AfCFTA could open new opportunities for African businesses through a united market, and harmonised rules that go beyond trade in goods. This chapter looks into the potential of AfCFTA to boost Africa’s role in emerging industries, with a focus on renewable energies, pharmaceuticals, cultural and creative industries, and logistics.

Production Transformation Policy Review of Egypt

3. AfCFTA could be a game changer for emerging industries

Abstract

Introduction

AfCFTA holds the potential to open new opportunities for African businesses through a united market, and harmonised rules that go beyond trade in goods.

This chapter examines the potential of AfCFTA to boost Africa’s role in emerging industries, with a focus on renewable energies, pharmaceuticals, cultural and creative industries, and logistics. While Africa still plays a small role in these industries, they are among continental priorities for the future, building on existing natural assets, pockets of innovation and industrial capabilities, cultural heritage and rapidly advancing digitalisation.

Renewable energies

Energy is key for industrialisation. The continent lacks affordable, stable and secure energy to match its industrial ambition. The global call for shifting towards greener production and consumption could enable Africa to tap into renewable energies and their industrialisation potential, while exploiting and using all forms of available energy sources in the meantime.

Renewable energies can offer a wealth of opportunities for Africa and countries all across the continent are eager to take advantage of this potential. In Egypt, the Integration Sustainable Energy Strategy 2035 launched in 2015, aims to increase renewable electricity to 42% of total by 2035 (in 2019 the share stood at 9.4%), while the National Climate Change Strategy (NCCS) 2050 launched in 2022, with the aim of integrating efforts to tackle climate change. The country hosted COP27 in November 2022 and launched the Loss and Damage Fund, which aims to provide financial assistance to those nations most vulnerable to climate change. Egypt has also been trying to increase linkages between digitalisation and the sustainability agenda with targeted investments and initiatives, such as the Applied Innovation Centre under MCIT. The fund fosters innovations for smart agriculture and organises competitions for start-ups and innovators in a range of sustainability domains, including energy. Examples include ClimaTech, which was created in co-operation with the Ministry of International Development, and Climathon, which is a joint effort with the Egypt University of Informatics. Both got off the ground in the run-up to COP27.

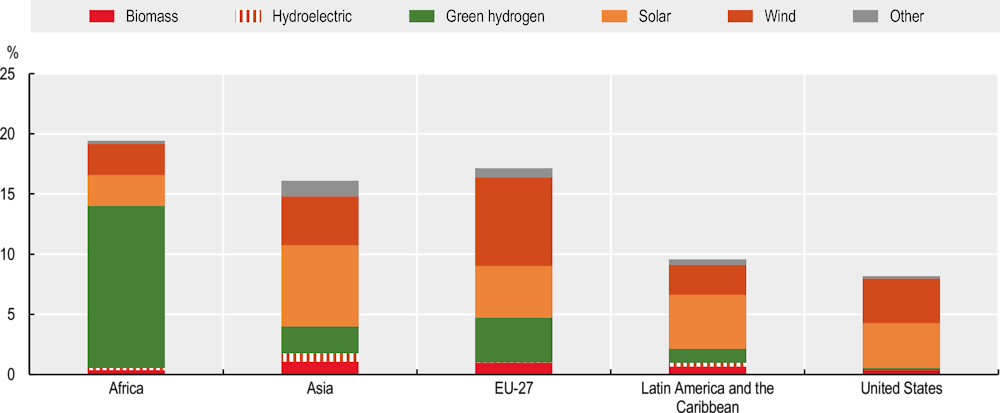

Africa has untapped natural potential in renewables. Africa has some of the highest solar irradiation in the world with IEA estimating that it holds 60% of the world’s best solar resources, but only 1% of installed photovoltaic (PV) capacity. Egypt, for example, gets over 3 000 hours of sunshine per year compared to 1 700 on average in Germany while the latter has almost 35 times the installed solar PV capacity (IEA, 2022[1]; IRENA, 2022[2]). Other resources on the continent include: abundant hydropower resources, with some industry estimates suggesting that the continent is only using 11% of its available resources, the lowest utilisation share of all world regions (IHA, 2022[3]); geothermal energy, with Kenya, for example, being the world’s 7th largest producer of geothermal energy by installed capacity, surpassing Iceland (IRENA, 2022[2]); and wind, with only about 0.01% of potential utilised (Van den Berg, 2022[4]). Egypt for example has high wind speeds in the Red Sea, Mediterranean, and inland areas (WMO, 2022[5]; OECD, 2021[6]). These renewable resources also point to the continent’s potential for green hydrogen, an area that is already attracting investor interest. Overall, investments in renewables have surpassed those of fossil fuels in the continent (AUC/OECD, 2023[7]). During 2018-22, Africa was the destination for about 9% of FDI projects in renewables, but 19% of the capital invested, higher than the share of EU-27 and Asia (Figure 3.1). The continent’s FDI performance has been driven mostly by green hydrogen projects that attracted large-scale investments in 2022. In fact, the need to secure energy supplies made that year a record one for renewables globally, with total investments about three times as high as the previous year.

Figure 3.1. Africa absorbed 19% of FDI in renewables during 2018-22

Note: Marine and geothermal have been placed under “Other”. Hydrogen has been identified using the tag “hydrogen” in the database.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on (Financial Times, 2023[8]), fdimarkets, https://app.fdimarkets.com/.

