The archipelago of the Azores is an Autonomous Region of Portugal and a European Union Outermost Region located in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. This chapter provides a snapshot on the past and current economic development of the archipelago by highlighting the progress made over recent years as well as the structural vulnerabilities that hamper future progress including remoteness, exposure to external shocks, high dependence on imports of essential goods and limited insertion in international markets.

Production Transformation Policy Review

1. The Azores in a nutshell

Abstract

A European and Portuguese hub in the Atlantic

The Azores (Portugal) is an archipelago of nine islands located in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, 1 500 km from the European continent and 2 000 km from the east coast of North America. Together with Madeira (Portugal), the Canary Islands (Spain) and Cabo Verde, it belongs to the geographic region of Macaronesia. The Azores account for 2.3% of the population of Portugal (236 000 inhabitants in 2021, 75% of which is located on the Islands of São Miguel and Terceira) and 2% of the national GDP (EUR 4 178 million in 2019). With a GDP per capita of EUR 19 100 PPP in 2020 (USD 20 600), it is, together with four other regions in Portugal, one of the EU’s 78 less developed regions, with a GDP per capita below 75% of the EU-27 average (INE, 2021[1]).

Since 2004 the Azores have been designated a European Outermost Region. Since 1976 the region has enjoyed autonomous status and has its own political and administrative organisation that includes a Regional Government and a Legislative Assembly, elected every five years. In practice, the autonomy is reflected in a set of prerogatives that include the possibility to legislate in areas spanning from agriculture and fisheries, to trade, industry, energy, tourism and fiscal policies (Law N.º 318-B/76 (30 April 1976), 1976[2]). Due to its geographical location off continent and the structural challenges associated with this, it is one of the nine European Outermost Regions (ORs). As such, the EU legislation provides specific support measures, including tailored application of EU law and access to EU programmes as well as ad hoc strategies (Box 1.1).

Box 1.1. The European Union Outermost Regions and their 2022 renewed strategy

The EU Outermost Regions (ORs) are nine European territories geographically located in the western Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean basin, the Amazonian forest and the Indian Ocean. They include French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, Mayotte, Reunion and Saint-Martin (France), Azores and Madeira (Portugal), and the Canary Islands (Spain). In total, they are home to 4.8 million citizens, equivalent to 1% of the EU total. Due to the idiosyncratic challenges related to remoteness, vulnerability to climate change, small market size and high economic dependence on the mainland, since 2004 the EU has provided specific measures for the EU ORs regarding the EU legislation in accordance with Article 349 of the Treaty of the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU).

With their rich biodiversity and unique ecosystems, the outermost regions provide unique assets for the EU as a whole in three geographical areas.

The European Commission adopted on 3 May 2022 a Communication on “Putting people first, securing sustainable and inclusive growth, unlocking the potential of the EU’s outermost regions”. The Strategy for the outermost regions focuses on:

1. Putting people first – improving living conditions for people in the outermost regions, ensuring people's quality of life, tackling poverty and developing opportunities for the youth.

2. Building on each region’s unique assets such as biodiversity, blue economy or research potential.

3. Supporting a sustainable, environmentally friendly and climate-neutral economic transformation grounded on the green and digital transitions.

4. Strengthening outermost regions' regional co-operation with neighbouring countries and territories.

Source: European Commission (2022[3]), Putting people first, securing sustainable and inclusive growth, unlocking the potential of the EU’s outermost regions, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/communications/2022/putting-people-first-securing-sustainable-and-inclusive-growth-unlocking-the-potential-of-the-eu-s-outermost-regions

An ocean territory aspiring to rebuild its international standing

Once central to international trade routes, the Azores are now aspiring to regain a prominent international role (Governo Regional dos Açores, 2021[4]). Since the beginning of human settlement in the 15th century, the Azores relied on their strategic location as a gateway for commercial navigation that connected Europe to America, Africa and Asia. However, the vulnerability to external factors, the natural fragility of the archipelago and global technological progress pushed the Azores towards relative isolation over time.

