This chapter reviews the mix of policies that is in place to foster FDI-SME linkages across the 27 EU Member States. It presents the national policy frameworks that support FDI-SME diffusion channels and enabling conditions, and the policy instruments used to strengthen productivity spillovers from foreign investors to domestic SMEs. It also examines various aspects of policy making, such as targeting towards different types of firms, sectors, value chains or regions, and coordination and monitoring.

Policy Toolkit for Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages

5. The policy mix for strengthening FDI-SME linkages and spillovers

Abstract

Introduction

Box 5.1. Mapping the FDI-SME policy mix across the EU: methodological limitations

A first challenge in policy mapping is to define the scope under analysis and identify the relevant initiatives and components in the policy mix. How the exercise is designed can determine the strategic orientations of the mix, its instrumentalisation, its governance, and shifts over time (Meissner and Kergroach, 2019[1]). Potential distortions are higher when the number of measures identified are small. In addition, the number of initiatives in place can be highly variable across countries, depending on the size of the country and the capacity of its public administration, the intensity of the policy interest given, or the maturity of the policy field and the likelihood of initiatives having piled up over time (OECD, 2022[2]). In practical terms, EU totals, as the sum of all EU countries’ initiatives, could give a disproportionate weight to the countries with the more “prolix” (Guy et al., 2009[3]) or dense (Meissner and Kergroach, 2019[1]) policy mixes. In other words, countries with a larger number of initiatives (observations) tend to get more weight in aggregate measures. To mitigate this effect, the EU aggregates presented throughout this Chapter are calculated as “average of national averages”.

A second challenge for policy mapping and impact assessment arises from the question of quantifying policy initiatives (Meissner and Kergroach, 2019[1]). A simple counting presents the advantage to be easy to understand – albeit not necessarily easy to implement or to interpret – and the counting could be discriminated by policy area, instrument, target population, sectors etc. Policy initiatives could also be accounted in terms of input (e.g. public budget allocated), output (e.g. new strategic partnerships between foreign affiliates and local SMEs) and outcome (e.g. net job creation). The lack of data at disaggregated level, i.e. at the level of the policy initiative, is a clear limitation in this statistical approach. The number of FDI-SME policy initiatives in place is therefore a partial measure of the intensity of a country’s effort in a given area, and other parameters matter.

Policies for strengthening linkages between foreign direct investment (FDI) and small and medium‑sized enterprises (SMEs), and for improving the scope and quality of productivity and innovation spillovers to local economy, herein referred to as FDI-SME policies, cover public action for attracting and retaining international investment, fostering SME performance and entrepreneurship, promoting innovation and supporting regional development. Public intervention can span across multiple policy domains and take many forms as it addresses deficiencies in different diffusion channels (i.e. value chain linkages, strategic partnerships, labour mobility, and competition effects), different enabling conditions (e.g. FDI characteristics, or the absorptive capacity of local SMEs) and different contexts (e.g. structural, economic and geographical characteristics of the place/region/country) (see Policy mapping methodology for a brief overview on the methodology and Chapter 1 for more detailed elaboration).

This chapter aims to better understand how the FDI-SME policy mix is shaped in the EU area, the intensity of public efforts in different policy areas, what priority is given to different strategic policy objectives and policy instruments, and how targeted or generic country approaches could be. The analysis relies on a pilot mapping of 626 national policies implemented across the 27 EU countries to promote quality FDI, improve SME absorptive capacity and reinforce the linkages and opportunities of spillovers between both (Policy mapping methodology). The mapping was conducted between January and September 2021 through desk research, and information was consolidated through the EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages, an online consultation of the implementing institutions. The pilot mapping will be further developed and consolidated during the second phase of the project (2022‑24), with similar consultation of the national implementing institutions. Box 5.1 recalls the main methodological limitations of the exercise and how they can affect interpretation and results.

Overall orientation of the FDI-SME policy mix in EU countries

The overall orientation of the FDI-SME policy mix in EU countries refers to the broad direction(s) policy action can take and reflect the policy intentions and strategic objectives pursued in the field. They are derived from the rationales for policy intervention (e.g. market, system or governance failures) that emerge in the policy areas under study (i.e. investment, SME and entrepreneurship, innovation and regional development), some diagnostics of the state of the FDI-SME ecosystem and a vision of its future (Meissner and Kergroach, 2019[1]).

All countries have FDI-SME initiatives in place

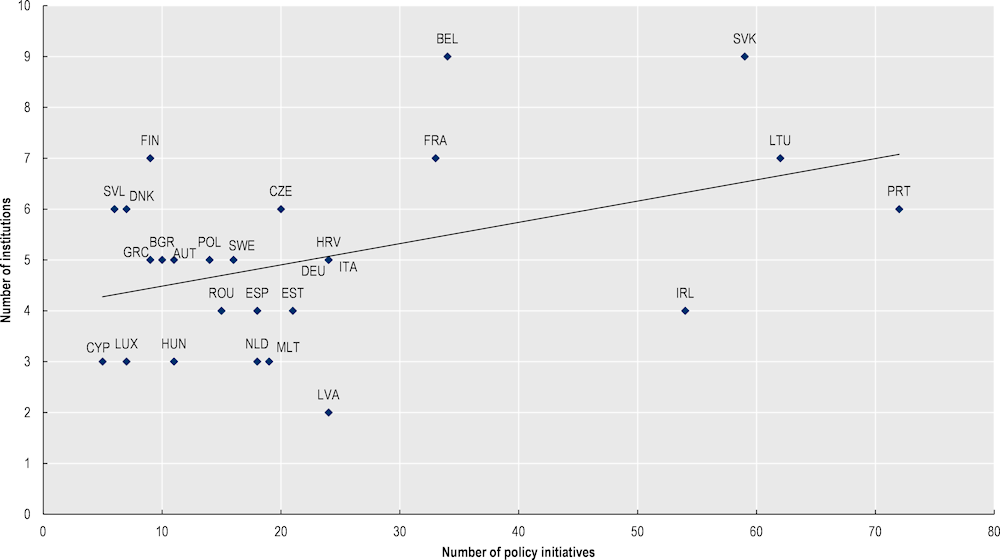

All governments have policy initiatives in place that aim to contribute – directly or indirectly – to enhancing FDI‑SME linkages and spillovers. However, there is considerable cross-country variation in the number of these initiatives. This spreads from less than ten measures in Finland or Greece, to more than six times as many in Lithuania (62) and Portugal (72). Such variation does not seem to be related to the size of the countries (e.g. larger or smaller population, or larger or smaller GDP), while the number of measures appears to increase with the number of institutions involved (Figure 5.1). This finding is in line with those of the EC/OECD project on “Unleashing SME Potential to Scale up”, that was carried out in 2021 with a mapping of the policies for SME access to growth finance (OECD, 2022[2]). By the way, the number of policy initiatives in place is only a partial measure of the intensity of a country’s efforts in a given area – other parameters related to the size, breadth and scope of policies could be considered (e.g. the budget allocated or the number of beneficiaries) (Policy mapping methodology; Box 5.1).

Figure 5.1. The number of FDI-SME policy initiatives in place increases with the number of institutions involved

Note: For countries with few initiatives (observations), interpretation of indicators should be done with caution.

Source: EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021).

