Wales has established regional Corporate Joint Committees (CJCs) to support regional-level collaboration, governance and development. However, local authorities continue to query the expectations and benefits of CJCs as well as the motivations behind them. This section discusses the rationale behind the establishment of the CJCs and explores the fundamental building blocks that will determine the success of the CJCs during this critical early stage. These building blocks include clarity on the CJCs’ purpose, clear impact that is communicated to stakeholders, strong accountability and inter-regional co-operation.

Regional Governance and Public Investment in Wales, United Kingdom

3. Harnessing the power of regional working

Abstract

Introduction

Wales established a new governance mechanism, the Corporate Joint Committees (CJCs), to better support local government collaboration. Legislation provides that the 22 local authorities of Wales collaborate through the CJCs in land use (spatial planning) and transport and to promote “economic well‑being” (Welsh Statutory Instruments, 2021[1]). Wales already works with a regional logic in certain areas, for example the Regional Partnership Boards for health and care services and the Regional Skills Partnerships for addressing regional skills needs. But the CJCs mark the first time Wales places significant development and planning responsibilities at a regional level.

Ultimately, it is for the local authorities comprising the planning regions to decide the shape of their CJCs beyond the basic structures and outputs required by law. However, local authority discomfort with the legislation establishing CJCs has dogged the new structures. While constituent local authorities have leeway to shape the CJCs beyond the basics, they do not always perceive that they have the space to do so. This chapter explores two necessary prerequisites for CJCs to best serve their regions: i) a clear purpose and goals; and ii) strong institutions with adequate capacity that produce visible results.

The “why” behind the Corporate Joint Committees

The rationale behind the CJCs draws upon international experience with co-operation among local authorities. In many OECD countries, municipalities come together in a regional governance structure with a greater or lesser degree of formality. Co-operation within such an arrangement can help municipalities better plan activities, deliver services, meet requirements in expertise (e.g. specialised experts or inspectors) and much more. In Wales, where previous attempts to build scale through municipal mergers did not bear fruit, the CJCs represented a way to facilitate collaborative working among local authorities to plan and act on a scale that allows for a more efficient allocation of resources (capitalising on economies of scale and lowering transaction costs). Beyond the resource savings, the Welsh Government also hoped the CJCs would create greater opportunities for shared problem solving, collective ideas and ultimately better outcomes for residents’ lives (Welsh Government, 2021[2]). This section summarises the “why” behind the CJCs, drawing on international experience with regional governance.

In Wales, co-operative regions were established to build territorial scale and favour cross-local authority collaborative working

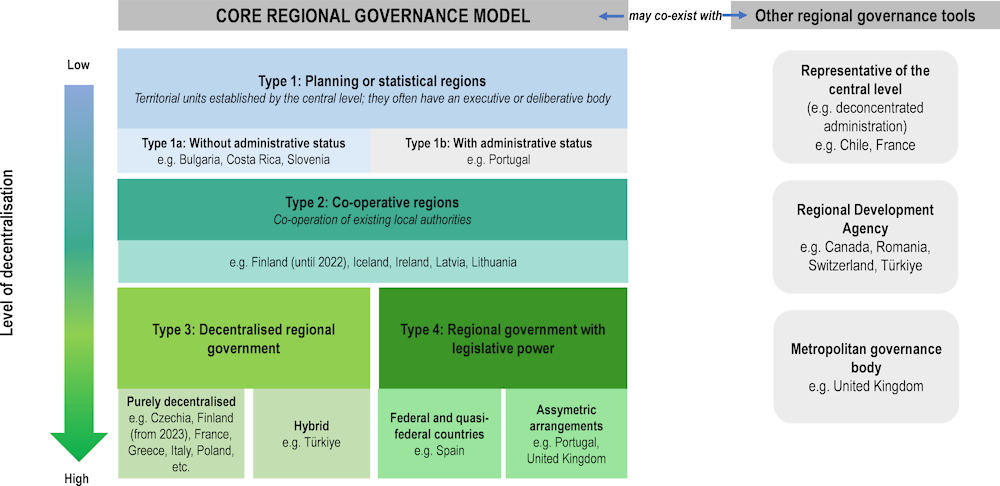

Regional governance takes different forms, depending on the purpose of the co-operation and the context within which it takes place. Models for regional governance range from softer to harder forms, with some focusing on dialogue and co-ordination while others create a supra-municipal body or metropolitan-level governance body. Regional governance structures may focus on a single sector or span multiple sectors. In addition, regional governance structures draw on different sources of funding and, of course, have different responsibilities (OECD, 2022[3]).

A regional governance model represents a greater or lesser degree of decentralisation (Figure 3.1). Representing the lowest degree decentralisation, planning or statistical regions are established by the central level of government and lack legal personality and their own administration or budget. Co-operative regions represent a greater degree of decentralisation, bringing together existing local authorities in a regional association with legal status. Finally, regions with legislative powers represent the greatest degree of decentralisation, having a high level of political autonomy and large responsibilities (OECD, 2022[3]).

Figure 3.1. The four types of regional governance models in the OECD and European Union

Note: The examples of the four models outlined in the figure represent a snapshot taken at a moment in time, as regional arrangements are not static and constantly evolving.

Source: OECD (2022[3]), Regional Governance in OECD Countries: Trends, Typology and Tools, https://doi.org/10.1787/4d7c6483-en.

Co-operative regions, like the CJCs, have certain distinguishing characteristics. They bring together local authorities within a regional structure, typically preserving the rights and authority of local governments. The creation of co-operative regions involves extending the attributions of local governments within this structure or institutionalising their collaboration in a broader framework. These regions have legal status and are characterised by regional councils and cabinets or offices to run their activities. Co-operative regions have their own budgets, funded by contributions from municipalities, central government transfers and sometimes other sources, such as European Union (EU) funding or user fees (OECD, 2022[3]).

Co-operative regions generally have limited responsibilities. They are most common in countries where local authorities possess competencies and functions that can be more efficiently managed at a larger regional scale. Their responsibilities often include regional development, spatial planning, public investment funds management and other regionwide tasks. Regional associations sometimes undertake other responsibilities that are assigned to them by their members, such as tasks related to waste collection or the administration of school offices (OECD, 2022[3]). Responsibilities depend on where planning or acting on a regional scale can provide the most value (Box 3.1).

Box 3.1. Inter-municipal co-operation can offer different potential advantages

Co-operative regions are one way to structure co-operation between municipalities, in the hope that it can produce some of the benefits of inter-municipal co-operation. One of inter-municipal co-operation’s most widely cited promises is optimising the scale for investment and public service provision by taking advantage of economies of scale and reducing transaction costs (OECD, 2020[4]). Municipalities may come together for any number of reasons, including to pool back office functions (like public procurement or payroll), share information, share staff or increase their creditworthiness (OECD, 2014[5]; CoE/UNDP/Open Society LGI, 2010[6]). The horizontal networks created through inter-municipal co-operation can favour information exchange, jointly generated ideas and collaborative problem-solving among municipalities in a range of areas. In El Salvador for example, municipal associations work together to solve electricity and running water provision challenges (Muraoka and Avellaneda, 2021[7]). They may also come together to address issues extending beyond municipal boundaries. In a region of the United States, for example, municipalities enter into inter-municipal watershed agreements to manage issues related to a watershed that extends beyond their borders (Hudson River Watershed Alliance, n.d.[8]; Morgan et al., 2023[9]; Rayle and Zegras, 2012[10]).

