Several competent education authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) have been moving away from a compliance-oriented approach to school quality assurance towards procedures that emphasise the development of learning and teaching practices. Despite these efforts, most competent education authorities covered by this review do not conduct external evaluations or self-evaluations of schools. Many also lack consistent standards or implementation protocols for evaluating school performance, which makes it difficult to form reliable judgements and determine where and how best to provide schools with support. This chapter puts forward a set of practical recommendations that aim to accelerate the development of improvement-oriented evaluation practices in BiH school systems, while making the most of limited resources and capacity

OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Bosnia and Herzegovina

4. Strengthening evaluation capacity to support the most at-risk schools and build school leadership

Abstract

Introduction

In recent years, several competent education authorities in Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) have followed the direction of European education systems in moving away from an administrative, compliance-oriented approach to school quality assurance to introduce more evaluation-based procedures focused on developing instructional practices. For example, Republika Srpska introduced external school evaluation and school self-evaluation in 2017/18, and West Herzegovina Canton now requires schools to conduct self-evaluations. Importantly, both have established quality standards that identify the practices schools should employ to improve student learning and development. However, despite efforts to introduce school evaluations more widely, most authorities do not conduct external school evaluations or self-evaluations. Instead, general school supervisions are more common. While these school supervisions go beyond compliance checks and attempt to provide a perspective on the quality of teaching and learning practices, the procedures examined as part of this review were not based on consistent standards or implementation protocols. This makes it hard for competent education authorities to make reliable judgements about school performance and determine where and how to provide support.

All education authorities in BiH also face considerable resource and capacity constraints, which further hinder school monitoring or evaluation. These challenges have been compounded during the COVID‑19 crisis. It is therefore particularly important that authorities use available resources pragmatically and prioritise the evaluation and support of schools that are most at-risk. This chapter puts forward a set of practical recommendations to accelerate the development of improvement-oriented evaluation practices in ways that make the most of limited resources. Specifically, all competent education authorities should develop and use consistent school quality indicators to identify at-risk schools and target support initiatives. This in turn requires authorities to build the capacity of pedagogical institutes or their equivalents to provide support to schools. The chapter also examines how strengthened self-evaluation procedures, enriched with support from BiH-level bodies, can be leveraged to help schools drive their own improvement.

School governance and management in Bosnia and Herzegovina

School leadership in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Education actors in BiH have made efforts to improve the quality of school governance and management over the past 20 years. For example, in 2002, they committed to making school governance and management more modern, democratic and inclusive to be more consistent with EU standards (BiH, 2002[1]). This led to new appointment processes for school principals and the establishment of school parents’ councils and student councils in the 2003 Framework Law on Primary and Secondary Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina. However, the school principal role in BiH has remained influenced by politics and focused on administrative tasks rather than instructional leadership. To address this, some competent education authorities are introducing measures to professionalise the role, such as standards of school leadership and principal appraisal processes. However, for the most part, these are in the early stages of development and, as with efforts to develop the teaching profession, they are hindered by a lack of resources and capacity in BiH’s education systems.

Despite efforts, school leader appointments remain influenced by politics

Each competent education authority in BiH has their own requirements for becoming a school principal. Some are similar to those in other European countries, including the need to have at least five years of experience as a teacher or educator (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2020[2]). This is positive because it ensures that principals are familiar with the school environment. However, while some cantons in this review plan to develop initial training for principals, this is not a current requirement for the role. By contrast, a number of OECD countries mandate training for new principals, either before or upon taking up the position, to ensure that they have some preparation in school development and management (Pont, Nusche and Moorman, 2008[3]). Furthermore, politics influence the hiring of school leaders in BiH, despite efforts over the years to make the process more objective and meritocratic. While school boards commonly initiate the recruitment process and declare the winner, depending on the jurisdiction, the competent education authority either directly selects or approves the candidate or can influence decisions of school board members (Gabršček, 2016[4]). The lack of initial training and influence of politics mean that principals in BiH do not always have the competences they need to improve teaching and learning in their schools.

School leadership focuses on administrative responsibilities

The school leadership role is focused more on administrative tasks than instructional leadership (e.g. school self-evaluation and advising teachers on the quality of instruction), which is essential to school improvement. School principals in BiH are responsible for the school’s day-to-day management and leading pedagogical activities, in line with the Framework Law on Primary and Secondary Education in BiH. However, research has found that, in some administrative units, they tend to focus more on the former (World Bank, 2019[5]). West Herzegovina Canton plans to develop professional standards setting out what principals should know and be able to do, but otherwise, the authorities covered in this review do not have standards for school leadership. In OECD member and partner countries, these standards commonly inform principal recruitment, training and appraisal.

School leaders in BiH are obliged to participate in continuous professional development, but there are no requirements regarding the frequency or duration of this training (Gabršček, 2016[4]). There are some positive examples of principal networking, notably in Republika Srpska and Brčko District. However, as with teachers’ professional learning (Chapter 3), the pedagogical institutes or their equivalents that are responsible for organising or delivering training to principals, lack the resources to provide them with systematic learning opportunities. In 2020, the Council of Ministers of BiH identified this lack of professional learning for school principals as a gap and called for new programmes on essential topics such as school development and pedagogical leadership (Council of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 2020[6]).

None of the competent education authorities are conducting appraisals of school leaders, although some processes have been developed or proposed

Unlike just over half of OECD countries (OECD, 2015[7]), the competent education authorities in this review do not conduct appraisals of school principals’ performance to support leadership development and accountability. While Republika Srpska has developed an appraisal process, representatives of the Republic Pedagogical Institute of Republika Srpska informed the review team that it is not being implemented because the relevant rulebook is out of date. West Herzegovina Canton is planning to develop a standards-based principal appraisal process in the future. A good feature of Republika Srpska’s former process was that principals’ performance was assessed regularly (at least once every two years) against consistent criteria, namely: i) management of the schooling process; ii) planning and organisation of the work of the school; iii) co‑operation with the local community and parents; and iv) financial and administrative management. However, the minister of the competent education authority conducted the appraisal, whereas in other countries, appraisers are commonly required to have experience in school contexts and sometimes to be completely independent to ensure that their judgements are objective (ibid). Furthermore, it is not clear whether Republika Srpska’s appraisals were designed to produce constructive feedback or identify professional learning activities to support school leaders’ development. These outcomes are critical to building principals’ competences (Pont, Nusche and Moorman, 2008[3]).

Other forms of assessing school leadership exist in some administrative units. Positively, new school evaluation processes in Republika Srpska and West Herzegovina Canton (school self-evaluation only) assess the management of the school, which could provide information to help principals refine their practices (see below). On the other hand, school boards in BiH commonly conduct assessments of principals’ performance to grant salary bonuses, but these are generally informal (Gabršček, 2016[4]). Across the OECD, evaluation processes with clear procedures and criteria are more effective at producing good school leadership practices (OECD, 2013[8]).

