This section provides the background and rationale for the review, including the main objectives and the criteria used for selecting measures to be included in the inventory. It also includes a high-level overview of the social, human rights and environmental risks often associated with agricultural supply chains and the activities undertaken by business and policy makers to address these risks.

Review of G7 Government-led Voluntary and Mandatory Due Diligence Measures for Sustainable Agri-food Supply Chains

1. Background and rationale

Copy link to 1. Background and rationaleAbstract

The FAO defines agri-food systems as those that encompass the entire range of actors, and their interlinked value-adding activities, engaged in the primary production of food and non-food agricultural products, as well as in storage, aggregation, post-harvest handling, transportation, processing, distribution, marketing, disposal and consumption of all food products including those of non-agricultural origin (FAO, 2021[1]). This report explores measures to address the social and environmental impacts of activities across agri-food systems and supply chains, both within G7 countries and abroad.

International trade in food and agricultural products has more than doubled since 1995, with emerging and developing economies accounting for one-third of total exports globally. However, the importance of international trade differs depending on the type of agricultural commodity; it is particularly high for tropical commodities but lower for most other agricultural commodities. Where international trade plays a major role, responsible business conduct can be improved not only through policy measures in the country of production, but also through interventions along the length of the supply chain through to the end consumer.

This work aims to provide G7 agricultural policy makers with insights to better understand the design, objectives and mechanisms of national and regional policy measures that seek to promote due diligence to address environmental and social impacts in agricultural supply chains. The OECD applied two criteria to select the measures and compile the inventory (1) the initiative is led, mandated or formally supported by a G7 government (and/or EU), and (2) the initiative has a due diligence component (i.e., either a conduct or disclosure expectation related to RBC supply chain due diligence). The review also aims to help industry actors understand the identified policy measures by highlighting synergies and discrepancies to enable and support effective implementation.

The project was structured in three main phases:

1. Desktop research, interviews and a review of identified due diligence-related policy measures in G7 countries and the EU (see selective inventory in Annex A);

2. An analysis of the identified measures to better understand their commonalities and discrepancies as well as the extent to which they draw on key elements of the OECD-FAO Guidance on Responsible Business Conduct and the Due Diligence Guidance for RBC; and

3. High-level analysis of impacts, challenges and barriers for due diligence implementation, including those related to a lack of harmonisation.

The project included regular and ongoing involvement of an informal consultation group composed of G7 and EU policy makers from agricultural ministries as well as consultations with business associations, civil society organisations and experts. This paper presents the findings from the three phases.

1.1. RBC risks in agri-food systems

Copy link to 1.1. RBC risks in agri-food systems1.1.1. Social and human rights risks

Copy link to 1.1.1. Social and human rights risksAgriculture1 remains a key source of economic growth in many countries, creating employment for 874 million people worldwide and accounting for nearly 60% of total employment in low-income countries (ILO, 2020[2]). Globally, food systems need to meet the triple challenge of ensuring food security and nutrition for a growing population, providing livelihoods for farmers and others working along food supply chains, and improving the environmental sustainability of the sector (OECD, 2021[3]).

However, the agricultural sector is still associated with severe human and labour rights impacts (Jacobs, Brahic and Olaiya, 2015[4]). The sector accounts for more than 70% of global child labour, over 112 million children (ILO, UNICEF, 2021[5]). Incidences of forced labour are of particular concern in the plantation sector, which dominates as a production system for many tropical agricultural commodities (ILO, 2017[6]). Agriculture remains one of the most hazardous sectors in terms of fatal and non-fatal workplace accidents and occupational diseases – especially in fishing and farming, which are prone to occupational health and safety risks. Globally, 27% of farmers, farmworkers, fishers and agricultural labourers were recorded to have been seriously injured while working (The Lloyd's Register Foundation, 2019[7]). The sector is also associated with gender-based violence and harassment and women are much less likely to have legal title to the land they cultivate; women account for almost 40% of the agricultural workforce worldwide yet only 15% of all landholders are women (FAO, 2018[8]; FAO, 2023[9]).

Agriculture has also been associated with adverse impacts on Indigenous Peoples and the risk of adverse human rights impacts associated with large-scale land acquisitions. Among 39 large-scale agri-business investments analysed by the World Bank and UNCTAD, land tenure was identified as the most common cause of grievances for affected communities, particularly due to disputes over land over which communities had informal land use rights and to a lack of transparency, especially on conditions and process for land acquisition (James Zhan, 2015[10]).

