This chapter describes the governance arrangements in the National Mining Agency through the lens of the OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy: The Governance of Regulators. The section provides a brief definition of each of the seven principles and offers a detailed description of the actions that ANM has taken to comply with each one of them. The chapter also includes a subsection on the steps that the Agency has taken to foster administrative simplification and reduce red tape.

Regulatory Governance in the Mining Sector in Brazil

4. Performance of the internal governance of the National Mining Agency

Abstract

Governance of the mining sector in Brazil

The governance of the mining sector in Brazil has changed significantly in recent years. In 2017, Law No. 13.575/2017 created the National Mining Agency, an autarchic institution with the mandate to regulate mining activities, grant mining titles and perform inspection and enforcement actions. Although the Agency was established legally in 2017, it became operational in December 2018 (Decree No. 9.587/2018). The Agency replaced the former National Department of Mineral Production (DNPM), an administrative division linked to the Ministry of Mines and Energy, which, along with the Ministry of Mines and Energy, had been the governing body of the sector since 1960. The need to modernise and restructure the mining regulator and to revitalise the sector were some of the main drivers for the replacement of the DNPM.

This chapter describes the governance arrangements of the newly created National Mining Agency using as framework the seven principles set by the OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy: The Governance of Regulators (see Box 4.1). Furthermore, it describes the efforts that ANM has deployed to reduce the administrative burdens that mining operators face and that hinder the performance of the Agency.

Box 4.1. Seven OECD Best Practice Principles for the Governance of Regulators

1. Role clarity. An effective regulator must have clear objectives, with clear and linked functions and the mechanisms to co-ordinate with other relevant bodies to achieve desired regulatory outcomes.

2. Preventing undue influence and maintaining trust. Regulatory decisions and functions must be conducted with the upmost integrity to ensure that there is confidence in the regulatory regime. There need to be safeguards to protect regulators from undue influence.

3. Decision making and governing body structure. Regulators require governance and decision making mechanisms that ensure their effective functioning, preserve their regulatory integrity and deliver the regulatory objectives of their mandate.

4. Accountability and transparency. Business and citizens expect the delivery of regulatory outcomes from government and regulatory agencies, and the proper use of public authority and resources to achieve them. Regulators are generally accountable to three groups of stakeholders: i) ministries and the legislature; ii) regulated entities; and iii) the public.

5. Engagement. Good regulators have established mechanisms for engagement with stakeholders as part of achieving their objectives. The knowledge of regulated sectors and the businesses and citizens affected by regulatory schemes assists to regulated effectively.

6. Funding. The amount and source of funding for a regulator will determine its organisation and operations. It should not influence the regulatory decisions and the regulator should be enabled to be impartial and efficient to carry out its work.

7. Performance assessment. It is important that regulators are aware of the impacts of their regulatory actions and decisions. This helps drive improvements and enhance systems and processes internally. It also demonstrates the effectiveness of the regulator to whom it is accountable and helps build confidence in the regulatory system.

Source: OECD (2014[1]), The Governance of Regulators, OECD, Paris, France, https://doi.org/10.1787/23116013.

Role clarity

The role clarity principle refers to one of the main characteristics that independent regulators should have in order to achieve their objectives effectively. It implies that the regulator’s goals and attributions are defined clearly, are not conflicting among them, and are stated formally in the legislation. The agency’s scope of action and area of influence, especially in newly created regulators, should be understandable for other public institutions, regulated parties, and the public. The latter helps stakeholders keep the regulator accountable for its actions and prevents other entities from overstepping in their relation with the regulator.

It is important that regulatory agencies have adequate resourcing to discharge its responsibilities effectively. If the regulator is forced to prioritise specific objectives because it does not have enough resources to comply with all of them, these trade-offs should be disclosed to stakeholders. In these cases, activities related to regulatory compliance shall remain high in the list of priorities of the regulator and try to allocate staff and funding to them (OECD, 2014[2]).

Moreover, the regulatory framework that underpins the operations and responsibilities of the regulator should define co-ordination mechanisms between the regulatory agency and other bodies. Co-operation with other entities of the public administration helps identify and address regulatory gaps and overlaps, and fosters better public policy outcomes. Collaboration across institutions allows for the streamline of processes, reduces administrative burdens and promotes a more efficient use of the regulator’s resources.

This subsection will tackle the role clarity principle in the National Mining Agency from two angles: its objectives and functions and the co-ordination mechanisms in place.

Objectives and functions

In 2017, the National Mining Agency replaced the former National Department of Mineral Production, having as one of its objectives promoting access and rational use of the mineral resources of the Union in a socially, environmentally and economically sustainable way. ANM is an autarchic institution1 linked to the Ministry of Mines and Energy, it has legal personality, owns assets and is entitled to receive revenues to carry out activities of the public administration that require, for its better functioning, a decentralised financial and administrative management. The law of creation of ANM (Law No. 13.575/2017) and the Law of Regulatory Agencies (Law No. 13.848/2019) lay the attributions and means by which the Agency should fulfil its objectives. ANM’s responsibilities include those under the former DNPM’s remit as well as attributions inherent to regulatory agencies. Furthermore, the Mining Code (1967) and its bylaw (Decree No. 9.406/2018) underpin ANM’s scope of action concerning mineral substances. ANM is the entity responsible for the implementation of the mineral policy in the country and its functions can be grouped under six headings.

1. Regulatory attributions: The Agency defines regulations, standards and conditions for the use of mineral resources, the performance of inspection and enforcement activities. Moreover, it decides on mineral rights and on the delimitation of areas for public utility.

2. Management attributions: ANM manages the mineral record and registration of title deeds and mining rights and regulates the information exchange on mining operations among the authorities and entities of the Union, the States, the Federal District, and Municipalities.

3. Financial attributions: ANM regulates, inspects and collects two kinds of royalties, the Financial Compensation for the Exploration of Mineral Resources and the Annual Tax per Hectare.

4. Emission of grants, titles and certificates: ANM concedes exploration permits for all mineral substances and grants mining concessions for a specific group of minerals (for a detailed list, see Table 4.1). Additionally, the Agency grants the Kimberley Process Certificate for diamond exploration.

5. Supervision attributions: The agency is responsible for the inspection of all mining operations and for the adoption of precautionary measures in case of non-compliance of safety, technical and financial regulations.

6. Promotion and support: ANM is responsible for fostering economic competition among agents in the mining sector and provide technical support to the MME in matters of mineral policy and to the Economic Defence Management Board (CADE) in matters of antitrust policy.

Table 4.1. Minerals under ANM’s remit for mining concessions

|

Mineral substances |

|---|

|

Gravel, sand and clay for immediate use in civil construction, in the preparation of aggregates and mortars, provided that they are not subjected to an industrial refining process, nor are they used as raw materials for the transformation industry |

|

Rocks and other mineral substances, when equipped for cobblestones, guides, gutters, fence posts |

|

Clays for various industries |

|

Ornamental and cladding rocks |

|

Calcium and magnesium carbonates used in various industries |

Note: The MME grants mining concessions for all other mineral substances, which include iron ore, gold, aluminium (Bauxite), among others.

Source: Law No. 6.567/1978 and Law No. 13.575/2017.

The creation of a regulatory agency for the mining sector in Brazil is a step that has been welcomed by a wide range of stakeholders in the country. However, some key actors are still in the process of embracing completely the role of ANM and the changes brought with it. The foundation of ANM means that a new working and regulatory culture is being developed, and as such, interactions between key actors are expected to evolve.

In particular, the review team identified that some administrative areas inside ANM and other public entities have yet to modified its working practices to reflect the new governance arrangements, where the Board of Directors of the Agency is the main decision-making body in terms of regulation for the mining industry. It is important that ANM’s regional units, the Ministry of Mines and Energy, and other key actors in the sector, understand and respect the role, independence, and governance framework that underpin the operation of ANM.