The ocean and the specific climate conditions induced by the Gulf Stream with subtropical climate and mild temperatures all year long have been central to the economic development of the archipelago, which has been historically associated with fishing, including whale catching, agro-food and shipping services. The region exported wheat until the middle of the 20th century, ink plants in the 17th and 18th centuries and oranges in the 19th century, a luxury good whose main destination was England. In addition, tea, introduced in the middle of the 19th century from the People’s Republic of China, also found the Azores an ideal environment to grow, and the region today still hosts the only commercial production facility in Europe. However, the combination of increased competition from other countries and the upsurges of different plagues, like the Coccus Cochonilha, a pest that decimated the citrus production, severally affected and reshuffled the agro-food system over time.

Located on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge the archipelago is subject to different geological and meteorological hazards (Gaspar et al., 2011[5]). Since the beginning of human settlement, more than 30 important earthquakes, countless seismic crises and extreme weather events, such as the 2019 hurricane Lorenzo and the more recent earthquake swarm in 2022 in São Jorge Island, have affected the archipelago, challenging supply-chain activities and damaging essential infrastructure, including ports.

Improved oceanic navigation techniques and technological developments, such as steam engines, made the archipelago less central to international sea routes, challenging local development opportunities and contributing to depopulation (Haddad et al., 2015[6]). Consequently, from the early 19th century, several migration waves contributed to the emergence of Azorean communities abroad, mostly in Brazil, Canada and the United States. The establishment of an important diaspora community in the United States was consolidated when in 1958, following the volcanic eruptions of the Island of Faial, the United States Congress approved the Azorean Refugee Act, sponsored by senator John Kennedy of Massachusetts, authorising non-quota visas for displaced Portuguese citizens. According to the most recent estimates 1.4 million Portuguese-Americans – the vast majority with Azorean descendants – live in New England, Massachusetts, California and Hawaii (US Census Bureau, 2020[7]). These communities account for much as five times the current population of the region and represent an important legacy and cultural connection that strengthen the international visibility of the archipelago.

