This chapter summarises the context, key insights and policy recommendations of the OECD Skills Strategy project in Southeast Asia. It applies the OECD Skills Strategy Framework to provide a high-level assessment of the performance of Southeast Asia’s skills system. The chapter provides an overview of: 1) responding to the skills implications of megatrends and COVID-19; 2) developing relevant skills over the life course; 3) using skills effectively in work and society; and 4) strengthening the governance of skills systems. The chapter summarises the related key findings and recommendations. Subsequent chapters provide more details on the opportunities for improvement, good practices and policy recommendations for Southeast Asia.

OECD Skills Strategy Southeast Asia

1. Key insights and recommendations for Southeast Asia

Abstract

Skills matter for Southeast Asia

Skills are vital for enabling individuals and countries to thrive in an increasingly complex, interconnected and rapidly changing world. Countries in which people develop strong skills, learn throughout their lives and use their skills fully and effectively at work and in society are more productive and innovative and enjoy higher levels of trust, better health outcomes and a higher quality of life.

As new technologies and megatrends increasingly shape our societies and economies, getting skills policies right becomes even more critical for ensuring societal well-being and promoting inclusive and sustainable growth. The coronavirus (COVID‑19) crisis has accelerated the digitalisation of learning and work and risks increasing inequalities in education and labour markets. For Southeast Asia, implementing a strategic approach to skills policies is essential to support the region’s efforts to boost economic recovery and to build a resilient and adaptable skills system. Southeast Asia must build the foundations today for a more inclusive, prosperous and healthy future through strategic investments in the skills of its people.

Skills are essential for Southeast Asia’s response to global megatrends and COVID‑19

In Southeast Asia, as in OECD countries, megatrends such as globalisation, technological progress, demographic change, migration and climate change, and most recently, COVID‑19, are transforming jobs, the way society functions and how people interact. To thrive in the world of tomorrow, people will need a stronger and more well-rounded set of skills. These include foundational skills; cognitive and meta‑cognitive skills; social and emotional skills; and professional, technical, and specialised knowledge and skills. Southeast Asia will also need to make better use of people’s skills in the labour market and in individual workplaces.

Globalisation has led to the emergence of global value chains (GVCs). GVCs allow different parts of the production process to be performed in different geographical locations, with important skills implications. Many Southeast Asian countries are now major players in the world market, both as exporters and importers, and have thus attracted significant investments in services, trade, communication and manufacturing sectors (OECD-UNIDO, 2019[1]). When Southeast Asian countries have a highly skilled workforce, this enables them to participate in the higher end of the global production chain characterised by high-skilled activities. Participation in GVCs can lead to productivity gains, but achieving those gains is dependent on Southeast Asian countries having people with the right sets of skills.

New technologies and digital infrastructure are spreading rapidly throughout Southeast Asian countries. Many Southeast Asian countries attract new technologies to accelerate industrialisation and economic development. The region is projected to be one of the world’s fastest-growing data centre markets in the next few years, exceeding the growth in North America and the rest of the Asia-Pacific (ASEAN Secretariat and UNCTAD, 2019[2]). Technological progress has been accelerated by the COVID‑19 pandemic, as fear of the spread of the virus and social distancing measures have made online interactions at work and everyday life more common (Google, Temasek and Bain & Company, 2021[3]). Individuals, firms and countries that can harness this new wave of technological progress stand to benefit greatly, but only if they have a broad mix of skills, including cognitive (e.g. problem solving), socio-emotional (e.g. communication, teamwork) and digital skills (OECD, 2019[4]).

Southeast Asian countries continue to experience unprecedented and sustained change in the age structure of their populations. Life expectancy is increasing, while fertility is decreasing, driven by improved living standards. In many Southeast Asian countries with relatively youthful populations, greater investment in the skills of youth can dramatically improve their skills profiles, increasing their productivity and competitiveness, and, by extension, help them to move up the GVC in the longer term. Currently, the share of older people over 65 in the population is, on average, lower across Southeast Asian countries (10.7%) than in OECD countries (17.3%) (OECD, 2022[5]). However, the speed of population ageing is increasing, and the share of older people over 65 years old in total population is projected to be over 27% in Southeast Asia by 2050 (UN DESA, 2019[6]). Increased life expectancy and improving health in older age imply that older workers can stay in the labour market longer, provided they have adequate incentives and opportunities to reskill and upskill. They will also need skills that will allow them to participate fully in society, such as digital skills that facilitate social engagement and access to basic public services in a digital world (OECD, 2019[7]).

Southeast Asian countries are significant sources of both migrant inflows and outflows. Brunei Darussalam, Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand are countries with net migrant inflows, while Cambodia, Indonesia, Lao People’s Democratic Republic (hereafter “Lao PDR”), Myanmar, the Philippines and Viet Nam have net migrant outflows (Migration Policy Institute, 2020[8]). Migrants increase the supply of skills and can contribute to economic growth in their host country if their skills are well used. When individuals with high skills emigrate, this can be a loss to the origin country due to increased labour shortages in important sectors. However, it can also be a gain due to remittances and useful know-how, skills, and networks for the economy, if the individuals return (OECD, 2019[7]). As Southeast Asian countries have different demographic profiles, with the size of workforces growing in some and declining in others, more circular migration in the region could be beneficial for all. In addition, managing migration better can boost workers’ welfare and accelerate economic integration.

Climate change is a priority for Southeast Asian countries. The region is vulnerable to floods, droughts, heat waves, typhoons and rising sea levels and their projected adverse impacts on gross domestic product (GDP). Climate change affects skills development, usage and skills demand in various ways. Learning and work could be interrupted by direct channels, such as the closure of schools and workplaces, damages to relevant infrastructure, and the relocation of families, as well as by indirect channels, such as the onset of various health issues due to climate-change-induced increases in precipitation and the rise of temperatures (UNICEF, 2019[9]; ADB, 2017[10]). When countries transition towards green economies and create new “green jobs”, sufficient reskilling and upskilling opportunities are crucial to creating a workforce that can support such a transition, as well as helping vulnerable workers find new job opportunities in emerging sectors (ILO, 2017[11]; Martinez-Fernandez, Hinojosa and Miranda, 2010[12]; ILO, 2019[13]).

The COVID‑19 pandemic has disrupted progress and may exacerbate systemic challenges

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly impacted all countries in Southeast Asia. There have been widespread impacts on countries’ economic development, social systems and public well‑being. The first COVID case was reported in the region as early as January 2020, with all Southeast Asian countries reporting at least one case by March 2020. While many of the countries managed to contain the spread of the virus during the first wave of the pandemic, the emergence of variants, particularly B.1.617.2 (Delta), accelerated the rate of infection in the region. As of 10 May 2022, a total of over 3 million cases had been reported in the region, representing an infection rate of 9 480 cases per 100 000 population – higher than the equivalent at the global level (6 609 cases), but much lower than across OECD countries (30 486 cases). Rates of full vaccination (as of November 2022) vary widely across countries – from as low as 50.6% in Myanmar to as high as 101.9% in Brunei Darussalam – with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) average (77.8%) performing slightly better than that of the OECD (74%) (WHO, 2022[14]).

COVID‑19 has significantly impacted Southeast Asian economies, slowing down the impressive growth many countries had been experiencing prior to the pandemic. All countries experienced drops in real GDP growth rates from 2019 to 2020, with the worst-hit economies being the Philippines (‑9.6%), Thailand (‑6.1%) and Malaysia (‑5.6%) (IMF, 2022[15]). In 2021, the pandemic wiped out an estimated 9.3 million jobs and pushed 4.7 million people into extreme poverty in Southeast Asia, many of them being low-skilled workers and those employed in agro-processing, garments, retail and tourism, the informal economy and businesses with low digitalisation uptake. While countries have begun to slowly recover, the region’s economic output in 2022 is projected to remain 10% weaker than that of a scenario without COVID‑19 (ADB, 2022[16]; 2022[17]; The Asia Foundation, 2020[18]).

The pandemic has greatly affected the way skills are being developed and used in Southeast Asia, exacerbating existing skills imbalances in the region. School closures and social distancing measures have shifted education on line, putting at risk students without access to reliable Internet, digital devices and conducive learning environments at home. The pandemic has also led to reductions in informal and non-formal learning opportunities, including internships, apprenticeships and work-based learning programmes (OECD, 2020[19]). Moreover, the intensity of skills use in workplaces has dropped significantly, with member countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) experiencing an average 7.3% loss in working hours due to COVID‑19 – higher than OECD countries with available data, including Australia, Germany, Korea and Japan (ILOSTAT, 2021[20]). Containment measures have also led to increases in remote work, which have led to benefits, such as reductions in commuting time, but also challenges in employee well-being and productivity (Eurofound and ILO, 2017[21]; Messenger, 2019[22]).

