Civil Procedures Code. It serves as an alternative conflict resolution mechanism provided by a judge by which the parties can conciliate their conflict in any stage of a judicial process before a second instance resolution. If the parties do not approve the use of conciliation, then the judicial process continues. The conciliation decision has the same effects as a judicial resolution.

Furthermore, Justices of the Peace have the power to settle certain types of disputes through conciliation on minor disputes related to ownership rights, except for crimes, small alimony and child support payments, tenancy evictions, and land property demarcation. They apply equity criteria for adjudication rather than adhering to ordinary law. Their decisions can be appealed in front of the Justice of the Peace Judge or the Specialised or Mixed Judge. Their conciliation settlement constitutes an enforceable document, like traditional out-of-court conciliation. However, there seems to be a void in the legal framework that encourages effective recourse to judicial conciliation. Also, the existing institutional weaknesses facing Justices of the Peace have hampered the implementation and monitoring of this mechanism, including the lack of an information system to record their cases.

Judicial conciliation is still underused in Peru. In 2021 and 2022, cases solved through conciliation processes accounted for less than 2% of incoming cases. Leadership is required to promote conciliation, digitalised tools and materials as one means to increase efficiency in justice and intercultural justice in remote areas.

On the other hand, extrajudicial conciliation is conducted outside a judicial proceeding. It is mandatory in some civil cases before launching a court proceeding, in contentious administrative cases (when previously agreed by the parties) and in labour cases. Conciliation in civil matters (especially on eviction, payment, compensation, termination of contract, breach of contract, inheritances’ division, and partition, among others) is legally mandatory prior to filing a lawsuit in court; otherwise, the judge declares the claim inadmissible. The process started in 2011 and is progressively entering into force throughout Peru.

Extrajudicial conciliation is also an alternative conflict resolution mechanism that allows people who have problems with alimony and child support, child custody, payment of debts, compensation, and evictions, among others, to solve these problems without having to go to court. Even though Peru has developed legislation that encourages the effective recourse to extrajudicial conciliation through the Conciliation Law in 2021 (Law 26872), many institutions have the mandate to conciliate, and conciliation is not dependent on the judiciary, causing limitations in the management, implementation, and monitoring of this mechanism.

As mentioned in Chapter 3, there are no co-ordination mechanisms between the judiciary, the MINJUSDH, the Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations (Ministerio de la Mujer y Poblaciones Vulnerables, MIMP), and the Ministry of Labour, which are the public institutions that offer extrajudicial conciliation services. This is more problematic given that the judiciary ends up enforcing conciliation decisions. Moreover, there is currently no overall information system that accounts for cases settled through extrajudicial conciliation by each institution, and there are no mechanisms in place to exchange information among institutions dealing with this mechanism.

The MINJUSDH is the main public institution that provides extrajudicial conciliation services, which are provided by public conciliation centres and free legal assistance centres (Centros de Asistencia Legal Gratuita, ALEGRAs) at the national level (see Chapter 3). It also supervises the management of the more than 3 000 private conciliation centres at the national level. According to the MINJUSDH, this supervision role accounts for more than half of the work of the Conciliation Direction of the Ministry. Furthermore, the limited number of extrajudicial conciliators that deal with all the cases has created a backlog of cases and risks the effectiveness of this service and people’s access to justice. According to the MINJUSDH, there is a 60% deficit of conciliators to deal with all the cases. In 2021, 2 879 cases were initiated, and 2 556 were concluded by the 89 extrajudicial conciliators in the 90 conciliation centres at the national level (see Chapter 3). The fact that there is one conciliator for each conciliation centre, which are located mostly in urban and populated areas, highlights the little funding and importance that the implementation of this public service is given.

Moreover, according to the MINJUSDH, training and capacity building of the conciliators is required for them to better understand the purpose of conciliation and their role in providing it for effective access to justice. Unlike arbitration, the extrajudicial conciliation service has a system for the follow-up of conciliation processes (SISCONE 3.0.1.). The information gathered regarding the cases is used to allocate more personnel to areas with more need and experience in certain topics according to demand. This good practice of using data to promote access to justice where people most need it can be strengthened by better allocating resources to meet demand.

Finally, considering the small number of cases brought for conciliation each year (in a country of 34 million people), better dissemination of this service as a mechanism for conflict resolution is required, as it is not commonly used or known in Peru. Like judicial conciliation, there is scope to promote extrajudicial conciliation as one means to increase efficiency in justice.

