Strong governance arrangements are needed to ensure Southeast Asian countries can respond to existing challenges in their skills systems and adapt to labour market changes brought about by megatrends and COVID‑19. This chapter assesses the effectiveness of skills governance in Southeast Asia and explores four opportunities to improve skills policies: 1) promoting a whole-of-government approach; 2) promoting a whole-of-society approach; 3) building integrated information systems; and 4) aligning and co‑ordinating financial arrangements. The chapter looks at general trends within countries in Southeast Asia, which may have an impact on the above governance components and identifies and showcases good practices, which introduce what has worked to strengthen the relationships of the diverse actors in Southeast Asian skills systems.

OECD Skills Strategy Southeast Asia

5. Strengthening the governance of skills systems in Southeast Asia

Abstract

The importance of strengthening the governance of skills systems

Effective skills governance systems are crucial to ensuring that Southeast Asia can implement the skills policies needed to adapt to megatrends and recover from the coronavirus (COVID‑19) pandemic. Skills governance, defined as the process of decision making and the implementation of skills-related policy interventions (OECD, 2007[1]), aims to improve skills systems by ensuring that skills supply responds effectively to the needs of the labour market and society and promoting greater demand for the use of higher-level skills in the workplace, at home and in communities. This is done through the establishment of inclusive policies and institutions required to take rapid action, counteract the adverse effects of megatrends, and build countries’ and individuals’ resilience to shocks and disruptions, such as those of COVID‑19.

Skills governance involves the contribution of a wide range of actors who work collaboratively to strengthen the skills system. Skills systems consist of the institutions, actors and policies, laws or regulations concerned with the development and use of skills (OECD, 2020[2]), as well as the actors who manage or are affected by them, such as governments, employers, workers, civil society representatives and individuals. Actors in the skills system undertake various activities related to developing and using skills, managing resources (e.g. financial, human, data) and taking decisions related to the supply and demand sides of the skills system. When working collaboratively, these actors' influence increases and they become empowered to link separate components of skills systems and work towards improved skills outcomes for the benefit of all. Effective skills governance allows relevant actors to identify and leverage their strengths, skills, knowledge and networks and use them to complement others to achieve shared policy objectives. As a result, inclusive skills systems are built through the involvement of a wide variety of actors in decision making, fostering buy-in and ownership across the entire skills system and allowing skills policies to contribute to broader socio-economic and societal development objectives (OECD, 2021[3]).

At the regional level, Southeast Asia has established regional skills governance bodies in recognition of their importance in implementing effective skills policies. To name a couple, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) Council is responsible for the overall co‑ordination, research and development and monitoring of regional education programmes to support TVET (RECOTVET, 2020[4]). In addition, the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization (SEAMEO) and its centres bring together ministries of education to promote regional co‑operation in education, science and culture (SEAMEO, 2021[5]). These bodies allow countries in the region to exchange good practices, co‑ordinate policy implementation at the regional level and improve their respective skills systems. The above-mentioned bodies also engage stakeholders, which contribute funding and mobilise other resources. For example, SEAMEO’s centres are funded through different channels, including contributions from all member countries. Furthermore, during the COVID‑19 pandemic, such bodies were instrumental in ensuring skills systems' resilience by facilitating discussions on timely solutions and adaptation measures.

However, across Southeast Asian countries, several governance challenges remain. These include: 1) modest horizontal co-ordination arrangements and weak linkages between national and subnational levels of government; 2) low levels of collective bargaining and insufficient engagement of civil society actors, especially of disadvantaged groups; 3) limited capacity and infrastructure to integrate skills data from different sources and use them to inform skills policies; and 4) inadequate diversification of funding arrangements. To overcome these challenges, the OECD project team (OECD, 2019[6]) has identified four building blocks that aim to support effective skills governance systems in Southeast Asia:

A whole-of-government approach, which involves horizontal co‑ordination across ministries and vertical co‑ordination between national and subnational governments. Engagement across government can vary from ad hoc governance bodies to more formal arrangements, such as skills councils at the national or subnational levels.

A whole-of-society approach, which refers to engagement with actors outside of government and reflecting their needs and interests in skills policies. These actors include actors in education (e.g. teachers) and in the labour market sectors (e.g. employers, chambers of commerce, trade unions), as well as relevant civil society actors (e.g. non-governmental organisations [NGOs]). Engagement can range from opportunities for these actors to voice their concerns through stakeholder consultations or collective bargaining to their full inclusion in formal governance bodies.

Integrated information systems, which refer to mechanisms that link various data sources to inform and support the development and implementation of skills policies. This includes co‑ordination among various data collection entities and the standardisation of indicators, which help governance bodies identify current and possible future skills needs and promote sound planning of interventions and career guidance.

Aligned and co‑ordinated financial arrangements, which refers to the strategic co‑ordination and use of limited financial resources coming from various sources to maximise value. It includes the assessment of financial needs, the identification of adequate and sustainable financial arrangements for skills policy implementation, the diversification of funding sources and the matching of funding needs.

Given these challenges, this chapter aims to suggest future directions for Southeast Asia’s skills governance based on an analysis of the current performance of the region. It starts with an overview of the current governance arrangements to implement skills policies and an assessment of Southeast Asian countries’ performance on key indicators. Building on this assessment, the chapter then presents four opportunities for the region to strengthen the governance of skills systems in Southeast Asia: 1) promoting a whole-of-government approach; 2) promoting a whole-of-society approach; 3) building integrated information systems; and 4) aligning and co‑ordinating financial arrangements. Each opportunity addresses the region's current challenges and proposes concrete, evidence-based policy recommendations.

Summary of recommendations

The policy recommendations presented throughout this chapter are summarised as follows.

Summary of policy recommendations for Southeast Asia for the governance of its skills systems

Opportunity 1: Promoting a whole-of-government approach

Strengthening horizontal co‑ordination

3.1. Support skills-related inter-ministerial governance bodies in their engagement of all relevant ministries

3.2. Promote a shared skills goal among relevant ministries through strategic documents, such as national development plans and skills-related policy documents

Strengthening vertical co‑ordination

3.3. Support subnational governments in implementing skills policies by providing additional human and financial resources and capacity-building support

Opportunity 2: Promoting a whole-of-society approach

Identifying and engaging relevant labour market actors

3.4. Establish legal frameworks to strengthen engagement with actors in the labour market

3.5. Strengthen the effectiveness of governance bodies engaging labour market actors

Identifying and engaging relevant civil society actors

3.6. Provide financial, technical, and networking resources to facilitate the participation of women, as well as the organisations that represent them, in governance

3.7. Strengthen youth’s input in official governance bodies and development of youth strategies

3.8. Support migrant organisations’ active participation in governance bodies and influence in skills policies

Opportunity 3: Building integrated information systems

Improving data collection

3.9. Implement robust national data collection processes to address data gaps

3.10. Support participation in international surveys to generate internationally comparable data

Improving the management and use of skills data

3.11. Establish the institutional and legal groundwork for integrating data management systems

3.12. Regularly conduct skills assessment and anticipation exercises to design and updates skills policies

Opportunity 4: Aligning and co‑ordinating financial arrangements

Diversifying financial resources

3.13. Promote the use of levies among employers to encourage skills development and mobilise financial resources for training

Allocating financial resources equitably and effectively

3.14. Design a funding formula that allocates adequate financial resources to disadvantaged learners

3.15. Establish strong monitoring and evaluation systems to ensure the effectiveness of allocation arrangements

Overview and performance of Southeast Asia’s governance of skills systems

Promoting a whole-of-government approach

Given that skills encompass a wide variety of policy domains, a whole-of-government approach is an integral part of the governance of skills systems. A whole-of-government approach refers to the capacity of various government entities to work together at the national and subnational levels and take advantage of the multiple perspectives, mandates and capabilities of different institutions. The approach aims to improve the government's horizontal and vertical co‑ordination, with the overall objective of enhancing coherence in the implementation of skills policies, promoting synergies and improving resource efficiency. A whole-of-government approach should result in increased integration, improved co‑ordination and enhanced capacities to develop and implement skills policy (OECD, 2011[7]; Christensen and Lægreid, 2007[8]).

The mandate for skills policies is spread across multiple ministries in Southeast Asia, highlighting the importance of effective horizontal co‑ordination

Skills systems are characterised by the involvement of multiple national actors in the development and implementation of skills policies. Horizontal co‑ordination includes ministries, departments or agencies at the national level, which are mandated to undertake skills-related functions. The mandate for overseeing skills policies in Southeast Asia falls mainly under the ministries of education and labour. However, other ministries also have related functions, including ministries in charge of affairs related to the economy, industry, innovation, migration, social affairs, culture, sports, agriculture and tourism, as well as specialised national agencies (OECD, 2019[6]). In this sense, horizontal co‑ordination promotes coherence in the development and implementation of skills policies and strategies, promotes shared responsibility for decisions and outcomes and fosters a shared commitment to take action (Ferguson, 2009[9]).

