This chapter outlines the Japanese labour market context and its implications for labour migration to Japan. Japan’s population has aged rapidly which has led to a sharp decrease of the working age population. So far, this decrease has been counter-balanced by an increase in labour force participation of women and older workers. The labour market is tight, and, in international comparison, labour shortages appear to be particularly severe. Increasing productivity is the cornerstone of Japan’s policy to address the impact of population ageing on the labour market. Labour migration is also increasingly considered as part of the solution to address labour shortages. The Japanese employment system has unique features that need to be factored in when considering how foreign workers can contribute to the host country labour market.

Recruiting Immigrant Workers: Japan 2024

2. Context for labour migration

Abstract

The Japanese economy is close to full employment and labour shortages are widespread

The population is ageing rapidly

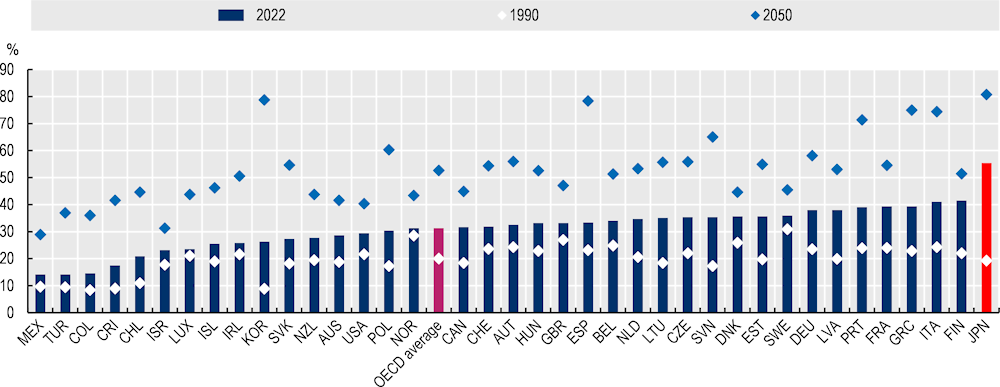

In the last 30 years, Japan has aged rapidly. As a result, Japan’s dependency ratio is now the highest in the OECD, far exceeding that of any other OECD country. In 2022, there were 55 individuals aged 65 and over per every 100 individuals aged 20 to 64, and this ratio is projected to increase to 81 by 2050 (Figure 2.1).1

In the next decades, most OECD countries will face the challenges of an ageing population that Japan is already facing today. By 2050, Korea and several European countries are expected to catch up with Japan.

Figure 2.1. Old-age dependency ratio, 1990‑2050

Note: The old-age dependency ratio is defined as the number of people aged 65 and over per 100 people of working-age (20‑64). 2050 estimates based on the medium-variant projection.

Source: OECD Old-age dependency ratio, https://data.oecd.org/pop/old-age-dependency-ratio.htm.

Increased participation has counteracted, so far, the decline in the working age population

The working age population (ages between 15 and 64) decreased by 9 million individuals, from 83 to 74 million, or 11%, in the past 15 years (2007 to 2022). However, the total labour force has remained relatively stable in the same years, increasing by 3%, or 2 million individuals. The decrease in the working age population was compensated by the increase in participation of women and older workers.

