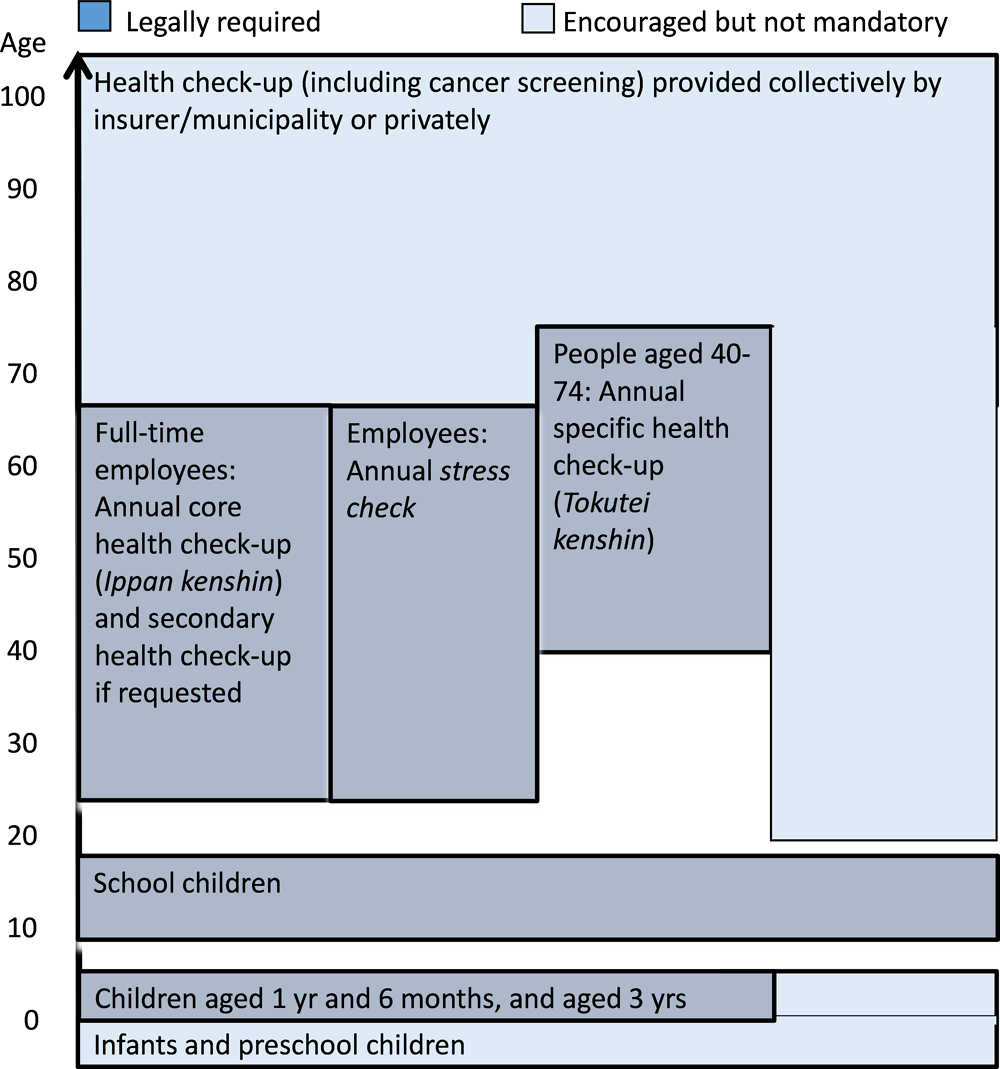

In recent decades, Japan has increased its reliance on health check-ups and tries to improve population health through early detection of diseases. Based on health check-up results, Japan also aims to promote individual’s effort to manage their own health condition by preventing the onset or severity of diseases through better lifestyles. Now, routine health check-ups are available to almost all segments of population throughout their life course. These secondary prevention strategies are unique in the OECD and their impact is not well understood partly due to its health information system. Considering the tight fiscal situation which is likely to continue due to population ageing, Japan needs to review its secondary prevention strategies and focus on developing and implementing effective and economically sound secondary prevention policies.

OECD Reviews of Public Health: Japan

Chapter 3. Health check-ups in Japan

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

3.1. Introduction

Japan relies significantly on population-based health check-ups and tries to improve population health through early detection of diseases. Based on health check-up results, Japan also aims to promote individuals’ efforts to manage their own health condition(s) by preventing the onset or severity of diseases through better lifestyles. To illustrate its policy priority, for instance, in the central government’s Smart Life Project, which aims to engage a wide range of stakeholders to take part in health promotion activities, a promotion of health check-up participation is one of the four key target areas.

Along with people’s attention to hygiene and traditional diet which is balanced in nutrients, health check-ups are considered to have played an important role in improving the population health over the past decades(Ikeda at al., 2011), and this has led Japan to have a strong policy focus on developing population-based health check-ups and expanding their coverage.

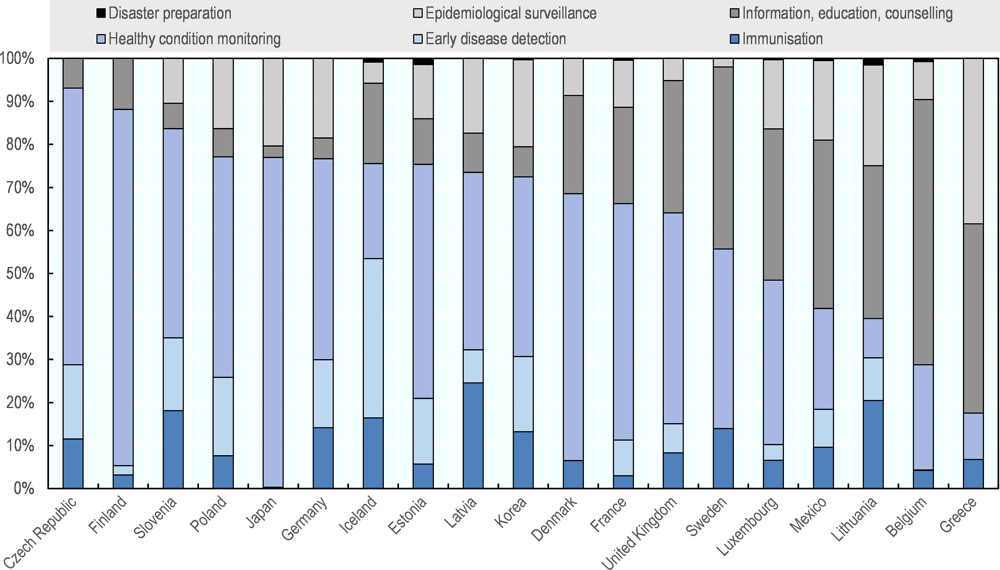

The coverage of health check-up items and target population(s) have expanded over the past few decades, and routine health check-ups are now available to almost all segments of population throughout their life course. There are legally required health check-ups such as health check-ups for infants and preschool children, an annual health check-up for school children, an annual health check-up for full-time employees, annual stress test for employees, and an annual specific health check-up for people aged between 40 and 74 to prevent lifestyle-related diseases (Figure 3.1). There are also a number of other health check-ups and cancer screening which are not legally required but recommended to provide by municipality or insurer.

This chapter describes, firstly, the health check-ups which are legally required in Japan, and then goes on to describe health check-ups and cancer screening, which are encouraged but are not mandatory. Based on the international evidence, the last section lays out a set of recommendations to support Japan in further developing its secondary prevention policies.

Figure 3.1. Health check-ups are available routinely for almost all segment of population in Japan

3.2. Several health check-ups are legally required in Japan

3.2.1. Health check-ups for infants and preschool children have a long history in Japan

Japan started health check-ups for children aged three years old in 1961, and the health check-up for children aged one and a half years old was introduced in 1977. These check-ups are provided either collectively by the municipality or individually by commissioned health care providers. The municipal government is required to organise and fund these health check-ups and they are provided free of charge to these children. Health check-up items are standardised nationwide and the first health check-up includes physical measurement, assessment of nutritional status, oral health, and developmental problems related to physical and mental health and vaccination history. During the health check-up at age 3, vision, ear, nose and throat are also examined. To monitor child growth, additional health check-ups are available in most municipalities for infants aged 3-4 months and 9-10 months, and many municipalities also provide health check-ups for infants and preschool children in other age groups. Municipalities are also required to provide a free health check-up to children about half a year before entering primary school (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW), 2015a; MHLW,2015b; Japan Society of School Health, 2017). Beside health assessment and early detection of abnormality, these health check-ups for infants and preschool children also aim to provide educational/consultation opportunities for their parents, and to screen for child abuse/neglect.

