This chapter contains a description of the structure of the government of Argentina, which comprises the national and subnational levels. It also presents a brief description of the recent and current economic performance of Argentina, in which the inputs come mainly from the latest OECD Multi-dimensional Economic Survey of Argentina.

Regulatory Policy in Argentina

Chapter 1. The context for regulatory policy in Argentina

Abstract

With a mainland area of 2.8 million km², the Argentine Republic (hereafter Argentina) is the 8th largest country in the world and second largest in Latin America. It is also the second largest economy in South America after Brazil and the third largest in Latin America. In recent years, Argentina has undertaken policy reforms with the objective to enhance economic performance and improve the living standards of citizens. In most cases, these reforms imply significant changes in economic management and in the institutional landscape and performance within the public policy making. Notwithstanding, opportunity areas remain to continue building and improving the institutional framework to achieve social and economic objectives and reduce the vulnerabilities and potential risks for the economic performance of Argentina.

Government structure in Argentina

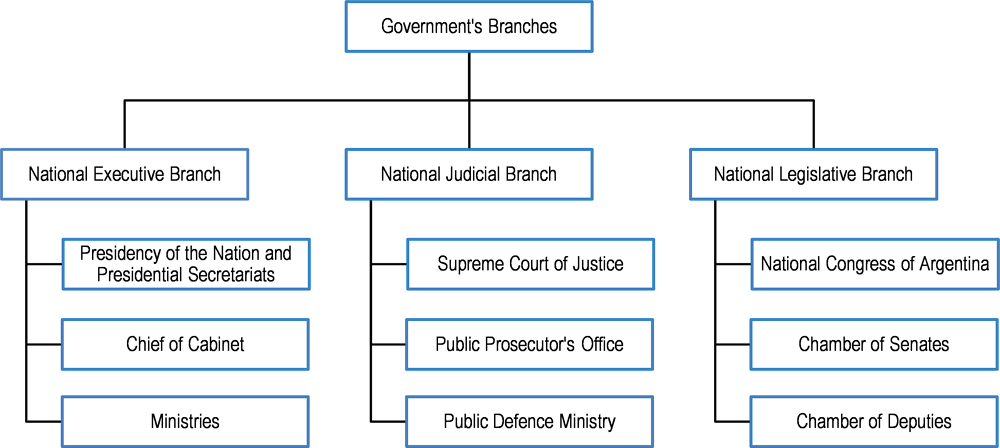

Argentina is a federal state divided into 24 self-governed states – 23 provinces and the Autonomous City of Buenos Aires. At the national level, the powers of the republic are divided into the National Executive Power, the National Judicial Power, and the National Legislative Power (see Figure 1.1). The presidency of the nation, secretariats, chief of cabinet and ministries sit within the National Executive Power. The National Legislative Power holds both the Chambers of Deputies and the Chamber of Senators.

Figure 1.1. Branches of the Argentine Republic

Source: Adapted from Dirección Nacional de Diseño Organizacional (2019[1]), Administración Pública Naiconal, https://mapadelestado.jefatura.gob.ar/organigramas/autoridadesapn.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2019); and Dirección Nacional de Diseño Organizacional (2019[2]), Administración Pública Nacional: Descentralizada y Entes del Sector Público Nacional, https://mapadelestado.jefatura.gob.ar/organigramas/apndescentralizados.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2019).

