Effective governance arrangements are essential to support Tlaxcala’s performance in developing and using people’s skills. In the context of structural changes induced by the COVID‑19 pandemic and the ratification of the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement, Tlaxcala will need to swiftly respond to shifting skills demands. Designing and implementing skills policies on the basis of robust governance arrangements, in collaboration with an array of governmental and non-governmental actors, will be key to help Tlaxcala thrive in rapidly changing circumstances. This chapter provides tailored policy recommendations related to two important opportunities for strengthening the governance of Tlaxcala’s skills system: 1) increasing co‑ordination in adult learning across the whole of government; and 2) maximising the potential of skills data to strengthen skills assessment and anticipation exercises.

OECD Skills Strategy Tlaxcala (Mexico)

5. Strengthening the governance of the skills system in Tlaxcala, Mexico

Abstract

Introduction: The importance of strengthening the governance of the skills system in Tlaxcala

Strong governance arrangements are essential for well-functioning skills systems and better skills outcomes. Governing skills systems effectively and efficiently can help reduce potential policy gaps and overlaps, facilitate the efficient allocation of resources, and increase the likelihood of successful policy implementation (OECD, 2019[1]). Policies that aim to strengthen the skills of youth, foster greater participation in adult learning, or make better use of people’s skills can only realise their full potential if accompanied by robust governance arrangements.

Skills policy is inherently complex as it falls at the intersection of multiple policy fields, including education, labour market, innovation, industrial and migration policy (OECD, 2019[1]). Therefore, the governance of skills policies necessitates the involvement of a wide variety of actors, including ministries from across the whole of government and at different levels of government, as well as an array of non-governmental stakeholders (OECD, 2020[2]) including employers, employees, associations, unions, teachers, training providers, career guidance services and students. Skills policies are developed in the realm of substantial uncertainty as they are significantly impacted by megatrends such as automation, digitalisation and globalisation, which have all been recently reinforced by the COVID‑19 pandemic.

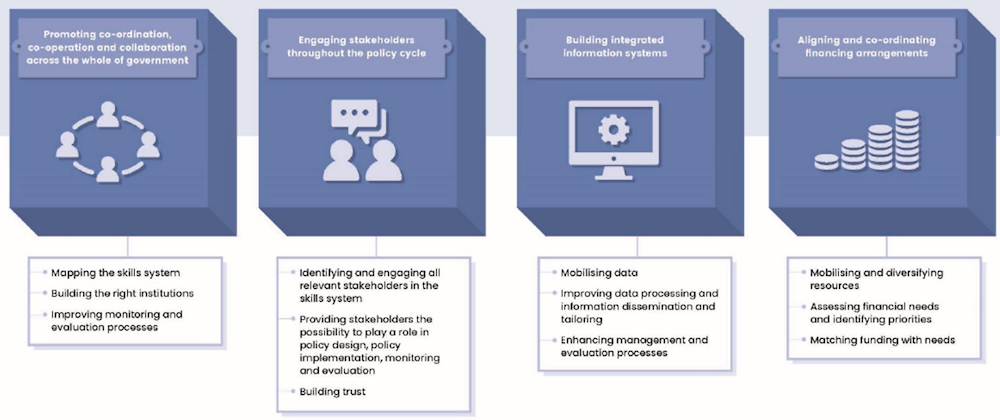

To help policy makers and countries navigate the complex dynamics of the governance of skills policies, the OECD Skills Strategy 2019 (OECD, 2019[1]) identifies four important buildings blocks to govern skills systems effectively: 1) promoting co‑ordination, co‑operation and collaboration across the whole of government; 2) engaging stakeholders throughout the policy cycle; 3) building integrated information systems; and 4) aligning and co‑ordinating financing arrangements (Figure 5.1). Together, these building blocks establish a strong basis upon which policies for developing and using skills can be built.

Figure 5.1. The four building blocks of strong skills systems governance

Source: OECD (2019[1]), OECD Skills Strategy 2019: Skills to Shape a Better Future, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264313835-en.

Promoting co‑ordination, co‑operation and collaboration across the whole of government is central to minimising inefficiencies in skills policy making. This involves fostering a shared conviction about the importance of skills in terms of effectively recovering from the COVID‑19 crisis, mapping skills systems, and promoting and sharing the results of monitoring and evaluation processes to support evidence-based policy making. Effectively engaging stakeholders throughout the policy cycle can bring further benefits and allow policy makers to tap into stakeholders’ on-the-ground expertise and insights regarding the real-world effects of skills policies and regulations (OECD, 2020[2]). Being able to rely on integrated information systems and a rich, consolidated foundation of skills data facilitates the assessment and projection of current and future skills needs, which is crucial for helping policy makers build more resilient education and training systems and for individuals to make more informed labour market choices. In the context of constrained budgets, such evidence-based policy making can also help strategically target investments and generate higher returns on skills investments. Aligning and co-ordinating financing arrangements is necessary to ensure sufficient skills funding and the sustainability of skills investments.

COVID-19 has had a profound impact on the Mexican economy and has considerably affected labour markets, with significant implications for equity and sustainable growth. Tlaxcala is not immune to these challenges. The health crisis has translated into high unemployment rates and widening skills gaps between high- and low-skilled workers, fuelled by accelerating rates of automation and digitalisation. As a result of COVID‑19, Tlaxcala is the fourth most vulnerable state in Mexico in terms of job loss (Bank of Mexico, 2020[3]), and is experiencing significantly constrained budgets. In addition, the ratification of the United States‑Mexico‑Canada Agreement (USMCA) is expected to reshape demand for labour in Tlaxcala, intensifying the need for effective upskilling and reskilling. Tlaxcala’s economic recovery and sustained competitiveness will depend on the capacity of Tlaxcalan policy makers to put in place governance arrangements that promote the adaptability and resilience of the state’s skills system.

This chapter targets two opportunities to improve the governance of skills policies. These opportunities are identified by the OECD and the Government of Tlaxcala as having the largest room for improvement and as being key to improving the adaptability and resilience of Tlaxcala’s skills system. They are: 1) co‑ordination in adult learning across the whole of government; and 2) maximising the potential of skills data to strengthen skills assessment and anticipation exercises. First, the co‑ordination and evaluation of adult learning policies are under-developed in Tlaxcala, which raises concerns about the state’s preparedness to devise effective policy responses to rapidly changing labour market needs. Second, as Tlaxcala’s ability to foresee and adapt to the implications of shifting economic and labour market developments continues to grow, it will be important to maximise the potential of available skills data to assess and anticipate the state’s current and future skills needs.

The chapter starts by providing an overview of Tlaxcala’s current arrangements and performance in relation to the co‑ordination of its adult learning policies, as well as the structure and functioning of its skills data infrastructure. For each of the two abovementioned opportunities, available national and international data are analysed, key actors are identified, relevant national and international policies and practices are presented, and concrete recommendations are proposed.

Overview of Tlaxcala’s selected governance arrangements

This section describes the performance of Tlaxcala’s governance arrangements in relation to: 1) supporting co‑ordination across the whole of government in adult learning; and 2) building integrated information systems for skills data.

Co-ordination across the whole of government in adult learning

A multitude of actors are involved in the provision of adult learning in Mexico at the federal, state and municipal levels, as introduced in Chapter 3. At the federal level, the Secretariat of Public Education (Secretaría de Educación Pública, SEP) is responsible for the delivery of adult learning in higher education institutions and vocational education and training (VET) institutions through public job training centres (centros de formación para el trabajo). The General Directorate of Work Training Centres (Dirección General de Centros de Formación para el Trabajo, DGCFT), established by SEP, provides vocational training through the Training Centre for Industrial Work (Centro de Capacitación para el Trabajo Industrial, CECATI) at the federal level, and through Institutes for Job Training (Institutos de Capacitación para el Trabajo, ICAT) at state and municipal levels. Currently, CECATI operates 199 campuses (planteles) across the country. ICAT has 35 mobile units (unidades móviles) and 30 campuses across 29 states, which operate 297 training units (unidades de capacitación) and 176 mobile units across their municipalities (Gochicoa and Vicente-Díaz, 2020[4]). Whereas CECATI falls under the direct supervision of SEP, ICAT is established under the supervision of state-level organisations such as departments of education to provide training tailored to local needs.

