The objective of regulatory policy is to ensure that regulations and regulatory frameworks are in the public interest. For regulatory policy to be effective, it must have political commitment of the highest level, follow a whole-of-government approach, and have the support of an array of institutions to make this policy work, including oversight bodies. This section provides a preliminary assessment of the current legal and institutional arrangement of the Government of Argentina to pursue a regulatory policy, including any policy statements and programmes that help implement the policy of regulatory quality.

Regulatory Policy in Argentina

Assessment and recommendations

Policies and institutions for regulatory policy

Assessment

Argentina is working to establish the necessary framework for regulatory policy. It has issued several legal instruments to promote the use of regulatory management tools, such as ex ante assessment of draft regulation and stakeholder engagement, amongst others. Additionally, it has practices which contribute to seeking a high-quality regulatory framework, such as oversight on legal quality, and intensive use of information and communication technologies (ICT) tools on internal government processes. Nevertheless, these are efforts which, despite being a step in the right direction, provide an incomplete basis for the adoption of a full-fledged regulatory policy by line ministries and government agencies.

Recently, the Federal Government of Argentina issued a series of legal instruments that seek to promote the use of tools to improve the quality of the regulatory framework. Amongst them, Decree 891/2017 for Good Practices in Simplification issued by the President on November 2017 stands out. The decree establishes a series of principles and tools to improve the rulemaking process in Argentina and the management of the stock of regulation. The decree introduces tools on ex ante and ex post evaluation of regulation, stakeholder engagement, and administrative simplification, amongst others. Nevertheless, no formal oversight mechanisms have been established to supervise the use of these tools across line ministries and government agencies, which make implementation difficult and limit severely the potential to adopt a whole-of-government approach to regulatory policy.1 A whole-of-government policy should provide clear objectives and frameworks for implementation to ensure that, if regulation is used, the economic, social and environmental benefits justify the costs, distributional effects are considered and the net benefits are maximised.

A lack of formal horizontal oversight mechanisms to supervise the use of tools also means that stakeholders cannot be confident in the consistency of analysis, which is critical to establishing stakeholder confidence in the activities of government.

Similarly, Decree 1.172/2003 establishes a series of measures that promote stakeholder engagement in the development and revision of regulations. For instance, it establishes the legal provisions for the elaboration of regulations with public participation (Bylaw for the Participative Drafting of Standards) and legal provisions for the open meetings of regulatory agencies of utilities (Bylaw for Open Meetings of the Regulators of Public Services). There is evidence of recent employment of these instruments, notably in the development of energy regulation related to tariffs. However, the practice does not seem to be used systematically across the government.

In contrast, the practice of supervising the legal quality of instruments is performed extensively, although in a decentralised manner. The obligation for legal scrutiny is established in Law 19.549 of Administrative Procedures. The Legal and Technical Secretariat of the Presidency has to review and challenge the legal texts which are to be signed by the President or the Chief of Cabinet. Similarly, each ministry is responsible for checking the legal quality of instruments of subordinate level to be issued by them.

The Government of Argentina also pursues an active policy on the use of ICT tools which has the potential to reduce administrative burdens significantly for citizens and businesses. The efforts are headed by the Administrative Modernisation Secretariat, which has as objective to establish the internal government process completely digital. For instance, Decree 733/2018 obliges all government processes to be completely digital.

These efforts show that Argentina is working to establish the necessary framework for regulatory policy. However, they represent actions that require further endeavours to establish a full-fledged regulatory policy. See Box 1 for examples of frameworks for regulatory policy in selected OECD countries.

Box 1. Example regulatory policy frameworks in OECD countries

Australia

In Australia, regulation is made at the federal level as well as by the states and territories, in the form of legislation and subordinate legislation and at a local government level as regulations and bylaws.

Australia is recognised internationally for its Deregulation Agenda and governance arrangements, particularly its approach to regulatory impact assessment (RIA). The Australian Government remains committed to improving the quality of its regulation, including minimising the burden of regulation on businesses, community organisations and individuals. The following are the offices that have outstanding tasks in the regulatory policy cycle:

The Whole of Government Deregulation Policy team has been relocated to the Department of Jobs and Small Business following recent government administrative changes; it is responsible for systematic improvement and advocacy across government more generally.

The Office of Best Practice Regulation (OBPR) at the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet reviews the quality of all RIAs and provides advice and guidance during their development, and its final assessment of RIAs is made public on a central register. The OBPR can ask departments to revise RIAs where quality has been deemed inadequate.

The Office of the Parliamentary Counsel is an independent entity which is responsible for scrutinising the legal quality of regulations. Legal scrutiny is also provided by the Senate Standing Committee for the Scrutiny of Bills and the Senate Standing Committee on Regulations and Ordinances for primary laws and subordinate regulations respectively.

The Australian Productivity Commission is an independent research and advisory body. It has evaluated Australia’s regulatory policy system including RIA, regulator performance and ex post evaluations. It has undertaken a number of reviews in specific policy areas or sectors such as consumer affairs, the electricity sector and the labour market.

Canada

In Canada, the process for developing primary laws (acts) and subordinate regulations differs significantly. Subordinate regulations typically elaborate on the general principles outlined in acts and establish detailed requirements for regulated parties to meet.

The requirements for developing acts are outlined in the Cabinet Directive on Law-making. Legislative proposals introduced by the government are brought to cabinet for consideration and ratification, before being drafted and introduced in parliament. This includes documents relating to the potential impact of the proposal. While cabinet deliberations and supporting documents are confidential, a legislative proposal is often the end product of broad prior consultation with interested stakeholders.

The Cabinet Directive on Regulation (CDR) establishes the requirements for developing subordinate regulations. A RIA is mandatory and made public on a central registry, along with the draft legal text. An open consultation is conducted for all subordinate regulations and regulators must indicate how comments from the public were addressed, unless the proposal is exempted from the standard process. The CDR was adopted in 2018, replacing the previous Cabinet Directive on Regulatory Management. The CDR strengthens requirements for departments and agencies to undertake periodic reviews of their regulatory stock to ensure that regulations achieve intended objectives. It also enshrines regulatory co-operation and consultation throughout the regulatory cycle – including engagement with Indigenous peoples – and reinforces requirements for the analysis of environmental and gender-based impacts.

Mexico

In Mexico, since 2000 RIA and public consultation on draft regulation are mandatory for all regulatory proposals coming from the executive. In 2016, Mexico strengthened its RIA process by adding assessments of impacts on foreign trade and consumer rights, which complemented existing assessments on competition and risk. For the last stage of the regulatory policy cycle, since 2012 mandatory guidelines require the use of ex post evaluation of technical regulations, and since 2018 regulations with compliance costs have to be evaluated every five years.

RIA and stakeholder engagement for primary laws only cover processes carried out by the executive, which initiates approximately 34% of primary laws in Mexico. There is no formal requirement in Mexico for consultation and for conducting RIAs to inform the development of primary laws initiated by parliament.

A new General Law of Better Regulation was issued in May 2018. The law sets a very important milestone in the implementation of regulatory policy in Mexico; for instance, it requires subnational governments to adopt key tools such as RIA. Besides modernising the policy, it also established the National System of Better Regulation, specifying the duties and responsibilities of autonomous bodies and state and municipal governments. It is also remarkable that the Judicial and Legislative Powers will now have to register all their formalities in the National Inventory of Formalities, as well as a Citizen Observatory has to be created that will contribute to the oversight of the enforcement of the law.