However, horizontal co‑ordination becomes challenging as the number of national-level actors involved increases. Countries in Southeast Asia usually have diverse ministries with a mandate for skills policies. For example, ministries of education are primarily responsible for overseeing initial and higher education.1 At the same time, ministries of labour are responsible for managing employment issues and industrial relations, promoting employment, designing, implementing and funding skills-related policies, and collecting information on workers and their rights, including for migrant workers. In some cases, labour ministries are also directly involved in training provision, especially TVET. Ministries of economy, industry and innovation implement skills policies that raise the demand for higher-level skills. Ministries that oversee social affairs, culture and sports are responsible for promoting policies that encourage skills use in everyday life, such as civic engagement and leisure activities. Other ministries, such as those responsible for tourism and agriculture, also offer specialised training to develop skills for their respective sectors. Furthermore, some countries have established oversight bodies that actively co‑ordinate the skills or TVET-related activities organised by different actors. A selection of various institutions responsible for implementing elements of skills policies in Southeast Asia is provided in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1. Main national-level skills government institutions in Southeast Asian countries

|

Country |

Ministry/agency responsibilities for implementing elements of skills policies |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ministry of Education (or equivalent) |

Ministry of Labour (or equivalent) |

Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Innovation (or equivalent) |

Ministry of Social Affairs, Culture and Sports (or equivalent) |

Ministry of Agriculture |

Ministry of Tourism |

Other ministry* |

Specialised agency for skills (e.g. TVET) |

|

|

Brunei Darussalam |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|||

|

Cambodia |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

Indonesia |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Malaysia |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|||

|

Myanmar |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

|

Philippines |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

||

|

Singapore |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

||||

|

Thailand |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|||

|

Viet Nam |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Note: Reference to the ministries’ responsibilities on different items of the skills agenda was collected through visits to the official websites and references to their work. The table is not exhaustive; rather, it intends to indicate the type of ministries involved. Other ministries may also be involved in the respective countries; however, the information may not have been publicly available during the drafting of this report.

*Other ministries for: Indonesia - Ministry for Economic Affairs; Myanmar – Ministry of Science and Technology (Department of Technical and Vocational Education and Training); Singapore – Ministry of Health (Ageing Planning Office).

Southeast Asian countries vary considerably in terms of effectiveness of vertical co‑ordination for skills policies

Vertical co‑ordination enables a close interaction across levels of government and is crucial to ensure that national policy decisions reflect needs at the subnational level. Vertical co‑ordination refers to the level of engagement between the national and subnational governments. It allows the latter to participate actively in policy decision making. Furthermore, it aims to make policy development more responsive to subnational needs. Vertical co‑ordination offers several advantages. These include boosting knowledge sharing, broadening the scope of skills data collection, improving skills budget use efficiency; reducing disparities in participation (by individuals) in skills development and use across subnational levels; and stimulating skills interventions based on actual needs (OECD, 2021[10]). Vertical co‑ordination ranges from dialogue and ad hoc consultations with subnational levels to inclusion in formal governance bodies. Occasionally, it may entail the entire delegation of responsibilities of the national government to subnational governments through decentralisation (Gløersen and Michelet, 2014[11]).

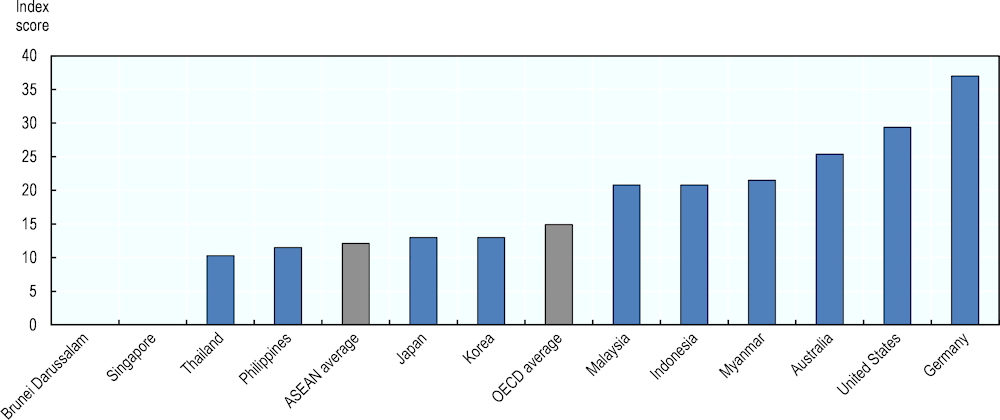

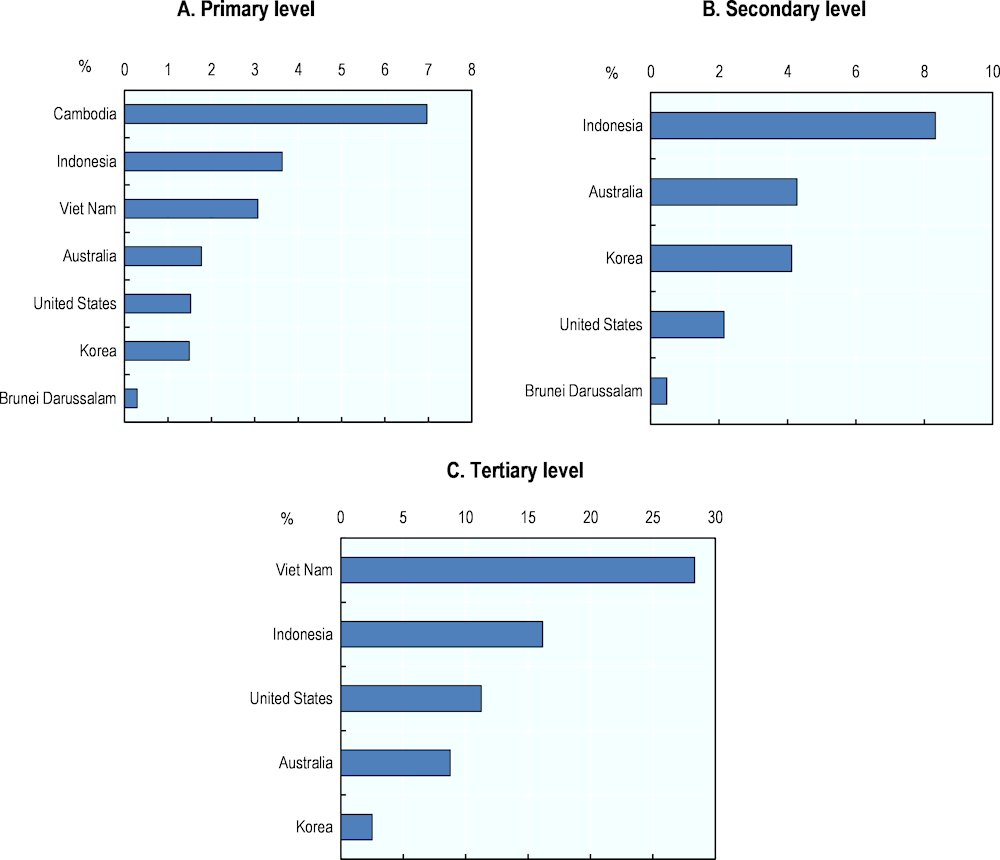

Southeast Asian governments vary considerably in terms of the extent to which regional governments exercise authority for skills policy. Figure 5.1 presents the extent to which different government levels exert authority in policy decision making (Hooghe et al., 2016[12]). The index ranges between 0 and 38, with the higher numbers indicating higher levels of decentralisation and greater authority delegated to regional government structures. While the averages for ASEAN countries (12.1) and OECD countries (14.9) do not differ significantly, considerable differences can be observed among Southeast Asian countries. For example, Myanmar (21.5), Malaysia (20.8) and Indonesia (20.8) are countries where decision-making authority is relatively more decentralised, thus showing more regional authority. At the same time, according to the index, Singapore (0), Brunei Darussalam (0), Thailand (10.3) and the Philippines (11.5) are below the ASEAN average. Therefore, it is assumed that their systems are highly centralised.

Figure 5.1. Regional Authority Index, Southeast Asian countries and selected OECD countries, latest available year

Note: The Regional Authority Index measures the extent to which regional governments can exercise authority (i.e. legitimate, recognised and accepted right to power) in various areas of governance, including taxation, borrowing, national legislation and constitutional reform, on a scale from 0 to 38. All data are from 2010 except for Japan and the United States (2016).

Source: Hooghe et al. (2016[12]), Measuring Regional Authority: A Post-functionalist Theory of Governance, Volume I, https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198728870.001.0001.

Promoting a whole-of-society approach

While horizontal and vertical co‑ordination arrangements are necessary among ministries and across levels of government, it is equally important to engage actors outside of government. A whole-of-society approach includes the participation of a wide range of non-governmental actors in policy making. These include employers, workers and civil society representatives, educational institutions and training providers, among others. Employers refer to the actors who can engage other individuals to work with them as employees (OECD, 2002[13]), while workers are all those involved in paid employment (OECD, 2003[14]). Civil society refers to all individuals or organisations of individuals linked by similar interests or pursuing common objectives through partnerships with other individuals for non-commercial reasons. The involvement of these actors in the skills agenda provides a broader perspective on the skills system and valuable, up-to-date information regarding current and evolving skills needs. Promoting a whole-of-society approach requires establishing effective engagement mechanisms and creating avenues for the political participation and inclusion of under-represented groups at all policy decision-making levels.

Southeast Asian countries could do more to improve engagement with relevant labour market actors for skills policies

Co‑ordination mechanisms engaging employers and workers can assist in more closely aligning educational and training goals and outcomes with the needs of the labour market. Employers play a key role in skills governance (ILO, 2020[15]), as they possess valuable information and resources – financial, human, and technological – to support and contribute to the development and use of skills. Similarly, workers are well positioned to understand challenges and opportunities in developing and using skills, the skills that workers need for success, and why certain individuals either do not avail themselves of or abandon training and employment opportunities. A variety of co‑ordination mechanisms exist for governments to engage employers and workers (e.g. public-private partnerships, councils, co-funding arrangements) and for employers and workers to engage with one another (e.g. collective bargaining mechanisms) (OECD, 2019[6]).