Skills should be at the core of Southeast Asia’s policy response

Megatrends and shocks, such as the COVID‑19 pandemic, reinforce the need for Southeast Asia to design forward-looking and dynamic skills policies. To thrive in the world of tomorrow, people will need a comprehensive set of skills (Box 1.1). Strong foundational skills will make people more adaptable and resilient to changing skills demands. Digital, transversal, social and emotional, and job-specific skills (OECD, 2019[7]) are becoming increasingly essential for individuals to succeed in learning, work and life. High-quality learning across the life course should be accessible for everyone to enable full participation in society and to successfully manage transitions in the labour market. Adults need continuous opportunities to upskill and reskill, and learning providers need to create more flexible and blended forms of learning to accommodate this. Firms must adopt more creative and productive ways of using their employees’ skills. Finally, robust governance structures are needed to ensure that skills reforms are effective and sustainable.

Box 1.1. A wide range of skills are needed for success in work and life

The OECD Skills Strategy 2019 identifies a broad range of skills that matter for economic and social outcomes, including:

Foundational skills: Including literacy, numeracy, and digital literacy.

Transversal cognitive and meta-cognitive skills: Including critical thinking, complex problem solving, creative thinking, learning to learn and self-regulation.

Social and emotional skills: Including conscientiousness, responsibility, empathy, self‑efficacy and collaboration.

Professional, technical, and specialised knowledge and skills: Needed to meet the demands of specific occupations.

Source: OECD (2019[7]), OECD Skills Strategy 2019: Skills to Shape a Better Future, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264313835-en.

The OECD Skills Strategy project in Southeast Asia

The OECD Skills Strategy Framework provides countries with a comprehensive model for analysing the performance of countries’ skills systems, benchmarking performance internationally and exploring good practices internationally. The framework has three key dimensions (Figure 1.1):

Developing relevant skills over the life course: To ensure that countries can adapt and thrive in a rapidly changing world, all people need access to opportunities to develop and maintain strong proficiency in a broad set of skills. This process is lifelong, starting in childhood and youth and continuing throughout adulthood. It is also “life-wide”, occurring both formally in schools and higher education and non-formally and informally in the home, community and workplaces.

Using skills effectively in work and society: Developing a strong and broad set of skills is just the first step. To ensure that countries and people gain the full economic and social value from investments in developing skills, people also need opportunities, encouragement and incentives to use their skills fully and effectively at work and in society.

Strengthening the governance of skills systems: Success in developing and using relevant skills requires strong governance arrangements to promote co‑ordination, co‑operation and collaboration across the whole of government; engage stakeholders throughout the policy cycle; build integrated information systems; and align and co‑ordinate financial arrangements. The OECD Skills Strategy project for Southeast Asia adopted this approach by forming an interdepartmental project team to support the whole-of-government approach to skills policies and by engaging a broad variety of stakeholders.

Figure 1.1. The OECD Skills Strategy Framework

Source: OECD (2019[7]), OECD Skills Strategy 2019: Skills to Shape a Better Future, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264313835-en.

This report was prepared after the initial outbreak of the COVID‑19 pandemic and makes recommendations that could facilitate Southeast Asia’s recovery, as well as recommendations to build the performance and resilience of Southeast Asia’s skills system in the longer term.

Overall, the OECD Skills Strategy project in Southeast Asia engaged around 115 participants who represented ministries and agencies, municipalities, education providers, employers, workers, researchers and other sectors. From January to November 2022, 20 bilateral meetings were held with regional actors, such as the ASEAN Secretariat, the ASEAN Trade Union Council, the ASEAN Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) Council, the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO), and ASEANstats, among others, as well as with national government agencies, including ministries responsible for education and employment, and national statistics offices. Key development partners in the region were also consulted, including international development agencies and research centres. The bilateral meetings sought to enrich the report with local insights and help the OECD team develop a deeper and more nuanced understanding of each country’s skills challenges and opportunities.

Furthermore, through the ASEAN TVET Council, the OECD Skills Strategy Southeast Asia Policy Questionnaire was administered to relevant government agencies and stakeholders to gather cross‑country comparative data on various topics, including education and employment measures adopted in response to the COVID‑19 pandemic. Responses were received from five countries (Cambodia, Malaysia, Myanmar, Singapore and Viet Nam).

The OECD also organised the Southeast Asia Regional Policy Network on Education and Skills, with the 11th meeting taking place in November 2021 and the 12th meeting in November 2022. Each meeting convened approximately 80 participants from ASEAN, partner countries in Southeast Asia, OECD countries and international organisations. The 11th meeting focused on Southeast Asian countries’ skills responses to COVID‑19 and the strategies they adopted in response to global megatrends, while the 12th meeting discussed skills in partnership. Both events informed the report by promoting exchanges between OECD and Southeast Asian countries on best policy practices and areas for co‑ordinated intervention.

The performance of Southeast Asia’s skills system

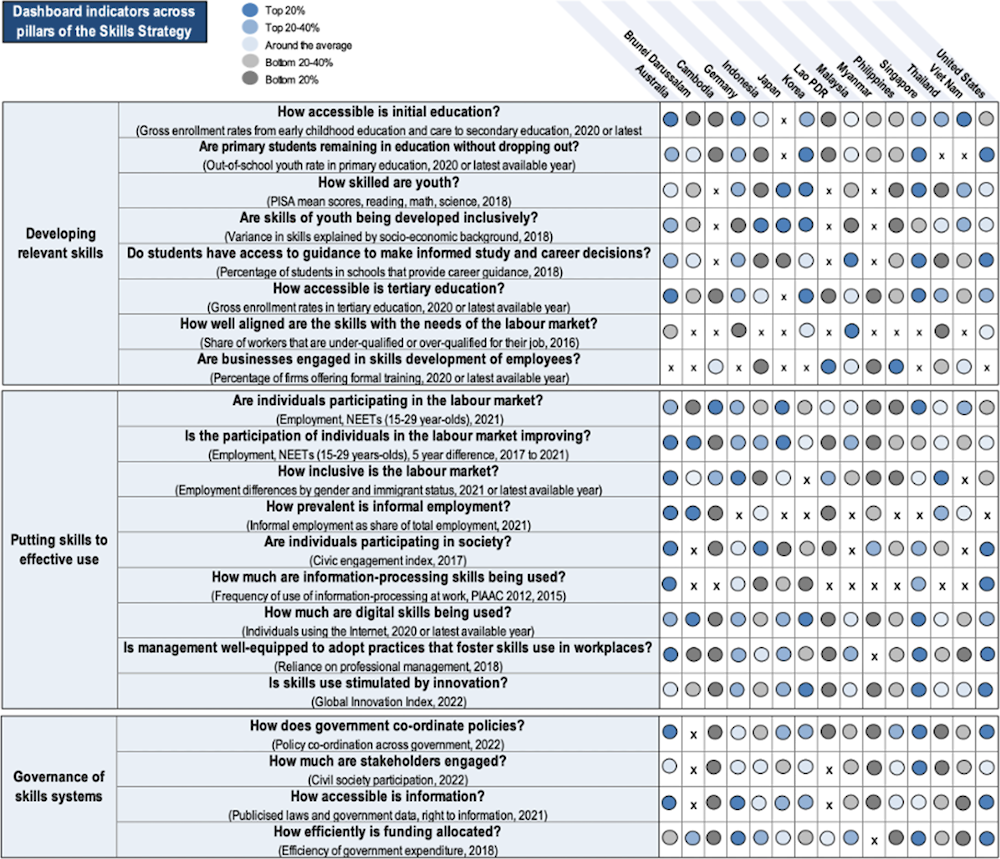

The OECD Skills Strategy Dashboard provides an overview of the relative performance of countries across the dimensions of the OECD Skills Strategy (Figure 1.2). For each dimension of the strategy, there are a number of indicators, some of which are composite indicators, which provide a snapshot of each country’s performance (see Figure 1.2 for the indicators).

