Over the last two decades, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH) has become a middle-income country and made some progress to improve the socio-economic development and quality of life of its population (European Commission, 2021[1]). However, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita remains one of the lowest in the region, indicating the country’s ongoing struggle to raise productivity and living standards. As of 2015, around 17% of the BiH population was living below the poverty line and there are large regional disparities in terms of access to services and well-being outcomes (World Bank, 2020[2]). Similar to other countries in Europe, the COVID-19 pandemic has led to a contraction in the BiH economy, exacerbating challenges that were already present, such as raising revenue for public services and allocating resources efficiently. Recovery efforts and future growth will depend on the extent to which BiH governments can address structural challenges, including demographic shifts, high levels of unemployment, especially among youth, and the need for investment in infrastructure and human capital.

OECD Reviews of Evaluation and Assessment in Education: Bosnia and Herzegovina

Assessment and recommendations

Introduction

Improving education outcomes is key to supporting inclusive growth in Bosnia and Herzegovina

A complex education governance structure presents challenges for reform efforts

Education has a key role to play supporting BiH’s COVID-19 recovery efforts and helping the country to achieve more inclusive growth and social cohesion. However, the decentralised governance structure and lack of co-operation at the state level creates significant challenges for setting strategic objectives, policy coherence, and ensuring the effective delivery of public services. There are fourteen “administrative units” or governance tiers in BiH: one at the level of the state (BiH); two entities (Republika Srpska; RS and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina; FBiH); one self-governing district (Brčko District; BD); and ten cantons of the FBiH entity. In the area of education, BiH and FBiH government officials are mainly responsible for policy co-ordination and running country- or federation-level initiatives. Officials from entity, canton and district units are referred to as “competent authorities” and define their own laws and strategies to regulate education policy. BiH also has expert and co-ordination bodies that operate at the state-level (e.g. the Agency for Pre‑school, Primary and Secondary Education, APOSO and the Conference of Ministers of Education in BiH (chaired by the BiH Ministry of Civil Affairs)). This complex education governance structure makes it difficult to develop and implement systemic reforms.

Performance on international assessments reveals a need for BiH to raise learning outcomes and address equity concerns

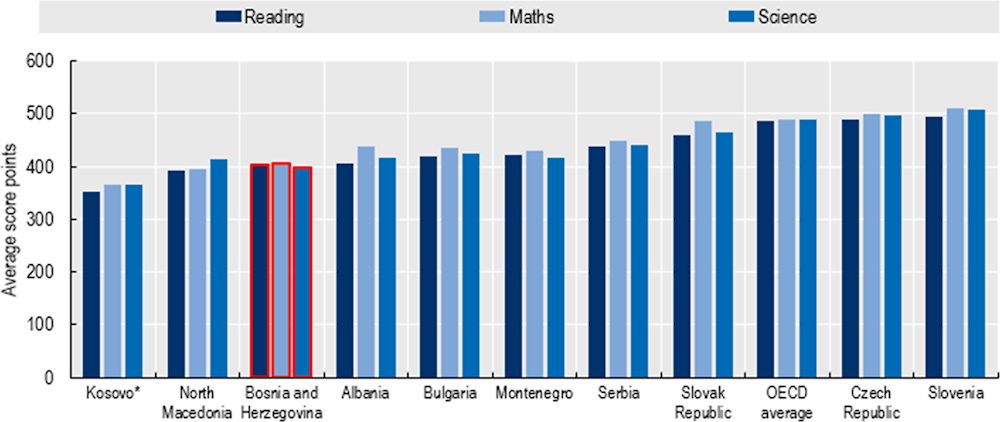

Data from international assessment reveal concerns about the effectiveness of school systems in BiH. For example, data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) show that despite the country’s 15-year-old students performing similarly to their peers in other Western Balkan economies, they are behind the average learning outcomes achieved in OECD and EU countries (see Figure 1). Moreover, around 41% of students in BiH have not achieved the minimum level of proficiency (defined as Level 2) in all three subject areas assessed by PISA; compared to only 13% on average across the OECD (OECD, 2019[3]). Students from disadvantaged communities and families are most likely to achieve poor outcomes and disparities start early. For example, access to quality early childhood education is very limited in BiH, despite its multiple long-term benefits for children, and in particular for children from marginalised backgrounds. In 2018, gross enrolment in pre-primary education (ISCED 02) in BiH was 25%, compared to the Western Balkan average of 53% and the EU and OECD averages of 98% and 81% respectively (OECD, 2021[4]). The COVID-19 pandemic, like in many other education systems around the world, has also disproportionally affected the country’s most vulnerable student populations, including children and young people with disabilities and those from Roma communities. However, there is very limited data and research on educational equity issues in BiH. A stronger culture of evidence-informed policymaking could help to renew focus on providing quality learning opportunities for all students.

Figure 1. Students’ proficiency in PISA across all domains, PISA 2018

Source: (OECD, 2019[3]), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en.

Spending on education is higher in BiH than in other Western Balkan economies but there are significant inefficiencies

In 2018, BiH spent around 4.4% of its GDP on education, which was similar to the EU (4.7%) average and slightly higher than neighbouring Western Balkan economies, such as Albania (3.6%, 2017) and Serbia (3.7%, 2018) (UNESCO UIS, 2021[5]). However, the faces significant challenges in terms of resource efficiency. This situation partly relates to the high administrative costs of funding salaries for the civil servants of 14 separate education authorities (World Bank, 2019[6]). Since local authorities raise their own funding for education, there are also important disparities in provision across and within administrative units. To some extent, these differences reflect variations in the salary regulations of different administrative units and the costs of service delivery in rural versus more urban areas (ibid).