Overall, Peru has made considerable progress in creating legislation on ADR, mostly for extrajudicial conciliation, addressing when, how, and by whom this mechanism is used. However, Peru could benefit from a clearer and more detailed legal and regulatory framework for all ADR mechanisms (especially for judicial conciliation and mediation) to improve their use and implementation nationwide. Peru could continue further promoting the use of ADR as one of the means to increase efficiency in justice while implementing a comprehensive approach to the services they provide. Peru could also benefit from enhancing its information and data systems to better understand how and why Peruvians use these mechanisms and how they contribute to reducing court-based litigiousness. Indeed, greater efforts could be made to more deliberately evaluate the impact of ADR mechanisms on the judicial system in Peru with input and feedback from the legal community, court users and other stakeholders. In this connection, the current Public Policy for the Reform of the Justice System (2021-2025) advocates for the need to carry out a diagnostic study on the effectiveness of conciliation as an ADR mechanism (Consejo para la Reforma del Sistema de Justicia, 2021[19]).

5.4. Digitalisation and justice service efficiency

5.4.1. Strategies on the digitalisation of justice services

Digitalising the justice system in OECD Member countries

Digital tools are key for breaking physical access barriers to justice. They seek to automate existing processes, enhance efficiency, create new pathways and solutions and provide direct access to legal and justice services for all. According to the OECD Good Practice Principles for People-Centred Justice, the Governance Enablers and Infrastructure Pillar incorporates approaches to establishing whole-of-government systems to ensure access to technology and justice services, justice system simplification and people-centred reorientation of justice services to all (OECD, 2021[2]). Furthermore, the OECD Recommendation on Access to Justice and People-Centred Justice Systems states that the implementation of a governance infrastructure that enables people-centred justice requires digital transformation across the justice sector by maximising the potential of technology and data in the design and delivery of people-centred justice services while ensuring trustworthiness and transparency of digital tools (OECD, 2023[25]).

The digital transformation of a justice system increases:

accessibility by providing the best information available and a better understanding not only of the way a justice system works but also of the available legal instruments to ensure recognition of people’s rights and legal needs

institutional efficiency by growing productivity and diminishing costs of transactions, as well as connecting different services beyond courts

effectiveness by improving processes, reducing the duration of procedures – thus both saving time and lowering costs – and putting systems in place for document resource administration

Transparency and coherence of decisions through improved control of cases and better qualitative evaluation of outputs

peoples’ trust in institutions.

Trends in OECD Member countries focus on using technology to digitalise justice services in a comprehensive and integrated manner. Also, OECD Member countries' good practices show that digital strategies affect justice effectiveness more directly when there are co-operation/co-ordination mechanisms in place and well-defined responsibilities. Furthermore, effective digital justice strategies tend to be articulated around a holistic vision that aims to ensure that all groups (including the most disadvantaged and vulnerable) have equal digital access to a full range of quality legal and justice services. OECD best practices suggest that national strategies related to the digitalisation of justice services must be comprehensive and integrated, and should cover legal services, dispute resolution services, technology and data.

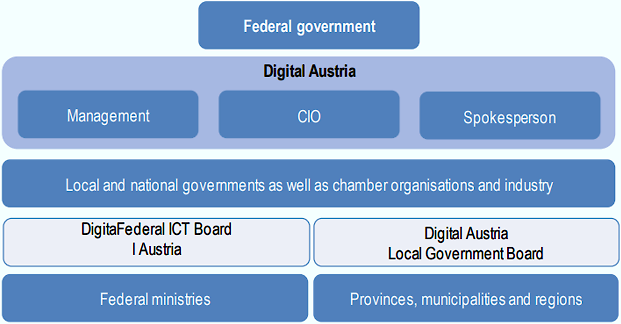

While integrated strategies can facilitate consistency and help create a people-centred ecosystem, in the case of separate strategies, it is important to ensure consistency, coherence and alignment towards a shared objective of serving people, along with the robust inter-institutional co-ordination that such coherence and alignment require. Most importantly, evidence shows that a useful digital strategy requires and should be aligned with a clear data strategy (OECD, forthcoming[26]). In addition, clearly defined responsibilities and co-operation mechanisms enabled by digital technologies can significantly improve the efficiency and effectiveness of justice service delivery. An example of good practice in this regard is the robust co-ordination mechanisms and clear roles assigned to all participants of the digital strategy in Austria, where the Federal Ministry of Justice is also seen as a reliable partner and accelerator for digitalisation projects. The relationship between the ministry, the courts and stakeholder groups is often described as very productive (Box 5.6).

