This chapter compares the tax structure in Chile with the OECD average. The chapter also considers the role of some relatively atypical features of the tax structure in Chile including Social Security Contributions and compulsory contributions to the private sector. Selected tax rates in Chile are also compared with the OECD average to add context to the tax structure discussion.

OECD Tax Policy Reviews: Chile 2022

3. Tax structures

Abstract

Chile’s tax structure differs significantly from the OECD average, it is more concentrated in VAT and CIT revenues and less so in PIT and SSC revenues

Tax revenues in Chile are relatively low. Chile’s tax-to-GDP was 20.7% in 2019, substantially below the OECD average rate of 33.8% in 2019 (33.9% in 2018). Consequently, relative to the size of its economy (measured by GDP), Chile raises tax revenues of about 60% of the OECD average.

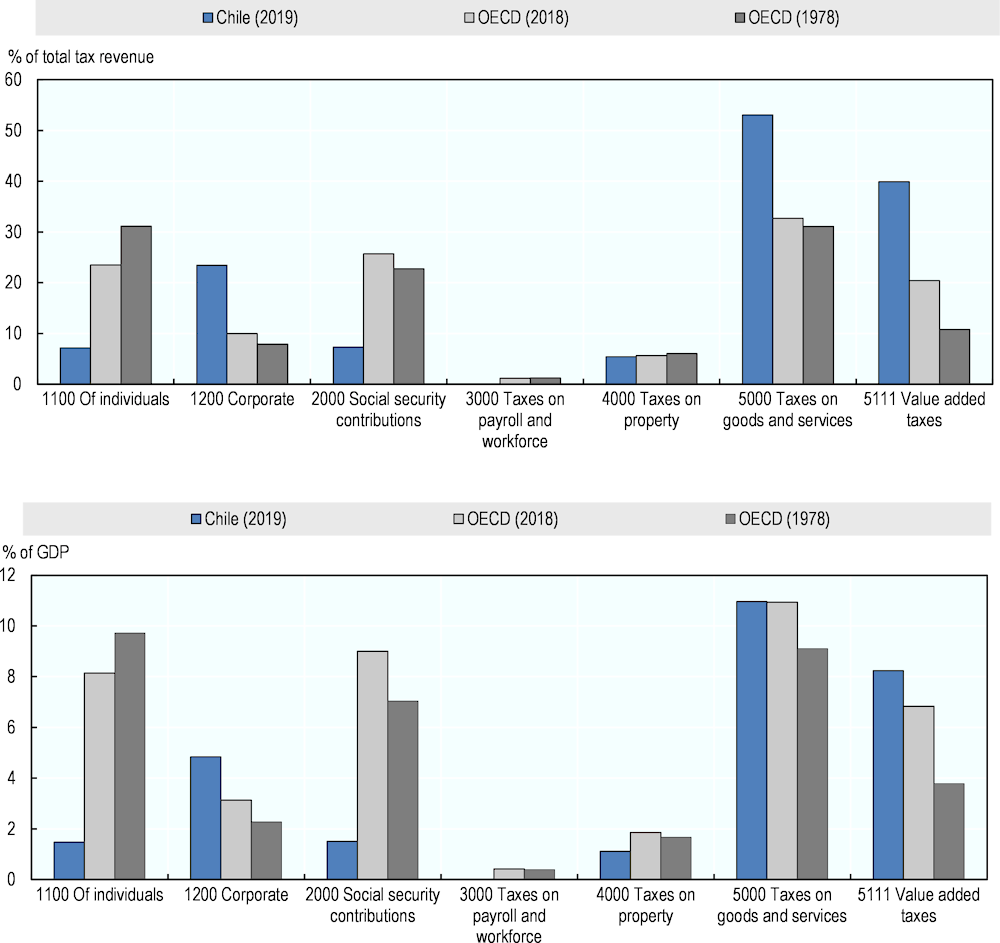

Tax revenues in Chile are concentrated in VAT and CIT. As shown in Figure 3.1, taxes on goods and services represent over half of total tax revenues (53.1%) in Chile in 2019, compared to about one-third (32.7%) in the OECD in 2018 (VAT represents 39.9% of total tax revenues in Chile, compared to 20.4% in the OECD). CIT revenues as a share of total tax revenues were 23.4% in Chile in 2019, compared to 10% among OECD countries. Combined, VAT and CIT revenues in Chile represent more than three-quarters of total tax revenues, compared to less than half among OECD countries. When compared as a share of GDP, VAT and CIT in Chile were 8.2% and 4.8% respectively in 2019, which are both above the OECD average of 6.8% and 3.1% in 2018. On the other hand, PIT and SSCs and taxes on payroll play a much smaller role in Chile. For example, PIT and SSCs as a share of GDP in Chile both represent 1.5% in 2019, which is significantly below the OECD average of 8.1% and 9.0% respectively in 2018. Higher income OECD countries generally depend more heavily on PIT and SSCs than in Chile. Chile’s relatively high concentration in CIT and relatively low concentration in PIT has various causes, including Chile’s partial dividend imputation tax system under which the CIT that is withheld at source is partially credited against the PIT when dividends are distributed (see also (OECD, 2020[8])).

Chile’s tax mix was different to the OECD average (and more different than currently) when the OECD had similar GDP per capita to Chile in 1978. Chile’s GDP per capita is USD 23 151 in 2019, significantly below the OECD average of USD 42 953. It is instructive to compare Chile’s tax mix to the OECD at the time when the OECD was economically more similar to Chile. The OECD’s GDP per capita was most similar to Chile’s current GDP per capita in the year 1978, when it was USD 22 994. Despite a more similar income level, Chile’s tax mix is actually less similar to the OECD average in 1978 than it is to the OECD in 2018, as shown in Figure 3.1.

Figure 3.1. Chile’s tax revenues are relatively concentrated in VAT and CIT