Some competent education authorities use multi-grade classes to raise coverage rates without increasing the costs associated with having separate teachers and classrooms for each grade level. However, these learning environments are often more challenging for teachers to manage and can have an impact on the amount and use of learning time in the classroom. Within this context of inadequate and inequitable education financing, donor agencies often contribute resources for interventions focused on improving educational quality, such as by providing teacher training and investing in school infrastructure. At the same time, gaps in policy continuity, co-ordination and planning, especially in the face of demographic decline, means that it can be difficult to channel donor assistance in a way that generates sustained, systemic improvements to student outcomes.

The majority of secondary students in BiH graduate from technical and vocational programmes but many do not master core competences

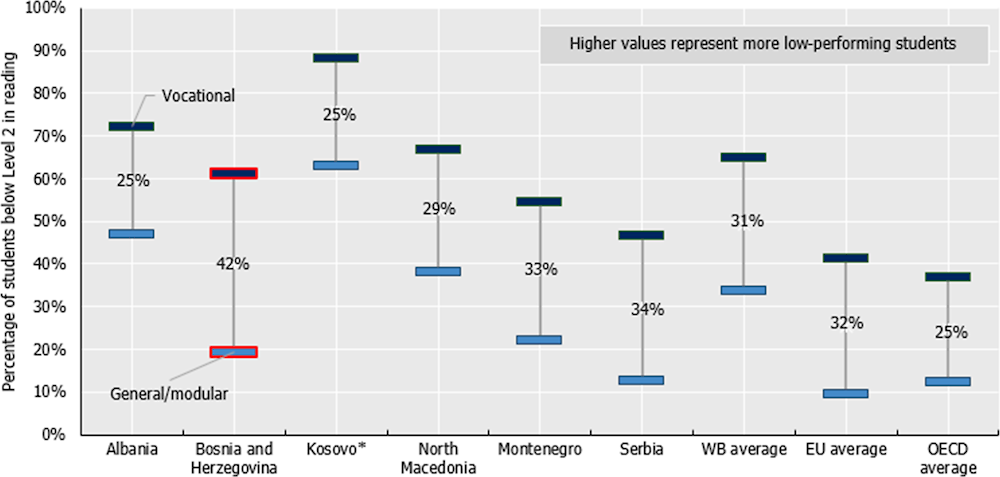

According to data from 2017 (the latest date for comparable data), BiH reported a high proportion of persons aged 20-24 who had attained at least upper secondary education (94%), even though this level of schooling is not compulsory in most parts of the country. This attainment rate is similar to Montenegro (95%), Serbia (93%) and North Macedonia (89%), and much higher than the EU average of 83% (Eurostat, 2019[7]). However, various factors undermine the positive social and economic potential of having so many young people complete upper-secondary education (ISCED 3; referred to simply as “secondary education” in BiH). For example, the lack of established standards and measures to check that students are learning as they pass through basic education mean that many are entering secondary school without mastering the competences expected at this level. Moreover, the majority of students (around 77% in 2019) enrol in technical and vocational secondary programmes (VET), many of which are considered to be of low quality compared to highly selective gymnasia (GIZ, n.d.[8]; UNESCO UIS, 2021[5]) (World Bank, 2019[6]) (OECD, 2021[4]). This context, coupled with inequalities in basic education, as well as the weight of school and societal factors in selecting students into secondary pathways, reduces students’ chances of developing relevant technical and vocational skills and consolidating their core academic skills. While it is common among countries with large VET sectors to have gaps in the core reading and numeracy skills of students in VET versus students in general education, only 19% of students in general education in BiH were low performers, compared to 61% of VET students; a much larger difference compared to other countries (Figure 2). As a result, the most disadvantaged students have least chance of acquiring knowledge and skills to progress after graduation. The situation is exasperated later in life, reflected by the country’s low tertiary enrolment rates and high rates of youth unemployment.

Figure 2. PISA 2018 low-achieving students and education programmes

Note: WB: Western Balkans.

Source: Adapted from (OECD, 2021[4]), Competitiveness in South East Europe 2021: A Policy Outlook, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcbc2ea9-en.

Evaluation and assessment in Bosnia and Herzegovina

Over the past decade, the OECD has reviewed evaluation and assessment frameworks in over 30 education systems to help identify policies and practices associated with improving educational quality in different contexts. This research revealed three hallmarks of a strong evaluation and assessment framework that promotes the quality and equity of student learning. First, such a framework sets clear standards for what is expected nationally of students, teachers, schools and the system overall. Second, it directs the collection of data on performance, helping to ensure that stakeholders receive the information and feedback they need to reflect critically on their own progress and identify steps that will help them advance. Third, it promotes coherence and alignment, so the whole education system can work in the same direction and use resources effectively. This report recommends ways in which BiH can strengthen its evaluation and assessment framework in the school education sector. The report covers seven BiH administrative units that reflect differences in terms of population size, development levels, governance responsibilities and geographic location. These include: the state level (BiH); the two entities of RS and FBiH; Brčko District, and a sample of three cantons (Sarajevo Canton, Central Bosnia Canton and West Herzegovina Canton).

In recent years, officials from across BiH have been taking steps to improve the country’s education systems. For example, the CCC was designed at the state level in consultation with competent education authorities and now serves as a reference for the ongoing development of achievement standards for each grade level and key subject areas. Some competent education authorities have already started to design and implement new curricula in line with this state-level document, but disparities in capacity and political will have contributed to a lack of consistency in the CCC’s implementation (World Bank, 2019[6]) (OSCE, 2020[9]). This situation makes it difficult for students to move horizontally across different education systems within the country, and hinders progress towards introducing the more student-centred pedagogies that underpin the CCC and have the potential to raise learning outcomes.

BiH also has very limited comparable data about its education sector. For example, the Agency for Statistics of BiH does not report or calculate data on enrolment rates and unlike most EU members and a growing number of Western Balkan economies, there is no external standardised assessment system at the state-level to generate timely data to monitor student learning. Participation in international assessments like the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) is also unstable, leaving BiH without updated and comparable trend data on system performance. This context makes it very difficult for government officials to make evidence-informed policy decisions. It also leaves many of schools, teachers and the broader public with limited information to hold their governments accountable and help make improvements to teaching and learning.