Schools lack autonomy and resources to pursue improvements

Schools in BiH lack autonomy to make financial and other management decisions that affect how the school functions and develops (Branković et al., 2016[9]; Gabršček, 2016[4]). These powers are centralised at the competent education authority level. Depending on the administrative unit, municipalities may also make some school funding decisions. In addition, the particularities of BiH’s institutional set-up tend to reduce the funding that is available to schools. Since each authority is responsible for their own education system, they generally spend a considerable percentage of their education budgets on administrative costs, such as salaries for personnel, including teaching staff (e.g. 91% in FBiH), leaving limited funds for capital investment and improvement measures (World Bank, 2019[5]). Furthermore, most authorities use a school funding model that is based on inputs (e.g. norms and standards for class sizes) rather than factors that reflect a school’s actual budgetary needs (ibid). In Central Bosnia Canton and West Herzegovina Canton, for instance, funds are allocated based on the number of teachers in the school, regardless of the size of the student population or other school characteristics that affect funding needs (BiH, 2021[10]).

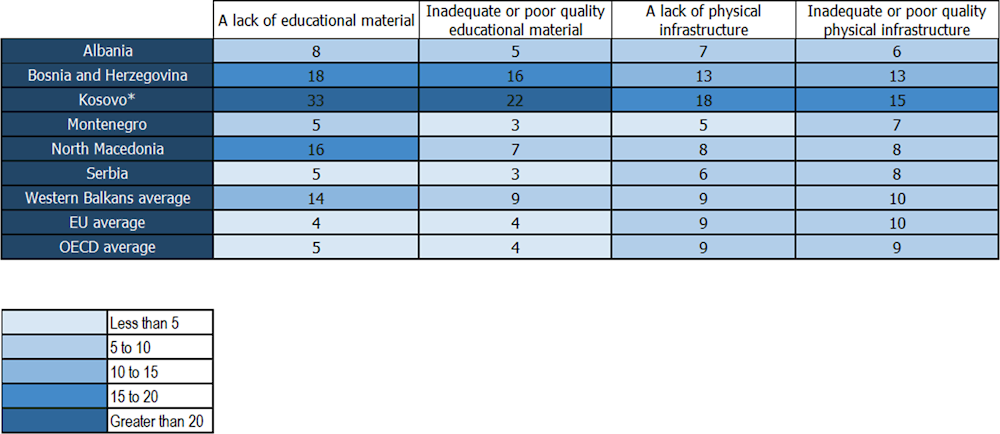

In some administrative units, schools rely on local donors to cover some costs, which puts schools in low socio-economic areas at a disadvantage. Many schools in BiH lack resources. In PISA 2018, for instance, a significant share of BiH students studied in schools where the principal reported that instruction was hindered by a lack of educational material, inadequate or poor quality educational material, a lack of physical infrastructure, and inadequate or poor quality physical infrastructure (Figure 4.1) (OECD, 2020[11]). This has implications for school evaluation and improvement, since schools that struggle to cover their basic material and infrastructure needs will not be in a strong position to develop their practices.

Figure 4.1. Principals’ perceptions of key educational resources

Note: Darker tones indicate greater reported lack of resources.

Source: Adapted from (OECD, 2020[12]), Education in the Western Balkans: Findings from PISA, https://doi.org/10.1787/764847ff-en.

School evaluation in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Most competent education authorities in this review do not have external school evaluation or school self-evaluation procedures. The exceptions are Republika Srpska, which recently introduced a framework for both types of school evaluation, and West Herzegovina Canton, which now requires schools to conduct self-evaluations. The other education authorities in this review conduct periodic on-site reviews of schools’ practices, but these are not based on consistent standards of school quality. Internationally, such standards are an integral feature of school evaluation frameworks. Without them, competent education authorities lack the means to make well-informed judgements about how schools are performing in relation to broader system priorities and to compare their results to identify and support the most at-risk schools.

There is also scope for education authorities to strengthen the link between school monitoring or evaluation activities and school improvement. Positively, each authority has a body that can provide support to schools – either a pedagogical institute or an equivalent in the respective Ministry of Education. However, authorities do not systematically use the results of school supervision or evaluation to prioritise schools for support. Furthermore, resource and capacity constraints impede the implementation of school monitoring and evaluation activities. For example, pedagogical institutes and their equivalents lack the staff to conduct regular monitoring visits. Within this context, developing school self-evaluation capabilities is critical, because it can help schools to drive their own development. However, schools do not conduct this type of evaluation in three of the five authorities in this review. Where it is conducted, schools need more external support to review and improve their practices.

Table 4.1. Types of school evaluation in Bosnia and Herzegovina

|

Types of school evaluation |

Reference standards |

Body responsible |

Guideline documents |

Process |

Frequency |

Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

External school evaluation (Only in Republika Srpska) |

Different sets of standards for: elementary schools; secondary schools; vocational schools |

Pedagogical institute |

None |

1) Selection of sample schools 2) Inspection 3) Completion of inspection 4) Delivery of inspection report, and publishing on website |

Not regulated, but the goal is once every five years |

Accountability and to improve the quality of educational work |

|

School self-evaluation (Only in Republika Srpska and West Herzegovina Canton) |

Same standards as external school evaluation (Republika Srpska) |

School self-evaluation team or school development team |

Professional instructions for: elementary schools; secondary schools; vocational schools (Republika Srpska) |

1) Form a self-evaluation team 2) Study standards and indicators 3) Collect materials and documentation 4) Identify strengths and weaknesses 5) Draft a report on the self-evaluation process 6) Design solutions and actions; identify opportunities, constraints and resources needed 7) Draft an improvement plan with goals, roles and responsibilities, and a time frame (Republika Srpska) |

Annual |

School self-improvement; to inform the school development plan and school priorities |

Source (Pedagogical Institute of Republika Srpska, 2019[13]), СТРУЧНО УПУТСТВО за самовредновање квалитета васпитно-образовног рада у основној школи [Professional instructions for self-evaluation of the quality of educational work in elementary school], https://rpz-rs.org/sajt/doc/file/web_portal/04/4.8/2018-19/Strucno_uputstvo_za_samovrednovanje_rada_OS.pdf, (accessed 26 April 2021); (BiH, 2021[10]), Country Background Report for the OECD Review of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Bosnia and Herzegovina, unpublished.

External school evaluation

Most of the competent education authorities in this review do not conduct external school evaluations or have school quality standards

The education authorities in this review have made efforts to introduce external school evaluations in the past. For example, in 2012, the state-level Agency for Pre-school, Primary and Secondary Education (APOSO) worked with competent education authorities to develop and implement a school evaluation toolkit with standardised criteria in four important areas: i) school climate; ii) co‑operation with the parents’ council and student council; iii) school management; and iv) and teacher competences (Council of Ministers of Bosnia and Herzegovina, n.d.[14]). Indicators in this toolkit covered some school practices that research identifies as effective at improving student outcomes for the 21st century, like networking with other schools and teamwork among teachers (OECD, 2016[15]). While some authorities and schools implemented the toolkit, it was reportedly not supported by a number of BiH governments and it fell out of use.

