This chapter describes i) the main characteristics of the teaching profession; ii) the employment framework; and iii) initial education and ongoing teacher learning in Colombia. The teacher employment framework was reformed in 2002 while leaving the first framework in place for teachers recruited before 2002. The chapter covers both teacher statutes and the pending challenges in implementing the new statute successfully. While the statutes also regulate the employment of school leaders, school leadership is analysed in depth in Chapter 3. The chapter analyses strengths and challenges with a particular focus on the preparation and support for teachers to work with a range of learners, and the equitable and efficient recruitment of teachers, including to rural areas. Finally, it makes recommendations, highlighting the benefits of a more comprehensive vision of teacher professionalism built on collective capacities in schools.

OECD Reviews of School Resources: Colombia 2018

Chapter 4. The development of the teaching profession in Colombia

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law.

Context and features

Main characteristics of the teaching profession

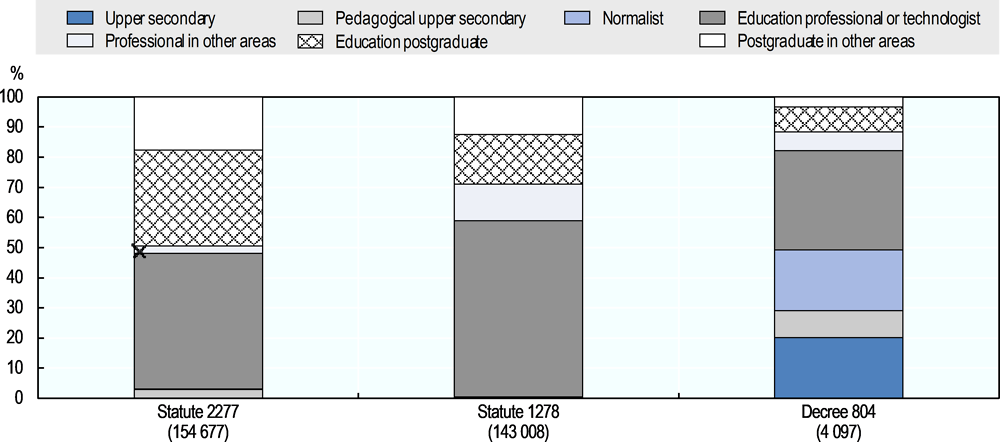

Colombia has reformed the employment framework of public school teachers in 2002, while leaving the country’s first framework introduced in 1979 in place. As a result, employment is regulated by two main teacher statutes: Decree Law 2277 of 1979 and Decree Law 1278 of 2002 (referred to as Statutes 2277 and 1278 throughout the chapter). These laws provide the general framework which is implemented through some collective bargaining between the government and the country’s largest teacher union (Federación Colombiana de Trabajadores de la Educación, FECODE).1 The main changes between statutes relate to entry requirements, recruitment, salaries and evaluation. Teachers from the old statute are free to change their employment status and join the new statute. Educators of ethnic minorities (etnoeducadores) are employed under a separate framework based on Decree 804 of 1995 which regulates ethnic education.

Table 4.1. Main employment characteristics of public school teachers in Colombia, 2017

Pre-primary to upper secondary education

|

Employment framework |

Statute 1278 (2002) |

Statute 2277 (1979) |

Decree 804 |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

In numbers |

168 332 |

134 944 |

6 610 |

309 886 |

|

In percentages |

54 |

44 |

2 |

|

|

Contract status |

Permanent staff |

Permanent vacancy |

Temporary vacancy |

|

|

In numbers |

247 664 |

46 243 |

12 211 |

|

|

In percentages |

80 |

15 |

4 |

Note: Data on contract status include teachers of all statutes. Data on permanent staff include teachers in probationary period. Teachers in a permanent vacancy fill a staff position which could not be filled through the official recruitment process (merit contest). Teachers in a temporary vacancy replace a permanent teacher that is only temporarily away. There are also temporary teachers (planta temporal) not reflected in this table, typically teachers taking part in an education initiative or programme.

Source: Authors’ elaboration on the basis of data in Sánchez, J. (2018), OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools: Country Background Report for Colombia, http://www.oecd.org/education/schoolresourcesreview.htm.

Table 4.2. Main demographic characteristics of public school teachers in Colombia, 2017

Pre-primary to upper secondary education

|

Age (%) |

Gender (%) |

Geographical location (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

18-41 |

50 and older |

Male |

Female |

Urban |

Rural |

|

31 |

38 |

66 |

44 |

64 |

34 |

Note: Data include teachers of all statutes. Data on age include both teachers and school leaders. All other data include teachers only.

Source: Authors’ elaboration on the basis of data in Sánchez, J. (2018), OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools: Country Background Report for Colombia, http://www.oecd.org/education/schoolresourcesreview.htm.

As of 2017, there were 309 886 public school teachers teaching pre-school to upper secondary education (see Table 4.1 and Table 4.2). Slightly more than half of all public school teachers hold their teaching position under the new Statute 1278 and it is estimated that it will take approximately 14 to 15 years until all teachers are employed under this employment framework, that is by 2032/33. About one in three public teachers work in rural areas which reflects the relatively high number of teachers required to provide education in less densely populated parts of the country. Given the concentration of indigenous students in rural areas, most of Colombia’s 6 610 educators of ethnic minorities work in a rural school (Sánchez, 2018[1]).

Teaching in Colombia is a predominantly female profession, but less so than in many other countries. As in many other countries, however, the share of female teachers decreases in higher levels of school education (see Table 4.3). Women are also less likely to assume school leadership roles, representing 44% of all school leaders. Colombian teachers are relatively old. Overall, 31% of public school teachers were aged between 18 and 41 years in 2017, and almost 40% of teachers were 50 years or older (Sánchez, 2018[1]). While the age groups and years available for comparison are not exactly the same, in Brazil and Chile, for example, 49% and 54% of teachers respectively were 39 years or younger, and 19% and 28% were older than 50 years in 2015 (OECD, 2017[2]).

Table 4.3. Share (%) of female teachers, 2015

|

|

ISCED 0 |

ISCED 1 |

ISCED 2 |

ISCED 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Colombia |

96 |

77 |

53 |

45 |

|

Brazil |

95 |

89 |

69 |

60 |

|

Chile |

99 |

81 |

68 |

56 |

|

Mexico |

94 |

68 |

53 |

47 |

|

OECD average |

97 |

83 |

69 |

59 |

Note: Teachers include staff in both public and private institutions.

Source: OECD (2017), Education at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2017-en, Table D5.2.

There were 120 488 teachers in independent private schools in 2016 which provide education to about 1 in 5 students in Colombia.2 Almost 40% of these teachers have more than 4 years of tertiary education and 38% teach at the primary level, which is the case for 46% of public school teachers. Private school teachers can be employed under the old statute (2277) but not under the new one (1278). They must have a professional degree in education or another field related to the subject they are teaching.

In case public education cannot be provided directly through a public school (e.g. due to limited staff or infrastructure), the Secretaries of Education of the certified territorial entities3 – departments, districts and municipalities – can contract and fund private providers. Teachers in these government-dependent private schools can either be provided by the Secretaries of Education or by the private provider depending on the type of contract. All teachers in these government-dependent private schools must fulfil the requirements for public teachers in terms of qualifications and experience (Sánchez, 2018[1]). For an in-depth discussion of private education, see Chapter 3.

Becoming a qualified teacher

Initial teacher education

There are three main routes to become a teacher in Colombia:

Completion of a first professional degree in education (licenciatura) at a tertiary institution (ISCED 2011 level 6).4

Completion of a complementary programme in education and pedagogy (Programa de Formación Complementaria, PFC) at a higher teaching school (Escuela Normal Superior, ENS) (ISCED 2011 level 4).

Side entry through completion of a postgraduate qualification (ISCED 7-8) or a programme in pedagogy (Programa de Pedagogía para Profesionales no Licenciados) (also see Sánchez (2018[1]) and MEN (2013[3])).5

Professional degrees in education

The most common way of obtaining an initial teacher education is studying for a first professional degree at a university’s education faculty or a university institution/technological school. A first professional degree in education requires four to five years of study and allows graduates to teach at all levels of pre-school and school education depending on the emphasis of the degree programme. Students can choose between public and private institutions and between different modes of study (full-time attendance, part-time attendance and distance-learning programmes).