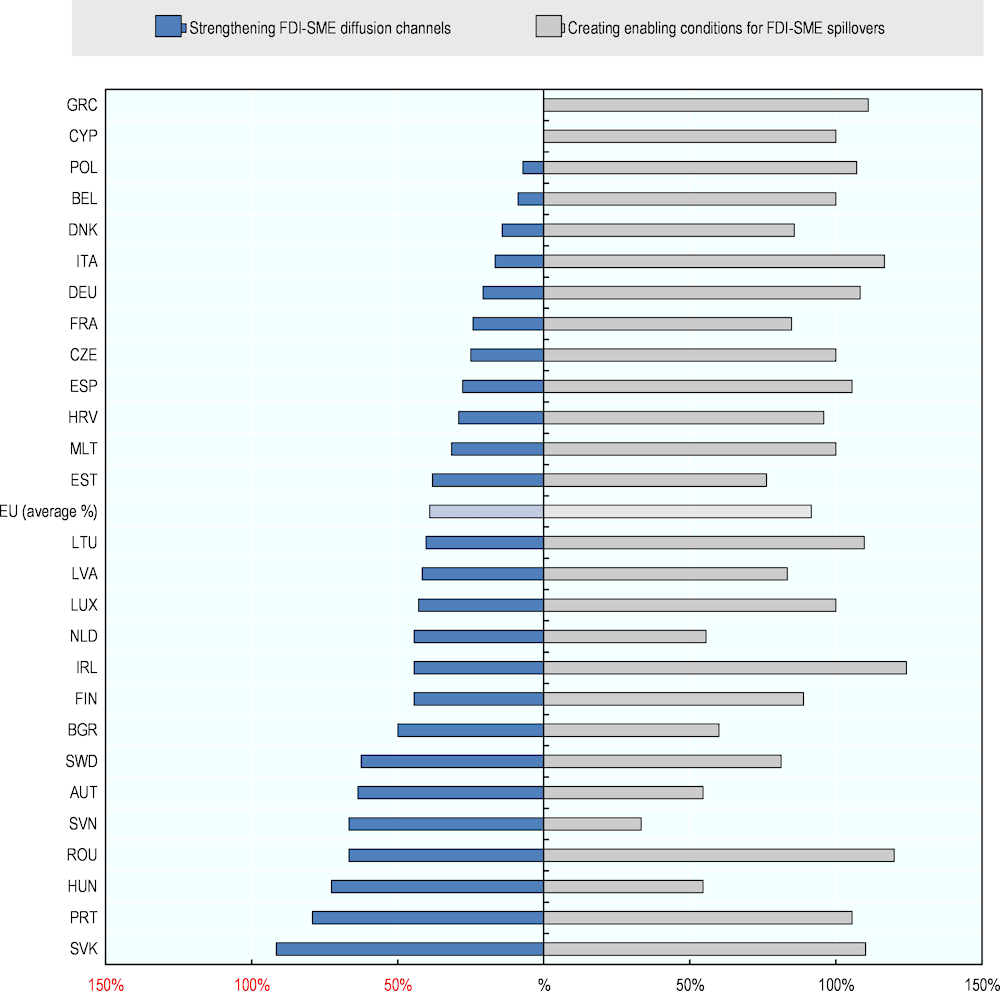

Countries often focus on enabling conditions, especially improving SME absorptive capacity…

Across EU countries, as per the number of measures in place, efforts often focus on enabling conditions for FDI spillovers to domestic SMEs and less on strengthening the diffusion channels themselves (Figure 5.2). More specifically, the FDI-SME policy mix of EU Member States is mainly oriented towards increasing the absorptive capacity of SMEs. On average across the area, 63% of the measures are aimed at improving SME performance, and 17% at attracting productivity‑enhancing FDI or 11% at creating agglomeration economies (Table 5.1).

Policies for enhancing SME performance essentially aim to improve their access to and use of strategic resources, such as finance, skills and innovation assets (OECD, 2019[4]; OECD, 2021[5]). Policies for enhancing the potential impact of international investment on local productivity and innovation aim to attract or retain with potential to create linkages with and spillovers to the host economy, such as greenfield and tech- or innovation-intensive investment. Other enabling conditions are related to economy geography. Regional inequalities may affect FDI-SME linkages and the performance of FDI-SME ecosystems, with reduced attractiveness of less developed places to foreign investors and more constrained capacity of the local businesses to capture innovation spillovers. Policies addressing economic geography factors aim to promote agglomeration and industrial clustering (Chapter 1).

… and less often on strengthening FDI-SME linkages and diffusion channels themselves

When it turns to developing the FDI-SME spillovers channels, 19% of the measures intend to strengthen value chain linkages between SMEs and foreign affiliates (FAs) and 13% to develop strategic partnerships (Table 5.1). Only a small number of measures address the issues of labour mobility and competition (accounting for 3 and 4% of mapped policies each). This analysis does not imply less policy relevance in the areas where less measures are taken, and methodological limitations should be kept in mind in interpretation (Box 5.1). The density of the policy mix could also reflect the multidimensional dynamics at play in creating the framework conditions for FDI-SME spillovers, and the need to address this complexity through a broader range of measures.

Attracting productivity-enhancing FDI has received more attention in Cyprus1 (60%), Denmark (43%), Ireland (41%) and Romania (40%) than in other EU countries (17%). Some countries put also stronger emphasis on the economy geography dimension. In Italy (33%), Poland (29%), Romania (27%), Lithuania (26%), the Czech Republic and the Slovak Republic (25% each) more than twice as many efforts are placed on promoting agglomeration economies and clustering than in the EU on average (11%).

A number of factors can explain these variations, including country-specific characteristics, national industrial structure and specialisation, the degree of regional inequality, and the geographical distribution of business and investment activities across the territory, or the policy strategy for promoting investment, SME and entrepreneurship, innovation and regional development.

Figure 5.2. Countries are more active for enabling a spillovers environment than for strengthening the spillovers diffusion channels themselves

Note: Relative percentage of policy initiatives aiming to create enabling conditions for FDI spillovers to domestic SMEs versus those targeting the diffusion channels of spillovers. Shares are calculated as a % of the total of national initiatives in place, based on an unweighted count. For countries with few initiatives (observations), interpretation of indicators should be done with caution. Shares may be higher than 100% when policy initiatives respond to several policy objectives at the same time. EU (average %): average of the national shares of the 27 EU countries. For a typology and definition of “enabling conditions” and “diffusion channels” of FDI spillovers, please refer to the Policy mapping methodology and Chapter 1 of this report.

Source: Experimental indicators based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021).

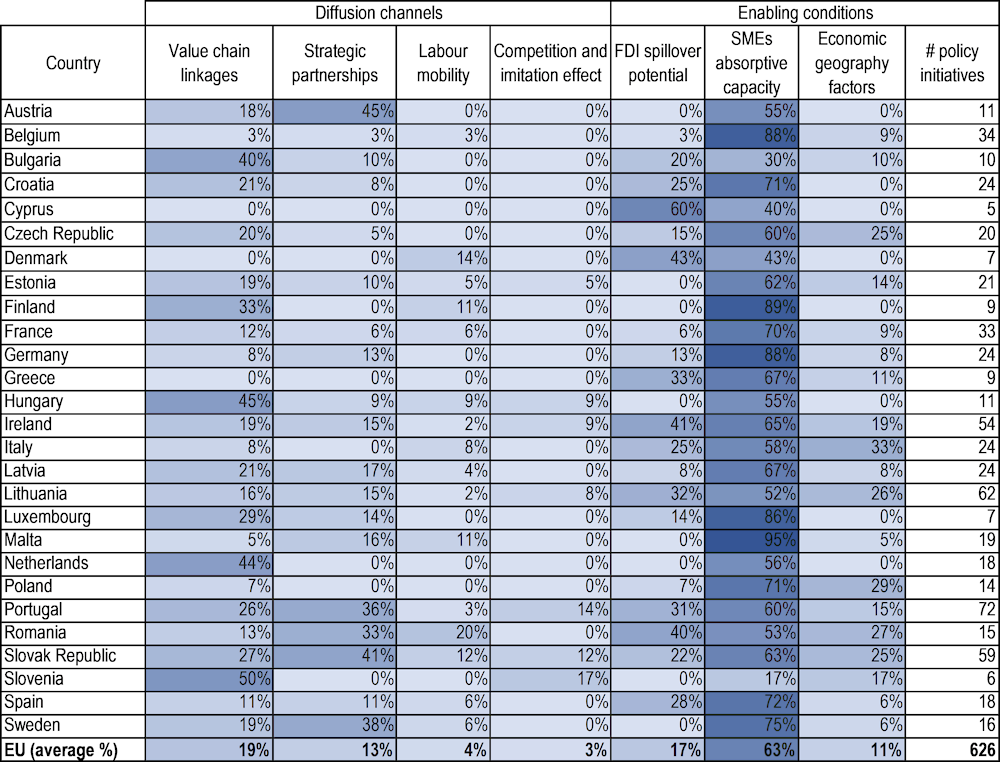

Table 5.1. The EU FDI-SME policy mix are mostly oriented towards increasing the absorptive capacity of SMEs

Distribution of FDI-SME policy initiatives by objective, as a percentage in terms of prevalence across all policies mapped by country, 2021

Note: Shares are calculated as a percentage of the total of national initiatives in place, based on an unweighted count. Shares may be higher than 100% when policy initiatives aim to address several policy objectives at the same time. For countries with few initiatives (observations), interpretation of indicators should be done with caution. EU (average %): average of the national shares of the 27 EU countries.

Source: Experimental indicators based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021).

