Successfully embedding a regional lens in policy making entails articulating the long-term needs and ambitions of Welsh regions and collaborating across different policy areas within the Welsh Government to achieve the desired change. This chapter explores avenues for the Welsh Government to drive these two aspects. The first section discusses how the Welsh Government can build on its existing foresight and futures-thinking knowledge and activities to develop a long-term view of regional development and, from that, weave a strategic thread to guide policies impacting this area. The second section discusses how the Welsh Government can fill a co-ordination gap, adopt a mix of co-ordination mechanisms and foster cross-departmental working to build a truly integrated, cross-sectoral working environment to advance regional development.

Regional Governance and Public Investment in Wales, United Kingdom

2. Pulling the pieces together for regional development

Abstract

Introduction

Advancing the regional lens, introduced in Chapter 1 to complement and guide national and local action, requires a strategic and co-ordinated regional perspective. Regional development policy calls for a long‑term and integrated approach due to the complex interplay and evolving nature of the economic, social and environmental factors that affect regional development outcomes. By adopting a forward-looking approach and integrating activities across policy domains, strategies can be more effectively aligned with the Welsh Government’s ambitions and overarching policy goals, such as the well-being goals set out in the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015. In Wales, the Welsh Government can benefit from charting a course for regional development in collaboration with other regional development actors and unifying the efforts of different parts of the Welsh Government in the chosen direction.

This chapter explores how Wales can “pull the pieces together” for regional development, understanding and expressing long-term needs and ambitions for Welsh regions and working across Welsh Government policy areas to bring about desired change. This chapter discusses the foundations necessary to apply a forward-looking strategic perspective to regional development in Wales. It explores how the Welsh Government can build upon existing groundwork in futures thinking and vision setting to develop a strategic thread for regional development that can guide Welsh Government activities. Finally, it considers how different parts of the Welsh Government can work together in a more integrated way to advance regional development objectives.

Charting a course for regional development in Wales

A long-term perspective for regional development can help the Welsh Government, local authorities and the Corporate Joint Committees (CJCs) make the most of the regional lens. The Welsh Government already has building blocks in place for setting a long-term regional view, including some inhouse capacity for futures thinking (including foresight and vision setting) and the seeds of a vision from an exercise conducted with the OECD in 2022‑23. Legislation, such as the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act and key statements of Government policy aims and objectives such as the Programme for Government, the Regional Economic Frameworks and Framework for Regional Investment in Wales, provides a basis to look ahead towards the medium and long terms. The Welsh Government’s challenge is to continue strengthening its long-term perspective, translating it into a strategic thread that can guide cross-sector coherence and policy action. A strategic thread refers to a set of long-term, integrated regional development objectives distilled from existing sectoral strategies and plans that guide sectoral policies to contribute to regional development. This section presents those building blocks for a long-term perspective – foresight and vision setting – and considers how the Welsh Government can build upon them to strengthen its strategic planning.

Futures thinking, foresight and seeds of a vision provide foundations for a long-term view of regional development in Wales

Being forward-thinking in regional development starts with a clear idea of what a region’s future may hold and what stakeholders at all levels would like it to hold. The OECD identifies futures thinking and foresight activities as a tool in the strategic planning cycle for governments to develop policies, address complex policy problems, prepare for long-term changes and deal with unexpected developments, shocks and uncertainty (OECD, 2021[1]). The OECD Recommendation of the Council on Regional Development Policy also acknowledges the importance of anticipating change and preparing regions for the future as a step toward building their resilience (OECD, 2023[2]). Setting a vision helps stakeholders understand what futures they would like to work towards. Setting such a vision through a collaborative and participatory process – bringing together experts, stakeholders, government and non-government participants – helps reflect a broader group’s unique perspectives and needs. A shared vision-setting process also generates shared understanding and buy-in to the vision and subsequent objectives and policies, increasing the possibility that objectives are achieved. The Welsh Government has already been engaging in foresight and future-thinking activities, supported by the Sustainable Futures Division that oversees the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act and the vision-setting exercise conducted with the OECD.

A common reflection heard among regional development stakeholders in Wales is the need for a long-term vision (ten or more years) that can help guide strategy and objective setting, priority setting and policy design. Regional development stakeholders and actors from the public, private and third sectors participating in interviews for the 2020 OECD report The Future of Regional Development and Public Investment in Wales and this OECD project consistently identify the lack of a clearly communicated vision for where Wales wants to go as a nation in the regional development space, what it wants to look like as a territory and what it will take to get there as an obstacle to regional development in Wales (OECD, 2020[3]; OECD, 2023[4])

Through an online survey and a series of workshops in 2022-23, the Welsh Government and the OECD began to establish the seeds for a vision for Wales in 2037 (further details in Annex A). The work involved a broad group of representatives from the Welsh Government, local authorities and public, private and third sector stakeholders. Together, these participants began to express how they saw Wales evolving in 15 years and where they would like the nation to arrive – economically, socially and culturally – at the end of that period. The result was the seeds for a vision for development centring on maximising people’s well‑being while also ensuring economic growth: a nation with a “stronger economy, green growth, that generates greater wellbeing, has a territory that is attractive to young people, and that is advanced in technology and innovation, while also maintaining its distinctive culture” (Figure 2.1) (OECD, 2023[5]). These elements align strongly with the aspirations that underpin the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015, which focuses on well-being.

Equipped with the seeds of a vision for regional development, the next step would be for the Welsh Government to work together across sectors and with different government levels to further refine the vision and translate it into a regional development strategy, identifying priority areas for growth that are supported by realistic, short-, medium- and long-term actions.

There is an appetite in Wales, and within the Welsh Government, to reinforce futures thinking and foresight activities and to improve their application in regional development policy making. Efforts to do so can build upon existing capacity. The Sustainable Futures Division, which has responsibility for the sustainable development agenda and associated Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act and the statutory Future Trends Report, has led the charge to improve the use of foresight tools across the Welsh Government, most recently piloting the application of foresight exercises on policy projects in several areas of the Welsh Government. Other pockets of Welsh Government staff, like the Strategic Evidence Unit within the Climate Change and Rural Affairs Group, already apply foresight skills in their work (Welsh Government, 2024[6]).

Despite the use of futures foresight practices within the Welsh Government and among other public and third sector organisations, advancing such activities faces organisational and capacity challenges (Welsh Government, 2024[7]). A Welsh Government review of its use of futures thinking and foresight identified a set of barriers that include limited cross-sector working, limited resources, futures literacy gaps and limited “buy-in” by the political level (Welsh Government, 2024[7]). Futures work is extremely valuable for strategy setting and building resilience by helping policy makers prepare for and manage risks and opportunities. However, it is a difficult process, requiring human resources with the necessary skills and time to generate and apply insights from such activities. Simply using foresight tools is insufficient to deliver a long-term vision or strategy and relevant actions for regional development (Welsh Government, 2024[7]).

Figure 2.1. Seeds of a vision for “Wales in 2037”

Source: OECD (2023[5]), Envisioning Wales in 2037: Findings from multi‑stakeholder workshops and a citizen survey, https://www.oecd.org/regional/governance/Wales_vision_brochure.pdf; OECD elaboration based on citizen survey and stakeholder workshop inputs.

Moving forward, the Welsh Government could mobilise existing inhouse capacity to build and apply futures thinking practices to regional development throughout the organisation. To do so, it can enlist the help of the current Sustainable Futures Unit and tap into the existing knowledge in the Strategic Evidence Unit in the Climate change and Rural Affairs Group within the government. International experience covering broader areas also provides different models for embedding futures thinking, foresight and vision setting in government practices, which can help drive regional development. As the most advanced example, Finland has institutionalised strategic foresight through departments, committees and government networks with specific mandates and responsibilities related to strategic foresight. Ireland is undertaking a project to develop a model and tools for the whole public administration to build foresight capacity. For its part, New Zealand created a simple instrument – a long-term insights briefing – to encourage line ministries to look at future challenges (Box 2.1).