Developing relevant skills over the life course

Access to skills development has improved at all levels of education, but many barriers remain, especially for disadvantaged groups

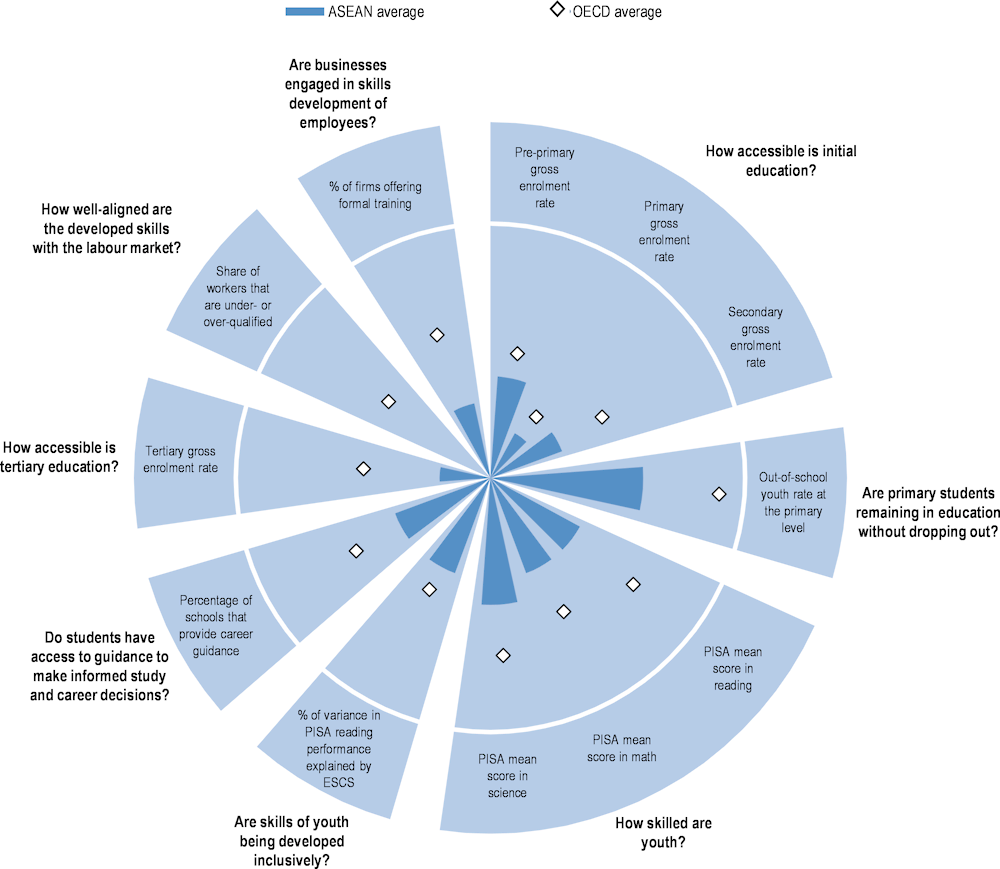

Southeast Asian countries have made considerable progress in increasing participation in skills development over the life course. Figure 1.3 presents the key indicators of the dimension “Developing relevant skills over the life course” in the dashboard presented in Figure 1.2and shows the average performance of ASEAN countries and OECD countries relative to each other. Over the years, countries in Southeast Asia have succeeded in boosting enrolment rates in early childhood education and care (including pre-primary education), compulsory education, TVET, tertiary education and adult learning. However, at all levels, enrolment rates in Southeast Asia still generally fall behind those of OECD countries, and out-of-school children rates are nearly four times larger in the region than in the OECD. Participation in skills development also tends to be lower at later stages of life, such as in tertiary education and adult learning. For instance, while average 2019 enrolment rates throughout Southeast Asia were high at the primary (103.4%) and secondary (84.3%) levels, the rates at the tertiary level (36%) are far lower (World Bank, 2021[23]).

Figure 1.2. OECD Skills Strategy Dashboard: Southeast Asia and selected benchmarking countries, 2022

Note: The Skills Strategy Dashboard has a focus on outputs of the skills system. Colours in the dashboard represent the quintile position of the country in the ranking, and “x” indicates insufficient or no available data for the underlying indicators. See Annex Table 1.A.1 in Annex 1.A1 for a more detailed analysis and an overview of the underlying indicators. The ranking of ASEAN countries is relative to other ASEAN countries and the five benchmarking OECD countries (Australia, Germany, Japan, Korea and the United States).

Participation in skills development over the life course remains highly unequal across groups in Southeast Asia. Consistently across all levels of education, access to learning is limited for learners from low-income households, remote areas, ethnic minorities and learners who have disabilities (SEAMEO INNOTECH, 2021[24]; The HEAD Foundation, 2022[25]). Moreover, among the working-age population, access to training remains limited, with only 48.8% of large firms, 36.1% of medium-sized firms, and 16.8% of small firms offering training to their employees (World Bank, 2020[26]). Moreover, the lack of access to training among workers in Southeast Asia’s sizeable informal economy is one of the region’s principal policy concerns. It is estimated that there are about 244 million informal workers throughout the region who do not have access to social security or employment benefits, including employer-sponsored training (ASEAN, 2022[27]; ASEAN Secretariat, 2019[28]; OECD, 2021[29]).

Figure 1.3. Performance of ASEAN countries and OECD countries in developing relevant skills, 2022

Note: ESCS stands for economic, social and cultural status. OECD average is based on the performance of the 38 OECD countries.

How to read this figure: The normalised scores indicate the relative performance, 0 for weakest performance and 10 for strongest performance across OECD countries. The further away from the core of the chart, the better the performance.

Source: See Annex Table 1.A.1 in Annex 1.A1 for an explanation of sources and methodology.

Improving the quality of learning – both in school and at home – is a key policy concern in Southeast Asia

The skills performance of Southeast Asian learners remains low in international comparison, raising questions about the quality of education. For instance, the performance of Southeast Asian students in the latest round of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) in 2018 remained well below the OECD average in reading, mathematics and science, although Singapore was a top-performing country (OECD, 2019[30]). Literacy, especially among adults, has not reached universal rates in the region (89.9%) and remains relatively low in certain countries, such as Lao PDR (70.4%), Cambodia (81.9%) and Myanmar (88.9%) (World Bank, 2022[31]). Moreover, digital literacy is a key policy concern, especially as economic activities become more dependent on technology. Only 28% of youth and adults in Southeast Asia possess the digital skills needed in the workplace compared to 44.5% across OECD countries (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2021[32]).

Material and human resource limitations in schools, especially in disadvantaged areas, negatively impact students’ skills outcomes. For instance, only 34% of children in Cambodia, 56% in Lao PDR and 58% in Myanmar had access to a classroom library. The lack of learning materials is especially pronounced in rural areas, which risks widening location-based equity gaps in education (UNICEF and SEAMEO INNOTECH, 2022[33]; Oblina, Linh and Phuong, 2021[34]). In addition, large class sizes and varying student profiles (in terms of language and skill level) make it difficult for teachers to provide well‑tailored and focused instruction to their students (UNICEF and SEAMEO INNOTECH, 2022[33]).

In addition to challenging conditions in schools, the lack of stimulating learning environments at home contributes to the low performance of Southeast Asian learners. Children from low-income households often do not have access to learning materials, such as books and playthings. Those in the poorest quintile are 28.2 percentage points less likely to live in a positive and stimulating home than children in the wealthiest quintile (UNICEF, ILO and WIEGO, 2021[35]). Parents who are migrants or work in the informal economy with long and unregulated working hours are less able to support the development of children’s skills and engage in healthy learning relationships with them (UNICEF, ILO and WIEGO, 2021[35]). Moreover, the lack of digital infrastructure and devices has made it difficult for many disadvantaged learners to continue participating in education in the context of the COVID‑19 pandemic (UNICEF and ASEAN, 2021[36]).

Southeast Asia needs to better ensure people develop skills that are in line with evolving skills demands

Considering rapid changes in labour markets, Southeast Asian countries must ensure students’ access to relevant and higher-level skills. Enrolment in educational programmes in key sectors, such as those related to science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) at the tertiary level, has increased in all countries over the last decade by an average of 6.8 percentage points (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2021[32]). Despite this progress, the content of tertiary education curricula remains outdated in many cases, and many higher education institutions lack the infrastructure and human resources needed to adequately develop emerging and highly technical skills (CISCO and Oxford Economics, 2018[37]; ASEAN University Network, 2017[38]; Cunningham et al., 2022[39]).

Offering better skills, labour market information and more guidance counsellors can help the Southeast Asian workforce develop relevant skills and reduce skills mismatches. At present, skills mismatches by level of qualification and field of study are significant in countries with available data (i.e. Singapore and Thailand). Under-qualifications are prevalent in Singapore, where 20% of workers are under-qualified, while over-qualifications are highest in Thailand, where 34% of workers are over-qualified for their jobs. Field-of-study mismatches are significantly high in both countries: 43% in Singapore and 37.3% in Thailand (OECD, 2019[40]). In addition to these current mismatches, an estimated 6.6 million Southeast Asian workers will become redundant over the next decade, as they are in jobs that will disappear due to technological advancements, highlighting the need for targeted career guidance support and more relevant reskilling and upskilling opportunities (ASEAN, 2021[41]; CISCO and Oxford Economics, 2018[37]). However, the use of skills data to identify emerging skills needs remains limited, which makes it difficult for career guidance counsellors to provide relevant information on relevant training offers (Intad, 2021[42]; Muhamad, Salleh and Nordin, 2016[43]). Moreover, the supply of qualified career guidance counsellors remains limited in Southeast Asia, especially among disadvantaged groups, whose access to career guidance counsellors is about 8 percentage points below that of advantaged groups (OECD, 2019[44]; Saputra and Sudira, 2019[45]).