In the similar vein, many other OECD countries provide free health check-ups for infants and preschool children. In some countries including Belgium, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Italy, Korea, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Slovenia, Sweden and the United Kingdom (England), health care including health check-ups is provided free of charge to infants and preschool children (Ferré et al., 2014; Lai et al., 2013; Paris et al., 2016).

Access to health check-ups for preschool children is high in Japan, and nearly all infants and preschool children undergo health check-ups which are required legally. The uptake continued to increase in recent years and it reached 96.4% for 1.5-year old children and 95.1% for 3-year-old children in 2016 and they are equally high across municipalities (MHLW, 2018c).

Compared to other OECD countries, available data suggest that the overall health of infants and preschool children in Japan is relatively good and continues improving. Infant mortality rate has fallen rapidly from 30.7 per 1 000 live births in 1960, and in 2016 infant mortality was 2.0 per 1 000 live births, the lowest in the OECD after Iceland (1.7 (three year average between 2014 and 2016)) and Finland (1.9). Similarly, the number of under-five deaths was 40 per 1 000 live births in 1960, but went down to below 3 per 1 000 in 2016, one of the lowest in the OECD after Finland, Iceland, Luxembourg and Slovenia (all at around 2 per 1 000) (UN Inter-agency Group for child Mortality Estimation, 2017). It is believed that together with progress on medical technology, health check-ups for infants and preschool children have contributed to children’s improved health outcomes (MHLW, 2014).

3.2.2. School children usually undergo an annual health check-up in Japan

At Japanese schools in the primary, lower secondary, upper secondary and tertiary levels, a health check-up is provided to students by professionals such as school doctors. Schools appoint these health professionals from those recommended by medical associations. According to the School Health and Safety Law’s enforcement regulations, the check-up must be provided every year to students at the primary and lower secondary levels and to first-year students in upper secondary and tertiary levels (e-Gov, 2018). However, at least some upper secondary and tertiary educational institutions provide additional health check-ups to students in other years.

Legally required health check-ups for students include a standardised core set of health check-up items (Box 3.1). The municipal education board funds health check-ups provided to students who are newly entering a school but once they are enrolled, schools pay for the health check-ups provided to their students (e-Gov, 2018; MHLW, 2015). Additional health check-up items are sometimes available but the content of health check-ups for students is generally similar across educational institutions.

Box 3.1. The standardised health check-up items for students are provided across schools

Health check-up items for school children at the primary, lower and upper secondary levels include the following physical examinations, sample analyses and health consultations:

Height and weight,

Nutritional status,

Diseases and abnormalities related to spine and chest,

Vision and hearing test,

Diseases and abnormalities related to eye,

Diseases of ear, nose and throat, and skin,

Diseases and abnormalities related to teeth and mouth,

Tuberculosis (TB),

Diseases and abnormalities related to heart,

Urine, and

Other diseases and abnormalities.

Since the health check-up must be undertaken within a limited time, preparation and collaboration between different professionals including teachers and health care providers is a key for its smooth operation.

For first-year students in tertiary education, most of the items above are examined but several items including vision and hearing test and urine test are not required.

In addition, educational institutions at upper secondary and tertiary levels need to provide a chest X-ray for TB to first-year students in view of controlling TB infection which is relatively high in Japan (15 per 100 000 population in Japan, higher than the OECD average of 12 per 100 000 population in 2017, see Chapters 1 and 4) (e-Gov, 2018).

Source: e-Gov (2018), Education Health and Safety Act, http://elaws.e-gov.go.jp/search/elawsSearch/elaws_search/lsg0500/detail?lawId=333M50000080018#B.

Students or their parents are notified of health check-up results and if the results suggest that students have any diseases or abnormalities, they are recommended to seek follow-up diagnosis and/or health care. For example, a detailed examination including a chest X-ray is recommended if students (other than first-year students at upper secondary and tertiary education levels, for which this examination is compulsory) are suspected to have TB based on the consultation during school health check-up (MEXT, 2011; MEXT, 2015). Health check-up results are kept either in written or electronic form at the school for five years, and they are not linked with other health care data such as health care claims and medical records. When a student transfers to another school, their results are sent from the principal of the previous school to the principal of a new school.

Although many school-based interventions are available across OECD countries (Chapter 2), health check-ups are not generally provided at school in the OECD (Sassi, 2010). Instead of a school health check-up, many OECD countries provide health check-ups in primary care settings or try to assure access to primary care to children with either no out-of-pocket payment (e.g. the Czech Republic, Estonia, Portugal, Slovenia, Sweden and England in the United Kingdom) or reduced out-of-pocket payment (e.g. Australia, New Zealand) (Paris et al., 2016). Nonetheless, a health check-up for school children is provided in a few other OECD countries such as Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, the Netherlands and Norway. However, compared to Japan, most of these countries provide check-ups less frequently and the coverage of check-up items are narrower. For example, while a health check-up is also provided annually in Austria, it is provided less frequently in other countries such as Belgium (once in primary school and twice in secondary school in Flemish and French regions), Denmark (a minimum of two health check-ups for students in primary and secondary school) and the Netherlands (at age 5, 10 and 13). Some countries include a dental check as part of health check-ups as done in Japan, but several countries including Sweden, and Switzerland (in which basic health insurance does not generally cover dental care) provide only a dental check to students (Anell et al., 2012; Busse and Blümel, 2014; De Pietro et al., 2015; Gerkens and Merkur, 2010; Hofmarcher and Quentin, 2013; Kroneman et al., 2016; Olejaz et a., 2012; Paris et al., 2016; Ringard et al., 2013; Sigurgeirsdóttir et al., 2014; Vuorenkoski et al., 2008).

In Japan, the uptake of health check-ups among schoolchildren covers nearly 100% of educational institutions. The high uptake has been achieved through well-established, organised delivery, high public awareness and free access. School health check-ups provide equal opportunities for students across different socio-economic backgrounds to have contact with a health care professional which some of them may not otherwise have.

Over time, health outcomes of Japanese schoolchildren have improved but potential links with health check-ups are not known. For example, the probability of dying at age 5-14 years was 1.7 per 1 000 children in 1990 but reduced to 0.8 in 2016 in Japan, which is one of the lowest in the OECD after 0.5 in Denmark and Luxembourg, 0.6 in Norway, and 0.7 in France, Italy and Switzerland (UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation, 2017). Among children at age 12, the average number of decayed, missing and filled teeth was 4.3 in 1990 but it fell to 0.9 in 2015, also one of the lowest in the OECD after Denmark (0.4), Germany (0.5), Luxembourg (0.4) and Sweden (0.7) (OECD, 2017). However, since health check-up data are not systematically linked with health care claim data and a number of other health promotion activities take place at school (see Chapter 2), it is difficult to assess the extent to which health check-ups have contributed to improved health outcomes among school children in Japan.

3.2.3. Employers are required to provide a core health check-up annually to full-time employees

Under the Industrial Safety and Health Law in Japan, since 1972, employers have been obliged to provide a core health check-up (Ippan kenshin) to their full-time employees at the time of hiring and every year, for free, and these employees are also obliged to undergo this health check-up. This health check-up aims to prevent worsening of employee’s health due to work, and based on check-up results, employers must find ways to improve working environment of the employees who are identified to have health issues (MHLW, 2013).

Full-time employees here refer to those who have an employment contract longer than one year or who are expected to work more than one year, and who work longer than three quarters of average weekly working hours among regular employees within the same job category (MHLW Tokyo Labor Bureau, 2017). The MHLW recommends that employers also provide a core health check-up to part-time employees who work more than half of the weekly working time of full-time employees, but this is not legally required (MHLW, 2015c), so these employees often do not have access to such services.

The core health check-up needs to include a standardised set of health check-up items (Box 3.2). According to the Industrial Safety and Health Law, doctors can decide to exclude some of these items based on certain information collected during the medical consultation in the beginning of the core health check-up. For instance, a chest X-ray, which is used to detect TB and other chest diseases (MHLW, 2005) should be provided at age 20, 25, 30 and 35, but can be excluded in other years among full-time employees under 40, as long as the employee does not work at a place which is required to provide a regular examination of TB under the Infectious Disease Act, or the Pneumoconiosis Act (MHLW, 2013).