Note: OECD average data is for the year 2018 as this is the latest available data by tax categories. For Chile and the OECD average, the taxes shown represent 96.4% and 98.7% of total taxes respectively. Since Chile’s tax-to-GDP ratio (20.7%) is below the OECD average (33.8%) in 2019, the tax-to-GDP figures by tax category in Chile are relatively smaller than taxes as a share of total tax revenues.

Source: OECD (2020), Revenue Statistics 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8625f8e5-en.

Some aspects of Chile’s tax structure are atypical such as the small role of SSCs and the large role of compulsory contributions to the private sector

Social benefits are mostly funded by SSCs in the OECD, but other funding sources exist. Social benefits provided by governments require funding. The most common source of financing for social security-type benefits in OECD countries are taxes, and for the most part SSCs. SSCs along with other earmarked taxes account for over 90% of the financing of social security-type benefits in 25 OECD countries and 100% in 13 countries (OECD, 2020[2]). SSCs are usually paid to the government and used to provide a social benefit (or contingent entitlement) in the future. Examples include unemployment benefit (in the event an individual loses her employment) and child benefit (in the event an individual has a child). In addition to SSCs, social benefits can also be financed with a number of other sources, as shown in Figure 3.1. SSCs and other taxes earmarked for social security-type benefits represent tax revenues sources. Voluntary contributions to governments and compulsory contributions to the private sector represent non-tax revenues sources.

Chile’s social security benefits are not mainly financed through SSCs, as is common in the OECD, but rather through contributions to the private sector. According to the analysis in Figure 3.1, Chile’s overall finances for social benefits is relatively small (7.2% of GDP) compared to the OECD average (11.1% of GDP). Chile’s social benefits financing is also highly concentrated in non-tax revenues, specifically compulsory contributions to the private sector (5.8%), relative to the OECD average (0.9% of GDP). It follows that Chile’s social benefits financing is not particularly focused on taxes, especially SSCs (1.5% of GDP), relative to the OECD average (9.5% of GDP).

Table 3.1. Chile’s social security benefits are mostly financed by contributions to the private sector

Financing sources for social security-type benefits in Chile and the OECD, 2018

|

Tax and non-tax |

Source |

Chile (% of GDP) |

OECD average* (% of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Tax revenues |

1. Social security contributions (SSCs) |

1.5 |

9.5 |

|

2. Other taxes earmarked for social security-type benefits |

0 |

0.6 |

|

|

Non-tax revenues |

3. Voluntary contributions to government |

0 |

0.1 |

|

4. Compulsory contributions to private sector |

5.8 |

0.9 |

|

|

Total |

7.2 |

11.1 |

|

Note: *The OECD average is calculated as weighted average for countries where data are available and does not include Australia, New Zealand and the Netherlands. Further details relating to the caveats are available in the source below.

