This chapter provides a comprehensive mapping of public services and programmes in Lithuania, with close attention to regional disparities and the attention devoted to people with disabilities, young people leaving care and people leaving prison. The chapter starts with a detailed overview of social services across municipalities, covering the planning, availability, targeting, uptake, providers, and funding of social service provision. The chapter then continues with a brief overview of other types of public services, including education, employment, and health services, and concludes with a set of recommendations to improve social service design in Lithuania.

Personalised Public Services for People in Vulnerable Situations in Lithuania

4. Mapping of services for people in vulnerable situations in Lithuania

Abstract

4.1. Introduction

Many services are available for people in vulnerable situations in Lithuania. However, for some people with multiple and complex needs who require a range of services, such as people with disabilities, people leaving prison and young people leaving care, more comprehensive, integrated services, tailored to meet individual needs are required. This chapter provides a detailed overview of public services provision in Lithuania, focusing not only on social services, but also other types of public services, including education, employment, and health services. The information provided in this chapter is based on virtual consultations with Lithuanian stakeholders, desk research, administrative data review, and a survey for Lithuanian municipalities (see Chapter 1 for further information).

4.2. Social services

4.2.1. Planning of social services provision

The Catalogue of social services (hereinafter referred to as “the Catalogue”), which was introduced in 2006, sets out a list of services that can be provided in Lithuania, and describes them in terms of content, purpose, beneficiaries, place of supply, and duration of the service, among others. The Catalogue serves to harmonise the provision of social services across the country by clearly defining what each service must consist of, who can get access to it, and under which conditions. The Catalogue contains a comprehensive list of social services, but such list is not exhaustive.

According to the Law No X‑493 on Social Services, each year, municipalities are responsible for designing and approving a social services plan, which determines the extent and types of social services that will be provided in the municipality during the upcoming year. Theoretically, municipalities are free to decide on the provision of services that are not part of the Catalogue, although this does not seem to be common practice. Municipalities rely heavily on the social services Catalogue for the definition of their annual plans and do not often deviate from the pre‑existing list of services. In fact, according to OECD’s municipality survey, 54% of Lithuanian municipalities never include social services outside of the Catalogue in their annual plans, or only do so exceptionally.

This practice is problematic, because the Catalogue is seen as a rather static tool that has barely evolved over time. The list of social services enumerated in the Catalogue has hardly changed since it was approved in 2006, which could trigger gaps in service provision when new societal needs arise.

In addition to consulting the Catalogue, municipalities report conducting additional research and statistical analyses to decide on the type and extent of social services to include in their annual plans. However, it seems this planning activity is largely based on the information gathered retrospectively from service usage rather than forward-looking: while 96% of municipalities assess the social services plan of the previous year for the design for their annual plan, only 40% report conducting additional statistical research to analyse the need for providing additional or different services.

When planning the provision of social services, municipalities do not explicitly target each of the vulnerable groups of interest for this project. Indeed, while the majority of municipalities (91%) included specific indicators and/or needs assessments for people with disabilities in their 2020 social services plans, no specific reference was made for the groups of young people leaving care and people leaving prison. The OECD analysis of the governance of public services and involvement of NGOs in public services in Lithuania provides further insights on the involvement of NGOs in municipality social services planning.

4.2.2. Availability of social services across municipalities

According to the Law on Social Services, social services are aimed at “assisting a person or family who, because of age, disability, or social risk and challenges, have not acquired or have lost the ability to independently care for their private life and participate into society”. In line with the Catalogue, Lithuanian municipalities can provide both “general” social services, as well as “special” services to those vulnerable individuals and families who present needs that are more acute.1 A comprehensive list of the social services included in the Catalogue can be found in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1. General and special social services listed in the Catalogue

|

General services |

Special services |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Social assistance services |

Care services |

|

|

Information |

Home assistance |

Day social care |

|

Counselling |

Support to develop or restore social skills |

Short-term social care |

|

Mediation and representation |

Support for independent living |

Long-term social care |

|

Provision of food |

Accommodation in night shelters |

Temporary respite (care) |

|

Provision of clothing and footwear |

Accommodation in hostels |

|

|

Transport |

Accommodation in other forms of temporary accommodation |

|

|

Socio-cultural activities |

Intensive‑crisis resolution assistance |

|

|

Personal hygiene |

Psychosocial assistance |

|

|

Open youth work |

Temporary respite (assistance) |

|

|

Youth work on the street |

Support for carers, adoptive parents and guardians |

|

|

Mobile youth work |

Day-care services for children |

|

Source: Order No 43‑1570 on the Adoption of the Catalogue of Social Services.

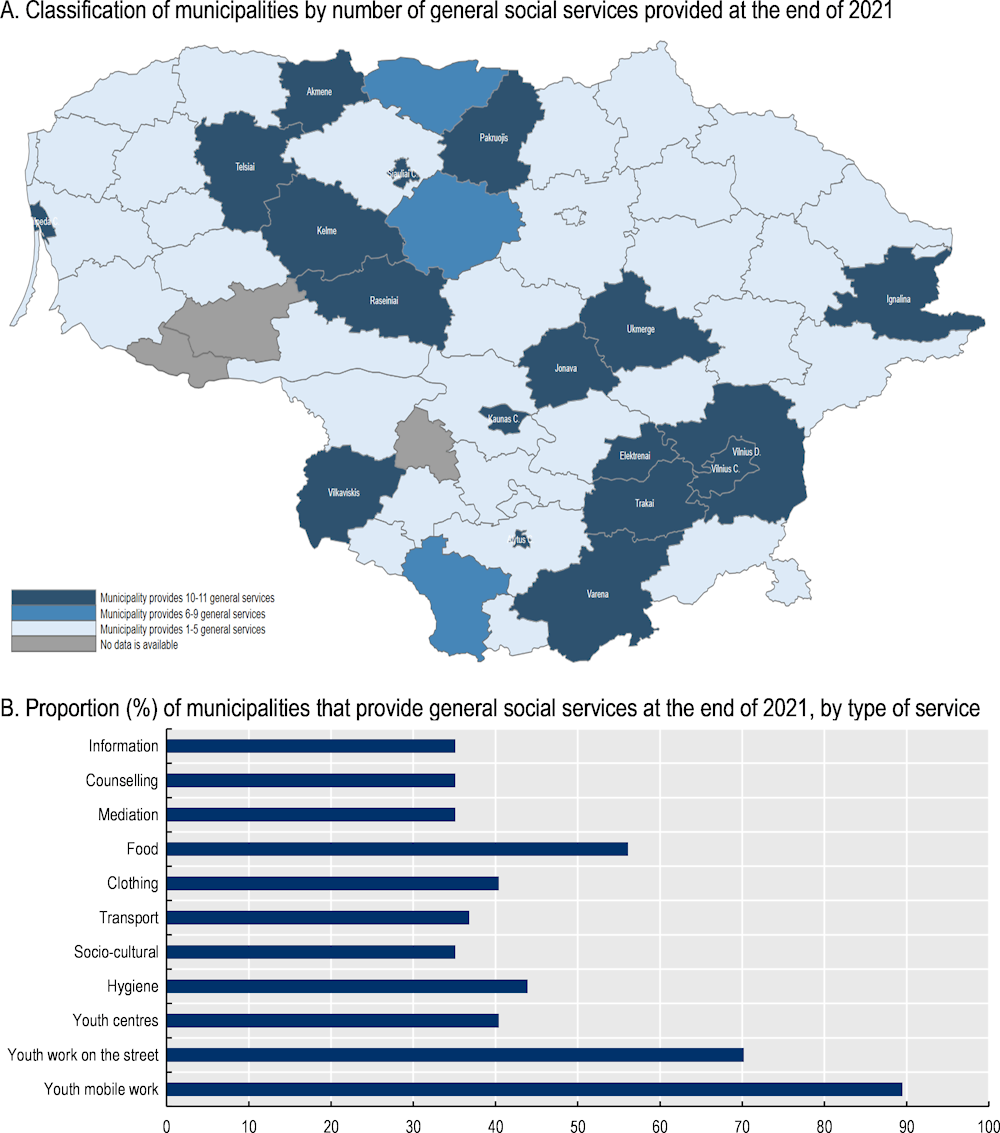

General social services include information, counselling and mediation services; provision of food, clothing and transportation; personal hygiene services; socio-cultural activities; and a variety of youth targeted services delivered across youth centres, youth gathering spaces (parks, cafes, sports clubs, etc.) and mobile infrastructure. The availability of general social services is highly polarised across Lithuanian municipalities. Almost one‑third of municipalities offer all general social services included in the Catalogue, while most of the remaining municipalities offer less than half of the general services listed there (Figure 4.1, Panel A). The most common general services are youth work on the street and mobile youth work, which are provided in 70% and 90% of the municipalities, respectively (Figure 4.1, Panel B). Youth work on the street is provided at public youth gathering spaces such as parks, cafes, or sport clubs. It is aimed at engaging with young people who might be experiencing difficulties related to criminal behaviour or substance abuse, in order to help them rebuild links with their social environment and facilitate their access to other services provided to young people in their municipality. Instead, mobile youth work is delivered where there is no youth work infrastructure and it aims to help young people solve problems and difficulties (educational, employment-related, etc.) by creating a secure, open and informal environment where they can develop their social skills together with other peers and engage more actively with their community.

Figure 4.1. Availability of general social services across Lithuanian municipalities

Source: OECD’s municipality survey (see Chapter 1).

