The scale of return migration from OECD countries is significant. Exit rates in destination countries vary considerably and are closely linked to the composition of immigrants in each country. In European OECD countries, retention rates are higher for immigrants from Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), North Africa and the Middle East than for those from North America. Comparing the number of migrants returning to their origin countries with the total number of immigrants in the respective destination countries suggests that return rates in origin countries are generally low. Several indicators suggest that return migrants have a more favourable economic situation than the general population, with higher levels of education and employment rates.

Return, Reintegration and Re-migration

3. Patterns of return migration from OECD countries

Abstract

Key findings

Return migration can be estimated by different methods. The sets of estimates presented in this chapter are based on two: exit rates based on data from destination countries (labour force surveys and specialised surveys), which tend to exclude transient and short-staying migrants, and return rates based on data from origin countries (population censuses and specialised surveys).

In European OECD countries, exit rates within five years of residence vary considerably, with the Netherlands and Germany having the highest average exit rates (75% and 67%) and France having the lowest (26%) over the 2010‑19 period.

Retention rates in European OECD countries vary by region of origin, with immigrants from Latin America and the Caribbean, North Africa, and the Middle East showing higher retention rates, while immigrants from North America have the lowest retention rates.

In the United States, the average exit rate of immigrants within five years is between 12.5% and 16%, depending on the method used. More recent entry cohorts show a higher exit rate than earlier periods. Chinese, Indian and Canadian immigrants are more likely to leave within five years.

In Canada, 21% of migrants who arrived in 2010 left the country within five years. Of the 79% who stayed, 44% became Canadian citizens.

In Latin America, return rates vary by country of origin and destination. Ecuadorians who emigrated to Spain have the highest return rate (32%) in contrast to Mexicans returning from the United States (3%).

In Morocco, the total number of return migrants since 2000 is estimated at 188 000, with an average of 10 000 return migrants per year. In Tunisia, the MED-HIMS survey estimates the number of return migrants at 210 848, 55% of whom have returned between 2000 and 2020.

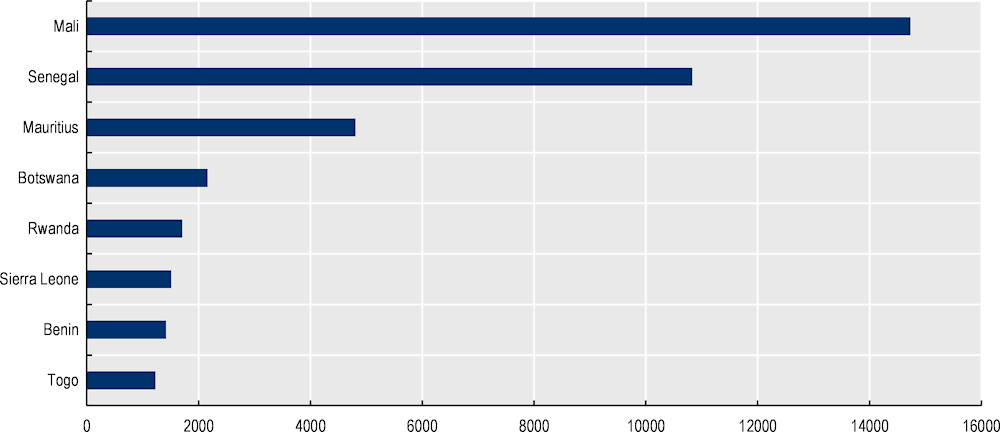

Among the census findings from Sub-Saharan African countries considered for this section, Mali has the highest number of return migrants from OECD countries (14 730) in the five years preceding the last census, followed by Senegal (10 830) and Mauritius (4 810).

Most return migrants in Sub-Saharan Africa return from European countries, particularly France and the United Kingdom. However, these return rates appear relatively low when examined from the destination country perspective: Senegalese and Malian immigrants in France, for example, have a return rate of 4% and 9% respectively after five years of residence.

While return migration is an important component of migratory flows and a key policy concern for OECD countries, knowledge about the extent and nature of return remains limited. Most OECD countries monitor the outflows of migrants through a variety of sources, such as registers for foreigners and administrative data. Yet, there is no comprehensive overview of return patterns, which is a prerequisite for more effective migration policies in both countries of origin and destination.

This section seeks to fill this knowledge gap by conducting a statistical analysis of return patterns. The analysis is similar to that conducted by the OECD in 2008 (OECD, 2008[1]). Return migration is measured by using data that was collected in both destination and origin countries. These measures are based on indirect estimates reflecting changes in migrant population stocks. Returns that are identified from data in destination countries are based on immigrants leaving the territory (exit rates). These exit rates are obtained through Labour Force Surveys (LFS) and specialised surveys, such as the American Community Surveys (ACS). Data that are collected in origin countries, on the other hand, reflect returns identified based on native‑born persons entering the country (return rates). These return rates are obtained from both population censuses which include a question of residence five years prior to census date and representative surveys with information on individuals’ previous place of residence. Despite methodological limitations (Annex A), the indirect estimates draw an indicative portrait of return migrants, including their main socio‑economic characteristics and length of stay.

3.1. Exit and retention rates of migrants in OECD countries

This section examines exit and retention rates from OECD countries with a focus on European countries, the United States and Canada.

3.1.1. European OECD countries

Exit rates for European OECD countries are estimated from the International Migration Database and LFS covering the period 2010 to 2019. As Table 3.1 shows, exit rates after five years of residence vary across EU countries. The Netherlands and Germany have the highest average exit rates, with 75% and 67% of immigrants leaving within five years. In contrast, France has the lowest average exit rate, at 26.5% over the same period. At approximately 31%, exit rates in the United Kingdom and Sweden are also relatively low.

Table 3.1. Estimates of exit rates in selected European OECD countries after five years of residence

|

Country |

Entry period |

Average exit rates after five years (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Netherlands |

2010‑14 |

75.13 |

|

Germany |

2010‑14 |

67.16 |

|

Italy |

2010‑14 |

63.18 |

|

Spain |

2010‑14 |

62.43 |

|

Austria |

2010‑14 |

59.93 |

|

Norway |

2010‑14 |

51.08 |

|

Belgium |

2010‑14 |

48.51 |

|

Finland |

2010‑14 |

48.05 |

|

Switzerland |

2010‑14 |

43.07 |

|

Sweden |

2010‑14 |

31.12 |

|

United Kingdom |

2010‑14 |

30.80 |

|

France |

2010‑14 |

26.53 |

Note: Population aged 15 and over. See Annex A for more information on methodology.

Source: Own calculations based on Labour Force Surveys and OECD International Migration Database.

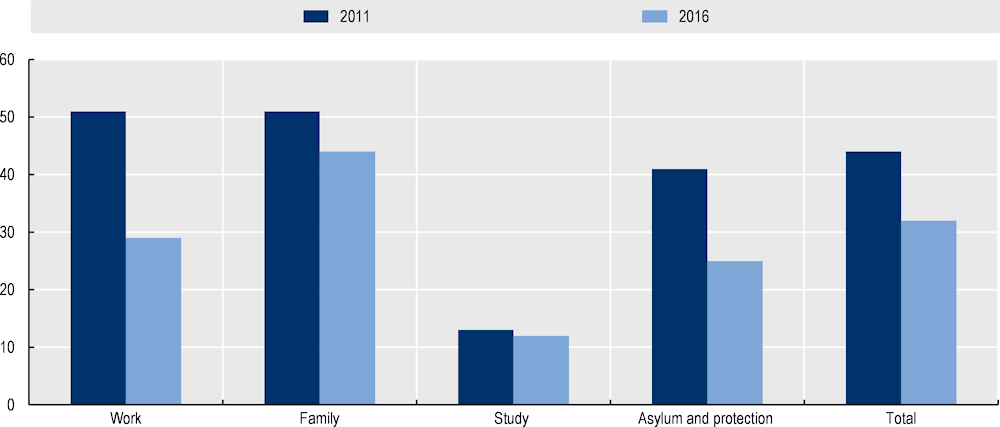

Box 3.1. Variation of retention by category of admission – First residence permits in France