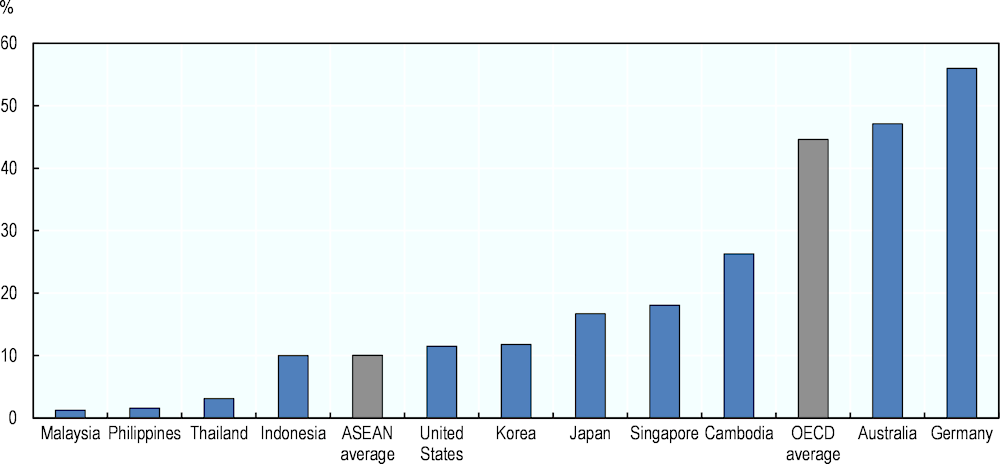

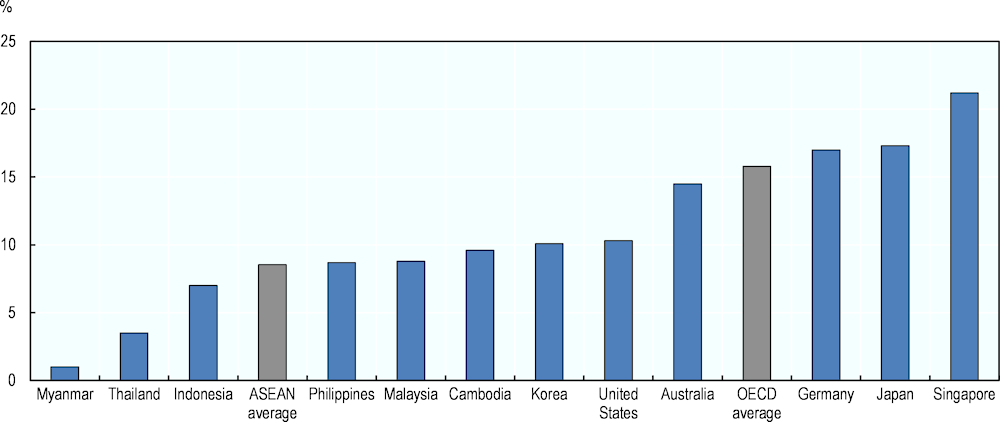

Establishing effective collective bargaining mechanisms is crucial to fostering the socio-political environment that allows workers and employers to participate in skills policy making. Collective bargaining refers to the engagement mechanisms through which trade unions come together to establish agreements with employers regarding their terms of employment (ILO, 2022[16]). The ASEAN average collective bargaining coverage rate stands at 10.1% (for those countries with available data). As shown in Figure 5.2, collective bargaining agreements are virtually absent in Malaysia and the Philippines, where less than 2% of the workforce is covered. In comparison, in Cambodia, one in four (26.3%) employees’ conditions of employment are determined by collective agreements. The OECD collective bargaining rate average is 44.6%, with significant differences between countries. For example, in Germany, a country with a governance system wherein social dialogue has traditionally played a central role, 56% of employees have working conditions or wages determined by at least one collective bargaining agreement. In comparison, the United States stands just above the ASEAN average, with 11.5% of workers represented.

More could be done to improve the participation of civil society in skills policies in Southeast Asia

The engagement of civil society actors is crucial to improving governance at all levels, ensuring that skills policies are adapted to the needs of the most vulnerable and secure the full use of skills for life and work. Organised civil society actors, such as NGOs, are likely to have closer contact than governments with local community leaders and other local actors. Therefore, they can facilitate negotiations at the local level and support the implementation of skills reforms. Moreover, civil society actors are knowledgeable about their local context and aware of the needs of various vulnerable groups. As such, their engagement is crucial to ensure that the needs of vulnerable groups are reflected in policy making and that the skills development policies are not only demand-driven but also inclusive (ADB, 2021[17]). Furthermore, organised civil society actors often promote employment and entrepreneurship through targeted programmes and support individuals in coping with specific challenges. Therefore, they are strategically positioned to support skills use for life and work. Finally, many of the organised civil society actors in Southeast Asia have a regional or international perspective. They are, therefore, capable of supporting cross-country knowledge sharing and ASEAN-wide initiatives (Makito, 1999[18]).

Figure 5.2. Collective bargaining coverage rates in Southeast Asian countries and selected OECD countries, 2016

Note: The collective bargaining coverage rate measures the number of employees whose wages and/or conditions of employment are determined by one or more collective agreement(s) as a percentage of the total number of employees. Due to a lack of data, the latest available year was used for the following countries: Indonesia (2008), Cambodia and Singapore (2012), and Korea (2015).

Source: World Bank (2019[19]), Freedom of association and assembly, https://govdata360.worldbank.org/indicators/h73d52fde; ILOSTAT (2020[20]), Statistics on collective bargaining, https://ilostat.ilo.org/topics/collective-bargaining/.

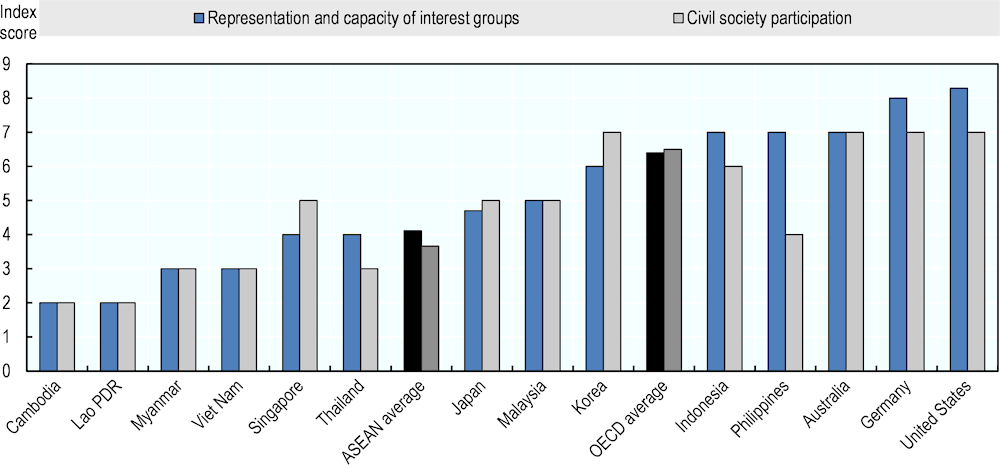

Despite the importance of their engagement, more could be done to facilitate the inclusion of civil society actors in Southeast Asian countries. Figure 5.3 shows the extent to which representative and competent civil society groups exist in the region, as well as the level at which these groups participate in the formulation of policies and in the political process. On a scale of 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest), Southeast Asia scores an average of 4.1 in the representation and capacity of interest groups, which is lower than the OECD average of 6.4. Similarly, the region rates only 3.7 in civil society participation, which is lower than the OECD average of 6.5, indicating significant room for improvement. Civil society capacity and participation are highest in Indonesia (7 in representation and capacity of interest groups, 6 in civil society participation) and the lowest in Cambodia and the Lao People’s Democratic Republic (hereafter “Lao PDR”) (2 for both indicators).

Figure 5.3. Civil society capacity and participation in policy formulation in Southeast Asian countries and selected OECD countries, 2022

Note: “Representation and capacity of interest groups” refers to the extent to which a network of co‑operative and competent interest groups exists to mediate between segments of civil society and government, while “civil society participation” refers to the extent to which political leadership involves civil society actors in agenda setting, decision making, policy development and implementation, and performance monitoring. Equivalent data for OECD countries were taken from the Sustainable Governance Indicators Database, using the indicators “parties and interest associations”, which measures the extent to which non-economic associations are capable of representing segments of civil society, and “societal consultation”, which refers to the extent to which government consults with economic and social actors in the course of policy preparation.

Source: Bertelsmann Stiftung (2022[21]), BTI Transformation Index, https://bti-project.org/en/index/political-transformation; Bertelsmann Stiftung (2022[22]), Sustainable Governance Indicators, www.sgi-network.org/2022/.

Building integrated information systems

Integrated information systems facilitate decision-making processes by making the necessary data available to draw findings on skills issues. Therefore, building integrated information systems is an essential building block for skills governance. In Southeast Asia, different actors currently collect, process and disseminate data, making data management processes very complex. Having various data sources may also hinder the utilisation of data, as, without integration, any single data source is incomplete and thus has only limited use. For instance, incomplete data from the supply side alone cannot inform career guidance and counselling services. Similarly, demand-side data alone cannot inform skills forecast exercises. Data are only valuable when they can be used effectively, highlighting the importance of establishing the right environment to make information accessible to all.