Instead of conducting external school evaluations, four of the five competent education authorities in this review use general school supervision procedures. This form of monitoring provides a snapshot of a school at a point in time. Positively, it commonly includes an on-site observation of classes, which can provide insight into the quality of instruction. School supervisions often result in a report (with findings and recommendations), which a number of principals noted as helpful. However, it is not a systematic process. While some administrative units, like Brčko District and Central Bosnia Canton, require that every school be subject to general supervision within a certain period of time, this is not the case with all of the administrative units. Specifically, unlike two-thirds of EU education systems, the majority of competent education authorities in this review do not measure schools against consistent indicators of quality (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[16]). The result, as one school leader told the review team, is a lack of continuity between monitoring rounds and no long-term analysis of how school practices are impacting student outcomes. The lack of consistent standards also means that education authorities cannot compare schools to determine which need to improve the most. Furthermore, most authorities do not, as a matter of course, offer support to struggling schools as a follow up to school monitoring activities, to make sure they have capacity to improve.

Republika Srpska has introduced a school evaluation framework

Republika Srpska introduced school quality standards and processes for external school evaluation and school self-evaluation in 2017/18. Positively, this new school evaluation framework was based on international best practices and refined after an initial pilot and feedback from participating schools. The school quality standards cover aspects of a school environment that are most important to improve students’ learning, including instructional leadership (Table 4.2) (OECD, 2013[8]). A particularly good feature of the standards is their focus on school self-evaluation. This can motivate schools to regularly assess their practices in order to plan improvements. While the standards state that schools should conduct formative assessments of students, which is positive, teachers do not receive any tools or support in using formative assessment in their classroom and the use of external standardised tests are mainly for monitoring system performance rather than to support learning (Chapter 2).

Table 4.2. Republika Srpska’s school quality standards

|

Standards |

Examples of indicators |

|---|---|

|

School management and administration |

The director initiates and takes measures to improve the work of the school based on an analysis of student achievement, as well as the results of monitoring and evaluating the work of employees. |

|

Teaching and learning |

Key competences are integrated into teaching and learning, regardless of the subject or subject area. |

|

Student achievement |

Student assessment is done formatively and summatively and in accordance with the rulebook on assessment of students. The achieved results of external checks of student achievements show if students have achieved the average for Republika Srpska or are above this average. |

|

Student support |

The number of students who dropped out of school or were transferred to another school is lower than in the previous school year. |

|

Co-operation of the school with the family and institutions in the local community (Elementary) Organisation and content of curricula (Secondary and Vocational) |

The school has a system for regularly informing parents about school activities (Elementary). Teachers critically analyse the curricula of their subjects, and record their observations, remarks and suggestions for improvement (Secondary). The curriculum is systematically revised to ensure consistency with the needs of students, trainees and the economy, through established systems, in order to determine training needs and provide the qualifications the labour market needs (Vocational). |

|

Human, physical and specialist resources within the school |

The professional development plan of teaching staff envisages various forms and ways of professional development training and is aimed at improving the quality of work and the work of teachers. |

|

Quality assurance systems and procedures |

The school writes a periodic report on the conducted self-evaluation which contains an action plan as well as responses to identified weaknesses. |

Source: (BiH, 2021[10]), Country Background Report for the OECD Review of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Bosnia and Herzegovina, unpublished.

Republika Srpska’s external school evaluations are stronger at supporting accountability than school improvement

Republika Srpska’s external school evaluation process appears similar to other EU countries (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[16]). The director of the pedagogical institute appoints a team of five to seven evaluators, which can include external expert advisors and evaluators, such as principals or pedagogues, to conduct the evaluation. Positively, they also receive training for their role. The evaluators then review documentation about the school, including its self-evaluation report and undertake an on-site inspection. At the end of the process, they produce an inspection report with findings, ratings (both an overall rating and a rating against each standard as insufficient, satisfactory, good, or excellent) and recommendations for improvement.

External school evaluations in Republika Srpska include procedures that support accountability and encourage schools to act upon recommendations. For example, if a school receives ratings that are below satisfactory, the pedagogical institute will set a deadline for improvement and conduct a follow-up evaluation. The institute also requires all schools to develop an action plan that responds to inspection findings and post all inspection reports publicly on its website. However, more could be done to support school improvement. While schools can ask the institute for support at any time, low-performing schools do not automatically receive more guidance or attention following an evaluation to help them improve.

There is also no guarantee that all schools will receive a regular external evaluation. The pedagogical institute identifies a sample of schools to evaluate each year based on factors such as size and the number of employees. However, unlike many OECD countries, Republika Srpska does not regulate the school evaluation cycle (OECD, 2015[7]). In addition, Republika Srpska has not had enough expert advisors to conduct the evaluations it plans each year, although a recent re-organisation of the pedagogical institute may address this issue. The entity has also struggled to attract external evaluators from the private sector who could help evaluate VET schools.

Competent education authorities face challenges in monitoring and evaluating schools

Competent education authorities lack sufficient resources to conduct regular school monitoring, which must compete for time and resources with other responsibilities under their mandate, including curriculum development, professional teacher supervision and teacher training (World Bank, 2021[17]). The COVID‑19 pandemic has compounded these constraints, putting a halt to external school monitoring and evaluations in the jurisdictions covered by this review. Furthermore, Sarajevo Canton has not monitored schools since the jurisdiction closed its pedagogical institute in 2021. The canton does not plan to carry out school monitoring until it establishes the new Institute of Pre-University Education.

Several factors affect the credibility of school monitoring and evaluation

Expert advisors in pedagogical institutes have conflicting roles, which may make their judgements less credible. Specifically, their parallel mandate to support schools may reduce objectivity in reviewing the same schools’ practices. In addition, in some BiH education systems, there are concerns that expert advisors may be subject to political pressure in their work (Gabršček, 2016[4]), and this relates to broader concerns about integrity in BiH’s education system (Chapter 1). Representatives of one authority, for instance, noted that schools are sceptical about advisors’ independence because the pedagogical institute is part of the ministry. In some administrative units, the capacity of expert advisors may also be limited by low salaries and a lack of training (World Bank, 2021[17]). If supervision and evaluation processes are not viewed as credible, schools are less likely to trust the results and therefore act upon them.

School self-evaluation

School self-evaluation is not mandatory in most of the jurisdictions covered in this review

Schools do not conduct regular self-evaluations in three of the five jurisdictions covered in this review. In Sarajevo Canton, school self-evaluation is not mandatory. In Central Bosnia Canton, legislation states that schools may conduct self-evaluations to inform their annual development plans, but there is no document that prescribes this process in more detail (BiH, 2021[10]). In Brčko District, the school principal is required to report to the school board on implementation of the annual plan, but self-evaluation is not required. This is a significant gap. School self-evaluation is an essential complement to external school evaluation. In OECD countries, it involves school staff regularly reviewing their practices, often to inform their school development plans (OECD, 2013[8]). Schools thus continuously work towards their own improvement rather than relying solely on external bodies to identify and address their weaknesses.

