Alexandre Georgieff

Alexander Hijzen

Alexandre Georgieff

Alexander Hijzen

In Spain, productivity growth has been persistently weak in recent decades. This reflects lower multi-factor productivity growth due to difficulties in adapting to technological change and globalisation, lower capital deepening due to the persistent decline in investment following the global financial crisis and growing disparities in productivity due to weak productivity growth in lagging firms and regions. Reviving productivity growth requires amongst others investing in worker skills, promoting the adoption of new technologies in lagging firms while enhancing the reallocation of resources from less to more productive firms and tackling large and widening disparities in productivity between regions.

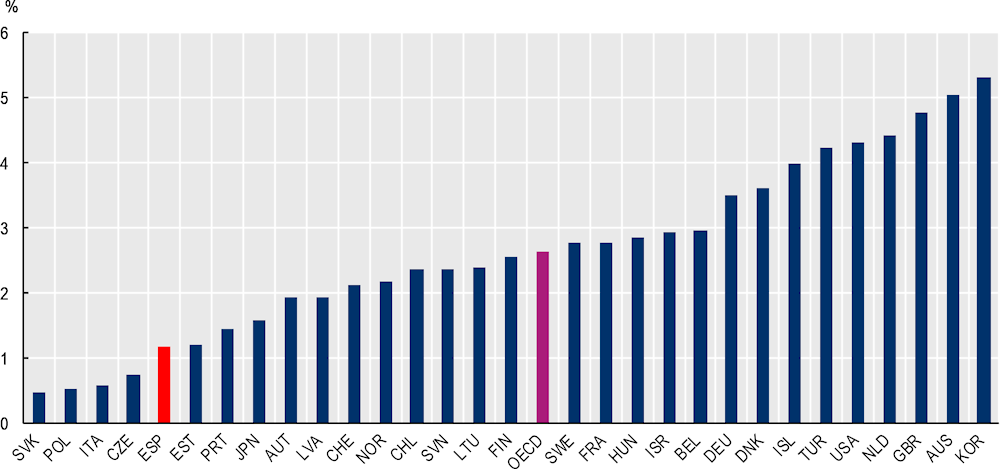

Productivity growth has almost come to a halt in Spain, with important implications for real wage growth and the standard of living. During the decade from 2011‑21, productivity growth averaged just 0.5% per year, less than half that of the OECD average. The primary objective of this chapter is to set the scene by providing an overview of the main factors that drive the slowdown in productivity. It also provides a first discussion of the main policy avenues for reviving productivity growth by i) investing in worker skills, ii) promoting technology diffusion and job reallocation between firms and iii) tackling regional disparities in productivity performance. Chapter 3 will provide a detailed overview of the specific role of labour market policies in reviving productivity growth in Spain, with an emphasis on wage‑setting institutions and job-security provisions, since these were at the heart of the 2021 labour market reform.

Labour productivity in Spain has been growing slowly over the past three decades, resulting in a considerable decline in productivity performance compared to other OECD countries. While a productivity slowdown was observed in many other OECD countries, it began earlier in Spain and has been particularly marked. This has put downward pressure on wage growth and living standards and was exacerbated by the declining share of productivity gains that was passed on to workers, particularly those in the middle and bottom of the wage distribution. Slower multifactor productivity (MFP) growth was the main factor behind the low productivity growth in Spain until the global financial crisis (GFC). Since then, lower capital deepening has accounted for about one‑third of the productivity slowdown.