This review recommends ways that BiH could improve collaboration among competent education authorities to support all children in mastering the competences they need for success in education, work and life. Specifically, the report calls upon policymakers in the country to prioritise a targeted set of sustainable policy reforms that extend beyond election cycles. By providing BiH with technical recommendations for the short and long-term, this report aims to influence the political debate around education in the country to focus actors on what matters most: student learning. Competent education authorities are encouraged to review these recommendations, and adapt those which are most relevant and adequate to meet their own needs and contexts.

Student assessment supports learning by helping teachers, students and parents determine what learners know and what they are capable of doing. This information can help identify specific learning needs before they develop into serious obstacles and enable students to make informed decisions about their educational pathways.

Education systems in BiH have taken steps to introduce new competence-based curricula and most of the competent education authorities covered by this review have introduced some changes to their student assessment policies, such as the use of qualitative descriptors to accompany quantitative scores or diagnostic “check-in” tests to establish an initial benchmark of student performance. However, these policy reforms have not led to real changes in classroom practices, in part because they have not been accompanied by adequate tools and support for teachers. As a result, teachers’ classroom assessments do not encourage student learning a well as they might be. There remains a narrow emphasis on summative testing and a lack of attention to formative methods or assessments of more complex, higher-order competences.

Expectations of student learning outcomes are also not clearly or consistently signalled and measured. While Republika Srpska (RS), Sarajevo Canton and Tuzla Canton have established external assessments of student learning, the majority of education systems in the country face major capacity and resource constraints that prevent them from developing and using standardised assessments to improve the reliability of teachers’ marking and signal expectations for student learning. These factors, coupled with the limited co‑operation among administrative units, prevent BiH from developing standardised assessment practices at the state level, something many Western Balkan and European education systems have either established or are currently developing. Limited state-level co‑operation also prevents BiH from securing regular participation in international assessments, such as PISA.

With very few external benchmarks of student performance, grade inflation is a major concern in BiH, especially at transition into secondary education (ISCED 3), when teachers face pressure to provide grades that enable students to access their study programme of choice. Societal expectations and a competitive assessment culture also pressure teachers to focus on their top performing students, who are often also among the most advantaged. Since teachers and schools receive very limited support and resources on how to assist students who are struggling, this context risks leading to decisions that reflect student background more than ability. For example, data from PISA reveal that socio-economically disadvantaged students in BiH are around four times more likely to attend a VET secondary school (ISCED 3) than a general one (OECD, 2020[10]). Such findings not only raise questions about the ways students are selected into secondary education programmes in BiH but also about need for more objective measures to signal to employers and higher education institutes that students have mastered core competences by the end of formal schooling. Addressing these challenges and leveraging the educational value of assessment will be key to raising student learning outcomes and developing human capital.

Improving student assessment: areas for policy action

Policy Issue 2.1. Strengthening the educational value of student assessment.

International and state level actors in BiH, as well as competent education authorities have been working to implement education reforms with the goal of equipping students with the core competences needed for success in further studies, work and life. While many BiH education systems are very experienced with summative assessments that measure knowledge, there is a need for more balanced assessment frameworks that advance a student-centred and competence-based learning agenda. This includes much more support for teachers on how to assess learning in relation to specified outcomes and standards, and on how to integrate assessment results and feedback into the teaching and learning process. At present, teachers in BiH are generally left on their own to develop assessment criteria, receive limited professional development on formative assessment practices and have access to few, if any, resources to help strengthen their overall assessment literacy. BiH will need to foster a new assessment culture from the bottom-up and develop resources, training and professional networks that can help teachers appropriate more effective assessment practices. Involving parents and the wider society in these changes will also be crucial: without their understanding of why and how changes to assessment practices can benefit their children, there is likely to be resistance to reforms.

Recommendation 2.1.1. Take steps to shift the culture of learning and assessment. Many of the administrative units covered by this review already have elements within their student assessment frameworks that can support stronger links between assessment and learning (e.g. start-of-year diagnostic tests). However, with few exceptions, there are no resources or training opportunities to help use assessments formatively and changes to assessment policies often face resistance from teacher unions, parents and broader society. To enhance the learning value of student assessment in BiH, competent education authorities should adjust their rulebooks to emphasise a more balanced set of assessment practices. The rulebooks should provide definitions of key assessment techniques and topics (reliability, validity, formative assessment, etc.) to help strengthen teachers’ assessment literacy and set a clear expectation that teachers evaluate student achievement against defined learning standards. It will be important to communicate the value of these changes to stakeholders. Such efforts can build support for a new culture of assessment that can help raise student learning outcomes.

Recommendation 2.1.2. Collaborate with teachers and other actors to create resources that strengthen the educational value of classroom assessments. Finalising the development of learning standards that align with the Common Core Curriculum Based on Learning Outcomes is a top priority for APOSO. While having learning standards for all grade levels and key subjects can help focus attention on essential basic competences, teachers in BiH will need support on how to use these standards in their classroom practices if they are to serve to improve assessment and learning. Competent education authorities should take decisions about what specific supports and resources would be most effective in their education system and could for example, require teachers to record descriptive feedback and justification for some of their marks vis-à-vis the learning standards. However, there are also opportunities for APOSO to work with relevant partners to prepare core materials, such as examples of marked student work, assessment tasks and diagnostic assessment tools, which could immediately help teachers and students appropriate the standards. These types of resources can be a powerful way to improve the quality of teacher assessment practices and help students advance in their mastery of core competences.

Recommendation 2.1.3. Provide teachers with training and support to develop their assessment literacy. Building teachers’ assessment literacy by adapting rulebooks and providing resource materials are effective ways to help strengthen the educational value of student assessments. However, student assessment topics are not systematically covered in more formal teacher training and education opportunities in BiH. In fact, RS was the only administrative unit covered by this review where teachers reported participating in specific training modules on how to assess students; although some of this training was theoretical and based on textbooks, rather than practical experience and tools that teachers could apply directly to their assessment practice. This suggests a clear need for actors in BiH to promote a better understanding of student assessment through initial teacher education programmes, practicum experiences and professional development opportunities.

