This chapter focuses on the constitutional framework defining the separation and balance of powers between Peru's executive, legislative, and judicial branches and their relationship with the constitutionally autonomous institutions. It then defines the institutions that are part of the justice system, first as detailed by the Constitution, then from a people-centred approach, and lists their responsibilities and scope of services they are responsible for delivering, including their relationship with intercultural justice. Finally, this chapter evaluates the existing inter-institutional co‑ordination and co‑operation mechanisms Peru has implemented to provide quality people-centred justice services and compares them with OECD Members’ experiences and good practices.

OECD Justice Review of Peru

3. Institutional set-up and co‑ordination in Peru’s justice system

Abstract

3.1. Introduction

The previous chapter highlighted the rule of law as a core principle defining justice systems in OECD Member countries, the steady progress towards people-centred access to justice, and the degree to which this principle applies in Peru.

This chapter assesses the institutional set-up of the justice system in Peru and the degree to which inter-institutional co-ordination strengthens the system’s efficiency and transparency, hallmarks of the rule of law and people-centred access to justice in OECD Member countries. For these purposes, this chapter first presents an overview of what is constitutionally defined as part of the justice system in Peru. It then describes the constitutional framework defining the separation of powers as existential to sustaining the rule of law and presents the strengths and challenges framing how this principle is given effect in practice in Peru. Finally, it analyses the co-ordination systems that have been implemented to ensure better coordination and co-operation across justice institutions.

This review adopts a holistic people-centred approach; hence, the scope of this analysis is broader than the judiciary itself as defined by Peru’s Constitution. The term “justice system” used in this chapter and throughout this review is more comprehensive and takes a justice service deliverable approach by assessing arrangements beyond the judiciary or the judicial branch as such. This review covers institutions in the executive branch, the autonomous constitutional institutions, alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms and the specialised justice frameworks, including Indigenous justice.

As noted in Chapter 2, since 2003, Peru has put forward a series of major justice reform plans whose implementation has been partial, unco-ordinated, and fragmented and has had limited system-wide impact on the current justice system. These include the latest justice reform initiative (2021-2025). Indeed, its full implementation has yet to be achieved, and challenges remain in terms of the justice system’s efficiency and effectiveness in serving all Peruvians.

3.2. Institutional set-up

3.2.1. The separation of powers in Peru

As in most modern democracies, Peru’s state is arranged pursuant to the principle of separation of powers (art. 43). As stated in Peru’s Constitution (1993), the state comprises three core branches: the executive, legislative and judicial branches. Each branch is assigned separate powers with specific functions that help balance them (see Box 3.1).

Box 3.1. Roles and responsibilities of the different branches of power as defined in Peru’s 1993 Constitution

Executive branch: Responsible for enforcing the law. The President is elected for a single five-year term, with no right to immediate re-election (art. 112). As Head of State and Government, the President is the guarantor of the executive power and the leader of the Armed Forces and the National Police. Among other functions, the President observes and enforces the Constitution and laws, represents the state, manages the general policy of the government, ensures domestic order, can regulate laws and issue decrees and resolutions, manages the public treasury, and can promulgate emergency decrees (art. 118). The direction and management of public services are entrusted to the Council of Ministers, comprised of 18 ministries, and chaired by the President of the Council of Ministers, who is mandated to co‑ordinate across ministries and is the spokesperson for the Government, all of whom are appointed by the President of the Republic (art. 121-122).

Legislative branch: The Congress is vested with the legislative power. It is unicameral and is comprised of 130 members elected for a five-year term by the citizens (art. 90), who, according to the Constitution, are not responsible to any authority or jurisdictional body for votes cast or opinions expressed in the exercise of their suffrage (art. 93). This branch adopts laws and legislative resolutions, and interprets, amends, or derogates existing laws, ensures respect for the Constitution and the laws, and exercises authority to enforce the responsibility of those who break the law; approves treaties; approves the budget and the general accounts; and exercises all other powers indicated in the Constitution and that properly rest within the legislative function (art. 102).

Judicial branch (also referred to as the judiciary): The Constitution assigns responsibility for the administration of justice to the judiciary, which is comprised of jurisdictional bodies: the Supreme Court of Justice, the Superior Court, Jueces Especializados o Mixtos (Specialised or Mixed Courts), Jueces de Paz Letrados (Justices of the Peace Courts) and Jueces de Paz (Justices of the Peace); and governance bodies that exercise their administration (art. 143). The Constitution also defines five additional autonomous constitutional justice institutions. These include: the Constitutional Court, the National Board of Justice (Junta Nacional de Justicia), the Public Prosecutor’s Office (Ministerio Publico), the National Jury of Elections (Jurado Nacional de Elecciones) and the Ombuds Office (Defensoria del Pueblo). The President of the Supreme Court is the head of the judicial branch (art. 144). The Constitution expressly enumerates the principles and rights of the jurisdictional function, including, among other things, the principle of judicial independence, the unity and exclusivity of the jurisdiction function, the observance of due process, the public nature of proceedings, the plurality of the jurisdictional level, the principles of never failing to administer justice, the principle that no one should be punished without judicial proceedings, the principle of not being deprived of the right of defence, the principle of free administration of justice and free defence of persons of limited means and other cases, and the participation of the people in the appointment and removal of judges (art. 139). The independence of the judiciary, whose observance is guaranteed by the state, is enshrined in the Constitution and will be presented in Chapter 4.

Source: The Constitution of Peru (1993).

As a guarantor of the separation of powers between the branches and autonomous institutions, the Constitution defines a system of checks and balances to secure a balance of powers and the state's accountability in ensuring each branch holds the other accountable to Peruvians. The Constitution places a strong emphasis on the balance of powers, especially between the executive and the legislative branches. In this regard, it establishes several key constitutional tools, especially between the executive and the legislative branches. These checks and balances are also mentioned in the regulations governing the functioning of Congress. However, these constitutional powers have not been subject to further specification or delimitation through laws and regulations. This has allowed for various interpretations of these constitutional mechanisms. In some cases, it has led to their abuse for political reasons. Those more frequently used over the past five years include the presidential vacancy for moral incapacity, the motion of censure (moción de censura) and the constitutional accusation (Box 3.2).

Box 3.2. Constitutional tools to ensure the balance of powers between branches

The “motion of confidence” or “no confidence” (cuestión de confianza), in ministerial initiative and its related “motion of censure” (moción de censura), can be adopted by Congress. These are the mechanisms by which Congress validates and makes effective the political responsibility of the Council of Ministers or an individual minister (Constitution, art. 132). A motion of censure is presented by at least 25% of the congresspersons, while a motion of confidence is by ministerial initiative. In the event of the adoption of a motion of censure, following a debate by Congress and the approval of more than half of the representatives, the Council of Ministers or the indicted minister(s) are required to resign and be replaced (Regulation of the Congress, arts. 82 and 86). In a single year (July 2021 to July 2022), four ministers were censured or forced to resign by Congress using the mechanism of a censure motion against ministers (moción de censura).

The presidential power to dissolve Congress: The President of the Republic has the power to dissolve Congress and call for new elections if Congress censures or denies confidence in two Councils of Ministers (Constitution, art. 134).

The Constitutional accusation (acusación constitucional): The Permanent Assembly of the Congress can accuse the President of the Republic, a member of the Congress, a minister, a member of the Constitutional Court, a member of the National Council of the Judiciary (now the National Board of Justice), a Justice of the Supreme Court, Supreme Prosecutors, the Ombudsperson, and the Comptroller General for any violation of the Constitution or any crime committed during their duties (Constitution, art. 99; Regulation of the Congress, art. 89). Following a constitutional accusation, a “Political Pre-trial” (analogous to an impeachment trial in the US House of Representatives) is held in Congress to decide whether Congress will suspend the accused official, declare them ineligible for public service for up to ten years or remove them from office. In the case of a formal criminal accusation, the Public Prosecutor files criminal charges before the Supreme Court (Constitution, art. 100). During President Pedro Castillo’s government (2021-22), the constitutional accusation was presented six times against former President Castillo, former Vice President Dina Boluarte, and the President of the National Jury of Elections (Jurado Nacional de Elecciones, JNE). Likewise, in 2023, it was filed against the former Public Prosecutor Zoraida Ávalos, who was ultimately disqualified for five years from holding public office..