Based on the principle of autonomy for tertiary institutions, education faculties are free to define their curricula and plans of study but need to comply with general requirements of Colombia’s quality assurance system for tertiary education (Sistema Nacional de Acreditación, SNA). There are two types of quality assurance processes:

All institutions, as well as individual programmes, are subject to an evaluation by the National Inter-sectorial Commission for Higher Education Quality Assurance (Comisión Nacional para el Aseguramiento de la Calidad de la Educación Superior, CONACES). This evaluation authorises programmes to become part of the register of qualified programmes (registro calificado). Evaluation is based on quality criteria for curriculum profiles, basic and professional competencies, mobility, teaching staff and pedagogical practice set by the Ministry of National Education (Ministerio Nacional de Educación, MEN, hereafter ministry/ministry of education).

The second type of high-quality accreditation (Acreditación de alta calidad) granted by the National Accreditation Council (Consejo Nacional de Acreditación, CNA) is voluntary. Based on a peer evaluation by members of the academic and research community according to specified quality criteria, it functions as a process to encourage continuous self-evaluation, self-regulation and improvement of institutions and programmes (OECD, 2016[4]).

Higher teaching schools

As in other countries in Latin America, higher teaching schools have traditionally played an important role for teacher education in Colombia (Ávalos, 2008[5]). Emerging out of the tradition of normal schools (escuelas normales), the first of which was founded in Colombia in 1822, higher teaching schools today offer two years of post-secondary non‑tertiary teacher education (Programa de Formación Complementaria, PFC) in addition to all other levels of school education. A teaching certificate from a higher teaching school allows graduates to teach in pre-primary and primary education as “normalists” (normalistas). Students from a higher teaching school can progress directly to the first semester of their post-secondary programme after completing upper secondary education with a focus on pedagogy (bachillerato pedagógico). Other students can enter a higher teaching school by completing five instead of four semesters.

Higher teaching schools are under the administration of the Secretary of Education of their certified territorial entity. They are autonomous in designing and developing the curriculum and study programme for their complementary programme, but it needs to be authorised by the ministry on the basis of a regular quality assurance process by CONACES, the national quality assurance body for tertiary education.

In 2018, there were 137 higher teaching schools, 129 of which were public and 8 private; 12 443 students were enrolled in initial teacher education at a higher teaching school in 2017. With the fulfilment of additional quality requirements, higher teaching schools can offer their complementary programme through distance education. In 2015, three higher teaching schools offered this option (MEN and ASONEN, 2015[6]).

Side entry through a postgraduate qualification in education or a programme in pedagogy for professionals in other areas

Graduates with tertiary degrees in other disciplines can follow alternative routes into teaching, mainly as a subject teacher in secondary education (docente de área de conocimiento en educación básica secundaria y media). A university graduate with a degree in mathematics can, for example, become a mathematics teacher. Graduates from other disciplines can either take a specialisation,6 master’s degree or PhD related to education (ISCED levels 7-8), or start teaching and follow a pedagogical programme offered at a tertiary institution. These pedagogy programmes need to comply with central guidelines and requirements for curriculum, length and mode of study.

Recruitment process

Permanent teaching positions

For most teachers, entry into the teaching profession is governed by the new teacher statute (1278) and its successive modifications, in particular, Decree 915 adopted in 2016. These regulations also apply to school leadership roles, although with some changes. For instance, while candidates for teaching do not need any experience, candidates interested in school leadership must have acquired a minimum number of years of teaching experience. School leadership is analysed in depth in Chapter 3.

The recruitment process of teachers into permanent staff positions (professor de planta/nombramiento en propiedad) is based on a merit contest (concurso de mérito). The merit contest was organised for the first time in 2004 and has been administered since 2006 by the National Civil Service Commission (Comisión Nacional del Servicio Civil, CNSC) with involvement from the ministry of education and the Colombian Institute for Educational Evaluation (Instituto Colombiano para la Evaluación de la Educación, ICFES). Prior recruitments were organised by individual Secretaries of Education.

As already stated, no previous experience is required for teachers to access the merit contest while the minimum qualifications required depend on the type of teacher. To apply, pre-school and primary teachers need to hold a tertiary degree in education/pedagogy (licenciatura) or have completed a higher teaching school (ENS). Subject teachers (docentes de áreas de conocimiento) need a tertiary degree in education or a tertiary degree in a relevant knowledge area other than education combined with a relevant postgraduate qualification or a programme in pedagogy as explained above.

Merit contests are called separately for each certified territorial entity (department, district or certified municipality) and specify the vacancies available within that territory. The overall number of teaching positions in a certified territorial entity depends largely on staff plans approved by the ministry in line with technical relations for the ratio of students to teachers and teachers per group of students. These staff plans also determine financial resources for teachers allocated through Colombia’s system for sharing revenues across levels of governance (Sistema General de Participaciones, SGP). Secretaries of Education can hire additional teachers with their own resources, but this is the exception.7

Secretaries of Education and schools are responsible for reporting the number of vacancies available in their territory to the ministry based on student enrolments – broken down by education level, area and type of school. Candidates must choose the one education authority they wish to apply for in that merit contest. Teachers are then employed by the Secretary of Education of their certified territorial entity where they make up a substantial part of public employment. In 2012, teachers and education staff constituted 29.1% of public employment at the regional level (OECD, 2013[7]).8

Successful candidates select their preferred position in the Secretary of Education they applied to through a public audience (audiencia pública), based on their ranking in the recruitment process. Lists of eligible candidates are valid for two years. Once all successful candidates have chosen their preferred vacancy or decided not to choose any position, the National Civil Service Commission creates two lists of teachers eligible for permanent positions, one by department and one for the country as a whole. Successful candidates then start their probationary period. Probationary periods last until the end of the ongoing school year, but for a minimum of four months, and entail an evaluation by the school principal at the end of the school year (Evaluación de período de prueba).

Temporary teaching positions

Teachers who fail to pass the merit contest can be employed as provisional or contract teachers (provisionales/nombramiento provisional) to i) fill a permanent staff position which could not be filled through the merit context (“temporary position in a permanent vacancy”/provisional en una vacante definitiva); or ii) replace a permanent teacher who is only temporarily absent, for instance on extended sick leave or on probation in another school (“temporary position in a temporary vacancy”/provisional en una vacante temporal) (see Table 4.1 and Table 4.2). All these provisional positions which are paid with resources distributed through the country’s revenue sharing system (Sistema General de Participaciones) are part of the approved staff plans for Secretaries of Education.

Since 2016, Secretaries of Education need to fill temporary positions in a permanent vacancy through a Pool of Excellence (Banco de la Excelencia). Temporary teachers in a temporary vacancy can be filled on a discretional basis. The financial compensation of provisional teachers is the same as that of teachers in permanent staff positions in the respective statute and thus depends on their level of qualification. Unlike permanent teachers, teachers under this type of contract however cannot progress up the salary scale or take part in the related competency assessment for promotion as explained below.

In addition to these two types of provisional or contract teachers, there are also temporary teachers (planta temporal) who replace teachers in particular situations, such as teachers working as tutors in the programme Let’s All Learn (Programa Todos a Aprender, PTA).

Educators of ethnic minorities (etnoeducadores)

There are three types of educators in Colombia for different ethnic minorities: Raizal, Afro-Colombian and indigenous. In 2017, students from ethnic minorities represented 10.8% of enrolments in compulsory education (820 337 students). About half of these students were from Afro-Colombian communities, the other half from indigenous peoples (51.7% and 48.3% respectively) (data provided by the ministry of education).9 As stipulated in Decree 804 which regulates ethnic education, educators for these minorities should be recruited in negotiation between the ethnic communities and the responsible Secretary of Education giving preference to members of the local community.

The decree on ethnic education also sets some objectives for the preparation of educators of these groups, which should be specified through guidelines provided by the ministry. According to the decree, the education of educators of ethnic minorities should i) generate and instil the different skills that enable educators to strengthen the global life projects of the ethnic communities; ii) identify, design and undertake research on tools for the respect and development of the identity of ethnic communities; iii) identify and develop adequate pedagogical forms through educational practice; iv) strengthen the knowledge and use of vernacular languages; and v) establish criteria and instruments for the construction and evaluation of educational projects.

Educators in communities with their own linguistic tradition need to be bilingual. Tertiary institutions and higher teaching schools with a mission to teach members of ethnic communities should offer specific training in ethnic education according to accreditation criteria defined by the Higher Education Council (Consejo Nacional de Educación Superior, CESU) and the ministry, while territorial teacher education committees (Comités Territoriales de Formación de Docentes, CTFD) should organise specific training for educators of ethnic minorities to update their skills and engage in research. In practice, however, these orientations have typically not been put into practice as reported by the ministry. This may change with the creation of ethnic minorities’ own intercultural education systems.10 Chapter 3 provides an in‑depth analysis of ethnic education.