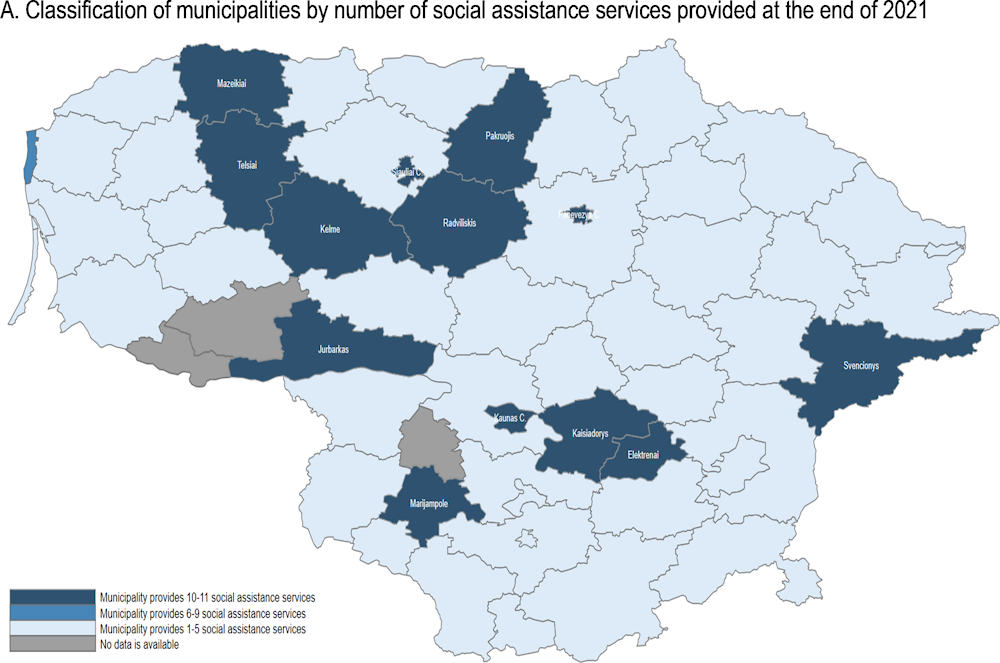

Special social services can be provided either in the form of temporary “social assistance”, or more permanent “social care”. Social assistance services include measures such as home visits, support to develop or restore social skills, support for independent living, accommodation at night shelters or other forms of temporary accommodation, psychosocial and intensive crisis-resolution assistance, support and assistance for carers, adoptive parents and guardians and day-care services for children. Social care, on the other hand, includes the complete range of services provided to a person who requires constant care from a specialist. Social care can be provided at varying frequency (day care, short-term care, or long-term care) and it can be arranged either at the beneficiary’s home or at institutions created for that purpose.

As it is the case with the coverage of general social services, the municipal offer for social assistance services hides considerable variation across municipalities. Only 23% of municipalities offer all social assistance services available in the Catalogue, while most of the remaining ones offer four or less (Figure 4.2, Panel A). The most common services of this type are accommodation in hostels and other forms of temporary accommodation, which are provided in 65% and 79% of municipalities, respectively (Figure 4.2, Panel B).

With regards to social care, most municipalities (91%) have all services described in the Catalogue available. Among those that do not offer all social care services (5 municipalities), temporary “respite care” appears to be available in most of them. Respite care is a social service targeted to the carer of a person with disabilities who already benefits from other social assistance services. This service allows the carer to take a break from their caring responsibilities and achieve a better life and family balance, while resting assured that the person they take care of is being looked after by someone else. The help comes from short-term care or help at the house (up to 2 times a week), to day-care (up to 2 times a week), to longer-term care (up to 14 days, and in exceptional cases, up to 90 days a year).

Figure 4.2. Availability of social assistance services

Source: OECD’s municipality survey.

4.2.3. Targeting of social services

Each of the general and special social services described in the Catalogue is linked to a list of vulnerable groups who are entitled to benefit from that service in particular. The definition of some of these groups can be considered relatively broad, and as indicated in the Law on Social Services, the need for social services of an individual or a family is ultimately determined by the social workers appointed by the municipal authority according to the official procedure. The OECD analysis of the operating models and IT infrastructure in providing employment and social services in Lithuania provides further insights on the processes of identifying needs for services. The definition of some the most recurrent beneficiary groups listed in the Catalogue is provided in Box 4.1.

While children and adults with disabilities are clearly defined as specific target groups for most social services in the Catalogue, young care leavers and people leaving prison do not constitute specific target groups per se. However, they can, depending on the evaluation by the social worker, fall under the categories “adults at social risk” or “young people with fewer opportunities”. Instead, people with disabilities are listed as target beneficiaries for all specialised social services listed in the Catalogue (both social assistance and social care), as well as all general services, except for temporary accommodation at night shelters and other forms of temporary accommodation, intensive crisis-resolution assistance services, and support for adoptive parents and guardians. The OECD analysis of the governance of public services provides further insights on the extent to which vulnerable groups are clearly identified across areas beyond social services.

Box 4.1. Potential beneficiaries of social services according to the Catalogue

Adult with disabilities: A person of working age who, due to disability, is partially or totally deprived of the ability to take care of personal (family) life and participate in society independently.

Child with disabilities: A person under the age of 18 who, due to disability, is partially or totally deprived of autonomy appropriate to his or her age, and whose opportunities to develop and participate in society are limited.

Elder: A person who has reached the retirement age, and who, due to age, has been partially or totally deprived of the ability to independently take care of personal (family) life and participate in society.

Individuals and families at social risk: “Social risk of exclusion” can refer to a variety of circumstances. These include: lack of social skills of adult family members to provide appropriate care and education for minor children; impossibility of adult family members to ensure the full physical, mental, spiritual, and moral development and safety conditions for minor children; involvement in the perpetration of criminal offences; abuse or addiction to alcohol, narcotics, psychotropic substances or gambling; and homelessness, among others.

Young people with fewer opportunities: Lithuania follows the Erasmus+ definition of young people with fewer opportunities (European Comission, 2019[1]). This concept refers to young people who are at a disadvantage compared to their peers because they face one or more of the following exclusion factors: disability, health problems, educational difficulties, cultural differences, economic obstacles, social obstacles or geographic obstacles. These exclusion factors are considered to represent barriers for their inclusion in society (Council of Europe, 2017[2]).

Furthermore, data from the Department of Disability Affairs (2022[3]) shows that all Lithuanian municipalities currently provide “social rehabilitation services” to people with disabilities. These services are provided by non-governmental organisations (NGOs) that have been operating in the field of social integration of people with disabilities for at least a year. These services include, among others: individual assistance to develop and/or maintain independent living abilities, social and work skills, cognitive functions, and cultural and artistic expressions, escorting or transportation services to public institutions, information and counselling services, and emotional support for family members. The implementation of social rehabilitation services is part of Lithuania’s long-term strategy to better integrate people with disabilities in their communities through a transition from institutionalised care to community services (Box 4.2). For this purpose, these types of services have been provided across Lithuanian municipalities since the approval of the Order No A1‑1211 in 2014 on the Transition from Institutional Care to Family and Community-Based Services for Persons with Disabilities and Children without Parental Care.

Data from the Department of Disability Affairs (2021[4]) also shows that in 2021, 49 Lithuanian municipalities provided “personal assistance” services to people with disabilities, which are not included in the Catalogue. A personal assistant is an individual made available to all disabled people for whom this need has been identified, regardless of their age, and severity or nature of the disability. The need for personal assistance is assessed individually and determined for one year in accordance with the procedure established by the Ministry of Social Security and Labour. Priority is given to those who are in formal education, working, looking for a job through the public employment service (PES) or other organisations, or living alone. Personal assistants provide help related to personal hygiene, accompany the person to healthcare visits and other state or municipal institutions, and assist in establishing and maintaining social relations, among others.

Up to 2021, young care leavers did not constitute an independent target group of the social services described in the Catalogue, but their defining characteristics made them potentially eligible to benefit from most of those services. Indeed, “adults at risk of social exclusion” and “young people with fewer opportunities” are listed as target groups for most general and social assistance services. Since November 2021, however, a new “leaving care” service was included in the Catalogue, and young care leavers are clearly defined as a beneficiary group for it. In particular, the Catalogue establishes that adults up to the age of 24 who have been provided with social care in a social care institution can benefit from this service.

Box 4.2. Action Plan 2014 – 2023 for the Transition from Institutional Care to Family and Community-Based Services for Persons with Disabilities and Children without Parental Care

The Action Plan 2014‑23 envisages a set of consistent and co‑ordinated actions aimed to provide an appropriate emotional and social environment for people with disabilities (including children and youth) and children deprived of parental care, encouraging their independent living and personality development, and increasing their possibilities of a successful integration into society. The strategic goal of the Action Plan is to develop a system of integrated service provision with a clear focus on preventing both people with disabilities and children deprived from parental care from entering institutional care.

As a result of the Action Plan, the number of adults with disabilities in care homes decreased by 10% between 2016 and 2020, and at the same time, alternative and additional services were established for people with disabilities who live in their communities. By the end of 2021, 33 group-living homes had been established in the country, providing accommodation to 257 adults and 28 children with disabilities (Globa Šeima Bendruomenė, 2022[5]). Such group-living homes can accommodate up to 10 independent adults with disabilities who receive regular specialised assistance. Residents in group-living homes receive the necessary services in these homes and enjoy other community-based services aimed at restoring and developing their social and independent living.

Similarly, the number of institutions for children deprived from parental care decreased from 90 in 2016 to 61 in 2020, while the number of children in these institutions decreased by 70% during that period. The implementation of the Action Plan also led, in 2018, to the recognition of professional foster care as an official form of alternative care (Opening Doors, 2018[6]). Since then, children under the age of three who are left without parental care are placed directly in professional foster care. Furthermore, Lithuanian municipalities are now responsible for developing a network of care centres responsible for recruitment, training and support of professional foster carers.