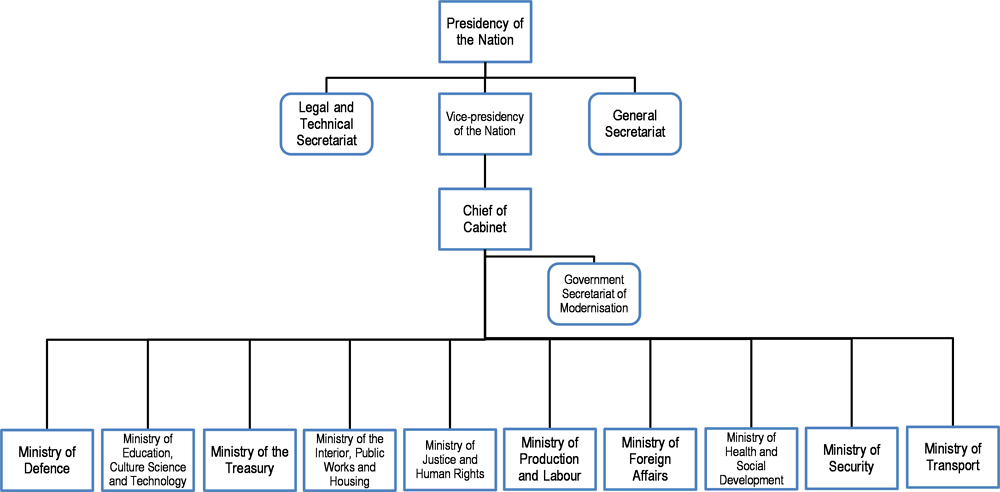

The head of the National Executive Branch is the President of the Nation. In turn, the National Executive Branch is composed of 10 ministries and of 99 secretariats, some belonging to the Presidency of the Nation, the Chief of Cabinet and the rest to the ministries (see Figure 1.2 and Table 1.1.). The structure of the National Executive Branch was reformed in 2018 through Decree 801/2018 and Decree 802/2018. The restructuring responded to the fiscal challenges facing Argentina and with the objective of improving decision making and policy delivery.

Figure 1.2. Structure of the National Executive Branch of Argentina

Source: Adapted from Dirección Nacional de Diseño Organizacional (2019[1]), Administración Pública Naiconal, https://mapadelestado.jefatura.gob.ar/organigramas/autoridadesapn.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2019); and Dirección Nacional de Diseño Organizacional (2019[2]), Administración Pública Nacional: Descentralizada y Entes del Sector Público Nacional, https://mapadelestado.jefatura.gob.ar/organigramas/apndescentralizados.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2019).

Table 1.1. Ministries and secretariats of the National Executive Power in Argentina

|

Ministry |

Main secretariats per ministry |

|---|---|

|

Ministry of Education, Culture, Science and Technology |

- Government Secretariat of Science, Technology and Productive Innovation - Government Secretariat of Culture - University Policies Secretariat - Innovation and Educational Quality Secretariat - Educational Evaluation Secretariat - Educational Management Secretariat - Planning and Policies in Science, Technology and Productive Innovation Secretariat - Scientific and Technological Articulation Secretariat - Culture and Creativity Secretariat - Cultural Management Coordination Secretariat - Cultural Heritage Secretariat |

|

Ministry of Defence |

- Industrial Policy Research and Production for Defence Secretariat - Budgetary Management and Control Secretariat - Research, Industrial Policy and Production for Defence Secretariat - Strategy and Military Affairs Secretariat |

|

Ministry of Energy and Mining |

- Electric Energy Secretariat - Mining Secretariat - Hydrocarbons Resources Secretariat - Strategic Energy Planning Secretariat |

|

Ministry of the Treasury |

- Government Secretariat of Energy - Public Revenue Secretariat - Treasury Secretariat - Finance Secretariat - Economic Policy Secretariat - Legal and Administrative Secretariat - Energy Planning Secretariat - Non-Renewable Resources and Fuel Market Secretariat - Renewable Resources and Electricity Market Secretariat |

|

Ministry of the Interior, Public Works and Housing |

- Infrastructure and Water Policy Secretariat - Interior Secretariat - Territorial Planning and Coordination of Public Works Secretariat - Political and Institutional Affairs Secretariat - Housing Secretariat - Urban Infrastructure Secretariat - Coordination Secretariat - Territorial Planning and Coordination of Public Works Secretariat - Provinces and Municipalities Secretariat |

|

Ministry of Justice and Human Rights |

- Justice Secretariat - Human Rights and Cultural Pluralism Secretariat |

|

Ministry of Production and Labour |

- Government Secretariat of Agribusiness - Government Secretariat of Labour and Employment - Mining Policy Secretariat - Administrative Coordination Secretariat - Productive Integration Secretariat - Entrepreneurs and Small and Medium Enterprises Secretariat - Productive Simplification Secretariat - Industry Secretariat - Productive Transformation Secretariat - Mining Policy Secretariat - Internal Commerce Secretariat - Foreign Trade Secretariat - Food and Bio-economy Secretariat - Family Farming, Coordination and Territorial Development Secretariat - Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries Secretariat - Labour Secretariat - Employment Secretariat - Citizen Services and Federal Services Secretariat - Promotion, Protection and Technological Change Secretariat - Administrative Coordination Secretariat |