Design of the FDI-SME policy mix across EU Member States: instrumentalisation and targeting

Public action to foster FDI spillovers on domestic SMEs is delivered through a broad set of policy instruments. These are defined as identifiable techniques for public action and the means for achieving the goals they are designed for (Lemarchand, 2016[6]), and spread from technical (non-financial) to financial support, from networking assistance to infrastructure and platform facilities, from regulatory easing to new governance frameworks such as national strategies/plans or institutional arrangements (Policy mapping methodology). The instrumentalisation reflects the many possible policy goals pursued, contexts shaping the potential of FDI-SME spillovers, and pathways towards achieving better FDI-SME policy. Instruments, and how they are combined, are therefore often very specific to the objectives they serve. The selection of instruments also reflects national policy styles and some policy legacy (Borrás and Edquist, 2013[7]). For instance, some instruments, particularly the financial ones, can dominate others for no other reason than they have been important in the past and have attracted around them vested interests that protect their position.

Greater focus on SME capacities is reflected into a more frequent use of financial incentives and technical assistance

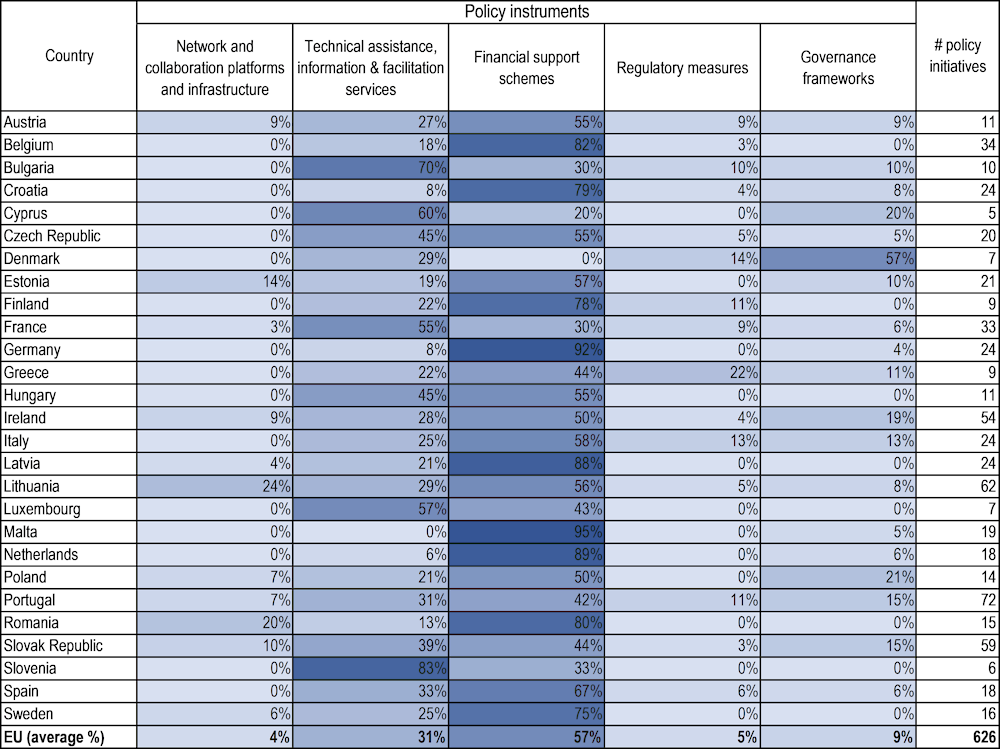

EU countries use mainly financial support (57% of all mapped initiatives), and technical assistance and facilitation services (31%), to strengthen FDI spillovers on domestic SMEs (Table 5.2). Financial instruments include grants, loans, tax credits and other forms of direct or indirect funding. Technical assistance, information provision and facilitation services include a wide range of business support measures and services (e.g. consulting, diagnostic, information, matchmaking and networking, training and skills upgrading, incubation, etc.).

However, the density of financial schemes for FDI-SME spillovers may vary across countries, from over 90% of the country’s policy mix in Malta (95%) and Germany (92%), to 30% or less in Bulgaria (30%), France (30%) or Cyprus (20%). Likewise, there is a large variation in the density of technical assistance measures implemented across EU countries, from 83% in Slovenia to less than 10% in Croatia (8%) or Germany (8%), the Netherlands (6%) or Malta (0%). The effectiveness of technical support instruments may also vary, e.g. depending on the number of institutions involved in implementation, and the degree of policy fragmentation (Chapter 2).

Table 5.2. Distribution of FDI-SME policy instruments across policy initiatives: An overview

As a percentage in terms of prevalence across all policies mapped by country, 2021

Note: Shares are calculated as a percentage of the total of national initiatives in place, based on an unweighted count. Shares may be higher than 100% when policy initiatives make use of several instruments at the same time. For countries with few initiatives (observations), interpretation of indicators should be done with caution. EU (average %): average of the national shares of the 27 EU countries.

Source: EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021).

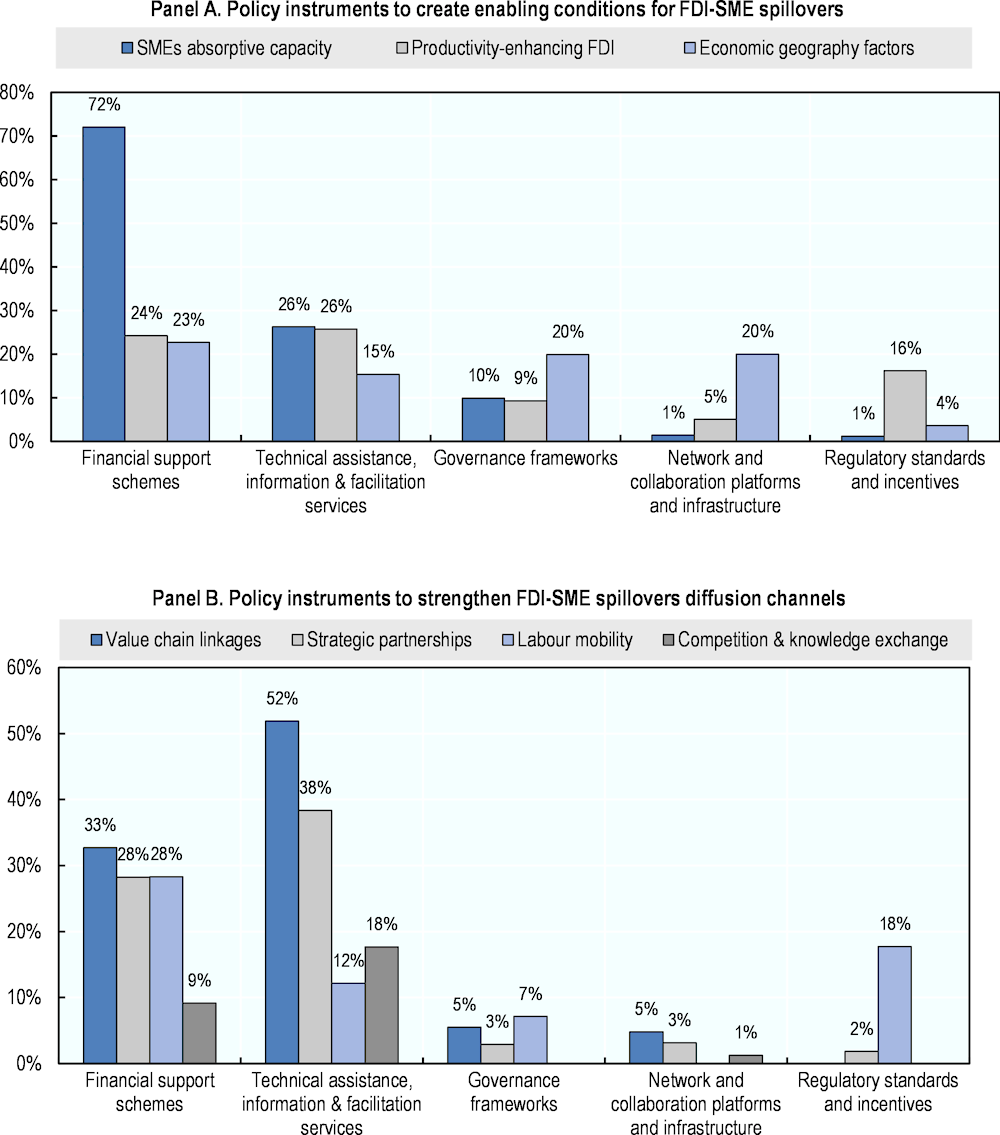

Policy instruments vary depending on the objectives they serve

Most policies aiming to scale up the absorptive capacity of SMEs make use of financial instruments (72%), and to a lesser extent from non-financial support, in the form of technical assistance, the provision of information, or facilitation services (26%) (Figure 5.3; Box 5.2). Broader governance arrangements, such as national strategies and plans, or regulatory provisions and networking platforms are less widespread.