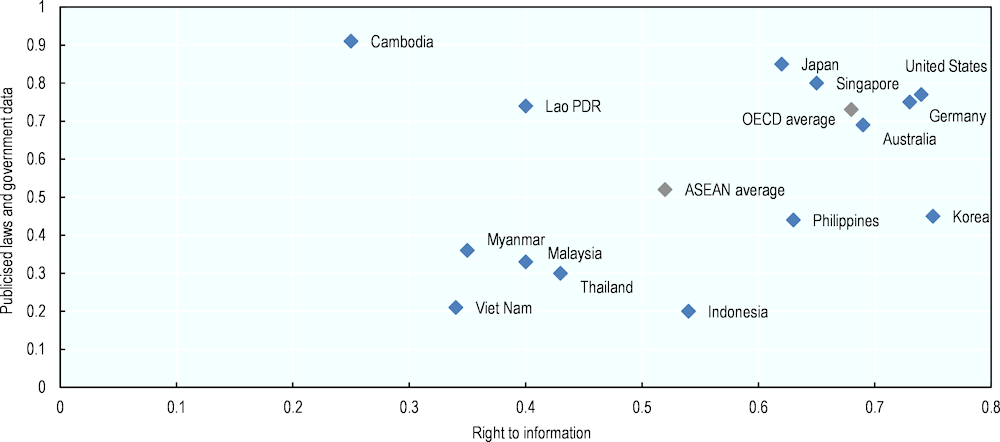

Southeast Asian countries vary in the extent that they guarantee the right to information and make laws and government data publicly available. Southeast Asian countries like Viet Nam, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and Myanmar have relatively fewer measures that guarantee the right to information and make laws and government data publicly available. In contrast, like other OECD countries, Singapore has relatively more measures that ensure the right to information (Figure 5.4). Accessibility of skills information could be enhanced through a formal body responsible for managing and disseminating this type of information. The importance of the availability, dissemination and use of high-quality skills information was underscored during the COVID‑19 pandemic, as policy makers, employers and individuals struggled to make informed skills-related decisions.

Figure 5.4. Availability and accessibility of information: Right to information vs. publicised laws and government data in Southeast Asian countries and selected OECD countries, 2020

Source: World Justice Project (2021[23]), Open Government Indicators, www.worldjusticeproject.org/rule-of-law-index/factors/2021/Open%20Government.

Aligning and co‑ordinating financial arrangements

Robust financial arrangements are an essential factor in the sustainability of governance mechanisms and a determinant of the success of skills interventions. Innovative financing mechanisms provide financial resources from different sources, creating an enabling environment for skills systems to plan essential long-term interventions. Moreover, they allow systems to adapt and act rapidly towards tackling the possible adverse effects of labour market megatrends and other disruptive shocks, such as the COVID‑19 pandemic. Furthermore, diversified financial arrangements provide increasing resources to skills systems and make a more comprehensive set of actors responsible for the results of skills development and use interventions, promoting joint decision making, which is expected to lead to increased quality.

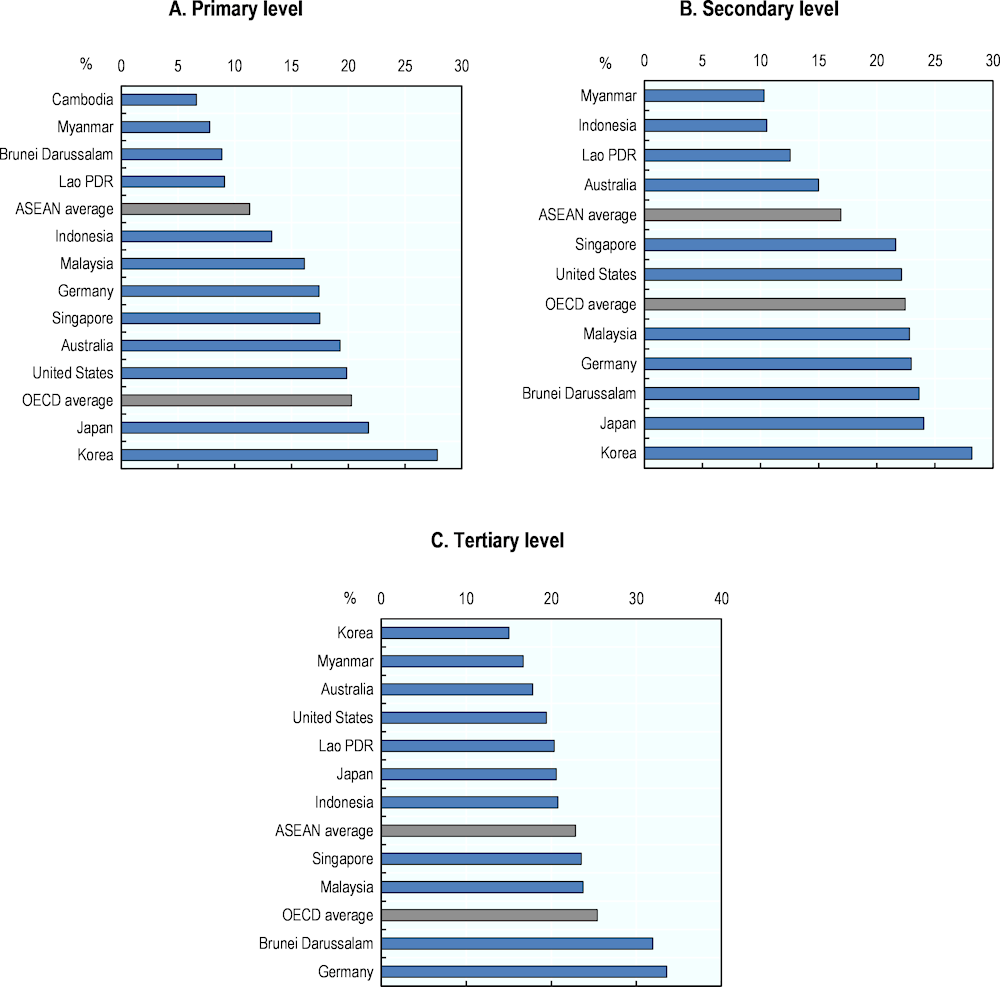

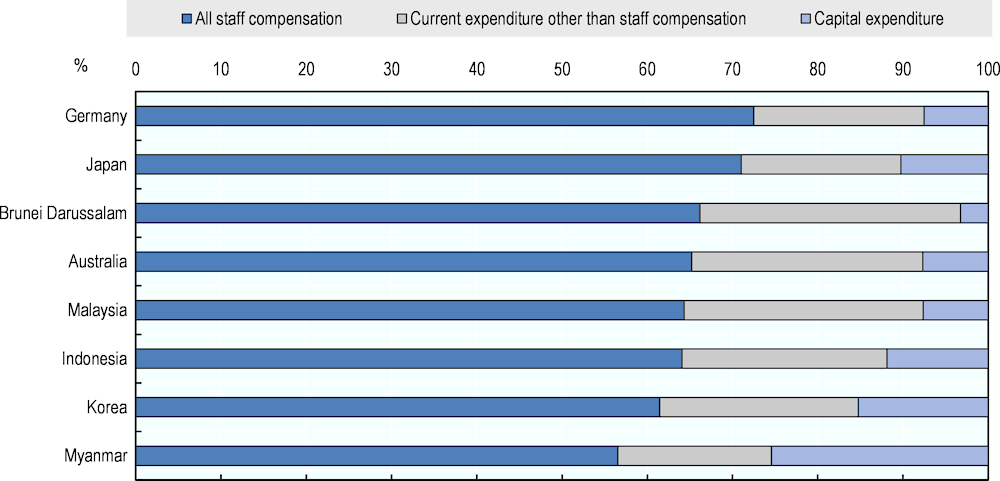

Regardless of the above, skills development systems in Southeast Asia continue to be mainly financed through household and government contributions, relying heavily on government funding. Figure 5.5 depicts the government expenditure per student (expressed as a percentage of gross domestic product [GDP] per capita, which is among the measures to track the progress of Sustainable Development Goal [SDG] target 4.5.4) across Southeast Asia and OECD countries. A higher indicator value indicates a greater priority to the specific level of education given by public authorities. Across both OECD and Southeast Asia countries, higher levels of education are associated with higher spending per student (per capita terms). Lower spending at earlier stages of education makes it less likely for young learners to develop a strong skills foundation, which then limits their ability to acquire higher-level skills at later stages of education, such as at the tertiary level (OECD, 2017[24]). At all levels, average Southeast Asian government expenditure is below that of OECD countries. For pupils in primary education, countries in Southeast Asia spend 11.3% of GDP per capita on average compared to 20.3% in OECD countries. The spending gap between countries in Southeast Asia and the OECD narrows though for secondary and tertiary levels of education. For instance, Southeast Asia countries are spending 22.8% of GDP per capita for each student in tertiary education, compared to 25.4% in OECD countries. As discussed in Chapter 3, the number of students decreases by the level of education across countries. This is, in particular, the case for countries in Southeast Asia, which tend to spend an increasing amount of public resources on a relatively small (tertiary) student population.

Figure 5.5. Government expenditure on education per student in Southeast Asian countries and selected OECD countries, latest available year

Note: Government expenditure on education per student refers to the average general government expenditure (current, capital and transfers) per student, expressed as a percentage of GDP per capita. Data include the latest year available for each country at each level of education.