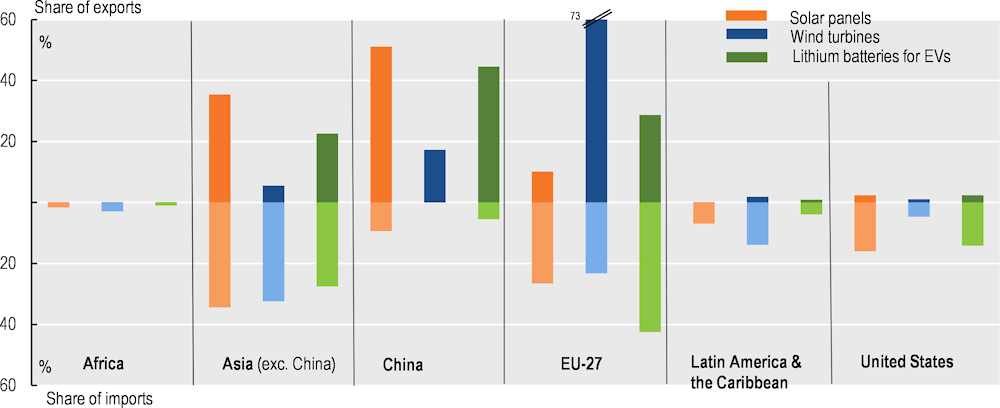

Africa is also home to natural resources that are key for renewable energy value chains. Africa is a marginal player in the development and trade of renewable energy products. For instance, Africa accounts for less than 1% of exports in solar panels, lithium batteries or wind turbines (Figure 3.2). Lithium batteries are produced overwhelmingly in China (79%), followed by the United States (6%), Hungary (4%), Korea (3%) and Hungary (3%) (Figure 3.3). This pattern is confirmed in other technologies, such as wind turbines (58% produced in China, followed by the EU with 19%) and photovoltaic solutions (China produces 75% of solar PV modules) (IEA PVPS, 2022[9]; GEWC, 2022[10]). However, the continent is home to important commodities and minerals that are key for renewables. For example, African countries account for 69% of the world’s cobalt production, 50% of the world’s manganese production and 14% of the world’s copper production, raw materials which collectively account for about one-fifth of the weight of an electric vehicle battery (Mathieu and Mattea, 2021[11]). The continent is also home to about 77% of platinum production, which is a key fuel cell catalyst for the production of hydrogen. These could be used as springboards for entering value chains and gradually expanding manufacturing capabilities that centre on their sustainable extraction, processing and use – provided conducive strategies and partnerships are set up.

Africa has the ambition to scale up industrialisation efforts and has existing industrial hubs that could offer downstream usage opportunities for renewable energies, as well as industrial capacities to generate renewable energies. Egyptian float glass companies, for example, have the facilities and technical expertise to produce high-purity silica sand which is a critical input in the production of photovoltaics while some firms are already engaged in wind turbine and tower production through joint ventures. In concentrated solar power the local manufacturing share was estimated at 55% and in wind farms the share ranges from 20% to 30% (IRENA and EIB, 2015[12]).

Figure 3.2. Trade by region in key renewable technologies, share of global total, 2020-22

Note: HS codes used: Lithium battery: 850760; wind turbine: 850231; solar panel: 854140 for 2020-21, 854143 and 854142 for 2022.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on (UN Comtrade, 2023[13]), Database, https://comtrade.un.org/.

Figure 3.3. Lithium batteries and key minerals and commodities needed for their production, top 5 supply hubs, 2021

Source: (USGS, 2022[14]), https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/copper-statistics-and-information and (Yu and Sumangil, 2021[15]), Top electric vehicle markets dominate lithium-ion battery capacity growth, https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/blog/top-electric-vehicle-markets-dominate-lithium-ion-battery-capacity-growth

AfCFTA increases the market for energy. So far, countries in Africa have been mostly trading electricity bilaterally, as the five African Power Pools1 that have been created have varying levels of integration and have been hampered by a lack of infrastructure and regulatory mismatches and gaps (Odetayo and Walsh, 2021[16]). Other regional initiatives, such as the launch of the African Single Electricity Market in 2021, whose full operation is anticipated by 2040 (IRENA, 2022[17]), are also expecting to build on the momentum of the AfCFTA to create an operational continental electricity market.

To take advantage of the opportunities of the AfCFTA, African countries will need to mobilise investments and link industrial strategies to the green transition. Though there are currently no special provisions in AfCFTA for green goods (Van der Ven and Signé, 2021[18]), the agreement’s Investment Protocol makes specific reference to fostering investment aligned with sustainable development, including mitigating and adapting to climate change, and safeguards the right of members to regulate in accordance. Such provisions, in addition to the contribution of the agreement to improved trade and investment climate in the continent, could prove a lever for renewables by providing an opportunity to link industrialisation and the greening of the energy matrix. To do this, it will be necessary to bolster the scale of investments. Large projects are needed that go beyond pilot and microgrid projects to stimulate demand and generate, in turn, the energy needed for green industrialisation on the continent. The IEA (2022[19]) estimates that annual energy investments in Africa will need to double from their current level to nearly USD 192 billion annually to meet the continent’s energy goals. For example, South Africa’s Industrial Policy Action Plans have been using, since 2010, public procurement for renewables for the promotion of local capabilities and have been encouraging the use of more sustainable technologies in industry. Advancing on quality systems and certification for renewables will also be important. For example, currently certification for green hydrogen is at an early stage and mostly led by large consumer markets. Ensuring that African countries have a voice in the definition of such standards, and that they update their metrology and conformity assessment infrastructures to meet these standards, is also critical. Finally, protocols that are still being negotiated could include green industrialisation considerations. This is the case for protocols related to services such as transport (Asafu-Adjaye et al., 2021[20]).

Pharmaceuticals

The continent imports 94% of its pharmaceuticals and 96% of its vaccines, according to estimates by ECA, making the continent vulnerable to supply chain disruptions, as revealed during the COVID-19 pandemic (OECD/UN ECA, 2020[21]). In fact, the experience of countries during the pandemic showed the various ways in which dense and effective healthcare industrial ecosystems, through mobilising manufacturing capacities, facilitating trade and investing in innovation, are essential for responding to emergencies (Box 3.1). Investments in healthcare industrial ecosystems are also necessary to address Africa’s long-term healthcare challenges, going beyond the ongoing pandemic, and even to unlock opportunities for economic transformation by encouraging local manufacturing and innovation.

Box 3.1. A taxonomy of technological and industrial solutions to face the pandemic

Countries fought the COVID-19 pandemic in different ways. An effective strategy requires adequate, accessible, affordable, safe and timely supply of medical devices, drugs and skilled personnel across four areas: testing, protecting, treating and curing (TPTC) (Table 3.1). These areas differ according to scientific content, research and development (R&D) intensity and manufacturing complexity. They also share a common critical requirement: the solutions need to be timely, affordable, safe and comply with approved standards. In the case of COVID-19, the required effort in R&D and the reliance on scientific research have been higher for the solutions linked to testing and curing. Manufacturing involves relatively simpler processes for personal protective equipment (PPE) than for ventilators, making industrial reconversions a relatively simpler option to secure local access for PPE, even though the management of the specific supply chains is highly complex in all areas. Standards, trade facilitation and tailored intellectual property (IP) management are important in facilitating access to drugs and vaccines.