Figure 5.3. Policy instruments vary depending on the objectives they serve

Note: For countries with few initiatives (observations), interpretation of indicators should be done with caution. Shares may be higher than 100% when policy initiatives make address several policy objectives at the same time.

Source: Experimental indicators based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021).

Box 5.2. Increasing SME absorptive capacity: country examples.

Providing direct financial support is the most common approach…

EU governments propose direct forms of funding through grants, loans or vouchers, to support SME activities in R&D and innovation (Annexe 5.A). In the Brussels Capital Region (Belgium), the R&D and innovation agency Innoviris supports with grants or repayable advances business R&D projects aiming to develop, complete or implement an innovative product, process or service. Bpifrance provides SMEs with guarantees to facilitate their access to bank credit in the riskier phases of their financing cycle; while the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) runs a Micro‑loan Fund to address the financing needs of smaller businesses, start-ups and self-employed pursuing creative ventures, and that would otherwise have no access to credit.

Many EU funding schemes for business R&D and innovation are designed to encourage science-to-business (S2B) and business-to-business (B2B) collaboration, including with foreign firms, reflecting the importance of networks for raising the innovation capacity of SMEs (Chapter 2; Box 5.5). Innovation voucher programmes such as those implemented by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (FFG) or Enterprise Ireland (EI), allow SMEs to purchase academic support and expertise and build linkages with knowledge institutions.

EU governments also support financially the digital transformation of SMEs as a key lever of SME performance (OECD, 2022[2]). The Austrian SME.DIGITAL programme provides comprehensive support for SMEs implementing digitalisation projects, including both consulting services and direct funding for investments in new technologies and digitalisation.

… often combined with non-financial support

Financial support measures are often combined with business consulting and training programmes for enhancing SME internal capacity and supporting organisational change. The Bulgarian SMEs promotion agency BSMEPA delivers training and tailored consulting services on entrepreneurship, innovation and internationalisation to domestic SMEs, both at its national headquarters in Sofia and through its regional offices. Given the importance of human capital for SMEs innovation, training and consulting programmes often focus on enhancing managers’ skills. It is the case of the Enterprise Ireland (EI)’s Innovation 4 Growth programme, which proposes educational modules, coaching and peer-learning opportunities to chief executive officers (CEOs) and senior managers, in order to strengthen their innovation culture and openness to new business models and practices. Similarly, the Investment and Development Agency of Latvia (LIAA), in collaboration with the Riga Technical University and Business School, launched a pilot Mini MBA training programme for improving the knowledge and practical skills of middle and senior managers in charge of business innovation and development processes.

Source: OECD Data Lake on SMEs and Entrepreneurship 2022, based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021).

Attracting FDI in productivity‑enhancing activities typically involves a more diversified set of instruments, and relies relatively more on non-financial support (26% of all related measures) and investment incentive packages combining financial (24%) and regulatory measures (16%) (e.g. fast-track licensing regimes, other regulatory and administrative easing for FDI) (Figure 5.3).

Box 5.3. Attracting and facilitating knowledge-intensive and productivity-enhancing FDI: country examples

Public services for embedding FDI in the host economy are widely proposed

Many governments provide potential investors with information on local investment opportunities, knowledge infrastructure and SMEs capabilities. Investment promotion agencies (IPAs) across the EU area play a key role in delivering this type of FDI-targeted consulting and information services. In both the Slovak Republic and the Czech Republic, the national IPAs (SARIO and Czechinvest respectively) run real estate databases that facilitate the identification of suitable FDI sites (e.g. building, land, tourism or industrial facilities). Upon request, Germany Trade & Invest (GTAI) provides prospective investors with tailored information and consultancy services, including intelligence gathering (e.g. market research, business opportunity analysis); investment site selection and evaluation; and administrative support (e.g. assistance with tax and regulatory issues).

Another common approach consists in facilitating matchmaking between foreign investors and local partners. The Portuguese programme Startups Connecting Links aims to connect domestic start-ups in specific sectors or activities with foreign multinationals (MNEs), with a twofold objective: promoting collaboration between foreign and domestic businesses and favouring the entry of MNEs into the Portuguese market through mergers and acquisitions (M&A). The Spanish Investor Network, implemented through the ICEX network of Economic and Commercial Offices abroad, aims to connect international investors with the domestic business fabric and facilitate contact between Spanish companies looking for capital and foreign investors.

Many countries propose investment incentive packages combining financial and regulatory measures

Investment incentives include both financial support aimed at reducing investment costs (such as grant schemes and tax incentives) and regulatory incentives (such as faster licensing procedures for knowledge-intensive projects). In many cases, support is conditional to investing in strategic sectors or activities. Under the Bulgarian Investment Promotion Act, investment in manufacturing, high-tech activities, education and human resources development may qualify for customised administrative support, fast track, assistance with real estate acquisition and financial aid for infrastructure development and staff related costs. The Lithuanian government adopted the Green Corridor for Large-Scale Investment Projects, a package of laws on investment facilitation which offers tax incentives and cut red tape for large scale strategic investment projects in manufacturing, data processing, and internet server hosting services. Investment incentives may also be place-based. Diverse EU countries have Special Economic Zones (SEZs), including Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Portugal and Romania. These schemes typically offer different types of incentives (e.g. tax relief, regulatory and administrative easing) to investment projects targeting selected sub-national areas or regions.

Source: EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021).

Network and collaboration platforms and infrastructure are more frequently deployed (20%) to create agglomeration economies and support clustering. These objectives are also commonly supported through financial instruments and dedicated government arrangements (Figure 5.3) (Box 5.4).

Box 5.4. Enhancing agglomeration economies and clusters: country examples

Public infrastructure such as networking and collaboration platforms supports agglomeration

Local platforms or infrastructure, such as industrial, science and technology parks, or Special Economic Zones (SEZs) facilitate agglomeration by promoting connectivity and exchanges among local stakeholders. They can benefit both foreign and domestic firms, providing land or office space to set up activities and diverse kinds of support to their business operation (e.g. tax incentives). In Latvia there are three SEZs (Liepaja, Latgale, Rezekne) and two free ports (Riga and Ventspils) offering benefits and a favourable tax regime to companies operating locally, including foreign investors. Lithuania has seven Free Economic Zones and five industrial parks across the country, providing physical and/or legal infrastructure, support services and tax incentives for business establishment and operations. In Romania, there are 104 industrial parks (operational or under development) which offer to their resident firms diverse utilities and benefits (e.g. land, building and urban planning tax exemption).

Cluster policy initiatives make a large part of the policy mix

Public support to clusters can take many forms, depending on the stage of development of the host country or region and the level of maturity of the cluster itself. Policies typically feature a combination of financial incentives and technical assistance to incentivise companies to group together or support emerging bottom-up agglomerations. Infrastructure and facilities may also be established to enhance B2B and S2B interactions. The Enterprise Ireland’s Regional Technology Cluster Fund offer financial support to increase the number of clustering companies in Ireland and enhance collaboration between firms and regional knowledge providers, such as Ireland’s Institutes of Technology (IoTs) and technical universities. The Swedish Agency for Regional and Economic Growth also runs a Cluster Programme to support selected cluster organizations that are prioritised in regional smart specialisation or development strategies. The adoption of whole-of-government approaches involving several implementing institutions and engagement with local actors is a recurrent characteristic of cluster policies across the EU area.

Financial incentives are provided for developing activities in lagging regions

Many government programmes seek to enhance entrepreneurship and investment in lagging regions through the provision of direct financial support. These include the German Cash Incentives Programme (GRW), implemented by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK), which provides grants to incentivise investment in eligible German regions. The Italian Resto al Sud programme provides non-repayable grants and credit guarantees to cover the costs of establishing a new business in lagging Southern and Central regions, Sardinia, Sicily and the smaller islands in the North and Centre. In Malta, the Gozo Transport Grant Scheme provides financial support to compensate the additional transport costs incurred by manufacturing firms operating on the Gozo island.

