This chapter maps and assesses the operating models and IT infrastructure that support the provision of employment and social services in Lithuania, and makes recommendations for improvement in these areas. The chapter explores four key elements of the delivery of employment and social services: promotion of services and pro‑active outreach to target groups, identification of individual needs and action plans, case management practices, and IT infrastructure and processes to support service provision. The Lithuanian public employment service and the providers of social services (within municipalities) have the prerequisites to reach out to target groups pro‑actively, consider individual needs in service provision and co‑ordinate support, but the current implementation of these approaches falls short of their full potential. Furthermore, the IT infrastructure is not sufficiently supporting service provision, particularly in terms of data exchange between registers, user-friendliness and functionality of user interfaces, and data analytics tools for monitoring purposes.

Personalised Public Services for People in Vulnerable Situations in Lithuania

3. Operating models and IT infrastructure to support the provision of employment and social services in Lithuania

Abstract

3.1. Introduction

This chapter explores the current operating models and IT infrastructure of the Lithuanian Public Employment Service (PES) and social services centres present at the municipality level, paying particular attention to three vulnerable groups: people with disabilities, ex-prisoners and youth leaving care. The chapter provides an assessment of the following four key dimensions of current employment and social service delivery in Lithuania:

Promotion of services and pro‑active outreach to target groups,

Identifying individual needs and proposing action plans,

Case management practices (including the co‑operation of external organisations and specialists),

IT infrastructure and processes that support service provision.

Following this assessment, each section puts forward a series of recommendations designed to enhance the work of Lithuanian employment and social services in each area. This chapter makes use of various questionnaires (completed by the Lithuanian PES, the Ministry of Social Security and Labour and municipalities) and consultations with a wider range of stakeholders involved in providing employment and social services (see Chapter 1 for an overview).

3.2. Promoting services and outreach to target groups

To ensure that services reach the people that need them, providers need to engage in both the promotion of services and pro‑active outreach to target groups. This section seeks to provide an overview of the ways in which providers of employment and social services in Lithuania raise awareness of available supports and engage in pro‑active outreach efforts with individuals in target groups who are not yet clients, while also putting forward a series of recommendations for Lithuania to enhance their work in these areas.

3.2.1. Raising awareness about available support

In the case of the Lithuanian PES, a number of methods are employed to promote the services on offer. These are typically in the form of traditional media (such as TV, radio, newspapers), social media, public events, and engaging with both employers and representative organisations of target groups. While this represents a significant promotion effort, these efforts seek only to promote services in general, usually with no tailored promotion activities in place to cater towards specific target or vulnerable groups. Considering that the groups of ex-prisoners and care leavers are relatively small groups, with very specific needs, reaching out to them individually rather than via general promotion can be more effective and efficient.

In the case of social services, the general promotion of services consists of, above all, discussions with the representative organisations of the target groups (organisations representing people with disabilities, youth organisations). Direct dissemination of information about the services via visits to homes and institutions concerns above all other target groups than those of interest of the current report (elderly, nurses of people with severe disabilities and no work capacity).

More direct promotion of services available for people with disabilities, ex-prisoners and youths is occasionally done by non-governmental organisations (NGOs), such as by the umbrella organisations of associations for people with disabilities or NGOs to support social inclusion of ex-prisoners, often without public sector funding. In addition, the PES, municipalities and the Ministry of Social Security and Labour promote and discuss available services in meetings with the representative organisations of different target groups. This serves as a more direct means of channelling information to the target groups, although potentially reaching only a limited number of people. All these organisations provide some information about the available services also on their websites, although to a different degree of detail.

In raising public awareness of the needs of target groups, fighting against stigmatisation and for equal treatment, a strong role is also played by NGOs, such as the representative organisations of people with disabilities. The Ministry of Justice and its Prison Department aim to tackle the promotion of social inclusion of ex-prisoners, although changing society’s perception of ex-prisoners has been difficult. The PES monitors that individuals are not discriminated against more generally, such as monitoring the provision of services to different cohorts, the behaviour of employers the PES co‑operates with and the activities of external service providers. However, this monitoring does not generally lead to actions, with no intervention taking place in cases where discrimination is identified. Further awareness initiatives are conducted for people with disabilities, whereby the PES organises public awareness campaigns to highlight the needs of this group.

3.2.2. Pro‑active outreach

Both the PES and municipal social services engage in some ways to get in contact with potential clients, although these activities are not implemented necessarily systematically and across all groups in need of support. Formal referrals from other service providers, contacts from informal co‑operation with other organisations and the use of contacts available from the provision of benefits are the primary avenues through which the PES can get in contact with those in need of support for social and labour market integration. These channels could be employed by the PES in general to all potential clients, including specific target groups, although the use of these channels is not systematic and does not happen to the same degree across all local offices and target groups. In addition, this approach will not enable the PES to get into contact with individuals not in receipt of benefits or participating in services provided by other organisations. At municipal level, social services centres also engage in these same means of contacting the people in need of their supports and services. However, 26% of social services centres in municipalities also visit organisations, such as residential care homes for young persons, prisons or care centres for people with disabilities, to get in contact with those in need of their services. Also, NGOs providing social services (with public funding, as well as without) contact these institutions themselves to identify people in need of their services. This allows for at least some level of outreach and contact with those in key target groups, that may not be reached through other channels.

Most commonly the clients contact the PES and municipal social services on their own initiative. This initiative is not necessarily tied to receiving employment and social services, but instead is often linked to various benefits available through these organisations, such as unemployment benefits and social assistance. Furthermore, registering with the Lithuanian PES provides jobseekers with health insurance coverage. This is also believed to be the reason why the share of jobseekers registered with the PES is higher than in any other EU country (86% compared to 43% in the EU in 2020 according to Labour Force Survey data) and could be also the reason why the PES is reluctant to engage in significant additional efforts to reach out to potential clients.

