Once central to international trade routes, the Azores are now aspiring to regain a prominent international role. This chapter provides an analysis of the policy support for internationalisation of the region and identifies future opportunities and reforms that should leverage its unique geographical, natural and historical attributes in three pivotal economic areas: agro-food, ocean economy and renewable energies.

Production Transformation Policy Review

2. Options for a sustainable internationalisation of the Azores

Abstract

Prioritising investments to seize the opportunities of EU multi-annual planning and financing

Regional, national and EU support are crucial to cushion the effect of the Azores’ structural vulnerabilities. In particular, the autonomy and Outermost Region (EU OR) status provide policy space to tackle the structural handicaps in the form of compensating measures such as subsidies, exemptions and special provisions. For example, in 2021, the regional parliament approved a reduction of 30% of personal income tax (PIT) and corporate income tax (CIT) and decreased value added tax (VAT) from 18% to 16% to support the post-pandemic recovery. The region also benefits from measures to ensure territorial continuity via subsidised fare rates for residents on flights to the mainland, in line with the EU Public Service Obligation. As an EU OR, the Azores benefit from specific conditions and higher co-financing rates from most of the EU funds and programmes compared to other regions. Together, the Portuguese Government and European Commission, although subject to some variations, finance 50% of the budget of the Regional Government (Região Autónoma dos Açores, 2021[1]; Dentinho and Fortuna, 2019[2]).

The EU cohesion policy funds since 1978 have not only sustained economic growth and modernisation in the Azores, but have also enabled the Regional Government to increase local institutional capacities to plan and manage long-term projects. The Regional Government has shown over time an increased aptitude to co-ordinate, design and implement complex projects with specific conditionalities together with national and EU institutions. This has also contributed to improving the efficiency of funds disbursement. For example, the disbursement rate of the ERDF and ESA funds in the Azores is, at 77%, above the EU average of 63%.

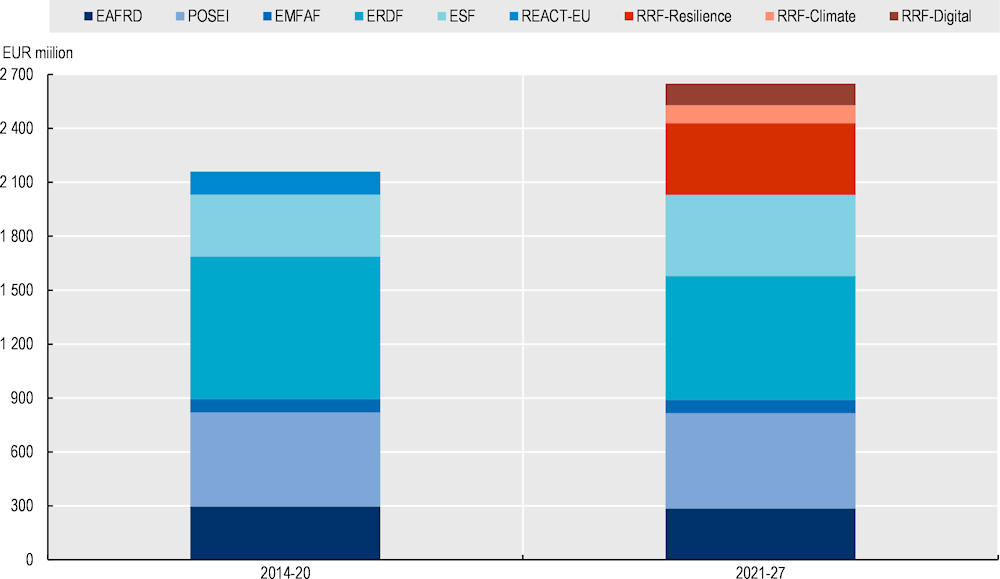

The new EU programming period 2021-27 matched with additional resources from the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) opens up new opportunities for the Azores. In addition to the traditional European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), European Social Fund (ESF), European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) and the European Maritime Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund (EMFAF), the EUR 800 million from the RRF provides a unique occasion for the Azores to continue its progress of convergence towards a sustainable and equitable economy. The new resources will increase financing from the European Commission by 22% with respect to the 2014-20 Multiannual Financial Framework (Figure 2.1). The RRF provides financing until 2026 to fast-track reforms to mitigate the economic and social impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic and make the European economy more sustainable and resilient. It includes several pillars that essentially aim to support green, cohesive and resilient economic growth. The Azores benefit from the RRF resources through the Portuguese National Resilience Plan (Ministerio do Planeamento, 2021[3]; European Commission, 2021[4]). 65% of the RRF are associated with the resilience pillar with both a social and competitive component, 19% with digital transition including education and modernisation of public infrastructure, and 16% with green transition including the expansion of renewable energy capacity and the development of the Azores Ocean Cluster (Cluster do Mar dos Açores). An additional EUR 117 million are also earmarked for the Azores, for the capitalisation of companies through the Portuguese National Development Bank (Banco Portuguese de Fomento- BPF) (Azores Government, 2021[5]).

Figure 2.1. The RRF will provide additional resources to the Azores

Note: ERDF - European Regional Development Fund, ESF - European Social Fund, POSEI - Special Agricultural Programme, EAFRD - European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development, EMFAF - European Maritime Fisheries and Aquaculture Fund, REACT-EU - Recovery Assistance for Cohesion and the Territories of Europe, RRF - Recovery and Resilience Fund. The figures for 2021-27 are preliminary until approval of ERDF/ESF and EARDF Operational Programmes.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Portuguese National Cohesion and Development Agency, https://www.adcoesao.pt/; Azores Operational Programme 2014-2020, http://poacores2020.azores.gov.pt; National Recovery and Resilience Plan, https://recuperarportugal.gov.pt; Rural Development Plan, https://proruralmais.azores.gov.pt; and 2022 Renewed Strategy for the EU's Outermost Regions, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_22_2727.

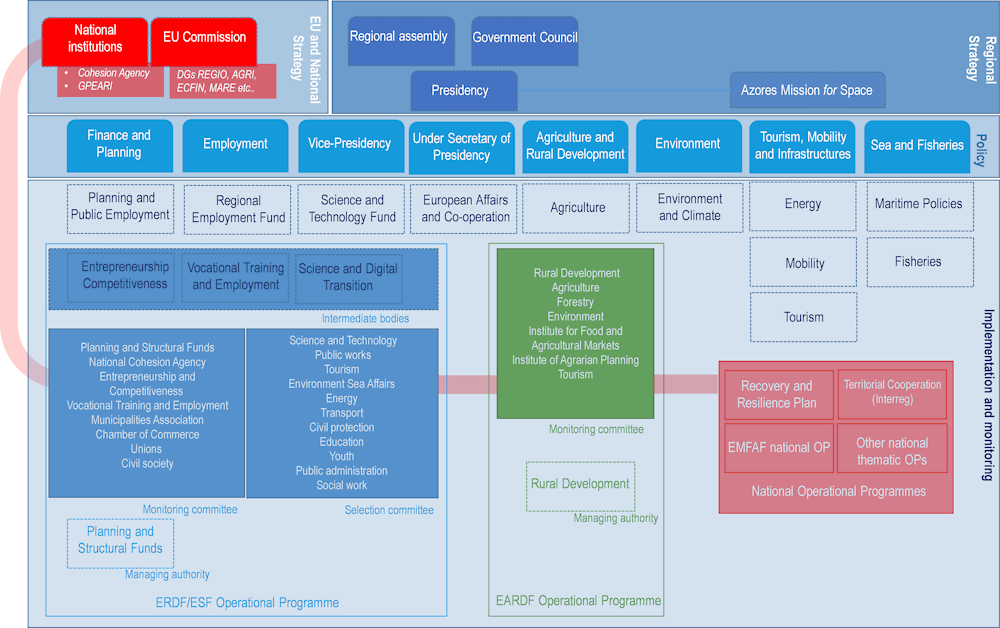

Several institutions are in charge of different areas of internationalisation and production transformation (Figure 2.2). Currently, the external co-operation and political affairs are co-ordinated by the Under Secretary to the Presidency, whereas economic affairs such as attraction of investment as well as planning, management and implementation of EU cohesion policy funds are under the responsibility of other Secretariats. The Regional Secretary of Planning and Finance and the additional directorates are in charge of the ERDF/ESF Operational Programme that account for 60% of total earmarked EU funds. The Directorate for Planning and Cohesion Policy Funds is the managing authority. It co-ordinates, along with the other line directorates, the implementation, selection and monitoring of the funds to secure coherence in planning and implementation. Another important regional programme is the EARDF Rural Development Programme. It is managed by the Rural Development Directorate under the Secretary for Agriculture. The regional authorities are also engaged within the framework of other EU funding schemes. These include the Interreg-Macaronesia (MAC), managed by the Canary Islands, and in co-operation with Madeira, Mauritania, Senegal and Cabo Verde and other national operational programmes associated with other funds such as the EMFAF.

Figure 2.2. Governance for internationalisation and economic transformation, Azores 2022

Note: The representation is not meant to be exhaustive. Rather it is intended to provide an overarching governance structure of the Azores Regional Government associate to economic transformation.

Source: Authors’ elaboration.

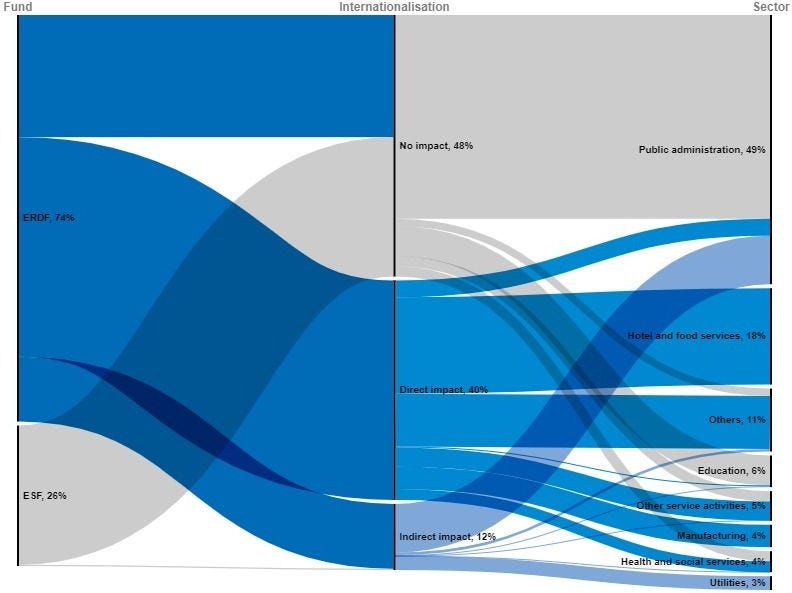

Internationalisation is an important component of the Azores’ planning for EU cohesion policy funds that could be modernised and strengthened. A granular analysis of the 2014-20 ERDF and ESF operational programme of the Azores shows that more than 50% of the resources are channelled either directly or indirectly to supporting the internationalisation strategy (Figure 2.3). These measures include several areas of intervention and beneficiaries. Indirect measures include specific actions that support the development of public goods such as the transition to a low-carbon economy, climate change and environmental protection. Direct measures to foster internationalisation include the co-financing of grants and loans to the private sector and research institutions or fiscal incentive schemes channelled via public administration like the Competir+ scheme under the Regional Directorate for Support to Investment and Competitiveness (DRAIC).