Following the adoption of the General Law of Better Regulation, Mexico’s oversight body in regulatory policy was transformed into CONAMER to reflect its broadened mandate. This has defined CONAMER’s attributions and mandate, which is to promote transparency in the development and enforcement of regulations and the simplification of procedures, ensuring that they generate benefits that outweigh their costs. Some of CONAMER’s core functions for pursuing a high-quality regulatory framework are: assess draft regulations through RIA, oversee the public consultation process of draft regulation, co‑ordinate and monitor the regulatory planning agenda, promote simplification programmes and review the existing stock of regulations.

Source: OECD (2018[1]), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072‑en; Department of Jobs and Small Business of Australia (2019[2]), Deregulation Agenda, www.jobs.gov.au/deregulation-agenda (accessed on 9 February 2019).

A developed and institutionalised regulatory policy, in addition to contributing to evidence-based decision-making for regulation, can help fight regulatory capture. In light of the rapid rate of reform taking place in Argentine recently, Argentina may be at risk of regulatory capture, as it introduces major structural reforms to its economy in a system that may not offer substantial protection against vocal incumbents lobbying to protect their interests. Good regulatory practices can offer insulation from regulatory capture.

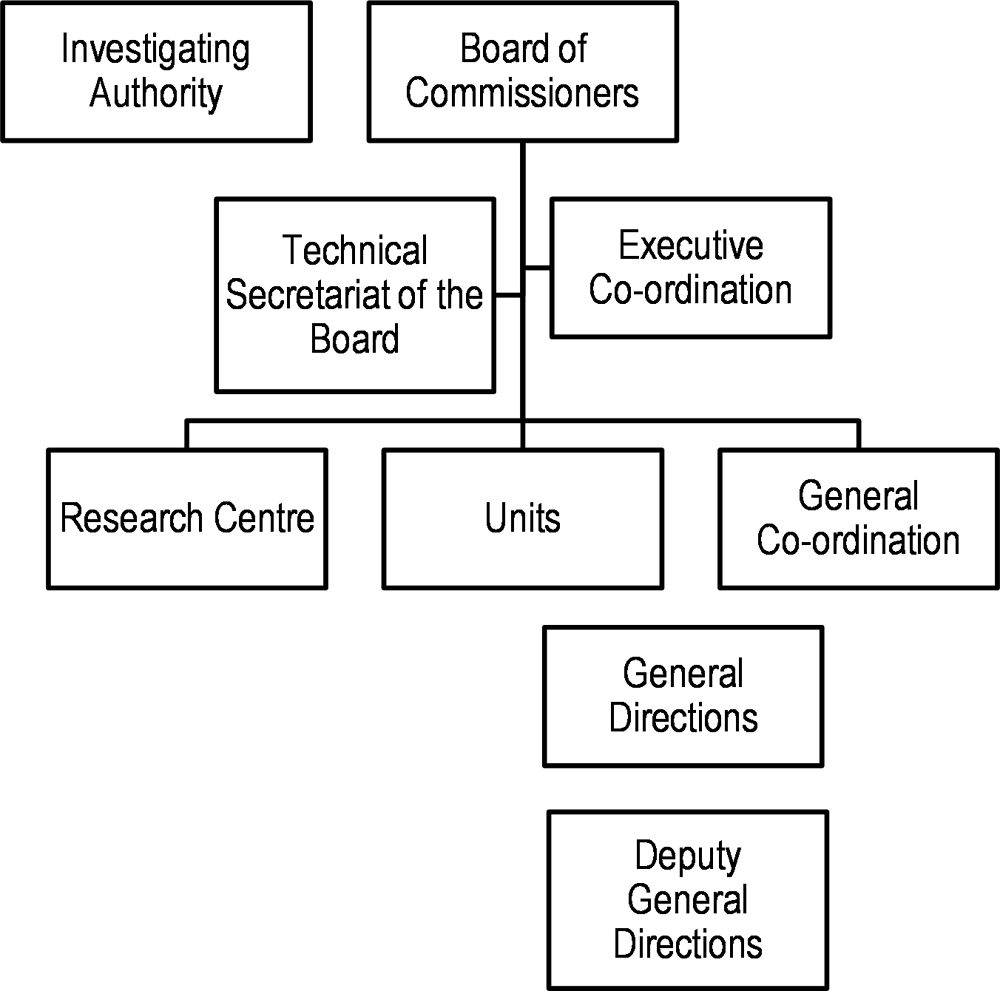

Exerting the policy of regulatory quality is not the responsibility of a single ministry or agency in Argentina. The existing efforts to put regulatory policy into effect are spread amongst three bodies without defined oversight mechanisms, except for focused legal scrutiny. An absence of an articulated whole-of-government responsibility to a given ministry or agency poses challenges in pursuing a co-ordinated approach to regulatory policy in Argentina.

Oversight of legal quality rests in part in the Legal and Technical Secretariat of the Presidency. Its tasks are focused on scrutiny of legal instruments to be signed by the President or Chief of Cabinet, although it is regularly consulted by other ministries for legal texts of a subordinate nature. The Legal and Technical Secretariat has also taken the role to promote and supervise the use of some of the regulatory management tools included in Decree 891/2017 for Good Practices in Simplification, such as ex ante assessment of regulation.

The Administrative Modernisation Secretariat champions the use of ICT in the internal organisation of the government. It also performs the tasks of overseeing that ministries and agencies across the government align and follow the internal regulations established for this objective, such as the employment of the model of electronic management of files and interoperability of databases.

Finally, the Administrative Production Secretariat of the Ministry of Production and Labour also gathers some duties on administrative simplification and has attributions to determine whether certain draft regulations will have an impact on productive (economic) activities. It has established the National Direction of Regulatory Policy in charge of administering an ex ante assessment system of draft regulation coming from the Ministry of Production and Labour for this purpose.

Table 1. Regulatory oversight functions and key tasks

|

Areas of regulatory oversight |

Key tasks |

|---|---|

|

Quality control (scrutiny of process) |

|

|

Identifying areas of policy where regulation can be made more effective (scrutiny of substance) |

|

|

Systematic improvement of regulatory policy (scrutiny of the system) |

|

|

Co-ordination (coherence of the approach in the administration) |

|

|

Guidance, advice and support (capacity building in the administration) |

|

Source: Based on OECD (2012[3]) Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264209022‑en; OECD (2015[4]) Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264238770-en.

It is not uncommon for OECD jurisdictions to have several oversight bodies. In this case, strong, institutionalised mechanisms are a key element to ensure an effective application of regulatory policy. The challenge in Argentina is that responsibilities and roles are not yet clearly defined, which is coupled with the absence of mechanisms of co‑ordination in matters of regulatory policy.2 A whole-of-government approach should ensure a holistic approach to considering the economic, social and environmental impacts. See Table 1 for a categorisation of functions and keys tasks of oversight bodies.

To date, Argentina has chosen to introduce elements of regulatory policy using an advocacy model: to promote the use of some regulatory management tools. While this model has its merits at early stages in the adoption of a policy that promotes regulatory quality, it still requires an agency with clear authority and responsibility for providing whole-of-government regulatory guidance. Moving forward, in order to ensure that regulatory management tools are used effectively across the policy cycle, clear oversight mechanisms are required.

The issuance of Decree 891/17 for Good Practices in Simplification represents one of the first stepping stones for the adoption of regulatory policy in Argentina. Similarly, Decree 1.172/2003 establishes a legal platform to engage with stakeholders in the development of draft regulations and the revision of existing ones.

The focus of the government of Argentina has been to promote the use of the regulatory policy tools established in both decrees by line ministries and government agencies, but without establishing official mechanisms to supervise their application, even though the use of many of these tools is mandatory. This suggests that the Government of Argentina has opted for a model of advocacy on regulatory policy.

