This chapter begins by considering the historical growth pattern of tax-to-GDP in OECD countries. The chapter then examines theoretical and empirical evidence for whether low tax-to-GDP countries catch-up with high tax-to-GDP countries over time (known as beta tax convergence) and whether Chile’s tax structure has become more similar to the OECD average over time (known as sigma tax convergence).

OECD Tax Policy Reviews: Chile 2022

4. Tax convergence

Abstract

A growing tax-to-GDP over time has been the historical norm across countries on average, but is far from guaranteed in individual countries

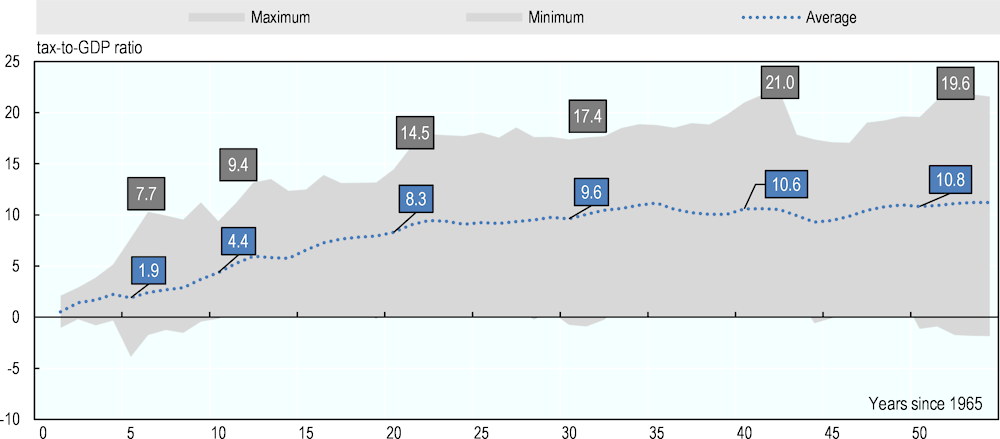

The tax-to-GDP ratio grew at an average annual rate of about two percentage points per decade in the OECD, based on historical data. Does the tax-to-GDP ratio grow over time and by how much? Forecasting future tax-to-GDP ratios is uncertain and challenging and there are many methods for producing economic forecasts. One such method is to estimate the future tax-to-GDP ratio path based on long-term historical average data. There are caveats to this method including that it does not take into account current economic conditions and its accuracy depends on the extent to which the future tax-to-GDP ratio is well-explained by the historical tax-to-GDP ratio. Notwithstanding these caveats, using 1965 as the base year, Figure 4.1 shows that the tax-to-GDP ratio increased on average in the OECD by 3.7, 7.9 and 9.7 percentage points cumulatively over 10, 20 and 30 years. The maximum tax-to-GDP ratio increase in any OECD country was 9.4 percentage points after ten years, 14.5 percentage points after 20 years and 17.4 percentage points after 30 years. Over the full period 1965 to 2019, the average annual tax-to-GDP increase was 0.21 percentage points or 2.1 percentage points in ten years. In a given year, the maximum tax-to-GDP increase was 5.1 percentage points and the minimum was decline of 5.6 percentage points. The top 10% of tax-to-GDP ratio increases was 1.4 percentage points.

While a rising tax-to-GDP ratio is the historical norm across OECD countries on average, it is far from guaranteed in individual countries. The tax-to-GDP ratio is not necessarily an indicator that converges in the same way as has been shown in the literature for GDP per capita. By definition, for a given level of tax revenues in a country, any increase in GDP will reduce the tax-to-GDP ratio. Ireland is a case in point. Even as Ireland’s economy began to converge with the OECD and its GDP per capita grew, its tax-to-GDP ratio fell. Figure 4.1 also highlights that, in the first 35 years since 1965, the average tax-to-GDP ratio rose significantly but it remained broadly constant since then (with the exception of fluctuations during economic crises).

Figure 4.1. Tax-to-GDP ratios have tended to grow over time in the past

Note: Analysis conducted on the 23 OECD countries for which data is available between 1965 and 2019. Latest data for Australia and Japan is for 2018.

Source: OECD (2020), Revenue Statistics 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8625f8e5-en.

Evidence points to tax convergence among countries over time

Tax convergence is measured using the tax-to-GDP ratio in the research literature. How is convergence and tax convergence defined? In the field of economics, convergence generally refers to economic convergence, which can be defined as whether poor economies close the gap with rich economies over time (measured using GDP per capita). A vast literature exists on economic convergence. Neoclassical growth theory states that open economies with access to the same technology should converge to a common income level (Barro and Sala-i-Martin, 1992[10]) (Mankiw, Romer and Weil, 1992[11]). Fiscal convergence, a hotly researched topic in international tax, has been defined in the literature in different ways including in terms of tax convergence which is measured in terms of the tax-to-GDP ratio (Tibulca, 2015[12])1. For the purposes of the current research, this latter definition of tax convergence is used.