Figure 2.3. More than 50% of the ERDF and ESF funds in 2014-20 supported internationalisation

Note: Direct impact on internationalisation includes the Investment priorities (IP) 1.01, 1.02, 3.01, 3.02, 3.03 and 3.04 whereas indirect impact includes 4.01, 4.02, 4.03, 4.05, 5.01, 5.02, 6.03, 6.04, 6.05, 7.02, 7.03, and 8.05. The figure does not consider the funds of the REACT-EU facility.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Operational Programme “Regional Azores 2014-2020”, http://poacores2020.azores.gov.pt/.

However, while it is important to take into account the archipelago nature of the Azores and the need to leave no one behind, the current compensation logic through subsidies might create dependency and distortion while at the same time limiting the region’s capacity to benefit from multi-annual resources (OECD, 2020[6]). It also makes it difficult to mobilise private co-funding for transformative regional projects and to identify pivotal game changers that will require more innovation and competitiveness. At the same time, the design of policies and instruments may require more synergies and co-ordination in different areas and between funds. Moving forward, some limitations need to be taken into account for planning and project identification:

Prioritisation of activities and policy actions remains anchored to traditional sectors that may have limited spillover effects on the economy. For example, almost 20% of total ERDF/ESF resources from the 2014-20 programming were channelled to activities associated with commercial activities such as restaurants and hotels, followed by services activities related to tourism promotion such as local associations and chambers of commerce with 11%. Taking into account all measures that address the internationalisation potential of the Azores, tourism related activities absorb almost 70% of resources. Although tourism is and will remain an important activity, there are opportunities to enhance internationalisation through a more balanced and diversified economy in areas that are less exposed to external shocks, more innovation-oriented and with high spillovers on other sectors. Currently only 1% of internationalisation measures affect scientific and knowledge-intensive services that traditionally show high returns and economic spillovers.

There is a risk of duplication, redundancy and dispersion of resources. For example, in 2014-20 the ERDF funds were used to support similar activities across multiple islands such as the creation of seven start-up and business incubators which operate in isolation without an overarching co‑ordination. The large number of projects and priorities within each Operational Programme amplifies this issue. For example, the ERDF/ESF Programme shows that the Azores designed policy intervention and instruments in 35 out of 38 available policy priorities. This could create a large number of micro projects with limited impact as well as make it more difficult for beneficiaries to understand and navigate through the several financing and support measures.

The regional authorities are putting in place additional efforts to improve the design and implementation of measures that could tackle the above-mentioned issues. For example, for the 2021-27 programming, there are currently specific and ad hoc instruments under study that could lead to greater impact such as more complementarity between ERDF and ESF as well as grant disbursements conditioned to effective results. To shift from a compensation to a transformative approach in prioritisation, design and implementation, the following areas of intervention seem the more relevant:

Increase co-ordination at both policy and implementation level. In order to leverage the potential of internationalisation as an instrument of effective economic transformation it will be important to narrow the prioritisation of intervention to a few macro areas such as digital and environmental transitions that could lead to greater long-term impact and results. In doing so, there should be a better co-ordination of different policy and implementation authorities. For example, the institutions of agricultural, rural development and maritime affairs should be integrated in the different committees of the ERDF and ESF programmes and vice versa. The same should apply for the local institutions in charge of international and EU affairs at political level to secure a greater co-ordination with partners including the other Outermost Regions.

Make the most of the synergies between the recovery plan and cohesion policy funds. The RRF and cohesion fund regulations provide room for complementarities between policy actions and coherence in project pipelines. For example, the RRF could support areas that are not priorities under the ERDF/ESF. The two funds could also address different beneficiaries, with the RRF targeting public beneficiaries and the ERDF targeting private ones. At the same time, the different time frames of the funds could expand the life of projects by up to a decade. The shorter timeframes for the results of the RRF that must be achieved by 2026 could be complemented with further actions financed by the cohesion policy since the eligibility horizon extends until 2029 (European Institute of Public Administration (EIPA), 2022[7]). In the case of the ERDF/ESF Operational Programme, for example, several measures show complementarity and could be strengthened, particularly in the case of innovation activities under the smart specialisation strategy (RIS3) in which, for example, the improvement of research infrastructures and equipment funded under the ERDF could be supported by ad-hoc initiatives for training and networking via the ESF. The RIS3 could also be used as a benchmark for the entire development strategy of the archipelago, including activities associated with the ocean, sustainable agriculture and renewable energies. At the same time, there is room to improve the cross-fertilisation among different operational programmes and parallel funds. For example, in the case of ICT infrastructure the ERDF could support the overarching infrastructure and the EARDF could be in charge of local extension in remote areas.

Strengthen the capacity building and institutional development of both public administration and potential beneficiaries. Prioritisation planning and implementation of policies often require navigating complex procedures and rules that might change over time, such as in the case of the differences between the EU programming periods 2014-20 and 2021-27. Supporting the local authorities with ad hoc technical capacity building will be an important area of intervention that could involve authorities at national and EU level (OECD, 2022[8]). At the same time, local authorities could implement proactive action in support of potential beneficiaries in presenting high quality projects. For example, the national Operational Programme for Sustainability and Efficient Use of Resources (PO SEUR) – has put in place proactive actions to support the quality of projects presented by potential beneficiaries through a dense network of policy officers that provide updated information on the possibilities associated to the EU cohesion policy funds.

Making the most of internationalisation by leveraging uniqueness

The geographical, natural and historical uniqueness of the Azores could be used to turn the region into a relevant player to identify new sustainable solutions for internationalisation, while at the same time opening up opportunities for local development (OECD, 2022[9]; OECD, 2020[6]).

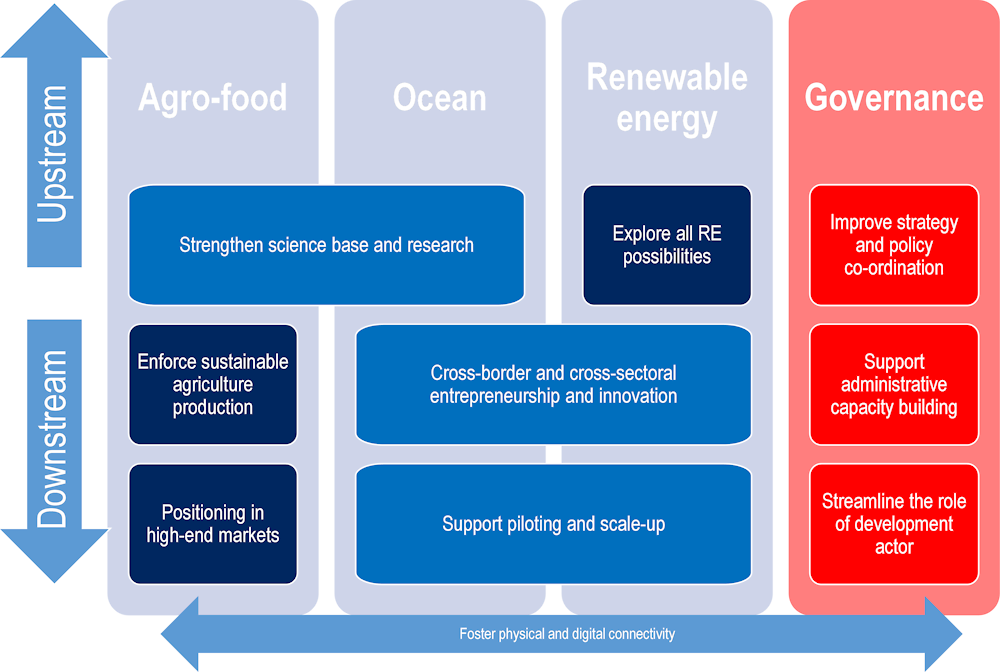

The peer review process of the PTPR on the Azores identified three potential areas for internationalisation and value chain participation that are particularly relevant for the regional economy and which reflect the specific uniqueness of the Azores in the future: agro-food, the ocean economy and renewable energies. Nevertheless, to make the most of them a renewed and expanded international partnership is needed including with national and EU partners, and in co-operation with emerging and developing countries, in particular SIDS. The latter face comparable challenges to the Azores including the relevance of the ocean in their economies and the exposure to external shocks in agriculture and energy prices. These specific industries and value chains are pivotal to ensure the environmental sustainability of consumption, production and trade and, at the same time, embed the larger spillover effects in other important activities for the region such as sustainable tourism (OECD, 2022[10]). They will help preserve the local ecosystem, whose vulnerability is increased by the growing frequency and disruptiveness of extreme meteorological events, and ensure competitiveness in key areas, including tourism, agro-food and ocean-related activities. Sustainability will also be key to reducing economic vulnerability, as 90% of total energy supply in the region relies on imported fuels, and 60% of regional imports are in agro-food, making the local ecosystem highly vulnerable to external shocks (Direcao Geral de Enrgia e Geologia, 2022[11]; SREA, 2022[12]). The following sections provide a snapshot on the current strengths, challenges and opportunities for internationalisation in the three identified value chains.

Preserving sustainability and prioritising high-end markets in agro-food

Agro-food value chains are changing globally. Emerging trends, accelerated by the pandemic, and rising global tensions point towards enhanced self-sufficiency and sustainability. Access to food is a growing concern as disrupted agro-food trade pushes staple prices up. In April 2022, food prices were 34% higher than the same period in 2021 and crude oil prices had increased by around 60%. Gas and fertiliser prices more than doubled, challenging food security especially in the poorest areas (FAO, 2022[13]). Prior to the pandemic, new trends were also emerging, including growing consumer attention to the traceability, nutritional, health and environmental impact of food products. The market for healthy food is growing. The global market for natural and organic cosmetics reached USD 18.5 billion in 2020 and is expected to increase to USD 32.3 billion by 2027. Food systems are a major stress for the environment, accounting for between 21-37% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. Extreme and unpredictable events caused by climate change are putting pressure on production, particularly commercial fruits and vegetables that can only be grown in specific ecosystems. Global production is also challenged by climate change-induced shifts in pest and diseases patterns (FAO, 2021[14]; OECD/FAO, 2021[15]; OECD, 2021[16]; Research and Markets, 2021[17]). For the Azores, this implies an updated model that points to diversification of production and the discovery of high-value end markets.

