This chapter provides a diagnosis of the main multi-level governance mechanisms and the regulatory policy of Hidalgo, as well as an analysis of subnational governments’ finance of the state and its municipalities. The chapter has four sections. The first presents an overview of the national governance structure and the distribution of competencies between levels of government. The second focuses on the fiscal revenues and expenditures of the State of Hidalgo and its municipalities. The third discusses the State Development Plan and its governance mechanisms. The fourth analyses the regulatory improvement policy and the actions to enhance the business environment in Hidalgo.

OECD Territorial Reviews: Hidalgo, Mexico

Chapter 4. Strengthening Hidalgo’s governance for an effective policy outcome

Abstract

The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

Key findings

1. Despite advancing on decentralisation in Mexico, states are still limited in their financial portfolio. Competencies and responsibilities are not clearly defined and there is an overlap between the levels of government. There is a misalignment between responsibilities allocated to subnational governments and the resources and capabilities available to them, with the federal government still controlling large spending areas.

2. Within the Mexican context, Hidalgo stands in a relatively weak position. The state has the fourth-lowest level of own revenues collection in Mexico and its dependency on federal transfers (90% of the state income) is above the national average. It has created a lack of accountability and low incentives for an effective and prudent fiscal policy.

3. Most of the transfers to Hidalgo stem from earmarked funds (62%), limiting the autonomy of the state and municipal governments, to adapt policies to local needs and circumstances. Furthermore, the non-earmarked transfers are highly volatile which limits subnational medium-to-long term planning.

4. Hidalgo has significant space to increase the fiscal revenues at the state and municipal level. The share of the state tax collection (2.8%) is below the country’s average (4.1%), with a lower collection of payroll and property taxes. High informality rates, low institutional capacity at local level coupled with a small tax base and relatively low levels of tax rates and fees hamper the own fiscal revenues in the state.

5. Property taxes are especially low at the municipal level. During 2012-16, the share of the land use tax in the municipal revenue (3%) was half the average in Mexican municipalities (6%). It is explained by a low enforcement in the update of cadastres and urban development plans and the low efficacy of tax collection.

6. Hidalgo is the state with the sixth lowest level of public investment per capita in Mexico and the existing investments do not target the strategic sectors for the state. At the state level there is no investment in productive projects and at the local level, most of it is allocated to security (96%), with sectors like agriculture or tourism receiving limited resources.

7. Hidalgo has made an important effort in elaborating a comprehensive State Development Plan closely linked to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) objectives. Nonetheless, the plan could be further improved:

State objectives are currently too broadly defined, lack of prioritisation and differentiation between short, medium and long term. This can lead to weaker monitoring and refocusing of public policies.

The strategic pillars bear cross-cutting issues without promoting sharing responsibilities.

Although the programmes are by nature multi-year, the provision of funds does not contemplate a multi-year budget.

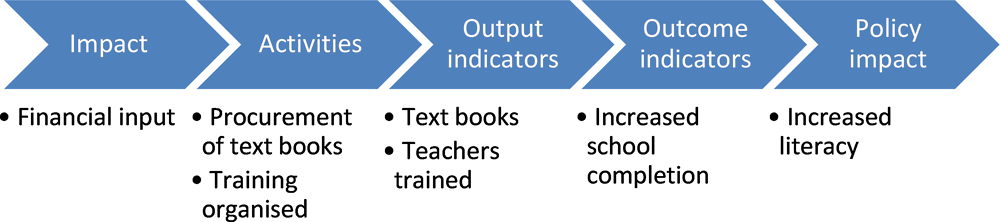

8. Monitoring and evaluation of the State Development Plan (SDP) are made through a mechanism of indicator performance that present some challenges:

The indicators tend to duplicate across secretaries and there is no real sense of transversality and complementarity. It hampers the scope for vertical or horizontal co‑ordination and reduces clarity over the attribution of responsibilities to each secretary and level of government

Priority indicators reflect outputs rather than outcomes. There is no clear differentiation between input, output and outcome indicators.

Indicators lack a clear criterion on fulfilling objectives based on a benchmark with comparable regions, past objectives or a baseline value.

9. Hidalgo has enough fora and institutions to enhance vertical and horizontal co‑ordination within and across the state, although there is no institutional mechanism to incentivise the co‑ordination. The Regulatory Improvement Law and the performance indicators mechanism can be used as a tool for better co‑ordination.

10. The understaffing, retention and motivation of public servants is a challenge in the state. Hidalgo has developed a policy of lean management, by reducing staff in the search for modernisation. However, it needs to be accompanied by strategies to change and make more efficient the operation of the public administration.

11. The State of Hidalgo is advancing on citizen participation and initiatives to promote public finance accountability. The state has set citizen participation as one of the strategic objectives of the State Development Plan. The Citizens Advisory Council of the State of Hidalgo (CCCEH) is enhancing the government-citizen dialogue.

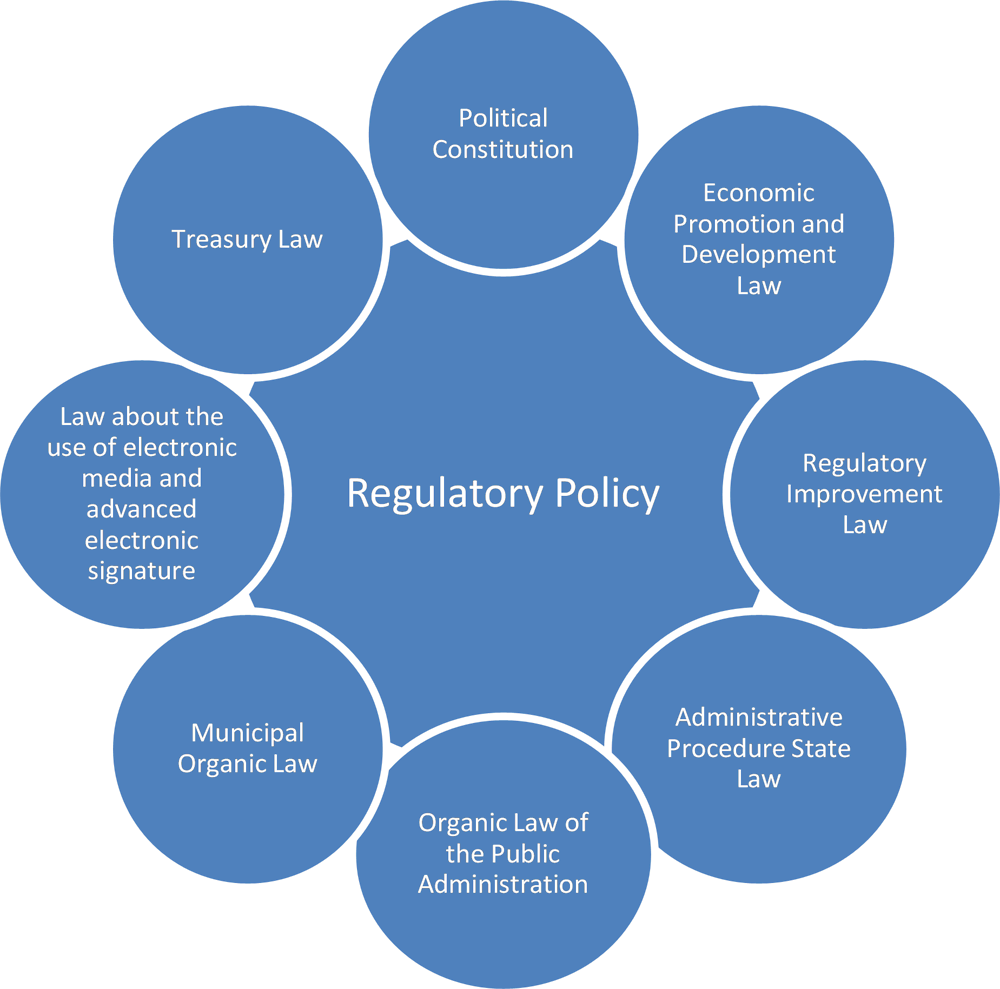

12. The State of Hidalgo developed a Law on Regulatory Improvement that seeks to improve regulatory quality and is consistent with many of the practices adopted by OECD countries. However, it is still missing the elaboration of the subordinating regulation – El Reglamento –, the instruments to analyse draft regulation (RIA) and more clarity on the setup of a State Commission on Regulatory Improvement.

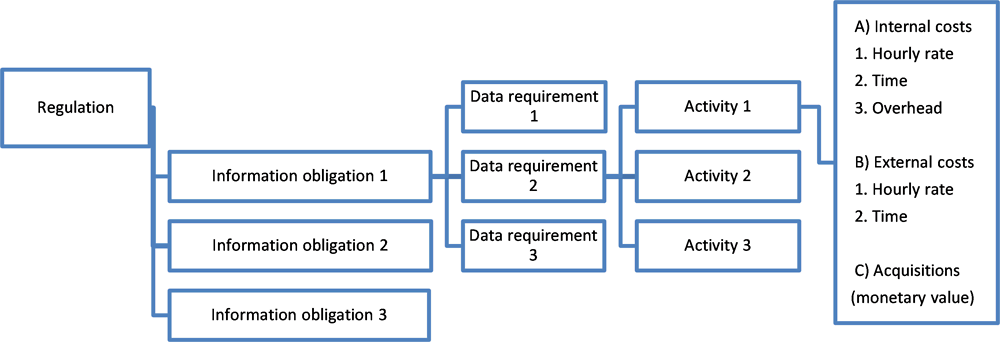

13. The main efforts of Hidalgo on regulatory improvement focus on administrative simplification, with a 100-priority process to be simplified and digitalised. However, simplification requires a formal strategy, which should be based on reducing administrative burdens.

14. The government of Hidalgo has a plan to digitalise the processes on a one-single‑stop shop (Web portal). However, there is no clear classification of the processes and their link with specific economic or citizens activities.

15. Institutional co‑ordination between ministries and agencies with the current office in charge of regulatory improvement is weak. A relevant practice seems to be the co‑ordination with the judiciary power, which must comply with the law on regulatory improvement. It can serve as a good example to be generalised across agencies.

Introduction

Improving the territorial development in a state or municipality depends largely on the institutions, frameworks and processes shaping the territory’s public governance structure. The strength of this structure, how it is managed and its adaptability to changing circumstances are prerequisites to meet state objectives.

This review has stressed the efforts the State of Hidalgo is making to attract investment and increase productivity while attaining inclusive and sustainable growth. The state can unleash economic opportunities based on its favourable geographic location (closeness to the largest internal market), its well-developed infrastructure in the south coupled with a high endowment of natural resources and safety environment. However, the state still requires a clearer policy strategy to match large investment with local capacities and promote policy complementarities to unleash untapped opportunities across the territory. To allow these policies and strategies to be well conceived, applied and financed, Hidalgo needs the right governance and regulatory setting.

This chapter examines the governance and regulatory tools in the State of Hidalgo and provides recommendations to spur the effectiveness, efficiency and inclusiveness of government actions. It argues for the need for greater attention to fiscal management and co‑ordination at different levels of government, the improvement of planning mechanisms and the importance of an efficient regulatory policy with stronger accountability instruments.

The first section begins with an overview of the national governance structure and the distribution of competencies between levels of government. It then examines the fiscal revenues and expenditures of Hidalgo and its municipalities. Next, it discusses the State Development Plan and its governance mechanisms and lastly, it analyses the regulatory improvement policy and actions to enhance the business environment.