Furthermore, another factor that hinders the Agency’s ability to discharge its functions effectively is the lack of adequate resourcing, particularly in terms of staff. Although the Agency is working with the Dom Cabral Foundation to assess its organisational structure and identify areas for improvement, and upgrade its leadership; since its creation ANM has been forced to make trade-offs between its functions. The following sub-section will describe the Agency’s organisational structure, its main characteristics and opportunity areas.

ANM’s organisational structure

An adequate human resources structure is a necessary condition to ensure that regulatory agencies can discharge their responsibilities efficiently and effectively. ANM inherited the former DNPM’s organisational structure. Already in 2016, the National Department had workforce constraints, with only 76% of the positions covered and the last civil servant exam taking place in 2010 (Tribunal de Contas da União, 2019[3]).

The complex baseline situation was further reinforced by the budgetary restrictions in place at the time of creation of the ANM. A ceiling on new hires and the impossibility to equate the monetary compensation for officials working in the ANM with that of other regulatory agencies in the country have further limited the room for manoeuvre of the Agency in terms of its staff. In addition, there are concerns in place regarding the large share of the Agency’s workforce that is close to retirement (38% of staff) and the lack of exams to join the Agency as a civil servant. The last exam took place in 2010 and, given the current economic situation, the Federal government has restricted the number of new exams. These situations have increased the risk that the Agency will not be able to fill the existing and potential vacancies.

Staff under-resourcing is a problem salient in most administrative areas of the Agency; however, it is especially acute in matters related to economic competition and antitrust. While ANM is responsible for fostering economic competition in the mining sector in Brazil, it has not been able to perform its duties regarding this topic as it lacks the staff with the relevant expertise. Another particularly sensitive topic is the Agency’s capacity to fulfil its inspection and enforcement activities successfully. After the accidents of Mariana (2015) and Brumadinho (2019), reports from the National Court of Accounts highlighted the need to strengthen the number of inspectors of tailings dams (see Box 4.2 for a detailed list of the recommendations by the National Court of Accounts) (Tribunal de Contas da União, 2016[4]), (Tribunal de Contas da União, 2019[5]). Initial efforts have taken place and the Agency has opened 40 temporarily vacancies for tailings dams’ inspectors (a significant increase from the original 16 officials). Increasing the number of inspectors is a step in the right direction.

Box 4.2. Recommendations from the National Court of Accounts to the National Mining Agency

The TCU recommends ANM to:

Evaluate its internal processes to identify opportunity areas for the streamlining and optimisation of procedures using ICT tools in order to allocate human capital more efficiently.

Identify and classify the existing risks. Optimise the allocation of human resources by prioritising the inspection and enforcement resources on the most relevant risks.

If after adopting the previous measures, there is still a need to adapt the Agency's human resources, submit to the Ministry of Economy a reasoned study on the need personnel, which the Court has repeatedly recommended since 2011.

Source: Tribunal de Contas da União (2020[6]), Relatório de Acompanhamento: Estruturação da Agência Nacional de Mineração.

One way to tackle the resourcing issues is the mobility of staff across public institutions and across administrative units of ANM. In this regard, the Ministry of Economy published the Ordinance No. 282/2020 that encourages staff mobilisation from regulatory agencies and public institutions to improve the allocation of the workforce. In this framework, ANM has benefited from 16 additional civil servants through the movement of staff from other institutions. Additionally, the National Mining Agency is in the process of pooling its staff in the regional offices such that workers are allocated where they are needed the most. This project is still in its pilot stage and it aims at harnessing the use of ICT tools and the new management structure derived from the transition from the former DNPM to the ANM in order to encourage the creation of a national-wide team of officials.

The creation of a new agency is necessarily accompanied by a transition and adjustment period, particularly in the case of ANM, where the previous governance arrangements had been in place for over 40 years. ANM is moving towards a regulatory agency that makes decisions based on evidence and, while there has been resistance by some areas, this change is welcome and encouraged by a wide range of stakeholders. To foster this new culture in the mining regulator, it is important to engage with the staff to intensify the communication of the new working culture of ANM, foster feedback loops and collaboration across different areas of the Agency.

Additionally, it will be necessary to make certain that ANM has the adequate number of staff with the appropriate expertise and competences to fulfil all of the Agency’s obligations. The latter requires that ANM’s leaders have a “broader range of tools, such as mentoring, coaching, networking, peer learning, and mobility assignments to promote learning as a day-to-day activity integrated into the jobs of civil servants” (OECD, 2017[7]) (see Box 4.3 for a list of principles that the OECD promotes for a fit-for-purpose public service). The National School of Public Administration (Escola Nacional de Administração Pública, ENAP) can be an important ally for the ANM. ENAP not only has the infrastructure in place to offer trainings and courses, but also has a leadership competency model that builds on international practices and is transversal to the public sector (OECD, 2019[8]). Even if the ENAP does not have in place specific trainings on mining activities, it is possible to create tailor-made programmes, which ANM could harness to increase the skillset of the officials in the Agency. In fact, in 2019 the National School offered a training course on Dams Safety, with a specific section on mining dams. Moreover, ICT tools offer the possibility to disseminate training opportunities and to increase their reach to regional offices.

Box 4.3. OECD Recommendation on Public Service Leadership and Capability

Values-driven culture and leadership

Define the values of the public service and promote values-based decision-making

Build leadership capability in the public service

Ensure an inclusive and safe public service that reflects the diversity of society

Build a proactive and innovative public service that takes a long-term perspective in the design and implementation of policy and services

Skilled and effective public servants

Continuously identify skills and competences needed to transform political vision into services which deliver value to society

Attract and retain employees with the skills and competences required from the labour market

Recruit, select and promote candidates through transparent, open and merit-based processes, to guarantee fair and equal treatment

Develop the necessary skills and competences by creating a learning culture and environment in the public service

Assess, reward and recognise performance, talent and initiative

Responsive and adaptive public employment systems

Clarify institutional responsibilities for people management

Develop a long-term, strategic and systematic approach to people management based on evidence and inclusive planning

Set the necessary conditions for internal and external workforce mobility and adaptability to match skills with demand

Determine and offer transparent employment terms and conditions that appropriately match the functions of the position

Ensure that employees have opportunities to contribute to the improvement of public service delivery and are engaged as partners in public service management issues.

Source: OECD (2019[9]), Recommendation of the Council on Public Service Leadership and Capability, https://www.oecd.org/gov/pem/recommendation-on-public-service-leadership-and-capability-en.pdf.

Additional to the staff and central structure of the Agency in Brasilia, the organisational structure of ANM encompasses 25 regional offices, which are in charge of inspection and enforcement activities in the territory under their supervision. These units are fundamental to navigate the challenges that factors such as the Agency’s broad range of attributions, the characteristics of the sector and the territorial extension of the country pose for the implementation of the mineral policy in Brazil.

Although these units have been under the central management hierarchy since the time of the DNPM, they had a de facto autonomy (Tribunal de Contas da União, 2019[3]). The latter led not only to heterogeneity in the interpretation and application of the regulation by each regional unit, but also to a politicisation of the positions, undermining the credibility and transparency of the Agency. For an adequate performance of the Agency, it is necessary that all the staff clearly understands the objective of the institution and their role in attaining it.

Relationship with the Ministry of Mines and Energy

ANM co-ordinates with its parent ministry, the Ministry of Mines and Energy, for the granting of concession titles of certain mineral substances and participates on the elaboration of policy initiatives such as the Mining and Development Programme (Programa de Mineração e Desenvolvimento). Additionally, the MME offers guidance and oversees ANM’s performance.