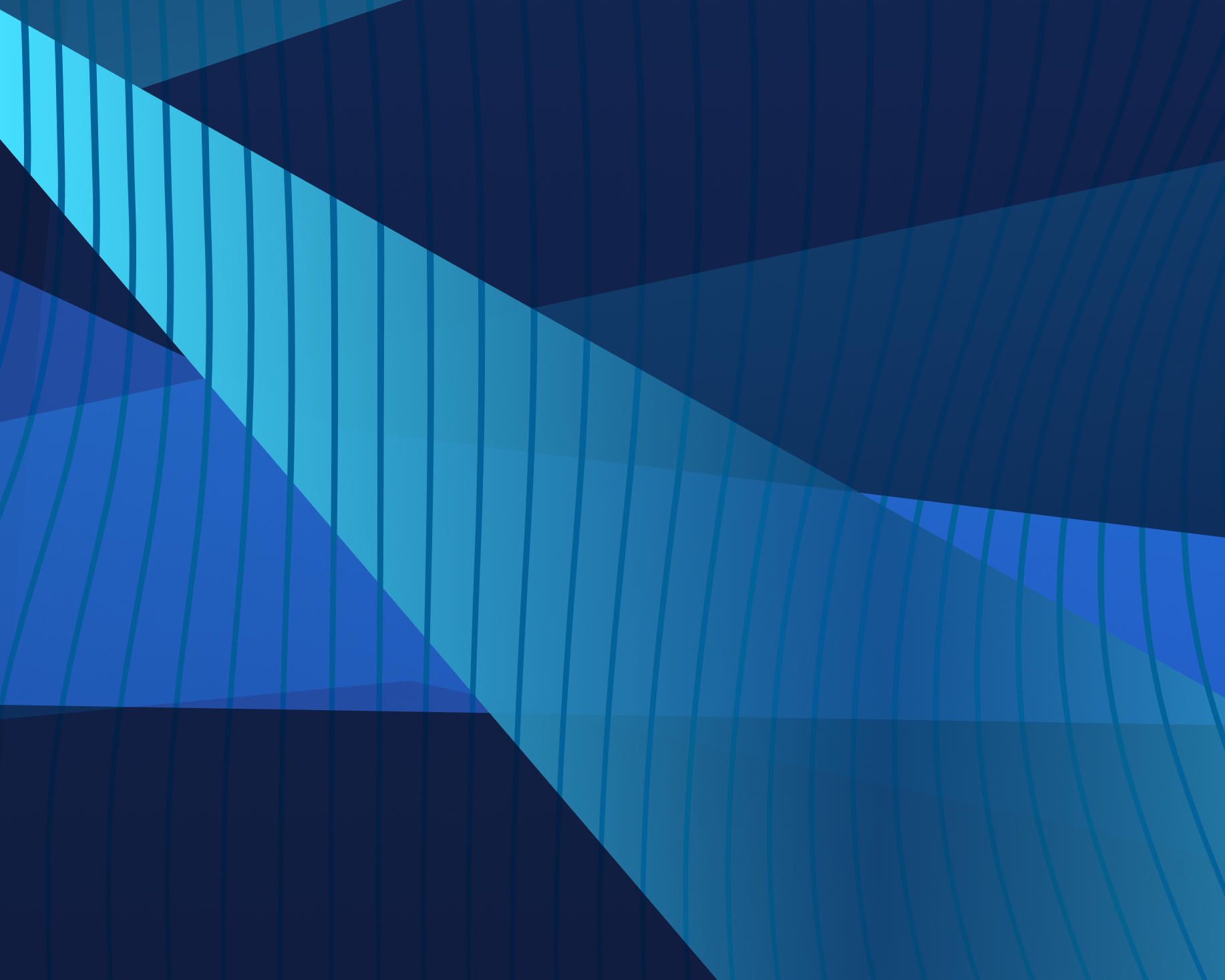

In gaining information beyond what is available in-house in order to get in contact with potential clients, both the PES and Municipal social services use some information provided or generated by other organisations (Figure 3.1). For the PES, the exchange of contact information from other organisations is not an automatic process but is still supported by built-in queries in the IT system. Such a system allows for a regular and efficient generation of requests for data, rather than occurring in an ad hoc fashion. The vast majority (68%) of municipal social services centres conducts these exchanges of information and client referrals without support of any digital system or process. Instead, these centres rely solely on in person meetings, phone calls and mail or paper forms of sharing in order to facilitate this information exchange. Just over one‑fifth (21%) obtain this data by digital means, either via a dedicated information system (9%) or electronically without an IT system (e.g. via emails or files uploaded on an online platform). The large reliance on non-digital and informal means of data exchange increases the likelihood of information gaps, with potential clients missing out. A particular example for this concerns information exchange regarding social services for ex-prisoners. The recently introduced social workers in prisons discuss and advise the prisoners about to be released on their pathways to social and labour market integration, and the municipalities where the prisoners are planning to return are informed by these social workers, although not systematically and not via a dedicated digital platform. In practice, those informed municipalities do not try to make contact with the ex-prisoners but rely solely on the initiative of ex-prisoners themselves.

Figure 3.1. Ways in which service providers receive information from other organisations in order to identify whom to contact in their target groups

Note: This figure is based on responses received to this question from 55 municipalities and the PES Head Office. Non-responses are not included in the figure. The PES icon refers to the approach used by the PES. The approaches for receiving information are ranked by how easy it is to access information from other organisations (the approach where accessing information is the most facilitated is on the top).

Source: OECD questionnaires to municipalities and the Lithuanian PES, see Chapter 1.

For both the PES and municipal social services centres, the co‑operation with other organisations to get in contact with the target groups is most commonly with (other) Municipal Governments, NGOs and other private‑sector providers, and public institutions, such as prisons, institutional care providers for people with disabilities and foster care providers. However, social services centres tend to cast a comparatively wider net, as in limited cases they co‑operate also with the police, the probation service, hospitals and other health services. Some co‑operation to reach the target groups exists also between the PES and municipalities (54% of social service centres co‑operate with the PES for this purpose).

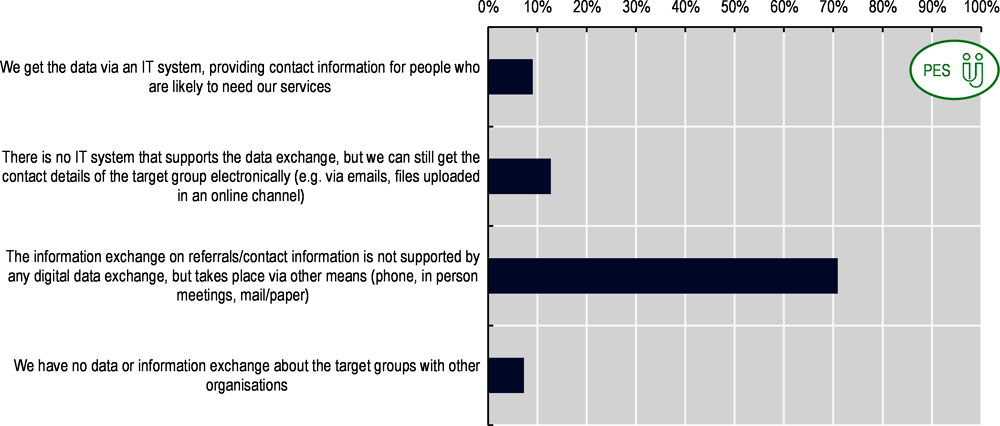

Pro‑active outreach to people receiving institutional care (foster care, care homes, prisons) is missing in the PES, as well as in the majority of municipalities (Figure 3.2). Providing employment services for people receiving institutional care largely relies on these individuals contacting the PES after they have left the institution. On the side of social services centres, the approach to those in receipt of institutional care can vary across target groups, as well as case by case. In total 47% of social services centres contact some groups of people still in the institution, although most of them will only discuss the individual’s needs but will not start providing support before the client has exited the institution. The majority of municipalities are also contacted sometimes by people still receiving institutional care to ask for support, but only some of municipalities (25% of all Municipalities) are able to start providing some of their social services before the person has exited the institution. Of situations where contact is made by the social services centre, the majority of service provision only starts when the person has left the institution. Furthermore, in case the first contact with the client takes place only after exiting the institution, it is more likely due to the initiative of the person, rather than the initiative of the municipality. For both the PES and social service centres, the lack of or uneven provision of services to individuals while they are still in institutional care mitigates the potential for individuals to benefit from early intervention and to better facilitate their social and labour market integration. In addition to the varied approach, there is a large reliance on the side of both the PES and social services centres on these individuals making the contact themselves, with limited efforts placed on effective outreach attempts to this group.

Figure 3.2. Patterns of contact with people receiving institutional care

Note: This figure is based on responses received to this question from 57 municipalities and the PES head office. A given social services centre often engages in multiple approaches. The PES icon refers to the approach used by the PES. The categories of getting in contact with the people in need is ranked by their level of pro‑activeness and swiftness (the most pro‑active approach on the left, the least proactive on the right).

Source: OECD questionnaires to municipalities and the Lithuanian PES.

3.2.3. Challenges in reaching out to people in need

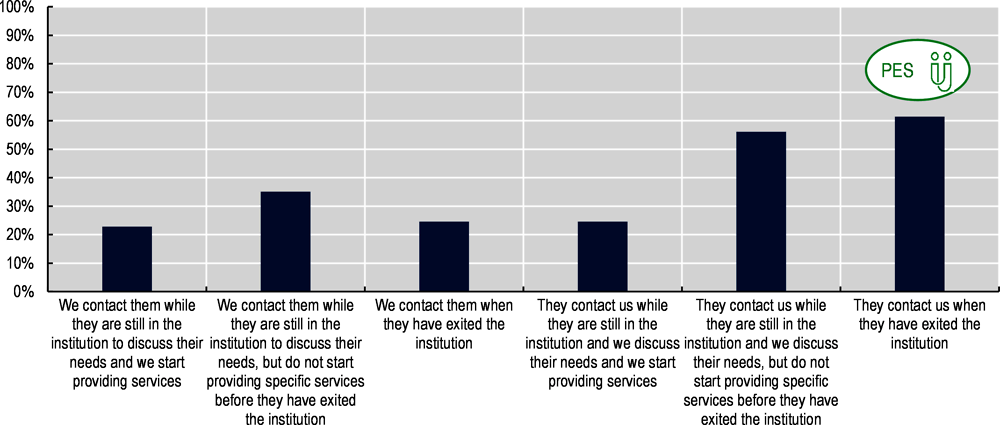

The primary challenge identified by the PES in reaching out to the target groups is a lack of incentives for individuals to make contact (Figure 3.3). This means that the benefits and services offered by the PES are assumed not to be enough to attract the potential clients and engage them in job search (the small fraction of unemployed that are not registered with the PES, and potentially a larger number of inactive people). However, this could also suggest potential shortcomings in the outreach and promotion activities of the PES, in order to increase awareness of and interest in the services on offer. For social services centres, this issue is less prevalent, faced by less than one‑fifth (18%) of municipalities. Instead, the three greatest challenges identified by social services centres are deemed to be insufficient background information on the people in the municipality in order to identify those in need of support, a lack of contact information for individuals in target groups who are not yet clients and a shortage of capacity (both staff and budget) to contact target groups.