Progressing and developing in the profession

Compensation and promotion

Under the old teacher statute (2277), the salary scale is composed of a single scale of 14 grades (see Annex 4.A). Qualifications and service time are the main factors defining the salaries and career progression. For instance, a teacher with a professional degree needs at least 21 years of experience to achieve the highest grade. Participation in professional development facilitates quicker progression in the salary scale, and is required for advancing to some salary grades. For educators of ethnic minorities, qualifications alone define the salary on a scale of four grades.

The salary scale for teachers under the new statute (1278) is composed of 3 grades (1-3) and 4 steps within each grade (A, B, C, D). The salary of these teachers is also defined by their qualifications but the level of seniority is of secondary importance – teachers can only apply for promotion in grade (ascenso) or step (reubicación) if they have held a permanent position for at least three years after completion of the probationary period, and, in the case of a promotion, two years after their progression in the salary scale.

To obtain a promotion, teachers under the new statute need to have their competencies assessed through an evaluation of competencies (Evaluación de competencias). The possibility of promotion depends on the Secretary of Education’s decision to open a call for voluntary applications of teachers. All promotions depend on the availability of sufficient budgetary resources provided through the central government. As stipulated in the statute and the single regulatory decree for education (Decree 1075 of 2015),11 the number of possible promotions is determined ahead of the evaluations and factored into the evaluation process. Evaluations should be organised on an annual basis and are carried out by the educational evaluation institute ICFES on a national level.

The evaluation was initially based on a written test. Following a strike and negotiations with the largest teacher union in 2015, the competency evaluation has been subject to changes and revisions. Initially, a different evaluation process was organised in 2015 to provide teachers who had not passed the evaluation in 2010 to 2014 with a second chance – on average, only 20% of teachers applying for promotion succeeded in previous years according to data provided by the ministry. This new form of evaluation – the Diagnostic and Formative Evaluation (Evaluación de Carácter Diagnóstico Formativo, ECDF) – was subsequently adopted as a process for the evaluation of teachers’ competencies for promotion. It was carried out a second time in 2016-17 (see Box 4.1).

Box 4.1. The Diagnostic and Formative Evaluation (Evaluación de Carácter Diagnóstico Formativo)

The competency assessment required for promotion focuses on teachers’ pedagogical and classroom management skills. It is largely based on the evaluation of a classroom video as well as a survey of the school community, a self-evaluation and the results of the two previous performance evaluations carried out by the school leader. The video is reviewed by a regional and a national peer evaluator and accounts for 80% of the evaluation result. The other instruments are weighted to different degrees for teachers from the transition year (a compulsory year of pre‑school) to Year 5 (that is primary education) and teachers from Years 6 to 11 (that is secondary education). The school community survey only applies to teachers in secondary education. Teachers need to achieve more than 80% overall to be promoted to the next grade or step.

Teachers not succeeding in the evaluation can take a recommended professional development course in a faculty of education within an accredited university to still be promoted on passing this course. While this option was available to all teachers taking part in the evaluation organised in 2015 who had not succeeded in their evaluation in the previous years, the number of places in such courses has been capped since. The number of places for professional development in the case of teachers who participated in the second round of the evaluation is equivalent to 12% of all teachers applying for promotion. Places are open to those teachers closest to the threshold of passing the evaluation. Central and territorial education authorities cover at least 70% of the cost of training.

Source: ICFES (2016), Informe Nacional 2016: Evaluación de Carácter Diagnóstico Formativa (ECDF) [National Report 2016: Diagnostic Formative Evaluation], Instituto Colombiano para la Evaluación de la Educación [Colombian Institute for Educational Evaluation], Bogotá, DC.

Salaries increase with higher qualifications for all teachers, and teachers can also progress to a higher salary grade through the completion of additional qualifications. A teacher with a first teaching qualification from a higher teaching school (ENS), for example, can move up through completion of a university degree in both the old and the new salary scale. However, salaries for higher qualifications increase especially under the new statute, which includes specific salary steps for postgraduate qualifications within the second salary grade and a separate grade for master’s or PhD degrees. Promotion for teachers under the new statute, however, always requires passing the competency assessment (ECDF). Teachers can also develop their career by taking on a school leadership position, which brings salary bonuses depending on the leadership role and size of the school (see Chapter 3).

In addition to the base salary, some teachers can receive additional benefits. For instance, teachers with low salaries are eligible for transport and food allowances. Teachers in remote areas can be compensated with higher salaries, additional time to participate in professional development activities and free plane tickets.

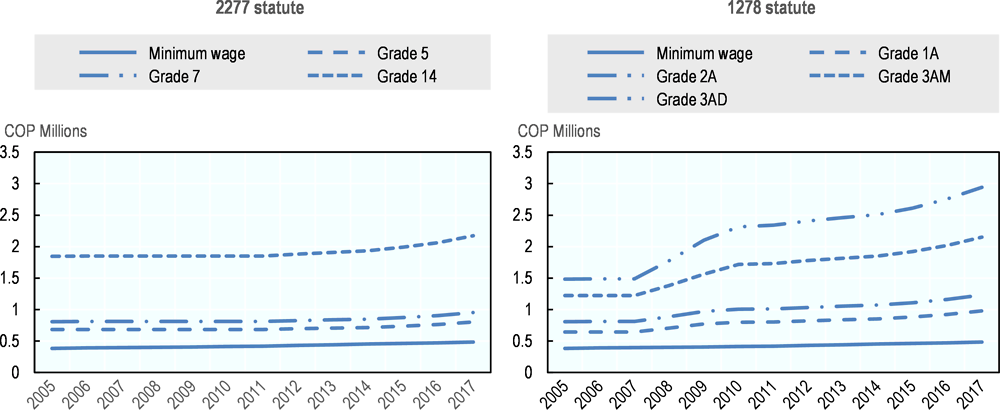

The salaries of Colombian teachers compare favourably to the labour market overall, as Gaviria and Umaña (2002[8]) already found for teachers in public education in the late 1990s and Hernani-Limarino (2005[9]) for the year 2000. Taking levels of education, experience and place of residence into account, teachers with permanent employment in a public school earn, on average, 10% more than other workers in formal employment (García et al., 2014[10]). Teacher salaries are considerably higher than the minimum wage which is set at a very high level and reached 96% of the median wage in 2013 (OECD, 2016[11]). For instance, teachers employed under the new statute with no experience and minimum qualifications earn 2.5 times the minimum wage (see Figure 4.1).

As Saavedra et al. (2017[12]) find, public teachers in Colombia earn a substantial labour market premium early on in their careers, which is however partly explained by teachers holding additional jobs in the formal sector. Of course, the choice of the comparison group influences relative wages (Morduchowicz, 2009[13]). When comparing Colombian teachers to other professionals with a university qualification, they earned on average 7% less in 2011 (García et al., 2014[10]), an earnings gap which exists in most education systems (OECD, 2017[14]).

Salaries are defined by decree each year and increase at the same rate as for other public servants. In the coming years, teachers’ salaries will likely increase given the strong bargaining power of the largest teacher union and pay increases agreed upon in negotiations with the ministry following a teacher strike in 2017 (Sánchez, 2018[1]).

Teacher evaluation

While the General Education Law suggests the evaluation of teachers as a process to ensure a high-quality standard of teaching, teachers recruited under the old statute (2277) are not evaluated on a mandatory basis. Teachers that form part of the new statute (1278) are evaluated regularly by their school leaders. School leaders belonging to the new statute themselves are evaluated by their Secretary of Education as analysed in Chapter 3.

In this mandatory annual performance evaluation (Evaluación anual de desempeño de docentes y directivos docentes) school leaders evaluate whether teachers have fulfilled their functions and responsibilities on the basis of national specifications (Decree 3782 of 2007) and guidelines (Guía No. 31: Guía Metodológico Evaluación Anual de Desempeño Laboral). The evaluation guidelines were being revised at the time of drafting this report.

Based on these guidelines and specifications, the evaluation should assess teachers’ performance in eight functional competencies across three domains (academic, administrative and community responsibilities) and seven behavioural competencies. While teachers are evaluated in all functional competencies, they select the three most relevant behavioural competencies that need to be further developed. Functional competencies account for 70% of the evaluation result, behavioural competencies for the remaining 30%. As part of their evaluation, teachers should gather evidence in the form of a portfolio. Evidence can, for example, include student and parent questionnaires, diaries, self-evaluations and protocols of classroom observations.

Figure 4.1. Trend in statutory teacher salaries for selected salary grades and steps, 2005-17

Notes: Salaries adjusted for inflation. Data on teacher salaries include bonuses for the years 2014 (applied as of 1 June), 2015 (1%), 2016 (2%) and 2017 (2%). In Statute 2277, Grade 5 refers to entry with a “normalist” teaching qualification, Grade 7 to entry with a professional tertiary degree in education, and Grade 14 to the highest salary grade. In Statute 1278, Grade 1, step A, refers to entry with a “normalist” teaching qualification; Grade 2, step A, to entry with a professional tertiary degree in education or a tertiary degree in another discipline; Grade 3, step AM to entry with a master’s; and Grade 3, step AD to entry with a PhD degree.