Tax convergence can be measured in different ways according to the research literature. The approaches used to measure economic convergence can also be applied to tax convergence. Two commonly adopted approaches to measure tax convergence are sigma (hereafter σ-convergence) and beta convergence (hereafter β-convergence)2. The meaning of the term convergence is somewhat different in each case, which is worth understanding. β-convergence refers to the speed of tax convergence (Baumol, 1986[13]). β-convergence has been the dominant method for about 25 years to test whether poorer countries tend to grow faster (Kant, 2019[5]). In a tax convergence context, it tells us whether low-tax countries catch-up (in terms of their tax-to-GDP ratio) with high-tax countries over time. β-convergence occurs in a group of countries when those with below-average tax-to-GDP ratios grow their tax-to-GDP ratios faster than those with above-average tax-to-GDP ratios over time. σ-convergence, on the other hand, occurs in a group of countries when there is a decline in the dispersion of the tax-to-GDP ratio over time. σ-convergence can be measured using a range of dispersion indicators including standard deviation, coefficient of variation (CV), the absolute deviation from the average, Gini coefficient and range measures. Of these indicators, CV is perhaps the most commonly adopted. β-convergence is a necessary but not a sufficient condition for σ-convergence because below-average economies must grow faster than above-average economies for there to be a decline in dispersion. σ-convergence provides a more accurate indication of convergence because it shows whether the dispersion of the entire distribution is declining.

Table 4.1. Two key measures of convergence are beta and sigma convergence

|

Convergence measure |

Answers the question of |

Stylized fact |

Policy questions |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Beta (β-convergence) |

How fast are poorer economies catching-up with richer economies? |

In a group of countries, those with below-average incomes grow faster than those with above-average incomes over time |

Does tax convergence occur in a similar way to economic convergence? |

|

Sigma (σ-convergence) |

Are countries becoming more similar over time? Is a group of economies converging or diverging from its average? |

There is a decline in dispersion over time |

Do countries adopt policies so that they converge to the group over time? Do ‘convergence clubs’ exist? |

Evidence from the research literature generally points to tax convergence over time. Does the evidence from the research literature suggest that countries adopt policies that cause them to converge with the group average (tax-to-GDP ratio) over time? Table 4.2 provides evidence that the answer to this question is yes – tax convergence is often detected over time (as opposed to tax divergence). Table 4.2 also confirms that tax convergence is commonly measured using the measures of σ-convergence and β-convergence. However, the summary results provided in Table 4.2 should be interpreted with caution because of the different methodological approaches used in the studies. For example, there are differences in the tax convergence measures, time periods and countries and regions under examination.

Table 4.2. Some evidence points to tax convergence over time

Selected research on tax convergence

|

Research author |

Convergence measures used |

Period |

Convergence identified (1) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Esteve et al. (2000) |

Sigma, beta |

1967 - 1994 |

Yes |

|

Sosvilla et al. (2001) |

Sigma (standard deviation), beta |

1967 – 1995 |

Yes |

|

Delgado (2006) |

Sigma, beta and gamma |

1965 – 2003 |

Yes |

|

Gemmel and Kneller (2003) |

Sigma (Gini coefficient) |

1970 - 1995 |

|

|

Tibulca (2015) |

Sigma (coefficient of variation; Gini coefficient) |

1965 - 2012 |

Yes |

|

OECD (2018) |

Sigma (d-index) |

1995 - 2016 |

Yes |

|

Delgado and Presno (2008) |

Beta convergence |

1965 - 2005 |

No |

|

Chen et al. (2015) |

Sigma and beta convergence |

1980 - 2014 |

Yes |

Note: (1) Refers to cases where any convergence was identified during any period as part of the research. The study by Chen et al. (2008) estimates corporate income tax convergence using corporate income tax rates and not tax-to-GDP ratios.

Source: Table adapted from (Tibulca, 2015[12]) (OECD, 2018[3]).

Despite the evidence for tax convergence across countries, it is not guaranteed for individual countries without the right conditions in place. Some of the economic convergence literature argues that economic convergence is conditional and occurs only when country specific conditions are in place including specific policies, institutional arrangements and external shocks. This suggests that the policies that successful countries have used are hard to emulate and that transplanting experience from one country to another is difficult and ‘convergence is anything but automatic’ (Rodrik, 2011[15]). A similar line of reasoning might apply to tax convergence whereby certain country-specific policies and institutional arrangements may first need to be in place for tax-to-GDP ratios to grow over time. However, it important to note that GDP per capita and tax-to-GDP ratios are very different measures. –There seem to be evidence that the tax-to-GDP ratio cannot continue to increase beyond some point when it begins to become damaging to economic activity and this is evidenced in the historical upper bound tax-to-GDP ratio of about 50% in OECD countries (see Figure 2.3).