The Mexican decentralisation context

Mexico is one of nine federal countries in the OECD.1 It is a presidential state with three levels of government. The President of the Republic, elected for a six-year term, heads the executive branch. At the subnational level, the country is divided into 32 states and each one of them is composed of municipalities. There are approximately 2 457 municipalities in the country, 84 of which are in the State of Hidalgo. The country has experienced several phases of decentralisation, transferring significant competencies to subnational governments particularly in the delivery of education and health services (Box 4.1). Nonetheless, subnational governments have limited margins of manoeuvre because the central government takes most of the strategic decisions and because states and municipalities, due to fiscal imbalances, are strongly dependent on earmarked funds from the central government.

The constitution defines that the states are free, sovereign, autonomous and independent from one another. Mexican states have their own constitutions and can enact their own laws as long as they do not contradict the national constitution. The division of powers in the states is similar to that of the national level, with a governor that is elected for a six‑year term and who is head of the executive branch. Each state, however, has its own electoral calendar. In most of the states (26), the governor election coincides with that of the federal level, while in Hidalgo it occurs 4 years later (the mandate of the current governor is 2016-22). State governments also have their judiciary branch with their own civil and penal codes.

Box 4.1. Overview of Mexican decentralisation

The decentralisation process in Mexico is charged with two centuries of history and conflict. The 19th century saw strong opposition between pro-centralisation and decentralisation governments. In 1857, Mexico was definitively established as a federal government. Despite the constitution of a federal state, the fiscal agreements in the 1920s and 1930s, the hegemony at all levels of government of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI) and the import-substitution development model lead de facto to a highly-centralised political and fiscal model.

The movement towards decentralisation in Mexico was driven by a quest to reduce poverty and inequality and to improve public service provision representation and accountability (Giugale and Webb, 2000[1]). In Mexico, this transition took the form of three main reforms (Cabrera-Castellanos, 2008[1])(i) the creation of the Nacional System of Fiscal Co‑ordination (Sistema Nacional de Coordinación Fiscal, SNCF) in 1980 which clarified the rules of fiscal transfers, centralised VAT collection and sought to avoid double or triple taxation; ii) the constitutional change in 1983, which decentralised functions to the states and municipalities while allowing local governments to have their own resources; and iii) the transfer of health and education services to the states between 1995 and 1998.

Source: Adapted from OECD (2017[1]), OECD Territorial Review of Morelos, Mexico, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264267817-en.

At the third level of government, municipalities are autonomous local governments, but they are governed by state constitution and legislation. A mayor heads the local government and is supported by the municipal council. In 2014, Mexico issued an electoral reform to allow re-election of mayors at the municipal level, if their mandate is not higher than three years. The re-election does not apply to Hidalgo since the term of its mayors is four years, unlike most states where there is a three-year term.

There is an overlap of responsibilities across levels of government in Mexico

Mexico is characterised by a complex system of overlapping competencies and spending responsibilities, particularly in terms of implementation and financing. Federal powers are extensive and sometimes overlap with the responsibilities of states and municipalities. The federal government is responsible for matters relevant to the whole country, such as macroeconomic policy, defence and research and development policy. The sectors for which the federal government is not the single main responsible tend to pose strong multi-level governance challenges since they require two or three inter-dependent levels of government working together.

States are responsible or co-responsible for the delivery of several public services. They are in charge of delivering education and healthcare, co-responsible, with the federal government and municipalities, for poverty alleviation and water management. Tourism, agriculture and industrial policies are also shared between the national level and the states. While states have the primary responsibility for staffing and funding, they have little flexibility in the way money is spent, as most of the funding is earmarked for the payment of salaries (e.g. staff compensation absorbs over 90% of all education spending) (Caldera Sánchez, 2013[2]).

Municipal governments are responsible for local matters primarily. They are in charge of the implementation of social programmes and water distribution, and bear an important role in urban planning through the granting of construction permits, the update of cadastres and development of urban plans. They are also responsible for roads and school maintenance, garbage collection, public lighting, cemeteries, public parks and markets. Infrastructure and transportation are sectors that involve the three layers of government, with the central government mostly responsible for the financing and the subnational levels responsible for the maintenance. At the local level, healthcare and education are two of the most affected areas of overlap. Most of the spending of local governments in these sectors is allocated to staff expenditure, with a limited spending capacity on goods, services and investment.

The lack of clarity in the definition of spending responsibilities yields low incentives for subnational governments to be fully accountable for the public services’ provision. This potentially results in an inefficient provision and poor quality of public service (Caldera Sánchez, 2013[2]).

The imbalance in Mexican fiscal system

Developing a system for local governments to assume both fiscal and political responsibilities is an ongoing challenge in Mexico. Subnational governments (states and municipalities) are responsible for an important share of public expenditure, although they have limited own-revenue resources and low fiscal autonomy. This imbalance creates not only a lack of incentives for own-revenue generation and for effective fiscal policy but also low accountability and responsibility for outcomes.

While subnational governments are relevant for spending purposes, their role on fiscal revenues is quite limited

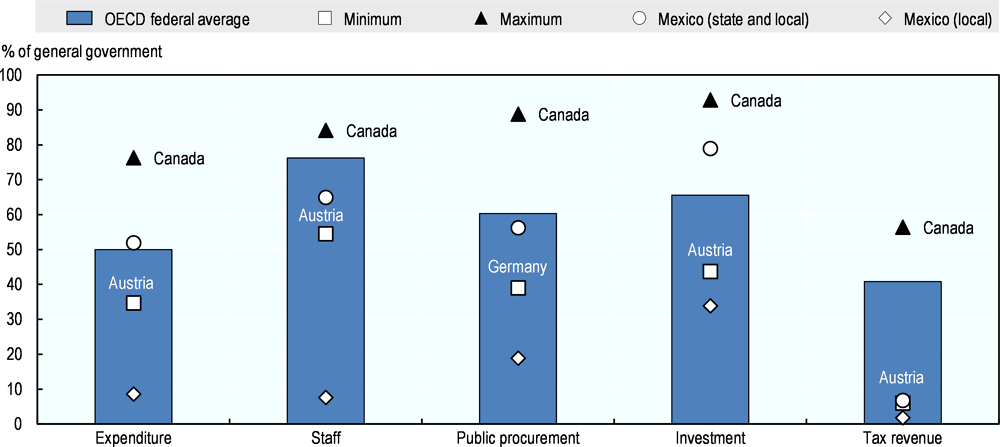

Mexico’s subnational governments have an important role in fiscal matters.

They carry out more than half of the public expenditure (52% in 2015), in line with the average of the 9 OECD federal countries (50%).

They are important public employers (65% of public staff expenditure).

They conduct a big share of total public investment (79%), significantly above the average of OECD federal countries (66%).

Nevertheless, the share of subnational tax revenue in both public tax revenue and total subnational government revenue is among the lowest of OECD federal countries (OECD, 2018[3]). Mexican subnational governments collect only 6% of the tax revenues of the federal government, far below the average of OECD federal countries (41%) (Figure 4.1). The proportion of taxes in total subnational government revenue (7.2%) is the lowest among OECD federal countries and ranks among the last within all OECD countries (OECD, 2018[3]).

The unbalanced assignment of responsibilities across levels of government in Mexico is especially harmful to local governments. Municipal governments have extensive responsibilities on paper but in reality, a quite limited economic role. The share of Mexican municipal expenditure in public spending (9%) is among the lowest of the OECD federal countries (15%). While Mexican municipalities are in charge of providing basic public services and adopting territorial and urban municipal development plans, they often lack enough resources and incentives to update such plans and miss adequate infrastructure and sophisticated tools to collect taxes on top of instruments for guiding spending and measuring success (OECD, 2015[4]).

Figure 4.1. The fiscal role of subnational governments in the OECD and Mexico, 2015

Note: Country names refer to maximum and minimum among OECD federal countries.

Source: OECD (2018[3]), Subnational Governments in OECD Countries: Key Data (brochure), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en.

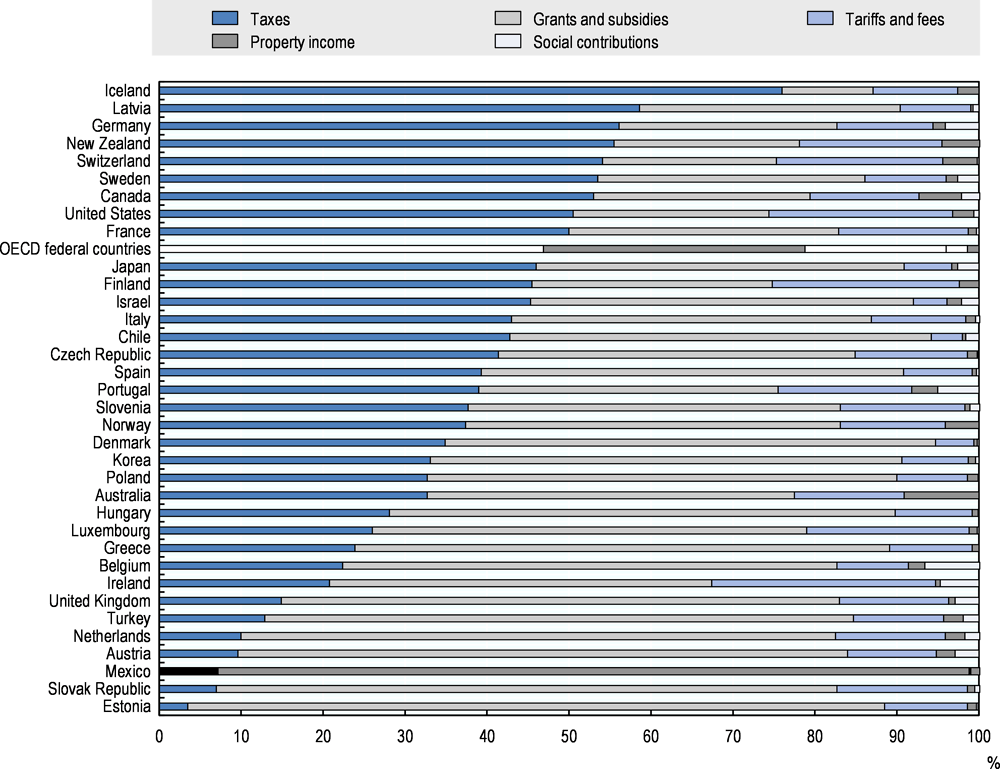

Federal transfers represent the main revenue source of subnational governments. While in federal countries the funding model of subnational governments is largely based on taxation, Mexican subnational governments are almost exclusively funded through grants and subsidies (92% of subnational revenue), whose share is by far the highest in the OECD federal countries (32% in average) (Figure 4.2).

Despite its federal structure and ongoing efforts of decentralisation, Mexico remains relatively centralised. Federal government control large spending areas and the autonomy of municipal government is still severely limited, which makes it the weakest tier of the Mexican government. The recent tax reform of 2014 is a step forward towards improving tax collection of subnational governments, the subnational governments’ spending efficiency and increasing tax powers of the states. In this regard, the recent OECD Economic Survey for Mexico developed some key findings and recommendations (Box 4.2).

Figure 4.2. Subnational government revenue by type, 2015

Source: OECD (2018[3]), Subnational Governments in OECD Countries: Key Data (brochure), http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/region-data-en.