Figure 3.3. Greatest challenges faced in getting in contact with the target group

Note: This figure is based on responses received to this question from 57 municipalities and the PES head office. The PES icon refers to the situation for the PES.

Source: OECD questionnaires to municipalities and the Lithuanian PES.

3.3. Recommendations on the promotion of services and pro‑active outreach to target groups

Overall, promotion activities and outreach efforts to target groups fall short of adequate in both Lithuanian employment and social services. This section outlines key areas for action to improve these activities, including enhanced targeted promotion that is needed along with pro‑active outreach and early intervention for the key target groups, in order to ensure that these services reach those who need them most.

3.3.1. Both employment and social services providers should improve promotion activities, with particularly attention paid to target groups

To raise awareness of services on offer (both employment and social services), both the PES and providers of social services in municipalities should engage in more active promotional activities. This includes dedicated promotional activities aimed specifically at target groups and continued engagement with representative organisations. Increased awareness would help overcome the challenge identified by the PES relating to a perceived lack of incentives for individuals to make contact with the PES to receive support (including unemployed individuals not registered with the PES and inactive individuals).

While general advertising efforts are useful, more targeted promotion is useful in the case of vulnerable groups. For example, Estonia opted to not use traditional advertising methods to promote the Work Ability Reform,1 but instead focussed on informing affected groups (OECD, 2021[1]). Information was disseminated by the Estonian PES and the responsible Ministry (Ministry of Social Affairs) in co‑ordination with the Social Insurance Board to raise awareness of the (new) services available for people with reduced work ability and the organisations to contact. Furthermore, representative groups of people with reduced work ability were directly involved in the design of the reform, creating a greater awareness of available supports and services among these groups through this process. As a part of its social security reform, Finland is implementing the Future Social and Health Centre programme to strengthen the multidisciplinary approaches and interoperability of services, as well as improve equal access and continuity of services, increase proactivity and ensure quality and effectiveness (Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos, 2022[2]). Also the Finnish reform is supported by intense systematic and co‑ordinated communication, on national level via the Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (including organising networking days), and on regional level by regional co‑ordinators who act as supporters of the implementation of the reform, information brokers and networks with all stakeholders. Furthermore, involving service recipients in public service design is encouraged in the Finnish constitution (Munday, 2007[3]). In introducing new integrated services and approaches, Lithuania needs to involve the representatives of the affected user groups systematically in developing, designing and implementing the changes, to ensure the new approaches meet the needs of the groups, as well as will be taken up by them.

To ensure information reaches the target groups, it is key to use face‑to-face channels in addition to other formats of communication. For example, the Estonian PES organises mobile counselling (called MOBI) in remote areas, in co‑operation with the relevant stakeholders (including municipalities, social workers, schools, representative groups, NGOs, etc.). Such mobile counselling is targeted at individuals furthest from the labour market and is conducted roughly twice per year in each county, in co‑operation with different municipalities. The main goal of the mobile counselling is to directly disseminate information on services and supports available to these vulnerable groups from different service providers. There is scope for Lithuania to engage in similar activities, particularly through collaboration between both employment and social services, to make contact with at risk and vulnerable groups in municipalities through a form of mobile counselling and outreach. This approach will help create a shared responsibility for service providers to also make contact, a role which typically falls on the client at present and will improve awareness and provision to vulnerable groups who are unlikely to present for support themselves.

3.3.2. PES and social service providers should develop systematic and pro‑active outreach strategies for the target groups

Effective outreach strategies should be developed and followed by both the PES and social service providers. These strategies need to prioritise co‑operation and data exchange with relevant stakeholders, other service providers and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to assist in the mapping of target groups and identification of people in need of support. Such agreed guidelines for outreach can better establish consistency of approach across service providers and localities. Furthermore, given the comparatively small size of some target groups in Lithuania (in particular care leavers and ex-prisoners), individualised outreach could be more efficient and effective than promotional activities for these specific groups.

A key enabler of effective outreach is sufficient data exchange with relevant institutions and stakeholders, to enable the identification of individuals in target groups. An international example, relevant to the challenges faced by Lithuania, is that of Estonia’s Youth Guarantee Support System (YGSS). The YGSS was established in 2018, building on the EU-wide Youth Guarantee initiative and addressing the need for better data in Estonian municipalities to facilitate the identification of young people in need of support (Estonian Social Insurance Board, 2022[4]). This system pools data from nine separate registers, resulting in a comprehensive dataset containing the contact information and education level of young persons who are not employed, registered with the PES, in education or otherwise not available for the labour market (e.g. military service, maternity leave). Using this contact information, case workers contact the young people and offer case management to those who require support for their entry (or re‑entry) into education or the labour market. The YGSS tool has greatly assisted the mapping, identification, outreach and in turn case management of young people in Estonia, with its proven effectiveness showing its potential to be applied to other target groups – including in the case of Lithuania. Similarly, social and employment services in Lithuania should better utilise available data to engage in systematic and pro‑active outreach to target groups. This should be supported by a dedicated IT tool or system to support the identification, outreach and track engagement with potential clients.

In Bulgaria, “Youth Mediators” and “Youth Activators” are used to reach out to unemployed and inactive young people (OECD, 2021[5]). While “Youth Mediators” are hired by the municipalities and “Youth Activators” by the PES, central to both of these roles is fieldwork, identifying and making contact with young persons, particularly those far from the labour market. Some of the mediators hired have themselves experienced similar periods of inactivity and have a shared understanding of the clients’ situation. Co‑ordination between the mediators and activators is indispensable for effective outreach and subsequent service provision, and co‑operation with a wide range of other stakeholders to further facilitate these tasks is common (schools, labour offices, local social assistance offices, mayors of small settlements and NGOs). In addition to onsite visits, the youth workers use social media to raise awareness on job offers, services and events. While interinstitutional youth co‑ordinators do exist in some Lithuanian municipalities, with their work primarily focussing on advising on youth and child services, their roles could be bolstered by additional youth workers doing the fieldwork and pro‑actively reaching out to inactive youth.

3.3.3. Early intervention for key target groups could enhance outreach efforts

In the case of vulnerable groups (including the three target groups of this project), early intervention and engagement from the PES and social service providers could be greatly beneficial – guiding those in need towards the relevant services and ensuring vulnerable persons do not become further removed from society and the labour market. Lithuania recently placed social workers in prisons to engage and advise prisoners close to release. While this is a promising step, some hurdles remain. These dedicated social workers typically liaise with the municipality in which the prisoner is to be released – however, this exchange of information is not done systematically and is not supported by any dedicated digital platform. Furthermore, in practice once released, making contact is left to ex-prisoners. Therefore, early intervention activities have significant room for improvement, including in implementing an agreed protocol and system for relaying information between staff in prison and service providers in municipalities and employment and social service providers themselves reaching out to individuals once they have left the institution. Furthermore, there is a role for social workers and PES staff to engage in such early intervention beyond prisons to cover their other target groups, including in care institutions and in health services.

A relevant example is the collaboration between the Swedish PES, criminal services and municipalities. Here, PES staff engage with people in prisons and probation centres nearing the end of their sentences, with the aim of enhancing their societal and labour market integration once they have exited the criminal system (Arbetsförmedlingen, 2022[6]). Case management sees the production of an action plan jointly agreed between the case manager and client, education opportunities, coaching, work experience opportunities and support to increase the work ability of clients with disabilities. This co‑operation and early intervention, although currently unsupported by an IT system or associated data exchange, has yielded positive results, including 20% of clients being in employment within three months of completing their sentence or probation period. With the support of municipalities, an increasingly popular dedicated programme (called Krami) aims at a pathway to labour market integration via preparatory activities and guidance, internships, wage subsidies and follow-up support. Similar services to Sweden exist in Belgium (OECD, 2013[7]), Estonia (OECD, 2021[1]) and Norway (Fafo, 2017[8]) where people close to release from prison are supported by employment counsellors to facilitate their integration into labour market. While Lithuania is taking steps in the right direction in this area – namely regarding ex-prisoners and young people leaving care – there is room for further improvement. This improvement can come from expanding the target groups, ensuring follow-up after people leave different types of institutions, implementing agreed case management protocols and systems and ensuring co‑ordination and referrals area between social and other service providers (including employment services). There is potential also for this to be linked to the role of interinstitutional co‑ordinators already in place in some Lithuanian municipalities for youth, aiming to cover all municipalities and expanding target groups, particularly regarding those that more likely need support from several different organisations.