Source: Authors’ elaboration, data provided by the Ministry of National Education (MEN).

At the end of the school year, the school leader and the individual teacher meet for a performance evaluation meeting and teachers are rated in 1 of 3 levels of performance depending on a quantitative score: outstanding performance for a score between 90 and 100; satisfactory performance for a score between 60 and 89; and unsatisfactory performance for a score between 1 and 59.

On the basis of the evaluation, the school leader and teacher should design actions and improvement strategies in the form of a personal and professional development plan (Plan de Desarrollo Personal y Profesional). The evaluation also has high stakes for teachers. In the case of an unsatisfactory rating for two consecutive years, a teacher can be dismissed from service. The average of the two last evaluations is taken into account in the competency assessment for promotion described above (MEN, 2008[15]).

Professional development

The ministry is responsible for formulating policies, plans and programmes for teachers’ professional development on the basis of National Development Plans. The Secretaries of Education are responsible for contextualising national policies. They develop a Territorial Training Plan for Teachers and School Leaders (Plan Territorial de Formación para Docentes y Directivos docentes, PTFD) that forms part of the territorial entity’s sectoral development plan for education (Plan sectorial de desarrollo educativo). Central guidelines provide a framework for the development of these plans (MEN, 2011[16]) and the ministry provides technical assistance if requested by Secretaries of Education.

All Secretaries of Education establish a territorial teacher education committee (Comité Territorial de Formación de Docentes, CTFD)12 which provides them with support in the development, monitoring and evaluation of their territorial education plan and specific programmes and actions for teacher education. In this function, the teacher education committees should, among others, help identify the development needs of schools and their staff, define criteria and regulations for the offer of professional development and support and manage the selection, approval and evaluation of education programmes.

Workload and use of teachers’ time

The working time for teachers under the old and new statutes (2277 and 1278) is conceived on the basis of a workload system, i.e. regulations stipulate the total number of working hours and define the range of tasks teachers are expected to perform beyond teaching itself. Teachers work 40 hours per week, spending at least 6 of their 8‑hour working day at school following the schedule set by their school principal. When school principals assign more than 30 hours a week at school, teachers receive compensation for overtime up to a maximum of 10 hours a week. Guidance counsellors (orientadores) and co‑ordinators (coordinadores), that is middle leaders, are required to spend eight hours per day within the school (as are school principals).13 The working year comprises 40 weeks of academic work with students, 5 weeks of institutional development and 7 weeks of vacations.

Teachers have an academic assignment that defines their contact time with students: 20 hours a week for pre-school and 25 hours a week for primary education, which is equal to students’ classroom time at the respective levels. Teachers in secondary education have an assignment of 22 teaching hours a week, less than the 30 hours of students’ classroom time. The remaining working hours need to be spent on complementary curriculum activities (Sánchez, 2018[1]).14 On a weekly basis, teachers’ academic assignment leaves about 15 hours for non-teaching tasks in primary and 18 hours in secondary education, that is between 37.5% and 45% of time in the week.

From a comparative perspective, teachers’ total statutory working time over the school year is around the average across OECD countries with available data for the OECD publication Education at a Glance (Colombia: 1 600 hours, OECD average: 1 634 hours, in lower secondary education). It is also lower than in various other countries, including Chile and Switzerland, the countries with the highest number of working hours (OECD, 2017[14]). Taking teachers’ participation in five weeks of institutional development per year into account, total annual statutory working time, however, increases to 1 800 hours per year. Data from the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2015 suggest that teachers in Colombia are more likely to work full-time than in other countries, making Colombia an exception in the region (see Table 4.4) (OECD, 2016[17]).

Compared to other countries, teachers in Colombia have a relatively large teaching load. Primary teachers, for instance, are required to teach at least 1 000 hours annually, only behind Chile, Costa Rica and Switzerland among countries with available data. They also teach 40 weeks per year, above most OECD countries except Australia, Germany, Japan and Mexico, as well as Brazil and Costa Rica in the region (OECD, 2017[14]).

As in most education systems, teachers’ overall working time is more favourable than for the average employee in Colombia. Based on household survey data for 2011 (Gran Encuesta Integrada de Hogares, GEIH), teachers work on average about 35 hours a week, compared to a worker in formal employment who works about 50 hours a week. Teachers’ working time is also more favourable than the working time for other professionals with a difference of about 12 hours a week (García et al., 2014[10]).

Table 4.4. Share (%) of teachers working part-time, PISA 2015

Based on school principals’ reports

|

Uruguay |

84 |

|

Mexico |

51 |

|

Brazil |

49 |

|

Costa Rica |

37 |

|

Peru |

23 |

|

Chile |

21 |

|

Colombia |

4 |

|

OECD average |

21 |

Source: OECD (2016), PISA 2015 Results (Volume II): Policies and Practices for Successful Schools, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en, Table II.6.9.

Strengths

Colombia has taken considerable steps towards the professionalisation of teaching

There is a solid evidence base indicating that teachers matter – likely more than anything else in children’s lives outside their families – in improving opportunities for students. Teachers’ effects on academic achievement are substantial (Hattie, 2009[18]), and recent research suggests that teachers’ impact on social and behavioural outcomes is often comparable or even larger than effects on academic achievement (Jackson, 2012[19]; Jennings and DiPrete, 2010[20]). Studies from Colombia equally suggest that the quality of teachers contributes to student learning outcomes (Bonilla and Galvis, 2012[21]; Brutti and Sanchez, 2017[22]; García et al., 2014[10]).

Recognising this profound impact and supporting a strong teaching profession is therefore essential but policies must be implemented in ways that are sensitive to specific contexts. As recent OECD reports on teachers highlight, there is no single way for countries to promote teacher professionalism – rather there are different approaches and models that make sense in different contexts (OECD, 2016[23]; OECD, 2018[24]).

Colombia has taken significant steps to create a professional teaching workforce with the reform of the teacher statute in 2002. As analysed in depth in the following, the new statute and subsequent regulations have introduced a fair and transparent teacher selection process, raised entrance requirements, made the salary structure more attractive, made entry into subject teaching more open and flexible and introduced teacher evaluations. As judged by a comparative report on teachers in Latin America, Colombia’s reform “remains one of the most comprehensive and ambitious efforts in the region to improve teachers quality through higher standards, performance evaluation and professional development”, even though “the impressive design has been undercut by ineffective implementation” as the report also notes (Bruns and Luque, 2015[25]). A similar picture emerges in a report by the Commission for Quality Education for All (2016[26]).

While more time and research are needed to fully evaluate the effects of the reform, first evaluations indicate that teachers in the same age group under the new statute hold higher levels of education than their peers in the old statute (Ome, 2013[27]). A higher share of new statute teachers in a school is also related to positive student learning outcomes as measured by national standardised assessments (Pruebas Saber) and reduced school dropout rates (Brutti and Sanchez, 2017[22]; Ome, 2013[27]).15

Transparent and fair recruitment process ensuring a minimum standard for beginning teachers in permanent staff positions

The new teacher statute (1278) introduced a competitive, fair and transparent recruitment process for all candidates wishing to be hired for a permanent teaching (and school leadership) position in a public school. This process constitutes an important step towards the professionalisation of teaching. As Finan, Olken and Pande (2015[28]) highlight for the public administration in general, the selection and screening for the recruitment of public officials have important implications for the quality of service delivery, the quality of the hired candidates and the type of applicant.

