This chapter reviews the changing profile of high-skilled labour migrants to Japan over the last 15 years, how they fare in the Japanese labour market, and their likelihood to remain in Japan for the longer term. It then highlights the main challenges Japan faces in attracting and retaining high-skilled immigrants. The chapter then focusses on the role of international students in Japan’s overall strategy to attract and retain talent. Attracting and retaining international students has been a long-standing policy objective of Japan and international students are an important feeder to high-skilled labour migration.

Recruiting Immigrant Workers: Japan 2024

5. Attracting and retaining high-skilled migrants and international students

Abstract

Attracting and retaining high-skilled workers is a common goal of OECD countries. High-skilled migrants have been shown to contribute to innovation in the host country as well as its public finances. While Japan has had well established labour migration channels for high-skilled migrants for over half a century, the number of incoming migrants remains modest.

This chapter reviews the changing profile of high-skilled labour migrants to Japan over the last 15 years, how they fare in the Japanese labour market, as well as their likelihood to remain in Japan for the longer term. It then highlights the main challenges Japan faces in attracting and retaining high-skilled immigrants.

While the first part of this chapter covers high-skilled workers who are recruited by employers in Japan; the second part focusses on international students. In many OECD countries, and in Japan in particular, international students who remain in the host country after graduation are an important feeder to high-skilled labour migration.

High-skilled labour migrants

High-skilled labour migrants in Japan: Characteristics, channels of migration used, and situation in the labour market

Most high-skilled labour migrants to Japan are prime‑aged Asian men

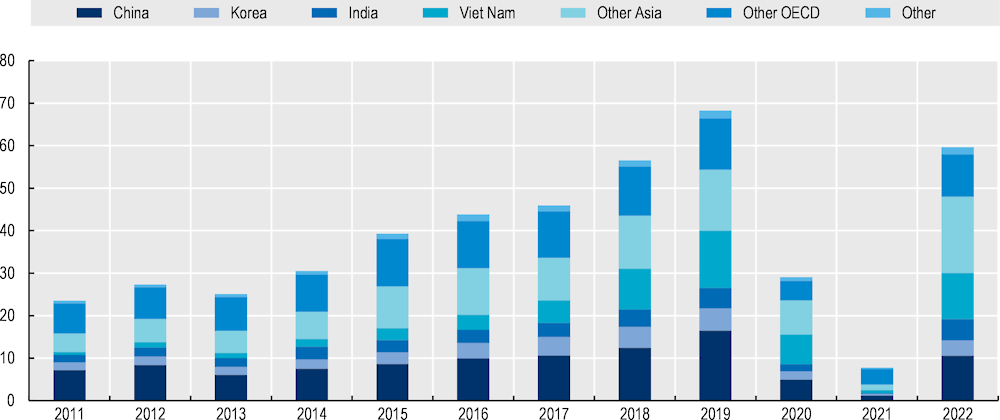

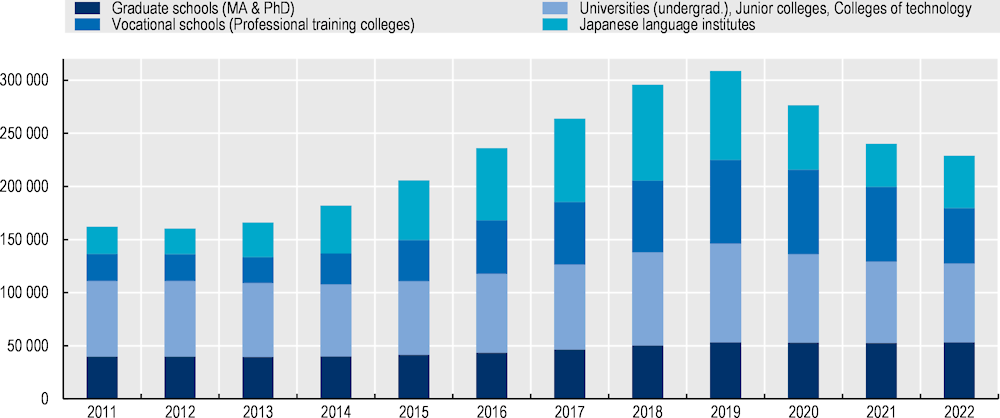

High-skilled labour migration to Japan increased significantly in the last 10 to 15 years.1 In 2019, 682 000 new skilled labour migrants entered Japan, almost three times the number in 2011 (236 000). Despite a large drop in 2020 and 2021 due to the COVID‑19 pandemic, the inflows in 2022 were at 596 000, 87.5% of the 2019 level.

The composition of the inflows by country of origin has changed over this period (Figure 5.1). More high-skilled labour migrants come from Asia in 2019 (80%) than in 2011 (67%). The share of immigrants arriving from China (the top origin country) decreased from 29.5% in 2011 to 23.6% in 2019, whereas the share of immigrants coming from Viet Nam increased rapidly from 3% to 19.2%.

Figure 5.1. Inflow of highly skilled labour migrants by nationality, in thousands, 2011‑22

Source: Immigration Services Agency.

Two-thirds of new high-skilled immigrants arrive in Japan under the Engineers/Specialists in Humanities/ International Services (EHI) status of residence (SoR) (see Chapter 4 for a detailed description of the different SoR in Japan). The increase in the inflows of high-skilled migration and the change in the country-of-origin mix were driven by inflows into this SoR. The number of migrants arriving in Japan under the EHI SoR increased five‑fold from 8 000 in 2011 to 43 800 in 2019. Viet Nam was the top country of origin in 2019 with 12 200 new immigrants, a spectacular 24.5‑fold increase, from approximately 500 in 2011.

Inflows under the other high-skilled labour SoR increased more moderately. The number of new immigrants under the Business Manager SoR tripled (2 200 in 2019); the number of Intra-company transferees doubled (9 900 in 2019); the number of Professors and Instructors increased by 30 to 40% (3 200 and 3 500 in 2019); the number of new migrants under the Skilled Labour SoR was at an average of 4 000 per year.

High-skilled labour migrants arriving in Japan, as elsewhere, are typically prime aged. Given the required education and/or experience to be admitted in Japan as a high-skilled migrant, they tend to be older than incoming low to medium skilled migrants. The average high-skilled migrant arrived in Japan between 2011 and 2019 was 32 years old.2

Unsurprisingly, EHI migrants are highly educated. In 2021, three‑quarters of EHI migrants in Japan who had completed their schooling in the country of origin had completed an undergraduate university degree, and a further 13% had completed a graduate degree (Basic Survey on Foreign Citizens in Japan, 2021).

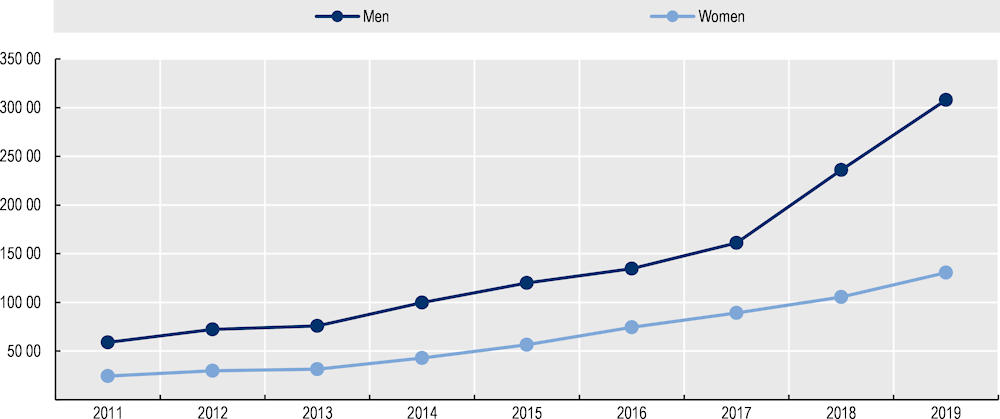

Most high-skilled migrants to Japan are men. Men represent over two‑thirds of high-skilled labour migrants (71%) arriving in Japan in 2011‑19.3 The share of men is as high as 90% among immigrants under the Skilled Labour SoR. The only SoR in which there is a gender balance is Instructor, the SoR for language (mainly English language) instructors.

Among EHI migrants, the inflows of migrant women increased similarly to those of men, albeit not as sharply in the two years leading to the COVID‑19 pandemic (Figure 5.2). Over the 2011‑19 period, a larger share of female, than male, EHI migrants came from China (30 vs. 20.5%). This share was stable throughout the years. The increase in the number of female EHI migrants from Viet Nam was similar to that of men in proportional terms (x 23), but from a smaller base. Women from Viet Nam account for 13% of all female EHI in 2019 (34% for men).

Figure 5.2. Inflows of EHI migrants by gender, 2011‑19

Source: Immigration Services Agency.

High-skilled labour migrants have the right to bring accompanying family to Japan (see Chapter 4 for accompanying family rights for the different SoR). Accompanying members are in most cases the spouse and children of the principal applicant. Eighty-four percent of adult Dependents (aged 18 and over) are women.

In 2019, 32 000 new dependents arrived in Japan, 44% of which were children. A minority of high-skilled migrants is accompanied by family members. There were 0.47 dependents (0.26 adult dependents) per high-skilled labour migrant.4 Among EHI immigrants, one‑third declare living with a spouse in 2021 (Basic Survey on Foreign Residents in FY2021).

There is likely some heterogeneity in the likelihood of being accompanied by dependents across immigrants with different characteristics (age, gender, nationality, etc.). Unfortunately, there is no available data that links individual principal applicants and their dependents. Furthermore, like in several other countries, there is a unique SoR for all dependents. Hence, even in more aggregate statistics, it is not possible to distinguish dependents of principal applicants under the different SoR.

Relative to high-skilled labour migrants, dependents are more likely to come from China (34.6%) and Nepal (16.7%). High-skilled labour migrants from Nepal account for only 3% of all high-skilled labour migrants arriving in Japan between 2011 and 2019. Ninety percent of which are under the Skilled Labor SoR, often working as chefs in Nepalese cuisine restaurants.5

Table 5.1. Top 5 nationalities of high-skilled labour migrants and dependents, 2011‑19 inflows

In percentage

|

High-skilled labour migrants |

Dependents |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

China |

24.3 |

China |

34.6 |

|

Viet Nam |

11.1 |

Nepal |

16.7 |

|

United States |

10.1 |

Viet Nam |

9.2 |

|

Korea |

7.9 |

India |

7.5 |

|

India |

7.5 |

Korea |

5.2 |

|

Other OECD |

14.4 |

Other OECD |

8.3 |

|

Other Asia |

21.9 |

Other Asia |

15.0 |

|

Other |

2.8 |

Other |

3.5 |

Note: The rows add to 100%.

Source: Immigration Services Agency.

Spouses of high-skilled labour migrants tend to be also highly educated, due to assortative matching in the marriage market. Japan is no exception. Sixty-nine percent of adult dependents living in Japan in 2021 completed their education in the country of origin. Over half of these attended university (42% an undergraduate and 13% a graduate degree) and 19% vocational education. Furthermore, over one‑quarter of all adult dependents completed their education in Japan. Fourteen percent attended university (undergraduate or graduate degree) and 13% a vocational school (Basic Survey on Foreign Residents in FY2021).