Box 3.2. The standard items for the core health check-up (Ippan kenshin) are set and used nationwide

The standard items for the core health check-up include the following:

Medical consultation including medical history and working condition,

Assessment of subjective and objective symptoms

Height, weight, abdominal circumference, vision, hearing,

Chest X-ray, sputum test,

Blood pressure,

Anaemia test (red blood cell, haemoglobin),

Liver function (GOT, GPT, γ-GTP),

Blood lipid (HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, blood serum triglyceride),

Glucose,

Urinary sugar, uric protein, and

Electrocardiogram

The standard set of health check-up items at the time of hiring is generally the same as that of the core health check-up.

Based on doctor’s discretions, the following items can be excluded as part of a routine core health check-up for full-time employees: height, abdominal circumference, blood lipid (HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, Creatinine), liver function (GOT, GPT, γ-GTP), anaemia test (red blood cell, haemoglobin), electrocardiogram and a chest X-ray. Specific criteria which are often related to age are laid out in guidelines for core health check-up and they need to be fulfilled to exclude the above-mentioned check-up items (MHLW, 2013a).

Source: MHLW (2013a), Roudou anzen eisei hou ni motozuku kennkoushindan wo jisshi shimashou (Health check-ups based on occupational health and safety act), http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-11200000-Roudoukijunkyoku/0000103900.pdf.

In view of reducing worker’s accidents and deaths related to cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases, which are one of main causes of deaths in Japan (Chapter 1), the core health check-up (Ippan kenshin) is used to provide a further health check-up specific to these diseases (Niji kenkou shindan). This secondary health check-up for cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases started in 2001 for full-time employees who are identified to have high levels of associated risk factors (e.g. blood pressure, glucose, blood lipid, and abdominal circumference or BMI) based on core health check-up results. The secondary health check-up is also available for employees based on the discretion of occupational health doctors (see Chapter 1). Since specific thresholds for risk factors are not set at a national level, different thresholds may be used across providers when making assessment on the worker’s eligibility or need for the secondary health check-up. During the secondary health check-up, the following items are examined: blood lipid and glucose levels at the time of fasting, haemoglobin A1c, a stress electrocardiogram or an echocardiography, a carotid ultrasonography and microalbumin measurement. Based on the results of secondary health check-up, face-to-face health guidance focusing on nutrition, physical activities and lifestyles including smoking, drinking and sleeping can be provided by a doctor or nurse with the aim of reducing risk factors for cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases. Both the secondary health check-up and subsequent health guidance are provided free of charge upon request by employees, and the central government covers the entire cost (MHLW, 2018a).

For employees who work in hazardous conditions, employers need to provide an additional health check-up which is specific to the working environment, at the time of hiring and before the employee is assigned to start working in a hazardous environment, regardless of the employment contract type and the number of weekly working hours. Employers also need to provide this health check-up to all employees working in hazardous conditions every six months or more frequently to monitor their health conditions related to the working conditions.

Looking outside of Japan, only a few OECD countries, including Finland, France, Italy, Korea and Slovenia, require employers to provide health check-ups for their employees but the interval is longer and the eligible group is often more targeted in these countries compared to Japan. For instance, in France, since 2017, in order to rationalise the use of occupational health doctors whose number is decreasing, and to provide care effectively to workers at risk (Assemblée Nationale, 2016), a health check-up for employees has been provided with a maximal interval of five years (previously every two years). In France there is an exceptions for certain employees such as those with disability and those working night shifts – who are required to undergo health check-ups with the maximal interval of three years – and high-risk employees who usually need to be seen by an occupational health doctor for follow-up examination every four years (Gmeinder et al., 2017). In Korea, a health check-up is required every two years for employees aged 40 and over (Chu, 2017). In Finland and Italy, only employees working in high risk conditions undergo a routine health check-up (Albreht et al., 2016; Ferré, 2014; Vuorenkoski et al., 2008). For example, in Finland a targeted health check-up is provided between every year and every three years depending on the level of risks the worker is exposed to (Finnish Ministry of Justice, 2002).

In Japan, access to and uptake of a core health check-up is generally high but it varies by the size of enterprise and the type of employment contract. According to the latest data available, in 2012 91.9% of employers provided a core health check-up. However, the implementation rate of core health check-ups varies across employers. While all large enterprises with over 1 000 employees provided core health check-ups to their full-time employees, 89.4% of employers with between 10 and 29 employees provided them to their full-time employees. For part-time workers who are eligible for a core health check-up, the implementation rate was over 90% among enterprises with over 1 000 employees while it was about 50% among enterprises with between 10 and 29 employees. On the employees’ side, uptake is also generally high and 88.5% of all employees underwent core health check-ups. However, this uptake also varies by the size of employer and it is low among those working in small enterprises. The 11.5% of employees who did not undergo a core health check-up were mainly those who were not eligible for a core health check-up including part-time employees, dispatched workers and employees with temporary and daily contracts (MHLW, 2012). With regards to the secondary health check-up for cerebrovascular and cardiovascular diseases and subsequent health guidance, the share of employees who underwent them is not known but considered very low.

It has been suggested that the current share of employees who undergo a core health check-up is lower than that in 2012 because labour market dualism has been advancing in Japan. The share of employees with irregular employment contract has increased steadily and they accounts for 37.3% of employees in 2017, up from 33.5% ten years earlier (MHLW, 2018f). In the context in which employment patterns and contracts continue diversifying, employees who are not eligible to access core health check-ups may continue to increase.

Although core health check-ups have been implemented over the past 40 years and continue to evolve to reflect medical progress, their impact on the health of workers is still not well understood. It is understood that core health check-ups do not always lead to early health care interventions among workers with identified health issues. Results of core health check-ups are not linked with health care claims data, so it is still difficult to undertake a comprehensive impact assessment. However, according to the latest data available, in 2012, over one third of full-time employees who were considered to be in need of follow-up examinations and/or health care based on core health check-up results did not actually go on to seek the care they needed. The tendency towards not seeking follow-up care is more pronounced among young workers, while the share of workers who actually sought follow-up care was over 70% among the employed aged 60 and over who were identified to be in need of care based on the results of a core health check-up. The share of those in need of follow-up care who actually sought care was about half among the employed aged between 20 and 29 (MHLW, 2012). Although core health check-ups aim to prevent worsening of employee’s health due to work, it is not clear that the results always steer workers towards appropriate follow-up and/or early early treatment.

3.2.4. Employment-based insurers needs to provide an annual stress test to employees

Mental health is one of the important health concerns in Japan (see Chapters 1 and 2). In 2016, 59.5% of people working in enterprises with more than 10 regular employees reported feeling significant stress in relation to their current work or their professional life. Among workers excluding dispatched workers, 0.4% had a sick leave longer than one month due to mental ill-health and 0.2% quit their job due to mental ill-health (MHLW, 2016a). In recent years, the number of requests for a compensation for work-related accidents due to mental ill-health has been increasing (MHLW, 2017a).

In order to prevent mental illnesses and reduce their burden among employees in Japan, employers with more than 50 employees are obliged to evaluate the stress level of their workers (stress check) once a year without out-of-pocket payment. Before the national rollout, the test was first introduced by the National Federation of Industrial Health Organization in Japan to its affiliated employers, and the central government then implemented this initiative nationwide in 2015. This stress test measures employees’ mental health through an online questionnaire which was developed based on the questionnaire designed by the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health in the United States. The questionnaire aims to make employees aware of their stress level so that they can try to prevent mental health problems, and also aims to prompt employers to improve the work environment based on stress check results. This test needs to be provided not only to full-time employees but also to other employees with shorter working hours, although dispatched workers and temporary workers with a short employment contract are excluded. If the results of stress check suggest a high level of stress, an employee can request to undergo an associated medical consultation.

The nationwide implementation of annual stress test is unique in the OECD. In order to tackle mental health issues at work, a number of other OECD countries also oblige employers to evaluate, prevent and control psychosocial risks at work. However, in these countries, pressure from employee representatives and high absenteeism has often prompt employers to take action to handle psychosocial workplace risks and job strain (OECD, 2015a). However, in Japan, each of the employees working for employers with more than 50 employees has an opportunity to flag a case of job strain through stress test, so it is possible that many more cases with psychosocial risks and job strain can be recognised in Japan than in other countries.