3.4. Identifying individual needs and proposing action plans

In delivering employment and social services, identifying the needs of clients is a crucial first step in service provision. This section will explore the ways in which individual needs are identified and taken into consideration in providing social and employment services in Lithuania. This includes exploring the use of guidelines surrounding service provision, the process to decide what supports are given to a given client and the development of individual action plans by employment and social service providers. Finally, this section outlines a number of recommendations on how providers of employment and social services in Lithuania can make improvements in this area, including through the formulation and implementation of guidelines for service provision and the use of individual action plans where they are currently lacking.

3.4.1. Guidelines for harmonised service provision

In guiding the way in which their staff support their clients, the Lithuanian PES has a set of internal guidelines that govern service provision. The PES takes measures to ensure that regulations and internal guidelines are followed in order to provide a sufficient level of services to clients. These measures include both internal and external training options for staff and monitoring practices to ensure regulations and guidelines are followed, with action taken as needed. In addition, the IT system of the PES incorporates controlling mechanisms that do not permit deviation from the prescribed regulations. These guidelines are applicable to all clients, with no particular guidelines in place to instruct the delivery of service to specific target or vulnerable groups.

At the municipality level, social services centres often do not have clear and formal guidelines. This creates a risk of differentiated (but not necessarily best fitting) approach to service provision, provides no means by which issues can be identified and can lead to varying service quality. Only 53% of municipalities identify that they have such internal guidelines. The remaining 47% of municipalities instead solely rely on what is prescribed in the legal regulations, foreseen in the Social Service plan or set out by the bodies such as the Ministry of Social Security and Labour. At least some of the NGOs co‑operating with municipalities to provide social services have adopted international guidelines to support their service provision, particularly concerning people with disabilities.

3.4.2. Identifying individual needs

In deciding what supports are to be provided to a specific client, Lithuanian PES employment counsellors discuss with the client their needs and then make the decision on support needs based upon all available information about the client (data in the IT system, information from interview, etc.). More specifically, the PES counsellors are supported by a digital tool (a jobseeker profiling tool using individualised statistical assessments) that predicts the probability of employment for each client, advising the counsellors about the potential needs of the client.

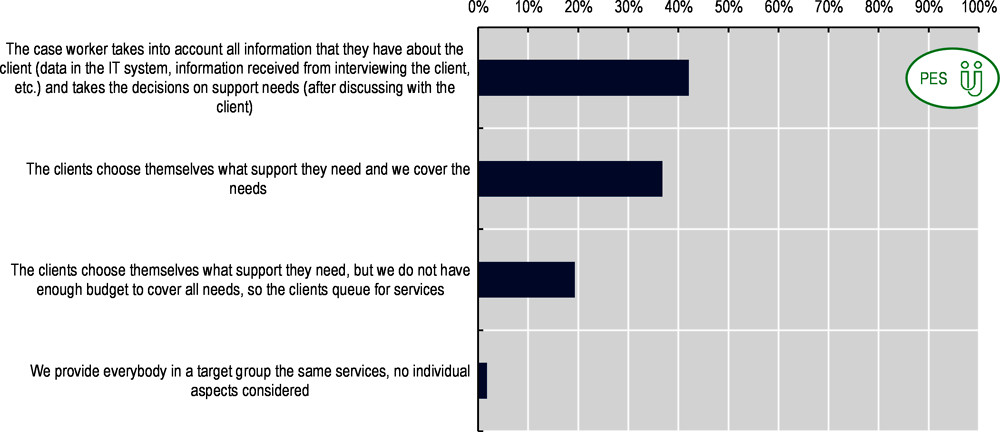

Within municipalities, social services are not necessarily provided according to the individual needs. Less than half (42%) of municipal social services centres take the same approach as the PES, with case managers making the decision on necessary supports based on available information and discussions with the client (Figure 3.4). Instead, over half (56%) of municipal social services centres let the client decide for themselves what support they require. Within this group, two‑thirds (or 37% of total municipal centres) cover the self-prescribed needs of the client. The remaining third (or 19% of total municipal centres) do not have sufficient financial resources to fully cover the needs of clients, requiring clients to join the waiting lists for their desired services. One municipality provides everybody in a given target group with the same services and supports, with no consideration given to individual needs.

Figure 3.4. Process to decide what support to provide to a specific person

Note: This figure is based on responses received to this question from 57 municipalities and the PES head office. The PES icon refers to the approach used by the PES. The categories of approaches are ranked according to how much the service provision takes into account the individual needs of the clients. The approaches to service provision are ranked by how much individual needs are considered in service provision (the approach where the individual needs are taken into account the most is on the top).

Source: OECD questionnaires to municipalities and the Lithuanian PES.

3.4.3. Individual action plans

Individual action plans (IAPs) are a widely used component of effective support for labour market and social integration. The creation of an IAP allows for the goal of integration to be defined and to establish the activities to be engaged in on the individual’s integration pathway (Tubb, 2012[9]). Their definition and use are based on the principle of “mutual obligations”, both on the part of the client and that of the case manager or employment counsellor. Therefore, the jointly signed agreement clearly defines the commitments of the client and the service provider and, if used correctly, allows for effective monitoring of the integration process.

In Lithuania, IAPs based entirely on the client’s individual needs are a central component of the case management process in PES offices and the majority (68%) of municipal social services centres. A number of municipalities (16%) also propose action plans, however these follow the standard for the person’s target group. The use of a standardised, rather than individual, action plan would not be a recommended approach, as it fails to account for an individual’s unique circumstances and needs. This is particularly relevant in case of clients from vulnerable groups, where well-targeted and individualised interventions are key feature of successful provision of services to these individuals (OECD, 2021[10]). The remaining 16% of municipalities that do not develop action plans or agreements with clients, only discuss next steps with the client orally – either in person or by phone call. Of these, only one‑third insert potential next steps into their IT system. This informal approach, without compulsory recording of the plan, makes it difficult for an individual’s progress and progression through services to be monitored and addressed. Also, social workers in the prisons do not develop IAPs with their clients, but simply record needs for services that could be later picked up by social workers in the municipality (but not necessarily will).

The successful and effective use of IAPs also requires regular review and renewal, something that is in place in Lithuanian employment services but lacks co‑ordination within municipal social services centres. Within the Lithuanian PES, action plans are reviewed at regular intervals although not very frequently; every four months for people up to 29 years of age, but only every 12 months for other age groups. Within municipalities, the approach for renewal of action plans is much less clearly defined. Less than one‑fifth (19%) of municipalities review action plans at regular intervals. Instead, three‑quarters of municipalities review action plans solely on an as-needed basis. The remaining 6% of municipalities also have no defined process for review and renewal, and thus reviewing action plans only rarely. The effective monitoring and review of individual action plans allows for the dynamic support of clients, that evolves in response in the changing needs or situation of the client and allows the service provider to continually check the jobseeker’s ongoing compliance with the services or measures the client is participating in (Tubb, 2012[9]). Without a clear and defined process for setting and reviewing IAPs, Lithuanian social services centres can yield neither of these benefits.

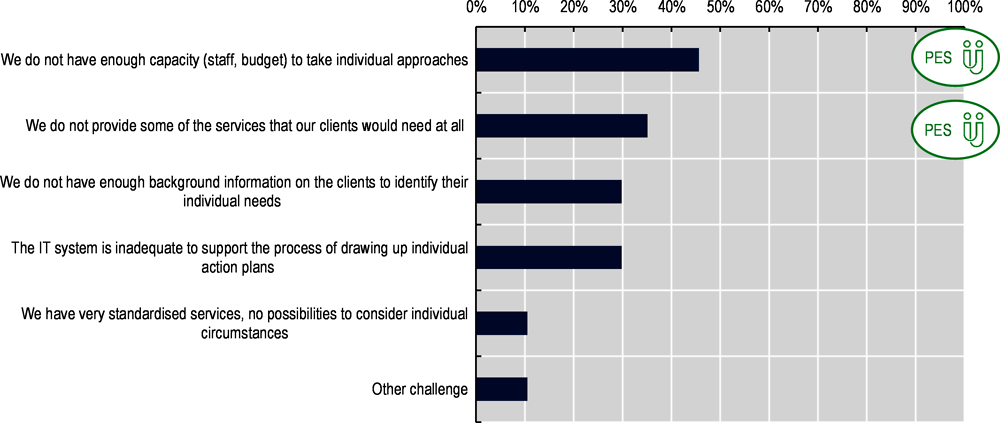

3.4.4. Challenges in providing services according to individual needs

In providing services according to the individual needs of the clients, the PES and municipalities face similar main challenges – too limited resources (staff and budget) and lack of appropriate services matching the individual needs (Figure 3.5). To some extent, the underlying reason for seemingly missing services can be the complexity of needs, requiring a combination of services from different providers. In addition, further challenges are identified by municipalities, with 30% of municipal social services centres experiencing both insufficient background information to identify the needs of client and inadequate IT systems that do not support the drawing up of action plans.