Source: EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021)

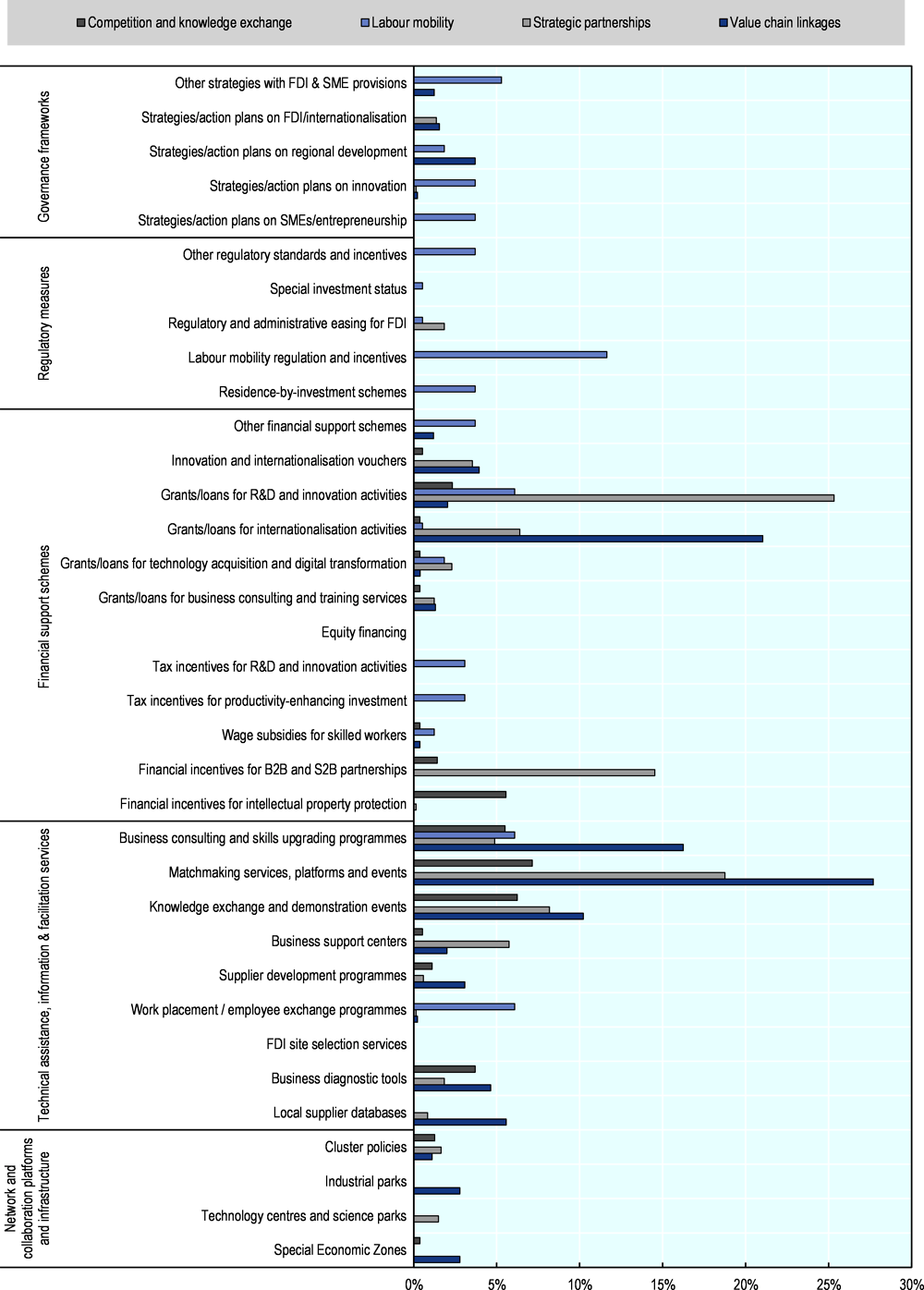

EU governments mainly support FDI-SME linkages through value chains and/or the setting of strategic partnerships on innovation and business development. For both diffusion channels, the composition of the policy mix is relatively similar and relies mainly on information and facilitation services one the one hand, and financial support on the other hand (Figure 5.3). Particularly, over half of the policies identified to foster value chain linkages use technical assistance instruments.

Box 5.5. Promoting value chain linkages and strategic partnerships: country examples

Matchmaking services, online platforms and events to link FDI and SMEs

Most IPAs provide matchmaking services to reduce the information barriers that prevent foreign investors from identifying local suppliers or customers. In the Slovak Republic, SARIO supports several matchmaking programmes targeting foreign firms and their affiliates, including the flagship Business Link events and Slovak Matchmaking Fairs, implemented under the auspices of the Ministry of the Economy (OECD, 2022[8]). The use of online tools and platforms is common in this area. In Bulgaria, the national SME promotion agency BSMEPA runs an online platform to advertise requests of foreign companies looking for partners in the domestic industry (e.g. local suppliers, local exporters, potential business partners). The Hungarian Investment Promotion Agency (HIPA) maintains a database of domestic firms to help large companies identify suppliers that meet their requirements and could integrate their value chain.

Many EU governments organise or actively support the participation of domestic SMEs in knowledge exchange and information events, which can provide matching opportunities with foreign partners. The Spanish agency Red.es, in collaboration with ICEX Spain Export and Investment, organises national stands in international events to support the internationalisation of domestic firms operating in the digital economy. In Bulgaria, the BSMEPA runs a dedicated project to support domestic SMEs’ participation in business fairs, exhibitions and conferences within the country and abroad, in a view to enhancing their export activities, facilitating the establishment of direct contacts and commercial linkages with foreign partners, and fostering their integration in European and international markets.

Assistance for upgrading the capabilities of domestic suppliers

Common instruments to develop value chain linkages are supplier development programmes – such as Portugal’s flagship Supplier Club or the Slovak Republic’ Supply Chain Development Programme – and other business consulting and skills upgrading schemes that seek to align the capabilities of domestic suppliers with the requirements of foreign investors. Some schemes specifically target SMEs or start-ups. In Sweden, the Leap Accelerator programme helps technology start‑ups develop tailored go‑to-market plans and build strategies for internationalisation via diverse training, consulting and peer-learning services (e.g. online collaborative workshops for groups of companies, individual coaching sessions, data-driven analysis tailored to the company's needs).

Financial support for enabling SME integration into GVCs or collaborative R&D

SMEs internationalisation through trade can facilitate market expansion and upgrading and help strengthen the domestic supplier base. The Dutch Trade and Investment Fund (DTIF), set up by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and administered by Invest International, provides loans, guarantees and export financing to domestic firms wishing to import, export or establish affiliates abroad. In Finland, Finnverra’s Internationalisation Loans support the costs of establishing and operating SME subsidiaries abroad.

Financial support is also given for collaborative research and development (R&D) and innovation activities involving foreign partners. Many of these schemes specifically target SMEs or reward their involvement with higher grant or loan rates (Box 5.2). The German Central Innovation Programme for SMEs (ZIM) includes two sub-schemes (ZIM cooperation projects and ZIM cooperation networks) that support with grants joint R&D&I projects by consortia of SMEs and research institutions. Since 2018, co‑operative projects involving foreign partners are also eligible for funding.

Source: EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021)

Regulatory measures (18%) and financial schemes (28%) are more commonly deployed to facilitate the mobility of skilled workers from foreign affiliates and MNEs to local SMEs (Figure 5.3).

Box 5.6. Facilitating FDI-SME spillovers through workers mobility: country examples

Governments use financial and regulatory incentives to attract talent from abroad

Leveraging spillovers from labour mobility requires addressing structural challenges related to the capacity and skills endowment of domestic SMEs. In this perspective, some EU governments provide different types of incentives (e.g. regulation, financial support) to facilitate the immigration of business talent from abroad, in a view to reduce labour and skills shortages in the local business sector.

Regulatory incentives include entrepreneur visa programmes, which seek to attract innovative entrepreneurs and highly skilled workers by allowing them to obtain residence and employment rights after setting up or transferring their business (Chapter 2). The Startup Denmark programme, for instance, is a visa scheme aimed at attracting to Denmark talented entrepreneurs from outside the European Economic Area (EEA). Beneficiaries are selected by an independent expert panel based on the quality of their business plan and are entitled to apply for a residence and work permit in Denmark as self‑employed. In Ireland, the Critical Skills Employment Permit is designed to attract highly skilled foreigners and encourage them to take up permanent residence in the State. Eligible occupations under the scheme are deemed to be critically important to growing Ireland’s economy, highly skilled and in significant shortage on the domestic labour market. The Italia Startup Hub scheme provides talented non-EU citizens who already resides in Italy and intend to start a new innovative company with a simplified path to extend their residence permit.

Different types of financial incentives (e.g. wage subsidies, payroll tax relief, tailor‑designed grant or loan schemes) are also commonly provided. Sweden, for instance, applies a special income tax relief to highly skilled foreign employees in their first three years of employment in the country. Belgium also provides fiscal incentives to encourage the temporary employment of executive staff from abroad by foreign companies operating locally. Some funding measures target national diaspora. The Italian Smart&Start scheme, which financially supports the creation of innovative startups in Italy, provides higher funding thresholds for business projects involving at least one Italian PhD who is working abroad and intends to return to Italy.