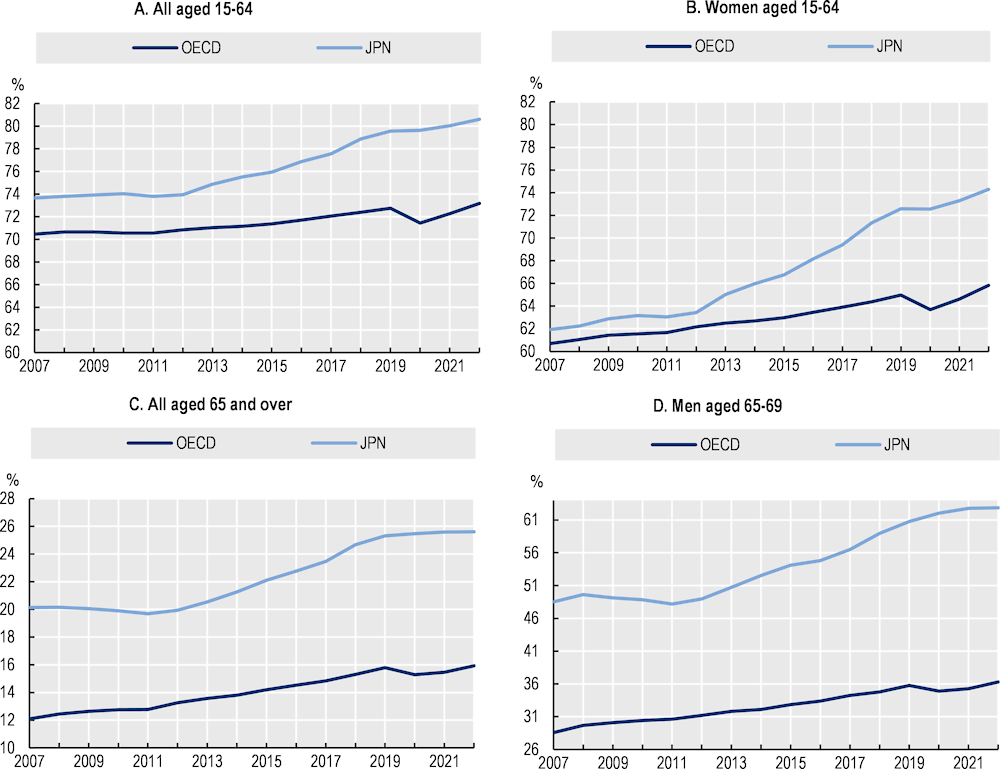

The labour force participation rate of individuals aged 15 to 64 is high in Japan and has increased significantly in the past 15 years, reaching 80.6% in 2022, compared with 73.2% in the OECD (Figure 2.2). This increase was driven by the increase in the labour force participation of women. Between 2007 and 2022, the participation rate of women increased by 12.4 percentage points in Japan (from 61.9% to 74.3%), compared with 5.1 percentage points in the OECD (from 60.7% to 65.8%). The number of women in the labour force increased by slightly over 1 million in these years, partly compensating the decrease in the number of active men aged 15‑64, estimated at 3 million.

Furthermore, the participation of workers, aged 65 and over has also increased, from 20.1% in 2007 to 25.6% in 2022 The participation of older workers is substantially higher in Japan than in the OECD. In 2022, only 15.9% of workers aged over 65 were active across the OECD.2 The increased participation rate of this age group added almost 4 million workers to the labour force in the past 15 years. This large effect is due not only to increased participation but also to the increase in the size of the population aged 65 and over (+ 33% in the same years).

Figure 2.2. Labour force participation rates in Japan and the OECD, 2007‑22

Source: OECD Labour Market Statistics.

The increase in the labour force translated into an increase of the employed population. The employed population increased by 9% in the past 15 years. However, the number of hours worked has not. The share of part-time employment has increased from 18.9% to 25.6% from 2007 to 2022, mainly driven by new female part-time employment. The estimated total annual hours actually worked decreased by 6% from 2007 to 2022 (or 3.5% from 2007 to 2019) (OECD Labour Force Statistics).

Despite the high participation rate, there could hence be a possibility to increase labour supply, if part-time jobs were to be converted to full-time employment. However, most part-time employment is voluntary (82.2% in 2022). Full-time employment for married women remains challenging in Japan. Most married women in employment are “non-regular” workers (see section on the Japanese employment system below) who work part-time. There are important tax disincentives for secondary earners in Japan which partly explains why married women work part-time and earn low wages (OECD, 2024[1]). Japan’s gender wage gap is the fourth largest in the OECD (OECD Labour Force Statistics). The margin to increase hours worked seems small in the current context.

Labour shortages are widespread

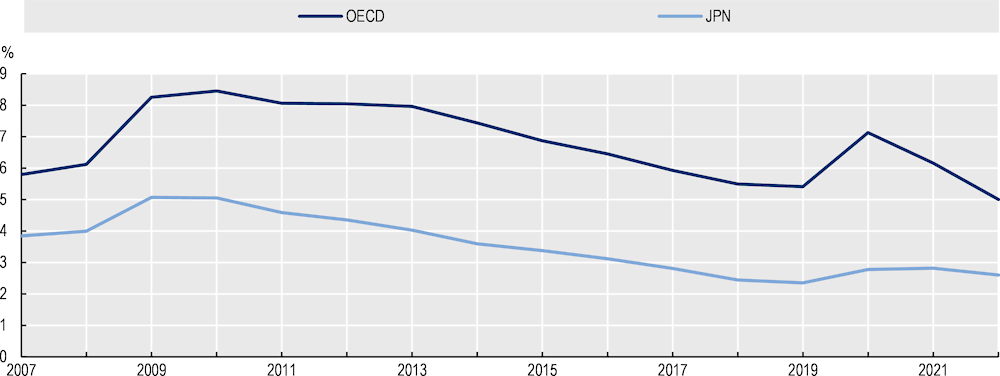

The labour market has had a sustained low unemployment rate over the last 15 years. In 2019, prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the unemployment rate was at 2.3%, below its estimated structural unemployment rate of 4.6% (OECD, 2019[2]), and 3 points below the OECD average (Figure 2.3).