Box 5.6. The Austrian model of digital strategy leadership

Digital government in Austria is led by the Federal Chancellor, the Federal Executive Secretary for eGovernment, and the “e-Government platform” has been created under his leadership. There are strict co-ordination mechanisms and a clear role allocation to each actor.

Source: (OECD, 2016[27]), OECD Public Governance Reviews: Peru: Integrated Governance for Inclusive Growth, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264265172-en; http://scdb.wustl.edu/.

Most importantly, when developing digital strategies, it is essential to identify and include the needs of specific user groups, particularly the most vulnerable that usually are left outside the scope of justice services. Hence, digital innovations and policies should be designed with the needs of underprivileged, remote, and aged populations in mind. A good example is the offline software developed in Colombia for rural communities called LegalApp Rural (Box 5.7). This tool provides access to justice services related to family, crime and rural issues, among others. This software was given to public libraries nationwide so it could be used by people with no access to computers at home. This has been particularly useful for people living in remote and vulnerable areas without Internet connections (OECD, forthcoming[26]).

Box 5.7. Digital innovation in justice services: Colombia’s LegalApp Rural

LegalApp Rural, developed in Colombia, provides access to justice services related to family, crime and rural issues, among others.

By typing in keywords, people can learn what to do about a concern or case, the authority or institution they can go to, the exact location in their municipality, and whether their procedure requires a lawyer. It also allows access to different routes of justice on frequent legal conflicts, such as problems with a lease, alimony, child support, payment of debts, conflict between neighbours, personal injuries, theft, liquidation of employment contracts, non-payment of social benefits and processes of land restitution, among others.

This software was given to mayors’ offices and public libraries all around the country so it could be used by people without computers at home. This has been particularly useful for people living in remote and vulnerable areas without Internet connections (OECD, forthcoming[26]).

Source: Ministerio de Justicia y del Derecho de Colombia (2019) “Legal App sigue impulsando en las Regiones el Acceso a la Justicia”, https://www.minjusticia.gov.co/Sala-de-prensa/Paginas/LegalApp-sigue-impulsando-en-las-regiones-el-acceso-a-la-justicia.aspx (accessed 26 June 2023).

It is important to note that the success of these strategies must take into consideration the reality of people’s digital literacy. A digital divide may emerge, wherein certain disadvantaged groups experience reduced access to justice services and pathways due to the lack of available technology or digital literacy (OECD, 2019[12]). As discussed in Chapter 6, digital literacy must be integrated into the strategy to empower people and enhance knowledge of rights, enabling meaningful participation in the justice system when needed.

Digitalising the justice system in Peru

The Law of Digital Government (Legislative Decree 1412, from September 2022) establishes that digital government includes digital technologies, digital identity, interoperability, digital services, data, digital security and digital architecture, which work together to promote people-centred services, public institutions’ internal management and the delivery of services that respond to people’s needs.

In 2020, the National System of Digital Transformation was created, headed by the Digital Government Secretariat of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers (PCM), with the aim to strengthen and promote the digital transformation of public institutions, the private sector and society; and promote digital innovation and access and inclusion to and in digital technology in the country. Participants include the PCM; several ministries, notably the Ministry of Economy and Finance and the MINJUSDH (among others); the National Council of Science, Technology and Technological Innovation (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Tecnológica [Concytec]); the Digital Government Committees; and organisations from the private sector, civil society and academia. The High-Level Committee for a Digital, Innovative and Competitive Peru is the co-ordination mechanism between public institutions and external stakeholders for the promotion and implementation of digital transformation.

Institutions responsible for implementing and regulating the state’s digital strategy in Peru are recent, with most of them being established in the past decade (Box 5.8).