Policy Issue 2.2. Prioritising the development and implementation of external examinations.

At present, there are no standardised state-level examinations in BiH and only one canton (Tuzla) has a standardised external exam at the end of secondary education (ISCED 3). While standardised examinations have been implemented in RS entity and Sarajevo canton at the end of basic schooling (ISCED 2), many administrative units are unable to develop and implement such instruments on their own because they lack the required financial resources and technical capacity. The absence of reliable measures of achievement can have negative implications for student learning: the fact that more than half of students across BiH do not achieve baseline proficiency on the PISA reading test by age 15 suggests that students are moving through the country’s school systems without a clear understanding of whether they have mastered foundational competences, such as literacy or mathematics (OECD, 2019[3]). This makes reform to examinations in BiH a strong lever for focusing the country’s education systems on the need for all students to develop key competences, regardless of the specific curricula they follow, what secondary track they complete or where they attended school.

Recommendation 2.2.1. Develop an optional external examination of core competences. Only one competent education authority in BiH provides students with a chance to validate their knowledge, skills and competences through an external examination (Matura) at the end of secondary school (ISCED 3). In a country where grade inflation is a widely recognised problem, this creates a range of challenges related to the rigour and reliability of secondary school diplomas, as well as to the fairness and efficiency in how decisions about students’ future are made. To address these challenges, competent education authorities and APOSO should work together, with support from the donor community, to design an external examination of core competences at the end of secondary education. This new, BiH Matura should be optional for competent education authorities (at least in the beginning) and could be limited to an assessment of students’ core competences (e.g. literacy, numeracy and science). The results from this exam should be considered as part of a wider range of graduation requirements set by competent education authorities, which would help raise the value of secondary qualifications by certifying students’ mastery of core competences upon graduation.

Recommendation 2.2.2. Build the technical capacity to conduct and use standardised assessments. Once the concept and technical specifications for the new BiH Matura have been established, BiH will need to build the administrative systems to implement the exam. This infrastructure is currently lacking since the country has limited familiarity with standardised testing. Specifically, this effort should include identifying the right actors to carry out tasks such as checking the quality of test items or producing test booklets. BiH may also need to develop its testing software and information and communications technology (ICT) infrastructure to administer and mark the exam via computer, which could build public trust in the integrity of the exam by minimising the use of items that require human marking. More broadly, APOSO should work with competent education authorities to promote a better understanding of the potential benefits and risks of standardised assessments and explain their role within a comprehensive student assessment framework. Collaboration in this area within BiH and among international peers could help leverage assessment data to drive improvements in system performance, teaching practices and student learning.

Teacher appraisal supports teaching and learning by providing teachers with feedback on their performance and competences. Well-designed appraisals support teachers’ professional development and hold them to account for their practice, in turn helping to raise student achievement.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, competent education authorities are beginning to promote the more student-centred teaching and learning approaches that are becoming increasingly common across OECD and EU countries. However, teaching practices have been slow to change, largely due to a lack of supports and incentive structures that would encourage the adoption of new approaches to help all students develop core competences. Resource and capacity limitations make these efforts even more challenging in BiH. For example, the bodies responsible for organising or delivering training to teachers – typically a pedagogical institute or equivalent – often lack sufficient staff and funding. Competent education authorities therefore need to be both efficient and systematic in supporting teachers to develop modern approaches to pedagogy. Professional teacher standards can serve as a foundation for building the supports and incentives that encourage desired teaching practices. For example, they can serve as a reference for providing more relevant initial teacher education programmes and continuous professional development opportunities. Competent education authorities can also leverage the potential of digital technology and in-school learning activities to help as many teachers as possible develop their practices. Furthermore, new formative and summative teacher appraisal processes, if well designed, can help teachers focus on developing their practices and reward them for their efforts.

Improving teacher appraisal: Three areas for policy action

Modernising teaching practices is a key challenge for BiH. Positively, all competent education authorities in the country helped to develop Occupational standards for teachers in general education (hereafter the occupational teacher standards) in 2016‑17 to set out expectations for what teachers should know and be able to do in their role. However, the majority of education systems in this review are not using the occupational standards, and in jurisdictions where local standards have been developed, they are not yet being implemented. To improve teaching and learning, competent education authorities should adopt teacher standards that encourage teachers to use student-centred approaches that can help reduce disparities in learning outcomes and raise overall performance. They should use these standards as the basis for appraisal processes that support teachers’ development and to inform the design of professional learning activities and resource materials that will help to steer innovation in teaching practices.

Recommendation 3.1.1. Introduce standards-based appraisals to help teachers develop their practices. Competent education authorities should adopt the 2016‑17 occupational teacher standards (with or without modifications) or develop their own standards. Many OECD countries use such standards to provide a reference for teachers to reflect on their practice, identify professional development goals and serve as criteria for regular performance appraisals. To develop these standards, competent education authorities should engage practicing teachers and post standards on a new central platform once they are finalised to encourage peer learning across the country. The teacher standards should serve as criteria for new teacher self-evaluations and regular appraisals. In the medium to long term, education authorities should revise their standards to describe the competences teachers should develop to advance to higher levels in their career. Having differentiated standards will provide a stronger lever for improving teaching quality, especially if used as criteria in new appraisal for promotion procedures (see below).