Source: OECD (2020), Revenue Statistics 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8625f8e5-en.

Compulsory contributions to the private sector play a role in several OECD countries

Contributions to the private sector are very significant in Chile, and far more so than SSCs. In Chile, the tax-to-GDP ratio is 21.1% in 2018 and compulsory contributions to the private sector represent a significant 5.8% of GDP in 2018 or 27.5% of total tax revenues. By comparison, SSCs represent 1.5% of GDP or 6.9% of tax revenues in Chile in 2018. Therefore, compulsory contributions to the private sector are a factor of four times larger than SSCs in Chile.

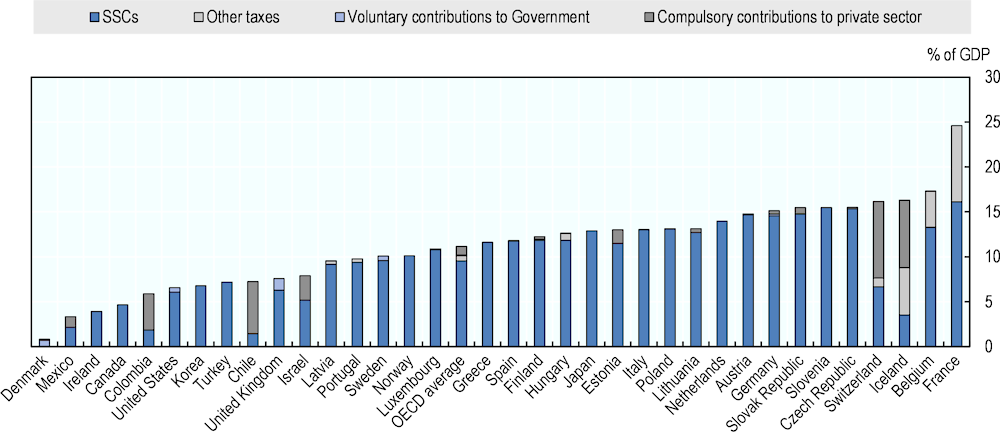

Compulsory contributions to the private sector are important for financing social security benefits in several OECD countries including Chile. Figure 3.2 shows that SSCs provide the largest source of financing for social security-type benefits in most OECD countries. In Chile, compulsory contributions to the private sector play a significant role, representing 79.6% of total SSCs. Compulsory payments to the private similar sector also play a significant role in other OECD countries including Colombia (68.6%), Switzerland (52.7%) and Iceland (46.1%) and to a lesser extent in Mexico (34.6%) and Israel (34.2%).

Figure 3.2. Compulsory contributions to the private sector play a role in several OECD countries

Source: OECD (2020), Revenue Statistics 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8625f8e5-en.

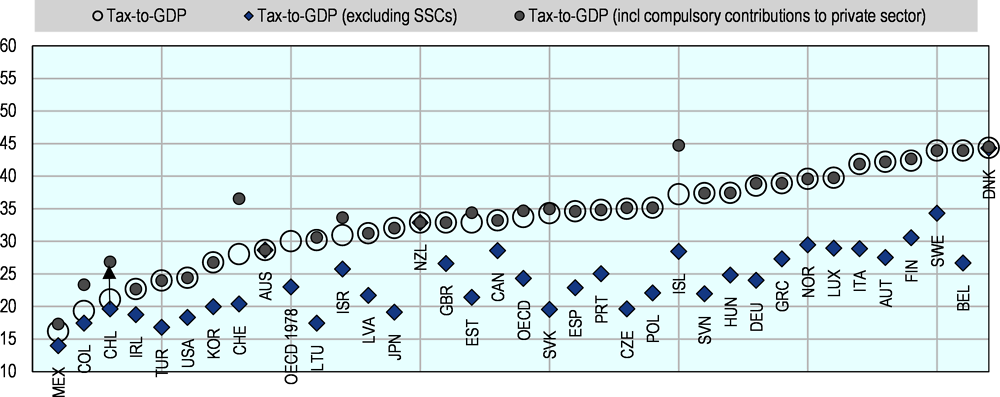

Chile’s tax-to-GDP ratio remains relatively low, regardless of whether SSCs are excluded or contributions to private sector are included