Ultimately, the Welsh Government can more actively apply its futures thinking, foresight and vision-setting work to regional development, helping it identify and prioritise regional development objectives. By systematically exploring possible future scenarios and their implications, governments can identify long‑term objectives and prioritise actions in a way that is adaptive and resilient to change. Governments can make more informed decisions by anticipating emerging trends, challenges and opportunities. A desired future, expressed through a regional development vision developed with stakeholders, provides direction to policy making and is a beacon towards which the government can orient its activities in this area. Building on its existing foundations in place for futures thinking, foresight and vision setting, the Welsh Government can translate these into a single strategic thread for regional development across Welsh Government departments, the focus of the next section.

Box 2.1. Examples of building long-term thinking in public administration: Finland, Ireland and New Zealand

Finland: Anticipatory innovation governance

Finland has one of the world’s most advanced governance and strategic foresight systems. The government has established various institutions with formal and informal roles fostering “anticipatory innovation governance”, i.e. to build the capacity of the public administration to actively explore possibilities, experiment and continuously learn as part of a broader governance system. Sitra, an innovation fund which reports to the Finnish parliament, has been conducting foresight studies of Finland and spearheading the use of foresight and futures tools in the Finnish public sector for decades. The Committee for the Future, established in 1993 by the parliament, is a key forum for raising awareness and discussing long-term challenges related to futures, science and technology policies in Finland. The Prime Minister’s Office houses the Strategic Department, which includes the co-ordinating function for national strategic foresight. The National Foresight Network and community events like Foresight Fridays, led once a month by the Prime Minister’s Office, promote knowledge-sharing across public entities. In addition to the national-level foresight work, regions and municipal associations have their own foresight practices and agencies (like Business Finland, Tekes) that conduct their own technology assessment and strategic foresight exercises.

Ireland: Developing strategic foresight capacity

Building on Our Public Service 2020 (OPS2020), the Irish government is embarking on OPS2030, a new framework for development and innovation in Ireland’s public service. The goal for OPS2030 is to ensure that Ireland’s public service is fit-for-purpose to 2030 and beyond. In this context, the government of Ireland is upgrading policy development and strategic foresight, spanning the whole public service. This upgrade aims to increase the ability of the public service to address policy in complex areas, such as climate change, digitalisation, demographic change and long-term healthcare and to contribute to future-proofing such policies. Moreover, it aims to develop a model of strategic foresight and anticipation to steward public policies in the future.

New Zealand: Long-term insights briefings

New Zealand’s Public Service Act 2020 requires chief executives of government departments, independently from ministers, to produce a long-term insights briefing (LTIB) at least once every three years. The LTIB should explore future trends, risks and opportunities and is expected to provide information and impartial analysis, as well as policy options for responding to risks and seizing opportunities. LTIB development is an eight-step process that engages citizens on the topic at hand and the draft briefing through public consultation. The first LTIB was presented to a parliamentary select committee in mid-2022 and subsequently published.

Prior to the Public Service Act 2020, New Zealand’s senior policy community had discussed the challenges of building long-term issues into policy formulation, including the relative dearth of foresight capacity across the public service. It held workshops on a future policy heatmap and policy stewardship. While there is no associated programme to build capability in strategic foresight, the LTIB requirement process may catalyse demand for increasing strategic foresight capabilities.

Source: OECD (2022[8]), Anticipatory Innovation Governance Model in Finland: Towards a New Way of Governing, https://doi.org/10.1787/a31e7a9a-en; OECD (2021[9]), Towards a Strategic Foresight System in Ireland, https://oecd-opsi.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Strategic-Foresight-in-Ireland.pdf; OECD (2023[10]), OECD Public Governance Reviews: Czech Republic: Towards a More Modern and Effective Public Administration, https://doi.org/10.1787/41fd9e5c-en. Government of New Zealand (2023[11]), Long-term Insights Briefings, https://www.publicservice.govt.nz/publications/long-term-insights-briefings/.

A strategic thread can unify regional development efforts towards shared objectives

The OECD 2020 report highlighted the fragmented strategic and policy backdrop for regional development in Wales. It drew attention to the fact that a fragmented policy approach to regional development – one that depends on individual sector policies and their implementation at the regional level – can produce limited results (OECD, 2020[3]). Fragmented policy making has been a recognised problem since the earliest days of devolved government in Wales and it remains a challenge (Wales Centre for Public Policy, 2021[12]). A fragmented and siloed approach to policy making and implementation makes it difficult for governments to define and agree on clear, long-term regional development objectives. In Wales, the challenge is not restricted to regional development policy, however, but spans a range of policy areas, such as poverty (Auditor General for Wales, 2022[13]) and the well-being of young people (Wales Audit Office, 2019[14]). Fragmentation and silos were also identified by the Future Generations Commissioner for Wales as an obstacle to implementing the cross-cutting Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act (Future Generations Commissioner for Wales, 2020[15]).

While a single, integrated (i.e. cross-sector) national-level strategy for regional development is ultimately a political decision, ensuring high-level strategic guidance remains of fundamental importance. The 2020 OECD report noted the significant value of having a single national-level, long-term regional development strategy to guide national and subnational actors in their regional development activities. Such an approach – driven by broad and strong political support – may be ideal to meet regional development objectives in a place like Wales, where there are multiple (generally sector-driven) strategic documents and multiple sectoral policies to support them. While it may be the best option, a single regional development strategy backed by strong political support is not the only way to promote strategic coherence for regional development across the Welsh Government. Even without it, strategic direction can still take shape by assembling relevant high-level objectives in other government strategies. This strategic thread can provide some of the same benefits as a single strategy, helping regional development actors optimise their use of resources, co-ordinate efforts towards objectives and ultimately produce better policy outcomes (OECD, 2020[3]).

Within a fragmented strategic landscape, Welsh Government staff turn to three main sources for strategic guidance for regional development: the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act, the Programme for Government and the Framework for Regional Investment in Wales. None of these, however, aim to provide what a single integrated strategic thread for regional development would contribute: a fixed and apolitical beacon that serves to translate ambitions into action, guiding planning and delivery related to regional development across the Welsh Government.

The Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015. This act provides the statutory foundation for all policy action in Wales, including regional development. It aims to help Wales better address critical challenges (e.g. climate change, poverty, health inequalities, jobs and growth) and promote long-term thinking when making policy decisions. It established the legal requirement for 48 public bodies to contribute to the act’s seven well-being goals.1 It also created 13 Public Service Boards that produce well-being plans for their localities, describing how they will comply with the act’s goals, and a national-level Future Generations Commissioner for Wales to support, monitor and review implementation of the act (Future Generations Commissioner for Wales, 2015, p. Parts 3 and 4[16]; OECD, 2020[3]).

With well-being goals to guide objective setting throughout the public sector, it is understandable that Welsh Government staff would see the act as a potential source of strategic guidance for regional development (OECD, 2023[4]). As its name highlights, however, the act is a written law, not a strategy. The challenge faced by the act – one recognised by the previous Future Generations Commissioner for Wales (2020[15]) – is how to operationalise its aspirational goals. A strategic framework for regional development can help bridge this gap, translating the aspirations into action.

The Programme for Government. In Wales, the Programme for Government sets out the political priorities for a fixed term of government (currently 2021-26). It consists of 115 commitments, falling under 10 overarching well-being objectives2 selected by the Welsh Government to make the greatest contribution to the 7 national well-being goals enshrined in the Well-being of Futures Generation (Wales) Act (Welsh Government, 2021[17]).