Despite the setback due to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the labour market remains close to full employment. By the end of 2022, the employment rate was slightly above the 2019 level and the unemployment rate was only a quarter of a percentage point above the 2019 level.

Figure 2.3. Unemployment rate in Japan and the OECD, 2007‑22

Note: Harmonised unemployment rate as percentage of the labour force.

Source: OECD Labour Market Statistics.

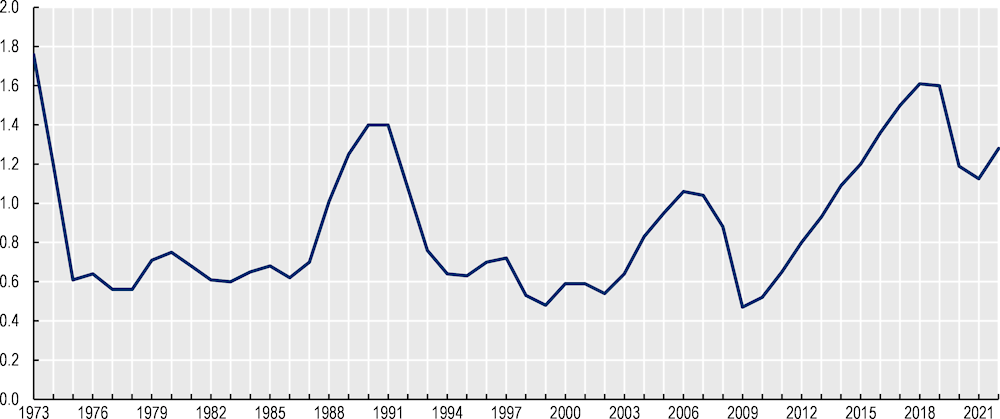

The Japanese labour market is very tight. The number of vacancies per applicant reported by Hello Work – the Public Employment Service – was 1.6 in 2019, the highest ratio since the 1970s (Figure 2.4). Despite the drop due to the pandemic, there were more vacancies than there were applicants even in 2020 and 2021.

Figure 2.4. Number of job-openings per applicant at Hello Work, 1973‑2022

Note: The job-opening rate is defined as the ratio between the number of job openings and the number of job seekers registered at the Japanese Public employment Service, Hello Work.

Source: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare.

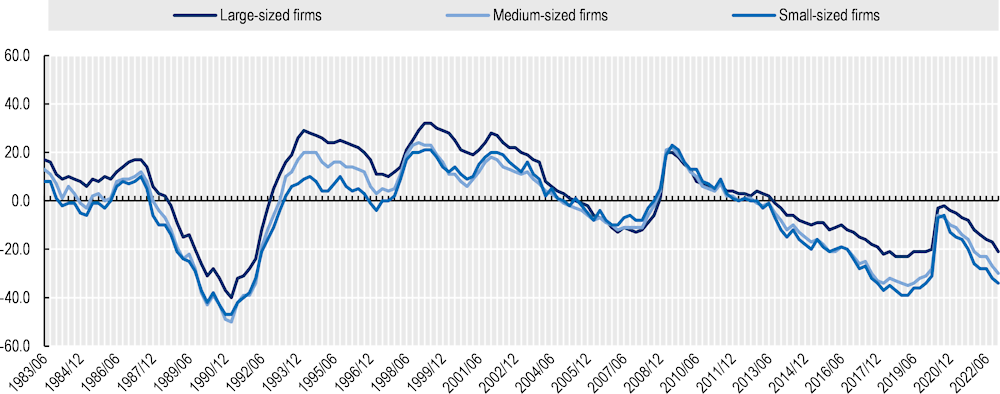

Employers are increasingly declaring labour shortages at all skill levels, across sectors and firm sizes. According to the Bank of Japan’s (BoJ) Short-Term Economic Survey of Enterprises in Japan (Tankan) survey, labour shortages declared by employers are at the highest level since the early 1990s (Figure 2.5). The diffusion index for employment conditions in all industries, calculated by subtracting the percentage of companies with a labour shortage from the percentage of those with a labour surplus, reached ‑33 in the third quarter of 2018. Despite a decrease in labour shortages declared in 2020 and 2021, the diffusion index is already back to the pre‑pandemic level.