Republika Srpska and West Herzegovina Canton have some strong school self-evaluation processes, but schools may lack capacity to conduct them effectively

Republika Srpska and West Herzegovina Canton require schools to conduct self-evaluations once a year, like the majority of OECD and EU countries where this practice is compulsory (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[16]; OECD, 2015[7]). The methodologies in both administrative units have a number of strengths that are consistent with recommendations in the research literature and common practice internationally. Specifically, there is a high level of staff involvement in school self-evaluation. For example, Republika Srpska’s professional instructions state that the school self-evaluation team should consist of a heterogeneous mix of teachers and may also include representatives of the parents’ council and student council (Pedagogical Institute of Republika Srpska, 2019[13]). Self-evaluation also engages school stakeholders, including members of the local community in Republika Srpska. This is important to gather a range of perspectives to inform the evaluation, and to promote shared responsibility for school quality (European Commission, 2020[18]). Furthermore, Republika Srpska and West Herzegovina Canton require schools to use self-evaluation results to inform their development plans, which helps ensure that the process leads to improvement. In West Herzegovina Canton, for instance, self-evaluations inform schools’ one‑year and three‑year priorities. In addition, schools in Republika Srpska are expected to use the same school quality standards that are used for external school evaluation, which helps to provide a consistent message on the factors that are important to high-quality teaching and learning and the student outcomes they are working towards (OECD, 2013[8]).

However, schools’ capacity to conduct self-evaluations may be an issue, particularly in Republika Srpska. School leaders told the OECD review team that the process feels rushed. Republika Srpska provides schools with self-evaluation supports that are common in EU countries, including guidelines, training, and external specialists in the form of pedagogical institute expert advisors (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[16]). Nevertheless, school staff reported that they find the current half-day workshop, delivered using a train-the-trainer method, to be insufficient. They reportedly feel less prepared than when they could audit school evaluations and participate in more extensive training offered jointly by the Pedagogical Institute of Republika Srpska and the non-governmental organisation “Economic Policy and Regional Development”.

School-level data and its use

Bosnia and Herzegovina lacks data on school quality and student outcomes

In general, expert advisors and schools in BiH lack easy access to data that would allow them to monitor or compare school quality. Some authorities do not have the capacity to develop an electronic information management system (EMIS), which many OECD countries use to cyclically collect data about schools’ contextual features (e.g. student, teacher and school demographics) and student outputs and outcomes (e.g. completion rates and national exam results). Indeed, education systems in BiH are characterised by a lack of data on student learning outcomes (Branković et al., 2016[9]). Of the authorities in this review, only Sarajevo Canton and Republika Srpska conduct external tests of student learning (an examination in Sarajevo Canton, and an assessment in Republika Srpska).

Policy issues

Republika Srpska and West Herzegovina Canton have introduced school evaluation procedures, and other competent education authorities have made efforts to introduce school evaluations over the past ten years. However, most authorities conduct “snapshot” reviews of schools in lieu of external evaluations that provide information on performance against consistent standards of quality. Furthermore, all authorities struggle to monitor or evaluate schools regularly due to resource and capacity constraints. These weaknesses in both the design and delivery of school evaluation have significant implications for educational improvement in BiH. They mean that, at present, most education authorities cannot reliably account for the quality of teaching and learning in their schools nor evaluate whether and how policies to enhance instruction and outcomes are being implemented in the classroom. School leaders and teachers, themselves, lack perspective on their practices, and parents and children cannot accurately compare the quality of education in different institutions. This lack of reliable information on school quality also makes it difficult for authorities to channel support measures effectively.

To improve school quality and student outcomes, it will therefore be essential for competent education authorities to introduce school monitoring procedures that are both more systematic and more efficient. Specifically, they should develop school quality indicators that relate to goals for student learning and development, identify schools that are not meeting a quality baseline, and provide these schools with targeted support. While all authorities have expert advisors in pedagogical institutes or their equivalents who provide supports to schools, they do not focus on struggling schools for follow-up support. Competent education authorities should develop procedures for expert advisors to provide hands-on support to at-risk schools and ensure that they have the capacity to fulfil this role. Finally, all authorities should introduce school self-evaluation methodologies and provide guidance, resources and training – in some cases, with the support of a state-level body – so that schools can use evaluation results to implement improvements. Developing schools’ internal capabilities to evaluate the quality of their practices and define their own improvement objectives is particularly important in BiH given that resource and capacity constraints prevent most authorities from implementing regular external school evaluations.

Policy issue 4.1. Using consistent measures of school quality to support school improvement

The vast majority of OECD countries conduct external school evaluations (29 out of 37 as of 2015) (OECD, 2015[7]), often based on school quality standards that are linked to national education priorities. As a result, all schools can see what will be measured, evaluators have clear guidance for their judgements, and education authorities have a means to monitor and report publicly on progress toward agreed goals. External evaluation is also, and above all, a valuable resource for school improvement. It can serve as both an internal resource, to develop a culture of reflection and learning within schools, and as an external resource, to inform the design of support programmes, and (where needed) additional oversight.

In BiH, Republika Srpska has started to evaluate schools against a set of school quality standards. Other authorities implemented external school evaluations in the past, using APOSO’s school evaluation toolkit. In most administrative units in this review, expert advisors from the pedagogical body conduct school monitoring – in some cases, based on detailed rulebooks. However, these reviews are not systematic and are not always based on standardised measures of school quality. Resource constraints also preclude regular, cyclical school visits in all of the administrative units in this review. As a result, authorities cannot identify schools that are most in need of support to assist student learning. This is an acute gap, particularly given performance differences between different types of school in BiH. In PISA 2018, for instance, students from rural schools attained significantly lower reading results (by 50 points) than students from urban schools (OECD, 2020[12]). Competent education authorities will need to ensure that school monitoring is consistent, efficient and focused on school improvement in order to address these challenges.

Recommendation 4.1.1. Develop indicators of school quality

While most competent education authorities cannot introduce systematic external school evaluations or conduct regular school supervisions in the short- to medium-term, it would be beneficial to provide more targeted support to schools. Authorities could therefore develop a set of school quality indicators to inform regular monitoring of at-risk schools. These indicators could be developed as a collective effort between different competent education authorities in partnership with APOSO, as the state-level body with expertise in education standards, and could address shared education priorities.

Develop indicators of school quality connected to goals for education

APOSO should collaborate with competent education authorities to identify the main changes that are needed to improve school quality. These could be related to common education goals (Chapter 5). In Bulgaria, for instance, stakeholders recently developed a vision of a school in 2030, which reflects the country’s new school quality standards and its long-term education strategy (Box 4.1).

Box 4.1. Bulgaria’s vision of school in 2030

Vision for education, training and learning in the Republic of Bulgaria in 2030:

In 2030, all Bulgarian young people graduate from school as functionally literate, innovative, socially responsible and active citizens, motivated to upgrade their competences through lifelong learning.

The institutions of pre-school and school education in 2030 offer the most safe, healthy, ecological and supportive environment, where educational traditions, innovative pedagogical solutions and digital development co‑exist. They constantly evolve as spaces for learning and development, for recreation and interaction between children, students, parents and the local community, united by shared values to achieve a common goal – the formation of knowledgeable and capable individuals able to make responsible choices and to achieve their goals in a dynamic and competitive social environment.

Source: (MoES, 2020[19]), Strategičeska Ramka za Razvitie na Obrazovanieto, Obučenieto i Učeneto v Republika Bǎlgarija (2021 - 2030) [Strategic framework for the development of education, training and learning in Republic of Bulgaria (2021-2030)], Ministry of Education and Science, Sofia.