Empirical evidence supports the notion that low tax-to-GDP OECD countries catch-up over time (beta convergence)

Beta tax convergence can be empirically confirmed through correlation and econometric analysis. This section explores the evidence for whether lower tax-to-GDP countries like Chile tend to catch-up with higher tax-to-GDP on average over time (i.e. beta-convergence), based on OECD countries in recent decades. From an empirical perspective, tax β-convergence can be confirmed by showing a tendency for countries with lower tax-to-GDP ratios to increase their tax-to-GDP ratios faster than countries with higher tax-to-GDP ratios over time. Using correlational analysis, this can be confirmed by a negative slope in a two-way scatterplot. Using econometric analysis, this can be confirmed by a statistically significant negative sign of the estimated coefficient.

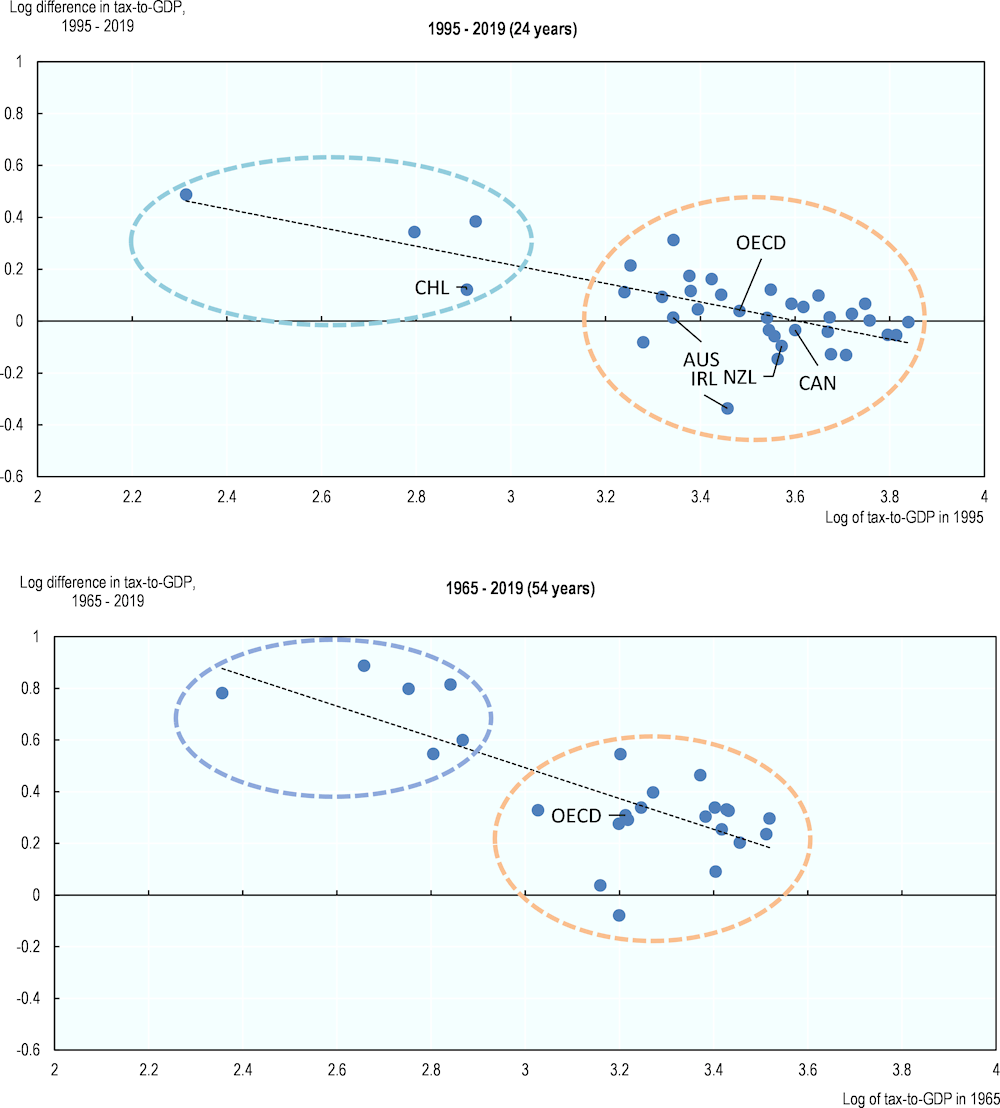

Correlation analysis on OECD historical data confirm that tax-to-GDP convergence occurs among OECD countries over time. Figure 4.2 shows that a higher starting tax-to-GDP ratio is indeed associated with smaller subsequent growth in the tax-to-GDP ratio among OECD countries over time, based on OECD revenue statistics data. Tax-to-GDP convergence is confirmed by the observed negative downward sloping line. Conversely, it follows that countries with lower tax-to-GDP ratios grow their tax-to-GDP ratios faster on average than countries with larger tax-to-GDP ratios. Figure 4.2 also shows that the tax-to-GDP convergence has been stronger over the past half-century (1965 – 2019) than in the more recent past quarter-century (1995 – 2019). This is observed in the steeper downward negative correlation between starting tax-to-GDP and subsequent growth in tax-to-GDP during this period and the higher average subsequent growth in tax-to-GDP.

