This section outlines the analytical framework used to categorise the different policy measures identified and in scope of the selective inventory (see Annex A), which are compared in more detail in section 3. It also briefly addresses other policy measures and the issue of private, public and multi-stakeholder certifications, labels and other initiatives in the agriculture sector.

Review of G7 Government-led Voluntary and Mandatory Due Diligence Measures for Sustainable Agri-food Supply Chains

2. Analytical framework to categorise due diligence-related policy measures

Copy link to 2. Analytical framework to categorise due diligence-related policy measuresAbstract

2.1. Categorising policy measures in scope of the selective inventory

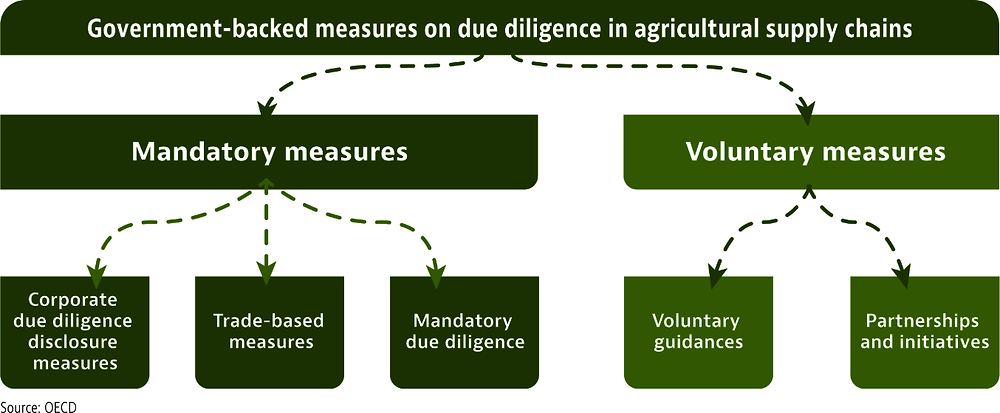

Copy link to 2.1. Categorising policy measures in scope of the selective inventoryThe selective inventory focuses on the following categories of mandatory and voluntary policy measures to address RBC risks in agriculture supply chains (see Figure 2.1).1 For the purposes of this paper, we define these as follows:

1. Mandatory measures:

Corporate due diligence disclosure measures: require public disclosure of information on what companies are doing to identify and address environmental and social risks in their operations and supply chains.

Trade-based measures: prohibit the import, placing on the market, export and/or use of products or commodities associated with adverse social and environmental impacts, subject to demonstration of adequate due diligence or due care.

Mandatory due diligence measures: require companies to carry out due diligence in relation to specified adverse impacts associated with their operations, suppliers and other business relationships, without introducing prohibitions on the import, export or use of specific products.

2. Voluntary measures:

Government guidance: set out guidance to promote more sustainable and responsible business practices in global agriculture supply chains.

Government-led partnerships and initiatives, which aim to promote more responsible business practices, including due diligence, and engage with suppliers and smallholder farmers, often through multi-stakeholder dialogue and exchange.

Figure 2.1. Typology of voluntary and mandatory measures identified

Copy link to Figure 2.1. Typology of voluntary and mandatory measures identified

The scope of this review excludes the following: policy measures relating to public procurement, trade and investment policy or sustainable finance and private-sector initiatives, certifications and labelling schemes. In addition, some of the included measures are not specific to the agriculture sector/supply chains and have a more horizontal approaches covering all sectors of the economy without distinctions.

2.1.1. Corporate due diligence disclosure measures

Copy link to 2.1.1. Corporate due diligence disclosure measuresCorporate due diligence disclosure or reporting measures require companies to disclose certain types of risks and impacts they identify and whether they are taking or have taken any action to address them. They expect companies to meet certain standards when disclosing information and, in some cases, require reported information to be audited. However, companies are not held to account for the quality of their due diligence.

2.1.2. Trade-based measures

Copy link to 2.1.2. Trade-based measuresTrade-based measures in the context of this paper are understood as actions that prevent or ban companies and/or natural persons from importing, exporting and/or using commodities or products whose production is associated with specific adverse human rights and/or environmental impacts.