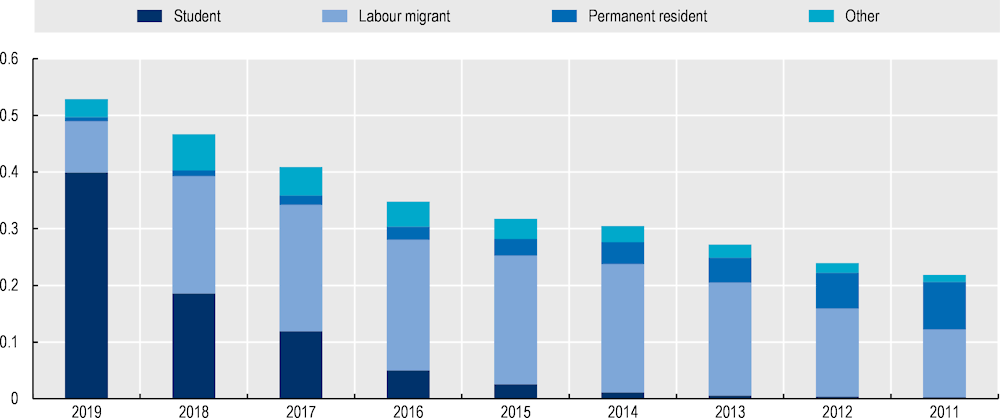

Most high-skilled labour migrants arrived in Japan to study, not through labour migration channels

Most immigrants residing in Japan under a high-skilled SoR initially migrated to Japan as international students. Fifty-two percent of foreigners who arrived in Japan between 2011 and 2019 and were in Japan under a highly skilled SoR at the end of 2022, did so to study. The share of migrants who first studied in Japan is large among migrants under the EHI SoR (59%), the Points-Based System (PBS) (51%), as well as Researcher and Professor (53 and 58%) (Table 5.2).

The share of migrants who studied in Japan is largest for high-skilled migrants under SoR for regulated professions (Nursing care and Medical Services). Over three‑quarters studied in Japan. The others migrated to the country under a designated channel, such as under an Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) (see Chapter 4 on Japan’s EPA for nurses and nursing care givers).

The share of previous international students is smaller (37%) among Business Managers. Their pathways are more diversified. While one‑third migrate to Japan already under this SoR, others initially enter the country through specific channels for start-up founders (with less restrictive conditions) or under other high- skilled SoR.

Immigrants under the Skilled Labor SoR always migrate to Japan, and remain, under this SoR. This is because the requirements for this SoR are quite specific and different from the other high-skilled statuses. The recruitment emphasis is on experience on a specific trade. Intra-company transferees are by design hired from abroad, and almost never remain in Japan under another status at the end of their assignment in Japan.

Table 5.2. Current SoR vs. SoR at arrival, at the end of 2022, 2011‑19 entry cohorts

In percentage

|

|

|

SoR at arrival in Japan |

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

EHI |

Skilled |

Bus/Man. |

PBS |

Instructor |

ICT |

Research |

Professor |

Student |

Other |

Share of Total |

|

SoR at the end of 2022 |

EHI |

35 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

59 |

5 |

76.3 |

|

Skilled |

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

7.3 |

|

|

Bus/Man. |

12 |

3 |

34 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

37 |

13 |

4.9 |

|

|

PBS |

32 |

0 |

1 |

5 |

0 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

51 |

4 |

4.0 |

|

|

Instructor |

11 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

68 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

13 |

7 |

2.0 |

|

|

ICT |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1.2 |

|

|

Research |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

33 |

8 |

53 |

7 |

0.2 |

|

|

Professor |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

1 |

30 |

58 |

6 |

1.2 |

|

|

Nursing care |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

85 |

15 |

2.1 |

|

|

Medical care |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

78 |

21 |

0.7 |

|

Note: The shares in the rows of the last column add up to 100%. The columns of the SoR at arrival add up to 100% in each row. High-skilled SoR at the end of 2022 only. Immigrants arrived in Japan in 2011‑19 who have left the country by the end of 2022 or are under a SoR that is not a high-skilled labour migration status, are not included in the calculation. The Legal and Accounting Services SoR is excluded given its small number of cases.

Source: Immigration Services Agency.

The importance of the study path differs by country of origin. Among immigrants of the 2011‑19 entry cohorts, 59% of Chinese EHI immigrants first entered Japan as international students.6 The role of the study path is similar for migrants from Viet Nam (54%). The study route is practically the sole route for immigrants from Nepal: 98% were initially international students. In contrast, EHI migrants from other OECD countries, as well as India, are more likely to complete their studies abroad. Only 28% of Korean EHI (9% of American and 8% of Indian EHI) studied in Japan.

Women are more likely than men to study in Japan prior to working as high-skilled labour migrants. Fifty-five percent of women first studied before changing status to EHI compared with 45% of men. This difference holds irrespective of the country of origin. For example, 65% of female EHI migrants from China, 75% from Viet Nam and 31% from Korea, were first international students, compared with 55%, 46% and 26% of male.

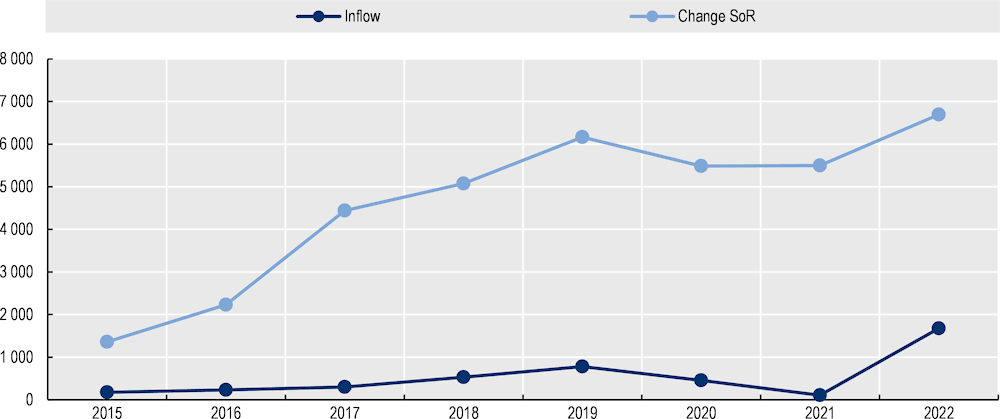

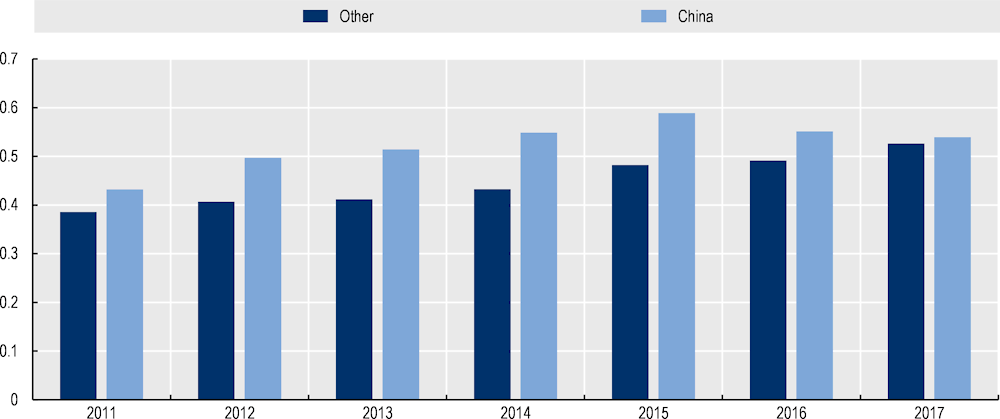

The Points-Based System has so far attracted very few immigrants from abroad

The PBS was introduced in 2012 as a way of attracting and retaining foreign talent. It was the main labour migration policy innovation on the high-skilled side. The PBS offers better conditions to eligible high-skilled migrants and their families than the other pre‑existing SoR. Immigrants under the PBS are issued a up to 5‑year permit in Japan (the longest duration issued to labour migrants) and importantly have faster access to permanent residence (currently three years of residence, instead of the usual ten, or even one year for professionals with particularly high skills (where the total number of points is 80 points or more)). In any case, like for other labour migration channels in Japan, immigrants require a job offer from an employer in Japan to be admitted under the PBS (see Chapter 4 for details on the programme).

The PBS has so far attracted few high-skilled migrants from abroad. Despite an increase over time, the intake from abroad remained under the 2000 yearly target. An evaluation of the programme shows how the increase in the uptake of the programme over time, and the changes in the characteristics of new immigrants, followed successive changes in the programme rules (for example: increased weight in the PBS scale for Japanese language knowledge) (Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication, 2019[1]).

Almost all immigrants under the PBS in Japan first entered the country under another SoR. Among the 2011‑19 entry cohorts, only 5% of immigrants under the PBS at the end of 2022 first arrived in Japan under the system (Table 5.2). Half were previous international students and one‑third were under the EHI SoR.

Despite the increase in the uptake of the PBS both from abroad and from inside Japan, the PBS intake remains small relative to the EHI intake. The number of immigrants issued the Highly Skilled (PBS) SoR represents only 9% of the number of immigrants issued the EHI SoR in 2015‑22. Considering only immigrants newly arriving in Japan, the share is even smaller at 2%.

Immigrants eligible to the PBS are usually also eligible to other SoR, mainly the EHI SoR, which do not offer the same conditions than the PBS. However, it is not clear what is the share of EHI migrants who would also be eligible to the PBS. If EHI migrants who are eligible to the PBS are not applying to be granted the status, then there are inefficiencies in the migration system that should be overcome. There could be, for example, a need to provide more information on the migration channels to foreigners. To evaluate what share of foreigners in Japan under the various SoR would be eligible to the PBS, one would need detailed information on the characteristics and histories of migrants. These data do not currently exist.

Figure 5.3. Immigration to Japan under the PBS vs. in-country change of status, 2015‑22

Source: Immigration Services Agency.

High-skilled labour migrants do relatively well in the Japanese labour market

Research on the integration in the labour market of high-skilled labour immigrants is only emerging in Japan. The Basic Survey on Wage Structure (BSWS) conducted yearly by the Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare (MHLW) introduced information on the Status of Residence in 2019 which opened the path for a better understanding of how labour immigrants fare relative to the Japanese. (Korekawa, 2023[2]) presents detailed descriptives on EHI immigrants in the Japanese labour market. The main findings are summarised below.

Approximately 40% of EHI immigrants, both men and women, work in “professional and technical occupations”, compared with 22% of Japanese men and 28% of Japanese women (Table 5.3). An additional 29% of immigrant men work as “production process workers”, compared with 21% of Japanese men. Immigrant women are more likely to work as “clerical workers” (32%), similar to Japanese women (31%). Immigrants are under-represented in managing positions. While 9% of Japanese men work as “managerial professionals”, only 2% of EHI migrant men do, a similar share than EHI migrant women (1%) or Japanese (2%) women.

