Continental integration is central to Africa’s vision of a prosperous and industrialised continent, as elaborated in the African Union’s Agenda 2063. The creation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is an important step forward, building on decades of integration efforts. This chapter gives a snapshot of progress towards implementing the AfCFTA, focusing on the structure of the agreement, state of negotiations, and emerging governance.

Production Transformation Policy Review of Egypt

1. Africa has advanced in fostering continental integration

Abstract

Africa is home to nearly 17% of the world’s population but is still a small player in global production and trade. The continent accounted for just 2% of world manufacturing value added and 2.4% of exports during 2019-21 (authors’ calculations based on (UNCTAD, 2023[1])). Even though Africa’s economies are far from homogeneous, they tend to be overwhelmingly anchored in commodities reducing opportunities for learning and innovation. Primary goods represent more than 70% of all exports for the majority of countries in Africa – 42 of them. Such long-standing structural challenges have been magnified in recent years as disruptions due to the COVID-19 pandemic stressed supply chains and threatened the flow of critical goods, including food and medicines. In addition, the ongoing energy crisis has eroded gains in living standards against a backdrop of heightened geopolitical tensions.

Africa remains committed to the vision of a prosperous and industrialised continent. The African Union’s (AU) Agenda 2063: The Africa We Want, has set out a vision for transforming the continent into a united, and global powerhouse, reaffirming the importance of industrialisation, in line with the Action Plan for Accelerated Industrial Development for Africa (AIDA) and the Third Industrial Development Decade for Africa (IDDA3). One of the key goals of this agenda is to further integrate goods, services, capital and people, with a view to strengthening resilience and the capacity of the continent to determine its own future. The creation of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is an important step forward. The first chapter of this report discusses how AfCFTA has advanced continental efforts in fostering continental integration.