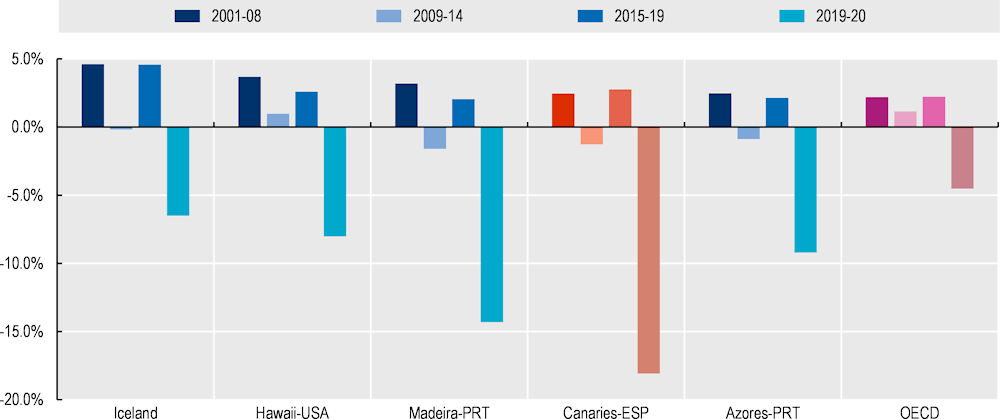

Together, the support from EU and National Institutions cushioned the effect of the Azores’ increased isolation over time. The region experienced some economic progress and in the early 2000s it showed a significant level of convergence towards the EU average. GDP per capita moved from 68% to 75% of the EU average. In 15 years, the productivity gap with respect to the EU-27 average also slightly improved, moving up from 58% in 2004 to 61% of the EU-27 average in 2019 (Eurostat, 2022[8]). Economic growth was mainly driven by investments in infrastructure and construction, which also benefited the nascent tourism sector (Haddad et al., 2015[6]). The region observed an infrastructure boom. In fact, 70% of a total 25 000 construction projects built in the Azores in 2000-19 were concentrated between 2000 and 2008 (SREA, 2022[9]). From 2009-14, GDP convergence to the EU average slowed due to the economic and financial crisis of 2008-09 and the European debt crisis of 2012‑13. From 2014, counter-cyclical measures partially cushioned the negative effects of the crisis and the rebound of the economy from 2015 onwards was driven by the partial liberalisation of air transport and the expansion of tourism. While the incidence of tourism on the regional economy is less prominent with respect to other EU ORs, such as Madeira and the Canaries, over the 2010-19 period the number of tourists increased almost threefold, from 380 000 to 970 000 (SREA, 2022[10]). COVID-19 severely affected tourism in the region. After a sharp drop of 70% of total arrivals in 2020, tourism only partially rebounded in 2021 with total turnover still 65% below pre-pandemic levels. As a consequence, in 2019-20 GDP dropped by 9%, in line with the national trend, double the OECD average, but still less when compared with other EU ORs like Madeira and the Canaries (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Average GDP growth, Azores, selected regions and countries, 2000-20

Note: 2020 is provisional. For Hawaii, original chain constant price estimates are referenced to 2010, and for other regions and countries 2015.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD National Accounts, OECD Regions and Cities, https://stats.oecd.org/ and national and regional statistical offices. Canaries, http://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac; Azores and Madeira, https://www.ine.pt; Hawaii, http://dbedt.hawaii.gov.

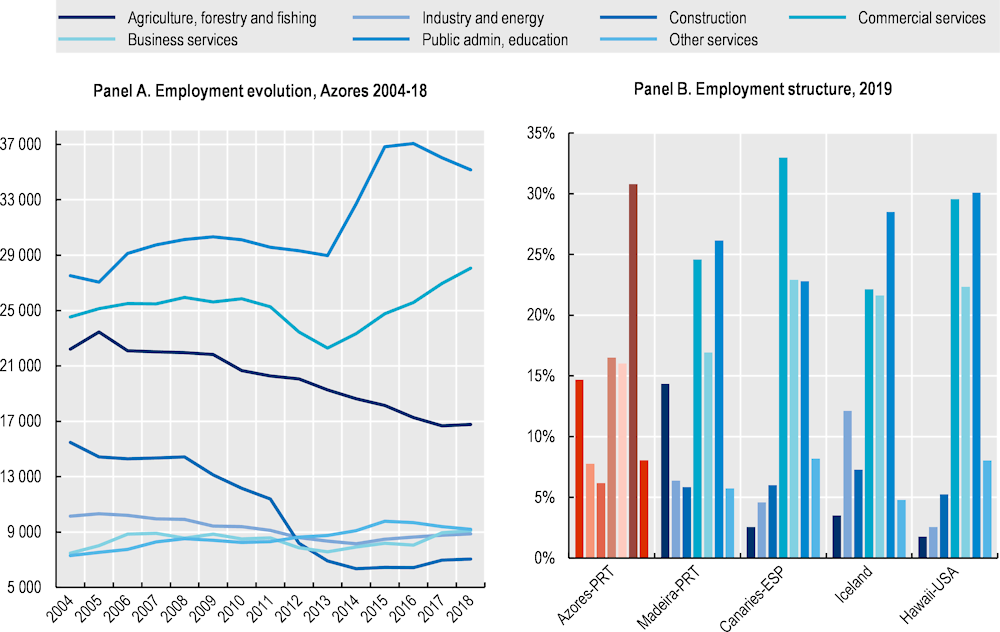

Today the economy of the Azores is mainly specialised in services activities, which in 2019 accounted for 75% of total GDP and 71% of total employment. Public administration accounts for 32% of employment – 7 percentage points more with respect to 2004 – and 25% of GDP, followed by commercial services, with 25% of employment and 16% of GDP. Business services, which include more sophisticated activities such as scientific and technical support, remain limited, accounting for 16% of employment and 20% of GDP. These figures are lower than other insular ecosystems such as the Canaries (Spain), Iceland and Hawaii (United States) (Figure 1.2). The rest of the economy relies on agriculture, forestry and fishing, which employ around 15% of the workforce and contribute 9% of GDP, whereas industry remains marginal with 5% of regional GDP, and mostly relates to food processing.