Within “professional and technical occupations”, immigrants tend to cluster in some occupations. Although both foreign and Japanese men work predominantly in the different areas of engineering, foreign men are over-represented among “software engineers” (21% vs. 12% software developers), “other information processing and communications engineers” (12.1%), and “electrical, electronics, and telecommunications engineers (excluding communications network engineers)” (8.9%).

The specific occupations of immigrant women differ more markedly from those of Japanese women. In fact, they are more comparable to those of men. Japanese women in “professional and technical occupations” work predominantly in care‑related occupations. Most are “nurses” (31%), followed by “nursery childcare workers” (9.2%), “kindergarten teachers, nursery-school teachers” (6.4%), “other social welfare professionals” (4.6%), and “assistant nurses” (4.5%). Foreign women, work mostly as engineers (“other information processing and communications engineers” (24.2%), “construction engineers” (22.4%)), as well as “software developers” (14.7%) and “designers” (9.3%).

Table 5.3. Occupational distribution of EHI migrants relative to the Japanese, by gender

2019‑22

|

Men |

Women |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Japanese |

EHI |

Japanese |

EHI |

|||

|

Managerial professional |

9.3 |

2.0 |

1.6 |

1 |

||

|

Professional and technical occupations |

21.6 |

40.9 |

28.4 |

40.0 |

||

|

Clerical worker |

13.0 |

11.6 |

32.5 |

31.0 |

||

|

Sales person |

11.3 |

6.6 |

10.9 |

8.4 |

||

|

Service occupation |

5.8 |

5.7 |

13.9 |

10.9 |

||

|

Security worker |

1.0 |

0.0 |

0,2 |

0,1 |

||

|

Agricultural, forestry and fishing industry worker |

0.2 |

0.0 |

0,1 |

0,0 |

||

|

Production process worker |

21.4 |

28.9 |

9.5 |

7.5 |

||

|

Transportation and machine operators |

7.9 |

0.2 |

0.6 |

0.0 |

||

|

Construction and mining workers |

3.9 |

2.8 |

0.1 |

0.1 |

||

|

Transportation, cleaning, packaging, etc. |

4.6 |

1.2 |

2.1 |

1.1 |

||

Source: MHLW (2019‑22), Basic Survey on Wage Structure.

The Japanese labour market is often characterised as a dual labour market, in which the share of non-regular workers, that is workers who are not in long-term employment, has increased in the past decades (see Chapter 2). EHI immigrants are less likely to be regular workers than the Japanese. While 92% of Japanese men are regular workers, this is only the case of 76% of EHI men. The share of regular workers is similar among immigrant and Japanese women (77 and 78%).

High-skilled immigrants suffer a wage penalty in the labour market. The hourly wage of EHI immigrants is 35% lower than that of the average male Japanese worker. Most of this difference is due to their lower number of years of experience in the Japanese labour market and lower tenure (years spent with the same employer).7 Taking into account these differences, the wage gap is estimated at 10%, and is similar for both male and female EHI relative to Japanese men. An analysis of the wages of EHI immigrants is presented in Annex 5.A.

Immigrants currently under the EHI SoR in Japan may have been international students before or have been hired directly from abroad. It would be important to understand the labour market performance of these two immigration routes for high-skilled workers. Given the specificities of the Japanese traditional employment system, it seems difficult for immigrants who arrive in Japan mid-career to obtain “regular employment”. The career paths for non-regular employees differ markedly from those of regular employees. In particular, the wage‑experience profile of non-regular employees has been shown to be flat (OECD, 2024[3]).

The Basic Survey on the Structure of Wages does not have information on whether foreigners were previous international students in Japan. Hence, it is impossible to compare the career paths of former international students and other high-skilled migrants. However, for employees hired in the survey year, there is information on whether they are “new graduates”, that is whether they were hired through the mass hiring of graduates. Foreigners hired as “new graduates” have most likely graduated from a Japanese educational institution. The results from the survey indicate that among new hires, immigrant “new graduates” have similar initial wages than the Japanese.

The accompanying spouses of high-skilled migrants are also highly educated (see above). Their access to the labour market is in most cases restricted to part-time employment. According to the Basic Survey on Foreign Residents in fiscal year 2021, 53% of adult dependents were currently working in 2021, and an additional 24.4% had worked in Japan at some point in the past. Only 22.6% declared never having worked in Japan.

Unfortunately, there is little data available on the labour market integration of dependents. According to the MHLW Declarations of Employment, in October 2022, 29% of dependents worked in “other services”, 24% in “accommodation and food services”, and 17% in “wholesale and retail trade”. This differs markedly from the industry distribution for EHI migrants. Only 6% work in “accommodation and food services”, and 16% work in IT (1% for dependents).8 Given the high educational attainment of dependents, there is a risk they are over-qualified for the jobs they hold in Japan.

The retention of highly skilled migrants

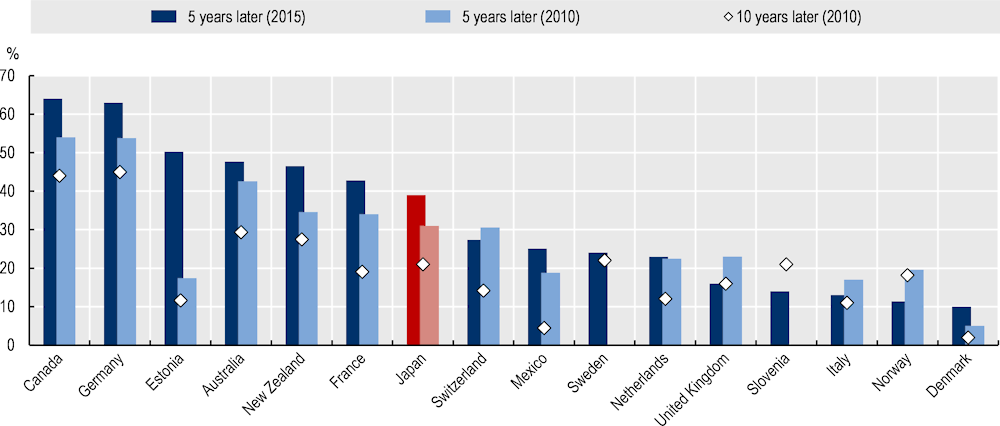

High-skilled migrants who choose Japan tend to stay in the country

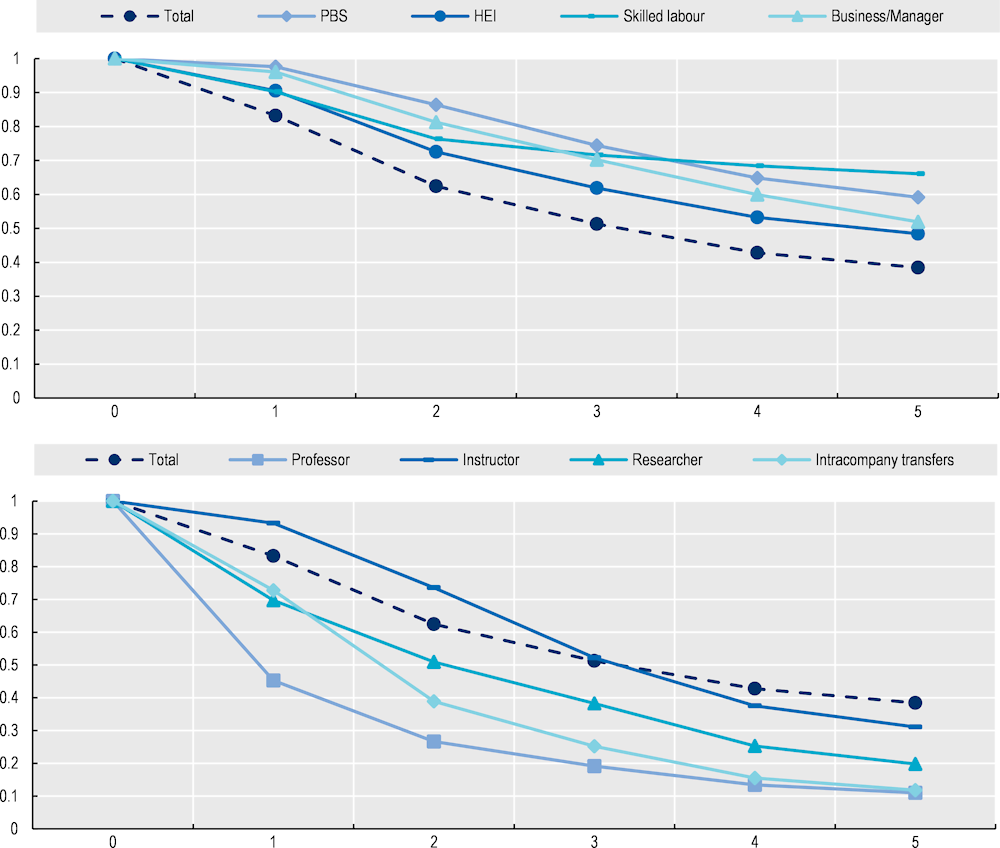

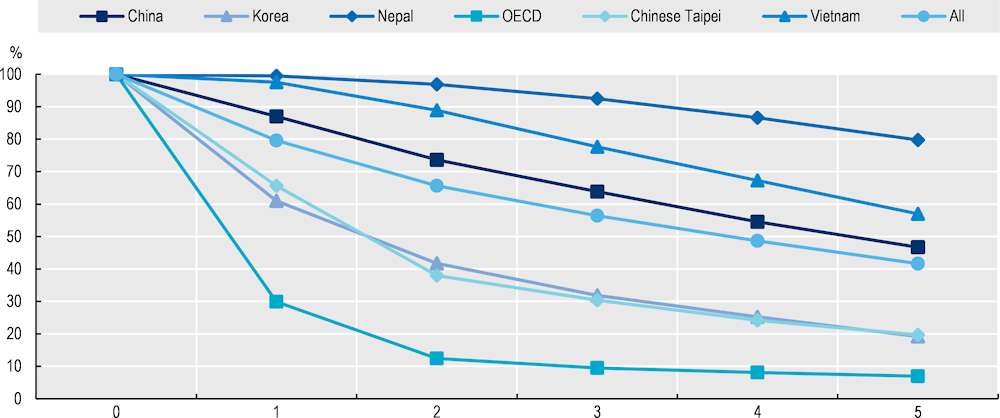

Approximately 40% of high-skilled labour migrants of the 2011‑17 entry cohorts were still in Japan five years later. The retention rate is higher among migrants arrived under the EHI or Business/Manager SoR. Approximately half were still in Japan after five years Figure 5.4. The retention rate was the largest among the few immigrants arrived in Japan under the PBS (59%) or under the Skilled Labour SoR (66%).

Figure 5.4. Retention rates (%) of highly skilled immigrants by SoR, 2011‑17 entry cohorts

Notes: For PBS, 2015‑17 cohorts only.

Source: Immigration Services Agency.

The duration of stay in Japan of immigrants under the several high-skilled SoR differs markedly, despite all permits being indefinitely renewable. Over half of Professors stay one year or less in Japan. These are mainly visiting or exchange scholars. Intra-company transferees also have relatively short stays. Sixty percent stay in Japan for 2 years or less and only 10% stay in Japan for 5 years or more. In contrast, Instructors have longer stays. Half stay three years or more in Japan, and 30% stay more than five years.

