To ensure that countries are able to adapt and thrive in a rapidly changing world, all people need access to opportunities to develop and maintain strong proficiency in a broad set of skills. This process is lifelong, but the foundations are laid during childhood and youth. Providing young people with the necessary skills not only benefits their own prospects and self-esteem, but also builds strong foundations for economic growth, social cohesion and well‑being. This chapter explains the importance of strengthening the skills of youth for the Mexican state of Tlaxcala and provides an overview of current practices and performance. Three opportunities to strengthen the skills of youth in Tlaxcala are explored: 1) increasing access and quality in pre‑primary education; 2) building a strong teaching workforce; and 3) strengthening the responsiveness of secondary vocational education and training (VET) and tertiary education institutions to labour market needs.

OECD Skills Strategy Tlaxcala (Mexico)

2. Strengthening the skills of youth in Tlaxcala, Mexico

Abstract

Introduction: The importance of strengthening the skills of young people in Tlaxcala

Equipping Tlaxcalan youth with the right skills is important to achieve the state’s social and economic goals. While the strengthening and sharpening of skills is a continuous process throughout life, literature has highlighted the importance of developing certain foundational skills during childhood and youth (Heckman, 2006[1]). A strong process of skills development during childhood supports better educational outcomes. Skills development during early childhood is linked to higher graduation and completion rates across all levels of compulsory education (García, Heckman and Ziff, 2018[2]). Individuals with strong skills are also more likely to enrol in higher education or vocational institutes, and complete tertiary education.

More highly skilled youth are better prepared for a smooth transition into the labour market. On average across OECD countries, those with higher levels of education have better employment outcomes: 84% of tertiary educated younger adults are employed, compared with only 78% of those with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education, and 60% of those without upper secondary education. In addition, the unemployment rate of those without upper secondary education is 14%, twice the unemployment rate of those with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education (7%) (OECD, 2019[3]).

The development of young people’s cognitive and socio‑emotional skills helps foster a culture of adult learning that can facilitate young people’s adaptability to changes in the economy. A strong set of skills also permits youth to perform better in the work environment as they can demonstrate higher levels of productivity and problem-solving abilities. Furthermore, the development of cognitive and socio‑emotional skills is important for the development of professional skills such as effective communication and collaboration in team settings. Beyond the traditional work environment, basic skills are important for promoting innovative entrepreneurship. Cognitive and socio‑emotional skills are essential to identify entrepreneurial challenges and to organise resources to create efficient and sustainable solutions to challenges.

This chapter examines the importance of strengthening the skills of youth for the Mexican state of Tlaxcala and provides an overview of current practices and performance. It is structured as follows: the next section provides an overview of the education system at the federal and state levels. The following section describes how it is organised, identifies the key actors and their responsibilities, and assesses the main trends in student performance and challenges. The final section conducts a detailed assessment of the identified opportunities and provides tailor-made policy recommendations in these areas.

Overview of Mexico’s and Tlaxcala’s education system

As with all other Mexican states, Tlaxcala follows the national education system and is organised into five sequential levels. The first recognised level of education in Mexico, which is the only one not compulsory, is referred to as initial education, henceforth called early childhood education for children under 3 (ISCED 01) in this report. Pre-primary ages 3‑5 (ISCED 02) is the first mandatory level of education. Together, these first two levels of education are considered early childhood education (ISCED 0). These are followed by primary school (grades 1‑6) (ISCED 1) and lower secondary school (grades 7‑9) (ISCED 2). Early childhood education to primary school comprise basic education. After completing these levels of education, students continue on to upper secondary school (ISCED 3), which comprises grades 10‑12. Higher education (ISCED 4), which is not compulsory, follows upper secondary education.

Pre-primary and primary education are provided by public and private schools in three different modalities, each typically associated with a school type: general, communitarian and indigenous. Each modality adapts teaching to different circumstances, such as linguistic and cultural needs, remote locations, and migrant groups. In urban zones, general schools that provide conventional schooling are more common and receive the majority of students, while communitarian schools cater to more rural sectors of the population. Indigenous schools are often found in smaller and rural communities and have a distinguished bilingual/bicultural approach. Pre-primary education for children aged 3-5 became compulsory in 2012.

Lower secondary education is also provided through three distinct modalities, each typically associated with a school type: general, technical and televised (telesecundarias). General schools account for approximately 52% of student enrolment, and 27% of students attend technical schools, which offer a range of technical subjects such as information and communication technology (ICT) and electronics. The remaining 21% of students attend secondary schools that use the televised education modality (SEP, 2019[4]). Telesecundaria is a teaching model that combines distance with face-to-face education. It consists of a 15-minute television programme followed by a 35-minute face-to-face lesson, which is led by a teacher who responds to questions from students and supervises a class activity.

After completing lower secondary education, students enrol in upper secondary school (educación media superior) (equivalent to ISCED 3), which is mainly oriented to young people aged 15‑19 years. It includes high school (bachillerato or preparatoria) and professional technical education. Upper secondary education became mandatory in 2012 due to a constitutional reform presented by the federal government and approved by congress (Secretariat of Goverment, 2012[5]) (Monroy and Trines, 2019[6]). Based on this decree, all states have until the academic year 2021/2022 to expand the provision to grant universal access (Chamber of Deputies, 2012[7]). Upper secondary education is divided into three strands: general, vocational and combined. Only graduates from the general and combined strands of upper secondary education can enter either a two-year post-secondary vocational programme at ISCED level 5 (técnico superior universitario or profesional asociado) or a four- or five-year bachelor’s programme at ISCED 6 level (licenciatura). Depending on the strands, students can take between two and three years to complete this level of education. The selection of a strand usually depends on student preference and the potential professional career they want to pursue.

The main objective of the general and combined strands is to prepare students to enrol in higher education programmes. Institutions in these modalities offer a formative and comprehensive education programme that provides general basic preparation to students covering scientific, technical and humanistic knowledge. In addition to this preparation, institutions in the combined strand offer students the option to simultaneously complete a two-year post-secondary vocational programme. At the end, schools grant a completion certificate to students who graduate successfully.

The vocational strand has two main purposes: it provides the practical skills and competences to solve problems in the workplace, and it gives the scientific, cultural and technical bases to prepare students to continue their studies in higher education. This educational approach facilitates the school-to-work transition of students into a productive activity of their choosing. There are several specialties that students can take in the vocational strand, ranging from agriculture activities to classes in manufacturing skills and services. Most institutions providing a vocational strand also offer a technical degree equivalent to a post-secondary diploma. The fields of speciality are defined based on the need of the labour market, which means that programmes have an immediate connection with the needs of firms’ human resources.

Upon completion of upper secondary education, students can continue on to higher education, which includes post-secondary vocational education and undergraduate programmes. Professional technical education (equivalent to post-secondary VET programmes, ISCED 5) is a two-year programme that grants a technical professional degree. Education institutions at this level offer a wide range of specialisations that aim to respond to labour market needs. The programmes are mostly provided by upper secondary schools; however, depending on the subsystem, universities and independent providers are also able to grant a technical degree.

Undergraduate programmes are four-year or five-year programmes that grant a bachelor’s degree (ISCED 6). A wide range of fields of study are offered, including teacher training. A bachelor’s degree gives access to postgraduate programmes, either to a one-year specialisation (especialización) or a two-year master’s programme (maestría), which are both equivalent to ISCED 7). Completing these postgraduate programmes allows graduates to pursue further academic studies at the doctoral level (doctorado, ISCED 8).

Key actors of Mexico’s and Tlaxcala’s education system

Education at all levels in Tlaxcala, including higher education, is provided by both private and public institutions, although the private sector accounts for a smaller proportion of the enrolment rate, with 12% of the total student population, 18% of teachers and 33% of schools (SEP, 2019[4]). There are a number of federal, state and municipal actors that oversee and manage education design and delivery in Mexico and in Tlaxcala, their responsibilities are summarised in Table 2.1.

At the federal level, the national Secretariat of Public Education (Secretaría de Educación Pública, SEP), which is represented in the cabinet, is the highest authority that oversees national education policy and standards in Mexico. SEP has several responsibilities, such as ensuring that all requirements related to pre-primary, primary, secondary, technical and teacher training are carried out in strict observance of the Constitution of Mexico. It also manages the funding, evaluation and administration of education personnel at a national level (Santiago et al., 2012[8]). SEP establishes the national academic curricula for all levels of education, determines whether each is compulsory, regulates the licensing and qualifications for teachers, and manages VET and tertiary education institutions. It also determines and distributes public education funds to states.

Table 2.1. Main actors in Mexico’s and Tlaxcala’s education system, and their responsibilities

|

Level of management |

Actor |

Main responsibilities |

|---|---|---|

|

National centralised |

Secretariat of Public Education (Secretaria de Educación Pública, SEP) |

|

|

National decentralised (upper secondary education) |

Co‑ordination of each subsystem in upper secondary education (only those subsystems relevant for Tlaxcala are shown):

|

|

|

National decentralised (higher education) |

Co‑ordination of each subsystem in higher education (only those subsystems relevant for Tlaxcala are shown):

|

|

|

State decentralised (higher education) |

Autonomous University of Tlaxcala (Universidad Autónoma de Tlaxcala) Remaining subsystems are private and completely independent from national and state government. |

|

|

State |

Secretariat of Public Education Tlaxcala |

|

|

Local |

Municipalities |

|

|

Local |

School community (school committee composed of teachers, principals, parents, etc.) |

|

Note: National centralised refers to schools and higher education institutions co‑ordinated, operated and funded directly by the federal government. National decentralised refers to schools and higher education institutions that are fully or partially funded and co‑ordinated by the federal government but operated by states. State decentralised refers to schools and higher education institutions that are funded, co‑ordinated and operated by the state government.

At the state level, each Mexican state has a Secretariat of Public Education that is tasked with the management and administration of education provision to its population. The national SEP oversees the general implementation of education, while the states are awarded the full responsibility of provision of basic education services, including indigenous and special education, and teacher training (OECD, 2014[9]). SEP Tlaxcala determines how to administrate the received federal funds based on state needs and strategies. Within SEP Tlaxcala, the Directorate of Basic Education regulates basic education by following and enforcing the regulations established at the federal level.