Using skills effectively in work and society

Southeast Asian countries’ performance on key labour market indicators has improved, but many challenges remain

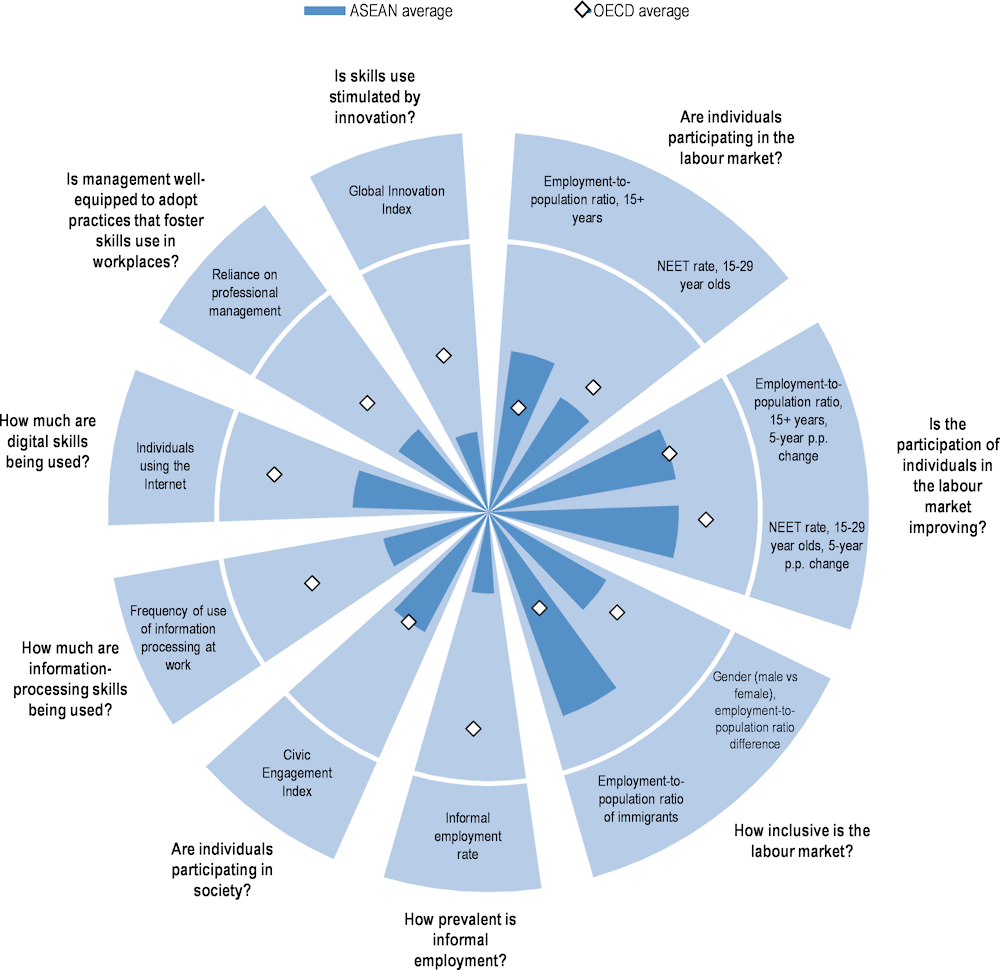

Formal labour force participation rates in Southeast Asia are generally high, owing to various targeted policy interventions. The average labour force participation in ASEAN countries stood at 67.7% in 2021, surpassing that of the OECD (59.6%) (Figure 1.4), and has remained relatively stable over the last ten years, fluctuating only between 65.6% and 68.2% from 2011 to 2021 (ILOSTAT, 2021[46]). Governments in the region have aimed to enlarge the size of the workforce by improving employment support services and strengthening international labour mobility. However, full and effective participation remains a challenge for many disadvantaged groups, such as women, whose participation rate is 29 percentage points below that of men. Youth and migrants participating in the labour force are also more likely to be found in part-time work and low-skilled occupations (Gentile, 2019[47]; Eurostat, 2022[48]).

The skills of people in Southeast Asia could be used more fully and effectively in everyday life. The use of basic skills, such as reading, writing, numeracy, and information and communication technology skills, in everyday life are lower in Southeast Asian countries with available data (Indonesia and Singapore) than in OECD countries. This is an area of policy concern, as the use of these skills is associated with higher levels of social trust and greater participation in civic activities. Consequently, participation rates in civic activities across Southeast Asia are also relatively low, especially in some countries, such as Cambodia, Thailand and Viet Nam, where less than 20% of individuals in the working-age population have volunteered time to an organisation (OECD, 2019[49]). Rates may vary depending on country context, for example, to what extent volunteering is encouraged from a young age in the formal education system and, more generally, in society at large.

Disadvantaged groups face multiple challenges in fully and effectively using their skills

Widespread employment in the informal sector is a primary policy concern in Southeast Asia. On average, 71% of those who are employed in the region are found in the informal sector, with informal employment rates being significantly high in nearly half of ASEAN countries, namely Cambodia (88%), Lao PDR (83%), Indonesia (80%) and Myanmar (80%) (ILOSTAT, 2021[50]). This constitutes a key policy concern in Southeast Asia, as informal employment is associated with poor working conditions, such as lower compensation, fewer employee benefits and lack of access to skills development opportunities, which not only lowers productivity but also makes informal workers particularly vulnerable to labour market changes brought about by global megatrends (ILO, 2019[51]).

Women in Southeast Asia disproportionally face barriers to participating in the formal labour force. Gender gaps are significant in the region, and when women are working, many of them are found in the informal sector and low-productivity and low-pay sectors, such as food, accommodations, essential domestic work and manufacturing (ILO, 2019[52]; ILOSTAT, 2021[46]; Lai, 2020[53]). In addition, women face multiple barriers to participating in the formal labour market, such as unpaid care work that lessens the amount of time they can devote to economically productive activities. While the burden of unpaid care work more often falls on women around the world, these expectations are especially pronounced in Southeast Asia, where women spend 4.2 times longer hours than men on unpaid care work, in comparison to 2.2 times in OECD countries (OECD, 2019[54]). The COVID‑19 pandemic and lockdown measures have also exacerbated the situation of women, who have assumed the extra work associated with children’s remote learning following the closure of schools (OECD, 2021[55]).

Figure 1.4. Performance of ASEAN countries and OECD countries in using skills effectively, 2022

Note: NEET refers to “not in education, employment or training”. “5-year p.p. change” refers to a 5-year percentage points change. OECD average is based on the performance of the 38 OECD countries.

How to read this figure: The normalised scores indicate the relative performance across OECD countries: the further away from the core of the chart, the better the performance. For example, the indicator “How much are digital skills being used” shows a lower score for the ASEAN average, indicating that the share of individuals using digital skills is lower than the OECD average.

Source: See Annex Table 1.A.1 in Annex 1.A1 for an explanation of sources and methodology.

In addition to women, other disadvantaged groups in Southeast Asia, such as migrants and youth, face challenges in securing productive and meaningful employment. While migrants have higher labour market participation rates than native populations in all countries with available data (Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Malaysia and Thailand), many of them have low levels of skills and are employed in low-skilled sectors, namely agriculture, construction and domestic services (Gentile, 2019[47]; ILOSTAT, 2021[46]). Similarly, there are many challenges in finding employment for youth in Southeast Asia, who face employment barriers, such as a lack of previous work experience (ILO, 2020[56]). As a result, youth often take about 11.6 months to find their first job and an even longer 13.8 months to find a job that is up to their satisfaction (ILO, 2019[57]; 2020[56]).

Policies that increase demand for higher-level skills and promote their use need to be strengthened in Southeast Asia

The low use of skills in Southeast Asia stems from the lack of an enabling environment for intensive skills use in the workplace and limited management capacities among employers. Adopting high‑performance workplace practices (HPWPs) is key to facilitating the more extensive use of skills among workers. However, awareness about them remains scarce, especially among small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) (OECD, 2019[7]). This is a concerning policy issue in Southeast Asia, where SMEs dominate the business environment and account for 97% of countries’ total firms (ADB, 2020[58]). Evidence on the use of HPWPs in Southeast Asia is extremely limited. However, available data show that the share of jobs employing HPWPs in Singapore (26%) is close to that of the OECD average (27%) but is extremely low in Indonesia (1.98%) (OECD, 2018[59]). The capacity to maximise the use of HPWPs is also restricted by the limited management capacity of SMEs in Southeast Asia, where reliance on professional management is lower than that of the OECD (World Economic Forum, 2019[60]).

Southeast Asian countries could benefit from policies that foster demand for the use of higher-level skills in innovation and entrepreneurship. While enrolment in STEM programmes has risen in all countries in Southeast Asia over the last decade, countries invest only 0.59% of their GDP on research and development (R&D) activities, in comparison to 2.57% in OECD countries (UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 2021[32]). Moreover, Southeast Asia scores 14 points lower than the OECD on the Global Innovation Index, which measures how well various country-level factors (e.g. political and business environments) can support innovation (Cornell University, INSEAD and World Intellectual Property Organization, 2020[61]).