Figure 4.2. There is evidence of β-convergence in OECD countries over the past half century

Note: Data for Australia and Japan is 2018. Natural logs are used. The set of OECD countries for which data is available in both years in 1965 and 2019 is smaller (i.e. in the bottom graph).

Source: OECD (2020), Revenue Statistics 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8625f8e5-en.

An econometric equation can be formulated to test β-convergence. To test β-convergence econometrically, a log-log Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression model is employed using robust standard errors (to account for heteroscedasticity3). The data used are country-level OECD revenue statistics for the two periods 1965 to 2019 and 1995 to 2019 respectively. The specification is set out in equation (1) below, where ∆𝑌 is the change in the tax-to-GDP over the period, 𝑌it-1 is tax-to-GDP in the starting year and Zit-1 is a set of explanatory variables in the starting year including GDP per capita and the working age population. Beta-convergence can be confirmed by a statistically significant negative sign of β1.

(1) ∆(log)𝑌 it = a + β1(log)𝑌it-1 + β2Zit-1 + Uit

Econometric evidence for OECD countries shows that low tax-to-GDP ratio countries tend to catch-up with high tax-to-GDP countries over time, albeit slowly. Table 4.3 presents the results of econometric modelling to test the β-convergence hypothesis (i.e. whether lower tax-to-GDP countries catch-up with richer tax-to-GDP countries over time). The results show that a higher initial tax-to-GDP ratio is associated with lower subsequent tax-to-GDP growth. Specifically, a 1% lower tax-to-GDP ratio in 1995 is associated with 0.36% higher tax-to-GDP growth rate between 1995 and 2019 (see Model 1). The result is also statistically significantly different from zero. When the initial period is instead 1965, and for a smaller set of countries, the subsequent tax-to-GDP ratio growth association increases to 0.60%. When the initial levels of GDP per capita and the working age population share are controlled for in the modelling (see Models 2 and 3), the main result continues to hold – low tax-to-GDP ratio countries tend to catch-up with high tax-to-GDP countries over time. Overall, the subsequent tax-to-GDP growth rate ranges from 0.36% – 0.44% over the subsequent quarter century. Furthermore, these estimates for tax convergence are below those for economic convergence, which are typically around 2% per year in the literature. Separately, a panel data econometric model was also explored as part of this analysis by restructuring the same OECD tax-to-GDP data into a longitudinal structure where the tax-to-GDP ratio is observed in 36 countries in each year between 1995 and 2019. When the dependent variable is set as the log of tax-to-GDP and the explanatory variable is the five-year lag of the log of tax-to-GDP, the results show that the β-convergence remains but the magnitude is substantially smaller than under the previous cross-sectional model (-0.045 under a random effects model and not statistically significant under a fixed effects model).

A wide range of other factors contribute to tax-to-GDP catch-up including the working age population share. The growth in the tax-to-GDP ratio is influenced by a range of different factors according to the research literature to mention a few, these include GDP per capita, foreign direct investment trade and public debt and financial policies (Gupta, 2007, Bird et al, 2008, Teera and Hudson, 2004, Tanzi, 1988). Models 2 and 3 add two such measures, GDP per capita and the working age population share. GDP per capita would be expected to be positively related to tax-to-GDP because the size of the formal economy increases as a country expands its level of development. The share of the population that is of working age is also be expected to be positively related to tax-to-GDP due to a relatively larger taxpaying population and smaller non-taxpaying and dependent population. According to the modelling results, countries with larger working age populations tend to have faster subsequent tax-to-GDP growth. In the case of GDP per capita however, the result is not found to be statistically significant.

Table 4.3. Econometric evidence supports the hypothesis that low tax-to-GDP OECD countries tend to catch-up over time

Econometric evidence for the conditional β-convergence hypothesis, various OECD data, 1995 – 2019

|

Dependent variable: log difference of tax-to-GDP ratio |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1995 – 2019 |

1965 - 2019 |

|||||

|

OLS (1) |

OLS (2) |

OLS (3) |

OLS (4) |

OLS (5) |

||

|

Log of tax-to-GDP in 1995 |

-0.36*** (-8.59) |

-0.39*** (-8.56) |

-0.44*** (-8.00) |

-0.60*** (-6.87) |

-0.60*** (-5.52) |

|

|

Log of GDP per capita in 1995 |

0.47 (1.65) |

0.40 (1.31) |

0.002 (0.02) |

|||

|

Log of working age pop 1995 |

1.16** (2.39) |

|||||

|

R-squared |

0.50 |

0.52 |

0.58 |

0.55 |

0.55 |

|

|

No. observations |

36 |

36 |

36 |

24 |

24 |

|

Note: ***p<0.01, **p<0.05 *p<0.10. Robust t-statistics in brackets. Models 1 through 3 are based on 36 countries between 1995 and 2019. Models 4 and 5 are based on a smaller set of 25 countries between 1965 and 2019.

Source: OECD (2020), Revenue Statistics 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8625f8e5-en.

