Sabine Vuik

Jane Cheatley

Sabine Vuik

Jane Cheatley

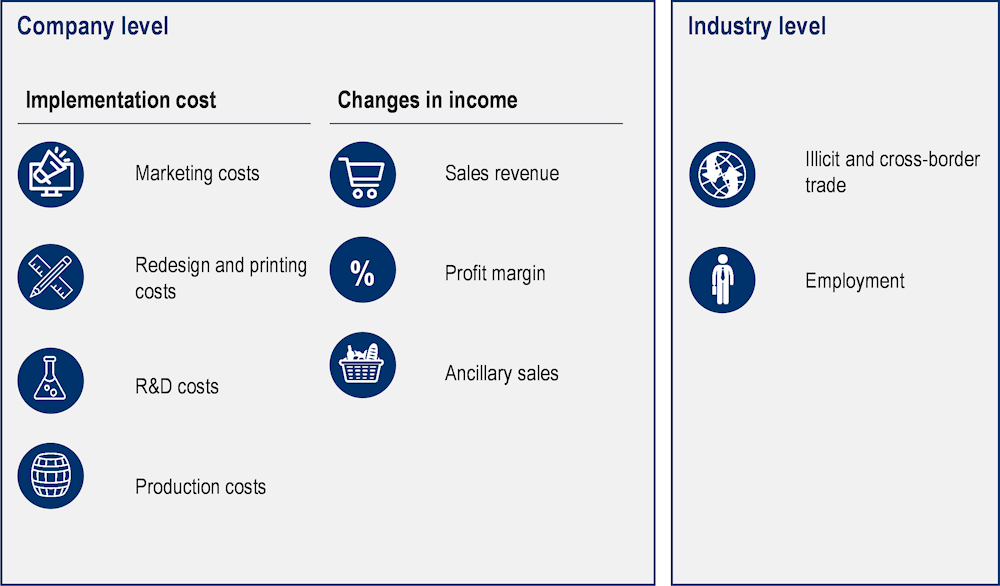

This special focus chapter looks at the impact public health policies can have on the alcohol industry. It considers implementation costs, such as changes in marketing, research and development, redesign and printing, and production costs, as well as changes in sales or profits for individual companies. At the industry level, it looks at the impact of alcohol policies on illicit and cross-border trade and on employment, as well as the potential impact on other sectors of the economy.

Public health policies to reduce harmful alcohol consumption can have an impact on the alcohol industry – including alcohol producers and both off- and on-trade vendors.

Alcohol policies may lead to implementation costs for the industry:

In response to policies that change regulations around alcohol marketing, the industry may incur costs for developing a new advertising strategy, changing their product portfolio or diverting marketing funding to other channels.

Price policies such as taxes or minimum prices may result in printing and labour costs to change menus and price displays. Similarly, the introduction of warning labels may lead to label redesign and printing costs.

If producers decide to respond to new policies by reducing the alcohol content of their products, they will have to invest in research and development (R&D).

The production costs of lower-alcohol products can be higher or lower than the original versions.

Alcohol policies can affect the income of the industry, as they can affect sales or profits:

Depending on the pass-through rate, taxes can lower sales or profits for the industry.

Price policies affect on- and off-trade vendors differently: taxation is likely to have a greater impact on off-licence trade, where price elasticity is generally greater, and minimum prices are less likely to have a major impact on on-licence vendors, whose prices are generally above any minimum threshold.

Minimum price policies can increase income for the industry, as the smaller price differential with premium products makes them more attractive, and the higher price charged for lower-end products may partially or completely offset the losses in sales.

Through reformulation, the industry can create new revenue streams responding to a growing demand for lower-alcohol products.

Alcohol policies that reduce sales of alcohol can also have an impact on ancillary sales, where alcohol is used to entice customers into the store or sold to create a one‑stop-shop convenience.

In addition to affecting the operations of individual alcohol companies, public health policies can also have an impact on the industry as a whole:

Price or availability policies can lead to an increase in illicit trade, while differences in policies between neighbouring countries can drive cross-border trade.

A reduction in revenue or profits for the alcohol industry could reduce employment in this sector, but this could be partially or fully offset by an increase in employment in other sectors.

To reduce the health and economic impact of harmful alcohol use, many countries have introduced public health policies and initiatives to reduce alcohol consumption. In line with the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol (WHO, 2010[1]), these include price policies such as taxation or minimum unit pricing (MUP), marketing regulations and sales restrictions (see Chapter 6 for more details on alcohol policies).

In addition to affecting population health and the economy, these policies also have an impact on the industry. The alcohol industry can be defined as “developers, producers, distributors, marketers and sellers of alcoholic beverages” (WHO, 2010[1]). This chapter primarily focuses on the two largest players who are most affected by alcohol policies: producers and vendors (Box 8.1), and references to the alcohol industry indicate these two groups.

The alcohol industry includes a number of actors, the two largest of which are alcohol producers and vendors.

Producers include distillers, brewers and wine makers. The global market is very different across drinks categories. While four international alcohol producers make up nearly half of the global beer production, the wine market is much more fragmented, with the top four producers only accounting for 13% of global sales (IAS, 2018[2]). The major drinks companies usually produce a large range of drinks products, catering for different market segments.

Vendors include both on-licence or on-trade sellers, who sell drinks that are consumed on the premises, and off-licence or off-trade vendors, who sell drinks that are taken away (IAS, 2018[2]). The relative contribution of these two players differs by product and country. For example, in the United Kingdom, nearly 50% of beer is consumed on-trade, while 84% of wine is bought in stores for off-trade consumption (IAS, 2018[2]). In Germany, on-licence sales account for 14% of total alcohol consumption, while in Belgium 48% of alcohol is sold by on-licence vendors (Rabinovich et al., 2012[3]).

On-trade sellers include pubs, cafés, bars, clubs, hotels, restaurants, theatres and sporting stadia. An important difference between these industry players is that only the first three rely on alcohol sales as a primary source of revenue. Off-trade vendors differ by country. While in the United Kingdom supermarkets account for two‑thirds of off-trade sales, other countries rely more on liquor stores. In the Canadian province of Ontario, off-trade sales of alcohol are almost entirely restricted to the state‑run Liquor Control Board of Ontario outlets. These types of vendor also differ in their reliance on alcohol as a revenue stream: while alcoholic drinks can be used by supermarkets to attract customers to buy other products, liquor stores rely almost entirely on sales of alcohol (OECD, 2015[4]).

Public health interventions to reduce harmful alcohol use can affect the industry in various ways (Figure 8.1). This chapter first discusses the potential impacts of alcohol policies at the company level. For alcohol producers or vendors, policies can result in implementation costs, such as changing a marketing strategy or investing in research and development (R&D). The chapter next examines how policies can also affect companies’ income, as they may change sales revenue, profit margins or ancillary sales. Finally, it investigates the potential effects at the wider industry level, outlining how alcohol policies can have an impact on illicit and cross-border trade and employment.

The information in this chapter is based on a review of the academic and grey literature and on input from experts participating in the OECD Expert Group on the Economics of Public Health, including representatives from business and industry. To complement the information gathered from the literature, the OECD conducted a survey among alcohol industry players through the Business at OECD network. Business at OECD is an international network representing over 7 million companies of all sizes, providing a business voice to the OECD.

Owing to the scarcity of data and other resources, a full assessment of macroeconomic impacts is beyond the objectives of this special focus chapter. Instead, this review aims to give an overview of possible direct and indirect impacts of public health policies on the alcohol industry.