Firms of all sizes reported increasing shortages until 2019, but small and medium firms were more likely to report labour shortages than larger firms (Figure 2.5). Two-thirds of SMEs reported labour shortages in 2019 whereas only half did so in 2015. Despite the drop in the share of firms reporting shortages by February 2022, 60.7% of SMEs did so, a similar share than in early 2020 (The Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry, 2022[3]).

Figure 2.5. Diffusion index for employment conditions by firm size

Note: The diffusion index for employment conditions in all industries, calculated by subtracting the percentage of companies with a labour shortage from the percentage of those with a labour surplus.

Source: Bank of Japan’s Tankan survey.

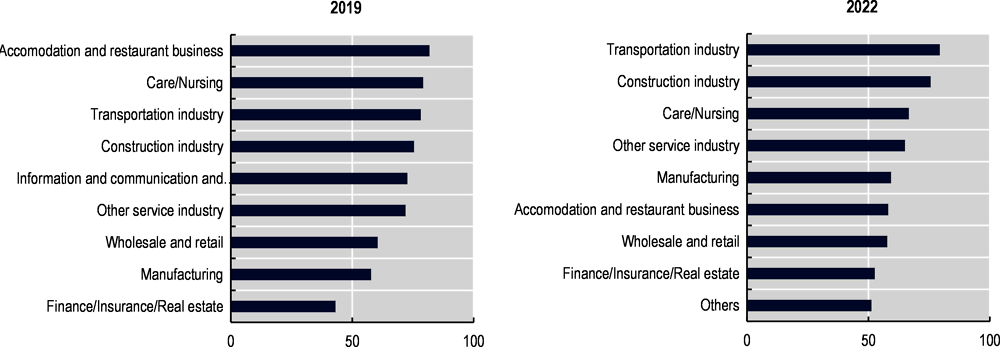

Among SMEs, the largest increases in reported shortages leading up to the COVID‑19 pandemic were in the accommodation and restaurant (81.8%), nursing care (79.2%), transport (78.2%), construction (75.4%), and ICT (72.7%) sectors (Figure 2.6). The COVID‑19 pandemic affected industries to different extents. The drop in reported shortages in 2020 and 2021 was largest in services and manufacturing. By early 2022, the share of SMEs reporting shortages in construction and transportation are back to pre‑pandemic levels. In contrast, shortages in accommodation and restaurants, or even in nursing care and ICT, remained at levels lower than pre‑pandemic.

Figure 2.6. Firms declaring shortages by sector of activity, 2019 and 2022

Source: Survey on labour shortage and Employee training/educational training, JCCI (2022) and Survey on labour shortage situation and response to workplace reform laws, Tokyo Chamber of Commerce and Industry (2020).

In some cases, firms’ difficulties in hiring seem due to a general lack of applicants, more than to skill mismatches in the Japanese labour market. In a 2019 Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training survey on labour shortages,3 60.9% of companies experiencing hiring difficulties reported that not a single candidate applied when the company had a vacancy. This was the case across different industries and skill levels: 69.3% of employers in construction reported no candidates available, as did 72.3% of those in accommodations, eating and drinking services, and 64.7% in healthcare and welfare. Noticeably fewer employers (23.6%) reported that the quality of the applicants was not at the desired level. Vacancies left with no applicants are more frequent outside of the three larger metropolitan areas.4

While most surveys do not cover the agricultural sector, the Census of Agriculture and Forestry shows that population ageing, and rural depopulation are also having a strong effect on employment in agriculture. The total number of people working in agriculture (farmers and employees) has decreased sharply during the five years prior to the pandemic, and the average age of farmers has increased to close to 70.5 In 2020, the share of farmers aged 65 and over was 69.6%, almost 5 percentage points above the share in 2015, 64.9%.