Figure 3.5. Greatest challenges faced in proposing pathways to social and labour market integration that consider the individual needs of clients

Note: This figure is based on responses received to this question from 57 municipalities and the PES head office. The PES icon refers to the situation for the PES.

Source: OECD questionnaires to municipalities and the Lithuanian PES.

3.5. Recommendations on the identification of individual needs and use of action plans

The provision of services according to individual needs and the use of action plans are central components of effective case management. To ensure consistent service delivery across municipalities and support that is tailored to the needs of the individual, Lithuanian social services should undertake a number of key actions. This includes developing and implementing guidelines for service provision that can ensure coherent provision of social services across municipalities, including the utilisation of jointly agreed individual action plans.

3.5.1. The work of social workers should be informed by guidelines for social service provision

While employment services in Lithuania are subject to guidelines for service provision, an uncoordinated approach exists in social service provision. Efforts should be made to establish and implement guidelines for social service provision across all of Lithuania. The updated Lithuanian Law on Social Services, enacted in July 2006, establishes – inter alia – the principles for the management, granting and provision of social services.2 Building upon this law and these principles, Lithuania should adopt guidelines for service provision in order to ensure standardised and co‑ordinated support to all clients, irrespective of the provider or municipality. Such guidelines should also cover contracted-out service providers, to ensure consistency of approach and quality across all providers.

Such service guidelines and strategies should outline the general principles of social services that apply to all clients, irrespective of age or background (e.g. counselling, jointly developed action plans, follow-up), and targeted (often more intensive) interventions for specific target or vulnerable groups. Furthermore, the guidelines should establish clear processes for social workers to follow in terms of referrals to and co‑operation with other organisations and service providers. Guidelines are key to ensure the quality and effectiveness of service provision. For example, extensive guidelines is one of the pillars of the Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model that is an evidence‑based approach to support people with serious mental illnesses and integrates mental health treatment and support, and employment support. IPS has been evaluated comprehensively and credibly across countries, the evaluation results strongly indicating significant positive effects on the labour market outcomes of the participants compared to other support schemes (IPS Employment Center, 2021[11]).

3.5.2. All clients of Lithuanian social services should benefit from the development and implementation of individual action plans

The development and implementation of IAPs should be a central component of the recommended guidelines for social service provision across Lithuania and in turn a crucial step in setting out a client’s integration pathway and the support measures they will receive, after the identification of their needs. The use of jointly agreed IAPs enhances transparency and strengthens the mutual obligations between the social worker and client. Action plans tailored to the individual client and their needs are crucially important but should also be guided by overall principles for action-planning to ensure action plans reach the required standards and expectations (Tubb, 2012[9]). The IAPs could be of even greater benefit to the clients if these would be developed and implemented in a co‑ordinated manner or even jointly between the different service providers in case a person needs different services. Québec’s (Canada) PRISMA programme involves individualised service plans involving social and healthcare services for people with disabilities and elderly, in addition to integrating other aspects of providing social and healthcare services (MacAdam, 2015[12]).

An example of quality assurance in the use of IAPs in public services is seen in Estonia’s PES. This assessment procedure aims to ensure action plans correspond to the needs of clients (OECD, 2021[1]; Radik, 2016[13]). A dedicated internal unit of the PES take a sample of IAPs twice annually, with each IAP rated (on a four‑point scale) against a set of criteria.3 The average score for the region and PES as a whole is one of the central performance indicators of the PES in the area of service quality. The assessment process also sees feedback on IAPs, which helps case workers improve their work in this area and has seen an improvement in quality of IAPs over time according to the scoring system. Systems to establish quality assurance procedures should also be implemented in the use of IAPs in Lithuania. This should include the timeframe by which each client should be issued an IAP and an agreed minimum frequency of review. Regular review of IAPs allows the changing individual needs and situation of the client and their experience of support measures to date to be taken into consideration and can assist in the identification and addressing of any issues that may arrive (including monitoring an individual’s participation with services provided).

3.6. Case management

Concerning case management, this section focuses on the aspects of expertise and co‑ordination of professionals involved in supporting clients of both employment and social services in Lithuania. Across OECD countries, the case management process is typically led by an employment counsellor in public employment services and a social worker in the case of social services, ideally co‑operating with each other in a formal or informal set-up to ensure holistic and seamlessly integrated service provision. In some countries, the provision of employment and social services for the most complex target groups is fully integrated into one‑stop-shops, with a wide spectrum of services and supports provided under one roof. Regardless of the set-up for co‑operation between employment and social services, the involvement of experts and specialists from outside organisations to assist the case management process and delivery of supports to clients is often necessary to the provision of holistic services. In assisting clients from vulnerable groups, such co‑operation with other service providers is particularly important (OECD, 2021[10]), with evidence suggesting that shortfalls in co‑ordination among different service providers is a leading obstacle to the provision of effective services (Eurofound, 2017[14]). Such holistic provision can be a difficult task, requiring enhanced attention and efforts by case managers and established patterns of co‑operation and data exchange with partner organisations. In mapping these elements of case management and co‑operation (including with employers), this section concludes with a series of recommendations to improve this central component of service provision in both Lithuanian employment and social services.

3.6.1. Professionals and organisations involved in case management

The Lithuanian PES aims to provide specialised case management to its clients. While the majority of clients receive support from an employment counsellor who is equipped with more general support tools, the more complex cases are referred to case managers with more specific expertise and working methods. The more specialised case management is used for example when a person with disabilities needs more advanced support to their reduced working capacity, or when a young person needs support beyond job search support to achieve labour market integration. Furthermore, support for the most complex cases is provided jointly by several case managers and specialists in-house.

The vast majority of municipalities (92%) provide a dedicated social worker to each client, most of them involving other types of in-house specialists from within their organisation to support clients as needed. Only one municipality engages in an approach whereby a group of experts are jointly responsible for each client. The remaining municipalities do not use dedicated case managers for each client.

Although effective integration of vulnerable groups into society and labour market would requires co‑operation across service providers, this is not systematically and sufficiently done in Lithuania. Tight co‑operation practices are missing even between the PES and the Social Services Divisions in municipalities, which would be key in ensuring integrated social and employment services to the most vulnerable.4 Within the Lithuanian PES, counsellors can advise clients to contact specialists from other organisations, but this is not done systematically and generally they do not actively get into contact with other specialists themselves. Occasionally, these external specialists can be from a range of organisations, depending on the needs of the client, including Municipal Governments (and their social services centres), NGOs and other private organisations, education providers (e.g. vocational education providers, universities, training centres) and the Disability and Working Capacity Assessment Office.

In one‑quarter of municipalities, the social workers in the social services centres co‑operate systematically and formally with some other service providers to ensure more holistic support, while the rest contact other organisations more occasionally or only suggest the clients to contact specific service providers. As the clients of social workers might face an even wider and more complex range of challenges to integrate into society, the social workers can at times reach out to additional stakeholders compared to the PES – external specialists from municipal enterprises, prisons, foster-care institutions, institutional care providers for people with disabilities and healthcare providers.

Some municipalities aim to ensure better co‑ordination between the different services available in the municipality as well as nationally by using interinstitutional co‑ordinators. These co‑ordinators are not necessarily situated in the Social Services Departments, but in other divisions of the municipality, and their main task is to co‑ordinate the provision of educational assistance, social and health services. Although the perception of the usefulness of the support of these interinstitutional co‑ordinators is very high, their work is currently limited to services for children and young people.

While external organisations and experts are involved by municipalities above all to co‑ordinate service provision and propose more suitable integration pathways to the client, a similar approach is followed in the PES only regarding people with disabilities. For other groups, the PES primarily engages with other organisations to support a client after successful integration into the labour market (checking in and follow-up support).

3.6.2. Co‑operation with employers

In pursuing the goal of labour market integration of the client, the Lithuanian PES co‑operates with employers intensively throughout the integration process. These employer engagement activities include referring clients to open vacancies, engaging with employers to identify their needs and referring suitable clients, soliciting certain PES clients to employers and assisting the employer to adjust the tasks to meet the needs and/or abilities of the client, providing employer support services to employers to enable hiring and retaining of clients, providing follow-up supports to employers in the first months after hiring the client, as well as organising job fairs to enable jobseekers and employers meet.