Policies to tackle harmful alcohol consumption can result in implementation costs for alcohol companies (Box 8.2). Any policy that affects alcohol products based on the amount of alcohol they contain may lead producers to reformulate their products. Changes in advertising regulations or pricing policies may require companies to modify their packaging and marketing strategies. The most important cost items that result from these policies are changes in marketing and advertising spend; redesign and printing costs; investment in the development of techniques to lower the alcohol content of beverages; and changes in production costs. These implementation costs are discussed below. There may also be additional compliance costs associated with employing staff or consultants to work on regulatory compliance, administration and reporting (OECD, 2020[5]). However, due to data limitations and the wide variety of policy options, policy design and countries, these topics are not addressed in this special focus chapter.

Through the survey among alcohol industry players through the Business at OECD network, industry players highlighted the following expected implementation costs for the alcohol industry.

Advertising restrictions: The industry reported that advertising restrictions can result in adjustment and reorganisation costs associated with replanning marketing activities, and that there may be costs or penalties associated with the cancellation of existing advertising and sponsorship contracts, the redundancy of some marketing employees and potential reskilling efforts.

Regulation on sales of alcohol: Industry players noted that reformulation may result in reorganisation costs to explore and adapt to new distribution, restocking and servicing models. Respondents also reported that operating costs may change, but this depends on the type and extent of the restriction.

Reformulation: The industry expected the implementation costs of reformulation to be similar to any new product development, which may involve new production techniques that can be more expensive. If the transition period is short, the industry expected that costs may be incurred to substitute existing stock. To market the reformulated product, the industry noted that investment in branding is needed.

Taxes: According to the industry, tax rate increases reduce profits, owing to a combination of lower sales (from higher prices if the tax increase is passed on), or lower margins (if the tax increase is absorbed by the business to mitigate tax-driven price increases). If sales are reduced, fixed production and operating costs will be higher per unit of product.

MUP: The industry expected some disruption costs associated with changing packages and promotions, and with the potential delisting of certain SKUs (stock-keeping units: particular brands and pack offerings). Delisting was also expected to change the average production cost across the portfolio.

Source: Business at OECD response to OECD alcohol industry survey, April 2020.

Any policy that changes the regulations around alcohol marketing – such as advertising restrictions but also policies that restrict competition on price – can have an impact on alcohol companies, which may need to develop a new advertising strategy, change their product portfolio or divert marketing funding to other channels. Some practical examples in which alcohol policies may trigger marketing costs include the following:

Alcohol producers may have to spend money on advertising agency fees (or commit time internally) to review and redesign their marketing strategy in response to changes in advertising regulation. The cost to the alcohol industry of redesigning marketing strategies will depend largely on the complexity of adhering to regulations. It is possible that restrictions on certain channels or types of marketing could force companies to adopt alternative, more expensive advertising options. However, in specific cases, it has been shown that current advertising practices may be adapted to meet new standards (for example, targeting an older audience or airing at a different time), without affecting the cost (Ross, Sparks and Jernigan, 2016[6]). Finally, there may be costs associated with cancelling planned advertising or sponsorships, but sufficient transition time could reduce this impact (Box 8.3).

Policies affecting a specific type or category of alcohol products could drive the industry to change their stock or portfolio. For example, in the case of MUP, the price increase would apply to only part of the producer’s or vendor’s portfolio of brands (Leicester, 2011[7]). Supermarkets are likely to stock both cheap and more expensive versions of each beverage type, and large producers generally have a portfolio of brands at different price points. Changing a portfolio or stock may be associated with marketing and strategy development costs.

Changes in advertising regulations may force companies to switch to other marketing channels. For example, the introduction of minimum prices would limit competition based on price. As a result, companies may decide to invest in non-price competition, such as media advertising (Leicester, 2011[7]). However, this may simply be a reallocation of existing funds rather than new investment.

Restrictions in point-of-sale marketing, especially promotional allowances, could have an impact on the marketing budget of alcohol vendors. The 14 major alcohol companies spent USD 159 million per year in the United States on promotional allowances for alcohol vendors (Federal Trade Commission, 2014[8]).

Through the Business at OECD survey, industry players highlighted various ways in which policy-makers could reduce the impact of public health policies on the alcohol industry.

Advertising restrictions: To mitigate or reduce the impact of advertising restrictions on business, industry players suggested focusing restrictions on situations when the audience is vulnerable, or restricting certain content. The industry also suggested that consistent and transparent self-regulation to control content can add value. Industry representatives further mentioned that advertising can be a useful tool to promote reformulated products. As outlined in Chapter 6, however, a systematic review of industry self-regulation concluded that alcohol advertisements continually violate self-regulatory codes, meaning that young people are frequently exposed to alcohol advertising material (Noel, Babor and Robaina, 2016[9]).

Reformulation: The industry highlighted that reformulation can be encouraged by creating incentives – for example, through calibrated price policies and support for R&D. Furthermore, respondents to the survey raised the fact that product labelling rules need to be adjusted to enable sales and marketing of lower-alcohol beverages. For instance, European legislation currently requires whisky to have at least 40% alcohol by volume (European Commission, 2019[10]).

Taxes: The industry suggested that incentives to reformulate, through calibrated taxation, would be a better route to achieving the reduction in harmful consumption because these would offer options to producers to combine lower ethanol volume sold with smaller or no loss in financial revenue or jobs. The importance of enforcement against illegal sales replacing lost legal sales was also raised.

MUP: Industry respondents emphasised the need to set the minimum price at the right value to avoid raising the price of “average‑priced” products, and to ensure that the price hike generates additional margin for both supplier and retailer. The industry suggested that a period of adjustment would help businesses and – as with tax – it would be important to step up enforcement against illegal sales of products below the minimum price (smuggling, counterfeiting).

Source: Business at OECD response to OECD alcohol industry survey, April 2020

Price policies such as taxes or minimum prices may result in costs to vendors for changing menus and price displays – both printing and labour costs. However, where prices are displayed on shelves, digitally or on single‑use paper menus, these costs may be minimal.

Similarly, the introduction of warning labels on alcohol containers can incur redesign and printing costs. In 2020, Food Standards Australia & New Zealand (the statutory authority for developing food standards) undertook a review to estimate the costs the industry would incur for implementing mandatory pregnancy warning labels (FSANZ, 2020[11]). Their analysis estimated that the average cost per SKU for including a pregnancy warning label was AUD 4 924 (USD 3 420) (this could be lowered if companies combined mandatory and voluntary label replacements, which occur approximately once a year or more).

A change in labels may also lead to loss of stock, especially for slow-moving items such as spirits. To minimise the impact on the industry, the Australia and New Zealand Ministerial Forum on Food Regulation specified a three‑year transition period (with permission for alcoholic beverages packaged and labelled before the end of the transition period to be sold after the transition period without having to display a pregnancy warning label) (FSANZ, 2020[11]).

If producers decide to respond to new policies by reducing the alcohol content of their products, they have to invest in R&D. While many techniques for producing lower-alcohol products exist, producers will need to experiment to find the right approach for their product. This includes costs for consumer testing of new products, as taste remains one of the main issues for acceptability of lower-alcohol products. However, limited data are available on the costs of R&D for alcohol companies.