When compulsory contributions to the private sector are included, Chile’s tax-to-GDP ratio ranking among OECD countries changes from the 3rd lowest to the 7th lowest. As noted previously, Figure 3.3 shows that Chile’s tax-to-GDP ratio is significantly below the OECD average (21.1% in 2018 compared to 33.7% in the OECD). Indeed, Chile’s tax-to-GDP was the 3rd lowest in the OECD in 2018. Some commentators might argue that tax-to-GDP comparisons with the OECD are misleading given Chile’s atypically low SSC revenues and large compulsory contributions from the private sector. However, drawing a tax-to-GDP comparison in the OECD by excluding SSCs has the potential to be misleading because SSCs play a significant role in the tax revenues of many OECD countries and SSCs as a share of tax revenues have increased in OECD countries in recent decades. Similarly, adding compulsory contributions to the private sector to the tax-to-GDP share is not considered standard practice in the OECD. Notwithstanding these caveats, Figure 3.3 shows the tax-to-GDP ratio in Chile and OECD countries without SSCs and alternatively with contributions to the private sector. Three main results are obtained. First, when SSCs and other earmarked taxes are excluded from the analysis, Chile’s tax-to-GDP narrows the gap with the OECD average (19.6% compared to 24.3% in 2018 respectively) but remains among the lower tax-to-GDP countries in the OECD (9th lowest). Second, when SSCs are excluded, Chile’s tax to-GDP ratio is only modestly below that of the OECD average of 23% in 1978 when the OECD had a similar level of economic development to Chile’s current level (see Chapter 5 for a further exploration of this analytical approach). Third, when compulsory contributions from the private sector are included in the analysis, Chile’s tax-to-GDP similarly moves closer to the OECD average (26.9% compared to 34.7% in 2018 respectively). Once again however, Chile remains among the lowest tax-to-GDP countries in the OECD (7th lowest).

Figure 3.3. Chile’s tax-to-GDP ratio remains relatively low without SSCs and with private contributions

Note: The tax-to-GDP ratio (excluding SSCs) refers to excluding SSCs and also other earmarked taxes. The Netherlands are not included in the figure as complete data on social security financing were not available.

Source: OECD (2020), Revenue Statistics 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8625f8e5-en.