Strengthening the governance of skills systems

Southeast Asian countries have established mechanisms to improve co‑ordination among various actors inside and outside of government, but implementation challenges remain

Horizontal and vertical co‑ordination mechanisms for skills policies in Southeast Asia have been established, but implementation remains difficult. Countries have established oversight agencies, inter-ministerial bodies and working groups, among other mechanisms, that could serve as platforms to work a common skills agenda across the whole of government. However, Southeast Asia still scores poorly on the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) indicator on policy co-ordination, which measures the extent to which governments can co‑ordinate conflicting objectives into a coherent policy. On average, ASEAN countries score 5.5 points on a scale of 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest), in comparison to 6.9 points among OECD countries (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2020[62]).

Outside of government, stakeholder groups can make important contributions to skills policies, but engagement with them remains low in Southeast Asia. It is important to co‑ordinate with labour market actors, such as employer organisations, who can help align skills policies with industry demands, as well as with trade unions, who can represent the interests and needs of workers. However, the formation of employer organisations is limited by high rates of informality in the region (ILO, 2015[63]). Moreover, only 8.5% of workers in Southeast Asia are members of trade unions, in comparison to 15.8% in the OECD (ILOSTAT, 2020[64]; OECD, 2020[65]). While civil society organisations, such as non-governmental organisations, community-based organisations and religious groups, work to promote the development and use of skills of women, migrants and youth, only a few Southeast Asian governments formally recognise their roles in major skills policy documents (Chong and Elies, 2011[66]; Weaver, 2006[67]).

The collection, management and use of skills data in Southeast Asia could be improved to better inform skills policies

There are many barriers to collecting and managing high-quality, up-to-date and comprehensive data on skills in Southeast Asia. Most Southeast Asian countries have fewer measures in place to facilitate access to information, such as government data, that could be used to inform skills policies (World Justice Project, 2021[68]). Among the data available, there are still significant gaps remaining, particularly on the development of skills among disadvantaged groups, namely out-of-school youth, learners from remote areas and children with disabilities. There is also limited data collected on the effective use of skills in the workplace, such as information on the skills firms need and the employer initiatives in place to facilitate their full and effective use in the workplace (UNESCO Office Bangkok and Regional Bureau for Education in Asia and the Pacific, 2017[69]; UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning, 2016[70]).

Data could also be better managed and used in Southeast Asia to inform skills policies. Central to the management of skills data is a robust digital infrastructure. However, many countries in the region do not have the sufficient information technology hardware and software needed to manage and process the data that has been collected (Open Data Watch, 2020[71]). In addition to managing data, it is equally important to ensure that countries in the region use the data to understand evolving skills supply and demand trends. However, the use of data through skills assessments and anticipation exercises remains limited in the region, although some countries have notable initiatives in place to facilitate the use of such exercises (e.g. Malaysia TalentCorp’s skills assessments based on the Labour Force Survey and Salaries and Wages Survey).

Southeast Asian countries could diversify financial resources and allocate them in a more equitable manner

Public funding for education could be supplemented with private funding, particularly from employers. Average government spending on education in Southeast Asia is lower than in OECD countries at all levels of education. While countries allot a substantial portion of GDP per capita to education, it is still significantly lower than OECD countries at the primary level (11.3% in ASEAN, 20.3% in the OECD), secondary level (16.9% in ASEAN, 22.4% in the OECD) and tertiary level (22.8% in ASEAN, 25.4% in the OECD) (World Bank, 2021[23]). Government investment in TVET as a percentage of GDP is also significantly lower in Southeast Asia (0.16%) than it is in OECD countries (0.5%) (AFD, 2019[72]; OECD, 2022[73]). Private funding from employers could help augment financial resources for skills in Southeast Asia, but engagement with them remains relatively low across the region. Several types of employer-driven financing mechanisms exist, such as levy-sponsored skills development funds (e.g. Malaysia and Singapore’s Human Resource Development Fund, Thailand’s “train or pay” approach to their Skills Development Fund). However, their use in other countries is limited (UNESCO, 2022[74]).

Monitoring and evaluating financial expenditure in Southeast Asia could be strengthened to better assess the achievement of equity goals. Countries in the region have funding arrangements in place to allot financial resources specifically for disadvantaged groups, leaving discretion to schools on how to allocate the funding for different elements based on their students’ needs (e.g. Philippine Department of Education’s block grant through the Governance of Basic Education Act of 2001) (Philippines Department of Education, 2015[75]). However, while such financial mechanisms are important to fostering equity, monitoring and evaluation measures that ensure transparency and accountability are also key, especially when they are conducted in partnership with a wide range of stakeholders, such as those represented on school boards (OECD, 2017[76]). While school boards have been established in Southeast Asian countries, many challenges remain, such as an inadequate infrastructure for monitoring school expenditure, weak planning and budgeting practices, and the lack of processes that check for accountability in school budgets, among others (Robredo, 2012[77]).

The policy context in Southeast Asia

A range of policy reforms in Southeast Asia recognise the importance of skills

Southeast Asia has already developed a range of strategies and reforms to help countries respond effectively to megatrends, addressing challenges and seizing the opportunities they present to countries’ skills systems. The relevant priorities and goals of these strategies are summarised at the beginning of each chapter in this report, as assessed considering the OECD’s analysis and recommendations. Furthermore, as elaborated in subsequent chapters, Southeast Asia has embarked on a range of skills policy reforms in recent years, covering all aspects of the skills system, namely skills development, skills use and the governance of skills systems.

Southeast Asian countries have prioritised increasing participation in skills development, especially among disadvantaged groups, and improving the quality of education. Many countries have made education and training the foundation of their national development plans, explicitly recognising the importance of skills development in their ability to adapt to labour market changes, increase competitiveness and foster social cohesion (ASEAN, 2020[78]). Measures have been put in place to address issues in educational quality, such as the upskilling of teachers and school leaders to help them prepare for pedagogical and administrative challenges in the education system, the upgrading of classrooms and educational infrastructure, the reinforcement of educational quality assurance bodies, the strengthening of links between schools and industries, the improvement of data collection for skills policies, and the adoption of performance-based funding in schools (Lee, 2016[79]; SEAMEO INNOTECH, 2020[80]). In these policy efforts, particular attention has been paid to disadvantaged learners, with governments affirming their commitment to making high-quality education and training accessible to all regardless of gender, socio‑economic background, location and ethnicity (UNESCO Office Bangkok and Regional Bureau for Education in Asia and the Pacific, 2017[69]).

Southeast Asia has also launched policy initiatives to reduce barriers to formal labour market participation, aiming to boost the region’s economic productivity and competitiveness. These include improving the delivery of public employment services that provide school-to-work transition support for young graduates and job seekers (especially during the COVID‑19 pandemic), as well as promoting the use of HPWPs that foster both employee productivity and well-being in the workplace. Innovation and entrepreneurship have been on the rise in the region, with many countries actively promoting the demand for higher-level skills in key strategic sectors (e.g. STEM), strengthening links between higher education institutions and firms, and investing in R&D activities through the provision of research grants and incentives to innovative start-ups and SMEs. In all these efforts, increased policy attention has been given to disadvantaged groups in Southeast Asia, notably informal workers, women, youth and migrants. Throughout the region, there is a strong political commitment given to boosting their participation in the formal economy, as well as the protection of their rights in the workplace (ILO, 2016[81]; Gentile, 2019[47]).

There have also been policy efforts to make the governance of skills systems in Southeast Asia more equitable and responsive to the needs of students and workers. Countries in the region have established multiple mechanisms to improve horizontal and vertical co‑ordination across government (e.g. oversight agencies, policy development forums), as well as create more room for civil society groups to participate and advance the interests of disadvantaged groups in the design of skills policies (UNESCAP, 2019[82]). There are also efforts underway in individual countries to increase engagement with industry representatives for various objectives, including making educational systems more responsive to labour market needs and incentivising employers to contribute resources to skills development (ILO, 2020[83]). Moreover, Southeast Asia is participating more and more in the conduct of skills assessments, including at the international level, to benchmark the region’s performance against other countries and better inform the design of skills policies (Cambodia MoEYS, 2018[84]).