Building on this analysis and reflection, competent education authorities, with support from APOSO, should define a core set of five to ten school quality indicators that are relevant to all cantons and entities, as well as (potentially) a set of indicators that education authorities could apply at their discretion. Competent education authorities could also develop additional indicators that relate to their specific contexts and goals and could share these with each other to facilitate peer learning. As in the OECD (Table 4.3) and a growing number of Western Balkan countries, BiH’s indicators should address aspects of schooling that are most important to students’ learning and development, as well as student outcomes.

Table 4.3. Common school quality indicators in OECD countries

|

Categories |

Examples of indicators |

|---|---|

|

Context |

|

|

Inputs |

|

|

Quantitative outcomes |

|

|

Qualitative outcomes |

|

|

Equity in outcomes |

|

|

School processes |

|

Source: (Faubert, 2009[20]), School evaluation: Current practices in OECD countries and a literature review, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 42, OECD Publishing, Paris; (OECD, 2013[8]), Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment, OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264190658-en.

This set of core indicators should focus, in particular, on dimensions for improvement that have been highlighted through international studies and new state-level education goals (Chapter 5). These indicators could be both qualitative and quantitative, but education actors in BiH may need to focus on the latter, at least initially, since they will be easier to collect and analyse. In developing indicators, actors could look to countries such as Brazil, which has a large, decentralised education system, or Romania or Colombia (Box 4.2). Areas of focus could include:

Outcomes related to student learning and progress. In BiH, competent education authorities could agree to a number of indicators such as rates of student absenteeism, advancement and/or graduation rates, as quantitative outcomes of student progress. However, this review makes several recommendations about how BiH can address the lack of reliable data on student learning outcomes through the use of standardised tests, which would support this essential dimension of school quality (Chapter 2). This could become another indicator, particularly given that international studies suggest that students’ learning outcomes are lower in BiH than in the OECD and other Western Balkan countries (OECD, 2019[21]). In the short term, indicators on learning outcomes will need to rely on school-based assessments, which should aim to measure the extent to which students in a particular school have mastered core competences.

Outcomes related to equity. Competent education authorities could agree to a number of indicators that measure outcomes for students from minority backgrounds and students with special education needs. This would address the issue that Roma children are less likely to participate in education than other demographic groups in BiH (Chapter 1).

The school context and inputs that impact student outcomes. For example, PISA 2018 found that, in BiH, students’ geographic location (i.e. urban vs. rural) was associated with significant differences in reading results, and that educational resources were reported as insufficient in many lower secondary schools (OECD, 2020[12]).

School processes that are important to students’ learning and development, like whether or not schools are conducting self-evaluations for improvement (Policy issue 4.2).

In the short to medium term, competent education authorities could use core indicators to regularly monitor at-risk schools. Over the longer term, they could use both core and optional indicators to structure school supervisions and/or external school evaluations. Optional indicators could be more qualitative, and similar to Colombia’s Synthetic Index of Education Quality (Box 4.2).

Box 4.2. Indicators of school quality in different OECD member and partner countries

Brazil’s Índice de Desenvolvimento da Educação Básica (IDEB) or Basic Education Development Index

Brazil’s IDEB was developed in 2005 to increase accountability and provide a strong impetus for school improvement. It allows the country to identify schools or education systems whose students show low proficiency levels and to see changes in students’ performance over time. IDEB is based on quantitative student outcomes from Brazil’s 200 000 schools, including learning data from national assessments of Portuguese and mathematics in grades 4 and 8; assessment data for grade 11 students; and student flow data (i.e. promotion, repetition and graduation rates). The use of student outcomes that relate to both learning and promotion to the next grade is intended to ensure that schools are not incentivised to hold back students from the tested grades or encourage them to drop out of school. The federal government calculates IDEB scores at school, municipal, state or national levels from primary to upper secondary, and sets related targets which inform school improvement plans. A new IDEB by School (IDEB por Escola) platform allows users to combine IDEB 2019 results with context indicators for each school (e.g. infrastructure, resources and pedagogical organisation) and compare IDEB results by groups of schools with similar characteristics.

Romania’s School Efficiency Index

Romania’s Agency for Quality Assurance in Pre-University Education (ARACIP) calculates an efficiency index for each school to inform external school evaluations and school self-evaluations. The index indicates how a school’s results compare to other schools functioning in similar conditions with similar resources. ARACIP began developing the index in 2009, piloted it in 1 023 schools across all levels in 2011, and then revised it and expanded its use to more schools in 2014. The index is based on:

Context and input indicators: family background (e.g. the percentage of children from families with low income); education environment (e.g. school location in socio-economically disadvantaged area); infrastructure (e.g. availability of basic utilities); equipment and teaching aids; the level of ICT use in the school; and human resources (e.g. the percentage of qualified teachers).

and the following quantitative student outcomes:

Participation: average number of absences per student; student drop-out rate; and rate of grade repetition.

Results: the distribution of average classroom assessment marks at the end of the school year; average results on the grade 8 and baccalaureate national examinations; and average results in the competence certification exam for vocational schools.

Colombia’s Índice Sintético de Calidad Educativa (ISCE) or Synthetic Index of Educational Quality

Since 2015, Colombia has used its ISCE to provide a clear and contextualised indicator of school quality. The ISCE provides a numerical indicator to measure the quality of education in schools by education level (primary, lower secondary and upper secondary). ISCEs score ranges from 1 to 10 (with 10 being the best result possible), and is composed of four components: i) school performance (40%), based on students' learning results in the country’s annual national external assessment (known as SABER), in Language and Mathematics; ii) progress (40%), which reflects the progress of student learning in the SABER tests compared to the previous year; iii) efficiency (10%), based on the schools’ approval rates; and iv) school environment (10%) based on information collected from context questionnaires given to students during the SABER tests (known as Associated Factors). This last component consists of two combined measures: classroom environment and monitoring of learning. At upper secondary level, this latter component is not calculated, and the efficiency component counts for 20% of the calculation. The ISCE provides the educational community and the general public with a simple (and therefore easy to interpret) yet contextualised and comprehensive indicator of education quality.

Source: (OECD, 2021[22]), Education Policy Outlook: Brazil – With a Focus on National and Subnational Policies, https://www.oecd.org/education/policy-outlook/country-profile-Brazil-2021-EN.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021); (INEP; Ministéria de Educação; Governo Federal Brasil, 2013[23]), Index of Development of Basic Education, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/aboutpisa/3.%20Luiz%20Costa_June_2013%20-%20IDEB%20OCDE.pdf (accessed 12 November 2021); (OECD, 2011[24]), Lessons from PISA for the United States, Strong Performers and Successful Reformers in Education, OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264096660-en; (Kitchen et al., 2017[25]), OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Romania, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264274051-en.

Engage government bodies and stakeholders in the development process

While school quality indicators should be developed with experts in each competent education authority who are knowledgeable about schooling, the initiative should also engage government decision-makers, including the Ministry of Civil Affairs of BiH and the heads of each education authority. Engaging these actors should build a shared understanding of how the indicators could benefit BiH by contributing to school improvement, thus strengthening support for their use. In developing the indicators, competent education authorities, with the support of APOSO , should also gather input from a wide set of stakeholders, including the representatives of NGOs, the private sector, academia, parents, and school staff. This will ensure that the indicators reflect different perspectives and build collective ownership. School staff, in particular, will be more accepting if they are involved in the development process (Faubert, 2009[20]).