The Secretariat of Labour and Social Welfare (Secretaría de Trabajo y Protección Social, STPS) supports work-based training through incentives and co‑financing mechanisms to stimulate employer investment in training. The STPS also collects and distributes data on jobseekers and vacancies in Tlaxcala, and operates Mexico’s public employment service, the National Employment Service (Servicio Nacional de Empleo, SNE), that links jobseekers with potential employers.

In addition to SEP and the STPS, the Secretariat of Economy (Secretaría de Economía, SE) provides training programmes for small employers. For instance, the SE operates the National Training and Consulting Programme (El Programa Nacional de Capacitación y Consultoría) to help micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) become more profitable and productive. One of the support measures provided by the SE are training programmes for MSMEs, which are supported by SE’s SME Fund (Fondo PyME) (Secretariat of Economy, 2021[5]).

The National Institute for Adult Education (Instituto Nacional para la Educación de los Adultos, INEA) is a federal institute responsible for developing and distributing teaching materials, conducting relevant research, and providing certification for basic youth and adult education. In accordance with the National Development Plan (2001‑2006), INEA signed co‑ordination agreements with most state governments to decentralise adult learning services. Under these agreements, INEA serves as the regulatory, technical and governing body, while the state-level institutions – State Institutes of Adult Education, (Institutos Estatales de Educación para Adultos, IEEA) – provide training programmes and abide by the operating rules of INEA, which includes submitting quarterly reports on resource management and the achievement of goals and objectives based on indicators set by INEA.

At the state level, SEP Tlaxcala oversees the policies and provision of programmes of adult learning. It also oversees the ICAT for the state of Tlaxcala, the Institute for Job Training of Tlaxcala (Instituto de Capacitación para el Trabajo del Estado de Tlaxcala, ICATLAX) (see Chapter 3).

ICATLAX provides education and training for employment purposes to those aged above 15 through its nine training units and one mobile unit. The National Employment Service of Tlaxcala (Servicio Nacional de Empleo Tlaxcala, SNET) collects and distributes data on jobseekers and vacancies in Tlaxcala (see Chapter 3). ICATLAX and SNET collaborate closely in the provision of adult learning and employment services. SNET shares information on labour market demands with ICATLAX so that it can align its curriculum to cater to the skills needed in the labour market.

The Institute for Adult Learning (Instituto Tlaxcalteca para Educación de los Adultos, ITEA), INEA’s branch in Tlaxcala, provides basic skills programmes and remedial education for adults (see Chapter 3). It also certifies primary and secondary education for adults who have not already attended school at these levels.

Within Tlaxcala, CECATI has one state-level entity (entidad) and three campuses in three municipalities through which it provides adult learning programmes designed at the federal level.

Tlaxcala’s Co-ordination of the State System of Employment Promotion and Community Development (Sistema Estatal de Promoción del Empleo y Desarrollo Comunitario, SEPUEDE) is a state initiative aimed at generating opportunities for the inclusive development of communities and the indigenous population. It promotes efforts to strengthen the productive and marketing capacity of artisans, producers and micro-entrepreneurs, including by providing training within communities and to the indigenous population. SEPUEDE is also the main co‑ordination body that connects public, private and social institutions for the purpose of promoting education and social development, economic growth, and the health and culture of communities and the indigenous population.

Tlaxcala currently offers three adult learning programmes that are funded through the federal budget: the Contribution Fund for Technological and Adult Education (Fondo de Aportaciones para la Educación Tecnológica y de Adultos, FAETA), the Care Agreement for the Demand for Adult Education (Convenio de Atención a la Demanda de Educación para Adultos, CADEA) and Supérate. FAETA finances adult learning programmes provided by ITEA and the School of Technical Professional Education of the State of Tlaxcala (Colegio de Educación Profesional Técnica del Estado de Tlaxcala). CADEA only finances adult learning programmes provided by ITEA. Supérate finances and provides training for adults in extreme poverty to develop skills for better employability (see Chapter 3). Supérate offers free training to individuals between the ages of 15 and 64 in several topics, including financial education and micro-business entrepreneurship. It also helps adults develop the skills needed in strategic sectors (e.g. automobile, chemistry, textiles).

Table 5.1 summarises the objectives of key actors involved in adult learning in Tlaxcala, as well as associated bodies.

Table 5.1. Key actors involved in adult learning in Tlaxcala

|

Type |

Actor |

Objective/mission |

Associated bodies |

Level of government |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Government bodies |

SEP Tlaxcala |

|

SEP DGCFT ICATLAX |

State, municipal |

|

National Employment Service of Tlaxcala (Servicio Nacional de Empleo Tlaxcala, SNET) |

|

STPS SNE |

State |

|

|

Institute for Job Training of Tlaxcala (Instituto de Capacitación para el Trabajo del Estado de Tlaxcala, ICATLAX) |

|

SEP Tlaxcala DGCFT ICATLAX units |

State, municipal |

|

|

Training Centre for Industrial Work (Centros de Capacitación para el Trabajo Industrial, CECATI) |

|

DGCFT |

State |

|

|

Institute for Adult Learning (Instituto Tlaxcalteca para Educación de los Adultos, ITEA) |

|

INEA |

State, municipal |

|

|

Supérate |

|

ICATLAX |

State |

|

|

Government initiative |

Co-ordination of the State System of Employment Promotion and Community Development (SEPUEDE) |

|

SEP Tlaxcala DGCFT ICATLAX |

State |

Integrated information systems and key sources of skills data

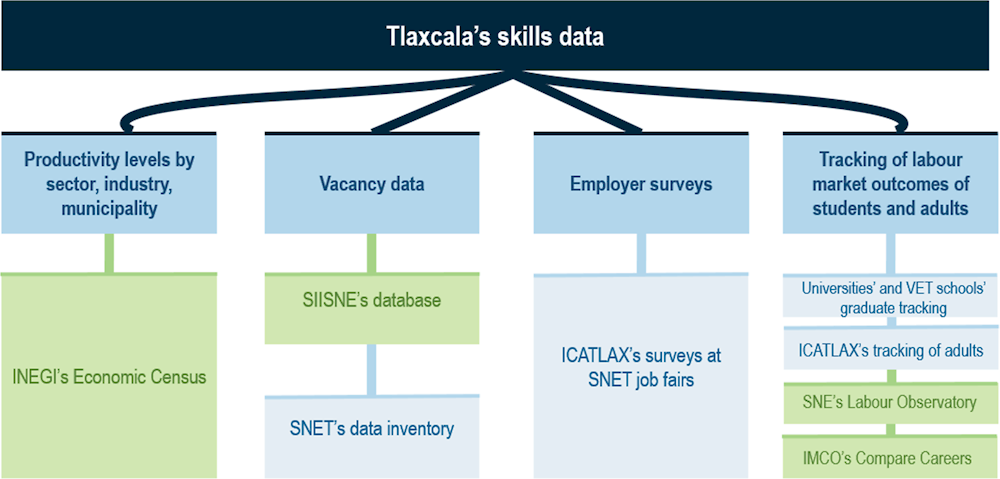

A strong and integrated information system is central to the ability of governments to assess and anticipate current and future skills needs (OECD, 2019[1]). Such a system helps to inform the choices of a wide range of actors in a way that helps to align skills demand and supply. These actors include government, education and training providers, and individuals (e.g. students, jobseekers, workers and employers). Tlaxcala draws on a number of key federal and state-level data sources that provide information on the demand and supply of skills in the state (Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2. Overview of Tlaxcala’s skills data

Note: Darker blue refers to a data type, lighter blue indicates a state-level data source, and green indicates a federal data source.

INEGI = National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía); SIISNE = Integrated Information System of the National Employment Service (Sistema integral de información del Servicio Nacional del Empleo); IMCO = Mexican Institute for Competitiveness (Instituto Mexicano para la Competividad).

The Economic Census (Censo económico), administered at the federal level by the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI), provides information on the productivity levels of specific sectors and industries in each of Tlaxcala’s 60 municipalities (INEGI, 2020[6]). Data reports produced by INEGI help Tlaxcala’s policy makers adjust the education and training offer so that it responds effectively to the skills needed in the most productive sectors. The Integrated Information System of the National Employment Service (Sistema integral de información del Servicio Nacional del Empleo, SIISNE), administered by the National Employment Service Unit (Unidad del Servicio Nacional de Empleo, USNE), gathers data on vacancies and jobseekers in each Mexican state, including Tlaxcala. SIISNE relies on each state’s employment service for the input of data. In Tlaxcala, SNET is in charge of inputting vacancy and jobseeker data into SIISNE. Data from SIISNE are analysed by USNE, which sends aggregate data reports for the previous month to state employment services during the first fifteen days of the current month.