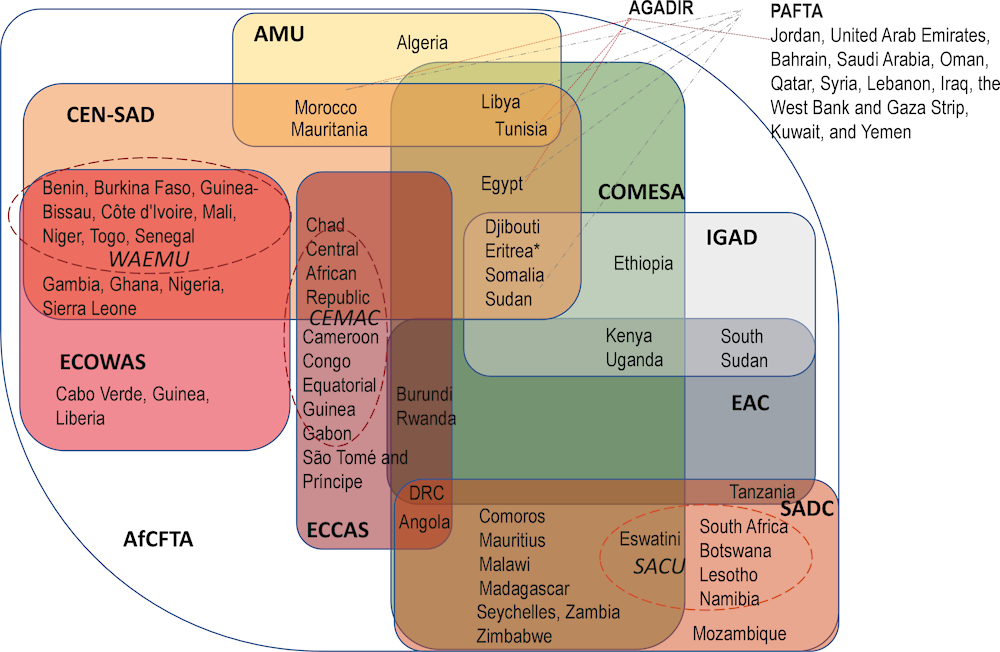

Continental integration efforts in Africa have a long history, dating back to the 1980 Lagos Plan of Action for the Development of Africa and the Abuja Treaty of 1991. The Regional Economic Communities (RECs)1 that have been created since then aim to facilitate integration on a regional scale with a view to eventually connecting the entire continent (Figure 1.1). RECs developed differently over time and have experienced different levels of integration and scope. For example, COMESA, EAC, ECOWAS and SADC have developed an FTA, while there are also additional customs and monetary unions developed, such as that of EAC, the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC), the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU) and the Southern African Customs Union (SACU). North African countries have also developed ties with non-African regional markets through agreements such as the Pan-Arab Free Trade Area and Agadir. This process has led to a fragmented landscape of integration on the one hand, with different rules and processes taking hold in different regions and overlapping memberships that can create a complex landscape for exporters, on the other. The COMESA-EAC-SADC Tripartite FTA (TFTA) was meant to serve as an important step towards bringing some of these different frameworks together and advance towards continental integration. It was launched in 2015 but progress was delayed as attention shifted to the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), which launched negotiations shortly thereafter. As of March 2023, 11 members had ratified the TFTA, only three short of the minimum needed for the agreement to enter into force.

Figure 1.1. Regional preferential trade agreements where African countries participate, 2022

Note: Chart includes the eight Regional Economic Communities (RECs) recognised by the AU, the Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD), Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), East African Community (EAC) Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS) Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), Southern African Development Community (SADC), Arab Maghreb Union (AMU); Monetary unions that have developed within RECs, Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa (CEMAC); Southern African Customs Union (SACU); West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU); and other regional agreements with multiple African country members, such as Pan-Arab FTA (PAFTA) and Agadir.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on official information.

Despite efforts to encourage intra-African trade, African countries trade little with each other, exporting instead commodities to the world and importing manufactures to feed an expanding market. Intra-regional trade in Africa stands at 15%,2 three percentage points higher than during 2000-02, and in the same level as that of Latin America and the Caribbean, but much lower than in Europe (61%) and Asia (59%) (Figure 1.2). Asia is a major partner for the continent when it comes to extra-African trade. The People’s Republic of China (hereinafter “China”) absorbs about 15% of all continental exports, followed by India (7%), the US and Spain (6%), while similarly China accounts for about 18% of continental imports, followed by France, India and the United States with about 5% of exports each (authors’ elaboration based on (UNCTAD, 2023[1])).

Boosting intra-African trade could expand options for industrialisation. Africa’s trade with the world shows a different pattern of trade. Primary products make up 63% of the products Africa trades with outside partners, reflecting a long-held pattern of specialisation in commodities and agriculture. Petroleum and gas alone account for around 34% of all African exports, while top import items span more technologically sophisticated and capital-intensive goods, such as automotive products and electronics (9% and 8% each) and pharmaceuticals (4%), as well as food and cereals (5%). By contrast, the share of primary exports drops to half when African countries trade with each other (30%) (ibid.).

Figure 1.2. Intra-African exports as a share of total and their technological intensity, 2020-22

Note: Panel B: Lall classification. Unclassified products not included in total. LAC: Latin America and the Caribbean.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on (UNCTAD, 2023[1]), Unctadstat, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/.

AfCFTA holds promise to strengthen continental trade, by creating the biggest single market for goods and services by number of countries, and one of the largest by number of people given Africa’s population of 1.2 billion. The agreement aims to liberalise 90% of tariff lines within 5 years and an additional 7% of sensitive product lines within 10 years (for LDCs the timelines are 10 and 13 years respectively). In line with other modern FTAs, AfCFTA is designed to regulate additional areas with dedicated protocols on trade in services, dispute resolution, investment, competition policy, intellectual property rights (IPRs), women and youth, and digital trade. Negotiations are proceeding in two phases which are at varying degrees of implementation. During Phase I, countries discuss the trade in goods, services, dispute resolution, while during Phase II the rest of the protocols are discussed. Originally a Phase III was conceived for digital trade negotiations, but these were fast tracked by AfCFTA members and are now included in Phase II.