The power to request information from public entities: Congress can request ministries and other public institutions to provide reports on the issues they consider meaningful for executing their functions. It can create special commissions that investigate any matter of public interest (Constitution, arts. 96 and 97; Regulation of the Congress, arts. 87-88).

Approval by Congress of the executive’s Budget Law. The execution of the Budget Law, as presented by the executive, requires negotiation and approval by Congress. Each year, the President of the Republic sends the draft Budget Law to Congress as prepared by the Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF). The draft bill is debated, reviewed and approved by Congress, which can amend it. Hence, budget allocations and spending depend first on the executive branch, which prepares the budget and then on the approval of the Budget Law by the legislative branch (Constitution, arts. 78 and 80; Regulation of the Congress, art. 81) (see Chapter 4).

The declaration of presidential vacancy: Congress can declare the position of President of the Republic vacant if a majority of its members finds that the President presents permanent physical or moral incapacity. (Constitution, art. 113[2]); Regulation of the Congress, art. 89[A]). The legislative branch has also used this as a means of control. Since 2017, a motion of presidential vacancy for moral incapacity has been used at least seven times against three presidents: Pedro Pablo Kuczynski (2018), who resigned after a second vacancy motion; Martín Vizcarra (2019 and 2020), whose vacancy was declared by Congress after two attempts; and three times against Pedro Castillo (2021 and 2022), whose vacancy was ultimately approved in 2022. After the destitution of former President Martin Vizcarra, the Constitutional Court was given the opportunity through a referral to the Court to regulate the definition of “moral incapacity,” which has been broadly interpreted and used by Congress to control the executive (Landa Arroyo, 2020[1]). However, the Court declined to regulate, declaring the request inadmissible, thereby forfeiting the opportunity to define objective parameters that would define how this mechanism is to be applied (Tribunal Constitucional, 2020[2]). This prompted the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights to publicly express its concern over the repetitive and arbitrary use of this tool (Inter-American Commission of Human Rights, 2022[3]; Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 2023[4]).

Source: (Landa Arroyo, 2020[1]), “Crisis constitucional en el Perú: tres presidentes en siete días [Constitutional crisis in Peru: three presidents in seven days]”, Agenda Estado de Derecho, https://agendaestadodederecho.com/Peru-tres-presidentes-en-siete-dias/; (Tribunal Constitucional, 2020), “Caso de la vacancia del presidente de la República por incapacidad moral [Case of vacancy of the President of the Republic for moral incapacity]”, Judgement 0002-2020-CC/TC, 19 November 2020; (Inter-American Commission of Human Rights, 2022), “CIDH reitera preocupacion por la inestabilidad politica en el Peru y su impacto en los derechos humanos [The IACHR reiterates its concern at the political instability of Peru and its impact on human rights]”, OEA Press release, 25 March 2022, https://www.oas.org/es/CIDH/jsForm/?File=/es/cidh/prensa/comunicados/2022/063.asp; (Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 2023), “Situación de Derechos Humanos en Perú en el contexto de las protestas sociales [Situation of Human Rights in Peru in the Context of Social Protests]”, OAS, Washington, DC, https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/jsForm/?File=/en/iachr/media_center/preleases/2023/083.asp.

This has led the Constitutional Court, the autonomous institution in charge of interpreting the Constitution and resolving inter-branch conflicts, to interpret and further develop the ways and means that can be used to apply some of these tools. However, the lack of a proper regulatory framework to ring-fence the application of the constitutional control mechanisms described in Box 2.3 has allowed for their frequent and arbitrary use, undermining the balance and separation of powers.

The role of the Constitutional Court has been fundamental in interpreting the Constitution and allocating powers properly when problems associated with governance have arisen between the different branches. This reinforces the importance of this tribunal's independence and impartiality in guaranteeing constitutional stability.

The incidences of misuse of these constitutional mechanisms have affected the political landscape more broadly. The country has experienced several challenges, leading to disagreements between political groups and parties within both the legislative and executive branches. This environment has resulted in conflicts between public powers, extending even to constitutionally autonomous institutions within the justice system. Several commentators indicate that these dynamics have had a detrimental effect on Peru’s governance and ability to implement strategic reforms (Alessandro, Lafuente and Santiso, 2014[5]; Levitsky, 2016[6]; Tanaka, 2017[7]). This dynamic was most recently illustrated in December 2022 when former President Castillo attempted to dissolve Congress and rule by decree. This culminated in Vice President Dina Boluarte assuming the presidency, amidst peaceful and violent protests resulting in multiple deaths, mostly civilians, between December 2022 and January 2023 (Defensoria del Pueblo, 2023[8]).

This has led the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR) to express its concern over the repetitive and arbitrary use of the constitutional accusation against the other branches of power and constitutionally autonomous institutions, the presidential accusation based on permanent moral incompetence, and the dissolution of the Congress once the legislature refuses twice to approve proposed councils of ministers. The IACHR has called on the State of Peru to regulate and define these mechanisms (Inter-American Commission of Human Rights, 2022[9]; Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, 2023[4]).

Political instability has also degraded the quality and delivery of public services, including justice services, partly due to the lack of long-term planning, worsening institutional fragmentation, and a corresponding absence of effective inter-institutional co-ordination, all fundamental for properly designing and delivering these services to the people.

3.2.2. Mapping Peru’s justice system

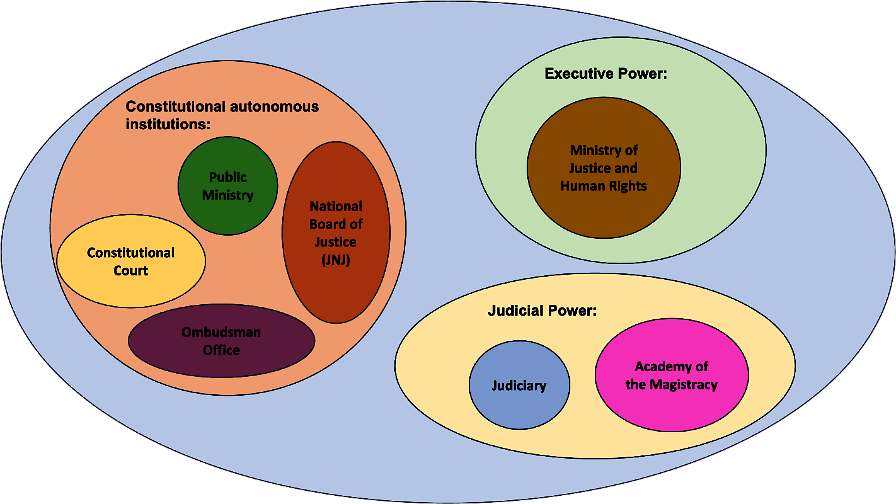

As stated in Peru’s Constitution (Figure 3.1), the administration of justice is exercised by the judicial branch and its jurisdictional bodies (Table 3.1). The Constitution also mandates additional constitutionally autonomous institutions to play a role in ensuring access to justice and in the administration of the justice system across the country: The National Board of Justice (arts. 150-157), the Public Ministry (arts. 158160), the Constitutional Court (arts. 201-205) and the Ombuds Office (arts. 161-162), which even though is not a jurisdictional body, is mandated to protect the constitutional rights of citizens (as part of the Judicial Power), the judiciary and the Academy of the Magistracy and (as part of the executive power) the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights (Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos, MINJUSDH).

Figure 3.1. Peru’s justice system institutions recognised by the Constitution

Source: OECD elaboration

Peru has adopted broader approaches to defining its justice system in its latest justice reform initiatives by including the institutions that play a role in access to justice. As detailed in Chapter 2, the National Plan for the Reform of the Administration of Justice (2004), prepared by the Special Commission for the Integral Reform of the Administration of Justice (Comisión Especial para la Reforma Integral de la Administración de Justicia, CERIAJUS), adopted a systemic approach in its analysis of the justice system. It identified as part of the judicial system: the Public Ministry, the National Council of the Magistrature (now the National Board of Justice), the Constitutional Court, the Academy of the Magistracy, the Ombuds Office, the MINJUSDH and the Justice Commission of the Congress (CERIAJUS, 2004[10]).