At the state level, SNET developed its own internal vacancy data inventory in 2017, which is independent from SIISNE. The internal inventory collects data on the number of jobseeker registrations (atenciones) and vacancy matches (colocaciones) in Tlaxcala, made on the basis of SNET officials matching jobseekers with jobs, as well as the number, characteristics and distribution of jobseekers (registered and matched with jobs) and vacancies across Tlaxcala’s five municipalities (Tlaxcala, Apizaco, Huamantla, Zacatelco, Calpulalpan) covered by SNET’s regional units (unidades regionales). SNET further supplements these data by conducting phone interviews with jobseekers registered in Tlaxcala’s Employment Portal (Portal del Empleo) to get a fuller picture of their skills, abilities and working history. The internal vacancy inventory allows SNET to: 1) remain informed of labour market developments in each zone; 2) monitor the performance of SNET officials based on the number of registrations and vacancy matches facilitated; and 3) generate projections regarding future registrations and vacancy matches needed. Based on such analysis, SNET’s Department of Planning and Occupational Information (Dirección de Planeación e Información Ocupacional) produces summary reports, which are regularly shared with SEPUEDE’s planning and finance departments and with ICATLAX to help it adjust its training offer.

Using data from the vacancy inventory, SNET’s Department of Job Matching (Dirección de Vinculación Laboral) is in charge of matching jobseekers to identified vacancies, such as through job fairs organised every three months, which have become virtual since the outbreak of the COVID‑19 pandemic. ICATLAX carries out employer surveys at these job fairs, where all participating companies are asked to fill in a questionnaire on the skills profiles sought and qualification levels required, as well as their training needs and budgets earmarked for training. At each job fair, ICATLAX is able to collect between 15 and 20 completed employer questionnaires.

Tlaxcala relies on both state and federal sources to track the labour market outcomes of graduates and adults who have completed training. This information allows Tlaxcala’s policy makers to have a better picture of the state’s skills supply, while serving as a proxy for gauging the labour market demand for the skills that graduates and adults possess. Universities and VET schools in Tlaxcala track graduates following the completion of their studies on voluntary basis. The universities that engage in this exercise track students for up to three years after graduation through surveys that enquire about students’ employment outcomes. Certain VET schools also send surveys to graduates that enquire about progression to further studies and labour market insertion. ICATLAX tracks adults who have completed its training courses through satisfaction surveys administered twice a year. These surveys shed light on the usefulness of ICATLAX training in terms of employability.

At the federal level, the SNE has developed the Labour Observatory platform (Observatorio Laboral) that shows graduate tracking results based on data from the National Survey of Occupation and Employment (Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo, ENOE) (OECD, 2017[7]). Through its online comparison tool, the Labour Observatory enables the comparison of approximately 70 fields of study at the university level (carreras universitarias) and their labour market outcomes (employability rates, average monthly salaries) in Mexico, as well as the trends and characteristics of various occupations. At the state level, including for Tlaxcala, the platform outlines the number of enrolled students and graduates by field of study, their average salaries, field-of-study mismatches upon entering the labour market, and suggestions on which education institutions offer these courses in Tlaxcala (SNE, 2020[8]). Similarly, the online Compare Careers (Compara Carreras) portal of the Mexican Institute for Competitiveness (Instituto Mexicano para la Competividad, IMCO), based on ENOE, enables the comparison of a wide range of labour market indicators (employment, unemployment and informality rates; average monthly salaries; return on investment, etc.) for 51 university fields of study and 17 pathways that lead to the completion of an advanced technical certificate across Mexico (IMCO, 2020[9]). The platform also includes a state-level search engine for secondary VET and higher education institutions and fields of study.

Performance of Tlaxcala’s skills governance arrangements

Co-ordination across the whole of government in adult learning

In Tlaxcala, policy co-ordination in adult learning between the state and municipalities is often hindered by the lack of an effective legal framework and co‑ordination mechanisms. Currently, the State Education Law governs the provision of education and institutionalises policy co‑ordination among relevant actors. However, it does not establish clear co‑ordination mechanisms for the provision of adult learning. Although it stipulates broad the objectives of adult learning, it does not clearly define the roles and responsibilities of the state and municipalities in adult learning provision. In addition, the section of the law that institutionalises co‑ordination among different levels of government relates mainly to co‑ordination between federal and state levels in basic and secondary education. The absence of clear guidelines makes state and municipal co‑ordination in adult learning weak compared to the co‑ordination involved in basic and secondary education.

Another key co-ordination mechanism between municipalities and the state in terms of adult learning are state and municipal development plans. The Municipality Law of the State of Tlaxcala requires municipalities to develop and submit their plans to the state government and ensure that they are aligned with the State Development Plan of Tlaxcala. The Institute of Municipal Development (Instituto Tlaxcalteca de Desarrollo Municipal) was established at the state level to assist municipal governments in formulating development plans and facilitating communication with municipalities. However, this institute was dismantled in 2017 as part of institutional reforms and its responsibilities were transferred to the Legal Directorate of the Secretary of Government of the State of Tlaxcala.

Stakeholders in Tlaxcala have commented that there clearly lacks a long-term vision for the adult learning system in Tlaxcala, which allows the priorities for adult learning to shift in an uncoordinated fashion with electoral cycles. Evaluation mechanisms, which could generate evidence-based support for maintaining or discontinuing certain adult learning programmes, are underdeveloped and fragmented. There is no co‑ordinated evaluation mechanism that evaluates the impact of adult learning programmes of different providers with the same set of clearly defined criteria. Currently, adult learning providers, including ICATLAX and ITEA, carry out their own evaluation processes relying on differing sets of criteria. As a result it is impossible to assess the success and impact of adult learning programmes in a co‑ordinated manner. Most of Tlaxcala’s institutions providing adult learning reported a lack of capacity to analyse the results of fragmented evaluations and use them to inform the necessary adjustments in programme planning and implementation.

International evidence reveals that Mexico ranks below average among OECD countries in terms of its use of evidence-based policy making. According to the latest Sustainable Governance Indicators Survey,1 Mexico ranked 27 out of 41 countries in the executive capacity component of the governance domain (Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2020[10]), which measures a country’s performance in evidence-based regulatory impact assessments (RIA) of legal acts and public policies. In the latest survey, room for further improvement was identified for Mexico, including through applying RIA for subnational regulatory projects and strengthening stakeholder engagement in the RIA process.

Making use of integrated information systems and skills data

Making use of integrated information systems and skills data for assessing and anticipating current and future skills needs in Tlaxcala requires the use of both federal and state level data sources. As highlighted above, there are federal data sources on which Tlaxcala’s policy makers rely at the state level; however, these sources are not always easily accessible, sufficiently granular or timely. For instance, the data from the Economic Census cannot fully capture the evolving dynamics of Tlaxcala’s economy as it is only administered every five years. Similarly, SIISNE’s vacancy data cannot be readily accessed from the state level. Given such constraints it is difficult for Tlaxcala to systematically rely on data supplied from the federal level in the design of its skills policies. To address the data gaps, Tlaxcala started gathering relevant state-level skills data, for example through SNET’s internal vacancy inventory, to facilitate more targeted data analysis (e.g. through more flexible data disaggregation) that is not feasible by using USNE’s reports. Nevertheless, the analytical basis and dissemination of results from Tlaxcala’s skills data could be further improved, as could the co‑ordination of these efforts with federal institutions.

Graduate tracking in Tlaxcala could be further developed, and policy makers could take greater advantage of its results. Not all of Tlaxcala’s universities and VET schools carry out graduate tracking, and the results from these exercises are not reported to and consolidated by government entities in charge of education and training (e.g. SEP Tlaxcala, ICATLAX).

It is not easy for Tlaxcala citizens to get an overview of the state’s labour market developments and skills needs based on the graduate tracking portals administered at the federal level (Labour Observatory, Compare Careers). The Labour Observatory does not provide Tlaxcala-specific indicators for many fields of study, even where state-level disaggregation should be available, and Compare Careers lacks state-level disaggregation.

Tlaxcala lacks a state-wide instrument to survey employer needs, which could help inform and steer skills policy making towards greater alignment with labour market requirements. The employer surveys carried out by ICATLAX are restricted to companies that have participated in SNET’s job fairs. Equally, the opportunity to supplement skills data with qualitative insights from key stakeholders seems underdeveloped. Currently, there is no formal mechanism for systematically engaging stakeholders in skills assessment and anticipation exercises.