Some governments have supported the research of production methods for lower-alcohol products by investing in research. The Lighter Wines Programme, a research imitative undertaken by the New Zealand wine industry, received NZD 8.13 million (USD 5.18 million) from the government, which was combined with NZD 8.84 million (USD 5.64 million) from the industry, to develop a number of viticulture and winery tools for the production of lower-alcohol wines (Ministry for Primary Industies, 2017[12]). In addition, the alcohol industry argues that, to justify investment in R&D for lower-alcohol products, some regulations may need to be reviewed (for example, product labelling rules need to permit lower-alcohol forms, such as low-alcohol whisky).

If producers decide to reduce the alcohol content of their products, they may also see changes in their production costs. The type of process used to produce the lower-alcohol beverage is one of the main determinants of changes in production cost – for example:

Limited fermentation methods: the arrested or limited fermentation process can be performed using existing production methods, and therefore requires less up-front investment (Brányik et al., 2012[13]). This process can reduce the production time and raw materials required, making the overall production cost the same or lower than for regular beverages. However, additional costs may be associated with ensuring the shelf life of these low-alcohol products. Beer and wine produced through restricted fermentation may be left with high levels of unfermented sugar, which make them more perishable (Sohrabvandi et al., 2010[14]; Schmidtke, Blackman and Agboola, 2012[15]). While there are methods to improve shelf life, such as pasteurisation, these add cost and can affect the flavour of the product.

Alcohol removal methods: in comparison, the capital costs of alcohol removal methods such as reverse osmosis and high vacuum distillation are high, and the removal of alcohol to below 0.45% consumes a high level of electricity per litre of ethanol removed (Schmidtke, Blackman and Agboola, 2012[15]). These methods therefore require investment in equipment and higher ongoing production costs. However, the quality of the beer and wine may be higher, as the flavour is closer to the full-alcohol product (Schmidtke, Blackman and Agboola, 2012[15]; Brányik et al., 2012[13]). The cost of buying a reverse osmosis machine – quoted as being between USD 30 000 and more than USD 2 million (Goode, 2009[16]; Goldfarb, 2007[17]) – is significant for many wine producers. Smaller producers who do not have the economies of scale for large capital investments can rent alcohol removal machines and pay per volume of wine treated. For example, in Australia this cost is estimated at AUD 0.10 (USD 0.07) per litre to reduce the alcohol content by 1% (VAF Memstar, 2018[18]).

Agricultural methods: earlier harvesting can reduce the amount of sugar in grapes, and thus reduce the alcohol content of wine (OECD, 2015[4]). However, this also affects the flavour of the wine. Instead, growers can change the leaf area to fruit weight ratio: a high ratio leads to a greater production of sugar in the grapes. By reducing the leaf area, sugar production can be delayed while still allowing time for flavour and phenols to develop. This production of lower-sugar grapes requires manual labour for leaf removal. In addition, the method carries risks, as the optimal leaf to crop ratio needs to be found to prevent excessively delayed ripening (AWRI, 2020[19]; Schmidtke, Blackman and Agboola, 2012[15]).

Many alcohol policies are designed to reduce consumption of alcohol, and will therefore affect the earnings of the industry (Box 8.4). However, the impacts of policies on the industry can differ widely. For example, taxes can affect either sales or profits; price policies have different impacts on off-trade and on-trade vendors; minimum prices and reformulation may actually increase income for the industry; and a reduction in sales of alcohol products can lead to a reduction in sales of other products.

The survey of the Business at OECD network highlighted the following impacts of alcohol policies on sales and profits for the industry.

Advertising restrictions: The industry indicated that the impacts of advertising restrictions on income are unclear and mixed, as they depend on the type of restriction, a partial or total ban, the size of the business and the maturity of the market. Respondents noted that the rise of digital media offers a solution to inadvertent advertising exposure, because it enables detailed audience segmentation. In the short term, the industry expected to see a reduction in market competition as a result of advertising policies, which may make it easier for market leaders to entrench their position relative to small producers and/or market entrants. In the long term, the industry noted that the premiumisation potential may be diminished.

Regulation on sales of alcohol: The wide range of potential restrictions under this umbrella means that the impact on income is variable, although the industry expected reduced profitability. However, respondents noted that for off-trade restrictions on hours, consumers adjust shopping behaviour after about two months, meaning that sales are not affected in the long term, other than a two‑month dip. On-trade consumption was deemed harder to substitute, and the industry therefore thought that restrictions on this type of sales may result in consumers switching to drinking at home or reduced sales.

Reformulation: Reformulation was considered a potentially profitable venture by the industry, but respondents emphasised that it would be important to create the conditions that permit and encourage reformulation. While the industry saw a sales potential for new no- or low-alcohol variants, it noted that this depends on consumer acceptance of the products: if a reformulation is rejected, sales will decrease.

Taxes: The industry indicated that alcohol tax rate increases always harm profitability, but the extent to which this happens depends on the pass-through rate (the amount of tax passed on to consumers), the size of the tax rate increase and the relative tax rate increase across categories of alcohol, as well as the change in price and the responsiveness of consumers. It was noted that the impact on any company also depends on its product portfolio and geographical spread.

MUP: According to the industry, if minimum prices target the lowest-priced products, sales of premium products may benefit from the reduction in sales of lower-priced products. It was noted that there may be additional margin to be gained from the higher price, but who benefits depends on where the minimum price is set across different transactional stages (between producer and retailer, or between retailer and consumer). Illicit or cross-border trade may also change the impact that minimum prices have on income for the alcohol industry.

Source: Business at OECD response to OECD alcohol industry survey, April 2020.

The impact of taxation on alcohol producers and vendors is strongly dependent on the amount of tax they decide to pass on to consumers through higher prices – the pass-through rate (Box 8.5). If the tax is not passed on to the consumer in the form of a price increase, the producer or vendor will have to cover the cost, reducing their profit margin. However, if the industry passes on the tax in the form of a price increase, it has the effect of lowering sales. Therefore, the pass-through rate can either increase the cost for the industry or reduce sales.

In general, the more consumers reduce their consumption in response to a price increase (i.e. the more price‑elastic the product is), the less likely the industry is to pass on taxes (Rabinovich et al., 2012[3]). The competitiveness of the market plays a role as well, as companies operating on small profit margins will be less able to absorb the additional costs. The extent to which the tax is passed through to the customer will also depend on negotiation between the producers and vendors (Leicester, 2011[7]). This in turn will depend on the relative bargaining power of these two players, as well as their assessments of price elasticity.

The industry does not automatically respond to a USD 1 alcohol tax with a USD 1 price increase. Instead, producers and vendors can decide to keep the price the same or only pass on a portion of the tax. There are even cases of “over-shifting”, where the price is increased by more than the value of the tax (Ally et al., 2014[20]; Shrestha and Markowitz, 2016[21]). Pricing policies such as MUP (see Section 6.3.2 in Chapter 6) can be used to avoid the industry absorbing tax costs.

Overall, there exists a complex and heterogeneous pattern of pass-through rates for alcohol taxes (OECD, 2015[4]). The rates have been shown to vary by product, country, vendor and price point:

A study of pass-through rates in Ireland, Finland, Latvia and Slovenia found that, on average, a EUR 1 (USD 1.1) increase in the excise duty on beer resulted in a EUR 0.83 (USD 0.92) increase in the price of beer, but a EUR 0.94 (USD 1.04) increase in the price of vodka (Rabinovich et al., 2012[3]).

However, these effects were not homogeneous across countries. While only half the off-licence beer taxes in Ireland were passed on to consumers, off-licence beer taxes in Slovenia resulted in a price increase of 2.5 times the original tax (Rabinovich et al., 2012[3]).