The current justice reform initiative, the Public Policy for the Reform of the Justice System (2021-2025), defined its scope even more broadly by adding the Ministry of the Interior, the National Police, the National Jury of Elections, MEF and the peasants’ self-defence groups (rondas campesinas) (Law 30942, art. 2).

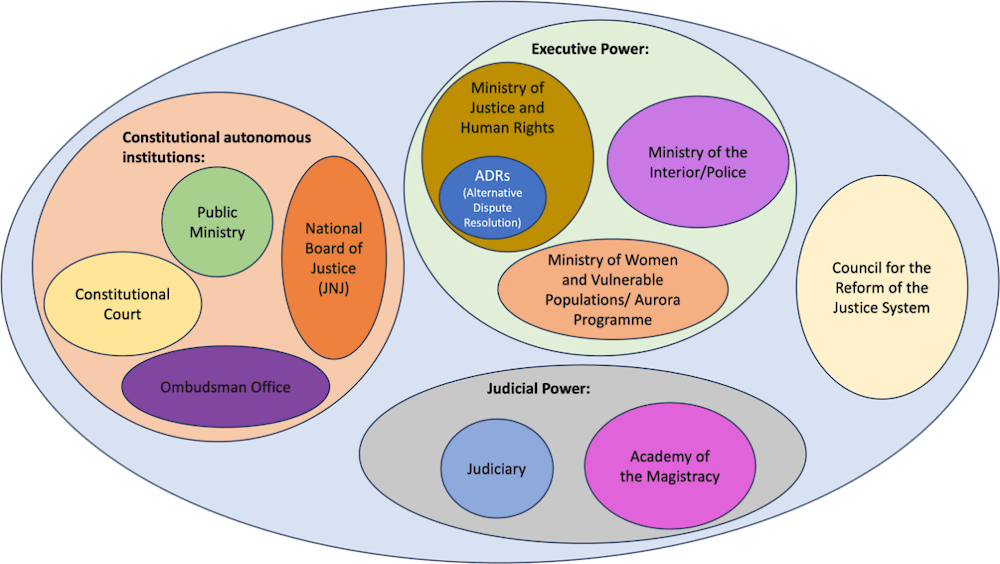

Taking into consideration Peru’s latest initiatives for justice reforms and using the OECD people-centred approach, Peru’s justice system could be summarised as follows (Figure 3.2) to which should be added the above-mentioned bodies: the Constitutional Court as part of the constitutional autonomous institutions, the Ministry of Interior/the Police and the Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations through the Women’s Emergency Centres of the AURORA Program (see Box 3.6 further below) as part of the executive power, and the Council for the Reform of the Justice System (Consejo para la Reforma del Sistema de Justicia, CRSJ) as the latest council created to formulate, co‑ordinate and monitor the implementation of the 2021-2025 Reform of the Justice System (Chapter 2).

Figure 3.2. Mapping of Peru’s justice system from a people-centred approach

Source: OECD elaboration.

3.3. Judicial Power within Peru’s justice system

3.3.1. The judiciary

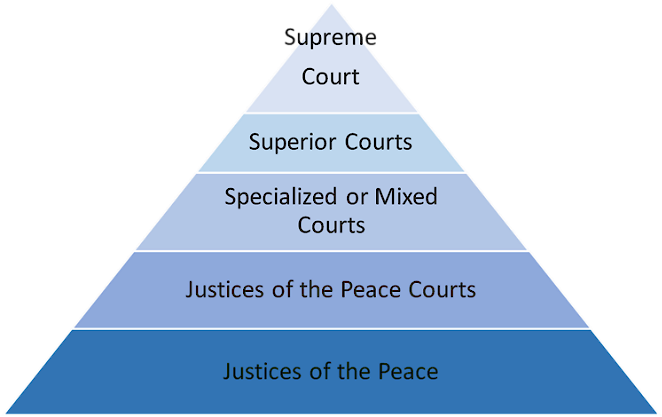

An integral part of the justice system in Peru, the judiciary or judicial branch presents a pyramidal structure comprising the Supreme Court, Superior Courts, Specialised or Mixed Courts, the Justices of the Peace Courts, and the Justices of the Peace (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3. The judicial branch

Source: OECD elaboration with information from Poder Judicial (2022), Organization Chart of the Supreme Court and Governance and Control Bodies.

In each of the 35 judicial districts of Peru, management responsibilities are assigned to the Presidents of the Superior Courts, the Executive Councils of the Judiciary, and the Plenary Chambers of the Courts (Organic Law of the Judiciary, art. 72), as further detailed in Chapter 4.

The structure and summary of the competencies of Peru’s courts are summarised in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1. The jurisdictional bodies in Peru: Structure, presence and competences

|

Type of court |

Number |

Main powers |

|---|---|---|

|

Supreme Court (Corte Suprema) |

1 |

The highest level of the judicial system and the last instance before which people can appeal the sentences of all judicial processes coming from any Superior Court of Justice in the country. It is organised in chambers or panels (salas) or fields of law (e.g. civil, criminal) and a Sala Plena (Plenum). Based in Lima, the capital of Peru. |

|

Higher or Superior Courts (Cortes Superiores) |

35 |

They are in each judicial district. They hear appeals from specialised courts within the judicial district or regions. It is organised in specialised or mixed chambers (e.g. criminal, civil, and labour, according to the needs of the judicial district). |

|

Specialised or Mixed Courts (Juzgados especializados o mixtos) |

1 951 |

Depends on the Superior Court and functions in local areas. Jurisdiction for a specialised area of law (e.g. civil, criminal, administrative, constitutional, commercial, labour). In geographical areas with a scarce number of cases and no specialised courts, they are called courts of mixed or combined jurisdiction, dealing indistinctly with all types of legal cases (juzgados mixtos). Solve the appeals on the sentences handed down by the Justices of the Peace Courts. |

|

Justices of the Peace Courts (Juzgados de paz letrados) |

651 |

They were created to administer justice in rural areas and usually represent one or more districts. They refer their sentences according to the respect of the national law. They see cases for small fines and fast resolution (on alimony, child support payment, violence against women and enforcement of payments and debts). They see conciliation cases (an ADR mechanism created to find an agreement between both parties and avoids the need to go to trial). They depend on the Superior Court, which determines where they can exercise their functions. They solve appeal cases of Justice of the Peace (Jueces de Paz). First-instance judges, their decisions are appealed before the specialised courts. The Justice of the Peace judge must be a lawyer and adjudicate according to the national law. |

|

Justices of the Peace (Jueces de paz) |

5 966 |

The first level of the judicial system. Located in remote places in rural areas. The competence of the Justice of the Peace on disputes related to ownership rights, is limited to cases under 30 Unidades de Referencia Procesal (Procedural Reference Unit; around EUR 3 700). Elected by rural, mostly Indigenous, communities for four years, with the possibility of prolongation for unlimited four-year periods. The person must be respected by the community and is not required to be a lawyer. Their decisions are made according to their local culture and knowledge with respect for the Constitution and the customs of the community. They depend on their respective Superior Court of Justice, which ratifies their nomination. They are oriented to conciliation cases (an ADR mechanism created to find an agreement between both parties and avoids the need to go to trial). The most frequent disputes are small alimony and child support payments, tenancy evictions, and land property demarcation. They apply equity criteria to adjudicate, not the national law. Their decisions can be appealed in front of the Justice of the Peace judge or the Specialised or Mixed Judge. In places where there are Justices of the Peace and Justices of the Peace judges with similar competences, the claimant can go to either one. It is not a mandatory jurisdiction to present a case before the Justice of the Peace Courts or other courts. Their function is not remunerated. |

Source: OECD elaboration with information provided on 16 October 2023 through Oficio. 610-2023-GP-GG-PJ, and from the Organic Law of the Judiciary and Law 29824, Peace Justice Law, and Peru Judicial Power, https://www.pj.gob.pe/wps/wcm/connect/CorteSupremaPJ/s_Corte_Suprema/as_Conocenos/historia.

At the national level, the judiciary is managed by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the Plenary Chamber of the Supreme Court, and the Executive Council of the Judiciary (Consejo Ejecutivo del Poder Judicial, CEPJ). The Supreme Court is the highest jurisdictional organ of Peru, and its competence extends across the country:

The Chief Justice presides over the entire judicial branch (poder judicial) (art. 144). The president is elected by the 25 members of the Judicial Power on a two-year rotating basis.