Despite the advances made, discussions with stakeholders revealed that this deinstitutionalisation process has been short-lived, and only focused on the restructuring of the largest care homes. As a result, people with disabilities and their families continue experiencing a lack of support services, which often leads to large shares of informal care within the household. This substantial involvement in the care of people with disabilities is often highly problematic for the labour market integration of family members, especially women.

The “leaving care” service consists of a set of interrelated measures provided to help young people leaving care settings in adapting to their social environment and in developing their social skills and ability to deal with potential challenges. The ultimate goal is to facilitate their social integration within the community. According to the OECD’s municipality survey, six municipalities offered such service in 2021.

Unlike people with disabilities and young care leavers, people leaving prison are not a specific target group of the social services described in the Catalogue. Their defining characteristics, however, make them eligible for benefiting from those services targeted to “adults at risk of social exclusion” and “young people with fewer opportunities”. Moreover, “persons released from correctional bodies who have not elapsed for more than 12 months from the date of their release from the correctional body” are eligible for benefitting from temporary accommodation at night shelter, support to develop or restore their social skills, and intensive crisis-resolution assistance services. Regarding social care services, adults who suffer from psychoactive substance abuse disorders are entitled to receiving psychological and social rehabilitation services in the short-term.

In 2021, 11 municipalities provided additional social services for people leaving prison, with “social reintegration or rehabilitation” being the most recurrent one. Social reintegration services are provided to people released (or close to be released) from correctional institutions to help them establish or restore their social connections and to encourage their participation in the community. The ultimate goals of these services are to promote the resocialisation and reintegration of the inmates into society, as well as to reduce recidivism rates. Social reintegration services often consist of two stages: the first one handled within the correctional institution prior to the prisoner’s release, and the second one implemented by the municipality or NGOs once the person has left the penitentiary.

However, according to a study conducted by researchers at the Law Institute of Lithuania, social rehabilitation services provided in Lithuanian correctional facilities tend to be incomplete and short lived (LIL, 2018[7]). The study concludes that social workers in Lithuanian prisons have too many duties and responsibilities, which has a negative effect on the implementation and quality of the reintegration services provided. This finding is line with the statistics provided by the Ministry of Justice, which state that in 2020 there were around 25 social workers for an inmate population of over 4 500. Moreover, the research considers that the time provision for the preparation and implementation of the individual social rehabilitation plan is too short, which makes it very difficult to deliver rehabilitation services that are effective and of good quality.

As a response to this situation, the Prison Department under the Ministry of Justice is currently implementing the pilot initiative “Development of Quality Based Lithuanian Correctional Service System” (Prison Department, 2022[8]). The project aims to improve the provision of reintegration services by providing professional training to Lithuanian penitentiary staff, investing in the construction of halfway houses, and developing an innovative release model from correctional facilities in co‑operation with NGOs. Through the implementation of this new release model, it is expected that NGO services will be made more accessible to both inmates and probationers. In particular, it is estimated that around 1 000 people serving their sentence in the pilot institutions will get access to reintegration services provided by NGOs. Among those, around 240 inmates could be released on parole or transferred to halfway houses as a result of a more successful rehabilitation process.

4.2.4. Uptake of social services

As indicated above, Lithuanian municipalities are responsible for the planning and provision of social services in their territory. To undertake this planning activity, most of them largely rely on the information gathered retrospectively from service usage in the previous year. This is problematic, because there is a generalised lack of sufficient and reliable data on services provided to vulnerable groups, which translates into the development of services being carried out without a comprehensive and realistic assessment of the population needs in the territory.

Data on the use of social services is not centralised, but spread across different sources. Furthermore, each institution reports on a different set of indicators, and makes use of different disaggregation categories and data collection methods, making data comparison across institutions not feasible.

One of the key sources of information on the uptake of social services in the country is the Social Protection Information System (SPIS), which aggregates administrative data on the provision of public benefits and services at the municipal level. The following paragraphs provide an overview of the statistics obtained from the data analytics layer within the SPIS IT system, commonly referred to as SPIS showcases.2 The OECD analysis on operating models and IT infrastructure in providing employment and social services in Lithuania describes the SPIS in more detail, including data collected in its operational database and the showcases tool.

SPIS data is disaggregated by four types of beneficiaries: elder people, families, people with disabilities, and people at risk of social exclusion. Young care leavers and people leaving prison do not constitute separate disaggregation categories for this dataset.

According to SPIS data, around 13 000 people at risk of social exclusion received general social services in 2021. This figure increased up to almost 24 000 in the case of social assistance services. There were also more than 5 400 beneficiaries of social care, out of which around 70% were people with disabilities (Table 4.2).

Table 4.2. Number of recipients of social services in 2021, by type of service and beneficiary group

|

Service |

Social exclusion |

Disabilities |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

General services |

|||

|

Information |

3 799 |

- |

3 799 |

|

Counselling |

3 819 |

- |

3 819 |

|

Mediation and representation |

2 147 |

- |

2 147 |

|

Provision of food |

630 |

- |

630 |

|

Provision of clothing and footwear |

6 |

- |

6 |

|

Transport |

2 071 |

- |

2 071 |

|

Socio-cultural activities |

235 |

- |

235 |

|

Personal hygiene |

562 |

- |

562 |

|

Total |

13 269 |

- |

13 269 |

|

Special services – social assistance |

|||

|

Home assistance |

6 193 |

- |

6 193 |

|

Support to develop or restore social skills |

15 562 |

- |

15 562 |

|

Support for independent living |

290 |

- |

290 |

|

Accommodation in night shelters |

229 |

- |

229 |

|

Accommodation in hostels |

451 |

- |

451 |

|

Accommodation in other forms of temporary accommodation |

6 |

- |

6 |

|

Intensive crisis-resolution assistance |

591 |

- |

591 |

|

Psychosocial assistance |

371 |

- |

371 |

|

Temporary respite (assistance) |

3 |

- |

3 |

|

Total |

23 696 |

- |

23 696 |

|

Special services – care |

|||

|

Day social care |

1 561 |

1 392 |

2 953 |

|

Short-term social care |

164 |

147 |

311 |

|

Long-term social care |

- |

2 211 |

2 211 |

|

Temporary respite (care) |

2 |

- |

2 |

|

Total |

1 727 |

3 750 |

5 477 |

Source: Lithuania’s SPIS.

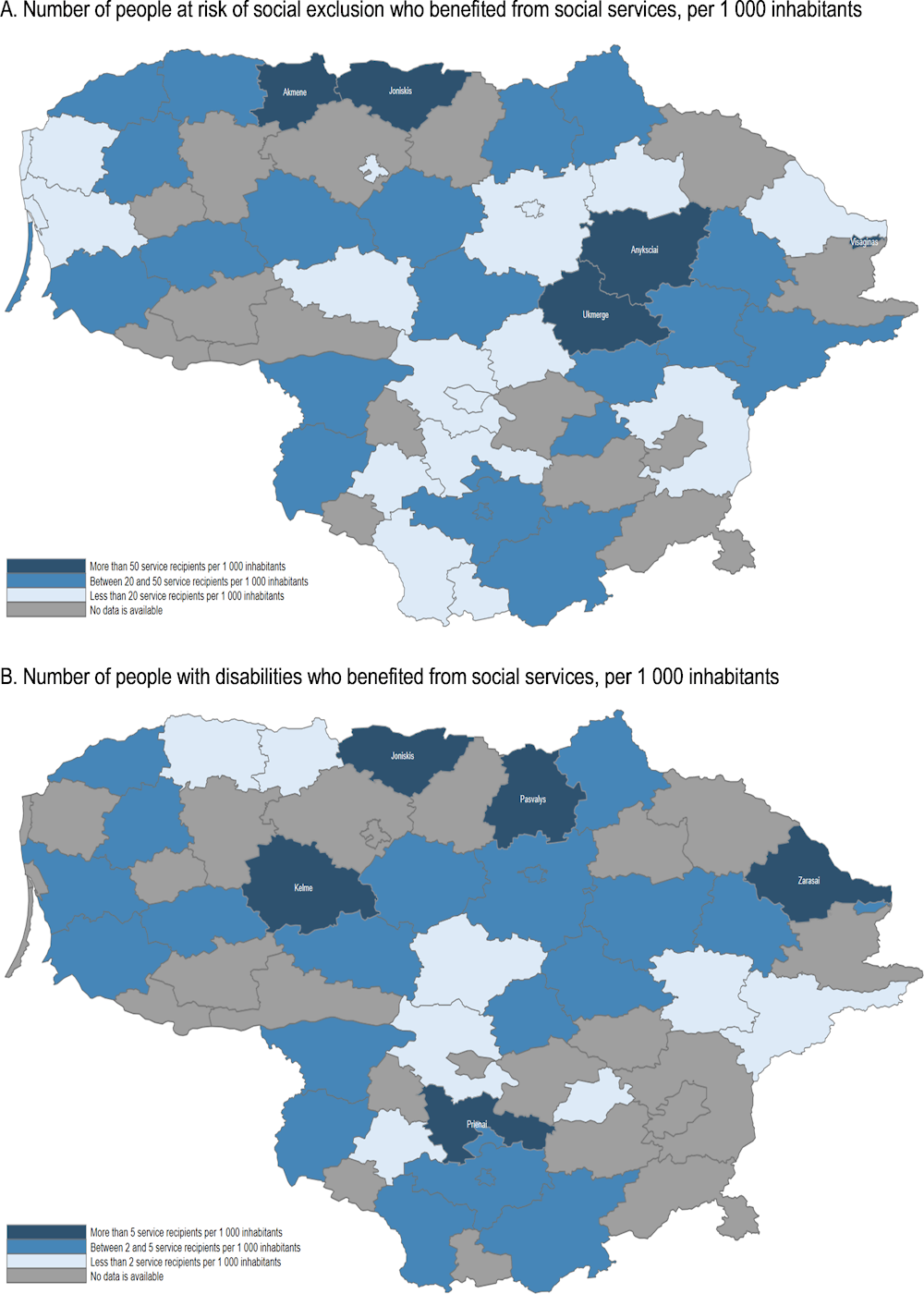

As it occurs with service provision, the number of recipients of social services per 1 000 people hides considerable variation across municipalities. In the case of services for persons at risk of social exclusion, there are only five municipalities where the number of recipients of social services per 1 000 people is larger than 50 (Figure 4.3, Panel A). In another quarter of the municipalities, however, this number drops to less than 20 service recipients. Similarly, there are only five municipalities where the number of recipients with disabilities who are recipients of social services is larger than five (Figure 4.3, Panel B).