The method presented in Table 3.1 indicates an average exit rate of 27% for France for the 2010‑14 arrivals. These estimates are lower than the exit rates shown by an analysis of first residence permits for the 2008 and 2011 cohorts. The analysis shows significant differences between entry categories. While family migrants have the highest retention rates for both cohorts, highly skilled workers have the lowest retention rates overall. Employees and temporary workers who received their first permit in 2011 are also less likely to remain in the country. This is the case for less than half of them after four years, compared with two‑thirds of the 2008 cohort (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2. Retention rate by type of first residence permit, four and seven years after obtaining first residence permit

|

Type of permit |

2008 cohort |

2011 cohort |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

2012 |

2015 |

2015 |

|

|

Highly qualified (%) |

23 |

10 |

25 |

|

Other work permits (%) |

72 |

66 |

66 |

|

Of which: employees and temporary workers (%) |

63 |

55 |

47 |

|

Family (%) |

89 |

79 |

90 |

|

Study (%) |

42 |

27 |

37 |

|

Other (%) |

73 |

65 |

75 |

|

Total (%) |

71 |

61 |

67 |

Source: AGDREF, Ministry of the Interior

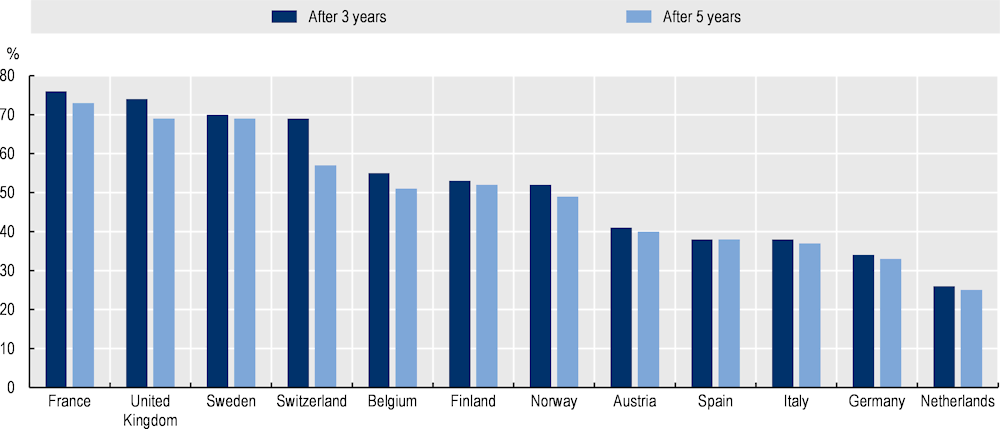

The results further suggest that retention rates of immigrants slightly decrease after five years (Figure 3.1). These findings are consistent with those of (OECD, 2008[1]) and underline that most immigrants who leave their host country do so within a short period of time after arrival.

Figure 3.1. Retention rates after three and five years of residence in selected European countries

Note: Entry period 2010‑14. Population over 15 years.

Source: Own calculations based on Labour Force Surveys and OECD International Migration Database.

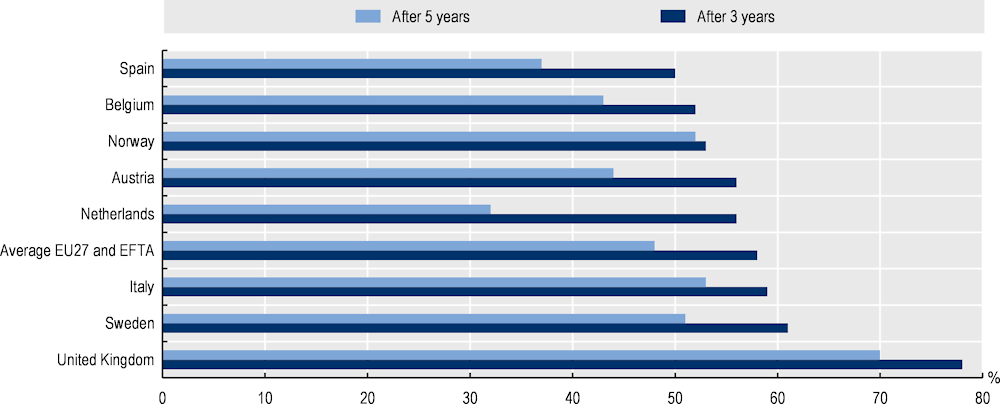

Retention rates also vary by region of origin. In the intra-European context, the results show that, on average, 58% of EU immigrants1 remain after three years and 48% after five years. This gap in retention rates at three and five years is most pronounced in the Netherlands, Spain, and Austria. Whereas the United Kingdom and Sweden tend to retain a high proportion of EU migrants overall, Spain and Belgium have relatively high exit rates (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2. Retention rates for EU‑27 and EFTA immigrants in selected European countries

Note: Entry period 2010‑14. Population aged 15 and over.

Source: Own calculations based on Labour Force Surveys and OECD International Migration Database.

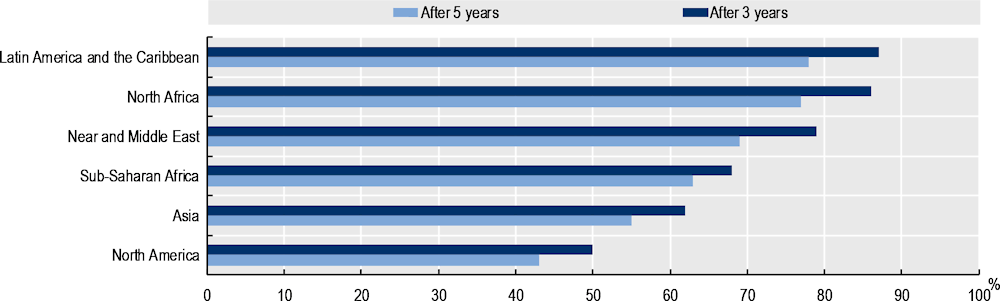

As this report does not focus on patterns of return migration within European countries, it is important to examine the retention rates of immigrants originating from other regions. Figure 3.3 shows that the highest retention rates after three and five years are recorded for migrants from Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), at 87% and 78% respectively. This is closely followed by migrants from North Africa with rates of 86% at three years and 77% at five years. The lowest retention rates are found among North American immigrants, with only 43% still in the destination country after five years.

Figure 3.3. Retention rates in selected European countries by region of origin

Note: Entry period 2010‑14. Population over 15 years. EU countries include Austria, Belgium, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Norway, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

Source: Own calculations based on Labour Force Surveys and OECD International Migration Database.

The retention rates of immigrants from different regions are likely to vary according to the destination country. In France, retention rates after five years are consistently high from any region, exceeding 70% for immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and North Africa. Italy, on the other hand, has lower retention rates than other selected European OECD countries. Retention rates vary by category of admission, and Italy provides an example of this (Box 3.2).

The scale of exits from European countries covered in this analysis are substantial. On average, of the migrants captured using this survey method, about 300 000 migrants exit annually during the first five years. While some may move to a third country, this figure gives an idea of the magnitude of exits of migrants who have spent enough time in the destination country to appear in the survey population.

Box 3.2. Variation in retention by category of admission – Italian residence permits

The method shown above (Figure 3.1) provides an average exit rate of 63% for Italy for the 2010‑14 arrivals. This is slightly higher than the actual exit rate shown by an analysis of residence permits for the 2011 cohort (56%), but close to the 65% rate shown for the 2016 cohort (Figure 3.4). The analysis of residence permits also shows the difference between category of entry. Family migrants had close to 50% retention, while labour migrants had retention rates of about 51% for the 2011 cohort and 29% for the 2016 cohort. Those who entered as students also had a high exit rate – of almost 85% for both cohorts. The differences reflect not just the composition of migrants but also the shifting economic circumstances in Italy and the effect of the COVID‑19 pandemic contributing to higher five‑year exit rates for the 2016 entry cohort.