Opportunities for strengthening the governance of the skills system

Based on the desk research of the OECD team, consultations with the Government of Tlaxcala and stakeholder interviews, the following opportunities for strengthening the governance of Tlaxcala’s skills system have been identified:

1. Increasing co-ordination in adult learning across the whole of government.

2. Maximising the potential of skills data to strengthen skills assessment and anticipation exercises.

Opportunity 1: Increasing co-ordination in adult learning across the whole of government

Adult learning policies rarely fall under the domain of a single ministry or level of government, but span the domains of multiple entities and federal, state and municipal levels of government. Adult learning policies, therefore, require a whole-of-government approach that necessitates well-functioning horizontal (inter-ministerial) and vertical (different levels of government) co‑ordination arrangements. Co‑ordination across the whole of government also promotes synergies among different actors and provides effective service delivery to individuals. Robust co‑ordination across the whole of government can contribute to improving the effectiveness of adult learning policies.

Tlaxcala should take advantage of the benefits of stronger whole-of-government co‑ordination in adult learning by:

Promoting vertical co-ordination in adult learning between the state and municipalities.

Strengthening adult learning evaluation mechanisms.

Promoting vertical co-ordination in adult learning between the state and municipalities

Effective vertical co-ordination across different levels of government is essential for successful policy delivery and implementation in decentralised adult learning systems. In the case of Tlaxcala, co‑ordination between the state and municipalities is particularly important as Tlaxcala has a relatively large number (60) of municipalities. Furthermore, evidence shows that Tlaxcala is one of the Mexican states most vulnerable to job loss as a result of the COVID‑19 pandemic (Bank of Mexico, 2020[3]). Tlaxcala is therefore under pressure to swiftly adapt its adult learning policies and programmes to increase the employability of its population in the context of rapidly evolving skills needs. Vertical co‑ordination between the state and municipalities will be critical in allowing municipalities to communicate their specific needs and challenges to the state, and for the state to respond effectively by providing tailored support to address these needs and challenges. However, stakeholders have noted that co‑ordination between the state and municipalities in adult learning has not been effective due to the lack of well-functioning co‑ordination support mechanisms.

Across OECD countries, several mechanisms, including legal mechanisms and co‑ordination bodies, are found to facilitate vertical co‑ordination between different levels of government (Box 5.1).

Box 5.1. Mechanisms to facilitate co-ordination between multiple actors and levels of government

OECD countries have reported a range of mechanisms to facilitate co‑ordination between different actors and levels of government:

Legal mechanisms and standard setting: Legislation, regulations and constitutional change that assign responsibilities and commensurate resourcing, as well as standards for inputs, outputs and/or outcomes of a service.

Contracts: Commitments to take action or follow guidelines that transfer decision-making rights between parties.

Vertical and horizontal (quasi-)integration mechanisms: Mergers and horizontal and vertical co‑operation at the subnational level through intercommunal structures and joint municipal authorities.

Co-ordinating bodies: Government or non-government groups that promote dialogue, co‑operation and collaboration, build capacity, align interests and timing, and share good practices among levels of government.

Ad hoc/informal meetings: Between representatives of different levels of government to facilitate dialogue and horizontal, vertical and cross-disciplinary networks, and complement formal mechanisms.

Performance measurement: Using indicators to measure the inputs, outputs and outcomes of a public service, and monitor and evaluate public service provision.

Experimentation and pilot projects: Trying governance mechanisms for a defined time and/or area to learn what is effective in a given context.

Source: Charbit and Michalun (2009[11]), “Mind the Gaps: Managing Mutual Dependence in Relations among Levels of Government”, OECD Working Papers on Public Governance, No. 14, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/221253707200.

Table 5.2. Adult learning objectives established in Tlaxcala’s State Development Plan (PED) (2017-2021)

Objectives organised by priority area and topics

|

Employment, economic development and prosperity for families |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Objectives |

Strategies |

Lines of action |

|

|

Employment |

1.1 Boosting economic growth and investment in the state. |

1.1.1 Promote the competitive advantages of the state nationally and internationally to attract greater national and foreign private investment. |

1.1.1.3 Promote a better alignment of the supply of human capital appropriate to the development needs of the local industry. |

|

1.2 Generating more and better paid jobs. |

1.2.1 Improve employment conditions and opportunities for the state's population. |

1.2.1.2 Develop vocational skills and competencies of the working aged population through training to increase their job opportunities and income. |

|

|

1.2.1.3 Strengthen the link between secondary and higher education institutions with the state productive sector to generate an adequate supply of human capital to meet the needs of local industry. |

|||

|

Competitiveness |

1.4 Raise competitiveness by supporting human capital development. |

1.4.1 Develop Tlaxcalan talent that is oriented to the needs of the productive sectors of the state. |

1.4.1.1 Promote the alignment of the intermediate, higher educational offer with the human capital needs of the state productive sector. |

|

1.4.1.2 Develop training and skills development schemes for the working age population. |

|||

|

Agriculture, livestock and rural development |

1.7 Strengthen the integral and sustainable development of the rural sector through programmes that increase the productivity and well-being of farm workers and their families. |

1.7.1 Strengthen federal and state programmes to support the rural sector. |

1.7.1.2 Strengthen state programmes designed to raise the productivity of small production units (farms). Implement these programmes through a strategy that prioritises collaborative work and the integration of value chains, and encourage the identification and channeling of resources to rural projects with higher profit potential. |

|

1.8 Generate employment and development opportunities in the agricultural, livestock and aquaculture sectors that raise the living conditions of the rural population. |

1.8.1 Develop agricultural production chains that favour the creation of added value and commercialisation. |

1.8.1.2 Provide training and technical assistance to add value to agricultural, livestock and aquaculture products. |

|

|

Tourism |

1.10 Improve the tourist competitiveness of Tlaxcala. |

1.10.2 Improve the skills and productivity of tourist sector workers. |

1.10.2.2. Increase the supply of training and the training of specialised skills and abilities for the tourism sector. |

|

Relevant education, quality health and inclusive society |

|||

|

Education |

2.8. Link education with the labor market. |

2.8.1. Bring the state education system closer to the labour market. |

2.8.1.1 Upskill and reskill workers to better align skills supply and demand. |

|

2.8.1.2 Encourage the acquisition of basic skills, including the command of other languages, to compete in a globally competitive job market. |

|||

|

2.8.2 Strengthen education business co‑operation to promote the updating of study plans and programmes, the employability of young people, and innovation. |

2.8.2.6. Formally recognise the skills acquired at work or through informal learning. |

||

|

2.9. Facilitate education policy co‑ordination |

2.9.1 Improve co‑ordination and interaction between the public, private and social sectors for the benefit of education. |

2.9.1.5. Promote greater co‑operation between the public, private and social sectors in the design and implementation of higher secondary education curricula to improve the link between educational and productive sectors. Promote the certification and accreditation of learning. |

|

Note: This table has been compiled by the OECD for the purpose of this project.

Source: Government of Tlaxcala (2017[12]), State Development Plan of Tlaxcala 2017-2021.

In Tlaxcala, there are two main legal mechanisms that facilitate vertical co‑ordination in adult learning. First, the State Development Plan (Plan Estatal de Desarrollo, PED) is an instrument that facilitates vertical co‑ordination across different levels of government in Mexico. Key objectives and strategies of the PED need to be aligned with those of the National Development Plan (Plan Nacional de Desarrollo). The PED outlines the objectives, policies and required resources across Tlaxcala’s priority policy objectives, which include employment, competitiveness, rural development, tourism and education. All five objectives of the PED include actions related to the promotion of adult learning (Table 5.2).

Second, the Municipality Law of the State of Tlaxcala obliges all municipalities to formulate a municipal development plan (plan de desarrollo municipal, PDM) within the first four months of the creation of a new municipal government. The plan should then be implemented during municipal governments’ three-year term. The purpose of the PDM is to identify municipalities’ key policy and resource challenges and needs, and communicate them to the state government to solicit relevant support. Once the plans have been formulated, the city council of each municipality uploads them to the municipality website. PDMs submitted to the state government are delivered to the Senior Government Office (Oficialía Mayor de Gobierno) and published in the official state newspaper.