While the theoretical foundations point to potential efficiency gains from inter-municipal co-operation, mixed messages from data suggest that policy makers should not automatically assume cost savings. A limited amount of data from other jurisdictions shows that this approach can pay off, although not always (OECD, 2022[11]). Some studies have found economies of scale that led to savings and/or quality improvements in service provision (Bel and Mur, 2009[12]; Struk and Bakoš, 2021[13]; Aldag, Warner and Bel, 2020[14]), while others found no change or even negative associations (Frère, Leprince and Paty, 2014[15]; Kortelainen and et al, 2019[16]; Aldag, Warner and Bel, 2020[14]).

Cost savings are only one justification for inter-municipal co-operation. In some countries, municipalities are simply too small to organise the most demanding services alone. Inter-municipal co-operation can then offer a solution to both efficiency and capacity issues.

Source: OECD (2020[4]), The Future of Regional Development and Public Investment in Wales, United Kingdom, https://doi.org/10.1787/e6f5201d-en; OECD (2014[5]), OECD Council Recommendation on Effective Public Investment across Levels of Government, https://www.oecd.org/effective-public-investment-toolkit/; CoE/UNDP/Open Society LGI (2010[6]), Inter-municipal cooperation: Toolkit manual, https://rm.coe.int/imc-intermunicipal-co-operation/1680746ec3; Muraoka, T. and C. Avellaneda (2021[7]), “Do the networks of inter-municipal cooperation enhance local government performance?”, https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2020.1869545; Morgan, M. et al. (2023[9]), “Inter-municipal cooperation and local government perspectives on community health and wellbeing”, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12597; Rayle, L. and C. Zegras (2012[10]), “The emergence of inter-municipal collaboration: Evidence from metropolitan planning in Portugal”, https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.722932; Bel, G. and M. Mur (2009[12]), “Intermunicipal cooperation, privatization and waste management costs: Evidence from rural municipalities”, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2009.06.002; Struk, M. and E. Bakoš (2021[13]), “Long-term benefits of intermunicipal cooperation for small municipalities in waste management provision”, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041449; Aldag, A., M. Warner and G. Bel (2020[14]), “It depends on what you share: The elusive cost savings from service sharing”, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muz023; Frère, Q., M. Leprince and S. Paty (2014[15]), “The impact of intermunicipal cooperation on local public spending”, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013499080; Kortelainen, M. et al. (2019[16]), “Effects of healthcare district secessions on costs, productivity and quality of services”.

Co-operative regions come with their own set of challenges. A new layer of governance may increase administrative and monitoring costs (OECD, 2022[3]): this can be true immediately after a new layer is introduced or in the medium term. With a limited membership nominated by constituent municipalities, there is a risk of a democratic deficit and limited accountability and transparency, including for the budget. In addition, role clarity as regards other regional bodies can be lacking, a challenge also observed in English regional partnerships (Metro-Dynamics, 2020[17]). Finally, co-operative regions impose an additional financial burden for municipalities, which can be difficult to accept when budgets are strained (OECD, 2022[3]).

Efforts to restructure the territorial scale at the municipal level in Wales have floundered. The current local government structure, established in 1996, has been a subject of ongoing debate. Over the last two decades of devolution in Wales, the Welsh Government has initiated various commissions and reports, including the Beecham Review, Simpson Review and Williams Commission, aiming to assess public services, service delivery and public service governance. This research, perhaps best exemplified by the 2013 Williams Commission report, has suggested that many local authorities are too small to effectively deliver public services (Senedd Research, 2021[18]). Following the recommendations of the Williams Commission, attempts were made to implement changes. The Local Government (Wales) Act 2015 included provisions for authorities to merge voluntarily but the expressions of interest put forward by local authorities were rejected by the Welsh Government on the grounds that they did not sufficiently meet the criteria for moving ahead to prepare a full Voluntary Merger Proposal (BBC, 2015[19]; Andrews, 2015[20]). Subsequently, a draft Local Government (Wales) Bill was introduced in November 2015, which would have advanced statutory mergers and granted local authorities the power of general competence, among other changes. However, the draft bill did not progress further in the legislative process (Senedd Research, 2018[21]).

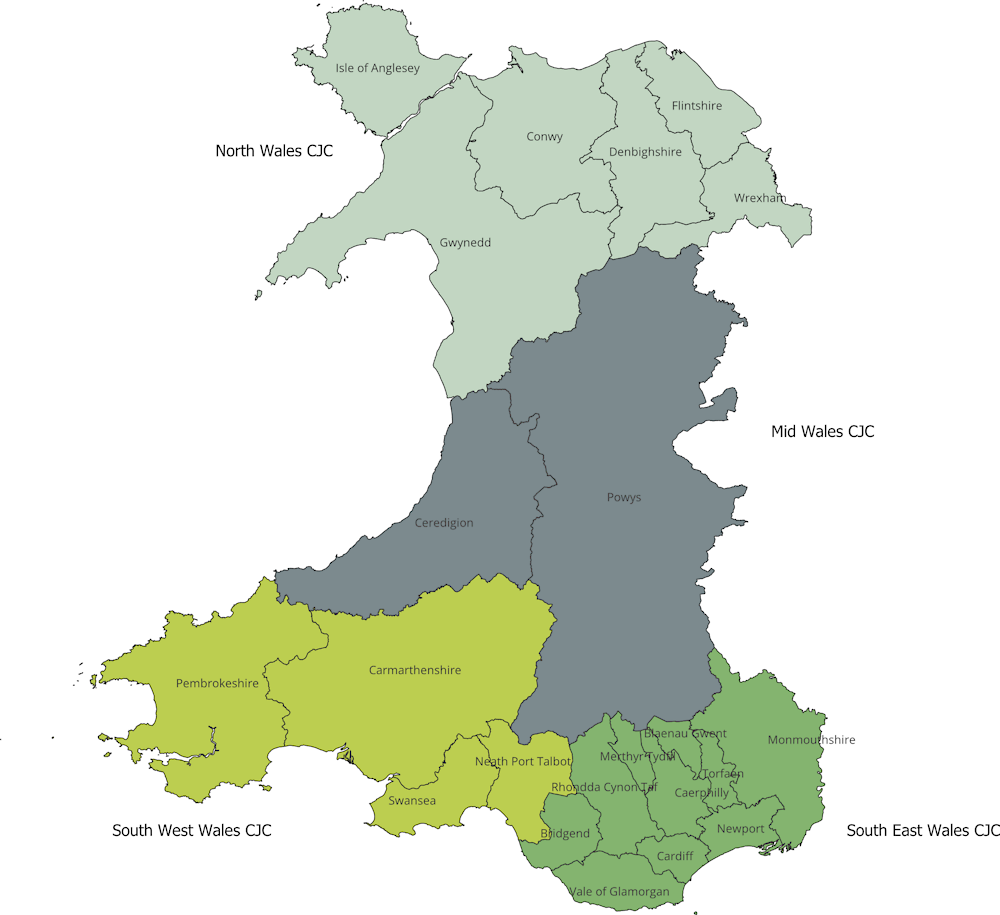

Following these unsuccessful attempts at mergers, the Welsh Government introduced the CJCs as an alternative way to “rescale” and manage planning and investment on a regional footing. The CJCs, established under the Local Government and Elections (Wales) Act 2021, serve as a mechanism for regional collaboration. According to the Welsh Government, the purpose of CJCs is to enable and support the delivery of important local government functions at a regional scale, with footprints agreed upon by local government leaders (Welsh Government, 2020[22]) (Figure 3.2). The outputs they are expected to begin producing immediately – Strategic Development Plans (spatial plans) and Regional Transport Plans – aim to enhance planning efficiency and create integrated and efficient transport networks. Their third attribution – economic well-being – is more ambiguous but asks councils to “do anything which it considers is likely to promote or improve the economic well-being of its area” (Welsh Government, 2022[23]).

Figure 3.2. Four CJCs for Wales

Source: Based on DataMapWales (2016[24]), Local Authorities, https://datamap.gov.wales/layergroups/inspire-wg:LocalAuthorities.