Recommendation 3.1.2. Harness digital technology and promote collaboration between teachers to translate standards into practice. To overcome a lack of resources, competent education authorities should make the delivery of continuous professional development to improve teachers’ practices more systematic, efficient and coherent. For example, interested education authorities should work together, with APOSO’s support, to develop an online platform that provides teachers with relevant, standards-based learning resources. Education authorities and their pedagogical institutes or equivalents should also support teachers’ collaborative, job-embedded learning, including the activities of school-based teacher groups and the work of school pedagogues. Such in-school professional learning has the potential to be less costly and more effective at developing teachers’ competences than traditional training seminars. Furthermore, to support system-wide education reform, the Ministry of Civil Affairs or entity, canton and district authorities should consider providing grants to schools to conduct continuous professional development in areas that address broader education priorities.

Policy Issue 3.2. Motivating teachers to improve their teaching practices.

Positively, all competent education authorities in this review have developed career paths for teachers. However, most are not conducting merit-based promotions and often consider other factors, such as years of teaching experience. To encourage teachers’ professional development more systematically, competent education authorities should establish new appraisal for promotion procedures and other initiatives to motivate and reward effective teachers.

Recommendation 3.2.1. Recognise teachers’ competency development and high performance. Competent education authorities should review and revise their teacher career structures to connect higher career levels to substantial salary increases and clearly‑defined responsibilities. This will help incentivise teachers to develop competences for career advancement and ensure that qualified teachers assume more complex roles to improve teaching and learning in their school and education system. Education authorities should also consider introducing measures to recognise quality teaching – in addition to career advancement – in ways that support education system goals. For example, they could give exceptional teachers opportunities to lead improvement in key areas in their school or pursue studies at the master’s degree level that address school or system priorities (e.g. inclusive education; formative assessment; ICT).

Recommendation 3.2.2. Introduce objective appraisal for promotion procedures. To further motivate teacher development, all competent education authorities in BiH should begin conducting merit-based appraisals for promotion again. However, they should first revise their procedures to strengthen the integrity of appraisal decisions, as these have high stakes for a teacher’s career. Credible appraisals for promotion would involve appraisers who are completely impartial and who make decisions based on multiple sources of evidence about a teacher’s competences that are measured against consistent and transparent standards. Given resource constraints, competent education authorities should have the option to seek support from a central body to conduct these types of appraisals. For example, APOSO could promote economies of scale by supporting competent education authorities in developing a common appraisal for promotion process and common training for appraisers. Education systems in BiH will also need to develop practical guidelines and other resources to support implementation of the appraisal process. These materials will be key not only to ensuring consistent judgements about teachers’ performance but also in helping teachers understand how to demonstrate that they are ready for a promotion.

Policy Issue 3.3. Providing sufficient initial preparation to new entrants to the teaching profession.

Positive features of teacher preparation in BiH include the existence of accreditation procedures for tertiary institutions as well as a compulsory internship for all newly employed graduates of initial teacher education (ITE) programmes. However, ITE programmes in BiH generally cover less content on pedagogy, psychology, didactics and methodology than is common in EU countries (Branković et al., 2016[11]). The quality of ITE programmes also varies across institutions, and there are particular concerns about private providers. Furthermore, all new teachers are not assured the same level of mentorship support during their internship, primarily because mentors lack clear guidance for their role. To better prepare new entrants to the teaching profession, BiH should make quality assurance measures for ITE programmes more rigorous and strengthen the mentorship of interns. Competent education authorities should also make better use of teacher supply and demand data to help direct resources for teacher preparation more efficiently.

Recommendation 3.3.1. Ensure that all future teachers are prepared for the demands of today’s classrooms. Competent education authorities should work together with state-level bodies and tertiary institutions to make the criteria for ITE programme accreditation more specific to initial teacher preparation. Revised criteria should, for example, define what teachers should know and be able to do by graduation, according to the occupational teacher standards. BiH should also introduce measures at the state and/or canton, entity and district level to ensure that programmes meet these criteria. Such measures could include new mandatory procedures for programme accreditation and new prerequisites for entry to the teaching profession that relate to initial teacher preparation. To ensure sufficient mentorship of new teachers, education authorities should clearly define the responsibilities of mentors and provide them with guidelines, training and other supports. Education authorities should also make sure that VET teachers who enter the profession as a second career receive sufficient preparation in student-centred teaching approaches since these individuals will likely need to address the skills and knowledge gaps of their students in addition to preparing them for a particular vocational field.

Recommendation 3.3.2. Use data to adjust entry requirements for initial teacher education and ensure an appropriate supply of teachers. Unlike the majority of European countries, competent education authorities in BiH do not conduct systematic forward planning to inform policies related to the supply of new teachers (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2018[12]). Developing a forecasting model – at the state or administrative unit level – would help to predict the demand for teachers in each of the country’s education systems. Competent education authorities should use this model to develop or adjust policies to help ensure an appropriate supply of motivated and competent teachers, such as admission quotas or acceptance thresholds for ITE programmes.

School evaluation, if well designed, supports teaching and learning by helping schools to improve their practice and holding them accountable for the quality of the education that they provide to students.

In recent years, several competent education authorities in BiH have moved away from an administrative, compliance-oriented approach to school quality assurance towards more evaluation-based procedures focused on developing instructional practices. In OECD countries, such evaluations also generate information that can be used to inform school improvement policies and provide a system-wide perspective of school quality. However, most of the education authorities in this review conduct “snapshot” reviews of schools in lieu of external school evaluations that would yield this type of data. Specifically, the reviews are not based on consistent standards of school quality, which makes it difficult for authorities to form reliable judgements about school performance and to determine where to direct school improvement supports. Given the considerable resource and capacity constraints facing many competent education authorities, education officials will need to use resources pragmatically and prioritise schools that are most in need of support to assist student learning. Specifically, all competent education authorities should develop consistent school quality indicators to identify and target supports to at-risk schools. This in turn requires authorities to build the capacity of pedagogical institutes or their equivalents to provide hands-on support to schools. Furthermore, authorities should encourage schools to conduct self-evaluations to drive their own development. Such efforts can help improve teaching and learning environments in BiH to raise outcomes for students.