Figure 4.3. Number of recipients of social services across Lithuanian municipalities in 2021

Source: SPIS.

In general terms, however, the data obtained from the SPIS reporting tool does not seem to be comprehensive. First, and despite the fact that the SPIS collects information on public support measures that go beyond the Catalogue (e.g. one‑time benefits for pregnant women, benefits for the children of military staff, etc.), not all the social services listed in the Catalogue are included in the showcase reports. For example, the reports do not provide information on the number of beneficiaries of youth work services – which is one of the services most frequently provided in municipalities (Figure 4.1). Secondly, as shown in Table 4.2, the SPIS reports do not provide information on the provision of general social services or special assistance services for people with disabilities. Data is only available for social care, and even then, the numbers of service recipients appear to differ from those provided by other statistical sources such as the national survey of social services. The OECD analysis on operating models and IT infrastructure in providing employment and social services in Lithuania provides further information on the users’ feedback on the SPIS reporting tool.

Another key source of information on the recipients of social services is the Lithuanian Department of Statistics’ portal.3 Statistics on social services from this source are based on the results from the annual national survey of social services. Data is disaggregated by the same beneficiary groups as in the SPIS (older people, people with disabilities, and people at risk of social exclusion). Young care leavers and people leaving prison do not constitute separate disaggregation categories for this set of statistics.

Regarding people at risk of social exclusion, the national survey of social services estimates that around 18 000 people received social assistance at day centres in 2020. Moreover, around 7 250 people received social services in crisis and psychological and social rehabilitation centres. More than 4 000 people made use of accommodation at temporary living facilities. Almost 1 500 people stayed in shelters, out of which 122 were people leaving prison. The latter figure implies an 85% increase with respect to the previous year.

Furthermore, according to the portal, 4 465 adults and 932 children with disabilities received social support services in their homes in 2020. Around 16 000 adults and 4 000 children with disabilities received care support at day centres, and 6 000 adults and 73 children resided in social care institutions for people with disabilities. Additional information obtained from the Disability Affairs Department (2022[3]) shows that more than 24 000 people with disabilities benefited from social rehabilitation services in 2019.

In conclusion, available statistics on the number of social service users is neither comprehensive nor accurate, which can hinder the planning and implementation process of social services. Furthermore, municipalities do not have detailed and up to date information on the total population who meet the criteria to benefit from certain social services but are not currently making use of them (i.e. target population). This discrepancy means that many decisions on the development of social services are made without information on the real needs for social services, which can lead to exclusion errors in the targeting process. For example, in a recent assessment of services conducted by the National Audit Office of Lithuania (2020[9]), with 416 people of working age with disabilities, it was demonstrated that municipalities did not have any information on the 35% of individuals who had not applied for support services.

4.2.5. Providers of social service

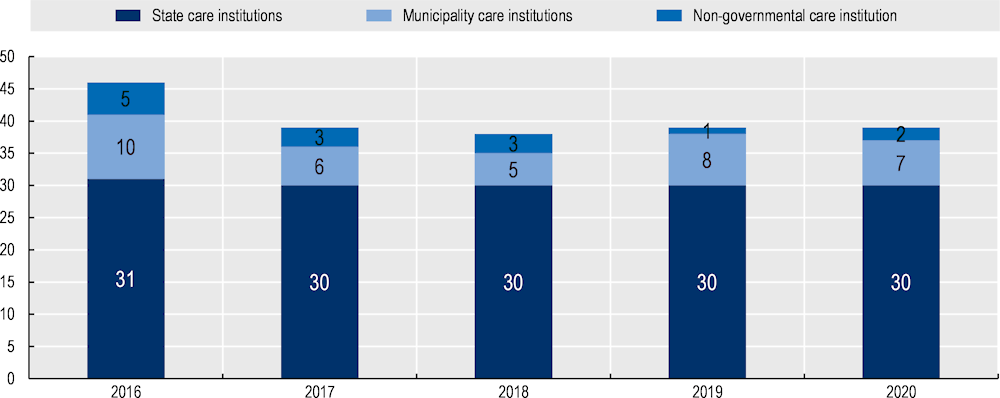

According to the Law on Social Services, both private and public institutions can provide social services in Lithuania, and individuals can choose freely among all accredited or licensed service providers. Nevertheless, and although the law entered into force in 2006, a free market of social services providers is not yet the reality, and state and municipal institutions have traditionally been the predominant provider of social services in the country. For example, in 2020, the proportion of state and municipal care institutions providing care to adults with disabilities was 77% and 18%, respectively (Figure 4.4). Similarly, 90% of people who made use of shelters in 2020, stayed in a municipal facility (Statistics Lithuania, 2022[10]). Only 162 people stayed in a shelter run by an NGO.

Figure 4.4. Types of institutions providing care services to adults with disabilities

Note: Group-living homes are not included because data is not available prior to 2019. A total of 29 and 33 group-living homes existed in 2019 and 2020, respectively.

Source: Statistics Lithuania (2022[10]), Database of indicators, https://osp.stat.gov.lt/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize#/.

The strong prevalence of municipal institutions in the delivery of social services is confirmed by the OECD’s municipality survey: all but one Lithuanian municipality confirmed that municipal institutions are involved in the provision of social services in their territory. Furthermore, 80% and 96% of municipalities mentioned public institutions and NGOs as social service providers, respectively.4 On the contrary, only half of the Lithuanian municipalities confirmed that the private sector (not NGOs) is involved in the provision of social services in the municipality. One of the key reasons behind this situation is that the outsourcing of social services provision to private institutions needs to follow a public procurement process where price considerations are often determinant for the contract award. This process puts private institutions, and in particular those which do not yet have the necessary infrastructure in place, in a disadvantaged position for competition. The OECD analysis of the governance of public services and involvement of NGOs in public services in Lithuania provides further insights on the key challenges limiting NGOs’ delivery of public services.

Despite the fact that the law guarantees individuals’ freedom in the choice of service provider, self-payment of social services is in reality a key determinant of such a decision (Radišauskienė and Žalimienė, 2009[11]). Prices for social services are not officially regulated and therefore different institutions can ask for different prices even when providing the same service. Given that the maximum amount that can be financed by the municipality and/or the state is determined, if a person decides to select a more expensive service, the out of pocket payment will be larger.

To guarantee minimum quality standards in the delivery of social services regardless of the service provider, Lithuania introduced a quality assurance system for social services in 2007 (Radišauskienė and Žalimienė, 2009[11]). Accordingly, social services are required to be provided in compliance with a set of social care standards that place a strong focus on the principles of privacy, dignity and honour, as well as on the consideration of emotional needs, the encouragement of self-expression and the strengthening of social ties with the community, among others.

4.2.6. Funding

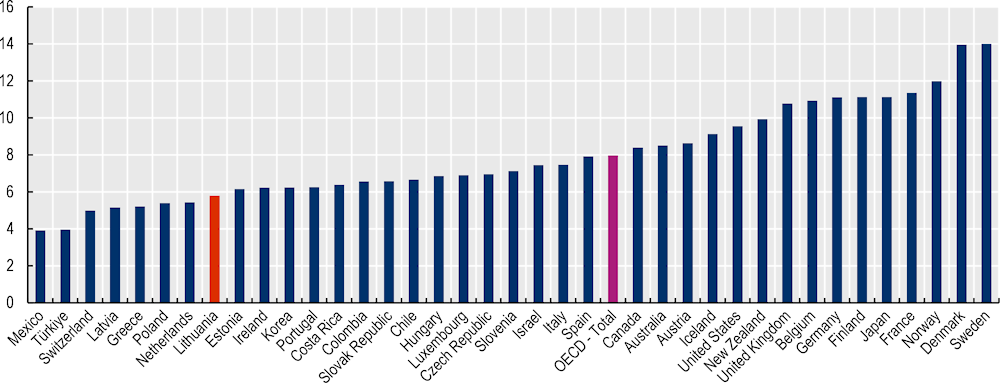

Lithuania devotes comparatively few resources to the delivery of social services. Public social expenditure for in-kind services amounted to about 5.8% of GDP in 2017, compared to the OECD average of 8.0% (Figure 4.5).

Figure 4.5. Public social expenditure for in-kind services

Note: Social expenditure on in-kind services refers to the direct in-kind provision of social goods and services. To be considered “social”, programmes have to involve either redistribution of resources across households or compulsory participation. Social expenditure is classified as public when general government (central, state, and local governments, including social security funds) controls the relevant financial flows. Data refer to 2017 for Australia, Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Türkiye and the United Kingdom; 2018 for Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, France, Hungary, Korea, New Zealand, Switzerland and the United States; and 2019 for Chile, Israel and Mexico.