At the early stages of the implementation of regulatory policy, an advocacy model has the advantage of avoiding that the adoption of practices to promote regulatory quality becomes a burden for the government as a whole. Agencies which are suddenly obliged to perform additional tasks to their everyday activities, such as preparing a cost-benefit analysis for draft regulation, or seek simplification strategies, may resist in adopting these practices. Instead, in an advocacy model, champions on regulatory policy may emerge within the government and their efforts can be scaled up: agencies which adopt a specific tool effectively and realised that these tools actually made its core activity of regulating more effective. The emergence of champions may facilitate the adoption of the tools by other agencies.

The question in Argentina is the lack of a clear strategy for advocacy to promote the implementation of regulatory policy tools across line ministries and other government agencies. Although the role of advocacy has fallen in practice to the Legal and Technical Secretariat of the Presidency, it does not have an official whole-of-government mandate to do so to promote the several regulatory policy tools available.3 This limits the effectiveness of the model, as this office has limited scope in the use of tools and resources at its disposal to perform the function of providing guidance and advocacy, such as informational campaigns, preparation of supporting materials such as manuals or guides, design and delivery of capacity building exercises, ongoing support for regulators in the use of the tools, amongst others.

Finally, in order to reap the full benefits of having an evidence-based decision-making process which leads to a regulatory framework of high quality, an advocacy model has to evolve to one with strong oversight, in which there is an agency effectively supervising that the tools to promote regulatory quality are effectively employed by line ministries and agencies.

In the international sphere, efforts to benefit from foreign and international experience remain limited. Argentina co-operates with selected partner countries, such as Brazil, and participates in a number of regional and international platforms. Several Economic Co‑operation Agreements signed by Argentina, such as with Canada, Mexico and the United States, have specific chapters on regulatory improvement policy. Also, punctual efforts for harmonisation and mutual recognition in sectoral regulation exist. However, the fruits of these co-operation efforts are not systematically embedded into domestic rulemaking. Consideration of international standards is not an explicit obligation in the development of regulation at the national or the subnational level. Furthermore, co-operative efforts are scattered, escaping a horizontal strategy to contribute to Argentina’s national development objectives.

Currently, there is no obligation to consider or reference international standards when in the Argentinian rulemaking process, except for a handful of agencies such as the energy regulators where there is an explicit mandate to consider international standards for technical and economic regulation. Regarding technical regulation, they are revamping the system where they envisage considering international standards. See Box 2 for examples from Australian and the United S on the consideration of international standards in domestic rulemaking.

Regarding regional fora, Argentina is part of the Southern Common Market (MERCOSUR)4 and leads the technical regulation commission where there are efforts to harmonise regulation. Argentina is also part of the Latin American Integration Association (ALADI).

Recommendations

Argentina should aspire to have an articulated and fully-fledged regulatory policy which brings together institutions, public policies and government actions aimed at increasing regulatory quality into a single coherent framework.

As part of this policy, Argentina should aim at establishing the regulatory policy group, in which the current agencies and offices with responsibilities on the promotion of regulatory quality are included. Argentina should seek to grant legal status and a legal mandate to the regulatory policy group.5

The regulatory policy in Argentina should seek to establish a well-defined and transparent co‑ordination mechanism for the members of the regulatory policy group.

Also, as part of this regulatory policy, Argentina should define the regulatory tools and practices that are the priorities on this policy in order to make them compulsory for the National Public Administration.

Box 2. How is the need to consider international standards and other relevant regulatory frameworks conveyed in Australia and the United States?

In Australia, there is a cross-sectoral requirement to consider “consistency with Australia’s international obligations and relevant internationally accepted standards and practices” (Council of Australian Governments-COAG Best Practice Regulation). Wherever possible, regulatory measures or standards are required to be compatible with relevant international or internationally accepted standards or practices in order to minimise impediments to trade. National regulations or mandatory standards should also be consistent with Australia’s international obligations, including the GATT Technical Barriers to Trade Agreement (TBT Standards Code) and the World Trade Organization’s Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS) Code. Regulators may refer to the Standards Code relating to ISO’s Code of Good Practice for the Preparation, Adoption and Application of Standards. However, OECD (2017[5]) reports that to support greater consistency of practices, the Australian government has developed a Best Practice Guide to Using Standards and Risk Assessments in Policy and Regulation and is considering an information base on standards (both domestic and international) referenced in regulation at the national and subnational level.

In the United States, the guidance of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) on the use of voluntary consensus standards states that “in the interests of promoting trade and implementing the provisions of international treaty agreements, your agency should consider international standards in procurement and regulatory applications”. In addition, Executive Order 13609 on Promoting International Regulatory Co-operation states that agencies shall, “for significant regulations that the agency identifies as having significant international impacts, consider, to the extent feasible, appropriate, and consistent with law, any regulatory approaches by a foreign government that the United States has agreed to consider under a regulatory co-operation council work plan”. The scope of this requirement is limited to the sectoral work plans that the United States has agreed to in Regulatory Co-operation Councils. There are currently only two such councils, one with Canada and the other with Mexico.

Source: OECD (2018[6]), Review of International Regulatory Co‑operation of Mexico, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264305748‑en; OECD (2017[5]), International Regulatory Co‑operation and Trade: Understanding the Trade Costs of Regulatory Divergence and the Remedies, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264275942-en.

The regulatory policy should also allocate oversight duties clearly across the members of the regulatory policy group for the range of regulatory tools to implement.

International Regulatory Co-operation (IRC) can help reinsert Argentina in the global economy. Argentina should seek to perform a more profound mapping and review of its IRC practices. This IRC review should help, amongst others, to: i) enhance IRC practices by ministries and regulators or by the government as a whole, such as bilateral and regional agreements or agreements with international organisations, with the objective to adopt international practices in the national regulation; and ii) embed systematically an IRC component in the domestic rulemaking process, including in technical regulation.

Ex ante assessment of regulation and public consultation

Improving the evidence base for regulation through an ex ante (prospective) impact assessment of new regulations is one of the most important regulatory tools available to governments. The aim is to improve the design of regulations by assisting policymakers to identify and consider the most efficient and effective regulatory approaches, including broader economic impacts, relevant science and various alternatives (e.g. the non‑regulatory alternatives), before they make an evidence-based decision. Additionally, a process of communication, consultation and engagement which allows for public participation of stakeholders in the regulation-making process as well as in the revision of regulations can help governments understand citizens’ and other stakeholders’ needs and improve trust in government. This section addresses Argentina´s practices in ex ante assessment of regulation and will discuss the actions that Argentina undertakes to engage with stakeholder in the process of rulemaking.

Assessment

Argentina has established several elements for an ex ante assessment of draft regulation: legal scrutiny, technical analysis, cost-benefit analysis, and basements of draft regulation on the productive sector. However, they are not integrated into a standardised procedure, and the cost-benefit analysis is only at the stage of early introduction.

For the elaboration of new regulation, the ministries and public administration bodies in Argentina usually carry out two different types of analysis to justify the decision to issue a new regulation. There is the legal report, in which the analysis that has to be made to determine the legal coherence with the current regulatory framework, as well as the legal feasibility. The legal basis for the legal report is in Law 19.549 of Administrative Procedures. The other analysis is the technical report, which includes all the information considered to provide the technical justification for the regulatory proposal.

However, there is a lack of a systematic standardised procedure to carry out both reports, which has resulted in a diversification of criteria for their preparation, as well as wide differences in their content. In some technical reports, legal arguments are employed to provide technical justification, which could also generate a possible duplication in the information. In most cases, the technical report also includes a budgetary impact analysis to determine the fiscal viability of the regulatory project.

Additionally, Decree 891/2017 for Good Practices in Simplification introduced the inclusion of cost-benefit analysis in the elaboration of draft regulation, although there is no whole-of-government formal oversight body providing guidance on the expectations for impact assessment and to supervise their effective implementation. Additionally, there seem to be limited capabilities amongst public officials to perform this assessment.