The implementation and uptake of stress test are high in Japan, although there are some variations. In 2017, on average, 82.9% of employers provided stress check and on average, about 78% of employees underwent the test. The implementation rate of the stress check was lower among small enterprises; 99.5% of large enterprises provided a stress check in 2017, but a share of employers with between 50 and 99 employees provided the test was 78.9% even though it is obligatory for them to provide annual stress tests. The uptake of the stress check is equally high (almost 80%) across employers with different sizes (MHLW, 2017b), suggesting a high demand for evaluating mental health and good accessibility to the online stress check among workers across different employers in Japan.

It is still early to evaluate the effectiveness of the stress check, but available data suggest that it has sometimes been used to change the working environment in view of improving mental health of workers. In order to protect employees’ privacy, results of stress checks are not shared with employers unless requested by employee. Analyses of these data by a third party are encouraged, and these data are analysed at an aggregated level to assure privacy protection without identifying a specific employee with mental health issues. Among employers who conducted a stress check, 78.3% had the results analysed by a third party in 2017, a substantial increase from 43.8% a year before (MHLW, 2017b; MHLW, 2017c). It is possible that these employers who had their data analysed are also more willing to improve working conditions for the employees than other employers, but in 2016, 69.2% of employers reported to have used these analytical findings. They are usually used to review division of work among employees, and human resource structure and allocation, to provide trainings or training information to managers, and to undertake further investigations and discussions at the occupational health committee (MHLW, 2017c).

However, a stress check does not generally lead workers who are identified to have mental ill-health to seek associated mental health care. The share of employees who requested to undergo an associated medical consultation which is provided after stress check is very small (0.6%) (MHLW, 2017b). This may be due to the information-sharing rule that are applied to this medical consultation; if an employee requests to seek an associated medical consultation, the doctor who provided this medical consultation submits an assessment report to the employer, and if the report includes suggestions to modify the specific employee’s working environment, the employer needs to respect them. Hence, if employees do not wish their employers and managers to know about their mental health issue or consider it unnecessary to have their own working environment changed, they do not request to undergo the associated medical consultation.

As early intervention and effective treatment are important for mental illnesse (McDaid et al, 2017), it is worrying that almost all employees with mental health issues do not follow this consultation, but instead of this associated consultation, it is possible that at least some of them seek mental health care provided elsewhere as this way, their employers and managers will not usually notice their use of mental health care. Within the current health information system, however, it is not possible to know the share of those who sought mental health care elsewhere among those who were identified to have a high stress level through stress check.

3.2.5. The specific health check-up to tackle lifestyle-related diseases is provided annually to people aged 40-74

In view of reducing the prevalence of lifestyle-related diseases including cancer, cardiovascular diseases and diabetes, which account for a high disease burden (Chapter 1), Japan introduced the specific health check-up (Tokutei kenshin) to the population aged between 40 and 74 in 2008. The specific health check-up also aims to provide opportunities for individuals in this age group to re-evaluate and improve their lifestyle. All insurers in the Japanese health system (Box 3.4) are obliged to provide a specific health check-up to people in this age group every year as they are considered to have higher risks of developing lifestyle-related diseases. Insurers need to provide a nationwide standard set of health check-up items as shown in Box 3.3. The employees aged between 40 and 74 who undergo a core health check-up (Ippan kenshin) do not need to duplicate the examination of the same health check-up items.

Based on the check-up results, specific health guidance (Tokutei hoken shidou) is provided to those who are identified as having high risk of developing lifestyle-related diseases. Depending on the level of risk factors, there are two types of specific health guidance. For both types, during the first consultation (either an individual interview for more than 20 minutes or a group interview with less than 8 people for over 80 minutes), health care professionals including a doctor, nurse and nutritionist provide an advice for improving lifestyle, and subsequently an action plan is developed for each participant together with a doctor, public health nurse and dietitian. Individual participants’ progress is monitored either by a face-to-face interview, telephone interview or by e-mail. The difference between the two types of health guidance includes the monitoring interval and the content of the action plan (Box 3.3) (MHLW, 2018b).

Box 3.3. Specific health check-up items and criteria for specific health guidance are standardised nationwide

The specific health check-up, Tokutei kenshin, which targets people aged between 40 and 74, consists of a medical consultation which collects information including medical history and smoking habits, and examinations of the items below (Table 3.1). The standard set of core health check-up items for full-time employees usually includes most of the items required by specific health check-ups, so instead of conducting the same examinations twice, relevant results from core health check-up (Ippan kenshin) are usually used for their specific health check-up.

Table 3.1. Specific health check-up items

|

. |

Items |

|---|---|

|

Medical consultation |

|

|

Physical measurement |

BMI, abdominal circumference, physical examination |

|

Blood pressure and urine |

blood pressure (contraction and diastolic phases), urinary sugar and uric protein |

|

Blood test |

Neutral fat, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol Glucose or HbA1c Liver function (GOT, GPT, γ-GTP) |

|

Other examinations if doctor considers necessary |

Creatinine, electrocardiogram, fundus examination, anaemia test (red blood cell, haemoglobin, hematocrit) |

Source: MHLW (2018b), Hyoujuntekina kenshin hoken shidou programme – heisei 30 nendo ban (Standard health check-up and health guidance programme – 2018), http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10900000-Kenkoukyoku/00_3.pdf.

People with risks of developing lifestyle-related diseases are invited to undergo one of the two types of specific health guidance. The criteria included in Table 3.2 are used to identify these people. People with high risks of developing lifestyle-related diseases are invited to an intensive health guidance (sekkyokuteki shien). During the first consultation, an action plan to improve lifestyle habits is developed for each participant. Based on this plan, each participant is monitored on his/her lifestyle changes and regular health counselling is provided to promote healthy lifestyle using different means, such as face-to-face individual or group consultation, and telephone or e-mail consultation. After a number of monitoring and counselling, the final assessment on each participant’s progress is made and this usually takes place after six months since the development of action plan. On the other hand, people with lower risks of developing lifestyle-related diseases are asked to participate in motivational health guidance (doukizuke shien). Again during the first consultation an action plan is developed for each participant. The participant follows this plan on their own and the progress is assessed after six months. In order to take account of the concerns over quality of life, the elderly receive motivational health guidance instead of intensive health guidance even if they have high risks of developing lifestyle-related diseases.

Table 3.2. Eligibility criteria for specific health guidance

|

Abdominal circumference/BMI |

Number of following risks: Blood glucose (Glu ≥100mg/dl when fasting, HbA1c≥5.6% (NGSP)) Fat (Neutral fat≥150mg/dl or HDL< 40mg/dl), Blood pressure (≥130mmHg (contraction phase) and ≥85mmHg (diastolic phase)) |

Smoking |

40-64 yrs old |

65-74 yrs old |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Abdominal circumference ≥85 cm (men) ≥90cm (women) |

More than two |

Intensive health guidance |

Motivational health guidance |

|

|

One |

Yes |

Intensive health guidance |

Motivational health guidance |

|

|

No |

Motivational health guidance |

Motivational health guidance |

||

|

Abdominal circumference <85 cm (men) >90cm (women) and BMI≥25 |

Three |

Intensive health guidance |

Motivational health guidance |

|

|

Two |

Yes |

Intensive health guidance |

Motivational health guidance |

|

|

No |

Motivational health guidance |

Motivational health guidance |

||

|

One |

Motivational health guidance |

Motivational health guidance |

Source: MHLW (2018b), Hyoujuntekina kenshin hoken shidou programme – heisei 30 nendo ban (Standard health check-up and health guidance programme – 2018), http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/06-Seisakujouhou-10900000-Kenkoukyoku/00_3.pdf.

Several OECD countries have health check-ups for chronic conditions but compared to Japan, they are more targeted, the interval of health check-ups is less frequent and they are sometimes provided by health care professionals other than doctors. In Australia, for example, primary health physician can provide health assessment for people who are at risk of developing a chronic disease. This assessment is provided to people aged between 45 and 49 once if they have at least one risk factor (lifestyle habits or a family history) for developing a chronic disease such as type 2 diabetes or heart disease. The assessment is also provided to people aged 75 and over with an interval of 12 months or longer (The Department of Health, 2014; The Department of Health, 2016). In Estonia, health check-ups and guidance are provided by family nurses for people aged between 40 and 60 with hypertension or diabetes (Lai, 2013), and in 2007, Korea introduced the National Screening Program for Transitional Ages, targeting people at age 40 and 66 (Kim et al., 2012). In England, the NHS Health Check was introduced for people aged between 40 and 74 in 2009 and an invitation letter is sent every five years to those who do not already have diabetes, heart disease, or kidney disease or have not had a stroke, in order to screen them for the risk of developing chronic conditions including heart disease, stroke, kidney disease, type 2 diabetes, or dementia (available only for those above 65 and above). This check-up is often undertaken by a nurse or health care assistant (Gmeinder et al., 2017; NHS, 2017).