Improving school evaluation: Three areas for policy action

In BiH, Republika Srpska has started to evaluate schools against a set of school quality standards. However, despite efforts in the past, most authorities do not use consistent standards to monitor or evaluate school quality. Resource constraints also preclude regular, cyclical school visits. Such constraints will make it difficult for most authorities to introduce systematic external school evaluations in the short- to medium-term. To leverage available resources to raise student outcomes, competent education authorities should develop efficient school monitoring activities that focus on at-risk schools.

Recommendation 4.1.1. Develop indicators of school quality. Competent education authorities should work together, with APOSO’s support, to develop five to ten school indicators to identify schools that do not meet a minimum baseline of quality. They should engage government decision-makers and stakeholders in the development process to build a shared understanding of how the indicators could benefit BiH. The indicators should address shared concerns, including student progress and learning outcomes (e.g. rates of student absenteeism, advancement and/or graduation), school processes (e.g. teaching methods, guidance and support for students, compliance with regulations) and contextual features that impact school performance (e.g. geographic location, number of shifts or use of multi-grade classrooms, socio-economic situation, etc.). Education authorities should also develop plans to collect indicator data that minimise onerous reporting tasks for schools.

Recommendation 4.1.2. Use data from the school quality indicators to identify and support at-risk schools. Competent education authorities should develop a methodology to identify at-risk schools using the school quality indicators and direct more resources and targeted support towards these schools. Supports should include intensive, hands-on coaching from pedagogical institutes or their equivalent in competent education authorities and a formal networking programme that pairs at-risk schools with schools that are doing well. Education authorities should also consider publishing summary reports of how well schools are doing according to the indicators rather than individual school results. This will avoid putting undue pressure on school staff and reinforce the school improvement focus of the school quality indicators.

Recommendation 4.1.3. In the long term, consider introducing external school evaluations in all administrative units. To have a greater impact on school improvement, competent education authorities should consider developing BiH- or authority-level external school evaluations that are more comprehensive than baseline monitoring against school quality indicators. By providing more information on the strengths and weaknesses of school practices and recommendations on how to improve, such evaluations can be a credible way to support both school improvement and accountability. For example, evaluators should be completely independent to ensure integrity of the evaluation process. Other elements could include differentiated evaluation cycles in which low-performing schools are inspected more frequently, and the public reporting of individual school results. These efforts could promote greater transparency and evidence about BiH school systems.

Policy Issue 4.2. Developing the expert advisor and school leader roles.

The administrative units in this review will require strong system and school leadership to improve school quality. Pedagogical institutes and their equivalents are well-positioned to provide support to schools. However, they are understaffed and have very broad mandates. Moreover, expert advisors’ who work in pedagogical institutes have school monitoring responsibilities that sometimes conflict with their support role. At the school level, it is positive that some competent education authorities in this review plan to professionalise the school leadership role. Nevertheless, all have yet to develop key elements of professionalisation, such as school leadership standards, initial training requirements and principal appraisal processes. Furthermore, principal appointments remain vulnerable to politicisation. Competent education authorities will need to address these issues in order to develop the expert advisor and school principal roles as agents for change in BiH schools.

Recommendation 4.2.1. Strengthen the school support capacity of expert advisors. Education authorities should create dedicated school improvement positions in pedagogical institutes or their equivalent for expert advisors who will provide support to at-risk schools and help schools with self-evaluations. To ensure that expert advisors can provide sufficient support to schools, education authorities will need to address capacity constraints in pedagogical institutes and their equivalent as a matter of priority. Such measures could include providing relevant training to expert advisors, increasing staff in pedagogical institutes or partnering with non-governmental organisations (NGO) to support school improvement.

Recommendation 4.2.2. Transform the school principal role to strengthen instructional leadership. Competent education authorities will also need to introduce measures to help ensure that the most qualified school principal candidates are selected for the position. This could mean introducing new school leader certification requirements, like mandatory training, and further de-politicising the selection process by, for instance, increasing selectors’ impartiality. Principals should also have opportunities to build their instructional leadership capacity through collaborative learning activities, such as mentorship and regular appraisal processes that lead to constructive feedback. Authorities at the state or entity, canton and district level could work with an NGO to establish a school leadership body or bodies to develop these types of measures.

Policy Issue 4.3. Using regular self-evaluation to help all schools improve their practices.

Republika Srpska and West Herzegovina Canton now require all schools to conduct self-evaluations on an annual basis for development planning purposes. However, schools in other jurisdictions covered in this review do not conduct self-evaluations. All competent education authorities should introduce self-evaluation procedures to foster a culture of continuous improvement in instructional practices. This will be particularly important in BiH because resource constraints may preclude the introduction of regular external school evaluations for some time.

Recommendation 4.3.1. Encourage schools to conduct regular self-evaluations using the indicators of school quality. In the jurisdictions where school self-evaluation is not mandatory, competent education authorities should consider using the school quality indicators to help schools evaluate their own practices. These indicators would signal the key priorities and outcomes that schools should be working towards. Education authorities could deploy practices used in OECD and EU countries to ensure that schools find the self-evaluations useful for their own development rather than simply to fulfil external monitoring requirements. Such practices include helping schools to use self-evaluation results to inform their regular school development plans and giving schools the flexibility to evaluate themselves against additional indicators that are most relevant to their context.

Recommendation 4.3.2. Provide guidance and resources to help schools lead their own improvement. Competent education authorities will need to provide guidance and resources, including manuals, training and expert support from pedagogical institutes or their equivalent, to help schools conduct self-evaluations. Education authorities should also develop resources to help schools act on their self-evaluation results. For instance, authorities could work together, with APOSO’s support, to expand a new online learning platform for teachers (Chapter 3) to provide research and resources on effective school practices. Given that many schools in BiH lack resources, authorities might also consider introducing a competitive school improvement grant programme in the medium- to long-term whereby schools submit proposals for funding to support initiatives included in their school development plans. To support equity, authorities could prioritise proposals from schools that are identified as at-risk through the school quality indicator exercise, or that face difficult circumstances (for instance, being located in a poorer socio-economic area).