Within the provision of social services at municipal level, employer engagement is significantly less widespread and extensive. Close to half (40%) of social service providers do not work with employers at all, and do not even mediate vacancies. One‑quarter (26%) of municipalities operate a very light touch approach, solely referring clients to open vacancies but without any direct contact with employers. The remaining municipal social services (33%) do work with employers, but potentially using somewhat less developed and intensive approach than adopted by the PES.

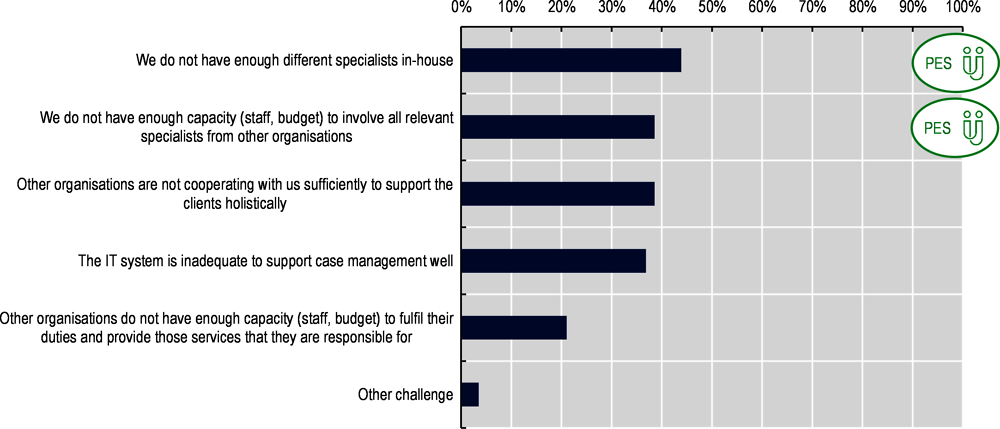

3.6.3. Challenges in case management

Regarding case management, the PES itself identifies two distinct main challenges (Figure 3.6). First, in working towards providing a more holistic support to clients, the PES does not have enough different specialists available to clients in-house. As noted earlier, the PES does have some specialised case managers, but the number of these specialists is not sufficient to cover the needs for more specialised and intensive approach. In addition, the PES might not have in-house all expertise that could be needed to support labour market integration. Second, the PES highlights capacity issues more generally – in terms of both budget and staff – that limit their ability to involve all relevant specialists from other organisations.

Figure 3.6. Greatest challenges in the case management process

Note: This figure is based on responses received to this question from 57 municipalities and the PES head office. The PES icon refers to the situation for the PES.

Source: OECD questionnaires to municipalities and the Lithuanian PES.

Regarding social services, municipalities each identify numerous simultaneous challenges in the case management process, the three largest being the lack of in-house specialists (44%), capacity restraints to involve all relevant specialists from other organisations (39%) and insufficient co‑operation from other organisations (39%) which limits the ability of their organisation or social services centre to support clients holistically (Figure 3.6). A significant proportion of municipalities also identify facing challenges as a result of an IT system that is inadequate to support case management (37%) and capacity issues in other organisations that affect their ability to fulfil their duties and provide the services for which they are responsible for (21%).

3.7. Recommendations on case management

To promote enhanced case management within employment and social services, Lithuania can take a number of important steps. This includes enhancing the co‑ordination across public service providers by establishing guidelines for co‑operation across public services, to encourage greater co‑operation and to facilitate more formal referral routes for clients who require multi-disciplinary support and services from more than one provider. In addition, employment services can benefit from enhanced employer engagement activities, particularly in supporting the labour market integration of vulnerable groups facing more complex barriers to employment.

3.7.1. Steps should be taken to enhance the co‑ordination and collaboration across public services

Co‑ordination and collaboration between stakeholders are key to ensure comprehensive service provision and thus successful integration of vulnerable groups into society and labour market (OECD, 2021[10]). To promote enhanced service provision to clients, Lithuania should make efforts to implement a framework for co‑operation across public service providers – particularly employment and social services. At present, integrated public service provision enabling a holistic overview of a client’s needs does not exist in Lithuania. This is particularly important in the case of the vulnerable individuals and those in the target groups (people with disabilities, ex-prisoners and young people leaving out-of-home care), who often have more complex situations requiring support and assistance from various service areas (e.g. employment, education, housing, health and social services). This framework for co‑operation should see an established practice through which social workers identify clients’ needs that can be met by the PES (and vice versa), establish formalised referral processes (ideally supported by integrated IT systems / data exchange) to track service provision to clients and progress along their employment and social integration pathways. Such framework would support enhanced co‑operation between social and employment services, encouraging them to work together rather than in separate silos as is the case at present.

An example of such close co‑operation between the PES and social services is that of L’accompagnement global (Global support) in France. This initiative sees support jointly provided by PES case managers and social works to jobseekers facing multiple simultaneous challenges or barriers to work (Pôle emploi, 2022[15]). PES workers provide assistance to directly promote the labour market integration of the individual, while the social worker assists in finding solutions to other problems faced (e.g. financial, legal, housing, health or mobility solutions). An evaluation of this initiative found it to be particularly beneficial for those jobseekers facing complex situations and distant from the labour market and has seen a 27% increase in exits to employment within 6 months of registering (Pôle emploi, 2018[16]). Similarly, Slovenia’s Social Activation Concept (Lemaić and Juvan, 2020[17]) provides co‑ordinated services to those furthest from the labour market, including the long-term unemployed and vulnerable groups. The programme aims to support both social and labour market inclusion and involves the integrated provision of various services (including employment, social, education and health). A similar solution is possible in Lithuania and would be greatly facilitated by the establishment of co‑operation guidelines between the PES and social service providers and enhanced shared IT solutions (including data exchange).

Alternatively, Lithuania could consider more fundamental changes in the institutional set-up to facilitate co‑ordinated service provision similarly to the example of Finland. Finland has successfully created a system of holistic services for young people via its Ohjaamo centres – though the implementation varies considerably across regions, (OECD, 2019[18]). Ohjaamo centres represent one‑stop-shops for young people, where services from the public, private and third sector are all provided side-by-side under the one roof, bringing together experts from the PES, social workers from municipalities, health service professionals and sometimes other services as well. Furthermore, understanding that the most vulnerable young people are not likely to voluntarily present at the centres, dedicated outreach staff (typically from municipalities) are in place. The operations of the Ohjaamo centres are supported by a common online digital engagement tool (Ohjaustaverkossa.fi), where this multi-disciplinary engagement and guidance can be provided online. While due to the population density, similar set-ups might not be efficient throughout Lithuania, these could be considered in some locations for population groups with more likelihood for multi-professional support (e.g. NEETs).

3.7.2. As social services providers do not engage with employers, co‑operation with PES is critical for labour market integration

The Lithuanian PES engages in a variety of employer engagement activities to promote the labour market integration of clients, whereas the majority of social service providers have little to no such co‑operation with employers. While a lack of interaction between social services and employers is understandable, the problem lies in the lack of co‑ordination with the PES in this area. Social services should have in place a process through which clients with labour market potential are identified and systematically referred to the PES. This includes clients who no longer require intensive social services and clients who can receive less intensive social services simultaneously with participation in active labour market policies (ALMPs) or employment.

3.7.3. Engagement with employers should be further improved in the Lithuanian PES

While employment incentives (via subsidies) represent a significant share of Lithuanian ALMP expenditure and can have significant positive effects on labour market outcomes, comprehensive support is lacking and tackling clients’ barriers to employment is not given enough priority (OECD, 2022[19]). Therefore, in supporting clients from vulnerable groups, there is scope to provide more comprehensive support to clients in this process – including in job mediation and job design. This can include job carving and job crafting which can be done to varying degrees to tailor the job to the individual and can be outsourced to third party organisation – for example, the Flemish PES works closely with the non-profit organisation GTB in providing job tailoring and other supports to jobseekers with disabilities (OECD, 2022[20]).

A similar example is seen in Malta, where the Lino Spiteri Foundation (LSF) – a public-private partnership organisation between the Maltese PES and a private company – provide dedicated employment services for jobseekers with disabilities and employers (OECD, 2022[20]). PES clients with disabilities are referred to LSF for intensive support. In 2020, LSF successfully placed 237 clients with disabilities into employment, with 80% sustaining in this employment and 52% of workers placed in carved jobs. Job carving is the responsibility of the LSF’s Corporate Relations Executives (CRs), who work directly with employers to carve jobs for prospective clients. There is scope for the Lithuanian PES to further enhance its existing work with employers in this area, including in combination with employment subsidies and job mediation.