The retention rate of EHI migrants (50%) compares favourably with those of high-skilled migrants in European OECD countries. For example, the 5‑year retention rate of high-skilled migrants arrived in the early 2000s was estimated at 35% for migrants in the Netherlands (OECD, 2016[4]), 22% in Norway (OECD, 2014[5]) and 25% in Germany (OECD, 2013[6]). In settlement countries, such as Australia, Canada or New Zealand, the retention rates of high-skilled migrants, who are accepted immediately as permanent residents, tend to be higher. The 5‑year retention rate was estimated at 80% in New Zealand for the 2004‑11 cohorts (OECD, 2014[7]). In the largest provinces of Canada, the three‑year retention rates of economic migrants were above 80% for the 2005‑15 entry cohorts (OECD, 2019[8]).

The intention of EHI immigrants to remain in Japan is confirmed by the Basic Survey on Foreign Residents in FY2021. Most (62%) EHI immigrants in Japan declare wanting to stay in the country for the rest of their lives, and a further 15% would like to stay in Japan for an additional 10 years.

Given that the PBS offers a fast track to permanent residence, one would expect the retention rate of the few immigrants arrived under this programme to be higher. The access to permanent residence after 3 years in the country has been possible since 2017, however there has been no clear increase in the retention rate of the latest entry cohorts after 5 or 3 years in the country. The intake of migrants through the PBS has increased in the last years. It will be important to monitor the stay rates of the new entry cohorts, to evaluate also whether with improved conditions of stay, the retention rate increases.

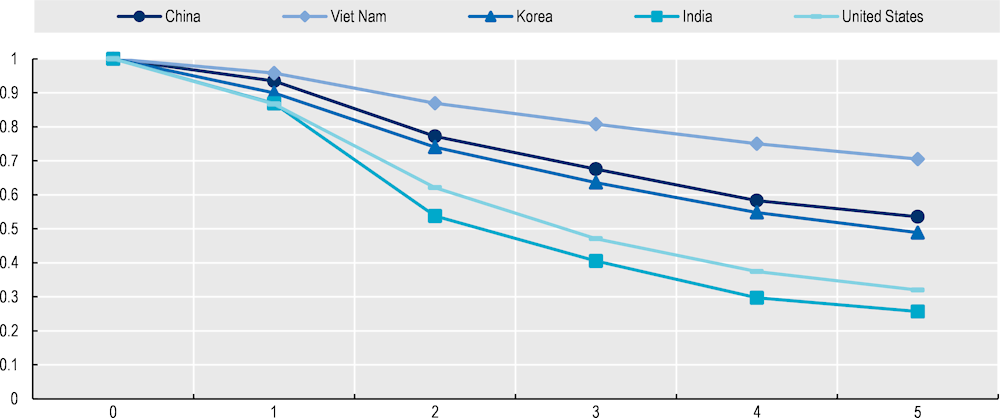

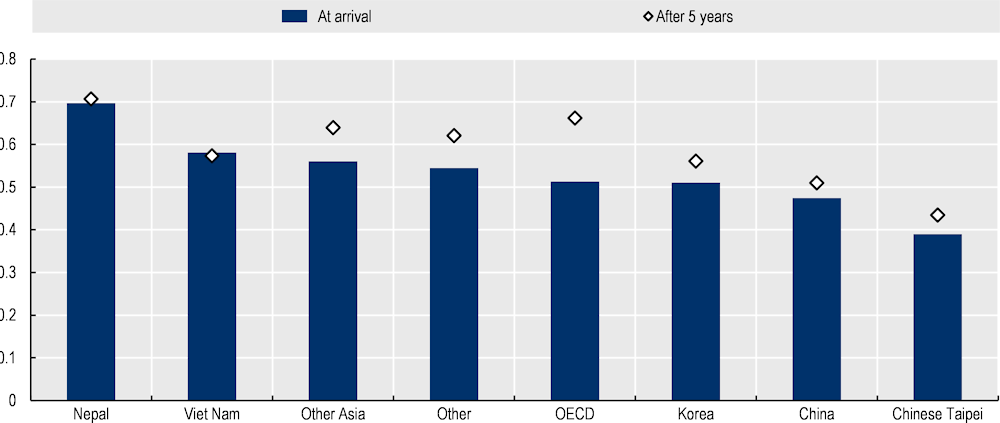

Retention rates crucially depend on country of origin

The retention rates differ across immigrants’ countries of origin (Figure 5.5). Among Chinese EHI immigrants, the largest nationality group, 54% remained in Japan 5 years after entry. Among Viet Namese immigrants, the fastest growing group, this rate is significantly larger at 71%. Among immigrants from the United States and India (the 4th and 5th top nationalities of EHI migrants) only 32% and 27% were in Japan after 5 years.

The differences in retention rates across nationalities exacerbate the change in country-of-origin composition of recent high-skilled immigration to Japan. The share of immigrants from other Asian countries, mainly Viet Nam, increased in the most recent entry cohorts. Immigrants from Viet Nam are also more likely to remain in Japan for longer. This further increases their contribution to the high-skilled labour force of Japan.

Figure 5.5. Retention rates (%) by nationality, 2011‑17 entry cohorts

Skilled workers who migrated to Japan under the EHI SoR

Source: Immigration Services Agency.

Figure 5.6. 5‑year retention rates by entry cohort, by nationality, 2011‑17 entry cohorts

High-skilled workers who migrated to Japan under the EHI SoR

Source: Immigration Services Agency.

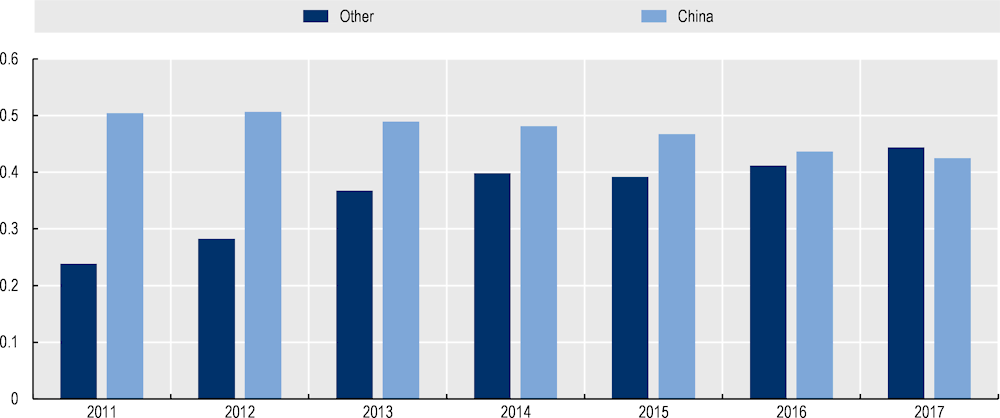

The retention rate of EHI immigrants has increased over time for migrants of most countries of origin. Excluding immigrants from China, the 5‑year retention rate increased from under 40% for the 2011 entry cohort to a little over 50% for the 2017 cohort. For Viet Namese immigrants in particular the 5‑year retention rate increased in the latest entry cohorts. The 5‑year retention rate of Vietnamese EHI immigrants was 77.6% for the 2017 entry cohort compared with 65.3% for the 2011 entry-cohort. For Chinese EHI immigrants, the retention rate decreased among the latest entry cohorts. It will be important to monitor whether the retention rate of the largest group of high-skilled migrants to Japan continues to decrease.

High-skilled immigrant men tend to stay in Japan longer than women. Men are 15% more likely than women to stay in Japan 5 years or longer. Among EHI immigrants, the gender gap is slightly lower at 10.6%. The 5‑year retention rate for EHI women is 45.2%, compared with 50% for men. EHI women are also less likely to state they would like to remain in Japan for the rest of their lives (58% compared with 65.4% of EHI men), according to the Survey on Foreigners in Japan (2021). Differences between immigrant men and women in terms of entry cohort, status of residence, country of nationality do not explain this gender gap in retention rates.9

While the gender gap in retention rates is large among immigrants from Viet Nam (12.5 percentage points), India (12.4 percentage points) and the United States (13.4 percentage points), it is smaller among immigrants from Korea (7.1 percentage points) and inexistent among immigrants from China.

Challenges in attracting high-skilled migrants

The framework for high-skilled labour migration to Japan is favourable in international comparison. Chapter 4 reviews the migration framework in detail. Nevertheless, Japan faces challenges in attracting and retaining high skilled foreigners that are not directly related to migration policy. This section reviews challenges faced by immigrants and their families in integrating into the labour market and in society.

Fluency in Japanese remains a pre‑requisite in most of the labour market

Fluency in the host country language is a main challenge for attractiveness of all non-English speaking countries in the OECD. Lack of fluency in the host country language hinders high-skilled migrants prospects in the labour market and their integration in society. In Japan, the expectations from employers with respect to language skills are high. According to a survey of almost 500 companies with experience or interest in hiring foreign workers, over three‑quarters of employers would expect international students to have “native level” or “advanced business level” Japanese when joining the company. In contrast, less than 1% would be satisfied with “everyday conversational level” (Disco Calitus Research Co., 2020[9]) .

Japanese larger companies and multinationals have started introducing English as a second, or in some cases as a first, working language as a means to attract talent and expand their activities abroad. An example which has attracted public attention was that of the decision in 2010 of the Japanese conglomerate Rakuten Group, Inc. to request that all their staff learn English within two years (Neeley, 2017[10]). Since then, many large Japanese companies have introduced requirements to promote the use of easy Japanese and/or English among staff and in official communications. Additional measures taken by large companies to attract foreign talent are presented further in this section.

Early career wages are low, and the traditional employment system hinders mid-career hires from abroad

Wages in Japan are low relative to other OECD countries and the gap has increased in the past decade. In 2021, the average yearly wage, adjusted for purchasing power parity, for a full-time worker in Japan was 77% of the OECD average, and 53% of that in the United States, the country with the highest average wage. In 2010, Japan’s average wage represented 83% of the OECD average and 61% of the average wage in the United States. Currently, Japan ranks 24 out of the 36 OECD countries, with a similar average wage to Italy or Spain.

Japan’s attractiveness to high-skilled labour migrants is hindered by low wages relative to the main OECD destination countries. This is particularly important for young labour migrants who would not intend to spend their whole life in Japan. Wages in Japan increase steeply with tenure, mainly so for high educated men in regular positions (see also Chapter 2). Hence, even more so than average wages, wages upon entry in the labour market are low in international comparison.

Furthermore, wages in Japan have decreased relative to the main countries of origin of current high-skilled migrants to Japan. The share of incoming high-skilled immigrants from China and Korea has already started to decrease in the past decade.

Concurrently, the main self-reported problem of EHI migrants in the Japanese labour market is low wages. According to the Basic Survey on Foreign Residents in FY2021, 38% of EHI immigrants reported low wages as being an issue, compared with 16% who reported difficulties with long working hours or in being able to take leave.