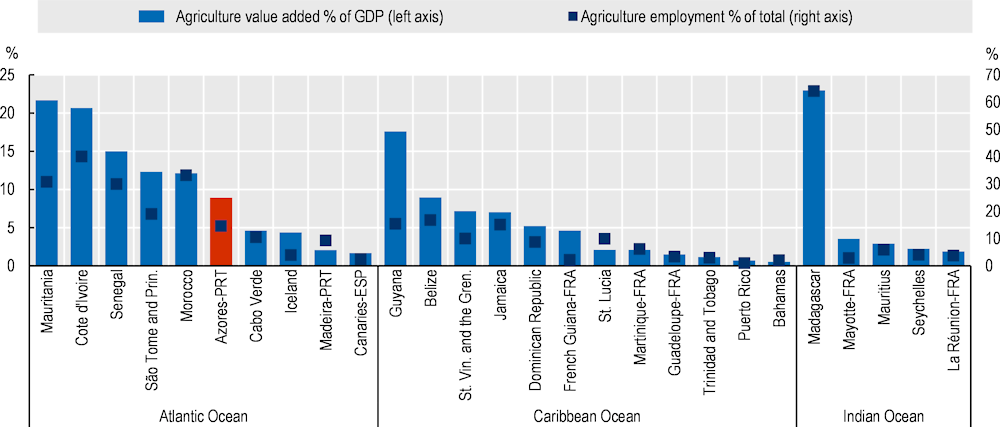

Agro-food is one of the main pillars of the Azores’ economy. Despite its decline in relative terms, mostly due to the rise in services and the development of tourism in the last decade, agriculture plays an important role, particularly when compared with other EU ORs (Figure 2.4). Agriculture contributes 9% of regional GDP and absorbs 15% of the labour force, whereas in other EU ORs it accounts for 3% of GDP and 10% of the labour force, on average. In the Azores, agricultural production mostly relates to family-run small farms, which account for 80% of the total. Agro-food is also the backbone of regional exports, accounting for 80% of total regional exports. Over the last two decades, new niche high-quality products emerged in the regional export basket including subtropical fruits like pineapple and globally recognised volcanic wines. Food processing is particularly challenging due to the high costs related to insularity, including transport, time to market and limited production capacities. As such, successful companies tend to integrate production stages and pursue economies of scope rather than scale. This is the case for dairy production, fish and wine, which are often organised in cooperatives that aim to reduce the dependency on foreign markets for intermediate inputs and reduce shipping costs. Despite these developments, the Azores’ agro-food system is essentially led by two main segments: livestock farming and fishing activities.

Figure 2.4. In the Azores, agriculture is more relevant than in other Outermost Regions

Note: 2018 for Guadeloupe, Reunion, Martinique, Mayotte, French Guiana; 2019 for the Canaries, the Azores, Madeira and EU-27.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD Regional statistics https://stats.oecd.org; French Portuguese and Spanish National Regional Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies, https://www.insee.fr, https://srea.azores.gov.pt/, https://estatistica.madeira.gov.pt/, http://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/istac.

Livestock farming accounts for 80% of total agricultural output. Of the 50% of the total Azores territory that is occupied by agriculture, pasture takes up 80%. In 2019, 82% of total agricultural output was associated with the production of milk, dairy products and meat, making the archipelago essentially a monoculture agriculture system. Despite the relatively small farm size – 8.9 ha, equivalent to half of the EU average, the Azores are an important milk producer that accounts for more than 30% of total Portuguese production. This is mainly associated with the transition of the EU milk quota. From 2008 until 2015, the reduction of milk produced in mainland Portugal allowed the expansion of the production in the Azores within the national EU quota. After the end of the quota system in 2015, the expansion of production to the natural capacity of the Azores islands allowed an increase in milk production of more than 30 million litres. However, even if the average productivity per cow, 7.3 t/l, grew by 17% in 2011-20, it remains below the national average of 8.6. Milk and dairy production is concentrated on two islands: São Miguel (89%) and Terceira (11%) and the dairy processing plants correspond to 11% of total Portuguese output, with cooperatives leading. Both in São Miguel and Terceira two cooperatives specialise in different dairy products for the domestic market, collecting 40-45% of the milk produced, whereas a large private company, collecting around 20-25% of the milk, focuses mainly on the foreign markets (de Almeida, Alvarenga and Fangueiro, 2021[18]).

Although monoculture farming brings advantages associated with productivity maximisation, pursuing scale economies and consequently reducing unit cost even for a small archipelago, several challenges are associated with it. Monoculture farming faces difficulties related to pest infestations, erosion of the natural balance of soils and decrease in biodiversity (Earth Observatory System, 2020[19]). These economic activities in the Azores face additional challenges associated with the lack of infrastructure, increasing cost of imports of animal feed and low profit margin at farm level in comparison to continental competitors due to transport costs. For example, all things being equal, some estimates indicate that the cost of transport for each kilogramme of meat to the mainland from the Azores is EUR 2 more expensive compared to a competitor in mainland Portugal (Autoridade Tributária Aduaneira, 2021[20]). In addition, agro-food in the Azores is particularly subject to climate-change hazards. In the most adverse scenario, estimates consider that 90% of local plant and animal species could be at risk of losing a suitable climate environment (Alatalo, Jägerbrand and Molau, 2014[21]).

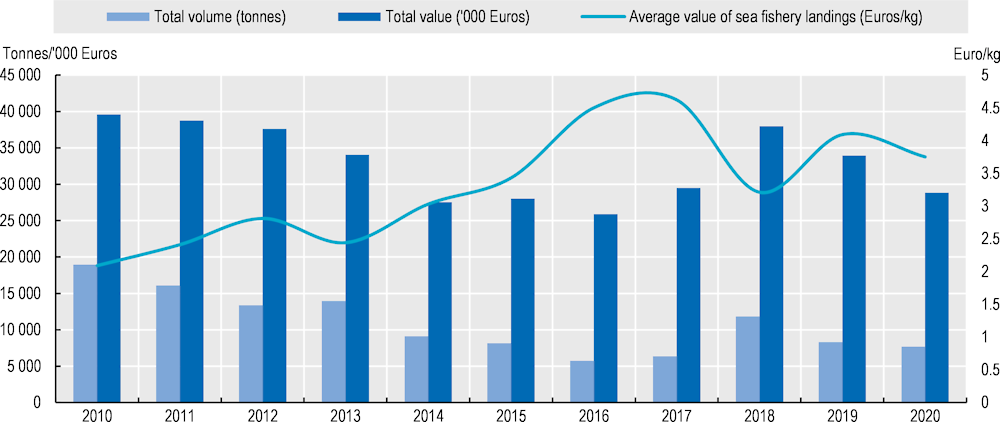

Small-scale and sustainable fishing point to an emphasis on quality over quantity. Located in a privileged point of passage on the migratory route of many marine animals, and due to the temperature of the waters and volcanic origins, the Azores present ideal conditions for the reproduction of fish species. The fishing activities in the Azores are dominated by small-scale boats – less than nine meters long – using artisanal and traditional methods. These account for 65% of total vessels and are mainly active on the coastal area given the limited narrow belt of shallow water around the islands. Considering the limited market size, only 15% of fresh fish is consumed locally, whereas the remainder is exported to mainland Portugal or third countries. Only 4% is intended for local processing, mainly canned tuna. With an average 8 000 tonnes caught, with high levels of variability and a value of EUR 31 million between 2015 and 2020 (Figure 2.5), Azorean fisheries account for 8% of national production and contribute to 14% of total value (SREA, 2022[12]). The increase of the average price has been driven by several factors, including global demand. Consumers globally are increasingly paying attention to the quality and sustainability of fishing methods that preserve the natural biological behaviour of fish. For example, greater care in handling and conservation have led to major improvements in the quality of the fresh product, gaining globally recognised certification such as Naturland and Friends of the Sea (European Commission, 2017[22]; Fauconnet et al., 2019[23]). However, several challenges persist for fishing activities in the Azores. The poor qualifications of fisherman, with limited business management capacities, hinder diversification possibilities and catch techniques. Likewise, infrastructure for supporting the development of non-fresh storage is lacking. Illegal fishing practices threaten the sustainability of the local fish value chains. Moreover, the volatility in catches hampers investments in the downstream processing industry (ORFISH, 2016[24]).

Figure 2.5. The value of fish landings has increased

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Portuguese National statistical office, (INE) 2022, https://www.ine.pt.

Regional, national and EU funds are central to the development of the agro-food sector in the region (Polido, João and Ramos, 2016[25]). For example, the region received 46% of the European Union funds allocated to Portugal to support milk producers. The Regional Government strongly supports milk production in the Azores, through subsidies fixed annually according to the regional budget, in order to offset the increased transport costs of raw materials and products. In 2018, the amount of the subsidy was EUR 6/1000 l.

The EU resources are channelled through three main funds. The Azores benefit from the specific measures and scheme for agriculture in favour of the regions of the Union (POSEI) that replace the measures of the first pillar of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). POSEI, with a yearly contribution of EUR 77 million, of which 75% for milk and cattle, aims at guaranteeing the supply to the Outermost Regions of essential agricultural products, securing the development of the livestock and crop-diversification sectors and maintaining the development of traditional agricultural activities. This is implemented with two specific instruments. Specific supply arrangements (SSA) that exempt import duties from third countries and allow aid for the supply of Union products, and Support to local production (SLP) that supports the production, processing and marketing of traditional and emerging local agricultural products. In the Azores, SSA focuses on cereals and other by-products for its animal feed industry and livestock sector and SLP focuses on traditional production such as milk and meat (European Commission, 2021[26]). In 2014-20, the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development (EAFRD) allocated EUR 295.3 million and the European Maritime and Fisheries Fund (EMFF) EUR 105 million. Together the two funds are equivalent to 25% of total gross value added in agriculture and fishing (SREA, 2022[12]). The EAFRD mainly supported the competitiveness of farmers with 40% of total budget, whereas climate change and environmental protection counted for 15% of resources each. The EMFF channelled resources for infrastructure and landing sites and for processing and the development of new markets (European Commission, 2019[27]).

Public policies also support innovation and digitalisation in agro-food. The technological park of Nonagon is hosting the local operations of an international platform to develop the circular economy based on the development of fibre-based products from agricultural waste. It is being developed jointly by Fibrenamics, the international platform of the University of Minho, and the Regional Laboratory of Civil Engineering (LREC-Azores). New technologies are opening up unprecedented opportunities for innovation and sophistication of the agro-food value chain. Digital technologies, for example, are improving production, marketing, logistics and retail. Smart farming, the Internet of Things, and Big Data are enabling precision agriculture through advanced monitoring systems that can lead to increased yields, higher productivity, reduced environmental impact and lower impact from natural disasters (OECD/UNCTAD/ECLAC, 2020[28]). The Azores Agricultural Innovation Support Programme (i9agri) aims to enhance farmers' access to new technologies by disbursing financial support (EUR 1 000-20 000) for investments in computerisation and digitalisation, decision-making tools, residue and by-product valorisation, environmental sustainability and precision agriculture, among others.

Local and international partnerships will be key to de-risking and diversifying local fruit and vegetable production, reducing post-harvest waste and increasing quality to reach new high-quality, niche markets. Key options going forward include fostering innovation and exploring options in the circular economy, diversifying production and ensuring the preservation of the local ecosystem (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. Promoting climate-resilient and sustainable agriculture in Brazil: The ABC+ plan 2020-2030

Brazil’s Adaptation, Resilience and Mitigation plan (ABC) aims to foster climate adaptation and reduction of carbon emissions by supporting farmers to adopt agriculture and livestock integrated systems that aim to recover degraded pastures, improve irrigation systems and better manage agro‑food waste through pest and pollinator management practices.