The Municipal Law of the State of Tlaxcala and the Political Constitution of the United Mexican States stipulate that municipalities should develop PDMs in alignment with the State Development Plan (PED). However, municipalities face significant challenges in aligning their PMDs to Tlaxcala’s PED, which weakens the co‑ordination potential of PED in relation to adult learning. As shown in Table 5.2, the strategies and lines of action presented in the PED regarding adult learning are described only very generally and do not clearly define the roles and responsibilities of relevant actors. The lack of clarity in adult learning objectives and in the delineation of roles and responsibilities at the state level make it difficult for municipalities to design PMD adult learning strategies in line with PED goals. Korea presents a relevant example of a set of plans dedicated specifically to adult learning that clearly define the roles and responsibilities of relevant actors. Under Korea’s Lifelong Learning Act, the national government develops the Lifelong Learning Promotion Plan, which serves as the basis for state- and municipal-level lifelong learning promotion basic plans and lifelong learning promotion implementation plans (Box 5.2) (Government of Korea, 2021[13]).

Box 5.2. Relevant international example: Korea’s Lifelong Learning Promotion Plan at national, state and municipal levels

Under the Lifelong Education Act, the Ministry of Education of Korea has developed a National Lifelong Education Promotion Basic Plan every five years since 2002. The current Lifelong Education Promotion Basic Plan (2018‑2022) provides overall objectives for mid- to long-term lifelong education policies with an aim to build a sustainable environment for lifelong education across the nation. The plan, which targets mainly adults and vulnerable youth, introduces strategies, initiatives and a corresponding budget plan to promote the proposed policy objectives, and clearly identifies relevant actors. The policy objectives of the plan include:

Increase participation in lifelong education through enhanced training leave, effective career guidance, better recognition of prior learning, tailored support for multicultural families and more support to women for re-entry into the labour market (Ministry of Education, Ministry of Employment and Labour, Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, and others).

Provide more tailored support for vulnerable groups through increased access to literacy education and high-quality e‑learning, provision of financial allowances to participate in lifelong learning, and tailored learning programmes for disabled citizens (Ministry of Education, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Financial Services Commission, and others).

Increase adult learning opportunities for workers by providing more vocational education through MOOC (massive open online courses), engaging more employers in public education and training design, and promoting the increased provision of adult learning and vocational training through higher education institutions (Ministry of Education and Ministry of Employment and Labour).

Encourage community-based lifelong learning by promoting lifelong learning cities, increasing lifelong learning opportunities through local lifelong learning centres, and supporting tailored lifelong learning programmes that reflect local demands (Ministry of Education, Ministry of SMEs and Start-ups).

Strengthen the lifelong learning environment by bolstering legal frameworks and vertical co‑ordination mechanisms, improving the quality of lifelong learning statistics, and increasing public expenditure in lifelong learning (Ministry of Education and Ministry of Economy and Finance).

Once the five-year National Lifelong Education Promotion Basic Plan has been established, state- and municipal-level governments are obliged to develop their own lifelong education promotion basic plans and annual lifelong education promotion implementation plans in close alignment with the prescribed objectives, strategies and initiatives proposed by the national-level plan. These plans are then submitted for review to the Lifelong Education Promotion Councils established at both state and municipal levels to promote lifelong learning and facilitate lifelong learning policy co-ordination.

Source: OECD (Forthcoming[14]), Skills Strategy Report for Korea: Governance Review; Government of Korea (2021[13]), Lifelong Education Act.

A comparison between the PED and Tlaxcala’s 53 publicly accessible PMDs demonstrates numerous cases of misalignment (Table 5.3). Analysis based on these cases of misalignment reveals that the percentage of municipalities with a misalignment between the PMD and the PED reaches 92% in the tourism priority area, followed by competitiveness (78%), rural development (55%), education (43%) and employment (17%). Considering that adult learning is a horizontal topic that cuts across all objectives of the PED, this lack of alignment seems to undermine the PED’s potential to foster co‑ordinated adult learning policy provision at the municipal level. In addition, the PED does not have any objectives related to adult learning as remedial education, which is highlighted in most (32 out of 53) of the PMDs.

Table 5.3. Alignment between the PED and PMD in priority policy areas

Priority areas of PMD that are aligned (blue) or misaligned (white) with PED

|

Municipality |

Employment |

Competitiviness |

Rural development |

Tourism |

Education |

Municipality |

Employment |

Competitiviness |

Rural development |

Tourism |

Education |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Amaxac de Guerrero |

|

|

|

|

|

Tetla de la Solidaridad |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Atlangatepec |

|

|

|

|

|

Tetlatlahuca |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Atltzayanca |

|

|

|

|

|

Tlaxcala |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Apizaco |

|

|

|

|

|

Tlaxco |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

El Carmen Tequexquitla |

|

|

|

|

|

Tocatlán |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cuapiaxtla |

|

|

|

|

|

Totolac |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Cuaxomulco |

|

|

|

|

|

Zitlaltepec de Trinidad Sánchez Santos |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chiautempan |

|

|

|

|

|

Tzompantepec |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Muñoz de Domingo Arenas |

|

|

|

|

|

Xaloztoc |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Españita |

|

|

|

|

|

Xaltocan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hueyotlipan |

|

|

|

|

|

Papalotla de Xicohténcatl |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ixtacuixtla de Mariano Matamoros |

|

|

|

|

|

Xicohtzinco |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ixtenco |

|

|

|

|

|

Zacatelco |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mazatecochco de José María Morelos |

|

|

|

|

|

Benito Juárez |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Contla de Juan Cuamatzi |

|

|

|

|

|

Emiliano Zapata |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tepetitla de Lardizábal |

|

|

|

|

|

La Magdalena Tlaltelulco |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nanacamilpa de Mariano Arista |

|

|

|

|

|

San Damián Texoloc |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Acuamanala de Miguel Hidalgo |

|

|

|

|

|

San Francisco Tetlanohcan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Natívitas |

|

|

|

|

|

San Jerónimo Zacualpan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Panotla |

|

|

|

|

|

San José Teacalco |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

San Pablo del Monte |

|

|

|

|

|

San Juan Huactzinco |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Santa Cruz Tlaxcala |

|

|

|

|

|

San Lorenzo Axocomanitla |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tenancingo |

|

|

|

|

|

Santa Ana Nopalucan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Teolocholco |

|

|

|

|

|

Santa Apolonia Teacalco |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tepeyanco |

|

|

|

|

|

Santa Catarina Ayometla |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Terrenate |

|

|

|

|

|

Santa Cruz Quilehtla |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Santa Isabel Xiloxoxtla |

|

|

|

|

|

Note: Blue cells imply that the given municipality’s PMD was aligned with the PED under that priority area. Municipalities in bold highlight the need for better co‑ordination between state and municipal institutions and programmes regarding adult learning.

Source: This table has been created by the OECD for the purposes of this project based on the state and municipal development plans.

Tlaxcala’s legal instruments (PED, PMD) for the vertical co‑ordination of adult learning are complemented by several co‑ordinating bodies. ICATLAX and ITEA, operating at the state level, run a number of training units at the municipal level, which act as co-ordinating bodies to facilitate collaboration and co‑ordination in adult learning provision between the state and municipalities. However, these training units only exist in a limited number of municipalities. For example, ICATLAX currently has nine training units and one mobile unit across ten municipalities – Calpulalpan, Chiautempan, Huamantla, San Pablo del Monte, Tepetitla, Tetla, Tetlanohcan, Tlaxco, Zitlaltepec and Papalotla. Out of these ten training units, seven are located in Tlaxcala’s most populated municipalities, implying that in less populated areas, mechanisms for co‑ordinating the provision of adult learning are relatively weaker.

A lack of co-ordination between the state and municipalities can create several challenges in the provision of adult learning, such as overlaps of adult learning programmes between the state and municipalities. It can also weaken municipalities’ understanding of adult learning priorities set out at the state level (e.g. through the PED), resulting in misinterpretation or diverging interpretations of Tlaxcala’s adult learning goals. Conversely, the lack of co‑ordination can diminish the state’s understanding of the specific challenges that each municipality may face when putting state-level adult learning goals into practice. Such a lack of understanding can deprive the state of the opportunity to benefit from on-the-ground feedback on adult learning policy design, which could guide the provision of necessary support to municipalities. Tlaxcala has established relatively effective co-ordination mechanism regarding its financial policies (Box 5.3). Under the Financial Co-ordination Law for the State of Tlaxcala and its Municipalities (Ley de Coordinacion Hacendaria para el Estado de Tlaxcala y sus Municipios), Tlaxcala provides relevant support to municipalities based on effective co-ordination mechanisms.