A need for greater clarity on the purpose and goals of the CJCs

The theoretical basis for the CJCs may be clear but the response from local authorities has not been overwhelmingly positive. This is reflected in a 2023 Audit Wales report on the CJCs that noted a mixed commitment to the CJCs among the local authorities, which the auditor thought was giving way to an “appetite for the CJCs [that] is more positive” (Audit Wales, 2023[25]). With a long history of inter-municipal co-operation, including within regional governance structures, some local authorities question the value added of the CJCs. In addition, a lack of clarity about Welsh Government expectations for the CJCs and some concerns about Welsh Government oversight of the CJCs trigger concerns that CJCs could erode local authority decision-making power and autonomy. These concerns have hindered the local authorities from shaping their CJCs beyond the basic legal requirements, although some local authority staff and elected officials see opportunities for a broader remit for their CJCs. This section explores issues around clarity.

Uncertainties and mismatched expectations limit local authority ownership of the CJCs

The regulatory framework clearly establishes the basic functions of the CJCs but leaves ample room for customisation. The regulations oblige the CJCs to produce a Strategic Development Plan (SDP) and a Regional Transport Plan (RTP) for their region and to promote regional economic well-being (Senedd Cymru, 2021[26]). Accompanying these core functions are the other statutory duties applying to public institutions. As a public body, the CJCs are tasked with promoting sustainable development, the Welsh language, diversity and equality, and biodiversity in their operations (Welsh Government, 2022[27]). Beyond these requirements, however, the law leaves an opportunity for the CJCs to consider other functions, even in new policy areas.

Within the framework provided by the law, there is leeway for the CJCs to explore efficiency-gaining organisational arrangements. The CJCs are bound by certain statutory duties related to the organisations themselves, including requirements for staffing and workforce and financial probity. The law makes provisions for loaned and seconded officers, raising the possibility of sharing back office functions as well as the time (and remuneration) of specialists, common arrangements in co-operative regions to make organisational management more efficient among local authorities. The law does not explicitly prohibit pooling service provision, another common way that local authorities co-operate to deliver services more cost-effectively. This idea has surfaced in Wales before, with proposals to model regional bodies after the combined authorities in England (United Kingdom) that deliver major services (Senedd Research, 2021[18]).

The law also provides basic governance requirements while allowing regions to customise the governance arrangements as they see fit. CJC regulations specify the membership of the governing body: a decision maker from each constituent council and from the relevant national parks.1 Each CJC can designate new members with a fixed term and with specified voting powers. The CJCs can establish sub-committees and are obliged to constitute one governance and audit sub-committee. The law includes a suite of other requirements: publishing a constitution, complying with a code of conduct, maintaining a general fund and managing records (Wales Statutory Instruments, 2021[28]; 2021[29]; 2021[30]; 2021[31]).

Despite leeway in the regulations for different functions and governance models, some local authorities expressed concern that the CJCs represent a one-size-fits-all approach to managing regional working. Voluntary regional working has taken different forms across Wales, in terms of the territorial footprint, functions and governance to respond to regional differences. The framework provided in law, even if it only establishes the skeleton of what the CJCs and their work will look like, represents a significant change from the status quo and risks appearing like a uniform approach that fails to address regional differences. While each CJC has its own establishing regulations, the text of the regulations is nearly identical (Wales Statutory Instruments, 2021[28]; 2021[29]; 2021[30]; 2021[31]). The suite of Welsh Government guidance that followed – which makes very little differentiation among the four CJCs (Welsh Government, 2022[27]; 2023[32]) – has reinforced this concern.

Local authorities also expressed concern that the Welsh Government will use the CJCs to control how local authorities co-operate beyond the core statutory obligations of the RTP and SDP. Some CJC members were surprised by a seemingly new requirement for the CJCs: producing a Child Poverty Strategy. In fact, drafting such a strategy is a legal requirement for local authorities, extended to the CJCs because of their legal status (Welsh Statutory Instruments, 2021[33]). To some interviewees, it was a signal of the possibility that the Welsh Government could expand the functions of the CJC beyond its core attributions.

These concerns point to an information and expectation gap. The information gap comes from a lack of clear communication on the requirements associated with the CJC, as well as where those requirements end. Beyond the information gap, there is an expectation gap: where there is no legal certainty, the CJCs tend to expect that the Welsh Government will shape the CJCs according to its own needs without consideration of the needs of the region.

The information gap permeates through to local authority staff. Focus groups showed that sometimes local authority staff, even those in relevant policy areas, did not have fundamental knowledge about the CJCs, including the CJCs’ role and the impact of the CJCs on their work (OECD, 2023[34]). This lack of awareness suggests limited communication about the CJCs from the CJC itself and from elected and appointed officials of local authorities to local authority staff, the staff who will play an important role in CJC implementation.

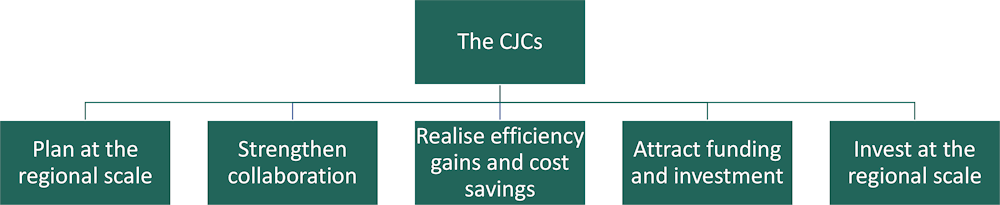

The information and expectation gaps have partly discouraged local authority ownership over the CJCs. The Welsh Government expects local authorities to take the initiative to customise their CJC according to their region’s needs and opportunities. Without first addressing the information and expectation gaps, however, local authority ownership over the CJCs may remain limited: they are reluctant to take bold action that could result in criticism or negative consequences (OECD, 2023[34]). Ownership is important. If the balance between bottom-up ownership and government oversight tilts too far towards the government side, the CJCs may fail to gain legitimacy and acceptance among local authorities (Metro-Dynamics, 2020[17]). Participants in CJC focus groups and workshops – involving mainly local authority officials and officers, and CJC officers – had a wide range of ideas for how their region’s CJC could add value (OECD, 2023[34]; 2023[35]). Together, these views suggest that participants see a role for the CJC beyond that of a co‑ordinator and a planner with a potential role in implementation, very much aligned with the concept behind the CJC regulations. Their ideas (Figure 3.3) include:

Planning at the regional scale: Participants often recognised the potential benefits of giving spatial and transport planning a regional perspective. Some local authority officer participants considered that planning in other policy areas (e.g. energy, rural affairs, environment, education and skills, innovation, leisure and well-being) could also make sense on this scale.

Strengthening collaboration: Participants recognised that the CJCs can play a strong co‑ordinating role within a constellation of existing bodies and programmes relevant to regional development in Wales. Some regional focus group participants even spoke of the potential for CJCs to rationalise the regional co-operation landscape, bringing other regional co-operation initiatives under the CJC umbrella.

Realising efficiency gains and cost savings for local government operations: Participants identified a range of functions that could result in savings for the local governments in their regions. They suggested that the CJC consider pooling certain shared administrative functions currently undertaken separately by individual local authorities.

Attracting funding and investment: Participants saw a potential role for the CJCs in attracting new funding and investment, including from external sources and from the participating local authorities. Some proposed that CJCs could help develop and promote a regional brand.

Investing at the regional scale: Finally, participants in all four CJC workshops saw the potential for their CJCs to invest at the regional scale. Given the overlapping footprints between the CJCs and the City and Growth Deals, this idea is natural. Indeed, two regions have decided to integrate their City and Growth Deal and their CJC (different approaches pictured in Table 3.1). The legal framework makes provisions for the CJC to administer investment but does not compel them to do so. Potential benefits of combining the CJC with the City and Growth Deal cited by focus group participants included economies of scale for the administration of these two areas and the CJC benefitting from the success of the City and Growth Deal.