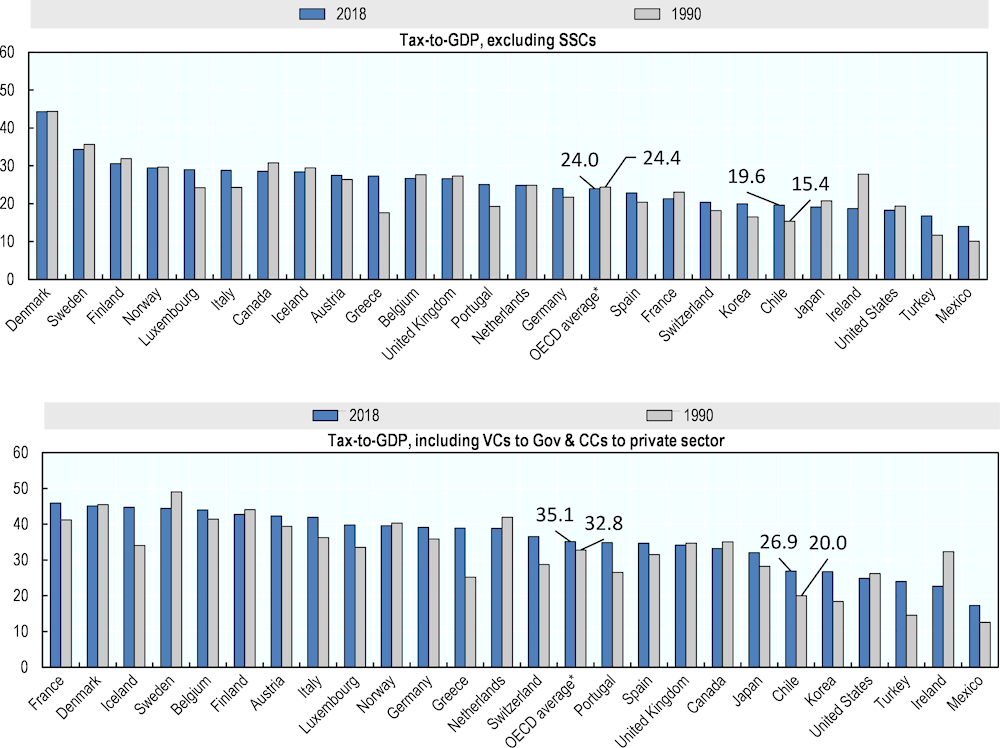

Since 1990, Chile narrowed the tax-to-GDP gap with the OECD relatively faster when the tax-to-GDP is adjusted to account for Chile’s atypical tax structure

Between 1990 and 2019, Chile’s tax-to-GDP narrowed the gap with the OECD average by 1.1 percentage points, when no adjustments are made to the tax-to-GDP ratio. This section examines the development of the tax-to-GDP ratio in Chile and OECD countries over time in 1990 and 2018 (Figure 3.4). Once again, two additional adjustments to the tax-to-GDP ratio are made – first, SSCs are excluded, and second, voluntary contributions to government and compulsory contributions to the private sector are included. As mentioned previously, when no adjustments are made to the tax-to-GDP ratio, Chile’s tax-to-GDP ratio is below the OECD average and has been for some time (in 2019, 20.7% compared to 33.8% respectively and in 1990 16.9% compared to 31.1% respectively), despite Chile’s tax-to-GDP catch-up in recent decades1. Consequently, the gap between Chile and the OECD narrowed over the period by 1.1 percentage points (from 14.2pp in 1990 to 13.1pp in 2018).

Between 1990 and 2019, when compulsory contributions to the private sector are included in the tax-to-GDP ratio, Chile narrows the tax-to-GDP gap with the OECD average by 4.5 percentage points. Since not all countries had the data to make these adjustments in both years, the analysis is based on a smaller sample of countries. When VCs and CCs are included, Chile’s tax-to-GDP is 26.9% in 2018 and 20.0% in 1990, compared to 35.1% in the OECD and 32.8% in 1990. Therefore, Chile’s tax-to-GDP ratio narrowed the gap with the OECD by 4.5 percentage points (from a gap of 12.8 percentage points in 1990 to 8.2 percentage points in 2018). On this basis, Chile would have the 6th lowest tax-to-GDP ratio.

Between 1990 and 2019, when SSCs are excluded from the tax-to-GDP ratio, Chile narrowed the tax-to-GDP gap with the OECD average by 4.7 percentage points. When SSCs are excluded, Chile’s tax-to-GDP is 19.6% in 2018 (15.4% in 1990), compared to 24.0% in the OECD (24.4% in 1990). Therefore, when SSCs are excluded, Chile’s tax-to-GDP ratio grew much more quickly than the OECD (which in fact declined), resulting in Chile narrowing the absolute gap with the OECD average by 4.7 percentage points (from 9.0 percentage points in 1990 to 4.4 percentage points in 2018). On this basis, Chile would have the 6th lowest tax-to-GDP ratio.

Figure 3.4. When the tax-to-GDP ratio definition is adjusted to account for Chile’s atypical tax structure, Chile remains among the lower tax-to-GDP OECD countries

Note: Countries are only included if they had tax-to-GDP in 1990 and 2018 with SSCs, voluntary contributions to government and compulsory contributions to the private sector. For 1990 data are not available for Estonia, Poland, Slovenia, Slovak Republic, Hungary, Israel, and Czech Republic. Countries which joined the OECD after 1990 and for which data are not available in 1990 are not included. *The OECD average represents a simple weighted average of countries in which data are available in 1990 and 2018.

Source: OECD (2020), Revenue Statistics 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8625f8e5-en.