Southeast Asia should seize this moment to adopt a more strategic approach to its skills policies

ASEAN is now amid a new round of strategy development for the medium and long term. This gives Southeast Asia a unique window of opportunity to implement a more strategic approach to skills to help drive economic prosperity, social cohesion and sustainable growth. Some of these key strategies and regional initiatives are shown in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1. ASEAN policies and strategies relevant to skills

|

Title of policy or strategy |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Consolidated Strategy on the Fourth Industrial Revolution for ASEAN (2021) |

Increases the competitiveness of Southeast Asian countries in increasingly digital economies and implements forward-looking human resource development initiatives Promotes capacity building to support the region’s Fourth Industrial Revolution reforms |

|

ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework and its Implementation Plan (2020) |

Outlines the region’s exit strategy from the COVID‑19 pandemic, focusing on key sectors and groups that have been disproportionately affected Highlights human resource development as the core of all five Broad Strategies |

|

ASEAN Declaration on Human Resources Development for the Changing World of Work and its Roadmap (2020) |

Promotes lifelong learning and increases inclusiveness of education and employment services, especially for women, persons with disabilities, the elderly, learners in rural or remote areas and workers in SMEs |

|

ASEAN Labour Ministers’ Statement on the Future of Work: Embracing Technology for Inclusive and Sustainable Growth (2019) |

Strengthens the capacity of educational institutions to prepare their workforce, especially disadvantaged groups (e.g. women, persons with disabilities, elderly, youth) for labour market changes due to technological advancements Outlines the importance of closer co‑operation with industries, the improvement of TVET standards and the expansion of reskilling and upskilling offers for workers |

|

ASEAN Consensus on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers (2017) |

Establishes a framework for co‑operation on issues related to the employment and working conditions of migrant workers in the region Encourages the formal employment of migrants and promotes access to labour market information and skills development offers for migrant workers |

|

Vientiane Declaration on Transition from Informal Employment to Formal Employment towards Decent Work Promotion in ASEAN (2016) |

Reduces informal employment in the region and assesses the factors contributing to informal employment, especially in rural areas Promotes policy measures to facilitate wider access to skills development (especially TVET), employment promotion (including in entrepreneurial sectors) and labour protection. |

Source: ASEAN (2020[85]), ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework and its Implementation Plan, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/ASEAN-Comprehensive-Recovery-Framework_Pub_2020_1.pdf; ASEAN (2017[86]), ASEAN Consensus on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ASEAN-Consensus-on-the-Protection-and-Promotion-of-the-Rights-of-Migrant-Workers1.pdf; ASEAN (2020[87]), ASEAN Declaration on Human Resources Development for the Changing World of Work and its Roadmap, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/ASEAN-Declaration-on-Human-Resources-Development-for-the-Changing-World-of-Work-and-its-Roadmap_Final_19Feb2021.pdf; ASEAN (2019[88]), Labour Ministers’ Statement on the Future of Work: Embracing Technology for Inclusive and Sustainable Growth, https://asean.org/asean2020/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ASEAN-Labour-Ministers-Statement-on-the-Future-of-Work-Embracing-Techno.pdf; ASEAN (2021[89]), Consolidated Strategy on the Fourth Industrial Revolution for ASEAN, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/6.-Consolidated-Strategy-on-the-4IR-for-ASEAN.pdf; ASEAN (2016[90]), Vientiane Declaration on Transition from Informal Employment to Formal Employment towards Decent Work Promotion in ASEAN, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Vientiane-Declaration-on-Employment.pdf.

The assessment and recommendations in this report can feed into these processes to help ensure that Southeast Asia’s skills priorities, policies and investments over the next decade improve outcomes across the skills system.

OECD Skills Strategy dimensions and recommendations

Applying the OECD Skills Strategy Framework, the OECD analysed the performance of Southeast Asian countries across the three dimensions of the OECD Skills Strategy. Over the course of the project, the OECD identified opportunities for improvement and developed recommendations in each dimension based on in-depth desk analysis and consultations with stakeholder representatives. The three dimensions are: 1) developing relevant skills over the life course; 2) using skills effectively in work and society; and 3) strengthening the governance of skills systems.

The skills implications of megatrends, such as globalisation, technological progress, demographic changes, migration and climate change, as well as unforeseen shocks, such as the COVID‑19 crisis, are covered in Chapter 2.

The summaries below highlight the key findings and recommendations for each dimension, while subsequent chapters provide a fuller description of these. A full overview of the recommendations can be found in Annex 1.B.

Dimension 1: Developing relevant skills over the life course (Chapter 3)

Opportunity 1: Broadening access to skills development

Access to skills development must start from the early years, given that foundational skills lay the groundwork for the acquisition of higher-level skills later in life (OECD, 2019[91]; 2021[92]). Continued participation in education after compulsory schooling also ensures that individuals have relevant, higher‑level skills that will help them succeed in work and life (OECD, 2019[7]). Southeast Asian countries have adopted various policies to expand access to skills development over the life course. However, room remains to improve participation rates in post-compulsory education, particularly in TVET, tertiary education and adult education. Across all levels, particular policy attention must be paid to disadvantaged groups, such as those coming from low-income households, remote areas, ethnic minorities and those who have disabilities (SEAMEO INNOTECH, 2021[24]; The HEAD Foundation, 2022[25]). Opportunity 1 describes how Southeast Asian countries can broaden access to skills development (Table 1.2).

Table 1.2. Opportunity 1: Broadening access to skills development

|

Policy directions |

High-level recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Improving access to early childhood education and care and compulsory education for disadvantaged groups |

1.1. Establish strong monitoring systems to detect children who have failed to enter the education system, as well as those who are at risk of dropping out 1.2. Support provision of learning materials parents can use at home 1.3. Strengthen digital infrastructure, digital education platforms, and digital literacy to broaden access to skills development opportunities, especially among disadvantaged groups and during times of disruption |

|

Promoting access to skills development after compulsory education |

1.4 Adopt a comprehensive policy strategy to address both supply- and demand-side barriers to technical and vocational education and training participation 1.5 Facilitate access to tertiary education by reducing the most significant financial barriers, both in terms of tuition fees and the cost of learning materials 1.6 Create a comprehensive national adult learning strategy that targets disadvantaged groups and facilitates their participation. |

Opportunity 2: Increasing excellence and equity in skills development

Well-qualified teachers and school leaders, adequate funding and strong student assessment systems are indispensable parts of skills development systems, as these ensure that learners have access to the high‑quality instruction and learning experiences they need (Baker, 2017[93]). In Southeast Asia, there are efforts to improve educational quality, including the provision of training for school personnel, upgrading of classrooms and educational infrastructure, the strengthening of student assessment practices and the use of performance-based funding mechanisms (Lee, 2016[79]; SEAMEO INNOTECH, 2020[80]). However, improvements in student performance have been unequal, and many learners in disadvantaged schools still encounter barriers to learning in the classroom, such as large classroom sizes, insufficient instructional support and a lack of learning materials. Identifying solutions to these challenges is hindered by limited capacity to use data on student assessment to inform schools’ policies, as well as low levels of management skills among school leaders (SEAMEO INNOTECH, 2012[94]; UNESCO, 2020[95]). At the regional level, sharing best practices in designing, implementing and using student assessments could be expanded. Opportunity 2 describes how Southeast Asian countries can increase excellence and equity in skills development (Table 1.3).

Table 1.3. Opportunity 2: Increasing excellence and equity in skills development

|

Policy directions |

High-level recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Improving the quality of human resources in schools |

1.7. Invest in professional development opportunities for teachers to equip them with better pedagogical skills 1.8. Consult regularly with school leaders about their various needs in terms of resources and upskilling |

|

Strengthening funding and student assessment in schools to improve equity |

1.9. Improve the financial management skills of school leaders and personnel 1.10. Establish avenues for relevant stakeholders to collaborate on improving student assessment systems. |

Opportunity 3: Developing skills that matter

As the world of work is constantly changing due to global megatrends and disruptions such as the COVID‑19 pandemic, ensuring the relevance of skills development is key to helping countries become economically competitive and foster social cohesion. In line with this, Southeast Asian countries have embarked on various initiatives to strengthen links between education and industry, increase the provision of work-based learning and on-the-job training, improve labour market information to inform the work of career guidance counsellors and provide incentives to steer individuals’ educational choices towards areas of skills shortage. However, there is significant room to help build the capacity of smaller firms to provide training for their employees and make career counselling more accessible to disadvantaged segments of the population, helping them access skills development offers that are in line with labour market demand. Opportunity 3 describes how Southeast Asian countries can develop skills that matter (Table 1.4).