Develop plans to collect indicator data in ways in order to minimise onerous reporting tasks for schools. At present, some administrative units in this review require schools to provide additional information when they conduct school supervisions. A growing number of OECD countries use information stored in education management information systems (EMIS) for school evaluation and supervisions to reduce the reporting burden on schools. In BiH, a number of competent education authorities do not have the capacity to develop their own EMIS. To reduce the burden of data collection, competent education authorities should develop plans that identify how to compile data required for the school quality indicators in the most efficient way. These plans should outline, for instance, which data authorities can already access, and which additional data can be collected on a cyclical basis through existing EMIS or dedicated modules in a new limited EMIS (Chapter 5). As recommended in Chapter 5, competent education authorities should also make efforts to improve the quality of data, in order to ensure that judgements about school quality and comparisons between schools are reliable.

Recommendation 4.1.2. Use data from the school quality indicators to identify and support at-risk schools

Pedagogical institutes and their equivalents in competent education authorities are responsible for supporting schools. Although they face financial and capacity constraints, they are well positioned to fulfil this role. However, they do not currently use data to identify struggling schools – though this data could be – and, at times, is – produced through general school supervisions or external school evaluations. Competent education authorities should use the school quality indicators to identify schools that are struggling the most and direct more resources and targeted support towards them.

Develop a methodology for identifying at-risk schools, informed by a pilot

Competent education authorities will need to develop a risk assessment methodology in order to use the indicators to identify schools that most require support. This methodology could include:

Minimum expectations for each quality indicator and input, such as minimum standards for student attendance and progression or a minimum level of basic school infrastructure.

Risk factors related to context indicators, such as having a high concentration of students at greater risk of poor performance given their backgrounds (e.g. socio-economic status).

These thresholds could be based on analyses of data that education authorities already collect, as well as the results of a pilot in each participating administrative unit. The recommendation to incorporate a pilot into the development process builds on lessons learnt from the APOSO school evaluation toolkit project. Following that project, government actors reportedly did not support incrementally improving the toolkit, and ultimately it fell out of use. A pilot would help competent education authorities to establish minimum expectations for school quality, ensure that the indicators are fit-for-purpose, and address issues around the collection and analysis of data.

Provide more intensive hands-on support to at-risk schools

Competent education authorities should task pedagogical institutes or their equivalents with working closely with schools that are identified through the school quality indicators as at-risk. At present, they are already expected to provide technical support to schools, much of which focuses on pedagogy. In Brčko District, for instance, the pedagogical institution’s regulated tasks include planning teachers’ professional development (Chapter 3), advising on teaching methods, and helping schools to develop partnerships with the local community and support students with special education needs (BiH, 2021[10]). However, these activities are largely disconnected from school supervision results and are not targeted to at-risk schools.

Competent education authorities should establish guidance that clearly sets out how expert advisors should work with at-risk schools. Specifically, expert advisors should help these schools develop action plans that address areas where they are not reaching minimum expectations, and then work with school staff as they implement these plans. Expert advisors could, for example, provide coaching to school staff on different teaching, learning and school management practices and help to identify financial resources that would address school needs, such as continuous professional development grants (Chapter 3) or school improvement grants (Recommendation 4.3.2). To make sure that expert advisors can provide this support, competent education authorities may need to re-define their roles and invest in building their capacity (Policy issue 4.2).

The financial and capacity limitations of pedagogical institutes or their equivalents, should be considered in designing procedures to support at-risk schools. For example, expert advisors could make use of new electronic platforms to engage with a high volume of teachers and schools at relatively low cost. They could, for instance, use a platform that helps coach teachers in at-risk schools on using student-centred teaching approaches (Chapter 3) or a new school improvement platform, which would identify measures to reduce drop-outs (Recommendation 4.3.2).

Introduce a formal networking programme to support at-risk schools

Competent education authorities should provide at-risk schools with opportunities to benefit from horizontal learning, which is a powerful support for school improvement (OECD, 2013[8]). At present, formal school networking programmes of this type do not seem to exist in the administrative units in this review. Competent education authorities should create networks by using results from the school quality indicators to pair schools that are at-risk with those that are doing well. Expert advisors in pedagogical institutes or their equivalents could support this networking by arranging meetings of school principals or school study visits. They could provide guidance to prepare model schools for their role and monitor the impact of networking activities on at-risk schools. In developing this initiative, competent education authorities could look to international examples of networking programmes such as a UNICEF initiative in Serbia. There, UNICEF’s SHARE programme (Box 4.3) demonstrated the importance of adequately assisting both low- and high-performing schools to ensure that this relationship is constructive (Baucal and Pavlović Babić, 2016[26]).

Box 4.3. The UNICEF SHARE networking programme in Serbia

The SHARE project, a joint initiative between UNICEF, the Ministry of Education, Science and Technological Development of Serbia, the Centre for Education Policy (a research centre in Belgrade) and Serbia’s Institute for Education Quality and Evaluation (IEQE), is the first initiative in Serbia aimed at creating learning communities and peer-learning between schools. SHARE aims to improve the quality of education by developing horizontal learning between schools and developing schools’ and teachers’ agency to learn and lead change in the education system. The initial phase of the project took place between 2015 and 2017, with 20 schools, 1 080 teachers and 12 665 students participating across Serbia. The project paired 10 schools that performed very well in the external school evaluation (score of 4), known as “model schools”, with 10 schools that underperformed (score of 2 or 1), known as “SHARE schools”.

The project used a reflective approach combining classroom observation and feedback on observed practice. Following the selection of participating schools, classroom visits were planned to support reflective practice. During this step, teachers, school principals and support staff from SHARE schools observed between 10 to 15 hours of teaching at model schools. Based on a pairing system, the majority of discussions between schools focused on classroom management, lesson planning, teaching techniques, student support, teamwork and preparing for external evaluation. To give constructive feedback during these peer-to-peer sessions, staff in the model schools received training on how to articulate, document and share their success with their paired schools. During the final school visits, SHARE schools were also given the opportunity to present their experience and examples of best practices, thus motivating self-reflection.

The SHARE project initiated and established mutual exchange of knowledge and best practices between schools. It provided schools with hands-on experience through its peer-to-peer-learning component. In addition, as a way to enhance the sustainability and long-term benefits of the project, a learning portal was created and shared amongst educators in Serbia. Moreover, 100 practitioners were trained to provide support for quality improvement in low-performing schools, creating a network of facilitators who have been integrated into the ministry of education as educational advisors linked to school administrations around the country.

The first phase of the project had a positive impact on the 20 participating schools and shows scope for growth and scaling up. A majority of participating schools have seen an improvement in six out of seven areas of quality measured by the external school evaluation. This improvement was mostly seen in the areas of teaching and learning, school ethos and organisation of work and leadership. More broadly, the project introduced participating staff to the concept of horizontal learning and encouraged teachers to work together without the fear of being judged by their peers. It also allowed them to practice new teaching methods and play a more active role in shaping their classroom and school practices.

Source: (UNICEF, n.d.[27]) Dare to Share: Empowering Teachers to be the Change in the Classroom; (European Commission, 2017[28]), Networks for Learning and Development across School Education, https://www.schooleducationgateway.eu/downloads/Governance/2018-wgs5-networks-learning_en.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2021).