The mineral sector would benefit from additional efforts to have more streamlined and integrated processes for titles granting. Given the allocation of responsibilities between the MME and the ANM, the concession of exploitation rights can take up to 30 days once the request reaches the MME, which evaluates the dossier prepared by the Agency. Before the creation of the ANM, the MME was in charge of approving exploitation concessions for all mineral substances. Currently, the National Mining Agency is responsible for the assessment and granting of mineral exploration permits for all mineral substances and for the approval of the exploitation concession for a specific subset of substances (see Table 4.1 for a complete list). In the case of all other minerals, it is the Ministry of Mines and Energy the institution that grants the exploitation permits.

Additionally, ANM has participated in the design of key policy documents for the mining sector in Brazil. In 2020, the MME presented the Mining Development Programme 2020-2023, which aims at enhancing growth in the sector by defining ten pillars with over 110 goals to be achieved. Some of these goals relate directly to the structure, operation and management of ANM.

Co-ordination mechanisms

This subsection will assess ANM’s co-ordination mechanisms from two lenses: co-ordination with other agencies and institutions and co-ordination across levels of government. In Brazil, the design and implementation of regulations that relate to the mining sector have federal and sub-national components. Mineral, environmental, safety and labour regulations are managed by different institutions, and, in several cases, there are overlaps of attributions. Co-ordination across institutions and government levels is key to ensure that safety, environmental and health risks are managed efficiently. There are opportunity areas to improve the collaboration among entities and thus, unlock benefits from better co-ordination, collaboration and data exchange.

Information and high-quality data are important elements to facilitate collaboration across government institutions. Brazil has defined a Digital Government Strategy 2020-2022 (Estratégia de Governo Digital), which aims at ramping up the use of information and ICT tools to have an integrated government where agencies share and use data to inform decisions and to simplify the interactions with stakeholders. This adds to the efforts that the Brazilian government has taken to foster the development, standardisation, and integration of information across the Federal administration since 2011 (Decree No. 7.579/2011). At the moment of preparation of this Review, ANM made available several data sets on the Brazilian Open Data Portal (dados.gov.br), in particular; the Annual Hectare Tax (TAH) and the Financial Compensation for Mineral Exploration (CFEM), the Process Control (SICOP) and the Brazilian Mineral Yearbook.

Co-ordination with other institutions

Regulatory Agencies in Brazil have taken steps towards better collaboration. The Law of Regulatory Agencies (Law No. 13.848/2019) dictates the conditions for the articulation amongst agencies in the country, fostering the elaboration of joint regulations and the development of committees to exchange experiences and information with the objective of creating guidance and common procedures (art. 30). One example of the latter is the Network for the Articulation of Regulatory Agencies (Rede de Articulação das Agências Reguladoras, RADAR), which provides a space for sharing information, knowledge and experiences. RADAR is composed by the 11 autarchic regulatory agencies in Brazil.

Nevertheless, ANM would benefit from improving its co-ordination mechanisms with other agencies and entities that also regulate the mineral sector from an environmental, public health or labour safety perspective (e.g. IBAMA, Special Secretariat for Social Security and Labour, ANVISA, state environmental agencies, amongst others). The Law of Regulatory Agencies explicitly encourages the collaboration between environmental protection institutions and regulatory agencies; however, co-ordination actions between ANM and IBAMA are still at an early stage and are not systematic. These efforts have focused on the reduction of administrative burdens for regulated parties. Given the broad number of agencies that have attributions related to mining activities and the relevance of the topics that they cover (e.g. national defence, environment, indigenous rights, and territorial aspects among others), co-ordination is key to ensure a smooth delivery of the regulation. In particular, several stakeholders identified the licensing process to start a mining operation as burdensome. Joint efforts to improve regulatory delivery are necessary to ensure better levels of compliance while keeping red tape at bay (see Box 4.4 on the co-ordination between regulators in Australia).

Regarding the availability and exchange of geological data in the country, ANM, the MME and the Brazilian Geological Survey have signed a Technical Cooperation Agreement to build an integrated geological database. The objective is to aggregate in a single place geoscientific information, data collected from mining operations and from the activities carried out by CRPM. While this initiative is at an early stage, it is a first step to tackle the restrictions to information exchange (e.g. legal and confidentiality limitations) that are in place and that hinder the use of evidence for the development of the mining sector.

Box 4.4. Co-ordination arrangements in the Australian mining sector

Mining and environmental regulation in South Australia

The Mineral Resources Division and the Environment Protection Authority (EPA) of South Australia have signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) in order to “achieve consistent, collaborative and efficient environmental regulation of South Australia’s mineral resources, especially when the obligations and responsibilities of the parties overlap”.

The MoU defines the responsibilities, actions and co-ordination mechanisms between both agencies regarding licensing, inspection and enforcement activities, incident reporting, and communication and response actions to environmental incidents. Additionally, it states that both parties should be engaged in each other’s development of policies and regulations to ensure a better application and implementation.

Source: Department of Energy and Mining (2013[10]), Administrative Arrangements, https://www.energymining.sa.gov.au/minerals/mining/mining_regulation_in_south_australia/administrative_arrangements (accessed 27 May 2021).

Co-ordination across levels of government

Co-ordination across levels of government is an area of great complexity given the federal nature of Brazil. Realities in each state differ greatly, which makes it harder for some sub-national governments to keep abreast of all the regulatory reforms and requirements dictated at the national level. Moreover, state and municipal regulations are not homogeneous, increasing administrative burdens for mining operators working in different jurisdictions. In particular, state environmental regulators play a key role for the mineral sector in Brazil, as they perform enforcement activities, which can overlap with those carried out by IBAMA or other federal authorities, including those of ANM. This means that regulators and regulated parties devote a significant amount of resources to implement and comply with the legislation. In fact, it can take businesses up to 10 years to fulfil all the requirements imposed by the Brazilian public administration to open a mining operation.

As part of the efforts to improve the co-ordination across levels of government, the National Mining Agency published Resolution 71/2021 to sign technical co-operation agreements between the Agency and sub-national administrations. These agreements will focus on the inspection of mining activities and the collection of the CFEM. Sub-national administrations that would like to engage in this kind of co-operation must comply with certain conditions, mainly referring to the availability of technical teams and would have to work hand-in-hand with the administrative units of the Agency.

ANM and a wide range of stakeholders are aware of the positive impact that it would have in the industry and in the work stream of state and municipal authorities if mineral procedures would be seen as a single process in which several institutions co-ordinate and collaborate, and as such it should be streamlined and standardised as much as possible.

Preventing undue influence and maintaining trust

The appropriate governance arrangement for a regulator depends on many factors, including on the regulated sector, the characteristics of the players in the market (particularly if state-owned enterprises and private parties are involved), and on the interest groups and impacts of its regulatory decisions (OECD, 2012[11]). Regardless of the institutional setup, upholding public confidence and generating impartial, justifiable regulatory decisions are key to independent regulators. These characteristics mitigate risks (or perceived risks) regarding the regulator’s operation and integrity and foster a better perception by the regulated parties, the ministry and the public (OECD, 2014[2]). A high degree of independence should be accompanied by transparency and accountability mechanisms that prevent the undue influence of specific interest groups and ensure the implementation of evidence-based regulatory decisions.

The Law of creation of ANM defines the National Mining Agency as an independent regulator, linked to the Ministry of Mines and Energy. As such, its regulatory decisions, operation and management of resources are shielded from the influence of the parent ministry. The change in the location of the mining regulatory body in Brazil, from a government office linked the Ministry of Mines and Energy to a regulator at arm’s length responds to a need to have a regulator that is objective of ensuring regulatory certainty and foster trust and the attractiveness of the mining industry. ANM has taken steps that aim at improving the actual and perceived transparency of the Agency and that prevent undue influence in the rule-making process.