Source: OECD Social Expenditure Database.

Since the approval of the Law on Social Services in 2006, the financing scheme of social services in Lithuania changed from the direct financing of institutions to the direct financing of social services (Radišauskienė and Žalimienė, 2009[11]). Financing of social services in Lithuania is now a shared responsibility of the municipalities, the central government, and the beneficiary. In particular, social care for the elderly, the disabled (except for people with severe disability) and those at risk of social exclusion is financed from the municipal budget. Social care for severely disabled people and social care services for families are financed through the targeted subsidies from the state budget to municipal budgets. The amount to be paid for social services by the beneficiary ranges from 20% to 80% of the price of the service. The exact percentage is established taking into consideration the type of the service to be provided, as well as the financial capability of the person or family (in terms of income and property).

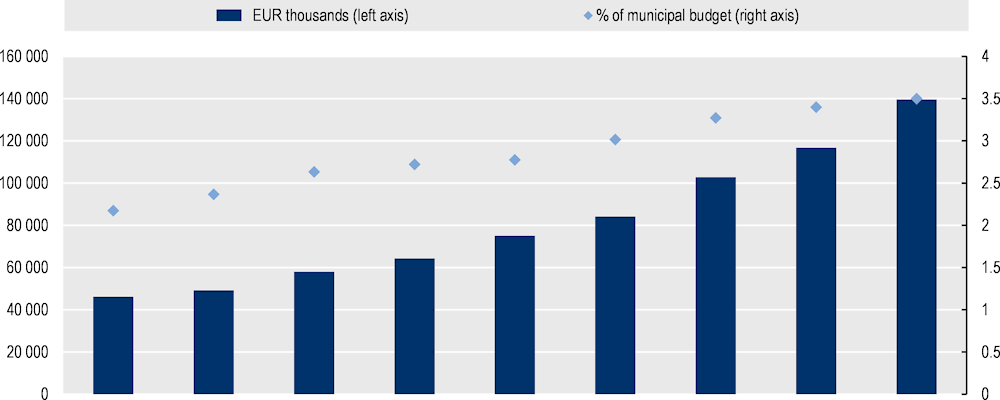

Although the share of municipal budget allocated to the provision of social services has modestly increased in the past decade, only 3.5% of the total municipal budget was devoted to social services in 2020 (Figure 4.6). This figure hides, however, certain cross-municipality variation: the largest share of budget devoted to social services was 5.9% in Kelme District, while the lowest share only reached 1.1% in Druskininkai.

Figure 4.6. Municipal budget allocated to the provision of social services

Source: Data provided by the Ministry of Social Security and Labour.

Municipalities consider that funding for social services is overall limited, which directly affects the planning and implementation of social services in their territory. Consequently, prioritisation of certain social services is always necessary at the planning stage, and it has been demonstrated that some municipalities do not have the capacity to arrange certain necessary services in their municipalities, or the ones provided are of lower quality than desired (Radišauskienė and Žalimienė, 2009[11]). To tackle this issue, municipalities often apply for additional funding sources such as European Structural Funds or special nationally budgeted programmes.

According to the OECD’s municipality survey, 50 municipalities received funding from European Structural Funds in 2020, for an approximate total amount of EUR 16 600 000. An example of a project co-funded by state grants and European Structural Funds is the project “From Care to Opportunities: Development of Community-Based Services”, which is being implemented by the Department of Disability Affairs since April 2020 for an expected duration of three years. The project is aligned with the Action Plan 2014‑23 for the transition from institutional care (Box 4.2), and its core objective is to create a system of complex community services that will allow every person with disabilities and their families, as well as every child left without parental care, to receive all necessary assistance in a safe and development-friendly environment.

In addition to state targeted grants and European Structural Funds, around a third of municipalities mention receiving funding from alternative sources. The total amount of funds from these sources reached approximately EUR 4 300 000 in 2020. For example, the aforementioned project “Development of Quality Based Lithuanian Correctional Service System” is being co-funded by the Norwegian Financial Mechanism 2014‑21.

4.3. Other public services and programmes

4.3.1. Education services

In Lithuania, Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) and general education services are mostly delivered through public schools under the control of Lithuanian municipalities, which follow the guidance and policy framework established by the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport. Private sector education providers are also recognised and regulated by national legislation, but its presence within the education system is almost negligible. In the 2020‑21 school year there were just 75 private schools providing general education services in Lithuania, compared to 977 public schools (Statistics Lithuania, 2022[10]).

ECEC and general education services are mainly publicly funded by state and municipal budgets (Eurydice, 2022[12]). Prior to 2018, the financing system was based on a per-capita model (“pupil basket”), whereby the central government allocated “pupil basket” funds to municipalities as targeted grants. Each year, the central government established the basic education allocations per pupil, and the total amount of funds per school was dependent on the number of pupils enrolled in the school. In 2018, however, this financing principle was replaced by a mixed “class basket” model. Through this system, funds for the implementation of the general education curriculum are calculated per class group instead than the number of pupils. These funds mainly consist of teachers’ salaries and represent around 80% of the “class basket” to schools. In addition, a small percentage of funds is calculated for the provision of textbooks and other education supplies according to the actual number of pupils. The state allocates these amounts as a targeted subsidy for schools. The less than 20% of the “class basket” funds are allocated by municipalities for the organisation and management of the education process, the provision of education aid, and the assessment of learning achievements, among others. This new funding principle aims to encourage city schools to avoid overcrowded classes and give smaller schools financial stability.

ECEC is divided into two phases: the first part is non-obligatory pre‑school education (until the year the child turns 6), while the second part consists of a compulsory year of pre‑primary education. Attendance to primary and lower secondary education (up to the age of 16) is also compulsory. Access to all compulsory education services is universal, and although upper secondary education is not compulsory, its access is guaranteed by the state as well.

The Lithuanian state also guarantees access to Vocational Education and Training (VET) programmes that result in the acquisition of an initial qualification. VET programmes can be undertaken at vocational schools and other VET providers, such as companies or general education schools that have been licensed for that purpose by the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport. Although the offer of VET studies is more varied in larger urban areas, nowadays it is possible to access VET programmes in every municipality. Unlike general education, VET and higher education institutions are funded by the state on the principle of the “pupil basket”, whereby the central government provides the institution with a fixed state subsidy that is calculated according to the number of pupils at the beginning of the school year.

Although the early school leaving rate in Lithuania remains one of the lowest in the European Union (5.6% compared to the EU average of 9.9% in 2020), the incidence of school dropout is larger among certain population groups (European Comission, 2021[13]). In 2011, for example, the proportion of early school leavers among pupils with disabilities was more than 10 percentage points higher than for pupils without disabilities. In order to tackle early school leaving rates, Lithuania has developed early warning systems that identify and respond to emerging signs of early leaving. Students who, over the period of a month miss more than half of the lessons prescribed by the compulsory curriculum are registered in the “National Information System on Children’s Absenteeism and Pupils’ Truancy”. This data is subsequently transmitted to the information systems of other institutions providing social and healthcare services in the country. Most VET providers have also developed their own student attendance tracking systems and action plans to improve attendance, and many have established child welfare commissions to work with potential dropouts, their families, and their teachers to tackle early leaving. Other relevant measures to prevent early school leaving are youth homes for students aged 12 to 17 who have completed a course of treatment for and rehabilitation from dependence on psychotropic substances and alcohol, as well as for those who have behaviour and emotional development challenges and need to improve their mental well-being and motivation for learning.

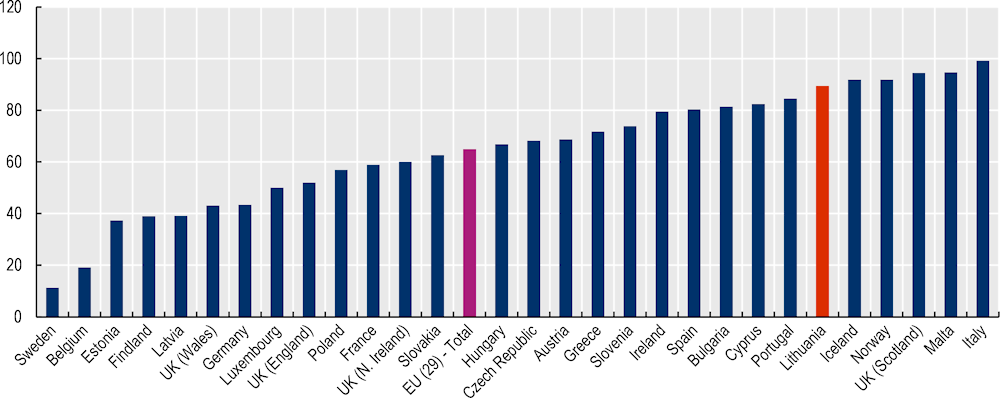

According to the Law No I‑1489 on Education, pupils with special education needs (SEN) can complete their compulsory education in general education schools or in separate special education schools for SEN pupils. For the former option, general schools must however undertake a series of adaptations in terms of facilities, curriculum, teacher training, and additional support for the integration (partial or full) of SEN pupils. This need for adaptation means that a proportion of SEN pupils completes their general education in special schools. According to the European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2018[14]), around 89% of pupils with SEN enrolled in primary and lower secondary education attended inclusive education settings in Lithuania in 2018, compared to the EU average of 65% (Figure 4.7).