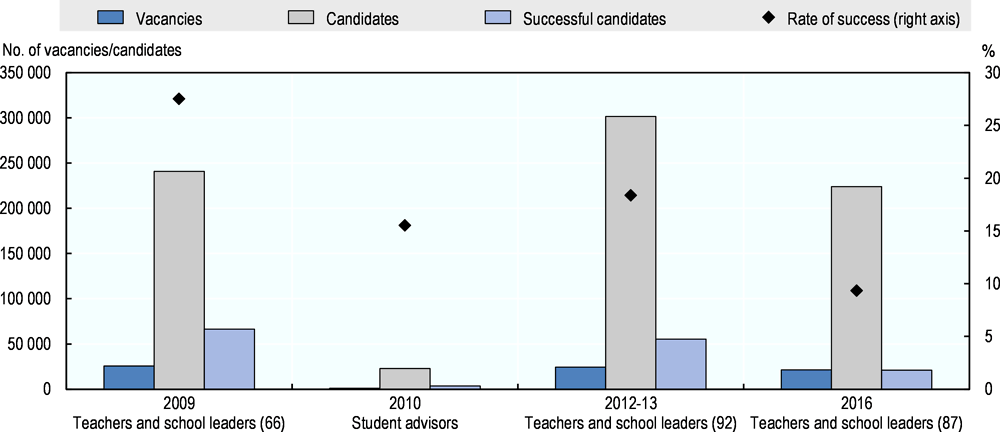

Since 2006, the recruitment process has been administered centrally by the National Civil Service Commission in collaboration with the ministry of education and ICFES, the institute responsible for educational evaluation. The process is based on a score system and entails a written knowledge and competency examination, a psychometric test, a check of credentials and an interview. The process is highly competitive and selective – approximately 9% of applicants passed the process in 2016 (Figure 4.2). Involvement of the National Civil Service Commission, an independent and autonomous public body at the highest level of the Colombian state with the mission of safeguarding the principle of merit and equality in the civil service, is a strong guarantee for a fair recruitment process. It leaves little room for patronage and creates trust in the recruitment process, although there are challenges in the implementation of the process as analysed below (OECD, 2013[7]).

Figure 4.2. Participation in national teacher recruitment process

Note: In parentheses the number of certified territorial entities that offered vacancies in that merit contest.

Source: Authors’ elaboration from data in Sánchez, J. (2018), OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools: Country Background Report for Colombia, http://www.oecd.org/education/schoolresourcesreview.htm.

The centrally organised recruitment process is a significant improvement compared to the previous recruitment of teachers (and school leaders) by Secretaries of Education which was often subject to political influence and clientelism (Duarte, 2003[29]). The possibility of a teacher test to identify better teachers is most likely limited (Cruz-Aguayo, Ibarrarán and Schady, 2017[30]), but a standardised process is still an improvement over discretionary recruitment decisions (Estrada, 2017[31]).

Research suggests that it is difficult to identify effective teachers at the point of hiring and that recruitment should, therefore, be based on a broad set of information and entail an opportunity for both new teachers and their employer to assess whether teaching is the right career for them (OECD, 2005[32]; Staiger and Rockoff, 2010[33]). The requirement for the completion of a demanding probationary period thus constitutes another positive element of teacher recruitment. Between 2010 and 2013, approximately 1 in 6 teachers failed their probation (Sánchez, 2018[1]), even though this has been changing in recent years. Between 2014 and 2016, almost all new teachers passed their probationary period (MEN, 2018[34]). This suggests that stronger pedagogical leadership is required to ensure the continuous implementation of a rigorous evaluation process at the end of probation. Mandatory regular evaluations for newly hired teachers provide a further opportunity for addressing performance concerns and for providing formative feedback (OECD, 2013[35]), although there are also concerns about the quality of this process as described below.

Higher entrance requirements and a more attractive salary structure with the potential to raise the status of the profession

The new teacher statute also raised qualifications requirements and introduced a more competitive salary structure. Both of these steps have the potential to make the profession more attractive and to raise its status (Ome, 2013[27]). Under the old statute (2227), it was possible to go into teaching on completion of upper secondary education. Under the new statute (1278), a degree from a higher teaching school (ENS) is the minimum qualification required. Initial teacher education in Colombia is, furthermore, relatively fluid and teachers from these programmes often continue their education at higher level.

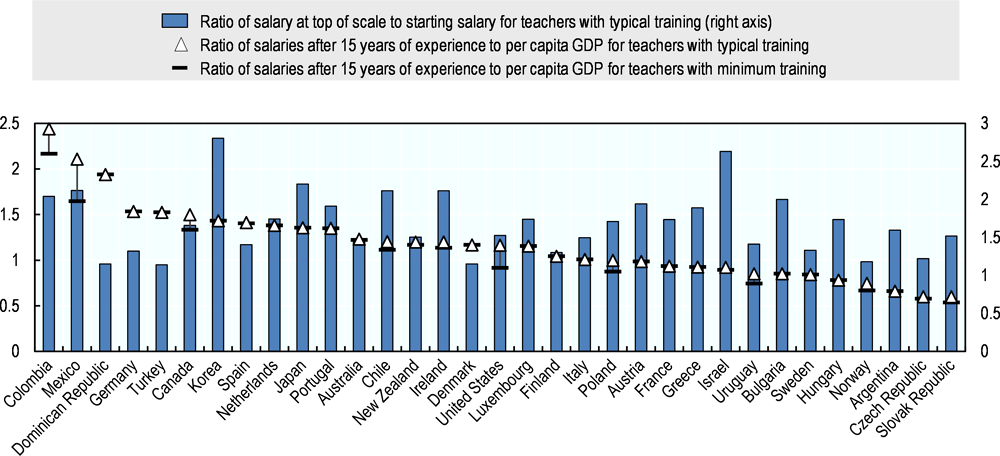

Compared to the salary structure under the old statute, the salary structure for the new statute provides the possibility for teachers from higher teaching schools to reach salary levels twice as high as before. Teachers with university degrees can reach the highest salary step more quickly (Brutti and Sanchez, 2017[22]). The new salary structure is also attractive when set in an international context. As data from the OECD publication Education at a Glance show, the salary structure for teachers recruited under the new statute has the second steepest salary scale among countries with available data: teachers at the top of the salary scale with the highest qualifications earn more than three times as much as teachers with initial starting salaries and minimum qualifications. Teachers with minimum qualifications at the top of the salary scale still earn twice as much as teachers with initial starting salaries, more than the OECD average for all levels of school education. Theoretically, teachers can reach the top of the scale within 9 years compared to 25 years on average across OECD countries (OECD, 2017[14]).

While statutory salaries for a lower secondary teacher at the bottom of the salary scale are considerably lower than on average across the OECD (55%), earnings at the top of the salary scale with maximum qualifications are only 14% lower (authors’ calculations based on OECD (2017[14])). Relative to countries’ national income, statutory teacher salaries are the highest among the 47 education systems with available data that participated in the OECD PISA 2015 (see Figure 4.3) (OECD, 2016[17]).16

Figure 4.3. Teachers' salaries, 2014

Source: OECD (2016), PISA 2015 Results (Volume II): Policies and Practices for Successful Schools, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267510-en, Table II.6.54.

Also compared to other professionals with tertiary degrees, the new salary structure appears attractive (Ome, 2013[27]) and builds on otherwise favourable salaries compared to the Colombian labour market overall as well as significant increases in statutory salaries over time as analysed above (see Figure 4.1). Relative earnings for teachers compare very well internationally as well. Statutory salaries for teachers with 15 years of experience and typical qualifications are about 1.5 times as high as salaries for similarly educated workers at all levels of education. On average across OECD countries, lower secondary teachers can expect to earn 9% less than workers with tertiary education (OECD, 2017[14]).17

However, while the salary scale for teachers of the new statute is, in theory, relatively favourable compared to teachers of the old statute and similarly qualified workers, and considering national income, teachers’ actual progression in the salary scale has been relatively hard to obtain in practice and passing the required evaluation has been difficult.

Equal regulations and status for teachers of different levels of school education and pre-school education

Both the old and new teacher statutes place teachers of different levels of school education, as well as pre-school and school teachers, under the same regulations. This not only makes for some flexibility in allocating teachers to different levels of education in response to demographic developments (OECD, 2005[32]), it also avoids too rigid links between the structure of school systems and teacher education and employment (Ávalos, 2008[5]). It also puts teachers of different levels on an equal footing, including teachers in pre-primary and primary education, even though there are concerns about the lower status of staff in early childhood education and care managed by the Colombian Institute of Family Welfare (Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familial, ICBF) (OECD, 2016[4]).18

An equal professional status for teachers teaching different levels of education through the same qualification requirements and salary levels can play an important role in attracting and retaining high-quality staff. It can thus support quality provision in earlier stages of the education system which can lay a strong foundation for later learning and has been shown to have particular benefits for disadvantaged students. It can facilitate co‑operation between staff of different sectors and thus help ease children’s transition, for example from pre‑primary to primary education (OECD, 2017[36]). In the long run, it has the potential of creating a strong sense of professional community among all teachers.