Wages are just one of the factors of attraction for high-skilled migrants. While career concerns dominate the main reason for EHI migrants to have migrated to Japan, interest in Japan’s culture and society also rank high. In the Basic Survey on Foreign Residents inFY2021, 39% of EHI migrants declare the main reason to migrate to Japan was to “acquire skills and improve [their] future career”, and for a further 17% the main reason for migration was study. For 26% of respondents, the main reason was because they “like Japan”.

A distinctive feature of the Japanese labour market is the bulk hiring of recent graduates. Companies typically recruit students before they finish their studies. The academic year in Japan goes from April to March and new graduates are expected to start their first job in April following graduation (see also Chapter 2). Immigrants arriving after completing their studies abroad will have missed the main recruitment cycle.

Job mobility and mid-career recruitment remain low in Japan in international comparison (Kambayashi and Kato, 2016[11]), which makes the integration of high-skilled workers from abroad difficult.

Recent policies aiming to change employment practices may improve Japan’s attractiveness to high skilled migrants. Employment practices are changing, especially in larger companies. The Japanese Government has adopted a series of measures since 2018 to reform the labour market. There are measures targeted at increasing job mobility and ensuring wages reflect productivity rather than tenure.

Rethinking the role of the spouses of high-skilled immigrants in the labour market

The accompanying spouses of high skilled migrants may apply for an authorisation to work part-time (up to 28 hours per week). Spouses of immigrants under the PBS may apply to a Designated Activities SoR and work full time in a set of high-skilled occupations. Additionally, spouses may apply for their own high skilled SoR if they have secured a qualifying job with a Japanese employer (See Chapter 4 for a detailed description of the migration framework).

Unfortunately, there is no available data at this stage that would allow studying immigrant families. The data on immigrant status processed by ISA does not link the principal applicant with their spouse. It is not possible to know whether Dependents change their status to a high-skilled migrant status, for example EHI, in Japan. There is also no information on the characteristics of Dependents (nor on the corresponding principal applicant) who apply for an Authorization to Work. For dependents of immigrants under the PBS, we do not know the share who apply for a Designated Activities visa, nor their characteristics.

As documented in the section above, over half of Dependents do work in Japan. Despite the relatively high educational attainment of spouses, these tend to work in Accommodation and food services, Retail and trade, and other services (see section above) which indicates they may be overqualified for the jobs they find in Japan.

Many OECD countries are trying to support dual careers of high-skilled migrants to attract skilled migrants, but also to reap the potential of Dependents, who tend to be highly skilled. In this context, it would be important to better understand the labour supply and career choices of high-skilled immigrants to ensure Japan is not missing out on an already available pool of talent.

Dependents also face challenges in integrating in the Japanese labour market that are not driven by the restrictions imposed by immigration policy. First, Japanese language proficiency is likely to be a difficulty. According to the Basic Survey on Foreign Residents in FY2021, the language skills of foreigners under the Dependent SoR are significantly lower than those of EHI immigrants. Thirty-seven percent of Dependents can only use basic greetings in Japanese or speak no Japanese at all. Only 7% can use Japanese effectively (Table 5.4). The lack of Japanese proficiency is likely to lead to spouses accepting jobs that do not match their educational qualifications.

Table 5.4. Self-declared language proficiency, Dependents vs. EHI

In percentage, 2021

|

Dependents |

EHI |

|

|---|---|---|

|

I can barely speak any Japanese |

6.7 |

1.6 |

|

I can use basic greetings |

30.2 |

6.3 |

|

I can speak at a conversational level |

26.6 |

16.6 |

|

I can talk about familiar topics |

14.9 |

14.4 |

|

I can participate in long conversations |

5.0 |

14.6 |

|

I can use Japanese effectively |

7.3 |

17.0 |

|

I can talk about a variety of topics freely |

9.3 |

29.4 |

Note: The rows may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Source: Basic Survey on Foreign Residents in Fiscal Year 2021.

Furthermore, as documented above, most Dependents are women. Immigrant women also face the challenges encountered by Japanese women in the labour market. The gender wage gap in Japan is the fourth larger in the OECD (OECD Labour Force Statistics database). Most of this wage gap is due to the high share of women who work as non-regular employees. Two-thirds of non-regular workers are women and the wages of non-regular workers have been shown not to increase with experience in the labour market.10 Furthermore, non-regular workers are more likely to work part-time. Japan has a high share of women employed part-time (39%) compared with 24% on average across the OECD in 2021 (OECD Labour Force Statistics database).

One of the reasons for Japanese married women’s choice of working part-time in non-regular jobs is the high effective marginal tax rates on labour income of second earners. There are several incentives for second earners to keep their earnings below JPY 1.5 million (USD 10 021), or even JPY 1.3 million (USD 8 685). First, there is a spousal deduction from the income tax of the main earner. It is currently at JPY 1.5 million.11 Some employers also pay a spousal allowance conditional on low earnings of the spouse. Moreover, employees’ spouses whose earnings are below JPY1.3 million do not need to pay social security contributions. All these disincentives to female full participation in the labour market apply also to the spouses of high-skilled immigrant workers.

Integration into Japanese society is challenging

Integrating into Japanese society remains a challenge for migrants. As discussed in Chapter 4, despite some improvement, the residence requirements to obtain permanent residence are stricter than in other OECD countries. Acquiring permanent residence and even more so acquiring citizenship are an important vehicle of immigrant integration.

Given that the stock of immigrants in Japan is low and not very diversified, it may be particularly difficult for immigrants of new or under-represented countries of origin to settle. A case study of Indian IT professionals abroad highlighted the difficulties they had integrating in Japan that go beyond migration policy, as well as some of the recent improvements (OECD/ADBI/ILO, 2018[12]). For example, the establishment of an international school with India’s Central Board of Secondary Education curriculum, the creation of places of worship, and the settlement of an Indian community in greater Tokyo have helped with the integration of Indian IT professionals.

Japan has only recently started developing integration policy. In 2019, the government formulated the Comprehensive Measures for Acceptance and Coexistence of Foreign Nationals. These include a package of integration measures, such as increased options to learn Japanese, the promotion of the use of plain Japanese in information dissemination and consultation services, or increased support for foreign children in schools. Japan is currently the only OECD country in which schooling is not compulsory for foreign children. Furthermore, in 2022, the government formulated the Roadmap for the Realization of a Society of Harmonious Coexistence with Foreign Nationals, which shows the visions of a society of coexistence to aim for, and the medium-to long-term issues that should be addressed. The implementation status of the Roadmap is to be assessed annually to confirm its progress and review the measures as needed.

According to the Basic Survey on Foreign Residents in FY2021, immigrants in Japan feel discriminated against in several social and economic contexts. This is not specific to Japan but may contribute to hinder the country’s attractiveness to high-skilled workers. For example, a third of EHI immigrants have felt discriminated against when searching for a home. The housing market is the context in which a higher share of foreigners declares feeling discriminated against (21% of all foreigners in the survey). Furthermore, approximately one-fifth of EHI immigrants feel discriminated against also in the labour market when looking for work (23%), at work (23%), or in the financial market, when opening a bank account (18%) or when applying for a credit card (22%).

From accepting to attracting high-skilled migrants

While there are few barriers to high-skilled migration, Japan has not developed an overall strategy to attract high-skilled immigrants. Consequently, Japan does not have a unique web platform that centralises all information on labour migration to Japan.

Currently, there are scattered sources of information on labour migration to Japan. A website targeted at highly skilled professionals, “Open for Professionals” was created by JETRO in December 2018 following the government’s “Growth Strategy 2018”. The site contains information on living and working in Japan, in Japanese and English, including a series of video interviews with highly-skilled talents working in different fields in Japan. The site contains also links to relevant news and documents from other government agencies, such as METI, ISA, MOFA and JASSO.

ISA’s website also contains information on the different statuses of residence, immigration policies, reports, and statistics. Furthermore, it hosts the recently launched “A Daily Life Support Portal for Foreign Nationals” with practical information, including the “Life and Work Guidebook” in 16 languages.

Building on these websites, Japan could consider creating a whole of government portal for labour migration to Japan. Examples of such government run platforms in other OECD countries are Make it in Germany, Work in Estonia, Working in Sweden, among others (Box 5.1).

A job offer from a Japanese employer is a pre‑requisite to work in Japan as a high-skilled migrant. However, it is currently difficult for foreigners to apply for jobs from abroad or even have a sense of what jobs are open to high-skilled migrants in Japan. JETRO’s website features a list of Japanese companies (named OFP list) interested in hiring foreign professionals. The listing indicates the sector of activity of the company, the broad expertise required (for ex. Sales/Marketing or Engineering) whether the company has an internship programme and whether English proficiency is sufficient for the job. The listing of companies does not show real time vacancies. The website is not linked to the public employment services, Hello Work. A number of OECD countries have integrated vacancies into information portals for potential immigrants, such as Make It in Germany, or collect profiles of interested candidates, such as New Zealand Now and Skill Finder (Box 5.1).

Box 5.1. OECD examples of web-portals for migrants and employers

Make it in Germany

The web-portal Make it in Germany is a joint initiative of the Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs, the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, and the Federal Employment Agency. It provides labour migration and international matching information tailored to qualified professionals and employers.

The website section dedicated to prospective migrants contains multilingual information on occupations in demand (including available job listings from the Federal Employment Agency), labour migration and social security regulations, opportunities for family members as well as life in Germany. It also links to another government run website, Recognition in Germany, which provides a search engine for foreign professionals to access tailored information on the recognition procedures that they would need to apply for, depending on their prospective occupation and work location.

The employer section features detailed information on migration regulations, as well as diversity management and integration. Best practices in these areas are also presented. To enhance interactivity and accessibility the portal has a mobile application version and includes email, chat and hotline services.

New Zealand Now and Skill Finder

Since 2012, New Zealand’s Ministry of Business, Innovation & Employment (MBIE) has run a platform allowing foreign candidates to submit their profiles and New Zealand employers with eligible vacancies to contact potential matches. The platform uses the New Zealand Now immigration portal to direct candidates to register, and an interface – Skill Finder – for employers. Skill Finder is unrelated to the immigration process and the visa for which the candidate will apply.

Through its promotional site, New Zealand Now, foreigners can register their interest and provide basic information on occupation, experience and education. There is no guarantee that candidates will be contacted. There were more than 1 million “e‑mailable prospects” in 2021. New Zealand actively promotes New Zealand Now, through social media, search engine advertisement and job fairs. People registering with New Zealand Now also receive a wider range of immigration-related information.

Employers or recruiters can query Skill Finder to see how many New Zealand Now profiles match their requirements. Employers and recruiters may search the database by occupation, academic qualifications, residence and work experience. If they wish to contact registered profiles, they must submit specific vacancy details to MBIE, which reviews them. Vacancies must be for skilled positions or meet Accredited Employer requirements. MBIE then sends an e‑mail inviting candidates to apply for the position.

Source: OECD (2019[13]), Building an EU Talent Pool: A New Approach to Migration Management for Europe, www.doi.org/10.1787/6ea982a0-en; OECD (2022[14]), Feasibility Study on the EU Talent Pool.

JETRO offers also the possibility for companies to apply for hiring support from a dedicated co‑ordinator. If the company is selected, it benefits from a follow up for the entire recruitment process. The maximum number of participating companies is capped at 300. In 2021, 184 foreign highly skilled professionals were hired in 140 companies that benefited from this support.