AfCFTA will not make previous regional agreements, such as the RECs, obsolete but rather aims to build on them to streamline the continental trade architecture and enable member countries that do not have a bilateral or multilateral agreement to trade more freely and easily with each other. The Rules of Origin (RoOs) are a case in point. Currently over six different regimes of RoOs exist on the continent, each with its own rules for how to determine the origin of goods (Table 1.1). For example, in the case of a car, the regional value added it needs to have in COMESA is at least 35-40% to qualify as coming from within the FTA and to benefit from the import duty applied, whereas within ECOWAS the rate is 30%, in SADC 45% and in Agadir 60%. In some cases, a change in tariff heading (CTH) also qualifies, whereas in others a specific process of transformation (SP), decided for that specific product, needs to have taken place. The different rules present challenges for businesses, as even if they base their production in an economy party to different agreements, the same production process might not qualify for preferential access under all of them. Moreover, as RoOs have been designed to promote trade within an FTA, they make it de facto harder to use components and inputs from countries outside the agreement, thereby providing disincentives for a truly continental trade. AfCFTA will introduce a unified regime, that will exist in parallel with those that currently exist within the different economic communities. With this, not only will it be possible to use more streamlined rules, but inputs from anywhere in Africa will be able to count towards meeting the “made in” threshold of AfCFTA.

Table 1.1. AfCFTA stands to unify rules of origin on the continent

|

|

COMESA |

EAC |

ECCAS |

ECOWAS |

SADC |

AGADIR |

CAEMC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Examples |

|||||||

|

Cotton shirts |

WO or RVC 35%-40% or CTH + ECT |

SP |

WO or RVC 40%-45% |

CTH or RVC 30% |

RVC 40% |

SP or RVP 60% |

WO or RVC 30%-40% |

|

Vaccines |

WO or RVC 35%-40% or CTH |

CTH |

WO or RVC 40%-45% |

CTH or RVC 30% |

CTH or RVC 40% or SP |

NC + ECT 20% |

WO or RVC 30%-40% |

|

Smartphone |

WO or RVC 35%-40% or CTH + RVC 35% |

CTH or RVC 30% |

WO or RVC 40%-45% |

CTH or RVC 30% |

RVC 40% |

(CTH + RVC 60%) or RVC 70% |

WO or RVC 30%-40% |

|

Cars |

WO or RVC 35%-40% or CTH + ECT |

SP |

WO or RVC 40%-45% |

CTH or RVC 30% |

SP and RVC 45% |

RVC 60% |

WO or RVC 30%-40% |

|

Selected provisions |

|||||||

|

Type of cumulation |

Diagonal |

Cross |

Diagonal |

Diagonal |

Diagonal |

Cross |

Diagonal |

|

Roll-up / absorption |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

De minimis |

No |

Yes (15%) |

No |

No |

Yes (15%) |

Yes (10%) |

No |

|

Duty drawback |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Note: At the time of writing the AfCFTA rules of origin were not finalised yet. The different levels of RVC for each line relate to the different calculation methods for value added that are included in the provisions. RVC: Regional value content. CC: change in chapter; CTH: change in tariff heading; CTSH: change in tariff subheading; SP: specific process; ECT: exception; WO: Wholly originating. HS codes used cotton shirt: 62063; smartphone: 851712: vehicle: 870323: vaccine: 300220.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on (ITC, 2022[2]), https://findrulesoforigin.org.