The Ministry of Production and Labour issued Resolution 229/2018 which obliges all offices and agencies belonging to this ministry to submit an impact report along with their draft regulation to the Productive Simplification Secretariat. This secretariat examines the report and the draft regulation in order to define whether the draft regulation addresses a legitimate public policy problem, and whether the costs of the regulation are justified with the expected benefits, and whether it complies with the precepts on regulatory quality established in Decree 891/2017 for Good Practices in Simplification. Draft regulations which are non-compliant are returned, although the opinion of the Productive Simplification Secretariat is not binding. As noted, this process is exclusive for draft regulation of the Ministry of Production and Labour.

The absence of an integrated procedure for the three different types of analyses (legal, technical and cost-benefit analysis) limits the potential of a policy that seeks to issue regulations of high quality which provide net-benefits to the society. See Box 3 for an example of the RIA system in the United States.

Box 3. The US RIA model

The main reasons that led to the introduction of RIA in the United States were: i) the need to ensure that federal agencies would justify the need for regulatory intervention before regulating, and would consider light-touch means of intervention before engaging into heavy-handed regulation; ii) the need for the Centre of Government to control the behaviour of agencies, to which regulatory powers have been delegated; and iii) the need to promote the efficiency of regulatory decisions by introducing an obligation to perform cost-benefit analysis within RIA.

Underlying the introduction of RIA was, from a more general viewpoint, the idea that policymakers should be led to make informed decisions, which are based on all available evidence. In the case of the United States, this idea was initially coupled with a clear emphasis on the need to avoid imposing on the business sector unnecessary regulatory burdens, a result that was in principle guaranteed by the introduction of a general obligation to perform cost-benefit analysis of alternative regulatory options and justify the adoption of regulation on clear “net benefits”. Although the US system has remained almost unaltered, the initial approach was partly modified: the emphasis was shifted from cost-reduction to achieving a better balance between regulatory costs and benefits.

The first steps of RIA were also accompanied by a reform of the governance arrangement adopted by the US administration for the elaboration of regulatory proposals:

RIA was introduced as a mandatory procedural step in an already existing set of administrative rules.

The introduction of RIA required the creation of a central oversight body in charge of scrutinising the quality of RIAs produced, the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA).

A focus on cost-benefit analysis. The US RIA system is clearly and explicitly based on the practice of cost-benefit analysis (CBA).

Source: OECD (2015[7]), “Regulatory Impact Assessment and regulatory policy”, in Regulatory Policy in Perspective: A Reader’s Companion to the OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264241800-5-en.

Argentina has established the legal foundations and tools to promote stakeholder engagement in the preparation of draft regulation. Nevertheless, there is a lack of a predictable process and lack of supervision in their use.

The Argentine government has implemented various actions to promote citizen participation in the development of regulation. Since 2003, Decree 1.172/2003 established several bylaws which provide the legal basis for stakeholder engagement in the process of rulemaking. It included the following:

Bylaw for the Participative Drafting of Standards.

Bylaw for Open Meeting of the Regulators of Public Services.

Bylaw of Access to Public Information for the Executive Power.

On November 2017, Decree 891/17 for Good Practices in Simplification was issued, which provides in Article 6 the obligation for government agencies to increase citizen participation mechanisms in the rulemaking process.

Most of the evidence collected suggests that the most common way to perform public consultation is through ad hoc meetings and public audiences. On other cases, more sophisticated examples of public consultation have been carried out whenever the subject matter of the regulation is anticipated to be controversial.

This approach can be a source of regulatory capture if documents are made freely available without any conscientious effort to reach out to a broad range of target groups. As a minimum, there should be some kind of communication that a consultation has been made public.

Additionally, there are no institutional mechanisms in place to establish a standardised procedure and supervise the effective employment of these tools. Regarding the comments that are provided by stakeholders, there is no obligation for government agencies to consider them in the normative proposal, and to provide responses to stakeholders.

In May 2016, the website https://consultapublica.argentina.gob.ar/ was implemented with the aim of strengthening the efforts on open government policy. The platform can be used to undertake public consultation in the development of new regulation, but it has not been used for this purpose yet.6

The benefits of consulting stakeholder in the rulemaking process to collect evidence on the fitness of proposed rules are limited due to their lack of integration into a single ex ante assessment process and lack of oversight. The most effective comment processes provide meaningful opportunities (including on line) for the public to contribute to the process of preparing draft regulatory proposals and to the quality of the supporting analysis, including allowing for comments on the draft text of a rule and the supporting regulatory impact assessment. See Box 4 for an example of consultation guidelines from the United Kingdom.

Box 4. Consultation guidelines: The case of the United Kingdom

Increasing the level of transparency and increasing engagement with interest parties improves the quality of policymaking by bringing to bear expertise and alternative perspectives and identifying unintended effects and practical problems.

Prior to replacing it with the much shorter Consultation Principles in 2012 (updated in 2016), the United Kingdom had a detailed Code of Practice on Consultation (published in 2008), which aimed to “help improve the transparency, responsiveness and accessibility of consultations, and help in reducing the burden of engaging in government policy and development”.

Although not legally binding and only applying to formal, written consultations, the Code of Practice constitutes a good example of how a government can provide its civil servants with a powerful tool to improve the consultation process. The 2016 Consultation Principles highlight the need to pay specific attention to proportionality (adjusting the type and scale of consultation to the potential impacts of the proposal or decision being taken), consider the increasing use of digital methods in the consultation process and reduce the risk of “consultation fatigue”.

The 16-page Code of Practice was divided into 7 criteria, which were to be reproduced as shown below in every consultation:

Criterion 1: When to consult. Formal consultations should take place at a stage when there is scope to influence the policy outcomes.

Criterion 2: Duration of consultation exercises. Consultation should normally last for at least 12 weeks with consideration given to longer timescales where feasible and sensible.

Criterion 3: Clarity of scope and impact. Consultation documents should be clear about the consultation process, what is being proposed, the scope to influence and the expected costs of the proposals.

Criterion 4: Accessibility and consultation exercises. Consultation exercises should be designed to be accessible to, and clearly targeted at, those people the exercise is intended to reach.

Criterion 5: The burden of consultation. Keeping the burden of consultation to a minimum is essential if consultations are to be effective and if consultees’ buy-in to the process is to be obtained.

Criterion 6: Responsiveness of consultation exercises. Consultation responses should be analysed carefully and clear feedback should be provided to participants following the consultation.

Criterion 7: Capacity to consult. Officials running consultations should seek guidance on how to run an effective consultation exercise and share what they have learned from the experience.

An example of a UK government response to the consultation can be found at https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/tackling-intimidation-of-non-striking-workers.

Source: UK Department for Business, Enterprise and Skills (2008[8]), Code of Practice on Consultation, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/100807/file47158.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2019; UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (2016[9]), Consultation Principles 2016, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/492132/20160111_Consultation_principles_final.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2019).

There are examples of a higher degree of adoption of practices of ex ante assessment of draft regulation within the Argentinian government. These experiences could be leveraged to promote the use of this tool across the federal government.

The evidence collected seems to suggest that there are examples of more intensive use of practices on ex ante evaluation of draft regulations and public consultation. The National Securities Commission, the National Gas Regulator (ENERGAS) and the National Electricity Regulator (ENRE) regularly carry out a more sophisticated technical analysis as part of the process of developing new regulations, and it sometimes includes a cost‑benefit analysis. The Ministry of Production and Labour also reports to carry out on occasion cost-benefit analysis for draft regulations to assess potential impacts on productive activities.