Box 4.2. OECD recommendations on the Mexican fiscal policy

The 2017 OECD Economic Survey issued some assessment and recommendations on the Mexican fiscal policy:

|

Key findings |

Recommendations |

|---|---|

|

Social expenditure is too low to eliminate poverty and make society more inclusive |

- Strengthen social expenditure on programmes to eradicate extreme poverty, such as Prospera - Raise and broaden the minimum pension to expand the old-age safety net |

|

Tax evasion and tax avoidance lower government revenue |

- Co-ordinate the collection of income taxes and social security contributions - Make better use of property taxes - Further broaden income tax bases and remove inefficient tax expenditures |

|

Fiscal data are difficult to interpret on an international basis |

- Fully separate PEMEX from the federal budget when feasible - Present budget documents and fiscal data on both domestic and national accounts standards |

|

Fiscal relations with state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are distortive |

- Normalise the taxation of SOEs by shifting to a tax regime similar to that of the private sector |

Source: OECD (2017[5]), OECD Economic Surveys: Mexico 2017, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-mex-2017-en.

The Fiscal system in Hidalgo

The current government took office in 2016 within a difficult financial scenario of low levels of own revenue collection, increasing debt and interest rates (growth of 34% between 2011 and 2016) and a weak fiscal co‑ordination with local governments. The state has been conducting actions to attain an efficient fiscal system, including a cut in unnecessary expenses and a lean management strategy. However, much more is to be done to achieve efficient fiscal revenue and spending.

Fiscal revenues

The System of Fiscal Coordination (SFC) establishes the regulation on the own resources that state and municipal governments can levy. Taxes on income, consumption, production and services are categorised as national taxes and are partially transferred to the subnational governments. States and municipalities are autonomous in setting their own tax rates and bases over payroll tax, vehicle taxes, property taxes and user fees. These taxes are designed at the state level and approved by the state congress.

Revenue sources of subnational governments in Hidalgo, as in Mexico, can be divided into four major groups: i) own resources; ii) non-earmarked transfers or revenue sharing (transfer participation – participaciones); iii) earmarked funds (aportaciones) and matching transfers (convenios); and iv) other sources of income such as revenues from state-owned enterprises and debt, among others.

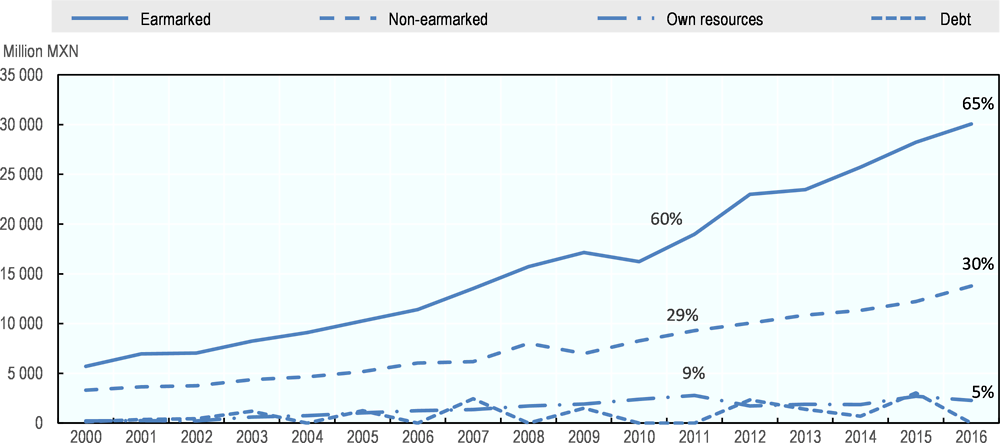

Similarly to other Mexican states, the main income of the State of Hidalgo comes from federal transfers. Between 2012 and 2016, 90% of Hidalgo’s revenues stemmed from transfers (62% earmarked and 28% non-earmarked), while own revenues represented 5% and debt 3.6%. This dependency poses not only problems in long-term planning, due to the transfers’ fluctuation, but also creates negative incentives for the mobilisation and co‑ordination of subnational government revenue. Furthermore, the budget negotiation of some transfers tends to be very complex and prone to political discretion.

Between 2000 and 2016, Hidalgo’s revenues have experienced a five-fold increase (from MXN 9.3 billion to MXN 46.1 billion), in line with growth at the country level. However, the composition of the state revenue’s sources has experienced important changes in recent years. While the share of own resources has decreased since 2011 (from 9% in 2011 to 5% in 2016), the revenues from earmarked transfers have gained prominence within Hidalgo’s revenues (from 60% in 2011 to 65% in 2016) (Figure 4.3). As discussed in the next section, most of the drop in own revenues has been explained by a decrease in the amount collected from advantages and taxes (specifically property tax).

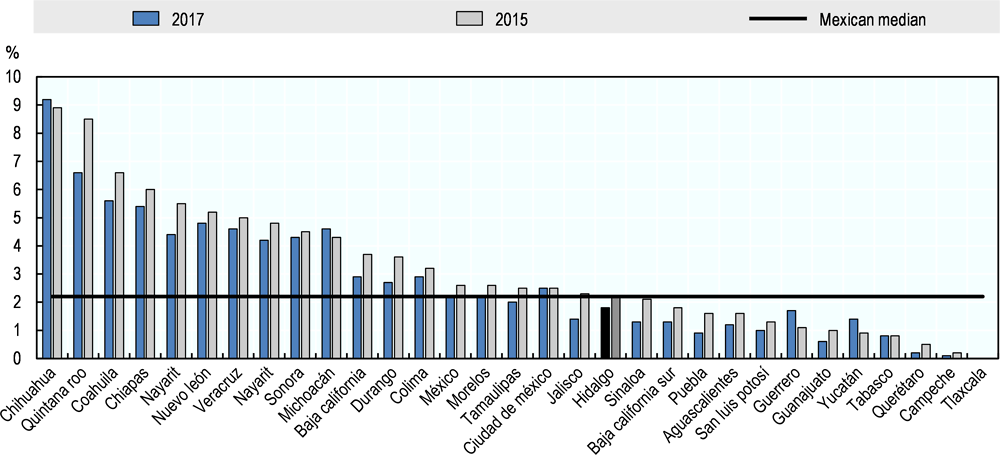

The overall debt level has decreased in recent years from 2.2% of the state gross domestic product (GDP) in 2015 to 1.8% in 2017. In fact, in 2017, Hidalgo ranked as the 13th state with the lowest debt ratio to GDP in the country, below the median of Mexican states (2.2%) (Figure 4.4).

Figure 4.3. Evolution of revenues in Hidalgo by type

Note: Data labels represent the share in total revenue.

Source: INEGI (2016[6]), INEGI Databases, http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/microdatos (accessed 15 June 2018).

Figure 4.4. Public debt ratio to GDP per Mexican state, 2017 and 2015

Source: INEGI (2016[6]), INEGI Databases, http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/microdatos (accessed 15 June 2018).

The central government has long sought to increase levels of own resources in the states by increasing taxation powers and incentives. The 2007 fiscal reform aimed to transfer the ability to levy a surcharge on income taxes and levy a sales tax as well as taxes on diesel, gasoline and vehicle ownership or use. Further incentives such as including fiscal efforts in the formulas of several non-earmarked funds have been also tested (Caldera Sánchez, 2013[2]). The recent 2014 tax reform in Mexico allowed states to charge income tax on payrolls and, together with municipalities, fully participate in the income tax of their administrative staff. It also established an incentive for municipalities to transfer the administration of the property tax to the state government (OECD, 2017[5]). Nonetheless, in Hidalgo, such changes have not yet fully produced positive effects, leaving the share of own resources at similar levels as they were before the reforms (see Figure 4.3).

Hidalgo has unexploited potential to increase own revenues

In Hidalgo, own resources are divided into taxes, duties, products, special assessments and advantages. In 2016, most of the own resources came from taxes and duties:

Taxes represent the largest share of own revenues in Hidalgo (62%). More than half stem from payroll taxes (58% over total taxes), followed by the taxes for public works (8%). Instead, property tax in Hidalgo represented just 3% of total taxes.

Revenues from duties account for the other big share of own revenues (25%). They refer to the charge for services such as civil registry, public property registry, certificates, licences, permits, and roads and water rights.

Revenues from products (7%) refer to the use or sale of goods and other products such as the lease of public property, financial return from assets in firms or the return on official publication.

Advantages (5%) refer to revenues from fines and penalties, donations, contributions and others.

Special assessments (1%) are collected from charges to people and business that benefit directly from public works.

At the municipal level, taxes also represent the largest source of own resources (49%). Most of the taxes (72%) come from property tax and transfer tax. Duties represent the other important bulk of own resources for local governments (36%). It refers mainly to license and permits, where the most prominent are construction licences, and the charges from the public services provided by the municipalities (water, public lighting or garbage services). The share of advantages (fines and penalties) represent the third highest own revenue for municipalities (14%).

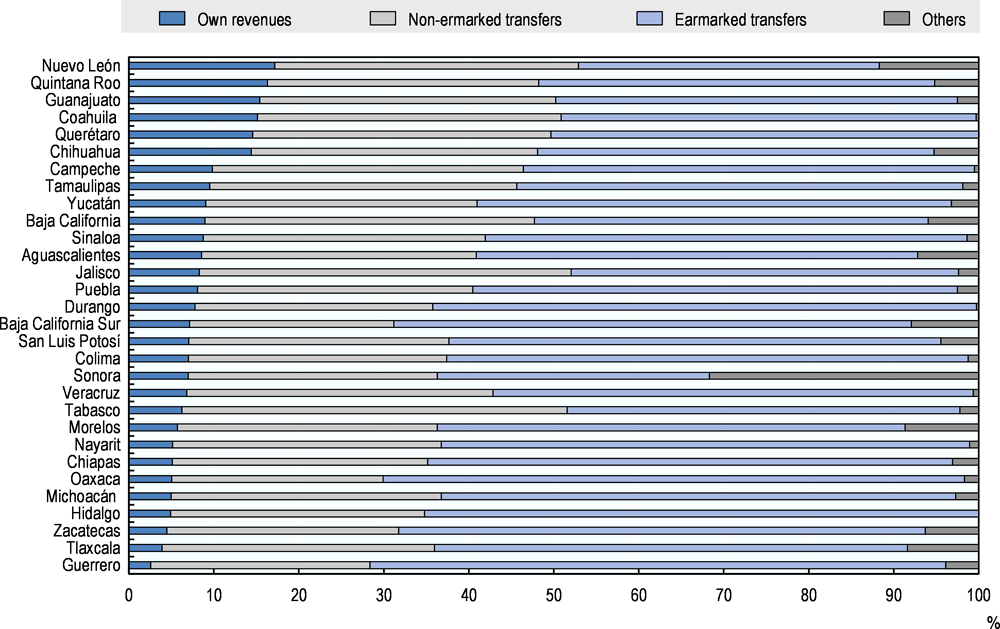

Hidalgo ranks as the state with the fourth-lowest share of own revenues collection in Mexico (Figure 4.5). In 2016, just 5% of its income came from this source, far below the country average (9%). These figures have been, on average, similar since 2012. The relatively low share of revenue collection is also reflected at the municipal level. In average, Hidalgo’s municipal governments collect 15% of their total revenues, below the average of Mexican municipal governments (21%). At the country level, the Mexican states with the highest share of own revenue collection, Nuevo León or Quintana Roo (17% and 16% respectively), can be characterised by a high degree of development (with higher levels of GDP per capita) and urbanisation (Caldera Sánchez, 2013[2]).