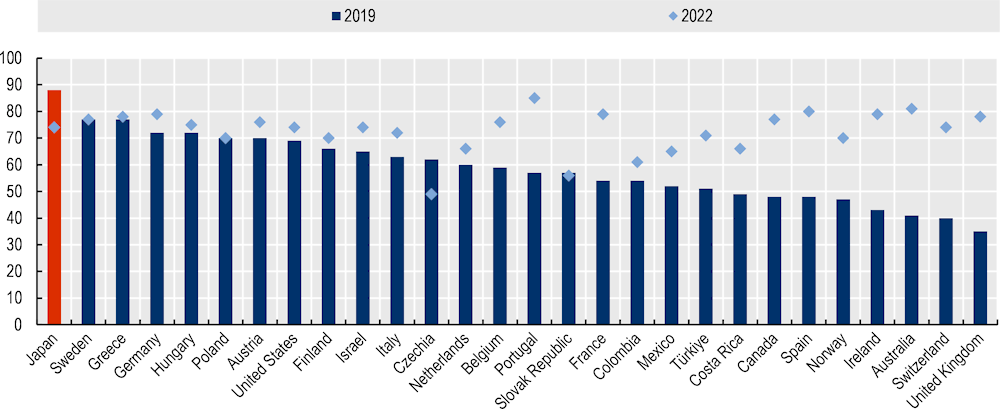

In international comparison, Japan’s shortages appear to be particularly severe. Employers in Japan were more likely to report shortages than in any other OECD country in the years leading to the COVID‑19 pandemic according to Manpower Group’s Talent Shortage survey (Figure 2.7). In 2019, 88% of surveyed employers declared having difficulties hiring, compared with 59.5% on average across the OECD countries surveyed.6

Figure 2.7. Employer reported shortages in international comparison, 2019, 2022

Source: Manpower Group survey.

Future labour shortages crucially depend on productivity growth

The most recent population projections estimate that the population aged 15 to 64 would drop to 70.76m in 2030 and to 50.78m in 2060 (National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, 2023[4]).7 This represents a decrease of 5.8% and 32.4% from the 2020 level.

Whether, and if so to which extent, the forecasted decrease in population will translate into a decrease in the labour force depends on future labour supply of the different population groups, notably of women and older workers. Future labour shortages are in turn determined by a potential mismatch between future labour supply and labour demand.

Several recent studies have attempted to forecast labour shortages (Persol Research Institute and Chuo University, 2018[5]; Japan International Cooperation Agency, 2022[6]; Works Report, 2023[7]; Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, 2019[8]). These studies estimate the imbalance between forecasted labour demand and supply to achieve a target GDP growth under different assumptions on productivity growth.8 Studies vary in the exact scenarios considered and features of the models but follow the same overall principle.

A main lesson from these studies is that the forecasted labour shortages are highly sensitive to the models’ productivity parameters. For example, setting a target of annual real GDP growth of 1.2%,9 and setting labour productivity growth at a level comparable to that observed in the past decade (low productivity scenario), both (Persol Research Institute and Chuo University, 2018[5]) and (Japan International Cooperation Agency, 2022[6]) forecast labour shortages at over 6 million by 2030, and 14 million by 204010 (Persol Research Institute and Chuo University, 2018[5]; Japan International Cooperation Agency, 2022[6]).11 In the medium productivity growth scenario, the forecasted shortages in (Japan International Cooperation Agency, 2022[6]) fall to 2.5 million by 2030 and 5 million by 2040. In the high productivity growth scenario, there are no forecasted shortages at all.

Furthermore, a main limitation of the studies cited above is that the target considered is GDP growth instead of GDP per capita. Similarly, the government’s overall economic strategy also targets GDP growth. However, GDP per capita is arguably a better measure of the population’s welfare. Given Japan’s forecasted decrease in population, targeting the growth of GDP per capita instead of GDP, would mechanically lead to lower forecasted labour shortages.

Moreover, at this stage, there is no realistic forecast available at the industry level. (Japan International Cooperation Agency, 2022[6]) and (Persol Research Institute and Chuo University, 2018[5]) extend the forecasting exercise above to the industry level. However, this forecasting exercise requires very restrictive assumptions, which considerably limits their usefulness. Labour demand by industry is estimated by dividing forecasted GDP at the industry level by industry specific labour productivity, which is assumed to grow at the same speed than in the 2010s. Labour supply by industry is assumed to grow until 2030, or 2040, at the same pace than in the previous decade. The main limitations of this approach are that industry GDP growth is taken as given and that there is no possible reallocation of labour across industries. Using this methodology, forecasted labour shortages are particularly large in the services sector, in IT, education and in medical care and welfare. In contrast, no shortages are forecasted in construction, nor in agriculture.

For the occupations for which there are more concerns about shortages, specific forecasting labour supply and demand have been undertaken in the past years. For example, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry estimated in 2019 that there will be a shortage of 450 000 IT related workers by 2030 (Ministry of the Economy (METI), 2019[9]).12,13Another example is the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare estimation of a shortage of up to 270 000 nursing staff by 2025 (Ministry of Health Welfare and Labour (MHLW), 2019[10]).

What is the role of immigrants in addressing labour shortages?