An alternative entry route into teaching bringing flexibility and possibly new talent into the profession

The new teacher statute (1278) has created the possibility for side entry into the profession. Individuals with degrees from other disciplines can apply for subject teacher positions in secondary education provided they complete a programme in pedagogy at a tertiary institution. In addition, individuals with a background other than education have the possibility of entering teaching after completing a relevant post-graduate qualification. According to reports by the National Civil Service Commission, 33% of applicants for a permanent position in the 2016 merit contest applied with a degree other than an undergraduate qualification in education, but side entrants made up 47% of successful applicants (data provided by the ministry). In 2017, around 10% of teachers employed under the new statute (1278) held a professional degree in discipline other than education as their last qualification (authors’ calculations based on Sánchez (2018[1])).19

Such alternative routes into teaching provide additional flexibility in responding to increasing student numbers or to a teacher shortage in specific subjects. They arguably broaden the range of backgrounds and experiences in schools and provide access to teaching for individuals at different stages of their lives (OECD, 2005[32]). At the same time, alternative pathways raise questions as to whether teachers recruited via such pathways are as effective as conventionally prepared teachers and whether teachers from alternative pathways then remain in teaching (Little and Bartlett, 2010[37]).

Conclusions about the effects of different pathways into teaching are difficult to draw, also given the variety of alternative pathways. Studies from the United States suggest that teachers from both traditional teacher education and alternative pathways can be effective in the classroom, but that some teachers from both programmes may not have the competencies and preparation to fulfil their role effectively (Henry et al., 2014[38]; Redding and Smith, 2016[39]). Substantial research for Colombia is not yet available, but some have raised concerns about the level of preparation for classroom practice, pedagogy and didactics of teachers completing pedagogy programmes in parallel to their job in schools. Caution has also been raised about the risk of side entrants leaving the teaching profession more than traditional teachers (Durán Sandoval, Acosta Zambrano and Espinel Montaña, 2014[40]; Jurado Valencia, 2016[41]).

Towards a culture of teacher evaluation in schools

The new teacher statute (1278) has introduced a comprehensive and systematic approach to teacher evaluation that has the potential of supporting the continuous learning of teachers. In addition to evaluation for entry into the profession, the new statute requires regular performance evaluations within schools and on a voluntary basis for promotion.

Evaluación Anual de Desempeño Laboral: If well designed and implemented, school internal evaluations can be a key lever to put the focus on the quality of teaching and learning in schools (OECD, 2013[35]). While there is still substantial room to improve teacher evaluation and make the best use of the process, regular evaluations have the potential to establish a strong culture of professional feedback, learning and improvement in Colombian schools – an important development in a context where teachers enjoy a large degree of pedagogical autonomy as discussed below.

In the schools visited by the review team, there was evidence of an emerging culture of teacher evaluation. While in some schools the principal took responsibility for engaging in performance discussions and establishing development plans on the basis of the evaluation, in other schools this depended on the school site that the teacher was working in – in Colombia, public schools are organised in clusters of multiple sites. In these cases, the school principal and middle leadership, such as the responsible co-ordinators, took responsibility for evaluating their respective teachers. Various teachers and school leaders to whom the review team spoke made reference to the central guidelines for teacher evaluation. In some schools, evaluations of teachers under the new statute had in fact resulted in evaluations for all teachers, including those under the old statute.

Evaluación de Carácter Diagnóstico Formativa: Effective teacher evaluations can also be a tool to recognise and reward high-quality teaching and to manage teachers’ career advancement (OECD, 2013[35]). Colombia has a second evaluation process in place for this purpose with the external assessment of teachers’ competencies for promotion. While there are some challenges for implementation as for school internal evaluations, this process provides a basis for acknowledging good teaching and creates an indirect link between teachers’ performance and compensation. Such an indirect link is preferable to direct links through student assessment results which have produced mixed results and can have perverse effects, such as a narrowing of the curriculum (OECD, 2013[35]).

More time is needed to fully evaluate the changes introduced to the design of this evaluation process in 2015, particularly since negotiations about the process between the largest teacher union and the ministry were ongoing at the time of writing. Compared to the old process, the new evaluation process, however, entails two positive features.

Whereas the original evaluation was based on a written assessment, the new process entails peer evaluations (one national, one regional) realised through the use of a classroom video. While teachers interviewed during the review visit raised concerns about the reliability of the use of this tool and the weight given to it, the classroom video as one evaluation instrument puts the focus on classroom practice. The involvement of peer evaluators who can apply and are trained for this role is also a promising approach to build capacity (OECD, 2013[35]). The use of video technology is an innovative approach, also considering the limited amount of resources required for the use of this technology.

In addition, the new process provides an opportunity to identify strengths and weaknesses and to feed into teacher learning, in particular for those teachers who have a second chance at promotion following completion of a related professional development course.

The ministry has supported teacher development with multidimensional and targeted initiatives that have the potential to create a culture of peer learning in schools and have had a considerable impact in rural schools

While the organisation and management of professional development is largely the responsibility of the Secretaries of Education, the ministry of education has developed and implemented national initiatives to strengthen the quality of education through its budget for investment projects, notably the Let’s All Learn programme (Programa Todos a Aprender, PTA) and the Rural Education Programme (Programa de Educación Rural, PER) but also other initiatives like Classrooms Without Borders (Aulas sin fronteras) or Pioneers (Pioneros) (for more information about the latter two, see Sánchez (2018[1])). The government’s National Development Plan for 2014-18 explicitly recognised the importance of high-quality teaching and the need to foster teaching excellence as one element of the plan’s strategy for education (DNP, 2015[42]).

Considering the difficulty to reform initial teacher education, in general as well as in Colombia, and the concerns about the different levels of capacity and resources for Secretaries of Education to develop, implement and monitor professional development, these central initiatives meet an important need in the system. Central initiatives seem to have been well received by regional and local authorities, schools and individual teachers as was also evident during the review team’s interviews with different stakeholders. They have been well-targeted, improved teaching and learning in schools and contributed to closing achievement gaps between rural and urban areas. Evaluations have facilitated adjustments to the design and implementation of the initiatives and learning about successful practices (Sánchez, 2018[1]).20

The Let’s All Learn programme

The Let’s All Learn programme follows a multidimensional approach to improve student learning in the core subjects language and mathematics with a cascade teacher education model at the heart of the programme (see Box 4.2).

Tutors provide situated professional development to teachers within participating schools, working both with individual teachers and with groups of teachers. The programme thus puts the focus on classroom practice within particular contexts and has the potential to improve teachers’ competencies. For one, it has the potential to develop the competencies of teachers taking part as tutors. While there is a trade-off in as far as the programme takes effective teachers out of their classrooms to coach others, tutors may develop additional competencies and experiences they can bring back to their own school afterwards. Tutors, furthermore, undergo training for their role and learn through their mentoring activity. More importantly, accompanied teachers develop their skills through both individual feedback from their tutor and through peer learning within study groups.

In doing so, the Let’s All Learn programme pursues a multidimensional approach that combines professional development with other elements such as curricular materials and student assessment tools. Such approaches to teacher learning that are built around the interaction between and among teachers, students and content have been shown to enable teachers to envision what new practices might look like and how to transfer these ideas into their classroom (Gallagher, Arshan and Woodworth, 2017[43]).

Multidimensional takes on teacher learning also seem relevant in the Colombian context where schools and teachers have a large degree of pedagogical autonomy, e.g. to choose educational materials. Since the programme works around the activities of tutors within individual schools, it facilitates adaptation the implementation of the programme to the constraints of specific local contexts and schools’ and teachers’ needs to foster student learning and development (see Díaz (2016[44]) for a case study).

The Let’s All Learn programme also has the potential to contribute to changing the culture of schools. While the success of coaching depends on trusting school cultures and teachers’ willingness to open themselves to criticism (Kraft, Blazar and Hogan, 2018[45]), the work of tutors within classrooms and groups of teachers itself can create greater openness of classrooms and foster mutual learning among teachers around their students’ learning needs. Reportedly, teachers in many Colombian schools have shown openness to receiving their tutor within their classrooms (Sánchez, 2018[1]).

Box 4.2. Let’s All Learn (Programa Todos a Aprender)

Let’s All Learn is a large-scale programme initiated by the ministry in 2011 and implemented since 2012 as part of the government’s National Development Plans for 2010-14 and 2014‑18. The PTA has been funded through the ministry’s budget for investment programmes and received almost half of the budget of the ministry’s quality directorate for school and pre‑school education in 2017, about COP 130 billion.21 The programme targets primary education (Years 0 to 5) and follows a multidimensional approach to improve student learning in language and mathematics. This includes pedagogical components related to the curriculum and educational materials, situated professional development, school management and community involvement.

The programme’s main objective is to build teachers’ skills and competencies and to improve their practices in the classroom through a cascade teacher education model. Tutors are selected from across the country and prepared for and supported in their role by trainers holding a master’s or PhD degree. Tutors then provide situated professional development to teachers within participating schools. They work directly as peers with individual teachers in the classroom, observe teachers’ practices and provide feedback on pedagogical and didactic strategies. They work with groups of teachers and organise peer learning activities and discussions around pedagogical topics within schools. In addition, tutors are expected to support other activities and pedagogical processes and provide support for the development and implementation of student assessments, the use of curricular guidelines, the selection and use of materials and textbooks, and the development of the Día E, a day in the school calendar to discuss school development within the school, for example.