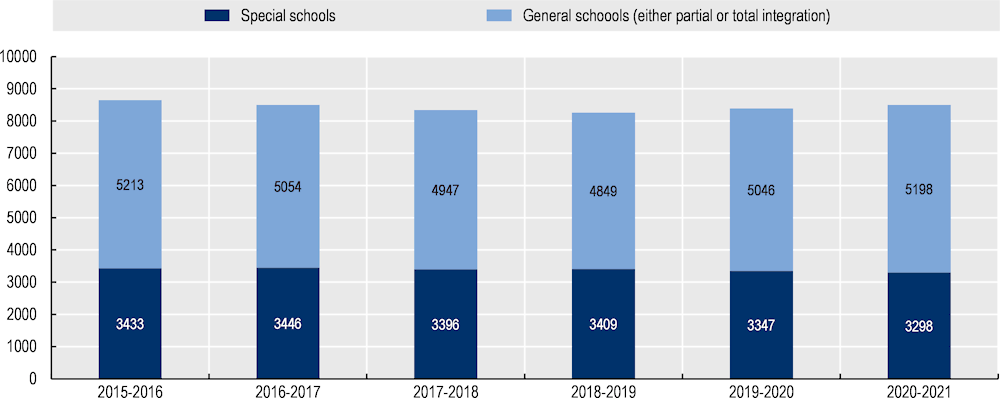

It is important to highlight however, that this proportion presents considerable variation across the different categories of special education needs.5 In fact, at the start of the 2020‑21 school year, around 40% of pupils with disabilities were enrolled in one of the 43 special schools that exist in the country, rather than inclusive education settings (Figure 4.8). This proportion has remained almost constant in the past six school years, and it raises concerns about the full integration of pupils with SEN into society and potential inequalities in their access to quality schooling.

In order to improve the integration of pupils with disabilities into society, an amendment was introduced in the Law on Education in 2020 with the objective to gradually increase the inclusion of children with SEN in the general education system by September 2024. The aim is to keep special schools only for the most severe cases. Like general education services, VET for SEN students can be delivered according to individual learning plans at general VET institutions or at specialised VET institutions for SEN pupils. In 2019, there were approximately 1 300 pupils with disabilities enrolled in an initial VET programme (Cedefop, 2018[15]).

Figure 4.7. Access to general education services for pupils with special education needs

Source: European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2018[14]), 2018 Dataset Cross-Country Report, https://www.european-agency.org/activities/data/cross-country-reports.

Figure 4.8. Access to general education services for pupils with disabilities

Source: Lithuania Education Management Information System (ŠVIS) (2021[16]), General education statistics, http://svis.emokykla.lt/bendrasis-ugdymas‑2/.

Although no separate general education services are exclusively targeted to young care leavers, access to general education services is guaranteed for all Lithuanian adults who have not completed their education. These education programmes can be accessed through one of the 14 adult general education schools available in the country, or at general education schools that offer special classes for adults. These types of services provide a further opportunity for adult people to complete their general education and develop their general competences, which promotes their resilience and other positive outcomes, especially in the case of the most vulnerable groups. For example, an analysis of data from the Swedish national register showed that in comparison with young people in the general population, care leavers who did poorly at school had a 6‑ to 11‑fold risk for suicide attempts, substance abuse and criminality from age 20 and a 10‑fold excess risk for welfare dependency at age 25 (Berlin, Vinnerljung and Hjern, 2011[17]). For young care leavers, who can often be at greater risk of social isolation, school can also provide opportunities to make friends, find natural mentors and build long-lasting social networks (Gilligan and Arnau-Sabatés, 2017[18]).

In the case of prisoners, the provision of general education and VET services is regulated in the Procedure for the Organisation of General Education and Vocational Training of the Detained and Convicted, which was approved in 2016. According to the ruling, the general education of prisoners under the age of 16 must be guaranteed under all circumstances. In the case of prisoners over 16 years of age who wish to attend school, a written request and official approval is necessary.

4.3.2. Employment services

The Lithuanian PES is responsible for the delivery of active labour market policies (ALMPs) in Lithuania. A comprehensive list of the existing ALMPs is defined in the national Law No XII‑2470 on Employment. There is at least one local PES office in each municipality, and all of them have the same catalogue of services.

ALMPs can be divided into two categories: labour market services (or ALMP services) and employment support services (or ALMP measures). The former category is regulated in section four of the Law on Employment, and it includes the registration of job opportunities and job seekers, information and counselling services, individual assessment of employment opportunities and planning of activities, and employment mediation services. ALMP measures, on the other hand, refer to programmes for the promotion of employment. ALMP measures are regulated on section six of the Law on Employment and described in more detail in Box 4.3.

Since 2019, the Law on Employment includes a list of vulnerable groups of people who are entitled to receiving additional support services for their integration in the labour market. These targeted groups include, among others, disabled people of working age, unemployed persons without any professional qualification, long-term unemployed people under 25 years of age, unemployed people under 29 years of age, and unemployed people older than 50 years of age. As such, people of working age with assessed disabilities that limit their capacity to work and unemployed youth are giving priority to benefit from certain unemployment services, but as of today, no dedicated programmes or measures exist for people leaving prison and young people leaving care.

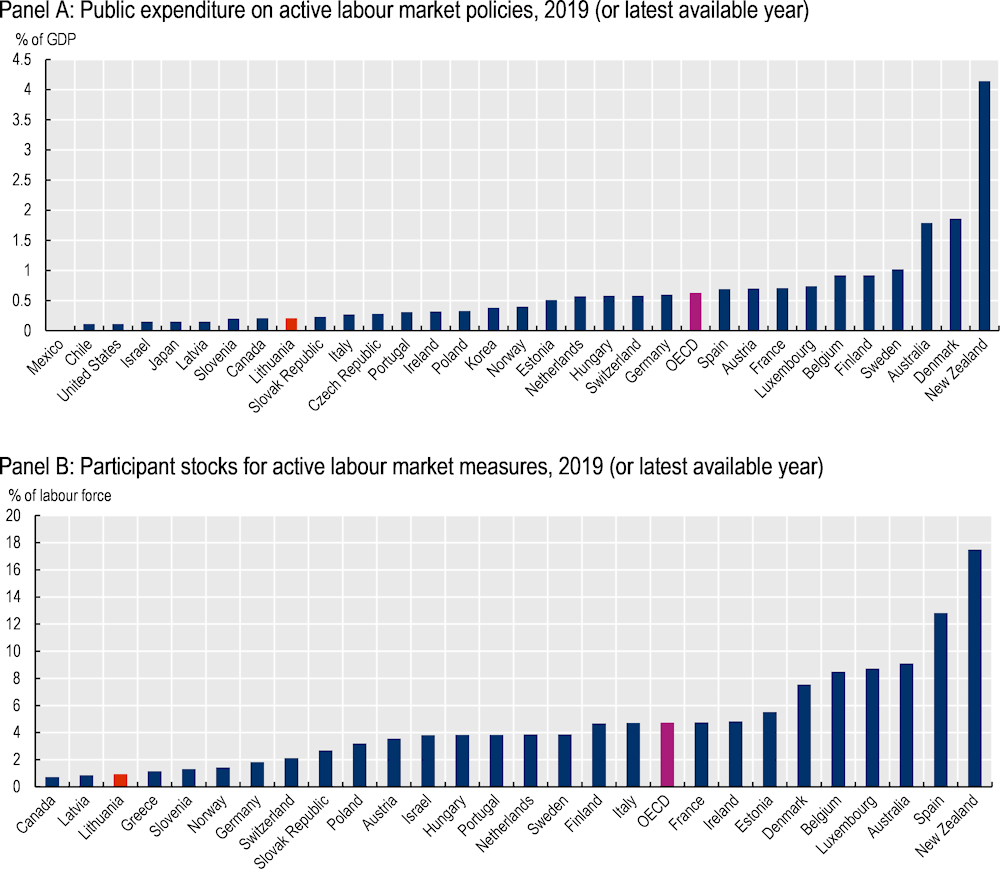

The Law on Employment implemented since 2017 aims to make ALMPs more accessible and meet the labour market needs better, particularly by strengthening and modernising training programmes for jobseekers. However, according to the OECD report evaluating ALMPs in Lithuania (OECD, forthcoming[19]), the coverage of ALMPs has remained low and focused on employment incentives, with the exception of significant additional allocations for the employment maintenance scheme during the COVID‑19 crisis. The employment incentives supporting labour market integration of vulnerable groups more generally have been evaluated to have positive impact on the labour market outcomes of the participants. However, the rather well-funded scheme targeting people with disabilities via employment in social enterprises has not been recently evaluated and the stakeholders (policy makers and the social partners alike) believe that this scheme does not help the target group sufficiently. In addition, Lithuania allocates only marginal resources for sheltered and supported employment and rehabilitation, which could be essential for the most vulnerable groups, and particularly people with disabilities, to help them integrate into the labour market (OECD, 2021[20]).

In international comparison, Lithuania spent less than half of the average of OECD countries on ALMPs in 2019 (0.21% versus 0.45% of GDP), and the difference in ALMP coverage was even more drastic (1% of labour force participated in ALMPs in Lithuania but 5% in the OECD) (Figure 4.9). Furthermore, the ALMPs in Lithuania are mostly financed via the European Social Fund resources, which is not necessarily ensuring sufficient flexibility to meet the changing labour market needs and is not sustainable in the long term (OECD, forthcoming[19]).

Box 4.3. Active Labour Market Policy measures

Active labour market policy measures are aimed at assisting job seekers in increasing their employment opportunities and achieving the balance between labour supply and demand, and include learning support, mobility support, supported employment, and support for job creation.

Learning support services are provided to help unemployed people restore, acquire, or improve their qualifications and skills. Learning support includes vocational training, apprenticeships, and other forms of advanced training.