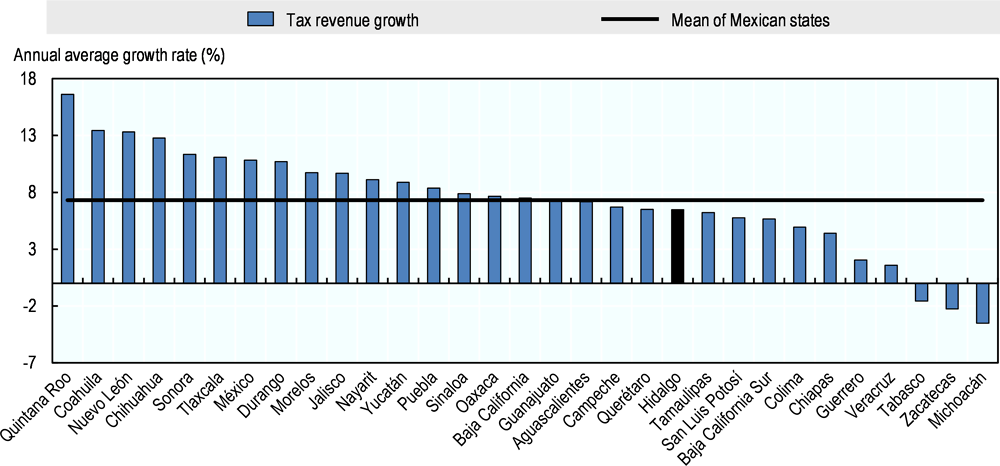

Out of own resources, the State of Hidalgo has significant scope to improve collection in taxes. Between 2012 and 2016, the average share of tax collection in Hidalgo (2.8%) was lower than the country average (4.1%). Moreover, the growth of tax collection in the state during this period (6%) has been below the country average (7%), ranking as the 12th state with a lower growth rate of tax revenue in the country (Figure 4.6). This phenomenon is mainly explained by the drop of the property tax’s collection in the state (-24% annual average), which contrasts with a positive average growth across Mexican states (average of 5%).

Figure 4.5. Sources of fiscal revenues across Mexican states, 2016

Source: INEGI (2016[6]), INEGI Databases, http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/microdatos (accessed 15 June 2018).

Figure 4.6. Growth of tax revenue in Mexican states between 2012 and 2016

Source: INEGI (2016[6]), INEGI Databases, http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/microdatos (accessed 15 June 2018).

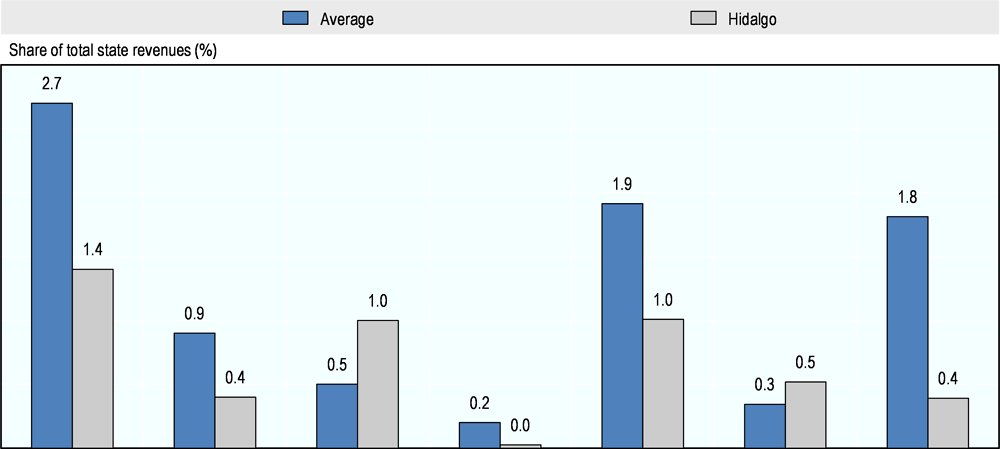

Payroll and property taxes are especially low in the state. The share of payroll (1.4%) and property taxes (0.4%) over Hidalgo’s total revenue is lower than the average share across Mexican states (2.7% and 0.9% respectively) (Figure 4.6).

Payroll tax. The low collection of this tax in the state can be explained by the low tax rate and the high labour informality rate. In Hidalgo, the payroll tax rate ranges from 0.5% to 2%, while the national average is between 2% and 3% (Government of Hidalgo, 2017[7]).

Property taxes. The level of this tax at the state level is mainly affected by the low share of the ownership and use of vehicles tax. It contributes to 6% of the whole tax revenue, far below the figure of the country average (12%).

During 2012 and 2016, Hidalgo also underperformed in the collection of special assignments, duties and advantages (Figure 4.7). Within duties, the revenue from vehicles (0.6% over total revenue) is below the country’s average (1.4%). The state instead has a relatively better performance in the levy of products, which referred to specific selling of public assets.

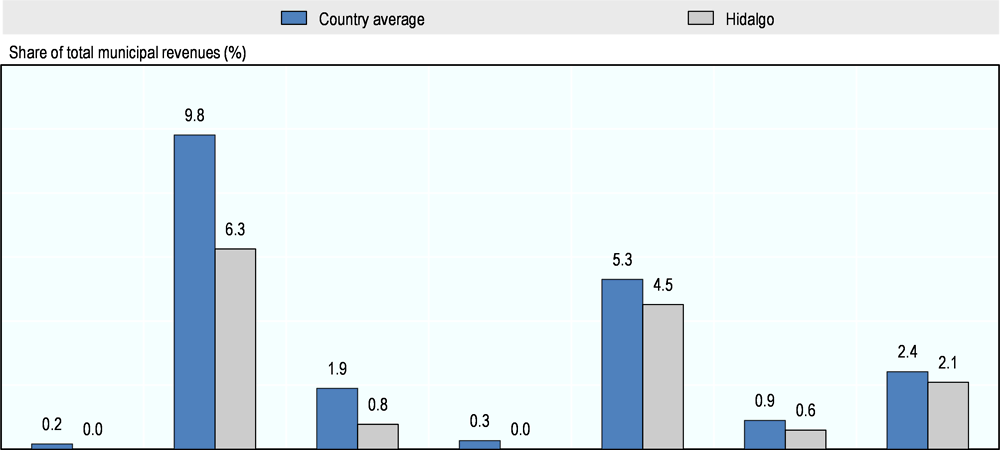

At the local level, the municipalities underperform in the collection of most of the own revenues’ sources. During 2012 and 2016, the proportion of property tax in the revenue of Hidalgo’s municipal governments was lower (6.3%) than in the average of the Mexican municipalities (9.8%). In particular, the weight of the land use tax in Hidalgo’s municipal revenue (3%) was half the average in the country (6%). Duties, products and advantages at the local level also underperformed in comparison to the average of the country (Figure 4.8). Within duties, the municipalities of Hidalgo have a lower share on charges for the use and delivery of water (4% of the duties) and public lighting (2%) than the country average (8% and 10% respectively).

Figure 4.7. State own resources for Hidalgo and Mexico, average, 2012-16

Source: INEGI (2016[6]), INEGI Databases, http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/microdatos (accessed 15 June 2018).

Figure 4.8. Municipal own resources for Hidalgo and Mexico average, 2012-16

Source: INEGI (2016[6]), INEGI Databases, http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/microdatos (accessed 15 June 2018).

Hidalgo can increase the collection of own revenues by carry out a more efficient fiscal collection, improving law enforcement and broadening the tax base with special attention to the level of taxes.

In the case of payroll taxes. Hidalgo should revise the payroll tax rate, which is significantly lower than the country average. In terms of property tax, Hidalgo could make a greater use of this tax by considering the following actions:

Encourage local governments to develop and update cadastres, property registries and urban plans. As mentioned in Chapter 3, just a few municipalities have updated the cadastre (7 out of 84), either because of lack of resources and institutional capacities or low political incentives. Some municipalities even lack a clear traceable official registry of the quantity, value and ownership of properties. The low property tax is not just a problem in Hidalgo but the whole country. Mexico has a relatively low share of property tax (2% of total revenues in 2015) compared to Latin America (3.4%) and OECD countries (5.8%) (OECD, 2018[8]).

Hidalgo should further benefit from the policy introduced in the 2014 tax reform that allows states to manage the property tax of municipal governments, especially of the poorest municipalities.

The state could also support municipalities with the training of personnel and capacity-building programmes for local governments.

The digitalisation of urban development plans and exchange of digital information about cadastres would facilitate the process of updating the cadastres (see the fourth section in this chapter).

Concerning duties and advantages, improvements in the implementation of the rule of law (fines and charges) and a review of fees could lead the state and municipalities to increase the level of duties and advantages. Municipal governments could benefit from closely monitoring the collection of vehicle fines and parking area charges as well as the fees from the provision of public services, especially water and public lighting. The issue of the water tariff is also a challenge for the whole country. In Mexico, water tariffs are low compared to OECD countries, which may result in overexploitation of water resources, providing a limited revenue for a sustainable provision of the resource (Caldera Sánchez, 2013[2]). The state, jointly with the water commissions, can play a major role in revising and supporting the tariff setting at the local level.

Additionally, the high level of labour informality is hindering the capacity to increase own revenues in the state, especially in poor municipalities. Informality affects the amount of taxes the government can collect, which in Hidalgo is especially harmful to payroll and property taxes in poor municipalities. Labour informality in Hidalgo (74% of the occupied population) is the 4th largest in the country. Alongside agriculture and the informal sector, the public sector plays a key role in the high level of informality in the state (see Chapter 1). In this matter, the State of Hidalgo needs to lead by example and reduce informal contracts in the public sector. It should also involve municipal governments to conduct a policy of informality reduction in public administration.

Evasion is also a challenge for the state and the country. The recent OECD economic survey for Mexico stressed that tax evasion in Mexico is high since firms and business across the country tend to understate labour costs to the social security system (IMSS) and overstate them to the tax administration (OECD, 2017[5]). In this case, Hidalgo can benefit from merging or further improving the co‑ordination between income and social security administrations to reduce tax evasion, by promoting a single tax ID number for firms, for example.

The weak incentives to increase tax collection and the limited public information available on spending patterns are other challenges to mobilising own revenues in Hidalgo. The dependency on transfers has had a negative effect on local tax collection. Given the high political cost of increasing taxes, local politicians may be tempted to rely on federal transfers to finance public service delivery (Caldera Sánchez, 2013[2]). Since the federal transfers take into account the level of tax collections to assign the resources, increasing the requirements of own resources collection within the transfer formula should boost incentives for local governments to increase local taxes. Mechanisms of naming and shaming can be established in order to single out which municipalities are improving their collection of own resources and increasing public investment in strategic projects. This can be done by replicating and expanding indicators such as the Productivity Indicator for Municipal Governance (developed by the Comunidad Mexicana de Gestión Pública) (2016[9]). This indicator measures the relationship between the quality of public services, tax collection capacity (property tax) and its bureaucratic cost.