Source: World Bank (2021[25]), World Development Indicators, https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators.

Opportunities to strengthen the governance of skills systems

Improving the governance of skills systems is essential to ensuring that skills policies are implemented effectively. Moreover, effective implementation is key to guaranteeing that all actors benefit equally from skills policies and that they can sustain the full development and use of their skills over the life course. Based on an assessment of the performance of countries in Southeast Asia, the following opportunities have been identified for strengthening the governance of its skills systems:

1. promoting a whole-of-government approach

2. promoting a whole-of-society approach

3. building integrated information systems

4. aligning and co ordinating financial arrangements.

Opportunity 1: Promoting a whole-of-government approach

Skills policies require a whole-of-government approach. Developing and implementing skills policies rarely depend on a single ministry or level of government. Instead, they often involve multiple governmental actors with responsibilities for, and interests in, skills outcomes. A whole-of-government approach is needed to promote horizontal co‑ordination among relevant ministries and vertical co‑ordination across levels of government, including regional and local. Such an approach aims to bring different ministries and levels of government together to facilitate their collaboration and foster policy coherence (OECD, 2019[6]).

There are various horizontal and vertical mechanisms to facilitate a whole-of-government approach to skills policies. In all mechanisms, it is important to ensure that all units of government have a common understanding of the skills agenda and its goals and are committed to providing the necessary financial and human resources to facilitate the implementation of skills policies. Opportunity 1 presents two policy directions for promoting a whole-of-government approach. First, it explores how to promote horizontal co‑ordination across ministries by establishing oversight agencies, inter-ministerial bodies, and sectoral bodies. Second, it discusses how to strengthen vertical co‑ordination across levels of government, such as by implementing vertical mechanisms that bring together national and subnational levels of government in the form of formal bodies, working groups and ad hoc meetings.

Strengthening horizontal co‑ordination

Horizontal co‑ordination, which fosters collaboration among relevant ministries and other national-level actors on skills policies, improves skills systems in several ways. First, they enhance the coherence of the skills agenda across the whole of government, establishing close linkages between national development plans, economic, industrial, and sectoral growth strategies and skills policies and strategies (ADB, 2015[26]). Second, horizontal co‑ordination improves the overall resilience of skills systems by enabling a more efficient and rapid response to tackle shocks, such as the COVID‑19 pandemic, facilitating strategic and timely decision making and designing targeted skills activities (ILO, 2020[27]). Third, horizontal co‑ordination also promotes other activities required for an efficient skills system, such as improved data collection, management, and dissemination (see Opportunity 3) and the sustainable financing of skills (see Opportunity 4) (OECD, 2019[6]; 2020[2]). In line with these many benefits, this policy direction explores two areas where horizontal co‑ordination could be strengthened in Southeast Asia’s skills systems: 1) establishing inter-ministerial oversight bodies; and 2) developing a shared skills goal across ministries.

Strengthening horizontal co‑ordination through inter-ministerial oversight bodies

Inter-ministerial oversight bodies have shown positive results in promoting coherent implementation of skills policies in some Southeast Asian countries. An inter-ministerial oversight body is an independent entity that co‑ordinates skills-related policies across policy domains. Among the activities of different inter‑ministerial oversight bodies is the co‑ordination of actors involved in skills development and use, data collection, skills-related research, knowledge sharing, and monitoring and evaluation of skills policies. Often acting with a certain degree of independence, inter-ministerial oversight bodies are typically governed by inter-ministerial boards and bring together national and subnational government representatives. The strategic advantage of inter-ministerial oversight bodies is found in their expertise. By focusing their activities on specific components of skills development and use, oversight bodies can support the implementation of long-term strategies with sustainable results. Countries in Southeast Asia with established oversight agencies include Malaysia (Department of Skills Development, DSD), Myanmar (National Skills Standards Authority, NSSA), the Philippines (Technical Education and Skills Development Authority, TESDA), and Viet Nam (Department for Vocational Education and Training, DVET) (Table 5.2). Inter-ministerial oversight bodies may be created ad hoc to respond to disruptive and pressing issues affecting skills policies. For example, Australia’s Industry and Skills Committee (AISC) Emergency Response Sub-Committee was expressly set up to tackle the challenges of the COVID‑19 pandemic (Box 5.1).

Table 5.2. Examples of skills-related inter-ministerial oversight bodies in Southeast Asian countries

|

Country |

Inter-ministerial bodies |

Mandate |

Ministries involved |

Other members |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Brunei Darussalam |

Manpower Planning and Employment Council |

To address unemployment-related issues effectively and efficiently |

|

|

|

|

Cambodia |

National Training Board |

To co‑ordinate a long-term development plan for TVET and orient the TVET system towards the socio-economic needs of the country |

|

|

|

|

Indonesia |

Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs |

To plan and co‑ordinate economic policies, including manpower development |

|

|

|

|

Lao PDR |

National Training Council |

To function as an advisory body regarding the development of skills plans and policies |

|

|

|

|

Malaysia |

Council of the Department of Skills Development |

To manage and co‑ordinate training offers for Malaysian citizens and promote career development in all sectors |

|

|

|

|

Myanmar |

Board of the National Skills Standards Authority |

To support labour-market-relevant skills development opportunities and improve the quality of the skills development programmes (e.g. through the development of skills assessment criteria and a certification system) |

|

|

|

|

Philippines |

Philippine Qualifications Framework – National Coordinating Council |

To harmonise qualification levels across initial education, TVET and tertiary education, in line with the Philippines Qualifications Framework, as well as to improve quality assurance mechanisms throughout the skills system |

|

|

|

|

The Philippine Skills Framework Initiative |

To co‑ordinate inter-agency efforts to improve the skills of the Philippine workforce through the development of sector-specific skills frameworks |

|

|||

|

Singapore |

SkillsFuture Singapore |

To drive and coordinate the implementation of the national SkillsFuture movement, promote a culture and system of lifelong learning through the pursuit of skills mastery, and strengthen the ecosystem of quality education and training in Singapore |

|

|

|

|

Future Economy Council |

To develop and implement new strategies for 23 strategic industries |

|

|

||

|

Thailand |

Committee of Thailand’s Equitable Education Fund |

To provide financial support to disadvantaged children and youth and reduce educational inequalities |

|

||

Source: APEC (2021[28]), APEC Economic Policy Report 2021: Structural Reform and the Future of Work, www.apec.org/docs/default-source/publications/2021/11/2021-aepr/2021-aepr---annex-a_individual-economy-reports.pdf?sfvrsn=b601ebf_4; Brunei Darussalam, Manpower Industry Steering Committee (MISC) Working Group for Energy (2023[29]), About Us, https://miscenergy.com/about/; National Training Board (2008[30]), National Training Board Profile and History, www.ntb.gov.kh/profile.htm; UNESCO International Centre for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (2020[31]), TVET Country Profile: Lao People's Democratic Republic, https://unevoc.unesco.org/home/Dynamic+TVET+Country+Profiles/country=LAO; Malaysia Department of Skills Development (2020[32]), Department Profile, www.dsd.gov.my/index.php/profil-jabatan/latar-belakang; Myanmar National Skills Standards Authority (2021[33]), NSSA Organizational Structure, www.nssa.gov.mm/en/about-us/organizational-structure; Philippine Business for Education (2020[34]), A Future That Works: Where We Are So Far, www.pbed.ph/projects/13/A%20Future%20That%20Works; Philippine Department of Trade and Industry (2021[35]), DTI leads launching of national skills upgrading initiative, www.dti.gov.ph/archives/news-archives/national-skills-upgrading-launching/; Singapore Ministry of Trade and Industry (2020[36]), The Future Economy Council, www.mti.gov.sg/FutureEconomy/TheFutureEconomyCouncil; SkillsFuture (2016[37]), Homepage, https://www.skillsfuture.gov.sg/; Workforce Singapore Agency (2016[38]), About Workforce Singapore, www.ssg-wsg.gov.sg/about.html?activeAcc=7; Thailand Department of Skill Development (2014[39]), About the Department: Vision/Mission, www.dsd.go.th/DSD/Home/Vision.

While governance bodies, such as inter-ministerial oversight bodies, are essential to facilitating horizontal co‑ordination, it matters how they are established. Having unnecessary multiple bodies with the same or similar mandates and engaging many of the same actors across bodies would be counterproductive and ineffective. When the responsibilities and membership of these bodies overlap, this can impede co‑ordination by overloading members' agendas; creating confusion about objectives, roles and responsibilities; and reducing efficiency. Thus, the mandates, scope and composition of bodies should be clarified and co‑ordinated relative to each other through, for example, creating clear terms of reference specifying the roles and responsibilities of each body. These terms should be based on the specific body’s mandate, capacity and expertise (Charbit and Michalun, 2009[40]).

Furthermore, the effectiveness of governance bodies depends on the active participation of its members and available financial and human resources. While the active participation of members is critical for governance bodies to co‑ordinate effectively, common constraints include lack of time and availability to meet. This constraint is particularly challenging when the members include senior government officials from different ministries and require their presence to convene. A frequent turnover among members can also be a problem. To make more frequent meetings possible and ensure continuity, governance body members could form smaller working groups on specific issues, brief new members, discuss relevant issues in advance, prepare input for the main meetings, document the outcomes of the meetings, and follow up on specific decisions (OECD, 2021[10]). Convening members, preparing meeting documents, booking meeting venues, and following up on and implementing decisions made during meetings require financial and human resources. In Korea, the Social Affairs Ministers’ Committee (SAMC), led by the Minister of Education, consists of senior representatives from nine ministries and co‑ordinates a variety of social policies, including those related to skills. The SAMC has smaller working groups to monitor the implementation of its decisions and to raise policy results. Furthermore, a dedicated team of 18 members within the Ministry of Education’s Social Policy Cooperation Bureau support the work of the committee (Box 5.1) (OECD, 2021[10]).