Agricultural production occupies 30% of the total area of Brazil. Environmental conditions greatly influence the sector and climate change is one of the most important risks to sustainable production. In 2012, Brazil committed to increasing and strengthening the sustainability of its agricultural systems and to promote resilient production with the ABC Plan.

The Brazilian government intends to continue its efforts in this direction with the Brazilian Agricultural Policy for Climate Adaptation and Low Carbon Emission - 2020-2030 or ABC+ Plan (MAPA, 2021). The ABC+ Plan is a national policy developed in synergy with regional policies and with the involvement of private stakeholders. The plan fosters the adoption of standardised practices and technologies through technical extension, dedicated financial instruments, and empowerment through the ABC Platform. ABC+ also expands the goals for Brazil in its efforts to combat climate change. For example, during the period 2020-30, Brazil aims to mitigate 1.1 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent, compared to 133‑163 million tonnes during 2010-20.

The ABC Platform, a multi-institutional monitoring and evaluation of the ABC+ Plan, evaluates studies and indicators regarding the resilience of agricultural systems and the adaptive capacity of such systems. The platform has information and planning instruments, such as Sisdagro (a decision-support system for agriculture from the National Meteorological Institute), SCenAgri (simulation of future agricultural scenarios) and the SOMABRASIL (an observation and monitoring system for agriculture in Brazil), both co-ordinated by Embrapa. These systems are increasingly adjusting their methodologies for facing climatic uncertainty in order to improve decision making by farmers and governments.

Source: Mariane Crespolini, “Innovation in Agro Food Value Chains”, Department of Sustainable Production and Irrigation, Secretariat for Innovation, Rural Development and Irrigation, Ministry of Agriculture, Brazil, presentation at the First Peer Learning Group (PLG) Meeting “Innovating in agro-food value chains”, 21 January 2022.

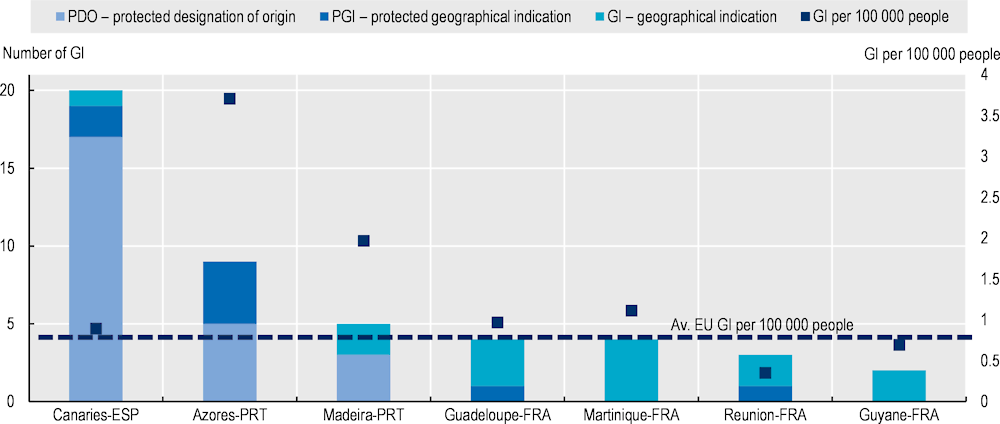

The Azores are prioritising quality and certification to push agro-food exports. In 2015 the local brand Marca Açores was launched, aimed at promoting the identity and cultural value of the Azores, but also to provide a label of origin for food and non-food products, crafts, services and facilities. Moreover, the archipelago has nine products protected under the EU geographical indication schemes. Along with the Canaries and Madeira, the Azores have a higher number of Geographical Indication (GI) products per 100 000 people than the average of the EU, Spain and Portugal (Figure 2.6). Some of the GI products in the Azores include among other volcanic wines, tropical fruits like pineapple and maracuja, and dairy products. The uniqueness of Azorean products could benefit from the overarching branding of Portugal that could further support visibility and positioning in high-end markets. Insisting on prioritising quality and certification will be key to further expand the promotion and traceability of the Azorean products and leverage on high value end market. In this respect new technologies such as blockchain and Distributed Ledger Technologies (DLTs) applications can be set the path for future certification but also induce new business opportunities (Bianchini and Kwon, 2020[29]).

Figure 2.6. The Azores have higher number of geographical indication products per capita than the EU average

Note: Mayotte and Saint Martin do not have registered geographical indications.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on EU geographical indications register eAmbrosia, https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/food-safety-and-quality/certification/quality-labels/geographical-indications-register/.

Access to international markets remains a challenge for the archipelago. Leveraging strategic partnerships with national and international star businesses and retailers could open up new opportunities to explore the returns of high-end markets in strategic locations such as the EU and the United States, and could contribute to reducing the high logistical costs. The Azores and mainland Portugal could also benefit more from leveraging increasingly on the national branding promotion system. At the same time, relying on the untapped potential of the diaspora could support further penetration of Azorean products. The over 1.4 million of Portuguese diaspora in the United States with a median of USD 80 000 household income could not only contribute to local development through potential investment, they also provide a foothold into wider commercialisation channels. In fact, migrant-entrepreneurs act as co-creators of goods, services and intellectual property and often operate as collaborators, investors and distributors in international markets (OECD/UNCTAD/ECLAC, 2020[28]).

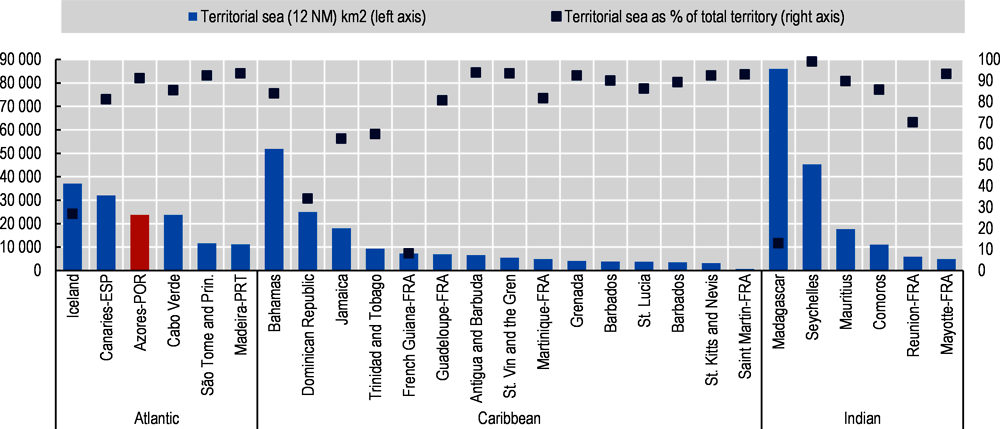

Connecting local and global players for innovative ocean solutions

The internationalisation of the Azores is intertwined with the oceans. Hosting a rich biodiversity and 4 out of Portugal’s 12 UNESCO Biosphere Reserves, the Azores are encapsulated in an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of nearly 1 million km², the second largest of the EU, that supports important activities including fishing, sustainable tourism and scientific research (IUCN, 2020[30]; European Commission, 2021[31]). Similar to other ORs and their neighbouring countries in Atlantic, Caribbean and Indian Oceans the territorial sea accounts for more than 90% of total territory of the Azores (Figure 2.7). From deep-sea research to seamount ecosystems and research activities related to the impact of human activities, the archipelago is a natural open laboratory for understanding the functioning of seas. This vast ecosystem is also subject to different geological and meteorological hazards that can severely undermine the economy and society.

Figure 2.7. The ocean represents 90% of the Azores territory

Note: Territorial sea follows the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) that establishes a legal framework for territorial sea out to 12 nautical miles (22 kilometres; 14 miles) from the baseline.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Flanders Marine Institute (2019), Maritime Boundaries Geodatabase, version 1, https://www.marineregions.org/, https://doi.org/10.14284/382; Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data, and National statistical offices of France, https://www.insee.fr, Spain, https://www.ine.es and Portugal, https://ine.pt/.

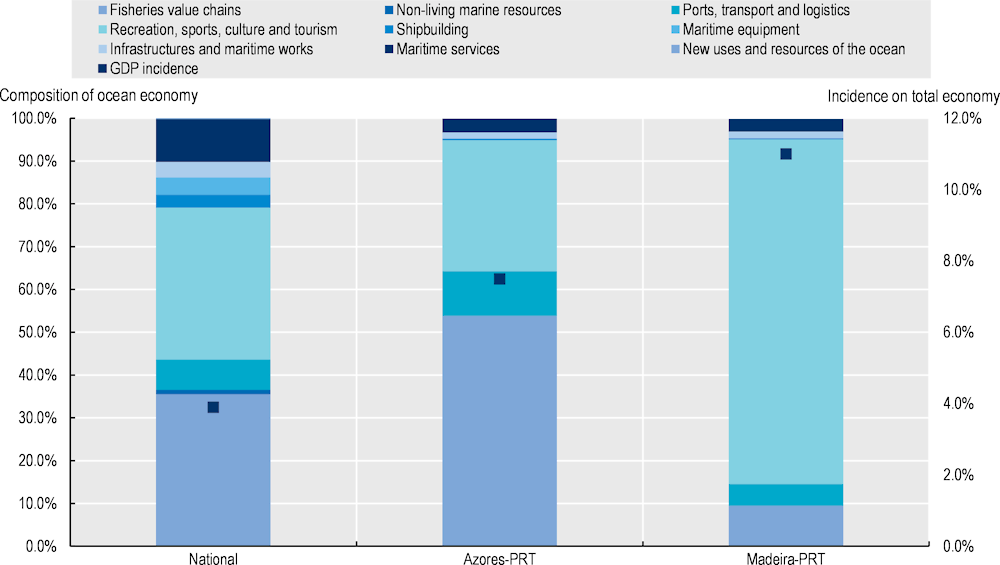

It is vital for the Azores to make the most of the ocean economy. According to the Portuguese Ocean Satellite Account in 2018, the Azores contribute to 4% of Portugal’s ocean gross value added and employment. Moreover, the regional gross value added associated with ocean activities stands at 7.5%, higher than the national aggregate of 4.4% (INE, 2020[32]). The vast majority of these activities, like in other ORs and Madeira, are associated with traditional value chains such as fishing and coastal tourism, which account for 85% of total value added. More sophisticated marine services like ocean R&D, biotechnology, maritime information and communication services and renewable energies account for only 3% (Figure 2.8). The specialisation in relatively low-value added activities that face greater risks of deteriorating marine ecosystems and are more vulnerable to external shocks, resembles the structural heterogeneity configuration of an ocean economy typical of low and middle-income countries, for which the contribution to GDP accounts on average for 11% and 6% respectively (OECD, 2020[33]). On the contrary, for high-income countries, the ocean economy accounts for less than 2% of GDP, with relative specialisation in technology and knowledge-intensive activities with higher returns such as biotechnology and bio-economy. In 2018, for example, the EU-27 ocean economy directly employed almost 4.5 million people (2.3% of the workforce) and generated around USD 200 billion of gross value added (1.5% of GDP) with a greater contribution from more sophisticated value chains (European Commission, 2021[34]).