Flexible trade-based instruments allow both specific and general bans to be introduced at the discretion of the enforcing authority. They aim at incentivising more responsible corporate conduct and promoting consumption and trade of sustainable products by reducing the market share, for example of importers or exporters that are allegedly causing or connected to harms via their supply chain. They also seek to reorient importers and consumers towards suppliers with higher labour and environmental standards.

For the trade-based measures identified (below), the onus is generally on the importing or exporting company or regulated person to prove that the relevant product or commodity is not associated with specific environmental or social harms, either through establishing and implementing adequate due diligence systems or that it meets a certain risk level (e.g., “negligible” risk of deforestation).

|

US Lacey Act (amended in 2008) |

|

Japan’s Act on Promotion of Use and Distribution of Legally Harvested and Wood Products (hereafter Clean Wood Act) (2016) |

|

UK Environment Act (2021) |

|

EU Deforestation Regulation (2023) (replacing the EU Timber Regulation) |

2.1.3. Mandatory due diligence measures

Copy link to 2.1.3. Mandatory due diligence measuresMore recently, some G7 governments have opted to introduce mandatory due diligence legislation requiring companies to undertake due diligence on human rights and environmental risks in their operations and supply chains. Mandatory due diligence requires companies to adhere to specific standards of conduct when identifying, responding to and reporting on adverse human rights and environmental impacts connected to their operations, suppliers and other business relationships.

The two mandatory due diligence measures in scope of this study are cross-sectoral measures i.e., they apply across sectors and to a wide range of RBC risks and impacts, although their individual scope differs.

|

French loi sur le devoir de vigilance des sociétés mères et des entreprises donneuses d’ordre (here after Duty of Vigilance) (2017) |

|

‘Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz’ or ‘LkSG (hereafter the German Supply Chain Act) (2023) |

2.1.4. Government guidances

Copy link to 2.1.4. Government guidancesA number of G7 countries are also opting to develop voluntary guidances, guidelines or codes of conduct to promote more sustainable business practices and supply chains and set out expectations for companies. These often provide detailed recommendations as to how companies are expected to conduct due diligence. They do not have any enforcement or monitoring mechanism.

2.1.5. Government-led partnerships and initiatives

Copy link to 2.1.5. Government-led partnerships and initiativesGiven the cross-jurisdictional nature of agricultural supply chains and the global scale of environmental and social challenges, G7 countries have set up multiple partnerships and initiatives to promote sustainable agricultural supply chains and enhance the collaboration of the supply chains actors in both exporting and importing countries. They can further provide training, capacity-building and awareness raising materials to ensure better uptake of due diligence. However, the partnerships and initiatives in scope of this study do not mandate or hold companies to account for a specific standard of conduct.

|

US Forest Data Partnership (2021) |

|

German Initiative for Sustainable Agricultural Supply Chains (2021) |

|

Canada Sustainable agri-food value chains (part of the Food Systems Summit) (2021) |

|

FACT Dialogue (2021) |

2.2. Other policy areas and the role of private, public and multi-stakeholder sustainability initiatives

Copy link to 2.2. Other policy areas and the role of private, public and multi-stakeholder sustainability initiatives2.2.1. Other policy areas to incentivise due diligence

Copy link to 2.2.1. Other policy areas to incentivise due diligenceG7 governments are also increasingly encouraging RBC across relevant policy areas, including in the context of public procurement, trade and investment policy or sustainable finance (OECD, 2022[29]). This is consistent with the OECD Recommendation on the Role of Government in Promoting Responsible Business Conduct, to which all G7 countries and the EU have adhered to.

Public procurement: G7 countries and EU countries spend on average 14% of GDP on public procurement (OECD, 2021[30]). This makes public procurement a potentially powerful tool for achieving social, environmental or other policy objectives and driving more responsible business practices, including in agricultural supply chains (OECD, 2021[31]) (OECD, 2020[32]). Many G7 countries and the EU promote the integration of RBC objectives in public procurement in policy and practice for example by adapting tender specifications and contract clauses. Results from an OECD survey highlighted that 80% of Central Purchasing Bodies (CPBs) have risk management systems that take into account RBC objectives. These risk management systems are most developed for environmental considerations and integrity risks (OECD, 2021[31]).