The role of hiring Japanese companies in attracting and integrating high-skilled workers is key. Keidanren (Japanese Business Federation) recently surveyed its members on measures used at the company level to attract and integrate foreign high-skilled workers. The results show that large Japanese companies are introducing a range of measures to integrate foreign highly skilled professionals, including allocating mentors for new arrivals within the company who also help with administrative procedures outside of work; improvement of in-house environment (training programmes for cross-cultural understanding, promoting the use of Easy Japanese, and English learning for Japanese staff); revision of personnel systems (offering more job-based positions, and more options for leave); support for acquisition of Japanese skills (in-house but also financing external language training); building a link with the local community by for example creating opportunities for immigrants to join local festivals, clean ups, etc. in co‑operation with local governments.

International students

International students have increasingly become key players of OECD countries’ strategies to attract global talent. International students who choose to remain in the host country after graduation typically integrate more easily in the labour market. In contrast to labour migrants arriving in the host country with foreign qualifications, international students have the same formal qualifications than the native‑born, readily accepted by employers. Furthermore, international students may have a better knowledge of the language and culture of the host country acquired during their studies.

The hedge of international students, relative to labour migrants, is particularly important in the case of Japan. Japan, like many other non-English speaking countries, does not have a large pool of potential labour migrant who already speak the language, which makes talent attraction harder. Second, the traditional Japanese Employment System is difficult to navigate for immigrants and much easier to integrate right after graduation (see Chapter 2 for a discussion on the specificities of the Japanese labour market).

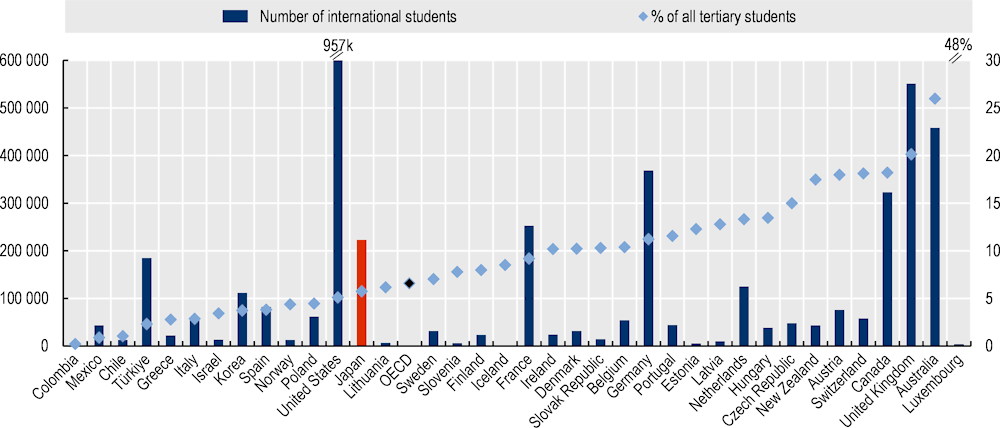

A portrait of international students in Japan

Japan hosts approximately 5% of all international students in the OECD. It ranks 7th as destination country behind the largest English-speaking countries (United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada) and the two largest European destinations (Germany and France) (OECD, 2022[15]). The share of international students enrolled in Japan as a share of all tertiary students was at 6% in 2020, slightly under the OECD average (Figure 5.7).

Figure 5.7. The number and share of international students among all tertiary students

International students total (left) and as a share of all tertiary students (in percentage right), 2020

Note: Divergence in data sources and definitions can lead to shares different from those reported by national sources. 2020 data typically refer to the academic year 2019/20 and thus the impact of COVID‑19 is most visible in countries where the data refer to 2020, notably Australia and New Zealand.

Source: OECD Education at a Glance Database 2020, accessed 2023.

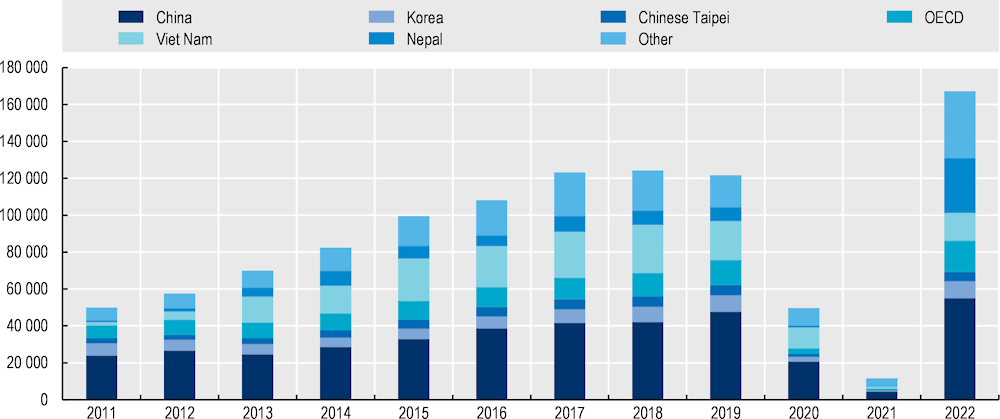

The inflows of international students have increased sharply

The number of international students has increased sharply since the early 2010s. The number of international students living in Japan almost doubled from 2012 to 2019, from 181 000 to 346 000. Despite the sharp drop in student inflows during the COVID‑19 pandemic, the stock of students in Japan at the end of 2022 was back at 300 600, or 12% lower than at the end of 2019.

Annual inflows of international students to Japan increased from under 50 000 a year in the early 2010s to 122 000 in 2019, and 167 000 in 2022, after two years of very low inflows due to the COVID‑19 pandemic Figure 5.8.12

Figure 5.8. Inflows of international students by nationality, 2011‑22

Source: Immigration Services Agency.

Most international students in Japan come from Asia. In 2021, 86% of international students arriving in Japan were citizens of another Asian country, and this share has been relatively stable over the period. The countries of origin of international students have changed over time. Among international students arriving in Japan in 2011, 48% were from China and 14% from Korea. Among those arriving in 2019 only 39% and 7% were from these two countries. Conversely, the number of international students arriving from Viet Nam increased 11‑fold from 2011 to 2019, and that from Nepal over 7‑fold. By 2019, these two countries together represented almost one‑quarter of the total yearly inflow of international students.

Many international students attend Japanese language schools in Japan before enrolling in post-secondary education in the country

In Japan, higher education starts upon the completion of 12 years of education at the age of 18. The Japanese higher educational institution (HEI) system consists of universities (including undergraduate and graduate schools), junior colleges (typically 2‑3 years of undergraduate degrees) as well as vocational oriented schools (professional/specialised training colleges as well as colleges of technology called KOSEN).

International students in Japan may attend any Japanese university, graduate school, junior college, college of technology, professional training college, university preparatory courses or Japanese language schools. International students may be either degree‑seeking or non-degree seeking students. Virtually all international students stay in Japan under a Student SoR.13

There are also University Preparatory Courses designed by Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) for international students whose country’s secondary education curriculum lasts less than 12 years. These courses are a pre‑condition to enrol in Japanese post-secondary education. In the preparatory course, students study not only the Japanese language but also the basic subjects required for university entrance.

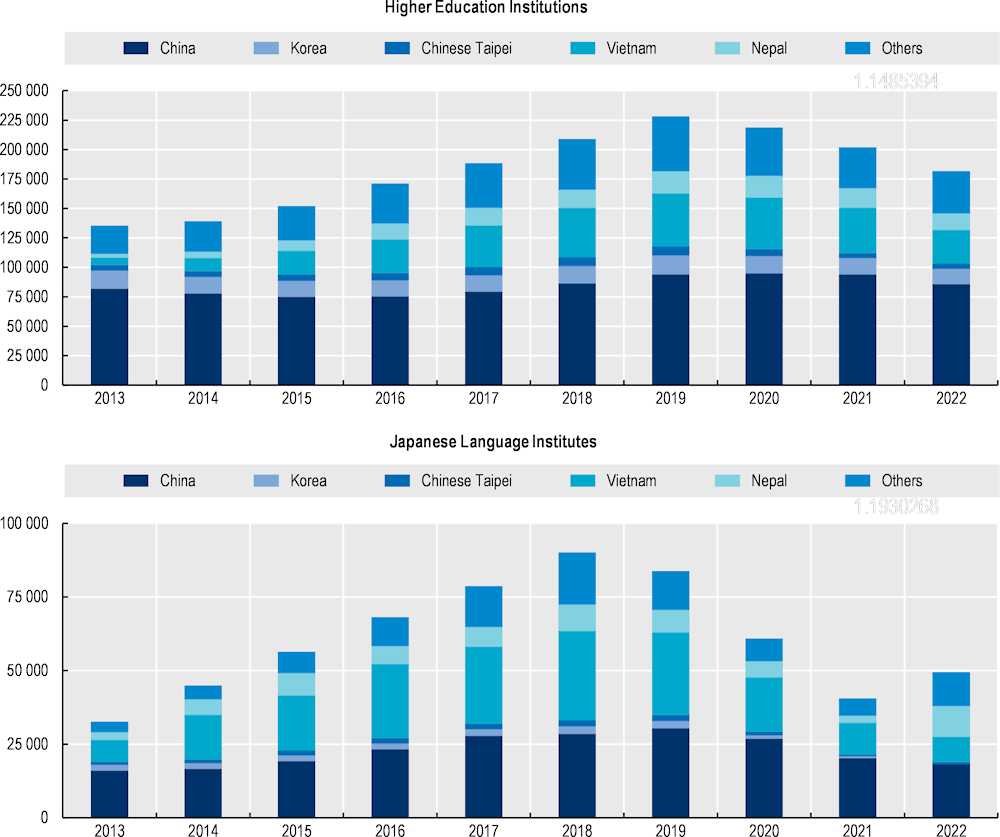

Many international students attend Japanese Language Institutes (JLI) in Japan before enrolling into tertiary education. Approximately half of international students enrolling in an undergraduate degree or in vocational school in Japan attended a JLI beforehand (JASSO, 2022[16]) International students in JLIs account for a large share of the overall international student population. In 2022, one-fifth of international students in Japan were enrolled in a JLI (Figure 5.9). This share was even larger before the COVID-19 pandemic, over one‑quarter in 2019.

Figure 5.9. Stock of international students by educational institution type, 2011‑22

Note: As of 1 May, each year. International students attending University Preparatory courses are not included. Their number has also increased over time but remains small. There were 1 619 students attending such courses in 2011, 3 518 in 2019 and 2 351 in 2021.

Source: JASSO (2023[17]), Result of International Student Survey in Japan, www.studyinjapan.go.jp/en/statistics/zaiseki/.

The number of international students enrolled in vocational schools increased by more than that in universities

The number of international students in JLIs and in vocational schools has increased significantly in the last decade. From 2011 to 2019, the number of international students in JLIs and that in vocational schools more than tripled. The number of international students attending undergraduate degrees at university, junior colleges or graduate programmes increased only by 30% in the same years (Figure 5.9).14

The change in the countries of origin of international students over the last decade is visible both in JLIs and HEIs (Figure 5.10). In 2013, international students from China (Korea) account for 49% (6%) of all international students in JLIs, whereas by 2019, they account only for 36% (3%). The decrease is also striking, perhaps even more so, among international students in HEIs. In 2013, international students from China (Korea) account for 60% (11%) of all international students in HEIs, whereas by 2019, they account only for 41% (7%).