Some Welsh Government staff participating in this project noted that they sometimes turned to the priorities in the Programme for Government as a potential source of strategic direction for regional development, even though its aim is very different. Their comments suggest that Welsh Government staff may be – perhaps unrealistically – expecting what is essentially an expression of a political manifesto to have the characteristics of a strategy (OECD, 2023[4]). For example, when discussing the Welsh Government’s objectives and priorities during OECD interviews, some Welsh Government staff perceived a mismatch between the Programme for Government’s commitments and the resources available for its delivery – including the time of staff and others who would contribute to its realisation, like local authorities.

The 2020 Framework for Regional Investment in Wales. Sitting below the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act and the Programme for Government, it is currently the most comprehensive framework document to support regional development in Wales. With its four overarching investment priorities – i) more productive and competitive businesses; ii) reducing economic inequality; iii) transitioning to a zero-carbon economy; iv) ensuring healthier, fairer, more sustainable communities – the Welsh Government has taken a significant step, following consultation with local authorities, other regional development actors and the public, to guide public investment initiatives at the national, regional and local levels. The advantage of the four priorities in the framework is their relevance to most, if not all, sector policies. They are also sufficiently broad to resonate with the objectives of different Welsh Government departments and limit dissonance between higher-level aims and on-the-ground policy design and implementation.

Conceived as a model for replacement European Union (EU) funds, the framework, while supporting regional development, is not a long-term regional development strategy. First, it explicitly focuses on public investment, which is an important driver of regional development but only part of the regional development picture. Second, the framework does not fully apply the regional lens (Chapter 1). While the framework synthesises national-level sectoral objectives and priorities relevant to regional development (e.g. supporting job creation, workforce upskilling, mobility, research and development, housing, transport), the regional perspective could be strengthened by specifying how nationwide priorities and development needs manifest within regions. The framework and its supporting socio-economic analysis look at national sectoral development needs and data (e.g. it analyses the disruption of trade for business, the need to enhance mobility). It could take the application of the regional lens one step further and consider how sector policies and activities advance both national and regional-level development objectives, taking advantage of synergies between them.

One good practice is that the Framework for Regional Investment is supplemented by the Regional Economic Frameworks (REFs), which further detail the needs and opportunities of individual regions. However, the REFs are not a substitute for an overall strategic thread for regional development in national-level policy making. In addition, as analysed in the OECD (OECD, 2020[3]) report, there are some shortcomings in developing these REFs (e.g. strict focus on economy and productivity, limited consideration of the links with existing regional plans such as the City and Growth Deals, questions regarding its necessity).

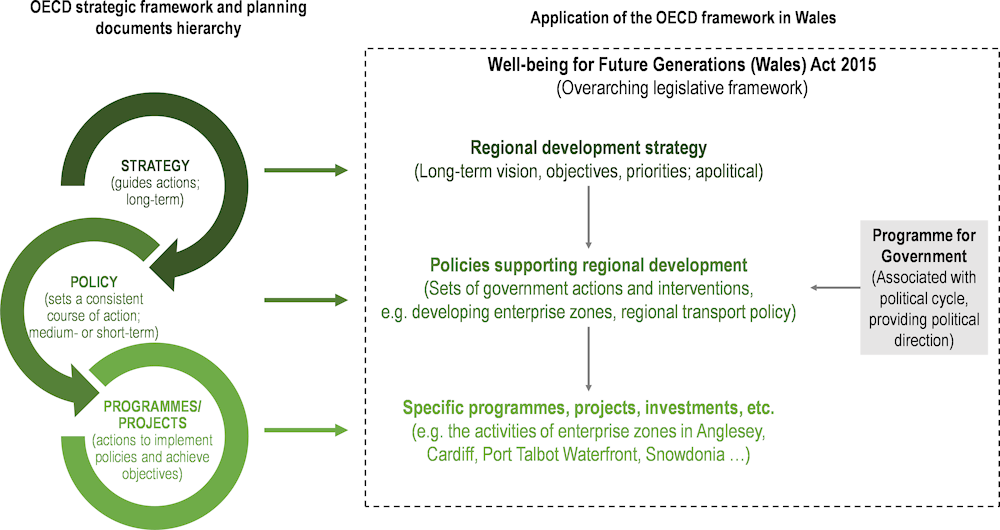

Figure 2.2 shows how these three de facto sources of strategic direction for regional development map onto the OECD hierarchy of strategic framework and planning documents. The hierarchy shows how strategy cascades throughout government activities: first informing policy, which then gives rise to specific (sector or cross-sector) programmes and projects. In Wales, the Well-being for Future Generations (Wales) Act sits above the other levels of the hierarchy, providing an overarching framework for government strategies, policies, programmes and projects. However, there is still a role for regional development strategy – one single strategy or a strategic thread weaving together other sectoral strategies – to connect the high-level act to the Welsh Government’s regional development activities. Regional development strategy in Wales can serve as a tool to operationalise this act. Regardless of changing political priorities, the strategy becomes a long-term and stable beacon. This strategy can guide policies that support regional development. While Wales has no single regional development policy (OECD, 2020[3]), it has many policies that are of great relevance to regional development, such as developing enterprise zones in Wales and transport policies that involve interventions at the regional level. The Programme for Government also feeds into the policy that supports regional development in Wales, linking political priorities with policy objectives. Finally, specific programmes, projects and investments are developed to deliver the policies, such as the operations of specific enterprise zones or projects to construct and upgrade regional transport infrastructure. Clearly defining its own strategic hierarchy, understanding the purpose of each part of the hierarchy and using each as intended form a critical step for the Welsh Government to build the strategic thread for regional development.

Figure 2.2. Applying the OECD strategic framework and planning documents hierarchy in Wales

Note: Long-term generally is defined as ten years or more; medium-term five to seven years; short-term zero to five years.

In the absence of a more complete and integrated strategy for regional development and because of policy fragmentation, cross-government strategic documents that are relevant to regional development have proliferated across the Welsh Government. In 2022, the OECD identified over 70 Welsh Government strategic documents in force, ranging from general Welsh Government planning documents to those that only focused on a specific region or sector. Many lacked ties to other relevant strategic documents and to the Programme for Government and Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act (Box 2.2). When not co-ordinated in their design and implementation, numerous strategies create complexity and potential for misalignment. At best, it means that the government is not taking full advantage of complementarities among policies, which can affect optimising resources; at worst, it can result in policies working at cross-purposes.

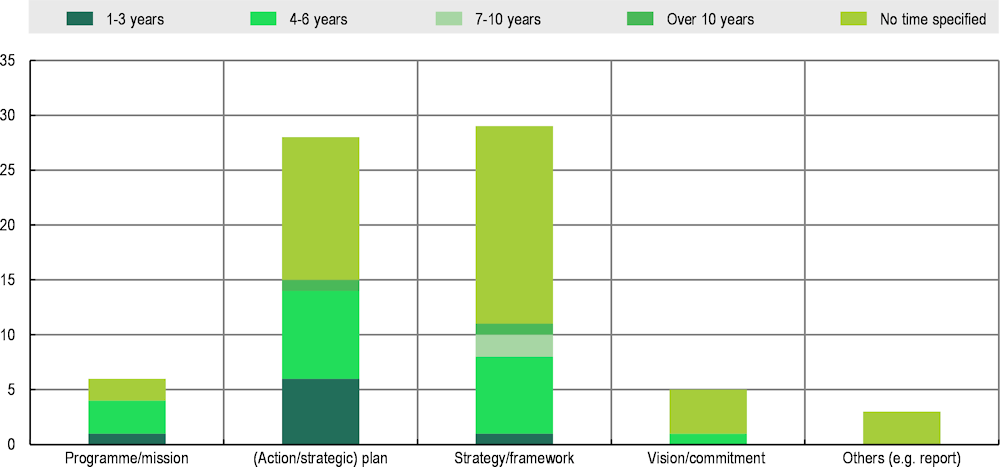

Box 2.2. A profusion of strategic documents across the Welsh Government

A challenge confronting the Welsh Government and staff responsible for regional development policy and programme implementation is the proliferation of strategic documents and planning instruments that vary significantly in scope, focus and form (Figure 2.3). They include strategic plans, vision statements, mission documents and frameworks. However, each of them sets out, at a minimum, the broad contours of an ambition for Wales and a pathway towards this ambition. In brief, the strategic landscape for regional development in Wales compounds the challenges arising from fragmentation in Wales, including the thread of a lack of policy coherence (OECD, 2020[3]).