Trade and investments: Trade and investment policies and agreements are also increasingly used as a lever to encourage RBC (see Box 2.1). A number of G7 countries and the EU include chapters on Trade and Sustainable Development in their trade agreements, which generally include several sustainability provisions and RBC clauses with express references to internationally recognised standards and principles on RBC. To date, twenty-one free trade agreements between G7 countries and third countries include direct reference to internationally recognised OECD standards on RBC, including the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct (MNE Guidelines) (ILO, 2023[33]). Bilateral Investment Treaties and Trade preference schemes for developing countries, such as the UK Developing Countries Trading Scheme (DCTS), can include elements of RBC within their terms, such as the power to suspend preferences for serious and systematic violations of human rights and labour rights based on international conventions.

Box 2.1. US Executive Order 14072 on Strengthening the Nation’s Forests, Communities, and Local Economies

Copy link to Box 2.1. US Executive Order 14072 on Strengthening the Nation’s Forests, Communities, and Local EconomiesOn 22 April 2022, the US released an Executive Order to, among other objectives, explore actions to address international deforestation. The Executive Order calls for an evaluation of policy options that could be deployed to tackle national and international deforestation risks, including those linked to “international programming, assistance, finance, investment, trade, and trade promotion” by federal agencies. These measures could include:

(i) Incorporating the assessment of risk of deforestation and other land conversion into guidance on foreign assistance and investment programming related to infrastructure development, agriculture, settlements, land use planning or zoning, and energy siting and generation.

(ii) Addressing deforestation and land conversion risk in new relevant trade agreements and seek to address such risks, where possible, in the implementation of existing trade agreements.

(iii) Identifying and engaging in international processes, as appropriate, to pursue approaches to combat deforestation and enhance sustainable land use opportunities in preparing climate, development, and finance strategies.

(iv) Engaging other major commodity-importing and commodity-producing countries to advance common interests in addressing commodity-driven deforestation; and

(v) Assessing options to direct foreign assistance and other agency programs and tools, as appropriate, to help threatened forest communities transition to an economically sustainable future, with special attention to the participation of and the critical role played by indigenous peoples and local communities and landholders in protecting and restoring forests and in reducing deforestation and forest degradation.

Source: Federal Register / Vol. 87, No. 81 / Wednesday, April 27, 2022 / Presidential Documents

Sustainable finance: To ensure consistency and integrity over sustainability claims and help direct financial flows towards sustainable activities, a number of G7 countries have enacted laws to align ESG frameworks with key sustainability objectives and avoid greenwashing. These include taxonomies that provide classification systems under which economic activities can be considered environmentally sustainable. The EU Taxonomy Regulation for example includes the forestry sector to help investors provide financing for afforestation, conservation forestry, forest management and forest restoration. The EU taxonomy provides a number of screening and technical criteria to assess whether these economic activities are substantially contributing to environmental objectives and further includes a specific “minimum safeguard” criterion, which corresponds to procedures (i.e., due diligence) companies have put in place to aligned with the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct or the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (EU Platform on Sustainable Finance, 2022[34]). Investment product labelling is another tool to steer financial flows toward more sustainable activities. For example, the EU’s Sustainable Finance Disclosures Regulation and the UK Financial Conduct Authority’s Sustainability Disclosure Reporting labels for investment products, which may require investor / asset manager due diligence on portfolio companies.

2.2.2. Certifications, labelling and other private and public sustainability initiatives

Copy link to 2.2.2. Certifications, labelling and other private and public sustainability initiativesThe selective inventory in Annex A excludes public, private and multi-stakeholder certifications, labelling schemes and other types of sustainability initiatives (often referred to as “voluntary sustainability standards”) from its scope. These are also excluded from the comparative analysis in section 4.

However, it is important to acknowledge that certifications and labelling in particular are widely used in the agricultural sector by governments, industry and civil society to promote more sustainable and responsible business practices. Box 2.2 therefore briefly discusses the current landscape and discusses their use in the identified policy measures.

Box 2.2. Certifications and other sustainability initiatives

Copy link to Box 2.2. Certifications and other sustainability initiativesThe last decade has seen a proliferation of public and private certifications, labels, international framework agreements and other types of sustainability initiatives, including in the agriculture sector. Many of these are product-based, requiring products to meet specific social and/or environmental sustainability criteria and/or aimed at demonstrating conformity with good agricultural practices (UNCTAD, 2020[35]). Others aim to monitor, certify or assess the due diligence of participating companies or their suppliers.