Table 3.1. The testing, protecting, treating and curing (TPTC) framework

|

TESTING |

PROTECTING |

TREATING |

CURING |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

OBJECTIVE |

Enabling massive screening ASAP |

Minimising contagion through protective devices [for medical and sanitary personnel, patients and common citizens] |

Providing assisted breathing and drugs to critical patients |

Healing infected patients |

|

CHALLENGES |

Inadequate diagnostic equipment (too slow, too - capability-intensive, too expensive and require laboratory testing) Lack of universally validated protocol |

Global supply shortages |

Global supply shortages and few global players capable of producing them Availability of replaceable components [e.g. valves] Required know-how for using sophisticated/new devices High unit cost |

Uncertainty of research outcomes Timing for clinical trials & Approbations Affordability |

|

TECHNOLOGICAL AND INDUSTRIAL SOLUTIONS |

Partnerships for research and technology transfer Fast tracking testing and clinical trials Enabling global approval based on first national approval Fostering technology transfer and enable local manufacturing |

Enabling local manufacturing by: 1) scaling up local production; 2) reconverting industrial plants [e.g. textiles, printing, beverages and cosmetics] Facilitating imports and exports Co-ordinating donations to target the most vulnerable |

Scaling up production of current producers Enabling industrial reconversions [e.g. automakers] Fast taking imports & exports Bridging capital, competences and technologies to foster innovation |

Testing for second-use of existing drug treatments Vaccine research & development Drug & vaccine manufacturing |

|

CRITICAL REQUIREMENTS |

MEDICAL SUPPLY NEEDS TO BE: Adequate Accessible Affordable Safe Timely SCALING UP QUICKLY HOSPITAL CAPACITIES OVERCOMING THE SHORTAGES IN MEDICAL PERSONNELL |

|||

Source: (OECD/UN ECA, 2020[21]), "Africa’s Response to COVID-19: What roles for trade, manufacturing and intellectual property?", OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/73d0dfaf-en.

African governments have long committed to increasing local capacities in manufacturing of pharmaceuticals. At the continent level, the Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Plan for Africa (PMPA) was adopted in 2007 and the African Vaccine Manufacturing (PAVM) for example, launched in 2021, outlined priority actions for enabling the continent to produce 60% of the vaccines it needs locally by 2040. Several governments also have plans to increase their capacities. For example, Ghana, following the PMPA introduced a Ghana Pharmaceutical Sector Development Strategy that included tax and other incentives, such as preferential procurement, to enable Ghana to become a manufacturing hub (Peprah Boaitey and Tuck, 2020[22]). Ethiopia also developed a National Strategy and Plan of Action for Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Development following the PMPA.

Currently, while some capacity in pharmaceuticals exists on the continent, it suffers from small scale and low quality. Data on production is sparse, nevertheless statistics from UNIDO (data for 11 countries) suggest that in aggregate Africa accounts for about 1.6% of world manufacturing value added in the sector, compared to China and India (25% and 17% respectively), and the EU where several large multinationals are headquartered for 64% (data for 2018 or latest year). Egypt (Box 3.2), Algeria, South Africa and Ghana are Africa’s top producers, with production largely absorbed by local markets (Conway et al., 2019[23]). Quality across the continent could be higher. For example, 37 companies from Egypt, Morocco, South Africa and Tunisia have a Good Manufacturing Practice certificate that is valid for the European market and specifies strict quality guidelines, compared to 21 in Brazil only and 253 in China (authors’ calculations based on EudraGMDP database (2022[24])). Counterfeit and sub-standard medicines are also big challenges for the continent (WHO, 2017[25]).

Box 3.2. Spotlight on Egypt’s pharmaceutical sector

Egypt is one of the continent’s largest producers and exporters of medicines. For example, during 2019‑21 it generated 24% of African pharmaceutical exports, the top second after South Africa (32%) (authors’ elaboration on (UNCTAD, 2023[26])). The largest market for Egyptian pharmaceutical exports was the Middle East which accounted for 63% of exports, followed by Europe (18%). Sub-Saharan destinations accounted for approximately 10% of the total.

According to the Ministry of Health, local production met 93% of the country’s drugs needs in 2018/19 up from 83% in 2009/10, with 97% of production being generics. The country’s establishment census in 2017 noted that 10 out of 206 active establishments in the industry, were public and the rest private businesses. In addition to local players, some multinationals have also established operations in Egypt. The country’s large market and growing spending power and its location close to markets in Africa, Europe, and Asia, have made Egypt an attractive location for producers.

Developing the pharmaceuticals sector is a priority in Egypt to achieve better health outcomes and promote structural transformation. The Egyptian government has in place targeted policies and incentives to foster production and exports for the pharmaceuticals sector, including:

Fostering partnerships. In 2018 Egypt adopted a package of incentives under the slogan “100 million healthy lives” with the aim of providing comprehensive healthcare for all its citizens. Under this programme, the Initiative to Eliminate Hepatitis C and Non-Communicable Diseases, managed to successfully reduce the prevalence of Hepatitis C virus in the country. This was achieved through screening, the negotiation of lower prices with global producers, but also by modernising the partnership between government and the private sector to achieve low-cost production of generic treatments in Egypt. In addition, the country fosters regular dialogue between producers and government, as for instance through the periodic Industry Forum between the Egyptian Drug Authority (EDA) and pharmaceutical companies. Strategic projects have also been encouraged, such as Gypto pharma’s “medicines city” which aims to set up large-scale and advanced facilities for production and exports and boost partnerships between the public and private sectors.

Encouraging investments and technology development. Pharmaceutical industries qualify for incentives under Egypt’s Investment Law No. 72/2017. The country has also been pursuing joint ventures that can improve its production capabilities, particularly in more sophisticated segments. For instance, an MoU was signed in 2021 between Egypt's state-owned Holding Company for Pharmaceuticals, the Pharmaceutical Egyptian Association (PEA) and India-based Syschem to produce Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) in the country. Some imported ingredients for pharmaceuticals have also been exempted from VAT.

Promoting exports. The Egyptian Drug Authority has introduced a temporary registration system for medicines that are exported only to reduce the regulatory burden required for exports. This measure has encouraged export operations. For example, the Export Council of Medical Industries (ECMI) established in 2018 the EGYCOPP company with the aim of acting as a manufacturing-for-export launchpad. It also spearheaded contract manufacturing in partnership with local and foreign players. The government also fosters exports by engaging in market intelligence activities and encouraging promotional missions to key destinations, including in Africa. The EDA also pursues mutual recognition agreements, complemented by regional and continental initiatives for regulatory harmonisation. For instance, the Arab-Africa Trade Bridges Program, a multi-donor and multi-country initiative, is also undertaking a Harmonization of Pharmaceuticals Initiative, in partnership with ARSO. Finally, an export subsidy has been launched by EDA.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on information provided by the Ministry of Health.