Foreign workers are part of the strategy to address labour shortages unmet by offshoring, technological progress, training, and activation policies

Recruiting more foreign workers in Japan is increasingly presented as a way to address current and future labour shortages unmet by other policy options. For example, the JICA study discussed above (Japan International Cooperation Agency, 2022[6]) presents estimations of the number of foreign workers needed to fill labour shortages arising once activation policies and potential productivity increases have been taken into account. The forecasted need for foreign labour, like that of shortages, is highly sensitive to the model’s productivity parameters. In these models, an increase in labour productivity growth mechanically leads to a lower reliance on foreign labour.

Increasing productivity is the cornerstone of Japan’s policy to address labour shortages. Boosting economic growth through increased productivity has been a key strategy of the Japanese Government in the past ten years, through the successive growth strategies by the Abe Cabinet leading to the 5th Science and Technology Basic Plan for a human-centred society, Society 5.0, driven by a system that highly integrates cyberspace and physical space. While Japan does invest a high percentage of GDP into R&D (3.3% in 2020, among the highest in the OECD), productivity growth has so far not increased as hoped for (OECD, 2024[1]). Foreign workers are also not the primary short-term solution chosen by firms to address current labour shortages. Instead, firms see increasing productivity as a main strategy to address labour shortages. According to a 2022 JCCI survey,14 60.7% of SMEs facing labour shortages answer they are trying to counteract them by increasing productivity, through training of employees; by automation; or by improving business processes. By comparison, only 31.2% say they are trying to hire “women, older workers or foreigners” to address shortages.

Automation has been particularly successful in Japan’s manufacturing. Japanese companies are world leaders in robotics. In 2020, robot density in Japan’s manufacturing sector was the third highest in the world (International Federation of Robotics).

Increasing productivity, through automation or other means, has not decreased labour shortages across all industries in the same way. According to the 2022 JCCI survey mentioned above, many more SMEs in manufacturing than in non-manufacturing activities report that technology adoption or process improvement were effective in alleviating labour shortages. More tasks in the services industry are difficult to automate.

An alternative to automation is offshoring, that is shifting production of goods and services to other countries. Foreign subsidiaries are a key component of Japan’s manufacturing. In 2021, sales by foreign subsidiaries of Japanese manufacturing companies accounted for nearly a quarter of total sales (BNP Paribas, 2022[11]). However, counteracting labour shortages does not seem the key factor driving Japanese firms’ decision to open foreign subsidiaries. According to a 2018 METI survey, only 16% of firms indicated that the cost and quality of foreign labour played an important role, whereas over two‑thirds declared wishing to serve markets with strong current and future demand (BNP Paribas, 2022[11]). Similarly, to automation, offshoring is particularly effective in manufacturing. Many jobs in agriculture and in the services may be neither offshored, nor automated. Furthermore, the impact of automation on total labour demand is unclear. While automation reduces labour demand for the automated tasks, it may also increase labour demand for more complex tasks, impossible to automate (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2019[12]). Shortages are reshuffled across tasks rather than fully eliminated.

An interesting case study is the adoption of robots in nursing care homes in Japan (Eggleston, Lee and Iizuka, 2021[13]). The study uses establishment-level data to document the changes in employment, wages, tasks and working conditions of nursing care workers following the adoption of robots. Automation did not lead to a decrease in total staff, although their job content changed. The burden of care was reduced and the retention rate of workers increased, although their wages decreased.

Foreign workers may play a role in addressing shortages unmet by offshoring, automation and the domestic labour force. It is important to understand the causes, as well as the consequences, of the shortage to design appropriate migration policies. Are labour shortages due to the lack of specific skills in the Japanese labour market? May the domestic workforce be retrained to address the shortages? Are wages too low or working conditions too difficult for the jobs to be attractive?

Labour shortages have heterogeneous consequences on the functioning of the economy and the society. Migration policy may be a tool in addressing key shortages. Examples of labour shortages in key sectors are shortages in the transportation industry which affect the whole economy; shortages in the health and care sector; shortages in agriculture or other sectors of strategic importance such as aviation or ship building.

The Japanese employment system has unique characteristics complicating the potential contribution of foreign workers

For labour migration policies to be effective, they need to account for current and forecasted labour market conditions – how labour demand, labour supply and shortages will evolve over time. Equally important are the regulations and norms of the country’s labour market.

The Japanese employment system has unique features that need to be factored in when considering how foreign workers can contribute and when designing and evaluating labour migration policies.

In the traditional Japanese employment system, firms typically recruit students straight after graduation – often hiring recruits during their last year of studies – and it is still common for workers to remain in the same firm until retirement age. This is sometimes referred to as “membership type employment” given that companies hire young graduates not for a specific position but to contribute to the activities of the company as these evolve. Consequently, job descriptions and labour contracts tend to be less specific than in other OECD countries.