Use of evidence for decision-making

ANM’s working culture is moving towards one where decision-making is based on evidence. The Agency has taken steps to implement regulatory impact analysis (Análise de Impacto Regulatório, RIA) to inform its regulatory decisions and has open the rule-making process to stakeholders. Moreover, the Agency has produced documents and has participated in capacity-building activities to encourage the uptake and systemic used of RIA as a tool to assess the potential impacts of regulations. For instance, the Guidelines for the Elaboration of Regulatory Impact Analysis (Análise de Impacto Regulatório, Manual de Elaboração) define the criteria and methodologies for the two types of RIA institutionalised at ANM. The two approaches differ on the level of depth of the assessment and are proportional to the significance of the regulation. At the time of preparation of this report, ANM had published four RIAs for public comments (see Table 4.2). The RIAs that the technical areas of ANM prepare are subject to comments from stakeholders, both inside and outside the Agency. Additionally, the Agency is closing the feedback loop for the elaboration and modification of regulations by establishing an ex post evaluation five years after a regulatory disposition is enacted.

Table 4.2. RIAs elaborated by ANM

|

Topic |

Stakeholder engagement activities |

Public consultation period |

|---|---|---|

|

Waste rock and tailings exploitation |

Public consultation |

45 days |

|

Certification of the Emergency Action Plan for Mining Dams |

Public consultation |

45 days |

|

Public declarations |

Targeted consultation |

|

|

Brazilian System of Mineral Resources and Reserves |

Public consultation |

30 days |

|

Compliance in telemetry systems to monitor mineral water mining |

Public consultation |

45 days |

Note: The table refers to the RIAs elaborated by Jun, 2021.

Source: ANM (2021[12]), Regulação, https://www.gov.br/anm/pt-br/assuntos/regulacao (accessed 21 June 2021).

As mentioned above, the National Mining Agency has in place two kinds of regulatory impact assessment based on the scope and expected impacts of the regulatory proposal. The Level II RIA incorporates all the elements considered in the Level I RIA, as well as a more detailed assessment of the impacts of the proposed regulation and additional elements to substantiate the final regulatory decision. Below are specified the contents of both types of RIA.

Level I RIA:

Identification of the public policy problem

Identification of the affected groups and stakeholders

Identification of the legal framework that grants the Agency the attributions to introduce or modify the regulatory disposition

Definition of the public policy objectives

Definition of regulatory and non-regulatory alternatives

Impact assessment

Implementation strategies, including monitoring and inspection activities

An analysis of the contributions received through stakeholder engagement activities

Level II RIA:

All the elements considered in Level I RIA

Impact assessment (in the case of significant regulations, this section should include a quantitative assessment of the impacts – methodologies such as cost-benefit analysis, multi‑criteria analysis, cost analysis or cost-effectiveness analysis are encouraged)

International experiences in the subject

Assessment of the potential impacts of the alternatives identified on the service consumers or users and on the most affected groups

Risk-analysis

The legal framework that underpins the Agency’s operation supports the use of evidence for decision‑making. The Law of Regulatory Agencies (Law Nº 13.848/2019), the Law of Creation of ANM (Law No. 13.575/2017), and the Law of Economic Freedom (Law No. 13.874/2019) and its Decree (Decree No. 10.411/2020) lay the obligation to perform regulatory impact analysis for the modification and emission of regulatory dispositions. Information availability is key to increase the adoption of informed decisions and to ensure the elaboration of high-quality RIAs. At the moment of elaboration of this report, ANM had over ten different information systems that hindered the exchange of information and cross-checking of data.

Maintaining trust in the Agency’s senior management

The rules for the appointment of the Board of Directors of the Agency are explicitly stated in the regulatory framework that supports ANM’s operation. Although the President nominates the Directors of ANM, the terms of appointment of the members of the Board are not linked to the electoral cycle. The latter shields the Agency from the political context in the country and fosters independence. Besides, the Directors’ terms are staggered to avoid losing expertise and ensure a smooth transition between boards.

Additionally, ANM has already in place mandatory cooling-off periods and restrictions to avoid conflicts of interest, which strengthen the level of trust that stakeholders have on the Agency and on the Board members. Directors are prevented from engaging on businesses or offering services within the mining sector and should wait at least for six months after the termination of their activities in ANM to take up a position in a regulated enterprise.

Decision making and governing body structure for independent regulators

The composition, attributions and accountability arrangements that underpin the governing body in a regulatory agency have a significant influence in the regulator’s ability to discharge its responsibilities effectively and independently. ANM’s decision-making body follows a governance board model, which is in charge of administrative and operational activities, approval of regulatory matters and strategic planning, among others. While this structure grants lower possibility of capture and benefits from a wider range of perspectives and experiences, it is important to ensure de jure and de facto independence and integrity (OECD, 2014[2]). This section will focus on the regulatory framework that governs the Collegiate Board of ANM and the actions that the Board has taken to foster transparency.

Appointment, employment conditions and termination of board members

The process and regulations that support the appointment, employment conditions and termination of board members and senior management should protect the regulator’s independence and restrict the actual or perceived risks of regulatory capture.

ANM’s Collegiate Board comprises a Director General and four Directors. The Director General represents the presidency of the Agency and has the casting vote over the board’s decisions, which must be approved via absolute majority. The Law of Regulatory Agencies (2019) dictates the general characteristics of the managing bodies of regulatory agencies, including that of ANM. The President of the Republic appoints the members of the Board, which the Senate ratifies. Mandates are non-coincidental, for five-year periods and with no possibility of renewal. When ANM was established, its Law of Creation assigned the following serving terms to its first Board: the Director General (4 years), two Directors (3 years) and two Directors (2 years). The directors that will replace the first Board will be subject to the scheme set up by the Law of Regulatory Agencies.

The legislation states the criteria to appoint members of the Collegiate Board; however, they are general to all regulatory agencies covered by Law 13.848/2019. Additional to having the academic attestations for the position, Directors of the Board must comply with at least one of the following conditions (Art. 42, Law 13.848/2019):

Have at least ten years of experience in the public or private sector in an activity related to that of the regulatory agency or a similar activity or have at least four years in one of the following positions:

Director or higher management in a company in the sector regulated by the agency

Management position (director, manager or adviser) or an equivalent to DAS-42 in the public sector

Professor or researcher in the sector regulated by the agency.

ANM has in place arrangements to avoid conflicts of interest and foster integrity among the members of its Collegiate Board. Conflicts of interest are managed through specific provisions in the law of creation of the National Mining Agency (Law No. 13.575, art. 9 and art. 10). These regulations restrict the possibility of appointment as member of the Collegiate Board to candidates linked to political positions and of people engaged and/or linked to entities regulated by ANM. Additionally, members of the Board have explicit prohibitions in regarding their political, professional, and financial activities and their interactions with regulated parties.

Accountability and transparency

Independent regulatory agencies are expected to be accountable to three groups of stakeholders: ministry and legislature, regulated entities, and the public (OECD, 2014[2]). Fostering a culture of transparency is key to enhance trust and confidence by stakeholders and to delimitate their expectations regarding the regulator’s performance. Regulatory agencies with greater independence from the ministry should ensure higher transparency and accountability standards to reduce actual or perceived risks of misconducts (Durand and Pietikäinen, 2020[13]). Moreover, actions such as making publicly available information on the decision-making process, operation and measures taken to promote compliance and enforcement of regulations, are steps in the right direction to boost transparency and to encourage relevant parties to scrutinise the performance of the regulatory agency.

To foster the regulator’s accountability to the ministry and legislature it is important that all parts have a clear definition of the goals and objectives for the regulated sector. In this sense, a parallel process where the government defines and makes explicit its expectations of the regulator and the regulator explains how it will fulfil them on its strategic planning can strengthen the accountability arrangements in place. To complement this process, independent regulators should report periodically (usually, this is done annually) to the legislature and ministry on the status of its activities and outcomes based on the sector’s policy.