At the local level in Tlaxcala, municipalities currently have a limited role across all levels of education. The federal law allows municipalities to request modifications to curricular programming when context relevant adjustments are necessary at the local or regional level (Government of Mexico, 2019[10]). In Tlaxcala, the 60 municipalities were responsible for the maintenance of school infrastructure and equipment up to 2019. However, the transference of this responsibility to the school community has weakened the role of municipalities (INEGI, 2019[11]). Despite their formally constrained role, most municipalities in Tlaxcala have a Directorate of Education that carries out local educational projects, such as municipality funded childcare centres, as part of their own initiative.

Upper secondary and higher education institutions have different degrees of government dependence, and are divided into subsystems that group together a set of schools or institutions managed by a specific co‑ordination body. The subsystem can be co‑ordinated by a federal or state body and composed of one or multiple schools or institutions. Upper secondary institutions operate across the state through 11 subsystems, 7 co‑ordinated at the state level and 4 at the federal level (see Table 2.2). Except for the subsystem of private upper secondary institutions, the subsystems are all financially supported by the state government, and four subsystems are mainly funded by the federal government. The Centre of Upper Secondary Studies, Lic. Benito Juárez, and the School of Upper Secondary Schools of Tlaxcala and Community Tele-schools are the only subsystems offering just the upper secondary general strand. Most subsystems offer upper secondary technical or combined strands, such as the School of Scientific and Technologic Studies of Tlaxcala, which is operated by the state.

Most higher education providers are public. As shown in Table 2.3, there are five public institutions that act as decentralised government agencies under the direction of SEP Tlaxcala. These universities are operated by the state, including the Autonomous University of Tlaxcala, which is fully funded by the state, but independently managed. The federal government operates the Technological Institute of Apizaco and the Technological Institute of the Altiplano de Tlaxcala, which are part of the National Technological Institute of Mexico. Private institutions are independent of the government, but co‑ordinated by the state.

Table 2.2. Tlaxcala’s upper secondary education subsystems

|

State subsystem |

Federal subsystem |

|---|---|

|

Upper secondary schools of Tlaxcala (Colegio de Bachilleres de Tlaxcala) |

General Directorate of Technical, Industrial and Services Education (Dirección General de Educación Tecnológica, Industrial y de Servicios, DGETIS) |

|

Tlaxcala Community High School (Telebachillerato Comunitario de Tlaxcala) |

General Directorate of Agricultural Technology Education and Marine Sciences (Dirección General de Educación Tecnológica Agropecuaria y Ciencias del Mar, DGETAyCM) |

|

School of Technical and Profesional Education of the State of Tlaxcala (Colegio de Educación Profesional Técnica del Estado de Tlaxcala, CONALEP) |

General Directorate of the Upper Secondary Education (Dirección General del Bachillerato) |

|

School of Scientific and Technological Studies of the State of Tlaxcala (Colegio de Estudios Científicos y Tecnológicos del Estado de Tlaxcala, CECyTE) |

Training Center for Industrial Work in the State of Tlaxcala (Centro de Capacitación para el Trabajo Industrial en el Estado de Tlaxcala) |

|

Distance Upper Secondary Education (Educación Media Superior a Distancia) |

|

|

Open Upper Secondary School (Preparatoria abierta) |

|

|

Private institutions |

Source: Information provided by SEP Tlaxcala for the purpose of this project.

Table 2.3. Tlaxcala’s higher education subsystems

|

State subsystems |

Federal subsystems |

|---|---|

|

Higher Technological Institute of Tlaxco (Instituto Tecnológico Superior de Tlaxco) |

Technological Institute of Apizaco (Instituto tecnológico de Apizaco) |

|

Technological University of Tlaxcala (Universidad Tecnológica de Tlaxcala) |

Technological Institute of the Altiplano de Tlaxcala (Instituto tecnológico del Altiplano de Tlaxcala) |

|

Polytechnic University of Tlaxcala (Universidad Politécnica de Tlaxcala) |

|

|

Polytechnic University of Tlaxcala, Western Region (Universidad Politécnica de Tlaxcala, Región Poniente) |

|

|

Autonomous University of Tlaxcala (Universidad Autónoma de Tlaxcala) |

|

|

Private institutions |

Source: Information provided by SEP Tlaxcala for the purpose of this project.

Two public subsystems are responsible for the provision of higher education programmes in Tlaxcala: The National Technological Institute of Mexico (TecNM) and the General Co-ordination of Technological and Polytechnic Universities (DGESPE). The total enrolment in higher education in the academic year 2019‑2020 was 37 521. The Autonomous University of Tlaxcala accounts for 44% of total enrolment whereas TecNM and DGESPE account for almost 40%. The DGESPE co‑ordinates three technological institutions in three regions within the state. The remaining 16% of students are enrolled in pedagogic universities, private institutions and research centres that offered mostly graduate programmes.

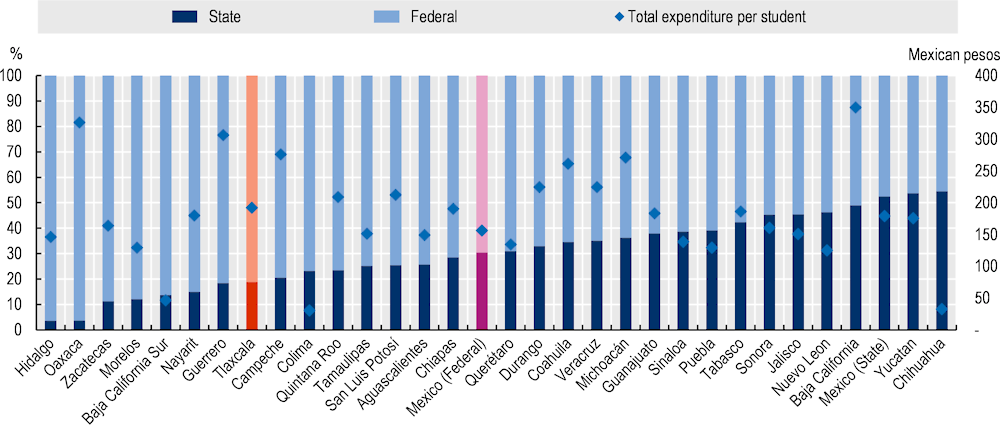

Funding of Mexico’s and Tlaxcala’s education system

In 2020, per student annual direct expenditure within Mexican educational institutions (primary to tertiary) was approximately USD 3 300, one of the lowest in the OECD and roughly one‑third of the OECD average (USD 11 200) (OECD, 2020[12]). For primary and lower secondary education, expenditure per student was USD 2 782 and 2 438, respectively, both less than one‑third of the OECD averages. For upper secondary and VET, per student expenditure was USD 3 418, again roughly one‑third of the OECD average (OECD, 2020[12]). According to government stakeholders, the main source of public funding for tertiary education is the federal government, with the state government accounting for approximately 40% of the total. The average tertiary education expenditure per student in Mexico was USD 5 263 in 20217 less than half of the OECD average (OECD, 2020[12]).

While formally the national SEP is responsible for providing all Mexican states with public funding for basic education, in practice, states also partially fund education. In 2019, federal spending on education amounted to 57%, while state and municipal expenditure was 15.5% and 0.1%, respectively. Private education accounts for approximately 27.5% of total expenditure. State-level spending often addresses specific education challenges areas within the state. For instance, in Tlaxcala a new initiative called Child Welfare Support Programme (Programa de Apoyo para el Bienestar de las Niñas y los Niños) was launched in the 2019‑2020 academic year to increase the participation of disadvantaged students in early childhood education for children under 3 and pre-primary education. The programme targets children of mothers who are working, seeking work or studying. The programme disburses MXN 1 600 (Mexican pesos) for each child aged 0 to 4, as well as MXN 3 600 for each child with a disability (Government of Mexico, 2019[13]).

Performance of Tlaxcala’s education system

Enrolment in education

In Tlaxcala, gross enrolment rates (GER), calculated as the total number of children receiving education as a percentage of the total number of age-appropriate students, vary greatly across all education levels. For instance, the GER for early childhood education for children under 3 (ISCED 01) is low, at 6.9% of the full age-relevant population (Table 2.4), while for four-year-olds it is 99.6%. The GER rate for upper secondary education in Tlaxcala is 77.5%, similar to the national average of 78.9%. Enrolment is mostly concentrated in the general upper secondary strand (66%), followed by combined (22%) and vocational strands (12%). Tlaxcala, compared to other states, has one of the highest proportion of students enrolled in VET and combined upper secondary education in Mexico. These education strands are the most responsive to labour market needs.

Table 2.4 also shows the dropout rates at different education levels in Tlaxcala, compared to the national average. At the primary education level, the reported percentage of students who drop out from school in Tlaxcala is zero, which is lower than the national average of 0.5% (SEP, 2019[4]). For lower secondary education in Tlaxcala, the dropout rate is 3.8%, while for upper secondary education it rises to 8.1%. Although dropout rates across all education levels are lower than national averages, they increase with level of education.

Table 2.4. Tlaxcala’s and Mexico’s education enrolment rates, early childhood education to higher education

|

Tlaxcala (%) |

National (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Early childhood education for children under 3 and pre-primary education |

||

|

Gross enrolment rate: 0- to 2-year-olds |

6.9 |

4.1 |

|

Gross enrolment rate: 3-year-olds |

57.2 |

48.4 |

|

Gross enrolment rate: 4-year-olds |

99.6 |

89.3 |

|

Gross enrolment rate: 5-year-olds |

70.3 |

78.2 |

|

Primary education |

||

|

Gross enrolment rate |

103.8 |

104.7 |

|

Dropout rate |

0.0 |

0.5 |

|

Lower secondary education |

||

|

Gross enrolment rate |

99.7 |

96.1 |

|

Dropout rate |

3.8 |

4.3 |

|

Upper secondary education |

||

|

Gross enrolment rate |

77.5 |

78.9 |

|

Dropout rate |

10.3 |

13.0 |

|

Higher education |

||

|

Gross enrolment rate |

28.4 |

34.8 |

|

Dropout rate |

7.1 |

8.2 |

Note: The higher education GER rate is computed by dividing the number of students enrolled in technical, normal and bachelor’s programme and the total population aged 18‑22 years inclusive. The numerator is taken from SEP (2019[4]). The denominator is computed using the National Survey of Household Income and Expenses (Encuesta de Ingresos y Gastos de Los Hogares, ENIGH, INEGI (2018[14])).