A UK study found that the pass-through ratio was lower for cheaper products than for higher-priced products. For example, only 85% of taxes on the cheapest beers were passed on to the consumer, while the most expensive beers charged 114% of the tax (Ally et al., 2014[20]).

The same study also found differences across product groups: beers saw the smallest increase in price, possibly reflecting the importance of this product group in promotions and price competition (Ally et al., 2014[20]). A full pass-through of taxes was more common for wine, which the authors suggested was because customers tend to buy wine at different price points and are less loyal to specific brands.

The industry has raised the possibility of policy-makers introducing different tax rates based on the alcohol level of beverages, to encourage reformulation (see Box 8.3). In the case of taxes on sugar-sweetened beverages, there have been examples of tiered tax rates driving reformulation and lowering the sugar content of drinks (Bandy et al., 2020[22]). However, there is currently little evidence on whether the same would work for alcoholic beverages, although one study found that a tax based on the volume of pure alcohol in South Africa led to a significant shift in advertising from higher-alcohol to lower-alcohol beers (Blecher, 2015[23]).

Just as some policies – such as sales restrictions – affect off-trade and on-trade vendors differently depending on their design, so do price policies. For alcohol vendors, taxation is likely to have a greater impact on off-trade than on-trade sales, as price elasticity is generally greater in the off-trade market (Collis, Grayson and Johal, 2010[24]; Leicester, 2011[7]). There are a number of reasons for this: a consumer may have a greater choice between brands in an off-licence vendor, increasing the importance of price; consumers of on-licence alcohol vendors have already accepted paying a higher price for the experience of drinking out; and on-licence traders charge a service mark-up, making the added tax proportionally less.

Minimum prices are unlikely to have a major impact on on-licence vendors. Studies have found that on-licence prices are between two and four times higher than for the off-licence market (Rabinovich et al., 2012[3]). As a result, prices charged in cafés and restaurants will generally be above any minimum threshold (Department of Health, 2016[25]). A study for the Welsh Government showed that only 0.2‑3.4% of on-trade sales charged less than GBP 0.50 (USD 0.60) per alcohol unit – depending on the type of drink (Angus et al., 2017[26]).

The impact of minimum prices will therefore be primarily on off-licence trade, where the lowest prices are charged for alcohol. Beer, cider and spirits in particular can be affected. For example, in the United Kingdom (Wales), 61.7%, 73.1% and 60.4% of off-licence sales cost less than GBP 0.50 (USD 0.60) per unit, respectively (Angus et al., 2017[26]). Depending on the level of the minimum price, it may reduce the difference between off- and on-licence prices and encourage consumers to switch to on-licence use (Leicester, 2011[7]).

Minimum prices can be expected to benefit sales of premium brands: the increase in price for products at the low end reduces the price gap with higher-priced, premium products, making them more attractive. However, minimum prices may also have a positive effect on revenues of producers of low-priced products. Unlike taxes, increased income from minimum prices remains with the industry. It has been estimated that, if there is no behavioural response to a minimum price of GBP 0.45 (USD 0.55) per unit, producers and retailers could expect an extra GBP 1.4 billion (USD 1.7 billion) in revenue in the United Kingdom (Leicester, 2011[7]).

Even if consumption of products subject to the minimum price decreases, the higher price charged may partly or completely offset the losses in sales. An impact assessment of minimum alcohol prices in Ireland noted that revenue to retailers is estimated to increase at any minimum unit price (Department of Health, 2016[25]). Another study estimated that a GBP 0.45 (USD 0.55) minimum price per unit of alcohol in the United Kingdom (England) would actually increase revenue for the off-trade sector by 5.6% (Brennan et al., 2014[27]). A study for the Welsh Government looking at a minimum price per unit of GBP 0.50 (USD 0.60) showed a decrease in consumption of 3.6% across the population (with, importantly, the greatest effect among harmful drinkers) but a 1.4% increase in spending (Angus et al., 2017[26]).

Recent years have seen a considerable increase in availability and sales of alcohol-free or lower-alcohol products (de Bruijn, van den Wildenberg and van den Broeck, 2012[28]; Brányik et al., 2012[13]). In Denmark, sales of low-alcohol and non-alcoholic beer increased by 2 100% between a low in 2008 and 2015 (Statista, 2019[29]). In Germany, the number of people consuming alcohol-free beer increased from 5.9 million in 2012 to 9.8 million in 2016 (Statista, 2020[30]).

The market for lower-alcohol products is expected to continue to increase considerably in the next few years: the global market for low-alcohol beer is predicted to grow by 7.9% every year between 2016 and 2021 and for low-alcohol wine by 5.4% each year (Statista, 2016[31]). This growing demand for lower-alcohol products presents an important sales opportunity for producers.

Product sales may be reduced if the lower-alcohol product replaces the original and has lower consumer acceptance. For example, it was argued that lower-alcohol beers might have an immature flavour profile, and foam less (Sohrabvandi et al., 2010[14]). However, if lower-alcohol versions are included in the brand portfolio as a line extension rather than a replacement, this can be avoided.

The lower calorie content of lower-alcohol beverages can be used as a way to market these products to people who are watching their weight (Jones and Bellis, 2012[32]). The New Zealand industry initiative aimed at developing lower-alcohol wines is marketed as “Lighter Wines”, with a focus on the lower calorie content of the wine (Miller, 2017[33]).

The rise in demand for lower-alcohol beverages can create a new revenue stream for vendors as well as producers. As part of the United Kingdom’s Public Health Responsibility Deal, a supermarket chain increased its range, space and marketing of lower-alcohol products, and saw sales grow by 135%, doubling the low-alcohol market share from 12.8% to 24.8% (Department of Health, 2014[34]). The same could apply to on-trade alcohol vendors. Anecdotal evidence suggests that pubs offering a wider range of low- or non-alcoholic drinks turned the tide on the “dry January” slump and had record sales (Walker, 2017[35]).

In addition to changing the sales of alcohol products, some alcohol policies can also affect the sales of other, non-alcohol products. A prohibition on the sale of alcohol products for a specific vendor may affect their ancillary sales, where alcohol is used as a loss leader – a product sold at a loss to attract customers – or sold to create a one‑stop-shop convenience. A trade‑sponsored report describes how allowing wine sales at food stores can increase sales of other products, as consumers who buy wine spend on average USD 20 more in addition to the wine (FMI, 2012[36]).

To capitalise on this effect, some off-licence vendors use cheap alcohol as a loss leader. In fact, the ban on below-cost sales discussed by the UK Government was in part developed to target this practice (IAS, 2019[37]). Supermarkets in the United Kingdom admitted to selling some alcohol products at less than wholesale prices to tempt customers to come into the store (Competition Commission, 2008[38]). The same supermarkets also indicated that they sold alcohol at below cost to be able to compete with other vendors. In this case, minimum pricing may have a positive financial benefit for the industry, as bans on below-cost sales and other minimum pricing policies can prevent unfair competitive practices by large retailers (OECD, 2015[4]).

In addition to company-level impacts such as implementation costs and changes in sales, alcohol policies can also change the industry as a whole. Stricter regulations on price or availability may lead to an increase in unrecorded alcohol sales, such as illicit sales or cross-border trade. Policies that affect the alcohol industry can have consequences for employment in this sector. These two impacts are further discussed below.