Transparency in decision-making is key to convey trust in the regulatory process. This includes the publication of data and evidence used, as well as the rationale behind a specific decision. In this sense, engaging the public and regulated entities throughout the regulatory cycle makes the acceptance of regulatory and enforcement measures smoother. Furthermore, enabling formal complaint channels and appeals mechanisms that are easily accessible to the general public and regulated entities are necessary to prevent the regulator from overstepping its attributions and to challenge its actions.

The Law of Regulatory Agencies (Law No. 13.848/2019), which requires the Agency to prepare an annual report to the Congress and to the National Court of Accounts (Tribunal de Contas da União, TCU) and to have an ombudsman underpins specific accountability arrangements in ANM. The annual report compares the Agency’s compliance with the mineral policies dictated by the Ministry of Mines and Energy and assesses the level of compliance of the Agency’s Strategic Plan and the Annual Management Plan. On the other hand, the office of the ombudsman elaborates a monthly report (and an annual one as well), where it details the characteristics and statistics of the complaints, requests for information, and feedback, among others, that stakeholders present to the Agency. The report also mentions the actions taken to address the complaints.

ANM is fostering regulatory certainty and transparency by publishing a regulatory agenda with the list of regulations to be drafted or modified during the next biennium. The agenda for the period 2020/2021 is the result of an extensive consultation exercise that gathered inputs from ANM’s administrative areas and regional offices, from public sector stakeholders and from regulated parties. The topics are prioritised using a Matrix GUT (Gravity-Urgency-Tendency), and are approved by the Collegiate Board (see Table 4.3 for a complete list of the topics and subtopics covered in the Regulatory Agenda 2020/2021). Furthermore, the guidelines available describe all the steps for the elaboration of the regulatory agenda, as well as the responsibilities of each administrative area involved in the process. The Superintendence of Regulation and Regulatory Governance oversees compliance with the objectives of the regulatory agenda and monitors three indicators: compliance of the regulatory agenda, elaboration of RIAs, and regulatory predictability (ANM, 2020[14]).

Table 4.3. Main topics and subtopics of the regulatory agenda 2020/2021

|

Main topic |

Subtopic |

|---|---|

|

Transversal or cross-cut |

Conflicts due to mining activities |

|

Availability of areas |

|

|

Mining titles as colateral for financing |

|

|

Alternative means to solve conflicts |

|

|

Sustainability |

Mine closure |

|

Financial guarantees or insurance to cover the risks arising from mining activities |

|

|

Waste reuse |

|

|

Research |

Standardization and evaluation of aerophotogrammetry products |

|

Brazilian System of Certifications of Resources and Reserves |

|

|

Production |

Certification of Dams |

|

Kimberley Certification |

|

|

Withdraw of the requirement/waiver of mining titles |

|

|

Inspections and CFEM |

Inclusion of new substances in the reference value system |

|

Auxiliary Electronic Note for mineral goods – artisanal mining* |

|

|

Bylaw of Law No. 13.540/2017** |

|

|

National cadastre for first acquirement of mineral goods from artisanal mining |

|

|

Mineral Water |

Actualisation of the Ordinance No. 374/2009*** and Technical Bylaw-Mineral Water |

|

Compliance in telemetry systems to monitor mineral water mining |

* Refers to permissão lavra garimpeira; ** Law No. 13.540/2017: Amends Laws No. 7 990, of 28 December 1989, and 8 001, of 13 March 1990, to provide for Financial Compensation for the Exploration of Mineral Resources (CFEM); ***Ordinance No. 374/2009: Technical Norm on the Technical Specifications for the Use of mineral, thermal, gas, table water.

Source: Resolution No. 20, 3 December 2019 and Resolution No. 45, 3 September 2020.

The regulatory agenda feeds into ANM’s culture of using evidence for decision-making, which also includes the introduction of a RIA system for the elaboration of regulatory proposals or the modification of existing rules. The Collegiate Board uses the results from the RIA to inform its decisions, and while the outcomes from the assessment are not binding, the Board is required to justify regulatory decisions that contradict the RIA. The fact that the highest decision-making body in the Agency has endorsed the use of data and a robust methodology to inform its decisions is in line with the OECD Best Practice Principles on Regulatory Impact Assessment (see Box 4.5 for a complete list of the principles).

Box 4.5. OECD Best Practice Principles on Regulatory Impact Assessment

1. Commitment and buy-in for RIA: Political commitment as well as the existence of frameworks that foster the integration and implementation of RIA are key to ensure its adoption by stakeholders.

2. Governance of RIA – having the right set up or system design: RIA should be part of the regulatory governance cycle and take into consideration the administrative conditions and culture of the country or organisation. The governance of RIA should be accompanied by a clear definition of the attributions and responsibilities of each party and the establishment of an oversight body with an adequate mandate and resources.

3. Embedding RIA through strengthening capacity and accountability of the administration: Civil servants responsible for the elaboration of RIAs should have access to adequate guidelines, training and capacity building activities. Moreover, the implementation of accountability and performance-oriented arrangements help define specific actors responsible as well as evaluation schemes.

4. Targeted and appropriate RIA methodology: RIA should not be seen as an additional bureaucratic task by civil servants. As such, it should be flexible while keeping in place core elements such as the definition of the public policy, objectives and regulatory (and non-regulatory) alternatives.

5. Continuous monitoring, evaluation and improvement of RIA: It is important that data requirements are defined early in the regulatory design stage, this will allow for the definition of monitoring and evaluation regulations. The results from ex post evaluations of regulations are useful inputs that can inform future ex ante RIAs.

Source: OECD (2020[15]), OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy: Regulatory Impact Assessment, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Among the actions implemented by ANM to increase transparency, the Collegiate Board is currently live streaming its meetings. The sessions are open to the public through the Agency’s YouTube channel, where stakeholders can participate and see the deliberation process. Streamed meetings take place once a week; however, the Board can meet by request and these reunions are not publicly available. During meetings with stakeholders of the mining sector, they highlighted the positive changes brought by the increase in transparency in decision-making.

Finally, ANM gathers, consolidates and publishes industry-related data. The Agency makes publicly available statistics on investments, mineral production, reserves modification, royalty collection (e.g. CFEM and TAH) by month, mineral and process. Additionally, ANM’s portal allows stakeholders to consult information on dams, their risk category, volume, class, among others. Although figures on both topics are easily accessible through ANM’s web portal, they are not available in user-friendly formats, making its management and processing by third parties difficult and burdensome. The National Mining Yearbook (Anuário Mineral Brasileiro) is another source of information on the mining industry. It gathers statistics on mineral reserves, production, mining operations, royalty collection, mining titles and international trade, mainly focusing on the most relevant metallic substances (from the lens of value production) (ANM, 2020[16]). At the moment of elaboration of this report, ANM was working to improve the disclosure of information using Business Intelligence initiatives.

Engagement

Engagement with all relevant stakeholders is key to ensure that regulatory agencies fully understand the realities of the groups affected or benefited by their policies. By consulting with regulated parties and members of the public, regulators are able to gather inputs and knowledge to inform decisions and, thus, achieve better outcomes and a smoother adoption of the regulations (OECD, 2012[11]). In particular, consultation mechanisms should be transparent and formal to avoid favouring a specific group and to encourage a wider range of contributions. This will improve credibility and legitimise the actions by the regulator (OECD, 2014[2]).

The National Mining Agency has taken steps towards the development of a culture that fosters stakeholder engagement and transparency in decision-making. This change has been welcomed by a significant number of stakeholders, as before the creation of the Agency, there were limited opportunities for key actors to take part on the elaboration of rules and policies.