In the case of the National Communications Agency (ENACOM), it recently signed a Memorandum of Understanding between the Federal Institute of Telecommunications of Mexico, which includes as one of the areas of co‑operation the exchange of good practices based on the use of regulatory impact assessment.

These valuable experiences could be documented and promoted across government agencies to show examples of good practice through capacity building exercises and other support mechanisms. Learning from peers can be an effective way to encourage the adoption of regulatory quality tools.

Recommendations

Argentina should strive for the establishment of a full-fledged system of ex ante evaluation of draft regulation through the application of the regulatory impact assessment (RIA). The main goal of the RIA System will be to create a culture within the Argentinian government whereby evidence informs policy decisions. See Table 2 for examples of RIA systems in selected OECD countries.

Table 2. Application of RIA, responsible body and guidelines

|

Country or region |

Application of RIA |

RIA’s responsible body |

|---|---|---|

|

Australia |

RIA is mandatory for all regulation sent to the Cabinet, even if there are no evident regulatory impacts. |

The Office of Best Practice Regulation (OBPR) reviews the quality of all RIAs and provides advice and guidance during their development, and its final assessment of RIAs is made public on a central register. The OBPR can ask departments to revise RIAs where quality has been deemed inadequate. |

|

Canada |

Departments and agencies must conduct a RIA on all regulatory proposals, to support stakeholder engagement and evidence-based decision making. Departments and agencies have to comply with relevant acts, regulations, and Treasury Board policies, and adhere to guidance, tools and directives, and are to engage with the Regulatory Affairs Sector at the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. |

The Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) oversees subordinate regulations and provides a review and challenge function to ensure quality RIA, consultation, and regulatory co‑operation. The Department of Justice has a statutory obligation to examine all proposed regulations for legality and conformity with drafting standards. The Standing Joint Committee for the Scrutiny of Regulations scrutinises regulations, including legal and drafting issues. For primary laws, the Privy Council Office supports Cabinet in its assessment and approval of legislative proposals destined for parliamentary consideration. |

|

Mexico |

RIA is mandatory all primary laws or subordinate regulations coming from the executive power, exempting the Secretariat of National Defence and Navy. |

The National Agency of Better Regulation (CONAMER) is the body in charge of reviewing all RIAs. If a RIA is unsatisfactory, for example, if it does not provide specific impacts, CONAMER can request the RIA to be modified, corrected or completed with more information. If the amended RIA is still unsatisfactory, CONAMER can ask the lead ministry to hire an independent expert to evaluate the impacts, and the regulator cannot issue the regulation until CONAMER’s final opinion. |

|

European Union |

RIA is mandatory for legislative and non-legislative initiatives with important economic, environmental and social effects. Since 2015, Inception Impact Assessments, including an initial assessment of possible impacts and options to be considered, are prepared and consulted on for four weeks, before a full RIA is conducted. |

The Commission’s Secretariat General (SG) is the Centre of Government body responsible for overseeing Better Regulation. The SG reviews the RIAs, it also serves as the secretariat to the Regulatory Scrutiny Board (RSB), which checks the quality of all impact assessments and major evaluations of EU legislation. Outside the Commission, the European Parliament (EP)’s Directorate for Impact Assessment also reviews RIAs attached to draft legislation submitted by the Commission. |

Source: OECD (2018[1]), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072‑en; Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (2018[10]), Policy on Cost‑Benefit Analysis, https://www.canada.ca/en/treasury-board-secretariat/services/federal-regulatory-management/guidelines-tools/policy-cost-benefit-analysis.html (accessed on 9 February 2019).

The RIA system should bring together under an articulated process the existing elements of ex ante assessment – legal scrutiny and technical analysis – and should add the additional element of a cost-benefit analysis.

The cost-benefit analysis should include the expected effect on economic activity under the responsibility of the Ministry of Production and Labour, as well as the impact on consumers, small businesses, amongst others. See Box 5 for examples of assessment of benefits and costs in selected OECD countries.

Box 5. Ensuring correct assessment of cost and benefits: Some country examples

In Australia, a preliminary assessment determines whether a proposal requires a RIA and helps to identify best practice for the policy process. A RIA is required for all Cabinet submissions. There are three types of RIAs: Long Form, Standard Form and Short Form. Short Form assessments are only available for Cabinet Submissions. Both the Long Form and Standard Form must include, amongst other requirements, a commensurate level of analysis. The Long Form assessment must also include a formal cost-benefit analysis.

In Canada for the case of subordinate regulations, when determining whether and how to regulate, departments and agencies are responsible for assessing the benefits and costs of regulatory and non-regulatory measures, including government inaction. This analysis should include quantitative measures and, if it is not possible to quantify benefits and costs, qualitative measures. When assessing options to maximise net benefits, departments are to: identify and assess the potential positive and negative economic, environmental, and social impacts on Canadians, business (including small business), and government of the proposed regulation and its feasible alternatives; and identify how the positive and negative impacts may be distributed across various affected parties, sectors of the economy, and regions of Canada. Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat provides guidance and a challenge function throughout this process.

In the United States, for the case of subordinate regulation, agency compliance with cost-benefit analysis is ensured through review of the draft RIA and draft regulation by the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs under Executive Order 12866.

Source: OECD (2015[4]) Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264238770-en.

Provision should be taken to establish a proportionality criterion in the preparation and assessment of the cost-benefit analysis, whereby a monetised quantification of the expected benefits and costs is compulsory only for high-impact regulation; and other techniques are used for the rest, including qualitative approaches. See Box 6 for some country examples of threshold tests to apply RIA.

Box 6. Threshold tests to apply RIA: Some country examples

Belgium applies a hybrid system. For example, of the 21 topics that are covered in the RIA, 17 consist of a quick qualitative test (positive/negative impact or no impact) based on indicators. The other four topics (gender, small and medium-sized enterprises [SMEs], administrative burdens, and policy coherence for development) consists of a more thorough and quantitative approach, including the nature and extent of positive and negative impacts.

Canada applies RIA to all subordinate regulations but employs a Triage System to decide the extent of the analysis. The Triage System underscores the Cabinet Directive on Regulatory Management’s principle of proportionally, in order to focus the analysis where it is most needed. The development of a Triage Statement early in the development of the regulatory proposal determines whether the proposal will require a full or expedited RIA, based on costs and other factors:

Low impact: Costs less than CAD 10 million present value over a 10-year period or less than CAD 1 million annually.

Medium impact: Costs CAD 10 million to CAD 100 million present value or CAD 1 million to CAD 10 million annually.

High impact: Costs greater than CAD 100 million present value or greater than CAD 10 million annually.

Also, when there is an immediate and serious risk to the health and safety of Canadians, their security, the environment, or the economy, the Triage Statement may be omitted and an expedited RIA process may be allowed.

Mexico operates a quantitative test to decide whether to require a RIA for draft primary and subordinate regulation. Regulators and line ministries must demonstrate zero compliance costs in order to be exempt from RIA. Otherwise, a RIA must be carried out. For ordinary RIAs comes a second test – qualitative and quantitative – what Mexico calls a “calculator for impact differentiation”, whereas a result of a ten questions checklist, the regulation can be subject to a High Impact RIA or a Moderate Impact RIA, where the latter contains fewer details in the analysis.

New Zealand employs a qualitative test to decide whether to apply RIA to all types of regulation. Whenever draft regulation falls into both of the following categories, then RIA is required: i) the policy initiative is expected to lead to a Cabinet paper; and ii) the policy initiative considers options that involve creating, amending or repealing legislation (either primary legislation or disallowable instruments for the purposes of the Legislation Act 2012).