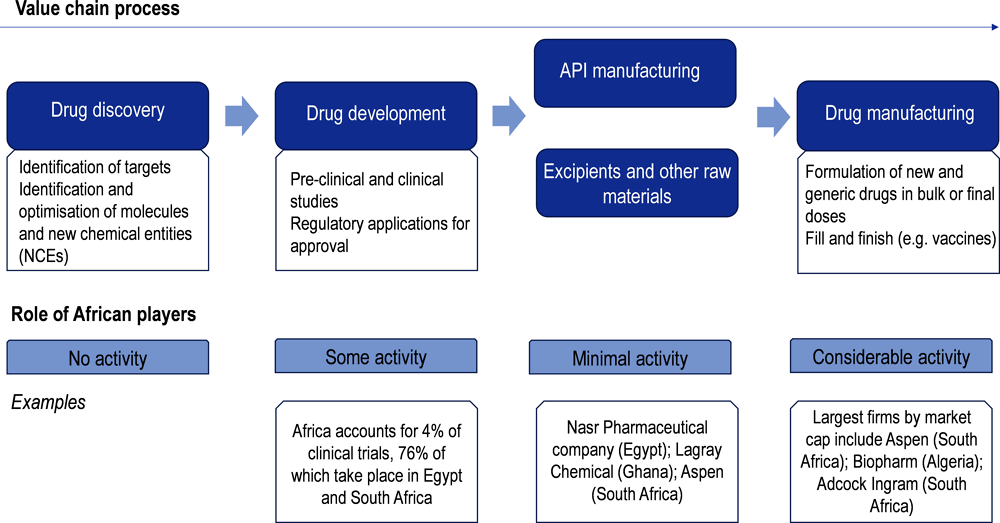

Pharmaceutical production in Africa is largely concentrated in downstream activities (Figure 3.4). African firms generally do not engage in new drug research, which highlights the R&D deficit across the continent. There is also minimal activity in the production of active pharmaceutical ingredient manufacturing (API), which are the substances that are responsible for the main effect of a drug. Production of APIs at a global level are concentrated in East and Southeast Asia, which accounts for 61% of the total, followed by Western Europe and North America, with the three regions accounting for 93% of the total (EFCG, 2014[27]). By contrast, most pharmaceutical activity takes place at the final manufacturing stage, often with imported APIs, excipients, and other raw materials. The vaccine industry is a case in point. There are a handful of African vaccine makers in Northern Africa (Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia) as well as Ethiopia, Nigeria, Senegal and South Africa (Figure 3.5). They are made up of a diverse group of firms. Some were created with public sector initiatives aiming to creating local capabilities, such as Vacsera in Egypt and Biovac in South Africa. Others are start-ups relying on biotechnology innovations, such as South Africa-based African Biologics. Going into the pandemic only four companies in Africa were involved in substance manufacturing for vaccines and three companies conducted R&D. The majority of players in Africa were instead mostly involved in fill and finish activities that are relatively simpler. However, activities were overall small in scale. For example, Biovac has a capacity of about 20-30 million doses annually, according to press reports, compared to 1.5 billion prior to the pandemic for the Serum Institute of India.

Figure 3.4. Pharmaceutical value chain in Africa

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on (Narsai, 2021[28]), “Strengthening Africa’s value chains”, Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance, T-Talk on 3 November 2021 in the framework of the PTPR of Egypt: Spotlight on the AfCFTA and Industrialisation; (Lartey et al., 2018[29]), Pharmaceutical Sector Development in Africa: Progress to Date; (US National Library of Medicine, 2023[30]), Clinical trials database, https://clinicaltrials.gov/.

Figure 3.5. African vaccine makers and their functions, 2022

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on (DCVMN, 2021[31]), Vaccine manufacturing in Africa, DCVMN briefing document, https://www.dcvmn.org/Webinar-briefing-to-DCVMN-members-on-What-will-it-take-to-manufacturer-vaccines and (UNICEF, 2022[32]), COVID‑19 dashboard and press reports, https://www.unicef.org/supply/covid-19-market-dashboard.

AfCFTA could open up new opportunities for pharmaceuticals, particularly by advancing regulatory harmonisation. The agreement helps solidify a market that is large and expanding – by 2030 the African healthcare market is projected to be worth USD 259 billion, second only to that of the US (UNECA, 2019[33]). Pilots are already underway on how AfCFTA could help firms take advantage of such opportunities. The AfCFTA – Anchored Pharmaceutical Initiative was launched in 2019 in collaboration with AUC, AUDA-NEPAD, IGAD, WHO, UNAIDS and other relevant UN agencies to demonstrate implementation in the health sector. The pilot is in Seychelles, Madagascar, Comoros, Mauritius, Djibouti, Eritrea, Rwanda, Sudan, Kenya and Ethiopia and aims at improving access to maternal, neonatal and child health essential medicines through three pillars, namely, pooled procurement of pharmaceuticals, local production, and harmonisation of regulatory and quality standards frameworks. The Centralised Pooled Procurement Mechanism was launched in 2021. Moreover, AfCFTA is set to ease some restrictions on the movement of people across borders, in relation to investment and services, which could help talent move more easily and encourage scientific co-operation. Free movement of people is one of the goals of the Agenda 2063, and it has been made more concrete in a protocol on the Free Movement of Persons signed in 2018, but implementation has been lagging, with only four countries (Niger, Mali, Rwanda and São Tomé and Príncipe) having ratified the protocol as of 2021 (ECDPM, 2021[34]).

To capitalise on AfCFTA, countries will need to advance in tandem on the implementation of continental initiatives and take action to strengthen their capabilities in innovation and manufacturing, particularly in knowledge-intensive activities. Boosting investment in R&D, for instance, which historically has been low in Africa, is essential. On average African R&D stands at 0.33% of GDP, a rate which is less than one‑eighth the OECD average (2.75%) [authors’ elaboration on (UNESCO, 2023[35]; OECD, 2023[36])]. Nevertheless, a handful of countries have been increasing their innovation efforts, which could support the sophistication and expansion of pharmaceutical industries. Egypt for example is investing 0.96% of its GDP in R&D, the top in Africa, followed by Rwanda (0.76%) and Tunisia (0.75%). Governments will also need to invest in making regulatory frameworks conducive and accompanied by a dense, low-cost and accessible ecosystem of quality and conformity assessment services. A study conducted by the ITC (2022[37]) noted that one of the biggest obstacles for pharmaceutical firms in Africa – more so than in other sectors – were uncertainties regarding environmental and waste disposal regulatory frameworks and facilities. In addition, strengthening linkages between government, industry and academia is needed to increase the flow of talent and enable research to become more solution-oriented and with higher impact. The COVID-19 pandemic showed how a united Africa can build on its assets to mobilise and expand healthcare industrial capacities, especially if international partnerships can be mobilised, providing a springboard for sustained economic transformation (Box 3.3).

Box 3.3. Africa’s Response to COVID-19: What roles for trade, manufacturing and intellectual property?