Figure 2.8. Structural heterogeneity of the Azores’ ocean economy

Note: Figures for Portugal exclude Azores and Madeira.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Portuguese Ocean Satellite Account, https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_destaques&DESTAQUESdest_boui=459804030&DESTAQUESmodo=2.

The regional government aims to go beyond traditional fishing, developing higher value-added activities associated with the oceans. Conceived and designed over the last ten years, the Azores launched the Azores Marine Cluster (Cluster do Mar dos Acores) in 2021. The cluster is part of the overall support on Blue Economy provided by the European Commission to Outermost Regions. In 2017 it encouraged all the ORs to develop strategic approaches to the ocean economy by developing a long-term strategy involving all actors and sectors and including strategic planning and innovative investments (European Commission, 2020[35]). All this in line with the policy framework mentioning Outermost Regions in the May 2021 EC Communication on a new Sustainable approach for the Blue Economy for the EU.

Supported by the financial contribution of the RRF, with a total budget of EUR 32 million, the cluster aims at supporting and developing economic activities associated with the oceans through two main initiatives:

The creation of an ocean experimental research and development centre on the island of Faial (Tecnopolo MARTEC) to host regional, domestic and international institutions involved with scientific and technological innovation associated with the entire ocean value chains including fisheries and aquaculture, marine biotechnology, biomaterials, marine technologies and engineering.

Replacing and modernising the local fishing and shipping fleet with up-to-date technologies, standards and equipment that respond to current needs such as the improvement of marine research and monitoring, and the possibility of improving deep-sea fishing techniques.

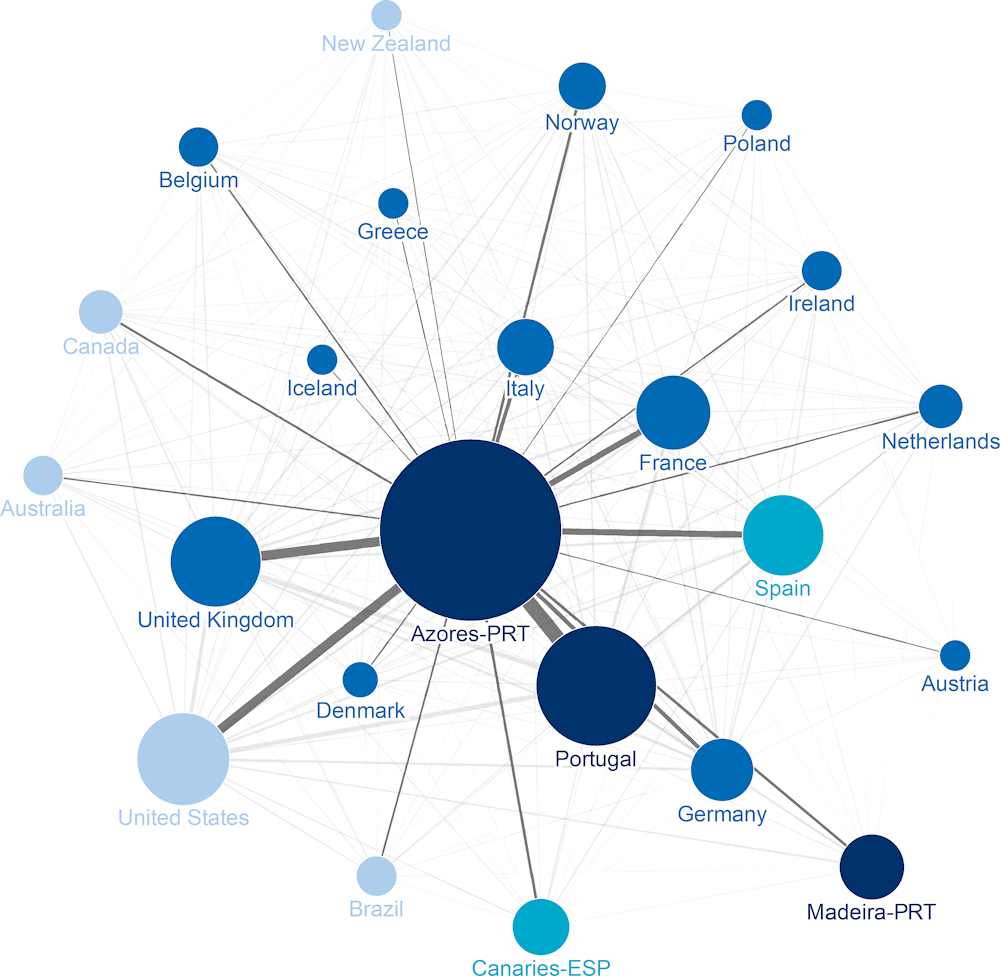

The Azores are becoming an important actor in the ocean scientific community. The Azores, despite the limited human capital resources and the relatively small scale of the involved institutions are already very active in scientific research related to oceans and contributed to 10% of total Portuguese research output in 2000-21 (Figure 2.9). They have an extensive research network involving institutions from the top leading countries. 86% of total research publications in 2000-21 were published with a partner outside of the region. Of these 18% were with mainland Portuguese institutions, 11% with the United States, 10% with the United Kingdom and 8% with Spain. Scientific co-operation within Macaronesia, Madeira and the Canaries, accounts for 8%, showing the importance of cross-border scientific effort within the EU framework programmes. These include the competitive projects allocated under Horizon 2020 with a total allocation of EUR 9 million in 2014-20. Of these, 42% have been allocated to the Institute of Marine Research (IMAR) hosted by the University of Azores. The IMAR, along with 23 other institutions from the 9 ORs, participated in the H2020 FORWARD project that aimed to foster interregional research on eight scientific thematic areas, including marine science and technologies, earth, space and universe sciences. Another relevant example of cross-border co-operation is the Interreg Macaronesia programme with a total budget of EUR 150 million shared among all participants, including emerging and developing economies like Cabo Verde, Senegal and Mauritania.

Figure 2.9. The Azores contribute 10% of Portuguese research on oceans

Note: Ocean related scientific publications include all scientific publications that contain ocean/s, maritime or marine in either the title, abstract or keywords. Only journal publications referenced at least once were included in the final set that covers the years from 2000 to 2021.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Scopus (Elsevier B.V.), https://www.scopus.com/.

The regional government is also prioritising the potential synergies between ocean and space activities. The Azores have been a hub for space activities since the early 2000s. They host the launcher tracking station of the European Space Agency (ESA), the Atmospheric Radiation Measurement (ARM) facility of the US department of Energy and the Galileo station and more recently a 15-meter telecommunications antenna in 2020 and the installation of EUMESTAT in 2021. In addition, in 2019 Portugal launched the Space 2030 strategy that aims to leverage the strategic position of the Azores as a launching platform for small satellites on the island of Santa Maria. The programme aims to stimulate the space sector in Portugal, creating conditions for the development of national capacity and expertise in the field of space industry within the framework of the Copernicus programme. By means of satellites, observations include detailed information that can serve end users for a wide range of applications, including assessment of protected marine areas, precision agriculture and climate change. The private sector is an important player in this area. Since 2016 the Atlantic International Research Centre (AIR Centre), an international collaborative organisation that promotes an integrative approach to space, climate, ocean and energy in the Atlantic has its headquarters in the Azores, with an executive committee that include representatives from Portugal, Spain, Brazil and South Africa.

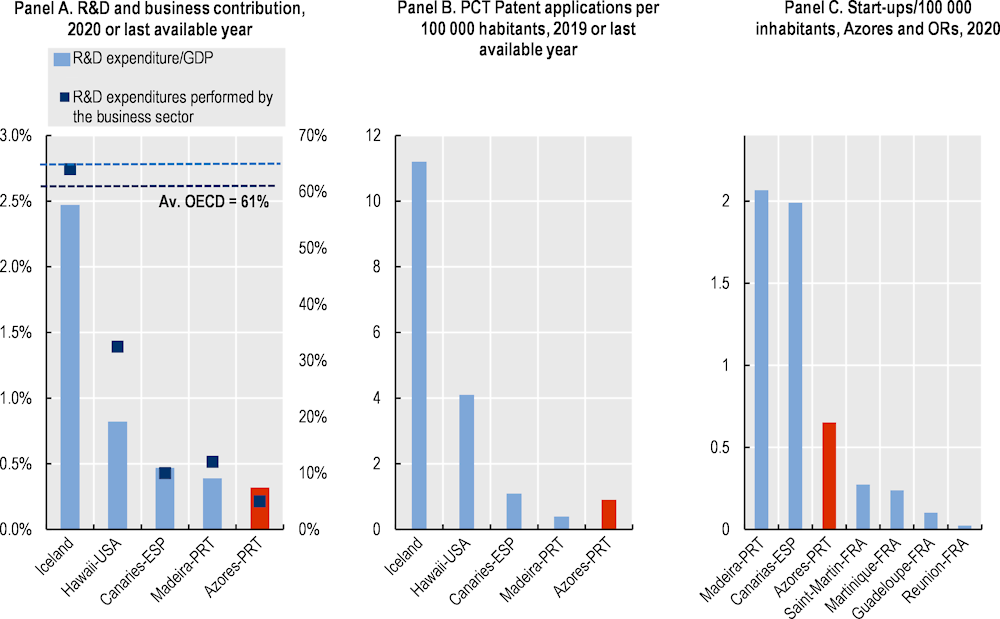

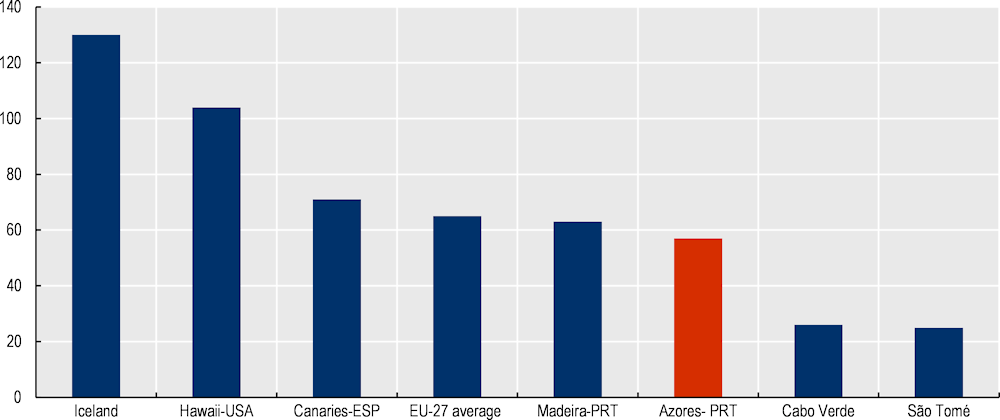

Despite such efforts and these positive trends, the innovation ecosystem in the Azores is still at an early stage and private-sector commitment remains limited. The region would benefit from higher levels of investment in research and innovation. R&D investment is 0.3% of GDP, well below the national average (1.6%) and OECD average (2.7%) and similar to developing and emerging economies in Latin America. The private sector contributes only 15% of total regional R&D investment, whereas in islands that have built up Ocean Clusters models, the private sector accounts for a higher proportion of R&D expenditures (64% in Iceland and 32% in Hawaii and the United States) (Figure 2.10). More investment in research and innovation can have important implications in supporting the creation of new entrepreneurial activities. Start-ups have the potential to create new products and services that can increase the diversification and value added of local ocean-related activities and allow for new entrepreneurial discoveries. In this respect the renewed EU Atlantic Action plan 2.0 provides a space for the Azores to strengthen these areas together with other EU countries and regions from Ireland, Spain, France and Portugal (Box 2.2). Also, the Horizon Europe offers additional opportunities to support their research and innovation capacity in this area.