The United States operates a quantitative test to decide to apply RIA for subordinate regulation. Executive Order 12866 requires a full RIA for economically significant regulations. The threshold for “economically significant” regulations (which are a subset of all “significant” regulations) is set out in Section 3(f)(1) of Executive Order 12866: “Have an annual effect on the economy of USD 100 million or more or adversely affect in a material way the economy, a sector of the economy, productivity, competition, jobs, the environment, public health or safety, or State, local, or tribal governments or communities”.

In the European Commission, a qualitative test is employed to decide whether to apply RIA for all types of regulation. Impact assessments are prepared for commission initiatives expected to have significant economic, social or environmental impacts. The Commission Secretariat General decides whether or not this threshold is met on the basis of a reasoned proposal made by the lead service. Results are published in a roadmap.

Source: OECD (2015[4]) Regulatory Policy Outlook 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264238770-en.

The RIA process should include provision for the consultation of draft regulation with stakeholders in a systematic manner.

As part of the consultation tasks, regulators and agencies should have the obligation to inform stakeholders which comments will be used to amend the draft regulation, and which ones will be discarded, and the reasons why.

The regulatory policy group should allocate clear responsibilities across their members for the oversight of the RIA system, including the consultation stage.

Argentina should consider granting the regulatory policy group the capacity to return RIAs and delay the publication of regulation should the analysis, explanations and justifications of the RIA are deemed inappropriate, or if the consultation process was not undertaken properly.

Argentina should consider the application of a staged approach to the introduction of the RIA system. As part of a pilot programme, the most developed practices on ex ante assessment of draft regulation within the Argentinian government could be leveraged to promote the adoption of the RIA in a defined group of agencies. The experience acquired and the lessons learned in the pilot phase could then be exploited to roll out a wider RIA programme across the Argentinian government.

For the purpose of embarking on a pilot programme on RIA, Argentina should invest in generating capacities in government officials on topics of regulatory policy in general and on methodologies of impact assessment.

Administrative simplification and management of the stock of regulation

Administrative simplification is a tool used to review and simplify the stock of regulations. Reducing the administrative burdens of government regulations on citizens, businesses and the public sector through administrative simplification should be a part of the government’s strategy to improve economic performance and productivity. Additionally, the evaluation of existing regulations through ex post impact assessment is necessary to ensure that regulations that are in place are effective and efficient. In this section, recent and current initiatives and practices implemented by the Government of Argentina on administrative simplification and ex post assessment of regulation are assessed.

Assessment

Argentina pursues an active policy on the extensive use of ICT with the aim of establishing a digital and paperless government. In order to boost the benefits of these initiatives in the context of regulatory policy, it will be essential to continue making a clear distinction between procedures inside government offices and agencies (internal processes, communications, interactions) and formalities which citizens and business are obliged to submit (request of permits or licenses).

Argentina is currently engaged in an ambitious project to make all government processes electronic and paperless. The efforts are led by the Administrative Modernisation Secretariat. Several decrees have been issued to provide the legal basis and framework for these efforts, amongst them, Decree 434/2016, Decree 561/2016 and Decree 733/2018.

The modernisation process follows a cross-layer strategy. The starting point and main driver of such modernisation is the establishment of all internal processes and communication within and between public entities through an electronic platform, which is already operational. This strategy took its inspiration and is equivalent to the one implemented in the city of Buenos Aires a few years ago. The aim is to have a “paperless government”.

At the outset of the preparation of this report, the electronic strategy had not yet reached for the most part the formalities which citizens and business are obliged to submit to the government to start an economic activity or request a service, such as submission for approval of permits and licenses, with few exemptions. At the time of finishing this report, the Administrative Modernisation Secretariat has implemented an extensive programme to make electronically available a large number of formalities for citizens and businesses on line, through the programme of “distance formalities”.

One of the apparent reasons of the slow pace in progress in electronic formalities for businesses and citizens was in part due to the fact that both the internal procedures of the government (internal processes, communications, interactions within and between officials and agencies) and the citizen and business formalities (request of permits and licences) are referred to as trámites. Even though the two concepts are related, because in the end the citizen and business formalities will necessarily require the use internal government processes, it is necessary to continue having a clear distinction between them to have an effective regulatory policy.

In order to devise and implement an effective administrative simplification strategy which reduces burdens in the economy, the citizen and business formalities have to be clearly identified and defined as a separate set from the internal government procedures. See Box 7 for an example of a programme on administrative simplification from the United Kingdom directed to formalities for citizens and businesses.

Box 7. Red tape challenge in the United Kingdom

Between 2011 and 2014, the Cabinet Office of the United Kingdom carried out the Red Tape Challenge. This initiative aimed at reviewing rules and regulations of six general topics (equalities, health and safety, environment, employment-related law, company and commercial law and pensions) and those of specific sectors or industries.

The assessment of the regulations was based on the following procedure:

1. Every few weeks, specific topics were open to comments from citizens, businesses and society organisations.

2. Comments were posted on line and sector champions and departmental leaders were in charge of providing feedback and answers.

3. Contributions were analysed and used as input in the development of proposals for regulatory reform.

4. The Ministerial “Star Chamber” reviewed the proposals and made recommendations. Departments had to scrap burdensome regulations unless they could justify them to the “Star Chamber”.

5. Departments responded to the recommendations of the “Star Chamber” and prepared proposals for the Reducing Regulation Committee.

6. Policies were implemented.

The challenge accounted for over GBP 10 billion in savings for businesses and 3 095 regulations scrapped or improved.

Source: UK Cabinet Office (2015[11]), The Red Tape Challenge Reports on Progress, https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20150423095857/http://www.redtapechallenge.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/home/index/ (accessed on 9 February 2019).

Argentina provides free-access to current regulation and the judiciary information stock through digital databases which goes towards OECD standards. At the start of the preparation of this report, Argentina did not have a complete inventory of citizen and business formalities, which is one of the primary blocks for regulatory transparency and administrative simplification. Significant progress has been made since then, but challenges remain.

Argentina has invested in free-access digital databases with legislative (www.infoleg.gob.ar) and judicial (www.saij.gob.ar) information. Both web portals are an important source of legal information at federal, provincial and city level (City of Buenos Aires). These web portals, along with the Official Gazette (www.boletinoficial.gov.ar), are practices in line with OECD standards, as they provide and spread information about current regulation.

Citizen and business formalities comprise the requirements that citizen and business must submit to the government to undertake certain economic or social activities. The website www.argentina.gob.ar is a government platform which brings together information on citizen and business formalities, and provides a single entry point for users to access government information, formalities and services. The legal foundation of the site is Decree 87/2017. The site provides information on and access to formalities; and at the onset of the preparation of this report, it was possible for only some of them to submit information online. The site also shows elements consistent with an organisation of information according to life events: citizens and business formalities clustered by topics such as work and labour, education or opening a business. At the finalisation of this report, the website was linked to the sister website tramitesadistancia.gob.ar, which now allows citizens and business to submit and receive information on line for a large number of formalities.7

Despite this progress, the evidence collected is that most of the line ministries do not have a list which identifies the complete stock of citizen and business formalities under their jurisdictions. Therefore, it is not possible to determine whether the websites www.argentina.gob.arg and tramitesadistancia.gob.ar hold the complete inventory of formalities for business and citizens at the federal level in Argentina. This situation imposes large challenges for a programme on administrative burden reduction for citizens and business, as the first building block is to have an inventory of information obligations clearly defined. See Box 8 for examples on inventories of formalities on selected OECD countries.

Box 8. Examples of inventories of formalities in selected OECD countries

With the increased use of ICT, governments have the opportunity to reduce the administrative burdens that citizens and businesses face due to government formalities. Users of public services do not necessarily know the name or sequence of formalities that they need to follow, which is why it is important to organise information based on life cycle events and clear and simple topics. Finally, allowing for interoperability to the public administrations’ websites reduces the time devoted to gathering information and allows for a simplification in the number of information requirements.