Table 1.4. Opportunity 3: Developing skills that matter

|

Policy directions |

High-level recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Improving the alignment between skills development offers and labour market demand |

1.11. Increase the involvement of relevant government agencies and industry partners in reviewing the curricula of skills development offers in technical and vocational education and training and tertiary education 1.12. Increase the provision of on-the-job training opportunities, especially among workers in smaller firms and in the informal economy |

|

Steering skills development choices towards labour market needs |

1.13. Provide regular training to guidance counsellors and make updated labour market data more accessible to inform their work 1.14. Expand financial incentives for individuals and institutions to encourage the uptake of skills development in strategic industries, especially among disadvantaged groups. |

Dimension 2: Using skills effectively in work and society (Chapter 4)

Opportunity 1: Promoting participation in the formal labour market

Promoting participation in the formal labour market and making full use of people’s skills at work provides positive economic returns, improves individuals’ well-being, increases the size of the productive labour force and strengthens economic growth (OECD, 2019[7]). A range of interventions has been implemented in the region to promote employment, especially in the formal sector, such as expanding employment services, improving workplace conditions and simplifying processes to formally register and monitor workers and firms. However, more policy attention must be paid to extending these services to disadvantaged groups in Southeast Asia, such as women, youth, migrants, and informal workers, and tailoring these services to their specific needs. Given the large intra-regional migration flow, regional co‑operation in migration policies would need to be strengthened to improve cross-border recruitment and integration services. Opportunity 1 under this dimension describes how Southeast Asian countries can promote participation in the labour market (Table 1.5).

Table 1.5. Opportunity 1: Promoting participation in the labour market

|

Policy directions |

High-level recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Reducing barriers to employment for disadvantaged groups |

2.1. Facilitate women’s participation in the labour market through the promotion of a more equitable distribution of housework and encouraging flexible work arrangements 2.2. Support youth employment through tailored and online employment services 2.3. Enhance migrant employment possibilities through job search support, legal counselling and language training from specialised institutions for migrants |

|

Facilitating the transition of workers from the informal to the formal labour market |

2.4. Facilitate the registration of workers and businesses by making online business registration platforms more user-friendly and simplifying registration procedures 2.5. Improve the effectiveness and efficiency of labour inspection by adopting new technologies to ease the verification of workers’ employment status. |

Opportunity 2: Making intensive use of skills in work and society

Making full and effective use of skills in work and society is associated with higher wages and greater well‑being among individuals, translating into higher labour productivity, greater social cohesion and more inclusive economic growth (OECD, 2015[96]; 2016[97]; 2019[7]). In recognition of the importance of intensive skills use, some countries have begun to actively promote the adoption of HPWPs, as well as create opportunities to facilitate the use of skills outside of the workplace, such as volunteering and other civic activities. However, there is room to strengthen awareness about economic and societal benefits that accrue from both adopting HPWPs and participating more fully in civic life, as well as to facilitate these actions among firms and individuals, respectively. Opportunity 2 under this dimension describes how Southeast Asian countries can make intensive use of skills in work and society (Table 1.6).

Table 1.6. Opportunity 2: Making intensive use of skills in work and society

|

Policy directions |

High-level recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Promoting skills use in the workplace through the greater adoption of high-performance workplace practices |

2.6. Create a single portal in each country to efficiently disseminate comprehensive information on high-performance workplace practices to firms, especially SMEs 2.7. Improve the managerial skills in SMEs by providing networking and mentoring opportunities |

|

Promoting skills use in everyday life through civic engagement and leisure activities |

2.8. Make volunteering activities available as part of the school curricula to encourage young people to contribute their skills to society from an early age 2.9. Raise awareness about the benefits of using skills in society and personal life 2.10. Provide financial incentives to encourage adults to use skills in civil society. |

Opportunity 3: Increasing demand for higher-level skills

Promoting the development and use of higher-level skills is central to the ability of Southeast Asian countries to create more innovative products and services that will help them move up GVCs and boost economic competitiveness (OECD, 2019[7]). In recent years, there has been increasing public and private interest in creating a culture of innovation and entrepreneurship in Southeast Asia. However, there is room to improve funding for innovative and entrepreneurial activities and to foster networks of stakeholders that can exchange best practices and provide mentoring support, especially among disadvantaged groups. Opportunity 3 under this dimension describes how Southeast Asian countries can increase demand for higher-level skills (Table 1.7).

Table 1.7. Opportunity 3: Increasing demand for higher-level skills

|

Policy directions |

High-level recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Promoting innovation to increase demand for high-level skills |

2.11. Increase expenditure on research and development through direct grant support and tax incentives 2.12. Foster collaboration between institutions of higher education and industry |

|

Fostering entrepreneurship |

2.13. Improve access to finance for female entrepreneurs by providing targeted financial services combined with financial training 2.14. Facilitate the transfer of entrepreneurial knowledge and skills to women by supporting unions for female workers and business associations for women. |

Dimension 3: Strengthening the governance of skills systems (Chapter 5)

Opportunity 1: Promoting a whole-of-government approach

A whole-of-government approach to skills governance is crucial, given that skills encompass a wide variety of policy domains. The two components of a whole-of-government approach, namely horizontal co‑ordination and vertical co‑ordination, both contribute to developing a shared understanding of the skills agenda and reducing redundancies in policy implementation (ADB, 2015[98]; OECD, 2011[99]; Christensen and Lægreid, 2007[100]). In Southeast Asia, various mechanisms have been established to improve co‑ordination both horizontally (e.g. through oversight agencies, inter-ministerial bodies and sectoral bodies) and vertically (e.g. formal bodies, working groups and ad hoc meetings), but implementation challenges remain. These include a lack of clarity regarding the specific roles of each actor and inadequate human and financial capacity to implement reforms at subnational levels of government. Opportunity 1 under this dimension describes how Southeast Asian countries can promote a whole-of-government approach (Table 1.8).

Table 1.8. Opportunity 1: Promoting a whole-of-government approach

|

Policy directions |

High-level recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Strengthening horizontal co‑ordination |

3.1. Support skills-related inter-ministerial governance bodies in their engagement of all relevant ministries 3.2. Promote a shared skills goal among relevant ministries through strategic documents, such as national development plans and skills-related policy documents |

|

Strengthening vertical co‑ordination |

3.3. Support subnational governments in implementing skills policies by providing additional human and financial resources and capacity-building support. |

Opportunity 2: Promoting a whole-of-society approach

Promoting a whole-of-society approach to skills governance ensures that policies are relevant to labour market needs and adequately reflect the interests of a wide variety of stakeholders, especially disadvantaged groups (OECD, 2019[7]). Throughout Southeast Asia, there are formal and informal mechanisms for consultation with labour market actors, such as employer organisations and trade unions, as well as with civil society groups that represent informal workers, women, youth and migrants. However, participation in these consultation mechanisms remains low, and a co‑ordinated approach to consultations is complicated by actors’ varying capacity levels and differing priorities or interests. At the regional level, the role of stakeholder representatives (e.g. ASEAN Confederation of Employers and ASEAN Trade Union Council) in informing skills policies needs to be raised. Opportunity 2 under this dimension describes how Southeast Asian countries can promote a whole-of-society approach (Table 1.9).

Table 1.9. Opportunity 2: Promoting a whole-of-society approach

|

Policy directions |

High-level recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Identifying and engaging relevant labour market actors |

3.4. Establish legal frameworks to strengthen engagement with actors in the labour market 3.5. Strengthen the effectiveness of governance bodies engaging labour market actors |

|

Identifying and engaging relevant civil society actors |

3.6. Provide financial, technical and networking resources to facilitate the participation of women, as well as the organisations that represent them, in governance 3.7. Strengthen youth’s input in official governance bodies and development of youth strategies 3.8. Support migrant organisations’ active participation in governance bodies and influence in skills policies. |

Opportunity 3: Building integrated information systems

Building integrated information systems is central to gathering evidence that could be used to improve the relevance and effectiveness of skills policies. However, doing so is a complex process that involves multiple components, namely data collection, management and use, and requires effective co‑ordination between relevant government agencies (OECD, 2019[7]). Some Southeast Asian countries have pursued efforts to improve their stock of skills data by increasing participation in international student assessment exercises and adopting national data strategies. However, the ability to collect, manage and use skills data varies widely across Southeast Asian countries. Common challenges still exist, namely limited technical and financial resources to routinely collect and process data on a comprehensive list of skills indicators, as well as the lack of a robust infrastructure to manage and use large amounts of data. Regional co‑operation should be further enhanced to build capacity in collecting skills data that is consistent and compatible across Southeast Asian countries and can be used for regional skills analysis (e.g. skills assessment and anticipation exercises). Opportunity 3 under this dimension describes how Southeast Asian countries can build integrated information systems (Table 1.10).

Table 1.10. Opportunity 3: Building integrated information systems

|

Policy directions |

High-level recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Improving data collection |

3.9. Implement robust national data collection processes to address data gaps 3.10. Support participation in international surveys to generate internationally comparable data |

|

Improving the management and use of skills data |

3.11. Establish the institutional and legal groundwork for integrating data management systems 3.12. Regularly conduct skills assessment and anticipation exercises to design and update skills policies. |

Opportunity 4: Aligning and co-ordinating financial arrangements

Diversified financial resources and equitable mechanisms for allocation are needed to support the sustainability of skills governance systems. A diverse set of financial sources is needed to pool funding for skills development, especially in resource-constrained countries. Equitable funding formulas could help maximise a limited amount of resources (Fazekas, 2012[101]; OECD, 2017[76]). In Southeast Asia, initiatives are underway to augment the resources of governments and households by encouraging employers to contribute funding through levies. With the decentralisation of education, there is also increased policy attention given to allocating resources more equitably. However, the use of levies and other employer incentives remains relatively limited in most of Southeast Asia, and inadequate technical and administrative capacities, especially at lower levels of governance, limit countries’ ability to track and evaluate how well allocation arrangements are working. Opportunity 4 describes how Southeast Asian countries can align and co‑ordinate financial arrangements (Table 1.11).