Consider publishing summary reports instead of individual school results

Education actors in BiH should focus on using the school quality indicators to pave a constructive path to school improvement. While competent education authorities may wish to publish individual schools’ results, this could make the indicators more contentious, and thus more difficult to implement. It could also have negative consequences for schools, creating undue pressure on school staff and penalising those who operate in difficult circumstances. A number of OECD member and partner economies, including Shanghai, have opted not to publish individual school results to avoid these problems. In lieu of individual school results, education authorities may wish to publish regular summary reports that provide a descriptive overview (i.e. not just scores or ratings) of what schools are doing well and what they need to improve. This is a common practice in OECD countries (OECD, 2013[8]), and should build a better understanding of school quality in relation to education goals among parents and the broader public.

Recommendation 4.1.3. In the long-term, consider introducing external school evaluations in all administrative units

Using the indicators recommended above will help competent education authorities to monitor school quality, but it cannot replace regular school evaluations (OECD, 2013[8]). In OECD and EU countries like Romania, the Netherlands and Ireland, school quality data supplement external school evaluation processes but are not a replacement (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[16]). Over the long-term, competent education authorities should consider developing BiH-level or authority-level external school evaluations. These evaluations would be more standardised than general school supervision practices, and more comprehensive than baseline monitoring against school quality indicators. If designed well, these evaluations could have a greater impact on school improvement than other types of school monitoring.

Replace general school supervision with external school evaluation

Competent education authorities could discuss their readiness to introduce external school evaluations at future meetings of the Conference of Education Ministers (Chapter 5). They should consider developing a school evaluation framework at the BiH-level or authority-level that includes the following elements, which are common in OECD countries or recommended in the research literature:

Independent evaluators. Many OECD and European countries have established independent school evaluation agencies to build professional expertise in one body and ensure that evaluations are fair and credible. For example, in New South Wales, a state in Australia’s decentralised education system, the National Education Standards Authority (NESA) serves as an independent statutory authority with responsibilities for conducting school inspections. NESA operates under the direction of a governing board that is separate from the state-level government (NESA, 2021[29]). Internationally, school inspectorates, like those in nearby countries (e.g. Bulgaria and the Slovak Republic), may be funded by the government but are independent in their methodology and reporting. This independence generally means that external school evaluations are objective and free from political influence (OECD, 2013[8]). In the long-term, competent education authorities in BiH with sufficient capacity could establish their own inspectorates – either alone or in partnership with other authorities. Alternatively, education actors in BiH might consider establishing a state-level inspectorate, if education authorities agree to the expansion of the state’s authority. To support objectivity in the short- to medium-term and avoid conflicts of interest, personnel responsible for supporting a school should not be responsible for its supervision or evaluation.

More qualitative school quality standards that focus on the aspects of the school environment that are most important to students’ learning and development. These include the quality of teaching and learning and the quality of instructional leadership, as well as measures like students’ cognitive and social/emotional outcomes (OECD, 2013[8]). Qualitative standards will facilitate a deeper review of school processes and should thus be more helpful for improvement purposes (ERO, 2016[30]). For example, in evaluating the quality of instructional leadership, external school evaluations could not only confirm whether schools are conducting self-evaluations for improvement but also look at schools’ self-evaluation processes to provide advice on how they could be improved. This is a common practice in OECD countries to help build schools’ self-evaluation capacity (Policy issue 4.3) (OECD, 2015[7]).

School evaluation procedures that prioritise struggling schools. In EU countries, an external school evaluation will generally comprise: i) a pre-inspection, during which evaluators gather initial information about a school; ii) a school visit that focuses, in particular, on the quality of instruction, and; iii) the preparation of an evaluation report (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2015[16]). Schools are commonly evaluated once every three years or more in OECD countries (OECD, 2015[7]). However, some countries, like New Zealand, the Netherlands and Ireland, have introduced differentiated inspection cycles in which low-performing schools are evaluated more frequently than high-performing schools. Competent education authorities could consider a similar model, to focus resources and attention on schools that need the most support to improve.

School evaluation results that balance improvement and accountability. Features of external school evaluation systems that support school improvement include clear feedback on schools’ strengths and weaknesses, feasible recommendations, the requirement to produce action plans, and supportive follow-up. To support accountability, features include the public reporting of evaluation results (Faubert, 2009[20]). As advised for school monitoring in Recommendation 4.1.2, authorities should use external school evaluation results to support school improvement. Over the longer term, competent education authorities might also consider publishing school evaluation reports that provide an overview of a school’s practices in relation to quality standards and key findings from the evaluation. This will address a lack of school transparency in BiH, which can feed public concerns about corruption in the education system (Gabršček, 2016[4]).

Policy issue 4.2. Developing the expert advisor and school leader roles

The administrative units in this review will require strong system and school leadership to improve school quality. At present, pedagogical institutes and their equivalents are understaffed and have very broad mandates. Expert advisors are often responsible for monitoring and supporting the same schools, which can create conflicts of interest and inhibit the development of supportive working relationships with school staff. Many of the pedagogical institutes covered in this review expressed a need for training to develop expert advisors’ capacity but reported that this is not available. Positively, some authorities plan to professionalise the school leadership role. However, all have yet to develop key elements of professionalisation, such as school leadership standards, initial training requirements and principal appraisal processes. Furthermore, principal appointments remain vulnerable to politicisation despite changes to selection procedures over the past decade. While there are positive examples of supports for school leaders, such as the Body of Pedagogues’ School of Principals in Republika Srpska which provides counselling and advice, there are also gaps in principals’ continuous professional development. A number of school leaders in BiH reported that they have not been offered training for several years, while others reported that available training is not relevant to their needs. Competent education authorities will need to address these gaps in order to develop the expert advisor and school principal roles.

Recommendation 4.2.1. Strengthen the school support capacity of expert advisors

Pedagogical institutes or their equivalents have a large number of responsibilities, from policymaking to school monitoring to support, and limited resources to undertake them (World Bank, 2021[17]). Competent education authorities will need to address the workload and staffing challenges that impede the institutes’ work. To enable expert advisors to focus on supporting schools, education authorities will also need to adjust their responsibilities and ensure that they have the capacity to fulfil them.

Dedicate staff at the canton, entity and district level to supporting school improvement and self-evaluation

Competent education authorities should create expert advisor positions in pedagogical institutes or their equivalents, who would be responsible for providing support to at-risk schools and helping schools with self-evaluation. At present, most expert advisors focus on providing support and control for specific subject areas or for different school levels, and at least one authority in this review also has advisors that work with school leaders. Competent education authorities should create new job profiles for dedicated school improvement experts and re-orient the mandates of some expert advisors, particularly those who already work with school leaders, to take on these roles. Authorities could look to countries like Wales (United Kingdom), where local authorities and regional education consortia employ “challenge advisors” who work with school leaders to help schools improve, as well as specialists in different teaching and learning areas (Welsh government, 2014[31]). Like in the Canadian province of Ontario, competent education authorities might also consider focusing the efforts of these experts towards initiatives that would support state- or authority-level education goals (Box 4.4). As recommended in Chapter 3, competent education authorities could create similar roles for teachers in order to co‑ordinate system- and school-level improvement efforts. In the medium- to long-term, competent education authorities could open job competitions to recruit school leaders or teachers at the higher levels of their career path (particularly those with experience in school development or in different education priority areas) to become new school improvement experts.