Figure 3.3. A range of views on roles for the CJCs

Table 3.1. Different regional approaches to integrating the City and Growth Deals with the CJCs

|

North Wales |

Mid Wales |

South East Wales |

South West Wales |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

City and Growth Deal |

The North Wales Growth Deal |

The Mid Wales Growth Deal |

Cardiff Capital Region City Deal |

The Swansea Bay City Deal |

|

City and Growth Deal administering body |

Ambition North Wales |

Growing Mid Wales |

Cardiff Capital Region (CCR) |

The Swansea Bay City Deal |

|

Relationship between deal and CJC – staff |

Head of the Growth Deal programme office serves as CJC chief executive. |

The two joint strategic leads of Growing Mid Wales are the senior management officers of the CJC |

Director of the city deal serves as the interim chief executive of the CJC |

One of the local authority CEOs, who serves as well on the joint committee of the city deal, is the interim CEO of the CJC |

|

Relationship between deal and CJC – structure and functions |

The functions of the North Wales Economic Ambition Board will be transferred to the CJC (Isle of Anglesey County Council, 2021[36]) |

No firm decision to integrate the growth deal into the CJC |

CCR is “lifting and shifting” the growth deal into the CJC (Cardiff Capital Region Cabinet, 2022[37]) |

No intent to bring them together |

Source: House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee (2019[38]), City Deals and Growth Deals in Wales, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201919/cmselect/cmwelaf/48/48.pdf.

Some CJCs are already cautiously experimenting with an expanded remit. As mentioned above, two CJCs are incorporating the functions of their region’s City and Growth Deals into their CJCs. The South West CJC plans to expand the breadth of its work by adding regional energy planning under the umbrella of its CJC. However, focus groups suggested that, while the fact that the economic well-being function is only broadly sketched in law invites local authorities to make this function their own, the CJCs did not feel empowered to think bigger or act bigger. They voiced a perception that the Welsh Government might reject ideas beyond legal requirements.

The CJCs need the space to define – and experiment with – their roles and organisational structures beyond legal requirements. Roles and organisational structures can evolve over time and defining or adjusting them will rely on continuous dialogue with and among local authorities and other stakeholders to draw out shared goals. Eventually, however, discussion must shift to action and the CJCs will need space to learn by doing, which may include trial and error. Only in this way can they grow into the potential their local authorities and the Welsh Government see for them. One way to manage this is by testing or piloting new governance arrangements and functions. Well-designed experiments allow organisations to limit the risks of failure by first testing changes on a limited basis (in terms of time, scope, scale or territory). For experiments to deliver on their potential, they should reflect good practice from the public sector in other jurisdictions (summarised in Box 3.2). This includes designing experiments to favour organisational learning by building in feedback points. Without embracing change (which includes managing failure), the CJCs risk being too timid on the one hand – limiting their potential impact – or too sclerotic, on the other – failing to adapt to evolving circumstances.

The Welsh Government’s task is to play a supportive role. Simply providing the legal ability to expand CJC functions is not enough; CJC concerns about the Welsh Government overruling ideas for new or additional functions demonstrates this. Instead, the Welsh Government could choose to nurture “supported risks”. This may include supporting experiments or pilots by offering the Welsh Government expertise and knowledge, helping the experiment find its place within national strategies and policies, and sharing information regarding successful experiments – in Wales or elsewhere – to encourage further experimentation and help others learn (OECD, 2023[39]).

Box 3.2. Good practice for policy experimentation

Building blocks for good experiments

Experimentation in designing and implementing governance arrangements and policies can help policy makers generate new ideas, explore innovative approaches and gain valuable insights from both successes and failures. Good policy experiments require a thoughtful and purposeful approach to testing and refining new ideas. This approach starts from the earliest design phase and continues to monitoring, evaluation and learning:

Step 1: Assessing the situation. This includes whether the experiment will be supported by a culture of continuous learning and improvement, whether risks can be mitigated and whether there are potential legislative or regulatory obstacles.

Step 2: Planning the experiment. This includes clearly setting out objectives and priorities, considering stakeholder input and the possibility of course correction, thinking about how to share knowledge and favour learning, considering how the experiment may be scaled up and identifying required resources.

Step 3: Implementing the experiment. This includes identifying the institutional capacity that will implement the experiment and considering how stakeholder engagement will be integrated throughout the experiment’s lifecycle.

Step 4: Monitoring, evaluating and learning. This includes establishing robust ex post evaluation criteria and mechanisms, communicating results and capturing lessons.

Experimentation in practice in Canada

Canada puts experimentation at the core of place-based regional development policy to foster learning and community capacity building. The country uses pilots to implement hybrid contracts, which are important instruments in its regional governance framework. These projects are designed as experimental efforts to address complex, localised challenges – “wicked problems” – that defy conventional solutions by cultivating new insights and strategies for problem solving. Functioning as policy laboratories initiated by the federal government, these pilots promote exploration and the assessment of learning outcomes: learning by doing.

Canadian pilot programmes show how experiments can be expanded. The Urban Development Agreements (UDAs) led by Western Economic Diversification Canada for Vancouver and Winnipeg, for example, offered a model for a number of other Canadian cities while these agreements were in place between 1981 and 2010. Governments can also choose to retire experiments, like Canada’s pilot Action for Neighbourhood Change (ANC) strategies that did not find a government partner to carry on the work after the initial two-year mandate.

These two pilots also illustrate an important foundation of experimentation: measuring results. Each underwent some form of evaluation. For the UDAs, this included a survey of UDA government partners. For the ANC, a summative evaluation of the project measured progress against objectives.

Source: OECD (2023[39]), Regions in Industrial Transition 2023: New Approaches to Persistent Problems, https://doi.org/10.1787/5604c2ab-en; OECD (2018[40]), Rethinking Regional Development Policy-making, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264293014-en; Bradford, N. (2017[41]), “Flexible governance and adaptive implementation”, https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/Bradford_Canadian-Regional-Development-Policy.pdf.

A crowded field of Welsh regional co-operation creates fears of duplication

Welsh local authorities are no strangers to co-operation. Examples of inter-municipal co-operation are plentiful, including in areas within the purview of the CJCs: the existing transportation partnership in Mid Wales as well as the economic growth partnership of the Mersey Dee Alliance in North Wales and adjacent English municipalities. In addition, local authorities have a history of regional-level planning, including through the City and Growth Deals and the Regional Economic Frameworks produced by each region with the Welsh Government. Sometimes co-operation among local authorities is formalised in regional governance structures covering all of Wales, some having the same footprint as the CJCs. Table 3.2 shows how the CJCs compare to existing co-operative arrangements in terms of purpose, footprint and governance. While they predate the CJCs, these arrangements are still in place at the time of writing (although regions are integrating the City and Growth Deals with the CJCs – see Table 3.1).

Welsh local authorities were able to co-operate to carry out functions jointly through a joint committee, even before the CJCs were established (Browne Jacobson LLP, 2021[42]). Doing so, however, required considerable effort. For example, legal and financial agreements were required for each collaboration before local authorities collaborated on functions or shared budgets via these joint committees. The corporate model provided by the CJCs seeks to support collaboration by allowing local authorities to jointly share a budget, employ staff and/or discharge functions without the need for the long and complicated discussions previously required to do this. The Welsh Government hoped that the corporate model would help overcome practical barriers to collaboration (Welsh Government, 2023[43]).