Figure 2.3. Number and type of national strategic documents in Wales and their time horizons

Note: National strategic document refers to documents developed at the Welsh Government level, regardless of whether the content applies to the whole nation or only certain regions or territories. Progress reports are not included. The seven strategic plans for seven different enterprise zones in Wales are counted as one document; the four REFs for the region are counted as one document.

Source: Calculation based on strategy documents provided by the Welsh Government in 2022. More information on the methodology can be found in Annex A.

Welsh Government staff have also observed that the coherence among strategies and between strategies and the Programme for Government or the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act could be clearer. In some cases, multiple strategic documents in a single policy area threaten to overlap and do not always draw strong connections between them. For example, five strategic documents in the area of transport planning were released between 2016 and 2021: the Active Travel Action Plan for Wales (Welsh Government, 2016[18]), the Electric Vehicle Charging Strategy for Wales (Welsh Government, 2021[19]), North East Wales Metro: Moving North Wales Forward (Welsh Government, 2017[20]), the 5-point Plan to Support Welsh Ferry Ports (Welsh Government, 2021[21]) and, finally, Llwybr Newydd: The Wales Transport Strategy 2021 (Welsh Government, 2021[22]). Approximately a quarter of the planning instruments analysed by the OECD were linked3 to the Programme for Government, an expression of the political ambitions of the Welsh Government. A smaller number of planning instruments (15) explicitly outlined how they contribute to specific objectives of the Programme for Government. For example, the Diversity and Inclusion Strategy for Public Appointments in Wales (2020-23) sets forth two core work streams4 through which it aligns with the Programme for Government’s diversity and inclusion objective. Only 25 of the documents explicitly indicated which Well-being for Future Generations (Wales) Act goals they contribute.

Creating a unified strategic document for regional development - an alternative to a single regional development strategy, presented below – could identify opportunities to simplify, rationalise and/or improve the connections with other parts of the Welsh Government’s strategic landscape. In general, however, strategies could follow certain good practices to better support effective implementation. These include detailing delivery time scales and specifying if and how stakeholder consultation on the strategy and its implementation would be carried out. To ensure that strategies benefit from the most constructive and pertinent stakeholder feedback, it would be beneficial to specify who to consult, at what stage and with which mechanisms. Also, focusing on realistic outcome indicators, more than monitoring indicators, could provide a clearer picture of the broader changes resulting from policy interventions supporting regional development. Moreover, defining measurable and realistic targets in more planning instruments would help in measuring progress and gauging impact (currently, under a quarter of the planning instruments featured targets that matched the indicators and an even smaller number systematically included targets for all indicators).

A good practice example of monitoring and evaluation in Wales is outlined in the Strategic Equality Plan 2020 to 2024. It combines process indicators (e.g. “using the Commercial and Procurement Skills Capability Programme to address the gender imbalance within procurement”) with outcome indicators (e.g. “an increase in the number of women being trained as procurement professionals in Wales, with the long-term aim of gender equalisation”). Each indicator also includes achievement deadlines and yardsticks for measuring progress (e.g. “monitor the gender balance through the uptake of qualifications and measure against the baseline”).

Source: Analysis of Welsh Government strategic documents.

The proliferation of strategic documents – coupled with the lack of a strategic thread for regional development to ensure coherence – makes it difficult to direct financial and human resources to areas of first concern, like the just transition to net zero or opportunities for youth. Without ensuring that a few key strategic priorities for regional development permeate throughout the Welsh Government and frame decision-making governmentwide, the Welsh Government is de facto delegating priority setting for regional development to individual teams. With different parts of the Welsh Government prioritising independently, the result is a proliferation of priorities. Stakeholders perceived that the Welsh Government would benefit from a clearer and cross-government view of regional development priorities, which would help it to make more effective trade-offs in budget and investment-funding allocation (OECD, 2023[4]) and support staff to focus their work on areas of highest priority.

A single strategic thread for regional development – presented in a unified strategic document – can help the different parts of the Welsh Government and different regional development actors work together more effectively. The guidance provided by this strategic thread can help all actors – different government sectors, regional-level institutions, local authorities, institutions of higher and further education, private and third sectors, civil society, etc. – know in which direction their policies and activities should go in order to: support achieving a national or regional vision; help meet large societal goals and manage societal challenges such as climate and demographic change; or even guide fundamental objectives in healthcare, education or social services. Barring an integrated regional development policy for Wales, ensuring that this strategic guidance exists can help coalesce individual sector strategies and policies to build greater coherence and take advantage of complementarities.

Views shared by Welsh Government staff and stakeholders suggest that addressing the issue of fragmentation and silos would help make the Welsh Government more effective. The government is aware of the obstacles that fragmentation and silos represent, and several practical activities could help it begin to overcome these, starting with mapping and streamlining strategies supporting regional development and better defining and focusing on priorities. These activities are discussed in the subsections that follow.

Weaving a strategic thread for regional development across the Welsh Government

A unified strategic document for regional development can create a “strategic perimeter” that would help policy teams prioritise and help the Welsh Government allocate resources for regional development. Mapping diverse strategies relevant to regional development is the first step to finding a strategic thread that weaves them together.

The mapping can aim to identify overlaps, synergies and trade-offs among strategies. The OECD analysis provides a foundation, having already identified strategic documents for regional development across the Welsh Government. With a birds-eye view of the current strategic landscape for regional development, the Welsh Government can consider how to manage the overlaps, synergies and trade-offs identified during the mapping. It can take inspiration from experience in Piedmont, Italy (Box 2.3) when it considers how to weave the different strategic threads together, creating a unified strategic document to help teams prioritise and help the Welsh Government allocate resources for regional development. Such a document makes explicit the links, synergies and even trade-offs between relevant Welsh Government strategies. Instead of sifting through multiple strategic documents for direction, Welsh Government teams can refer to a single integrated document for regional policy that clearly illustrates the thread from the high-level transversal documents (which set the legislative requirements and express the government’s overarching political priorities) and a vision for regional development.

Box 2.3. Weaving together strategic threads in Piedmont, Italy

The Northern Italian region of Piedmont uses a Unitary Strategy Document (Documento Strategico Unitario, DSU) to link multiple EU, national and regional strategic initiatives. The DSU defines the priority lines of intervention for the development of Piedmont and creates a “strategic perimeter” to ensure the best use of resources. It serves as a “bible” for regional development decision making, guiding policy makers in each strategic programming sector. While European policy is a strong anchor in the DSU, the document can still serve as an inspiration for non-EU governments. Its relevance comes from the fact that it weaves together strategic threads across the regional administration and from different levels. The current DSU, aligned with the 2021-27 EU programming period, outlines the region’s development ambitions, the different strategic threads and how different tools can help achieve the five Cohesion Policy priority objectives. The document weaves in different regional strategies – such as the Regional Sustainable Development Strategy, the regional Smart Specialisation Strategy (RIS3) and the regional Smart Mobility Plan – describing how regional objectives are aligned with and embedded in national, European and international policy and development visions.