Traditional employment practices are still predominant in today’s Japanese labour market. According to the 2013 Global Career Survey of college graduates between the ages of 20 and 39 conducted by Recruit Works Research Institute, 81% of college graduates in Japan found their first job after graduation while still in school, compared with 46% in the United States, 58% in Germany, and 42% in Korea (OECD, 2021[14]).

Long-term employment practices are particularly common in large firms. Approximately 40% of workers aged 50‑59 in large firms have never changed workplace, compared to only 7% in small businesses. Lifetime employment is also particularly prevalent among tertiary educated men.15 High school graduates are less likely than university graduates to be in lifetime employment irrespective of generation (OECD, 2018[15]). Frequent job changes are often perceived negatively by employers.

Alongside lifelong employment, the number of non-regular employees (i.e. not hired on a full-time long-term relationship) has increased from 20% to 40% in the last two decades (Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare (MHLW), 2019[16]). Non-regular employees are typically paid less than full-time regular employees are, they are offered less training and lack proper social security protection.

The traditional employment system is at the origin of several features of the Japanese labour market that make it challenging for immigrants to integrate into the labour market. Some of the challenges are also faced by the native‑born who hold non-regular jobs.

First, the labour market is characterised by low job mobility. There are few opportunities for mid-career workers in the primary job market. Immigrants who arrive in Japan after completing their studies will have missed the main recruitment post-graduation.

Second, given the prevalence of long-term employment, training occurs mainly within firms. Training is geared towards firm specific more than general skills. Combined with low job mobility, this has led to the under-development of mechanisms to ensure the portability of skills across firms, and in particular to the development of skill certification. Recently arrived labour migrants have no way to certify the skills they acquired abroad and ensure these are used in the Japanese labour market.

Furthermore, firm led training and long-term employment may refrain employers from hiring immigrants. Immigrants are less likely to remain in the country, and a fortiori with the same employer, than the native‑born in all countries. Thus, employers are typically less likely to hire and invest in the training of immigrants than the native‑born. Given the importance of firm training in Japan, this difficulty is more salient in this context.

Third, wages for new graduates are relatively low but increase steeply with tenure. The wage premium of working continuously in the same company in Japan is large. In particular, the earnings of Japanese workers peak later than their counterparts in other countries. Full-time working Japanese men in their early fifties earn 57% more than their early-thirties counterparts, compared to 42% in Korea and 36% in the United States (OECD, 2017[17]). Young labour migrants may not find employment in Japan attractive if they are unlikely to remain in Japan, and in the same firm, throughout their entire career.

The Japanese Government has adopted a series of measures since 2018 to reform the labour market. There are measures targeted at decreasing the duality of the labour market, increasing job mobility and ensuring wages reflect productivity rather than tenure. The reforms include legislation to ensure equal pay for equal work; measures to promote job mobility at all ages;16 subsidies to companies establishing a pay scheme based on workers’ competences rather than on seniority; and a requirement since 2020 for large companies to announce quotas of mid-career hires.

Large employers are also starting to promote labour market reforms. The Japan Business Federation, KEIDANREN, an employer association consisting mainly of large Japanese firms, has promoted developing mid-career recruitment, a shift from company led training to workers’ autonomous career development, and a shift from automatic salary increases based on age and years of service to wages that reflect performance (Japan Business Federation, KEIDANREN, 2020[18]).

Although the Japanese Employment system is slowly changing, at least in the medium term, labour migration policy needs to account for the specificities of the labour market, in terms of hiring, training and compensation.

References

[12] Acemoglu, D. and P. Restrepo (2019), “Automation and New Tasks: How Technology Displaces and Reinstates Labor”, Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 33/2, pp. 3-30, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.2.3.

[11] BNP Paribas (2022), Foreign subsidiaries, a key driver of the Japanese industry, https://economic-research.bnpparibas.com/pdf/en-US/Foreign-subsidiaries-driver-Japanese-industry-6/8/2022,46454.

[13] Eggleston, K., Y. Lee and T. Iizuka (2021), Robots and Labor in the Service Sector: Evidence from Nursing Homes.

[18] Japan Business Federation, KEIDANREN (2020), Report of the 2020 Special Committee on Management and Labor Policy.

[8] Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training (2019), Estimation of Labour Force Supply and Demand - Future Projections Based on the Labour Force Supply and Demand Model (FY 2018 version)..

[6] Japan International Cooperation Agency (2022), Toward the Realization of a Society Coexisting with Foreign Residents in 2030/40.