Public consultations and public hearings are part of ANM’s rule-making process. Currently, engagement with relevant actors is done through different channels—their usage varies according to the topic, methodology and objective of the consultation. The Law of Creation of ANM and the Law of Regulatory Agencies dictate that engagement with stakeholders is required as part of the tasks that ANM should undertake before the enactment or modification of regulatory provisions. Public consultations and hearings tend to take place before the definition of the preferred regulatory proposal and for a minimum period of 45 days (Resolution by ANM No. 43/2020). Stakeholders are able to provide comments and feedback to the RIA and supporting material (such as preliminary studies). The comments received by ANM are publicly available through a comments matrix that includes ANM’s reaction to the inputs.

Besides public consultations on specific regulatory matters, ANM has also established other communication channels with its stakeholders. The tomadas de subsídio allow Directors or the administrative areas of ANM to invite the public or specific stakeholders to provide comments on specific matters (for instance, reduction of the regulatory stock). During these processes, the Agency may provide technical data, relevant documents or other materials as background information to encourage the reception of feedback from the relevant actors. Box 4.6 shows how stakeholders were engaged in the reform process of the mining regulations in South Australia.

Box 4.6. Stakeholder engagement in the Australian mining sector

Department of Energy and Mining, South Australia

In 2016, the Department of Energy and Mining (DEM) of South Australia embarked in a major revision of the main mining regulations in the state with three central objectives in mind (Department for Energy and Mining, 2020[17]):

Streamlining of the regulatory process for exploration a mining activities

Increase transparency, enforcement and compliance

Introduce modern environmental enforcement in which rehabilitation is done in line with government approvals

A key result from this reform exercise was the amendment of the Statutes Amendment (Mineral Resources) Act in 2019. As such, in 2020 the DEM carried out an extensive consultation with stakeholders on the draft regulations that derive form the update of the Mineral Resources act, namely the draft Mineral Regulations, the draft Opal Mining Regulations, and the draft Mines and Works Inspection (Mine Manager) Variation Regulations.

Stakeholders were informed in advance of the consultation process. The DEM used different communication channels (e.g. social media, posters, targeted emails, and the Department’s website) to ensure that the information reached all the relevant stakeholders in a timely and adequate manner. The public consultation extended for 6 weeks and, during that time, the DEM engaged with stakeholders through webinars, queries, and emails, among others. Given the scope of the regulations under consultation, the DEM grouped them in three overarching topics. Each bundle was set for public consultation along with guidance material and explanatory and supporting documents. The three groups of regulations were:

Land access, exploration licences and mineral claims

Compliance and enforcement, including the mining register, royalties and financial issues, opal mining, and mining managers

Operating approvals

The feedback received during the consultation led to changes being introduced to the draft regulations.

Source: Department for Energy and Mining, (2020[17]), Mining Regulations Consultation Report, https://www.energymining.sa.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/375008/Mining_Regulations_Consultation_Report.pdf (accessed 10 June 2021).

ANM has deployed several strategies to engage with the largest number of stakeholders as possible. The Agency uses social media platforms and its website to encourage participation in the scheduled consultations, which can take place through digital means and/or physical meetings. Since parties regulated by ANM vary broadly in size, resources available and location, the most effective channel so far has been the digital one.

Funding

Adequate funding, in terms of the amount and source of the resources, is an important element for the correct functioning of a regulatory agency. Suitable resourcing allows regulators to fulfil their objectives, to offer competitive conditions to staff members and to diminish the influence from the sector ministry and other actors. The sources of the regulator’s funding should be legally defined and be in line with its needs, which include investment, programmes and day-to-day operations (OECD, 2017[18]). Moreover, the regulator’s budget should be negotiated on a multi-year basis to ensure its protection from external influences and to encourage medium and long-term planning and investments.

The legislature ought to avoid threatening factors to the regulatory agency’s financial independence such as budget appropriations. Restraining the amount of resources available based on the political or economic context in the country might be detrimental for the regulator’s performance, especially if this is done on a year-to-year basis. If budget appropriations are necessary and justifiable, it is recommendable to pre-define a period (say, two years) where the limitations would be applied. It is important to emphasise that the legislature or the relevant body determining these financial restrictions should explain the rationale behind these measures and be as transparent as possible in the budget negotiation process.

At the time of creation of ANM, it was agreed that the new regulator would have the same budget as the former DNPM, despite the fact that the agency’s functions were broader. The DNPM was already facing financial constraints (Tribunal de Contas da União, 2014[19]), which were further aggravated when the oversight of the sector was transferred to the Agency (Tribunal de Contas da União, 2020[6]). These conditions have limited ANM’s de facto ability to comply with all of its objectives and has incurred in trade-offs, as certain functions have been prioritised (for instance, inspections of tailings dams) over others.

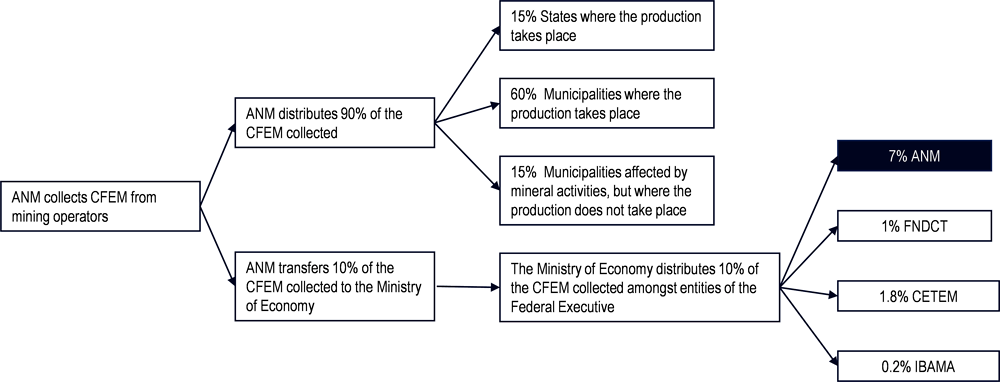

Although the legislation grants the National Mining Agency with the financial resources to fulfil its objectives, actions have been taken to restrict the amount of funds allocated to it. Article 19 of the Law No. 13.575/2017 defines ANM’s funding structure and sources of revenue, being the Financial Compensation for Mineral Exploration (CFEM) the most relevant one (see Box 4.7 for a complete list of ANM’s revenue sources). The CFEM is levied on projects that are on the exploitation phase and is collected from private agents by ANM. The Agency distributes the resources from mining royalties among several institutions and sub-national governments (see Figure 4.1), including the Federal government who then is responsible for approving the budgetary envelope for ANM. While ANM is entitled to 7% of the CFEM that it collects, in reality it has received only a fraction of this budget allocation, approximately 3% of the total CFEM collected. On the other hand, ANM is entitled to the resources that it collects from selling or renting property under its ownership. A modification in the auctioning process (now it is done online) has helped improve the revenues collected using this system and during the first three of these auctions, the Agency collected approximately BRL 237 000 000.

Given that the Agency’s funding is negotiated on a yearly basis, it has been difficult for ANM to carry out long-term investments as there is uncertainty regarding the next period’s budget. This is an issue that has been acknowledged by a wide range of stakeholders in the sector, and while the economic context of the country is of great importance, it should not hinder the performance of a regulatory agency. One avenue to tackle this situation (at least in part) could be the definition of multi-year funding needs that build on ANM’s Strategic Plan 2020-2023 (ANM, 2020[20]). This could help the Agency plan long-term investments (such as those aimed at improving its technological capacities) and would protect its financial independence from government expending ceilings or restrictions like the ones in place since 2019. Financial limitations have also affected the Agency’s workforce, as salaries are not competitive in comparison to the private sector, or event, to other regulatory agencies in Brazil. In this regard, the Board of Directors of ANM as well as the Ministry of Mines and Energy have expressed their concerns to the Ministry of Economy, which is the institution that elaborates the proposed budget law for the year.