Furthermore, encouraging municipalities to publish fiscal spending in a timely manner will improve accountability and increase trust from citizens on the use of their taxes. Involving the community in fiscal decisions can boost awareness in the importance of paying taxes. Awareness of tax benefits coupled with tax simplification programmes and subsidies can motivate citizens to declare and pay taxes and fees. The case of Quintana Roo and Brazil can be a guide for the state (Box 4.3).

Box 4.3. Incentives to pay taxes

Brazil. In 2006, the Brazilian government introduced a simplified tax and regulation system for micro- and small companies, called Simples Nacional. The rationale was to lower tax compliance costs for small firms and encourage them to move into the formal sector.

Simples Nacional combines a range of taxes in a single monthly collection. Taxes that are included are the most important federal taxes and contributions. Microbusinesses are defined as individuals or corporations with gross revenue less than or equal to BRL 240 000 (USD 120 000) in each calendar year. Participation in the system is optional, and firms have to apply through a website. All states and municipalities must offer Simples Nacional. However, small states can adopt a different enrolment threshold for local tax collection.

In addition to Simples Nacional, a special programme encourages individual entrepreneurs (IEs) to become formal. IEs must first register with Simples Nacional. They cannot earn more than BRL 36 000 (USD 18 000) per year, must work alone or have only one employee, and cannot own or be a partner or manager of another company. IEs are recorded in the National Register of Legal Entities, which facilitates the opening of a bank account, loan applications and issuance of invoices. IEs benefit from a simplified tax system. They are exempt from federal taxes and pay only a fixed monthly amount. In return, IEs have access to benefits such as a retirement pension, sickness and maternity leave and insurance for workplace accidents.

Simples Nacional is reported to have contributed to the observed decline in informality. According to official data, the size of informal labour markets declined steadily to 49% of total employment in 2010 (from 52% in 2006). However, it remains hard to disentangle the effect of Simples Nacional from that of buoyant economic performance. There is also evidence that the IE programme has encouraged unregistered workers to become entrepreneurs.

Quintana Roo, Mexico. Between 2012 and 2016, Quintana Roo has been the state with the highest growth of tax collection in the country (16% annual average growth). This state has developed a series of strategies to boost the tax of use and ownership of vehicles. During the first semester of 2017, the state issued a 100% subsidy for the payment of driver's license certificate and a reduction of MXN 335 for the renewal of car plates (a process that must be done every 3 years). During the first 2 months of the subsidy, the state received 140 769 applications from citizens.

The state has also subsidised 100% the cost of changing car ownership. To access the subsidy, the person must meet some requirements: payment of the tax on alienation of vehicles between individuals; circulation card and plates; invoice that proves legitimate property; recent proof of address (electricity, water or property receipt); current official identification; and Federal Taxpayers Registry (R.F.C).

Sources: Brazil case adapted from Arnold, J. (2012[10]), “Improving the Tax System in Indonesia”, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5k912j3r2qmr‑en; Simples Nacional (n.d.[11]), Website, (accessed August 2018), http://www8.receita.fazenda.gov.br/SimplesNacional; State Government of Quintana Roo (2017[12]), SEFIPLAN http://cgc.qroo.gob.mx/en-dos-meses-sefiplan-ha-recibido-casi-141-mil-tramites-para-cambio-de-placas/.

Improving the management of federal transfers

The system of federal transfers in Mexico is comprised of earmarked and non-earmarked transfers. Overall, most Mexican subnational governments strongly rely on transfers from higher levels of government. It creates disincentives for sub-national governments to exploit their own revenue potential and build up their administrative capacities. Because of the volatile nature of fiscal transfers, such reliance often limits the subnational of medium-to-long term investments and renders them vulnerable in times of economic difficulty, as also seen in other countries such as Chile and Peru (OECD, 2014[15]); (OECD, 2016[16])). However, some intergovernmental transfers tend to be less distorting than others. OECD work provides a number of guidelines that can help governments design less distortive grants (Box 4.4). Non-earmarked grants, for example, tend to provide subnational governments with more autonomy to generate cross-sectoral policies or co‑ordinate policies with other administrative jurisdictions.

Hidalgo has a higher dependency from fiscal transfers than the average of Mexican states. Between 2012 and 2016, the share of federal transfers in Hidalgo’s annual fiscal income (90%), was above the average in Mexican states (82%). Such dependency has increased throughout the years from a share of 88% in 2012 to 95% in 2016. Most of the transfers in the state were earmarked (62% of the fiscal income), showing a higher dependency on this type of transfers than the average of the country (51%). Instead, Hidalgo has a relatively low share of non-earmarked transfers (28%) compared to the country average (31%).

The high dependency on transfers is mirrored at the municipal level. From 2012 to 2016, local governments received on average 83% of their fiscal income from transfers, above the average of Mexican municipalities (71%). Local governments experience, on average, a smaller dependency on earmarked transfers (47%) than the State of Hidalgo, although more than the national average (37%). Contrary to the state level, the share of transfers in local governments has been, on average, more stable during the last years. The fact that Hidalgo is relatively highly dependent on transfers is not surprising since they are based on the income of the state. However, as seen before, over-reliance on transfers can create negative incentives to change status and increase own revenues.

Box 4.4. The efficiency of intergovernmental grants

The table below summarises the efficient use of the various types of grants. The concrete aims are classified in terms of the general purposes of subsidisation, equalisation and financing. These, in turn, can be distinguished according to whether: i) the central government takes the initiative to impose or influence subnational service provision or investment (e.g. delegation of functions); or ii) the subnational government itself takes the initiative. The instrument column indicates the various types of grant instruments available, as well as some regulatory instruments that may achieve more efficiently the aims for which grants are often used. Discretionary grants are mentioned as a possible instrument for co-funding purposes. Co-funding arrangements are used in some countries to finance projects with objectives that are hard to achieve using matching grants and where both central and subnational governments have to be committed. The table should not be seen as a prescriptive blueprint since much depends on institutional architecture and country context. Nonetheless, it provides a framework that can serve as a starting point for thinking about the way grants are designed and used.

Table 4.1. Lessons for efficient use of grant instruments

|

Imposed programmes or standards |

Compensation of spill-overs |

Temporary projects and programmes |

Basic services |

Fringe services |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Financing |

||||

|

Extension of subnational tax base |

X |

X |

||

|

Non-earmarked general-purpose grants |

X |

X |

||

|

Non-earmarked block grants |

X |

|||

|

Earmarked discretionary grants |

X (co-funding) |

|||

|

Earmarked matching and non-matching grants |

(X) |

X (risk sharing) |

||

|

Subsidisation |

||||

|

Earmarked matching grants |

X (national spill-overs) |

X (experiments) |

||

|

Imposition of co-operation |

X (regional spill-overs) |

|||

|

Equalisation |

||||

|

Imposition of horizontal grants |

X |

X |

||

|

Non-earmarked general-purpose grants |

X |

X |

Sources: For table: Bergvall et al. (2006[17]), Intergovernmental transfers and decentralised public spending, OECD Journal on Budgeting vol 5/4;

OECD (2009[13]), Regions Matter: Economic Recovery, Innovation and Sustainable Growth, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264076525-en.

Non-earmarked transfers lack clarity and are volatile

Non-earmarked transfers, also called tax sharing revenues (participaciones), do not imply specific obligations in the spending of states and municipalities, giving more freedom for their allocation. These transfers intend to allocate resources proportionally to the participation of the states in the economic activity and to their tax collection effort. Resources are transferred as general purpose resources to Hidalgo through funds and shared taxes under the so-called Ramo 28 (see Box 4.5). The central government collects the shared taxes, agreed upon the system of fiscal co‑ordination, and distributes them to states and municipalities. The main shared taxes are income taxes, value added tax (VAT), oil and mining revenues or taxes on new vehicles.

Non-earmarked funds (28%, 2012-16) are the second source of revenues in Hidalgo. The main fund to channel these transfers is the General Participations Fund (Fondo General de Participaciones – FGP), accounting for over 72% of non-earmarked transfers. The resources coming from the fund are allocated to the states based on different criteria, where the most relevant is the state gross domestic product (GDP) growth (60% of weight), followed by the local revenue growth (30%) and local revenue level (10%). Despite the former criteria, as seen before (Figure 4.9), the mechanism has had a limited effect in the increase of Hidalgo’s own revenues.

At the municipal level, local governments receive most of their non-earmarked transfers from the FGP (56%), followed by the Municipal Support Fund (FFM) (31%). According to the Co‑ordination Law of Hidalgo, the state must transfer 20% of FGP resources and other shared taxes to municipalities (in 2016 it transferred exactly 20%). The law also establishes the distribution criteria to the municipalities, which in the case of the FGP (and another 2 funds IEEP and taxes from new vehicles) and is based on population (40%), level of marginalisation (30%), the collection of property tax and water charges (10%), tax collection growth (10%) and number of communities per municipality (10%). Other funds and shared taxes have their own distribution formulas. The lack of clarity in the allocation criteria (e.g. the discretion to allocate funds over the 20% of FGP) and the variety of formulas across the funds can lead to rent-seeking and hampers investment planning at the local level.

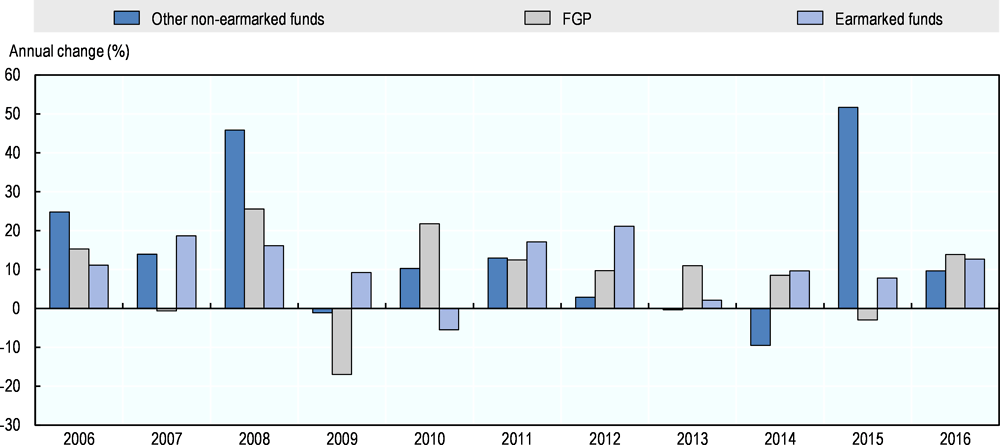

The non-earmarked transfers are subject to variation and present high volatility (Figure 4.9). The standard deviation of the non-earmarked transfers’ growth (11%) is higher than the one of earmarked transfers (8%). Non-earmarked funds are heavily dependent on the performance of the national and global economy, especially when oil and mining prices are concerned. Although the Fund for Revenue Stabilisation of States (Fondo de Estabilización de los Ingresos de las Entidades Federativas – FEIEF) helps mitigate such variations, the volatility of the transfers is still high, which tends to limit the long-term strategic investments of subnational governments.

Figure 4.9. Change of non-earmarked and earmarked sources in Hidalgo

Source: INEGI (2016[6]), INEGI Databases, http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/microdatos (accessed 15 June 2018).