1.1.2. Environmental risks

Copy link to 1.1.2. Environmental risksAgriculture relies heavily on nature and ecosystem services and exerts significant pressures on the planet. Agri-food products pass through a number of stages before they reach the consumer, with different environmental impacts at each stage of the supply chain.

Greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (both through the emission of gasses such as CO2, Nitrous Oxide and methane, as well as the depletion of carbon sinks). In 2015, the food system contributed to one-third of total anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (Crippa et al., 2021[11]). While absolute food-system related annual GHG emissions increased by 12.5% from 16 GtCO2e in 1990 to 18 Gt CO2e in 2015, their relative share in global GHG emissions decreased from 44% in 1990 to 34% in 2015 (Crippa et al., 2021[11]).

Greenhouse gas emissions are not evenly distributed across the supply chain, different geographies, and producers (Deconinck and Toyama, 2022[12]). For example, agriculture and related land-use change make up approximately 71% of food-related emissions (Crippa et al., 2021[11]), with the remainder driven by both downstream (e.g., transport, processing, retail, packaging, waste) and other upstream (fuel production) activities. Notably, 27% of land-use emissions are linked to agricultural products consumed in regions different from their production origin, with embodied trade emissions stemming primarily from low-income countries in the Southern hemisphere whose carbon-rich and biodiverse ecosystems are frequently cleared to facilitate the export of agricultural commodities to wealthier or more densely populated regions (Hong et al., 2022[13]).

At the same time, food systems are highly vulnerable to climate impacts and associated biodiversity loss, extreme weather events and ecosystem deterioration, which will pose challenges for how food is produced, transported and consumed and have cascading effects on food security, nutrition, poverty and livelihoods.

Water consumption and soil pollution: agriculture is the world’s largest water user, accounting for more than 70% of global water withdrawals (FAO, 2020a[14]) and 78% of global ocean and freshwater eutrophication is caused by agriculture (Poore and Nemecek, 2018[15]). Half of the world’s habitable land is used for agriculture, while excessive use of pesticides and fertilizers leads to soil degradation (Poore and Nemecek, 2018[15]).

Biodiversity loss and deforestation: multiple studies confirm that commercial agriculture is by far the largest driver of deforestation, with a significant and growing share of the commodities produced on recently deforested lands. As the demand for agricultural products grows, agriculture often expands into forests and other valuable ecosystems (FAO, 2020a[14]).

Agri-food products pass through a number of stages during their lifecycle, with different environmental impacts at each stage. A full scoping of the environmental impacts of food systems should therefore consider impacts at each stage, including those indirectly caused by input use (e.g., GHG emissions related to energy used in food production); potential land use impacts (e.g., when greater demand for a product contributes to deforestation); and the role of waste (including food loss and waste, as well as waste of, for example, packaging materials). It should also take into account a broad range of relevant environmental impacts (i.e., not only GHG emissions but also eutrophication, acidification, biodiversity impacts, etc.).

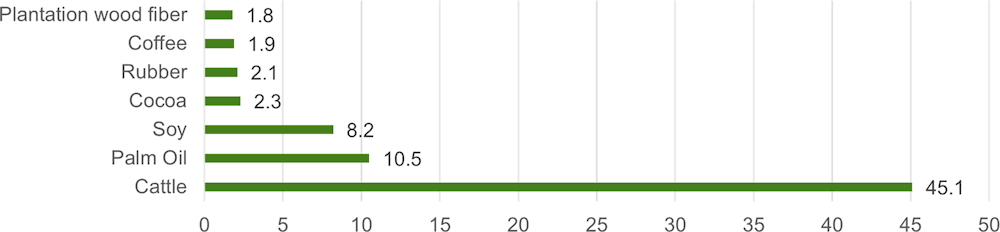

Figure 1.1. Total forest replacement by analyzed commodities (2001- 2015, million hectares)

Copy link to Figure 1.1. Total forest replacement by analyzed commodities (2001- 2015, million hectares)A small group of commodities have received wider attention as recently deforested lands are often used for their production (see Figure 1.1). These include beef, dairy products and leather from cattle, soybeans, palm oil, cocoa, coffee, wood and rubber. Commodities cultivated or grown in an area after it is deforested are considered as “direct drivers” of deforestation. New analysis from the Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU) estimates that between 2005 and 2017, G7 members (including the EU) were responsible for 30% of tropical deforestation linked to imports of agricultural commodities; this contributed over 2.7 billion tCO2 (FOLU, 2022[17]). Other commodities identified as drivers of deforestation, though on a smaller scale than those listed above, include maize, sugar cane, coconut, tea, rice and avocados. In practice almost any crop or form of pasture has the potential to contribute to deforestation. It is now widely recognised that addressing these environmental pressures will require action not only by agricultural producers, but also by other supply chain actors, consumers, and policy makers.