Box 4.7. Revenue sources for ANM

The product of credit operations conducted in the country and abroad

The sale of publications, resources from inspections and surveillance services or those from seminars and courses

The Annual Tax per Hectare (TAH)

Resources from agreements or contracts concluded with public or private parties

Donations, bequests, subsidies and other resources intended for them, including donations of assets and equipment intended for the ANM, for the purpose of compensation for damage caused by misuse of mineral resources due to illegal mining.

Allocations consigned to the Union’s overall budget, special credits, transfers, loans

Resources from the sale or rental of moveable or immovable property under their ownership

The product from auctioning off the assets and equipment found or seized stemming from illegal mining operations

7% of the amount collected as Financial Compensation for Mineral Exploration (see Figure 4.1 for a complete diagram of the allocation of CFEM across entities in the mining sector).

Figure 4.1. Distribution of CFEM collected from regulated parties

Note: ANM: National Mining Agency (Agência Nacional de Mineração); FNDCT: National Fund for Scientific and Technological Development (Fundo Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico); CETEM: Centre of Mineral Technology (Centro de Tecnologia Mineral); IBAMA: Brazilian Institute of Environment and Natural Renewable Resources (Instituto Brasileiro do Meio Ambiente e dos Recursos Naturais Renováveis).

Source: Law No. 8.001/1990 and Law No. 13.575/2017.

As mentioned above, the total amount of funds that ANM receives through the Annual Budget Law (Lei Orçamentária Anual, LOA) is variable and uncertain. The Federal government can allocate resources aimed to regulatory agencies to its Contingency Reserve, a fund meant to help balance the national’s budget. As shown in Table 4.4, in 2020 approximately 41% of the resources that were originally granted to ANM through the LOA were transferred to the Contingency Reserve, significantly reducing the scope of manoeuvre of ANM. While the budgetary restrictions in the country generate limitations in several regulatory agencies, ANM is a newly created agency that inherited a structure that requires significant investments to meet the expectations of the sector and the public regarding its performance. The monetary constraints also impact ANM’s ability to improve its equipment and technological tools, which the Agency needs to streamline its processes and improve its operation. ANM has received donations from third parties (mainly the private) to offset the limitations in terms of technological equipment and software; however, this practice may lead to perceived or actual risks of capture and should not be seen as a permanent solution to ANM’s financial constraints.

Table 4.4. Budgetary distribution, National Mining Agency

Brazilian Reais

|

|

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Total income (LOA) |

974.947.314 |

615.484.239 |

562.094.899 |

|

Contingency reserve |

627.075.697 |

257.819.031 |

233.643.405 |

|

Income received by ANM |

347.871.694 |

357.819.031 |

328.451.494 |

Note: Income received by ANM = Total income (LOA) – Contingency reserve. It is important to mention that the National Mining Agency can receive additional credits by the Ministry of Economy, which increase the amount of funds for the Agency.

Source: Câmara dos Deputados (2021[21]), LOA – Lei Orçamentária Anual, https://www2.camara.leg.br/orcamento-da-uniao/leis-orcamentarias/loa (accessed 8 March 2021).

Performance evaluation

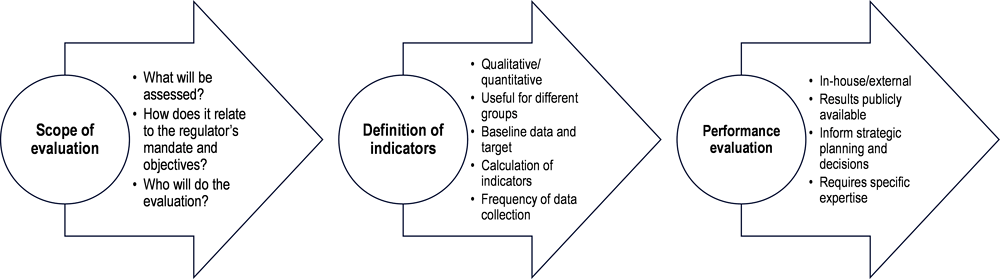

Assessing a regulatory agency’s performance against a set of goals is important to foster continuous learning and improvement (OECD, 2014[2]). To ensure a sound evaluation system, it is essential that regulators plan evaluations in advance, define their scope and resource allocation. It is important to define indicators and monitoring activities, which will provide qualitative and quantitative inputs to carry out the performance assessment of the regulator. Finally, staff and higher management should not see evaluations as a critique on their work, but as a tool that sheds light on the opportunity areas and as an instrument that fosters trust and transparency. Figure 4.2 shows some of the key aspects that a regulatory agency should bear in mind when carrying out a performance evaluation. Results from evaluations should be made publicly available in user-friendly formats that allow stakeholders to consult them and hold accountable the agency.

Figure 4.2. Key aspects of performance evaluation

Source: (Vági and Rimkute, 2018[22]), Toolkit for the preparation, implementation, monitoring, reporting and evaluation of public administration reform and sector strategies: Guidance for SIGMA partners, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/37e212e6-en.

ANM’s performance and strategic indicators are described in its Strategic Plan (ANM, 2020[20]). The process for the definition of these indicators and the targets included the participation of several administrative and managerial areas of the Agency and were approved by the Collegiate Board. The Strategic Plan describes the targets for the next four years.

The Agency’s performance is assessed through internal and external audit processes. The Internal Audit Unit monitors and assesses organisational processes against goals previously defined. Additionally, it offers guidance on risk management and on the legality of specific actions. The Unit publishes the Annual Plan for Internal Audits (Plano Anual de Auditoria Interna, PAINT), which lists the audits that will take place during the year. The document states the objective of each audit exercise planned for the period and mentions the amount of human resources and human hours that will be allocated to a given audit. Finally, ANM has elaborated a manual that specifies the technical elements that internal auditors should consider when carrying out their duties.

The Federal Court of Accounts (Tribunal de Contas da União) is the entity responsible for external audits of ANM. It performs inspections and audits by its own initiative or by request from the Congress. The TCU has assessed and offered recommendations to improve the Agency’s resource structure and its governance arrangements. Additionally, after the tailings dams’ accidents of Brumadinho and Mariana, the Court carried out specific analysis on the DNMP’s and ANM’s management and inspection of these structures (Tribunal de Contas da União, 2016[4]) (Tribunal de Contas da União, 2019[5]).

Administrative simplification in the National Mining Agency

The mineral sector in Brazil has been characterised by high administrative burdens. Red tape hinders the development of the industry and may influence the incentives for regulatory compliance. Putting in place a regulatory system that is clear, predictable and that follows a risk-based approach to its design and implementation could unlock significant benefits for the sector and the country as a whole (see Chapter 1 on the relevance of the mining sector in Brazil). In recent years, ANM and the Federal government have introduced several measures aimed at easing regulatory burdens using regulatory policy tools and digitalisation.

In 2019, the National Mining Agency launched an initiative to review and reduce its regulatory stock with the objective of simplifying requirements and legal dispositions and eliminating obsolete provisions. The project derives from Decree 10.139/2019, which requires regulatory agencies to assess and consolidate the normative acts such as decrees (or lower in the legal system hierarchy). Furthermore, in 2020 ANM opened a public consultation (tomada de subsídios) during two months, to gather the views of stakeholders on the matter and identify priority areas for the reduction of administrative burdens and regulatory guillotine. When implementing burden reduction programmes, the Agency should consider the appropriateness, effectiveness, efficiency and alternatives of the regulatory provisions under scrutiny (OECD, 2020[23]). Repealing regulations should not be an end on itself and must be accompanied by an assessment of the costs and benefits that each provision entails.