Source: SEP (2019[4]), Key data on the education system 2018-2019, https://www.planeacion.sep.gob.mx/Doc/estadistica_e_indicadores/principales_cifras/principales_cifras_2018_2019_bolsillo.pdf.

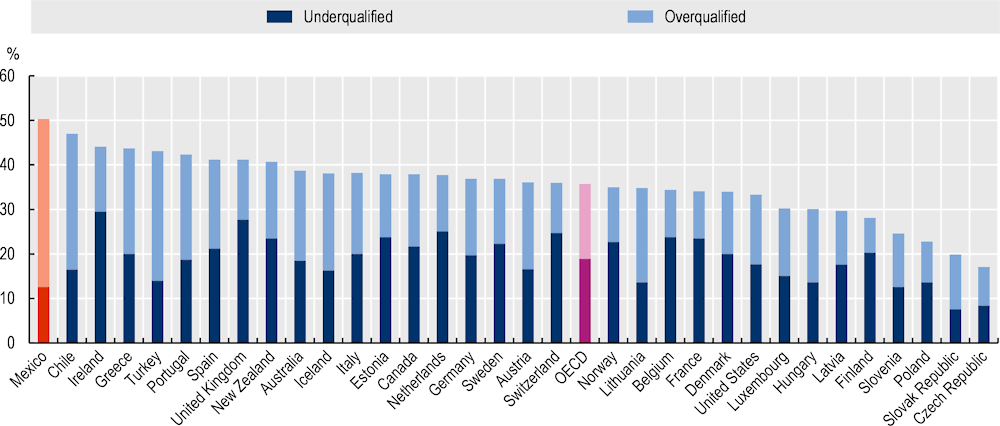

Mexico increased the percentage of adults holding a tertiary education degree from 7% to 23% between 2008 and 2018 (OECD, 2019[15]). This proportion is 10 percentage points lower than the OECD average (33%). Most students in higher education are enrolled in bachelor programmes (88%), and almost 7% of students are enrolled in short-cycle tertiary programmes or VET education (SEP, 2019[4]), which are more responsive to labour market needs. Participation in VET programmes in Mexico is almost three times lower than the OECD average (17%) (OECD, 2019[15]).

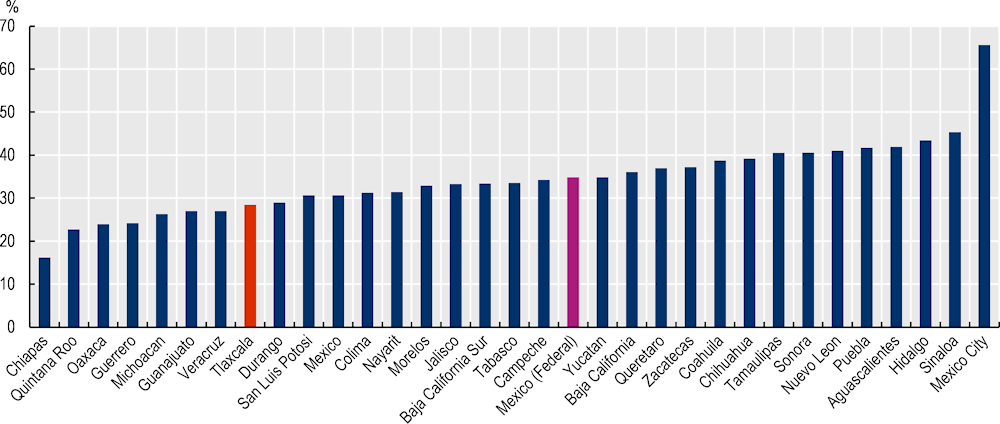

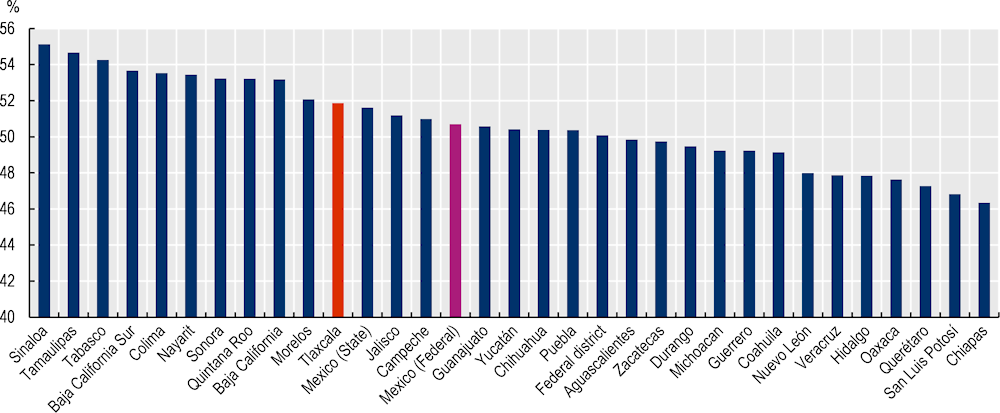

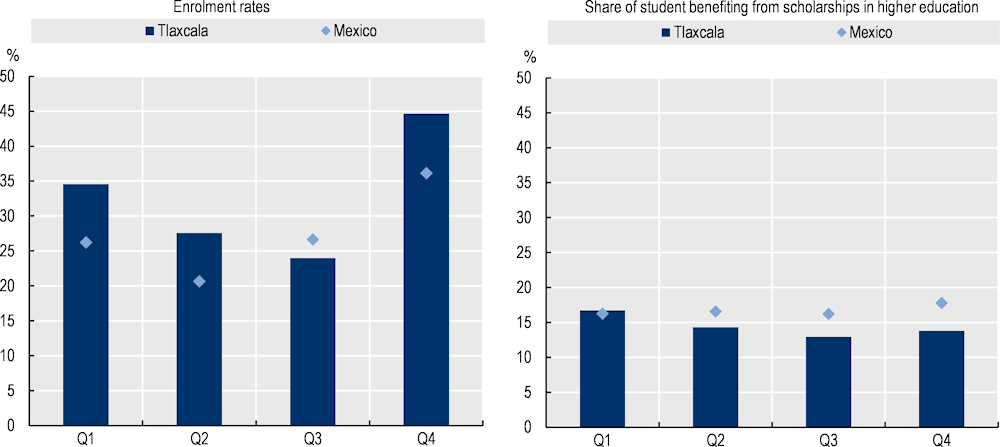

Enrolment in tertiary education has expanded rapidly in Tlaxcala, as in the rest of the country. The enrolment rate in higher education is 28%, which is 7 percentage points below the national average (35%), excluding graduate programmes (Figure 2.1). Furthermore, this expansion has not reached the entire population, and there is still room to improve access among certain groups. For example, in Tlaxcala there is a large enrolment gap between high-income and low-income households. The enrolment rate among the richest households (the richest income quartile) is 37%, which is 5 percentage points higher than the enrolment rate among the poorest households (32%) (The lowest income quartile). Participation in tertiary education is even lower among middle-income households: around 31% and 26% of youth from low-middle- and upper-middle-income households, respectively, enrol in higher education programmes. Low-income households have been targeted by certain social programmes (e.g. Prospera), which has increased their disposable income for investing in higher education (Ferreyra et al., 2017[16]). The current Mexican government has increased the supply of scholarships and subsidies for higher education, targeting mostly disadvantaged young individuals across the country. Young people from rural areas are less likely to enrol in VET or university programmes (21%) than their peers from urban areas (30%). Higher education participation varies significantly across regions in Tlaxcala. Centrosur is the region with the highest enrolment rate (40%), while Oriente has the lowest (19%). In Tlaxcala de Xicohténcatl, the capital city, almost 49% of young people are enrolled in higher education programmes, 19 percentage points more than the rest of the state (32%).

Figure 2.1. Enrolment rate in higher education in Tlaxcala is lower than the national average

Note: Enrolment in graduate programmes is excluded.

Source: INEGI (2018[14]), National Survey of Households Income and Expenses (ENIGH), https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/enigh/nc/2018/.

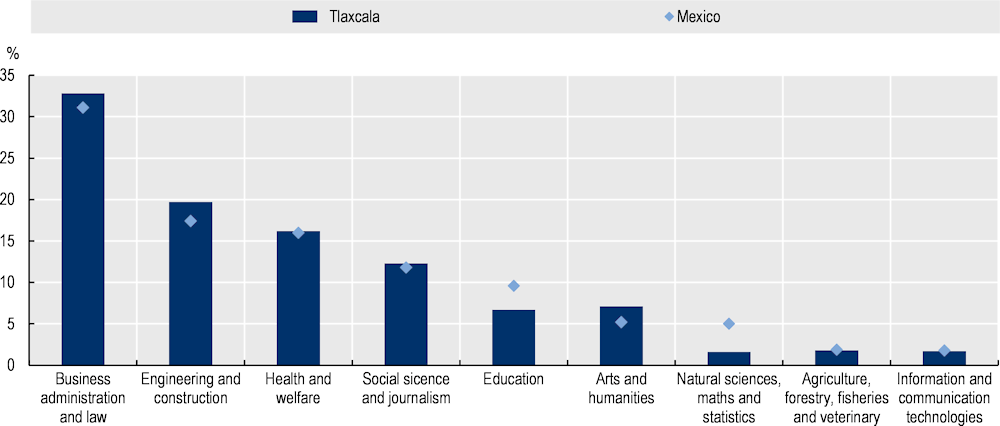

In Tlaxcala, 90% of tertiary enrolment is concentrated in five-year higher education programmes, similar to the national level. No more than 7% of students in Tlaxcala are enrolled in short-cycle programmes or VET. The remaining 3% of students are enrolled in graduate programmes (masters and PhDs). Disaggregation by field of study reveals that the three most popular study choices for Tlaxcalan students are business, administration and law (31%); engineering, manufacturing and construction (18%); and health and well-being (16%).