Chile’s tax mix has converged slowly with the OECD average tax mix, but more slowly than individual countries (sigma convergence)

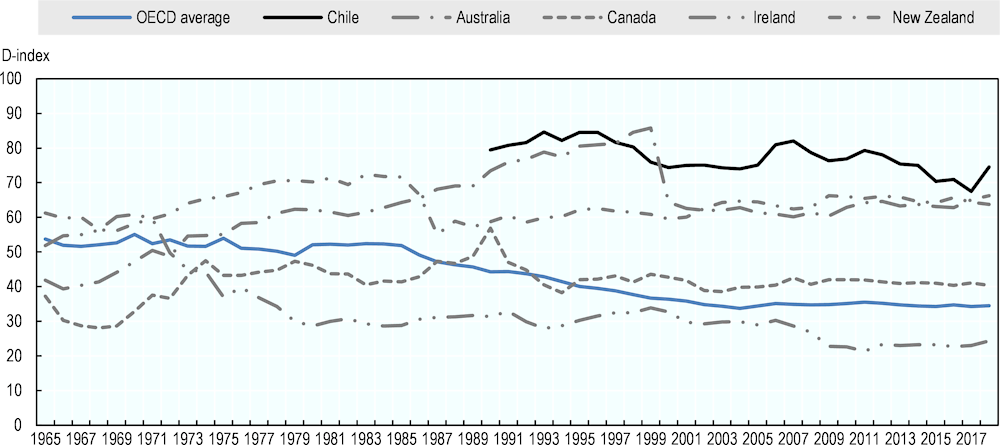

The extent to which OECD country tax structures have converged can be measured using the D-index. Are tax structures in OECD countries converging or diverging (i.e. becoming more or less similar)? This question can be addressed using a number of sigma-convergence type measures which examine the similarity of tax structures across countries. One method is the D-index (Delgado, 2013[16]), which provides an indicator of the difference between a country’s tax structure from a group average like the OECD. The D-index is calculated as the absolute difference in each tax category share for a given country from the OECD share. The tax categories are then summed for each country. With regard to interpretation, a value of zero would indicate that the country’s tax structure is the same as the OECD average structure. For all OECD countries between 1965 and 2019, the D-index averaged 44, with a maximum value of 112 and a minimum of 10. In the OECD, it was 50 in 1965 and 59 in 2019 (OECD, 2018[3]).

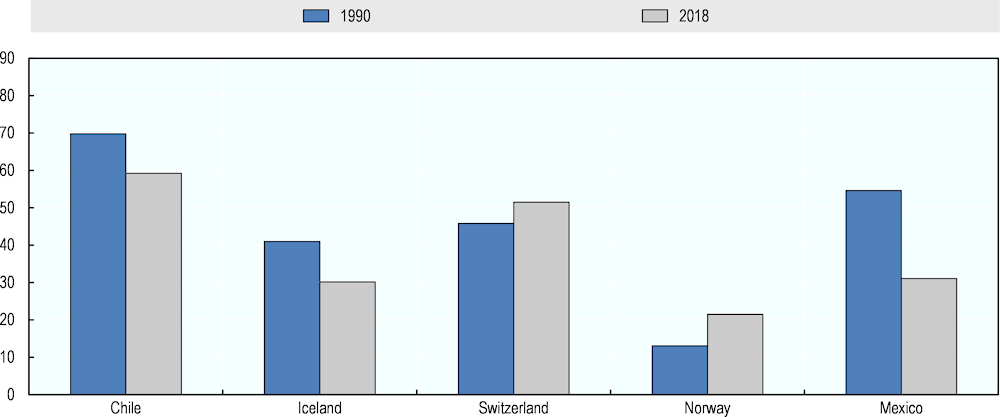

The D-index suggests that the OECD may be a tax ‘convergence club’, which implies that lower tax-to-GDP countries like Chile may tend to converge with the OECD average over time. Do countries adopt polices so that they converge to the average of the group or does tax policy remain largely nationally focused? Some strands of the economic convergence literature have examined the notion of ‘convergence clubs’ where poorer countries (measured in terms of GDP per capita) that are part of a group of countries (such as the OECD) tend to converge to the group average GDP per capita over time (Quah, 1995[17]). To the extent that the OECD is a ‘convergence club’ where members share knowledge and best practice, observing no convergence at all would be a concern. The D-index provides one way of empirically testing whether the OECD could be a tax ‘convergence club’. Figure 4.3 shows that the tax structure of individual OECD countries have become more similar to each other over the past half century since 1965 as measured by the D-index (which declined by 36% between 1965 and 2018). This result provides suggestive evidence that the OECD may be a tax ‘convergence club’. The causes underlying this tax convergence are varied and complex and go beyond the scope of this paper, however, one partial explanation could be that OECD countries tend to adopt policies that cause their tax-to-GDP ratio to converge to the average of the group. If this result were to hold for the future, it would imply that lower tax-to-GDP ratio countries such as Chile will tend to rise and converge with the OECD average tax structure over time

Chile has converged with the average OECD tax structure, but more slowly than other OECD countries. Figure 4.3 shows that, since 1995, Chile and the selected OECD countries have slowly converged with the OECD average tax structure (Chile’s and the OECD average D-index declined by 12% and 14% respectively between 1995 and 2018). However, Chile has converged more slowly than the individual OECD countries have with the OECD average (i.e. become more similar to each other in terms of their tax structure).