By 2017, the programme had employed 97 trainers and trained 4 100 tutors. Tutors had worked with 109 357 teachers in 13 455 sites of 4 476 public schools in 885 municipalities in all of the 32 departments. Between 2012 and 2017, the participation of public schools in the programme grew by 88% and the number of participating teachers more than doubled. The programme prioritises schools with low achievements as measured by the standardised student assessments for Years 3 and 5 (Pruebas Saber 3 and 5). Schools achieving their improvement objective in standardised assessments and high results in their Synthetic Education Quality Index (Índice Sintético de Calidad Educativa, ISCE), a school performance measure explained below and in Chapter 3, end their participation in the programme, thus making resources available for support to other schools.

While the programme was not designed as a strategy targeting rural schools in particular, it has had a particular impact on schools in rural and remote areas in departments like Amazonas, Chocó, Guainía, Guaviare, La Guajira, Vaupés and Vichada. Sixty-five percent of participating schools were classified as rural, compared to 30% which were classified as urban schools.

Sources: Sánchez, J. (2018), OECD Review of Policies to Improve the Effectiveness of Resource Use in Schools: Country Background Report for Colombia, http://www.oecd.org/education/schoolresourcesreview.htm; OECD (2016), Education in Colombia, Reviews of National Policies for Education, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264250604-en.

Rural Education Programme

The Let’s All Learn programme builds on the successful experience of the Programme of Rural Education (Programa de Educación Rural, PER) implemented between 2002 and 2015 (also see Chapter 1 for a full description of the programme). Like the Let’s All Learn programme, the Rural Education Programme pursued a multidimensional approach that included the use of flexible pedagogical models and teaching materials designed for rural schools, teacher education and development, and capacity building of participating Secretaries of Education.

Between 2013 and 2015, the programme complemented the Let’s All Learn programme with the implementation of school-based professional development (Desarrollo Profesional Situado). Teams of experts provided support, technical-pedagogical advice and didactic materials and guides to rural school sites to support teacher learning in those schools. It included on-site visits and workshops, virtual coaching and the creation of study groups (círculos de estudio) (Colombia Aprende, 2018[46]).

Teachers are relatively satisfied and have a considerable degree of autonomy and voice in schools and in the development of their profession

The Colombian school system can build on relatively high levels of overall satisfaction among teachers, a large degree of pedagogical and curricular autonomy for teachers and schools, possibilities for teacher involvement in school decision-making, as well as a say for teachers in the development of their profession and education overall – aspects which can be considered essential aspects of a professional teaching body (OECD, 2016[23]).

Teachers’ satisfaction with their profession and their schools

Colombian teachers are generally satisfied with both their profession and their school which can help teachers contribute to a positive school climate and to support their students’ learning. As research suggests, teachers’ satisfaction is associated with lower absenteeism, stress, and turnover and with the use of innovative instructional practices in classrooms. It is also related to teacher efficacy, that is their attitudes and beliefs about their ability to teach and make a difference through their teaching (Mostafa and Pál, 2018[47]; OECD, 2014[48]), even though one has to recognise that teachers’ job satisfaction and student learning do not always go hand in hand (Michaelowa, 2002[49]).

According to surveys, Colombian teachers are satisfied with the career choices they have made. The teacher questionnaire administered for the OECD PISA 2015 reveals that a great majority (86%) of Colombian teachers agreed that the advantages of being a teacher clearly outweigh the disadvantages, and a large majority of them reported that their goal was to become a teacher when they completed upper secondary education. Only a small proportion of Colombian teachers (7%) regretted their choice of career. Colombian teachers are, in fact, more satisfied with their profession than those in the other 17 school systems that distributed the PISA teacher questionnaire, except for the Dominican Republic. In Brazil, for instance, only 55% of teachers agreed that the advantages of being a teacher outweigh the disadvantages, and in Chile, 13% of teachers regretted their choice of career (Mostafa and Pál, 2018[47]).

Colombian teachers are also extremely satisfied with their schools. As many as 95% of teachers stated that they enjoy working at their schools, 6 percentage points above the average of the 18 educations systems that distributed the PISA teacher questionnaire (Mostafa and Pál, 2018[47]). These results are consistent with those in other international surveys, such as the UNESCO TERCE, which shows Colombian teachers being the second most satisfied with their job across the region (UNESCO, 2016[50]).

Teachers’ say in school governance and involvement in decision-making for pedagogical and curricular matters within their school

As analysed in Chapter 3, schools in Colombia have considerable freedom in making pedagogical and curricular decisions as well as established platforms for participation in school governance. Teachers have a prominent role in school decision-making through their participation in the school’s directive and academic councils (consejo directivo and consejo académico). The school calendar further promotes teachers’ participation in school development through five weeks of institutional development in the school year.

Also, the conception of teachers’ working time provides a strong basis for involving teachers in school life and decision-making. Defined on a workload system rather than by their number of required teaching hours alone, the definition of working time recognises the variety of tasks teachers fulfil in schools today (OECD, 2005[32]), such as participation in school management, but also parental engagement. Teachers are furthermore required to spend a comparatively large share of their statutory working time at school – the fourth largest after Chile, the United States and Sweden when compared to OECD countries (OECD, 2017[14]). This provides a strong basis for school leaders to manage their teachers effectively, facilitate collaborative practice, and involve teachers in school governance.

While the level of teacher involvement in practice differs between schools, schools have the means of involving teachers and for creating a shared pedagogical vision. Data from the OECD PISA 2015 provide some indications for teachers’ levels of involvement in schools: 78% of students were in a school whose principal reported that they provide staff with opportunities to participate in school decision making at least once a month, about six percentage points more than on average across OECD countries (OECD, 2016[17]). As school visits also suggest, teachers are typically very autonomous in making pedagogical decisions within their classroom, which can allow them to exercise their professional judgment to respond to the complexity of classroom teaching and learning.

However, possibilities for teacher participation have to be put into the context of weak pedagogical leadership as analysed in Chapter 3 and concerns about teachers’ learning explored below. Teachers interviewed during the review visit suggested that curricular autonomy had not yet translated into a greater sense of empowerment. Teachers often resorted to central curricular guidelines and standards, and textbooks and assessment tools provided through specific initiatives, such as the Programa Todos a Aprender.

Findings from the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2013 in fact highlight that autonomy for teachers defined as teacher involvement in school-based decision-making is not sufficient. While teacher autonomy has a small positive correlation with teachers’ satisfaction with their profession and their work environment, it can actually make teachers feel less capable in their ability to do their job. Teachers thus need adequate support to make use of and build their collective capacity to use their autonomy, get involved in school decision-making and feel empowered (OECD, 2016[23]) – which, in turn, can foster a vision of teaching as a true profession and help build teachers’ commitment to teaching and their school (Pearson and Moomaw, 2005[51]).

These findings are mirrored in recent research which similarly suggests that combining teacher leadership, that is involvement in school decisions, and teacher accountability can help improve student learning (Ingersoll, Sirinides and Dougherty, 2017[52]).

Teachers’ voice in the development of their profession and education policy

Teachers not only play an essential role in individual schools and classrooms but through unions and professional bodies, such as teacher councils, also shape the operation of school systems and the formulation and implementation of education policy.

One line of literature on teacher unions and education policy conceives of unions as contributing to policy development and implementation, as well as facilitating information flows. This view also highlights the role of unions in facilitating professional learning and promoting a positive professional identity (Bascia, 2005[53]; OECD, 2015[54]). Scholarship from Latin America highlights unions’ potential and history of playing a proactive rather than a reactive role through teacher development and policy advocacy, including for some of their countries’ most vulnerable citizens who are served by public education (Gindin and Finger, 2013[55]). A second line of literature tends to see unions as special interest groups pursuing a self-interested agenda, blocking education reform and undermining reform implementation when members’ benefits or working conditions are threatened (Bruns and Luque, 2015[25]; Moe, 2015[56]).

Even though the relationship between education authorities and teacher unions in Colombia has often been fraught with difficulty, Colombia’s largest teacher union (FECODE) has played a prominent role in the development of the profession and in improving working conditions over time. As in other countries in Latin America, the union was fundamental in establishing binding work conditions, salaries and other benefits through the introduction of a first teacher statute in 1979. This arguably improved teachers’ status and working conditions. Considering the country’s long-standing armed conflict, the union has also played an important role in denouncing violence against teachers and advocating for the transfer of threatened teachers.