Some local authorities, however, have difficulty identifying the unique value added of the CJCs (OECD, 2023[34]). Some prefer the flexibility of ad hoc inter-municipal co-operation established to fill a specific need. They also raised concerns that the CJCs could risk duplicating the activity of existing structures and partnerships. The perception that the CJCs do not offer unique benefits makes the effort and resources required to establish and maintain them seem inefficient, which can be especially unwelcome as local authority resources are already stretched. As the leader of one North Wales council put it: “We didn’t need a CJC to add to [existing regional] work, and it hasn’t added to the work. If anything, it’s created additional work” (Welsh Parliament, 2023[44]).

Table 3.2. A range of regional co-operative arrangements in Wales

|

CJCs |

Regional Skills Partnerships |

Regional Partnership Boards |

Public Service Boards |

City and Growth Deals |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Purpose |

Developing strategic development and regional transport plans, promoting economic well-being |

Driving investment in skills based on local and regional needs |

Understanding and fulfilling regional care and support needs |

Understanding and addressing local and regional well-being needs |

Drawing investment into the regions and promote economic development through a regional investment programme |

|

Footprint |

See Figure 3.2 |

Same as the CJCs |

Different from the CJCs (with 7 boards in total) |

Different from the CJCs (with 13 boards in total, many only covering 1 local authority) |

Same as the CJCs |

|

Governing body |

Joint committee of local authorities and the national parks |

Board composed of employers, education providers and others |

Board of local authorities, health boards and the third sector |

Board of local authorities, health boards, fire and rescue authorities, Natural Resources Wales and others |

Joint committee of local authorities |

Source: UK House of Commons (2019[45]), City Deals and Growth Deals in Wales, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201919/cmselect/cmwelaf/48/48.pdf; Welsh Government (2024[46]), Regional Skills Partnerships, https://businesswales.gov.wales/skillsgateway/skills-development/regional-skills-partnerships; Welsh Government (2021[47]), Local Health Boards, https://law.gov.wales/public-services/health-and-health-services/local-health-boards; Welsh Government (2022[48]), Regional Partnership Boards (RPBs), https://www.gov.wales/regional-partnership-boards-rpbs; Future Generations Commissioner for Wales (2023[49]), Public Services Boards, https://www.futuregenerations.wales/work/public-services-boards/.

Building strong CJCs that produce strong outcomes

Allaying the concerns of local authorities about the CJCs will require assurance that the CJCs are delivering for the region while not superseding the authority of local governments. Showing fast, tangible outcomes will help sway the opinions of detractors, be they elected officials, local authority officers or residents. A CJC that enables inter-municipal or cross-regional co-operation across CJC borders will also help overcome objections that the CJCs reduce flexibility in co-operation. Finally, strong accountability frameworks and robust monitoring, evaluation and learning will be critical to demonstrate outcomes to constituent local authorities and other stakeholders. This section explores how the CJCs can begin to create and evidence impact, supported by strong institutional governance. As well as the focus groups and workshops with the CJCs, this section draws from an OECD capacity-building toolkit developed for the CJCs, focusing on actions Wales’ CJCs can use to build their capacity in delivering their tasks within five building blocks (Box 3.3).

Box 3.3. Capacity-building toolkit for CJCs

In addition to formal organisational performance measurement and reporting requirements, internal temperature taking can help the CJCs ensure that their structures and activities advance objectives. Based on the OECD’s work with the CJCs, the OECD developed a set of building blocks for planning and executing regional development activities that the CJCs can carry out now or in the near future. Building blocks/checklists for good practices are supplemented with different examples from across the globe, identified in the toolkits for the CJCs.

The building blocks are presented within five areas:

1. Planning (and acting) strategically.

2. Understanding performance – monitoring, evaluation and learning.

3. Developing accountability.

4. Managing resources for greatest impact – human and financial.

5. Building and maintaining co‑ordination mechanisms.

Source: OECD (2023[35]), “OECD CJC action plan workshops”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

Securing the support of local authority elected officials requires fast, tangible benefits and strong communication

The motivations that come with holding elected office can help explain why the introduction of the CJCs has been met with a tepid reception by some local authority officials. Elected officials are motivated by voters and their needs, and few voters would consider a new layer of governance for regional co-operation a priority (CoE/UNDP/Open Society LGI, 2010[6]). Local issues form the backbone of the campaign for local elected office and office-holders may perceive the potential long-term benefits of collaborative working as uncertain and thus a hard sell to voters.

The resource needs of the CJCs make them an even harder sell to local elected officials. This is especially true in light of the financial position of some local authorities, where factors such as inflation and cost-of-living increases have significantly strained local authority budgets (Powys County Council, 2023[50]; Betteley, 2023[51]; Evans, 2023[52]). The same goes for human resources: some elected officials and local authority staff expressed concern that if the CJCs require local authority staff time to carry out their functions, this threatens to stretch the local authority workforce, limiting their ability to serve local needs (OECD, 2023[34]). Without showing benefits that justify costs, the CJCs could be perceived as a political liability rather than a political asset by local authority officials. Furthermore, it is the quick outcomes that will help win over elected officials, but co-operation can take time to bear fruit in many areas.

The motivations of local authority staff add another layer of complexity to the implementation of CJCs. They may feel little enthusiasm for engaging in regional projects perceived as extending beyond their job mandates, especially if the political and senior executive levels do not embrace the CJCs. Some local authority officers fear that the CJCs will impose new obligations that stretch their time even further (OECD, 2023[34]).

In the context of limited local budgets and anxieties about the future funding for CJCs, demonstrating the value of CJC work becomes critical. Some local authority staff are already seeing opportunities for efficiency gains from regional working, starting with sharing back office or technical functions, and some go as far as considering joint service delivery opportunities in the future. Leaders of local authorities are not always articulating the value added of CJCs in their territories, both for local authorities and citizens, rendering it more difficult to make the case for using taxpayer money to fund the CJCs, for example, or justifying the CJCs to citizens given other existing regional-level boards. For the CJCs and local authorities, articulating the value added of a new regional arrangement will require time and concerted effort to understand where their CJC can deliver value in the region, taking into consideration the whole range of potential advantages to co-operation, from efficiency gains to higher quality or greater variety of services and more. Where the Welsh Government is concerned, this will require support that empowers the regions to make the best use of their CJCs. Such support may not be directly financial but can take the form of tailored guidance, capacity-building support or staff time, especially given crunched public finances.

In parallel, stronger, more consistent communication among all parties will build trust in the CJCs. The Welsh Government can more proactively communicate to local authorities about their leeway to design their CJCs beyond the legal requirements and how the Welsh Government is prepared to support creating CJCs that best serve the interests of the region and its composing local authorities. Written guidance so far has not been considered effective at explaining the possibilities offered by the CJCs to local authorities. Given this, a series of open and frank discussions between the local authorities and the Welsh Government could better help parties arrive at shared expectations. It will be important that these messages are diffused by those participating in discussions with staff in relevant policy areas. The CJCs, then, can bring their member local authorities along with them through regular dialogue with local elected officials and chief executives beyond those serving on the CJC board and its subcommittees. Finally, senior officials of local authorities can ensure that communications about the CJC diffuse throughout local authority staff, providing the staff ultimately responsible for implementing CJC decisions with important background information and updates. The result should be systematic communication at all levels, where the Welsh Government, CJC officials, local authority elected officials and chief executives, and local authority staff are kept informed of the CJC’s plans and activities.

Co-operation need not end at CJC borders

The CJCs will need to look beyond their borders to produce the best outcomes for the development of their regions. Cross-regional co-operation in Wales already follows shared characteristics and objectives that transcend borders, such as cultural and linguistic characteristics and economic needs (e.g. the ARFOR and Valleys initiatives, discussed below). Cross-region co-operation extends beyond Welsh borders, too, like the River Severn Partnership between Mid Wales and English local authorities along the river catchment area (River Severn Partnership, n.d.[53]). Participants in CJC workshops across all four regions were adamant that the CJCs should not impede co-operation beyond the borders of the region.