Certifications and other types of sustainability initiatives vary significantly in their geographical reach, risk and commodity scope and supply chain coverage. They also differ in their core aims and activities—as well as in their assessment and assurance models, governance and oversight systems, levels of transparency and overall credibility. Understandings of OECD RBC due diligence standards and core risk-based due diligence principles also vary considerably (OECD, 2022[36]).

Given the variety of approaches, the extent to which a particular certification or other type of initiative can support due diligence implementation will depend on the specific context. A well-designed certification scheme, for example, may provide useful information on good agricultural practices, conditions of production and harvesting or forest management at a specific point in time. However, companies retain ultimate responsibility for their own due diligence and for how they check, use and build on the information they receive from third party schemes. Many certification schemes do not fully integrate a due diligence approach, but rather provide specific information—such as supplier, product or site information or supply chain traceability information—that can feed into and inform downstream companies’ broader due diligence.

Differences between sustainability initiatives can create challenges for companies, particularly those who participate in multiple initiatives across different risks and geographies as part of their due diligence. It can also create uncertainty about what particular certifications or product labels mean (OECD, 2022[36]). The OECD is working to promote greater coherence in how industry, government-led and multi-stakeholder initiatives integrate due diligence through its ongoing Alignment Assessments against OECD RBC Due Diligence Guidance in the agriculture, minerals and garment and footwear sectors, and harmonised alignment and credibility criteria for initiatives across sectors.1

1. The OECD MNE Guidelines state that initiatives should be “credible and transparent”, and the OECD is developing harmonised alignment and credibility criteria for initiatives across different sectors following a mandate set out in the recent RBC Ministerial Declaration (OECD, 2023[37]). For more information on OECD Alignment Assessments, see: OECD Alignment Assessments of Industry and Multi-Stakeholder Programmes - OECD. The OECD is also developing interactive online “Due Diligence Checker” tools as a self-check for individual companies and initiatives, see for example: OECD Due Diligence Checker (sustainabilitygateway.org). An equivalent tool for the agriculture sector is in progress.

Some of the G7 policy measures listed in this review reference certification schemes or other third party verified schemes as a means to help companies comply with due diligence-related expectations, although they often lack specificity about the role of those schemes in the context of a company’s own due diligence and whether companies have a responsibility to check the credibility of the certifications they use.

Table 2.1. Examples of how certification or other third party verified schemes are referenced in identified policy measures

Copy link to Table 2.1. Examples of how certification or other third party verified schemes are referenced in identified policy measures|

Measures |

Certification schemes referenced |

|---|---|

|

Japan Clean Wood Act |

The Clean Wood Navi, the Forestry Agency’s web portal, cites other sources of information about illegal logging, including forest certification information such as Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC), Fairwood, a Japanese NGO network, and other certification schemes. The site also lists further studies commissioned to support meaningful compliance. |

|

EU Deforestation Regulation |

Article 10 (Risk assessment) – the risk assessment shall take into account a range of criteria, including “complementary information on compliance with this Regulation, which may include information supplied by certification or other third-party verified schemes, including voluntary schemes recognised by the Commission under Article 30(5) of Directive (EU) 2018/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council 1, provided that the information meets the requirements set out in Article 9 of this Regulation.” |

|

EU Code of Conduct on Responsible Food Business and Marketing Practices |

Under aspirational objective 7 (Sustainable sourcing in food supply chains), the indicative action has been identified to “Encourage the uptake of scientifically robust sustainability certification schemes for food (incl. fish and fishery products” in order to transform commodity supply chains (3.1.3). |

|

Japan introductory Guide on Environmental Due Diligence along the Value Chains |

The guide introduces several examples of certifications and other initiatives in the main chapters as well as on pp.46-51: 5.3 List of references (e.g., ISO26000, ISO 20400, Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil [RSPO], Marine Stewardship Council [MSC], Aquaculture Stewardship Council [ASC], Forest Stewardship Council [FSC], Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification Scheme [PEFC], Sustainable Green Ecosystem Council [PEFC], and several other Japan-specific initiatives). |

Source: OECD

Note

Copy link to Note← 1. Some measures may fall under more than one category, for example some partnerships and initiatives may develop voluntary guidance for business and a trade-based measure may require demonstration of adequate due diligence or due care.