Figure 4.3. Chile’s tax mix has converged slowly with the OECD average tax mix, but more slowly than individual OECD countries

Note: The D-index refers to the sum of the absolute difference in tax structures in countries compared to the OECD average in a given year. The OECD average is calculated as the mean average of the sum of the absolute differences in all OECD countries, which provides an indicator of the extent to which tax structures are different or similar across countries in the OECD.

Source: OECD (2020), Revenue Statistics 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8625f8e5-en.

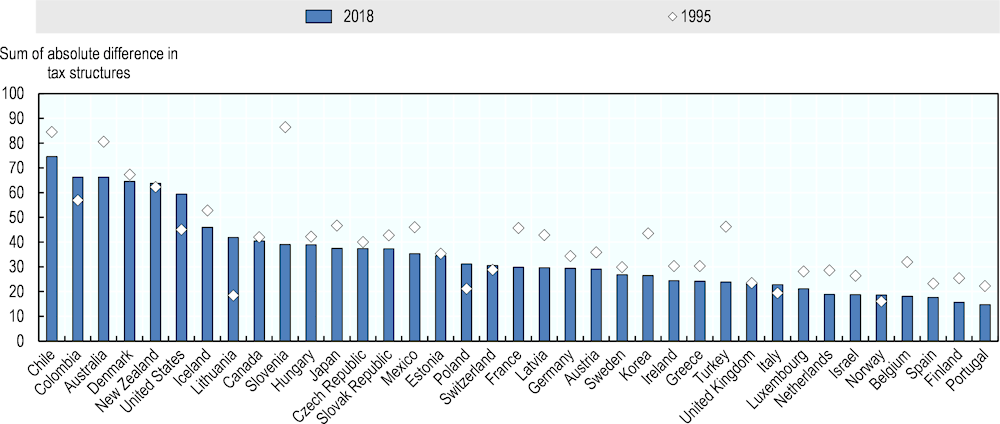

Chile’s tax structure differs significantly from the OECD average

Among OECD countries, Chile’s tax structure is one of the most divergent from the OECD average. Is Chile’s tax structure similar to the OECD average? Figure 4.4 shows the sum of absolute differences in tax structure for OECD countries in 2018 and 1995. Countries with the greatest tax structure difference from the OECD, as measured by the highest D-index, include those without SSCs (Australia, Denmark, New Zealand), without VAT (United States) and with relatively high VAT and low SSCs and PIT (Chile). Among OECD countries, Chile’s tax structure is one of the most divergent from the OECD average in 2018, although the absolute difference between Chile and the OECD has fallen modestly since 1995.

Figure 4.4. Chile’s tax structure is least similar to the OECD average

Note: *The D-index refers to the sum of the absolute difference in tax structures in countries compared to the OECD average in a given year. The tax categories are then summed for each country. With regard to interpretation, a value of 0 would indicate that the country’s tax structure is the same as the OECD average structure. For all OECD countries between 1965 and 2019, the D-index averaged 44, with a maximum value of 112 and a minimum of 10. In the OECD, it was 50 in 1965 and 59 in 2019

Source: OECD (2020), Revenue Statistics 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8625f8e5-en.