|

Ministry of Foreign Affairs |

- Secretariat for Coordination and External Planning Secretariat - Worship Secretariat - International Economic Relations Secretariat - Foreign Affairs Secretariat |

|

Ministry of Health and Social Development |

- Government Secretariat of Health - Coverage and Health Resources Secretariat - Health Promotion, Prevention and Risk Control Secretariat - Secretariat for Health Regulation and Management Secretariat - Accompaniment and Social Protection Secretariat - Social Economy Secretariat - Social Security Secretariat - Socio-Urban integration Secretariat - Articulation of Social Policy Secretariat - Birth of Childhood, Adolescence and Family Secretariat |

|

Ministry of Security |

- Co‑operation with Constitutional Powers Secretariat - Co‑operation with the Judicial Branches, Public and Legislative Ministry Secretariat - Borders Secretariat - Internal Security Secretariat - Security Secretariat - Civil Protection Secretariat - Coordination, Planning and Training Secretariat - Federal Security Management Secretariat - Coordination, Training and Career Secretariat |

|

Ministry of Transport |

- Coordination, Training and Career Secretariat - Transport Works Secretariat - Transportation Planning Secretariat - Transportation Management Secretariat |

Source: Adapted from Dirección Nacional de Diseño Organizacional (2019[1]), Administración Pública Naiconal, https://mapadelestado.jefatura.gob.ar/organigramas/autoridadesapn.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2019); and Dirección Nacional de Diseño Organizacional (2019[2]), Administración Pública Nacional: Descentralizada y Entes del Sector Público Nacional, https://mapadelestado.jefatura.gob.ar/organigramas/apndescentralizados.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2019).

At the national level, there are also decentralised regulatory agencies. Their competencies concentrate mainly in areas of sectoral and technical regulation and focus on regulating network industries and infrastructure, or regulating financial or human risks, amongst others. See Table 1.2 for a description of some of these agencies.

Table 1.2. Decentralised regulatory agencies of Argentina

Selected agencies

|

Agency |

Role |

|---|---|

|

National Communications Agency (ENACOM) |

Its objective is to create stable market conditions to guarantee citizens' access to Internet, fixed and mobile telephone service, radio, postal and television services. |

|

National Electricity Regulator (ENRE) |

In charge of regulating the electrical activity and controlling that the companies of the sector (generators, transporters and distributors Edenor and Edesur) comply with the obligations established in the regulatory framework and in the concession contracts. |

|

National Gas Regulator (ENARGAS) |

It fulfils the functions of regulation, control, inspection and resolution of disputes related to the public transport and gas distribution service. |

|

National Securities Commission (CNV) |

The National Commission of Capital Markets is in charge of the promotion, supervision and control of capital markets. It is an autocratic entity assigned to the Ministry of Public Finance of Argentina. |

At subnational level, in Argentina, in contrast to other federative countries, each state holds the powers that were not delegated to the federal government, as provinces are prior to the national state. Besides, the states are divided into administrative units which in the case of the City of Buenos Aires these are named communities; in the provinces, these are the departments and the municipalities. All these government levels produce regulation according to their own competencies.

For instance, the municipalities may produce regulation for the use of public areas, the control of public shows, the provision of public services, the promotion of tourism, etc. Chapter 6 contains further discussion of the division of regulatory powers in Argentina.

The provincial government is divided between the executive power (headed by the governor), the local congress and the judiciary authority. As mentioned above, the provincial government holds not delegated powers to the national state; for instance, they have competency in the health and educational systems – in Mexico for example, these are delegated to the federal government. Besides, provinces regulate their municipalities.

A supreme court, the appeal chambers and the inferior courts, composes the judiciary power of provinces. These tribunals have competency in civil, commercial, labour and penal affairs.

Provincial congresses, on the other hand, have competencies in all the subjects not delegated to the national state. These congresses may be unicameral or bicameral, depending on the province.