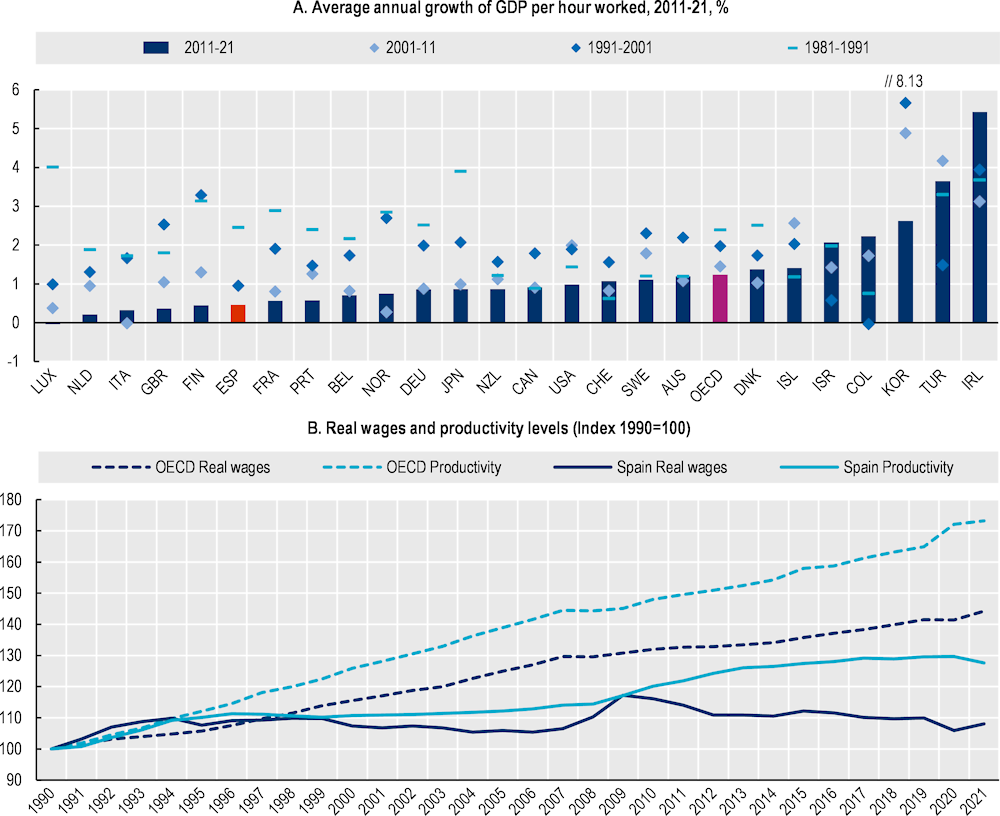

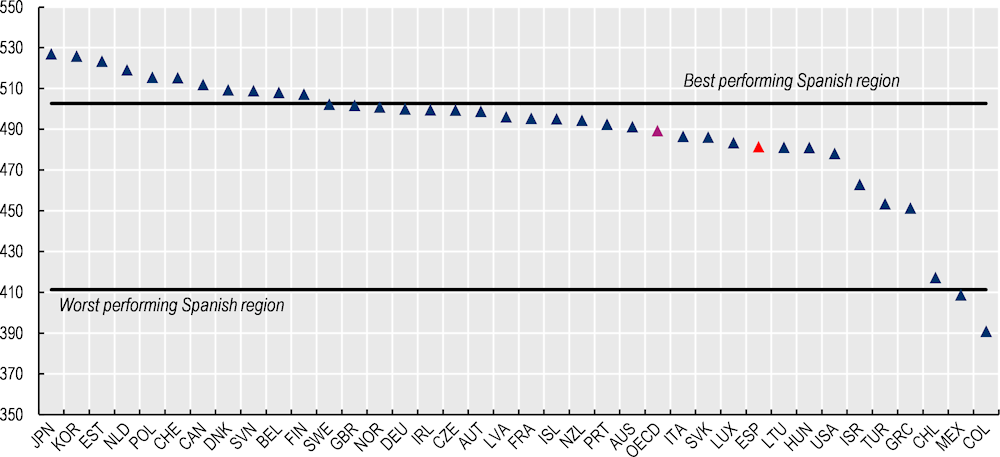

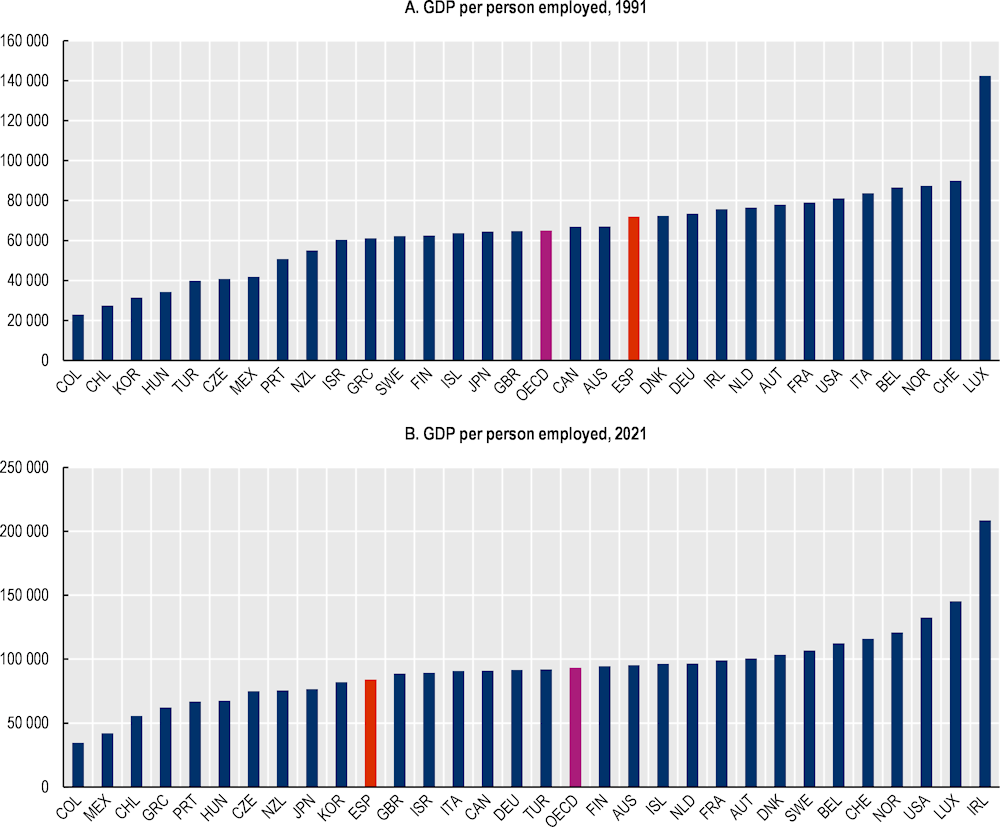

Labour productivity growth, measured in terms of real gross domestic product (GDP) per unit of labour, has been particularly weak over the past three decades in Spain (see Box 2.1 for details on the measurement of labour productivity). Over the period 2011‑21, it grew by an average of 0.5% per year, one of the lowest rates among OECD countries and less than half of the OECD average (Figure 2.1 Panel A). The productivity slowdown in Spain began in the 1990s, well ahead of most other OECD countries, and has been particularly pronounced (Figure 2.1, Panel B). Productivity growth in Spain fell from 2.5% in the 1980s to less than 1% in the 1990s and 2000s and just 0.5% in the 2010s. For the OECD as a whole, the slowdown was less strong. Productivity growth declined from 2.5% in the 1980s to 2% in the 1990s, 1.5% in the 2000s and 1.2% in the 2010s. As a result, Spain’s labour productivity performance has deteriorated considerably in recent decades, both in absolute terms and relative to other OECD countries, from above‑average in 1991 to below-average in 2021 (Figure 2.2).1

Low productivity growth puts downward pressure on wage growth and the rise in living standards. Real wage increases are one of the main channels through which productivity gains are passed onto workers, along with better working conditions and enhanced employment opportunities (OECD, 2018[1]). It is therefore not surprising that real wage growth has been low in Spain compared with other OECD countries over the last couple of decades (OECD, 2021[2]). However, average real wage growth was considerably lower still than productivity growth, resulting in a decline in the labour share. Indeed, real wage growth was close to zero between 1995, at the time when productivity growth stalled, and 2021. Declining labour shares and weak real wage growth have been observed in many other OECD countries, suggesting that this is in part the result of common structural developments, such as globalisation and technological change that have eroded the bargaining power of workers.

In addition, limited productivity gains have not been broadly shared. Wage growth at the bottom and at the middle of the wage distribution has not kept pace with average wage growth, resulting in rising wage inequality and negative real wage growth for some groups of workers. For example, the real wage of young Spaniards has tended to decline over the last couple of decades (OECD, 2023[3]). The increase in wage inequality is similar to the pattern observed in many other OECD countries and is consistent with the secular increase in the relative demand for skilled workers, as a result of the integration of low-wage countries in the world economy (e.g. China) and skill-biased technological change.