Box 5.3. Relevant national example: Co-ordination between the state of Tlaxcala and its municipalities for financial policies

In the context of growing financial decentralisation, the state of Tlaxcala has developed structured co‑ordination mechanisms to facilitate effective co‑ordination between the state and municipalities in the area of financial policies. Under the Financial Co-ordination Law for the State of Tlaxcala and its Municipalities, the state established co‑ordination measures to support municipalities in financial policy design and implementation.

First, the state of Tlaxcala operates the State Tax Co‑ordination System to identify municipalities that have particular needs for additional financial resources. This serves as an important instrument to allocate the state’s financial resources equitably across municipalities. Second, the state of Tlaxcala developed clear definitions of the roles and responsibilities of relevant actors (i.e. State Congress, State Executive and municipalities), a range of financial resources, and types of decrees and ordinances related to financial co‑ordination between the state and municipalities. Clear definitions of related actors and instruments help promote effective co‑ordination between the state and municipalities in terms of the administration, collection, surveillance and evaluation of public spending. Third, the state of Tlaxcala promotes citizen participation at state and municipal levels in decision making related to public financial programmes and projects. Lastly, municipalities that do not have sufficient capacity and administrative infrastructure to comply with actions required by the financial co‑ordination mechanism can sign agreements with the state of Tlaxcala to receive administrative support, including technical support in computing, the preparation of financial programmes, and planning, and intervention in administration procedures.

Source: Government of Tlaxcala (1999[15]) Financial Co-ordination Law for the State of Tlaxcala and its Municipalities https://normas.cndh.org.mx/Documentos/Tlaxcala/Ley_CHE_Tlax_Tlax.pdf.

Recommendations for promoting vertical co-ordination in adult learning between the state and municipalities

5.1 Foster better alignment between the State Development Plan (PED) and municipal development plans (PMD). First, Tlaxcala should more clearly define adult learning objectives and the roles and responsibilities of relevant actors in the PED to provide a good example and better guidance to Tlaxcalan municipalities in the development of their PMDs. A standardised structure for PMDs should be prescribed by the state to enable comparison across municipalities in terms of content and level of alignment with the PED. Second, Tlaxcala should take concrete follow-up actions once PMDs have been delivered. Once submitted to the Senior Government Office, designated personnel in the office, supported by the Higher Inspection Body (Órgano de Fiscalización Superior, OFS), could evaluate the alignment of adult learning policies and programmes between the PED and PMDs, communicate the results and provide feedback to municipalities.

5.2 Establish designated focal points in each municipality to co‑ordinate the activities of the state and municipalities in the area of adult learning. Officials from ICATLAX or ITEA could be designated as focal points in municipalities where they are present. In municipalities where ICATLAX and ITEA do not have a presence, the focal point could be an official from SEP Tlaxcala education units or other departments (i.e. Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, Department of Environment and Natural Resources). In some municipalities, these departments have a physical presence and provide technical and vocational education in specific areas. Using their knowledge about local skills needs and facilities (i.e. local offices, centres or buildings), these departments could act as focal points and provide more adult learning opportunities in relevant areas in collaboration with municipal and state governments, as well as ICATLAX and ITEA. Lastly, the focal points could take responsibility for leading co‑ordination between the PED and PMDs at the municipal level. By liaising with the Senior Government Office and the Higher Inspection Body, the focal point could also promote the exchange of feedback between the state and municipalities and facilitate the state’s provision of consulting and incentives to municipalities when needed.

Strengthening adult learning impact evaluation mechanisms

The appropriate ex post impact evaluation of policy interventions is key to assessing the effectiveness of public policies, and is widely regarded as a means to improve their quality. Impact evaluation can help determine if a policy intervention has reached the objectives it aimed to achieve. Effective impact evaluation provides important evidence to improve governance, as policy makers can reassess the roles and responsibilities of relevant actors, improve policy co‑ordination, and reallocate financial resources based on evaluation results. Ex post impact evaluations should be embedded in the process of designing and implementing policies (OECD, 2016[16]).

Effective ex post impact evaluation in adult learning can assess whether adult learning programmes have produced expected learning outcomes, and whether financial resources have been distributed efficiently (OECD, 2020[17]; OECD, 2019[18]). In this way, robust evaluation mechanisms can help sustain momentum to support strongly performing adult learning programmes across electoral cycles, and therefore contribute towards maintaining a long-term, co‑ordinated vision of the adult learning system.

At the national level, Mexico’s National Council for the Evaluation of Social Development Policy (Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social, CONEVAL) conducts a Diagnosis of Advances in Monitoring and Evaluation in Federal Entities (Diagnóstico del avance en monitoreo y evaluación en las entidades federativas) (CONEVAL, 2019[19]). This diagnosis has been carried out biennially since 2011 to assess the performance of Mexican states in evaluating their social policies and programmes (Box 5.4). The objective of the diagnosis is to compare states’ overall performance in policy monitoring and evaluation.

Box 5.4. The monitoring and evaluation index of CONEVAL

The monitoring and evaluation index, through the diagnosis of monitoring and evaluation progress in the states, identifies progress on the issuance of regulations and the implementation of monitoring and evaluation of social development policy and programmes.

The index has nine relevant areas of analysis that are organised in four levels of disaggregation:

1. Normative and practical components: Normative component refers to the regulations issued by federal entities in several areas of analysis, such as social development law, registry of beneficiaries and criteria of evaluation. Practical component refers to the implementation of these areas.

2. Elements: This involves nine areas of analysis: 1) the existence and scope of the Social Development Law, or equivalent; 2) criteria for the creation of new programmes; 3) creation of a list of beneficiaries; 4) preparation of operating rules or equivalent; 5) dissemination of programme information; 6) transparency in the budget; 7) monitoring and evaluation elements; 8) performance and management indicators; and 9) area responsible for conducting evaluation.

3. Variables: This involves 27 variables: 14 regarding the normative component and 13 regarding the practical component.

4. Criteria: This considers 154 criteria related to the characteristics evaluated in each variable.

Source: CONEVAL (2019[19]), Diagnosis of Advances in Monitoring and Evaluation in Federal Entities 2019, https://www.coneval.org.mx/InformesPublicaciones/Documents/Diagnostico_2019.pdf.

At the state level, Tlaxcala conducts ex post evaluation of its policy interventions through the Annual Programme of Evaluation (Plan Annual de Evaluación, PAE) led by the Technical Directorate of Performance Evaluation (Dirección Técnica de Evaluación del Desempeño, DTED) at the Department of Planning and Finance (Secretaría de Planeación y Finanzas del Gobierno, SPF) (CONEVAL, 2019[19]). The objective of the PAE, which is conducted across all states in Mexico, is to evaluate the performance of federally funded programmes and to use the results as input for “results-based budgeting”, a technique that encourages the planning of public expenditure based on measurable results of interventions (CONEVAL, 2019[19]).

The PAE uses indicators and methodologies established by CONEVAL. The effectiveness and efficiency of adult learning programmes in Tlaxcala are assessed through the evaluation of three programmes: the Contribution Fund for Technological and Adult Education (FAETA), the Care Agreement for the Demand for Adult Education (CADEA) and Supérate. FAETA evaluation covers adult learning programmes provided by ITEA and the College of Technical Professional Education of the State of Tlaxcala, while CADEA evaluation only covers ITEA programmes. The PAE for federally funded programmes conducts: 1) assessment of programme design; 2) assessment of programme process; 3) assessment of specific performance; 4) evaluation of indicators; 5) assessment of consistency and results; 6) integral evaluation; and 7) impact evaluation (Table 5.4) (Government of Tlaxcala, 2017[20]).

Table 5.4. Types of evaluation used in the Annual Programme of Evaluation (PAE)

|

Category |

Indicators |

|---|---|

|

1. Programme design |

|

|

2. Programme process |

|

|

3. Specific performance |

|

|

4. Evaluation of indicators |

|

|

5. Programme consistency and results |

|

|

6. Integral evaluation |

|

|

7. Impact evaluation |

|

Source: Government of Tlaxcala (2017[20]), Annual Programme of Evaluation, https://www.septlaxcala.gob.mx/programa_anual_evaluacion/2017/pae_2017.pdf.