Recent reforms and current economic performance of Argentina

Argentina is pushing to emerge from a series in economic disturbances and crisis (see Box 1.1). According to OECD (2017[3]), the new government elected in November 2015 inherited an economy at risk of suffering another severe crisis but set out to correct the various imbalances. These reforms helped stabilise the economy in the short term and rekindle inclusive growth. The main structural reforms undertaken include:

Currency controls were abolished.

Export taxes were eliminated except for soybeans, for which they are being phased out.

The scope of application of the cumbersome system of import licensing was significantly reduced.

An agreement with holdout creditors from the 2001 debt default restored access to international capital markets in 2016.

National statistics were completely overhauled.

Multi-year fiscal targets were announced.

Large and untargeted subsidies have been curtailed substantially and are being phased out.

Social benefits, including child benefits, unemployment benefits and pensions, were expanded.

A new capital markets law to develop financial markets and improve corporate governance was submitted to congress.

A large infrastructure investment plan with a focus on the northern provinces was put in place.

A tax amnesty programme led to the declaration of almost 20% of gross domestic product (GDP) in previously undeclared assets held by residents and raised extraordinary tax revenues of 1.6% of GDP.

The Multi-dimensional Economic Survey of Argentina (OECD, 2017[3]) reported that in 2016, the country experienced a 5-year real growth of -0.2% on average. Furthermore, the World Bank reported that in 2017, the country experienced a growth pace of 2.9%, but at the beginning of 2018, Argentina faced new financial turbulences such that in the second quarterly, the economy started to slow down (World Bank, 2018[4]).

The Multi-dimensional Economic Survey of Argentina (OECD, 2017[3]) also reported that the exchange rate was ARS/USD 14.751 in 2016. By the end of 2018 however, the US dollar doubled the value of the Argentinian peso, reflecting the external pressures over the economy (OECD, 2018[5]). Notwithstanding the effects over the Argentinian peso, the abolishment of the exchange rate policy controls during 2015 meant a step in the right direction.

Box 1.1. A glance at Argentina’s economic history

Argentina’s per capita incomes were among the top ten in the world a century ago, when they were 92% of the average of the 16 richest economies (Bolt and van Zanden, 2014[6]). Today, per capita incomes are 43% of those same 16 rich economies. Food exports were initially the basis for Argentina’s high incomes, but foreign demand plummeted during the Great Depression and the associated fall in customs revenues was at the root of the first in a long row of fiscal crises. The economy became more inward-focused as of 1930 when the country suffered the first of 6 military coups during the 20th century.

This inward focus continued after World War II, as policies featured import substitution to develop industry at the expense of agriculture, nationalisations and large state enterprises, the rising power of unions and tight regulation of the economy. The combination of trade protection and a significant state-owned sector lessened somewhat in the mid-1950s, in a succession of brief military and civilian governments.

However, the weakness of both the external and fiscal balances continued into the 1960s and early 1970s, leading to unstable growth performance and bouts of inflation, including the first hyperinflation in 1975. The military dictatorship of the 1970s and the democratic government of the 1980s continued to struggle with fiscal crises, resulting from spending ambitions exceeding revenues and exacerbated by the Latin American debt crisis starting in 1982, and the lack of a competitive export sector after decades of import-substituting industrialisation. The country fell into fully-fledged hyperinflation in 1989-90. Between 1970 and 1990, real per capita incomes fell by over 20%.

While the economy returned to growth after 1990 in the context of lower import tariffs, foreign investment, a currency pegged to the US dollar and falling inflation, volatility did not recede. Export competitiveness faltered following the Asian crisis and the devaluation of the Brazilian Real and by the late 1990s, the economy was facing a severe recession. Rising fiscal imbalances led to the 2001 debt default and the end of the currency peg. The impoverishing effect of the crisis was exacerbated by the subsequent devaluation which wiped out large amounts of household savings. Despite the recurrent crises, the growth performance of Argentina between 1990 and 2010 allowed it to begin a process of convergence with the developed world.

Source: OECD (2017[3]), OECD Economic Surveys: Argentina 2017: Multi-dimensional Economic Survey, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-arg-2017-en.