A further relevant good example is the Candidate Explorer in the Netherlands, a tool developed by the PES in co‑operation with municipalities to increase the visibility of profiles of clients with disabilities among employers, pooling client data from both the PES register and the databases of municipalities (Kampers and van der Krogt, 2022[21]; Breedveld, 2020[22]). This transparency tool assists employers looking to fill vacancies, showing them anonymous profiles of potential candidates ranked against the criteria input by the employer. When interested in a candidate, case managers follow up with the client to explore their availability. At present, such a tool would not be possible in Lithuania – limited by the absence of sufficient IT infrastructure and data exchange between registers. However, this example highlights one of the many opportunities that advancements in the IT infrastructure could create for the provision of employment and social services and the engagement of employers in Lithuania.

3.8. IT infrastructure to support service provision and monitoring

This section of the chapter provides an overview of the IT infrastructure in place to support the provision of employment and social services. It explores the main characteristics of the current IT systems, the data collected on target groups, the level and detail of data exchange with other registers, the functionality and user-friendliness of the systems and, finally, the degree to which the existing IT infrastructure supports the monitoring and evaluation of services. Finally, the section puts forward a series of recommendations to improve the supporting IT infrastructure to Lithuanian employment and social services.

3.8.1. Main characteristics of the IT infrastructure

IT systems used in the PES

The Lithuanian PES uses two different IT systems to provide its services: 1) the central IT system of the PES (UT), and 2) the register of social enterprises (SIDA). While the UT is the backbone of the PES to provide services for jobseekers and employers, SIDA is dedicated to specific services to support jobseekers with disabilities through so-called social enterprises (above all wage subsidy schemes for a specific type of enterprises that create jobs for people with disabilities).

The UT and SIDA systems employ a rather similar IT architecture, consisting of an operational database (MS SQL platform) and web-based user interfaces for both internal users (staff in local employment offices) and for clients (such as jobseekers or service recipients). Back-up copies of the two systems are made for storing and archiving purposes and test environments are used for new developments in the operational IT systems.

Although both UT and SIDA have been introduced within the past ten years and have been subject to constant new developments to support changes in the policy design and in the legal environment,5 they will soon be replaced by a single combined system. Currently, the PES identifies considerable difficulties with both of the systems, due to the interfaces and systems themselves being outdated. Furthermore, the current systems are lacking such essential layers like classification and code list management and metadata management in the operational IT systems, as well as solutions to support data analytics well (data warehouse, data lake or data hub solutions).

IT systems in social protection and social services

To support the provision of social services and benefits and centrally collect the related data, the Ministry of Social Security and Labour has developed the Social Protection and Services Information System (SPIS). As it is mandatory to use this system when providing services listed in the Social Services Catalogue, 100% of social services centres at municipal level use this system,6 as well as NGOs and other private providers to whom the social services are contracted out to. Nevertheless, it does not mean that all municipalities and other providers use SPIS in its full capacity (all services and benefits in SPIS) and insert all data requested by the Ministry of Social Security and Labour. For two‑thirds (67%) of municipal social services, this is the sole IT infrastructure used by their organisation. Of those organisations that use multiple other systems, 21% of municipal social services use an internal IT system unique to their organisation and 19% use other shared IT systems that are also used by other organisations.

SPIS does not support (yet) social workers working with the prisoners while still in the correction institutions, as well as NGOs providing similar services. In addition, access to the internet as well as personal computers is currently limited at least in some of the prisons. Hence, the social workers in the prisons work mostly with papers, and share information with the Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Labour and municipalities via snail mail or an electronic document management system (i.e. not an IT system dedicated to support service provision).

SPIS consists of an operational IT system database (Sybase ASE and MongoDB) and user interfaces (ASP.NET) for internal users (staff in municipalities and social services centres), external service providers (contracted service providers) and clients (recipients of services). In addition, it comprises Web APIs to link to external IT systems/databases, and tools for classification and code list management, and metadata management in the operational database. SPIS is close to ten years old and under constant developments to keep up with changes in policy design and legal environment.

Although the architecture of SPIS has several major challenges, the Ministry of Social Security and Labour does not currently plan to significantly redesign it. It is problematic that the version of the MongoDB platform used for the operational database is currently not supported by its developer company. Furthermore, this platform has been criticised over the past years due to its security risks and technical challenges. In addition, SPIS does not include solutions to support data analysis well (data warehouse, data lake or data hub solutions), similarly to the IT systems used in the PES. SPIS does include a test environment, but not a back-up copy to store and archive data.

3.8.2. Data collected about the target groups and data exchange with other registers

As the provision of social and employment services is often not directly linked to the specific target groups that are the focus of this report, the three main IT systems (operational databases) do not generally contain specific variables to distinguish these groups, or at least not necessarily in a structured way that would support data analysis or the use of these data systematically in service provision (Table 3.1). SIDA, being a dedicated IT system for services for people with disabilities, contains data that enables also identifying them and their more specific circumstances, received from Disability and Working Capacity Assessment (Table 3.2). Also, SPIS users can access some data related to disabilities to support service provision, but not store these data in the SPIS itself. SPIS has also some data on foster-care institutions and foster families through related service provision. Employment counsellors insert some data on young people from foster-care and ex-prisoners in the UT register but based on the information received from the clients and not other administrative registers – potentially not covering all clients and not being collected in a structured way.

Also, data exchange to support holistic service provision is rather limited. SPIS itself contains information on social services and housing services, and SPIS users have access to view some data related to employment services. The UT register contains information on employment services, some information received externally on health services, and has some access to information on employment services provided by other organisations than PES. The PES does not have access to any information on social service provision that could help them to understand the needs of their clients better.

Table 3.1. Data specific to people with disabilities, care leavers and ex-prisoners in the IT systems used to provide employment and social services

|

Register reference |

UT |

SIDA |

SPIS |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Groups that are distinguishable in the database (e.g. the database contains a variable that enables to identify if a person belongs to this group) |

||||

|

People with disabilities |

Inserted by internal staff |

Received from other register(s) |

Staff can query these data from other registers, but not save in this system |

|

|

… work capacity |

Inserted by internal staff |

Received from other register(s) |

- |

|

|

… special needs |

Information received externally from the IT system |

Information received externally from the IT system |

- |

|

|

Young people who are or have recently been in foster-care institutions or in foster families |

Inserted by internal staff |

- |

Inserted by internal staff |

|

|

… from foster care institutions |

Inserted by internal staff |

- |

- |

|

|

… from foster families |

Inserted by internal staff |

- |

- |

|

|

People who are or have recently been in prison |

Inserted by internal staff |

- |

- |

|

|

… people about to leave a prison |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

… people in half-way houses or open-houses |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

… people on parole |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

… people recently released from prison (in the past 12 months) |

Inserted by internal staff |

- |

- |

|

|

Services that the operational IT system database has information on |

||||

|

Employment services and active labour market policies |

Received from other register(s) |

- |

Staff can query these data from other registers, but not save in this system |

|

|

… targeting people with disabilities |

Inserted by internal staff |

- |

- |

|

|

… targeting youth leaving foster-care |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

… targeting ex-prisoners |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

… provided by external organisations (such as NGOs) |

Staff can query these data from other registers, but not save in this system |

- |

- |

|

|

Social services |

- |

- |

Inserted by internal staff |

|

|

… targeting people with disabilities |

- |

- |

Staff can query these data from other registers, but not save in this system |

|

|

… targeting youth leaving foster-care |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

… targeting ex-prisoners |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

… provided by external organisations (e.g. NGOs) |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

… social services that are not in the Social Service Plan |

- |

- |

- |

|

|

Health services |

Received from other register(s) |

- |

- |

|

|

Housing services |

- |

- |

Inserted by internal staff |

|

|

Legal services |

- |

- |

- |

|

Note: Green shade – data received from other registers; yellow shade – data inserted in the IT system by staff providing services; orange shade – no data in the IT system. UT – central IT system of the PES. SIDA – register of social enterprises. SPIS – social protection and services information system.

Source: OECD questionnaires to municipalities, the Lithuanian PES and the Ministry of Social Security and Labour.

The data collection and exchange between operational databases is in place solely for the purpose of service provision and covers most of the essential needs for this purpose. The operational databases for employment and social services receive for example data from the employment register, tax register and the disability and working capacity assessment register, as well as provide some data for these registers themselves. Nevertheless, SPIS does not currently receive all data it needs to enable full check of benefit eligibility regarding some of the benefits. Also, data from other registers are possibly too limited to support pro‑active outreach to potential clients, identify their needs properly and provide services holistically across public sector. Furthermore, the operational databases of employment and social services do not receive any data from other registers specifically for the purposes of monitoring and evaluation, and data warehouse (or other similar) solutions to accommodate data exchange for data analytics do not exist.