System evaluation supports teaching and learning by generating information on how an education system is performing, and using this information to improve policy and hold policymakers to account for progress against established policy goals.

There are many examples of individual policies within BiH that aim to improve the quality of education, such as the school quality standards in Republika Srpska or the performance-based appraisals for teacher promotion in Central Bosnia Canton. However, all competent education authorities face system evaluation challenges and limited co‑operation at the state level reduces their ability to collectively set meaningful goals and use evidence for accountability and improvement purposes. In particular, BiH does not yet have a state-level strategy that sets out priorities for school education across the country as a whole. Moreover, previous attempts at state-level initiatives, from implementing the CCC and occupational teacher standards to establishing a country-wide education information management system (EMIS), have not been met with the support and buy-in needed to have their desired impact on the education sector.

Competent education authorities could strengthen system evaluation through greater collaboration and co‑ordination at the country level, which would enable them to pool resources and share experiences. Generating richer education data to support benchmarking within and beyond BiH, and using this data to inform a more transparent and evidence-based dialogue around addressing the country’s education challenges will be an important first step. Engaging in future state-level initiatives will require a large degree of political will. Therefore the BiH Conference of Ministers of Education, which was established in 2008 with the goal of overseeing “the fundamental reform of the existing parallel education systems of BiH”, should strive to set long-term goals for the sector that extend beyond individual political mandates and help establish common ground among a wide range of stakeholders about what matters most: that all students in BiH are supported to develop their core competences.

Improving system evaluation: Three policy areas

Policy Issue 5.1. Revitalising the Conference of Education Ministers to establish a common vision for pre‑tertiary education.

It is positive that competent education authorities in BiH have already set some education goals either in their sector-specific strategies or within their broader development strategies, as this can help direct individual education systems in the country. At the same time, most competent education authorities that have set education goals lack the resources and data to translate these goals into concrete actions and monitor their implementation. Moreover, BiH currently lacks a state-level strategy related to primary and secondary schooling. Many OECD countries with decentralised education systems set high-level education goals because it can help foster collaboration among government partners and set minimum quality standards that are coherent across the country as a whole, as well as internationally. The BiH Conference of Education Ministers provides a platform for country-level co‑operation and dialogue on education, but has lost momentum and lacks a clear programme of work. Revitalising the Conference with a mandate to chart common goals for raising the quality of education in BiH could help establish a long-term and sustainable path for improvement in the wake of COVID‑19. Developing action plans and reporting on progress towards these goals can also enable BiH to make better use of donor support for education and strengthen public trust, transparency and accountability in the sector.

Recommendation 5.1.1. Establish a common, widely-approved vision and goals for pre‑tertiary education in BiH. To set a clear direction for BiH’s education systems, the Conference should establish a common, shared vision and goals for pre‑tertiary education. Using the Conference in this way can help to depoliticise the education debate in BiH and bring a renewed focus on improving student outcomes. Competent education authorities in BiH face a number of common challenges that could serve as a starting point for identifying high-level goals for the sector. For example, the Conference might choose to focus education stakeholders on improving learning outcomes in core domains, raising digital literacy and supporting school to work transitions. Setting out long-term goals that reflect shared ambitions can help reinforce BiH’s commitments to Sustainable Development Goal 4 (SDG4) and send a clear message that all citizens should benefit from quality school education.

Recommendation 5.1.2 Formulate action plans and a country-level indicator framework to monitor progress against the common education goals. To date, BiH’s country-level education strategies and laws have failed to translate into concrete change, partly due to a lack of concrete implementation plans with measurable objectives (World Bank, 2019[13]). To address this constraint, competent education authorities should formulate action plans and a country-level indicator framework to monitor progress against the common education goals. A growing number of OECD countries use these elements of system evaluation to plan out the different steps needed to achieve a long-term goal, specify responsibilities and timelines, and to define metrics to monitor progress. BiH should ensure that indicators relate to good-quality and regularly-released data. This data should link to existing international reporting requirements by using EU data definitions.

Recommendation 5.1.3 Strengthen reporting on education performance and policy. To build trust and an evidence-informed debate around education policy, competent education authorities should strengthen reporting on education performance and policy. Currently, there is no regular reporting on education system performance in BiH – yet this will be critical to build public understanding of reform. Competent education authorities should consider supporting the regular production of a State of Education report for BiH, which could provide quantitative data on the performance of different education systems in BiH, as well as qualitative information, such as snapshots of policy practices that have proved successful in different places. The Conference could also support the creation of a web platform that provides information on education policy and performance in BiH. These efforts can help promote peer-learning and collaboration among BiH education systems.

Policy Issue 5.2. Increasing efforts to produce richer education data for BiH through increased country-level co‑ordination.

Policymakers require high-quality data to ensure that policy is evidence- informed, and that good governance values such as integrity, openness and fairness are embedded into the policy cycle (van Ooijen, 2019[14]). Access to more sophisticated data can also help BiH to shift the education policy focus away from inputs (e.g. expenditure on education, the number of teachers) towards outcomes (e.g. student learning and teaching quality); thus helping decision-makers to weigh the potential of different interventions. Access to more granular data can also help policymakers to track differentiated outcomes for specific demographic groups, helping to monitor and reduce system inequities. At present, education actors in BiH do not have the type of comparable and timely data they need to conduct rigorous system evaluation and guide policy. This context also makes international reporting of education data a challenge for the BiH Agency for Statistics (BHAS).

Recommendation 5.2.1. Progressively improve country-level data governance. Promoting more alignment around internationally recognised data standards and protocols could facilitate international reporting for the BHAS while reducing the reporting burden on schools who currently report data to both their education authority and BHAS. To unlock this resource, the BHAS and BiH’s competent education authorities should work together to progressively improve country-level data governance. This is a common practice in OECD countries with decentralised education systems, such as the United States, where identifying common standards (that also align with international commitments), developing operating policies, and implementing processes for managing data have helped to improve the quality of data collection, reporting and use across states (Edfacts, 2020[15]).