In addition, other alcohol policies such as advertising restrictions may also have an industry-level impact on competition between companies. In particular, smaller companies and new entrants may be affected by this. However, it is difficult to make any generalised statements on this topic, as the impacts will greatly depend on the competitive landscape and alcohol market in each country, as well as the specifics of the policy. Nevertheless, previous OECD work recommends that policy-makers should consider how their regulations affect the competitive process (OECD, 2020[5]).

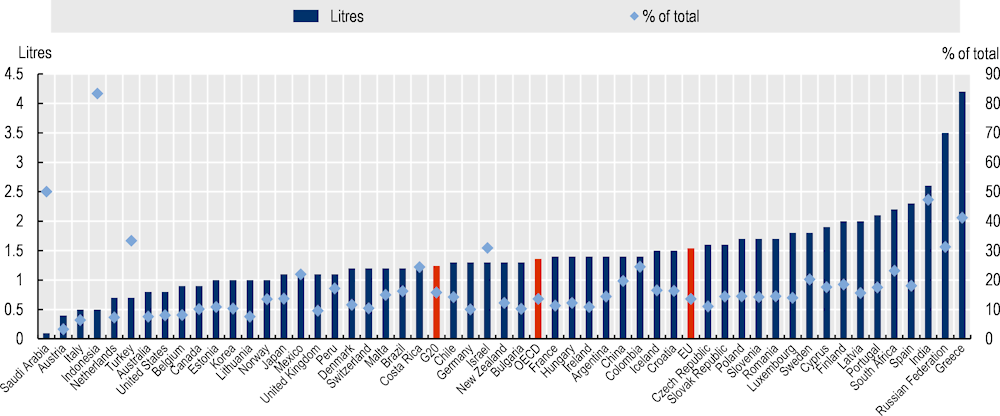

Unrecorded alcohol can be defined as all alcohol products that are not taxed and are outside the usual system of governmental control (WHO, 2020[39]). This includes homemade or informally produced alcohol (legal or illegal), smuggled alcohol, surrogate alcohol (which is alcohol not intended for human consumption) and alcohol obtained through cross-border shopping. The total amount of unrecorded alcohol consumption is, by definition, hard to measure, but it is estimated that people in OECD countries consume on average 1.4 litres of unrecorded alcohol per person, per year (Figure 8.2).

Unrecorded per capita (15+) alcohol consumption (in litres of pure alcohol and as a percentage of total consumption), three‑year average, 2016‑18

Source: OECD analysis of WHO (2020[40]), Global Information System on Alcohol and Health (GISAH), https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/global-information-system-on-alcohol-and-health.

Markets with the highest excise taxes tend to have greater problems with illicit trade. Since taxation raises the price of alcohol products, the financial rewards for those who avoid paying the taxes can be large (OECD, 2016[41]). Other policies, such as those restricting the sale of alcohol products at certain times or places, could make illicit products seem more convenient or more available (Neufeld et al., 2019[42]). Ineffective enforcement of policies – including inadequate penalties for activities related to illicit alcohol and corruption – also play a role in enabling illicit trade of alcohol products (TRACIT, 2020[43]).

In addition to reducing income for the industry, illicit sales avoid tax; this has a negative effect on government revenues (OECD, 2016[41]). In the European Union (EU27), sales of counterfeit wine and spirits were estimated to result in an annual loss of EUR 2.7 billion for the industry and of EUR 2.2 billion in tax revenue and reduced social security contributions for governments (EUIPO, 2018[44]).

Where taxes or regulations are introduced in only one country, or where they are significantly higher or stricter in one than in other countries, this may contribute to an increase in cross-border trade – where people travel to a neighbouring country to buy certain products. Cross-border trade is driven by differences in the type of products on sales, their relative prices, and the time and money required to travel across the border (Karlsson and Österberg, 2009[45]). Policies that restrict the availability or increase the price of alcohol products in only one country can increase cross-border trade with neighbouring countries without such regulation (see Box 8.6).

The impact of high tax rates on cross-border trade can clearly be seen in the EU27, where the single market facilitates cross-border shopping (OECD, 2015[4]). When Estonia – with its low alcohol taxes – joined the EU, several Nordic countries reduced their high tax rates to prevent cross-border shopping. Finland was one of them, reducing the excise duty rate by an average of 33% (Karlsson et al., 2020[46]; Koski et al., 2007[47]). However, the country consequently noted an increase in consumption, as well as a 17% increase in alcohol-positive deaths (mortality cases where a post-mortem revealed a blood alcohol concentration of 0.20 mg/g or higher) (Koski et al., 2007[47]). As a result, Finland increased tax rates by 10% in 2008, and several more times in later years (Karlsson et al., 2020[46]). In 2017, “traveller imports” were estimated to account for 18% of all alcohol consumption in Finland.

In 2015, Estonia adopted a policy that would increase alcohol taxes by 10% each year between 2016 and 2020 – a move welcomed by Finnish health officials (Yle Uutiset, 2015[48]). Subsequently, in 2017, alcohol taxes for all beverages rose by 10%, with an additional 70% increase for beer in July (a further 18% increase was planned for February 2018). The tax increase led to marked differences in alcohol prices between Estonia and Latvia (up to 200% for certain beverages), which fuelled cross-border purchases between these countries. In 2019, the new Estonian Government announced plans to lower the excise tax on alcohol by 25% in an effort to curb cross-border trade with Latvia, where the tax rate is lower (International, 2019[49]; ERR, 2019[50]).

Changes in alcohol sales may also have consequences for the economy through their impact on employment (Box 8.7). A reduction in revenue or profits for the alcohol industry – as a result of price policies or any other policy aimed at reducing alcohol consumption – could reduce employment in this sector. However, some evidence shows that employment in other sectors may grow.

The survey of the Business at OECD network highlighted the following impacts of alcohol policies on employment.

Advertising restrictions: Respondents expected that advertising restrictions would reduce employment of advertisers (either in-house or contracted), although this may vary depending on the type of media and the possibility that alternative advertisers may buy any additional media space in lieu of alcohol companies.

Regulation on sales of alcohol: The industry expected a reduction in employment at retailers whose sales are affected by the restrictions.

Reformulation: The industry felt that reformulation could potentially increase employment, as R&D requires employment and new no‑alcohol formulations can create new drinking occasions without adding to harmful use of alcohol.

Taxes: Respondents noted that taxes can reduce sales, which may also affect jobs in distribution and retail. However, it was mentioned that shifts in employment can occur when demand shifts to other categories or other geographies.

Source: Business at OECD Response to OECD alcohol industry survey, April 2020.

When considering the impact of alcohol policies on the wider economy, it is important to look at the total net effect on employment. While lower alcohol consumption may result in a loss of employment in the alcohol industry, displacement of demand and jobs could cause employment in other industries to grow (IAS, 2017[51]).

For example, one study suggested that a potential small decrease in jobs in the Australian wine industry as a result of volumetric wine taxes (between 0.5% and 6.8% of total employment, depending on the tax scenario) could be met with an increase in employment in the industries taking over the irrigated regions formerly used for vines (Fogarty and Jakeman, 2011[52]).