Educational achievement

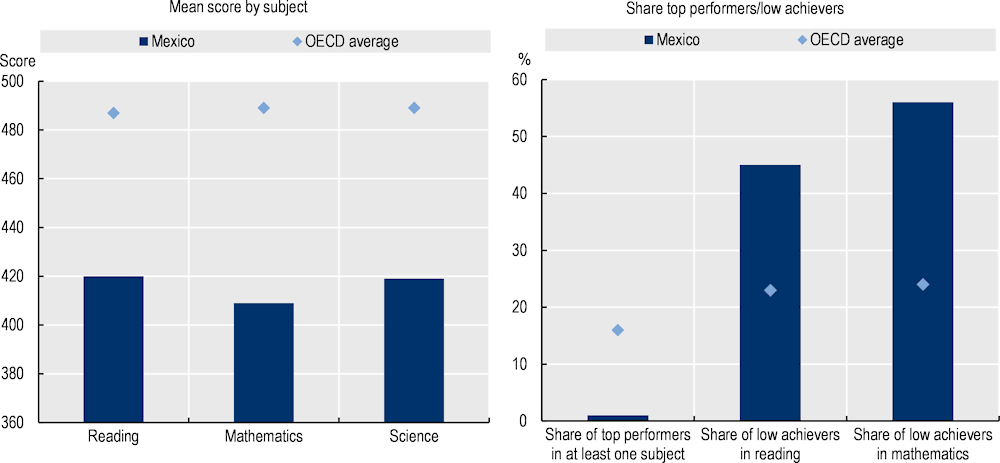

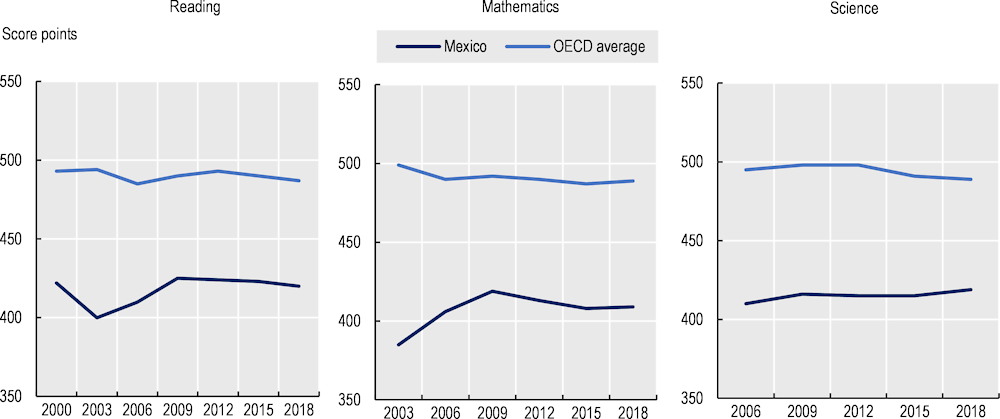

Mexico’s mean performance in reading, mathematics and science in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) has remained stable since the country began participating (Figure 2.2). However, this overall stability hides positive trends in reducing achievement gaps. The score that 90% of Mexican students were able to attain has improved by about 5 score points per 3-year period, on average. This decreasing gap between the performance of the highest and lowest performing students over time reflects a meaningful and consistent decrease in the achievement gap (OECD, 2018[17]).

Figure 2.2. Mexico’s trends in reading, mathematics and science performance in PISA (2003-2018)

Notes: The light blue line indicates the average mean performance across OECD countries with valid data in all PISA assessments. The dark blue line indicates mean performance in Mexico.

Source: OECD (2018[18]), PISA 2018 Database. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/2018database/.

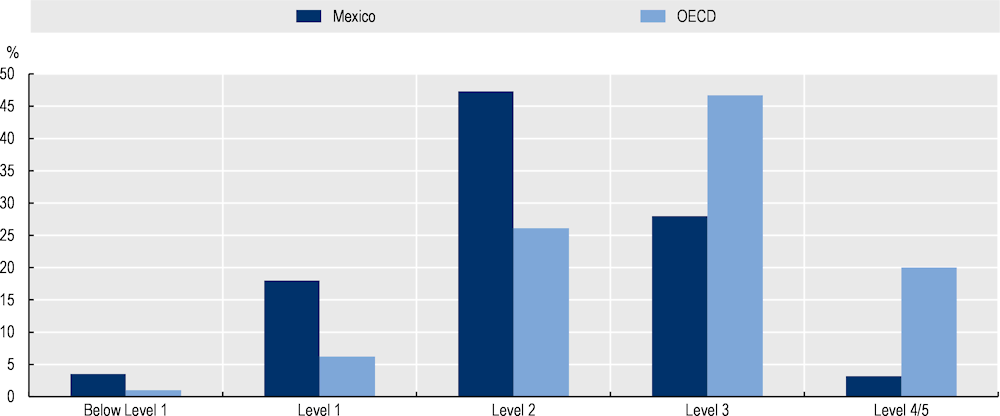

Figure 2.3. Mexico’s performance in reading, mathematics and science, PISA 2018

Despite this progress, Mexican students are still performing comparatively less well than peers in other OECD countries. Figure 2.3 shows that Mexican mean scores for reading, mathematics and science were lower than the OECD average in 2018. In addition, compared to the OECD average a smaller proportion of students in Mexico performed at the highest levels of proficiency (Level 5 or 6) in at least one subject, and a smaller proportion of students achieved the minimum level of proficiency (Level 2 or higher) in at least one subject. Only 1% of students in Mexico were top performers in reading, meaning that they attained Level 5 or 6 in the PISA reading test. Similarly, only 1% of students scored at Level 5 or higher in mathematics, compared to the OECD average of 11% (OECD, 2018[19]).

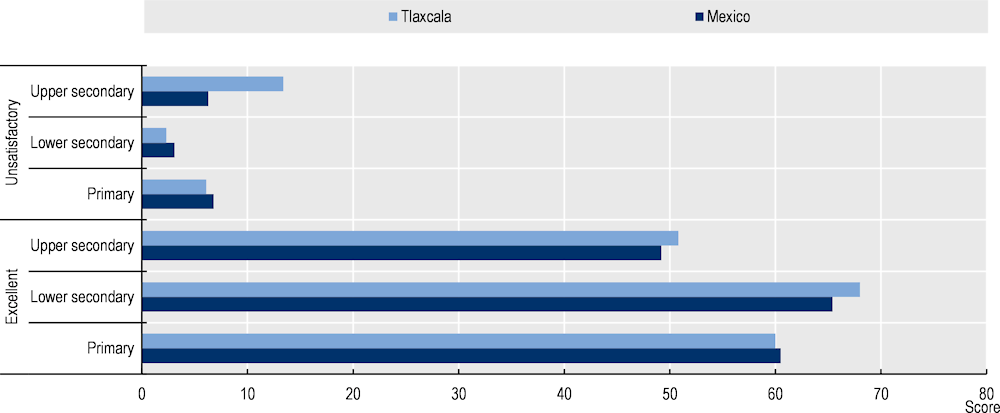

While Mexican students perform worse than their OECD peers on average, the academic achievement of students in Tlaxcala also lags behind the Mexican national average. In the 2015 National Plan for Evaluation for Learning (Plan Nacional de Evaluación de Aprendizaje, PLANEA), which is a national standardised achievement test that evaluates the academic achievement of students in the sixth grade of primary education and the third grade of secondary education, Tlaxcala ranked 29th (out of 32 Mexican states) for lower secondary reading comprehension, and 28th for mathematics. Figure 2.4 illustrates that the proportion of students with an unsatisfactory (lowest) score in Tlaxcala is higher than the national average for primary, lower and upper secondary educational levels. Considering that an unsatisfactory level for mathematics means that students are not able to perform operations with decimals, fractions or basic conversion of units, this is a significant achievement gap that should be addressed.

Figure 2.4. PLANEA mathematics scores for Tlaxcala and Mexico, 2015

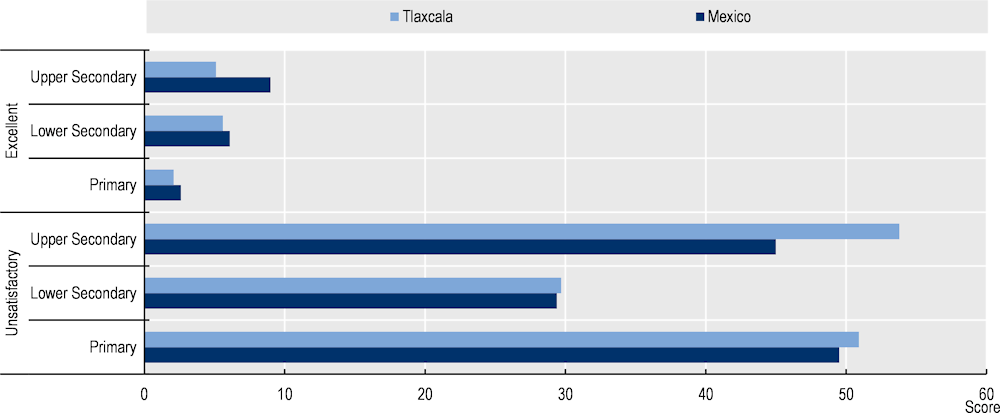

Figure 2.5 shows that the proportion of students scoring an excellent (highest) score in language and communication in Tlaxcala is lower than the national average for primary, lower and upper secondary educational levels. The gap between state and national proportions of highest-scoring students increases from primary to secondary levels of education. In 2018, Tlaxcala PLANEA results for mathematics and language for primary school were similar to those in 2015. The proportion of students with the highest score in Tlaxcala (2.0) was 0.8 percentage points lower than the national level in mathematics, while for reading (6.2), it was 2 percentage points lower than the national level (6.2) (INEE, 2018[20]).

Figure 2.5. PLANEA language and communication scores for Tlaxcala and Mexico, 2015

The skills outcomes of Mexican tertiary education graduates lags behind those of other OECD countries. Figure 2.6 reflects the percentage of adults at each proficiency level in literacy. As observed, the OECD average proportion of adults obtaining higher levels of proficiency is much higher than the Mexican average, with the OECD average proportion of tested adults with a proficiency of 4 or 5 more than 5 times greater than Mexico’s average.