International students from Viet Nam already accounted for 23% of international students in JLIs in 2013, and their share increased to 34% until 2019. However, Viet Namese students accounted for only 5% of international students in higher education institutions in Japan in 2013. By 2019 they accounted for 20%.

The rise of Vietnamese students in higher education institutions in Japan coincides with the increase in the number of international students in vocational educational institutions. Unfortunately, there is no data available on the breakdown by nationality of international students for the different types of higher education institutions separately.

Figure 5.9 and Figure 5.10 do not take into account international students who stay in Japan for less than one‑year, “short-term international students”. These are typically non-degree seeking students. However, there are no separate statistics on non-degree seeking students, only on short-term international students. The country of origin mix of short-term international students differs from that of the overall international student population. In 2019, pre COVID-pandemic, one‑third of incoming short-term international students came from China, 10% from Korea, 8.5% from Chinese Taipei, and 18% from the United States, France and Germany (9.3%, 5% and 3.5% respectively).15 Only 2.5% came from Viet Nam.

Figure 5.10. Main countries of origin of international students in HEIs and JLIs, 2013‑22

Note: As of 1 May, each year.

Source: JASSO (2023[17]), Result of International Student Survey in Japan, www.studyinjapan.go.jp/en/statistics/zaiseki/.

International students in Japan are over-represented in the Social Sciences and Humanities

In Japan, most international students in higher education are enrolled in the social sciences, followed by humanities, and engineering (Table 5.5).

Across the OECD, international students are more likely than domestic students (32% vs. 24%) to study Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM subjects), including Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) (Education at a Glance Database, 2020).

Table 5.5. Distribution of international students in higher education institutions in Japan across fields of study, 2014‑22

|

|

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Humanities |

22.9 |

24.8 |

25.2 |

24.2 |

24.0 |

21.6 |

18.3 |

16.0 |

17.0 |

|

Social science |

37.0 |

36.2 |

35.6 |

35.9 |

35.4 |

37.1 |

37.5 |

37.8 |

34.7 |

|

Science |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

2.2 |

2.4 |

|

Engineering |

16.9 |

16.2 |

16.2 |

16.4 |

17.0 |

17.6 |

19.1 |

20.3 |

20.6 |

|

Agriculture |

2.2 |

2.2 |

2.1 |

2.0 |

1.9 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

2.4 |

2.3 |

|

Health care |

2.3 |

2.2 |

2.2 |

2.3 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

2.7 |

3.0 |

3.2 |

|

Home economics |

1.9 |

2.2 |

2.3 |

2.5 |

2.4 |

2.4 |

2.7 |

2.1 |

2.2 |

|

Education |

2.2 |

2.1 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

1.4 |

1.5 |

1.6 |

|

Arts |

3.6 |

3.7 |

4.1 |

4.5 |

4.9 |

5.2 |

6.0 |

6.6 |

6.0 |

|

Others |

9.1 |

8.5 |

8.7 |

8.6 |

8.4 |

8.6 |

8.5 |

8.5 |

10.0 |

Note: The shares across the fields of study add to 100%.

Source: Jassp (2023[17]), Result of International Student Survey in Japan, www.studyinjapan.go.jp/en/statistics/zaiseki/index.html.

How attractive is Japan for international students?

A country’s attractiveness for international students depends on many different criteria: the quality of the educational institutions, the cost of studies, the quality of life, the possibilities to work in the host country after graduation, the recognition of the educational degrees in the country of origin, etc.

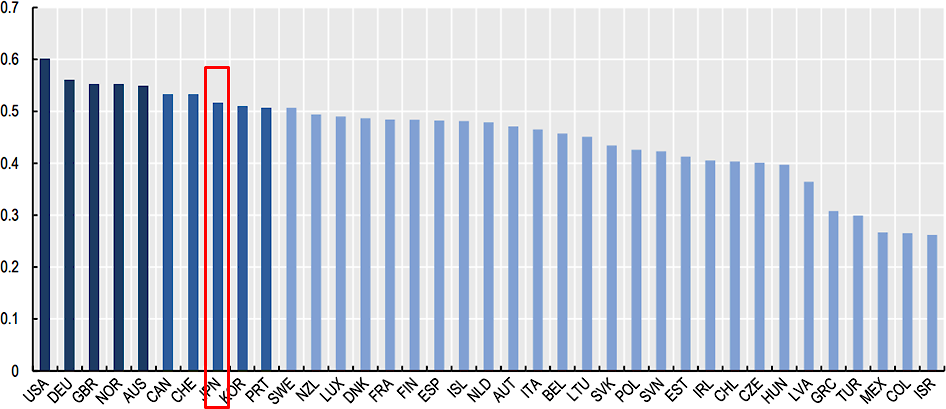

The OECD Indicators of Talent Attractiveness compare countries along seven dimensions of attractiveness for international students, including quality of opportunity, income and tax, future prospects, or skills environment. In the latest edition, Japan ranks 8th out of 38 OECD countries. This section reviews some factors and challenges of Japan’s attractiveness for international students.

Figure 5.11. Attractiveness of OECD countries for potential migrants: University students

Note: Values closer to 1(0) represent higher (lower) attractiveness. The ranking is based on default equal weights across dimensions and does not include the health system performance dimension. Costa Rica is not included in the ranking due to missing data for the visa and admission policy dimension. Top-ten countries are highlighted to facilitate comparison.

Source: OECD (2023[18]), “What is the best country for global talents in the OECD?”.

Migrating to Japan to study

To enrol in higher education in Japan, international students are typically required to submit two test results. The two most referenced tests are the general admission tests known as Examination for Japanese University Admission for International Students (EJU) and the Japanese Language Proficiency Test (JLPT) (see Box 5.2). However, required tests may depend on the origin country and on the educational institution and programme in Japan.

In addition to these two tests, applicants to a higher educational institution in Japan whose country’s secondary education curriculum lasts less than 12 years need to take the “university preparatory course” of Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology to become eligible to apply for university in Japan. In the preparatory course, students study not only the Japanese language but also the basic subjects required for university entrance.

Finally, while most Japanese students take the Unified/Common University Entrance Examination when applying for national universities and some private universities (undergraduate level), most universities do not require international students to take this examination, however, it may be required for some programmes (such as medicine and dentistry).

Box 5.2. General admission and language tests: the EJU and the JLPT

Examination for Japanese University Admission for International Students

The EJU evaluates general ability to study at a Japanese higher educational institution. It tests four broad subjects: Japanese as a Foreign Language, Science (Physics, Chemistry and Biology), Japan and the World, and Mathematics. The examination is available in Japanese or English, but most aspiring international students take the test in Japanese (around 96% in 2019). The EJU does not have a pass/fail mark, but rather provides individuals with a score per subject. Test results remain valid for 2 years. More than 60% of Japanese universities, including most national universities require the submission of EJU scores as part of the application.

Japanese Language Proficiency Test

The JLPT is the most known and most administered test to assess the proficiency of Japanese language learners. It is administered twice a year from inside and outside of Japan and in 2018, the number of applicants to take the JLPT was over 1 million.

The government sponsored JLPT has five levels: N5 (the lowest), N4, N3, N2 and N1 (the highest proficiency level). N2 or above is generally required to enrol in any study programme which is offered at least partly in Japanese. Some institutions accept the scores from the EJU in Japanese as a Foreign Language as proof of Japanese language skills. The JLPT results do not expire or become invalid over time. Learners of Japanese take the JLPT for various reasons. Data from oversea applicants of the December 2018 test round shows that only about 10% took the test because it was required to gain admission into university or graduate schools in Japan.

In addition to the JLPT, there are multiple tests available, testing different skills and levels, administered at different times throughout the year and for varying fees. Japan’s Immigration Service Agency, for example, lists nine tests that can replace the most common JLPT.

Source: Data of the test in 2019 (December), JLPT Japanese-Language Proficiency Test, https://www.jlpt.jp/e/statistics/archive/201902.html; JLPT in Charts, JLPT Japanese-Language Proficiency Test https://www.jlpt.jp/e/statistics/index.html.

The immigration process for international students is simple. Once international students are accepted in a JLI or HEI, the educational institution applies for the Certificate of Eligibility (CoE) to the local Immigration Bureau. When candidates receive the CoE, they may apply for a visa in the country of origin. The process is the same than for high skilled migrants (see also Chapter 4).

Learning Japanese

A main difficulty for international students in Japan is learning the language. This is a main challenge for attractiveness of all non-English speaking countries in the OECD. Learning Japanese was the most reported difficulty before coming to Japan among international students. In 2021, 57% of respondents to JASSO’s annual Survey of Living Conditions of Privately Financed International Students (JASSO, 2021[19]) reported language learning as a main challenge. More international students reported it as a difficulty than “collecting information” (47%) or “preparing funds to study abroad” (41%).

In Japan, JLIs are not considered a higher educational institution. They are accredited by MoJ, after consultation of MEXT. JLIs remain largely independent in terms of structure and teaching content and lack common curricular standards. MoJ conducts inspections of JLIs and there are student attendance requirements. However, there is little oversight regarding the quality of teaching. Most language institutes are private and for-profit entities that recruit prospective students in their country of origin. There are no statistics available on test results of students of JLIs. Nevertheless, at least among international students who graduate from a JLI, 73% continue their studies in Japan (JASSO, 2022[16]).16

Attending a language course prior to study is common in other OECD countries. In fact, international students typically need to demonstrate study language knowledge before enrolment. Examples include the Australian English Language Intensive Courses for Overseas Students (ELICOS) courses or preparatory studies for language learning in Germany for individuals who have not yet attained the required German competence level required at the university.

A difference to the Japanese set-up is that these courses are closely monitored with reporting obligations on outcomes. In Australia providers need to demonstrate that outcomes of participants are comparable to other English language criteria used for admission to tertiary education. Furthermore, minimum requirements relating to content, contact hours and staff‐student ratios are also applied. In Germany, it is mostly the higher education institutions themselves that offer language and preparatory courses of up to two years prior to the start of the programmes (DAAD, 2020[20]).

Japan is currently considering reforming the JLI framework. In December 2022, the Agency for Cultural Affairs presented the draft report of the Expert Committee on Mechanisms for Maintaining and Improving the Quality of Japanese Language Education. The report suggests reforming the certification system for JLIs and introduce national qualifications for Japanese language teachers. If the changes are enacted, JLIs will no longer be approved by notification of the Minister of Justice but will instead be accredited by MEXT based on the quality of the education provided. As an additional step, Japan is introducing a national qualification for JLI teachers to work at certified JLIs. To qualify, candidates must pass a written test on knowledge and skills and undergo teaching practice. According to the suggested changes the national government will be responsible for administering the examinations of teachers.17

The importance of the quality of language teaching has increased over the last decade in Japan. Not only has the number of international students enrolled in JLIs increased, but their composition by country-of-origin countries has also changed. While in 2011, most students (over 80%) in JLIs came from the so-called Kanji zone (China, Korea and Chinese Taipei), in 2019 only 42% of students enrolled in JLIs were from these three countries. As the Kanji zone shares some linguistic characteristics, it is easier for individuals from these countries to learn Japanese.