Although increasing, the uptake of specific health check-ups in Japan is much lower than the national target of 70% and varies across insurers and between genders. The uptake has increased from 39% in the introduction year of 2008 but in 2016 it was still 51.4%. While uptake was as high as 76.7% for Mutual Aid Associations for civil servants and 75.2% for insurance associations of large companies, uptake was low at 36.6% on average across municipality-based insurance schemes. Uptake among those insured by insurance associations of small and medium-size enterprises is also low at 47.4%, although this may be underreported due to challenges in transferring data. Uptake is also low among women aged between 40 and 64 compared to men in the same age group but the gender trend is reversed among those aged 65 and over (MHLW, 2016b).

According to the data collected through specific health check-ups, the prevalence of lifestyle-related diseases has decreased among participants, particularly among female participants in recent years. The share of people with risk factors for developing lifestyle-related diseases has declined from 19.9% of participants in the introduction year of 2008 to 17.0% in 2016. In 2016, the share of those who were identified as being at risk of developing lifestyle-related diseases was high among men in their 40s and early 50s (almost 30%) while the share was much lower among women across age groups (below 10%) (MHLW, 2016c). Specific health check-ups have been monitored in Japan based on the data collected but these data alone are not enough to evaluate the effectiveness in reducing the lifestyle-related diseases among the target population. For example, the prevalence of lifestyle-related diseases among non-participants is not known, and it may be possible that the uptake of specific health check-ups is low among people with high risks of developing lifestyle-related disease.

Box 3.4. Health insurers in the Japan health system

In Japan, there are over 3 000 employment- and municipality-based health insurance schemes and each individual is covered by one of these publicly funded insurance schemes.

People who are employed with a full-time employment contract at a company and their dependents are generally covered by employment-based health insurance. There are numerous forms of employment-based insurance. Large enterprises sometimes have their own insurance association, or form an insurance association together at the sector or industry levels. These insurance associations are called Society-Managed Health Insurance (Kenpo kumiai) and they are usually part of the National Federation of Health Insurance Societies (Kenporen) which covers about 30 million insured people. On the other hand, many small and medium-size enterprises are part of the Japan Health Insurance Association (Kyoukai Kenpo) which has about 39 million insured people. Public servants at the central and local governments are part of Mutual Aid Associations.

In addition, the National health insurance which is organised at the municipality level (Kokuho) covers those who are not covered by employment-based insurance. Individuals covered by municipality-based insurance include those who are self-employed, not employed, retired aged below 74 and working with irregular employment contract. Disadvantaged people who receive livelihood subsidies are also covered by this insurance without paying premiums. Prior to 2008, the elderly aged 75 and over were also covered by the municipality-based insurance, but since 2008 the health insurance fund has been organised at the prefectural level in order to have a separate financing mechanism to pay for the growing health care spending among the elderly, and this insurance fund receives financial support from different health insurance schemes and tax transfer.

Individuals can also enrol with private health insurance on a voluntary basis. Private health insurance is either complementary to the publicly funded health insurance which are described above, by covering all or part of the residual costs not otherwise reimbursed, or supplementary by covering additional services such as a private room at hospital not at all covered by the publicly funded scheme.

With regards to specific health guidance, the completion rate is very low. Although increased from 7.7% in 2008, only 18.8% of those who were invited to follow specific health guidance based on specific health check-up results completed it in 2016. Among the people covered by municipality-based insurance, the completion rate is higher among those covered by smaller municipalities’ insurance, but among those covered by employment-based insurance, it is higher among those covered by insurance for larger enterprises and civil servants. Between the two types of health guidance, completion was lower among those who needed to follow intensive health guidance (7.9%) compared to others who needed to undergo motivational health guidance (10.9%). Disaggregated by age group, the completion rate of specific health guidance was lower among the young (15.6% among those between 40 and 44 compared to 28.1% among those aged between 70 and 74) (MHLW, 2016b).

Some evidence shows that the specific health guidance had some positive impact on lifestyle changes among participants, at least for a short term. A study following participants who completed specific health guidance in 2008 for five years found that their abdominal circumference, weight, blood glucose level, and neutral fat levels generally improved. For example, among those who participated in specific health guidance in 2008, over the following five years neutral fat fell between 29.55mg/dl and 36.23mg/dl for male participants and between 26.27mg/dl and 31.79mg/dl for female participants, and blood pressure (contraction phase) fell between 0.63mmHg and 2.13mmHg for male participants and between 2.65mmHg and 3.24mmHg for female participants. All participants also had a reduction of abdominal circumference and weight over the five years. However, the level of blood glucose did not decreased among all participants and after 5 years the level for male participants ranged between 0.01% lower and 0.11%, higher than the blood glucose level in 2008, and blood glucose levels for female participants ranged between 0.04% lower and 0.08% higher than the initial level (MHLW, 2016d). It may be possible that those who completed specific health guidance in the introduction year were highly motivated to change their lifestyles, and it is not clear whether such findings can be generalised for participants who completed specific health guidance in recent years.

Recently, the prevalence of diabetes has been decreasing, but the association of this trend with specific health check-ups and guidance is not clear. According to the National Health and Nutrition Survey, the share of people who were suspected of having diabetes (refers to people who reported to be under diabetes treatment or to have a high measured level of HbA1c (above 6.5%)) and potentially developing diabetes (refers to people with a high measured level of HbA1c equal to or higher than 6.0% and below 6.5%) has declined from 25.6% in 2007, a year before the introduction of specific health check-up and guidance, to 24.2% in 2016, despite the continuing population ageing (MHLW, 2017d). However, since the data cannot be analysed separately for those who had undergone specific health check-up and guidance and those who did not, the impact of specific health check-up and guidance is not known.

While evidence on effectiveness is still limited, in recent years Japan has intensified efforts to increase the uptake of specific health check-up and guidance. Financial incentives have been made available to insurers. In Japan, the elderly health insurance scheme receives financial support from other health insurance schemes (see Box 3.4). Since 2013, financial incentives have been given based on the level of uptake of specific health check-up and guidance among the insured; while those with low uptake are required to give more financial support to the elderly health insurance, those with high uptake pay less. In addition, in 2018, the financial penalty was expanded to encourage Society-Managed Health Insurance Associations and Mutual Aid Associations with low uptake to improve uptake (MHLW, 2017e). Moreover, to facilitate and improve access to specific health guidance, since 2017, instead of face-to-face consultation, a tele-consultation has been allowed as the first consultation of health guidance, and starting in 2018 the first consultation can be provided on the same day as when a specific health check-up is provided to those who are likely to need specific health guidance even if all check-up results are not yet available. Some requirements for lifestyle change were also modified and beside current health status, progress over time is being monitored in order to provide more personalised specific health guidance and to improve its effectiveness.

3.3. Provision of other health check-ups including cancer screening is also encouraged

3.3.1. Additional health check-ups delivered by municipality vary across regions

The MHLW recommends that regional governments provide additional health check-ups, beyond those for infants and preschool children and specific health check-ups which they are required to provide. It is recommended that municipalities provide additional health check-up items to their residents younger than 74 and the health insurance organised at the prefectural level (see Box 3.4), and municipalities are encouraged to provide a health check-up to the residents older than 75. The MHLW also recommends a check-up for osteoporosis for women aged 40, 45, 50, 55, 60, 65 and 70, an examination for periodontal disease for people aged 40, 50, 60 and 70, and tests for hepatitis B and C for those aged 40 and over (MHLW, 2015b). The majority of municipalities provided check-ups for periodontal disease (64.5%) and osteoporosis (62.3%) in 2016 (MHLW, 2018c). The MHLW also recommends that municipalities provide cancer screening; this is described in detail in the next section (Section 3.3.2).