Figure 3.4. Retention rates vary by purpose of arrival and cohort

Share of immigrants still present in Italy 5 years after arrival, by cohort (2011 and 2016) and initial purpose of stay

Source: Istituto Nazionale di Statistica, Statistiche Report Cittadini non comunitari in Italia, Anni 2022‑23

3.1.2. United States

The United States does not track or report retention of migrant populations, and longitudinal surveys have focused only on specific groups of migrants. There are no administrative datasets indicating how many migrants remain in the United States. To estimate immigrant exits, data from the ACS used covering the period 2010 to 2019. The retention rate is obtained by comparing the size of the immigrant population at entry in a given year with the size of the immigrant population five years later with five years of residence. Entry cohorts were in the range of about 1 million annually. The ACS captures resident immigrants regardless of status, although the sampling method has poor coverage of transients and others in non-typical dwellings. In terms of scale, the method yields numbers close to the scale of permanent migration, but less than the temporary and irregular inflows to the United States, so should be taken as a minimum and reflect those whose stay is at least one year. The results presented in Table 3.3 show that the average exit rate over the period is close to 13%. Exit rates are higher for more recent periods. The scale of outflows from the United States based on this method suggest that, of migrants who have been in the United States for more than one year and less than five years, 130 000 on average exit annually.

Table 3.3. Exit and retention rates of immigrants in the United States after five years of residence

|

Entry cohort |

Deaths (%) |

Exits (%) |

Retention (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2010‑15 |

0.34 |

5.66 |

94 |

|

2011‑16 |

0.32 |

13.45 |

86.22 |

|

2012‑17 |

0.35 |

9.78 |

89.87 |

|

2013‑18 |

0.33 |

14.97 |

84.70 |

|

2014‑19 |

0.34 |

18.55 |

81.12 |

|

Average |

0.34 |

12.48 |

87.18 |

Note: Entry period 2010‑15. Population aged 15 and older.

The columns add to 100%

Source: Own calculations using American Community Surveys.

Comparing the top ten origin countries of immigrants at entry with the top countries of immigrants remaining in the United States after five years shows that Chinese, Indian and Canadian immigrants are more likely to return (Table 3.4).

Table 3.4. Top 10 origin countries of immigrants at entry and after five years

|

At Entry |

Five years later |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Country of origin |

Share (%) |

Country |

Share (%) |

|

India |

11.66 |

Mexico |

13.73 |

|

Mexico |

11.52 |

India |

10.49 |

|

China (People’s Republic of) |

10.24 |

China (People’s Republic of) |

8.03 |

|

Philippines |

3.81 |

Philippines |

4.08 |

|

Cuba |

3.06 |

Cuba |

3.97 |

|

Canada |

2.76 |

Dominican Republic |

3.32 |

|

Korea |

2.69 |

El Salvador |

2.92 |

|

Viet Nam |

2.20 |

Guatemala |

2.81 |

|

Dominican Republic |

2.16 |

Viet Nam |

2.79 |

|

El Salvador |

2.03 |

Honduras |

2.02 |

Note: Entry period 2010‑15. Population aged 15 and older.

Source: Own calculations using American Community Surveys.

Several differences can be observed between immigrants at entry and those who remained five years later. While there is no major difference in the gender ratio at entry, there is a higher proportion of women (55%) after five years of residence. In addition, immigrants who arrived prime‑aged are more likely to remain in the United States after five years than the younger or older arrivals (15‑24 and over 65). Similarly, the share of tertiary graduates is slightly higher among those who stayed after five years (58%) compared to at entry (55%).2 As a higher proportion of the remaining group is employed (66%) than at entry (42%), it can be assumed that many immigrants who have stayed entered the labour market or that a significant proportion of those who have left were inactive.

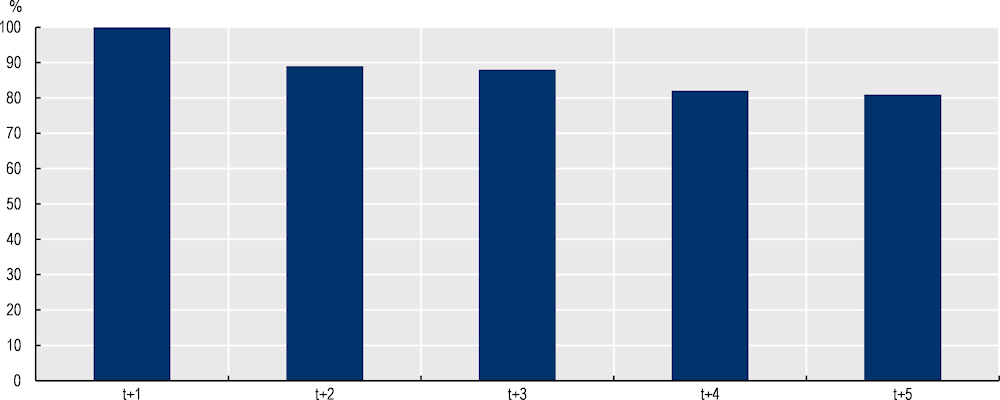

Retention rates fall over time, as shown in Figure 3.5. Of those who arrived in 2014, 89% are still in the United States after two years. After three and four years, retention rates drop to 88% and 82% respectively. After five years, 81% of those who arrived in 2014 are still in the country.

Figure 3.5. Retention rates over time for immigrants entering the United States in 2014

Note: Population aged 15 years and over.

Source: Own calculations using the 2014‑20 American Community Surveys.

Average exit and retention rates of immigrants in the United States can be measured using a different method3 that accounts for possible over-representation in the third and fifth year.

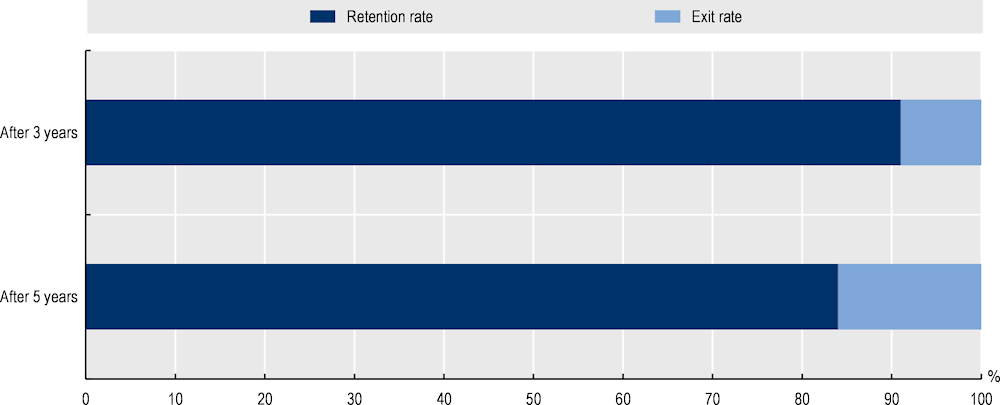

Figure 3.6 shows that the exit rate rises to 16% after five years, with 84% of immigrants still residing in the United States. The exit rate obtained by this method is slightly higher than the rate of 12.5%, which can be attributed to the lower exit rate of 6% observed between 2010 and 2014.

Figure 3.6. Retention and exit rates of immigrants after three and five years in the United States

Note: Population aged 15 and over. Entry period 2010‑15.

Source: Own calculations using American Community Surveys.

3.1.3. Canada

The same analysis to estimate exit rates and identify main socio-economic characteristics of immigrants at entry and five years later was conducted for Canada, using data from the 2011 and 2016 general population censuses. The results summarised in Table 3.5 reveal that 21% of the 223 390 immigrants who arrived in Canada in 2010 had left by 2015. Of the 79% who remained in the country, 44% became Canadian citizens and 35% remained immigrants.

Table 3.5. Status of immigrants who entered Canada in 2010, five years later

|

Variables |

Number |

Share (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Inflows |

223 390 |

100 |

|

Deaths |

393 |

0.2 |

|

Total remaining |

177 082 |

79.3 |

|

of which |

||

|

Naturalised |

97 384 |

43.6 |

|

Remaining immigrants |

79 698 |

35.7 |

|

Return migrants |

45 915 |

20.6 |

Note: Deaths in the cohort are estimated using the age‑sex specific death rate for the same period from the Human Mortality Database.

Source: Own calculations using a 2.7% sample from 2011 and 2016 Canadian General Population Censuses.

Table 3.6 displays the proportion of immigrants from the top ten origin countries at entry and those who remained after five years. The results suggest that immigrants from India and the People’s Republic of China (hereafter “China”) were less likely to leave Canada within five years of arrival, while immigrants from the Caribbean and other Asian countries were more likely to leave in the same period.