Since 2012, the PES has funded vocational training for all unemployed people (and since 2017 for certain employed people) through a voucher system that allows jobseekers access training at vocational education and training (VET) providers approved the Ministry of Social Security and Labour. After the completion of the training programme, the unemployed person undertakes to work in the position offered by the either the local PES or the employer for at least six months, or start their own business (Cedefop, 2018[15]).

Furthermore, employment under an apprenticeship employment contract may be organised for those who take part in vocational training. In such cases, the new Employment Law approved in 2017 stipulates that the employer is responsible for ensuring that the apprentice acquires the learning outcomes defined in the VET programme. Employers are compensated 40% of the pay specified in the contract.

Support for local mobility commuting is provided to registered unemployed people who found a job in geographical areas other than their current place of residence, as well as to those who incur in travel expenses for their participation in counselling sessions organised by the PES.

Supported employment measures include subsidised employment and support for the acquisition of work skills. Subsidised employment consists of wage subsidies paid to employers hiring certain groups of people registered in the PES. These targeted groups include, among others, disabled people of working age, unemployed persons without any professional qualification, long-term unemployed people under 25 years of age, unemployed people under 29 years of age, and unemployed people older than 50 years of age. Similarly, support for the acquisition of work skills consists of wage subsidies paid to employees hiring people who are taking part or have completed vocational training, or unemployed individuals who start working on a job related to their acquired qualification for the first time. The length of the support can be extended up to 12 months.

Measures to incentivise job creation include subsidising the creation or adaptation of jobs for people with disabilities, assisting with the implementation of local employment initiative projects, and subsidising self-employment initiatives led by those preferential groups also targeted by supported employment measures.

Figure 4.9. Public expenditure and participants stock for active labour market policies

Note: OECD average is an unweighted average. Panel A includes the following services and measures: Public Employment Services and administration, training, employment incentives, sheltered and supported employment and rehabilitation, direct job creation, and start-up incentives. Panel B, on the other hand, does not include Public Employment Services and administration.

Source: OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics database, https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00312-en.

4.3.3. Healthcare services

In the late 1990s, Lithuania moved away from a health system mainly funded through state and local budgets to one funded by the National Health Insurance Fund (OECD, 2018[21])Through this system, employed residents must pay a compulsory health insurance contribution, while the state is responsible for covering the contributions of other groups, resulting in a universal coverage system. It is estimated that the other groups account for about 60% of the Lithuanian population and include children, the elderly, people with disabilities, women on pregnancy and maternity leave, individuals registered with public employment services, and other individuals receiving social assistance.

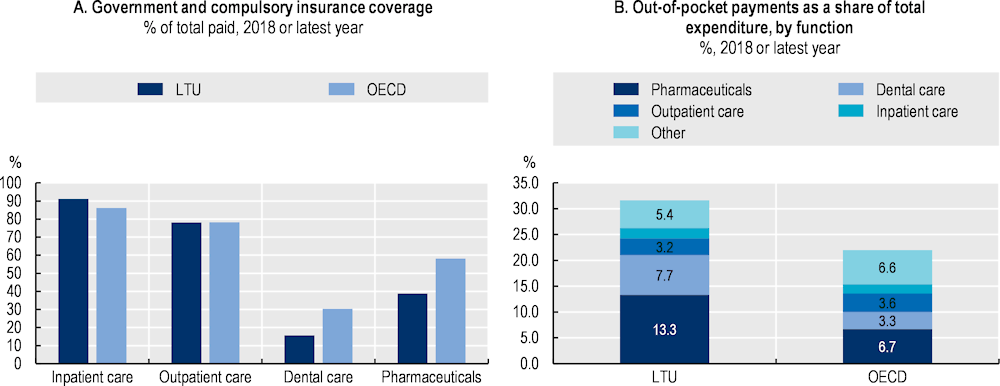

The compulsory health insurance is a guarantee for all insured that, when needed, their healthcare expenses will be compensated from the budget of the National Health Insurance Fund, irrespective of the contributions paid by the specific insured individual. Compulsory health insurance provides a standard benefits package for all beneficiaries. As a result, access to healthcare services is widely universal and compares well with the OECD average in terms of coverage for outpatient and inpatient care (Figure 4.10, Panel A).

Figure 4.10. Access to healthcare services

Source: OECD Health Statistics database; and EU-SILC.

Despite the large coverage for inpatient and outpatient care, the coverage for dental care and pharmaceuticals is relatively low: 16% and 39% of the population, respectively. The lower public coverage of dental care and pharmaceuticals translates into a comparatively larger share of healthcare costs being born by patients. Indeed, out-of-pocket payments represented around a third of health spending in Lithuania in 2018, well above the OECD average (Figure 4.10, Panel B). This high level of out-of-pocket disbursements are likely to disproportionately affect the most vulnerable groups and lead to significant inequalities in access to healthcare services, and therefore, in health outcomes.

Reforms have been introduced in the past years to improve the availability and accessibility of healthcare services for the most vulnerable groups. Since July 2020, those aged 75 and over, low-income pensioners, and people with disabilities are exempted from co-payments for pharmaceutical and medical expenses. Furthermore, children, pensioners and people with disabilities are also granted access to free dental services. The Lithuania Health Programme 2014‑25 also refers to the development of a monitoring system of health inequalities aimed to target at-risk population and promote an integrated health policy approach involving health, education, and social institutions. The programme describes specific actions targeted at municipalities with the highest rate of premature mortality and population at-risk, and since 2014, public healthcare activities have been promoted in pre‑school education, general education, and VET programmes.

Primary-level (outpatient) healthcare services for prisoners are provided in penitentiary institutions by healthcare professionals employed there. Secondary-level healthcare services are provided at the Central Prison Hospital or at public healthcare centres, while tertiary-level services are exclusively accessible at public healthcare centres. Although primary healthcare services are available in all penitentiary institutions in the country, inmates tend to suffer from substandard healthcare provision. Indeed, a visit to Lithuanian prisons undertaken by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment in 2018 demonstrated that healthcare teams in most Lithuanian prisons were understaffed (Council of Europe, 2019[22]). This situation impeded to ensure optimum healthcare for prisoners, and to observe the general principle of the equivalence of healthcare in prison with that in the wider community. The visit also confirmed that prisoners were at high risk of becoming drug dependent and contracting HIV and hepatitis C while in prison, due to the widespread presence of drugs in the facilities and the common practice of sharing injecting equipment.

This lower quality of healthcare in penitentiary institutions is problematic, as it deteriorates the health of the inmates (Brinkley-Rubinstein, 2013[23]; Massoglia, 2008[24]) and makes them more likely to have worse socio‑economic outcomes (Dyb, 2009[25]; Western, Kling and Weiman, 2001[26]) as well as health outcomes (Cutcher et al., 2014[27]; Kinner, 2006[28]) when they return to the community. Regarding the latter, research shows that the incidences of substance dependence, mental illness, and communicable disease, including sexually transmitted infections, hepatitis, and HIV, are particularly high among people leaving prison, making it essential to facilitate their access to healthcare services after their release (Thomas et al., 2015[29]).

4.4. Conclusion

The provision of social services in Lithuania relies heavily on the Catalogue of social services, which sets out a list of services that can be provided in the country and clearly defines what each service must consist of, who can get access to it, and under which conditions. Theoretically, the Catalogue is comprehensive although not exhaustive, and Lithuanian municipalities are free to decide on the provision of additional services outside of the Catalogue. In practice, however, this is not common practice and municipalities do not often deviate from the pre‑existing list of services. This practice can be problematic because the list of social services enumerated in the Catalogue has hardly changed since it was approved in 2006, which could trigger gaps in service provision when new societal needs arise.

In line with the Catalogue, Lithuanian municipalities can provide both “general” social services, as well as “special” services to those vulnerable individuals and families who present needs that are more acute. Special services can be further disaggregated into social assistance and care services. Overall, the availability of social services is highly polarised across Lithuanian municipalities. For example, while almost one‑third of municipalities offer all general social services included in the Catalogue, most of the remaining municipalities offer less than half of the general services listed there. Similarly, only 23% of municipalities offer all social assistance services available in the Catalogue.

Each of the social services described in the Catalogue is linked to a list of vulnerable groups who are entitled to benefit from that service. While children and adults with disabilities have always been clearly defined as specific target groups for most social services in the Catalogue, young care leavers and people leaving prison did not constitute specific target groups per se. Instead, they could, depending on the evaluation by the social worker, fall under the beneficiary categories of “individuals and families at social risk” or “young people with fewer opportunities”. Since November 2021, however, a new “leaving care” service was included in the Catalogue, and young care leavers are clearly defined as a beneficiary group for this service. The “leaving care” service consists of a set of interrelated measures provided to help young people leaving care settings in adapting to their social environment and in developing their social skills and ability to deal with potential challenges.

Statistics on the number of recipients of social services is spread across different sources, with the two most important ones being the public reports generated by the reporting tool of the Social Protection Information System (commonly known as the SPIS showcases) and the national survey of social services. Available statistics on the number of social service users is, however, neither comprehensive nor accurate, which can hinder the planning and implementation of social services in the country. Furthermore, municipalities do not have detailed and up to date information on the total population who meet the criteria to benefit from certain social services but are not currently making use of them (i.e. target population). This discrepancy means that many decisions on the development of social services are made without information on the real needs for social services, which can lead to exclusion errors in the targeting process.

According to the Law on Social Services, both private and public institutions can provide social services in Lithuania, and individuals can choose freely among all accredited or licensed service providers. Nevertheless, a free market of social services providers is not yet the reality, and state and municipal institutions are the predominant providers of social services in the country. Furthermore, prices for social services are not officially regulated, which makes self-payment of social services a key determinant on the individual’s choice of service provider.