Figure 2.6. Literacy skills outcomes of tertiary graduates, Mexico and the OECD average

Note: The literacy proficiency scale is divided into six levels: Levels 1 to 5 and below Level 1. Being “below level 1” the lowest and level 5 the highest category. The tasks at “below level 1” require the respondent to read brief texts on familiar topics to locate a single piece of specific information. At level 5, tasks may require the respondent to search for and integrate information across multiple, dense texts; construct syntheses of similar and contrasting ideas or points of view; or evaluate evidence-based arguments.

Source: OECD (2019[21]), Skills Matter: Additional Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, https://doi.org/10.1787/1f029d8f-en.

Opportunities to strengthen the skills of youth in Tlaxcala

This chapter will provide advice for strengthening the skills of youth across all stages of education from early childhood education and care to tertiary education, and among both the general population and disadvantaged groups.

Based on the desk research of the OECD team, consultations with the Government of Tlaxcala and stakeholder interviews, the following opportunities to strengthen the skills of youth in Tlaxcala have been identified:

1. Boosting access and quality in pre-primary education.

2. Building a stronger teaching workforce.

3. Strengthening the responsiveness of secondary VET and tertiary education institutions to labour market needs.

Opportunity 1: Boosting access and quality in pre-primary education

Early childhood education (ISCED 0) is essential to the development of cognitive and socio‑emotional skills that are important throughout life. International research supports this, finding that if a child falls behind in learning basic numeracy and reading skills prior to entering first grade, this learning gap continues to widen throughout primary and secondary school (McClelland, Acock and Morrison, 2006[22]). In addition, research indicates that early investment in the development of these skills facilitates the learning of other skills that are important for broader outcomes in adult life, such as health and decreasing intergenerational poverty (Johnson and Jackson, 2019[23]; Cunha and Heckman, 2007[24]).

Data from PISA 2018 lend support to these findings – on average across OECD countries, students who had attended pre-primary education for longer scored better in reading than students who had not attended. The mean reading score of students who had attended pre-primary education for one year (471 points), two years (491 points) or three years or more (493 points) was higher than the score of students who had not attended or had attended for less than one year (444 points).

In 2015, the proportion of Mexican 15‑year‑old students who were low performers was almost 20 percentage points higher for those with 0‑1 years of pre-primary education than for those with 2‑3 years of pre-primary education (OECD, 2018[25]). For this reason it is important to have a strong foundation of skills from the beginning of education to obtain the highest possible return on investment in education across all levels.

Access to quality early childhood education (ISCED 0) is equally essential to Tlaxcala’s future prosperity and policy objectives. As previously discussed in the section above, enrolment rates for pre-primary education vary largely across different ages. It is also widely recognised that in Tlaxcala, children who can benefit most from early childhood education are those who face barriers to access. For these reasons, gaps in the gross enrolment rate reflect a significant opportunity for Tlaxcala to increase the access to and quality of early childhood education.

Tlaxcala could increase access to quality early childhood education by:

Strengthening early childhood education programmes.

Strengthening the initial training of pre-primary education teachers.

Strengthening early childhood education programmes

Ensuring that all children have access to early childhood education is important to enable them all to benefit from early skills development (Berlinski and Shady, 2015[26]). Early childhood education is considered a sensitive period of development that takes place from birth through to age 5. Constant stimulation and care throughout this period is essential for skills development in several developmental areas, including motor skills, cognitive skills and socio‑emotional abilities. For instance, socio‑emotional and communication-related abilities are a focus during early infancy (age 0‑2), and these skills can be built on during age 3‑5 to introduce basic verbal and arithmetic reasoning (Eming, 2002[27]). Early childhood education can be provided through distinct policy approaches, such as increasing enrolment to pre-primary education, increased access to day care services and parental education programmes. In countries with relatively high levels of socio‑economic inequality, like Mexico, access to pre-primary education services plays an especially important role in combatting social and economic inequalities among vulnerable populations. In Tlaxcala, stakeholders indicate that only around 20% of parents seeking pre-primary and early childhood education are able to secure it – illustrating the importance of expanding access to these education levels.

To provide children in Tlaxcala with better early childhood education opportunities, the Supérate programme – Tlaxcala’s social policy flagship programme launched in 2019 – includes a component that targets children in both levels of early childhood education (pre-primary and early childhood education for children under 3). Based on stakeholder conversations, Supérate uses a holistic approach that targets families in poverty in Tlaxcala and seeks to improve their economic conditions by providing several services in tandem to address skills and productivity, financial inclusion, and early childhood development.

To reach families with children between the ages of 0 and 5 (covering children eligible for pre-primary and early childhood education), Supérate trains local “promotors” in basic nutrition and child care and stimulation. According to Supérate officials, these promotors then provide early childhood care services directly in the homes of beneficiaries through periodic visits during which they monitor infant growth and health, identify illnesses the child may have, and connect families to proper health care, while also educating children’s care takers on how to provide better at-home care for their children. Supérate promotors receive in-depth training on early childhood development, which is organised into 10 weekly sessions by child age, level and skillset type; this same training is also offered to interested mothers (Supérate, 2020[28]). Supérate officials report that interest and attendance in this training is generally high among mothers. This guidance is important, as parents may not be well equipped to give proper basic early childhood care (nutrition, health) and often lack knowledge regarding the early stimulation of basic abilities such as fine and gross motor skills, which are essential for a smooth transition to primary education. According to Supérate stakeholders, these early childhood care services are meant to complement and not replace formal early childhood education.

During the COVID‑19 pandemic, Supérate has continued to train promotors and provide early childhood care services for children aged 0 to 5, as this difficult time makes the need for childhood care support even greater. Supérate has begun working with 13 of the 60 municipalities in Tlaxcala, and stakeholders indicate that the remaining municipalities will be incorporated into the programme by 2022. Supérate’s large-scale reach to families living in poverty gives the programme a strategic advantage in addressing barriers to accessing pre-primary and early childhood education for the underprivileged Tlaxcala population.

Although Supérate does not formally offer early childhood education for children under 3, childcare centres (centros de atención infantil, CAIs) and child development centres (centros de desarrollo infantil, CENDIs) offer this type of education. As mentioned by interviewed stakeholders, a substantial number of children who attend these programmes have parents who take advantage of these services in order to work. In 2019, the state of Tlaxcala also launched the Programme to Expand Initial Education (Programa para Expansión de la Educación Inicial, PEEI), which aims to increase the provision of services for early childhood education for children under 3 in Tlaxcala to meet demand. This initiative aims to improve several challenges currently faced at this education level, including limited financial resources for CAI equipment and infrastructure maintenance, training and preparation of CAI educational agents, and the insufficient number of education agents placed in CAIs. The PEEI will also increase the number of home visits offered by educational agents from SEP Tlaxcala to young children as part of non-school early childhood education for children under 3 (educación no escolarizada). Currently, there are 14 such educational agents serving 212 families in Tlaxcala.

According to stakeholders, challenges to increasing enrolment for early childhood education are linked to limited federal funds. Compared to pre-primary schools, CAIs and CENDIs often require more resources, such as medically trained nurses, to provide safe care to infants, as well as other staff specialised in social work, infant health and child development. Stakeholders indicate that in Tlaxcala, many centres lack sufficiently trained staff to operate. Without these resources, existing institutions for early childhood education for children under 3 cannot operate at the necessary standards nor increase their enrolment rates. For pre-primary school enrolment, Tlaxcala has prioritised increased enrolment for ages 4 and 5 in recent years, potentially crowding out children age 3 from accessing pre-primary schools.

There are several infrastructural and resource related challenges for early childhood education for children under 3. A qualitative study by the National Pedagogic University in Tlaxcala found that existing CAIs and CENDIs are often oversubscribed, leading to reduced physical space for children (Ramos Montiel, 2019[29]). Staff or educational agents at CAIs also often lack educational resources and materials to facilitate stimulation and learning for all children. These limited resources can have direct impacts on the quality and safety of child development.

An overarching challenge that Tlaxcala faces is raising or maintaining the quality of early childhood education for children under 3 during this phase of expansion with the PEEI. Addressing infrastructural and resource constraints is an important first step; however, it does not guarantee improvement in development and learning outcomes. The Colombian experience in Box 2.1 shows that the expansion of pre-primary education did not produce the expected learning gains among students when physical investment was not accompanied with quality improvements in other dimensions. These measures are simple but can be effective, such as measures to ensure that increased investments maintain a minimum level of quality by setting teacher-to-student ratio limits and allocating funds to enrich the structural and pedagogical environment.

Box 2.1. Relevant international example of expanding education services: Pre-primary education in Colombia

In Colombia, enrolment rates in pre-primary education increased from 13% in 1990 to 84% in 2015, while in 2011 the government committed to triple expenditure on early childhood education. A recent study by Andrew et al. (2019[30]) analyses the “Hogares Infantiles” (children’s homes) programme, which provides pre-primary education to children from disadvantaged backgrounds aged 5 and younger. Using an experimental design, the authors show that investment in what is often called “structural quality” (e.g. physical infrastructure, staff resources, pedagogical material) alone does not produce the expected learning gains in students. The authors found that when greater resources are given to schools, teachers tend to substitute their efforts and involvement with children and delegate some responsibilities to less experienced and less qualified teaching assistants. The study shows that these children saw no improvements in their cognitive and socio‑emotional development on average, and that for some children the effect was even negative. In contrast, when structural quality was paired with pedagogical training for teachers, children’s cognition, language and school readiness increased by around 0.15 of a standard deviation (SD).

Source: Andrew, A. et al. (2019[30]), Preschool Quality and Child Development, http://www.nber.org/papers/w26191.

From a demand perspective, although cultural and informational barriers hamper access to early childhood education, Supérate stakeholders and staff in close contact with parents indicate that some parents may not fully understand the benefits of pre-primary education, which leads to lower demand. Some families may have household constraints, such as working parents who require small children to stay at home instead of going to school so that they can take care of grandparents. For other households there may be asymmetries of power, where mothers may want to increase their own or their child’s participation but may not be able to convince the other parent to do so.

Recommendations for strengthening existing early childhood education programmes

2.1. Increase demand for early childhood education by targeting informational gaps on the educational benefits. To address the principal demand-side limitation to participation in both pre-primary and early childhood education for children under 3, priority should be placed on raising awareness of the positive long-term educational benefits and addressing any potential sources of distrust in the education system. These efforts could include both targeted awareness campaigns for parents, as well as a “one-on-one” strategy that could entail specialised and trained experts tasked with contacting and establishing ongoing dialogue with individual parents.