There are several challenges in using the PAE to evaluate the performance of adult learning programmes in Tlaxcala. First, only adult learning programmes provided by ITEA (under FAETA and CADEA), the College of Technical Professional Education of the State of Tlaxcala (under FAETA) and Supérate are evaluated under the PAE. This means that a large proportion of Tlaxcalan adult learning programmes provided by ICATLAX are currently not subject to any evaluation. Second, the adult learning programmes provided under FAETA, CADEA and Supérate, which are evaluated under PAE, have never been subject to an impact evaluation (Table 5.5). The evaluation of programme consistency and programme results is also carried out on an irregular basis (Table 5.5), which makes it challenging to verify whether the results of the evaluation from the previous year have been reflected in the following year’s programme design.

Table 5.5. Types of PAE evaluation used for selected federally funded budget programmes

Types of evaluations conducted for FAETA, CADEA and Supérate between 2015 and 2020

|

Programme (year) |

Evaluation type |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Programme design |

Programme process |

Specific performance |

Indicators |

Consistency and results |

Integral evaluation |

Impact evaluation |

|

|

ETA (2020) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

X |

- |

- |

|

FAETA (2019) |

- |

X |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

FAETA (2018) |

- |

- |

X |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

FAETA (2017) |

- |

- |

X |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

FAETA (2016) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

X |

- |

- |

|

FAETA (2015) |

- |

- |

- |

- |

X |

- |

- |

|

CADEA (2020) |

- |

- |

- |

X |

- |

- |

- |

|

CADEA (2019) |

X |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

CADEA (2018) |

X |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

|

Supérate (2020) |

X |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

Note: CADEA and Supérate were initiated in 2017 and 2019 respectively. “x” indicates that the particular type of evaluation was conducted for the corresponding budget programme in the given year whereas “-“ indicates that the particular type of evaluation was not conducted.

Source: Government of Tlaxcala (2020[21]), Consistency and Results Evaluation of the Contributions Fund for Technological and Adult Education (FAETA): Fiscal Year 2019.

The indicators used to assess programme consistency and results tend to measure participation in or the completion of adult learning, rather than examine the impact generated from the participation in or completion of adult learning programmes (Table 5.6).

Table 5.6. Indicators used for the evaluation of “programme consistency and results” in the PAE

Based on indicators used for FAETA evaluation (2020)

|

Category |

Indicators |

|---|---|

|

Goal |

|

|

Purpose |

|

|

Component |

|

|

Activities |

|

Source: Government of Tlaxcala (2020[21]), Consistency and Results Evaluation of the Contributions Fund for Technological and Adult Education (FAETA): Fiscal Year 2019.

Irregular results evaluation that relies simply on participation or completion rates may prevent the analysis of mid- to long-term impacts of adult learning programmes, which is critical for evidence-based policy making and the continued provision of strongly performing adult learning programmes. Within the current PAE framework, only one type of evaluation can be undertaken per year, which may restrict the inclusion of impact evaluation when there is particular need for another type of evaluation for the given year. In the case of FAETA, there was a three-year gap (2017‑2019) in such evaluation. For CADEA, consistency and results evaluation has never been conducted, despite being in place since its initiation in 2017.

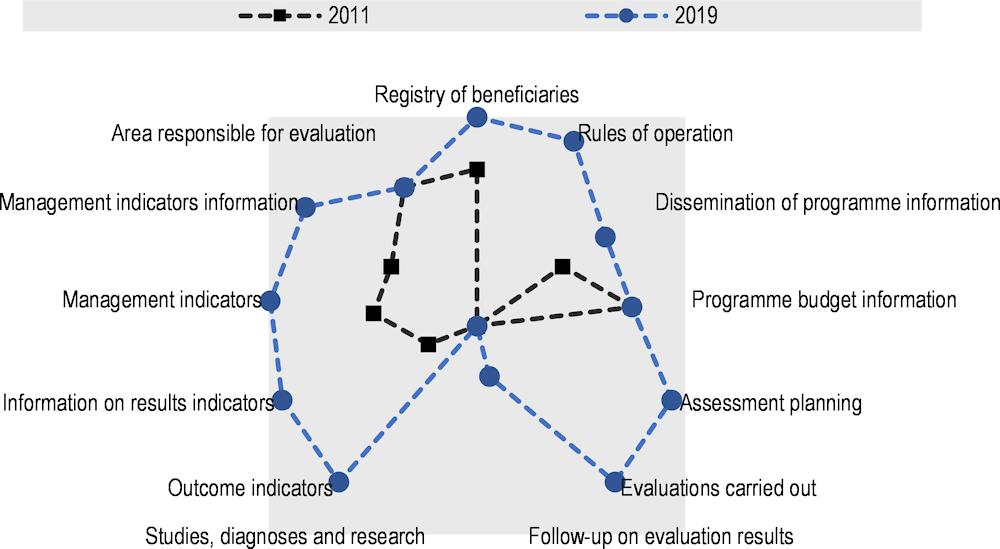

Tlaxcala has room for improvement in following up on evaluation results. According to the Diagnosis of Advances in Monitoring and Evaluation in Federal Entities conducted by CONEVAL, Tlaxcala has made advances in many components of the diagnosis, but its performance remains weak regarding follow-up on evaluation results (Figure 5.3). This can partly be explained by the lack of PAE guidelines, which would suggest concrete steps and follow-up actions. Each PAE report identifies Susceptible Aspects for Improvement (Aspectos Susceptibles de Mejora, ASM), which refers to areas where follow-up actions are deemed necessary (Government of Tlaxcala, 2020[21]). The PAE then allocates five months for relevant actors to address the ASMs. However, the PAE does not provide a clear set of procedures to facilitate the follow-up of identified recommendations, as done, for instance, by Chile’s Evaluation and Management Control System (SECG) (Box 5.5).

Figure 5.3. Change in Tlaxcala’s performance in selected PAE components (2011 and 2019)

Note: The scores indicate the relative performance of the state of Tlaxcala in 2011 (black squares) and 2019 (blue circles) on the selected components of PAE on the scale of 0 (worst) to 4 (best) (normalised scores). Being further away from the core of the chart indicates better performance. For example, the component “Registry of beneficiaries” had a high score (4) in 2019, which indicates that Tlaxcala performed well and had improved from its previous score (3) recorded in 2011.

Source: CONEVAL (2019[19]), Diagnosis of Advances in Monitoring and Evaluation in Federal Entities 2019,

https://www.coneval.org.mx/InformesPublicaciones/Documents/Diagnostico_2019.pdf.

The absence of impact evaluation for adult learning programmes, coupled with inadequate follow-up actions, limits the extent to which evaluation can support evidence-based policy making in Tlaxcala. However, several positive developments can help Tlaxcala address these challenges. For example, the latest FAETA evaluation report recommends conducting impact evaluations of the FAETA budget (Government of Tlaxcala, 2020[21]), which can help build momentum to initiate impact evaluations of FAETA-financed adult learning programmes.

Box 5.5. Relevant international example: Chile’s Evaluation and Management Control System

Chile’s Evaluation and Management Control System (SECG) is an initiative administered by the Chilean Budget Office of the Ministry of Finance (DIPRES).

SECG includes four types of ex post evaluation for public policy programmes and institutions: 1) evaluation of governmental programmes (evaluación de programas gubernamentales, EPG); 2) impact evaluation (evaluación de impacto, EI); 3) evaluation of institutional cost (evaluación del gasto institucional, EGI); and 4) evaluation of new programmes (evaluación programas nuevos, EPN).

The main objective of the EI line of work is to evaluate the effectiveness of public policy programmes and the intermediate and final results for the beneficiaries through quasi-experimental methodologies. The evaluations require field research to gather programme information. They are carried out by external evaluation entities, either universities or consulting firms, which are selected through a public tender.

The evaluation process lasts approximately 18 months. In the interim period, preliminary reports are delivered. The final evaluation report contains the evaluation results and recommendations that the panel proposes to overcome the shortcomings detected during the evaluation.

The recommendations formulated by the evaluators are analysed in the Ministry of Finance together with the institutions responsible for the programmes evaluated to specify how they will be incorporated, identify the leader for such efforts (ministry, other public institutions), and identify the possible legal and resource restrictions. The final product consists of formally establishing institutional commitments to incorporate recommendations in each of the programmes evaluated. These commitments constitute the basis for monitoring the performance of the programmes.