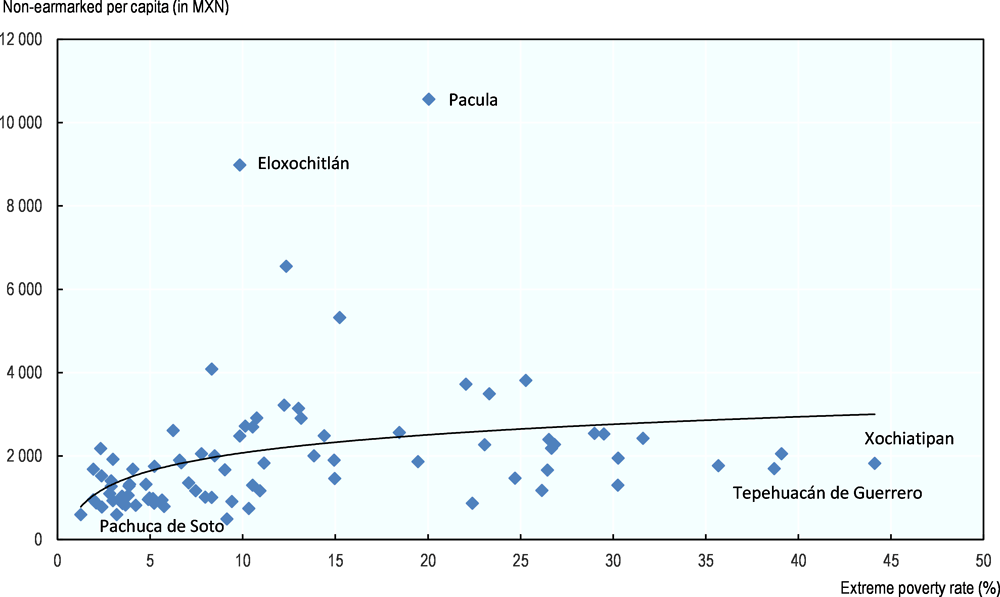

The non-earmarked transfers could be further used to decrease the level of inequality within Hidalgo. Since these transfers are mainly allocated on the basis of local tax efforts and population (i.e. the FGP), large municipalities with higher institutional capacity are receiving more resources than the poorest ones. In 2016, 22 municipalities (out of the 84) received 50% of the non-earmarked transfers. The municipalities receiving most of the transfers are not always the ones with lower poverty rates (Figure 4.10). Although, in theory, the distribution of earmarked transfers should be used to compensate this distortion, as seen in the next section, earmarked transfers’ distribution has ample room for improvement.

Box 4.5. Non-earmarked transfers (participaciones federales Ramo 28)

Non-earmarked transfers consist of funds and shared taxes that are collected by the federal government and then redistributed to the state and the municipalities. The revenue’s sources of non-earmarked transfers for Hidalgo are presented below (selected):

|

Fund |

Purpose |

Funding |

Distribution criteria |

Recipient |

% Ramo 28 (2016) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fondo General de Participaciones (FGP) |

Revenue sharing with states and municipalities |

20% of RFP |

State GDP growth (60%); local revenue growth (30%); local revenue level (10%) |

State and municipalities |

74 |

|

Fondo de Fomento Municipal (FFM) |

Revenue sharing with municipalities |

1% of RFP |

Municipal revenue (property tax and water fees) weighted by state population |

Municipalities |

8 |

|

Fondo impuesto sobre la renta |

Revenue sharing with municipalities |

100% of income tax |

Collection of state’s tax |

Municipalities |

6 |

|

Fondo de Fiscalización (FOFIE) |

Incentive for enforcement of tax laws |

1.25% of RFP |

Measures of local efforts of enforcement of tax laws |

State and municipalities |

4 |

|

Incentives over the IEPS on gasoline and diesel |

Revenue sharing with states and municipalities |

Nine-elevenths of the local gasoline tax collection |

Participation of state in gasoline and diesel consumption |

State and municipalities |

4 |

|

Fondo de Extracción de Hidrocarburos (FEXHI) |

Compensate for oil and gas extraction |

0.6% of main oil royalty |

Oil and gas production |

State and municipalities |

1 |

|

Impuesto Especial sobre la Producción y Servicios (IEPS) |

"Sin tax" revenue sharing with states and municipalities |

20% from tax to beer and alcohol; 8% tobacco |

Percentage of taxes on tobacco, beer and alcohol relative to the national average |

State and municipalities |

4 |

|

Fondo de compensación (FOCO) |

Compensate the 10 poorest states |

Two-elevenths of the local gasoline tax collection |

Opposite of nonoil GDP |

State and municipalities |

- |

Note: RFP stands for Recaudación Federal Participable, the pool of federal revenues that is shared with states and municipalities. It includes income tax, VAT, all other federal taxes and oil revenues. It does not include revenue from public enterprises, federal government funding and certain other sources of non-tax revenue. States are required by law to share at least 20% of these resources with municipalities. Other shared taxes not included in the table are specific incentives over IEPS, participation from municipalities that conduct external trade and shared tax on new vehicles.

Source: CEFP (2017[14]), Recursos Identificados para el Estado de Hidalgo en el Proyecto de Presupuesto de Egresos de la Federación 2017, Centro de Estudios de la Finanzas Publicas.

Figure 4.10. Non-earmarked transfers per municipality and poverty rate, 2016

Source: OECD calculations based on INEGI (2016[6]), INEGI Databases, http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/microdatos (accessed 15 June 2018).

Earmarked transfers can aim for further equalisation and predictability

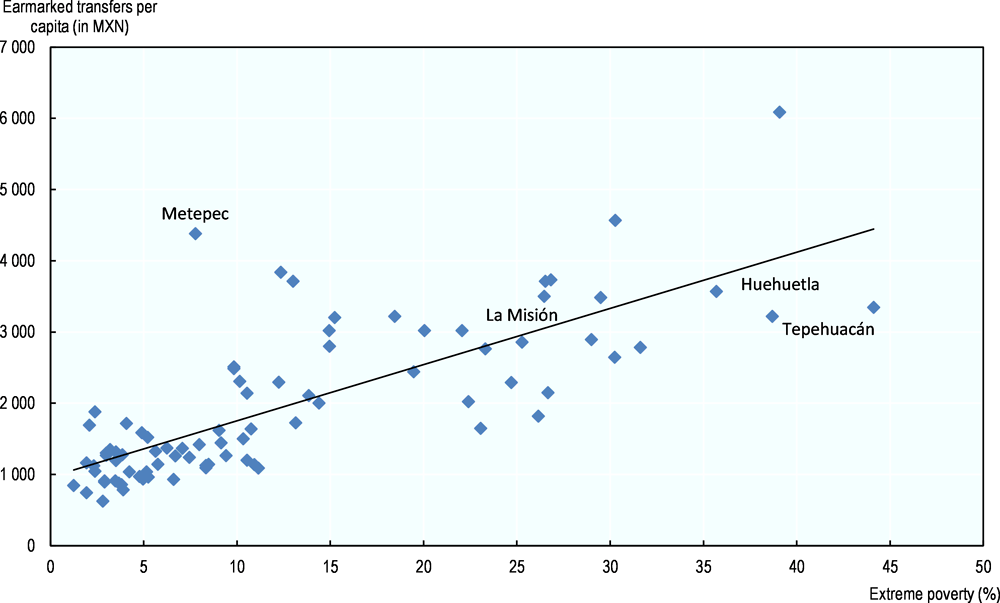

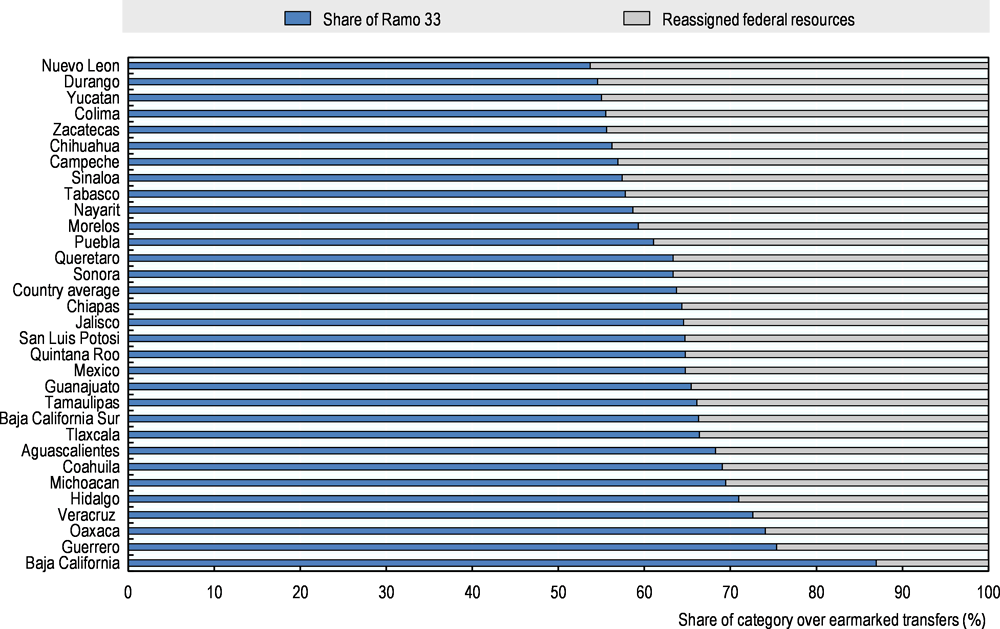

Earmarked transfers, the largest revenues in the State of Hidalgo (65% of total revenue) and in its municipalities (51%), can be divided into 2 main groups: those under a fund called Ramo 33 (71%) and those under reassigned funds (29%). Funds transferred under Ramo 33 focus mainly on education and health. These resources are transferred to states and municipalities under a specific formula that seeks similar per capita levels of transfers per municipality by taking into account both the original economic condition and incentives for improvements. The State of Hidalgo transferred 15% of Ramo 33’s resources to municipalities through the Funds of Infrastructure and Support to Municipalities. These resources represent, on average, 68% of the earmarked transfers in local governments. The earmarked transfers are intended to have a stronger equalisation effect among municipalities, which is not always met in Hidalgo. For example, as Figure 4.11 depicts, some municipalities in Hidalgo, such as Metepec, receive more resources than municipalities with double the poverty rate.

Figure 4.11. Federal transfers per capita and extreme poverty in Hidalgo’s municipalities

Note: Federal transfer rates are from 2016. Extreme poverty rate is from 2015.

Source: OECD calculations based INEGI (2016[6]), INEGI Databases, http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/microdatos (accessed 15 June 2018).

The transfers from Ramo 33 have a relatively high prominence in Hidalgo’s revenue. Hidalgo receives 70% of earmarked transfers from Ramo 33, above the average share in the country (66%) (Figure 4.12). From the different Ramo 33 funds, the Fund for Education is the one that channels most of the transfers to Hidalgo (73%), followed by from the Fund for Health Service (16%). The criteria for the transfers of education to the states is mainly based on the share of public student enrolment in the state’s spending on education and quality of education.

Most of the funds transferred through Ramo 33 give subnational governments little room for manoeuvre. In the case of education, 98% of the money transferred covers the financing of teachers’ salaries, giving little scope for subnational governments to assign funds to other priorities within this sector. Furthermore, the lack of quality and reliability of data definitions within the distribution criteria (e.g. quality of education) makes the improvement of the allocation difficult and the support to the incentive structures built into the funds (OECD, 2017[1]).