Strengthening horizontal co‑ordination through a common goal across ministries

Besides co‑ordination bodies, horizontal co‑ordination can also be strengthened through promoting a common goal across ministries. When ministries share a common goal, they are incentivised and expected to co‑ordinate with one another. A shared goal could be formalised through strategic documents, such as national development plans and skills-specific policy documents. The shared goal should consist of an overarching vision for skills outcomes that all relevant ministries share and can contribute to.

National development plans foster horizontal co‑ordination in skills policies. When national development plans include skills-related objectives, relevant ministries are incentivised to co‑ordinate with one another to align their respective contributions to reach the skills-related objectives. Table 5.3 shows that most national development plans in Southeast Asian countries feature skills-related priorities. All countries recognise the importance of skills policies in equipping individuals with the skills to meet the evolving demands in the labour market and society due to megatrends. In a few cases – notably Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Viet Nam – skills constitute a standalone objective within their national development plan.

Table 5.3. Skills as a priority in Southeast Asian countries' development plans

|

Country |

Title of national development plan |

Skills-relevant priorities |

|---|---|---|

|

Brunei Darussalam |

National Vision Wawasan Brunei 2035 |

To make Brunei Darussalam a nation widely recognised for its well‑educated and highly skilled people, measured by international standards |

|

Cambodia |

The National Strategic Development Plan 2019‑2023 |

To improve the quality of education, science and technology, and vocational training |

|

Indonesia |

Long-term National Development Plan of 2005 to 2025 |

To improve the inclusion and accessibility of education |

|

Lao PDR |

Five-Year National Socioeconomic Development Plan 2021‑2025 |

To improve workforce skills and productivity and organising a systematic labour market database |

|

Malaysia |

Twelfth Malaysia Plan 2021‑2025: A Prosperous, Inclusive, Sustainable Malaysia |

To enhance the talent and skills required to drive both the digital economy and the 4th Industrial Revolution |

|

Myanmar |

Myanmar Sustainable Development Plan 2018‑2030 |

To develop human resources and social development for a 21st Century Society |

|

Philippines |

Philippine Development Plan 2017‑2022 |

To ensure lifelong learning opportunities for all and provide all citizens with the 21st-century skills necessary to engage in meaningful and rewarding employment |

|

Singapore |

Next Bound of SkillsFuture |

To enable individuals to continue learning, enhance the role of enterprises in developing their workforce, and have a special focus on mid-career workers to help them stay employable and move to new jobs or new roles |

|

Thailand |

The Twelfth National Economic and Social Development Plan 2017‑2021 |

To increase knowledge and skills for the 21st century |

|

Viet Nam |

Five-Year Socio-Economic Development Plan 2021‑2025 |

To improve the quality of human resources together with promoting innovation, application and robust development of science and technology |

Note: Information on Singapore’s Development Plan was not available. Thailand’s Twelfth Development Plan ended in 2021, and a newer plan was not available.

Source: Government of Brunei Darussalam (2018[41]), National Vision Wawasan Brunei 2035, www.gov.bn/SitePages/Wawasan%20Brunei%202035.aspx; Ministry of Planning (2019[42]), The National Strategic Development Plan (NSDP), www.mop.gov.kh/DocumentEN/NSDP%202019-2023%20in%20English.pdf; Government of Malaysia (2021[43]), Twelfth Malaysia Plan 2021-2025: A Prosperous, Inclusive, Sustainable Malaysia, https://rmke12.epu.gov.my/en; Philippine National Economic Development Authority (2021[44]), Updated Philippine Development Plan 2017-2022, https://rmke12.epu.gov.my/en; https://pdp.neda.gov.ph/updated-pdp-2017-2022/; Office of the National Economic and Social Development Board (2022[45]), The Twelfth National Economic and Social Development Plan 2017‑2021, www.nesdc.go.th/ewt_dl_link.php?nid=9640; SkillsFuture Singapore (2023[46]), The Next Bound of SkillsFuture, www.skillsfuture.gov.sg/nextbound.

Besides national development plans, skills-specific policy documents can also foster horizontal co‑ordination. Table 5.4 provides an overview of Southeast Asian countries’ main strategic policy documents covering skills development and use. These documents describe governments’ commitments to achieving certain skills objectives by outlining concrete policy initiatives, identifying resources and mapping all relevant actors involved. The relevant actors include representatives from multiple ministries. However, while most skills-related policy documents in Southeast Asian countries list the relevant actors involved, responsibilities and modalities for engagement are generally not specified, and actors usually agree on their roles only during the policy implementation stage. Thus, there remain opportunities for countries in the region to identify the specific contributions of each actor across relevant ministries and designate co‑ordination mechanisms (such as those discussed earlier) that allow them to work with one another and pursue common objectives.

Table 5.4. Horizontal co‑ordination in Southeast Asian countries’ key policy documents

|

Country |

Skills policy document |

Description of skills-related objectives |

Main governance body in charge |

Reference to horizontal co‑ordination |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Brunei Darussalam |

Education Strategic Plan 2018‑2022 |

To improve government-wide human resource planning and the execution of a government-wide human resource development strategy |

Ministry of Education |

To co‑ordinate with all relevant ministries and government agencies |

|

Cambodia |

National Technical Vocational Education and Training Policy 2017‑2025 |

To improve the quality of TVET in line with national and international standards, increase equitable access to TVET to support employment, and improve the governance of the TVET system (e.g. strengthening of labour market forecasts and the assessment of skills needs) |

Ministry of Labour and Vocational Training |

To strengthen the National Training Board in co‑ordination with other ministries (e.g. Education, Youth and Sport; Planning; Tourism; Economy and Finance) and other relevant institutions |

|

Malaysia |

National Skills Development Act 2006 |

To manage and approve national occupational skills standards, as well as to advise the minister on skills-related concerns |

National Skills Development Council |

To manage co‑operation with the Economic Planning Unit of the Prime Minister’s Department, the Public Services Department, as well as other ministries (e.g. Education; Higher Education; Human Resources; Youth and Sports; Entrepreneur Development and Cooperative; Agriculture and Food Industries; Public Works) |

|

Myanmar |

Employment and Skill Development Law 2013 |

To manage employment and skill development issues throughout the country (e.g. creation of employment opportunities, reduction of unemployment, skills development among workers) |

Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security |

To form and co‑ordinate skills development bodies comprised of relevant ministries and departments, chambers, technical associations, employer and employee federations |

|

Philippines |

National Technical Education and Skills Development Plan 2018‑2022 |

To create an enabling environment for the development and delivery of high-quality TVET, especially among disadvantaged groups, based on the objectives of the Philippine Development Plan and the Labour and Employment Plan |

NTESDP Inter-Agency Committee, Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) |

To improve inter-agency co‑ordination with the Department of Education, as well as with other relevant departments (e.g. Agriculture; Agrarian Reform; Trade and Industry; Labour and Employment; Science and Technology; Social Work and Development , among many others) |

|

Thailand |

Skills Development Promotion Act |

To provide advice to the minister regarding skills development activities (including the creation of national skill standards) and the management of the Skills Development Fund |

Department of Skill Development |

To co‑ordinate across ministries (e.g. Labour and Social Welfare; Finance, Science, Technology and Environment; Education; Industry), agencies (e.g. Budget Bureau; Board of Investment; Tourism Authority of Thailand) and stakeholders. |

Source: Brunei Darussalam Ministry of Education (2018[47]), Ministry of Education Strategic Plan 2018-2022, www.moe.gov.bn/DocumentDownloads/Strategic%20Plan%20Book%202018-2022/Strategic%20plan%202018-2022.pdf; Government of Cambodia (2017[48]), National Technical Vocational Education and Training Policy 2017-2025, http://tvetsdp.ntb.gov.kh/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/NTVET-Policy-2017-2025.ENG_.pdf; Malaysia Commissioner of Law Revision (2006[49]), National Skills Development Act of 2006, www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/95630/112654/F-998717512/MYS95630.pdf; Myanmar Law Information System (2013[50]), The Employment and Skill Development Law, www.mlis.gov.mm/mLsView.do;jsessionid=529614ABDABC2CFD2FA642396B7C6425?lawordSn=7822; TESDA (2018[51]), National Technical Education and Skills Development Plan (NTESDP) 2018-2022, www.tesda.gov.ph/About/TESDA/47; Thailand Department of Skill Development (2002[52]), Skill Development Promotion Ac (B.E. 2545 (A.D.2002), https://ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/82881/128497/F-833541087/THA82881%20Eng2.pdf.

The process of developing strategic documents, such as national development plans and skills-specific policy documents, affects how engaged relevant ministries are. The process of developing strategic documents needs to include all relevant ministries from their inception, throughout their development and implementation, as well as their evaluation. When relevant ministries are fully engaged and have sufficient opportunities to provide input and contribute, they have greater ownership of the final document and hence greater commitment to implementing the tasks laid out in the document. These engagement efforts are particularly important when one ministry is leading the drafting process of the plan. When Latvia developed its Education Guidelines 2021‑2027, it established a national project team with representatives from all relevant ministries to facilitate the process of determining what the Education Guidelines should contain, who should be responsible for what, how relevant actors would co‑ordinate with one another and what the key indicators would be used for measuring progress (Box 5.1) (OECD, 2020[53]).