The COVID-19 health emergency revealed that shared commitment and collaborative actions are crucial to mobilise financing, facilitating access to knowledge and technology, investing in research and development and in securing free and fast trade and logistics. Shared actions between national governments, the private sector and international partners and a renewed form of global solidarity are needed to enable Africa, and the world, to overcome this health emergency. If strategically managed, this response could set the continent on a renewed, job-rich and sustainable development pattern. It could do so by enabling industrialisation and home-grown innovation leveraging the immense unexploited opportunities of continental integration enabled by AfCFTA.

Five priority areas for action stand out for governments and businesses in Africa, and for the international community from a trade, industrial and intellectual property policy perspective

1. Fast-tracking imports, exports and movement of skilled personnel within Africa and globally

Ensuring free and fast cross-border movement of critical health and technical experts.

Facilitating imports and exports

Co-ordinating at the continent level, leveraging Regional Economic Communities

2. Scaling up continental manufacturing capacities

Enabling local manufacturing

Supporting effective industrial reconversions

3. Managing supply chains effectively

Implementing a co-ordinated continental approach, leveraging the Africa Union Commission AFTCOR

Mobilising existing capabilities to fast track and secure logistics

Using digital services and technology based companies

4. Fast tracking affordable access to technology, knowledge, drugs and vaccines

Facilitating technical knowledge sharing through digital technologies among doctors, health professionals and businesses to access knowledge and speed up the learning process.

Achieving a global deal to make intellectual property work to ensure fast and affordable access to drugs, medical equipment and COVID-19 related technologies

Fast tracking testing and clinical trials

Tracking and banning counterfeit drugs and medical equipment

Sustaining research and development in Africa

5. Urgently bridging the short- and long-term financing gaps

Fast-tracking financing for companies involved in providing COVID-19 related solutions

Strengthening national development banks’ capacities to channel financing to companies involved in COVID-19 related solutions

Mobilising international and regional development finance to cushion the impact of COVID-19

Channelling donations to the most vulnerable and those in need.

Source: (OECD/UN ECA, 2020[21]), "Africa’s Response to COVID-19: What roles for trade, manufacturing and intellectual property?", OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/73d0dfaf-en.

Cultural and creative industries (CCIs)

Africa’s cultural heritage is rich and diverse, with a vast array of African cultural and creative cultural products and services sold around the world. For example, the film sector currently generates a value added of USD 5 billion (about 0.3% of Africa’s GDP) (Afreximbank, 2022[38]). The most prominent example is the Nigerian film industry, Nollywood, recognised as the world’s second largest film producer. In 2021, Nollywood is estimated to have employed close to 300 000 persons, most of them youth. Africa’s fashion industry is also growing rapidly with world famous woven textiles in Nigeria, Ghana, Uganda, Kenya, South Africa and Tanzania. Other examples abound. Egypt, for example, is a key producer of CCIs in Africa, with a history in textiles and film, and several assets to exploit, such as iconic cultural heritage locations, world-class museums, a strong tradition as the filmmaking centre of the Arabic speaking world, and a rich artistic and handicraft industry (UNCTAD, 2018[39]; EY, 2015[40]). Africa’s CCIs are set to grow further as digital services allow African creators to reach continental and global audiences while increasing rates of smartphone and tablet ownership fuel demand for digital content. Digital technology has become a vital tool for enhancing the production and sharing of CCIs. For example, revenue from digital music streaming is anticipated to reach USD 500 million by 2025 – a five-fold increase from 2017 (World Bank, 2022[41]).

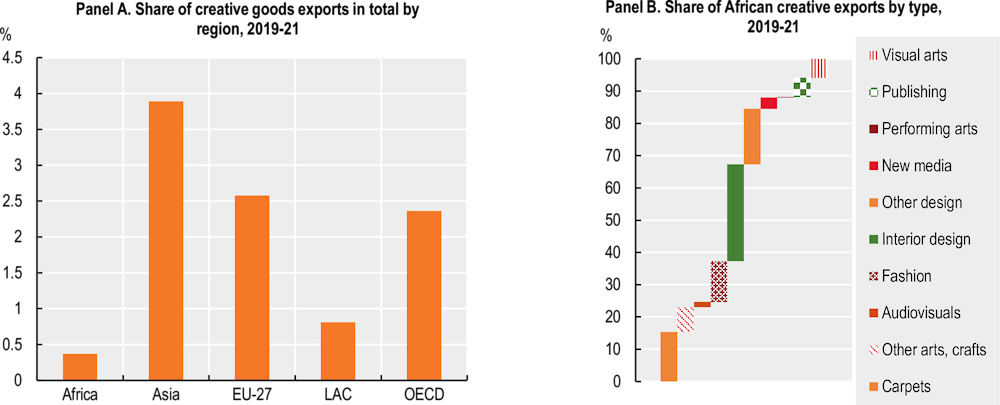

Despite the continent’s vast creative resources, CCIs are an emerging export sector for Africa. In terms of goods, creative exports accounted for less than 1% of continental exports to the world, compared to nearly 4% in Asia and 3% in the EU-27 in 2019-21 (Figure 3.6). Most African creative goods exports concentrate in interior design goods (30%), carpets (15%) and fashion items (12%), with Egypt and Tunisia the top two exporters accounting for 19% of the total, followed by Kenya, Mauritius and Tanzania. In terms of services, experimental data from UNCTAD, shows that similarly creative services amounted to only 2% of total trade in services for the continent, compared to 20% for Europe and 15% for Asia, with software accounting for the bulk of creative services (36%), followed by advertising (26%). However, greater integration could further boost CCI potential in Africa. The share of intra-African exports of creative goods was 25% during 2019-21, greater than the share of total intra-Africa exports overall at 15% during the same period.

Figure 3.6. Cultural goods exports have room to grow in Africa

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on (UNCTAD, 2023[26]), Unctadstat, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/.

The AfCFTA offers significant potential to further transform and commercialise Africa’s creative industries. More specifically (Afreximbank, 2022[38]):

In Phase I negotiations, in addition to liberalising tariff barriers, member states have agreed on five priority services for the first round of AfCFTA services negotiations: business services, communication services, financial services, tourism and travel, and transport. Although currently CCIs are not included in the priority list (after all they cut across different services) the services discussed are all critical elements to enable the growth of dynamic and efficient creative industries.

The investment protocol provides common rules for state parties to introduce harmonised incentives for attracting investments to accelerate creative development.

The AfCFTA Protocol on digital trade will provide a continental framework to integrate and expand the e-commerce space, enhance access to digital technologies, and develop regulations relating to piracy and consumer protection, all of which are of critical importance to the development of competitive creative industries in the digital age.