Box 5.8. Institutions in charge of implementing and regulating the digital strategy in Peru

The Secretariat of Digital Government (Secretaría de Gobierno Digital, SeGDi): Created in 2017 and attached to the PCM, the Secretariat is the governing body in matters of digital government (digital technologies, digital identity, interoperability, digital service, data, security and digital architecture) and adopts rules and procedures related to state digitalisation. The Secretariat oversees formulating and proposing national and sectoral policies, plans, standards, regulations, guidelines and strategies on IT and Electronic Government. It is also the governing body of the National Information System. The Secretariat’s mandate covers all institutions, including those that are autonomous and those that are part of the justice system (see Chapter 3).

High-Level Committee for a Digital, Innovative and Competitive Peru (Comité de Alto Nivel por un Perú Digital, Innovador y Competitivo): This committee is the multisectoral co-ordination mechanism for the promotion and implementation of initiatives and actions related to the development of digital government and the integration of civil society, the private sector, academia and citizens.

Laboratory of Government and Digital Transformation of the State (Laboratorio de Gobierno y Transformación Digital): Also attached to the PCM, this laboratory was created in 2019 to promote the participation of civil society, academia and other actors in government projects and policies regarding digital transformation; strengthening the transfer of knowledge within the public sector; and promoting spaces to strengthen digital innovation, analytics, data science and governance, and digital security, for the deployment of government and digital transformation.

National Commission for Management and Technological Innovation of the Judiciary (Comisión Nacional de Gestión e Innovación Tecnológica del Poder Judicial): Created in 2019, the commission aims to ensure speedy and transparent judicial procedures. This commission is also in charge of implementing digitalisation and new technologies to improve the efficiency of judicial procedures, especially by implementing and monitoring the EJE in non-criminal cases. It is composed of the Head of the judiciary and the Executive Council; the counsellor responsible for the Institutional Technical Team of the new Labor Procedure Law; the counsellor responsible for the Judicial Office Management Unit; the president of the Working Commission of the Electronic Judicial File (EJE); and the General Manager of the judiciary.

Digital Government Committees (Comités Digitales de Gobernanza): Created in 2018, these committees are governance entities within every institution of the public administration, including those institutions that are part of the justice system, in charge of leading, evaluating and following up on the digital transformation process as well as designing the e-government plan of a given public institution. These committees are also in charge of promoting collaboration and exchange of information with other institutions. These are composed of the head of the public institution, a head of government and digital transformation, a person responsible for IT, one person from human resources, one from information security, one from the areas of citizen attention, one from management, and a legal officer. The committees are part of the National System of Digital Transformation.

Technical Secretariat of the Council for the Reform of the Justice Reform (Secretaría Técnica Para la Reforma del Sistema de Justicia, CRSJ): The Public Policy for the Reform of the Justice System (2021-2025) establishes as one of its priority objectives the enhancement of data management and interoperability in the justice system. As such, the CRSJ, through its Technical Secretariat, oversees monitoring the implementation of recommendations and activities included in the policy to reach interoperability in the justice system.

Source: OECD’s own elaboration.

Even though significant improvements have been made to digitalise the government, including co-ordination efforts, there does not appear to be a leading actor to carry out this co-ordination within Peru’s justice system to enable it to pursue coherent, whole-of-government, strategic objectives to implement an integrated digital justice strategy. There seems to be little evidence of co-ordination leadership and capacity across justice institutions (maybe through their Digital Government Committees) or of a plan to implement digital justice system-wide in Peru. Furthermore, it is not yet clear how the government plans to integrate existing digitalisation developments within the judiciary (implemented individually by justice institutions) or within other justice institutions (such as digital technologies to resolve disputes and mechanisms to improve interoperability across justice institutions) into the broader government digital strategy at the local, regional and national levels. On justice, proper leadership in this area requires the establishment of conditions that would enable the Secretariat of the PCM to provide robust, strategic, government-wide guidance and play its co-ordination and monitoring role effectively to enable the effective digitalisation of the entire justice system in a coherent and integrated fashion.

5.4.2. Harnessing digital technology for dispute resolution

The increasing use of digital technologies to resolve disputes in OECD Member countries

Online dispute resolution is understood to encompass all sorts of dispute resolution mechanisms (ranging from mediation, the Ombuds Office’s schemes, and arbitration to court litigation) that employ technology to solve conflicts by using electronic means. These can include digitalised justice services through digitalised platforms, such as websites or apps, and tools or processes, such as online solution explorers to diagnose the dispute and obtain free legal information, standard templates and technology-driven dispute triage.