In addition to a growth in replacement industries, employment losses in the alcohol industry may also be offset by employment growth in other industries as a result of the reinvestment of excise tax income. One study modelling reinvestment of the additional revenue generated through an alcohol tax showed an increase in overall employment (Wada et al., 2017[53]). The study considered the impact of two hypothetical alcohol tax increases (a USD 0.05 per drink excise tax increase and a 5% sales tax increase on beer, wine, and distilled spirits) on employment in the US states of Arkansas, Florida, Massachusetts, New Mexico and Wisconsin, taking into account changes in alcohol demand, average state income and substitution effects. Results from the analysis found a USD 0.05 per drink tax increase would lead to a net increase of 8 183 jobs across the five states analysed, with this figuring declining to 7 792 when introducing a 5% sales tax. In percentage terms, gains in net employment are relatively small, representing between 0.014% and 0.089% of overall employment, depending on the type of tax and state.

A modelling study looking at the United Kingdom found similar results: if the government proceeds of a theoretical 10% increase in alcohol tax are used to increase spending on public services, there would be over 17 000 more full-time equivalent jobs. In addition, gross value added would increase by GBP 847 million (USD 1 039 million) (Connolly et al., 2019[54]).

It is important to note that the evidence regarding alcohol policies and employment is mostly limited to modelling studies. Moreover, these studies primarily look at the impact of taxes on trade in various industries, and do not take into account the health impacts of reduced alcohol consumption, which also affect employment. Finally, some studies suggest that there may be friction costs in the short term, which can include time off work between jobs and the costs of hiring and (re)training (Kigozi et al., 2016[55]).

Implementation of more stringent policies aimed at curbing alcohol consumption may have an impact on other sectors of the economy and associated industries. This section extends the previous analysis in this chapter by examining the potential impact of alcohol policies on other industries, using household expenditure data. Specifically, it analyses the share of household budget that is devoted to purchasing alcohol and compares spending habits between households who do and do not purchase alcohol. This will facilitate better understanding of how households may reallocate expenditure in response to a reduction in alcohol purchases. The analysis is of 19 European countries and the United States (see Annex 8.A for further details).

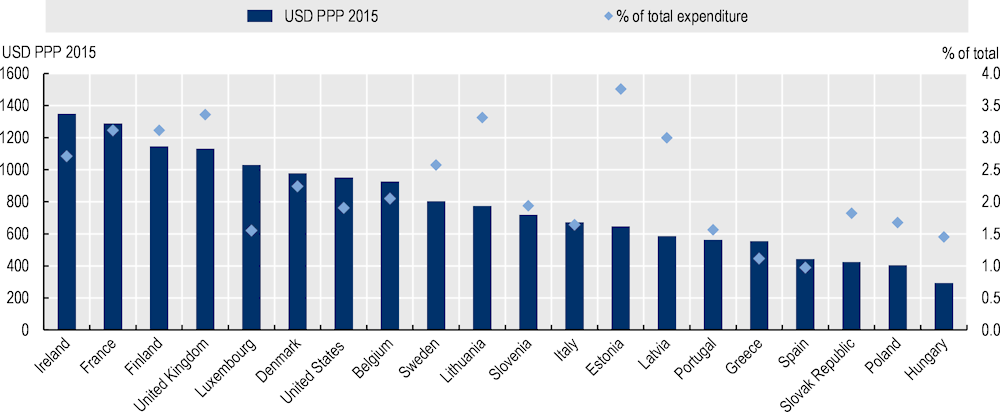

Figure 8.3 examines alcohol expenditure by country for alcohol-purchasing households only (i.e. households who recorded positive spending on alcohol). The results show that households across 19 European countries and the United States spent USD PPP 294‑1 349 on alcohol in 2015, or around 1.0‑3.4% of their total budget. A policy-induced reduction in alcohol purchases could encourage alcohol-purchasing households to switch consumption to other goods and services. For example, a reduction in purchases equal to 10% would make available an additional USD PPP 29 per household in Hungary and up to USD PPP 135 per household in Ireland, which could be reallocated to other industries.

Note: A full list of items in each expenditure category can be found in Classification of Individual Consumption According to Purpose (COICOP) 2018 (UNSD, 2018[56]). Average expenditure for each category was weighted using provided survey weights so that findings represent the reference population and thereby minimise bias. Data for the figure were prepared by the OECD team in charge of the “Drivers and Trends of Growing Inequalities” Project.

Source: European Household Budget Survey (2010) and Household Consumer Expenditure Survey data collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

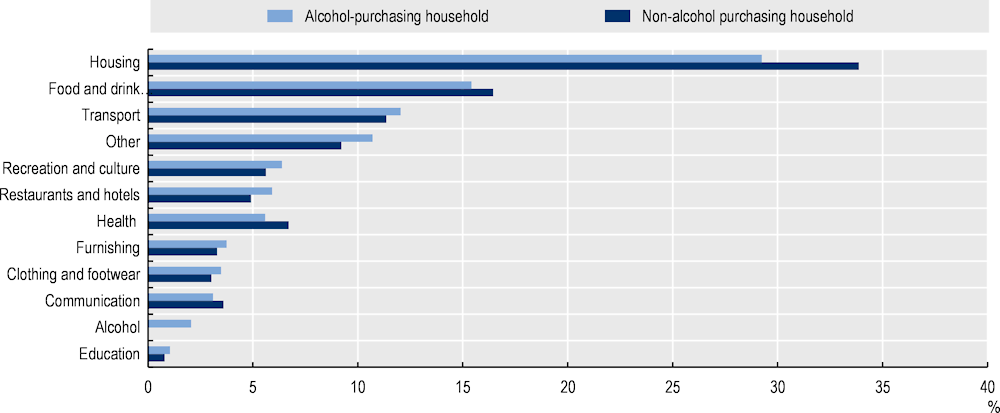

Figure 8.4 suggests how the additional household budget resulting from reductions in alcohol purchases may be reallocated. The figure shows household expenditure bundles for all countries, according to whether the household purchases or does not purchase alcohol (i.e. whether alcohol expenditure is above zero or not). The results indicate that alcohol-purchasing households spend a higher proportion of total expenditure on discretionary (non-essential) items (ONS, 2017[57]), such as restaurants and hotels (5.9% vs. 4.9%) and recreation and culture (6.4% vs. 5.6%). Since discretionary items are more responsive to changes in income (i.e. they have higher elasticity (Jääskelä and Windsor, 2011[58])), the findings suggest that a decrease in alcohol expenditure could be offset by additional expenditure on other discretionary goods.

Percentage of total household expenditure

Note: A full list of items in each expenditure category can be found in Classification of Individual Consumption According to Purpose (COICOP) 2018 (UNSD, 2018[56]). Average expenditure for each category was weighted using provided survey weights so that findings represent the reference population and thereby minimise bias. Data for the figure were prepared by the OECD team in charge of the “Drivers and Trends of Growing Inequalities” Project.

Source: European Household Budget Survey (2010) and Household Consumer Expenditure Survey data collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Implementation of policies to tackle harmful alcohol use has an impact on the alcohol industry. At the company level, alcohol producers and off- and on-trade vendors may face implementation costs, from those associated with redesigning their marketing strategy to those for developing and using techniques to reduce the alcohol content of their products. Alcohol policies can also have an impact on their income, reducing profit or sales. On the other hand, minimum prices can increase profits for the industry, and sales can be increased by responding to the market demand for lower-alcohol products. At the industry level, alcohol policies in one country can increase cross-border trade with neighbouring countries. Employment in the alcohol industry may be negatively affected by policies aiming to reduce alcohol consumption, but this may be paired with increased employment in other industries.