The Plenary Chamber of the Supreme Court (Sala Plena de la Corte Suprema) is the highest-level deliberating body of the judiciary. It is chaired by the president of the judiciary and the Supreme Court of Justice and comprises all the Tenured Supreme Judges. The Plenary Chamber of the Supreme Court approves the General Policy of the Judiciary and takes decisions on institutional matters, including the selection of the representatives of the judiciary on other bodies (Organic Law of the Judiciary, art. 80). The role of the Plenary Chamber is addressed in the law in very general terms with no clarity on its specific functions.

The CEPJ manages the Judicial Power. It assumes the technical-administrative direction of the judiciary and of the organisations indicated under the judiciary by law. It also formulates and executes the General Policy and the Development Plan of the Judiciary, as well as approves its Budget Project, and exercises disciplinary assessment and evaluation, among other functions (Organic Law of the Judiciary, art. 80). The governance and management of the judiciary will be addressed in detail in Chapter 4.

To simplify its structure and eliminate the duplication of functions of its organs, a new organisational structure of the judiciary came into effect on 1 December 2023, as approved by the Executive Council (Regulation of Organisation and Functions of the Judiciary, approved through Administrative Resolution 000341-2023-CE-PJ, from 18 August 2023). It also creates the Office of Access of Information and Data Analysis, which depends on the CEPJ.

At the regional level, Higher (Superior Courts) are based in each judicial district in Peru, which usually corresponds to the number of regions. There are currently 35 Superior Courts of Justice across the country. Each Superior Court comprises a certain number of chambers according to the procedural load it manages. The Specialised Courts, in turn, are subdivided according to their speciality (civil, criminal, labour, commercial). The courts that deal with issues of more than one speciality are known as Mixed Courts and are usually situated in local areas. The number of Specialised or Mixed Courts varies in each district, depending on the number of inhabitants. The Justices of the Peace Courts are created to administer justice in certain rural and urban areas with no or limited Specialised or Mixed Courts, and their scope of action is one, two or more districts. These courts also resolve appeals from the Justices of the Peace. As a multicultural country with important and diverse Indigenous and rural populations, ordinary justice co‑exists with various levels of Indigenous, peasant and community justice, reflecting these groups’ cultural values, forms of co-existence and social relations (Brandt, 2013). Indeed, it is estimated that there are more than 55 Indigenous communities in Peru, 51 of which are in the Amazon region and 4 in the Andes (Ministerio de Cultura, 2023[11]). The Justices of the Peace, who are not lawyers and are elected by the community, base their decisions on their best knowledge and beliefs in respect of the culture and customs of the community and the Constitution. There are 6 000 Justices of the Peace (jueces de paz) across the country.

In exercising its mandate to guarantee rights and access to justice to all populations, the judiciary also includes offices, commissions and programmes that have specialised functions to implement the general policy and plans of this branch, such as intercultural justice, gender-related justice, access to justice and environmental justice. In view of their relevance in securing access to justice, the following sections of this chapter provide an in-depth description of each of these bodies.

The National Office of Justice of Peace and Indigenous Justice

To promote intercultural justice, understood as a justice system in which ordinary justice co-exists with the various levels of Indigenous justice, the judiciary created in 2004 the National Office of Peace and Indigenous Justice (Oficina Nacional de Apoyo a la Justicia de Paz y a la Justicia Indigena, ONAJUP). The ONAJUP is part of the CEPJ and oversees the activities that the judiciary implements to develop and strengthen the Justicia de Paz (Peace Justice) (Regulation of Organisation and Functions of the Executive Council of the Judiciary, art. 30).

Even though the Constitution recognises the right of the native and peasant communities to exercise jurisdictional functions with the support of the peasant patrols (rondas campesinas) (art. 149) (Box 3.3), no law regulates or further develops this right and co-ordinates the co-existence of these two justice systems. Only a Plenary Agreement from 2009 recognises jurisdictional functions to the peasant patrols and establishes the limits of this special jurisdiction (Acuerdo Plenario No. 1-2009/CJ-116, from November 2009).

Box 3.3. Peasant patrols or rondas campesinas

The rondas campesinas or peasant patrols was the name that people gave to the type of communal defence organisation that emerged autonomously in Peru's rural and Indigenous areas in the mid-1970s as an informal response to the lack of justice services and state protection in rural areas. The members of the Andean communities use their own methods to administer justice and impose sanctions on people who threaten the security of their people. Among its original functions was to patrol trails, roads and pastures, as well as to end theft and rustling, which is one of the most condemned practices among Andean communities, as it has severely affected the livelihood of the populations. Although peasant patrols have existed for many years, they were only officially recognised in the Constitution of 1993. The 1993 Constitution granted peasants and native communities the right to perform jurisdictional functions within their territories with the support of patrols, in accordance with customary laws. This is apart from violations of fundamental rights (art.149). Their activity is regulated by Law No. 27908 and its regulations, which recognise their right to participate in the country’s political life, conciliation capacity and the general administration of justice.

Source: (Yrigoyen, 2002[12]).

In this regard, while the Law of Peace Justice (Law 29824) mentions co-ordination between the Justices of the Peace and such other community justice actors in peasant and native communities as Indigenous leaders and peasant patrols (rondas campesinas), the Law of the Rondas Campesinas (Law 27908) establishes that the ordinary and formal justice authorities should create co-ordination relationships with the peasant patrols, but it does not further develop this in detail.

Some protocols and regulations have been developed by the ONAJUP and the Commission on Intercultural Justice of the Judicial Power but in a very general manner, with no detail on the scope of Indigenous justice, on how to resolve conflicts between justice systems or on institutional co-ordination mechanisms that could contribute to resolving such conflicts (Co-ordination Protocol between Justice Systems [Protocolo de Coordinación entre Sistemas de Justicia]). According to these regulations, special justice systems have competence in the areas and topics that have traditionally fallen within their purview, based on their traditional, ancestral laws and systems. However, exercising their jurisdiction cannot contravene the fundamental rights of the Constitution or human rights.

Additional protocols have been created to ensure the use of an intercultural approach by justice system officials, the use of interpreters and translators of Indigenous languages in judicial proceedings, and co‑ordination between formal and intercultural justice.

According to the OECD interviews organised in the context of this project with stakeholders, it appears that there has been reluctance on the part of formal justice to recognise and enforce the decisions of intercultural justice, as sometimes the Justice of the Peace and the peasant patrols act outside the legal framework and not according to formal justice but following their cultural values, knowledge and ancestral practices. For example, this tension has made it difficult to co-ordinate the implementation of protection measures for victims of violence with the police. Also, even though the co-ordination protocol establishes the implementation of intercultural dialogue mechanisms, judges have shown resistance or lack of capacity to follow it. The same applies to the other justice institutions. A good practice has been implemented by the Superior Court of Justice of Cusco, which has created an inter-institutional co-ordination and dialogue mechanism on intercultural justice (Mesa Descentralizada de Coordinación de Justicia Intercultural de la Region Cusco), where the judiciary, the Public Ministry, the police, the Ombuds Office, the Ministry of Culture, universities, Justices of the Peace, peasant patrols, peasants’ communities and civil society organisations participate. However, this is not a practice replicated in all judicial districts and depends on the political will of the Superior Courts. On the other hand, the peasant patrols organise regional congresses in the different regions, where the different peasant patrols from the region and other regions participate, as well as civil society organisations, public institutions, the judiciary, the Women Emergency Centres, the Ministry of Culture, the police, the majors, the regional government, and others.

The relationship between the Justices of the Peace and the peasant patrols and other Indigenous justice actors can be uncertain and vary in each region of Peru depending on their presence or where these groups have more power in the communities, and more legitimacy regarding problem solving and as providers of intercultural access to justice. This makes it difficult to separate the roles and functions of both institutions and services, avoid overlap of functions and guarantee intercultural justice and the respect of both justice systems.

The Specialised Commissions

As mentioned in Chapter 2, to ensure a more inclusive justice system, the judiciary created four specialised commissions to promote the institution’s work in the key priority areas of gender justice, access to justice of vulnerable people, intercultural justice, and environmental justice.