Note: Panel A: Data are measured in constant prices USD 2015 purchasing power parities. OECD is the unweighted average among the countries analysed. Panel B: Productivity is GDP per hour worked. Wage are average annual wages per full-time and full-year equivalent employee in the total economy. OECD unweighted average for Australia, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States.

Source: OECD Productivity Statistics Database.

Note: Data are measured in constant prices 2015 USD purchasing power parities. OECD is the unweighted average among the countries analysed.

Source: OECD Productivity Statistics Database.

Labour productivity measures the total volume of output produced, in terms of the real gross domestic product (GDP) per unit of labour. Total hours worked is generally the preferred measure of labour input, as it accounts for differences in total working hours per person across countries. In practice, the number of persons employed is often used as a proxy for labour input, as data on total hours worked are not always available or readily comparable across countries (OECD, 2018[4]).

Cross-country comparisons of hourly labour productivity need to be considered carefully. One particular issue is that information on total hours workers and information on production is gathered from different sources, which may result in slight differences in the range of economic activities covered. As a result, productivity estimates that rely on information on total hours workers from labour force surveys without correcting for differences in coverage tend to be biased downwards. The hourly labour productivity figures presented in this chapter use the adjustment procedure proposed by Ward, Zinni and Marianna (2018[5]).

Some analysts have pointed to the possibility that productivity growth might be underestimated due to the difficulty of fully accounting for the growing importance of the digital economy (the “mismeasurement hypothesis”). For example, intangible assets (e.g. brand recognition, intellectual property, software and computerised information) may not be fully captured, which can lead to underestimating output growth, and therefore productivity growth (Brynjolfsson, Rock and Syverson, 2021[6]). Most researchers, however, concur that these potential mismeasurements – while deserving more attention – are not sufficient to explain the productivity slowdown (Ahmad, Ribarsky and Reinsdorf, 2017[7]).