Broadly similar tax rates in Chile and the OECD point to low tax revenues driven by a narrow tax base, particularly in the case of PIT

Chile’s CIT rate in 2020 is above the average CIT rate in the OECD, having increased over the past 20 years in contrast to a widespread decline in the OECD average rate. Table 3.2 provides a simple comparison of selected statutory tax rates in Chile and the OECD average in 2020 and 2000 (a more detailed comparison of tax rates goes beyond the scope of this research). Chile’s combined CIT rate is 27% in 2020, which is somewhat higher than the OECD average rate of 23.5%. Chile’s combined CIT rate has increased significantly since 2000 when it was 15%. By contrast, in the OECD generally there has been a steady and widespread decline in CIT rates over the past decade, although some countries have introduced or announced new tax increases over the past year. Overall, in the OECD, the average combined (central and sub-central) CIT rate has declined from 32.2% in 2000 to 23.5% in 2020.

Chile’s VAT rate is similar to the average VAT rate in the OECD, having remained stable over the past 20 years similar to the OECD average rate. Chile’s standard VAT rate is 19% in 2020, which is similar to the OECD average of 19.3%. The VAT rate has increased modestly from 2000 when it was 18%. In OECD countries, the VAT rate increased steadily from 18% in 2000. Raising standard VAT rates was a common strategy for countries seeking to achieve fiscal consolidation in the wake of the global financial crisis as increasing VAT rates provides immediate revenues without directly affecting competitiveness and has generally been found to be less detrimental to economic growth than raising direct taxes (Johansson et al., 2008[9]).

Despite a high top PIT rate, the tax burden on individuals is low in Chile driven by a narrow PIT base. Chile’s top PIT rate is 40% in 2020 (based on the second category income tax rate), which is modestly lower than the OECD average rate of 42.8%. Chile’s top PIT rate has declined modestly from 45% in 2000, similar to the trend of the OECD average rate. However, Chile’s top PIT rate only applies at high levels of income and does not apply to the vast majority of individual taxpayers. Consequently, the low tax burden on individuals in Chile is not driven by the PIT rate (or the PIT rate threshold) but rather by the narrow PIT base and a high basic allowance. Low revenues from the PIT, including from taxes on capital income, are caused by other factors as well, including generous PIT expenditures. Notably, 76% of Chileans that file tax returns are in the exempt bracket (OECD, 2018[6]). As a result, the effective tax burden on individuals based on OECD Taxing Wages - measured by the total tax wedge for single persons earning the average wage - was only 7% in 2019 in Chile compared to 25.9% in the OECD average (note that this low effective tax burden on individuals in Chile reflects only a 7% contribution for health and does not take account of Chilean SSCs).

Similar tax rates in Chile and the OECD suggest that raising the relatively low levels of tax revenues in Chile might better be achieved through tax base (rather than tax rate) reform. Despite Chile’s relatively low tax revenues (see Section 2.2), this simple tax rate comparison highlights that some of Chile’s main tax rates in 2020 are similar to the OECD average. If Chile decides to raise additional tax revenues, the analysis provides suggestive evidence that there may be greater scope to do so through base broadening (e.g. limiting tax expenditures rather than tax rate increases and reducing tax evasion and avoidance) and rebalancing the tax mix (e.g. by increasing personal income tax revenues, including revenues from taxes on capital income).

Table 3.2. While tax rates in Chile are broadly similar to average rates in the OECD, the effective tax burden on individuals is low

% tax rates on individuals, companies and goods and services in Chile and the OECD, 2000 and 2020

|

2020 |

2000 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Taxes on |

Measured by |

Chile |

OECD average |

Chile |

OECD average |

|

Individuals |

Top PIT rate |

40.0 |

42.8 |

45.0 |

45.4 |

|

Individuals |

Tax wedge |

7.0 |

25.9 |

||

|

Companies |

Combined CIT rate |

27.0 |

23.5 |

15.0 |

32.2 |

|

Goods & Services |

Standard VAT rate |

19.0 |

19.3 |

18.0* |

18.0 |

Note: *The standard VAT rate in Chile relates to the year 1995. Combined statutory CIT rates refer to central and sub-central statutory CIT rates. Chile’s top PIT rate of 40% relates to the second category income tax. The tax wedge refers to single persons with no children at the average wage based on OECD Taxing Wages.

Source: OECD (2020), OECD Tax Database Statistics 2020, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TABLE_I1

Note

← 1. As we have seen previously, while’s tax-to-GDP has grown somewhat faster than that of the OECD since 1990 resulting in a reduction in the absolute tax-to-GDP gap from 14.2 in 1990 to 13.1 in 2019.