Box 2.2. The EU Atlantic action plan 2.0: Towards a resilient and competitive blue economy

An updated action plan for a sustainable, resilient and competitive blue economy in the European Union Atlantic area

The original EU Atlantic maritime strategy was adopted in 2011 by the European Commission to support the sustainable development of the blue economy in the EU Member States bordering the Atlantic. In 2013, the European Commission put forward an Atlantic action plan to implement the strategy. In July 2020, the European Commission adopted a revised Atlantic Action Plan 2.0, further to a mid-term review of the Atlantic action plan published in 2018 by the European Commission to give a new boost to a sustainable maritime economy and as a contribution to Europe’s recovery from the crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The AAP 2.0 sets out four thematic priorities for regional co-operation, following a bottom-up stakeholders’ consultation. Its purpose is to unlock the potential of sustainable blue economy in the Atlantic area while preserving marine ecosystems and contributing to climate change adaptation and mitigation. This is in line with the global commitments for sustainable development and fully integrated in the European Commission’s political priorities for 2019-24, notably a European Green Deal, an Economy that works for people and a stronger Europe in the world.

Pillar i: ports as gateways and hubs for the blue economy

Pillar ii: blue skills of the future and ocean literacy

Pillar iii: marine renewable energy

Pillar iv: healthy ocean and resilient coasts

The Action Plan 2.0 strengthens regional maritime co-operation among the participating countries, including coastal regions and stakeholders from France, Ireland, Portugal and Spain. It is implemented through the Atlantic Assistance Mechanism which supports the three existing sea basin strategies.

Although no funding has been earmarked in the EU budget for the Atlantic action plan, it relies on the existing EU, national and regional funds and financing instruments relevant to the goals and actions that can be mobilised.

Source: COM/2020/329 final “A new approach to the Atlantic maritime strategy – Atlantic action plan 2.0 An updated action plan for a sustainable, resilient and competitive blue economy in the European Union Atlantic area”, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2020:329:FIN.

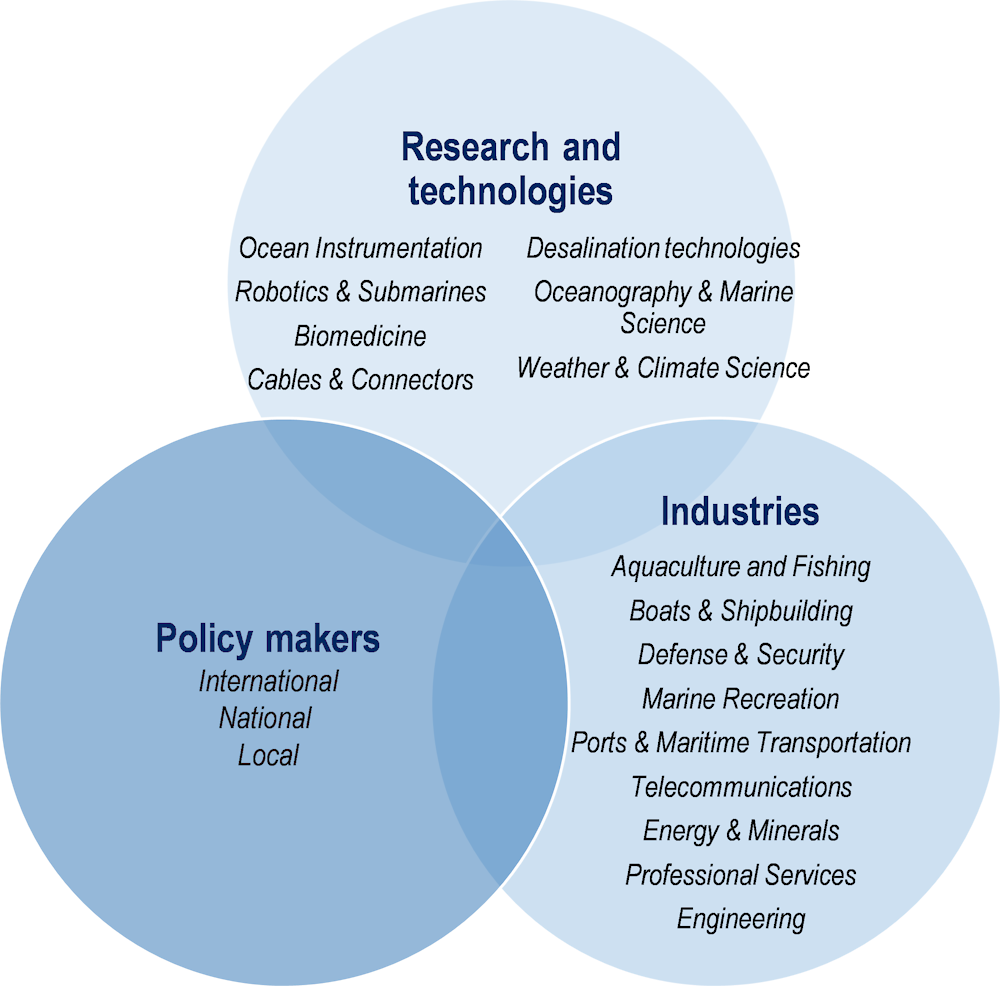

If managed strategically, the ocean economy can support the internationalisation of the Azores and its participation in global networks beyond the EU, focusing more on innovation, and fostering the development of global connections in science, research and exploration. To do so, the region needs to better seize the available resources, increase development of innovation activities and foster the development of global partnerships for the ocean economy. Due to their global nature, ocean innovation activities are often the result of networks in which public and private institutions interact and facilitate knowledge dissemination and flows by sharing financial resources, technologies and infrastructure facilities. There is no one-size-fits-all for structuring and organising an ocean cluster, but some models have proved to be highly effective, especially in leveraging local solutions through international partnerships. Worth mentioning among them are the public consortia, the Canaries’ PLOCAN and the business-led clusters of TMA Bluetech in San Diego (United States) and the Iceland Ocean Cluster that focuses on 100% use of fish biomass (Box 2.3). Other potential partners in this area can be the US states of Hawaii and Rhode Island that, beside hosting Azorean descendants, have developed ocean strategies and clusters (U.S. Economic Development Administratio, 2022[36]).

Figure 2.10. The Azores invest seven times less on R&D than Iceland

Note: Panel A. for Azores, Madeira, Canaries and Hawaii most recent data refer to 2019. Panel B. for Azores, Madeira, Canaries and Hawaii most recent data refer to 2015.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD Main Science and Technology Indicators, https://doi.org/10.1787/data-00182-en, 2022 and Crunchbase data 2022, https://www.crunchbase.com/.

Box 2.3. Ocean clusters: Lessons from Iceland and the United States

Iceland

Iceland, the second largest producer of seafood in Europe after Norway, has been transforming its fishing industry through the emergence of a vibrant start-up culture with strong connections to local marine-related businesses, academia and the public sector. Icelandic start-ups have developed new innovations based on fishing products that aim to add more value and minimise catch waste, such as Kerecis, a start-up developed in 2013 that develops skin grafts from fish skins. Connecting stakeholders to identify and exploit new market opportunities, and plugging the financing gap through mobilising private and public sector investments has been central to Iceland’s experience. The Iceland Ocean Cluster, for example, was established in 2011 as a privately held cluster with the aim to connect entrepreneurs and knowledge partners in ocean-related economic activities. It operates largely as an accelerator and provides networking and other services to businesses, while it also invests resources in new projects. The Cluster has fostered more than 120 start-ups since its establishment.

United States

Headquartered in San Diego, United States, TMA BlueTech is a non-profit industry association and cluster organiser founded in 2011 that promotes cross collaboration between academia, industry and policy makers to scale up scientific research on ocean-related activities and develop new business solutions. TMA supported the creation and expansion of ten clusters in eight different countries including France, Portugal and Spain. Through knowledge sharing, national and international outreach and networking, the members of clusters share best practices and explore new ways to collaborate with the objective of developing new business opportunities. Clusters include members from 16 sectors that provide ocean-based solutions in the following areas:

Water shortage such as exploration and conservation including submarine groundwater springs

Agro-food including underwater greenhouses that require limited energy and provide options for algae-based fertilisers

Pollution including the reuse of non-recyclable ocean plastic and transformation through pyrolysis into low-emission fuel and other products.

Figure 2.11. TMA Blue Tech cluster organisation

Source: Thor Sigfusson, Founder, Iceland Ocean Cluster, Iceland and Michael Jones (2022), President, TMA BlueTech, San Diego California, United States. Presentations at the Second Peer Learning Group (PLG) Meeting “Innovating Oceans”, 3 March 2022.

Accelerating the green energy transition through partnerships and knowledge sharing

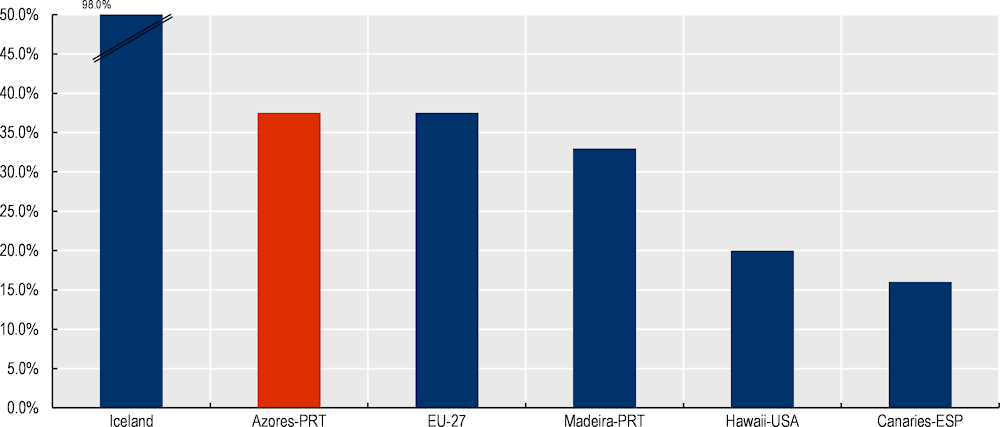

The Azores generate around 40% of their electricity from renewable energies. Over the last 20 years, the contribution of renewable energies in total electricity production rose from 19% in 2000 to 37% in 2021. This has brought the region above other EU ORs and in line with the EU-27 average but below the national average of 54% (Figure 2.12). Geothermal energy, given the volcanic characteristics of the archipelago, is the leading source of renewable energy, accounting for 55% of the total. Three geothermal plants operate, producing a total energy output of 34.4 MW per year. In 2019 two plants on the island of São Miguel contributed up to 40% of the island’s total electricity and one in Terceira generated around 12.5% of the island’s total energy requirements. Wind power is the second largest renewable source, accounting for 27% of total renewables. The Azores first experimented with wind energy in 1988 with the installation of wind turbines on the island of Santa Maria. Currently there are nine wind turbine parks spread across eight of the islands. Twelve hydroelectric plants account for 12% of total renewables (Melo et al., 2020[37]; Direcao Geral de Enrgia e Geologia, 2022[11]).