[20] Kambayashi, R. and T. Kato (2016), “Long-Term Employment and Job Security over the Past 25 Years”, ILR Review, Vol. 70/2, pp. 359-394, https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793916653956.

[16] Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare (MHLW) (2019), Analysis of the labour economy: challenges facing Japan: work styles and labour shortages.

[10] Ministry of Health Welfare and Labour (MHLW) (2019), Interim Summary of the Nursing Staff Supply and Demand Subcommittee of the Study Group on the Supply and Demand of Healthcare Workers.

[19] Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (2019), Current Status and Outlook of Fiscal Resources for National Pension and Employees’ Pension - Results of Fiscal Verification in 2019 (2049).

[9] Ministry of the Economy (METI) (2019), Study of IT Personnel Supply and Demand, https://www.meti.go.jp/policy/it_policy/jinzai/gaiyou.pdf.

[4] National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (2023), Population Projections for Japan (2023 revision): 2021 to 2070.

[1] OECD (2024), OECD Economic Surveys: Japan 2024, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/41e807f9-en.

[14] OECD (2021), Creating Responsive Adult Learning Opportunities in Japan, Getting Skills Right, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/cfe1ccd2-en.

[2] OECD (2019), OECD Economic Surveys: Japan 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/fd63f374-en.

[15] OECD (2018), Working Better with Age: Japan, Ageing and Employment Policies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264201996-en.

[17] OECD (2017), Investing in Youth: Japan, Investing in Youth, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264275898-en.

[5] Persol Research Institute and Chuo University (2018), Labor Market Future Estimates 2030.

[3] The Japan Chamber of Commerce and Industry (2022), Survey on labour shortage and employee training.

[7] Works Report (2023), Forecast to 2040; Labor supply-constrained society is coming, https://www.works-i.com/research/works-report/item/forecast2040.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2023).

Notes

← 1. A limitation of the dependency ratio is that it does not account for the labour market participation of workers aged 65 and over. In Japan’s case, the participation is high counteracting part of the increased share of the elderly population.

← 2. Similarly, 51.9% of individuals aged 65 to 69, were active in Japan, compared with 28.2% across the OECD.

← 3. Survey on Current Status of Labour Shortage and Work Styles, etc. Company Questionnaire, Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training (2019).

← 4. Over 65% of firms outside of the metropolitan areas declare no applicants to their job vacancies, compared with 50% in the 3 metropolitan areas.

← 5. In 2020, there were 1.4m self-employed farmers in Japan, a 22% decrease since 2015 and 39% decrease since 2005, according to the Census of Agriculture and Forestry. The number of permanent workers, employed 7 months or more per year in agriculture, decreased from 220 000 to 157 000. Similarly, the number of temporary employees also decreased from 1.5 million in 2015 to 947 000 in 2020.

← 6. The 2022 results of this international survey are at odds with the Japanese evidence presented above. The share of employers reporting shortages in Japan in 2022 is 14 percentage points lower than in 2018, whereas in the JCCI and BoJ surveys presented above, declared labour shortages are already back to the pre‑pandemic level.

← 7. These projections correspond to the medium fertility/medium mortality scenario. Yearly net migration is assumed constant at 164 000 (until 2040).

← 8. Alternatively, some studies estimate the necessary productivity growth such that labour demand equals labour supply (that is an equilibrium with no labour shortages) to reach the target GDP growth.

← 9. This is the target set by the “Growth Realization Case” of the Cabinet Office (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, 2019[19])

← 10. Similarly, estimates from Japan’s Institute for Labour Policy and Training show that in a scenario with a target of real GDP growth of 1%,labour productivity would need to increase at a rate of 1.7% to 1.9% per year until 2040 (Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training, 2019[8]).

← 11. The forecasted shortage is obtained from a “low automation” scenario in which the capital stock grows 21.2% from 2015 to 2040.

← 12. The study was done in collaboration with the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

← 13. In this study, demand for IT human resources is projected to grow by an average of 2.7% per year. Despite the increase in labour supply of IT professionals until 2030, a labour productivity growth of 0.7% per year – the growth observed in the 2010s – would lead to a shortage of 450 000 IT related workers by 2030.

← 14. JCCI Survey on labour shortages and Employee training/educational training Feb 2022.

← 15. Both the average length of service and the 10‑year retention rate of college graduates with more than 5 years of service have remained high in Japan since 1980 (Kambayashi and Kato, 2016[20]).

← 16. “Guidelines for Promoting Job Change and Reemployment Regardless of Age”.