2.2. Establish minimum quality standards to safeguard the quality of education throughout and after the expansion of early childhood education for children under the age of 3. The expansion of early childhood education for children under 3 through the PEEI will address shortcomings in the availability of spaces for under-served communities. To ensure that these investments are impactful, Tlaxcala should identify indicators of education quality. These could include the minimum level of preparation of teachers, the minimum level of additional in-service training they should receive, and the educational and didactic materials that centres will receive. Strict monitoring that ensures targets set for these indicators are met for all new and existing education centres could reduce the risk that expanding early childhood education will come at the cost of quality

Strengthening the initial training of pre-primary teachers

The degree of preparedness of pre-primary school teachers is important for children’s learning and to ensure larger returns to the early development of cognitive and non-cognitive abilities. Studies show that children attain higher levels of mastery for numeracy and literacy skills when there are more positive child‑staff interactions, which in turn are influenced by aspects of teacher quality such as pre‑service qualifications and participation in in-service training (OECD, 2018[25]).

The current pandemic has magnified the importance of the initial training and preparedness of pre-primary teachers to deliver high-quality teaching (OECD, Forthcoming[31]). For example, teachers who received strong training in the use and effective application of ICT for educational purposes were better prepared for the change in teaching methods during the pandemic, and may also have had a stronger network of similarly prepared teachers to draw on for support. Schooling prior to entering primary education focuses on developing skills and abilities that prepare a child to acquire more applicable skills such as reading, writing, and verbal and mathematical reasoning. These abilities, which include the development of gross and fine motor skills, rely pedagogically on recreational, playful activities that engage a child’s attention. These learning activities are more difficult to implement successfully through distance learning, and require additional effort to adapt effectively to a completely different learning modality.

The process of becoming certified as a pre-primary teacher in Tlaxcala follows regulations at the federal level by the national SEP. To become a pre-primary teacher, individuals must complete their studies at a teacher training institute, referred to in Mexico as a normal school, and pass exams to receive relevant certification (título docente pre-escolar). Because early childhood education for children under 3 was not formally recognised as an education level until 2019 under the New School Initiative (Nueva Escuela Mexicana), teachers at this level of education were not offered formal pedagogic training.

The initial training of pre-primary education teachers faces several challenges in Tlaxcala. The direct measurements of teacher preparedness and quality has been a politically sensitive issue in Mexico, leading to little or no systematic and reliable sources by which to monitor initial and ongoing pre-primary teacher preparedness. For instance, pre-primary teachers have a portfolio that they are required to update yearly with every diploma, additional education and training received throughout the year. However, stakeholders indicate that in practice teachers do not update these portfolios yearly as expected.

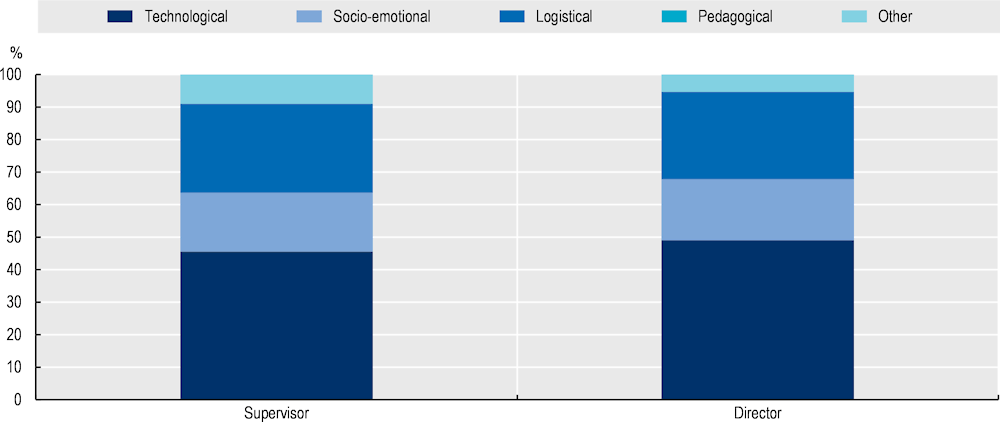

In terms of specific areas requiring strengthening, stakeholders indicate that on average, teachers have a positive disposition and attitude to support their students’ learning, as well as solid theoretical and pedagogical backgrounds on which they can draw to support classroom learning. Stakeholders note that more preparation is needed in integrating digital technology with in-practice learning, supporting the development of socio-emotional abilities and communication with parents.

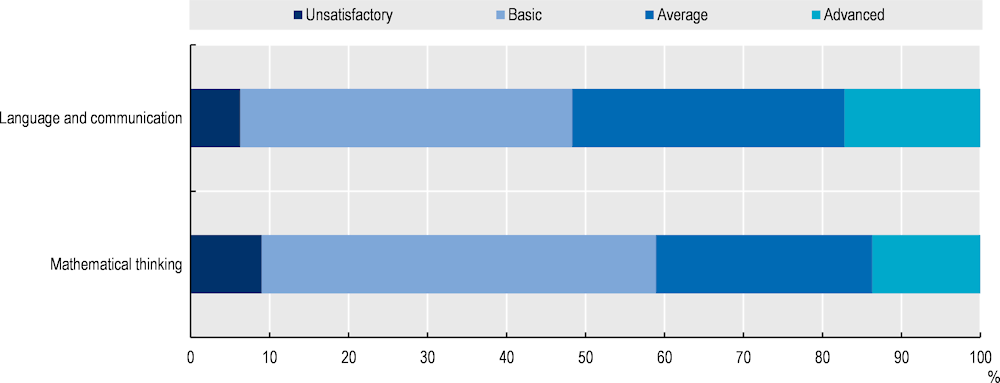

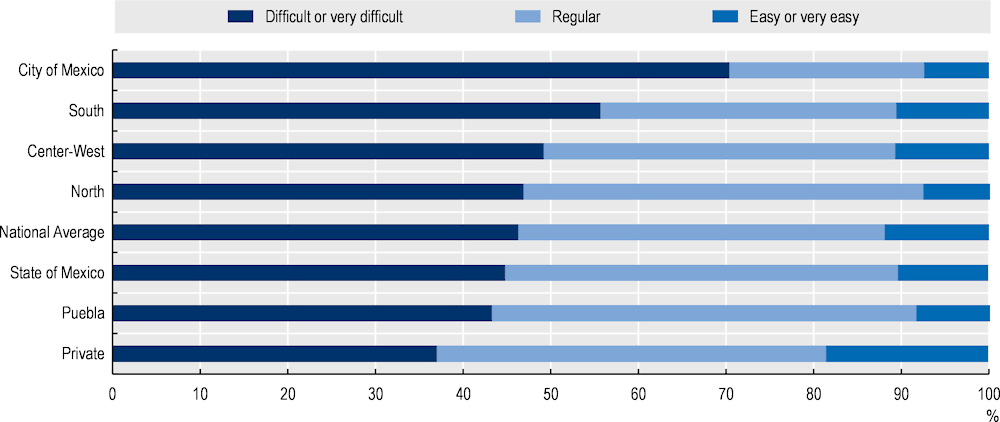

Although it is not possible to accurately assess teacher preparedness from student performance, it can highlight areas for potential improvement. Recent pre-primary student achievement tests indicate low student achievement. Prior to being replaced by PLANEA in 2016, the Exams for Quality of Educational Achievement (Exámenes para la Calidad y Logro Educativos, EXCALE) measured learning for children in grade 3 of pre-primary (age 5) at the national level – although PLANEA measures the same subjects with the same methodology as EXCALE. The most recent EXCALE assessment for pre-primary in 2011 revealed that for reading comprehension and mathematics, between 40% and 50% of Mexican students demonstrated a basic mastery of skills. Figure 2.7 shows the distribution of levels of achievement in language and communication, and mathematical thinking of the Mexican student population of children age 5, corresponding to grade 3 of pre-primary school.

Figure 2.7. EXCALE achievement levels in language and communication, and mathematical thinking in 2011

Source: INEE (2011[32]) Quality of Educational Achievement Exams (Exámenes de la calidad de logro educativos, EXCALE) for 3rd grade preschool students (databases), https://historico.mejoredu.gob.mx/evaluaciones/planea/excale/tercero-preescolar-2010-2011/.

A survey by Together for Learning (Juntos por el Aprendizaje), a coalition of national education stakeholders, collected feedback from teachers of early childhood education for children under 3 across Mexico in 2020, and highlighted deficiencies in pre-primary teacher preparation. Only 4% of teachers surveyed had a post-graduate degree, and 35% had completed up to upper secondary education. In relation to the COVID‑19 pandemic, 17.6% of surveyed teachers reported having difficulties training or retraining as needed to continue providing distance learning. Teachers also highlighted that they did not feel prepared to adequately use technology for educational purposes: approximately 40% of surveyed teachers reported feeling slightly or not capable at all of searching for information on the Internet, and almost 50% reported feeling slightly or not capable at all of generating documents, writing and making simple calculations (Juntos por el aprendizaje, 2020[33]). Stakeholders confirm that the situation is similar in Tlaxcala. To address these issues in Tlaxcala, a teacher training programme was implemented through ICATLAX to support teachers with digital learning challenges. Approximately 8 000 teachers in Tlaxcala have received this training so far.

For pre-primary education, survey responses generally reflected that teachers were not adequately prepared to maintain effective education services and previous levels of quality early childhood education and stimulus when COVID‑19 arrived (Juntos por el aprendizaje, 2020[33]). For instance, several pre-primary school teachers reported not knowing how to use digital tools with children, which led to difficulty finding playful or recreational activities for the learning process. Teachers also reported not feeling capable of using online platforms and information resources and technologies.