Local authorities do not always see an active role for the CJCs in existing inter-regional co-operation (OECD, 2023[35]). Two notable examples of co-operation beyond regions come from Welsh Government initiatives elevated in the Co-operation Agreement between the governing party (Labour) and an opposition party (Plaid Cymru): the ARFOR initiative aims to invigorate Welsh language strongholds across North and West Wales and the Valleys initiative aims to drive development in a swathe of South Wales hit hard by deindustrialisation (Plaid Cymru, 2022[54]). While the Welsh Government sees an opportunity to implement these two place-based initiatives with CJC involvement, focus group participants from local authorities and the CJCs did not spontaneously see the CJCs as natural champions for these initiatives (OECD, 2023[34]).

However, they did see opportunities for the CJCs to actively encourage systematic inter-regional working to three ends:

1. Promote peer learning among CJCs. Participants in CJC workshops expressed a desire to learn from the other CJCs, especially in terms of what governance arrangements other CJCs have put in place and how they are carrying out their functions. Regular, open conversations among the CJCs can also provide a forum for exchanges of good practices and lessons learned.

2. Serve as a catalyst for joint initiatives and cross-regional projects that address the needs and aspirations of more than one region. These might include, for example, co-ordinating transportation planning to build transportation systems that make the most sense for the inhabitants of Wales.

3. Increase the bargaining power of local authorities in dealings with the Welsh Government. Instead of coming to the Welsh Government as 1 of 22 local authorities, a local authority becomes a part of a stronger bargaining unit, 1 of 4 CJCs.

Strong and clear lines of accountability provide confidence that the CJCs act in the interest of their region

At its most basic, accountability is “who does what and reports to whom” (OECD, 2020[55]). This simple definition masks what is often a complex and frequently political set of relationships, obligations and actions that hold a public body – like the CJCs – to account. Public bodies often have multiple lines of accountability. Some accountability requirements are embedded in legislation and are enforceable by law. The formal requirements that accompany these types of relationships may come in the form of ex ante guidance or directives, or ex post reporting and audit requirements. Many of these formal accountability tools in Wales will be familiar to the CJC’s members, as they also apply to local authorities. Other lines of accountability may be less formal. For example, the interactions between a government and citizens, media and the third sector – which create a form of “social accountability” – cannot be fully formalised (OECD, 2020[55]).

New lines of formal accountability between the CJCs and the Welsh Government can make some local authorities concerned about a decrease in the decision-making power of individual local authorities (Wrexham.com, 2022[56]). Appearing before a meeting of the Senedd Economy, Trade and Rural Affairs Committee, the chair of the North Wales CJC summarised his concerns:

[O]ne major weakness of the CJC is that we are shifting political accountability away from local authorities. There is a possibility, of course, that the CJC could make decisions that don’t follow the aspirations of the local authority, and that would put us in a very difficult position in light of the fact that it is a statutory body. … [I]t does create that tension with local authorities, and certainly takes accountability further away from the members and the public, indeed (Senedd Business, 2023[57]).

Some local authority participants in focus groups and workshops voiced concern that these reinforced lines of accountability to the Welsh Government will reduce the opportunity for CJCs to determine and enact a course of action that works for the region. Participants highlighted a recent Audit Wales report on the CJCs (Audit Wales, 2023[25]), expressing concern that the auditor’s review strayed into making assumptions about CJC policy directions instead of sticking strictly to the progress they were making against legal requirements.

While acknowledging the importance of good governance, some participants viewed the legal requirements for CJC governance, particularly scrutiny requirements, as rigid and cumbersome. The CJCs must put in place statutory officers (including a chief executive, chief finance officer and monitoring officer), governance and audit committees, scrutiny arrangements and specific sub-committees for key functions (Audit Wales, 2023[25]). Although the Welsh Government sees these arrangements as a way to strengthen accountability by constituent local authorities, some participants viewed these governance requirements as excessive, pointing towards examples of regional working that they see as flourishing within a very light governance structure. To participants, these lines of accountability between the CJC and the Welsh Government threaten to provide an undue opportunity for the Welsh Government to shape the CJC and its outcomes, which local authorities will largely implement.

Strong lines of accountability to constituent local authorities and citizens can counterbalance the accountability relationship between the CJCs and the Welsh Government. Local authorities were adamant that the CJCs should “answer to” their constituents, i.e. local authorities and residents. Some local authority representatives worried that the CJCs might produce a democratic deficit, expressing concerns about:

A lack of accountability to local authorities: The local authorities themselves constitute a CJC but not every local elected official will be able to have a direct line into the CJC’s decision making via a place on the governing board or membership on a CJC sub-committee. Those who do not sit on the CJC’s governing board or sub-committees will have more limited opportunities to shape the CJC and its agenda. At the same time, some who sit on the CJC or its sub-committees question whether they can make decisions on behalf of their own local authority in the absence of a specific mandate from their council to do so.

A lack of accessibility or representation for the residents of the region: The voice of residents becomes diluted if filtered through only a select number of elected officials serving on CJC committees. There is a risk that the full diversity of perspectives, needs and opinions of the broader resident population is not fully captured within the CJC’s decisions.

Strong lines of accountability between a CJC and its constituents can help mitigate the risk of a CJC that makes decisions counter to the region’s interests and ensure that the voices of residents help guide CJC work. Quality opportunities for input should be a central focus of the CJCs, involving formal consultations with members, providing leaders sitting on the CJC ample time to communicate decisions to their respective councils, ensuring strong communication channels between the CJC and its members that permeate throughout local authority staff and encouraging broad counsellor participation in scrutiny committees. Creating strong lines of social accountability can help ensure that the voices of the region’s residents guide the CJCs’ work. By actively incorporating these measures, the CJCs can establish a robust system that promotes inclusivity and responsiveness to the needs and perspectives of both member councils and the broader community.

Monitoring and evaluation will help ensure that the CJCs remain robust and able to deliver for their regions

Monitoring and evaluation will evidence the results of the CJCs, both the quick wins and the longer-term outcomes. The “learning” part of monitoring, evaluation and learning – those structures and processes that the CJCs use to learn from results and apply what they learn – will help the CJCs continue to improve their performance. As CJC objectives become clearer, it will be important to anticipate how progress against objectives will be assessed. Strengthening a CJC’s ability to measure progress towards its objectives will promote evidence-based decision making and allow the institution to course-correct if necessary.

The CJCs are subject to formal monitoring and evaluation requirements. The Local Government and Elections (Wales) Act 2021 introduces a framework of performance evaluation requirements for local authorities and CJCs. Both are required to report on performance in terms of:

1. The extent to which they are effectively carrying out their functions.

2. How they are using resources “economically, efficiently and effectively”.

3. How their governance furthers points 1 and 2 (Welsh Statutory Instruments, 2021[1]).

Each local authority and CJC must track how it meets performance requirements and report on its performance at least once a year. At least once a financial year, they must review the extent to which they are meeting their performance requirements, including the views of people and businesses in their area, through consultation with specified stakeholders and the public about performance. They are required to produce an annual self-assessment report concerning how they meet their performance requirements. At least once between ordinary local council elections, councils must appoint an external panel to report on performance after consulting a specified list of stakeholders and the public, a requirement that has been deferred for the CJCs until after the next local government elections in 2027 (Welsh Government, 2023[43]). In addition, local councils and the CJCs must maintain a governance and audit committee2 to scrutinise financial affairs, risk management, internal control, corporate governance and more (Welsh Government, 2022[27]). Finally, the law empowers the Auditor General for Wales to conduct inspections to assess how a local authority or CJC is meeting performance requirements (Welsh Statutory Instruments, 2021[1]).