The creation of these commissions and offices points to an awareness of the importance of a people-centred approach because it is predicated on prioritising people’s needs, problems and the protection of fundamental rights in the Peruvian context and reality, including for the most vulnerable groups. These specialised bodies aim to facilitate co-ordination on issues between different institutions to meet specific people’s needs and provide inclusive, appropriate and co-ordinated people-centred services. The progress achieved and the challenges of these commissions are assessed in Chapters 4, 5 and 6.

a) Commission on Gender Justice

The Constitution of Peru does not include gender-specific provisions that explicitly promote gender equality and women’s rights beyond the non-discrimination provisions relating to sex (not gender) or “any other distinguishing feature” (art. 2[2]) and to the representation of women in regional councils (art. 191). Other constitutions in OECD Member countries, including countries in the region, do include specific dispositions and constitutionalised rights that promote gender equality; these tend to illustrate the underlying values and beliefs of the nation and its commitment to achieving and protecting women’s rights, as mentioned in Chapter 2.

The role of the Commission on Gender Justice (Comisión de Justicia Género) is to promote the guarantee of equal access to justice for the population and to strengthen the judiciary’s work towards this objective through the establishment of policy on gender to be applied at all levels and organisational structures. It was created in 2016 to support the implementation of the 2015 Law to Prevent, Sanction and Eradicate Violence against Women and Family Members (Law 30364). The commission comprises a Supreme Court Judge, a Superior Court Judge and a Specialised Judge; a Consultive Council of two Superior Court Judges and two Specialised Judges; and a Technical Team.

Since 2016, the commission has implemented several initiatives and policies that have advanced gender equality in the judiciary in the resolution of cases related to gender-based violence, including: the implementation of legal-proceeding interpretation standards, which recognise the importance of including a gender approach in judicial reasoning and increasing the number of female judges; the creation of specialised jurisdictional bodies on violence against women and family members in 22 judicial districts; and the reinforcement of the work and preparation of Justices of the Peace to deal with cases of violence against women and family members.

b) Commission on Access to Justice of Vulnerable People

To promote access to justice on the part of vulnerable populations, the judiciary created in 2017 the Permanent Commission for Access to Justice of Vulnerable People and Justice in Your Community (Comisión Permanente de Acceso a la Justicia de Personas en condición de Vulnerabilidad y Justicia en tu Comunidad, CPAJPCV). This commission oversees the implementation of relevant treaties that Peru has ratified, such as the Brasilia Rules on Access to Justice for Vulnerable People (approved in March 2008 by the XIV Ibero-American Judicial Summit, which Peru ratified for implementation in 2010). It promotes access to justice for vulnerable groups through the implementation of the 2016-2021 National Plan for Access to Justice of Vulnerable Persons of the Judiciary (approved by Administrative Resolution No. 090-2016-CE-PJ) (Poder Judicial del Perú, 2022[13]) and the draft of the 2022-2030 National Plan, which has not yet been approved. The commission comprises its president, two Supreme Court judges and two Specialised Court Judges.

Since 2017, the commission has implemented a series of services and trainings to increase and ameliorate access to justice for vulnerable people. Some of these initiatives include: the creation of protocols, guidelines and capacity-building activities for judicial personnel when dealing with cases with vulnerable populations (including children and people with disabilities, among others); capacity building for judges and judicial personnel on mobile justice services (justicia itinerante), which travel to remote places where vulnerable populations are located to provide justice services; legal justice fairs and campaigns (Llapanchikpaq Justicia), which take justice services from different justice institutions to remote areas to provide the population with information related to their fundamental rights; a judicial warning system (Sistema de alerta judicial), which identifies people in vulnerable conditions so their legal process can be monitored more closely (especially for elderly people); the creation of the accreditation of legal counsellors (orientadoras judiciales), who are leaders within their communities who have been trained to guide people on issues related to gender-based and inter-family violence.

c) Commission on Intercultural Justice

As part of the judiciary’s efforts to promote the rights of the Indigenous, native and peasant communities and the peasant patrols (rondas campesinas) and their cultural values, practices, and ways of co‑existence, the Commission on Intercultural Justice (Comisión de Justicia Intercultural) was created to implement a concrete roadmap for improving intercultural justice in Peru (Administrative Resolution 499-2012-P-PJ, from 2012). The roadmap’s main objective was to promote the communication and co‑ordination between the different justice systems (including the creation of the ONAJUP, as seen above) and develop intercultural training, research and capacity-building activities on the different intercultural justice systems available in the country.

To increase the co-ordination between formal and intercultural justice, the commission has implemented several training and capacity-building activities for judges and other justice public servants on existing protocols and regulations to promote its recognition and acceptance for effective co-ordination and access to justice for all. The same approach has been taken with the Justices of the Peace, the peasant patrols and other social leaders to train them on human rights and the formal justice system. Other institutions, such as the Ombuds Office, the Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), have also trained the peasant patrols and other social leaders on formal justice and fundamental rights.

d) Commission on Environmental Governance

The Constitution of Peru includes a general provision on the fundamental right to a balanced and appropriate environment (art. 2[22]). The right to environmental justice is established by the General Law of the Environment (Law 28611 from 15 October 2005), which recognises the principle of environmental responsibility (art. 9) and the principle of environmental governance (art. 11).

The existent judicial mechanisms for environmental justice are provided through existing procedural laws. Environmental justice is enforced through ordinary judicial mechanisms (contentious administrative, criminal, and civil procedures) and constitutional judicial mechanisms (habeas data, the writ of mandamus, the wright of unconstitutionality, popular action), but through ADR and amparo procedures (see Chapter 4 for further description of these mechanisms). In addition, there are Public Prosecutor’s Offices specialised in environmental matters (Fiscalías Especializadas en Materia Ambiental, FEMA), an environmental specialised court in the city of Puerto Maldonado, and courts with environmental competence in ten additional judicial districts.

As part of the justice reform efforts and modernising the judiciary, the Plenary Chamber created the Commission on Environmental Governance (Comisión Nacional de Gestión Ambiental) in 2016. Since then, the first environmental specialised court was established in Puerto Maldonado in 2018, and ten other criminal courts with environmental competences have been created across the country. Eco-efficiency committees have been created in the Superior Courts, and guidelines on eco-efficiency measures in the judiciary and capacity-building activities have been created for judges and justice personnel on environmental-related crimes.

3.3.2. The Academy of the Magistracy

The Academy of the Magistracy (Academia de la Magistratura, AMAG), responsible for the education and training of judges and prosecutors at all levels, benefits from administrative, academic and economic autonomy from the judiciary (Constitution, art. 151; Law 26335, art. 1). The AMAG is responsible for developing an integrated and continuous system of capacity building for judges (including their certification and accreditation) and prosecutors of the Public Ministry (Constitution, art. 151). Training and capacity building of judges is addressed in Chapter 4.

The AMAG co-operates with the National Board of Justice (Junta Nacional de Justicia, JNJ) (which will be described in detail in the next section) on the performance appraisal or evaluation process of judges and public prosecutors that it carries out every three and a half years, according to which the JNJ may ask the judge or prosecutor to participate in a training programme from AMAG. To do so, AMAG and the JNJ design and co-ordinate evaluation processes to pursue these capacity-building activities (Regulation of Judges and Prosecutors Performance Appraisal, approved by Resolution No. 515-2022-JNJ).

Several additional institutions also provide training and continuing education for their staff on gender, violence against women, and Indigenous and multicultural justice, among others, including the judiciary for its judges through its specialised commissions and the Public Ministry for its public prosecutors. AMAG is the institution in charge of training and upskilling judges and public prosecutors (Organic Law of the Academy of the Magistracy, art. 2). This fragmentation in capacity building and overlap of mandates create various levels of capacities of legal professionals, as the training programmes depend on the availability of resources in these institutions, on the institution’s specialisation and the priority given to training and upskilling. This situation is not conducive to fostering an institutionalised, integrated, co-ordinated, professionalised and sustainable system of continuing education for judges, prosecutors and other personnel involved in the administration of justice.