Although not directly related to curricular or pedagogic preparation, teachers in Tlaxcala also face challenges regarding the quantity and quality of interaction between teachers and parents, especially in the context of the COVID‑19 crisis. In Tlaxcala, teachers have reported difficulties communicating and planning learning activities for children with parents, especially those who do not have access to social networks or the Internet. For pre-primary school students, distance learning implies less time spent directly in communication with students, as many learning activities require direct guidance by an adult. Beyond the guidance and co-ordination of activities, parents can also have an important effect on learning while using ICT (OECD, 2020[34]). According to PISA 2018 results, high levels of emotional support from parents is linked to higher levels of child self-efficacy, which encourages confidence in the child to increase their educational effort. It is also linked to better performance across all PISA subject matters, in particular for students who use ICT (OECD, 2020[35]). This evidence stresses the importance of collaboration between teachers and parents at the pre-primary education level.

Engagement with parents is a key part of process quality in pre-primary education centres, and has been shown to be strongly associated with children’s later academic success and socio-emotional development. Good communication between parents and pre-primary education staff is critical to enhance the knowledge of staff about the children they work with and to ensure the continuity of learning for children at home (OECD, 2011[36]). Box 2.2 highlights two case studies of how Chile and Germany have developed strategies to improve teacher preparedness for communicating with parents in the context of distance learning for young children to ensure educational continuity.

Box 2.2. Relevant international example: Ensuring educational continuity for children in early childhood education centres

Chile

Following the closure of early childhood education centres in Chile, the Undersecretary of Early Childhood Education worked with the Behavioural Unit from the Innovation Hub of the Chilean government to adapt and implement an educational programme that was first put into place at the beginning of 2020. The programme, based on the “Boston Basics” from Harvard University, seeks to support the early learning of children aged 0‑2 through the participation of parents and caregivers as primary educators. To this end, the programme communicates and disseminates information (through website, videos, etc.) on simple and powerful actions that support children’s development. In response to the closure of early childhood education centres, the programme has been sending text messages with information, facts and tips with subtle instructions and advice to parents of children staying at home. Messaging is based on behavioural insights and communicates five main concepts or ideas to interact with children: 1) give them all your love; 2) talk to them and sing with them; 3) count, group and share; 4) explore playing; and 5) read and comment on children’s stories/books. The programme is currently being evaluated.

Further initiatives have been launched by the main providers of early childhood education in the country. The Integra Foundation (operating more than 1 200 early childhood education centres) provides families with activities and advice related to the Early Childhood Curriculum Framework through a phone application (IntegrApp) to improve parental engagement in the context of the pandemic. JUNJI, the country’s main early childhood education provider, has also released an application (Mi Jardín JUNJI) that facilitates communication between parents and their children’s teachers. For example, parents can share with teachers the activities they are doing with their children and receive feedback. JUNJI and the Undersecretary of Early Childhood Education have made available a range of digital resources on their websites. The materials target specific ages according to the curriculum framework and include videos and games to improve different areas of children’s learning and development (e.g. motor skills, language skills, socio-emotional development, and grouping and counting skills).

Germany

In Germany, the early childhood education sector is regulated and managed at the level of the states (länder). The websites of the respective state ministries provide a range of information and materials that seek to support early childhood education staff in continuing to work with parents and provide educational continuity for children during centre closures. In addition to best practice examples for concrete implementation in day care practice, staff are also provided with background information on media use to be able to advise parents on this topic. The general approach has been to emphasise the importance of continuing to work with parents and children, especially with families whose children do not yet attend the day care centre. Many innovative practices have emerged in this context from early childhood education providers and centres themselves, such as the use of video-conferencing tools in pedagogical practice, online exchange with parents on a regular basis (i.e. to advise and help families in stressful situations at home) and providing online/offline materials for pedagogical activities at home.

Source: OECD (2020[37]), Building a High-Quality Early Childhood Education and Care Workforce: Further Results from the Starting Strong Survey 2018, https://doi.org/10.1787/b90bba3d-en.

To smooth the transition to distance learning for initial and pre-primary education levels, Tlaxcala has responded to education quality related issues stemming from the pandemic by organising informal regular conversations with teachers to identify the main challenges. These spaces have revealed how pre-primary school teachers have been facing the challenges of distance learning. Teachers have generated their own teaching content, videos and instructions for learning activities for parents to follow at home with children. Many have used online social platforms such as WhatsApp to share and better co‑ordinate with parents in the absence of regular in-person discussions. Moving forward with distance learning it will become important to equip teachers of pre-primary and early childhood education for children under 3 with the skills to communicate and co‑ordinate learning activities effectively with parents.

Recommendations for strengthening the initial training of pre‑primary teachers

2.3. Gather and centralise recently acquired pedagogical knowledge and lessons learned from in-service teachers on how to effectively engage with students and parents during the pandemic. Although 2020 was a difficult year, it also entailed a significant amount of learning and adaptation to online learning for pre-primary teachers. However, without the centralised and systematic documentation of the knowledge accumulated by individual teachers, this know-how could be lost, or shared with only a small group of individuals within a teacher’s network. It would therefore be valuable to document and centralise the learning material and know-how generated and learned by teachers to capitalise on existing efforts and provide incoming and/or less experienced teachers with a bank of knowledge to draw on as they continue to address distance-learning related challenges in the future.

2.4. Provide teachers with opportunities for specialised in-service teacher training on how to develop students’ socio-emotional skills. The development of students’ socio-emotional skills can support them to better adapt to learning challenges and to changes in the labour market and society in the future. Tlaxcala can better prepare pre-primary education teachers to strengthen students’ socio-emotional skills by expanding teachers’ access to existing or modified in-service training courses. These efforts could be co‑ordinated with Tlaxcalan institutions such as ICATLAX, which has already been actively providing teachers with training resources to address pandemic-related teaching challenges.

2.5. Improve communication and co‑ordination between teachers and parents by establishing standard practices, such as initial meetings to set expectations and social-norm-oriented practices for parents. Better communication and co‑ordination strategies with parents can improve parental engagement and the learning environment at home for students. To improve communication, teachers could conduct an initial meeting at the onset of the school year to highlight the importance and benefits of parental involvement and to establish a feasible plan of action for collaboration throughout the year. It may also be helpful for teachers to manage communication in small groups of parents (three or four) to leverage social normative expectations and the resulting collective peer oversight to motivate parental engagement.

Opportunity 2: Building a stronger teaching workforce

In the context of supply-side factors in education, teacher preparedness has demonstrated stronger impacts on school learning than, for example, infrastructural investments and the increased provision of school resources (Glewwe and Muralidharan, 2016[38]). Recent literature indicates that teacher preparedness in the classroom has important long-term impacts on student outcomes. For instance, Chetty, Friedman and Rockoff (2013[39]) found that a one standard deviation improvement in teacher value added in a single grade raises the probability of attending higher education at age 20 by 0.82 percentage points, relative to a sample mean of 37%.

In Mexico, approximately 36.6 million students and 2.1 million teachers lost access to education institutions during the COVID‑19 pandemic (Juntos por el aprendizaje, 2020[33]). In many ways, the effort and competences required by teachers has increased greatly due to the pandemic. Teachers now are not only expected to manage traditional pedagogical practices and curricular content, but must also adapt quickly to apply this knowledge in a new distance learning setting. In Tlaxcala, both initial and in-service teacher training courses were severely disrupted. Institutes offering initial teaching training, such as normal schools, as well as all in-person in-service teacher training courses were forced to close. As many of these were not operationally prepared to continue offering educational services online, this led to delays and new challenges for the consistent provision of professional development services. It is likely that mixed learning models, where education is part in-person and part online, will remain in use in the short term.

In this context, the challenge of catering to students with different learning needs in the classroom has been compounded as the education process has shifted to distance learning (OECD, 2020[34]). For instance, modified distance learning has expanded the role of stakeholders in the learning process, including parents and teachers, and thus requires more careful collaboration among these stakeholders. This underscores the importance of preparedness and competencies for all stakeholders, especially teachers and school principals and leaders, as well as the improvement of processes through which these skills are acquired.

This opportunity develops and provides policy recommendations for two aspects of the teaching profession:

Strengthening initial and in-service teacher education and training.

Improving the management skills of school principals and leaders.

Strengthening initial and in-service teacher education and training

One of the main challenges for policy makers is how to sustain teacher quality and ensure that all teachers continue to engage in effective ongoing professional learning. To address this challenge it is important to view teachers as lifelong learners. This perspective considers that teachers should have the necessary tools to build upon their initial knowledge in a way that facilitates their growth. In the framework of a lifelong learning approach it is important to address challenges to improving teacher preparedness both from the outset of their career (initial training) and as part of continuous (in-service) skills strengthening.

Initial teacher training is an opportunity to endow teachers with knowledge and proven best practices from the outset. Initial training equips teachers with the knowledge and skills to teach effectively and to meet the needs of their institution and students, according to their education level. The duration of education, the networks that teachers develop, the programme content and the quality of the education provided overall determine the extent to which initial training prepares teachers to launch and grow on their career path. In-service teacher training is important to provide a continuous means to improve the quality of the teacher workforce and retain effective teachers over time. In addition, it can facilitate teachers’ transition into the workplace and respond to the weaknesses that teachers may have when they complete initial preparation. In-service teacher training is essential as a mechanism to continuously adapt to unforeseen or gradual changes in the social and learning environment.

In Tlaxcala, the Department for Professional Teaching Service (SPT) within SEP Tlaxcala’s Directorate of Educational Evaluation (Dirección de Evaluación Educativa, DEE) is responsible for regulating initial teacher training. SEP Tlaxcala also operates teacher colleges (normal schools). The state of Tlaxcala has six teacher training schools – four are normal schools, and there is the Teacher Update Center (Centro de Actualización de Magisterio, CAM), and the National Pedagogic University (Universidad Pedagógica Nacional, UPN). These schools largely provide initial teacher training (where individuals formally enter the teaching profession) (DGESPE, 2016[40]). They also provide professional development for basic education teachers, and give private providers of basic education authorisation to operate.

In-service teacher training in Tlaxcala can be pursued in two main ways. Teachers can access online training tools and sessions offered at the federal level by SEP Tlaxcala. In Tlaxcala, the SPT is in charge of in-teacher training within SEP Tlaxcala and the Teaching Professionalization (Profesionalización Docente, PRODEP), which offers a catalogue of teacher training courses for teachers to update their skills and professionalise. Teachers can also enrol in courses at local normal schools for teachers, or with ICATLAX.