Figure 2.12. The share of renewables in electricity production in the Azores is on par with the EU average

Note: Azores 2021; EU-27, Iceland, Madeira 2020; Canaries and Hawaii 2019.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on data from IRENA, https://www.irena.org/; Portuguese Renewable Energy Association (APREN), https://www.apren.pt/; National Communications Authority ANACOM, https://www.anacom.pt/; Canaries Department of Ecological Transition, https://www.gobiernodecanarias.org/energia; Hawaii Department of Energy, https://energy.hawaii.gov/.

The path towards a sustainable energy transition requires further efforts. Despite the advancement in total RE capacity, the Azores, similarly to many small islands, largely depend on imported fossil fuels to sustain energy consumption. In 2019, around 90% of total energy supply relied on imported fuels. The most energy-intensive activities are land transport that accounts for 30% of total energy consumption, followed by electricity production and air transport with 29% and 16.5% respectively. Residential activities and services account for less than 10% each. Major challenges to the energy transition relate to the archipelagic nature of the Azores and include the presence of nine small, separate grids, the limited battery storage capacity for electricity originating from RE, and the small market size which makes the Azores less profitable for private investments.

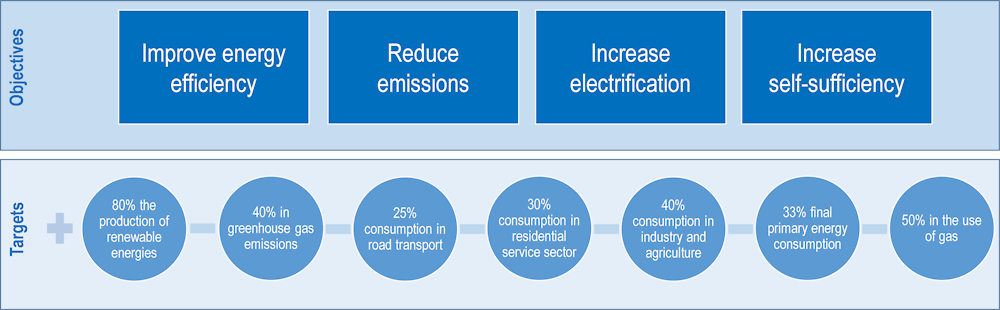

The Azores have an ambitious energy transition strategy. In 2018, the regional government launched a participatory process to define the Regional Energy Strategy 2030 (Estratégia Açoriana para a Energia 2030 EAE2030). The strategy is structured around four objectives and seven targets, and it encompasses an increase of energy self-sufficiency, a reduction in the number of energy vectors though increased electrification, an improvement in energy efficiency by increasing the storage capacity of batteries and a shift towards reduced greenhouse emissions (Figure 2.13). The government also offers incentive packages to support the deployment and use of green energy sources. These include, for example, incentives for electric vehicles of up to EUR 4 500 and for the installation of micro power renewable energy plants of up to EUR 20 000.

The Azores also participate in several cross-European initiatives that aim at fostering the transition away from fossil fuels and towards cleaner energy. The Azores participate in the Clean Energy for EU islands, a country- and island-led initiative that advocates and supports the EU islands in their energy transition agendas by promoting the exchange of best practices, guidance on the development of regional strategies and assistance in project preparation. Other initiatives include:

IANOS (Integrated Solutions for Decarbonisation and Smartification of Islands), with a budget of EUR 8.8 million, channelled through H2020, focuses on maximising the opportunities for self-sufficiency through the use of distributed renewable energy and storage technologies. The consortium consists of 35 partners from 10 European countries: Portugal, Finland, United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Italy, France, French Polynesia, Greece, Spain and Belgium.

RESOR (Supporting energy efficiency and renewable energy in European islands and remote regions) and EMOBICITY (Increase of energy efficiency by electric mobility in cities), with a budget of EUR 1.5 million and EUR 1.0 million each, channelled via the Interreg Programmes. RESOR aims to improve the regional support measures for energy efficiency and renewables in tertiary sectors. EMOBICITY aims to improve regional support measures for electric mobility in urban areas.

LIFE IP CLIMAZ, with a budget of EUR 20 million, through the EU LIFE Programme, supports the Azores in accomplishing the climate change objectives through an integrated approach that also includes energy transition.

Figure 2.13. The Azores Regional Energy Strategy for 2030

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Direção Regional da Energia - Governo Regional dos Açores (2020), Estratégia Açoriana para a Energia 2030, https://portaldaenergia.azores.gov.pt.

Accelerating a green transition is paramount for the Azores. The multi-annual planning and financing of the EU provides a unique opportunity to advance in this respect. The effort should involve all economic activities including transportation and industry and will improve the image and attractiveness of the Azores as a sustainable tourism destination (OECD, 2022[9]). The electrification of the energy matrix seems to be the most promising area for further development, due to several factors including the availability of stable, predictable geothermal energy and of untapped renewable energy sources. The region would benefit from further exploiting geothermal potential, complementing it with other RE, including wind, photovoltaic and solar thermal energy but also marine renewables such as wave power, which currently only contributes to 0.3% of electricity production. The increasingly competitive costs in RE generation, matched with battery storage and new energy smart management software, open up new opportunities for the region. However, this would also require an update in the overall policy and the need to address potential trade-offs with current compensation mechanisms, such as the incentives currently in place for fossil fuels. In the Azores, for example, tax on fuel is 10% lower than the national rate on fuel, 18% for diesel (Fundo Regional de Apoio à Coesão e ao Desenvolvimento Económico, 2022[38]).

International partnerships are key to achieving a full green transition. Given the small size, insufficient human resources and remoteness from other EU regions and countries, the Azores need to scale up effective international partnerships in order to leverage untapped potential, including in areas linked to technology transfer and knowledge sharing. The Azores provide a natural environment for experimentation in innovative renewable solutions like wave energy (Box 2.4). Expertise in developing small integrated energy systems can also be shared with other islands. Consolidating efforts in this area by learning and sharing good practices with EU regions and other partners could provide new internationalisation opportunities that could also lead to new commercial and business relationships. For example, in Northern Ireland, MJM Renewables, Geothermal Engineering Ltd, ARUP and Queen’s University Belfast created in 2021 a consortium Geothermal NI to explore the development of the country’s first deep geothermal project. The consortia will be exploring viable sites with the ultimate goal of developing a project which delivers continuous renewable heat and power to large commercial and industrial end users as well as local homes (Geothermal NI, 2021[39]).

Box 2.4. The Azores are experimenting in innovative renewable energy solutions with international partners

The Azores provide a natural environment for experimenting with a shift to renewable energies. In the late 90s, with the support of EU funds, a pilot wave power plant was installed on the island of Pico by a joint international consortium from Portugal, the United Kingdom and Ireland. Designed to be both an R&D facility for testing and demonstration and an additional source of electricity over time, the plant was damaged several times, leading to its closure in 2018 (Falcão et al., 2020[40]). The Pico plant engaged in wave energy research, development and innovation, with national and international partners. It attracted funding from more than 11 national and European projects including two European networks of test infrastructure for wave energy technologies (Marinet and Marinet 2). It led to more than 100 international scientific articles and was associated with more than eight doctoral theses.

More recently two projects have been developed: Siemens Smart Infrastructure, in partnership with Fluence, which has been contracted by EDA to build the energy storage system on Terceira. With a power capacity of 15 MW, the system will be one of the largest stand-alone (island) battery-based energy storage systems in Europe, increasing the share of renewable energy while limiting the consumption of fossil fuels and significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time, Finland’s Wartsila in 2020 launched a hybrid renewable power plant, 1 MW of solar and 4.5 MW of wind along with a 6 MW energy storage system that aims to boost renewable energy consumption from 15% to 65% on the island of Graciosa. Supporting and scaling up these types of initiatives with the involvement of local firms and research centres will be crucial for supporting the development of local scientific and industrial capabilities.

Conclusions and way forward

Connecting globally is key for the Azores. The region needs the world, and the world needs to tap into global talents and entrepreneurs to provide innovative solutions for fairer, more inclusive and environmentally sustainable production, consumption and trade. In the current challenging global context, the Azores could regain its international role, but on new grounds. The region could better leverage its uniqueness and could mobilise new partnerships to innovate in the area of environmental sustainability. In addition to traditional national and EU partners the Azores can strengthen partnerships following cultural and historical binds, such as Brazil and the United States, but also frontrunner countries and regions that share comparable challenges and opportunities, such as Iceland and Hawaii in the Pacific Ocean. It could also develop capacities to reach international niche and high-end markets in agro-food, strengthen global ties to unlock the potential of the ocean and space economy, and reinforce co-operation and knowledge sharing with islands and other remote, environmentally vulnerable locations.

In this context, the policy approach towards increased internationalisation would benefit from an update. A mind-set shift in the policy approach will be paramount. In addition to the necessary special provisions in EU law, tailored support and compensation schemes linked to remoteness, environmental vulnerabilities and biodiversity preservation, it is important to engender a systemic shift that identifies mechanisms that focus on and promote local entrepreneurial development and innovation. A regional development strategy centred on entrepreneurship discovery is key to achieve sustainability and increase economic resilience. If properly conceived and channelled, new partnerships can contribute to the emergence of new capabilities to compete in higher value-added segments of value chains (Figure 2.14). The Nexus Agenda, led by the Port of Sines that can provide good lessons learned in this respect (Box 2.5).

Figure 2.14. Summary of priorities and actions for enhanced internationalisation and GVC participation

The effective internationalisation of the Azores requires a committed private sector and improved digital connectivity. The rapid diffusion of digital technologies in production and processes has increased the need for access to fast and stable internet connections. The average broadband speed in the Azores is 57 Mb/s, below the EU average and as much as two times slower than partner countries like Iceland (Figure 2.15). The deployment of digital infrastructure including submarine cables will also be paramount in the future. Likewise, it would be important to develop public and private partnerships to advance in the development of ports and infrastructure (Box 2.5).

Figure 2.15. Broadband speed in the Azores is below the EU average

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on broadband speedchecker data, https://www.broadbandspeedchecker.co.uk/.

Box 2.5. Leveraging ports and logistics networks as an asset for regional development

Infrastructure connections are key to support the internationalisation of countries and regions. Limited access to logistics networks may hamper opportunities for trade, as well as attraction of FDI, talent and visitors, particularly for remote regions.

The current shipping model, based on the presumption that more, bigger and cheaper is better, has reached its limits. The post-pandemic period has highlighted that congestion in only a few hub ports can result in severe disruption of global supply chains. Recent developments at the global level show that:

The organisation of ports should be developed as complementary to other infrastructure, transport and logistics policies.

Delivering better environmental performance would help rebalance the current race for critical mass and be more aligned to regional development objectives. This renewed approach could also allow new regions and territories, including those with mid-sized ports, to become more attractive to global trade.