Figure 1.2. More than 70% of jobs are in services

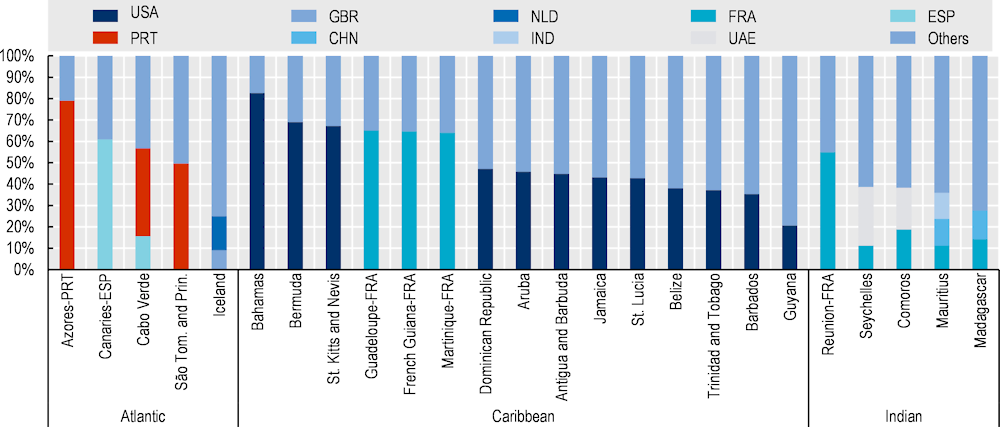

Remoteness makes economic ties with mainland Portugal and the EU pivotal assets for the regional economy. Portugal accounts for 80% of total trade for the Azores, a figure that is above other EU ORs, including the Canary Islands or Guadeloupe (Figure 1.3). Besides being located far from the European continent the Azores face additional challenges such as isolation from the main commercial trade lines and from third-country markets, exacerbated by the isolation of the scattered archipelago. The Azores are largely dependent on imports of both intermediate and final products such as food, machinery and equipment, and fuels.

Figure 1.3. Mainland Portugal accounts for 80% of the Azores’ trade in goods

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Nationals Institute of Statistics, UN COMTRADE, https://comtrade.un.org/.

Note: For Madeira there is no available information for intra Portugal trade.