AfCFTA has adopted a flexible, staggered approach, allowing resolved components of the agreement to be implemented while negotiations are ongoing in unresolved areas. This approach is drawn from the TFTA which followed the same principle and is in contrast to other ‘megaregional agreements’ such as the Regional Cooperation and Economic Partnership (RCEP) in Asia, whereby negotiations need to be complete in all areas before implementing the agreement. On the one hand, this approach, combined with the impact of the COVID-19, has led to delays between AfCFTA coming into force (May 2019) and the launch of official trading (January 2021), as well as for meaningful trade to start (ongoing). This is because without solving some important outstanding issues, such as the finalisation of Rules of Origin (RoOs) and duties for remaining tariff lines, it is difficult for businesses to really trade under AfCFTA. On the other hand, this flexible approach has maintained the political momentum and the pressure to advance on all aspects of the agreement, while at the same time leaving some room for experimentation and updating. For example, the Guided Trade Initiative (GTI) is a pilot launched in October 2022 to trade under AfCFTA. The GTI involves eight countries (Cameroon, Egypt, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Rwanda, Tanzania and Tunisia) that will test how the AfCFTA operates institutionally and legally, exploring the readiness and capacity of members to trade under the new agreement. The products selected are limited and include ceramic tiles, batteries, tea, coffee, processed meat products, corn starch, sugar, pasta, glucose syrup, dried fruits, and sisal fiber. This exercise will allow feedback to be collected and will also raise awareness about AfCFTA (AU-AfCFTA, 2022[3]; Tralac, 2022[4]).

Significant progress has been made to complete negotiations, which are at different stages:

Trade in Goods: As of May 2023, about 46 members had submitted tariff offers, with 36 – including those of Egypt – considered verified and RoOs negotiated for 88.3% of agreed tariff lines (about 4 400 in total). Notable progress has also been made with regard to outstanding RoOs for automotives, textiles and apparels. For example, in automotives the AfCFTA Secretariat has proposed RoO rules that were adopted in July 2023 for selected headings. As of 12 July 2023, RoOs for 90.1% of the tariff lines for the textiles and apparel clusters had also been agreed upon.

Trade in Services: This protocol establishes principles for services liberalisation, in five priority sectors (transportation services, communications, tourism, financial, and business services). A positive list approach is taken whereby countries list sectors they commit to liberalisation under AfCFTA. Countries that hold joint membership in the WTO and the AfCFTA will need to offer market access that goes beyond what they currently offer under WTO’s General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). Commitment offers have been submitted by 48 parties, which are being verified by the AfCFTA Secretariat.

Other Phase II negotiations: The Protocols on Investment, Competition Policy, and on Intellectual Property Rights were adopted by the AU Assembly of Heads of State and Government in February 2023. These are framework agreements with outstanding matters that need to be further negotiated and resolved, including for instance issues regarding expropriations in the investment protocol. Negotiations for the rest of the Phase II protocols are advancing in parallel. On digital trade, consensus has been reached on most provisions with the exception of customs duties, cross-border data transfers, location of computing facilities, source code, and the transitional periods of aligning national laws with the Protocol. Negotiations for the Protocol on Women and Youth in Trade were concluded in June 2023 and a draft protocol has been submitted to the Committee of Senior Trade Officials.

The rate of negotiations depends not only on their complexity and sensitivity, but also on the body of existing regulatory efforts. Two of the guiding principles that underpin the AfCFTA are the preservation of the aquis3 and the best practices of RECs, and so Protocols are likely to build upon what has been done in existing regional agreements on the continent. For example, WAEMU, COMESA, EAC, ECOWAS and CEMAC have regional competition regimes in place that inform protocol negotiations. However, this also means negotiations must address harmonisation of the different existing frameworks, too. Frameworks can also be particularly fragmented. For example, the regional regulatory regime for IPRs is composed of the Organisation Africaine de la Propriété Intellectuelle (OAPI) and the African Regional Intellectual Property Organization (ARIPO). However, several large African economies, such as Nigeria, South Africa, Egypt and Morocco, are not members of either OAPI or ARIPO which complicates the AfCFTA negotiations over IPRs (Tralac, 2022[5]). In other cases, such as digital trade negotiations, need to begin from scratch as no existing frameworks within Africa exist.