Table 3.6. Top ten origin countries in Canada in 2010 and 2015

|

At entry (2010) |

Five years later (2015) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Country of origin |

Share (%) |

Country of origin |

Share (%) |

|

Philippines |

16.94 |

Philippines |

16.21 |

|

China (People’s Republic of) |

10.97 |

India |

12.87 |

|

India |

10.16 |

China (People’s Republic of) |

12.18 |

|

Other Asian countries |

9.93 |

Northern Africa |

6.35 |

|

South America |

5.25 |

West Central Asia and the Middle East |

6.29 |

|

Sub-Sahara Africa |

5.08 |

Central/Eastern Europe |

4.53 |

|

Central and Eastern Europe |

4.86 |

Sub-Sahara Africa |

4.28 |

|

Northern Africa |

4.82 |

Other Asian countries |

4.26 |

|

Caribbean and Bermuda |

4.11 |

South America |

3.99 |

|

Eastern Africa |

16.94 |

Caribbean and Bermuda |

3.11 |

Note: Entry period 2010. Population over 15 years.

Source: Own calculations using 2011 and 2016 Canadian General Population Censuses.

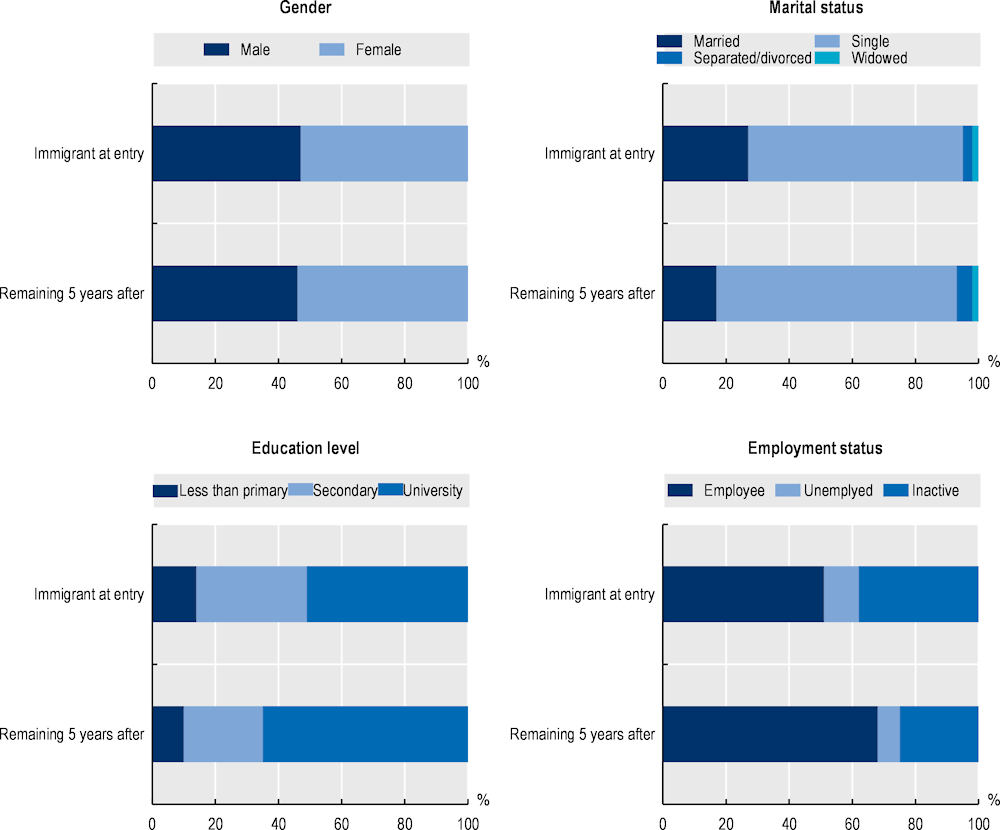

Figure 3.7. Main characteristics of immigrants at entry and after five years

Note: Entry period 2010. Population over 15 years.

Source: Own calculations based on 2011 and 2016 Canadian General Population Censuses

The main socio‑economic characteristics of immigrants at entry and after five years are summarised in Figure 3.7. Men are more likely than women to leave within five years. The proportion of Canadian singles among those who stayed (76%) was higher than at arrival (68%). Unsurprisingly, immigrants who remained after five years had higher levels of education than when they first arrived and were more likely to be employed. This is not only due to selection – they also had a chance to complete more education and to find work.

Box 3.3. Retention rates of immigrants with pre‑admission experience in Canada

Canada’s Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB) provides information on immigrants’ pre‑admission experiences, such as work and study permits or asylum claims. The IMDB also documents the characteristics of immigrants at the time of admission and their economic outcomes and regional mobility over time. To calculate immigrant retention rates at the provincial and Census Metropolitan Area levels, administrative data files on immigrant admissions and non-permanent resident permits are combined with tax files from the Canada Revenue Agency.

Table 3.7 shows that 85% of the immigrants admitted in 2014 filed taxes in their original province or territory of admission five years later. Overall, Ontario had the highest provincial retention rate (94%), followed by British Columbia (90%) and Alberta (89%). The Atlantic provinces had lower retention rates than the rest of the country.

Higher retention rates were observed among immigrants with asylum claims (93%) or work permits only (90%) prior to admission, while lower retention rates were observed among immigrants with study permits only (79%) or study permits in addition to work permits (81%) prior to admission.

Table 3.7. Five‑year retention rates, by pre‑admission experience and province or territory, for the 2014 admission year

|

All (%) |

Study permit (%) |

Work permit (%) |

Asylum claim (%) |

No pre‑admission experience (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Canada |

85.5 |

79.1 |

90.2 |

81.3 |

93 |

|

Newfoundland and Labrador |

46.2 |

N.A |

46 |

45 |

N.A |

|

Prince Edward Island |

28.1 |

22.2 |

50 |

33.3 |

N.A |

|

Nova Scotia |

62.8 |

58.3 |

74.4 |

51.6 |

N.A |

|

New Brunswick |

42.4 |

41.2 |

65.8 |

61.9 |

N.A |

|

Quebec |

79.1 |

61.9 |

92.3 |

83.1 |

92.2 |

|

Ontario |

93.7 |

89.9 |

94.9 |

92.8 |

94.9 |

|

Manitoba |

72.8 |

58.7 |

67.2 |

55.9 |

66.7 |

|

Saskatchewan |

62.7 |

54.5 |

67.3 |

43.1 |

50 |

|

Alberta |

89 |

89.2 |

92.7 |

79.5 |

89.8 |

|

British Columbia |

89.7 |

87.8 |

90.7 |

88.5 |

91.1 |

|

Territories |

67.1 |

N.A |

65.7 |

40 |

N.A |

Source: Canada’s Longitudinal Immigration Database 2020

3.2. Return migration to origin countries

Another approach to examining return patterns is to analyse return rates to origin countries, which is done in this subsection for three regions: Latin America and the Caribbean, North Africa, and Sub-Saharan Africa. These indirect estimates are based primarily on census data, which include a question on country of residence five years prior to the census date and supplemented, where possible, by more recent survey data.