In Australia, all the information regarding the central and local governments is located on the website www.australia.gov.au. The portal is based on life cycle events and services offered by the government. For each topic, it includes relevant subtopics, direct links to specific government agencies, provides guidance on particular issues and, in some cases, supply the forms or formats required. Also, this web page interconnects with www.my.gov.au, a site where Australian citizens can register and create a profile. This portal grants access to online services provided by the government such as financial aid, healthcare and housing.

Furthermore, the government’s website includes information on Australian departments and agencies, contact details, links to annual reports and media releases and has a section where users can provide feedback on their experience.

The United Kingdom follows an approach to its government website www.gov.uk that is very similar to that in Australia. The services provided by the government are classified according to life events and clear topics such as environment, immigration, crime, etc. Moreover, the site gathers the web pages of all of the government departments and those of many agencies and public bodies. It holds the announcements, publications, statistics and consultations of 25 ministerial departments and 385 bodies. Finally, the site also includes performance data for government services. Indicators on user satisfaction, cost per transaction, completion rate of government services and digital take-up.

Source: Government of Australia (n.d.[12]), australia.gov.au, https://www.australia.gov.au/ (accessed on 9 February 2019); Government of Australia (n.d.[13]), myGov, https://my.gov.au/LoginServices/main/login?execution=e1s1 (accessed on 9 February 2019); UK Government (n.d.[14]), GOV.UK, https://www.gov.uk/ (accessed on 9 February 2019).

Argentina has achieved significant progress in establishing all government processes electronically. More progress in the reduction of burdens through the simplification of formalities for citizens and businesses can be achieved.

Argentina is engaged in an ambitious programme to switch all government procedures to electronic means, which comprises the digitisation of all internal government processes and citizens and business formalities.

The potential rewards of this policy can be significant. The increasing and intensive use of digital tools and platforms can help to streamline and simplify day-to-day internal government processes and activities. This may ultimately benefit citizens and businesses in their dealings with the bureaucracy, thus streamlining and facilitating government-citizen interaction.

Yet, despite the impressive progress in e-government, and the evolution towards a digital government, scarce evidence of the employment of simplification strategies beyond the use of ICT was found, with some exemptions. For instance, Decree 1.079/2016 is currently under development and citizens can submit information through the website www.argentina.gob.ar. In other cases, there is evidence that official response times for permits and licenses have been reduced. Additionally, the Ministry of Production and Labour has made progress in the reductions of administrative burdens and reported savings of ARS 21 million due to the simplification of 43 formalities.

The pursuit of a strategy to reduce administrative burdens for citizens can bring about large benefits: simpler formalities can boost economic activity as citizens and business reduce the resources allocated to fill formats and visit government offices, which benefit more significantly micro and small firms. Additionally, the perception of citizens and business on government efficiency can be improved.

These potential benefits could be realised by means of a prioritisation strategy on administrative simplification with effective oversight. Argentina has in place the legal framework to embark in the devising and application of such a strategy, although it requires establishing a clear mechanism of supervision. This legal framework includes Decree 891/17 for Good Practices in Simplification, Decree 1063/2016, and Decree 733/2018, amongst others. An example that a prioritising strategy to improve regulation and simplify formalities should lead the strategy of digitalisation of internal government procedures is the issuance of Decree 27/2018 of De-bureaucratisation and Simplification, which later on led to Law 27, which included the issuance of three laws, including Law 27.444 of Simplification and De-bureaucratization for the Productive Development of the Nation.

Box 9. Administrative burdens reduction in the European Union

In 2007, the European Union introduced an initiative aimed at eliminating 25% of the administrative burdens faced by businesses. The Programme for Reducing Administrative Burdens in the European Union identified 13 priority areas, which accounted for EUR 123.8 billion in burdens. Based on the idea that information obligations should be identified, measured and reduced, the European Commission proposed a methodology that was an adaptation of the Standard Cost Model (SCM). It is worth mentioning that the programme did not intend to change the original objectives of the regulations, and it proposed a streamlining and optimisation in the way regulations are implemented.

The initial document drew on the experiences of member states who already had carried out a burden reduction exercise and identified the following good practices for the simplification of the administrative costs that businesses face:

1. Reduce the frequency of reporting.

2. Eliminate duplicities or overlaps in information requirements.

3. Promote the use of electronic channels and reduce paper-based formalities.

4. Introduce thresholds to limit the number of information requirements.

5. Use a risk-based approach to the request of information.

6. Review the relevance or validity of the information requirements.

7. Provide clarification and guidance on regulations and compliance.

The target proposed was achieved, reducing administrative burdens by 25%. Future gains due to the streamlining of procedures and elimination of obsolete requirements could boost the EU’s gross domestic product (GDP) by 1.4%.

Source: Commission of the European Communities (2007[15]), Action Programme for Reducing Administrative Burdens in the European Union, https://eur‑lex.europa.eu/legal‑content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52007DC0023&from=EN (accessed on 16 January 2019); European Commission (2012[16]), Action Programme for Reducing Administrative Burdens in the EU Final Report, https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/action-programme-for-reducing-administrative-burdens-in-the-eu-final‑report_dec2012_en.pdf (accessed on 18 January 2019).

Moreover, a whole-of-government regulatory policy, in which administrative simplification strategies is one its elements, should be the one leading to technology decisions, and not the other way around, while stressing the mutually reinforcing benefits of both regulatory and digital policies. The policy should establish the goals on burden reduction and simplification; and based on them, the internal government processes and the formalities for business and citizens should be re-designed, streamlined and transformed leveraging the benefits of digital and other means, in which the oversight body supervises the implementation of the tasks. See Box 9 above for an example of a programme of burden reduction from the European Commission.

There are initial efforts on ex post evaluation of regulation in Argentina but a clear systematic policy on this regard has not been developed.

Decree 891/17 for Good Practices in Simplification establishes the obligation for line ministries and government agencies to use tools on ex post evaluation of regulation. They comprise the assessment of regulation in force and the evaluation of regulatory burdens to simplify existing rules. As with other regulatory quality tools, institutional mechanisms to promote and supervise their implementation have not been established yet.

A noteworthy early effort on ex post evaluation of regulation is the recent issuance of Decree 27/2018 of De-bureaucratisation and Simplification. Consultations were made inside the government with line ministries and agencies to identify legal provisions liable to be eliminated or reformed, with the aim of reducing red tape and improving the legal framework. It includes 197 measures of reform and simplification.

Decree 27/2018 of De-bureaucratisation and Simplification was replaced by Law 27.444. Law 27.445 and Law 27.446, all called Law of Simplification and De-bureaucratization for the Productive Development of the Nation in order to make the legal changes permanent.

The evidence collected seems to indicate that many of the rules eliminated or changed were outdated provisions which were already in disuse, the so-called “deadwood”. OECD country experiences show this kind of exercise to be a good starting point, from which more sophisticated undertakings can be built. Additionally, eliminating “deadwood” also serves a genuinely useful purpose, as it enables businesses and third parties to accurately navigate laws and regulations. If this kind of exercise is not undertaken, the stock of regulation can become clogged with obsolete and overlapping rules.

Beyond this exercise, no systematic efforts to evaluate current regulation were identified. See Box 10 for an example of systematic practices of ex post evaluation from Australia.