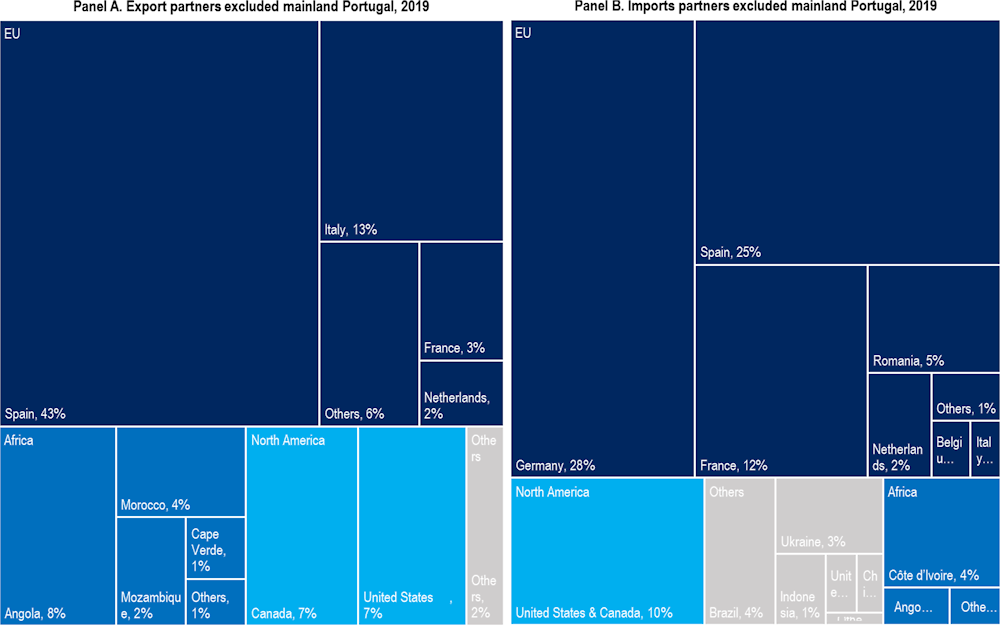

International trade in goods currently plays a marginal role in the regional economy, but exports are growing. International trade in goods has remained at around 15% of GDP over the last ten years. Exports increased from EUR 77 million to EUR 132 million (+70%) and imports from EUR 127 million to EUR 142 million (+12 %) over 2009-21. These trends positively affected the foreign trade balance, which, despite remaining negative, improved from -6% to -2% from 2009 to 2019. In addition to the EU, which accounts for 73% of total trade, North America and Africa are the main trade partners, at 11% and 9% respectively. The Azores specialise in exporting agricultural and food products (including fish and related products, meat, and both fresh and processed dairy products) which account for 72% of total exports, up from 68% in 2009. The main destinations in the EU, beyond mainland Portugal, are Spain, Italy, Denmark and the Netherlands. Outside the EU, top destination markets are North America and Africa (mostly Morocco, Angola and Mozambique). On the other hand, 60% of imports are concentrated in agro-food products, such as feed for livestock and other intermediary products for local agro-food processing as well as consumer products for households, followed by capital goods, such as machinery equipment and vehicles at 25%. The region mostly imports from the EU (Germany, Spain and France) and the United States (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4. Beyond the EU, North America and Africa are the main trade partners of the Azores

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Regional Statistical Office of Azores (SREA), https://srea.azores.gov.pt/.

References

[3] European Commission (2022), Putting people first, securing sustainable and inclusive growth, unlocking the potential of the EU’s outermost regions, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/communications/2022/putting-people-first-securing-sustainable-and-inclusive-growth-unlocking-the-potential-of-the-eu-s-outermost-regions.

[8] Eurostat (2022), General and regional statistics, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/explore/all/general?lang=en&display=list&sort=category (accessed on 11 April 2022).

[5] Gaspar, J. et al. (2011), Geological Hazards and Monitoring at the Azores (Portugal) -, Earthzine, https://earthzine.org/geological-hazards-and-monitoring-at-the-azores-portugal/ (accessed on 2 May 2022).

[4] Governo Regional dos Açores (2021), Programa do XIII Governo Regional dos Açores, https://portal.azores.gov.pt/en/programa-xiii-governo (accessed on 17 March 2023).

[6] Haddad, E. et al. (2015), “Multipliers in an island economy: The case of the azores”, The Region and Trade: New Analytical Directions, pp. 205-224, https://doi.org/10.1142/9789814520164_0008.

[1] INE (2021), Censos 2021 - Divulgação dos Resultados Provisórios, https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_destaques&DESTAQUESdest_boui=526271534&DESTAQUESmodo=2 (accessed on 6 April 2022).

[2] Law N.º 318-B/76 (30 April 1976) (1976), Political and Administrative Statute of the Autonomous Region of the Azores, http://www.alra.pt/documentos/estatuto_ing.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2022).

[9] SREA (2022), Construction and housing statistics, Annual statistical series, https://srea.azores.gov.pt/Conteudos/Relatorios/lista_relatorios.aspx?idc=6194&idsc=6708&lang_id=2 (accessed on 7 April 2022).

[10] SREA (2022), Tourism statistics, https://srea.azores.gov.pt/Conteudos/Relatorios/lista_relatorios.aspx?idc=6194&idsc=6712&lang_id=1 (accessed on 12 April 2022).

[7] US Census Bureau (2020), 2019 American Community Survey Single-Year Estimates, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2020/acs-1year.html (accessed on 8 April 2022).