Recommendation 5.2.2. Commit to participate in future cycles of international assessments. Few competent education authorities currently conduct standardised learning assessments, meaning that there is very little reliable data on learning outcomes in BiH. Limited co‑operation in this area also means that data on learning outcomes cannot be compared across BiH or at the international level. Producing data on learning outcomes is an important feature of education evaluation frameworks in most OECD countries because it provides information on the final results that an education system is trying to achieve (OECD, 2009[16]). Given that learning outcomes data in BiH is scarce and producing comparable data may remain a challenge over the immediate term, BiH’s competent education authorities should formally commit to the long-term participation in major surveys, such as PISA, TIMSS and PIRLS. This data will allow competent education authorities to set measurable policy goals, and help to review performance over time.

Recommendation 5.2.3. Build competent education authorities’ capacity to compile high‑quality data. To ensure that data governance and participation in international assessments are successful, BiH will need to invest in the capacity of competent education authorities to support and benefit from these initiatives. This can be done either through peer learning but also by ensuring that all entities and cantons have the staff capacity and infrastructures needed to manage an EMIS system. Over time, establishing an information system that compiles and stores education data at the country level - that education systems could customise for their own needs while still reporting key common data - would make it even easier to compile comparable and timely information for the indicator framework and to measure sector progress. At present, BiH is one of the few countries in Europe that does not have a functioning EMIS at the state-level.

Policy Issue 5.3. Strengthening demand for system evaluation to propel system improvement and increase accountability.

Defining common goals for education policy and generating data that can help policymakers to understand how their education systems are performing is an important first step in strengthening system evaluation in BiH. However, the country will also need to leverage available data – as well as data that could become available in the future – to build demand for using evidence to inform policy and increase accountability and transparency. Such efforts will be critical to ensure that all other efforts to improve system evaluation are sustained. While BiH’s participation in international student assessments (i.e. PISA in 2018 and TIMSS in 2019) has generated important data on learning outcomes, there remains limited domestic analysis and use of this data. This represents a missed opportunity for mutual learning. BiH also has a sizeable diaspora and development partners that could be mobilised to produce more outward-looking analysis and debate on how the country’s education systems are performing. In turn, these efforts could help build a stronger culture of education research and evaluation in BiH.

Recommendation 5.3.1. Create an international scholarship programme for research in education. There have been no concerted efforts at the BiH-level to co‑ordinate, consolidate and commission research in education, and most competent education authorities do not have the resources to do this independently. To promote the production of high‑quality research on its education systems, BiH could create an international scholarship programme for research in education. The programme could benefit from expertise and funding from international donors and be administered by APOSO as an independent, state-level body with an informed perspective on the country’s most critical policy questions. Importantly, findings from the programme should be made openly available to the public and competent education authorities could comment on the findings and how they can help inform education reforms in their system.

Recommendation 5.3.2. Establish citizens’ assemblies to provide input for planning the implementation of important reforms. Education remains a politically sensitive topic in BiH, which can create roadblocks for reform. To ensure that citizens have a say in the policies that will affect them over the long term, BiH should establish citizens’ assemblies to provide input in the planning and implementation of important reforms. This initiative could also help to strengthen trust in government partners. To ensure that participants are representative, they should be selected through a carefully designed sample and their work should be published through a regular progress report, in order to maximise transparency in the initiative.

References

[11] Branković, N. et al. (2016), MONITORING AND EVALUATION SUPPORT ACTIVITY (MEASURE-BiH) Brief Assessment of Basic Education in Bosnia and Herzegovina, United States Agency for International Development in Bosnia and Herzegovina (USAID/BiH).

[15] Edfacts (2020), Introduction to the U.S. Department of Education Data Governance.

[1] European Commission (2021), Bosnia and Herzegovina 2021 Report, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52021SC0291&from=EN (accessed on 22 February 2022).

[12] European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2018), Teaching careers in Europe: Access, Progression and Support, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

[7] Eurostat (2019), Key figures on enlargement countries 20, Eurostat, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/9799207/KS-GO-19-001-EN-N.pdf/e8fbd16c-c342-41f7-aaed-6ca38e6f709e?t=1558529555000 (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[8] GIZ (n.d.), Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) in Bosnia and Herzegovina, GIZ, https://www.giz.de/en/worldwide/57120.html (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[4] OECD (2021), Competitiveness in South East Europe 2021: A Policy Outlook, Competitiveness and Private Sector Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/dcbc2ea9-en.

[10] OECD (2020), Education in the Western Balkans: Findings from PISA, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/764847ff-en.

[3] OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en.

[16] OECD (2009), Measuring Government Activity, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264060784-en.

[9] OSCE (2020), Towards an Education that Makes a Difference, Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe.

[5] UNESCO UIS (2021), UIS database, http://data.uis.unesco.org/ (accessed on 13 October 2021).

[14] van Ooijen, C. (2019), A data-driven public sector: Enabling the strategic use of data for productive, inclusive and trustworthy governance, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/09ab162c-en.

[2] World Bank (2020), World Development Indicators, World Bank, Washington DC, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

[6] World Bank (2019), Bosnia and Herzegovina: Review of Efficiency of Services in Pre-University Education, World Bank, Washington DC, http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/719981571233699712/pdf/Bosnia-and-Herzegovina-Review-of-Efficiency-of-Services-in-Pre-University-Education-Phase-I-Stocktaking.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2020).

[13] World Bank (2019), Bosnia and Herzegovina: Review of Efficiency of Services in Pre-University Education - Phase 1. Stocktaking, https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/719981571233699712/pdf/Bosnia-and-Herzegovina-Review-of-Efficiency-of-Services-in-Pre-University-Education-Phase-I-Stocktaking.pdf.