An important source of red tape for mining operators is the granting of titles for the exploration and exploitation of mineral resources. Delays have compounded over the years and currently the Agency faces a backlog of 20 000 requests for exploration permits and approvals face delays. Elements such as the lack of a standard management of the petitions, the limited use of ICT tools and the heterogeneity in the interpretation and application of the regulations by ANM’s regional offices, hinder the administrative simplification efforts. It is worth pointing out that the law of creation of the Agency lays down obligations for ANM to increase transparency in administrative processes. One concrete step to tackle these factors is the creation of a working group with officials of the National Mining Agency and the Ministry of Mines and Energy has been created (Ordinance 136/2019) to evaluate and streamline the processes, reduce the response time and get rid of administrative liabilities linked to the granting of mining exploration and exploitation concessions.

Moreover, the Agency is in the process of streamlining its procedure for public tenders, specificially of available areas for mining activities. Through the implementation of a digital system that is user friendly and that promotes transparency, ANM has carried out three public auctions to put back in the market the available areas. Due to failed exploration permits, devolutions, and overdue grants, approximately 56 000 areas have accumulated over the years. The public consultations are livestreamed through the Agency’s YouTube channel have been positively received by stakeholders.

The Agency has underscored the importance this topic and has set goals to cut BRL 1 500 million in regulatory burdens by 2023 (ANM, 2020[20]). To achieve this goal, the Federal government and ANM have introduced several initiatives and regulatory modifications to streamline processes, improve the business environment and increase the uptake of technological solutions. Furthermore, the Decree No. 10.389/2020 approves the integration of mineral projects to the Investment Partnerships Programme, which aims at streamlining processes and licences for projects that involve minerals of strategic interest for the country. Projects that are part of the programme benefit from greater interaction across government agencies, smoothening environmental licensing and other formalities.

Economic Freedom Law and its bylaw

The Economic Freedom Law (Law No. 13.874/2019) represents a turning point in terms of the administrative simplification policy in Brazil, as it considers elements such as risk and proportionality. It was enacted in September 2019 with the objective of “protecting the free initiative and the free conduction of economic operations”. The Law and its Bylaw (Decree No. 10.178/2019) lay down the rules for the implementation of the “silence-is-consent” rule, which grants the automatic approval of low-risk processes in case the authority fails to provide an official response. Agencies are the ones who define the deadlines for each process as well as which processes that are subject to the “silence-is-consent” rule. It is important to underscore that environmental regulations are not subject to the provisions on the Economic Freedom Law.

This law provided the legal support to reduce administrative burdens in ANM by implementing the “silence-is-consent” rule and defining maximum response times for low-risk activities. In line with the latter, in 2020 the Agency enacted the Resolution ANM 22/2020, which lists a set of administrative procedures and their respective maximum processing times. Tangible benefits from this measure include the reduction from 2 years to 34 days in the time it takes ANM to process a research authorisation for those areas that do not overlap with conservation areas, Indigenous reservations, other granted areas, among others.

Digital Protocol

The Digital Protocol is a digital one-stop shop where mining operators can perform administrative formalities and request services from ANM. The Protocol is an important milestone towards the reduction of administrative burdens, as it reduces significantly transaction costs for mining operators and for ANM’s officials. However, the digitalisation of processes should also go hand-in-hand with their simplification and re-engineering, to avoid transferring red tape and inefficiencies to the digital sphere. So far, elements such as the ease of implementation, the low budgetary requirements or fast gains have driven the digitalisation efforts. At the time of preparation of this report, there were 180 procedures available in the portal. See Box 4.8 for more information of the principles that underpin successful one-stop shops in OECD countries.

Box 4.8. Reducing administrative burdens through one-stop shops

Best Practice Principles: One-Stop Shops for Citizens and Businesses

One-stop shops are important tools that can help reduce administrative burdens for regulated parties and for the administration, improve service delivery, and reduce transaction costs. They should be part of a broader administrative simplification strategy and must be centred on the users’ needs to encourage their uptake and unlock all their potential benefits. The OECD has identified 10 specific principles that administrations should follow in order to implement successful and sustainable one-stop shops. The principles are:

1. Political commitment: Long-term political support is critical for the development of one-stop shops. This support should be accompanied by continuous communication and feedback loops between the political and administrative levels to foster the development, implementation and improvement of the one-stop shop.

2. Leadership: Managers of one-stop shops should be clear and committed to the objectives of the one-stop shop and be realistic about their plans and scope. Flexibility and experimentation are key to foster continuous improvement activities.

3. Legal framework: The regulatory framework should allow for co-operation with other agencies to maximise the benefits for users.

4. Co-operation and co-ordination: Communication, co-ordination and feedback between the areas responsible for the design of the one-stop shop and the implementing areas are critical. Systemic engagement between the relevant agencies and with the users is key.

5. Role clarity: Define clear objectives and expectations for the one-stop shop. Gather inputs from users through focus groups, surveys and pilots to tailor the one-stop shop to their needs and experience.

6. Governance: The governance structure should include the high-level participation of all agencies involved in the one-stop shop, this will allow for political commitment. The leading agency of the one-stop shop should be in charge of operative decisions.

7. Public consultation: Gather the users’ perspective through public consultations. Include pilots to test the services and foster feedback loops where the findings of one implementation phase are used to improve the next one.

8. Communication and technological considerations: Take into account the users’ needs and accessibility demands and use the adequate channels and communication methods to benefit users.

9. Human capital: Provide specific training programmes for one-stop shop staff, focusing on technical and interpersonal/social skills.

10. Monitoring and evaluation: Define quantitative and qualitative indicators and evaluation methods that will allow for an assessment of the success of the one-stop shop and encourage its continuous improvement.

Source: (OECD, 2020[24]).

Mining Plan (Plano Lavra)

The Mining Plan (Plano Lavra) addresses some of the challenges imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic on the Agency’s performance and on the mining operators. Its main objective is to de-bureaucratise a series of administrative formalities that regulated parties perform and to improve the business environment. The Plan states 11 key actions, a timeline for their completion and their legal support. For instance, the restrictions for performing in loco inspections due to safety and health limitations triggered the revision of low-risk procedures such as the emission of the Utilisation Guide (Guia de Utilização). Before, an inspection by ANM personnel was a necessary requirement for the approval of the Utilisation Guide, leading to burdensome procedures that did not follow a risk-based approach. It is important that after the COVID-19 pandemic, the Agency carries out an ex post evaluation of the measures put in place, this will provide information into their effectiveness and efficiency.

The case for applying better regulation measures to inspection and enforcement activities

“Inspections are one of the most important ways to enforce regulations and to ensure regulatory compliance”, still it is not possible nor efficient to perform verifications of all the regulated parties in a country (OECD, 2018[25]). Resources should be targeted following transparent and informed criteria in order to achieve better and more efficient public policy outcomes. While in Brazil the National Mining Agency is responsible for the inspection and enforcement of the mineral regulations, other institutions and inspectorates also have a role overseeing regulatory compliance in the mining sector. Inspections and enforcement actions in the mineral sector have been in the spotlight since the accidents of Mariana (2015) and Brumadinho (2019). Therefore, ANM has shifted most of its regulatory enforcement resources to the supervision of tailings dams, leaving other aspects of the mineral operations in the back burner. These trade-offs are to some extent understandable; nonetheless, it is important that the Agency develops and implements a detailed and articulated policy on regulatory enforcement and inspections (see Box 4.9 for a list of 12 principles for better inspection and enforcement activities).

Box 4.9. Better inspection and enforcement activities to ensure higher compliance

OECD Regulatory Enforcement and Inspections Toolkit

Regulatory enforcement and inspection activities are a necessary component of an efficient and high-quality regulatory system. The 12 principles covered in the Toolkit provide a tool for assessing the way an institution is promoting and ensuring compliance with regulations.

1. Evidence-based enforcement: deciding what to inspect and how should be grounded on data and evidence, and results should be evaluated regularly.

2. Selectivity: inspections and enforcement cannot be everywhere and address everything, and there are many other ways to achieve regulations’ objectives.