The AfCFTA Protocol on intellectual property rights provides a harmonised and coherent framework for the protection, administration and enforcement of IPRs on the continent. This will reduce costs associated with dealing with multiple jurisdictions and contribute to a stronger and more enforceable legal protection of rights. More broadly, the AfCFTA negotiations on intellectual property rights offer an opportunity for African countries to develop a common position on protecting and enforcing these rights to support the growth and development of Africa’s CCIs and reduce cultural exploitation. The AfCFTA also offers a framework for supporting official co-productions across national borders.

To fully make use of the AfCFTA to boost CCIs in Africa, countries, among other things, will also need to advance on:

Updating national policy frameworks in line with the changes in CCIs in Africa and globally. Some countries in Africa are already taking steps to promote CCIs by offering financial support and other assistance, such as networking. For example, South Africa introduced in 2011 the Mzansi Golden Economy Strategic Plan in Department of Sport, Arts and Culture (DSAC), which supports large-scale projects related to the arts, culture, and heritage sectors. Cabo Verde through the Fonds Autonome d’Appui à la Culture (Autonomous Fund to support Culture) promotes the cultural sector by creating clusters and launching three intertwined networks to disseminate output in the form of crafts, arts and museums. Such support will need to be scaled up and modernised, particularly in response to the digital trends that are currently reshaping the industry. New continental initiatives are complementing such efforts, such as the Creative Africa Nexus (CANEX) programme by Afreximbank (Box 3.4).

Fast-tracking the implementation of the African Union Plan of Action on Cultural and Creative Industries. The Plan was adopted in 2008 and updated in 2021 to reflect a new landscape for CCIs on the continent. It outlines priorities for development and strategic co-ordination.

Increasing the availability and quality of data on CCIs. Currently there exists no comparative global database on the production of CCIs, which hampers evidence-based policy making and monitoring.

Strengthening standards and regulatory compliance to overcome challenges in image and reputation, and piracy that threatens revenue streams.

Box 3.4. Unleashing creative industries in Africa through continental initiatives: The CANEX programme

Afreximbank established the Creative Africa Nexus (CANEX) programme, in January 2020. Through CANEX, the Bank is investing USD 500 million to support the sector. This facility aims to monetise the commercial value of CCIs. The programme aims to support creative talent across Africa and the Diaspora especially in fashion, film, music, sports, visual arts, and crafts. It is envisaged as a one-stop-shop for governments, creative companies, and individuals to find and access technical support, finance, investment, and market opportunities. Key instruments of intervention under the CANEX programme include i) financing (debt, equity, advisory), ii) capacity building (masterclasses, accelerator/incubator program), iii) digital solutions, iv) linkages and partnerships, v) investment and export promotion (market access and twinning services), and vi) policy advocacy.

The Bank also created the Creative Africa Nexus show. As Africa’s first continental platform, it brings together the continent’s creative talents drawn from the music, arts, design, fashion, literature, publishing, film, and television sectors. Dedicated to promoting and exhibiting products within the cultural and creative industry, the programme holds the CANEX Weekend (CANEX WKND) and CANEX at Intra-African Trade Fair (IATF) events to convene leaders from culture and creative industries from Africa and the diaspora to explore cultural and creative market opportunities.

Source: Afreximbank (2022[38]), African Trade Report 2022: Leveraging the Power of Culture and Creative Industries for Accelerated Structural Transformation in the AfCFTA Era, https://media.afreximbank.com/afrexim/AFRICA-TRADE-REPORT-2022.pdf.

Logistics

AfCFTA is giving renewed impetus to logistics, with the opening of new routes to trade, whether inland, sea-bound or airborne. ECA, for example, estimates that demand for intra-African freight might increase by around 28% and that intra-Africa trade in transport services has the potential to increase by 50% (UN ECA, 2022[42]). Moreover, population growth, urbanisation and the rise of e-commerce are also adding pressure on Africa’s logistics chains to expand, modernise and reach previously underserved communities.

To enable logistics to flourish and support increasing trade, countries will need to work together to solve long-standing challenges that go beyond tariff barriers. Africa already has some important logistics hubs, such as large ports – Tanger Med in Morocco, Port Said in Egypt, Lome in Togo, Tema in Ghana and Abidjan in Côte d'Ivoire are among the top 100 most connected ports in the world, according to data by UNCTAD – and a growing network of inland facilities. Countries are also prioritising logistics development in their national development plans, including in Egypt. However, advancing further in updating multimodal infrastructure is critical. The infrastructure gap in Africa is estimated at about USD 53-93 billion per year for the continent (ICA, 2021[43]). In addition, countries will need to address issues that are increasing the time and cost it takes to send goods through the continent. Estimates by Armstrong and Associates, a private consultancy, indicated, for example, that logistics costs as a share of GDP was 14.3% in Africa in 2020 (Armstrong and Associates, 2022[44]), compared to 12.9% in Asia Pacific and 8.6% in Europe, indicating higher costs of services. High red tape, lack of standardisation of freight and challenges related to maintaining security and health, are among the most important issues facing logistics providers. It will be important to continue to address non-tariff trade barriers (NTBs) by for example working with other countries in the AfCFTA to standardise procedures and advance in building capacity for customs and immigration officers to comply with the requirements of the agreement. Expanding the use of “green channels” (i.e. automatic clearance) for example can also be an effective tool in eliminating multiple and redundant verification. For example, data from 2016 shows that only 3% of imports into Egypt were cleared through a green channel (WTO, 2018[45]).