Piedmont’s goal is to create a true unitary document that takes advantage of synergies and allows for prioritisation. In tying together these different strategies, the DSU seeks to make the best use of the resources available to the region, maximising efficiencies and minimising the trade-offs between policy objectives and instruments. To this end, the DSU maps objectives across different strategic documents, identifying areas of alignment. In this way, the DSU helps to drive coherence and consistency across the actions underway to deliver strategic objectives.

The region of Piedmont consulted broadly with stakeholders to develop the current edition of the DSU. It started with a month-long “Piedmont Heart of Europe – Let’s shape the future” roadshow, involving over 2 500 stakeholders. Piedmont paid particular attention to youth, organising a special event with them that included a digital brainstorming marathon. Piedmont also used more basic engagement techniques, such as collecting written comments on the DSU via a dedicated website (OECD, 2021[23]).

Critical to the success of the DSU was leadership and a strong political mandate. A small committee became the plan’s main architect; it included Piedmont’s three managing authorities. While representatives from the political level were primary drafters of the most recent DSU, they provided a strong political mandate for the work of the plan’s architects. A technical group was then charged with the delivery of the DSU.

Source: OECD (2023[24]), “Master class with the Welsh Government and Piedmont, Italy”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris; Regione Piemonte (2020[25]), Documento Strategico Unitario, https://www.regione.piemonte.it/web/sites/default/files/media/documenti/2021-09/DSU%20STRADEF%209%20luglio%202021.pdf; OECD (2021[23]), Regional Innovation in Piedmont, Italy: From Innovation Environment to Innovation Ecosystem, https://doi.org/10.1787/7df50d82-en.

Where conflicts or overlaps exist, the Welsh Government can also consider streamlining the different strategic threads by encouraging owners of strategies with significant overlap to collaborate on a single shared framework strategy instead of maintaining separate ones. Such a strategy could then be supported with more tailored policies. This streamlining step may also be a good time to ensure that strategies are coherent and consistent with foundational legislation, such as the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act.

Going forward, providing additional structure can keep strategies that have an impact on regional development from proliferating in an uncoordinated way. The Welsh Government could begin to optimise its strategic planning system for regional development by defining different types of documents (i.e. strategies, policies, policy plans, action plans, programmes), when they should be developed, which type should be developed, a development methodology (planning procedure), structures (basic elements to be included in different types of documents) and the hierarchy or relationship among the different types of documents. A well-defined relationship among these strategic documents is particularly important for ensuring that regional development priorities can be established, policies are well-targeted to objectives, plans are coherent and aims are deliverable. Ultimately, this hierarchy can form the basis of guidance for the creation of strategic documents that Welsh Government staff can consult before creating a new strategic document to make sure that documents show good practice – they are the appropriate type of document, they have clear ties to overarching strategic documents and they are actionable.

The strategic thread must extend to the regions themselves. Piedmont created its Unitary Strategy Document for a single region but Wales must consider its four economic/CJC regions. Therefore, creating a unified strategic thread for regional development in Wales entails uncovering overarching goals and relating these to the unique needs and opportunities of each region. Examples from Austria, Germany and Norway (Box 2.4) underscore the importance of working closely with regions to understand and make explicit the connections between umbrella objectives and regional ambitions.

Box 2.4. Regional development strategy design in Austria, Germany and Norway

In Austria, Germany and Norway, stakeholder engagement, foresight and futures thinking set the stage for a regional development strategy that is responsive to regional needs. In Austria, the new regional strategy was developed based on stakeholder dialogue focusing on how to respond to multiple crises and strengthen resilience through enhancing the quality of life and service provision in regions. In Germany, the recent reform recognises that structurally weak regions face significant challenges in adapting to climate transition and the goals of climate neutrality, energy crisis and demographic trends. In Norway, the white paper on regional policy reflects the role of regions and the challenges they face (especially structurally weaker ones) in a time of major global pressures.

Austria: A new strategy for regions with a stronger focus on rural areas and soft measures

In 2021-22, the Austrian Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, Regions and Water Management launched the My Region initiative using policy analyses and a series of regional and local dialogues to design its regional strategy. Specific topics discussed included regional innovation capacity, regional food industry and local supply chains, and regional co-operation. These analyses and discussions led to a new government strategy for regions: My Region, Our Way: Home, Future, Living Space. The strategy targets four key areas:

1. Designing living spaces sustainably: reducing land use and protecting soil, and promoting lively town centres.

2. Making living spaces attractive: ensuring that essential goods and public services (e.g. food and drinking water, childcare, education, cultural programmes, healthcare, climate-friendly mobility) are available and accessible.

3. Making living spaces efficient: strengthening regional economic and innovation capacity.

4. A cross-sectional topic: strengthening regional co-operation.

Many “soft measures” were designed to support these four areas. For example, to reduce land use and protect soil, the focus was on creating awareness and generating knowledge, including design, education and training measures for soil protection, as well as supporting relevant innovation and research. One initiative to secure regional public services is to strengthen and promote voluntary work for social services in rural areas. To strengthen regional innovation capacity, action is undertaken to support employment opportunities for highly qualified women in rural areas.

Germany: A paradigm shift in regional policy

In 2023, the Joint Task for the Improvement of the Regional Economic Structure (GRW) reformed its regional policy framework and identified a new objective for regional development: to accelerate the transition towards a climate-neutral and sustainable economy, in addition to equalising locational disadvantages, creating and securing employment and increasing growth and prosperity. Following these objectives, the GRW interventions strengthened the focus on endogenous regional development. It has historically supported business with “inter-regional exports” and now support is also provided to firms that are primarily active within the region in order to strengthen regional value-added chains in structurally weak regions. It also targets investments in activities and projects that can lower carbon dioxide emissions by at least 20% or those that achieve a higher-than-national-average standard in terms of environmental protection or energy efficiency.

Norway: Regional policy in a time of global pressures

In June 2023, Norway launched a white paper titled “A good life in all parts of Norway – District policy for the future”, which links the role of regional (district) policy to building trust, security and cohesion in a time of major global pressures (migration technological change, Russia’s large-scale aggression in Ukraine). The key objectives include:

Ensuring that people have access to work, housing and good services close to where they live.

Increased roles and responsibilities at the local level.

Increasing population in specific district municipalities.

A “centrality index” is used to measure geographical disadvantages in the country. Other new initiatives include co-creation of welfare service solutions, greater co-operation among regional actors in service delivery, access to housing, improved transport accessibility (especially for northern and coastal communities), the distribution of public employment across the country and adapting land use policy to local conditions.

Source: Bachtler, J. and R. Downes (2023[26]), Rethinking Regional Transformation: The State of Regional Policy in Europe, https://eprc-strath.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Rethinking-Regional-Transformation-EoRPA-report-23_1-ISBN.pdf.

With a unified strategic document for regional development in place, the Welsh Government can shift to policy delivery. Cross-cutting strategic objectives will be almost impossible to achieve without strong co‑ordination across policy areas. In Wales, this may include the formation of a dedicated team tasked with overseeing and co-ordinating the delivery of strategic objectives. Co-ordination – and the formation of such a team – are discussed in the next section.