Work placement and employee exchange programmes with foreign firms operating abroad are also used to expand the local talent pool

The Portuguese investment promotion agency (AICEP) runs the INOV Contacto programme, which gives the opportunity to highly skilled graduates to conduct a short‑term internship in a Portuguese company, followed by a long‑term internship in a multinational company abroad (OECD, 2022[9]). In France, the business internship scheme Volontariat International en Entreprise (V.I.E.) allows young nationals to perform 6 to 24‑month professional missions at a French company abroad (dealing for instance with local market research, provision of support to local teams, supervision of construction sites, etc.). Although their effectiveness remains subject to broader labour market conditions, programmes of this kind may contribute to facilitate the transfer of knowledge and skills towards the local labour markets.

Source: EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021).

Instruments to support spillovers through competition and knowledge exchange are less diverse, and mostly include non-financial support (18%) (Figure 5.3). Some funding schemes are also available, mainly in the form of financial incentives for intellectual property rights (IPRs) protection (Box 5.7).

Box 5.7. Creating market conditions for fair competition and knowledge exchange between foreign and domestic firms: country examples

Policy intervention mainly focus on promote IPRs use among SMEs

IPRs play a key role in allowing SMEs to protect the value of their innovation and effectively cope with the competitive pressure generated by the entry of foreign firms. Governments seek to enhance their use among SMEs through a mix of financial incentives and technical assistance.

Examples of financial incentives for IPR protection include the Irish IP Strategy Offer, a grant scheme which aims to support R&D-performing innovative SMEs to develop an IP strategy focussed on their individual needs. The scheme seeks to help address two IP-related challenges that SMEs typically face: gaining access to appropriate external IP expertise; and developing internal IP awareness and capability. This is achieved by providing grant aid toward a portion of the costs of external IP advisors and internal IP champions. In Portugal, the IP Protection incentive supports firms that, following the implementation of R&D projects, aim to promote the registration of industrial property rights in the form of patents or utility models, at national, European and international level.

Support for IPR use among SMEs may also take the form of business consulting or diagnostic services, to help SMEs familiarise themselves with IPR protection tools and processes and learn about IPRs and their prosecution. The national innovation agency Enterprise Estonia (EAS) provides strategic IP advisory and consultation services for companies, with the aim of protecting and enforcing corporate intellectual property for business purposes. In the framework of its initiative Promotion of Life Sciences Industry Development, the Lithuanian Agency for Science, Innovation and Technology (MITA) also provides consultancy services on IP and patenting of innovative ideas for companies operating in the target sector of life sciences.

Networking and demonstration events are common tools to spur tacit learning and imitation

Networking, knowledge exchange and demonstration events, e.g. conferences, seminars, site visits, involve learning opportunities for SMEs through the improved visibility of foreign firm practices and technologies and the informal sharing of views and ideas (Chapter 2). Enterprise Ireland, the Irish SME agency, organises Best Practice Study Visits that allow Irish firms to visit the manufacturing plants of foreign firms and get first-hand experience on their business practices and processes. Similarly in Portugal, the national SME agency IAPMEI implements the Open Days i4.0 initiative, which aims to present the technological capabilities of innovative companies during stakeholder events and promote the sharing of experiences between market actors operating in the same value chain. In addition to moments of networking and information sharing, these public events include visits to the most advanced industrial plants in Portugal, presentations of innovative technologies, exhibitions of technological products and hands-on discussions between business representatives and other market stakeholders.

A few countries use cluster policies to support spillovers from competition and knowledge exchange

Clusters may provide a conducive environment for the diffusion of knowledge spillovers through informal business interaction and information exchange about good practices and standards. Enterprise Lithuania (an agency of the national Ministry of Economy) promotes the sharing of experiences among companies within clusters by organising and co-ordinating the Cluster Forum, a monthly meeting of cluster leaders and coordinators, during which participants share experiences, present success stories, discuss, consult, exchange advice on how to solve the most common problems within clusters, and invite cluster experts.

Source: EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021)

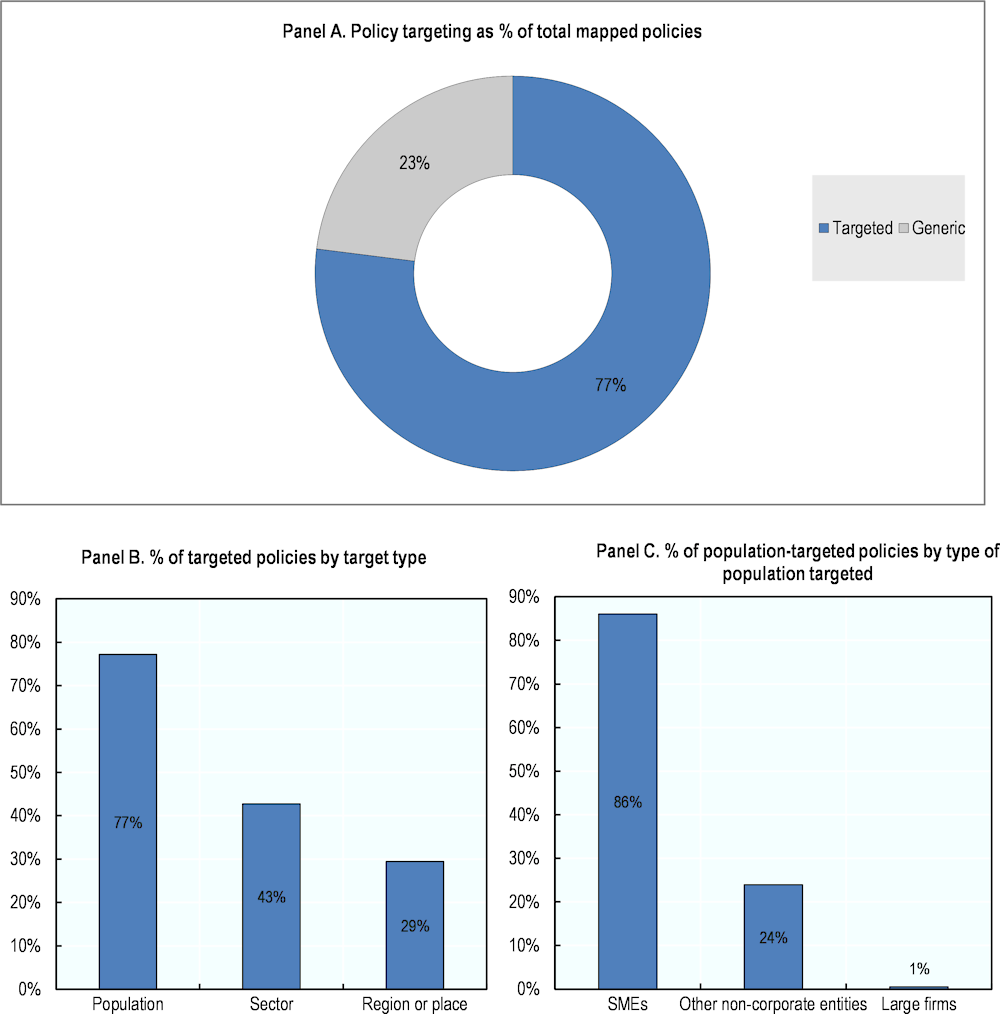

Most FDI-SME policies are targeted, and often at SMEs

FDI-SME policies typically combine generic measures with targeted initiatives aiming at specific populations, sectors of the economy, or sub-national areas to help them tackle barriers in capturing spillovers. Across the EU, targeted policies represent 77% of the 626 mapped policies (Figure 5.4, Panel A) and many of them target several dimensions at once.

Policies aimed at a specific population represent 77% of all targeted policies (Figure 5.4, Panel B). SMEs are by far the main beneficiaries of support (Figure 5.4, Panel C). Policies targeting non‑corporate entities, such as universities and research centres, also aim to ease the transfer of knowledge to local SMEs. Policies towards private investors, business angels and venture capital funds contribute to improving SME access to funding.

Policies with a sectoral focus represent 43% of targeted policies (Figure 5.4, Panel B). These measures either target selected sectors or exclude them from their scope of application. By encouraging the technological upgrading of specific industries, governments intend to attract more knowledge‑intensive FDI while helping SMEs operating in those industries scale up their innovation capacity.

A significant share of targeted policies (30%) also takes a place-based approach (Figure 5.4, Panel B). This includes policies targeting specific geographic areas only or giving them preferential treatment. For example, under the Smart&Start Italy scheme – which provides interest-free loans to support innovative start‑ups in the digital economy – beneficiaries from selected lagging Central and Southern regions are entitled to an additional non‑repayable grant.