Box 10. Ex post reviews of regulation in Australia

Australia performs highly on practices of ex post evaluation of regulations among OECD member countries according to the 2018 OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook (OECD, 2018[1]). The Australian Office of Best Practice Regulation and the Productivity Commission are the bodies in charge of the promotion and revision of the evaluation of regulations once they have been implemented. The country uses three broad approaches to ex post reviews, based on the legal requirements and policy objectives of the regulation.

One of the reasons for evaluating existing regulations is to manage the regulatory stock. Regulations can become obsolete or require information no longer relevant for the authorities, creating additional administrative burdens for citizens and businesses. The three methodologies used for controlling the inventory of regulations include:

1. Regulator-based strategy: It assumes that the regulator can administer and improve the policies under its management.

2. Stock-flow linkage: It limits the number of regulations that can be introduced; examples include the one-in, x-out rule.

3. Red tape reduction targets: It reduces the administrative burdens generated by regulations.

Programmed reviews are mandatory evaluations of the regulation. They are established in legal instruments and define a period within which the regulation should be reviewed. The Australian government uses three approaches as part of the programmed reviews.

1. Sunset clauses: Define the lifespan of the regulation. After this period the regulation will lose its validity.

2. Post-implementation reviews: It evaluates the impact of the regulation once it has been implemented.

3. Ex post reviews required in new legislation: Clauses that define the circumstances under which the regulation can be evaluated.

Finally, some reviews take place as a need arises. These ad hoc or special reviews tend to have a broader scope, involve more stakeholders or focus on a specific sector.

1. Stocktakes of burdens on business: These reviews take into account the comments and feedback provided by businesses

2. Principle-based reviews: Use a screening mechanism, such as restrictions to competition, to assess regulations.

3. Benchmarking: Compares regulations across jurisdictions.

4. In-depth reviews: Analyse the impact of a regulation, or a group of regulations, on a specific sector or industry.

Source: OECD (2018[1]), Review of International Regulatory Co-operation of Mexico, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264305748-en; Office of Best Practice Regulation (2016[17]), Sunsetting Legislative Instruments, https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/obpr-gn-16-sunsetting.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2019); Office of Best Practice Regulation (2017[18]), Best Practice Regulation Report 2015-16, http://www.pmc.gov.au/office-best-practice-regulation; Office of Best Practice Regulation (2016[19]), Post-implementation Reviews, https://www.pmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/017_Post-implementation_reviews_2.pdf, (accessed on 9 February 2019).

Recommendations

Establish in a policy document the definition of a formality for citizens and businesses.

Ensure that the websites www.argentina.gob.arg and tramitesadistancia.gob.ar have consistent information, have all the information of formalities for citizens and businesses of the central government of Argentina, and for transparency, openness and informational purposes, they are the single source of information of formalities.

Keep the registry of formalities updated by requiring ministries and agencies to inform the registry whenever new formalities are “born” or are eliminated, or when the data requirements in a formality change.

Define and implement a comprehensive strategy of administrative simplification for citizens and business formalities, leveraging the experience collected so far as part of e-government and digital government efforts, in the achievements of the programme of “distance formalities” and in the experience of the Ministry of Production and Labour.

The strategy should have targets in the reduction of administrative burdens for citizens and businesses and should establish priority sectors for the reduction, depending on the most complex regulatory areas for citizens and businesses, or the most irritating ones.

The regulatory policy group should oversee the planning, development and implementation of the registry of formalities and of the administrative simplification strategy.

Once a system of RIA is in place, Argentina should consider establishing periodic reviews of the stock of regulation similar to the one carried out with Decree 27/2018 of De-bureaucratisation and Simplification. For this purpose, guidelines and other supporting material should be issued to help government agencies to comply with the obligation of ex post evaluation of regulation. Consider establishing a prioritising strategy to focus the efforts on the most meaningful assessments.

The governance of regulators

Good regulatory outcomes depend on more than well-designed rules and regulations. Regulatory agencies are important actors in regulatory systems that are at the delivery end of the policy cycle. The OECD 2012 Recommendation recognises the role of regulatory agencies in providing greater confidence that regulatory decisions are made on an objective, impartial and consistent basis, without conflict of interest, bias or improper influence. This section addresses the governance arrangements in force in the Government of Argentina for economic regulatory agencies that have a degree of independence from the central government.

Assessment

Role clarity: The National Communications Agency (ENACOM) has a significant opportunity to establish regulatory activities as the priority in the new framework to be developed.

ENACOM is a rather new agency, but without an updated law due to the unification of the communications and broadcasting branches. In this situation, the agency is currently defining the rules while the new law emerges. Thus, it is a priority to issue the new law to define the policy objectives for ENACOM, in which the regulatory activity should be the main priority of the agency, and the avoidance of conflicting or competing objectives should be sought, such as the active promotion of new investments. See Box 11 for an example of objective definitions for the rail regulator from the United Kingdom.

Box 11. Objectives and prioritisation of functions at the Office of Rail and Road in the United Kingdom

The Office of Rail and Road (ORR) in the United Kingdom regulates the rail industry's health and safety performance and makes sure that the rail industry is competitive and fair. Besides, they have economic regulatory functions in relation to railways in Northern Ireland and for the northern half of the Channel Tunnel, situated in the United Kingdom. The long-term vision of the ORR is “…a partnership of Network Rail, operators, suppliers and funders working together to deliver a safe, high-performing, efficient and developing railway”.

The enforcement powers of the ORR are established not only in country regulation but also in the European Union framework. The most important laws and rules guiding the activities of the ORR are the following:

Railway Act (1993) for economic enforcement.

Competition Act (1998) for competition enforcement.

2012/34/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 21 November 2012 for Powers and functions under European legislation.

Enterprise Act 2002 for market studies and market investigation references.

Consumer Rights Act 2015 and Part 8 of the Enterprise Act for consumer enforcement.

The ORR prioritises its activities in order to deliver the highest value of intervention. The strategic plan to achieve and prioritise its duties comprise:

Strategic significance: how the intervention delivers outcomes and is aligned with the strategic objectives.

Relevance and need of the ORR’s act: if the ORR is the best institution to intervene in a specific situation.

Impact: the likely impact derived from the ORR intervention is a relevant factor to consider. For instance, the ORR takes into account the actual and potential level of harm and damage, the evidence of systemic or isolated risks, the environment of the situation, the cost and prices of consumers, the deterrent effects or the potential benefits, etc.

Costs: the internal and external costs of the intervention.

Risks: the probability to achieve a successful outcome, the legal risks, the impact of intervention over credibility and reputation of ORR.

Source: Office of Rail and Road (2019[20]), About ORR, http://orr.gov.uk/about-orr (accessed on 9 February 2019).

Preventing undue influence and maintaining trust: regulators in Argentina undertake measures to reduce the risk of undue influence from the public, stakeholders and other public institutions. For instance, regulators rely on specific rules to limit “revolving doors” and they install public audiences to develop new regulations. These practices, however, could be strengthened with supplementary activities to promote and maintain trust, as economic regulators should aspire to have more comprehensive and stronger practices on transparency and accountability than the ones applied by line ministries for instance.

Regulators must work hand in hand with regulated entities, the general public, and need to co‑ordinate with other public institutions to achieve their goals. A relevant challenge for regulators is to prevent undue influence in order to remain impartial and unbiased in their regulatory decisions.

Economic regulators in Argentina have developed fora and rules to communicate and engage with stakeholders on the process of regulatory decision making, which can help narrow the risk of undue influence. Regulators employ public audiences, users’ commissions, consultation processes, and informational meetings with stakeholders, in which other participants can also be present. However, there is heterogeneity in the functioning of these practices, which can undermine the prevention of undue influence.

Also, the publication of regulatory planning agendas in which regulators announce the legal instruments intended to be revised or issued anew can contribute to promote transparency and participation, and limit spaces for regulatory capture.