3.4. Constitutionally autonomous institutions within Peru’s justice system

3.4.1. The Constitutional Court

In addition to the judicial branch and situated outside its structure, the Constitutional Court, an autonomous and independent body, exercises jurisdictional functions over the justice system by overseeing adherence to the Constitution (art. 201). The Constitutional Court consists of seven members (not necessarily professional judges) who are elected for five-year terms by Congress (with no immediate term renewal). The protection of constitutional rights can be invoked before the courts of the judicial branch and the Constitutional Court. Peru has adopted a mix of concentrated and dispersed approaches to constitutional review, as this function is shared between the Constitutional Court and the judiciary (Box 3.4).

Box 3.4. Models of constitutionality assessment: Parliamentary, continental and diffuse

Three models of constitutionality assessment frame the discussion around the constitutional review:

Parliamentary sovereignty model: According to this model, judicial review of constitutionality is either forbidden (art. 120, Constitution of the Netherlands) or limited (Canada, Finland, New Zealand, Switzerland and the United Kingdom). In some countries, the legislature stands on an equal or superior footing to the courts regarding constitutionality review, as in the “new Commonwealth model of constitutionalism”: Canada, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. The reasoning is that while courts play a significant role in protecting fundamental rights, they should not be the only institutions capable of interpreting those rights. This way, the articulation and enforcement of constitutional norms, as well as the responsibility for implementing constitutional values, are vested in parliamentary sovereignty. While courts interpret and enforce the constitution, the legislature decides and determines what will be law.

European continental (or Kelsenian-Austrian) concentrated and abstract model: The centralised Kelsenian system is based on two pillars: 1) it concentrates the power of constitutional review in one judicial body, typically a Constitutional Court; 2) it situates that court outside the structure of the judicial branch. Because of the hierarchy of laws, constitutional judicial review is seen as incompatible with the work of an ordinary court. The abstract review, as employed in France, involves political institutions requesting the court to provide an interpretation of the text of the constitution from a real, concrete dispute. The concrete review, as in Germany and Spain, asks the court to deal with a specific case in which a constitutional question is raised. Notwithstanding, there are different approaches by which the separation between the constitutional court and the judiciary has been blurred, as the Constitutional Court can interfere with judicial decisions and participate in the resolution of individual cases, creating conflicts of competence between both bodies (such as amparo in Spain or tutela in Colombia).

Diffuse or dispersed judicial review model: Also called the American model, as it originated from case law of the US Supreme Court (Madbury v. Madison). By this model, judicial constitutional review can be dealt with by any judge or court and under ordinary court proceedings whereby the Supreme or High Court provides uniformity of jurisdiction through the appeals system. Each judge can apply the Constitution in their own way, and the questioned law will not be applied in the case nor subsequent cases, but it is not expelled from the legal system. Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Ireland, Norway, Sweden, the United States and many Latin American countries have adopted this system. Others, such as Colombia, Mexico and Peru, have a mixed system of concrete and diffuse constitutional review.

Source: (OECD, 2022[14]), Constitutions in OECD Countries: A Comparative Study: Background Report in the Context of Chile’s Constitutional Process, https://doi.org/10.1787/ccb3ca1b-en.

The Constitutional Court is responsible for hearing and adjudicating cases in final instance (constitutional matters are first heard in ordinary courts), including those that deny petitions of cases related to civil action against the state; the protection of a person’s freedom from illegal detention; privacy and personal data and the right to access to information of public importance; for cases of violations of individual rights that fall outside the scope of the two previous procedures or cases of authorities or public officials who question their obedience to a legal rule or administrative act.

The Constitutional Court is responsible for passing on judicially, in first instance and without appeal, writs of unconstitutionality concerning laws and regulations that might contravene the Constitution and to hear jurisdictional disputes concerning a public institution that may have exceeded the powers assigned to it under the Constitution, in accordance with the law (Constitution, art. 202). As mentioned above, the process of constitutional review in Peru establishes that the Constitutional Court has the final word on constitutional matters and that judges must interpret and apply the law according to the Constitution and the jurisprudence of the Constitutional Court (art. VI Preliminary Title of the Constitutional Procedures Code).

In some cases, lower court judges have set aside judicial interpretations made by the Constitutional Court (Landa Arroyo, 2006). This has led to the Constitutional Court issuing final judgements that declared these lower court decisions invalid and, in the process, establishing as final and binding its own decisions on all other organs of the state, including the ordinary courts. This means that, in effect, lower courts cannot contradict Constitutional Court decisions and jurisprudence. This has created considerable friction with the lower courts, as some consider that the Constitutional Court has been heavy-handed and has acted in a disproportionate way that could hamper the independence of lower court judges (Espinosa-Saldaña Barrera, 2007[15]; Malpartida Castillo, 2011[16]).

While constitutional unity is necessary, co-ordination mechanisms to discuss and achieve basic consensus on these topics and the willingness of both institutions to work together have been lacking. The CRSJ could be a mechanism that brings both institutions closer. However, in July 2019, the Constitutional Court decided not to participate in it, declaring that it was “autonomous, independent and responsible for the control of the Constitution” (Tribunal Constitucional, 2019[17]).

3.4.2. The National Board of Justice

The JNJ (also called the Junta) is an autonomous institution that oversees the human resource management of the judiciary and the prosecutorial service and is responsible for the selection, appointment, evaluation or performance appraisal and disciplinary actions of judges and prosecutors (Constitution, art. 154; Law 30916, art. 1).

The Junta was established by the Judiciary Reform Commission to replace the National Council of the Magistrature (Consejo Nacional de la Magistratura, CNM) in response to the Callao corruption case within the Peruvian judicial system. More specifically, former President Martin Vizcarra (2018‑20) established a commission with a core mandate to create a comprehensive reform of the justice system, which included the reform of the CNM as one of its first measures (see Chapter 2). The Junta counts seven members; these are selected by a Special Commission composed of the Ombudsperson, the president of the judiciary, the Public Prosecutor, the president of the Constitutional Court, the Comptroller General, a dean from a public university and a dean from a private university, through open public competition for a single non-renewable five-year term. The selection criteria are detailed in the Constitution (arts. 155 and 156) and the Organic Law of the National Board of Justice (Law 30916 from February 2019) and include professional merit and an evaluation of professional competency and knowledge, as assessed by the ad hoc selection special commission. Congress can remove members for gross misconduct before the expiry of the term (Organic Law of the National Board of Justice, art. 6).

The Junta is responsible for the selection and appointment of judges and prosecutors at all levels, except for Justices of the Peace, who are chosen by popular election, following a public competitive examination and personal evaluation (Organic Law of the National Board of Justice, arts. 28-34 and 51[b]). It ratifies whether judges and prosecutors can continue in their positions every seven years and executes their partial performance evaluation or performance appraisal jointly with AMAG every three and a half years. Those not ratified may not re-enter the judiciary or the Public Ministry (Organic Law of the JNJ, arts. 35-40). It is also incumbent upon the JNJ to apply sanctions to judges and prosecutors, which include dismissal/removal, reprimand or suspension (Organic Law of the JNJ, arts. 2 and 42) (see Chapter 4).

Since January 2020, when it launched operations, the Junta has implemented several measures and initiatives, including the restructuring of the institution; the amendment of its regulations regarding its functions, procedures and competence; the revision of appointments, ratifications, evaluations and disciplinary proceedings executed by the former CNM; and the appointment of tenured judges and prosecutors, to reduce the number of provisional judges.

The functions of the Junta require that it communicate constantly with other justice institutions, such as the judiciary, the Public Ministry, and AMAG, to contribute to the promotion of effective justice services.

3.4.3. The Public Ministry or Public Prosecutor’s Office

The Public Ministry, also officially called the Prosecutor’s Office of Peru, is an autonomous constitutional body. It has a representative and independent role in defending those who have seen their rights affected within the national legal system.

The Public Ministry is directed by the National/Public Prosecutor, who is elected by the Board of Supreme Prosecutors for a three-year term and may be re-elected for two additional years (Constitution, art. 158). The Public Ministry or Public Prosecutor’s Office (Fiscalía) is headed by the Public Prosecutor (Fiscal de la Nación), which is the main institution in charge of investigating and prosecuting crimes and protecting the interests of society (Constitution, art. 159). As the hierarchical structure of the judiciary, this body consists of the Public Prosecutor, the Supreme Prosecutors (Fiscales Supremos), the Superior Prosecutors (Fiscales Superiores), the Provincial Prosecutors (Fiscales Provinciales), the Deputy Prosecutors (Fiscales Adjuntos) and the Boards of Prosecutors (Juntas de Fiscales) (Organic Law of the Public Ministry, art. 36; Prosecutors’ Career Law, art. 3).