Policy targeting is more commonly used for enhancing SMEs absorptive capacity and for acting on the economic geography drivers of spillovers, as well as for enhancing the mobility of highly skilled workers. Over 80% of the initiatives addressing these three strategic objectives are targeted. The proportion of targeted measures is slightly lower for supporting productivity‑enhancing FDI or the other spillovers diffusion channels (value chain linkages, strategic partnerships, competition) (65-70%).

Figure 5.4. Most FDI-SME policies target specific populations, sectors or places

Note: Panel A: Shares of generic and targeted policies as a percentage of the total 626 policies mapped. Panel B: Shares of policies by target type, as percentage of total targeted initiatives (482). As policies can be directed at more than one type of target, the sum is above 100%. Panel C: Shares of policies by type of population targeted, as percentage of total population-targeted policies (372). SMEs‑targeted policies include initiatives applying to SMEs only or providing preferential conditions to them. Other non-corporate entities include: investors (business angels, venture capitalists or VC funds, banks, financing institutions, etc.); universities; research organisations; entrepreneurs; individuals with specific roles or skillsets (e.g. managers, highly-skilled, researchers); government institutions and sub-national governments (e.g. municipalities); and others. For countries with few initiatives (observations), interpretation of indicators should be done with caution.

Source: Experimental indicators based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021).

Many countries adopt governance frameworks to co-ordinate policy intervention in support of FDI-SME ecosystems

Some policy instruments have co-ordination functions and ensure overarching policy governance. This is the case for national strategies and action plans in the areas of SMEs and entrepreneurship, innovation, regional development or investment policy, as well as other governance frameworks with provisions related to FDI and SMEs. Instruments of this type are obviously less numerous, representing only about 10% of total policies mapped across the EU. However, they may play an important role in ensuring the overall balance of the policy mix in support of FDI-SME ecosystems, by setting goals, procedures and other arrangements that guide public action in relevant policy areas (OECD, 2021[10]) (Chapter 2).

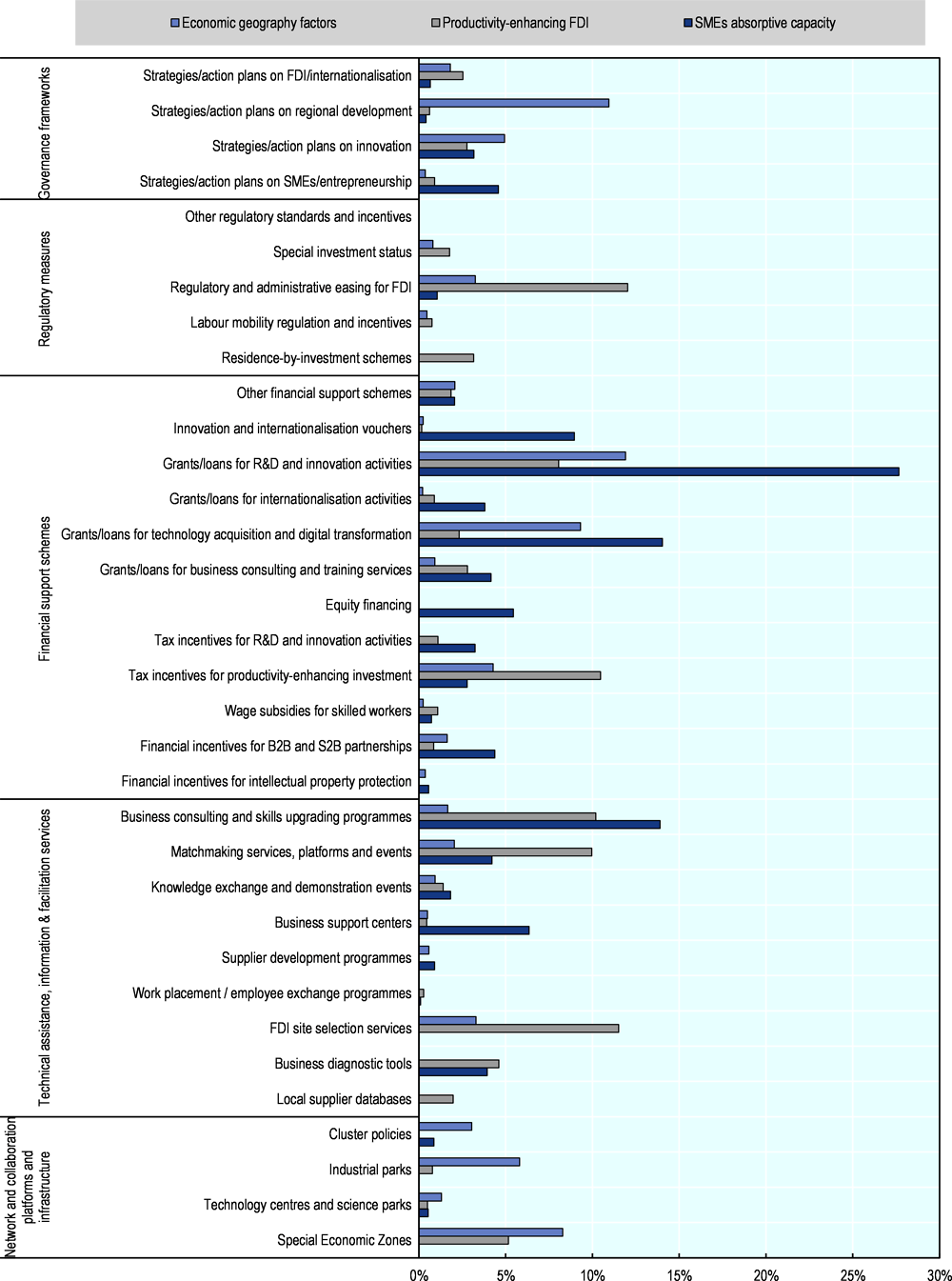

Governance frameworks are more frequently deployed for improving the enabling environment of FDI-SME spillovers, rather than for strengthening diffusion channels themselves. Particularly, national strategies and plans are used by 20% of policies to enhance the economic geography factors of spillovers – a higher share than for any other strategic objective (Figure 5.3). Most of these strategies and plans focus on overcoming regional inequalities and ensuring a balanced development of subnational areas.

Governance frameworks are also common in the area of SME&E, where they account for 10% of the related policies. Some countries adopt self-standing policy documents such as multi-annual SME strategies by the central government or SME action plans; others incorporate SME relevant support in wider policy frameworks, e.g. on innovation (Annex 5.A) (OECD, 2021[10]). Governance frameworks for investment promotion (9%) also include dedicated investment or internationalisation strategies and other strategies with provisions related to strengthening FDI-SME ecosystems.

Box 5.8 provides some country examples of governance frameworks of relevance to FDI-SME ecosystems.

Box 5.8. Governance frameworks to enhance FDI-SME ecosystems: country examples

Governance frameworks on regional development

Regional gaps in productivity and competitiveness may affect the performance of FDI-SME ecosystems, reducing the attractiveness of less developed sub-national areas to foreign investors and limiting the capacity of the business sector to capture FDI spillovers at local level (Chapter 2). To achieve a balanced development of Czech regions, the Regional Development Strategy of the Czech Republic 2021+ identifies a set of strategic goals, which include providing regions with targeted support; developing the territorial dimension of sectoral policies; strengthening co‑operation among local actors; and improving the collection and treatment of regional data. In Italy, the Southern Italy 2030 strategy aims to support the economic development of southern regions by encouraging investment in entrepreneurship and innovation education and providing tax incentives for companies performing R&D and hiring local staff, with a special focus on attracting foreign investment.

Regional development strategies typically promote the engagement of sub‑national actors in their implementation. In Ireland, for instance, the Department of Enterprise, Trade and Employment’s Regional Enterprise Plans are developed by regional stakeholders in each of the nine Irish regions. Their implementation is overseen by a Regional Steering Committee comprising representatives of local authorities and the regional private sectors.

Governance frameworks on SMEs and entrepreneurship

A number of EU countries adopt dedicated national strategies or action plans on SMEs and entrepreneurship. Some of these governance frameworks put emphasis on new entrepreneurship and start-ups, such as the Start-up Estonia strategy, the Start Up Portugal + strategy, and the Slovak Concept for the support of Startups and the development of a Startup ecosystem. Others rather focus on achieving competitiveness, growth, innovation and digitalisation in the SME population as a whole. The Czech Republic recently adopted a SMEs Support Strategy 2021‑2027, featuring 107 measures to increase the productivity and competitiveness of Czech SMEs. Key areas in focus include the business environment; access to finance; access to markets; workforce, skills and education; R&D&I; digitalization; low-carbon economy and resource efficiency.