1.2. Agri-business commitments and action

Copy link to 1.2. Agri-business commitments and actionTo respond to these evolving risks and impacts, several industry commitments have been made and private sector initiatives established.2 Companies increasingly recognise that they have a role to play in the way that business and investment decisions can affect people and the environment through their supply chains. Many enterprises have for example endorsed the New York Declaration on Forests (Forest declaration, 2014[18]) which focuses on eliminating deforestation from the production of agricultural commodities amongst others. International standard setting bodies, such as ISO, and national level counterparts are also increasingly developing environmental and social standards to meet business demand.

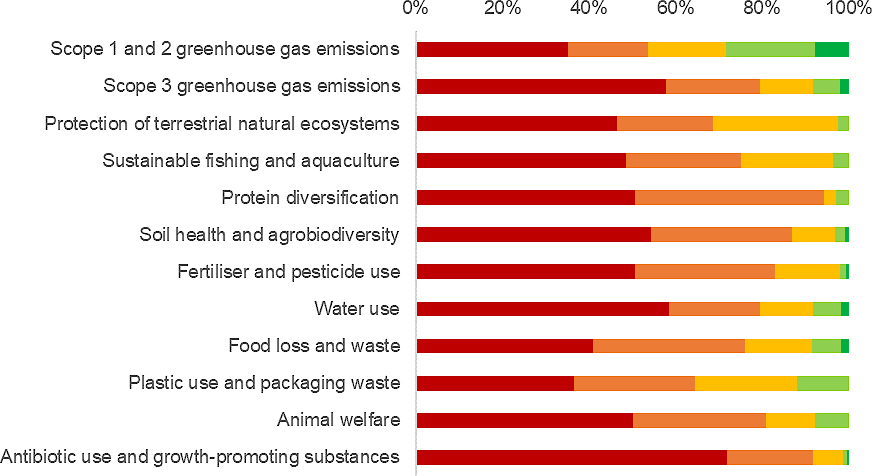

However, an evaluation of the world’s 350 major food and agriculture enterprises by the World Benchmarking Alliance (WBA) noted that whereas 73% disclose a sustainable development strategy, only 7.4% have set GHG reduction targets aligned with the global temperature goals in the Paris Agreement, and only 11% have defined strategies to address a number of key RBC-related risks and impacts (which broadly correspond to the different dimensions of the OECD-FAO Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains). Nearly 55% have no targets related to global deforestation and conversion commitments for high-risk commodity chains. The vast majority lack comprehensive commitments and procedures prohibiting child and forced labour in their operations and supply chain and less than 10% could demonstrate having a full human rights due diligence process in place (World Benchmarking Alliance, 2021[19]).3

Figure 1.2. Distribution of firms’ environmental scores in WBA Food and Agriculture Benchmark

Copy link to Figure 1.2. Distribution of firms’ environmental scores in WBA Food and Agriculture Benchmark

Note: The World Benchmarking Alliance assigns scores on a five-point scale: 0 (lowest score, here in red), 0.5 (orange), 1 (yellow), 1.5 (light green), 2 (the highest possible score, shown here in dark green). For more information on the WBA Agriculture Benchmark methodology please see https://assets.worldbenchmarkingalliance.org/app/uploads/2021/02/Food-and-Agriculture-Benchmark-methodology-report.pdf

Source: (World Benchmarking Alliance, 2021[19]) taken from (OECD, 2022[20]).

1.3. Policy responses from G7 members

Copy link to 1.3. Policy responses from G7 membersG7 countries are increasingly acting in response to growing concerns about environmental and social risks and impacts in agricultural supply chains and the ability of voluntary initiatives and private-led commitments to prevent, mitigate and remediate those impacts (WEF, 2022[21]).