Table 1.11. Opportunity 4: Aligning and co‑ordinating financial arrangements

|

Policy directions |

High-level recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Diversifying financial resources |

3.13. Promote the use of levies among employers to encourage skills development and mobilise financial resources for training |

|

Allocating financial resources equitably and effectively |

3.14. Design a funding formula that allocates adequate financial resources to disadvantaged learners 3.15. Establish strong monitoring and evaluation systems to ensure the effectiveness of allocation arrangements. |

References

[16] ADB (2022), COVID-19 Pushed 4.7 Million More People in Southeast Asia Into Extreme Poverty in 2021, But Countries are Well Positioned to Bounce Back — ADB, https://www.adb.org/news/covid-19-pushed-4-7-million-more-people-southeast-asia-extreme-poverty-2021-countries-are-well.

[17] ADB (2022), Supporting Post-COVID-19 Economic Recovery in Southeast Asia, Asian Development Bank, Mandaluyong City, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/793526/post-covid19-economic-recovery-southeast-asia.pdf.

[58] ADB (2020), Asia Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Monitor 2020: Volume I - Country and Regional Reviews, Asian Development Bank, Mandaluyong City, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/646146/asia-sme-monitor-2020-volume-1.pdf.

[10] ADB (2017), A Region at Risk: The Human Dimensions of Climate Change in Asia and the Pacific, Asian Development Bank, Mandaluyong City, https://doi.org/10.22617/TCS178839-2.

[98] ADB (2015), Challenges and Opportunities for Skills Development in Asia: Changing Supply, Demand and Mismatches, Asian Development Bank, Mandaluyong City, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/176736/challenges-and-opportunities-skills-asia.pdf.

[72] AFD (2019), Financing TVET: A Comparative Analysis in Six Asian Countries, https://www.afd.fr/en/ressources/financing-tvet-comparative-analysis-six-asian-countries (accessed on 21 January 2022).

[27] ASEAN (2022), Promoting Decent Work and Protecting Informal Workers, ASEAN, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/The-ASEAN-Magazine-Issue-21-2022-Informal-Economy.pdf.

[89] ASEAN (2021), Consolidated Strategy on the Fourth Industrial Revolution for ASEAN, ASEAN, Jakarta, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/6.-Consolidated-Strategy-on-the-4IR-for-ASEAN.pdf.

[41] ASEAN (2021), Human Resources Development Readiness in ASEAN: Regional Report, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/TVET_HRD_readiness_ASEAN_regional_report_29-Apr-2021.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2022).

[85] ASEAN (2020), ASEAN Comprehensive Recovery Framework: Implementation Plan, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/ACRF-Implementation-Plan_Pub-2020.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2022).

[87] ASEAN (2020), ASEAN Declaration on Human Resources Development for the Changing World of Work and its Roadmap, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/ASEAN-Declaration-on-Human-Resources-Development-for-the-Changing-World-of-Work-and-Its-Roadmap.pdf.

[78] ASEAN (2020), Education: Overview, https://asean.org/our-communities/asean-socio-cultural-community/education/.

[88] ASEAN (2019), ASEAN Labour Ministers’ Statement on the Future of Work: Embracing Technology for Inclusive and Sustainable Growth, https://asean.org/asean2020/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/ASEAN-Labour-Ministers-Statement-on-the-Future-of-Work-Embracing-Techno....pdf.

[86] ASEAN (2017), ASEAN Consensus on the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Migrant Workers, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/ASEAN-Consensus-on-the-Protection-and-Promotion-of-the-Rights-of-Migrant-Workers1.pdf.

[90] ASEAN (2016), Vientiane Declaration on Transition from Informal Employment towards Decent Work Promotion in ASEAN and its Regional Action Plan, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Vientiane-Declaration-on-Employment.pdf.

[28] ASEAN Secretariat (2019), Regional Study on Informal Employment Statistics to Support Decent Work Promotion in ASEAN, ASEAN Secretariat, Jakarta, Indonesia, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Regional-Study-on-Informal-Employment-Statistics-to-Support-Decent-Work-Promotion-in-ASEAN.pdf.

[2] ASEAN Secretariat and UNCTAD (2019), ASEAN Investment Report 2019: FDI in Services: Focus on Health Care, ASEAN Secretariat, Jakarta, Indonesia.

[38] ASEAN University Network (2017), Joint Statement: 18th AUN and 7th ASEAN+3 Educational Forum “The Relevance of Higher Education in the Digital Era”, ASEAN University Network, https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Joint-Statement-on-the-18th-AUN-and-7th-ASEAN3-Educational-Forum-The-Relevance-of-Higher-Education-in-the-Digital-Era.pdf.

[93] Baker, B. (2017), How Money Matters for Schools, Learning Policy Institute, https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/sites/default/files/product-files/How_Money_Matters_REPORT.pdf.

[62] Bertelsmann Stiftung (2020), BTI Transformation Index, https://bti-project.org/en/index/governance (accessed on 20 December 2021).

[84] Cambodia MoEYS (2018), Education in Cambodia: Findings from Cambodia’s experience in PISA for Development, https://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisa-for-development/PISA-D%20national%20report%20for%20Cambodia.pdf.

[66] Chong, T. and S. Elies (eds.) (2011), An ASEAN Community for All: Exploring the Scope for Civil Society Engagement, https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/singapur/08744.pdf.

[100] Christensen, T. and P. Lægreid (2007), “The whole-of-government approach to public sector reform”, Public Administration Review, Vol. 67/6, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2007.00797.x.

[37] CISCO and Oxford Economics (2018), Technology and the future of ASEAN jobs: The impact of AI on workers in ASEAN’s six largest economics, CISCO, https://www.cisco.com/c/dam/global/en_sg/assets/csr/pdf/technology-and-the-future-of-asean-jobs.pdf.

[61] Cornell University, INSEAD and World Intellectual Property Organization (2020), Global Innovation Index 2020: Who Will Finance Innovation?, https://www.wipo.int/edocs/pubdocs/en/wipo_pub_gii_2020.pdf.

[39] Cunningham, W. et al. (2022), “The Demand for Digital and Complementary Skills in Southeast Asia”, Policy Research Working Paper, No. 10070, World Bank Group, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/37503/IDU015d114c30628f046a20a644099df1ade479f.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

[21] Eurofound and ILO (2017), Working Anytime, Anywhere: The Effects on the World of Work, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, and the International Labour Office, Geneva, https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/sites/default/files/ef_publication/field_ef_document/ef1658en.pdf.

[48] Eurostat (2022), Participation of young people in education and the labour market, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Participation_of_young_people_in_education_and_the_labour_market.

[101] Fazekas, M. (2012), “School Funding Formulas: Review of Main Characteristics and Impacts”, OECD Education Working Papers, No. 74, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5k993xw27cd3-en.

[47] Gentile, E. (ed.) (2019), Skilled Labor Mobility and Migration, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, UK, https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788116176.

[3] Google, Temasek and Bain & Company (2021), Roaring 20s: The SEA Digital Decade, https://www.bain.com/globalassets/noindex/2021/e_conomy_sea_2021_report.pdf (accessed on 23 January 2023).

[83] ILO (2020), A Review of Skills Levy Systems in Countries of the Southern African Development Community, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---emp_ent/documents/publication/wcms_753306.pdf.

[56] ILO (2020), Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020: Technology and the future of jobs, International Labour Organization, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_737648.pdf.

[52] ILO (2019), ASEAN course on the transition from informal to formal economy: ASEAN countries, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_676140.pdf.

[51] ILO (2019), Extension of Social Security to Workers in Informal Employment in the ASEAN Region, ILO, Thailand, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_735512.pdf.

[13] ILO (2019), Skills for a Greener Future: A Global View based on 32 Country Studies, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/documents/publication/wcms_732214.pdf.

[57] ILO (2019), Youth Transitions and Lifetime Trajectory, ILO, Geneva, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_emp/---ifp_skills/documents/publication/wcms_734499.pdf.

[11] ILO (2017), Addressing the impact of climate change on labour, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---relconf/documents/meetingdocument/wcms_543701.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2019).

[81] ILO (2016), Managing Labour Mobility: Opportunities and Challenges for Employers in the ASEAN Region, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---asia/---ro-bangkok/---sro-bangkok/documents/publication/wcms_464049.pdf.