Financing of social services in Lithuania is a shared responsibility of the municipalities, the central government, and the beneficiary. Although the share of municipal budget allocated to the provision of social services has modestly increased in the past decade, only 3.5% of the total municipal budget was devoted to social services in 2020. Municipalities consider that funding for social services is overall limited, which directly affects the planning and implementation of social services in their territory. To tackle this issue, municipalities often apply for additional funding sources such as European Structural Funds or special nationally budgeted programmes.

In addition to social services, vulnerable groups in Lithuania can also benefit from other forms of public support, including education, employment, and health services.

With respect to education, the Lithuanian state guarantees universal access to all compulsory education services, as well as upper secondary and Vocational Education and Training programmes that result in the acquisition of an initial qualification. Pupils with disabilities can complete general education and VET studies in mainstream schools or in separate special education schools, although an amendment was introduced in the Law on Education in 2020 to promote the inclusion of children with special education needs in the general education system by September 2024. Although no separate education services are exclusively targeted to young care leavers, access to general education services is guaranteed for all Lithuanian adults who have not completed their education. General education of prisoners under the age of 16 is also guaranteed under all circumstances.

The Lithuanian Public Employment Service is responsible for the delivery of active labour market policies in the country. There is at least one local office in each municipality, and all of them have the same catalogue of services, regulated by the Law of Employment. Since 2019, this law includes a list of vulnerable groups of people who are entitled to receiving additional support services for their integration in the labour market. These targeted groups include, among others, disabled people of working age, unemployed persons without any professional qualification, long-term unemployed people under 25 years of age, unemployed people under 29 years of age, and unemployed people older than 50 years of age. As of today, no dedicated programmes or measures exist for people leaving prison and young people leaving care.

Finally, access to healthcare services in Lithuania is widely universal and compares well with the OECD average in terms of coverage for outpatient and inpatient care. Nevertheless, the coverage for pharmaceuticals and dental care is still relatively low and translates into a comparatively larger share of healthcare costs being born by patients. In order to improve the availability and accessibility of healthcare services for the most vulnerable groups, a series of reforms have been introduced in the past years. Since July 2020, those aged 75 and over, low-income pensioners, and people with disabilities are exempted from co-payments for pharmaceutical and medical expenses. Furthermore, children, pensioners and people with disabilities are also granted access to free dental services. Although primary healthcare services are available in all penitentiary institutions in the country, inmates tend to suffer from substandard healthcare provision.

Recommendations for improving social service design

Elaborate a detailed methodology and related guidance that municipalities can use to systematically assess the need for social services in their territories.

Conduct consultations with key stakeholders across the national government, municipalities, NGOs and service users to better understand the evolving needs of target groups, and to obtain a comprehensive and realistic assessment of the population needs in their territories.

Systematically collect individual and household level data on social service users to monitor not only the number of users of different services but also other relevant information such as the intensity/frequency of usage and the demographic and socio‑economic characteristics of the user.

Undertake/commission new research projects to obtain information on the size of the target population for different social services, that is, people who meet the criteria to benefit from those services but are not currently making use of them, to assess whether more and/or new services are required.

Regularly revisit the Catalogue of Social Services to improve existing services and include new ones if considered necessary.

References

[17] Berlin, M., B. Vinnerljung and A. Hjern (2011), “School performance in primary school and psychosocial problems in young adulthood among care leavers from long term foster care”, Children and Youth Services Review, Vol. 33/12, pp. 2489-2497, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHILDYOUTH.2011.08.024.

[23] Brinkley-Rubinstein, L. (2013), “Incarceration as a catalyst for worsening health”, Health & Justice 2013 1:1, Vol. 1/1, pp. 1-17, https://doi.org/10.1186/2194-7899-1-3.

[15] Cedefop (2018), Vocational education and training in Europe: Lithuania. Cedefop ReferNet VET in Europe reports 2018., http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/EN/Information-services/vet-in-europe-country-.

[22] Council of Europe (2019), Report to the Lithuanian Government on the visit to Lithuania carried out by the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CPT), https://rm.coe.int/168095212f (accessed on 10 March 2022).

[2] Council of Europe (2017), T-KIT 8: Social inclusion, http://eplusifjusag.hu/public/files/social_press/-t-kit_8_social_inclusion_web.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2022).

[27] Cutcher, Z. et al. (2014), “Poor health and social outcomes for ex-prisoners with a history of mental disorder: a longitudinal study”, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, Vol. 38/5, pp. 424-429, https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12207.

[3] Department of Disability Affairs (2022), Implementation of projects, https://www.ndt.lt/finansavimo-konkursai/socialines-reabilitacijos-paslaugu-remimas/projektu-igyvendinimas/ (accessed on 18 March 2022).

[4] Department of Disability Affairs (2021), Implementation of personal assistance in the municipalities in 2021.

[25] Dyb, E. (2009), “Imprisonment: A Major Gateway to Homelessness”, https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030903203676, Vol. 24/6, pp. 809-824, https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030903203676.

[14] European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2018), 2018 Dataset Cross-Country Report, https://www.european-agency.org/activities/data/cross-country-reports (accessed on 23 March 2022).

[13] European Comission (2021), European Semester 2020-2021 - Country Fiche on Disability Equality Lithuania, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/policies/european-semester/how-european-semester-works/.

[1] European Comission (2019), Youth policies in Lithuania - 2019, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/en/youthwiki.

[12] Eurydice (2022), Key features of the Lithuanian education system, https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/lithuania_en (accessed on 26 February 2022).

[18] Gilligan, R. and L. Arnau-Sabatés (2017), “The role of carers in supporting the progress of care leavers in the world of work”, Child & Family Social Work, Vol. 22/2, pp. 792-800, https://doi.org/10.1111/CFS.12297.

[5] Globa Šeima Bendruomenė (2022), Institutional care restructuring, https://pertvarka.lt/ (accessed on 16 March 2022).

[28] Kinner, S. (2006), “Continuity of health impairment and substance misuse among adult prisoners in Queensland, Australia”, International Journal of Prisoner Health, Vol. 2/2, pp. 101-113, https://doi.org/10.1080/17449200600935711/FULL/PDF.

[7] LIL (2018), Investigation on the Implementation and Application of Social Rehabilitation in Lithuanian Correctional Facilities, https://teise.org/en/kodel-nuteistuju-socialine-reabilitacija-ne-visada-sekminga/ (accessed on 18 March 2022).

[16] Lithuania Education Management Information System (2021), General education statistics, http://svis.emokykla.lt/bendrasis-ugdymas-2/ (accessed on 26 February 2022).

[24] Massoglia, M. (2008), “Incarceration as exposure: The prison, infectious disease, and other stress-related illnesses”, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 49/1, pp. 56-71, https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650804900105.

[9] National Audit Office of Lithuania (2020), Social Integration of Persons with Disabilities. Summary, https://www.eurosai.org/en/databases/audits/Social-Integration-of-Persons-with-Disabilities/ (accessed on 8 March 2022).

[20] OECD (2021), “Building inclusive labour markets: Active labour market policies for the most vulnerable groups”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/607662d9-en.

[21] OECD (2018), OECD Economic Surveys: Lithuania 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-ltu-2018-en.

[19] OECD (forthcoming), Impact evaluation of vocational training and employment subsidies in Lithuania. Connecting people with jobs., OECD Publishing, Paris.

[6] Opening Doors (2018), Lithuania, https://www.openingdoors.eu/where-the-campaign-operates/lithuania/ (accessed on 22 March 2022).

[8] Prison Department (2022), The Project “Development of Quality Based Lithuanian Correctional Service System“, http://www.kaldep.lt/en/prison-department/projects/ongoing-projects.html (accessed on 18 March 2022).

[11] Radišauskienė, E. and L. Žalimienė (2009), Peer Review: Combining choice, quality and equity in social services. Social services in Lithuania, https://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=1024&langId=en&newsId=1403&moreDocuments=yes&tableName=news (accessed on 28 February 2022).

[10] Statistics Lithuania (2022), Database of indicators, https://osp.stat.gov.lt/statistiniu-rodikliu-analize#/ (accessed on 26 February 2022).

[29] Thomas, E. et al. (2015), “Health-related factors predict return to custody in a large cohort of ex-prisoners: new approaches to predicting re-incarceration”, Health & Justice 2015 3:1, Vol. 3/1, pp. 1-13, https://doi.org/10.1186/S40352-015-0022-6.

[26] Western, B., J. Kling and D. Weiman (2001), “The labor market consequences of incarceration”, Crime & Deliquency, Vol. 47/3, pp. 410-427, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0011128701047003007 (accessed on 10 March 2022).

Notes

← 1. It is important to note here that at the time of writing this report, the Catalogue exclusively differentiated between “general” and “special” social services. In June 2022, a new category of “preventive” social services was included in the Catalogue. These types of social services entered into force on 1 July 2022, and are thus not covered in this report.

← 4. According to the Law on Public Establishments, a public institution is a public legal entity with limited liability, the aim of which is to satisfy public interests by implementing educational, environmental, cultural, social or legal assistance activities, as well as other activities that are beneficial to society. Stakeholders of a public institution can be natural and legal persons, the state, municipalities, and other entities that do not seek benefit to obtain benefit from the activities of the institution.

← 5. Pupils with SEN are divided into three separate groups: i) pupils with disabilities (mental, vision, hearing, cochlear implants, motion and positional, neurological, varied developmental disorders, deaf, and complex and other disabilities); ii) pupils with difficulties (learning disorders, behavioural and/or emotional, impaired speech and language, and complex and other disorders); and iii) pupils with disadvantages in learning (e.g. learning a second language or living in another cultural/linguistic environment, suffering from the adverse effects of environmental factors or experiencing emotional).