Making sure everyone moves in the same direction

Addressing fragmentation and silos requires not only an agreed-upon vision and a set of common high‑level objectives – discussed in the previous section – but also multi-level governance arrangements that ensure the various actors across the administration and at different levels of government advance in unison. This section explores three avenues to promote a more co-ordinated approach for designing and implementing regional development policy in Wales. This includes having a team with a clear mandate to co-ordinate regional development activities, strengthening and diversifying co-ordination mechanisms for regional development and fostering co-ordination and collaboration across teams and departments in the Welsh Government, as well as with other relevant actors, like local authorities. Together, these avenues create an enabling environment for integrated regional development policy making and delivery.

Filling a co-ordination gap for regional development

No single entity in the Welsh Government has a clear mandate to co-ordinate strategy, policies or programming relevant to regional development. As highlighted in Chapter 1, the Welsh Government’s Welsh European Funding Office (WEFO) was responsible for overseeing European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) and European Social Fund (ESF) programming and funds management, serving as the fund co-ordinator and also as the implicit regional development co-ordinator. It was not aligned to any sector policy or specific ministerial agenda. With the advent of Brexit, the UK Government’s introduction of the Shared Prosperity Fund (SPF) and the closing of the 2014-20 EU programming period at the end of 2023, this co-ordination structure has dissipated. This leaves Wales without the built-in common, strategic regional development thread and resources that the European funds created across policy areas, as well as the processes that provided rigour to planning, implementation and monitoring and evaluation for regional development. Currently, many regional development activities are conducted by multiple teams (e.g. Economic Policy, Strategy and Regulation, Regional Officers, Operational Delivery, Business and Entrepreneurship, Innovation, Foundational Economy and Industrial Transformation, Borders) in the Economy, Treasury and Constitution (ETC) Group. At the same time, most policy sectors have some regional-level activity associated with their mandate. In addition to national-level line ministries (departments), there are a series of regional-level entities (CJCs, regional skills partnerships, Public Service Boards, etc.) as well as local authorities whose activities affect regional development. However, no single actor is charged with the co‑ordination of all these activities. There is also no mechanism to identify and create an overview of sectoral policy interventions in regions. In other words, there is currently a co-ordination gap for regional development.

The absence of a common regional development thread and overall co-ordinator presents two risks: i) unclear roles and responsibilities; and ii) a focus on economic development at the expense of a more integrated approach. First, in the Welsh Government, “who does what” for regional development is not always clear. Stakeholders have noted a lack of clarity in the roles and responsibilities for regional development (OECD, 2023[4]). Furthermore, Welsh Government teams involved in regional development do not have the mandate, incentive or appropriate forum to initiate a systematic discussion about roles and responsibilities for regional development.

The second risk is a predominant focus on economic growth in the regional development policy agenda. On the Welsh Government website, regional development initiatives are largely featured in “Regional and city economies”, as a sub-topic under “Business, economy and innovation”. Most of this web page content focuses on growth zones, the REFs, the City and Growth Deals, enterprise zones and freeports (Welsh Government, 2023[27]). This may simply reflect the emphasis placed by the Welsh Government on a regional development approach focused primarily on economic factors. While a focus on economic development is more than reasonable, attention should be paid to avoid reducing regional development to regional economic development (OECD, 2020[3]). Without a regional development strategy, a unified strategic thread or a designated co-ordinator who could also promote and oversee cross-sector collaboration, regional development will continue to be realised through sector-specific policies, programmes and investments, which risks further compounding fragmentation in the regional development space. In the long run, it could lead to a narrow and/or unclear focus of regional development and the strategies or policies that support it, as well as a suboptimal use of already scarce resources (OECD, 2020[3]).

The present co-ordination gap will need to be addressed to advance regional development more successfully. The ideal approach – and the one highlighted in the 2020 report – is to establish a team with a clear mandate to co-ordinate regional development activities (OECD, 2020[3]). This team may be ideally placed within the Office of the First Minister to boost its sector-neutrality. Doing so may require strong political consensus and could also take some time to set up. Alternatively, in the short term, the Welsh Government could either appoint one team as the regional development co-ordinator or a taskforce consisting of staff across several teams responsible for activities with regional development impact. This regional development co-ordination team, or taskforce, could undertake three main activities in the short and medium terms:

1. Conduct a comprehensive review on “who does what” and establish a new “norm” for sharing regional development responsibilities. If the Welsh Government wants to reinforce a more vision-oriented, objective-based approach to regional development, a comprehensive review of how regional development is connected among policy areas and teams could be the first step. Such a review could map current roles and responsibilities, potential synergies and the decision-making processes. The government could then use this as a basis to establish a new “norm” regarding the division of responsibility in regional development work, clearly identifying who is expected to do what and the expected outcomes. This includes, for example, how Welsh Government departments can work with regional bodies in areas related to regional development. A precondition for a new norm is agreement at the ministerial level followed by senior civil service leadership with staff. Clarifying roles and responsibilities is particularly critical if the regional development policy objectives intend to address broad and cross-cutting societal issues (e.g. sustainability, demographic change, green energy, enhancing the quality of public services) and cover a wide range of policy areas (e.g. transport, education, health) (Box 2.5). The mapping exercise should be done collaboratively with policy makers in different sectors, including the Future Generations Commissioner to ensure coherence with the Well-being for Future Generations (Wales) Act.

2. Better define the links among objectives, resources, actors and policy interventions in regional development and evaluate the policy impact. In the Welsh Government, it is currently difficult to get an overview of the scope and financing of initiatives related to regional development or how different initiatives are interrelated, a difficulty also faced by other countries, including Sweden (Box 2.5). For example, in the absence of EU funds, there is no Welsh budget category/expenditure area dedicated to regional development (Welsh Government, 2022[28]). Stronger links between objectives, resources, actors and policy interventions could help the Welsh Government gauge how effective different regional development activities are in advancing policy objectives and assess whether resources allocated to these activities are being optimised. This evidence can support the Welsh Government’s improvement of regional development policy design and implementation.

3. Actively co-ordinate with sectoral policy makers to ensure the regional perspective in relevant sectoral policies. This team could be responsible for streamlining the regional development issues discussed in different inter-ministerial dialogue platforms and systematically help sectoral policy makers adopt the regional lens when they design strategies and policy interventions that strongly impact the regions (see further analysis in the section below). To this end, it would be important for this team to have regional development data and analyses that can support sectoral policy making. This team can also lead the development of the regional development dashboard, as recommended in Chapter 1.

Box 2.5. Key issues arising in a strategy review by the Swedish National Audit Office

In 2022, the Swedish National Audit Office published its evaluation of whether the government managed the state’s efforts in regional development policy in such a way that policy objectives could be achieved. The report identified weak conditions for effective collective government actions for regional development in Sweden and highlighted that these could be detrimental to implementing the new National Strategy for Sustainable Regional Development 2021-2030. Compared to the previous strategy, this has broadened the policy focus on sustainability, broad societal challenges and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which involves an even greater range of policy areas and actors.

The key issues identified in the audit report include:

Lack of clarify over roles and responsibilities: While the roles and responsibilities of state authorities and subnational entities are set out in the Act on Regional Development Responsibility and the Ordinance on Regional Growth Work, there is still considerable room for interpretation. The national government’s role is unclear and this is keenly felt at the regional level. It makes co-operation between regions and the central level difficult and has become an issue concerning different areas related to regional development work (e.g. broadband, rural development, energy, labour market).

Need for a clear and long-term perspective for collaboration: While regional development work is long-term by nature and there is a long-term strategy in place, the assignments to the relevant authorities, various calls and offers to regions and funding are generally short-term. This makes long-term co-operation and learning difficult.

The direction of the policy has changed more than its content: Building on the previous national strategy, the updated strategy includes sustainability, broad societal challenges, etc. However, the budget lines/headings did not change accordingly. The varying conditions of the regions and the difficulties in co-ordinating resources among sectors makes it challenging to get an overview of the scope and financing of regional development policy and how different activities are connected. This, in turn, creates difficulties in co-ordinating and evaluating policy.