Table 3.2. Data exchange between the IT systems of employment and social services and external registers

|

Direction of data exchange |

Organisations/registers from which this register regularly receives personal level data |

Organisations/registers that regularly receive personal level data from this register |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Register Reference |

UT |

SIDA |

SPIS |

UT |

SIDA |

SPIS |

|

SPIS |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

UT |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

SIDA |

|

|

|

+ |

|

|

|

Disability and Working Capacity Assessment Service |

|

+ |

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

Department of Prisons under the Ministry of Justice |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SODRA (employment data) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

VMI (State Tax Inspectorate) |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

|

+ |

|

ŠMMITC (education services) |

+ |

|

+ |

|

|

+ |

|

Health service providers |

|

|

|

|

|

+ |

|

Researchers, universities |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Note: UT – central IT system of the PES. SIDA – register of social enterprises. SPIS – social protection and services information system. Grey cell – N/A. “+” – some data are exchanged between the respective registers (not necessarily covering all needs for data exchange).

Source: OECD questionnaires to municipalities, the Lithuanian PES and the Ministry of Social Security and Labour.

3.8.3. Functionality and user-friendliness of the IT infrastructure to support service provision

Functionalities present in the IT systems

In terms of user interface functionality, the two primary systems used by the PES support various elements of service provision. Both the UT and SIDA facilitate the managing of client information and communication (booking meetings and sending messages to clients). However, SIDA also facilitates supporting the identification of people (with disabilities) who are not yet clients. The UT system is the primary system used for the PES case management process, thus supporting the identification of client needs (based on data in the IT system), development of action plans, application processes for clients (for services, measures and benefits) and the referral of a client to specific services and measures. Both the UT and SIDA include some functionality to track the progress of specific clients, such as the status of service participation (i.e. are they still participating in the given programme, including some services provided by external organisations). As the primary objective of SIDA is to support managing wage subsidies for people with disabilities in social enterprises, it enables additionally the submission of payment requests by the social enterprises.

Unlike the systems employed by the PES, the functionality of the user interface of SPIS is rather limited. Instead, the SPIS mostly assists in identifying people to reach out to (i.e. provides contact details for people not yet clients) and in facilitating the application processes for clients. The systems in PES and SPIS also enable collecting data on clients and service provision through the service provision process.

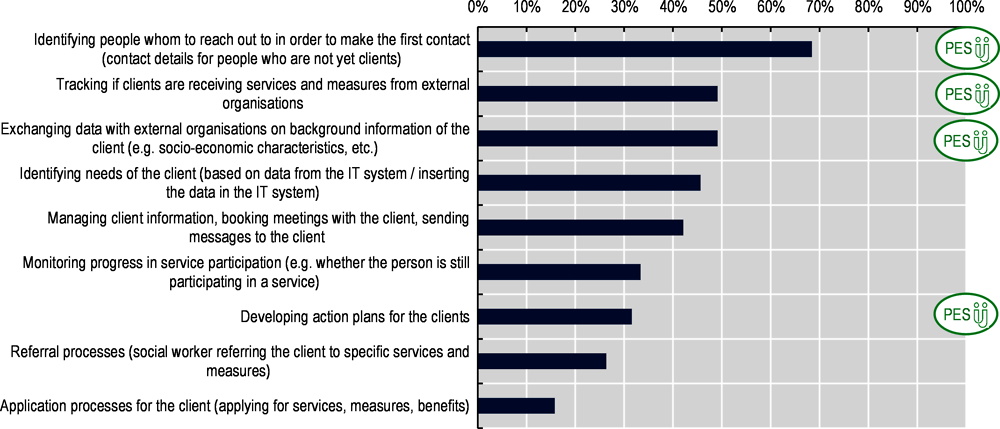

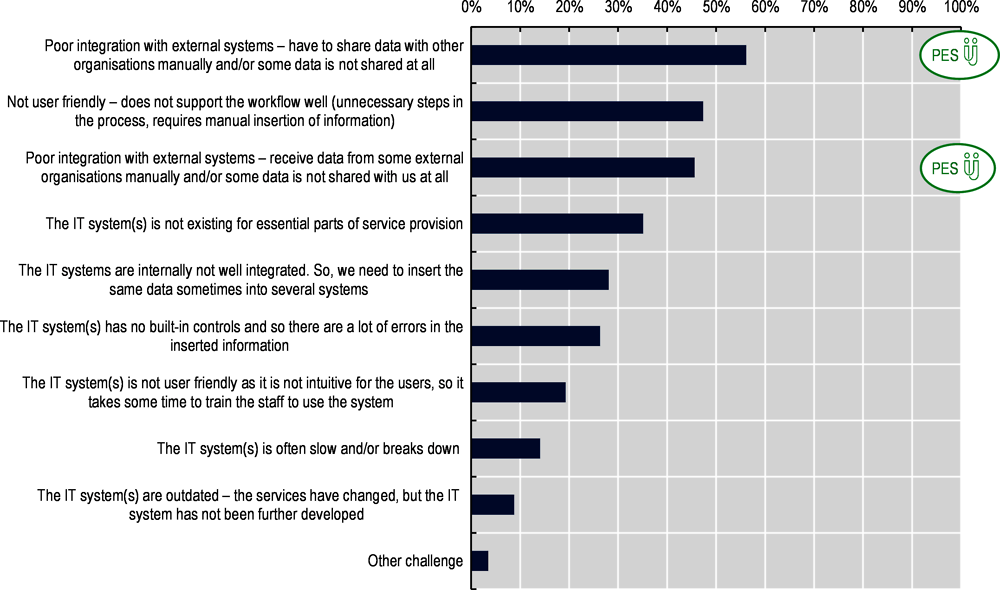

Assessments by the users

While the IT systems used by the Lithuanian PES support service provision in wide functionality, there is scope for significant improvements (Figure 3.7). In relation to outreach efforts, the existing IT infrastructure is essentially not supporting the PES in identifying and accessing contact details for individuals not yet clients as the UT system does not receive relevant data from other registers. In addition, the IT systems do not sufficiently support the case management process. This includes insufficient support to key case management activities such as the development of client action plans, tracking the status of clients referred to external organisations and the receipt of data from external organisations on the background information of the client. The PES central office, as well as users in the local PES offices, recognise the need to replace the IT infrastructure with a more modern one that would enhance user experience, enabling taking better use of the available data and support more effective and efficient service provision.

Figure 3.7. Segments of service provision that are insufficiently supported with IT infrastructure

Note: This figure is based on responses received to this question from 57 municipalities and the PES head office. The PES icon refers to the situation for the PES.

Source: OECD questionnaires to municipalities and the Lithuanian PES.

At municipal level, social service providers too face many problems in areas of service provision due to insufficient or lack of supporting IT infrastructure (related to SPIS as well as potentially other IT systems that they use). The three largest areas where the IT infrastructure does not support the users sufficiently, are outreach to individuals not yet clients (experienced in 68% of municipalities), tracking the status of clients referred to services and measures provided by external organisations (49%) and exchanging data on clients with outside organisations (49%).

The underlying reason for many of the challenges identified by the users are partly related to gaps in data exchange between registers. In some cases, the organisations have found alternative ways to exchange information, such as via emails and Excel tables), which is however inefficient, as well as provides lower security than data exchange taking place between IT systems. As such, these working methods have managed to overcome to some degree the technical challenges in data exchange, but not the legal challenges related to data protection.

3.8.4. IT infrastructure supporting monitoring and evaluation

Both the UT and SIDA include limited functionality to generate some monitoring statistics (such as overviews of counsellors’ portfolios or summaries of local office client profiles). In addition, SPIS facilitates the generation of some essential statistics.

Tools for monitoring and evaluation in the IT systems

As highlighted in the previous sub-sections, none of the IT systems used to provide employment and social services involves modern solutions to support data analytics (such as monitoring statistics, evaluation, research). Staff providing services, as well as statisticians and analysts can query data and statistics for monitoring directly from the operational databases. In the UT and SIDA, the queries are integrated in the user interfaces that are also used by employment counsellors to provide the services. SPIS uses a Business Intelligence (BI) tool to enable querying statistics (Sybase IQ (current product on the market called SAP IQ) and Information Builders Web Focus products taken into use in 2013‑14). The PES has also tested MS Power BI for monitoring and statistics purposes, also directly linked to the operational databases, but has currently no specific plan to adopt it.7