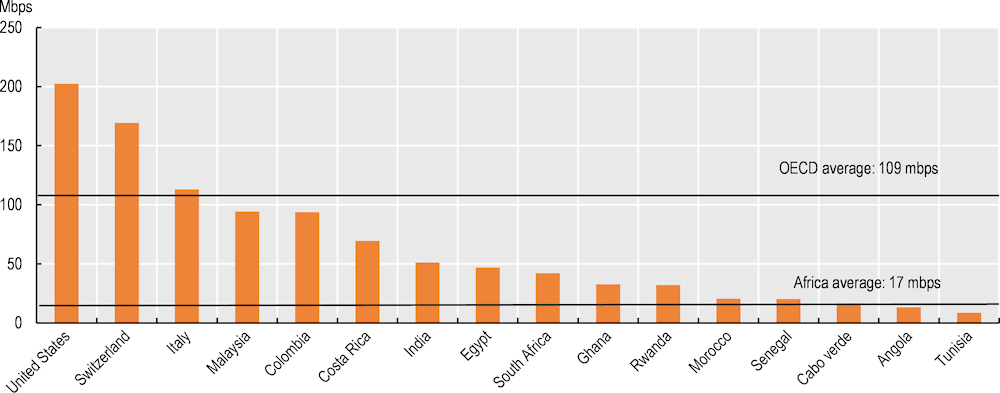

Advancing the digitalisation agenda will be key to future-proofing logistics in Africa. Expanding digital infrastructure, upgrading its quality and ensuring its affordability will also be critical to capture the opportunities opened up by the AfCFTA, particularly considering the increased opportunities in e‑commerce. Countries have been advancing fast in this respect, with digitalisation accelerated by the COVID‑19 pandemic. In Egypt, for example, an estimated 18 million more people used the internet in 2021 compared to 2019, with the proportion of the population increasing from 57% to 72%. Nevertheless, there is room for improvement. The average African broadband speed was 17 Mbps in 2023, six times slower than in the OECD (Figure 3.7). Continuing with the expansion of mobile technologies will also be critical, particularly as many consumers are mobile-first, and with mobile communications being a key technology for Industry 4.0. Coverage of 4G is currently 56% on average in Africa, with some countries close to full coverage, such as Egypt (98%) and others at below one-fifth of the population, such as Tanzania (13%). 4G coverage by comparison is 98% in OECD on average and 86% in EU-27 ((authors’ calculations based on (ITU, 2022[46])). At the time of writing, countries in Africa with commercial deployment of 5G – a crucial technology for the fast IoT needed for smart logistics for example – included Angola, Botswana, Kenya, Madagascar, Mauritius, Nigeria, Seychelles, South Africa, Tanzania, Togo, Zambia, Zimbabwe, who have deployed the technology in 312 locations. By contrast, in the EU 5G had been commercially deployed in over 60 000 locations (Ookla, 2023[47]).

Figure 3.7. Broadband internet speed, selected countries, 2023

Note: Simple country averages. Fixed broadband internet.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on (Ookla, 2023[47]), https://www.speedtest.net/global-index.

It is also important to activate innovation in the logistic value chain and move away from looking at connectivity as purely a matter of hard assets. Logistics is already being re-defined through the use of digital technologies. For example, the use of predictive analytics and AI is enabling real time tracing, with the possibility to link instantly demand, from the consumption point, to supply at the factory, while blockchain technologies are increasing transparency and making certifications easier. The physical internet for example aims to link different logistics networks with standardised protocol, modular containers, and smart sensors and interfaces so that resources can be shared and seamlessly integrated (Treiblmaier et al., 2020[48]). New players are emerging with innovative solutions both in the public and private sectors to connect firms and consumers more cheaply and faster (Box 3.5). Digital payment solutions are also taking root across the continent, with the country average in Africa for using digital payments at about 38% of the population in 2021, higher than 25% in 2020, but at less than half the average for OECD countries (93%) (authors’ elaboration based on (World Bank, 2022[41])). The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the use of such tools in the continent, aided also by regulatory frameworks that have been developed. In Egypt for instance, e-Payments Law No. 18/2019 was introduced to facilitate digital payments.

Box 3.5. Innovation in logistics: Examples from Africa’s e-logistics firms

Several Africa e-logistics start-ups aim to harness digital technologies to connect stakeholders along the supply chain and make transporting goods across the continent more efficient.

Kobo is an e-logistics start-up that connects cargo owners with freight needs with truck owners, launched in 2018 in Lagos, Nigeria. The platform, inspired by ride-sharing trends, has launched a technology platform that provides real time visibility for shippers and truckers. The firm relies on a network of about 50 000 trucks and has a physical presence in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria and Uganda. The firm is also expanding into financing services, such as payments, capital financing programmes for drivers and insurance.

Lori Systems is an on-demand logistics and trucking company that was launched in 2016 in Nairobi, Kenya, specialising in bulk grains, fertilisers, local and transit containers, steel, bitumen and fast moving consumer goods and offering real time tracking. It now operates in Congo DRC, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania and Uganda.

Source: (Wamunyu, 2021[49]), “AfCFTA & Digital Logistics Innovations: A Kobo Perspective”, Kobo, T-Talk presentation in the framework of the “PTPR Spotlight on Egypt: Harnessing the Potential of the AfCFTA”, held on 20 January 2022 and company websites.

References

[38] Afreximbank (2022), African Trade Report 2022: Leveraging the Power of Culture and Creative Industries for Accelerated Structural Transformation in the AfCFTA Era, https://media.afreximbank.com/afrexim/AFRICA-TRADE-REPORT-2022.pdf.

[44] Armstrong and Associates (2022), Global Third-Party Logistics Market Size Estimates, https://www.3plogistics.com/3pl-market-info-resources/3pl-market-information/global-3pl-market-size-estimates/.

[20] Asafu-Adjaye, J. et al. (2021), The role of the AfCFTA in promoting a resilient recovery in Africa, ODI, London.

[7] AUC/OECD (2023), Africa’s Development Dynamics 2023: Investing in Sustainable Development, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/3269532b-en.

[23] Conway, M. et al. (2019), “Should sub-Saharan Africa make its own drugs?”, McKinsey, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-and-social-sector/our-insights/should-sub-saharan-africa-make-its-own-drugs.

[31] DCVMN (2021), “Vaccine Manufacturing in Africa, DCVMN briefing document”, Developing Countries Vaccine Manufacturers Network briefing document, 17 March, https://www.dcvmn.org/Webinar-briefing-to-DCVMN-members-on-What-will-it-take-to-manufacturer-vaccines.

[34] ECDPM (2021), Connecting people and markets in Africa in 2021, https://ecdpm.org/work/connecting-people-and-markets-in-africa-in-2021.

[27] EFCG (2014), The API market (web page), European Fine Chemicals Group, https://efcg.cefic.org/active-pharmaceutical-ingredients/the-api-market/.

[24] EudraGMDP (2022), Database, http://eudragmdp.ema.europa.eu/inspections/displayWelcome.do.

[40] EY (2015), Cultural Times The First Global Map of Culutral and Creative Industries, Unesco Publishing, https://en.unesco.org/creativity/sites/creativity/files/cultural_times._the_first_global_map_of_cultural_and_creative_industries.pdf.

[8] Financial Times (2023), “fDi market database”, https://www.fdimarkets.com.

[10] GEWC (2022), Global Wind Report, Global Wind Energy Council, Brussels, https://gwec.net/global-wind-report-2022/.

[43] ICA (2021), Key Achievements in the financing of African infrastructure in 2019-2020, https://www.icafrica.org/en/topics-programmes/key-achievements-in-the-financing-of-african-infrastructure-in-2019-2020/.

[19] IEA (2022), Africa Energy Outlook 2022, International Energy Agency, https://www.iea.org/reports/africa-energy-outlook-2022.