3.2.1. Latin America and the Caribbean

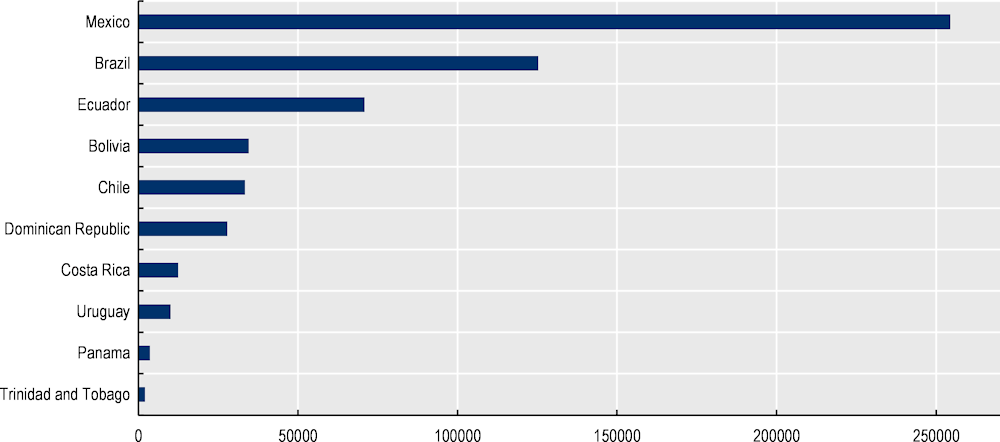

Return rates to LAC countries were estimated indirectly through general population censuses, which include information on previous residence. For Mexico the estimates were obtained from the 2018 National Survey of Demographic Dynamics (ENADID). The review of evidence suggests that Mexico has the highest number of returning migrants in absolute terms (Figure 3.8): A total of 254 422 prior migrants present in Mexico at the time of the survey had returned in the five years prior to the survey.4

Figure 3.8. Number of return migrants in selected LAC countries in the five years preceding survey

Note: The census and survey dates are as follows: Mexico (2018), Brazil (2010), Ecuador (2010), Bolivia (2012), Chile (2017), Dominican Republic (2010), Costa Rica (2011), Uruguay (2010), Panama (2011), Trinidad and Tobago (2010). See Annex B for more details.

Source: Own calculations based on census and national survey data.

60% of all returning migrants in LAC had previously lived in the United States. For four out of ten countries, Spain was the main destination from which migrants returned.

Table 3.8 shows calculation of return rates based on surveys of migrants present in the destination country. Although these surveys have limitations as mentioned above, they are useful to provide a general indication of return rates, which vary considerably. Ecuadorians who have emigrated to Spain have the highest return rate (32%), while Mexicans returning from the United Status have the lowest return rate (3%).

Table 3.8. Proportion of return migrants among migrants from selected Latin American countries

Destination countries: United States and Spain

|

Origin country |

Census year t |

Migrants resident in the destination country and arrived before year t – 5 |

Migrants returned from the destination country after year t – 5 |

Share of migrants returned in year t among migrants living in the destination country in t – 5 (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

United States |

Spain |

United States |

Spain |

United States |

Spain |

||

|

Bolivia |

2012 |

32 278 |

274 704 |

4 359 |

23 634 |

13.50 |

8.60 |

|

Brazil |

2010 |

179 049 |

38 409 |

39 112 |

8 192 |

21.84 |

21.33 |

|

Chile |

2017 |

35 484 |

62 307 |

7 000 |

10 240 |

19.73 |

16.43 |

|

Ecuador |

2010 |

218 592 |

93 067 |

24 280 |

29 780 |

11.11 |

32.00 |

|

Mexico |

2018 |

6 768 484 |

49 165 |

211 902 |

11 085 |

3.13 |

22.55 |

Source: American Community Surveys (2010, 2012, 2017), Spain’s Census of Population and Housing (2011), International Migration Database and origin country population censuses.

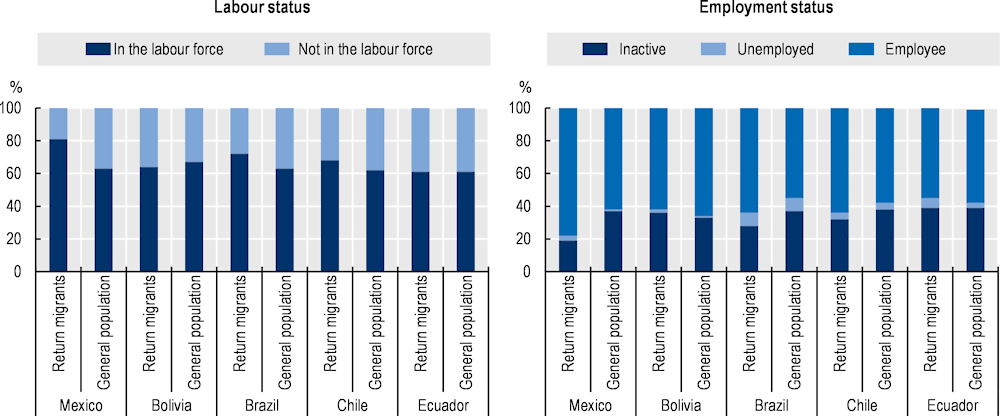

Socio‑economic characteristics in all five countries show that men are over-represented among return migrants. In Mexico, for example, 76% of those who return are male. The estimates further suggest that return migrants are more likely to be married than the general population. The employment rate of return migrants is higher than that of the general population: In Brazil and Chile, more than 60% of return migrants are employed, and in Mexico the employment rate is over 80%. In contrast, return migrants in Ecuador are more likely to be inactive which can be partly explained by returning at a slightly older age than the other three groups (Figure 3.9). Lastly, return migrants tend to have higher levels of education, particularly in Chile, where more than 80% of return migrants have at least secondary education.

Figure 3.9. Labour and employment status of return migrants in selected LAC countries

Note: The census and survey dates are as follows: Mexico (2018), Bolivia (2012), Brazil (2010), Chile (2017), Ecuador (2010). See Annex B for more details.

Source: Own calculations based on national census and survey data.

3.2.2. North Africa: Tunisia and Morocco

Indication on return to North Africa can only be derived from surveys conducted in Tunisia and Morocco. The Household International Migration Surveys in the Mediterranean countries (MED-HIMS), a regional programme of co‑ordinated international migration surveys, were requested by the National Statistical Offices (NSOs) of most countries in the European Neighbourhood Policy – Southern Region. The surveys were conducted in different regions of Morocco and Tunisia and cover a representative sample of households with at least one returning migrant. Given the very different migration profiles of other North African countries, the results cannot be generalised.

In Morocco, the survey estimated the total number of return migrants between 2000 and 2018 at 188 000,5 or an average of 10 000 returns per year (

Table 3.9). France (32%), Italy (22%) and Spain (19%) are the three main countries from which Moroccan migrants return.

Table 3.9. Moroccan return migrants and immigrants in 2018, by region

|

Destination country |

Return migrants |

Current migrants |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number |

Share (%) |

Number |

Share (%) |

Return rate of current migrants (%) |

|

|

Traditional European countries of immigration |

74 260 |

39.5 |

2040 703 |

41.7 |

3.6 |

|

New European countries of immigration |

77 644 |

41.3 |

2060 278 |

42.1 |

3.8 |

|

North America |

8 272 |

4.4 |

362 139 |

7.4 |

2.3 |

|

Middle East and North Africa |

16 356 |

8.7 |

185 963 |

3.8 |

8.8 |

|

Other countries |

11 468 |

6.1 |

244 689 |

5 |

4,7 |

|

Total |

188 000 |

100 |

4 893 773 |

100 |

3.8 |

Note: The new European countries of immigration are Spain and Italy, which attracted massive migration during the 1990s and thereafter. Traditional European countries immigration are Western Europe countries of the first wave of immigration, mainly France, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Germany.

Source: Haut Commissariat au Plan (HCP), Enquête nationale sur la migration internationale 2018‑19.

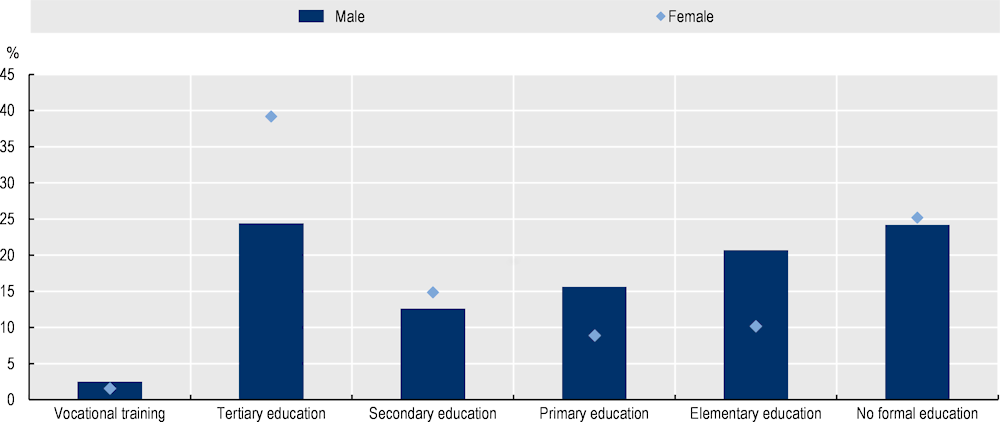

Most return migrants are male (72%) and are aged between 30 and 49 (40%). The survey suggests that the return migrant population includes both highly educated and low educated Moroccans (Figure 3.10). While almost a quarter of Moroccan return migrants have no formal education, close to 30% have completed tertiary education. Female return migrants are more likely to have a university degree (39%) compared to their male counterparts (24%).