There are few degrees offered in English

English as the medium of instruction (EMI) in higher education has become a theme of discussion, both in academic literature and the policy sphere. Offering academic degrees fully in English potentially attracts a larger and wider range of international students and contributes to the internationalisation of universities. There are however growing concerns about teaching quality in English courses and perhaps more importantly the impact of English education on the retention rate of international students. While international students may be able to study in English, they will require local language fluency to integrate into the labour market, and in the host country society.

In Japan, English as Medium of Instruction also aims at attracting international students and is part of Universities’ globalisation strategies. However, in 2023, only 9% of programmes are fully in English according to the JASSO listing of programmes open for international students.18 In 2020, only about 6% of universities offered a full degree programme in English, according to the latest government survey among HEI. This share has nevertheless grown over the last decade from just 1% in 2009.

In OECD countries international students are strongly self-select into English-course programmes. In Denmark for example, in 2020, international students accounted for 40% of enrolment in English-language programmes compared to just 2% in programmes taught in Danish. Similarly in Poland, in the academic year 2020/21, foreign students accounted for 65% of students in English-language courses and 4% in Polish ones. Hungary offers higher education programmes in English, French, Hungarian and German. Data on enrolment rates from the 2021/22 winter semester show that only 4% of students studying in Hungarian-language higher education are international students. In contrast, 95% of those studying in German are international students, and about four in five among those in English and French programmes.

Unfortunately, comparable data is not available for Japan. There is no information on the share of international students in undergraduate and graduate degrees who attend English-language degrees. Similarly, there is no information on the share of students in English-language degrees who are international students.

The main concern with EMI is that international students will not be able to integrate into the local labour market. In Japan, this concern is particularly relevant. According to the 2020 round of the “Survey on Recruitment of International Students”, the main challenge for employers in hiring foreigners are inadequate Japanese language skills (43%).

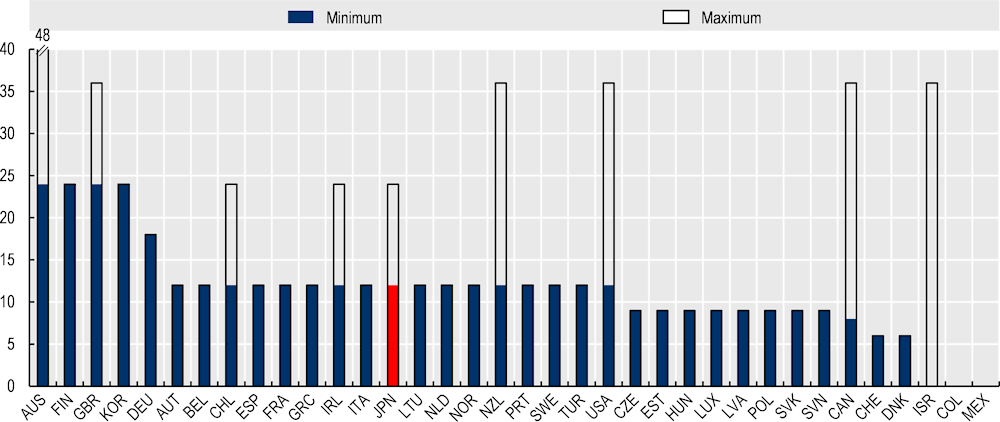

Tuition fees are low, but the cost of living is high

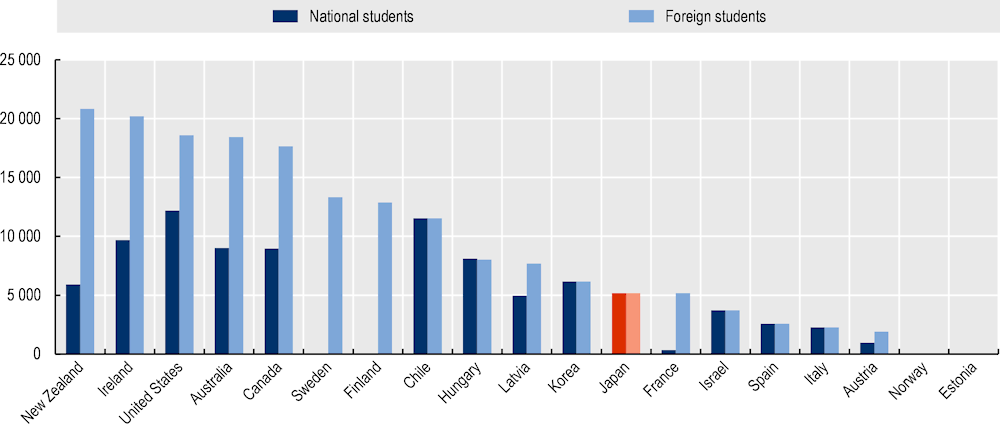

Japan has internationally low tuition fees (Figure 5.12). The role tuition fees play in attracting international students is not clear-cut. Student fees can act as a signal of the quality of education, in particular in those countries with a positive educational reputation. Nevertheless, the low fees act as a support policy for international students.

In Japan, tuition fees are the same for international students and nationals. HEIs in Japan are not allowed to differentiate their tuition fees based on nationality. This contrasts with most OECD countries, which charge higher fees to international students.

Figure 5.12. Japan has internationally low tuition fees for foreign students

Annual average (or most common) tuition fees in equivalent USD converted using PPPs, for full-time students, charged by public tertiary institutions to national and foreign students (ISCED 7), 2019/20

Note: See Annex 3 of Education at a Glance 2021 for notes.

Source: Adjusted from OECD Education at a Glance, 2021.

Despite low tuition fees, the cost of studying in Japan is relatively high due to the high cost of living. According to the latest OECD comparative price levels index, Japan ranks 16 out of 38. In fact, three‑quarters of former students in Japan report the high cost of living was a hardship faced during their studies (Survey of Living Conditions of Privately Financed International Students (JASSO, 2021[19])).

The labour market access during study is generous and many students work

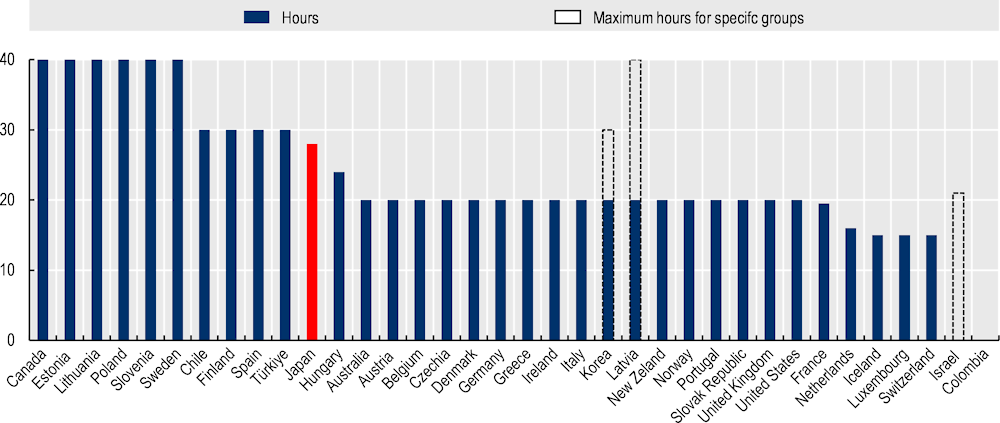

A key policy for international students is the possibility s to work during studies. Most OECD countries offer international students this option to help them defray the costs of their education and to get a first foothold into the labour market. This is also the case in Japan, where international students are allowed to work up to 28 hours per week during term-time and potentially full-time during school holidays. Access to the labour market is not automatic. International students need to apply for a Permission to Engage in Activities other than those Permitted by the SoR. In practice, the process is simple and the rejection rate very low. International students’ access to the labour market compares favourably with other OECD countries (Figure 5.13).

Figure 5.13. Students can work part-time in Japan

Maximum working hours per week allowed in selected OECD countries (during the semester), 2022

Note: The figure includes OECD countries for which data are available. In Australia, international students can work 40 hours per fortnight. In. In Denmark, the limit is 20h/week for BA/MA students and full time for PhD students. In Israel, only international students in High-Tech related fields of study can request part-time employment in relevant companies during their studies. In the United States, employment is only allowed on-campus or in an off-campus worksite affiliated with the institution. In Latvia, the limit is 20h/week for BA students and 40h/week for master’s/PhD students. In Luxembourg, the limit is 10h/week for BA students and 15h/week for master’s/PhD students. In Korea, the limit is 20h/week for bachelor’s students and 30h/week for master’s/PhD students. Canada refers to a temporary measure in place till the end of 2023. The data for Denmark, Portugal and Spain refer to non-EU students, whereas there is no limit on maximum number of working hours alongside studies for EU and domestic students. Estonia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovenia and Sweden set no limits on the maximum hours of working alongside studies.

Source: Adjusted from OECD (2022[15]), International Migration Outlook 2022, https://doi.org/10.1787/30fe16d2-en.

Over half of international students work in Japan but this depends on the type of higher educational institution and has fluctuated over time (Table 5.6). In particular, the share of international students working while studying at university has decreased from 71% in 2017 to 60% in 2021.

Table 5.6. Over half of students work part time during studies

Share of students reporting to work part-time during studies by type of educational institution, 2017, 2019, 2021

|

|

|

2017 |

2019 |

2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Higher educational institutions |

University |

70.9 |

66.4 |

59.7 |

|

Junior college |

87.5 |

86.8 |

84.3 |

|

|

Vocational school |

87.3 |

84.9 |

84.1 |

|

|

Japanese language institutes |

76.4 |

67.5 |

59.2 |

|

Note: Selected categories.

Source: JASSO (2021[19]), Survey of Living Conditions of Privately Financed International Students.

More international students work in Japan than in most other OECD countries. About a third of all students in the EU are employed, with similar levels among foreign-born (34%) and native‑born (35%). Approximately one‑third of international students in the United States work (35%), and in France and the United Kingdom, one‑quarter do so.19 In Australia,20 like in Japan, half of international students were in employment, mostly working part-time. Switzerland and Denmark are the countries with the highest share of international students in employment, approximately 60%.

JLI students since 2010 are considered under the same student visa category (ryūgaku) category as those entering HEIs, while previously they formed a different category semi-student (shūgaku) (Sato, Breaden and Funai, 2020[21]). As a result, students in JLI have the same access to the Japanese labour market as students enrolled in HEIs. Given the lack of oversight of JLIs in terms of quality of language education, there are worries that labour market access is a major pull factor especially for some international students, who can attend a language school and at the same time work up to 28 hours per week. However, despite incomplete data, the evidence shows that most JLI students do go on to HEI.

Policies to attract and retain international students

Policies to attract international students

40 years of International Student Plans

Over the last decades, international student policy has been shaped by several large‑scale plans and initiatives.