Shifting to such a model will present multi-level governance challenges, and require quality partnerships between stakeholders (e.g. national and regional governments, cities and the private sector, and ports).

For example, the Nexus Agenda, led by the Ports of Sines and the Algarve Authority in Portugal, is a consortium of 35 national and international representatives from the transport and logistics sector, academia, research institutions, and technology companies, that develops solutions for the digital and ecological transition of the transport and logistics sector in the Algarve. It is estimated that by 2030, products created under the Agenda will generate a thousand jobs and reduce the carbon footprint of the Port of Sines by 55%.

Source: OECD (forthcoming[41]), Rethinking regional attractiveness in the new global environment; OECD (2022[8]), L’internationalisation et l’attractivité des régions françaises, (The internationalisation and attractiveness strategies of French regions), https://doi.org/10.1787/6f04564a-fr.

The proactive participation of the private sector with an innovation mind-set and stronger partnership with the local institutions will be essential to make the most of the EU resources to unlock international partnerships, develop new businesses and innovate in traditional activities. The region can leverage the technology parks of Nonagon and Terinov, which could act as partnership and innovation catalysts. Through Terinov, for example, the region could exploit the potential of satellite imaging applied to agriculture precision and monitoring. In this respect, public policies would also need to address issues linked to awareness-raising on the region’s potential as a science and technology actor.

Internationalisation also goes beyond participation in global value chains using the traditional market-oriented approach. Concretely, two other areas should be considered as potential drivers of enhanced international ties. First, since research, development and innovation will be central pillars in the future development of the region, strengthening and improving research and innovative networks with both EU and overseas partners in the Atlantic and beyond will be crucial, including the United States, Iceland and Brazil. Due to their specificities, such as the presence of an established diaspora, the natural characteristics and cultural ties, these represent potential partners for the future. Second, the Azores could be an important actor in international co-operation. The improved local governance and administrative capacities thanks to the different projects and planning processes implemented with the support of national and EU institutions, particularly in the areas of environmental risk management, agro-food and ocean activities, could be shared with other development actors. The Azores already has an active international collaboration strategy, for example within the Interreg MAC project, as well as bilateral co-operation with countries such as São Tomé and Cabo Verde. Scaling-up these efforts and expanding them to countries facing comparable challenges, such as SIDS, will be essential for a more comprehensive and effective implementation of the decentralised Portuguese and European Union development and co-operation strategies (OECD, 2022[42]). Concretely the Azores could be involved in triangular technical co-operation involving national authorities like Camões and multiple European Commission Directorates-General such as the Directorate General for International Partnerships. Instruments such as the European Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) with West Africa, which includes a strong development and co-operation pillar, could build synergies with already established instruments of co-operation such as the Interreg MAC that includes the three ORs in the Atlantic as well as the Interreg of the Atlantic Area.

The Azores have advanced considerably in recent decades. The region should continue to leverage its uniqueness, putting sustainability at the core of development strategy and increasingly developing local entrepreneurial and research capacities. The EU multi-annual planning and financing processes are a major asset that should be further exploited, enabling the region to fulfil its potential as a laboratory for innovative solutions to global challenges, turning remoteness into an advantage by developing international partnerships grounded on research, entrepreneurship and innovation.

References

[21] Alatalo, J., A. Jägerbrand and U. Molau (2014), “Climate change and climatic events: community-, functional- and species-level responses of bryophytes and lichens to constant, stepwise, and pulse experimental warming in an alpine tundra”, Alpine Botany, Vol. 124/2, pp. 81-91, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00035-014-0133-z.

[20] Autoridade Tributária Aduaneira (2021), “Guia sobre o tratamento das operações de importação e exportação em sede de iva”, https://info.portaldasfinancas.gov.pt/pt/informacao_fiscal/legislacao/instrucoes_adminis- (accessed on 16 January 2022).

[5] Azores Government (2021), Recovery and Resilience Plan - Regional Directorate for Planning and Structural Funds, https://portal.azores.gov.pt/en/web/drpfe/prr (accessed on 6 May 2022).

[29] Bianchini, M. and I. Kwon (2020), “Blockchain for SMEs and entrepreneurs in Italy”, OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Papers, No. 20, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/f241e9cc-en.

[18] de Almeida, A., P. Alvarenga and D. Fangueiro (2021), “The dairy sector in the Azores Islands: possibilities and main constraints towards increased added value”, Tropical Animal Health and Production, Vol. 53/1, pp. 1-9, https://doi.org/10.1007/S11250-020-02442-Z/TABLES/1.

[2] Dentinho, T. and M. Fortuna (2019), “How regional governance constrains regional development. Evidences from an econometric base model for the Azores”, Revista Portuguesa de Estudos Regionais, Vol. 52, pp. 25-55, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Tomaz-Dentinho/publication/335843547_How_Regional_Governance_Constrains_Regional_Develop-_ment_Evidences_From_an_Econometric_Base_Model_For_the_Azores/links/5d802049a6fdcc66b001ac73/How-Regional-Governance-Constrains-Regional-Develop-ment-Evidences-From-an-Econometric-Base-Model-For-the-Azores.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2022).

[11] Direcao Geral de Enrgia e Geologia (2022), Balanços Energéticos da Região Autónoma dos Açores, https://www.dgeg.gov.pt/pt/estatistica/energia/balancos-energeticos/balancos-energeticos-da-regiao-autonoma-dos-acores/ (accessed on 2 May 2022).

[19] Earth Observatory System (2020), Monoculture Farming Explained: What Are The Pros And Cons?, https://eos.com/blog/monoculture-farming/ (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[26] European Commission (2021), Implementation of the scheme of specific measures for agriculture in favour of the outermost regions of the Union (POSEI), https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0765 (accessed on 20 November 2022).

[31] European Commission (2021), New approach for a sustainable blue economy in the EU Transforming the EU’s Blue Economy for a Sustainable Future, EUR-Lex - 52021DC0240 - EN - EUR-Lex, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2021:240:FIN (accessed on 22 February 2022).

[4] European Commission (2021), Recovery and Resilience Facility, https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/recovery-coronavirus/recovery-and-resilience-facility_it (accessed on 6 May 2022).

[34] European Commission (2021), The EU blue economy report 2021, Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, Publications Office, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/0b0c5bfd-c737-11eb-a925-01aa75ed71a1/language-en (accessed on 16 February 2022).

[35] European Commission (2020), Methodological assistance for the outermost regions to support their efforts to develop blue economy strategies, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2771/489282 (accessed on 18 February 2022).

[27] European Commission (2019), Implementation of the EMFF in outermost regions : final report, Publications Office, https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2771/51221 (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[22] European Commission (2017), Realising the potential of the Outermost Regions for sustainable blue growth, https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/information/publications/reports/2017/realising-the-potential-of-the-outermost-regions-for-sustainable-blue-growth (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[7] European Institute of Public Administration (EIPA) (2022), Recovery plans and structural funds: how to strengthen the link?, https://www.eipa.eu/publications/briefing/recovery-plans-and-structural-funds-how-to-strengthen-the-link/#_ftn4 (accessed on 5 May 2022).

[40] Falcão, A. et al. (2020), “The Pico OWC wave power plant: Its lifetime from conception to closure 1986–2018”, Applied Ocean Research, Vol. 98, p. 102104, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apor.2020.102104.

[13] FAO (2022), Ukraine: Note on the impact of the war on food security in Ukraine, Food and Agriculture Organization, https://doi.org/10.4060/cb9171en.

[14] FAO (2021), Scientific review of the impact of climate change on plant pests – A global challenge to prevent and mitigate plant pest risks in agriculture, forestry and ecosystems, Food and Agriculture Organization on behalf of the IPPC Secretariat, Rome.

[23] Fauconnet, L. et al. (2019), “An overview of fisheries discards in the Azores”, Fisheries Research, Vol. 209, pp. 230-241, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FISHRES.2018.10.001.

[38] Fundo Regional de Apoio à Coesão e ao Desenvolvimento Económico (2022), Preço Combustíveis 2022, https://portal.azores.gov.pt/web/fracde/pre%C3%A7o-combust%C3%ADveis (accessed on 4 May 2022).

[39] Geothermal NI (2021), Deep Geothermal Renewable Energy, https://www.geothermalni.com/ (accessed on 17 March 2023).

[32] INE (2020), Ocean economy more dynamic than the national economy in the 2016-2018 triennium, https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE&xpgid=ine_destaques&DESTAQUESdest_boui=459803212&DESTAQUEStema=55505&DESTAQUESmodo=2&xlang=en (accessed on 21 February 2022).

[30] IUCN (2020), IUCN 2019 : International Union for Conservation of Nature annual report 2019 | IUCN Library System, https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/49096 (accessed on 21 February 2022).

[37] Melo, I. et al. (2020), “Sustainability economic study of the islands of the Azores archipelago using photovoltaic panels, wind energy and storage system”, Renewables: Wind, Water, and Solar, Vol. 7/1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40807-020-00061-8.

[3] Ministerio do Planeamento (2021), “Recuperar Portugal, Construindo o futuro Mecanismo de Recuperação e Resiliência”, https://recuperarportugal.gov.pt/ (accessed on 6 May 2022).

[8] OECD (2022), L’internationalisation et l’attractivité des régions françaises, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/6f04564a-fr.

[9] OECD (2022), “Measuring the attractiveness of regions”, OECD Regional Development Papers, No. 36, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fbe44086-en.

[42] OECD (2022), OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews: Portugal 2022, OECD Development Co-operation Peer Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/550fb40e-en.

[10] OECD (2022), OECD Tourism Trends and Policies 2022, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a8dd3019-en.

[16] OECD (2021), Making Better Policies for Food Systems, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ddfba4de-en.

[6] OECD (2020), Rural Well-being: Geography of Opportunities, OECD Rural Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d25cef80-en.

[33] OECD (2020), Sustainable Ocean for All: Harnessing the Benefits of Sustainable Ocean Economies for Developing Countries, The Development Dimension, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/bede6513-en.

[41] OECD (forthcoming), Rethinking regional attractiveness in the new global environment, OECD Publishing, Paris.

[15] OECD/FAO (2021), OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2021-2030, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/19428846-en.

[28] OECD/UNCTAD/ECLAC (2020), Production Transformation Policy Review of the Dominican Republic: Preserving Growth, Achieving Resilience, OECD Development Pathways, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1201cfea-en.

[24] ORFISH (2016), Development of innovative, low-impact offshore fishing practices for small-scale vessels in outermost regions - MARE/2015/06, https://drive.google.com/file/d/152CJcIeZqb79zZ4rPQkoWYM136p0CPqe/view (accessed on 14 April 2022).

[25] Polido, A., E. João and T. Ramos (2016), “Strategic Environmental Assessment practices in European small islands: Insights from Azores and Orkney islands”, Environmental Impact Assessment Review, Vol. 57, pp. 18-30, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.EIAR.2015.11.003.

[1] Região Autónoma dos Açores (2021), Orçamento da Região Autónoma dos Açores para o ano de 2021, https://files.dre.pt/1s/2021/05/10501/0000200075.pdf (accessed on 8 April 2022).