Some recommendations provided by the audit office include:

Develop an action plan for the National Strategy for Sustainable Regional Development 2021-2030 to further clarify the roles of relevant authorities and create better conditions for sector-wide collaboration.

Carry out an assessment of regional development policy, to define the linkages between policy objectives, resources, initiatives and actors as well as evaluate policy impact.

In the assignments related to regional development, ensure clear objectives, requirements and expectations for government interagency collaboration. For authorities that the government considers to be particularly important for regional development work, tasks should be included in the instructions.

Commission the Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth to follow up on the implementation of the National Strategy for Sustainable Regional Development Throughout the Country 2021-2030.

Source: Bachtler, J. and R. Downes (2023[26]), Rethinking Regional Transformation: The State of Regional Policy in Europe, https://eprc-strath.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Rethinking-Regional-Transformation-EoRPA-report-23_1-ISBN.pdf; Swedish National Audit Office (2022[29]), The National Audit Office’s Report on the Regional Development Policy (in Swedish), https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/1736596b36474f7f8c8a0f4f8456f9e4/2223005webb.pdf; OECD (2022[30]), OECD Territorial Reviews: Gotland, Sweden, https://doi.org/10.1787/aedfc930-en.

In the long term, if the Welsh Government develops an integrated regional development strategy, this team could also help ensure the implementation of such a strategy. This means ensuring that priorities are translated from the strategic to the operational level. Such a team can draw inspiration from other initiatives to improve policy delivery across the Welsh Government, such as the recently instituted Office of Project Delivery to help “professionalise” policy and programme delivery, including through functional standards. Such a team could also enhance monitoring and reporting on priority areas, creating and disseminating more integrated, bigger-picture assessments of the success of government policy in regional development priority areas.

Strengthen and diversify co-ordination mechanisms for regional development

In addition to a co-ordination gap in the regional development space, the Welsh Government faces other co-ordination challenges in this domain. Today, despite numerous permanent and ad hoc dialogue platforms5 focusing on diverse aspects of regional development – from investment to economic development to co-operation and partnerships – none are explicitly mandated to co-ordinate and assume responsibility for an overarching regional development agenda. While the meetings and relevant reports generated from these groups are published on line, how the agendas and priorities discussed across these bodies align or complement each other remains unclear. In addition, the outcomes of these discussions are not binding for Wales’s various departments when making decisions with regional-level impact. There is no actor that “connects the dots” among these regional development discussions and debates for the Welsh Government. A more effective use of these platforms and clearer uptake of the discussion results could sharpen the regional lens that the Welsh Government is establishing for regional development policy making and implementation.

The Strategic Forum for Regional Investment in Wales serves as a dialogue platform, in the main to discuss EU replacement funds, and the Welsh Government could consider broadening its scope and boosting its ability to collaborate with more regional development stakeholders. The current terms of reference for the strategic forum describe its purpose as sharing “a strategic overview of regional investment”, including applying the principles of the Framework for Regional Investment in Wales, sharing expertise, experiences and good practices to ensure maximum impact from investment funds and supporting Welsh local authorities in their delivery of UK investment funds (Welsh Government, n.d.[31]). To do so, it brings together a wide array of stakeholders, including the Welsh Government, the CJCs, local governments, the third sector, trade unions, higher and further education institutions, a Future Generations Commissioner representative, and natural resources, environment, rural, equality, well-being, economy and business representatives (Welsh Government, n.d.[31]). Its Welsh Government representation includes staff working in the areas of EU replacement funds, the regional offices, economic strategy, skills and higher education, housing and regeneration and rural development. Policy makers in other sectors closely related to regional development (e.g. health, environment, transport, spatial planning, etc.) are not represented in this forum.6

The future mandate of the forum could be expanded beyond sharing knowledge and views on the replacement EU funds landscape to supporting integrated regional development by co-ordinating various policy areas. The forum has the potential to be a platform to discuss: i) the territorial impact of different sectoral strategies and policies; ii) how regions can better help achieve regional development goals while advancing sectoral objectives; and iii) how to ensure the complementarities of investment activities at national and regional levels, including regional investments (e.g. City and Growth Deals, investment zones, the ARFOR programme, the Heads of the Valleys programme) and sectoral investments at the regional level. To expand the mandate of the forum, its membership may need to be updated to include policy makers in sectors related to regional development. It could start with sectors mentioned in the regional investment framework and/or sectors highly relevant to CJC functions (e.g. transport, land use, potentially energy). These policy makers could, in the beginning, be engaged on an ad hoc basis. For example, one meeting could be dedicated to transport in regions with policy makers from the transport department and another could focus on spatial planning and land use. In the long term, these policy makers could become permanent members of the forum. The results of the discussions could be directly reflected in sectoral policies and strategies (for example, relevant policy strategies could have one section dedicated to assessing the territorial impact or demonstrating how it aligns with regional development priorities). The results of discussions should be presented to relevant ministers and the First Minister’s Office at least annually or biannually. To expand the scope of the forum would require updating its terms of reference, an activity that could be led by the regional development co-ordination team recommended in the previous section.

Overall, more attention could be paid to the co-ordination environment for regional development overall, which could help create a more robust and effective cross-sector, multi-stakeholder system. To do so, a mix of co-ordination mechanisms will need to be adopted to buttress and advance the work of a dedicated co-ordination team and dialogue platform like the Strategic Forum for Regional Investment in Wales. Consideration should be given to the most appropriate cross-sectoral co-ordination mechanisms for regional development given Wales’ multi-level governance arrangements and its development ambitions. Table 2.1 presents four main categories of co-ordination mechanisms – organisational, strategic and policy instrument and rules-based – forming a theoretical framework the Welsh Government could use as it considers the practicalities of co-ordination mechanisms. The absence of a clear strategic thread for regional development, and the currently limited level of cross-sector, multi-level co-ordination for regional development indicates focusing on organisational and strategic co-ordination mechanisms (i.e. designating a co-ordination team, strengthening the dialogue platforms and defining integrated regional development objectives) should be priorities. Regardless of the mechanisms the Welsh Government chooses to reinforce and diversify co‑ordination and create an effective cross-sectoral system to support regional development, it will require ministerial agreement and strong senior leadership to move forward.

Table 2.1. Categories of national-level, cross-sector co-ordination mechanisms for regional development

|

Category |

Description |

Examples |

|---|---|---|

|

Organisational co-ordination |

Foster joint working across policy areas/sectors. |

Inter-ministerial committees, multi-level structures or dialogue bodies engaging multiple line ministries; special units for cross-sectoral co-ordination; a full‑fledged Ministry of Regional Development. |

|

Strategic policy co-ordination |

Setting joint objectives for shared policies, reconciling sectoral interests and determining priorities, especially in the event of trade-offs across sectoral policies. |

Regional development strategies with cross-cutting objectives and goals for multiple policy sectors. |

|

Policy instrument co‑ordination |

Concrete policy actions to pursue cross-cutting strategic goals, pooling resources for co-ordinated measures. |

“Bundling” of sectoral instruments in specific territories, sometimes based on multi-level negotiations with multiple line ministries. |

|

Rule-based co-ordination |

Constitutional, legislative, regulatory or methodological provisions to facilitate systematic, and sometimes mandatory co-ordination across policy sectors and vis-à-vis other levels of government. |

Formal legal competencies, use of administrative orders, eligibility rules and criteria, regional “proofing” or appraisal of sectoral policies. |

Source: Adapted from Ferry, M. (2021[32]), “Pulling things together: regional policy coordination approaches and drivers in Europe”, https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2021.1934985; OECD (2011[33]), Estonia: Towards a Single Government Approach, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264104860-en; OECD (2010[34]), Regional Development Policies in OECD Countries, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264087255-en.