Box 5.1. Country examples relevant to strengthening horizontal co‑ordination

Australian Industry and Skills Committee (AISC) Emergency Response Sub-Committee

As part of the Australian government’s response to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the former Council of Australian Governments Skills Council established the AISC Emergency Response Sub-Committee in April 2020. The sub-committee consisted of the chair and members of the AISC, as well as representatives from the Australian Council of Trade Unions and the Australian Skills Quality Authority. The sub-committee was established with the objective of “driving rapid and flexible development of training packages during the COVID‑19 crisis”. The success of the sub-committee was based on several factors: the clearly defined function of the sub-committee, with focused roles and responsibilities; direct communication with actors and the organisation of regular meetings, which supported better environmental scanning and more rapid detection of issues and solutions by the sub-committee; a small group of experts who supported rapid but well-informed decision making; and streamlined training product processes.

Korea’s Social Affairs Ministers’ Committee (SAMC)

The SAMC was established to promote horizontal co‑ordination across nine ministries on a variety of social policies, including those related to skills. The committee is chaired by the Minister ofEducation and includes senior representatives from the different ministries. The ministerial meetings of the SAMC are held twice a month to co‑ordinate social policies, assess the achievements of each ministry and consider specific policy actions. Participating ministries can propose topics for the agenda to be put to a vote, which takes place two or three times a year. Examples of skills policies that the SAMC has discussed include measures to innovate in open and lifelong education and training, and measures related to adult learning in higher education. The SAMC has smaller working groups that monitor the implementation of decisions. A dedicated team of 18 members within the Ministry of Education’s Social Policy Cooperation Bureau support the work of the SAMC.

Latvia’s Education Development Guidelines 2021‑2027

The formulation of Latvia’s Education Development Guidelines (EDG) 2021‑2027 was based upon a whole-of-government approach involving all relevant ministries and levels of government, as well as a whole-of-society approach with all relevant stakeholders. One of the important enabling factors that supported the initiative's success was the establishment of an inter-ministerial team led by the Ministry of Education and Science and composed of all relevant ministries. This inter-ministerial team served as a focal point for organising meetings and consultations with government and stakeholder representatives. A series of workshops were conducted to convene representatives from different ministries and experts outside of government to gather their insights on which policy priorities should be outlined in the EDG, the roles and responsibilities of each actor, concrete actions and indicators to measure progress.

Source: Australian Ministers of the Education, Skills and Employment Portfolio (2020[54]), Fast-tracking training and skills during COVID‑19, https://ministers.dese.gov.au/cash/fast-tracking-training-and-skills-during-covid-19; Council of Australian Governments Skills Council (2020[55]), COAG Skills Council Communiqué: April 2020, www.dese.gov.au/skills-commonwealthstate-relations/resources/coag-skills-council-communique-april-2020; OECD Consultations with the Australian Government Department of Education, Skills and Employment; OECD (2021[10]), OECD Skills Strategy Implementation Guidance for Korea: Strengthening the Governance of Adult Learning, https://doi.org/10.1787/f19a4560-en; OECD (2020[53]), OECD Skills Strategy Implementation Guidance for Latvia, https://doi.org/10.1787/ebc98a53-en.

Recommendations for strengthening horizontal co‑ordination

Support skills-related inter-ministerial governance bodies in their engagement of all relevant ministries. The mandates, scope and composition of bodies should be clarified and co‑ordinated relative to each other to minimise unnecessary overlap, confusion and ineffective co‑ordination. Each body should have clear terms of reference specifying the roles and responsibilities. These terms should be based on the specific body’s mandate, capacity and expertise. To raise the effectiveness of and ensure continuity between governance body meetings, members of the body could form smaller working groups on specific issues, brief new members, discuss relevant issues in advance, prepare input for the main meetings, document the outcomes of the meetings and follow up on specific decisions. Each body should have sufficient financial and human resources so that all related administrative tasks and logistical arrangements of the governance bodies can be covered.

Promote a shared skills goal among relevant ministries through strategic documents, such as national development plans and skills-related policy documents. Strategic documents should provide an overarching vision for skills outcomes that all relevant ministries share and can contribute to. The strategic documents should require relevant ministries to co‑ordinate with one another in implementing skills policies. The process of developing these strategic documents should include all relevant ministries from their inception, throughout their development and implementation, as well as their evaluation. When relevant ministries are fully engaged and have sufficient opportunities to provide input and contribute, they have greater ownership of the final document and hence greater commitment to implementing the tasks laid out in the document. These engagement efforts are particularly important when one ministry is leading the drafting process of the plan.

Strengthening vertical co‑ordination

Vertical co‑ordination contributes to effective skills governance in multiple ways. Vertical co‑ordination mechanisms bring together national and subnational levels to support joint policy decision making, implementation and management of skills policies across levels of government, which provides two main benefits. First, vertical co‑ordination improves coherence across levels of government while promoting a more efficient system (OECD, 2020[2]). Resources allocated through a vertical co‑ordination approach are usually used more efficiently given that roles, responsibilities and objectives are expected to be more harmonised and agreed upon with a broader range of government actors. Second, effective communication between national and subnational levels enables a more co‑ordinated implementation of policies allowing the national level to take rapid action on arising needs at the subnational level and target specific challenges more effectively.

In recent years, Southeast Asian countries have begun to increasingly decentralise by providing subnational governments with greater authority to make skills policy decisions (Park and Kim, 2020[56]). Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam have all begun to delegate greater responsibility for skills policy to subnational governments, and, in particular, those relating to the provision of education and training (ASEAN, 2013[57]; Bodewig and Badiani-Magnusson, 2014[58]; Nor, Hamzah and Razak, 2019[59]). For example, Thailand's National Education Act of 1999 mandated the decentralisation of education administration and the delegation of management responsibilities to subnational education committees (Thailand Office of the Prime Minister, 1999[60]). Similarly, Indonesia reformed its Law 23/2014 on Local Government to delegate authority to subnational governments, such as provincial, district and city governments. Cambodia’s ongoing Education Strategic Plan 2019‑2023 intends to strengthen the autonomy of subnational levels and education institutions (Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport, 2019[61]).

However, with a shift towards more decentralised skills systems in Southeast Asian countries, new co‑ordination challenges have emerged. Decentralisation efforts have provided subnational governments with increased responsibilities for skills policy implementation. However, in many cases, this has not been matched with the provision of additional capacity or financial resources (ILO, 2015[62]). As a result, decentralisation efforts have often led to disparities in the implementation of skills policies in distinct subnational regions of the same country. These include difficulties in evenly applying national education quality standards, effectively managing skills development institutions, and providing quality training to educators throughout the whole country (ASEAN, 2013[57]; ILO, 2015[62]; Martinez-Fernandez and Powell, 2010[63]).

These challenges could be addressed through greater collaboration and support to subnational levels facilitated through vertical co‑ordination mechanisms. First, vertical co‑ordination mechanisms enhance clarity regarding the respective roles and responsibilities of national and subnational actors; second, vertical co‑ordination mechanisms facilitate the allocation of resources that match the responsibilities assigned to subnational governments; third, through vertical co‑ordination mechanisms, the national government can support the human, institutional and strategic capacity of subnational governments; fourth, vertical co‑ordination mechanisms support flexibility and adaptability to respond effectively to varying skills needs across subnational governments; finally, vertical co‑ordination mechanisms provide a dialogue platform where all involved are considered on equal terms (Allain-Dupré, 2018[64]). For the specific needs of Southeast Asian countries in transition to decentralisation, vertical co‑ordination mechanisms could help even out differences in institutional capacity across levels of government and make the development and implementation of skills policies more efficient and equitable throughout the country.

Vertical co‑ordination mechanisms come in different forms. Vertical co‑ordination mechanisms can be formal bodies, working groups and ad hoc meetings. Formal bodies, such as those described in the previous section, can, while strengthening horizontal co‑ordination, promote vertical co‑ordination as well. Subnational levels are more commonly involved through working groups, often established to address specific skills issues (OECD, 2020[2]). Working groups are established through a top-down approach, where the national government identifies stakeholders at a subnational level working in each thematic area (for example, the inclusion of people with disabilities in training); these are established through agreements such as Memorandum of Understandings and guided by specific terms of reference. Working groups regularly convene to discuss and monitor the implementation of jointly identified solutions (in the example of a working group on disability inclusion, they could meet to discuss the accessibility challenges in schools and identify measures to ensure appropriate premises). Another form of vertical co‑ordination involves the organisation of ad hoc meetings with representatives from various levels of government who participate in policy development voluntarily and per their areas of interest. These provide more accessible opportunities for dialogue and trust building, helping build more permanent networks over time (Charbit and Michalun, 2009[40]).

Finally, international forums can empower subnational governments' capacity to participate in national‑level policy development forums more actively. For example, the World Organization of United Cities and Local Governments (UCLG) brings together local and regional governments to amplify their global voices through collaboration, dialogue, co‑operation and knowledge sharing (World Organization of United Cities and Local Governments, 2021[65]). The organisation also promotes e-learning and organises forums where mayors can engage at a regional level to discuss issues pertinent to their capacity. Other similar forums are the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UN ESCAP) Forum of Mayors, which advocates for local governments’ indispensable roles and contributions to the ASEAN and global development, as well as the Asia Mayors Forum, which shares similar knowledge-sharing principles (UN ESCAP, 2019[66]).