Box 4.4. Leadership roles at the system and school level in Ontario, Canada

In 2003, the Ontario Ministry of Education implemented the Student Success / Learning to 18 Strategy to increase graduation rates and provide all Ontario students with the tools to successfully complete their secondary schooling and reach their post-secondary goals. The strategy was introduced in phases, beginning with capacity development to promote strong leadership in schools and school boards and to change school culture to achieve long-term systemic improvement.

At the school board level, it created a new senior leadership role, the Student Success Leader, who was responsible for co‑ordinating efforts in their district and networking with Student Success Leaders in other districts to share strategies.

At the school level, it created the Student Success Teacher to provide support to students at risk of dropping out. In addition, secondary schools established Student Success Teams, consisting of school leaders, Student Success Teachers and staff. The teams tracked and addressed the needs of students who were disengaged, and also worked to establish quality learning experiences for all students.

According to an evaluation of the Student Success / Learning to 18 Strategy, developing good leadership at all levels – Ministry, school board, and school – coupled with extensive capacity building were key to the success of the reform. In 2011/12, Ontario had a high-school graduation rate of 83%, a 15-percentage point improvement over the period 2003/04.

Source: (OECD, 2015[32]), Education Policy Outlook: Canada, https://www.oecd.org/education/EDUCATION%20POLICY%20OUTLOOK%20CANADA.pdf (accessed on 8 December 2021) ; (OECD, 2012[33]) Lessons from PISA for Japan, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264118539-en.

Address issues with capacity and understaffing

To ensure that expert advisors can provide sufficient support to schools, competent education authorities will need to address capacity constraints in pedagogical institutes or their equivalents as a matter of priority. This is a problem that affects all competent education authorities in this review. For example, one of the largest pedagogical institutes in BiH informed the OECD review team that they lack sufficient staff because their mandate had become increasingly complex. Smaller administrative units reportedly have even fewer staff – not enough to provide support to schools for different curriculum subject areas – and have a heavy workload related to areas where they lack capacity, such as legal work. At the same time, training, which could help expert advisors be more effective in their roles, is scarce. Authorities could consider the following measures to address these challenges:

Review the workload of pedagogical institutes and their equivalents. In many OECD member and partner countries, separate institutions are responsible for the different tasks that fall within pedagogical institutes’ mandate. Over the long-term, competent education authorities should consider establishing different agencies – like school inspectorates – to take on some of these responsibilities (Recommendation 4.1.3). In the short-term, competent education authorities should identify ways to reduce the workloads of expert advisors and enable them to focus on school support. For example, this could involve re-distributing their policymaking duties to other staff. Furthermore, expert advisors who support schools should not also be tasked with evaluating them (Recommendation 4.1.3). Other recommendations in this report would help to reduce expert advisors’ workload. For instance, authorities could delegate the appraisal of teachers for career advancement to external contractors (Chapter 3).

Consider increasing the number of staff and/or partnering with NGOs. Alongside reviewing the workload of expert advisors, authorities should review the staffing complement of pedagogical institutes and their equivalents and consider hiring more expert advisors, particularly new school improvement experts, to supplement existing staff. Given that expert advisors’ remuneration in some administrative units has not been sufficient to attract experienced professionals, further limiting pedagogical institutes’ capacity (World Bank, 2021[17]), authorities may need to consider salary increases. Another solution could be to partner with NGOs to help schools conduct self-evaluations (Recommendation 4.3.2) and work towards education goals. This could offset shortfalls in staff and capacity.

Provide opportunities for expert advisors from different jurisdictions to work and learn together. Expert advisors from different jurisdictions could form a network or networks in order to exchange experiences and collaborate, either in-person or online. To improve their effectiveness, this initiative could discuss common challenges facing schools and different approaches to support them. The Conference of Education Ministers could discuss the creation of this network and other potentially useful collaborations at one or several annual meetings recommended in Chapter 5.

Offer training to build expert advisors’ capacity to support schools. Competent education authorities should ensure that expert advisors use new online learning platforms for teachers and schools for their own capacity building (Chapter 3 and Recommendation 4.3.2). In addition, authorities should create a mentorship system that matches new expert advisors with experienced colleagues. Introducing these types of electronic and job-embedded professional learning opportunities provide lower-cost solutions for supporting schools.

Recommendation 4.2.2. Transform the school principal role to strengthen instructional leadership

During past education reform efforts, competent education authorities committed to appointing school leaders using fair and democratic procedures and providing them with relevant training (BiH, 2002[1]). More recently, different competent education authorities have signalled their intent to strengthen school leadership, in some cases, because they plan to provide schools with greater autonomy in the long-term. However, in BiH, as in many other Western Balkan economies, the appointment of school leaders is highly vulnerable to political interference and limited training opportunities are available (OECD, 2020[12]). To improve school quality, it will be essential for competent education authorities to ensure that the most qualified candidates are selected, and that they receive regular opportunities to build their instructional leadership capacity.

Revise school principal appointments to remove political influence

All education authorities that were interviewed for this review reported that the school leader hiring process remains influenced by politics even though candidates need to fulfil regulated requirements. For example, even in jurisdictions where political appointees do not directly select candidates, they reportedly influence the selection committees’ decisions. While challenging, education authorities should work to de-politicise recruitment in order to build a stronger cadre of school leaders. Key steps could include:

Introducing school leader certification requirements, including mandatory training. This will ensure that all candidates have a grounding in school leadership before taking on the role. With the support of a state-level body or NGO, competent education authorities should develop professional standards for school leadership to inform the contents of training and other certification requirements (see below). Training should provide practical preparation in all areas of school leadership, including planning and implementing school improvements. Like North Macedonia and Albania, education authorities could also require candidates to pass an exam to demonstrate their readiness for school leadership (OECD, 2020[12]) (Box 4.5).

Enhancing selectors’ impartiality. Competent education authorities should also apply EC recommendations for public administration reform in BiH to the selection of principals. This could include, for instance, establishing independent selection committees for principal appointments and using transparent procedures to appoint members to those committees (European Commission, 2019[34]). At present, school board members are often involved in the principal recruitment process, but their selection is also politicised (Gabršček, 2016[4]). Education authorities might consider involving an impartial actor in appointment procedures and making decisions using a confidential majority vote. In the Slovak Republic, for example, an inspector from the State Schools Inspectorate provides an objective perspective on each principal selection committee, and some school boards select principals based on confidential votes for their preferred candidate (Santiago et al., 2016[35]). At the state level, education actors could develop advice on how all actors involved in selecting individuals for public sector roles could maintain professionalism and impartiality.

Reviewing and revising principal appointment procedures to ensure that they are merit based. Competent education authorities should, for example, revise their procedures to include transparent selection criteria that are based on standards of school leadership. Competent education authorities could also develop guidelines to help selection committees assess how well candidates’ knowledge, skills and attitudes align with the standards.

Introduce collaborative learning opportunities and appraisals to support school leadership development