Overall, costs to the industry are difficult to calculate, given the lack of publicly available data. Based on available information, the review did not find evidence indicating that costs to the industry outweigh costs associated with harmful alcohol consumption (such as disease‑related health expenditure and reduced labour productivity – see Chapter 4).

[20] Ally, A. et al. (2014), “Alcohol tax pass-through across the product and price range: Do retailers treat cheap alcohol differently?”, Addiction, Vol. 109/12, pp. 1994-2002, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/add.12590.

[26] Angus, C. et al. (2017), Model-based Appraisal of the Comparative Impact of Minimum Unit Pricing and Taxation Policies in Wales: Interim report, Welsh Government, Cardiff, https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2019-05/model-based-appraisal-of-the-comparative-impact-of-minimum-unit-pricing-and-taxation-policies-in-wales-interim-report-an-update-to-the-50p-mup-example.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2018).

[19] AWRI (2020), Reducing Ethanol Levels in Wine: Fact sheet, Australian Wine Research Institute, Adelaide, https://www.awri.com.au/wp-content/uploads/Reducing-ethanol-levels-in-wine.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2017).

[22] Bandy, L. et al. (2020), “Reductions in sugar sales from soft drinks in the UK from 2015 to 2018”, BMC Medicine, Vol. 18/1, p. 20, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1477-4.

[23] Blecher, E. (2015), “Taxes on tobacco, alcohol and sugar sweetened beverages: Linkages and lessons learned”, Social Science and Medicine, Vol. 136-137, pp. 175-179, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.05.022.

[13] Brányik, T. et al. (2012), “A review of methods of low alcohol and alcohol-free beer production”, Journal of Food Engineering, Vol. 108/4, pp. 493-506, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.JFOODENG.2011.09.020.

[27] Brennan, A. et al. (2014), “Potential benefits of minimum unit pricing for alcohol versus a ban on below cost selling in England 2014: Modelling study”, BMJ, Vol. 349, p. g5452, http://www.bmj.com/content/349/bmj.g5452 (accessed on 2 August 2017).

[24] Collis, J., A. Grayson and S. Johal (2010), Econometric Analysis of Alcohol Consumption in the UK, HM Revenue & Customs, London, https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/331614/alcohol-consumption-uk.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2017).

[38] Competition Commission (2008), The Supply of Groceries in the UK Market Investigation, The Stationery Office, London, http://www.ias.org.uk/uploads/pdf/Price%20docs/538.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2017).

[54] Connolly, K. et al. (2019), “Can a policy-induced reduction in alcohol consumption improve health outcomes and stimulate the UK economy? A potential ‘double dividend’”, Drug and Alcohol Review, Vol. 38/5, pp. 554-560, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/dar.12962.

[28] de Bruijn, A., E. van den Wildenberg and A. van den Broeck (2012), Commercial Promotion of Drinking in Europe, Dutch Institute for Alcohol Policy (STAP), Utrecht, http://www.drugsandalcohol.ie/17449/1/ammie-eu-rapport_final.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2017).

[25] Department of Health (2016), Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) Public Health (Alcohol) Bill, Department of Health, Dublin, https://assets.gov.ie/19454/b1990c163eaf454f9f674355eaf4d504.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2017).

[34] Department of Health (2014), Responsibility Deal Alcohol Network: Pledge to remove 1 billion units of alcohol from the market by end 2015 – First interim monitoring report, Department of Health, London, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/389573/RDAN_-_Unit_Reduction_Pledge_-_1st_interim_monitoring_report.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2017).

[50] ERR (2019), Bill Lowering Alcohol Excise Duty Submitted to Riigikogu, Eesti Rahvusringhääling, Tallinn, https://news.err.ee/946269/bill-lowering-alcohol-excise-duty-submitted-to-riigikogu (accessed on 22 August 2019).

[44] EUIPO (2018), Synthesis Report on IPR Infringement, European Union Intellectual Property Office, Alicante, http://dx.doi.org/10.2814/833376.

[10] European Commission (2019), Regulation (EU) 2019/787 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on the definition, description, presentation and labelling of spirit drinks, the use of the names of spirit drinks in the presentation and labelling of other foodstuffs, the protection of geographical indications for spirit drinks, the use of ethyl alcohol and distillates of agricultural origin in alcoholic beverages, and repealing Regulation (EC) No 110/2008, European Commission, Brussels, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32019R0787 (accessed on 29 April 2020).

[8] Federal Trade Commission (2014), Self-Regulation in the Alcohol Industry, Federal Trade Commission, Washington DC, https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/reports/self-regulation-alcohol-industry-report-federal-trade-commission/140320alcoholreport.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2017).

[36] FMI (2012), The Economic Impact of Allowing Shoppers to Purchase Wine in Food Stores, Food Marketing Institute, Arlington, VA, https://www.fmi.org/docs/gr-state/fmi_wine_study.pdf?sfvrsn=2 (accessed on 26 October 2017).

[52] Fogarty, J. and G. Jakeman (2011), “Wine tax reform: The impact of introducing a volumetric excise tax for wine”, Australian Economic Review, Vol. 44/4, pp. 387-403, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8462.2011.00653.x.

[11] FSANZ (2020), Proposal P1050: Pregnancy warning labels on alcoholic beverages, Food Standards Australia New Zealand, Canberra, https://www.foodstandards.gov.au/code/proposals/Pages/P1050Pregnancywarninglabelsonalcoholicbeverages.aspx.

[17] Goldfarb, A. (2007), Cutting the Alcohol in Wine: What wineries don’t want you to know, AppellationAmerica.com, Santa Rosa, CA, http://wine.appellationamerica.com/wine-review/305/Alcohol-Reduction-in-Wine.html (accessed on 25 January 2018).

[16] Goode, J. (2009), Lower Alcohol Wines: A new retail category, WineAnorak.com, London, http://www.wineanorak.com/loweralcoholwines.htm.

[37] IAS (2019), Price, Institute of Alcohol Studies, London, http://www.ias.org.uk/Alcohol-knowledge-centre/Price.aspx (accessed on 1 August 2017).

[2] IAS (2018), The Alcohol Industry: Factsheet, Institute of Alcohol Studies, London, http://www.ias.org.uk/uploads/pdf/Factsheets/FS%20industry%20012018.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2019).

[51] IAS (2017), Splitting the Bill: Alcohol’s impact on the economy, Institute of Alcohol Studies, London, http://www.ias.org.uk/uploads/pdf/IAS%20summary%20briefings/sb15022017.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2018).

[49] International, M. (2019), Estonia: New Government Plans to Lower Alcohol Tax, Movendi International, Stockholm, https://iogt.org/news/2019/05/28/estonia-government-plans-to-lower-alcohol-tax/ (accessed on 22 August 2019).

[58] Jääskelä, J. and C. Windsor (2011), “Insights from the household expenditure survey”, Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, pp. 1-12, https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2011/dec/pdf/bu-1211-1.pdf.

[32] Jones, L. and M. Bellis (2012), Can Promotion of Lower Alcohol Products Help Reduce Alcohol Consumption? A rapid literature review, North West Public Health Observatory, Liverpool, https://ranzetta.typepad.com/files/can-promotion-of-lower-strength-alcohol-products-help-reduce-alcohol-consumption-jmu-2012.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2017).

[46] Karlsson, T. et al. (2020), “The road to the Alcohol Act 2018 in Finland: A conflict between public health objectives and neoliberal goals”, Health Policy, Vol. 124/1, pp. 1-6, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.10.009.