A number of tools have also been devised with the aim of disseminating information to relevant stakeholders and raising awareness. These include the AfCFTA e-Tariff Book, which makes tariff concession schedules and rules of origin accessible and searchable on line and the African Trade Observatory (ATO) led by the African Union, which was developed by the International Trade Centre (ITC) and funded by the European Union (EU). ATO is a dashboard that provides real-time information on detailed trade and market data as well as information on RoOs, customs procedures, market information and due diligence. Another example is the Online Non-Tariff Trade Barriers (NTBs) notification mechanism, where traders can file complaints on trade obstacles, open to all businesses, even informal ones. Finally, the AfCFTA hub, which aims at creating a trusted business directory of businesses trading in Africa by issuing a unique, continentally recognised AfCFTA number for SMEs, sole proprietors, traders and community-based organisations, is yet another example. Several of these tools are still in their pilot phase, in anticipation of the start of meaningful trade.

An articulated governance structure has been set up to ensure the agreement continues to serve the strategic objectives of the continent, while it has the autonomy and capacity to implement and monitor the agreement. The Assembly of the African Union, which is made up of AU government heads, is responsible for the strategic orientation of the agreement. The Council of Ministers, comprised of Ministers of Trade from AfCFTA members and distinct from the AU’s Ministers of Trade Committee, has oversight over the execution and administration of the agreement. The Committee of Senior Trade Officials has responsibility for the implementation of Council of Ministers decisions. The AfCFTA Secretariat is designed to co-ordinate and support the implementation of AfCFTA. The AfCFTA Secretariat has an independent legal personality – and is functionally autonomous within the AU system – although funding for it comes from the AU budget and its roles and responsibilities are determined by the Council of Ministers. AfCFTA also provides for the establishment of a dispute settlement system. Finally, AfCFTA puts in place a number of technical committees including the Committee on Trade in Goods and the Committee on Trade in Services. The creation of a Secretariat within AfCFTA is in line with some other megaregional agreements, although not all of them have this function. RCEP which entered into force in 2022 also provides for a secretariat. However, this has not yet been formally established, while CPTPP is managed through a rotation system. Although it is too early to make an assessment, the Secretariat could enable AfCFTA to more easily update over time and to monitor and promote its use.

References

[6] Afreximbank (2020), African Trade Report 2020: Informal Cross-Border Trade in Africa in the Context of the AfCFTA, Afreximbank, Cairo, https://media.afreximbank.com/afrexim/African-Trade-Report-2020.pdf.

[3] AU-AfCFTA (2022), The AfCFTA Guided Trade Initiative, https://au-afcfta.org/2022/09/the-afcfta-guided-trade-initiative/.

[7] Erasmus, G. (2021), AfCFTA Parallelism and the Acquis, https://www.tralac.org/blog/article/15085-afcfta-parallelism-and-the-acquis.html.

[2] ITC (2022), Rules of Origin Facilitator, https://findrulesoforigin.org/.

[5] Tralac (2022), “AfCFTA Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)”, Tralac, Western Cape, South Africa, https://www.tralac.org/publications/article/13784-afcfta-questions-and-answers.html.

[4] Tralac (2022), “The AfCFTA Secretariat’s Guided Trade Initiative has been launched: How will it work and where does trade under AfCFTA rules now stand?”, Tralac, https://www.tralac.org/documents/events/tralac/4625-tralac-special-trade-brief-afcfta-guided-trade-initiative-october-2022/file.html.

[1] UNCTAD (2023), Unctadstat (database), https://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/.

Notes

← 1. They comprise: the Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD), the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), the East African Community (EAC), the Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS), the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the Southern African Development Community (SADC), and the Arab Maghreb Union (UMA).

← 2. Actual intra-African trade could be higher if informal cross-border trade is considered, which is prevalent in some regions (Afreximbank, 2020[6]).

← 3. Roughly meaning common rules, although the term is not defined in the text (Erasmus, 2021[7]).