The central government also recommends that municipality and municipality-based insurance provide additional health check-ups. In order to improve the health of residents, as laid out in regional health promotion plan (Chapter 2), municipalities can introduce different public health interventions and many of them consider health check-ups as important public health intervention in their regions. Across municipalities, the content and specific target population of health check-ups for younger people varies depending on different factors including specific population needs and financial situations. For example, Arakawa, one of 23 cities in the Tokyo prefecture, has a health check-up for lifestyle-related diseases among those aged between 35 and 39, which also includes a mental health check-up (Box 3.5; Arakawa City, 2018). In Adachi, another ward in Tokyo, a health check-up combined with health promotion is available for those aged between 18 and 40 who do not have the opportunity to access health check-up otherwise (Adachi city, 2018). However, across regions, health check-up items for people aged 75 and over are similar to the specific health check-up (Tokutei kenshin) and check-up items are fixed nationwide (MHLW, 2015b).

Box 3.5. Health check-ups for the insured aged 35-39 in Arakawa City, Tokyo prefecture

Arakawa City has specific health promotion and prevention activities for residents aged between 35 and 39. These include a medical interview, a health check-up including a mental health check, stomach cancer screening, blood pressure, blood test, lung capacity test (for smokers) and clinical examination. About a month after the health check-up, the results are explained to the participants and during this consultation, a public health nurse and a nutritionist provide health education as needed, and a group work is also provided if the results show a need for health guidance. Furthermore, those who are considered to be in need of follow-up health care will have an individual consultation with a doctor (Arakawa City, 2018).

Source: Arakawa City (2018), Kokoro to karada to kimochi no keep: 35 kara 39 sai kenshin no goannai (Information on health check-ups for people aged between 35 and 39), http://www.city.arakawa.tokyo.jp/kenko/hokeneisei/seijinkenshin/3539kensin.html.

For some of the health check-ups organised regionally, subsidies are available to municipalities. The central government provides subsidies for examinations for periodontal disease, osteoporosis and hepatitis. The health check-up for the elderly aged 75 and above is subsidised by the central and regional governments. However, health check-ups for residents aged between 40 and 74, which are provided in addition to legally required specific health check-up and specific health guidance, are usually funded by municipality and municipality-based insurance, although can also receive subsidies from the central government upon request. Reflecting the differences in fiscal conditions, the out-of-pocket payment for regionally organised health check-ups differs across municipalities (MHLW, 2015b).

At the national level, monitoring and evaluation of these additional health check-ups organised by municipality is limited. For example, the uptake of these services by municipality is not known at the national level. It is likely that the uptake varies across regions because out-of-pocket payments and the organisation of these health check-ups vary (e.g. they can be provided at the designated facility such as a city hall by contracted health care professionals, at public health centres on fixed dates or at contracted health care facilities). The effectiveness of these additional health check-ups is also unknown, as the existing health information system does not allow such evaluation as these data cannot be linked with other data such as health care claim data.

3.3.2. Japan does not have nationally organised cancer screening programmes and cancer screening coverage is low

Cancer is the leading burden of disease in Japan (Chapter 1), and the MHLW recommends that municipalities provide screening for stomach, colorectal, lung, breast and cervical cancer. Employment-based insurers can voluntarily include cancer screening as part of their health check-ups for their insured and sometimes for their insured dependents.

The national guideline for cancer screening lays out recommendations on the method, target age and interval for the above-mentioned five cancers. For stomach cancer, a photofluorography or endoscopy is recommended to people aged 50 and over every two years, while colorectal cancer screening based on faecal occult blood test is recommended to people aged 40 and over every year. For lung cancer, a chest X-ray is recommended to people aged 40 and over annually, and sputum cytology is also recommended to smokers aged 50 and over with more than 600 cigarettes smoked in lifetime. Furthermore, mammography is recommended to women aged 40 and over every two years. As for cervical cancer, Pap smear is recommended to women aged 20 and over every two years, and colposcopy is also recommended for this target group if considered necessary (MHLW, 2018d; MHLW, 2018e). However, these guidelines are sometimes different from the international guidelines (Box 3.6).

Box 3.6. Cancer screening guidelines in Japan do not completely align with international recommendations

Japanese guidelines for cancer screening deviate from international practices. The target group for cancer screening is not always in accordance with those used in many OECD countries. While many OECD countries use age 69 as the upper limit for screening programmes for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer, there is no upper age limit in Japan (Table 3.3). In addition, while the majority of OECD countries provide cervical cancer screening every three years, the interval is less frequent in Japan (every two years). For lung cancer, which is recommended in the Japanese national guideline based on the evidence from case control studies in the country, international recommendations are not available (OECD, 2013a; OECD, 2018a; MHLW, 2018d). However, studies in the United States have recently found the effectiveness of low-dose CT scans for lung cancer detection and recommend a low-dose CT scan annually to target population (US Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2018).

Table 3.3. Target age in breast cancer screening programmes, 2016/17

|

Nationwide population-based |

Population-based but not nationwide |

Non-population-based |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Wider age range (20 years+) |

Narrower age range |

Wider age range (20 years+) |

Narrower age range |

Wider age range (20 years+) |

|

|

Australia (50-69), Belgium (50-69), Denmark (50-69), Finland (50-69), France (50-74), Germany (50-69), Hungary (45-65), Iceland (40-69), Israel (51-74), Korea (40+), Latvia (50-69), Lithuania (50-69), Luxembourg (50-69), Netherlands (50-75), New Zealand (45-69), Norway (50-69), Poland (50-69), Portugal (45-69), Slovenia (50-69),Spain (50-69), Sweden (50-69) |

England (53-69), Estonia (50-65), Ireland (50-64 but 50-69 by 2021), Northern Ireland (53-70), Wales (53-70) |

Canada (50-69), Czech Republic (45+), Italy (50-69), Japan (40+), Mexico (50-69), Switzerland (50-70) Turkey (40-69) |

Chile (50-64), |

Greece (40+), Slovak Republic (40-69) and United States (40 or 50+) |

|

Note: Data in parenthesis refers to the target age group for breast cancer screening in then respective country.

Source: OECD (2018a), OECD Health Statistics, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en.

Given the high disease burden, Japan has stomach cancer screening, which is not common across OECD countries, but the recommended protocol for this screening is different from international recommendations. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), the specialised cancer agency of the WHO, recommends that countries with high burden of stomach cancer explore an introduction of population-based H. pylori screening and treatment while considering local contexts such as health priorities and cost-effectiveness (IARC Helicobacter pylori Working Group, 2014). In 2018, the incidence rate for stomach cancer in Japan was one of the highest (12.4 per 100 000 persons) in the OECD followed by Korea (39.6), Chile (17.8) and Lithuania (13.3) (IARC, 2018). In Japan and Korea population-based stomach cancer screening is available. In Japan, stomach cancer screening focuses on biennial screening either by photofluorography or endoscopy to people aged 50 and over while therapeutic regimens for the eradication of H. pylori is covered by the health insurance for patients with gastric or duodenal ulcer who are infected with H. pylori (MHLW, 2013b; MHLW, 2018d). In Korea, nationwide stomach cancer screening using either upper gastrointestinal series or endoscopy is available every two years for men and women aged 40 or over (Choi et al., 2015).

Source: OECD (2013a), Cancer Care: Assuring Quality to Improve Survival, OECD Health Policy Studies, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264181052-en; OECD (2018a), OECD Health Statistics, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en; MHLW (2018d), Gan kenshin (Cancer screening), http://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/0000059490.html; US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (2018), What Screening Tests are There for Lung Cancer, https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/lung/basic_info/screening.htm; IARC Helicobacter pylori Working Group (2014), “Helicobacter pylori Eradication as a Strategy for Preventing Gastric Cancer”; IARC (2018), “Colorectal cancer screening”; MHLW (2013b), Yakujihou no shounin to yakka shuusai no process (Process on pharmaceutical product assessment and pricing), http://www.mhlw.go.jp/file.jsp?id=146639&name=2r9852000002wkg5_2.pdf; Choi, K. S., et al (2015), “Effect of endoscopy screening on stage at gastric cancer diagnosis: results of the National Cancer Screening Programme in Korea”, https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.608.

Unlike many OECD countries which have free nationwide screening programmes for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer (OECD, 2013; European Commission, 2017), standardised nationwide cancer screening programmes do not exist in Japan. While many municipalities organise cancer screening programmes based on the Health Promotion Act, employment-based insurers do not always provide cancer screening. In addition, both municipalities and employment-based insurers often do not follow the cancer screening recommendations set at the national level, and the target population and screening intervals are often different from the national recommendations. In addition, different screening methods are sometimes used (e.g. ultrasonography for breast cancer screening and a chest CT scan for lung cancer) and screening is often provided for cancers other than the five mentioned earlier, and for example, PSA for prostate cancer screening and cytological diagnosis for uterine body cancer are sometimes provided. In 2015, 85% of municipalities reported providing screening for cancers other than the five recommended in the guideline (MHLW, 2016e).

Depending on the municipality and employment-based insurance, out-of-pocket payment for cancer screening varies. The cost of municipality-organised screening for five cancers is subsidised by the central government but due to fiscal situations, the out-of-pocket payment is different across municipalities. Similarly, based on their financial situation employment-based insurers either fully or partly cover the out-of-pocket payment for cancer screening provided by their contracted provider, and given differences in cost-sharing rules and variations in the actual cost of screening, the out-of-pocket payment for cancer screening is also different across employment-based insurers (MHLW, 2018e).

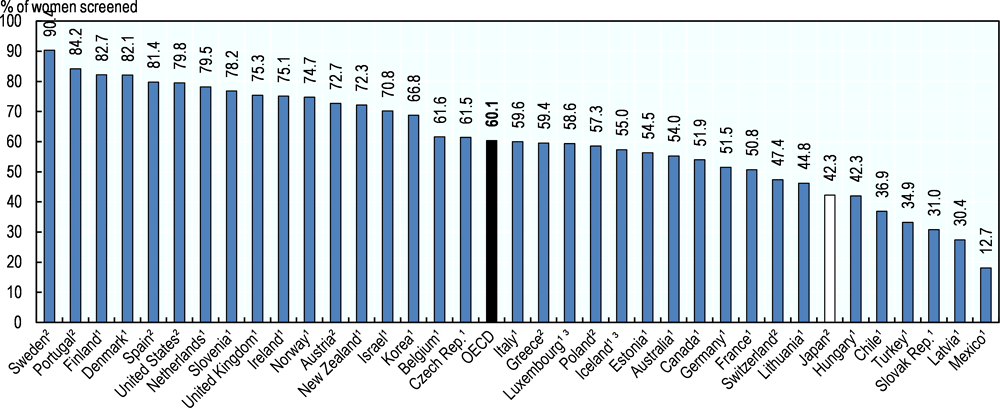

In the OECD, countries with free nationwide organised screening programmes have high cancer screening coverage, while coverage in countries without national programmes – including Japan – is low. Based on survey data, in 2016, 42.3% of women aged between 50 and 69 had a mammography in the past two years in Japan, about 18% lower than the OECD average of 60.1% (Figure 3.2). Similarly, for cervical cancer, although the screening rate had increased by almost 20 percentage points over the past decade, less than half of women aged between 20 and 69 (42.4%) had a Pap smear in the past two years in Japan, while 60.7% of target women had Pap smear in the past three years on average across OECD countries. It is likely that the population coverage of cervical cancer screening would be higher if the screening coverage in Japan also took into account a three year period, rather than the current two year figure. Nonetheless, cervical cancer screening coverage needs to continue increasing in Japan particularly because Japan relies mainly on screening to tackle cervical cancer while other OECD countries also have a national programme on HPV vaccination, in many cases alongside a national screening programme (ECDC, 2012; Chapter 1).

Figure 3.2. Mammography screening in women aged 50-69 within the past two years, 2016 (or nearest years)

1. Programme. 2. Survey. 3. Three-year average.

Source: OECD (2018a), OECD Health Statistics, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en.

In Japan, the screening rate for lung, stomach and colorectal cancers was around the similar level as that for breast and cervical cancers, but it is higher among men than among women. According to the National Livelihood survey, in 2016, 51.0% of men and 41.6% of women both aged between 40 and 69, had had a lung cancer screening in the past year. As for stomach cancer, the screening rate was 46.4% among men and 35.6% among women and for colorectal cancer the screening rate was 44.5% for men and 38.5% for women in the past year (MHLW, 2017d). Screening rates for these cancers are not available for other countries; lung and stomach cancer screening is not common in the OECD, and countries apply different screening methods for colorectal cancer, making it difficult to collect internationally comparable data from countries.

There are large variations in cancer screening coverage in Japan, possibly reflecting differences in out-of-pocket payment, invitation, delivery, organisation and resourcing strategies and public awareness in relation to cancer screening. For example, in 2016, among large municipalities, Maebashi city had a highest screening coverage across different cancers (18.6% for stomach cancer, 17.4% for lung cancer, 16.4% for colorectal cancer, 26.1% for cervical cancer and 28.9% for breast cancer). The coverage, however, was low in Otsu City for stomach cancer (1.7%), Sapporo City and Kawagoe City for lung cancer (1.2%), Kyoto City for colorectal cancer (2.7%), Iwaki City and Kawagoe City for cervical cancer (7.8%) and Miyazaki City for breast cancer (6.6%). Across municipalities, cancer screening coverage is generally higher for breast and cervical cancer (about 10% and over) than for stomach, lung and colorectal cancer (MHLW, 2018c). It should be noted that the coverage of municipality-based cancer screening is calculated using all residents in specific age groups as target population even if at least some residents are eligible to undergo cancer screening organised by employment-based insurance and do not need to be part of their target population, so these screening coverage data are likely to be underreported. Regional variations need to be interpreted with care by taking into account of differences in the coverage of employment-based cancer screening across regions.

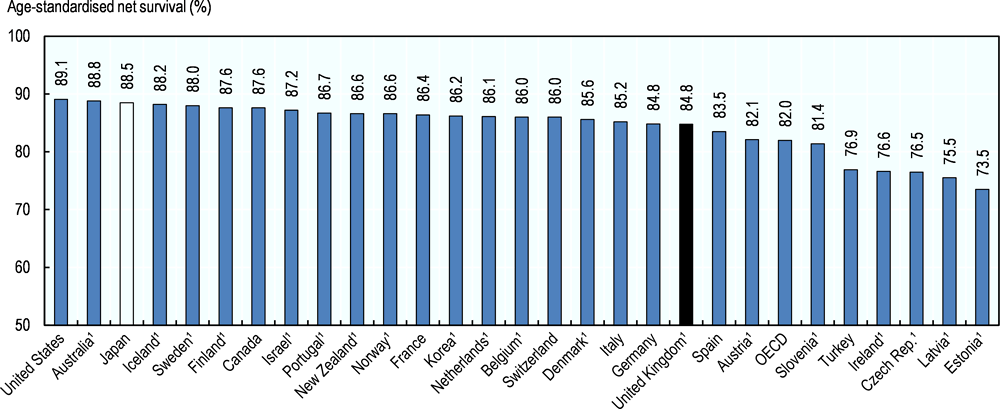

Despite the relatively low screening coverage in general, cancer survival estimates are high in Japan compared to other OECD countries. Based on the internationally comparable data from 16 registries covering 41% of the Japanese population, five-year net survival for breast cancer was 89.4%, the highest after the United States and Australia in the OECD among people diagnosed between 2010 and 2014 (Figure 3.3). As for cervical cancer, five-year net survival was 71.4%, the highest in the OECD after Norway at 73.3%, and the difference with Norwegian estimate was not statistically significant (OECD, 2018a). Similarly for colon cancer, net survival was high. For rectal cancer, net survival (64.8%) was higher than the OECD average (61.0%) but not as high as in the best performing countries such as Korea and Australia with net survival above 70% (OECD, 2018a; Allemani et al., 2018).

Figure 3.3. Breast cancer five-year net survival, 2010-2014

Note: 1. Data with 100% coverage of the national population.

Source: OECD (2018a), OECD Health Statistics, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health-data-en.

The survival estimate is also high among cancer patients for which many OECD countries do not have screening programmes (Box 3.6). Five-year net survival estimates for patients with stomach cancer are the second highest in the OECD after Korea and have improved fast from 50.5% among those diagnosed between 2000 and 2004, to 60.3% among those diagnosed between 2010 and 2014. Several studies show that stomach cancer screening has contributed to the mortality reduction (Mizoue et al., 2003; Miyamoto et al., 2007). Furthermore, five-year net survival for lung cancer is the highest in the OECD at 32.9% among those diagnosed between 2010 and 2014 (Allemani et al., 2018).

However, the factors contributing to the good cancer care outcomes are not well known because the cancer registry in Japan is not complete enough to undertake such an assessment. While many OECD countries have established a national cancer registry over recent decades and use the registry data to monitor the quality of cancer screening, to provide feedback on the quality of screening to providers, and to improve the screening programmes (Box 3.7), the information system for cancer care in Japan is still fragmented. In Japan, the data collected through municipality-based screening is monitored and indicators such as recall rate, the share of those who had follow-up detailed examinations, detection rate, and positive predictive values are reported by municipalities (Saito, 2018). However, this monitoring effort only includes people who underwent municipality-based screening programmes, but not others who underwent cancer screening provided and covered by employment-based insurance or who had cancer screening voluntarily at health care facilities. By increasing the coverage of providers, regional cancer registries have been developed, and in 2016, the national cancer registry was started, expanding data coverage across providers and regions. Yet, it is still challenging to assess the effectiveness of cancer screening and also cancer care comprehensively in Japan.

Box 3.7. Cancer registries across OECD countries and their use

Many OECD countries have established national cancer registries in recent decades. For example, Finland has a well-established national cancer registry and all providers are obliged to report to the registry. In Sweden, each cancer centre has its own quality registry, covering 20 different cancers, and the National Cancer Registry in the National Board of Health and Welfare oversees the national trend and regional differences in cancer control, using data across all oncology centres. To illustrate another example, Korea has the Central Cancer Registry, a hospital-based nationwide cancer registry, covering the entire population (OECD, 2013a).

A national cancer registry is essential for efficient management of screening programmes. It can identify the people who have and have not participated in the screening programmes, those who are monitored outside of the programme due to their previous diagnosis of cancer and/or genetic predisposition to specific cancer and those who do not consent to undergo screening. An established cancer registry allows sending personalised invitations and reminders to the target population and these personalised and targeted communication strategies are considered important for increasing the screening coverage (OECD, 2019).

In view of conducting more detailed assessments, including of the effectiveness of cancer screening, an increasing number of OECD countries collect stage information. Stage at diagnosis is collected in a number of countries including the Czech Republic, Denmark, Ireland, Korea, the Netherlands, Norway, Slovenia, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States. In the Czech Republic, and Sweden, stage information is collected by using tumour node metastasis (TNM) classifications. Danish Cancer Registry also collects stage information based on TNM and surveillance, epidemiology and end results (SEER) classifications while in Norway, cancer registry collects stage information by TNM classification for colorectal, ovarian and breast cancers and by SEER high-level classification for the other cancers. These data can be explored periodically to assess the effectiveness of existing cancer screening protocols such as target group, screening interval and/or methods and effectiveness of screening across populations with different background.

Cancer registries in several countries also collect treatment and outcome data, allowing even more in-depth analyses on the effectiveness of cancer care interventions. For instance, in Slovenia and Sweden, registries have been collecting treatment and outcome data, including remission and relapse while in Switzerland, treatment and outcome data are available in some cantonal registries. Furthermore, in the United States, 17 SEER registries routinely collect data on first course of treatment, and active follow-up for vital status, besides patient demographics, primary tumour site, tumour morphology and extent of disease.

Several countries also use cancer registry data for quality assurance of cancer care. For instance, a comprehensive quality assurance mechanism, which allows providing feedback to providers, has been developed in Israel for breast cancer. Every entry in the cancer detection centre is registered in a centralised electronic database. The database contains screening information from all providers, and over 90% of diagnosis test results for individuals who had a mammography. Data including detection rates, recall rates, further examination rates, and staging information, and negative/positive test result rates are provided to all providers every year so that they can compare their performance relative to the national average and to other providers in the country. Using the database, every care pathway is monitored, and providers receive a report in case of an irregular pathway (OECD, 2013a).

Source: OECD (2013a), Cancer Care: Assuring Quality to Improve Survival, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264181052-en; OECD (2019), OECD Public Health Reviews: Chile: A Healthier Tomorrow, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264309593-en.

3.3.3. The coverage of additional health check-up items varies across employment-based insurers

MHLW recommends employer-based insurance to provide additional health check-ups. Recommendations are slightly different between Society-Managed Health Insurance (Kenpo kumiai or Kenpo) and Japan Health Insurance Association (Kyoukai Kenpo), but basically the provision of more health check-up items is recommended. For example, recommendations include health check-ups for lifestyle-related diseases at least once every five years for employees and their dependents aged between 30 and 40 who are covered by the Society-Managed Health Insurance. Recommendations for Japan Health Insurance Association include the provision of additional health check-ups for the insured aged between 40 and 50 (MHLW, 2015). In general, a wider coverage of health check-up items is considered favourably as this is seen as the level to which employers care about the welfare of their employees. Insurers with good financial conditions try to cover additional health check-up items, but across insurers, the coverage of additional health check-up items varies substantially. Moreover, the uptake and effectiveness of these health check-ups are not known because of the fragmented nature of data holdings at the provider levels.

3.3.4. Many other health check-ups are available privately

Individuals can freely choose to undergo health check-ups from amongst the many check-ups offered outside of publicly funded health care. Many health care providers provide such health check-up services (ningen dock). The content of these health check-up items provided varies substantially, but they often include cancer screening. Some hospitals provide health check-ups which last more than a day, and the cost varies widely across types of health check-ups and providers. For full-time employees, the cost of such health check-up is sometimes covered by their insurance, particularly among those insured by the Society-Managed Health Insurance. Some private health insurance also reimburses part of the out-of-pocket payment paid by the insuree if their contract includes such coverage. Information on these additional check-ups, covered either by publicly funded insurance or privately, is stored and managed in a fragmented manner at the provider level, so the uptake and its effectiveness is not known.

For these health check-ups, there is no quality assurance mechanism, such as regulations on the coverage and frequency, unlike the legally required health check-ups (Box 3.8). Hence, these additional services may even increase health risks through high exposure to radiation, over-diagnosis and over-treatment, or add unnecessary stress, for example, through false negative and positive results (Box 3.9). Information on such risks is not available, for example in the form of guidelines, to guide insurers and municipalities in making coverage decisions, support providers in providing evidence-based health check-ups, and also support individuals in deciding which health check-up to choose.

Box 3.8. The quality assurance mechanisms have been established for health check-ups which are required to provide legally

The quality assurance mechanism has been developed for health-check-ups which are legally required in Japan, namely health check-ups for preschool children, school children, full-time employees and adults aged between 40 and 74. For these health check-ups, the coverage of health check-up items and methods of delivering them are reviewed regularly by experts at working group meetings designated for each of these check-ups, and national guidelines are updated and circulated among providers so that the quality of these services is standardised.

For example, as part of quality assurance of specific health check-ups and guidance, based on the national guideline, the National Institute of Public Health (NIPH) has developed learning and support materials and makes these materials available online for providers of specific health check-ups, and provides training on the specific health check-up and guidance to managers at the prefectural governments, and insurers at the national or prefectural level. Three-day training is available for trainers at the prefecture level so that they can train managers at municipality governments to plan, organise and evaluate specific health check-ups at the local level. Two-day training is also available for those engaged in evaluating specific health check-ups and guidance at the prefectural level so that they can train and support those responsible for monitoring and evaluation of specific health check-ups and guidance at the municipality or insurer’s level. Those who underwent training provided by the NIPH provide training to providers of specific health check-ups at the prefectural and municipal levels and NIPH staff sometimes provides training to them in order to assure that the quality of specific health check-ups and health guidance provided by various health care providers is high and standardised.

In addition, the National Federation of Industrial Health Organization makes further efforts to assure the quality of core health check-ups for full-time employees. The National Federation evaluates samples of blood and urine laboratory test, X-ray examination and ultrasonography for testing precision provided by participating providers, and these results are reported publically. If they wish, providers of health check-ups can ask the National Federation of Industrial Health Organization to conduct comprehensive performance assessment of multiple dimensions including human resource, equipment, facility, technical aspects of health check-ups, data management and follow-up protocols after a health check-up, and certifies them based on the assessment results. In addition, the Federation provides training to professionals providing health check-ups including doctors, public health nurses, nurses, clinical laboratory technicians and radiology technicians providing health check-ups.

Quality assurance procedures are available for most health check-ups which municipalities are recommended to provide. To assure quality, national guidelines have been developed and updated for health check-up items recommended to provide at the municipality level including osteoporosis, periodontal disease, tests for hepatitis and health check-ups for the elderly aged 75 and over.

Additional efforts have been made to improve the quality of certain health check-ups. Recently, the government tries to incentivise insurers to attain higher health outcomes through specific health check-up, and the outcome measures such as a reduction of people with diabetes and people with risks of developing lifestyle-related diseases are used to monitor the effectiveness of specific health check-ups. But more can be done. For example, within the national monitoring system, these outcomes could be reported at the insurance level and used to provide feedback to each insurer.

Box 3.9. Potential harms associated with secondary prevention