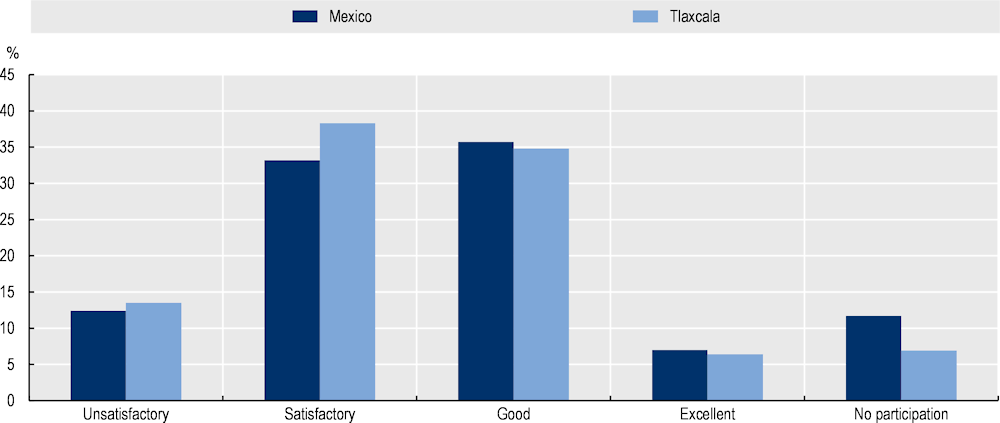

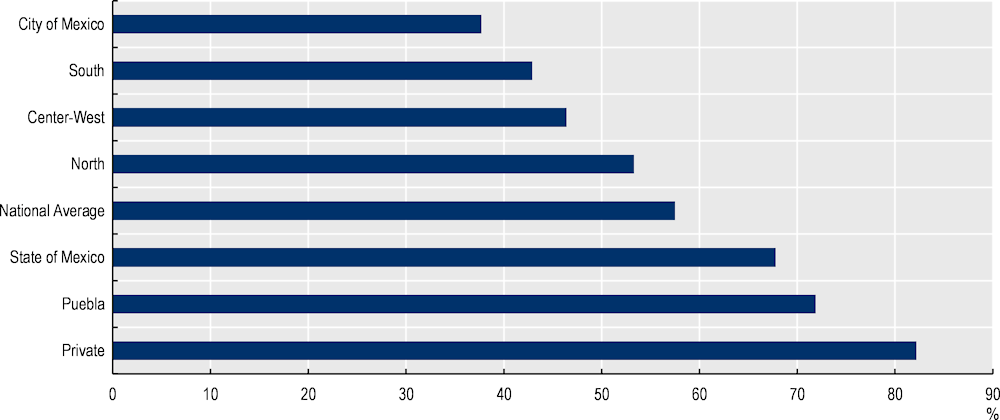

The level of teacher preparedness in Tlaxcala varies significantly. According to the annual evaluation of teachers implemented by the SPT in 2016, fewer than 10% of teachers obtained an excellent level of performance, and only 14% obtained an unsatisfactory result (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8. A significant share of teachers demonstrates unsatisfactory performance

The evaluation of teachers is not mandatory by law, so statistics are based only on teachers who opted to take the exam (more than 90% in Tlaxcala). Teachers decide each year whether they take the exam. While there is no official data on the profile of teachers who opt out of the SPT annual evaluation, stakeholders indicate that often teachers who fear the consequences of low performance or with less motivation decide not to participate.

Closing gaps in teacher preparedness starts with improving the initial training of teachers. In Mexico, the initial teacher training exiting STP exam results have consistently reflected shortcomings in the preparedness of incoming teachers. In 2015, half of individuals who took the exam to be granted entry to the teaching career received a result of “non-suitability”, indicating that they were not sufficiently qualified to occupy a teaching position. These results could suggest that the quality of initial training is not adequate to prepare upcoming teachers, or that the exam is too rigorous and does not accurately assess teaching abilities. Stakeholders indicate that often in Tlaxcala, new teachers are equipped with sufficient pedagogical knowledge, but lack the in-practice expertise to apply this knowledge. Teachers report feeling unprepared due to initial teacher training that does not reflect up-to-date educational innovation in pedagogy and learning theory.

The evidence suggests that there is large variation in the level of preparedness of individuals who have completed their training as teachers and are beginning their profession. This could be because teachers receive their initial training at different types of institution. For example, teachers of lower secondary may receive their training at the CAM, UPN or a normal school, but may also pursue a teaching specialisation at a higher education institution that can be public or private. Teachers of upper secondary education levels are only required to receive their degree from a higher education institution specialising in the subject they will teach. In Tlaxcala, there are four normal schools, in 2019 these were staffed by 123 instructors that trained a total of 790 future teachers (SEP, 2019[4]). The diversity in the type and number of institutions matters because each is organised and prepares teachers to its own standards. This makes it difficult to standardise the quality and content of teaching instruction and training that all incoming future teachers receive, which can often lead to these institutions not preparing candidates properly. Interviewed stakeholders indicated that different types of institutions operated and managed differently leads to differences in how teachers are prepared to deal with challenges in the classroom learning environment.

In an effort to address teacher preparedness at the beginning of the teaching career, the 2017 federal educational reform required that all incoming teachers for all education levels are evaluated not only upon completion of their initial training in order to be certified, but also during the first three years of their teaching career. This move was intended to generate incentives to better prepare individuals to pursue a teaching career, and to strengthen a healthy culture of evaluation and feedback. Stakeholders in Tlaxcala indicate that the recent reform has increased demand for more training and retraining courses, particularly among teachers who completed studies after the reform was implemented. It is not yet clear how the reform has impacted teacher attitudes and perceptions regarding continuous evaluation. The reform presents an opportunity for Tlaxcala to make a long-lasting positive change in how teachers view assessments by taking advantage of the first three years of a teacher’s career to reinforce the link between assessment and effective guidance and support.

The gaps in the preparedness of Tlaxcala’s teachers also reflect several limitations in the in-service teacher training system. Stakeholders indicate that there are insufficient resources for teachers to maintain and improve their skills (e.g. insufficient course availability). This means that teachers often also take short-term courses (diplomados) offered online by several universities across Mexico. For instance, it is common for teachers to take distance learning courses from the Technological Institute of Monterrey (Instituto Tecnológico de Monterrey), which provides training on online and digital pedagogical tools and resources.

In addition to potential gaps in the supply of in-service training opportunities, challenges around teacher preparedness are likely also linked to a lack of demand for in-service training. Federal law does not require in-service teachers to receive additional in-service training, which leads to many teachers, often those who might need it the most, to avoid such training. However, as mentioned the recent reform has generated an increase in teacher demand for retraining courses, although it is largely from teachers who have been admitted to the public teaching career since 2017. Even in settings where in-service training is not compulsory, there are several avenues to compel teachers to engage in professional development, as demonstrated by the case of Norway in Box 2.3.

Box 2.3. Relevant international example: Promoting the participation of early childhood education staff in continuous professional development, Norway

Norway is implementing an ongoing national strategy (2014‑22) to enhance the professional competence of all early childhood education staff. Similar to Mexico, there is no legal requirement for staff to participate in professional development activities. Although the Norwegian strategy establishes financial incentives, these are indirect in nature and targeted mainly at early childhood education providers and centres to compensate for teacher absences while they are in training. Early childhood education teachers can also apply to participate in state-subsidised vocational training and in further education. The Directorate for Education and Training pays for participation in the programme, while the early childhood education provider/owner pays for their employees’ travel and expenses. These multi-actor funded strategies both generate and promote the alignment of incentives across stakeholders in local educational communities, which itself may act as an incentive for teachers to participate in professional development.

The strategy also includes a mentoring scheme for targeted groups of teachers, such as newly employed graduate teachers in early childhood education working with children under the age of 3. The objective of the scheme is to ensure a good transition between initial preparation studies and the profession. The strategy also aims to help recruit, develop and retain talented kindergarten teachers and leaders by strengthening their skills from the outset. An evaluation study showed that the newly employed graduates mostly agree that the mentoring arrangement had helped them develop relevant skills for their work with children, given them confidence and self-awareness of their own competence, and reduced the “practice shock” in the workplace.

Source: OECD (2020[37]), Building a High-Quality Early Childhood Education and Care Workforce: Further Results from the Starting Strong Survey 2018, https://doi.org/10.1787/b90bba3d-en.

The provision of high-quality in-service training for teachers in Tlaxcala is hampered by the absence of a structured and systematic process to understand teachers’ level of competences. Political sensitivity regarding the use of standardised testing as a proxy for teacher quality further complicates the ongoing assessment of teacher training. While the SPT entrance exams reflect the competency levels of teachers at the start of their initial teacher training, there are no systematic centralised monitoring systems for teacher quality. In Tlaxcala, this makes the monitoring of improvement, and of areas in need of improvement, a difficult task. Stakeholders in Tlaxcala indicate that training courses are often recommended or required without any knowledge of teachers’ profile or courses they have previously taken. This results in an inefficient use of teachers’ time if they end up receiving repeated training, or in reduced teacher motivation to receive training overall. Box 2.4 illustrates a measurement framework based on data from the Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) to monitor and measure the participation and trajectory of in-service and initial teacher training.

Box 2.4. Monitoring and measuring the participation and trajectory of in-service and initial teacher training: A measurement framework based on TALIS data

In 2020, the OECD developed a basic structure for systematically assessing the breadth and trajectory of teacher training based on data from TALIS. The structure measures indicators of breadth, which relate to the variety of topics covered in training activities, and indicators of training trajectories, which relate to the amount of training recorded for each teacher in a specific thematic area. Both types of indicator are summarised below:

Breadth of training

Breadth indicators relate to thematic breadth, which is the variety of topics included or covered in training activities. Thematic breadth is measured as the number of areas that staff report having covered at different points in time, ranging from zero to nine thematic areas (child development, child health, classroom management, families, monitoring, transitions, playful learning to facilitate play with problem solving, diversity and pedagogy). Breadth of format relates to the variety of types of in-service training activities (e.g. in-person, peer observation), ranging from zero to ten activities. The indicators for breadth of training are:

Number of thematic areas covered by teachers in their pre-service training programmes.

Number of thematic areas covered by teachers in their recent in-service training programmes.