Figure 3.10. Education level of Moroccan return migrants, by gender

Note: N= 188 000.

Source: Haut Commissariat au Plan (HCP), Enquête nationale sur la migration internationale 2018‑19.

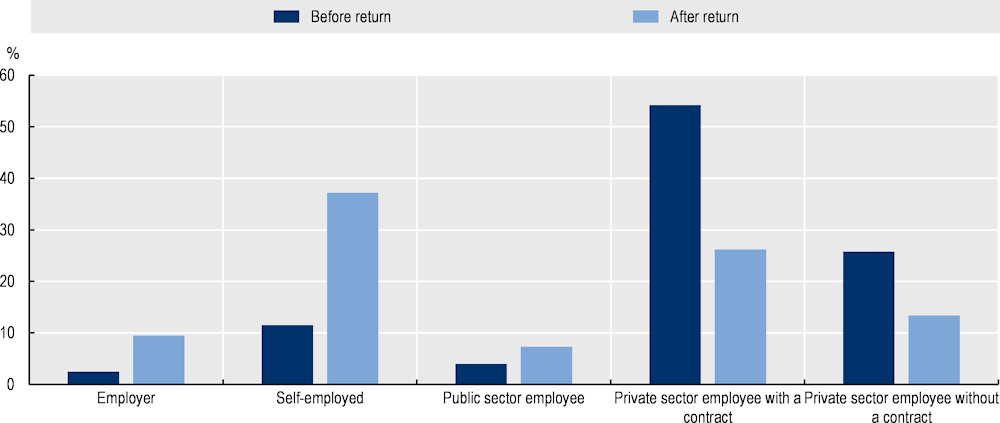

Moroccans who return to their home country do not take up the same jobs they had before they left. There is a clear shift in the occupational structure of Moroccans after their return. In destination countries, 84% were employed and only a small proportion were self-employed (14%). This proportion increased to 47% after return.

Figure 3.11. Employment status of Moroccan return migrants

Note: N=188 000.

Source: Haut Commissariat au Plan (HCP), Enquête nationale sur la migration internationale 2018‑19.

The MED-HIMS survey also sheds light on return patterns in Tunisia. The survey estimates the number of return migrants at 210 848. Most return migrants are male (83.5%). Many of the return migrants have been back in Tunisia for more than two decades: only 55% returned between 2000 and 2020. This may explain why such a large share are retired (60%).

Tunisian migrants return mainly from three countries: Neighbouring Libya (34%), France (32%) and Italy (12%). In addition, return migration from the Gulf countries, including Saudi Arabia, Oman, the United Arab Emirates and Qatar, accounts for 12% of all returns. Almost 50% of Tunisians who returned lived abroad for less than five years, as shown in Table 3.10. These findings may indicate that the propensity to return decreases with the number of years spent in the destination country or may reflect that emigration has become more frequent in recent years and a larger number of Tunisians are now abroad, increasing the number of potential returns after short stays.

Table 3.10. Tunisian return migrants according to the length of stay in destination countries

|

Number of years spent abroad |

Number |

Share (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

0‑2 |

57 594 |

27.3 |

|

2‑5 |

41 853 |

19.9 |

|

5‑10 |

38 246 |

18.1 |

|

10‑15 |

19 932 |

9.5 |

|

15‑20 |

11 748 |

5.6 |

Source: Institut National de la Statistique, l’enquête nationale sur les migrations internationales (MED-HIMS), 2021.

The socio‑economic characteristics of Tunisian return migrants show that the majority are low educated, with 17% having no formal education and 38% having completed primary education. Tunisian return migrants are also less likely to work than before they emigrated. This may be explained by a higher proportion of retired people and a much lower employment rate and higher share of inactive women (Table 3.11), even if women only comprise a small part of the total. Of those in employment, 65% have a formal work contract and 35% are self-employed.

Table 3.11. Employment status of Tunisian return migrants

|

Status |

Male (%) |

Female (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Employed |

46.1 |

18.9 |

|

Unemployed |

8.9 |

6.7 |

|

Inactive |

45 |

74.4 |

|

Total |

100 |

100 |

Note: N= 210 848.

Source: Institut National de la Statistique, l’enquête nationale sur les migrations internationales (MED-HIMS), 2021.

This section presented the results of surveys. These surveys indicate return flows which are more modest than those suggested by other sources, such as censuses and by the exits from major destination countries in the OECD. This indicates that much of return migration is not captured by existing statistical systems or by the surveys designed to examine migration movements.

3.2.3. Sub-Saharan Africa: analysis of 8 countries

For Sub-Saharan Africa, return rates can be estimated indirectly using a 10% sample of general population censuses.6 The information on residence five years prior to the census can be used to estimate the number of return migrants for different countries of previous residence and to compare it with the number of people who never left the origin country (general population). However, as most of these censuses were conducted more than a decade ago, they do not reflect return patterns in recent years. These returns appear low in absolute numbers.

Mali has the highest number of return migrants among the Sub-Saharan African countries covered in this report. According to the 2009 census, 14 730 migrants returned in the five years prior to the census. Significant numbers of Senegalese and Mauritanian migrants also return from OECD countries (Figure 3.12).

Figure 3.12. Return migrants from selected Sub-Saharan countries in the five years preceding the census

Note: The census year for each country is as follows: Mali (2009), Senegal (2013), Mauritius (2011), Botswana (2011), Rwanda (2012), Sierra Leone (2015), Benin (2013), Togo (2010). See Annex B for more details.

Source: Own calculations based on national census data.

Europe was the main destination for most Sub-Saharan African migrants. Malian migrants primarily return from France (36%), as do Senegalese return migrants (37%). A significant proportion of Senegalese also returned from Italy (34%). The United Kingdom is the main destination for Mauritian (46%) and Botswana (30%) return migrants. In Rwanda, 46% of return migrants resided in European countries, with at least 17% returning from Belgium.

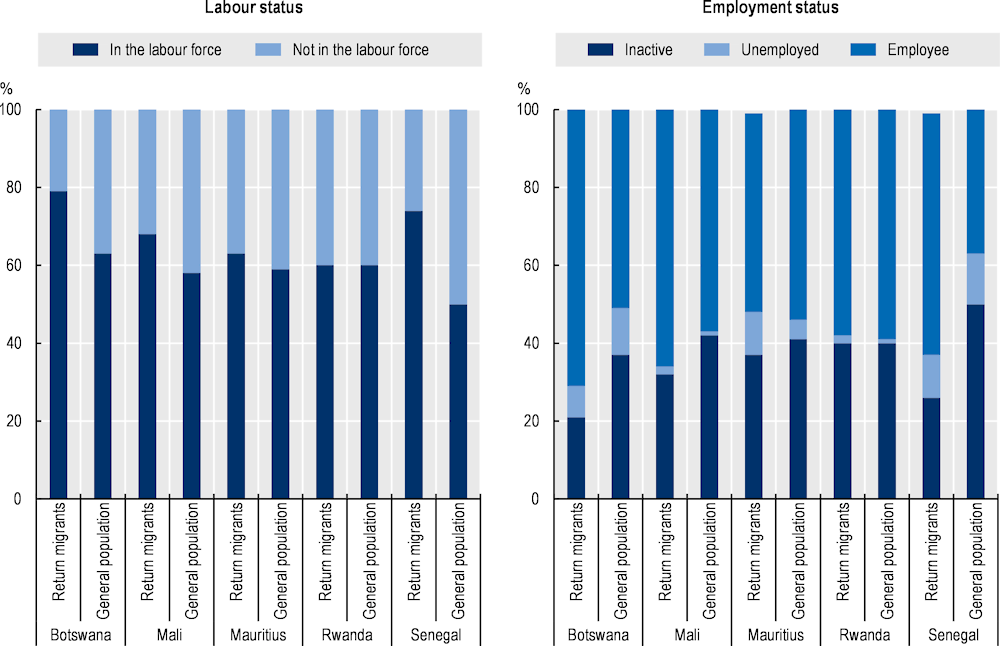

The average age of return migrants varies across countries. In Botswana, Mauritius and Rwanda, return migrants are on average 30 years old, while in Mali there are three peaks in the age distribution: at 30, 45 and close to retirement. The gender distribution also differs between countries. Senegal and Mali clearly stand out with a very high proportion of male return migrants (80% and 66% respectively), while in the other countries the gender ratio is almost the same as in the general population. Lastly, the employment rate of return migrants is higher than that of the general population in all five countries (Figure 3.13).