Governance framework on innovation

By improving the governance and co-ordination of the broader national innovation system, innovation strategies may also contribute to create a conducive environment for SMEs innovation and FDI attraction. In France, the Investments for the Future Programme 4 2021-2025 (PIA 4) allocates resources to support researchers and entrepreneurs’ innovation activities, with a particular focus on supporting (1) priority sectors and technologies and (2) the higher education, research and innovation ecosystem. The German High-Tech Strategy 2025 provides a framework for co-ordination of all the research programmes financed by the German federal government and orientation for all the national players involved in innovation.

Governance frameworks on investment promotion

Some EU countries adopt dedicated investment strategies. For example, the Invest in Denmark Strategy 2020-2023 specifically aims to enhance inward foreign investment and also features a focus on attracting technology- and knowledge‑intensive FDI. In Portugal, the Internationalize 2030 Programme, adopted in 2020, features 43 action measures aimed at improving attraction foreign investment and increasing export over the next decade.

Other countries integrate investment promotion goals in broader innovation and entrepreneurship development frameworks. Particularly, diverse countries developed smart specialisation and industrial strategies that incorporate FDI policy goals. For example, several strategic pillars of Cyprus’ Industrial Policy 2019‑2030 – e.g. development of new infrastructure, improvement of the local business conditions, enhancement of industrial internationalisation and export performance – indirectly support the goal of improving the country’s attractiveness to quality FDI.

Source: EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021)

Conclusions

This chapter provides insights on the FDI-SME policy mix in the EU area, including their density, the priority given to different strategic objectives, the intensity of use of different policy instruments, and the prevalence of targeted or generic approaches. A pilot mapping of policy institutions and initiatives relevant to strengthening FDI-SME linkages and spillovers was carried out between January and September 2021 across the 27 EU member countries and helped identify 626 FDI-SME policy measures that allow for a first assessment of public support in this area.

The analytical work shows that FDI-SME policies are broad in scope and span across different policy domains, including innovation, entrepreneurship, regional development and investment. It is therefore not surprising that all the 27 EU governments have initiatives in place that can affect, directly or indirectly, the likelihood and intensity of FDI-SME linkages and spillovers. Nevertheless, the pilot mapping suggests that the extent of policy efforts, measured as per the number of policy initiatives on place, varies greatly across countries.

Cross-country differences are also striking in the orientation of the policy mix. If the overall policy focus across the EU is on creating an enabling environment for spillovers (particularly by reinforcing SMEs absorptive capacity), Austria, Hungary and Slovenia put above-average emphasis on strengthening diffusion channels themselves (i.e. value chain linkages, strategic partnerships, labour mobility and competition), and Cyprus, Denmark and Italy aim to improve FDI embeddedness and spillover potential, and encourage agglomeration, clustering and some economy geography enablers.

A strong focus on SMEs and their absorptive capacity is reflected in FDI-SME policy instrumentalisation that is aligned with the objectives pursued. Financial support schemes and technical assistance and information services are the most common instruments used to strengthen FDI spillovers on domestic SMEs. Regulatory measures are more often used to support productivity-enhancing FDI (16%) or facilitate the mobility of skilled workers (20%). Similarly, network and collaboration platforms and infrastructure are more frequently deployed (20%) to enhance agglomeration economies and clustering.

A very high proportion of the mapped FDI-SME policies is targeted at specific populations, sectors of the economy, or geographical places and regions, in order to tackle the barriers that these different types of actors face in attracting FDI and capturing spillovers. The proportion of targeted versus generic policies remains significant whatever the strategic FDI-SME objective(s) pursued, although it is particularly high among policies supporting SMEs development, the economic geography factors, and the mobility of highly skilled workers. Population-targeted approaches mostly consist of policies that target SMEs (82%). Looking ahead, more granular evidence on the industrial sectors or the territorial levels targeted would help gain further insights on this aspect of policy design.

Many factors can explain variations in the overall balance and density of the FDI-SME policy mix across the EU. These include country-specific characteristics such as the national industrial structure and specialisation, the degree of regional inequality, and the geographical distribution of business and investment activities. Initial evidence points to the degree of institutional fragmentation (i.e. the number of institutions involved in FDI-SME policy making) (Chapter 2) as one factor behind cross-country differences in the number of policy measures in place. Further research could help shed light on other factors and help understand to what extent national specificities and contexts, or the diversity of FDI‑SME ecosystems, can explain the orientation of the policy mix, and vice versa.

The objective of this pilot exercise was to provide an overview of the character and intensity of public efforts in the policy area under observation. The analysis is based on an unweighted count of initiatives that does not take into account other factors such as, for instance, the scope of national spending on initiatives, nor the strategic importance of some policies as compared to others. More information on the relative weight of policies (e.g. budget earmarked, number of beneficiaries) could help fine-tune the present analysis and provide a better perspective on the balance of the policy mix.

More granular information would also be needed to gain insights on policy governance and implementation aspects and particularly on the effectiveness and efficiency of public intervention. This would require the observation of a broader set of variables, including for instance information on impact evaluation or joint implementation and programming mechanisms in place. However, currently this information is largely unavailable or difficult to collect through desk research. A more in-depth analysis of these aspects was carried out as part of the pilot country reviews of Portugal and the Slovak Republic (OECD, 2022[8]; OECD, 2022[9]), conducted in the framework of Phase I of the FDI-SME project with the support and collaboration of the national taskforces established for the project. Future work under Phase II will aim to address current limitations in data collection and analysis and expand the scope of variables under observation, building on the lessons learnt from the country review process and also through a broader involvement and consultation of national implementing institutions in the policy mapping exercise.

Annex 5.A. Typologies of policy instruments by objective, EU average

Annex Figure 5.A.1. Types of policy instruments supporting enabling conditions of FDI-SME spillovers

Note: EU average % of national initiatives supporting enabling conditions, by type of instrument used. For countries with few initiatives (observations), interpretation of indicators should be done with caution. Shares may be higher than 100% when policy initiatives make use of several policy instruments at the same time.

Source: Experimental indicators based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021).

Annex Figure 5.A.2. Types of policy instruments supporting FDI-SME diffusion channels

Note: EU average % of national initiatives supporting diffusion channels, by type of instrument used. For countries with few initiatives (observations), interpretation of indicators should be done with caution. Shares may be higher than 100% when policy initiatives make use of several policy instruments at the same time

Source: Experimental indicators based on EC/OECD Survey of Institutions and Policies enabling FDI-SME Linkages (2021).

References

[7] Borrás, S. and C. Edquist (2013), “The choice of innovation policy instruments”, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Vol. 80/8, pp. 1513-1522, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2013.03.002.

[3] Guy, K. et al. (2009), Designing policy mixes: Enhancing innovation system performance and R&D investments levels, R&D policy interactions Vienna. Joanneum Research.

[6] Lemarchand, G. (2016), UNESCO’s Global Observatory of Science, Technology and Innovation Policy Instruments, https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.1.1296.2322.

[1] Meissner, D. and S. Kergroach (2019), “Innovation policy mix: mapping and measurement”, Journal of Technology Transfer, Vol. 46/1, pp. 197-222, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-019-09767-4.

[2] OECD (2022), Financing Growth and Turning Data into Business: Helping SMEs Scale Up, OECD Studies on SMEs and Entrepreneurship, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/81c738f0-en.

[9] OECD (2022), Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages in Portugal, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d718823d-en.

[8] OECD (2022), Strengthening FDI and SME Linkages in the Slovak Republic, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/972046f5-en.

[10] OECD (2021), “SME and entrepreneurship policy frameworks across OECD countries: An OECD Strategy for SMEs and Entrepreneurship”, OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Papers, No. 29, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9f6c41ce-en.

[5] OECD (2021), SMEs and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2021, https://doi.org/10.1787/97a5bbfe-en.

[4] OECD (2019), SMEs and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019, https://doi.org/10.1787/34907e9c-en.

Note

← 1. Note by Türkiye: The information in this document with reference to “Cyprus” relates to the southern part of the Island. There is no single authority representing both Turkish and Greek Cypriot people on the Island. Türkiye recognises the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC). Until a lasting and equitable solution is found within the context of the United Nations, Türkiye shall preserve its position concerning the “Cyprus issue”.

Note by all the European Union Member States of the OECD and the European Union: The Republic of Cyprus is recognised by all members of the United Nations with the exception of Türkiye. The information in this document relates to the area under the effective control of the Government of the Republic of Cyprus.