The statute is not more prescriptive about the substance of subnational performance reviews and does not differentiate between local authorities and CJCs. The Welsh Government has not differentiated either: it issued statutory guidance for local authorities about performance evaluation (Welsh Government, 2021[58]) but it has not yet issued guidance tailored to the CJCs on this topic, although this work is underway.

Key messages and recommendations

The CJCs were created as co-operative regions to build territorial scale and favour cross-local authority collaborative work and initiatives. The CJCs can support the delivery of important local government functions at a regional scale through their core attributions of transport planning, spatial planning and economic development.

To gain acceptance by local authorities and citizens, CJCs will need to be outcome-driven institutions. A crowded field of regional co-operation and stretched local authority budgets means the CJCs will need to show results in these areas to justify their presence. Local authority officers see a range of opportunities for added value and looked for “quick wins” to bolster the CJCs in their early days. Inter‑regional co-operation is another avenue for increasing the impact of the CJCs.

Recommendation: Define the unique value added of the CJCs in each region

Encourage each CJC to identify its unique selling proposition (USP) that expresses its distinct contributions to regional development in broad consultation with constituent local authorities and other stakeholders.

Develop and share a concise “elevator pitch” document summarising the CJC’s USP for a broader audience (e.g. for residents, stakeholders in the various planning areas and those who can help implement plans).

The local authorities and CJCs are wary of an unvoiced Welsh Government agenda for the CJCs. The Welsh Government has not always effectively communicated its expectations for the CJCs to local authority officials and officers. Based on perceptions from past interactions with the Welsh Government, local authorities fear the Welsh Government may take an overly directive approach to the CJCs that will be tailored towards the needs of the Welsh Government rather than the needs identified by the regions themselves.

Recommendation: Communicate specifically what the CJC is and what it is not to CJCs and local authorities

Supplement the Welsh Government’s written guidance with open and frank discussions between local authorities, CJCs and the Welsh Government to establish shared expectations for CJCs.

Bring local authority staff along by ensuring that messages are shared with staff and officers in relevant policy areas.

Recommendation: Hold listening and action sessions between the Welsh Government and CJCs focusing on where regions would like to take their CJCs

Encourage CJCs to propose suggestions on how the Welsh Government can empower them to realise their aspirations during these sessions.

Ensure that the conversations are realistic by setting expectations in advance regarding the realm of possibility for government support (i.e. what kinds of monetary or non-monetary support may be feasible?).

Focus group and workshop participants think CJCs can add value beyond their core legal functions. They pointed to possibilities for achieving efficiency gains by sharing local government operations, attracting funding and investing at the regional scale. Identifying and delivering the unique value added to each CJC may require experimentation fostered and supported by the Welsh Government.

Recommendation: Encourage the CJCs to use pilots to experiment with or test new CJC functions and nurture “supported risks” in this experimentation

Encourage the CJCs to propose, design and implement pilots that exhibit good practice for experimentation (including robust, independent monitoring and evaluation).

Signal the Welsh Government’s intention to help CJCs take “supported risks”. This can include proposing potential sources of Welsh Government support that can help the CJCs through the process: expertise, guidance or platforms for sharing.

Strong and simple accountability and robust performance measurement for the CJCs will help them build and maintain the confidence of constituent local authorities and residents. On the one hand, formal lines of accountability between the Welsh Government and CJCs are sometimes considered onerous by local authorities. On the other, there is an appetite for more robust lines of accountability to constituent local authorities and residents to ensure that local governments and citizens have ample information and appropriate opportunities to influence the work of the CJC. Upward and downward lines of accountability for the CJCs could benefit from close inspection. Monitoring and evaluation will support evidence-based decision making and enable organisational learning.

Recommendation: Define accountability frameworks for the CJCs that explicitly set out lines of accountability

Map lines of accountability and the mechanisms that will maintain them, including transparency measures, performance measurement, reporting, control and audit.

Include both formal and informal accountability relationships, recognising that they are dynamic and evolving.

Use the accountability frameworks to start conversations about where different stakeholders wish to have stronger or more formal lines of accountability and where they may prefer to lighten them.

Recommendation: Develop tailored guidance for CJCs on performance evaluation in co‑operation with the CJCs themselves

Reflect the unique functions and goals of the CJCs in the guidance within each of the three areas of the legally required self-assessment:

1. Effective execution of functions: Guidance may, for example, suggest having a limited number of performance metrics that show progress against the statutory functions of the CJCs and present broader outcome indicators on the regional scale (e.g. development outcome indicators). Guidance should also extend to monitoring and evaluating the impact of their legally required plans, for example based on outcome targets established by the CJCs in collaboration with the local authorities and Welsh Government.

2. Economical, efficient and effective resource use: Guidance could, for example, suggest polling constituent local authority officials on their satisfaction with CJC resource use.

3. Governance: Guidance may, for example, suggest that members of CJC sub-committees provide feedback on satisfaction with the implementation of accountability mechanisms (to the CJC board, stakeholders and citizens), internal and external communications and mechanisms for dialogue between the Welsh Government and local authorities.

While guidance can help the CJCs have a similar baseline of self-assessment to enable cross‑comparison, it also builds flexibility to tailor self-assessment to any unique arrangements or functions a CJC adopts.

Provide examples of how the CJCs can translate performance evaluation into organisational learning, such as maintaining a dashboard of key performance indicators that is shared and discussed regularly within the CJC.

Emphasise the importance of regular, informal internal performance checks (using, for example, the OECD capacity-building toolkit for the CJCs).

References

[14] Aldag, A., M. Warner and G. Bel (2020), “It depends on what you share: The elusive cost savings from service sharing”, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, Vol. 30/2, pp. Pages 275–289, https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muz023.

[20] Andrews, L. (2015), Written Statement - Voluntary Mergers: Update on Expressions of Interest Received, https://www.gov.wales/written-statement-voluntary-mergers-update-expressions-interest-received.

[25] Audit Wales (2023), Corporate Joint Committees - Commentary on their progress, https://www.wao.gov.uk/publication/corporate-joint-committees-commentary-their-progress.

[19] BBC (2015), Dismay at council merger rejections by Leighton Andrews, https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-politics-30999047.

[12] Bel, G. and M. Mur (2009), “Intermunicipal cooperation, privatization and waste management costs: Evidence from rural municipalities”, Waste Management, Vol. 29/10, pp. pp. 2772-2778, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2009.06.002.

[51] Betteley, C. (2023), Dire warnings on Ceredigion council’s finances, https://www.cambrian-news.co.uk/news/politics/dire-warnings-on-ceredigion-councils-finances-636630.

[41] Bradford, N. (2017), Flexible governance and adaptive implementation, https://www.oecd.org/cfe/regionaldevelopment/Bradford_Canadian-Regional-Development-Policy.pdf.

[42] Browne Jacobson LLP (2021), Guide to the model Welsh Local Authority constitution, https://democracy.newport.gov.uk/documents/s20885/Constitution%20Guide%20-%2030.12.21.pdf?LLL=0.

[37] Cardiff Capital Region Cabinet (2022), Report of CCR city deal director and head of governance, policy and communications, https://www.cardiffcapitalregion.wales/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/item-4-abp.pdf.

[6] CoE/UNDP/Open Society LGI (2010), Inter-municipal cooperation: Toolkit manual, https://rm.coe.int/imc-intermunicipal-co-operation/1680746ec3.

[24] DataMapWales (2016), Local Authorities, https://datamap.gov.wales/layergroups/inspire-wg:LocalAuthorities.

[52] Evans, R. (2023), “Leaked letter: Conwy is teetering on the edge of bankruptcy”, North Wales Pioneer, https://www.northwalespioneer.co.uk/news/23973626.leaked-letter-conwy-teetering-edge-bankruptcy/.