Figure 3.13. Labour and employment status of return migrants, Sub-Sahara Africa

Note: The census year for each country is as follows: Botswana (2011), Mali (2009), Mauritius (2011), Rwanda (2012) and Senegal (2013). See Annex B for more details.

Source: Own calculations based on national census data.

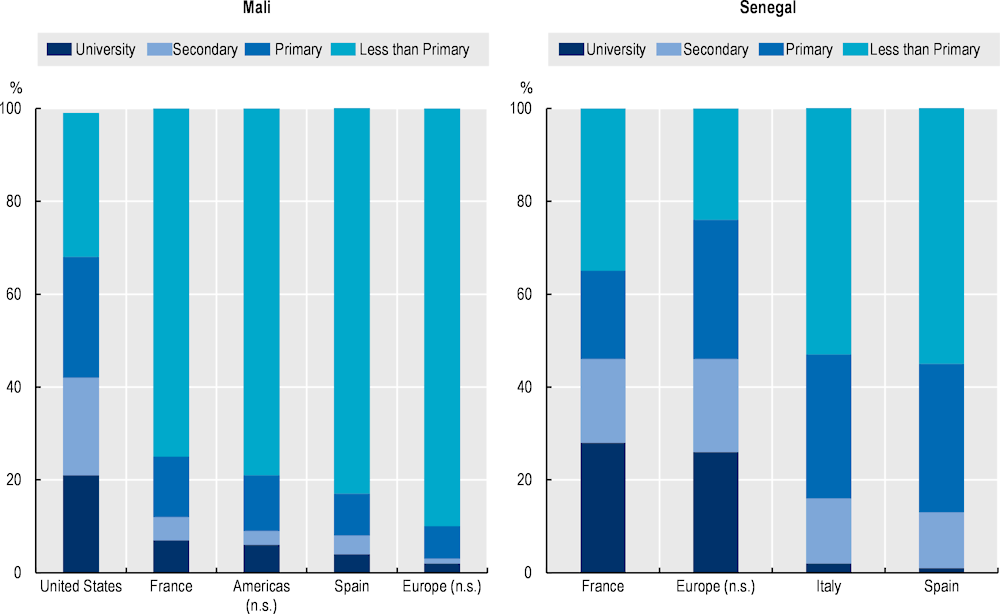

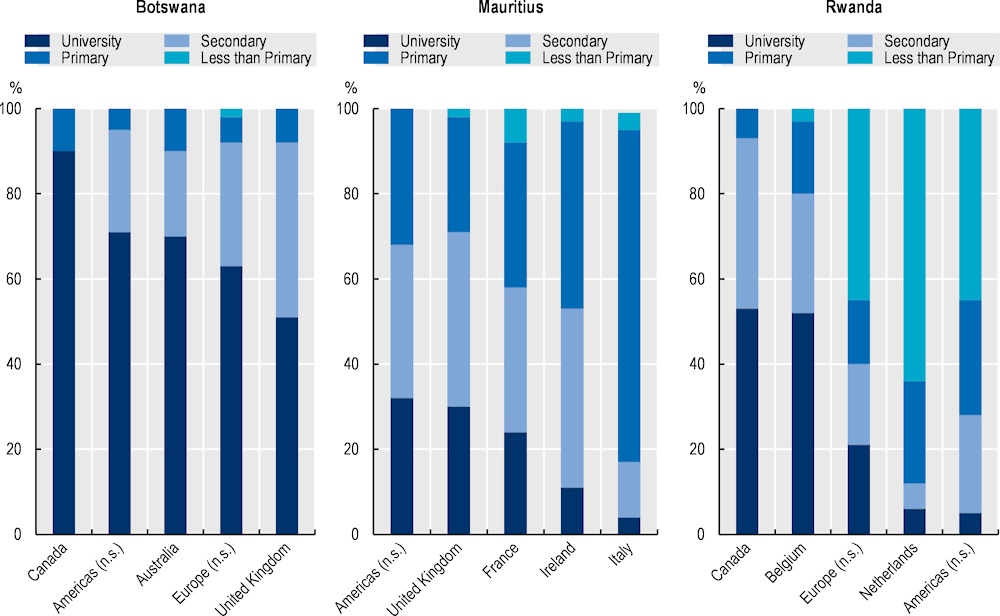

The results also suggest that the educational attainment of return migrants is higher than the national average. In Botswana, almost 90% of return migrants from Canada have completed tertiary education compared to 50% of those who emigrated to the United Kingdom. In Rwanda, the most educated return migrants have previously lived in Canada and Belgium (Figure 3.14).

Figure 3.14. Education level of return migrants, Sub-Saharan Africa

Note: The census year for each country is as follows: Botswana (2011), Mali (2009), Mauritius (2011), Rwanda (2012) and Senegal (2013). See Annex B for more details.

Source: Own calculations based on national census data

This section presents analyses based on the limited data available, much of which dates back more than a decade. Surveys are thin, and administrative data limited, so it is difficult to draw a more detailed picture of return migration.

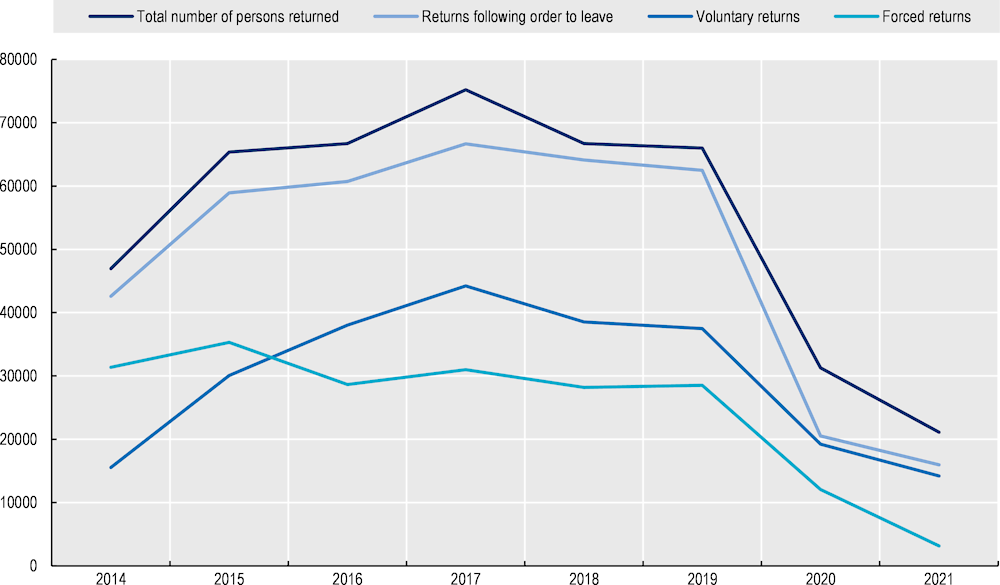

3.2.4. The scale of return of third-country nationals leaving the EU

Eurostat has since 2014 collected data on the return of third-country nationals from EU countries. Return movements in this dataset cover forced and voluntary returns. The data also capture persons who returned following an official order to leave (Figure 3.15). However, the voluntary nature of data reporting leads to some gaps. EU Member States with significant migration flows, such as Germany, Greece and the Netherlands, have partial data: while there is data on third-country nationals who have returned following an order to leave, it is unclear which returns are voluntary and which are forced. Spontaneous departures are usually not recorded.