Recommendations for strengthening vertical co‑ordination

Support subnational governments in implementing skills policies by providing additional human and financial resources and capacity-building support. Through these various mechanisms, best practices and insights can be shared vertically between subnational and national governments and horizontally across subnational governments. The co‑ordination mechanisms should clearly define the respective roles and responsibilities of national and subnational actors and ensure that the allocation of resources matches the responsibilities assigned to subnational governments. When there are capacity constraints in subnational governments, additional human and financial resources should be provided to them, so that they can effectively engage in these mechanisms and follow through with any decisions made through them. Subnational governments could also benefit from their participation in international forums such as the UCLG, which hosts a learning platform to increase the capacity of subnational governments.

Opportunity 2: Promoting a whole-of-society approach

Skills policies in Southeast Asia can benefit from a whole-of-society approach in many ways. Global megatrends and disruptive challenges, such as the COVID‑19 pandemic, cannot be dealt with by governments alone, highlighting the need for strong engagement with key actors in the labour market and civil society when developing and implementing skills policies (OECD, 2019[6]). Engagement with these actors through social dialogue and co‑ordinated action improves the responsiveness of skills policies to the needs of vulnerable groups in Southeast Asia, ensures alignment between skills development and labour market needs, and enables a more sustainable and forward-looking skills system.

Promoting a whole-of-society approach in Southeast Asia involves engaging a wide variety of labour market and civil society actors. In the labour market, these actors include employers and workers and the organisations that represent them, such as employer associations, trade unions and skills sectoral councils. In civil society, these actors include non-governmental and non-commercial institutions, such as NGOs representing vulnerable groups such as women, youth and migrants (OECD, 2019[6]). Across Southeast Asia, the participation of these actors in skills policies depends on various factors, such as the countries’ legislations, governance bodies and engagement approaches, highlighting the need for a clear governance framework on how to engage with them. In line with this, Opportunity 2 explores two policy directions for promoting a whole-of-society approach to skills policies: first, identifying and engaging relevant labour market actors; and second, identifying and engaging civil society actors.

Identifying and engaging relevant labour market actors

Employer organisations play a central role in strengthening skills systems in Southeast Asia, both at the regional and country levels. At the regional level, the Confederation of Asia-Pacific Employers (CAPE), which consists of 21 member countries (CAPE, 2020[67]), and the ASEAN Confederation of Employers, which consists of 7 member countries (ACE, 2020[68]), are active in strengthening the regional competitiveness of Southeast Asian employers and ensuring the sustainability of firms in the face of megatrends. Nearly half (45.5%) of employer organisations that form part of CAPE see issues relating to skills, education and training as part of their mandate (CAPE, IOE and ILO, 2017[69]). At the country level, all ten ASEAN member states have established organisations that represent the interests of a wide range of employers (Table 5.5). While these organisations represent a wide range of employer types, from self‑employed individuals to multinational enterprises, the level of representation has been generally limited by high levels of informality throughout the region (ILO, 2015[62]).

Table 5.5. Representation of employers in Southeast Asia

|

Country |

Examples of employer organisations |

Approximate number of employers/members represented |

|---|---|---|

|

Brunei Darussalam |

National Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

1 300 |

|

Cambodia |

Cambodian Federation of Employers and Business Associations |

2 000 |

|

Indonesia |

Employers’ Association of Indonesia |

5 000 |

|

Lao PDR |

Lao National Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

4 000 |

|

Malaysia |

Malaysian Employers Federation |

No information available |

|

Myanmar |

Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry |

30 000 |

|

Philippines |

Employers Confederation of the Philippines |

600 |

|

Singapore |

Singapore National Employers Federation |

3 350 |

|

Thailand |

Employers’ Confederation of Thailand |

No information available |

|

Viet Nam |

Viet Nam Chamber of Commerce and Industry |

No information available |

Source: ACE (2020[68]), Members of the ASEAN Confederation of Employers, http://aseanemployers.com/ace_website/members-of-the-asean-confederation-of-employers/; DECP (2021[70]), ECOP: Employers’ Confederation of the Philippines, www.decp.nl/partners/ecop-employers-confederation-of-the-philippines-3989; ILO (2022[71]), Indonesia: Employers’ Organization, www.ilo.org/jakarta/info/WCMS_421178/lang--en/index.htm; World Economic Forum (2022[72]), Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (UMFCCI), www.weforum.org/organizations/union-of-myanmar-federation-of-chambers-of-commerce-and-industry-umfcci.

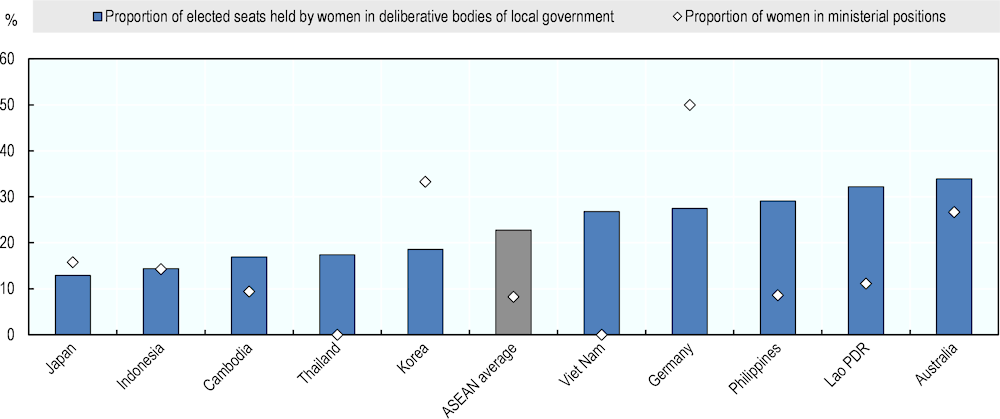

Figure 5.6. Trade union density in Southeast Asian countries and selected OECD countries, 2016

Note: Trade union density is defined as the proportion of employees who are members of a union relative to the total number of employees. This indicator thus does not include workers or labour market participants who are not in paid employment (self-employed, unemployed, unpaid work, retired, etc.). Due to a lack of data, different years were used for the following: Cambodia and Indonesia (2012), the Philippines (2014), Myanmar, Singapore and Korea (2015). Values for ASEAN countries and comparison countries (Australia, Germany, Japan, Korea and the United States) were taken from ILOSTAT, while the value for the OECD average was taken from OECD.stat.

Source: ILOSTAT (2020[73]), Trade union density rate (%) | Annual, https://ilostat.ilo.org/topics/union-membership/; OECD (2020[74]), Trade Union Dataset, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TUD.

In addition to employer organisations, trade unions represent workers in the region; however, membership represents a relatively small share of the ASEAN workforce. As shown in Figure 5.6, trade union density, defined as the share of salaried workers that are trade union members, is low overall in Southeast Asia, averaging at only 8.5%, significantly lower than the OECD average (15.8%). There is also considerable variation in trade union density among ASEAN countries, ranging from 21.2% in Singapore – higher than the OECD average – to low rates in Myanmar (1%), Thailand (3.5%) and Indonesia (7%). This means that a relatively low share of workers in most Southeast Asian countries is formally represented to bargain with employers for better protection of their rights in the workplace, to participate in skills initiatives offered by trade unions, and to inform the development of skills policies by government.

One factor explaining low trade union participation is the lack of a strong social dialogue on labour market matters. Social dialogue traditions, including negotiations, consultations and exchange of information among representatives of governments, employers and workers concerning common issues relating to economic and social policy (ILO, 2017[75]), are still relatively recent in the region. Trade unions emerged in the region only at the start of the 1900s, with the first trade unions gaining traction in the Philippines, while many other countries, such as Cambodia, Lao PDR and Viet Nam, only starting in the 1940s. Over 70 years after the launch of the Freedom of Association and Protection of the Right to Organise Convention of 1948, only five Southeast Asian countries have ratified the convention so far (Bosma, 2020[76]). According to stakeholder consultations, trade unions in the region remain highly fragmented at present. Many trade union organisers face strong hostility from employers and, in some cases, arbitrary arrest and imprisonment by governments. The antagonistic environment for organised labour deters workers from actively participating in trade unions or employee federations, even if skills governance mechanisms are present in countries.

Another major factor explaining low employer and trade union representation in Southeast Asia is the high level of informality in the region. Throughout Southeast Asia, over 70% of all employment is informal (see Chapter 4). Employers and workers in informal employment relationships do not usually participate in formal organisations such as employer confederations and trade unions. In some cases, they do not wish to be identified for fear of their obligations (i.e. formalisation and taxation). As a result, informal workers often go unobserved, making it difficult for formal governance bodies to determine their characteristics, labour market outcomes, challenges and skills needs (USAID, 2013[77]) and to include them.

In addition to a high level of informality, the prevalence of temporary work also inhibits workers’ participation in trade unions in Southeast Asia. Definitive statistics on these types of working arrangements are difficult to come across in the region, although estimates show that temporary work ranges from 30.7% of all total employment in Viet Nam to 53.2% in the Philippines (ILO, 2016[78]). Throughout the region, workers are being hired by firms on a temporary contract basis to significantly cut recruitment costs, resulting in a lack of job security among workers and the withholding of employee benefits, including social security and opportunities for training and further skills development (ILO, 2016[78]). According to stakeholder consultations, workers in these temporary working arrangements are not readily organisable in Southeast Asia since many fear that joining a trade union could be regarded unfavourably by their current employer and lead to a loss of employment.