Main economic indicators as interest rates, fiscal deficit, unemployment rates, foreign investment, etc. have struggled to reflect better performances in the last years. Each of them is challenged by international pressures and economic performance as a whole. In most of them, however, additional to the international shocks, the quality of internal regulation plays a relevant role in the status quo.

For example, the Multi-dimensional Economic Survey of 2017 (OECD, 2017[3]) pointed out that protecting workers with training and unemployment insurance rather than strict regulations was a more effective labour market policy. Empirical evidence in Argentina suggests that more decentralised bargaining at the firm level would increase productivity by reducing stiffness and being more effective in response to market changes.

On the other hand, tax collection in Argentina still holds a complicated and inefficient system, hampering productivity and incentives for investment. For example, unlike the VAT, the provincial turnover tax, which is levied in all stages of the supply chain, creates distorted incentives to vertical integration (as there is no deduction in the early stages) and build barriers to entry between provinces (as different taxes are applied according to the origin of the goods). The financial transaction tax creates another distortion in the financial system, as it is levied on bank transactions with checks and savings accounts. Thus, it incentivises cash payments and delays financial inclusion (OECD, 2017[3]).

The integration of Argentina in the global economy is still low, as international trade accounted in average less than 30% of the GDP from 2010 to 2016. From the side of the imports, it reduces the competition in the local economy and from the exports; it limits the benefits from market expansion as job creation, foreign currency inflows and local currency strength. In this context, 35% of export taxes were a barrier to trade, increased labour unit costs and creates administrative burdens. Besides, Argentina reported that reducing import tariffs may bring not only a reduction in the administrative burdens but an increase in the exports due to more competitive prices (OECD, 2017[3]).

Trade dynamics can be improved through facilitation measures as they can potentially reduce administrative burdens and eliminates barriers to entry. For instance, simplifications on border controls and customs, harmonisation of single electronic documents and consolidation of information can promote international trade and impact on key indicators as interest rates and foreign exchange levels – the single window for international trade or Ventanilla Única de Comercio Exterior (VUCE) is an example of this strategy.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows as a percentage of the GDP are low in comparison with OECD countries and top Latin American economies as Brazil, Chile and Mexico. Is well documented that FDI can promote productivity through technology transfer, improvement of supply chains or better practices in management. The attraction of FDI however, requires addressing challenges related to infrastructure, human capital development and the reduction in the limits to foreign investments, between other relevant reforms (OECD, 2017[3]).

These are some examples of the challenges that the current economy of Argentina faces which policy reforms can help address. A key factor however to develop policy reforms is to have in place a sound regulatory policy. The policy to ensure quality in the regulatory framework has the potential to issue and enforce rules which meet policy objectives, such as protection of consumers and the environment, boost productivity and promote inclusive growth while avoiding burdensome government processes for citizens and businesses.

References

[6] Bolt, J. and J. van Zanden (2014), “The Maddison Project: Collaborative research on historical national”, The Economic History Review, Vol. 67/3, pp. 627-651.

[1] Dirección Nacional de Diseño Organizacional (2019), Administración Pública Nacional: Administración Central y Organismos Desconcentrados, Autoridades Superiores (National Public Administration: Central Administration and Decentralized Organizations, Higher Authorities), https://mapadelestado.jefatura.gob.ar/organigramas/autoridadesapn.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2019).

[2] Dirección Nacional de Diseño Organizacional (2019), Administración Pública Nacional: Descentralizada y Entes del Sector Público Nacional, Autoridades Superiores (National Public Administration: Decentralized and National Public Sector Entities, Higher Authorities), https://mapadelestado.jefatura.gob.ar/organigramas/apndescentralizados.pdf (accessed on 9 February 2019).

[5] OECD (2018), “Argentina”, in OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2018 Issue1, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_outlook-v2018-1-4-en.

[7] OECD (2018), Review of the Corporate Governance of State-Owned Enterprises: Argentina, OECD, http://www.oecd.org/countries/argentina/oecd-review-corporate-governance-soe-argentina.htm (accessed on 9 February 2019).

[3] OECD (2017), OECD Economic Surveys: Argentina 2017: Multi-dimensional Economic Survey, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-arg-2017-en.

[4] World Bank (2018), The World Bank in Argentina: Overview, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/argentina/overview (accessed on 08 February 2019).