Despite these limitations, Eurostat data provides some indication of trends in the return of third-country nationals. Before the start of the COVID‑19 pandemic (2014‑19), the average number of documented returns across EU countries was 82 000, peaking in 2017 with an average of 93 000 returns. Due to pandemic-related restrictions, the actual number of returns decreased significantly in 2020 and 2021, averaging 47 000 and 29 000, respectively, across EU countries with available data. Almost 90% of all reported returns correspond to third-country nationals returning following an official order to leave the country.

Eurostat data further highlights that forced returns are relatively small compared to overall return movements. Between 2014 and 2021, there were on average 35 000 forced returns per year across EU countries. This figure is low compared to the estimated exits rates of migrants in OECD EU countries (Section 3.1.1). However, forced returns appear to account for at least half of the returns reported in the Eurostat data. Only in 2021 does the share of forced returns decrease (21%) in the COVID‑19 context.

Figure 3.15. Number of third country nationals returned in selected EU countries, by type of return, 2014‑21

Note: The figure shows the number of annual returns reported by 16 EU OECD countries for which data was available in all four categories.

Source: Eurostat.

3.2.5. The scale of AVRR in return movements

There is a separate data source indicating the scale of AVRR. Compared to estimates of return migration derived from surveys and census data, AVRR in origin countries appear to comprise a very low share of returns (Table 3.12). In Mexico, for example, the 2018 National Survey of Demographic Dynamics reported that an estimated 254 422 migrants had returned five years prior to the survey, while only 178 return migrants received AVRR assistance between 2013 and 2018.

In Morocco, annual return estimates since 2000 range from 10 000 to 40 000 depending on the data source, far exceeding the 4 800 return migrants who have received AVRR assistance between 2013 and 2022. In Tunisia, the MED-HIMS survey indicates that approximately 115 966 migrants returned between 2000 and 2020, with an average of 5 800 returns per year, which is much higher than the annual average of 183 return migrants who received AVRR since 2013. These figures suggest that AVRR represents only a small fraction – at best 5% – of total return movements in these regions. The fact that not all migrants qualify for AVRR support explains part of this discrepancy.

As for Sub-Saharan Africa, there is a noticeable increase in AVRR beneficiaries – particularly in Mali, Senegal and Sierra Leone – but outdated census data complicates comparisons of AVRR with other return movements. Estimates of exit rates from EU countries suggest that 32% of immigrants from Sub-Saharan African leave within 3 years and 37% within 5 years (Figure 3.3).

Table 3.12. Assisted voluntary returns, by country of origin, 2013‑22

|

2013 |

2014 |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

2018 |

2019 |

2020 |

2021 |

2022 |

Total (2013‑22) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Latin America and the Caribbean |

|||||||||||

|

Bolivia |

225 |

183 |

79 |

53 |

47 |

22 |

15 |

21 |

19 |

38 |

702 |

|

Brazil |

1 418 |

881 |

578 |

496 |

700 |

810 |

815 |

1 249 |

556 |

1 249 |

7 503 |

|

Chile |

169 |

120 |

66 |

69 |

38 |

69 |

45 |

46 |

19 |

29 |

670 |

|

Costa Rica |

1 |

7 |

4 |

4 |

6 |

1 |

4 |

38 |

29 |

19 |

113 |

|

Ecuador |

356 |

276 |

88 |

30 |

37 |

27 |

35 |

9 |

16 |

88 |

962 |

|

Mexico |

56 |

45 |

13 |

16 |

18 |

30 |

55 |

20 |

49 |

63 |

365 |

|

Uruguay |

42 |

33 |

25 |

22 |

22 |

8 |

6 |

41 |

23 |

14 |

236 |

|

North Africa |

|||||||||||

|

Morocco |

482 |

416 |

308 |

1 395 |

477 |

348 |

310 |

184 |

258 |

640 |

4 818 |

|

Tunisia |

609 |

139 |

79 |

109 |

120 |

160 |

149 |

123 |

113 |

232 |

1 833 |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa |

|||||||||||

|

Botswana |

12 |

3 |

4 |

9 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

5 |

48 |

|

Benin |

73 |

19 |

19 |

38 |

84 |

185 |

816 |

341 |

338 |

231 |

2 144 |

|

Mali |

173 |

126 |

719 |

408 |

724 |

4 041 |

6 799 |

3 249 |

4 453 |

6 624 |

19 614 |

|

Mauritius |

58 |

31 |

21 |

8 |

17 |

15 |

8 |

13 |

8 |

1 |

180 |

|

Rwanda |

35 |

21 |

18 |

16 |

15 |

30 |

18 |

10 |

17 |

10 |

190 |

|

Senegal |

328 |

283 |

743 |

1 527 |

1986 |

1 495 |

1 206 |

695 |

1 104 |

1 064 |

9 327 |

|

Sierra Leone |

37 |

23 |

32 |

97 |

177 |

829 |

1 823 |

1 259 |

1 793 |

2 249 |

5 267 |

|

Togo |

74 |

31 |

21 |

36 |

104 |

121 |

153 |

118 |

140 |

122 |

920 |

Source: IOM, Return and Reintegration Highlights 2022, Annexes.

3.3. Conclusion

In conclusion, this section examined exit rates from OECD countries and return rates to origin countries, highlighting the factors that influence return patterns. The analysis shows that exit rates vary considerably between countries, ranging from 12.5% in the United States to 75% in the Netherlands. The low exit rates in the United States can be explained by the large number of migrants from Mexico, the Philippines and Cuba, whose return rates are generally lower. In contrast, the Netherlands has a higher proportion of immigrants from high-income countries such as Poland, Germany and China, who are more likely to return within five years. Retention rates also vary by region of origin. In European OECD countries, immigrants from Latin America and the Caribbean, North Africa and the Middle East have higher retention rates than those from North America.

The retention rate continues to decline between three and five years. A large part of the exits is of migrants who are therefore departing with 3‑5 years of experience in the destination country – a period long enough to have potentially acquired human capital in the form of language, education or professional experience.

The analysis of return migration to origin countries highlighted that a significant number of return migrants from LAC countries have previously resided in the United States and Spain, while European countries are the main destination for African return migrants. The subsection also showed that return rates for LAC countries are slightly higher than for sub-Saharan African countries when considering the total number of immigrants residing in the selected destination countries. Compared to the general population, return migrants tend to have higher levels of education and higher employment rates.

The magnitude of the return migration phenomenon is indicated by these rates. For large countries like the United States, where well over a million new migrants enter annually, even an exit rate of one in eight represents hundreds of thousands of returning migrants each year. Similarly, in Europe, even with low exit rates for many non-EU born migrants, the magnitude of inflows is similar to that of the United States and the exits still amount to hundreds of thousands annually. The picture which emerges from this analysis is that of OECD destinations from which there are very significant outflows. Not all exits are for return to the origin country – some may be secondary movements within the OECD or to new destinations. However, return migration from OECD countries to origin countries is in the order of many hundreds of thousands per year.

References

[1] OECD (2008), International Migration Outlook 2008, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/migr_outlook-2008-en.

Notes

← 1. EU‑27 and the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries.

← 2. This is calculated on population age 15 and over, so some have not had the chance yet to complete their education.

← 3. The envelope method, similar to the one used by (OECD, 2008[1]) consists in reallocating non-response proportionally to the weights of the different length-of-stay responses to maintain the total number of immigrants. To account for sample size volatility, the data is smoothed by constructing an envelope around the initial cohort so that the number of immigrants retained for a given length of stay is the average between the maximum and minimum values in the envelope.

← 4. For more information on methodology see Annex A.

← 5. The HCP survey defines a return migrant as a household member born in Morocco who has lived in another country for at least three months and has returned to Morocco since the beginning of 2000.The survey counts 187 566 return migrants to Morocco since 2000, an average of around 10 000 per year. These numbers are than those estimated by the 2014 General Census of Population and Housing, which reported the number of return migrants between 2000 and 2014 at 200 000, an average of 40 000 return migrants per year.

← 6. These are drawn from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series International (IPUMS-International), the largest collection of publicly available individual-level census data.