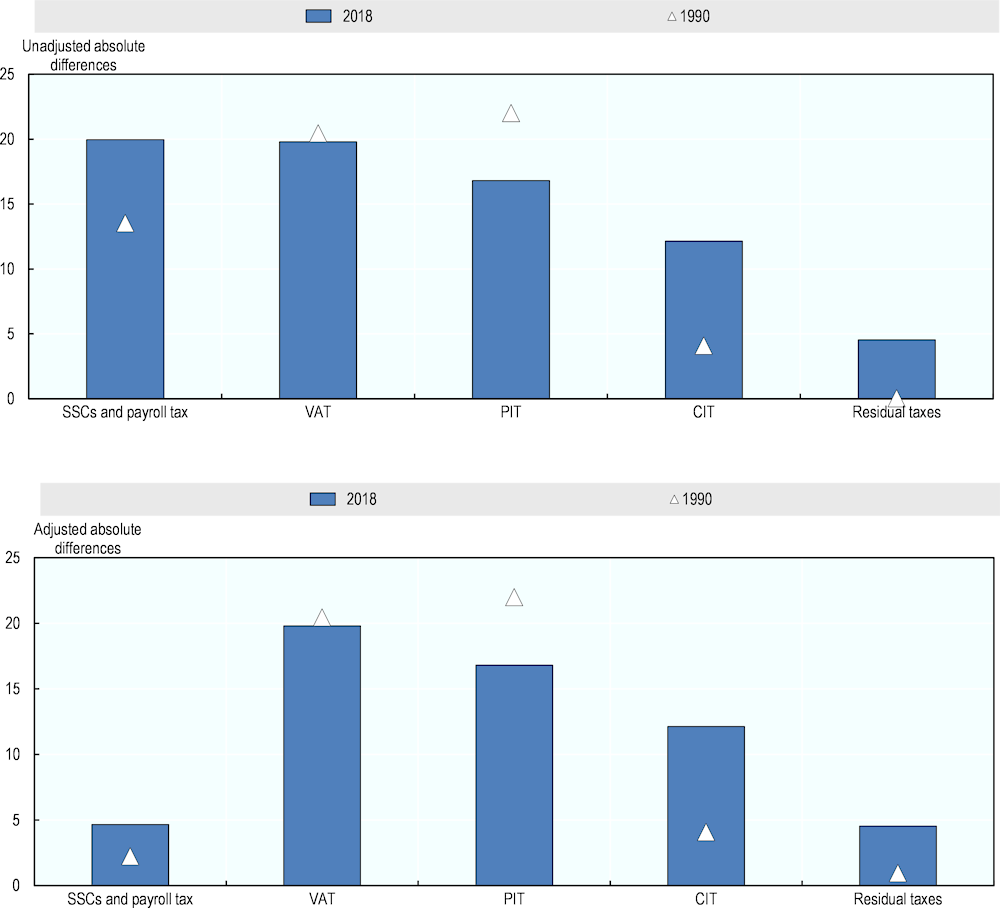

When compulsory contributions to the private sector are included, Chile’s tax structure moves closer to the OECD average but remains among the least similar the OECD average tax structure. Is Chile’s tax structure similar the OECD average when contributions to the private sector are accounted for? Figure 4.5 shows an adjusted D-index calculation which includes voluntary contributions to government and compulsory contributions to the private sector. These contributions are added to SSCs and payroll taxes, which are grouped together in the D-index calculation for each country. A number of further caveats are worth noting including that data on compulsory private contributions are not available for all countries in 1990 and 2018 and that the OECD average is based on a changing number of countries over time (for more detailed methodological notes, see notes in Figure 4.5). Overall, Chile’s unadjusted D-index is 79.5 in 1990 and 74.5 in 2018 while its adjusted index is 69.8 in 1990 and 59.9 in 2018. As a result, when compulsory contributions to the private sector are included as part of SSCs (i.e. the adjusted D-index) Chile’s tax structure looks more similar to the OECD average tax structure than when unadjusted (note that the D-index has also changed for other OECD countries as a result of the adjustment). However, even after the D-index is adjusted, Chile’s remains among the most dissimilar OECD countries in terms of its tax structure to the OECD average.

Figure 4.5. Chile’s tax structure moves closer to the OECD average structure when the D-index is adjusted to include compulsory contributions to the private sector

Note: The D-index refers to the sum of the absolute difference in tax structures in countries compared to the OECD average in a given year. *The adjusted D-index has been recalculated by adding voluntary contributions to government and compulsory contributions to the private sector to SSCs and payroll taxes (which are grouped together for the purposes of the D-index analysis) for all countries in 1990 and 2018. There are 25 countries were voluntary contributions to government and compulsory payments to the private sector are available in 1990 and 2018. Note that the addition of these contributions changes SSCs for these 25 countries but also for the OECD average and therefore the calculation of the absolute difference between countries and the OECD average. Consequently, the adjusted D-index calculations will be different than the unadjusted D-index calculations for all countries.

Source: OECD (2020), Revenue Statistics 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8625f8e5-en.

Chile’s tax structure gap with the OECD is driven by VAT and PIT, when contributions to the private sector are included in SSCs

When compulsory contributions to the private sector and voluntary contributions to government are added to SSCs in all countries, the gap between Chile’s tax structure and the OECD average is driven by VAT and PIT. Which taxes drive the tax structure gap between Chile and the OECD average? The top chart in Figure 4.6 shows the absolute differences in tax structure between Chile and the OECD in 1990 and 2018. The largest differences are observed for SSCs (plus payroll), VAT, PIT and CIT. The bottom chart in Figure 4.6 shows the difference in Chile’s tax structure when the above adjusted D-index methodology is applied (i.e. voluntary contributions to government and compulsory contributions to the private sector are added to SSCs and payroll taxes for all countries). On this basis, SSCs and payroll taxes in Chile are now similar to the OECD average (unlike in the case of the previous unadjusted D-index) and the gap between Chile’s tax structure and the OECD average is primarily driven by VAT and PIT revenues.

Figure 4.6. The difference in Chile’s tax structure compared to the OECD average is driven primarily by the gap in VAT and PIT

Note: Absolute differences refer to a non-negative differences between the country and the OECD average structure.

Source: OECD (2020), Revenue Statistics 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8625f8e5-en.