The Public Ministry has Public Prosecutor’s Offices specialised in violence against women and family members, environmental matters, corruption crimes, organised crimes, money laundering, illicit drug trafficking, human trafficking, fiscal/tax crimes and customs offences.

As seen in Chapter 2, the new Criminal Procedures Code (in force since July 2006 and implemented at the national level in 2021) strengthens the role of the Public Ministry and its prosecutors in criminal proceedings. It places this institution squarely in charge of criminal proceedings as it is now the prosecutor assigned the mandate to conduct criminal investigations (art. 60). Thus, the prosecutor conducts the preparatory investigation, decides the strategy of the investigation and intervenes in all stages of the process (art. 61). To conduct the investigation, the Public Ministry may require the intervention and support of the police (art. 330); it formalises and regulates the co-ordination mechanisms with the police as an institution (art. 69).

The Public Ministry is one of the justice institutions that participates in more inter-institutional co-ordination spaces, which promotes joint work and co-ordination with other justice institutions on topics that require their participation and agreements (e.g. violence against women, the implementation of the new Criminal Procedures Code and their co-ordination with the police in criminal cases). Furthermore, bilateral co‑ordination with other institutions, such as the police, regarding the investigation of cases and specialised crimes has also been implemented, fostering constant and mutual communication, joint work, protocols delimiting responsibilities, articulation and co-ordination, and a better assessment of these issues. In these co-ordination spaces, authorities from the Public Prosecutor's Office and the police participate with decision-making power and lead specialised teams focused on particular crimes (see the section on the national police).

This becomes especially evident in the co-ordination and planning between the Public Ministry and the judiciary on the provision of justice services where, for instance, more Public Prosecutor’s Offices specialised in violence against women were created, thus generating more cases than the courts could handle (and without a corresponding increase in the number of courts needed to hear them). This has impacted the ability to resolve legal needs in an effective and timely manner. The same problem exists between the Public Ministry and the judiciary as more Public Prosecutor’s Offices on environmental issues were created than existing courts to see the cases, which generated a case load that the existing courts are unable to manage. The non-participation of the judiciary in the above-mentioned co-ordination mechanisms may explain part of the issue.

3.4.4. The Ombuds Office

The Ombuds Office (Defensoría del Pueblo) is responsible for defending people’s fundamental constitutional rights. It oversees the state’s administration and performance of its duties and supervises the delivery of public services to citizens (Constitution, art. 162). It is an autonomous body headed by the Ombudsperson (Defensor del Pueblo), whom Congress elects for a five-year term (Constitution, art. 161). Its efficiency depends on the prestige and good image of the Ombuds Office and its advocacy work, as its decisions and recommendations are not binding, and it cannot sanction institutions for non-compliance.

The Ombuds Office is entitled to intervene in constitutional processes; prepares reports on topics within its sphere of competence, including an annual report to Congress; investigates acts and resolutions of the public administration; presents draft legislation before Congress; promotes the signing and ratification of, and accession to, international human rights treaties; and initiates or participates in administrative proceedings in representing a person or group of people for the defence of constitutional and fundamental rights (Organic Law of the Ombuds Office, art. 9) (see Chapters 3 and 4).

This institution organises its work around strategic and thematic areas: public management; human rights and people with disabilities; the environment, public services, and Indigenous populations; constitutional matters; women’s rights; children and adolescents; the fight against corruption, transparency, and the efficiency of the state; and prevention of social conflicts and governability.

Its functions include constant communication with public institutions, including for the provision of recommendations and their follow-up and implementation. The Ombuds Office also co-ordinates with other justice institutions, including the judiciary and the Public Ministry, and supports the provision of mobile services through joint fairs and campaigns.

It has 40 offices at the national level and in all regions and departments of the country. It visits communities and populations in remote places through mobile campaigns, collecting people’s complaints on public administration and public services issues, advising them on their problems or concerns, and building capacity on people’s fundamental rights. It is important to note that a lack of financial resources limits its work in the regions and its capacity to reach local populations in the regions.

This public institution also intervenes in national social conflicts as a mediator, participating in dialogue spaces and providing early warnings and recommendations to the government. This and its advocacy work on protecting and promoting people’s rights has allowed them to have good relationships with diverse groups of vulnerable populations and has strengthened its powers of persuasion with the government (see Chapter 6).

3.5. The executive branch and Peru’s justice system

3.5.1. The Ministry of Justice and Human Rights

As part of the executive branch, the role of the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights (Ministerio de Justicia y Derechos Humanos, MINJUSDH) is, among other things, to promote and disseminate human rights and access to justice, with emphasis on vulnerable populations; formulate policies and proposals of legislation on matters within its jurisdiction; provide the judicial defence of the state and oversee the penitentiary policy (Law of Organisation and Functions of the MINJUSDH, arts. 4-5).

It is headed by a minister, who is supported by a Vice-Ministry of Justice (art. 11) and a Vice-Ministry of Justice and Human Rights and Access to Justice (arts. 7 and 12). The latter is responsible for people’s access to justice, which is promoted through public defence services and ADR mechanisms (see Box 3.5).

Box 3.5. Public defence services and ADR mechanisms

The public defence service is provided by 2 057 public defenders throughout Peru and guarantees the following services: public criminal defence (counsel and sponsorship); the defence of victims (counsel and sponsorship); legal assistance (counsel and sponsorship in civil law and family, labour, administrative law matters) (Public Defence Service Law, art. 6). It also provides other multidisciplinary services, including experts (peritos), social workers and health services. This service is provided in the 34 Public Defence District Directions (Direcciones Distritales de Defensa Pública), located in each one of the judicial districts, and in another 390 offices at the national level, including the 40 free legal assistance centres (Centros de Asistencia Legal Gratuita, ALEGRAs) and 6 mega ALEGRAs. However, as mentioned by the MINJUSDH and other public institutions, the number of public defenders is insufficient considering the number of cases that the public defence service receives [see also (Defensoria del Pueblo, 2022[18])]. The ALEGRAs offer public defence for victims, legal assistance and extrajudicial conciliation services, with 46 at the national level. The mega ALEGRAs offer the same services as the ALEGRAs, as well as multidisciplinary services; there are five in different judicial districts (Lima, Lima East, Callao, Arequipa and Ayacucho). The Fono Alegra 1884 is a free legal assistance line for poor and vulnerable people. Their assistance is mainly related to family matters (child support, alimony, custody, visiting arrangements, paternity recognition, intestate succession, among others) and domestic violence.

Through public criminal defence services, it provides free legal advice and assistance to people who have been investigated, denounced, detained, accused or sentenced in criminal proceedings, as well as to adolescents in conflict with the law, through sponsorships, consultations and free investigations. The public criminal defence and defence of victims’ services are also provided in the Flagrancy Units (Unidades de Flagrancia), which are created to provide fast and co-ordinated services from the police (the detention, custody and investigations), the Public Ministry (leads the investigation, the accusation and forensic medicine), the MINJUSDH (public defence) and the judiciary (the hearing, judgement and the decision) in cases of flagrante delicto (Legislative Decree 1194). There are six functioning Flagrancy Units, four of which are in Lima.