Reassigned resources, the other important source of earmarked funds, are determined by political agreements. In 2016, reassigned resources accounted for 30% of the earmarked resources in Hidalgo, slightly below the country average (34%). These transfers stem mostly from what are deemed to be unexecuted resources and under-estimation of income by the central government. Most of these transfers take the form of matching transfers or agreements (convenios de decentralización) agreed upon between ministries and agencies, and the different states and municipalities. These agreements are mostly used for investments intended to improve the delivery of public services.

Figure 4.12. Source of federal earmarked funds

Source: INEGI (2016[6]), INEGI Databases, http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/microdatos (accessed 15 June 2018).

Education, culture and social security are the sectors that receive most of the reassigned transfers. The agreement for education and culture (39% of total reassigned resources) allocates a large proportion of resources to strengthen higher secondary education. In the case of the agreement for health and social security (18%), almost all the resources are dedicated to health with a low proportion allocated to social security.

Reassigned transfers are subject to political bargaining and do not necessarily create incentives to carry out efficient revenue collection. High reliance on such funds may bear significantly negative impacts due to the discretion that is applied in their assignment. The transfer of these funds is in theory subject to the reassignment of the central government to match the objectives of the national development plan. However, in practice, their distribution is subject to strong political bargaining and there is lack of transparency in their allocation (Caldera Sánchez, 2013[2]). These funds do not improve incentives to increase own revenues, planning or link resources more closely to the budgetary mechanisms. These transfers are however subject to higher accountability and control from federal government, given their contractual nature.

Fiscal expenditure in Hidalgo has a limited space for own decisions

Public expenditure in Hidalgo is strongly linked to the responsibility attached to decentralisation system in Mexico. The transfer system leaves Hidalgo relatively little scope for resource allocation. After distribution, non-earmarked resources allocated to municipalities (8% of total income in 2016) and earmarked transfers (65% in 2016), the State of Hidalgo disposes of 36% of the income to current expenditures, financing capital and investments.

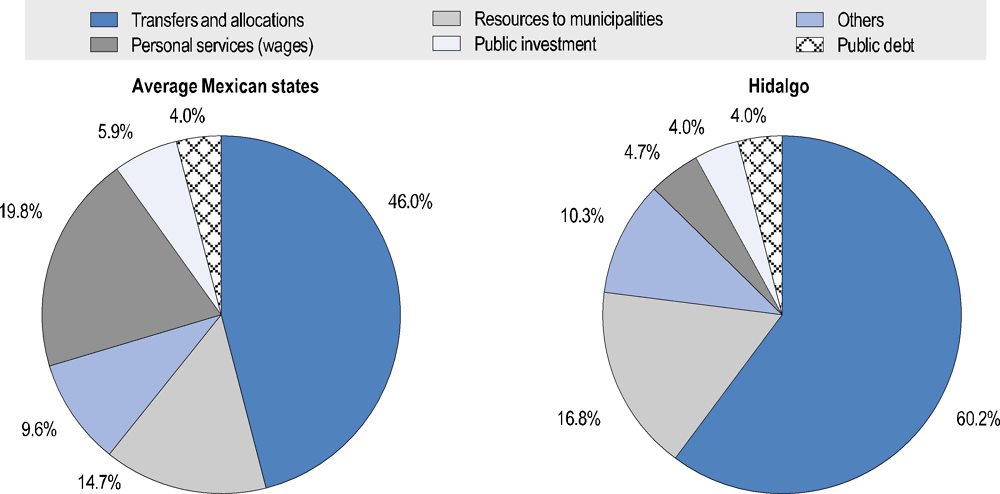

Between 2012 and 2016, the allocation of the expenditure in Hidalgo included (Figure 4.13):

Transfers and allocations (61%), which refer to transfers to sectorial programmes, mainly education (68%) and health (17%). This share of transfers is higher in Hidalgo than at the country average (46%).

Resources transferred to municipalities (17%) represent transfers by law that the state channels to local governments.

Functional expenses: personal services or wages (5%), public debt (3%) and other various expenses, such operational services and supplies (10%).

Public investments account for the remaining 4% of the budget, which results below the average of Mexican states (5%).

Figure 4.13. Distribution of expenses by type, average, 2012 to 2016

Source: INEGI (2016[6]), INEGI Databases, http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/microdatos (accessed 15 June 2018).

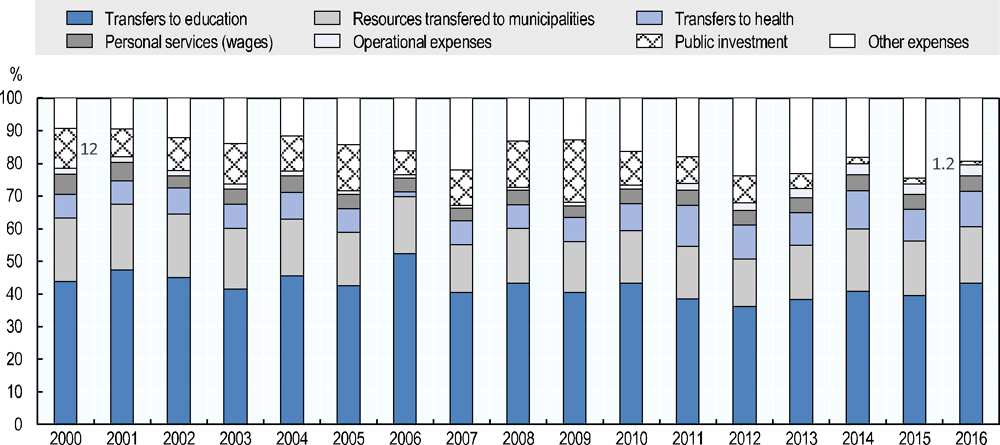

The distribution of public spending has changed significantly during the last years. Since 2000 to 2016, the share of the spending on transfers and assignments, especially to health, has increased (from 58% to 64%), contrary to the share of public investment which has substantially decreased from 12% in 2000 to 1% in 2016 (Figure 4.14). Hidalgo’s drop in public investment is larger than at the country average (from 7% in 2000 to 4% in 2016), mainly explained by a reduction in the investment in public works and in productive projects. A lower public investment is not only detrimental to economic growth in the long term but also to well-being at the local level.

Given its earmarked nature, the spending on transfers and assignments in Hidalgo mainly focuses on education. In 2016, education (educational institutions and programmes) represented the largest single expenditure from transfers and assignments in the state (43% of the total expenses), doubling the resources allocated to education as compared to the average in the Mexican states (20% of total expenses). The spending on health (10%) and infrastructure (3%) were the 2nd and 3rd biggest transfer. Resources allocated to tourism and agriculture did not represent a significant proportion of total expenses (0.04% and 0.05% respectively), and were lower than at the national average (0.6% and 0.1% respectively).

Figure 4.14. Expenditure in Hidalgo, percentage of total expenses

Source: INEGI (2016[6]), INEGI Databases, http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/microdatos (accessed 15 June 2018).

Hidalgo is one of the states with the lowest per capita expenditure allocated to personal services (MXN 656 compared with a country average of MXN 2 958 in 2015), despite its high proportion of public servants. Hidalgo ranks as the 9th state with the greatest number of public servants in the country (74 202 in 2015). Personal services refer to wages and payroll obligations such as social security and compensations. Low retribution or uncompleted wage schemes for public officers lead to high rotation and low incentives as well as making them prone to participate in corrupt practices. The relatively low level of personal services spending would also indicate that not all public servants are receiving full welfare payments. As mentioned before, the State of Hidalgo has high levels of labour informality, in which the public sector has an important role. This again stresses the need for Hidalgo to address labour informality in public administration.

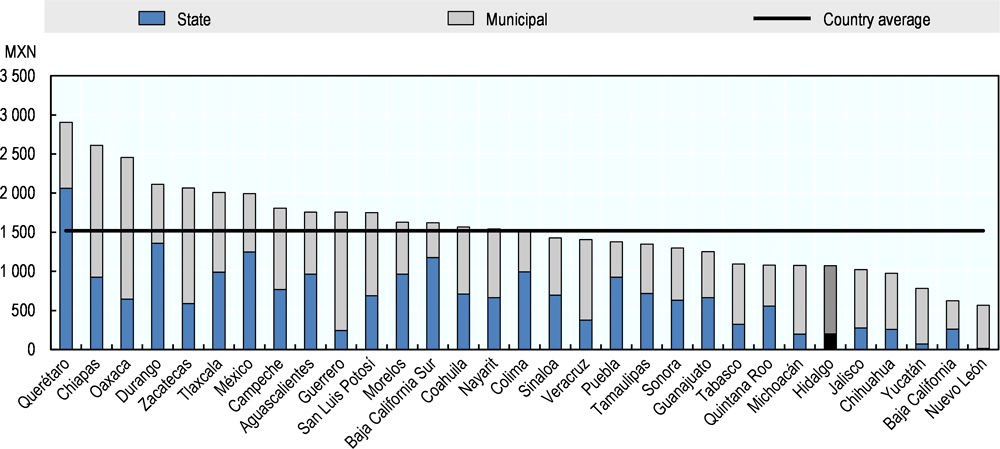

Hidalgo is the state with the sixth lowest level of public investment per capita in Mexico (Figure 4.15). Since 2012, public investment in the state (4% of total revenues) has been below the national average (5%). In 2016, public investment in Hidalgo was mainly allocated to physical infrastructure, where roads and highways represented over 38% of the total investment. It is a positive sign of the effort the state is conducting to connect and build the basic enabling factors for economic development in the territory. Investments in urbanisation (15%) are particularly larger than the national average (11%), which underlines the rapid urbanisation process the state is carrying out. Nevertheless, there is no public investment allocated to specific sectorial projects, in contrast with the country average (10%). Most Mexican states use public investment to develop sectorial projects on agricultural or tourism development.

Figure 4.15. Public investment per capita, 2016

Source: INEGI (2016[6]), INEGI Databases, http://www3.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/microdatos (accessed 15 June 2018).

At the municipal level, public investment represents the most important share but is mainly allocated to urban development and security. Between 2012 and 2016, the spending of Hidalgo’s municipalities was allocated to personal services (32%), public investment (26%) and operational expenses (13%). The main public investments were land division and urbanisation (24% of total investment), non-residential construction (8%) and provision of infrastructure for water, oil, gas, electricity and telecommunications (7%).

Concerning the sectorial investment, municipalities allocated a smaller share to productive projects (1.1%) than the country average (2%). The resources for productive projects in Hidalgo’s municipalities are mainly allocated to public security (96% in 2016), far above the share of the country average (17%), which allocated greater resources to agriculture and forestry (10%). The State of Hidalgo should hence encourage diversification of sectorial investment (i.e. environment) and better link investment with the strategic sectors at the local level to increase well-being and contribute to economic objectives. For this, monitoring mechanisms (e.g. performance indicators) to tighten budget allocation with policy outcomes at the local level could be instrumental (see next section this chapter). Hidalgo should also seek ways to increase the quality and level of public investment by promoting projects that attain critical mass and public-private partnerships as well as evaluating the cost-benefit of new funding.

Despite the low property and land use tax collection, the above figures underline that the state and local governments have invested important amounts of resources on urbanisation. This is welcome since the Hidalgo’s rapid urban growth creates high pressure on the provision of public services (see Chapter 3). However, given the low property tax collection and the outdated cadastres in Hidalgo, the fiscal pressure to sustain urbanisation creates a negative effect on the state’s public finances by reducing the fiscal resources to invest in other projects. This phenomenon stresses again the need for the state to align public needs and fiscal revenues by making a greater effort to improve property tax collection.