Since the beginning of the evaluations, DIPRES has requested a permanent interlocutor within each ministry. In the Ministry of Education, this responsibility is assumed by the Division of Planning and Budgets (DIPLAP). The main objective of DIPLAP is to co‑ordinate the entire programme evaluation process carried out by DIPRES. DIPLAP’s tasks include ensuring the adequate participation of the ministry from the beginning of the programme evaluation process and providing technical support and advice where relevant.

Between January and August 2016, an Impact Evaluation of the Education Programme for Youth and Adults (Programa educación para personas jóvenes y adultas) was completed under SECG. The final report of approximately 150 pages contained conclusions regarding the quality and cost-efficiency of the programme, together with concrete policy recommendations.

Source: Ministry of Education (2021[22]), Chilean Budget Office of the Ministry of Finance (DIPRES) Evaluation, https://centroestudios.mineduc.cl/evaluaciones-dipres/una-evaluacion-dipres/.

Recommendations for strengthening adult learning evaluation mechanisms

5.3 Expand the implementation of impact evaluation for adult learning programmes. Tlaxcala’s Annual Programme of Evaluation (PAE) should conduct impact evaluations of adult learning programmes provided by FAETA, CADEA and Supérate. Indicators for impact evaluation will first need to be set. The PAE could consider adopting mid- to long-term indicators for “perceived impact” established under the OECD Priorities for Adult Learning (PAL), which seek to assess the readiness of adult learning systems to respond to the challenges of changing skill needs (i.e. usefulness of training use of acquired skills, impact on employment outcomes, and wage returns to adult learning). Similar to Chile’s SECG (Box 5.5), PAE impact evaluation should be composed of a structured set of deliverables (i.e. preliminary report, final report with recommendations, follow-up on the recommendations). Once the impact evaluation has been initiated it should be conducted in a regular and sustained manner to produce adequate data to inform evidence-based policy making. As adult learning programmes provided by ICATLAX are not included in the PAE, a dedicated unit for adult learning evaluation could be established in the Directorate for Education Evaluation (Dirección de Evaluación Educativa, DEE) at SEP Tlaxcala. The unit would be tasked with carrying out the impact evaluation of adult learning programmes provided by ICATLAX using the same criteria applied by FAETA, CADEA and Supérate in the impact evaluation of the PAE. In order to ensure comparability across evaluations, DEE could use a set of indicators for impact evaluation similar to those proposed for use under the PAE. As successful evaluations depend on high-quality data collected from monitoring, adult learning providers (i.e. ICATLAX, ITEA) should be required to monitor and accumulate on an ongoing basis data on indicators that will be used for impact evaluation.

5.4 Utilise the results of the evaluations of adult learning programmes to inform evidence-based policy making process. The Technical Directorate of Performance Evaluation (Dirección Técnica de Evaluación del Desempeño, DTED) of the SPF could be tasked with not only publishing the results of evaluations and ASMs, but also following up with relevant institutions to hold them accountable to deliver on the ASMs identified by the PAE. The designated unit in DEE (see Recommendation 5.3) could also be responsible for publishing the results of its impact evaluations on adult learning programmes and following up on the recommendations produced. Similar to Chile’s DIPRES (Box 5.5), the DTED and DEE could lead efforts in analysing the recommendations for improvement, following up on the implementation of the recommendations, and identifying possible legal and resource constraints that need to be addressed. An interlocutor could be assigned in each relevant institution involved in adult learning to facilitate the efforts of the DTED and DEE.

Opportunity 2: Maximising the potential of skills data to strengthen skills assessment and anticipation exercises

Mobilising skills data and maximising their potential allows countries to effectively generate information about the current and future skills needs of the labour market (skills demand) and the available skills supply (OECD, 2016[23]). Engaging in such skills assessment and anticipation (SAA) exercises contributes to making skills systems more responsive and empowers policy makers to respond swiftly to reduce costly skills imbalances (see Chapter 2). More countries are taking steps to develop robust SAA exercises to foster a better alignment between skills supply and demand (OECD, 2016[23]).

In the context of structural changes brought about by the COVID‑19 pandemic and the USMCA agreement, Tlaxcala’s ability to thrive in the post‑pandemic context will depend on its ability to effectively respond to changing labour market developments. Because of the worsening economic situation induced by the pandemic, many displaced workers will require adequate reskilling and upskilling. The USMCA agreement is likely to further magnify the relative importance of certain Tlaxcalan sectors, which will put pressure on Tlaxcala’s education and training system to keep up with changes to the economic structure of the state. The capacity to assess and anticipate current and future skills needs is likely to become a crucial cornerstone of Tlaxcala’s policy making in the years to come.

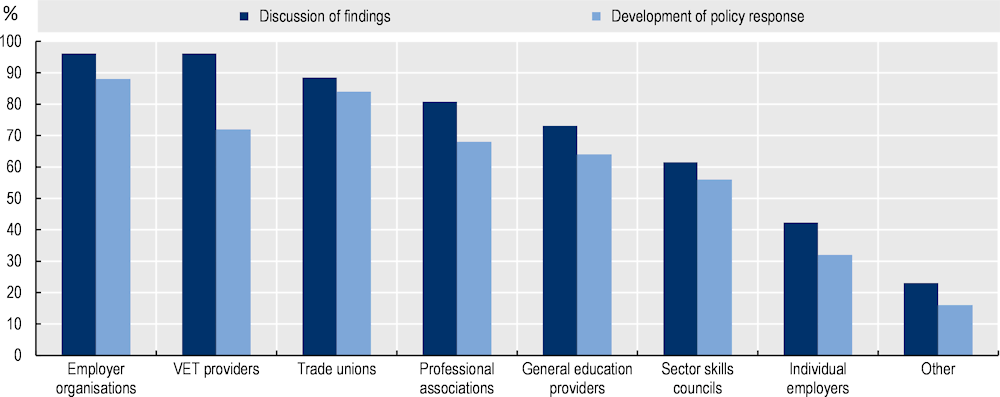

SAA exercises exist in almost all OECD countries. They can differ in various ways: 1) definition of skills and proxies used to measure them (education qualifications, fields of study, specific skills); 2) coverage (national, regional or sectoral exercises); 3) time span (current assessment vs, short-, medium- or long-term forecasts); and 4) methods used (quantitative or qualitative). However, all skills data is put to the most effective use in policy making when there is good co‑ordination across the whole of government, and strong stakeholder involvement (OECD, 2016[23]).

Tlaxcala should use a rich variety of skills data for assessing and anticipating changing skills needs, and continue its efforts to maximise its potential, by:

Bolstering the analytical foundations and results dissemination of skills assessment and anticipation exercises.

Strengthening stakeholder engagement in consolidating, analysing and validating the findings from skills assessment and anticipation exercises, and advising policy makers.

Bolstering the analytical foundations and results dissemination of skills assessment and anticipation exercises

Effective and impactful SAA exercises rely on the high-quality analysis of skills needs before the results of such analyses are consolidated and disseminated to relevant target groups. Strong analytical foundations of SAA exercises (i.e. robust data collection, data processing, data analysis and data linkages) enable the more accurate and reliable diagnosis and projection of skills needs. At the same time, communicating the results of SAA exercises to the public allows individuals (jobseekers, individuals in need of training, young people weighing their study choices) to make decisions aligned with the needs of the labour market.

Tlaxcala uses both federal and state sources of skills data to keep track of its supply and demand of skills, as indicated in Figure 5.2 above. Interviewed stakeholders commented that the co‑ordination of data exchange between state and federal entities is one of the key challenges in effectively assessing and anticipating Tlaxcala’s skills needs. The vacancy data gathered in the Information System of the National Employment Service (SIISNE), operated by National Employment Service Unit (USNE), cannot be readily accessed by the National Employment Service of Tlaxcala (SNET). Instead, USNE sends reports to state-level employment services with aggregate data for the previous month during the first fifteen days of the current month. Stakeholders in Tlaxcala highlighted that USNE reports do not always arrive on time. If a data request from a state-level entity in Tlaxcala arises in between the officially delineated periods when USNE sends the vacancy reports, the process for obtaining the data is lengthy and cumbersome. To request the data, an official letter signed by the Director of SNET indicating what type of data is required and why the data are needed has to be sent to USNE, and the response can take up to ten days. Therefore, it is difficult for Tlaxcala to make short-term projections about its skills needs based solely on results supplied at the federal level, where the data are handled and inaccessible to state-level entities.