[15] Frère, Q., M. Leprince and S. Paty (2014), “The impact of intermunicipal cooperation on local public spending”, Urban studies, Vol. Vol. 51/8, pp. pp. 1741-1760,, https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098013499080.

[49] Future Generations Commissioner for Wales (2023), Public Services Boards, https://www.futuregenerations.wales/work/public-services-boards/.

[38] House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee (2019), City Deals and Growth Deals in Wales, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201919/cmselect/cmwelaf/48/48.pdf.

[8] Hudson River Watershed Alliance (n.d.), Intermunicipal Watershed Agreements, https://hudsonwatershed.org/intermunicipal-watershed-agreements/.

[36] Isle of Anglesey County Council (2021), Establishing the North Wales Region’s Corporate Joint Committee (CJC), https://democracy.anglesey.gov.uk/ieIssueDetails.aspx?IId=15043&PlanId=0&Opt=3.

[16] Kortelainen, M. and et al (2019), “Effects of healthcare district secessions on costs, productivity and quality of services”.

[17] Metro-Dynamics (2020), Subnational Bodies: Lessons Learned from Established and Emerging Approaches, https://static1.squarespace.com/static/55e973a3e4b05721f2f7988c/t/5f50da669dee334f6ac50e7c/1599134325947/Subnational+bodies+-+Lessons+learned+from+established+and+emerging+approaches+-+Final+version+28.07.20.pdf.

[9] Morgan, M. et al. (2023), “Inter-municipal cooperation and local government perspectives on community health and wellbeing”, Australian Journal of Public Administration, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8500.12597.

[7] Muraoka, T. and C. Avellaneda (2021), “Do the networks of inter-municipal cooperation enhance local government performance?”, Local Government Studies, Vol. 47/4, pp. 616-636, https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2020.1869545.

[35] OECD (2023), “OECD CJC action plan workshops”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[34] OECD (2023), “OECD stakeholder interviews”, Unpublished, OECD, Paris.

[39] OECD (2023), Regions in Industrial Transition 2023: New Approaches to Persistent Problems, OECD Regional Development Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5604c2ab-en.

[3] OECD (2022), Regional Governance in OECD Countries: Trends, Typology and Tools, OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4d7c6483-en.

[11] OECD (2022), Shrinking Smartly in Estonia: Preparing Regions for Demographic Change, OECD Rural Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/77cfe25e-en.

[55] OECD (2020), Policy Framework on Sound Public Governance: Baseline Features of Governments that Work Well, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c03e01b3-en.

[4] OECD (2020), The Future of Regional Development and Public Investment in Wales, United Kingdom, OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e6f5201d-en.

[40] OECD (2018), Rethinking Regional Development Policy-making, OECD Multi-level Governance Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264293014-en.

[5] OECD (2014), OECD Council Recommendation on Effective Public Investment across Levels of Government, https://www.oecd.org/effective-public-investment-toolkit/.

[54] Plaid Cymru (2022), Arfor and the Valleys, https://www.partyof.wales/2022_arfor_cymoedd_arfor_valleys.

[50] Powys County Council (2023), Draft Budget, https://en.powys.gov.uk/article/13837/Draft-Budget.

[10] Rayle, L. and C. Zegras (2012), “The emergence of inter-municipal collaboration: Evidence from metropolitan planning in Portugal”, European Planning Studies, Vol. 12, pp. 867-889, https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2012.722932.

[53] River Severn Partnership (n.d.), About, https://www.riversevernpartnership.org.uk/about/.

[57] Senedd Business (2023), Minutes of the Economy, Trade, and Rural Affairs Committee meeting 13/09/2023, https://record.senedd.wales/Committee/13472.

[26] Senedd Cymru (2021), Local Government and Elections (Wales) Act 2021, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asc/2021/1/part/5/chapter/5/enacted.

[18] Senedd Research (2021), Reforming Local Government, https://research.senedd.wales/research-articles/reforming-local-government/ (accessed on 5 October 2023).

[21] Senedd Research (2018), Public Service Reform in Post-devolution Wales: A Timeline of Local Government Developments, https://senedd.wales/media/e2laky1h/18-050-web-english.pdf.

[13] Struk, M. and E. Bakoš (2021), “Long-term benefits of intermunicipal cooperation for small municipalities in waste management provision”, Int J Environ Res Public Health, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041449.

[45] UK House of Commons (2019), City Deals and Growth Deals in Wales, https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201919/cmselect/cmwelaf/48/48.pdf.

[31] Wales Statutory Instruments (2021), The Mid Wales Corporate Joint Committee Regulations 2021, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/wsi/2021/342/part/4/made.

[30] Wales Statutory Instruments (2021), The North Wales Corporate Joint Committee Regulations 2021, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/wsi/2021/339/part/3#commentary-key-54013ccd58ddbcc35335270559a3e8ab.

[28] Wales Statutory Instruments (2021), The South East Wales Corporate Joint Committee Regulations 2021, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/wsi/2021/343/contents/made.

[29] Wales Statutory Instruments (2021), The South West Wales Corporate Joint Committee Regulations 2021, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/wsi/2021/352/schedule/made.

[46] Welsh Government (2024), Regional Skills Partnerships, https://businesswales.gov.wales/skillsgateway/skills-development/regional-skills-partnerships.

[43] Welsh Government (2023), “Information provided by the Welsh Government”, Unpublished.

[32] Welsh Government (2023), Regional transport plans: guidance for Corporate Joint Committees, https://www.gov.wales/regional-transport-plans-guidance-corporate-joint-committees.

[27] Welsh Government (2022), Corporate Joint Committees: Statutory Guidance, https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2022-01/corporate-joint-committees.pdf.

[48] Welsh Government (2022), Regional Partnership Boards (RPBs), https://www.gov.wales/regional-partnership-boards-rpbs.

[23] Welsh Government (2022), Written Statement: The role of Corporate Joint Committees, https://www.gov.wales/written-statement-role-corporate-joint-committees.

[2] Welsh Government (2021), Draft Statutory Guidance: Establishment of the Corporate Joint Committees, https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/consultations/2021-07/corporate-joint-committees-draft-statutory-guidance.pdf.

[47] Welsh Government (2021), Local Health Boards, https://law.gov.wales/public-services/health-and-health-services/local-health-boards.

[58] Welsh Government (2021), Performance and governance of principal councils: Statutory guidance on Part 6, Chapter 1, of the Local Government and Elections (Wales) Act 2021, https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2021-03/performance-governance-of-principal-councils.pdf.

[22] Welsh Government (2020), Consultation Document: Regulations to establish Corporate Joint Committees (CJCs), https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/consultations/2020-10/consultation.pdf.

[44] Welsh Parliament (2023), Record of a meeting of the Senedd Economy, Trade, and Rural Affairs Committee, https://record.senedd.wales/Committee/13472.

[1] Welsh Statutory Instruments (2021), Local Government and Elections (Wales) Act 2021, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asc/2021/1/data.xht?view=snippet&wrap=true.

[33] Welsh Statutory Instruments (2021), The Child Poverty Strategy (Corporate Joint Committees) (Wales) Regulations 2021, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/wsi/2021/1364/made/data.xht?view=snippet&wrap=true#f00004.

[56] Wrexham.com (2022), “Warning North Wales CJC will ‘suck powers away from the six local authorities’”, Wrexham News, https://www.wrexham.com/news/warning-north-wales-cjc-will-suck-powers-away-from-the-six-local-authorities-213905.html.

Notes

← 1. For councils, the decision maker may be either the executive leader or elected mayor as applicable, although Wales currently has no local authorities led by mayors. For the national parks, this individual can be either the chairperson, deputy chair or chair of a national park planning committee.

← 2. Or “sub-committee” in the case of the CJCs.