The union has in addition played a positive role in education policy more broadly, for instance with the formation of a social movement initiating a reflection about the role, nature and status of teaching (Movimiento Pedagógico) in the 1980s, as an advocate for democratic participation in education policy with the formulation of a new Constitution and General Education Law in the 1990s, and as a promotor of children’s right to a free education, including three years of early childhood education and care (Correa Noriega, 2013[57]; López, 2008[58]). More recently, FECODE has informed reforms, as was the case with the introduction of changes to teacher evaluation, advocacy for strengthening participatory structures in education through the reactivation of education councils (juntas de educación) and participation in discussions of a reform of school funding.

Challenges

A sustained and shared effort to advance further in the professionalisation of teaching is needed, built on effective involvement of the profession

Colombia has taken important steps to professionalise teaching over the last two decades, as just described. As is explored in the following sub-sections, challenges remain, however, in developing a high-quality profession that supports the learning and development of all students – something that also fundamentally requires stronger school leadership (see Chapter 3). Promising changes that have already been initiated still need to be implemented successfully or sustained over time, and there is significant scope to reflect about and develop other aspects of professionalism while building on key strengths such as teachers’ involvement in schools and high levels of teacher satisfaction.

Such a renewed vision of professionalism is not only needed to further improve teaching and learning but also to further raise the status of the profession. Better working conditions, more diverse career development opportunities and collaborative ways of working could help make teaching a more attractive career choice for highly qualified candidates. The reform of the teacher statute in 2002 is an initial step towards the recognition of the teaching profession, and civil society has contributed to changing the status of the profession with interesting initiatives such as the Premio Compartir (Vaillant and Rossel, 2012[59]).22 Also the ministry of education has put in place interesting initiatives, such as Ser Pilo Paga Profe to raise the attractiveness of teaching for high-performing students finishing their secondary education.23

But professional degrees in education at the university level are among those with the lowest numbers of applicants, attracting students who are less likely to have performed well in the school leaving examinations (Prueba Saber 11) (Bonilla and Barón, 2014[60]; García et al., 2014[10]). A career in teaching represents possibilities for social mobility but does not always attract the candidates best equipped for teaching (Duarte, forthcoming[61]).

Difficult relations between the government and FECODE have made the implementation of past reforms challenging, and frequent teacher strikes have hampered the education of children and young people. The implementation of significant changes brought about by the new teacher statute, in particular, has been challenging considering limited effective stakeholder involvement at the time of putting the statute in place, something which is considered essential for the effective governance of education (Burns and Köster, 2016[62]). There is therefore significant scope to keep improving the dialogue between the government and the largest (and potentially other regionally and locally operating) unions as recommended below (López, 2008[58]).

There are various teacher competency descriptions and profiles that have not yet become a shared framework to develop the profession based on validated practice

The Colombian school system counts with a substantial degree of decentralisation and autonomy in the management of education, such as the organisation of teachers’ professional development by Secretaries of Education and schools, the development of educational projects in schools by the school community and teachers, and the design of initial teacher education programmes by faculties of education. However, despite this range of actors and their significant autonomy, there is no common and shared vision of good teaching in the form of coherent teaching standards. While some argue that teaching standards can narrow teaching practice and autonomy, standards can guide teacher development, improve the standing of teaching in the broader community and provide a framework for developing teacher identity, provided they are well-designed and used appropriately (Adoniou and Gallagher, 2017[63]; Darling-Hammond, 2017[64]).

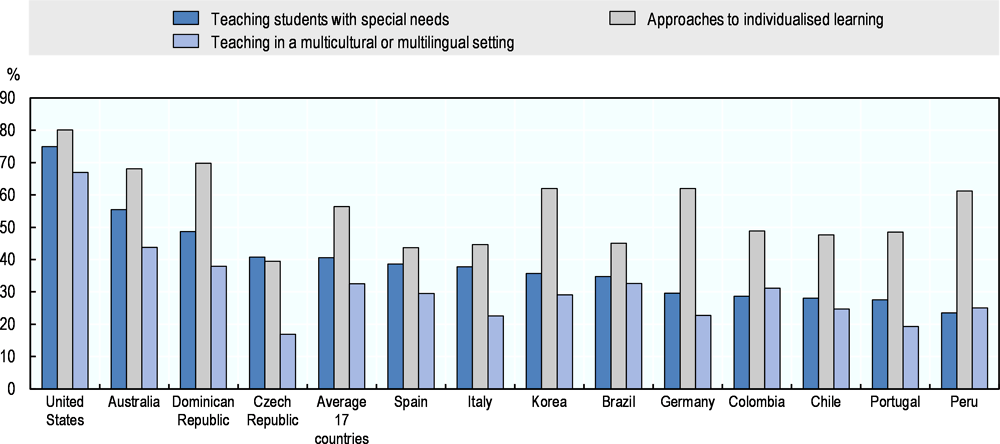

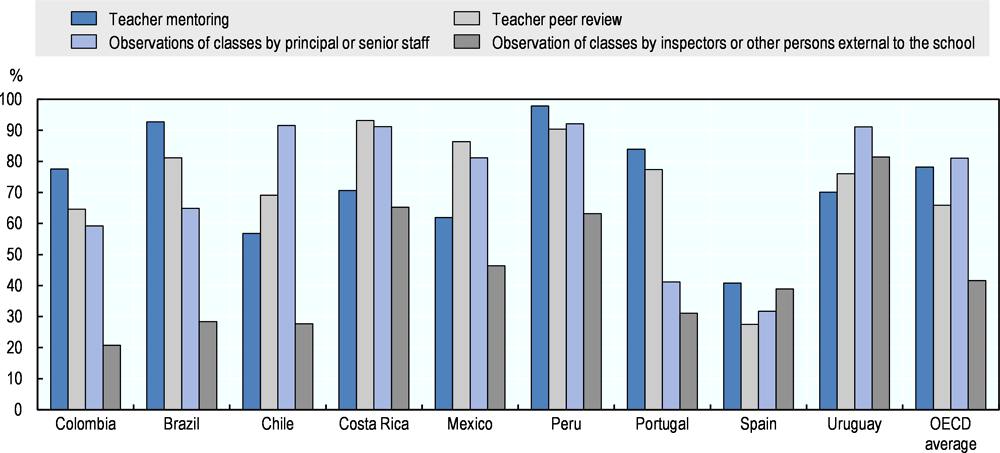

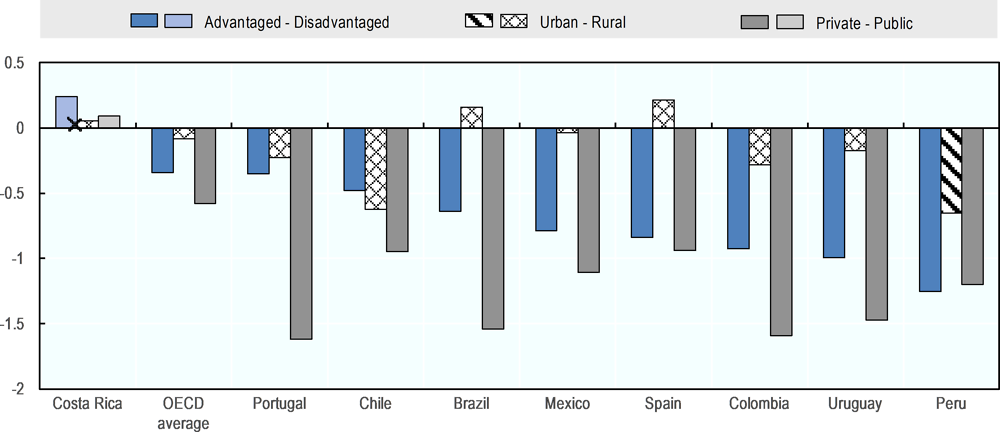

In Colombia, there are a number of laws, decrees and resolutions that describe teacher competencies (e.g. the manual of functions for teachers, quality characteristics for initial teacher education programmes, and guidelines for school internal teacher evaluations). But these descriptions of teachers’ competencies are not detailed enough and do not define the full range of competencies of excellent teachers (OECD, 2016[4]). The teacher profile developed for the competency assessment required for promotion (ECDF) most likely comes closest to a broad framework of good teaching. However, it is not yet widely recognised as a reference within the profession and has not become the basis for the development of teacher policies. As Duque et al. (2014[65]) highlight, Colombia needs to advance in teachers’ acceptance of a set of good practices to become a true profession. These standards need to be validated and adjusted over time with changing social demands and new knowledge. There are, furthermore concerns that teachers in particular contexts, such as rural teachers, lack a clear profile in Colombia (Sánchez, 2018[1]).