To achieve efficiency of public spending, Hidalgo should consider increasing the capacity for municipal governments to adjust expenses and improve co‑ordination among different levels of government. Currently, there are no mechanisms to incentivise joint spending among municipalities and to promote multi-year budget. At the local level, some spending decisions are driven by political interest with an aim of short-term results rather than meet the real needs of inhabitants and long-term outcomes (Valenzuela-Reynaga and Hinojosa-Cruz, 2017[15]).

In summary, this section underlined the following:

Hidalgo has one of the lowest levels of own revenues in the country, which in turn makes it highly dependent on federal transfers. Within own revenues, property taxes are especially low in the state.

The transfers are mainly earmarked, which provides little scope for decision and in some cases (i.e. reassigned resources) difficult investment planning. Non‑earmarked transfers are volatile, lack clarity on the allocation criteria and present characteristics of discretionary decision making.

Overall, transfers have aimed to incentivise tax collection and decrease inequalities among municipalities. Nevertheless, incentives are still low or not well perceived by local governments and the effective distribution from both types of transfers falls short on lifting the poorest municipalities above the richest ones.

Debt in Hidalgo has decreased and is currently low for Mexican levels. A cost-benefit analysis of new funding can be instrumental in increasing quality and level of investment.

Public investment is one of the lowest in the country. It is mainly allocated to security over other sectors that could offer economic opportunities for the state.

Spending on urban development is welcome. However, there is a need to match this spending with fiscal sources that stem from this activity (property taxes).

Improving governance in Hidalgo

Hidalgo’s geographic location and its connectivity with key markets, international ports, logistic centres and industrial areas offer untapped opportunities for growth in the state. However, the development of the state also requires addressing several challenges such as the strong south-north divide, the high levels of poverty and informality and the limited capacities at the local level as well as weak design and use of co‑ordination mechanisms across levels of government.

These challenges can be attributed, to some degree, to the endogenous characteristics of a small state, within the Mexican decentralised system, with three main features that stand out: i) limited scope of goals and activities; ii) predominance of strong informal relationships and procedures; and iii) limited steering or control (Box 4.6).

In particular, the deficient connectivity with and among the northern municipalities makes co‑ordination difficult in Hidalgo (see Chapter 1 and 3). The physical barriers to reach municipal governments and create fluent interaction among them jeopardises the realisation of economic potentials. In some cases, it can take more than half a day to travel from Pachuca, where the main governmental institutions are concentrated, to northern municipalities. In addition, Internet access is still incipient across the territory with some municipalities even lacking a reliable Internet connection, which in turn creates uneven communications among municipal governments far from and close to the capital.

In this scenario, the government administration of Hidalgo has made a great effort to modernise and improve the quality of public administration, the efficiency of public services and create a sound business environment to spur on new and local firms. It has also developed a co‑ordinated territorial agenda by encouraging municipalities to follow a private-led approach, focusing on business attention (Chapter 3).

This effort is materialised in the recent State Development Plan 2016-22. The current administration of Hidalgo elaborated a State Development Plan upon entering into office, as required by Mexican legislation. To do so, the state created the 2016 Law of Planning and Foresight, which is the legal framework for planning in the state, and upgraded the status of the former Secretary of Planning, Urban and Rural Development into a planning agency directly under the governor.

Box 4.6. Characteristics of small-state public administrations

Early research into the characteristics of small state governments highlighted five interrelated characteristics that are common to some degree across such states. While developed after studying sovereign nations, some or all of these characteristics can be relevant to administrations in federal countries where individual provinces or states have significant autonomy and decision-making power over the territory’s administration as well as policy design and implementation.

1. Limited scope of goals and activities. Small state administrations have to fulfil certain public prerogatives, such as maintaining health and education systems, regardless of the size of the country. Small states, therefore, need to prioritise and limit the number of goals and activities they pursue, the scope of action and the means of delivery (e.g. production versus the purchase of certain public goods).

2. Multifunctionalism of civil servants and organisations. Public officials in small administrations tend to have many, diverse responsibilities compared to their peers in larger administrations, who have more opportunities to specialise in a particular field. This is also seen in state bodies; for reasons of scale and resource sharing, there is a greater tendency to merge units (e.g. ministries, agencies, etc.) than to establish or maintain separate entities.

3. Informality of structures and procedures. Formal co-ordination mechanisms are more limited in small states and there is a tendency for structures to adapt to individuals rather than individuals to fit in formal organisational frameworks. While personal relationships are important in any system, senior civil servants in small states are more likely to use informal means of communication to consult and inform one another. Civil servants depend on these relationships – which can combine the professional and personal – in order to properly execute their responsibilities. These relationships can also serve as a bridge between executives and lower levels of organisations.

4. Constraints on steering and control. Independent scrutiny and reporting mechanisms tend to be less frequent in small states than in large ones due to limited resources, lack of specialisation and political partisanship. The political-administrative interface is usually less clearly defined in small states, with greater mobility between the administrative and political spheres. Senior civil servants, therefore, can have more autonomy in smaller states due to less formal oversight.

5. “Personalism” of roles and functions. The multifunctionalism, informality and limited control in small states allow a limited number of individuals to exercise a fair amount of influence based on their competencies, networks and personal qualities. While this can support agility and problem solving, it also leaves room for ad hoc decision making and subjective judgement.

These characteristics are not “good” or “bad” in and of themselves, but their interaction influences the governance contexts. For example, aspects of personalism that might be perceived as “leadership” in a system with institutional checks and balances can take on a less benevolent aspect in the absence of counter-balancing forces.

Sources: OECD (2016[41]), OECD Territorial Reviews: Córdoba, Argentina, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264262201-en; OECD (2011[16]), Estonia: Towards a Single Government Approach, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264104860-en; Sarapuu, K. (2010[17]), “Comparative analysis of state administrations: The size of state as an independent variable”, Halduskultuur – Administrative Culture, Vol. 11(1), pp. 30-43.

Hidalgo’s development plan is comprehensive but has room for improvement

The state plan is composed of 5 strategic pillars with 29 strategic objectives (Table 4.2). It has three transversal pillars, which are: i) gender mainstreaming; ii) development and protection of children and adolescents; and iii) incorporation of sciences, technology and innovation. The transversal pillars compose the strategic pillars, meaning that women’s equality, children’s protection and support for innovation are necessary for the development of these pillars and as such have to be mainstreamed into their specific objectives.

The plan’s elaboration started from a comprehensive diagnostic of economic, environmental and social conditions in the State of Hidalgo, across the five pillars. The data was provided by different state secretaries and from external sources such as the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) and the United Nations. The diagnostic aimed to be consensual, with an element of civic participation through an online platform (#YoPropongoHgo) and the organisation of five regional fora for consultation. The plan is thus context-specific and has broad input from within the government as well as sectors of civil society.

The plan is aligned with the National Development Plan (NDP) The national plan has five objectives (peace, social inclusion, quality education, prosperity and global responsibility) and three transversal strategies, namely gender mainstreaming, modern government close to people’s needs and democratisation of productivity. The State of Hidalgo maintained this structure of five main pillars and three transversal ones, with some of the objectives being similar to the national ones. This shows that the state is committed to the goals set for the whole country, and in a federal state this harmonisation is necessary.

Table 4.2. The National Development Plan of the State of Hidalgo

|

Pillars of the State Development Plan |

Strategic objectives |

|---|---|

|

A modern government |

1.Zero corruption 2. Increase citizens participation 3. Promote digital government 4. Improve regulation 5. Improve institutional capacity of municipalities 6. Strengthen fiscal capacity 7. Efficient fiscal management |

|

Economic dynamism |

1. Inclusive economic growth 2. Innovative economic environment 3. Co‑ordination of productive sectors 4. Development leveraged on tourism 5. Modern and productive agriculture |

|

Inclusiveness |

1. Social and integral development 2. Quality of education 3. Quality of health 4. Quality of sport culture 5. Art and culture |

|

Justice and security |

1. Improve governance 2. Human rights 3. Comprehensive security 4. Justice with human approach 5. Social reintegration 6. Civil protection |

|

Sustainable development |

1. Equity of services and sustainable infrastructure 2. Culture and environmental training 3. Comprehensive and sustainable territorial planning 4. Sustainable and efficient mobility 5. Preservation of the natural heritage 6. Planning for a sustainable territorial development |

Source: Government of Hidalgo (2016[25]), State Development Plan 2016-22

The plan is also aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which are a collection of 17 global goals set by the United Nations Development Programme. The state shows commitment with the international agenda of social inclusion, poverty reduction, gender equality, environmental sustainability and just and peaceful societies. The SDGs compose the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which is reflected in Hidalgo’s plan as 2030 is the proposed timeline for the second evaluation of objectives. Table 4.3 shows the alignment of some provisions of the state plan with the SDGs and the PND.

Table 4.3. Alignment of objectives (selected)

|

2030 Agenda |

National Development Plan 2012-18 |

State Development Plan 2016-22 |

|---|---|---|

|

Goal 16: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels |

Transversal approach (Mexico with global responsibility) Strategy II. Close and Modern Government 1.1.1 Contribute to the development of democracy Strategy 4.7.2 Implement a comprehensive regulatory reform |

Axis 1. Honest, Close and Modern Government 1.1 Zero tolerance to corruption 1.2 Boosting citizen’s participation 1.3 Digital government 1.4 Regulatory reform 1.5 Institutional development of municipalities 1.6 Strengthened treasury 1.7 Effective administration of resources |

|

Goal 8: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all Goal 1: End poverty in all its forms everywhere Goal 9: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialisation and foster innovation |

Transversal strategy - Democratise productivity Objective 3.5 Make sciences, technology and innovation pillars for economic and social sustainable progress Prosperous Mexico, objectives: 4.2 Democratise access to financing of projects with growth potential 4.3 Promote quality jobs 4.7 Guarantee clear rules that encourage the development of a competitive domestic market 4.8 Develop the strategic sectors of the country 4.9 Count on transport infrastructure that is reflected in lower costs for economic activity |

Axis 2. Prosperous and Dynamic Hidalgo 2.1 Inclusive economic progress 2.2 Dynamic and innovative economic environment 2.3 Articulation and consolidation of the productive sectors 2.4 Tourism, development lever 2.5 Modern and productive countryside |

Source: Government of Hidalgo (2016[25]), State Development Plan 2016-22.

The State Development Plan of Hidalgo has two timeframes: 2022, as the first year of the subsequent administration’s term, and 2030, as proposed by this international agenda. The 2030 timeline suggests a long-term vision which is not widespread in the practice of state development plans in Mexico, due to their very character as planning instruments which do not outlast an administration, since the subsequent administration is obliged to elaborate its own plan. For one, this vision is welcomed, as many objectives set in the plan require long-term changes to be achieved. Yet at the same time fulfilling this long-term vision can prove challenging, as local governments in Mexico tend to work to the election timetable. That is to say, the State of Hidalgo will need legal instruments that can formalise this commitment to the 2030 Agenda and guarantee that the objectives set in the plan will be pursued until then, as well as evaluated against that timeframe. The Secretary of Planning, Urban and Rural Development could envision such role if it has technical staff that outlasts election cycles.