Some evidence suggests that lower income countries have the potential for faster subsequent tax-to-GDP growth

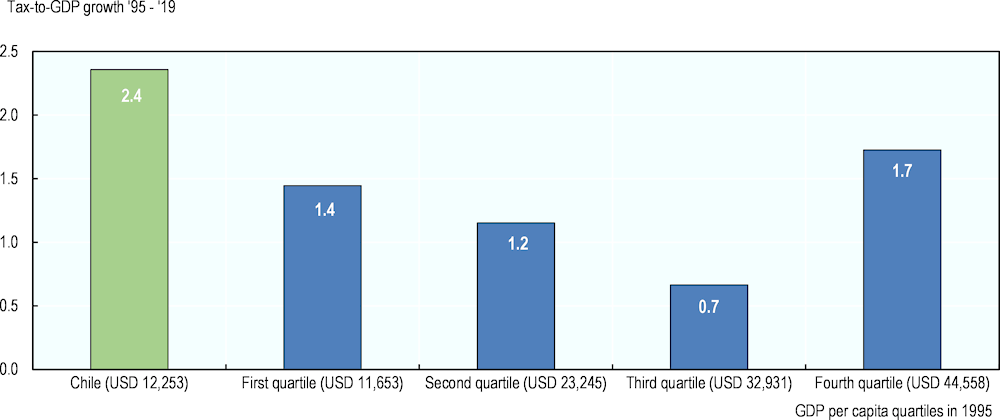

Some evidence points to tax-to-GDP ratios growing faster in countries that have lower starting income levels, but only up to a point. A related but different question to tax convergence is whether poorer countries (measured by lower GDP per capita) tend to experience greater tax-to-GDP ratio growth than richer countries over time. Figure 4.7 shows tax-to-GDP growth in Chile and in the OECD between 1995 and 2019 based on GDP per capita quartiles in 1995. The analysis provides some evidence that tax-to-GDP ratios grow faster on average for countries with lower starting levels of GDP per capita, but only up to a point. Countries that were in the bottom quartile of the OECD in GDP per capita in 1995 had faster subsequent tax-to-GDP growth than richer countries in the second and third GDP per capita quartiles. However, countries who were in the top quartile of GDP per capita in 1995 had the fastest tax-to-GDP growth over the period. Chile, which was in the bottom quartile of GDP per capita countries in 1995 (with a GDP per capita of USD 12 253), had a faster subsequent tax-to-GDP growth than the average in any quartile.

However, some countries with similar income levels have followed opposite paths tax-to-GDP trajectories. The association between GDP per capita and subsequent growth in the tax-to-GDP ratio is not particularly strong. Part of the reason is that individual countries, with both low and high income levels, have followed divergent tax-to-GDP paths. For example, Ireland, which had a relatively high GDP per capita in 1995 (USD 31 404), went on to significantly reduce its tax-to-GDP by 9.1 percentage points between 1995 and 2019. The reduced tax-to-GDP ratio in Ireland was substantially driven by exceptionally fast growth in GDP - Ireland’s GDP per capita grew by about 7.0% annually between 1995 and 2019, compared to 1.8% in the OECD. A wide range factors have been proposed to explain the economic boom in Ireland (the so-called ‘Celtic Tiger’ economy) including the introduction of the Single European Market, FDI inflows from the United States into Ireland and a low corporate tax rate (Barry, 2003[18]). Ireland also provides an example of measurement issues associated with tax-to-GDP ratios, particularly how a single indicator such as GDP can mislead analysis (Honohan, 2021[19]). On the other hand, Luxembourg, which had a very high GDP per capita in 1995 (USD 71,920), increased its tax-to-GDP ratio by 4.5 percentage points over the same period. Similar divergent paths in the tax-to-GDP ratio occurred for lower income countries which were in the first quartile of GDP per capita countries in 1995, with for example Mexico increasing its tax-to-GDP by 6.4 percentage points between 1995 and 2019 and the Slovak Republic reducing its tax-to-GDP ratio by 4.8 percentage points. Furthermore, as seen in Figure 4.7, tax-to-GDP ratios in the OECD on average have tended to grow faster in the past when the levels of economic development were lower. For example, 10, 20 and 30 years after OECD countries had similar economic development levels to Chile, the tax-to-GDP ratio rose by 3.1, 2.5 and 0 percentage points respectively.

Figure 4.7. Countries with lower starting GDP per capita tended to have faster subsequent tax-to-GDP, but this was not always the case

Note: Analysis based on 36 OECD countries between 1995 and 2019 divided into 4 quartiles based on GDP per capita levels in 1995 with 9 countries in each quartile. Australia and Canada tax-to-GDP data are for the year 2018. For comparability, the data are converted to a common currency, US dollars, using purchasing power parities (PPP). PPPs are currency converters that control for differences in the price levels between countries, making it possible to compare absolute values across countries.

Source: OECD (2020), Revenue Statistics 2020, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8625f8e5-en and OECD Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b2774f97-en

Notes

← 1. Other strands define fiscal convergence as convergence toward the Maastricht criteria.

← 2. Other measures also exist including gamma convergence, which measure changes in the ranking of economies over time.

← 3. Heteroscedasticity is when the size of the error term differs across values of an independent variable.