[45] Karlsson, T. and E. Österberg (2009), Alcohol Affordability and Cross-border Trade in Alcohol, Swedish National Institute of Public Health, Östersund.

[55] Kigozi, J. et al. (2016), “Estimating productivity costs using the friction cost approach in practice: A systematic review”, European Journal of Health Economics, Vol. 17/1, pp. 31-44, http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10198-014-0652-y.

[47] Koski, A. et al. (2007), “Alcohol tax cuts and increase in alcohol-positive sudden deaths: A time-series intervention analysis”, Addiction, Vol. 102/3, pp. 362-368, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01715.x.

[7] Leicester, A. (2011), Alcohol Pricing and Taxation Policies, Institute for Fiscal Studies, London, https://www.ifs.org.uk/bns/bn124.pdf (accessed on 1 August 2017).

[33] Miller, D. (2017), Lighter Wines: A major industry initiative – A progress review of the Lighter Wines PGP Programme, MInistry for Primary Industries, Wellington, https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/21904-Lighter-Wines-progress-review-report- (accessed on 23 October 2017).

[12] Ministry for Primary Industies (2017), Lighter Wines, Ministry for Primary Industies, Wellington, https://www.mpi.govt.nz/funding-rural-support/primary-growth-partnerships-pgps/current-pgp-programmes/lighter-wines/ (accessed on 5 September 2017).

[42] Neufeld, M. et al. (2019), “Perception of alcohol policies by consumers of unrecorded alcohol: An exploratory qualitative interview study with patients of alcohol treatment facilities in Russia”, Substance Abuse: Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, Vol. 14/1, p. 53, http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13011-019-0234-1.

[9] Noel, J., T. Babor and K. Robaina (2016), “Industry self-regulation of alcohol marketing: a systematic review of content and exposure research”, Addiction, Vol. 112, pp. 28-50, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/add.13410.

[59] OECD (2020), Inflation (CPI), OECD, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/54a3bf57-en.

[60] OECD (2020), Purchasing Power Parities (PPP), OECD, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/1290ee5a-en (accessed on 20 July 2020).

[5] OECD (2020), Regulatory Impact Assessment, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/7a9638cb-en.

[41] OECD (2016), Illicit Trade: Converging Criminal Networks, OECD, Paris, http://www.oecd.org/corruption-integrity/reports/charting-illicit-trade-9789264251847-en.html.

[4] OECD (2015), Tackling Harmful Alcohol Use: Economics and Public Health Policy, OECD, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264181069-en (accessed on 26 July 2017).

[57] ONS (2017), Family Spending in the UK: Financial year ending March 2016, Office for National Statistics, London, https://www.ons.gov.uk/releases/familyspendingintheuk2016.

[3] Rabinovich, L. et al. (2012), Further Study on the Affordability of Alcoholic Beverages in the EU, RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, https://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/alcohol/docs/alcohol_rand_2012.pdf (accessed on 2 August 2017).

[6] Ross, C., A. Sparks and D. Jernigan (2016), “Assessing the impact of stricter alcohol advertising standards: The case of Beam Global Spirits”, Journal of Public Affairs, Vol. 16/3, pp. 245-254, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/pa.1584.

[15] Schmidtke, L., J. Blackman and S. Agboola (2012), “Production technologies for reduced alcoholic wines”, Journal of Food Science, Vol. 77/1, pp. R25-R41, http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3841.2011.02448.x.

[21] Shrestha, V. and S. Markowitz (2016), “The pass-through of beer taxes to prices: Evidence from state and federal tax changes”, Economic Inquiry, Vol. 54/4, pp. 1946-1962, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecin.12343.

[14] Sohrabvandi, S. et al. (2010), “Alcohol-free beer: Methods of production, sensorial defects, and healthful effects”, Food Reviews International, Vol. 26/4, pp. 335-352, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/87559129.2010.496022.

[30] Statista (2020), Number of Persons Consuming Alcohol-free Beer in Germany from 2016 to 2020, Statista, New York, https://www.statista.com/statistics/575433/non-alcoholic-beer-consumption-germany/ (accessed on 30 October 2017).

[29] Statista (2019), Average Household Consumption Expenditure on Low and Non-alcoholic Beer in Denmark from 2008 to 2018, Statista, New York, https://www.statista.com/statistics/604681/annual-household-expenditure-on-non-alcoholic-beer-in-denmark/.

[31] Statista (2016), Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of Low-alcohol Beverages Worldwide Between 2016 and 2021, by Category, Statista, New York, https://www.statista.com/statistics/753790/cagr-low-alcohol-drinks-category-worldwide/ (accessed on 30 October 2017).

[43] TRACIT (2020), Mapping the Impact of Illicit Trade on the Sustainable Development Goals, Transnational Alliance to Combat Illicit Trade, New York, https://www.tracit.org/publications_illicit-trade-and-the-unsdgs.html (accessed on 28 April 2020).

[56] UNSD (2018), Classification of Individual Consumption According to Purpose (COICOP) 2018, United Nations Statistics Division, New York, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/classifications/unsdclassifications/COICOP_2018_-_pre-edited_white_cover_version_-_2018-12-26.pdf.

[18] VAF Memstar (2018), Winemakers’ Questions, VAF Memstar, Nuriootpa, https://www.vafmemstar.com.au/about/faqs/#toggle-id-3 (accessed on 25 January 2018).

[53] Wada, R. et al. (2017), “Employment impacts of alcohol taxes”, Preventive Medicine, Vol. 105, pp. S50-S55, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.YPMED.2017.08.013.

[35] Walker, R. (2017), “Forget the hangover, under-25s turn to mindful drinking”, Observer, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/feb/26/under-25s-turn-to-mindful-drinking (accessed on 30 October 2017).

[39] WHO (2020), Alcohol, Unrecorded Per Capita (15+ years) Consumption (in litres of pure alcohol), World Health Organization, Geneva, https://www.who.int/data/gho/indicator-metadata-registry/imr-details/466 (accessed on 10 February 2020).

[40] WHO (2020), Global Information System on Alcohol and Health (GISAH), World Health Organization, Geneva, http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.GISAH?lang=en (accessed on 12 November 2019).

[1] WHO (2010), Global Strategy to Reduce the Harmful Use of Alcohol, World Health Organization, Geneva, http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44395/1/9789241599931_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 (accessed on 26 July 2017).

[48] Yle Uutiset (2015), Finnish Health Officials Laud Estonian Booze Tax Hike Plan, Yle Uutiset, Helsinki, https://yle.fi/uutiset/osasto/news/finnish_health_officials_laud_estonian_booze_tax_hike_plan/7917415 (accessed on 20 October 2017).

Expenditure patterns were analysed for 19 European countries, which were chosen based on data availability. Data were retrieved from each country’s 2010 household budget survey micro-dataset, which includes expenditure on 12 key items including food and drink, clothing and footwear, health, transport, recreation and culture, and hotels (i.e. the United Nation’s classification of individual consumption by purpose (COICOP)).

The following European countries were analysed: Belgium, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

Micro-data for the United States came from the 2015 household Consumer Expenditure Survey collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Expenditure bundles were re‑classified to align with the United Nation’s COICOP.

To ensure data comparability across countries, expenditure items and household disposable income were inflated to 2015 values using individual consumer price index values (OECD, 2020[59]). Once inflated, they were converted to USD PPP using PPP conversation rates (OECD, 2020[60]). To ensure that the results represented the entire population, as opposed to the surveyed population, they were adjusting using survey weights.