Alternative dispute resolution (ADR) mechanisms refer to the diverse ways people can resolve disputes without going to trial and involve an impartial third party who assists the parties in reaching a resolution satisfactory to both sides. Various ADR methods are used, including conciliation, mediation and arbitration. The ADR process is assessed in Chapter 5. While the Constitution of Peru recognises arbitration as a mechanism for access to justice, constitutions of other Latin American countries, including Mexico, recognise other ADR mechanisms as well, such as conciliation and mediation, defending a broader notion of access to justice and the promotion of these mechanisms (Nylund, 2014[19]). The MINJUSDH, under the Directorate of Extra-judicial Conciliation and Alternative Dispute Resolution Mechanisms, is responsible for implementing ADR mechanisms, which are free of charge to vulnerable sectors of the population, as is the public defence service. The public ADR mechanisms include conciliation, arbitration and popular arbitration and mediation:

Extrajudicial conciliation is conducted by a conciliator. In some civil cases, it is mandatory to start a court proceeding (Conciliation Law, arts. 6 and 9), but disputes relating to the commission of crimes or offences cannot be conciliated. The Directorate authorises and oversees the issuing of education and training courses for conciliators. A conciliation decision, which reflects the will of the parties, is not a jurisdictional act (Conciliation Law, art. 4) but is enforceable through the corresponding enforcement proceeding (Civil Procedures Code, art. 688). The MINJUSDH conducts virtual joint conciliations called Conciliatión. The General Directorate of Public Defence of MINJUSDH manages around 2 821 private conciliation centres, 93 free conciliation centres (including the 40 ALEGRAs and 6 mega ALEGRAs) and 95 extrajudicial conciliators at the national level. The conciliation services can be virtual or in person. The most common cases relate to family issues, especially alimony. Justices of the peace and lawyers’ Justices of the Peace judges can also function as conciliators (Conciliation Law, arts. 33-34).

Mediation is developing as an alternative to prosecution, especially for youth criminality. Since 2018, the MINJUSDH has provided a diversion mechanism from prosecution based on the principle of opportunity and reaching a reparation agreement with the victim of the crime.

Through arbitration, parties decide to solve their conflicts voluntarily, submitting to the decision of an arbitrator or expert tribunal in the matter of the dispute. Arbitration awards are final (Arbitration Legislative Decree, arts. 62-65) and, as in the case of conciliation, decisions are binding and enforceable through an enforcement proceeding (Civil Procedures Code, art. 688). The Directorate of Extra-judicial Conciliation and Alternative Dispute Resolution Mechanisms of the MINJUSDH exercises arbitration roles through the Popular Arbitration Centre (Arbitra Perú) (Supreme Decree 016-2008-JUS), located in Lima, which counts 179 arbitrators, who only hold virtual hearings. The Directorate oversees the National Registry of Arbitrators and Arbitration Centres (Registro Nacional de Arbitros y de Centros de Arbitraje, RENACE) (see Chapters 5 and 6).

The State Attorney’s Office (Procuraduría General del Estado), attached to the MINJUSDH and in existence since 2020, is responsible for “the defence of the state’s interests” (Constitution, art. 47). For this purpose, it, among other things, promotes and guarantees the defence and judicial representation of the state; promotes conflict resolution; and works together with co-operation mechanisms to locate and recover goods, instruments and earnings generated by illegal activities (Legislative Decree 1326, art. 12). The State Attorney is appointed by the President and proposed by the Minister of Justice and Human Rights. There are also national, regional and municipal Procuradurías Públicas, which are the judicial defence organs of the public institutions (art. 25). The Specialised Procuradurías are assigned special crime cases, including illicit drug trafficking, terrorism, money laundering, crimes against public order, corruption, environmental crimes, and in constitutional matters, others that might be created. The Ad Hoc Procuradurías are created for specific cases and are temporary (art. 25). The Lava Jato Ad Hoc Procuraduría has begun prosecuting many Peruvian politicians and officials at the highest levels involved in cases related to the Brazilian construction company Odebrecht, many of which are related to foreign bribery. It has investigated and charged several senior public officials for corruption, including five former presidents, cases that are still ongoing. It has also promoted effective collaboration and reparation agreements for cases it has conducted (OECD, 2021[20]).

It is important to note that other institutions provide public defence and ADR/mediation services. Lawyers from the State Attorney’s Office, part of the MINJUSDH, also provide public defence and representation of the state (Constitution, art. 47) and the executive in court. The Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations (Ministerio de la Mujer y Poblaciones Vulnerables, MIMP) provides legal advice and judicial defence services to victims of violence against women in the Women Emergency Centres (Centros de Emergencia Mujer, CEM). The Public Ministry, through the Central Unit of Protection and Assistance of Victims and Witnesses (Unidad Central de Protección y Asistencia a Víctimas y Testigos, UDAVIT) and its district units, provides multidisciplinary assistance to victims and witnesses, including of violence against women, as part of the implementation of the Protection and Assistance of Victims and Witnesses Program. Private arbitration, which does not depend on the MINJUSDH, exists and is financed by its users.

Overall, co-ordination across institutions providing conciliation services regarding both public defence and ADR/mediation appears limited. There are no co-ordination mechanisms on ADR mechanisms, including between the judiciary and the MINJUSDH; this is problematic given that the judiciary ends up enforcing conciliation decisions or allowing the start of a court proceeding when the conciliation was not successful. There also appears to be limited co-ordination capacity between the MINJUSDH and the other institutions in the executive and in the justice system that offer public defence services. This raises important issues relating to the efficiency with which public human and financial resources are expended on public defence services, as well as to the level and quality of the public defence service being delivered to the people who need these services the most (this is illustrated most clearly in the next section on the services provided to battered women – women victims of violence). Finally, the small number of public defenders does not guarantee effective access to justice for vulnerable populations.

3.5.2. The national police

The national police (Policía Nacional del Perú, PNP), which falls under the purview of the Ministry of the Interior (Ministerio del Interior), is considered part of the justice system given its criminal investigation functions:

The PNP is the institution that receives the most citizen complaints through police stations.

The PNP guarantees internal order, public order and public safety; guarantees law enforcement and the protection of public and private property; prevents and investigates crimes and offences; and fights against crime and organised crime (Law of the PNP, art. 3).

It has directorates specialised in specific crimes, including environmental, drug trafficking, terrorism, money laundering, human and migrant trafficking, corruption, tax/fiscal, order and security, state security, people security, transit and transport, and tourism, among others.

The role of the police in investigating a crime is regulated by the Criminal Procedures Code. The police are obliged to support the Public Ministry in undertaking preparatory investigations. The police shall, even on its own initiative, become aware of the crimes, inform the Public Prosecutor, perform urgent proceedings to prevent consequences, identify the perpetrators and secure the evidence (Criminal Procedures Code, Section IV, Chapter II Title I).

Because of the role of the police in the investigation of crimes, the protection of people against illegal acts and their role as first responders to a crime scene, this institution should co-ordinate with the other public institutions that also have a complementing role to play in these topics, which often involve multiple jurisdictions and a range of players. Co-ordination spaces have been identified between the police and other public institutions, such as the judiciary, the Public Ministry, the MINJUSDH and MIMP, on topics related to violence against women and family members (see below on the National System of Justice for the Prevention, Sanction and Eradication of Violence against Women and Family Members, SNEJ), the implementation of the new Criminal Procedures Code, including the investigation of cases.

On the latter, co-ordination between both institutions is important for the effective investigation of crimes and access to justice, as well as coherence between the institutional mandates and arrangements of both entities to deal effectively with the challenges of investigating different crimes. In this regard, it is important to mention that the Public Ministry and the police have offices specialising in the same crimes, except violence against women, which provides better capacity for both institutions to co-ordinate, plan, and work together on investigating crimes. Since violence against women is considered a priority issue by the government, a specialised office or directorate focused on this topic could promote effective co-ordination and access to justice for gender-based violence cases. There has been co-ordination on capacity building and training and joint development of protocols on case analysis by MIMP and the police.

A significant challenge facing the police, impacting effective duty performance, is their relationship with citizens and communities. This is largely due to perceived corruption and mistrust, especially in rural and Indigenous areas. Indeed, 76% of the population is said to mistrust the police (INEI, 2022[21]). Lack of trust can impact the effectiveness of public policies to promote access to justice and security for people. The PNP highlighted language barriers as one of the main challenges they face when consulting with the population and doing their work properly, as most officers do not speak native languages, which not only is an obstacle to people’s access to justice but hampers building trusting relationships with the communities they serve.

3.5.3. The Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations and the AURORA Program

MIMP is considered part of the justice system as justice service provider through its National Program for the Prevention and Eradication of Violence against Women and Family Members (Programa Nacional para la Prevención y Erradicación de la Violencia contra las Mujeres e Integrantes del Grupo Familiar, AURORA) (Supreme Decree 018-2019-MIMP). Through this programme, it provides justice services and other specialised services to women and other family members victims of violence (see Box 3.6).

Box 3.6. Services provided by the AURORA Program

The AURORA Program provides the following services: