This chapter provides the background to the remaining chapters of the report. It presents an overview of the broader economic, social and political context in Colombia. This includes differences in poverty and well-being between rural and urban areas and the achievement of reaching a peace agreement between the government and the FARC-EP. It also provides a description of the school system, including governance, structure and organisation. Finally, the chapter presents an analysis of the quality, equity and efficiency of school education, highlighting differences in coverage and quality between urban and rural areas, advantaged and disadvantaged students and girls and boys.

OECD Reviews of School Resources: Colombia 2018

Chapter 1. School education in Colombia

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Economic, social, demographic and political context

The Colombian economy has grown strongly since the turn of the century but poverty and inequality remain relatively high

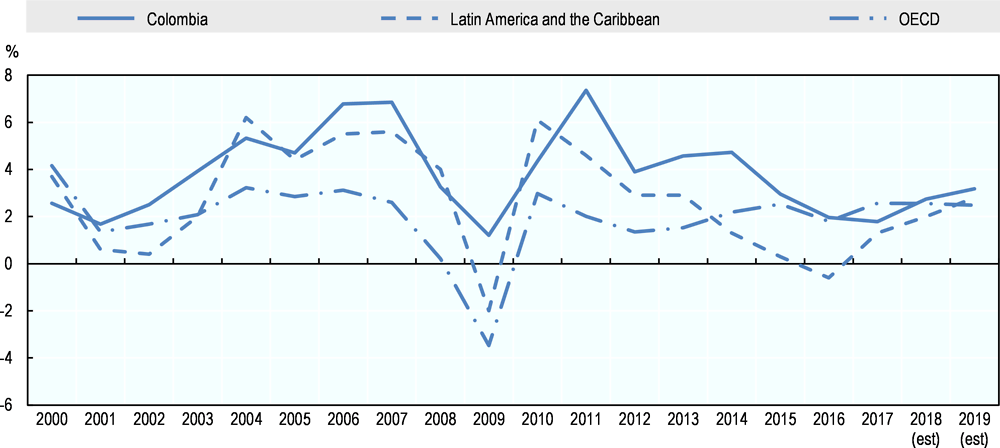

Colombia has witnessed strong and sustained economic growth since overcoming a deep recession in the late 1990s (see Figure 1.1). Between 2000 and 2015, the economy grew by an average of 4.3% in real terms despite the global financial and economic crisis. This is significantly more than the OECD average of 1.7%. The economy benefitted from sound macroeconomic policies, structural reforms, a rise in commodity prices and strong investment (OECD, 2017[1]). In recent years, growth in Latin America has slowed down and the region underwent a recession in 2015 and 2016 (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2018[2]). Weaker trade and a fall in commodity prices have also slowed down the Colombian economy but Colombia has weathered these challenges better than other countries in the region thanks to public investment, private consumption and a large depreciation of the exchange rate (OECD, 2017[1]).

Figure 1.1. Recent and projected real GDP growth

est – estimated growth

Source: OECD (2018), OECD Economic Outlook 103 Database, http://stats.oecd.org (accessed on 01 June 2018); IMF (2018), IMF World Economic Outlook Database, https://www.imf.org (accessed on 01 June 2018).

In September 2016, the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – Ejército del Pueblo, FARC‑EP) reached a historic peace agreement (see Box 1.1). Building a post‑conflict society remains a long-term task and challenge but promises greater social well-being and economic prosperity. Various studies, using different methodologies and types of data, estimate that the conflict had reduced rates of GDP growth by 0.3 to 0.5 percentage points per year (Arias et al., 2014[3]; Riascos and Vargas, 2011[4]). Estimates from Colombia’s National Planning Department (DNP) suggest that the end of the armed conflict will increase GDP growth by an additional 1.1 to 1.9 percentage points per year, in part thanks to greater security and confidence and growing investments (OECD, 2017[1]).

Box 1.1. Colombia’s agreement to end conflict and build peace

Colombia has suffered from a complex internal conflict lasting more than half a century, with responsibility for violence falling on a differentiated basis on many shoulders: guerrilla groups, the paramilitary and state agents acting outside their legal mandate. The conflict has been one of the most violent in the modern history of Latin America with an estimated number of at least 220 000 deaths between 1958 and 2012, 80% of which were unarmed civilians (GMH, 2016[5]).

These numbers, however, do not reveal the full dynamics and suffering of the Colombian population. The conflict has resulted in large numbers of victims of forced disappearances, displacement, abductions, unlawful recruitment, torture and abuse, anti‑personnel mines and sexual violence (GMH, 2016[5]). The official victims registry (Registro Único de Víctimas) counted a total of 8.6 million victims as of January 2018, with 461 000 being children younger than 5, and nearly 2 million children and young people aged between 6 and 17. An estimated number of 7.2 million people have been displaced by the conflict, the largest number of internally displaced people worldwide (Sánchez, 2018[6]), with large losses in welfare, which are even greater for poorer families (Ibáñez and Vélez, 2008[7]). Indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities have been especially harmed by the dynamics of the conflict (GMH, 2016[5]).

The numbers also do not capture the impact of the conflict in other dimensions, such as economic activity, public infrastructure or social cohesion. The conflict has equally affected children’s education and the school system, causing interruptions to the education of displaced students, through recruitment into armed groups, threats to teachers or damage to physical infrastructure (González Bustelo, 2016[8]). Research reveals that conflict increases prenatal stress for women, with negative effects on the birthweight of children and long-term consequences on cognitive abilities (Camacho, 2008[9]). The conflict also has had a negative effect on equity in terms of access to education, leading to school dropout especially for disadvantaged children (Vargas, Gamboa and García, 2013[10]).

The scale of violence has varied over time and across place. While some areas have experienced continuous conflict, in others violence has been largely absent. Following an upsurge of violence between 1996 and 2002, the intensity of the conflict has been decreasing until the present day (GMH, 2016[5]). On 24 November 2016, the Colombian government and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC-EP), the country’s largest guerrilla group, signed a historic peace agreement promising the beginning of a new chapter in the country’s history. Nevertheless, ensuring the effective implementation of the agreement – including through an allocation of the required resources – and building peace will be a major challenge (UN, 2017[11]). Peace negotiations with the second largest guerrilla group, the National Liberation Army (Ejército de Liberación Nacional, ELN), have been underway but are yet to be concluded. Illegal armed groups, guerrilla and non-demobilised paramilitary also still exist. In some parts of the country, violence seems to have intensified as reported by Amnesty International (2018[12]).

The peace agreement is composed of a series of accords all based on the goal to promote the constitutional rights of all Colombians and the recognition of the equality and protection of the pluralism of Colombian society, its territories and communities. The accords entail i) a comprehensive rural reform (Reforma Rural Integral); ii) actions to enhance the population’s political participation; iii) the end of hostilities and steps to reintegrate former FARC members into civil and political life; iv) actions to find solutions to the problem of illicit drugs; v) a comprehensive system for truth, justice, reparation and non-repetition to safeguard the rights of the conflict’s victims; and vi) verification and implementation mechanisms. The implementation of the different accords is to be supervised by national and international overseers, ensuring their fulfilment over the 15 years stipulated in the agreement.

The agreement and accords also rest on the implementation of agreed actions in the area of education. The rural reform does not only promote the economic recovery of the countryside through land access and use but also the development of national plans to improve public services and infrastructure. For education, this includes the development and implementation of a Special Rural Education Plan (Plan Especial de Educación Rural, PEER). In the zones most affected by the conflict and poverty, these national plans, including the one linked to education, will be implemented through Development Programmes with a Territorial Approach (Programas de Desarrollo con Enfoque Territorial, PDET). To strengthen political participation and inclusion, a policy of peace education has been developed and implemented as of 2018. As part of the programme for the social and economic reincorporation of the former guerrilla, the Ministry of National Education (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN) and the National Learning Service (Servicio Nacional de Aprendizaje, SENA) are developing education programmes adapted to the needs of demobilised fighters and their families (Mesa de Conversaciones [Conversation Roundtable], 2017[13]).

Sources: GMH (2016), Basta Ya! Colombia: Memories of War and Dignity, Centro Nacional de Memoria Histórica [National Center for Historical Memory], Bogotá, DC; Sánchez, J. (2018), OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools: Country Background Report for Colombia, http://www.oecd.org/education/schoolresourcesreview.htm; Ibáñez, A. and C. Vélez (2008), “Civil conflict and forced migration: The micro determinants and welfare losses of displacement in Colombia”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.04.013; González Bustelo, M. (2016), El Verdadero Fin del Conflicto Armado: Jóvenes Vulnerables, Educación Rural y Construcción de la Paz en Colombia [The Real End of the Armed Conflict: Vulnerable Youth, Rural Education and the Construction of Peace in Colombia], https://noref.no; Camacho, A. (2008), “Stress and birth weight: Evidence from terrorist attacks”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.2.511; Vargas, J., L. Gamboa and V. García (2013), “El lado oscuro de la equidad: Violencia y equidad en el desempeño escolar [The dark side of equity: Violence and equity in school performance]”, http://dx.doi.org/10.13043/DYS.74.7; UN (2017), Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Concluding Observations on the Sixth Periodic Report of Colombia, United Nations Economic and Social Council, New York; Amnesty International (2018), Amnesty International Report 2017/18: The State of the World´s Human Rights, Amnesty International, London; Mesa de Conversaciones [Conversation Roundtable] (2017), Acuerdo Final para la Terminación del Conflicto y la Construcción de una Paz Estable y Duradera [Final Agreement to End the Armed Conflict and Build a Stable and Lasting Peace], Oficina del Alto Comisionado para la Paz [The Office of the High Commissioner for Peace], Bogotá, DC.

Colombia´s economy showed signs of a revival in the second half of 2017 with growing investments and a slow recovery in imports and exports. Over the next 2 years, the economy is forecast to strengthen gradually to 3% in 2018-19, supported by lower interest rates, investment in infrastructure, higher oil prices and significantly stronger exports. Trade prospects and commodity prices continue being main risks to the economy in the medium term (OECD, 2017[14]). Like most of Latin America, Colombia faces the challenge of overcoming the middle-income trap, moving to more knowledge-intensive activities and sustaining the social gains that have been made in recent years (OECD/CAF/ECLAC, 2016[15]).

The fall in oil prices has put pressure on government revenues and narrowed the space for public spending. The country´s fiscal rule adopted in 2011 safeguards fiscal and debt sustainability with a gradual consolidation of the structural deficit to 1% of GDP by 2022. To comply with the rule, public investment was cut in 2015 and 2016. While a tax reform introduced in 2016 is expected to generate new revenues, the need for infrastructure and social spending is likely to exceed revenues in the medium term and require additional sources of revenue (OECD, 2017[1]).

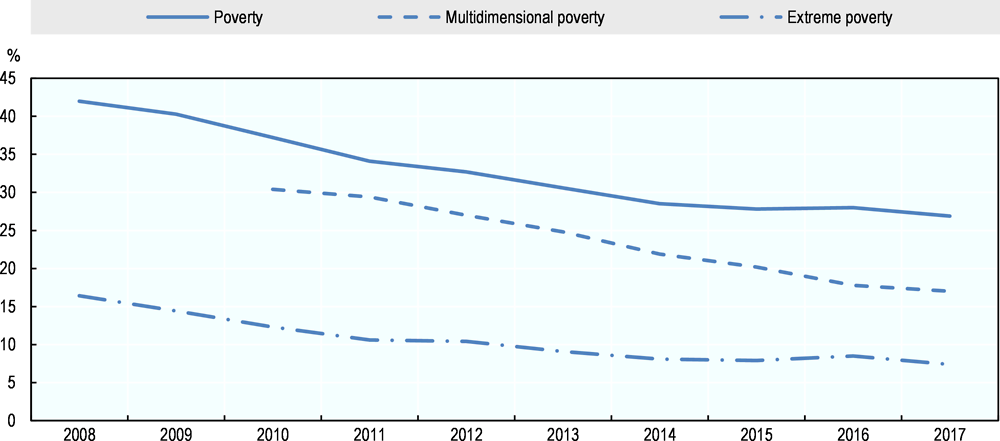

Economic development and social policies targeting the most vulnerable have improved the socio-economic conditions of many Colombians, including the poorer parts of society (OECD, 2016[16]) (see Figure 1.2). More Colombians have moved up into the middle class, even though less so than in other countries in Latin America, such as Chile and Mexico (Angulo, Gaviria and Morales, 2014[17]). Whereas 22.0% of Colombians could be considered to be middle class in 2008, this was the case for 30.4% of Colombians in 2016 (CEDLAS and the World Bank, 2018[18]).

Figure 1.2. Trends in national poverty rates in Colombia

Notes: The poverty rate measures the percentage of the population with a per capita income in the household below the poverty line, in relation to the total population. The extreme poverty rate measures the percentage of the population with a per capita income in the household below the extreme poverty line, in relation to the total population. Both measures are based on income data from the Integrated Household Survey. The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) is based on five dimensions (education, living conditions of children and youth, health, work, access to public services and housing) and 15 indicators. People are considered poor if deprived of at least five of these 15 indicators. Data are obtained from the National Quality of Life Survey.

Sources: DANE (2018), Gran Encuesta Integrada de Hogares (GEIH) [Integrated Household Survey], https://www.dane.gov.co (accessed on 01 June 2018); DANE (2018), Encuesta Nacional de Calidad de Vida (ECV) [National Quality of Life Survey], https://www.dane.gov.co (accessed on 01 June 2018).

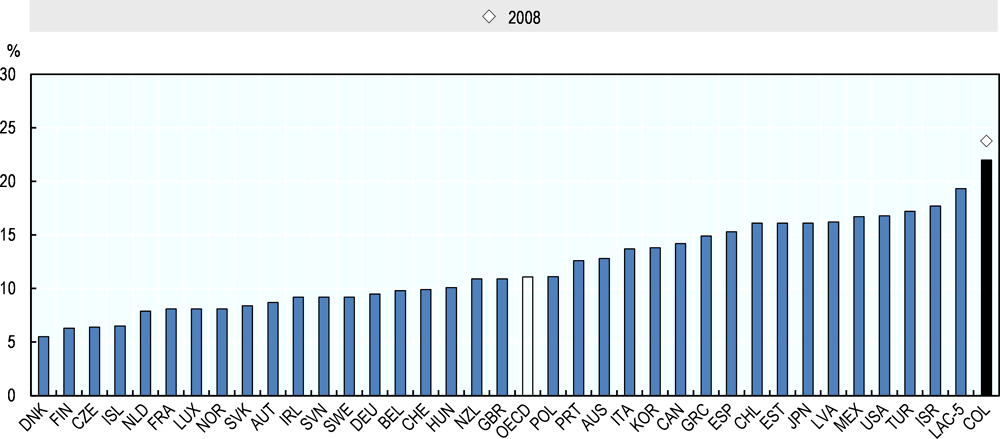

However, Colombia needs to make further strides to reduce poverty, particularly among children and the elderly, and to create a more equal society (OECD, 2016[16]). Poverty is still higher than in any other OECD country and many countries in Latin America (see Figure 1.3). Based on a relative poverty line defined as 50% of the median household disposable income, 22% of Colombians were poor in 2015, twice as much as the OECD average (OECD, 2017[1]). Children are especially vulnerable. In 2011, slightly less than one in three grew up in relative poverty (OECD, 2017[1]). In 2017, 23.8% of people in a household with 3 or more children under the age of 12 were below Colombia’s absolute poverty line (DANE, 2018[19]).

Figure 1.3. Relative income poverty

Notes: The relative poverty rate is the ratio of the number of people whose income falls below the poverty line; taken as half the median household income of the total population.

Data for Israel refer to 2016, to 2014 for Australia, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Mexico, New Zealand and Switzerland, and to 2012 for Japan.

Data for LAC-5 refer to the simple average for Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Peru.

Sources: OECD (2017), OECD Income Distribution Database (IDD), http://stats.oecd.org (accessed on 01 June 2018); CEDLAS and The World Bank (2017), Socio-Economic Database for Latin America and the Caribbean (SEDLAC), http://www.cedlas.econo.unlp.edu.ar (accessed on 01 June 2018).

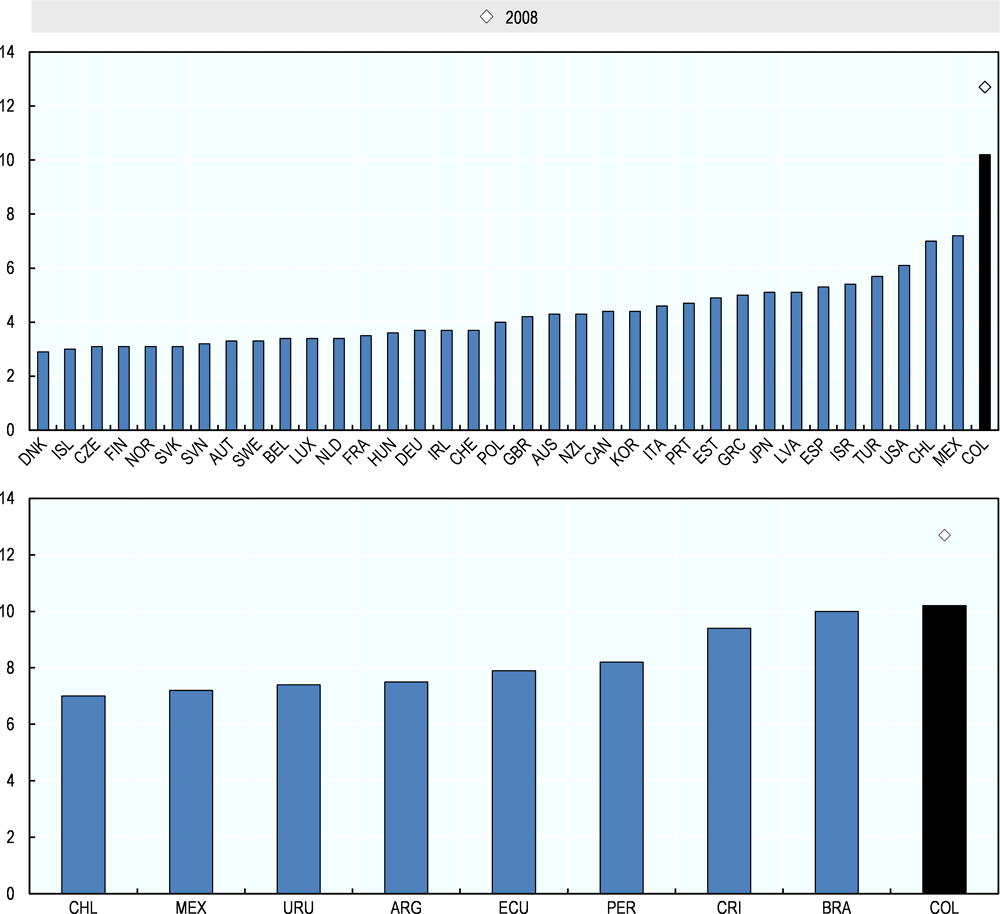

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, income inequality has decreased for most countries in Latin America, one of the most unequal regions in the world. On average, inequality, as measured by the GINI coefficient, decreased from 0.56 in 2002 to 0.51 in 2016, with a particularly stark reduction in the first decade of the 2000s (CEDLAS and The World Bank, 2017[20]).1

In Colombia, income inequality dropped as well, from 0.56 in 2002 to 0.51 in 2016, but started to decrease particularly from 2010 onwards (World Bank, 2018[21]). Redistribution had much less of an impact on poverty reduction in Colombia than in other countries in the region and evidence suggests that poverty would have declined more had economic growth been distributed more equitably (Giménez, Rodríguez-Castelán and Valderrama, 2015[22]). Compared to OECD countries, inequality in Colombia remains extremely high as shown in Figure 1.4.

Figure 1.4. Income inequality across households

Notes: The P90/P10 ratio is the ratio of income of the 10% of people with the highest income to that of the poorest 10%.

Data for Israel refer to 2016, to 2014 for Australia, Denmark, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Mexico, New Zealand and Switzerland, and to 2012 for Japan.

Sources: OECD (2017), OECD Income Distribution Database (IDD), http://stats.oecd.org (accessed on 01 June 2018); CEDLAS and The World Bank (2017), Socio-Economic Database for Latin America and the Caribbean (SEDLAC), http://www.cedlas.econo.unlp.edu.ar (accessed on 01 June 2018).

Public social spending has increased, and social programmes have contributed to poverty alleviation, but social expenditure remains relatively low relative to GDP and to the OECD and still redistributes too little. The pension system accounts for a large share of central government spending and is highly unequal. Colombia’s tax system also still does little to reduce inequality (OECD, 2016[16]; OECD, 2017[1]).

Strong economic growth has improved employment outcomes in recent years, especially for women, young people and older workers. But unemployment remains high and those who are unemployed are at risk of falling into poverty as the level of allowances remains small (OECD, 2017[1]). In 2016, 9.2% of the Colombian labour force was unemployed, compared to 7.2% on average across the OECD. Nevertheless, some OECD countries have higher unemployment rates than Colombia, namely France, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain and Turkey (OECD, 2017[23]).

The informal sector of the labour market remains persistently large. The Colombian authorities have put in place various initiatives to promote the formalisation of labour, and some of these have had an effect on labour market segmentation, but about six in ten Colombian employees still work in informal jobs. While there is voluntary and involuntary, and higher- and lower-paid work in the informal segment of the labour market (García, 2017[24]), workers in informal jobs often suffer from poor working conditions, the lack of social safety nets and lower returns to their education.

Informality puts workers at a high risk of poverty when they lose their job or retire. And it is closely related to inequality as informal workers are paid less for the same level of education (Amarante and Arim, 2015[25]; Herrera-Idárraga, López-Bazo and Motellón, 2015[26]; OECD, 2017[1]).2 More broadly, there is room for improving the quantity, quality and inclusiveness of work (OECD, 2017[27]) and for considering precarious working conditions for both formal and informal workers (Ferreira, 2016[28]).

Stubbornly high levels of inequality are a particular concern in light of low social mobility across generations and inequalities in opportunities in Colombia. Various studies suggest that social mobility has improved since the turn of the century. But it remains difficult for individuals to overcome their social background and achieve better outcomes in socio-economic conditions and education than their parents, and more so than in other countries in the region like Chile and Mexico (Angulo et al., 2014[29]; Galvis and Roca, 2014[30]; García et al., 2015[31]).

Angulo et al. (2014[29]), for example, find that the chances of a child growing up in a poor family to achieve a high income are less than 7%. The lack of social mobility is closely linked to inequalities in opportunities, which, despite improvements, also remain substantial. Individual circumstances that are beyond one’s control and in particular one’s parents’ level of education play a significant role for later outcomes in life in Colombia (Ferreira and Meléndez, 2014[32]; Vélez and Torres, 2014[33]).

There are large gaps in social and economic development between regions and the armed conflict has particularly affected life in rural areas

Colombia is a country of regions and geographical and cultural diversity. With a land mass of 1.1 million km2 (almost twice the size of Texas or France), it is the fifth largest country in Latin America and the only country in South America that borders both the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. It encompasses parts of the Andes which split into three chains with two long valleys between them, and, to the south-east, the Llanos, remote tropical lowlands, and parts of the Amazon. Colombia’s population (an estimated total of about 49 million in 2017) is concentrated in the Andean and Caribbean regions where the country’s largest cities with more than one million inhabitants – Bogotá, Medellín, Cali and Barranquilla – can be found. Fewer people live in the sparsely populated areas in the south-east and on the Pacific coast (DANE, 2012[34]).

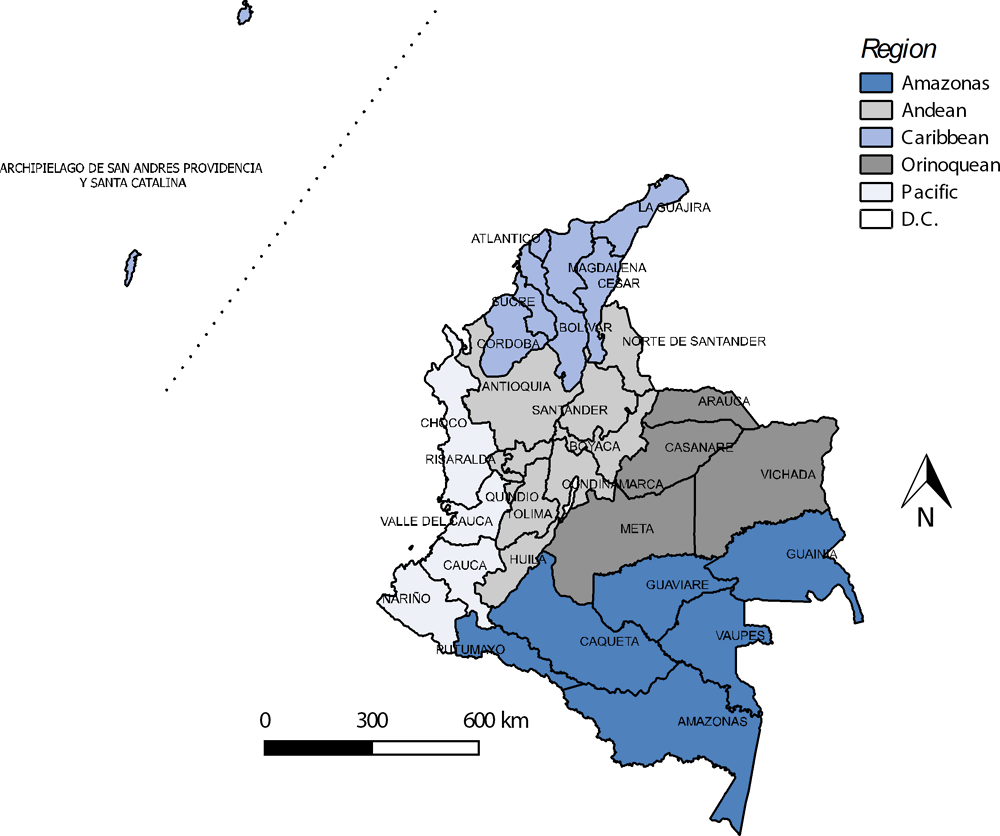

Colombia is a decentralised but unitary state, with all government offices being located in the capital Bogotá. Politically and administratively, the country is organised into territorial entities. At this territorial level, there are 32 departments, 7 districts,3 1 122 municipalities and indigenous territories.4 While departments correspond to the regional level, districts and municipalities refer to the local level. Indigenous territories are governed by their own councils, the Cabildos Indígenas, and their own laws. Figure 1.5 shows Colombia’s regions and the departments that are part of them (for further details about the political context and the public sector, see Sánchez (2018[6]).

Figure 1.5. Regions of Colombia

Note: This map presents regions based on social and cultural convention.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Sánchez, J. (2018), OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools: Country Background Report for Colombia, http://www.oecd.org/education/schoolresourcesreview.htm.

Among Colombia’s 102 officially recognised ethnic minorities, the Afro-Colombian population (including Raizal and Palenquero) make up the largest group. Based on the census of 2005, more than 4.3 million, or 10.6%, identified themselves as Afro-Colombian. Indigenous peoples make up 3.4% of the population (about 1.4 million), and the Rrom 0.01%. Indigenous communities are highly concentrated in the Amazonas and Pacific regions and the department of La Guajira. Afro-Colombian communities have a high concentration in the Pacific and the Caribbean regions. There are 65 indigenous languages, 2 Afro-Colombian and the Romani of the Rrom, all recognised as official languages within these communities (Sánchez, 2018[6]).

In a similar way to many other countries in Latin America, Colombia has become largely urbanised. Based on estimates, 37.8 million people, that is more than 3 in 4 Colombians (77.0%), lived in urban areas in 2017 (OECD average: 80.7%). The remaining quarter of the population (23.0%), or 11.3 million people, lived in rural areas (OECD average: 19.3%) (World Bank, 2018[35]).5 This process of urbanisation has also been driven by migration from rural to urban areas, resulting from the failure of public policy, a lack of institutions, violence and poor living conditions in rural areas (OECD, 2014[36]).

Between 1993 and 2005, 63% of municipalities experienced negative or close to zero rates of population growth. Slightly more than half of municipalities with less than 10 000 inhabitants were losing population in that period, especially young people between 16 and 29 years (PNUD, 2011[37]). As the National Demographic and Health Survey from 2015 suggests, internal migrations within the 5 years prior to the survey came to 25% from rural areas, particularly from remote rural areas (21%); 27% of rural migrants were 19 years old or younger (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social and Profamilia, 2017[38]).

Despite these trends, the population in rural areas still tends to be younger than in urban areas. In 2015, almost 31.5% of rural Colombians were less than 15 years old, compared to 25.4% of Colombians living in urban areas. In general, while the country as a whole has been undergoing a demographic transition with declining fertility and mortality rates since the 1960s, the population remains relatively young, presenting Colombia with a demographic boon (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social and Profamilia, 2017[38]). In 2017, slightly less than 1 in 4 Colombians was under 15 years old (23.5%, compared to 18.0% on average across the OECD) (World Bank, 2018[35]). The political crisis in Venezuela has been bringing a growing number of migrants, a large share of which is younger than 18 years (Sánchez, 2018[6]).

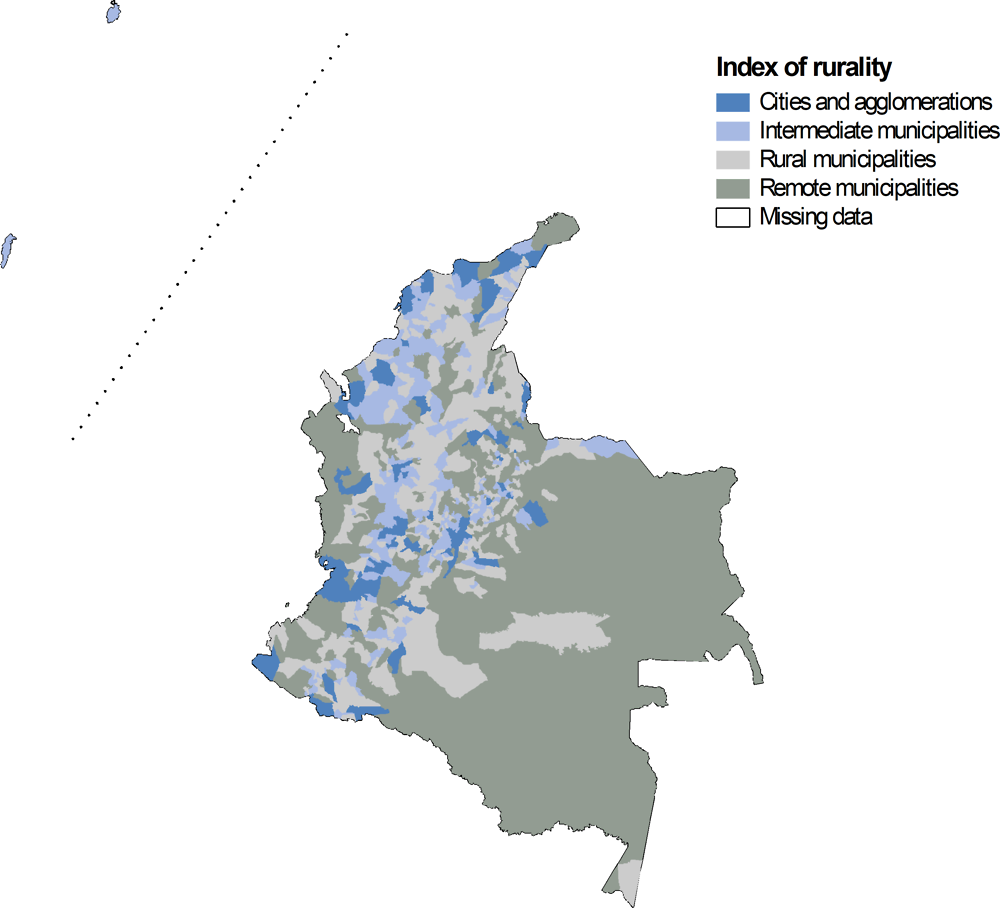

Even though Colombia has become urbanised over the last 50 years, rural life still plays a significant role in the country (DNP, 2015[39]). Using a definition of rurality that takes density and distance into account, a little more than 30% of Colombians live in rural areas and between 60% and 76% of municipalities can be considered rural (PNUD, 2011[37]). Colombia’s “Rural Mission”, a rural development strategy explained in Box 1.2, developed a classification of the country’s municipalities to better reflect their rurality.

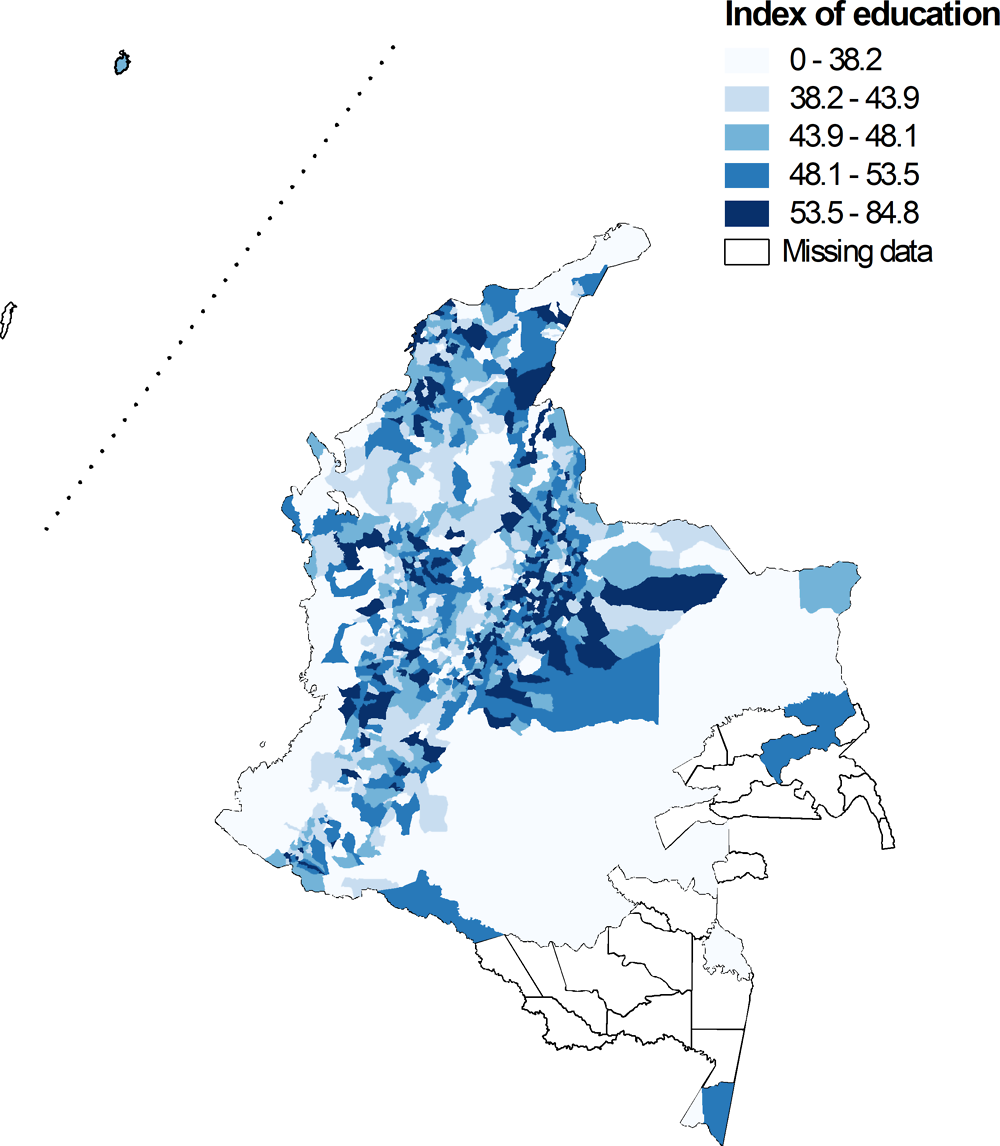

Accordingly, municipalities can be described as “cities and agglomerations”, “intermediate”, “rural” and “remote”. As Figure 1.6 illustrates based on this classification, the country’s periphery and the areas separating the Caribbean from the centre are highly rural. Data from Colombia’s population census carried out in 2018 will provide new insights into current population dynamics and demographics.

Economic development has been uneven across the country. The Gini index of inequality of GDP per capita across regions provides a measure of the economic disparities between regions in a country. For Colombia, this index was more than twice as high as the OECD average (0.35 vs 0.16), and slightly higher than in other Latin American countries, such as Chile (0.33), Mexico (0.32) and Brazil (0.30) in 2013 (OECD, 2016[40]).

These regional disparities are influenced by the country’s topography limiting connections between regions in the absence of efficient infrastructure. High mountain ranges make building new roads and maintaining existing ones much more expensive than in countries with a flatter topography (OECD, 2017[1]). Weak institutions, few linkages between rural and urban as well as between rural areas and a focus on traditional agricultural activities also contribute to regional disparities (OECD, 2014[36]).

Poverty and well-being also vary considerably between as well as within regions and departments, with a clear divide between the country’s centre and periphery (Cortés and Vargas, 2012[41]). Based on data from the National Quality of Life Survey (ECV) carried out by DANE, Colombia’s statistical agency, 5.9% of the population of the capital city, Bogotá, lived in multidimensional poverty in 2016.6 In the Caribbean region, multidimensional poverty was more than 5 times as high, at 26.4%. The Pacific region, excluding the department Valle del Cauca, had the highest rate of multidimensional poverty with 33.2% (Sánchez, 2018[6]).

Figure 1.6. Rurality in Colombia

Note: Municipalities are classified as cities and agglomerations (117 municipalities), intermediate (314 municipalities), rural (373 municipalities) and remote (rural disperso) (318 municipalities). This classification is based on the categories established by Colombia's Rural Mission (Misión para la Transformación del Campo) to better reflect geographical realities of the country. It takes into account i) rurality within the System of Cities established through the Urban Mission (Misión de Ciudades); ii) population density; and iii) the relation between the population in urban and rural areas.

Source: Authors’ elaboration, based on DNP (2015), El Campo Colombiano: Un Camino hacia el Bienestar y la Paz Misión para la Transformación del Campo [Rural Colombia: A Path towards Well-being and Peace Mission for the Transformation of Rural Areas], Departamento Nacional de Planeación [National Planning Department].

Analysing data between 2009 and 2015, the department of Chocó in the Pacific region was the only department which had not reduced multidimensional poverty (Gómez Arteaga, Quiroz Porras and Ariza Hernández, 2017[42]). An analysis of spatial poverty in the Caribbean region highlights clusters of high and low poverty that cross boundaries of municipalities and departments (Tapias Ortega, 2017[43]).

Agricultural departments have the highest poverty levels, also a result of weak property rights and a high concentration of land ownership. Rural development policy has promoted equitable access to credit and land, as well as housing, basic sanitation, education and health (OECD, 2015[44]). In 2015, The “Rural Mission”, which has already been mentioned, for instance developed a medium- and long-term strategy to close rural‑urban gaps, which includes education as one element (see Box 1.2).

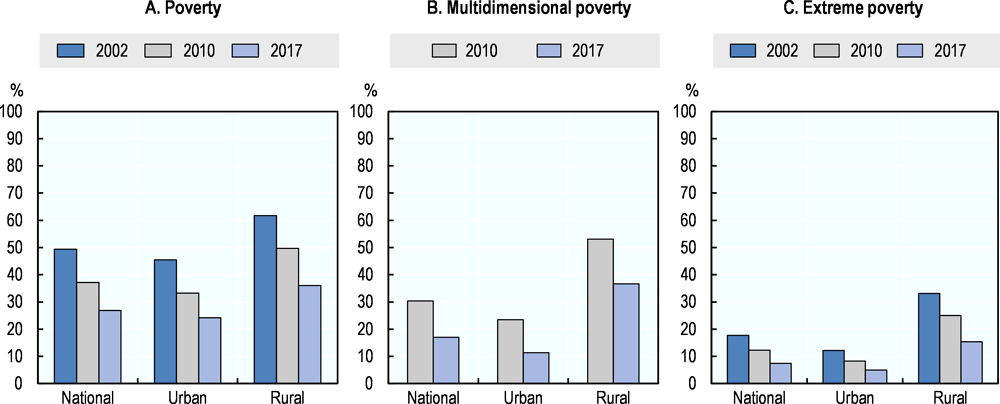

As analysed above, poverty for the country as a whole has declined and so has poverty in rural areas. Gaps between rural and urban areas, however, remain substantial. In 2017, the share of rural Colombians living in multidimensional poverty was still more than twice as high as for urban dwellers (see Figure 1.7). As the country´s 3rd National Agricultural Census indicates, multidimensional poverty remains even higher in remote areas (45.7% in 2014 vs. 54.3% in 2005) (DANE, 2016[45]).

Figure 1.7. Differences in poverty rates between rural and urban areas

Notes: The poverty rate measures the percentage of the population with a per capita income in the household below the poverty line, in relation to the total population. The extreme poverty rate measures the percentage of the population with a per capita income in the household below the extreme poverty line, in relation to the total population. Both measures are based on income data from the Integrated Household Survey. The Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) is based on five dimensions (education, living conditions of children and youth, health, work, access to public services and housing) and 15 indicators. People are considered poor if deprived of at least five of these 15 indicators. Data are obtained from the National Quality of Life Survey.

Urban refers to municipal townships (cabecera municipal), rural to the remaining areas (resto municipal), including both populated centres (centros poblados) and rural scattered areas (rural disperso).

Sources: DANE (2018), Gran Encuesta Integrada de Hogares (GEIH) [Integrated Household Survey], https://www.dane.gov.co (accessed on 01 June 2018); DANE (2018), Encuesta Nacional de Calidad de Vida (ECV) [National Quality of Life Survey], https://www.dane.gov.co (accessed on 01 June 2018).

Inequalities in social and economic development based on geography particularly affect Colombia´s ethnic minorities which are highly concentrated in regions with higher poverty and, in the case of indigenous peoples, in rural areas. Individuals from Afro‑Colombian and indigenous communities have lower levels of well-being over the course of their life in a number of dimensions, including health, nutrition and education. Individuals belonging to an ethnic minority have also suffered disproportionately from violence and forced displacement (Cárdenas, Ñopo and Castañeda, 2014[46]).

Achieving decreases in regional inequalities and rural poverty will be crucial in improving the well-being of all Colombians, including Afro-Colombians and indigenous peoples, in creating lasting peace as well as reviving rural areas and stemming rural to urban migration. Migrants may not have the skills required to succeed in the urban labour market and in turn contribute to increasing urban poverty (OECD, 2014[36]). Internal migration and forced displacement also pose challenges for planning the provision of education in response to falling and increasing student numbers.

Box 1.2. Colombia’s “Rural Mission” (Misión para la Transformación del Campo)

The National Planning Department (DNP), in collaboration with the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MADR), has recently developed a strategy for rural development for the medium and long term. The recommendations were also taken up in the National Development Plan 2014‑18.

As the strategy states, “the central objective of the Misión para la Transformación del Campo is to propose state policies so that rural society can manifest its full potential, contributing to national well-being and making a decisive contribution to the construction of peace. Peace also offers immense possibilities for rural development, agricultural and non-agricultural, and allows us to think about the advancement of rural areas as one of the pillars of the future development of the country” (p. 4).

The strategy is based on a participatory territorial approach as one of its three key principles and adopts the conception of “new rurality” (nueva ruralidad). This conception seeks to overcome the rural-urban dichotomy and looks more at the relationships, synergies and complementarities to close gaps between rural and urban areas.

The strategy proposes six lines of action within a framework that includes economic, social and environmental aspects of rural development: social rights, productive inclusion, competitiveness, environmental sustainability, territorial development and institutional adjustment. The social rights agenda set the goal to eliminate rural-urban gaps by 2030 in the provision of social services (nutrition, education, health, social protection, housing, water and sanitation).

In education, it sets the objective to not only close rural gaps in attainment but “to guarantee a relevant and quality education that facilitates productive inclusion and encourages creativity and innovation […] and that education is a true instrument for social mobility, both for youth deciding to stay in rural areas and those migrating to the cities” (p. 51).

Recommendations for the education sector include the creation of a permanent and specialised directorate within the ministry of education to design adequate and differentiated policies for the rural sector. The report also highlights the following:

The quality assurance and regulation of flexible school models and the creation of new pedagogical models for secondary education.

Differentiated education policy according to types of rurality depending on existing demand and population density, possibilities for school transport, infrastructure and teacher supply; differentiated strategies beyond the reorganisation of the school network for schools and students in remote areas; significant investments in infrastructure and transport.

A relevant curriculum in secondary education that entails elements of food security and entrepreneurship; the great potential of productive pedagogical projects to develop relevant knowledge and skill.

Efforts to strengthen professional tertiary education (technical, technological and professional-technical programmes), e.g. through articulation with upper secondary education; the creation of new courses by the National Learning Service (SENA); the development of virtual and distance learning; the development of the educational offer of Regional Centres of Higher Education (CERES); the creation of new sites of public universities; and support for rural youth to access tertiary education.

Greater articulation between the Ministry of National Education (MEN) and the National Learning Service (SENA), and a review of the offer of tertiary education in rural areas.

Source: DNP (2015), El Campo Colombiano: Un Camino hacia el Bienestar y la Paz Misión para la Transformación del Campo [Rural Colombia: A Path towards Well-being and Peace Mission for the Transformation of Rural Areas], Departamento Nacional de Planeación [National Planning Department], Bogotá, DC.

School system

Governance of the school system

Goals and objectives of school education

Education in Colombia is both a fundamental right and a public service with a social function as defined in the Constitution adopted in 1991 (Art. 67) – the previous Constitution having been enacted since 1886. As a fundamental right, education is essential and integral to the development of the individual. As a public service, the state guarantees the provision of education. Education shall provide access to knowledge, science, know-how and all other cultural goods and values. It shall educate Colombians in the respect of human rights, peace and democracy and in the practice of work and leisure to enhance culture, science and technology and to protect the environment.

These general objectives of education would later be further specified in the General Education Law of 1994 (Law 115) in the form of 13 general goals for non-formal, informal and formal education. The General Education Law also defines common objectives for all levels of formal education, from pre-primary to upper secondary levels, as well as specific objectives for different levels (for details see Sánchez (2018[6])).7 According to the Constitution, the state, society and family are responsible for ensuring education quality and for promoting access to public education.

Distribution of responsibilities

School education in Colombia is mainly regulated by the Constitution of 1991 and the General Education Law of 1994, which have already been mentioned, as well as the Single Regulatory Decree of Education (Decree 1075) of 2015 and Law 715 of 2001. While Decree 1075 combines all education decrees enacted before as well as after 2015, Law 715 regulates Colombia’s system of fiscal transfers across levels of governance, the General System of Transfers (Sistema General de Participaciones, SGP). This revenue sharing mechanism also distributes funding for school education.

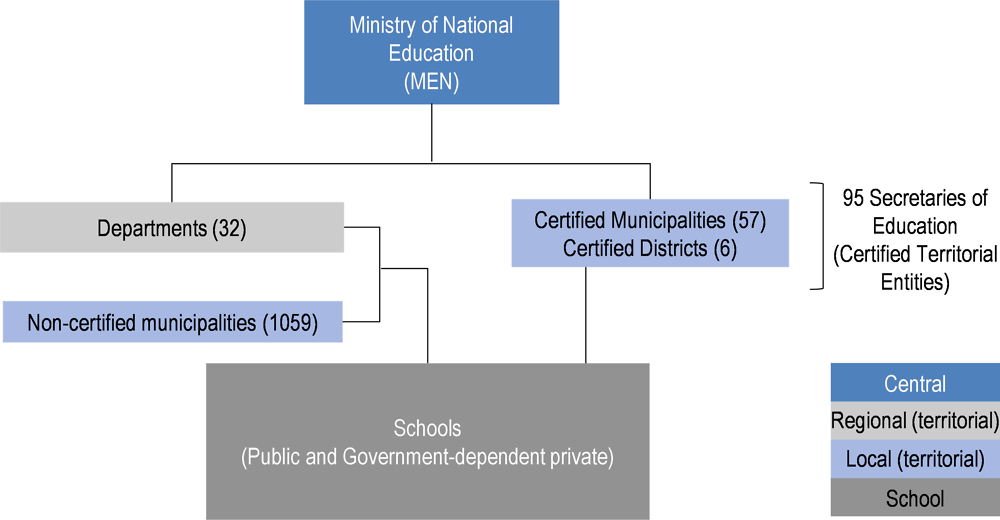

Colombia was one of the first countries in Latin American to begin decentralising its school system and, although a unitary state, Colombia has become one of the more decentralised countries in the region. Following first steps to decentralise education to municipalities, districts and departments in the late 1980s and the early 1990s before and after the adoption of the new Constitution, the reform of the fiscal transfer system in 2001 further clarified responsibilities for each level of government.8 For school education, there are thus three levels of administration: central, territorial (regional and local) and school levels (see Figure 1.8). The governance framework is the same for all levels of education from pre‑primary to upper secondary, and the same authorities are responsible for regulating, funding and providing education for all these levels.

Figure 1.8. Levels of governance for school education in Colombia

Source: Adapted from Sánchez, J. (2018), OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools: Country Background Report for Colombia, http://www.oecd.org/education/schoolresourcesreview.htm.

At the central level, the Ministry of National Education (Ministerio de Educación Nacional, MEN, hereafter ministry) is the head of the sector. According to the General Education Law, the ministry holds four types of responsibilities: i) policy and planning; ii) monitoring; iii) administration; and iv) regulation.9 The ministry formulates policies and objectives, regulates provision, establishes criteria and guidelines, monitors the system and provides technical advice and support, but does not directly provide education. In recent years, the ministry has taken on an increasingly important role in the design and implementation of programmes that target individual schools.

In school education, the ministry works with three different entities: the National Institute for the Blind (Instituto Nacional para Ciegos, INCI), the National Institute for the Deaf (Institutional Nacional para Sordos, INSOR) and the Colombian Institute for Educational Evaluation (Instituto Colombiano para la Evaluación Educativa, ICFES). INCI and INSOR promote public policy for people with a disability. ICFES is the institution responsible for evaluation and assessment in education and for carrying out research on the quality of education. All of these three institutions have administrative autonomy and an independent budget.10

Decentralisation in education has been managed by a process of certification. While all departments and districts gained the status of a certified territorial entity (entidad territorial certificada, ETC) in 2002 with the adoption of Law 715, all municipalities with at least 100 000 inhabitants and municipalities judged to have sufficient technical, financial and administrative capacity were certified by 2003. Other municipalities have since had the possibility to apply to their department for certified status and to provide education. Departments should provide technical and administrative support to their municipalities to gain certification (MEN, 2004[47]). As shown in Figure 1.8, 95 territorial entities were certified and had their own certified Secretary of Education in 2018: 32 departments, 6 districts and 57 municipalities.

The certified territorial entities are responsible for ensuring coverage and quality, defining and implementing education policy and monitoring the quality of provision in both public and private schools in their territory. They manage the teaching staff of their schools and financial resources received from the General System of Transfers (Sistema General de Participaciones, SGP), their own revenues, and oil and mining royalties.

The provision of education in the non-certified municipalities is the responsibility of the certified Secretaries of Education of the departments, but departmental education authorities co-ordinate with the municipalities’ authorities, such as the Secretary of Culture and Sports, in fulfilling this responsibility. Non-certified municipalities support the management of the teaching staff and provide data and information to their department. They also manage a small amount of financial resources they receive from the General System of Transfers (SGP) and can contribute their own resources for school infrastructure, maintenance and quality.

The education of children and young people from Colombia’s ethnic minorities has been regulated by a specific decree (Decree 804 of 1995) and schools have had the possibility of offering ethnic education programmes (programas de etnoeducación) developed together with the local community. A process is, however, underway to provide ethnic groups with greater autonomy through the creation of their own intercultural education systems (Sistemas Educativos Propios e Interculturales).

Among these, the Individual Indigenous Educational System (Sistema Educativo Indígena Propio, SEIP), which has been developed since 2010 together with the indigenous communities and was close to completion at the time of writing, is the most advanced. Through this system, administrative, pedagogical and organisational responsibility will be transferred to the indigenous territories, which will function similarly to the certified territorial entities. In general, ethnic communities must be consulted for all policies that concern them, a process led by the Ministry of the Interior.

Since the early 1990s, schools have substantial autonomy in defining their curriculum based on the General Education Law (Art. 77). Every school must develop and put into practice an educational project (Proyecto Educativo Institucional, PEI) together with the school community. Schools in Colombia also have some budgetary autonomy through the management of their own educational service fund (Fondos de Servicios Educativos, FSE) but little influence on the selection or dismissal of their teaching staff who are employed by their Secretary of Education. Responsibility for the management and administration of schools lies mainly with the school’s principal and directive council (consejo directivo). Schools should provide for the participation of the entire school community and also have an academic council, a school coexistence committee, a parent’s association and a student council.

Policy making and stakeholder involvement

The planning of public policy in general and also for education is based on development plans designed at the national and subnational levels for a period of four years. The government plan of the successful candidate presented during the electoral period is approved by the respective chamber of elected representatives – Congress at the national level, and Departmental Assembly and Municipal Council at regional and local (territorial) levels. Development plans guide budget and policy decisions for the term in office and provide a basis for evaluating the achievement of set goals and objectives. The development plans of departments and municipalities must be aligned with the national plan. In education specifically, the plans of non-certified municipalities must also be co‑ordinated with the respective department.

The process of transforming the president’s electoral strategy into the National Development Plan (Plan Nacional de Desarrollo, PND) is led by the National Planning Department (Departamento Nacional de Planeación, DNP)11 and supported by the Ministry of Finance and Public Credit (Ministerio de Hacienda y Crédito Público). The plan entails a medium-term expenditure framework that guides annual budget decisions as well as a multiannual investment budget that contains the country’s main investment programmes for implementing the plan.

The plan is widely publicised before its approval and consulted extensively with representatives of departments and municipalities, ethnic minorities and civil society. Prior to consideration and approval by Congress, the plan has to be endorsed by the CONPES (Consejo Nacional de Política Económica y Social), the country’s advisory body on economic and social policy. Once passed by Congress, the plan is enacted into law (Ley Orgánica del Plan de Desarrollo).

The National Development Plan for 2014-18, Todos por un Nuevo País: Paz, Equidad y Educación, established education as one of three key pillars for economic and social development alongside peace and equity (see Box 1.3). The priorities defined in the plan also constitute the basis for formulating national policies and programmes funded through the ministry of education’s budget for investment projects.

The education ministry establishes a longer vision and planning horizon for education through the country’s ten-year education plans (Plan Nacional Decenal de Educación, PNDE). The current ten-year plan was established for 2016-26 following the extensive participation of civil society, including schools and students, and technical advice of experts and researchers through an academic commission (see Box 1.4).

The General Education Law established advisory bodies for education policy and planning and platforms for regular stakeholder participation and co-ordination across levels of governance. As stipulated in the law, a national education board (Junta Nacional de Educación, JUNE) and its technical secretaries should provide ongoing advice to the ministry, propose programmes and projects, make suggestions on proposed legislation and regulations, promote research, and monitor and evaluate the system.

Education boards at the level of departments, districts and municipalities (Juntas Departamentales y Distritales de Educación, JUDE, and Juntas Municipales de Educación, JUME) should advise, verify, oversee and approve politics, plans and curricula for their territory. These boards are composed of government officials of different levels and areas, representatives of the education community, the productive sector, and ethnic communities. All of these advisory bodies have, however, stopped functioning in recent years. An agreement between the government and the largest teacher union from 2017 nevertheless envisages re-establishing these platforms.

Box 1.3. The National Development Plan 2014-18: Todos por un Nuevo País: Paz, Equidad y Educación

The National Development Plan (PND) for 2014-18 set various specific objectives and lines of action to improve the access, quality and relevance of education, with the overarching long-term goal to “close the gaps in access and quality to education, between individuals, population groups and between regions, bringing the country to high international standards and achieving equality of opportunities for all citizens” (p. 85). The ultimate objective is to become “the most educated” country in Latin America by 2025.

Among the lines of actions for school education, the following stand out:

Early childhood education (Educación inicial): In recognition of early childhood education as a fundamental right for children under the age of six, the plan contemplates that the national government regulates the articulation of this level with the education system within the framework of comprehensive care/integral attention (atención integral) encompassing health, nutrition, protection and early childhood education in different forms of provision within the framework of the From Zero to Forever (De Cero a Siempre) strategy.

Teacher excellence (Excelencia Docente): Building on and strengthening the implementation of the Let’s All Learn Programme (Programa Todos a Aprender, PTA) initiated as part of the PND for 2010-14; taking steps to attract highly qualified candidates into the profession, to improve initial teacher education and professional development, to improve the remuneration of teachers and opportunities for promotion of teachers in the new teacher statute; and strengthening school leadership.

Full-day schooling (Jornada Única): Longer and better-quality instruction time for children in pre-school, primary and secondary education. The plan established full-day schooling to be implemented gradually by mayors and governors until the year 2025 in urban areas and until 2030 in rural areas, with a goal of 30% coverage by 2018. As part of this policy, the development of an infrastructure plan (Plan Maestro de Infraestructura Educativa), which has resulted in the creation of an Educational Infrastructure Fund (Fondo de Financiamiento de la Infraestructura Educativa, FFIE).

Upper secondary education for all (Educación media para todos): The plan proposes to advance in the net coverage of this level of school education from 41.3% in 2013 to 50.0% in 2018 and to reach a gross coverage of 83%. To ensure that young people in the country study up to Year 11, the plan established the design of gradual implementation plans with certified territorial entities and established upper secondary education as mandatory – previously, only education up to Year 9 was compulsory.

Source: DNP (2015), Plan Nacional de Desarrollo: Todos por un Nuevo País Tomos 1 y 2 [National Development Plan: Everyone for a New Country Volumes 1 and 2], Bogotá, DC; Law 1753 of 2015.

Box 1.4. National 10-year Plan for Education 2016-26: El Camino Hacia la Calidad y Equidad

The development of the ten-year national education plan for 2016-26 was based on an inclusive and participatory methodology, guided and validated by the Organization of American States (OEA) and the Regional Office of UNESCO for Latin America and the Caribbean (ORELAC).

Three collegiate bodies were created to ensure broad representation:

A management commission, supporting the drafting of the plan based on the input provided through the different participation mechanisms. The commission is also responsible for monitoring and evaluating the implementation of the plan and for articulating the work of different levels of governance.

A regional commission, promoting the involvement of the education community, municipalities, departments and civil society at the local level.

An academic commission, formulating the main challenges for the next ten years based on the input provided by the general population.

A number of innovative tools were developed to facilitate the participation of society. A survey was distributed to more than one million citizens. Children across the country contributed with about 6 000 paintings. Based on these inputs, 135 thematic forums were organised at national and regional levels, with more than 6 500 participants.

The plan should be a roadmap providing general and flexible guidance about the future of education. The participatory nature of developing the plan highlights that not only the state, but schools and others are responsible for contributing to reaching the set goals.

The ten challenges identified by the academic commission are the following:

Regulating and specifying the reach of the right to education.

Building a system that is fully articulated, participatory, decentralised, and that counts with effective mechanisms for reaching agreements.

The development of general, pertinent and flexible curricular guidelines.

The construction of a public policy for teacher education.

Changing the paradigm that has dominated education until today.

The pertinent, pedagogical and general use of new and diverse technologies to support teaching and the creation of knowledge, learning, research, and innovation.

Building a peaceful society based on equity, inclusion, respect for values and gender equality.

Prioritising the development of the rural population through education.

The importance that the state gives to education will be measured through the government investment in the sector as a whole and as a percentage of the GDP.

Promoting research that leads to the creation of knowledge at all levels of education.

Source: MEN (2017), Plan Nacional Decenal de Educación 2016-2026: El Camino Hacia la Equidad y la Calidad [National 10-year Plan for Education 2016-2026: The road towards equity and quality], Ministerio de Educación Nacional [Ministry of National Education], Bogotá, DC.

As also established by the General Education Law, central and subnational authorities organise annual education forums (Foros Educativos Municipales, Distritales, Departamentales y Nacional) to share experiences, reflect about the state of education and present recommendations to improve education to the respective authorities.

In general, different stakeholders within the education community shape education policy. Colombia’s largest teacher union, the Federación Colombiana de Trabajadores de Educación (FECODE), has played a prominent role in improving and protecting the working conditions of teachers. But the union has also shaped education policy more broadly. For instance, following a teacher strike in 2017, the government and the teacher union agreed on issues related to career progression, salary levels and bonuses, and health and pension benefits. The agreement, however, also took up demands for a reform of school funding, the expansion of early childhood education and care, the implementation of full-day schooling and peace education (MEN and FECODE, 2017[48]). There are also teacher unions at subnational levels, such as the Asociación Distrital de Educadores (ADE) in Bogotá and the Sindicato de Maestros del Tolima (SIMATOL).

Other groups, to mention just a few, include national student associations, such as the Asociación Nacional de Estudiantes de Secundaria (ANDES), the private sector – through the Asociación Nacional de Empresarios de Colombia (ANDI), for example – and civic and social foundations, such as Empresarios por la Educación and Fundación Compartir at a national and Proantioquia at a regional level. International organisations, such as the Organización de Estados Iberoamericanos (OEI) or UNESCO, also shape education policy and debate.

Structure and organisation of the school system

Organisation of levels of education and education programmes

Under the General Education Law, formal education is defined as education that is offered by approved institutions, organised in a sequence of cycles and progressive curricular standards, and leads to academic titles and degrees. According to the law, formal education is divided into three levels:

pre-school education (educación preescolar), which is composed of pre‑kindergarten (pre-jardín), kindergarten (jardín) and a transition year/Year 0 (año de transición)

basic education (educación básica), which consists of a first cycle of primary education (educación básica primaria) and a second cycle of lower secondary education (educación básica secundaria)

upper secondary education (educación media).

Table 1.1 illustrates Colombia’s system of school education as well as transitions between earlier and later levels of the education system and other types of provision.

Based on Colombia’s Constitution of 1991, compulsory education lasts ten years, from the age of 5 to 15, comprising the transition year and all of basic education. Recently, compulsory education has however been extended to the upper secondary level. As set out in the country’s National Development Plan for 2014-18, this is being introduced gradually and upper secondary education will be compulsory for all students in urban areas by 2025 and in rural areas by 2030. The analysis in this report is based on upper secondary education being part of compulsory education.

Table 1.1. School education and transitions in Colombia

|

ISCED 2011 |

Theoretical age |

Year |

Levels and programmes |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tertiary education (ISCED 5-8) / Higher teaching school (ISCED 4) |

|||||

|

VERTICAL TRANSITIONS |

|||||

|

ISCED 3 |

16 |

11 |

Upper secondary (General/Vocational) |

HORIZONTAL TRANSITIONS |

Certificate of Professional Aptitude (SENA) (ISCED 5) |

|

15 |

10 |

||||

|

ISCED 2 |

14 |

9 |

Lower secondary (Second stage of Basic education) |

||

|

13 |

8 |

||||

|

12 |

7 |

||||

|

11 |

6 |

||||

|

ISCED 1 |

10 |

5 |

Primary (First stage of Basic education) |

||

|

9 |

4 |

||||

|

8 |

3 |

||||

|

7 |

2 |

||||

|

6 |

1 |

||||

|

ISCED 0 |

5 |

0 (Transition year) |

Pre-school (Integral attention to early childhood) |

Provision for 0‑5 year-olds (ICBF) (ISCED 0) (Integral attention to early childhood) |

|

|

4 |

-1 (Kinder) |

||||

|

3 |

-2 (Pre-kinder) |

||||

Source: Adjusted from Sánchez, J. (2018), OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools: Country Background Report for Colombia, http://www.oecd.org/education/schoolresourcesreview.htm.

The School Resources Review of Colombia focuses on education from the transition year to upper secondary education. It also considers transitions from early childhood and pre‑school education to school and from school education to tertiary education. Previous OECD Reviews of National Policies of Education of Colombia provide in-depth analyses of early childhood education and care and tertiary education (see OECD (2016[49]) and OECD/IBRD/The World Bank (2013[50])).

Pre-school education provided by certified territorial entities lasts for 3 years from the age of 3 to 5. Children and their mothers can also attend community, family and institutional modalities of early childhood education and care from birth until the age of five. These more care-oriented forms of early childhood education are managed by the Colombian Institute of Family Welfare (Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familial, ICBF) and its providers, and operate in parallel to school-based pre-school education for 3‑5 year‑olds.

All early childhood education and care is subject to Law 1804 of 2016 which institutionalises Colombia’s multi-sectoral policy for comprehensive early childhood development De Cero a Siempre. In 2017, 960 186 children were enrolled in school-based pre-school education, 746 002 of which in urban areas, and 214 184 in rural areas (see Table 1.2 for enrolments in 2017) (Sánchez, 2018[6]).12 Based on data from the ICBF, about 1 million children attended early childhood education and care (MEN, 2017[51]).

Between the ages of 6 and 14, children study 5 years of primary education (Years 1 to 5 for 6-10 year-olds) and 4 years of lower secondary education (Years 6 to 9 for 11‑14 year‑olds). With the completion of lower secondary education, students receive a basic education certificate (Certificado de Estudios de Bachillerato Básico) which entitles students to enrol in upper secondary education. In 2017, approximately 7.3 million students were enrolled in basic education. About 5.4 million students attended this level of education in urban areas and 1.9 million students in rural areas (Sánchez, 2018[6]).

Upper secondary education lasts for 2 years (Years 10 and 11 for 15‑16 year‑olds) and enrolled about 1 million students in 2017, 885 814 in urban areas and 180 316 in rural areas. Upper secondary students can choose between a general and a vocational programme. General programmes (bachillerato académico) focus on sciences, the arts or the humanities. Vocational programmes (bachillerato técnico) provide a specialisation in any of the productive or service sectors, such as commerce, finance and administration, information technology, agriculture and fishing, and tourism (Sánchez, 2018[6]). In 2017, 61.6% of students in upper secondary education were enrolled in a general programme, 38.4% in a vocational programme (data provided by the ministry).13

After completion of basic education, students have traditionally been able to undertake vocational training provided by the National Learning Service (SENA) – an independent and autonomous public institution ascribed to the Ministry of Labour and built on the partnership between government, business and labour that provides technical and technological programmes at tertiary level and short vocational programmes. The SENA also collaborates in the provision of upper secondary vocational programmes in some schools, for example through the involvement of vocational trainers.

Colombia has 137 higher teaching schools (Escuelas Normales Superiores, ENS). These institutions offer all levels of compulsory education, but also specialise in pedagogy and initial teacher education for pre-primary and primary. Students can study a pedagogical specialisation (bachillerato pedagógico) in upper secondary education and take a two‑year complementary programme in in education and pedagogy at these schools. Enrolments in these initial teacher education programmes have been decreasing in recent years. In 2017, 12 443 students were enrolled in the four semesters of teacher education of a higher teaching school, 11.7% less than in 2012 (Sánchez, 2018[6]).

The total enrolment of students at all levels of school education has been decreasing in line with demographic trends. Looking at compulsory education in public and government-dependent private provision, enrolment decreased by 10.9%, from 8.5 million to 7.6 million students between 2010 and 2017. Enrolment in primary education decreased by 14.9%, the greatest drop among all levels. Enrolment trends differ between rural and urban areas. While enrolment in lower and upper secondary education has been decreasing in urban areas (10.28% and 13.09%), it has been increasing in rural areas (7.59% and 21.98%) (Sánchez, 2018[6]).

Organisation of schools into school clusters

Public schools in Colombia are organised in school clusters that group different school sites under a common leadership and management (more on this in Chapter 3).

Through a school cluster, individual school sites may offer only some levels of education but are linked with other sites to offer students a comprehensive offer of education from pre-primary to upper secondary education. Typically, the main school site offers all levels of education, while the remaining sites offer only some levels of education. At the upper secondary level, school sites can offer a general programme, a vocational programme or both types of programmes.

Table 1.2. Enrolment by sector and zone, 2017

|

Pre-primary |

Primary |

Lower secondary |

Upper secondary |

Total by zone and sector |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Public |

7 104 009 |

||||

|

Urban |

393 342 |

2 171 827 |

1 873 618 |

664 522 |

5 103 309 |

|

Rural |

181 101 |

1 082 803 |

577 471 |

159 325 |

2 000 700 |

|

Government-dependent private |

498 913 |

||||

|

Urban |

19 491 |

150 397 |

120 447 |

39 815 |

330 150 |

|

Rural |

17 809 |

100 543 |

40 903 |

9 508 |

168 763 |

|

Independent private |

1 750 189 |

||||

|

Urban |

333 169 |

704 009 |

436 953 |

181 477 |

1 655 608 |

|

Rural |

15 274 |

39 939 |

27 885 |

11 483 |

94 581 |

|

Total |

9 353 111 |

Note: Government-dependent private provision refers to providers and schools contracted by Secretaries of Education under different modalities in case of capacity constraints or other limitations. These providers receive public funding. In Colombia, contracted private provision is counted as part of public enrolments. Independent private providers do not receive public funding.

Source: Adapted from Sánchez, J. (2018), OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools: Country Background Report for Colombia, http://www.oecd.org/education/schoolresourcesreview.htm.

In 2017, Colombia had 9 881 public schools composed of 44 033 school sites. Four out of 5 sites were classified as rural, that is 80.2% or 35 329 school sites. The remaining 8 704 or 19.8% of school sites were classified as urban. On average, a rural public school has 5.9 sites, an urban public one 2.3 sites.14 The number of school sites within a school cluster, however, differs substantially across the country (Sánchez, 2018[6]).

Traditionally, schools and school sites in Colombia operate in double shifts of an estimated 5 to 6 hours a day (doble jornada), one in the morning and one in the afternoon. Schools may also offer a third shift in the evening, predominantly for adult education. Reportedly, urban school clusters are more likely than rural ones to offer multiple shifts of school education. The General Education Law however stipulates the requirement to offer students full-day schooling (jornada única) in all schools and the government has been making strides to lengthen the school day (see Chapters 2 and 3).

Organisation of private education

School education can be offered by public (matrícula oficial), government-dependent (matrícula oficial contratada) and independent private schools (matricula no oficial). The private provision of education is analysed in depth in Chapter 3.

Public education is provided directly through public schools managed by the Secretaries of Education of the certified territorial entity. Where there is limited capacity in terms of infrastructure or teaching staff, or another limitation, Secretaries of Education can provide education through various forms of partnerships with private providers, that is government-dependent private provision. There are also fully independent private schools that generally receive no public funding. In Colombia, statistics on enrolment distinguish public enrolment, which includes public and government-dependent private provision, and private enrolment, which refers to independent private schools.

Of the more than 9.3 million students enrolled in school and pre-school education in 2017, 81.3% were in the public system according to the Colombian definition, with 6.6% of these students, or 498 913 students, being served by a government-dependent private school contracted by the Secretary of Education. The remaining 18.7% were enrolled in independent private schools (see Table 1.2 above) (Sánchez, 2018[6]).

Organisation of education for particular groups of the population

The Constitution of 1991 defines all citizens as being born equal and Colombia as a social state (estado social de derecho) that must ensure equity and freedom from discrimination for any marginalised or vulnerable populations. Accordingly, the General Education Law defines particular groups of the population at risk of exclusion, poverty and the effects of inequality and violence: i) students with special needs or a disability and gifted students; ii) students who could not complete formal education or wish to gain further education (adult education); iii) students from one of Colombia’s ethnic minorities; iv) rural students; and v) students that require rehabilitation and reintegration into society (e.g. former members of armed groups).

Flexible school models (Modelos Educativos Flexibles, MEF) constitute a fundamental element in formal education to meet the diverse needs of these particular groups of students and adapt the curriculum and pedagogy. The ministry also formulates central guidelines for the education of vulnerable populations, most recently with a revised version in 2015 (Lineamientos generales para la atención educativa a población vulnerable y víctima del conflicto armado interno) and promotes policies and programmes for different vulnerable groups as described in the following paragraphs.

The education of ethnic minority populations, which amounted to 9.2% of enrolments in compulsory education in 2017, has already been mentioned.15 Colombia’s displaced population is another important group with special provisions, going back to the creation in 1997 of a National System for the Integral Attention for the Displaced Population (Sistema Nacional de Atención Integral a la Población Desplazada, SNAIPD, Law 387). Provisions were strengthened in 2011 with the Law for the Attention and Reparation of Victims of the Armed conflict (Ley de Atención y Reparación a Víctimas del Conflicto Armado, Law 1448).

The peace agreement places education for both victims and the demobilised combatants into the further focus of policy. In 2017, 5.9% of students enrolled in compulsory education were recognised as victims, encompassing a variety of different groups. Displaced students made up the largest share, followed by children of demobilised combatants and former child combatants. These figures do not include adolescents in the criminal responsibility system and victims of landmines (Sánchez, 2018[6]).

Education in rural areas has also been given new impetus with the peace agreement between the government and the FARC in 2016. As part of the comprehensive rural reform, it has been agreed to develop and implement a Special Rural Education Plan (Plan Especial de Educación Rural, PEER). At the time of writing this report, a revised version of the plan had been drafted but not yet been approved. The peace agreement sets out 13 goals that should be achieved through the implementation of the rural education strategy (see Box 1.5). Using the classification of rurality developed by the “Rural Mission”, almost 2 million, or 1 in 4 students, were enrolled in a rural school (24.2%) in 2016; 39.8% of these students in a remote area (MEN, 2017[51]).

Box 1.5. Objectives of the Special Rural Education Plan (Plan Especial de Educación Rural) as part of the peace agreement

The Peace Agreement between the government and the FARC, among others, entails the development of national plans to improve public services and infrastructure in rural areas as part of a comprehensive rural reform programme. For education, this includes actions in the form of a Special Rural Education Plan. The objectives for this plan agreed upon in the peace accords include the following:

Guarantee universal coverage with comprehensive/integral attention to early childhood.

Offer flexible models of pre-school, primary and secondary education, adapted to the needs of the communities and the rural environment, with a differential approach.

Implement the construction, reconstruction, improvement and adaptation of rural educational infrastructure, including the availability and permanence of qualified teaching staff and access to information technologies.

Guarantee free education for pre-school, primary and upper secondary school.

Improve conditions for access and permanence in the education system of children and adolescents through free access to tools, texts, school meals and transport.

Generate an offer of programmes and infrastructure for recreation, culture and sports.

Incorporate agricultural vocational training in upper secondary education (Years 10 and 11).

Offer scholarships with forgivable credits for the access of poorer rural men and women to technical, technological and university training at tertiary level, including, when appropriate, support for maintenance.

Promote the professional education of women in non-traditional disciplines for them.

Implement a special programme for the elimination of rural illiteracy.

Strengthen and promote research, innovation and scientific and technological development for the agricultural sector, in areas such as agroecology, biotechnology, soils, etc.

Progressively increase technical, technological and university quotas at tertiary level in rural areas, with equitable access for men and women, including people with disabilities. Special measures will be taken to encourage the access and permanence of rural women.

Expand the offer of technical, technological and university education in areas related to rural development.

Source: Mesa de Conversaciones [Conversation Roundtable] (2017), Acuerdo Final para la Terminación del Conflicto y la Construcción de una Paz Estable y Duradera [Final Agreement to End the Armed Conflict and Build a Stable and Lasting Peace], Bogotá, DC.

The Rural Education Programme (Programa de Educación Rural, PER) was a prominent previous initiative to improve education in rural areas. This programme evolved from the peasant marches of the 1990s and the Rural Social Contract pledged in 1996 as a commitment of the state to improve the quality of life of the rural population. It involved a first (2001-06, PER I) and a second phase (2008-15, PER II) and was funded through loans from the World Bank.

In its first phase, the programme worked with 120 non-certified municipalities in 30 departments; in the second phase with 36 certified territorial entities, reaching 72% of the non-certified municipalities. Covering pre-school to upper secondary education, the programme aimed to raise access to a quality education in rural areas, to prevent dropout from school and to make education relevant for the needs of rural students. Additional strategies focused on the improvement of basic competencies in language and mathematics in basic primary education and the teaching of English.

An increasing share of students is identified as having a disability or special needs: 1.75% of students had been diagnosed with a disability in 2016 – an increase of almost 60% since 2010. The government has established legislation for the rights of disabled people, which also cover education. To safeguard the rights of students with special needs, the government adopted Decree 1421 in 2017, committing the state to inclusive education.

Youth in conflict with the law and in the penal system constitute another noteworthy group. In 2015, the government adopted Decree 2383 to regulate the provision of their education within the framework of the Adolescent Criminal Responsibility System (Sistema de Responsabilidad Penal para Adolescentes, SRPA), together with central guidelines for Secretaries of Education to put these provisions into practice.

Quality, equity and efficiency of school education

Colombia has achieved important progress in increasing enrolment rates but challenges remain to expand coverage, smooth transitions and prevent dropout

While the enrolment rate for primary education has remained relatively stable, Colombia has experienced a substantial increase in enrolment in lower and upper secondary education over the last fifteen years. Colombia has reached universal enrolment for its 5‑14 year-olds defined as an enrolment rate of 90%, although the share of students in this age group is still lower than for all OECD countries and countries in the region with available data (Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica) (OECD, 2017[52]).

As can be seen in Table 1.3, the enrolment rate for primary education has been decreasing but the ministry of education considers this to reflect improvements in the reporting of enrolment data at the local level rather than an actual reduction of enrolment (MEN, 2017[53]). Enrolment rates in upper secondary education have seen the largest increase. Gross enrolment rates, that is the share of students enrolled regardless of age, help gauge the overall level of participation and the capacity of the system to enrol students in a given level of education. Between 2003 and 2017, gross enrolment rates in upper secondary education increased by almost 20 percentage points, from 60.5% to 80.1%. Lower secondary education shows an increase of about 16 percentage points, from 84.2% to 100.6%. Looking at net enrolment rates, that is taking into account the theoretical age at which a student should be enrolled in a given level of education, reveals a similar trend, with an increase of around 13 percentage points respectively (data provided by the ministry).

Table 1.3. Gross enrolment ratios (%)

|

Year 0 |

Primary |

Lower secondary |

Upper secondary |

Basic education |

Total |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2003 |

88.95 |

115.64 |

84.21 |

60.51 |

100.61 |

96.89 |

|

2007 |

90.33 |

119.19 |

95.60 |

70.65 |

106.84 |

100.87 |

|

2011 |

88.48 |

114.52 |

105.17 |

80.31 |

108.16 |

103.44 |

|

2017 |

84.35 |

102.09 |

100.56 |

80.11 |

99.69 |

96.41 |

Note: The gross enrolment ratio is defined as the number of students enrolled in a given level of education, regardless of age, expressed as a percentage of the official school-age population corresponding to the same level of education.

Source: Data provided by the Ministry of National Education based on the integrated enrolment system SIMAT.

Table 1.4. Net enrolment ratios (%)

|

Year 0 |

Primary |

Lower secondary |

Upper secondary |

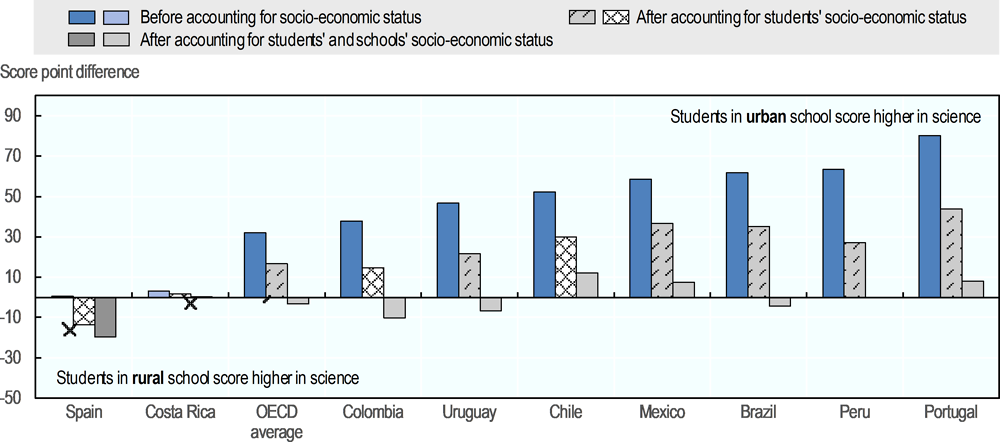

Basic education |