[1] IEA (2022), Energy Statistics Data Browser, International Energy Agency, https://www.iea.org/data-and-statistics/data-tools/energy-statistics-data-browser?country=EGYPT&fuel=Energy%20transition%20indicators&indicator=ETISharesInPowerGen.

[9] IEA PVPS (2022), Trends in photovoltaic applications, https://iea-pvps.org/trends_reports/trends-2022/.

[3] IHA (2022), Hydropower Status Report: sector trends and insights, International Hydropower Association, https://assets-global.website-files.com/5f749e4b9399c80b5e421384/63a1d6be6c0c9d38e6ab0594_IHA202212-status-report-02.pdf.

[17] IRENA (2022), Five Ways the African Continental Free Trade Agreement Can De-risk the Continent’s Power Sector, https://www.energyforgrowth.org/memo/five-ways-the-african-continental-free-trade-agreement-can-de-risk-the-continents-power-sector/.

[2] IRENA (2022), Renewable Energy Statistics 2022, International Renewable Energy Agency, Abu Dhabi, https://www.irena.org/publications/2022/Jul/Renewable-Energy-Statistics-2022.

[12] IRENA and EIB (2015), Evaluating Renewable Energy Market Manufacturing Potential in the Mediterranean Partner Countries, https://www.irena.org/publications/2015/Dec/Evaluating-Renewable-Energy-Manufacturing-Potential-in-the-Mediterranean-Partner-Countries.

[37] ITC (2022), Made by Africa: Creating Value through Integration, International Trade Centre, Geneva.

[46] ITU (2022), Digital Development Dashboard (website), International Telecommunication Union, https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Dashboards/Pages/Digital-Development.aspx.

[29] Lartey, P. et al. (2018), “Pharmaceutical Sector Development in Africa: Progress to Date”, Pharmaceutical Medicine, Vol. 32/1, pp. 1-11, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-018-0220-3.

[11] Mathieu, L. and C. Mattea (2021), From dirty oil to clean batteries, European Federation for Transport and Environment AISBL, Brussels, https://www.transportenvironment.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2021_02_Battery_raw_materials_report_final.pdf.

[28] Narsai, K. (2021), “Strengthening Africa’s value chains”, Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance, T-Talk on 3 November 2021 in the framework of the PTPR of Egypt: Spotlight on the AfCFTA and Industrialisation.

[16] Odetayo, B. and M. Walsh (2021), “A policy perspective for an integrated regional power pool within the Africa Continental Free Trade Area”, Energy Policy, Vol. 156, p. 112436, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112436.

[36] OECD (2023), “Main Science and Technology Indicators”, OECD Science, Technology and R&D Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00182-en (accessed on 20 February 2023).

[6] OECD (2021), Middle East and North Africa Investment Policy Perspectives, https://doi.org/10.1787/6d84ee94-en.

[21] OECD/UN ECA (2020), “Africa’s Response to COVID-19: What roles for trade, manufacturing and intellectual property?”, OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/73d0dfaf-en.

[47] Ookla (2023), Ookla 5G map, https://www.speedtest.net/ookla-5g-map.

[22] Peprah Boaitey, K. and C. Tuck (2020), “Advancing health system strengthening through improving access to medicines: A review of local manufacturing policies in Ghana”, Medicine Access @ Point of Care, Vol. 4, p. 239920262096229, https://doi.org/10.1177/2399202620962299.

[48] Treiblmaier, H. et al. (2020), “The physical internet as a new supply chain paradigm: a systematic literature review and a comprehensive framework”, The International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 31/2, pp. 239-287, https://doi.org/10.1108/IJLM-11-2018-0284.

[13] UN Comtrade (2023), Database, https://comtrade.un.org/.

[42] UN ECA (2022), The African Continental Free Trade Area and Demand for Transport Infrastructure and Services, UN ECA, Addis Ababa.

[26] UNCTAD (2023), Unctadstat, https://unctadstat.unctad.org/EN/.

[39] UNCTAD (2018), Creative Economy Outlook Trends in International Trade in Creative Industries, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ditcted2018d3_en.pdf.

[33] UNECA (2019b), Healthcare and Economic Growth in Africa, https://repository.uneca.org/bitstream/handle/10855/43118/b11955521.pdf?sequence=4&isAllowed=y.

[35] UNESCO (2023), UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) Database, http://data.uis.unesco.org/.

[32] UNICEF (2022), COVID-19 dashboard and press reports, https://www.unicef.org/supply/covid-19-market-dashboard.

[30] US National Library of Medicine (2023), Clinical trials database, https://clinicaltrials.gov.

[14] USGS (2022), Copper Statistics and Information, National Minerals Information Centre, USGS, https://www.usgs.gov/centers/national-minerals-information-center/copper-statistics-and-information.

[4] Van den Berg, J. (2022), Wind Energy: Joining Forces for an African Lift-Off, https://africa-eu-energy-partnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/AEEP_Wind_Energy_Policy_Brief_2022-3.pdf.

[18] Van der Ven, C. and L. Signé (2021), Greening the AfCFTA: It is not too late, https://www.brookings.edu/research/greening-the-afcfta-it-is-not-too-late/.

[49] Wamunyu, K. (2021), “AfCFTA & Digital Logistics Innovations: A Kobo Perspective, T-Talk presentation in the framework of the PTPR Spotlight on Egypt: Harnessing the potential of the AfCFTA”, T-Talk presentation in the framework of the PTPR Spotlight on Egypt: Harnessing the Potential of the AfCFTA, Kobo.

[25] WHO (2017), WHO Global Surveillance and Monitoring System for Substandard and Falsified Medical Products, Geneva, World Health Organization, https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/326708/9789241513425-eng.pdf.

[5] WMO (2022), World Meteorlogical Organization Standard Normals, https://data.un.org/Data.aspx?d=CLINO&f=ElementCode%3A15 (accessed on 21 August 2021).

[41] World Bank (2022), Findex Database, https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/globalfindex.

[45] WTO (2018), Trade Policy Review: Egypt, Report by the Secretariat, World Trade Organization, https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tpr_e/s367_e.pdf.

[15] Yu, A. and M. Sumangil (2021), “Top electric vehicle markets dominate lithium-ion battery capacity growth”, SP Global Intelligence blog, 16 February, https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/blog/top-electric-vehicle-markets-dominate-lithium-ion-battery-capacity-growth.

Note

← 1. This includes the Southern African Power Pool (SAPP), Eastern Africa Power Pool (EAPP) Central African Power Pool (CAPP), West African Power Pool (WAPP) and North African Power Pool (NAPP).