For example, in June 2021, G7 leaders committed to eradicating forced labour from global supply chains, a call that was reiterated in 2022 and 2023 (G7, 2022[22]) (G7, 2023[23]). They tasked G7 trade ministers with identifying areas for strengthened cooperation and collective efforts to achieve this goal (G7, 2021[24]). At COP26 in November 2021, 141 countries signed the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use, enshrining a global vision of forest conservation and restoration. It constitutes an unprecedented commitment to halt and reverse forest loss and land degradation by 2030, anchored in notions of sustainable development and inclusive rural transformation (COP26, 2021[25]).

At the regional and national level these international commitments are reflected in a variety of policy and regulatory measures aimed at addressing RBC risks. These can range from broad overarching strategies to targeted regulation that addresses a specific issue. For example, the EU Green Deal is a package of policy initiatives, which aims to set the EU on the path to a green transition, with the ultimate goal of reaching climate neutrality by 2050. The package includes initiatives covering the climate, the environment, energy, transport, industry, agriculture and sustainable finance – all of which are strongly interlinked. While at the regional and national level, legislation has been introduced to tackle targeted issues like deforestation and forced labour.

Box 1.1. G7 Sustainable Supply Chains Initiative (SSCI)

Copy link to Box 1.1. G7 Sustainable Supply Chains Initiative (SSCI)In December 2021, the G7 under the UK G7 presidency launched the Sustainable Supply Chains Initiative (SSCI) together with commitments from CEOs from a wide range of agri-food companies headquartered in G7 countries. Support for this initiative has continued under the German G7 presidency in 2022. Today, it brings together 22 global food and agriculture companies that have pledged to improve the environmental, social and nutritional impact of their operations and supply chains globally. Collectively, these companies earn over 500 billion USD in annual global revenue and employ over 2 million people directly, influencing many more through their supply chains and business relationships. The objective of this initiative is to accelerate global progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and to transform food systems to be more sustainable, inclusive, and resilient (G7 SSCI, 2021[26]).

One year on, in December 2022, companies signed a Statement on Delivering Sustainable Agricultural Supply Chains, in which they recognise the urgency of addressing the challenges of providing food security and nutrition to growing global populations, providing livelihoods to farmers and workers in food supply chains, and addressing environmental concerns including climate change. Companies from G7 countries committed to pursuing sustainable agricultural supply chains and reducing the climate impacts of their business operations and supply chains. They also called on governments to, among other things, create an appropriate forum that can “further the implementation of the OECD-FAO Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains as a means to guide corporate action on addressing impacts” (G7 SSCI, 2022[27]).

As recognised in the recent OECD Ministerial Declaration on Promoting and Enabling Responsible Business Conduct in the Global Economy, a smart mix of government measures to promote RBC due diligence may include mandatory and voluntary approaches4 as well as capacity building and other accompanying measures (OECD, 2023[28]). Governments have a wide range of mandatory and voluntary policy tools at their disposal to promote, incentivise or mandate companies to conduct RBC due diligence on their global operations, supply chains and other business relationships. These include trade and investment policy tools, public procurement measures, as well as government guidance or government-led partnerships and initiatives to raise awareness and promote dialogue and collaboration with supply chain actors and other stakeholders. Due diligence processes can also be incentivised through mandatory due diligence, corporate due diligence disclosure requirements (where companies are asked to report on due diligence) or through trade-based measures (where due diligence or ‘due care’ can help demonstrate or rebut a presumption that a supply chain of a product is associated with a specific risk e.g., forced labour, deforestation) amongst others. These measures are often complementary, self-reinforcing and form part of a wider smart mix of measures.

Notes

Copy link to Notes← 1. RBC risks refer specifically to the risks of adverse impacts with respect to issues covered by the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct — impacts on society (including human rights and labour), governance and the environment.

← 2. For example, the BSI standard, BS 25700: Organizational responses to modern slavery - Guidance

← 3. The World Benchmarking Alliance Food and Agriculture Benchmark is not a standard setting body but measures and ranks the world's most influential companies on key issues underpinning the food systems transformation agenda.

← 4. On 12 December 2022, the OECD Council adopted the Recommendation on the Role of Government in Promoting Responsible Business Conduct. The Recommendation lays out a set of 21 principles and policy recommendations to assist governments, other public authorities, and relevant stakeholders in their efforts to design and implement policies that enable and promote responsible business conduct. A total of 51 countries have adhered to the Recommendation.