In the long term, the Welsh Government could strengthen and pursue other types of co-ordination mechanisms, such as policy instrument co-ordination. For example, this could take the form of formal agreement among relevant line ministries and CJCs to co-design and deliver a package of investment projects. For this to be successful, CJCs must have sufficient investment design and implementation capacity. Alternatively, the Welsh Government could consider using financial or non-financial incentives to encourage the pooling of sectoral resources together to develop and deliver co-ordinated regional investment programmes. One inspiration comes from Poland, which harnesses policy instrument co‑ordination for investment through its sectoral contracts (Box 2.6). This form of co-ordination can bring together policy makers from diverse sectors to advance concrete regional development programmes and projects, setting a foundation for trust-based, long-term partnerships. This form of co-ordination benefits from strong ties to regional development strategy. If it is used without a clear, agreed-upon strategy for regional development, it could backfire; line ministries may be reluctant to share resources without understanding the strategic importance. Regardless of whether a government depends on a strategy for regional development or focuses on ensuring that a strategic thread is in place, clear and effective co‑ordination of actors and objectives is fundamental. In the case of a single strategy, this can serve as a co‑ordination platform as the relevant parties have, in theory, contributed to and agreed with its aims. In the case of a strategic thread, there may be a need for a mix of co-ordination mechanisms as there are multiple actors (sectors), each with their own objectives contributing to regional development. In this scenario, co-ordination becomes even more critical to unite diverse strategies and policies, and ensure that activities also support the strategic objectives.

In the near future, the Welsh Government may need to develop clear guidance, standards or even regulatory provisions (rules-based co-ordination) regarding how line ministries systematically consider regional/CJC strategies and priorities. This can be in a “softer form” of territorial impact assessment methodology as developed by the Ministry of Regional Development in Czechia, voluntarily used by line ministers (Box 2.6), or in a “harder” form such as the regulatory provision on territorial impact assessment in Norway (Government of Norway, 2017[35]; Ferry, 2021[32]). The Welsh Government could also provide guidance or standards around how line ministries effectively engage with CJCs in national policy making, especially as the CJCs advance in regional planning and policy delivery in the future. If the Welsh Government is set to do so, such guidance or standards should be established together with regional bodies and local authorities to ensure buy-in.

Box 2.6. Co-ordination mechanisms for regional development policy in Czechia and Poland

Sectoral contracts in Poland (policy instrument)

To implement the National Strategy for Regional Development 2030, Poland adopted sectoral contracts to co-ordinate actions taken under various policy areas and closely involved sectoral ministers in implementing and supporting regional policy measures. Polish sectoral contracts are agreements between the sectoral minister(s), the regional development minister and the Voivodeship Board (regional governing boards) that set out how a territorial-oriented intervention or a programme will be implemented (e.g. financing). These contracts help ensure that national-level policy decisions take regional priorities into account.

Territorial impact assessments in Czechia (rule-based)

In Czechia, supporting the integration of a territorial dimension in national policy making is an important theme. One of the strategic directions highlighted in Czechia’s Regional Development Strategy 21+ is to better monitor and understand the territorial impact of sectoral policies so that these policies can be more effectively co-ordinated to serve regional interests. This is not an easy task since the Ministry of Regional Development has no specific mandate to enforce a territorial lens in other policy areas. One of the instruments the ministry uses is territorial impact assessment (TIA). It has created a detailed methodology to motivate and support regions, municipalities and national line ministries in better understanding the territorial impact of their projects. The Ministry of Regional Development also organises ad hoc workshops with line ministries and individual regions to explore how sectoral policies affect the development of a given region, supporting the use of TIA.

Source: OECD (2023[36]), OECD Regional Outlook 2023: The Longstanding Geography of Inequalities, https://doi.org/10.1787/92cd40a0-en; Government of Poland (2020[37]), National Strategy of Regional Development 2030: Socially Sensitive and Territorially Sustainable Development (Summary), https://www.gov.pl/attachment/09b51b0c-4d33-4257-87f2-5a89b52f7953; Ministry of Regional Development in Czechia (n.d.[38]), Effects of Territorially Determined Projects: Methodology for Evaluating the Territorial Impact of Interventions/Projects, https://mmr.gov.cz/getmedia/f6897ae9-8244-44a5-99da-618996e69f82/Methodology.pdf.aspx?ext=.pdf.

Adjust ways of working to support integrated regional development

Examples of cross-sectoral, or integrated, working – fundamental for more effective regional development – exist in the Welsh Government but are the exception rather than the rule. Welsh Government staff shared the perception that when faced with a common challenge, teams are able to come together and work effectively, efficiently and successfully (OECD, 2023[4]). The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that various sectors of the Welsh Government can collaborate to respond to rapidly evolving circumstances. However, like in many governments, Welsh Government teams tend to operate within their specific policy and budget areas. A shift towards a more integrated Welsh Government starts from within, with measures to encourage a collaborative culture and streamline internal processes. A shift towards a more integrated Welsh Government starts from within, with measures to encourage a collaborative culture and streamline internal processes.

The Welsh Government has taken steps to improve integrated work in specific areas. For example, the First Minister7 requested a Cabinet review of the effectiveness of cross-government work in six key areas (including infrastructure, climate, mental health and the fight against racism), which concluded that cross-government engagement should take place at an earlier stage to identify and properly consider any conflicts, trade‑offs, multiple outcomes and benefits (Welsh Government, 2024[39]). The Welsh Government plans to take forward the findings related to working methods as part of WG2025, a three-year programme for organisational change and continuous improvement (Welsh Government, 2024[39]).

As the COVID-19 response illustrated, there is significant capacity for collaborative working in the Welsh Government that could be harnessed to advance regional development across the organisation. However, this task is not without its challenges. Collaborative working is not systematic and is frequently rooted in personal relationships among staff (often at the G6/G7 level)8 who have been in the Welsh Government for some time (OECD, 2023[4]). While this is a characteristic of small-state administrations (OECD, 2011[33]), it creates risks, not least that staff turnover undermines collaborative work currently taking place in the form of existing relationships. In addition, personal relationship building depends in part on individual motivation and time. With human resources already stretched thin, some Welsh Government staff interviewed by the OECD can feel they do not have time to co-operate or build the relationships that underpin co-operation within the organisation. In a context of limited resources, Welsh Government staff feel that co-operation is often a luxury their teams cannot afford (OECD, 2023[4]).

Senior civil servants and executive bands (G6s/G7s) have a role to play in setting clear and realistic expectations for collaborative work and modelling such work for regional development. Working together ranges from simply sharing information (co-ordination) to actively working towards shared goals (co‑operation) and deeply integrated teamwork with open, direct communication and joint planning (collaboration) (Box 2.7). The greater the level of engagement – from co-ordination, co-operation to collaboration – the higher the “cost” in terms of dedicating time and resources into building the structures, processes and relationships (Wales Centre for Public Policy, 2021[12]).

Box 2.7. Co-ordination, co-operation and collaboration

Co-ordination, co-operation and collaboration build on each other, where co-ordination forms the platform from which co-operation and then collaboration can grow.

Co-ordination: Joint or shared information insured by information flows among organisations. Co-ordination implies a particular architecture in the relationship among organisations (i.e. centralised or peer-to-peer; direct or indirect) but not how the information is used.

Co-operation: Joint intent on the part of individual organisations. Co-operation implies joint action but does not address the relationship among participating organisations.

Collaboration: Co-operation (joint intent) together with direct peer-to-peer communication among organisations. Collaboration implies both joint action and a structured relationship among organisations.