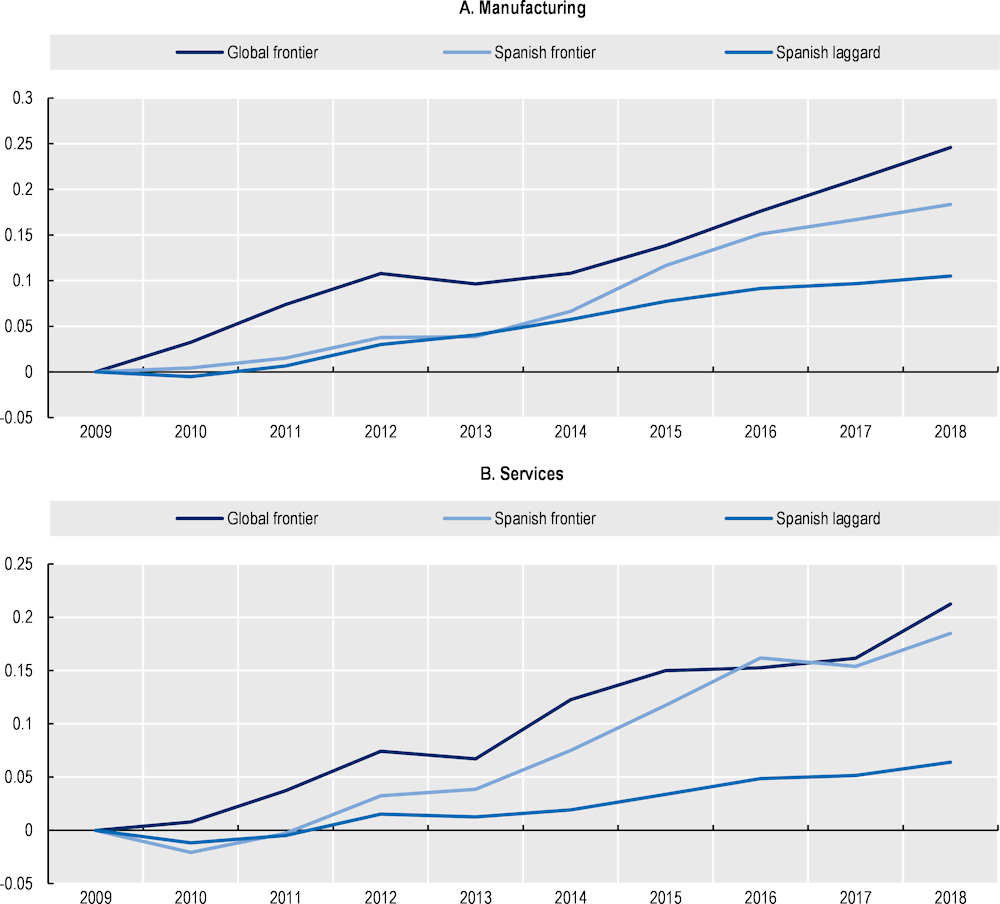

In Spain, as in many other OECD countries, the slowdown in labour productivity growth reflects to an important extent slow growth among low productivity firms, while growth in high productivity firms has remained robust (Figure 2.3). The top 5% of most productive firms in Spain, so-called frontier firms, exhibit healthy labour productivity growth (about 2% per year on average), comparable to that of their counterparts in other OECD countries. Labour productivity growth among other less productive firms, so-called lagging firms, however, has fallen considerably behind, particularly in services (1% per year in manufacturing, 0.5% in services). As a result, disparities in productivity between firms have been widening.

The slowdown in productivity growth among lagging firms is likely to reflect a combination of factors. It could reflect the growing difficulty for lagging firms to move from an economy based on production to one based on ideas. As technologies become more complex and their use increasingly hinges on the availability of human and organisational capital, this may have slowed the diffusion of new technologies from frontier to lagging firms (Berlingieri et al., 2020[8]; Gal et al., 2019[9]). But it could also reflect rising entry barriers and a decline in the contestability of markets. This is supported by evidence that suggests that the divergence in productivity growth is more pronounced in more strictly regulated product markets (Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal, 2016[10]).

Log value added per person employed (2009 = 100)

Note: Average across detailed manufacturing and services industries using firm-level data. 3-year moving average. Labour productivity is defined as value added per employee. Productivity frontier is defined as the average of the productivity for the top 5% firms in the productivity distribution.

Source: Preliminary calculations following the methodology in Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal (2016[10]) using the 2021 vintage of the Orbis firm-level financial accounts database by Moody’s/BvD, with acknowledgments to Natia Mosiashvili for carrying out the calculations.

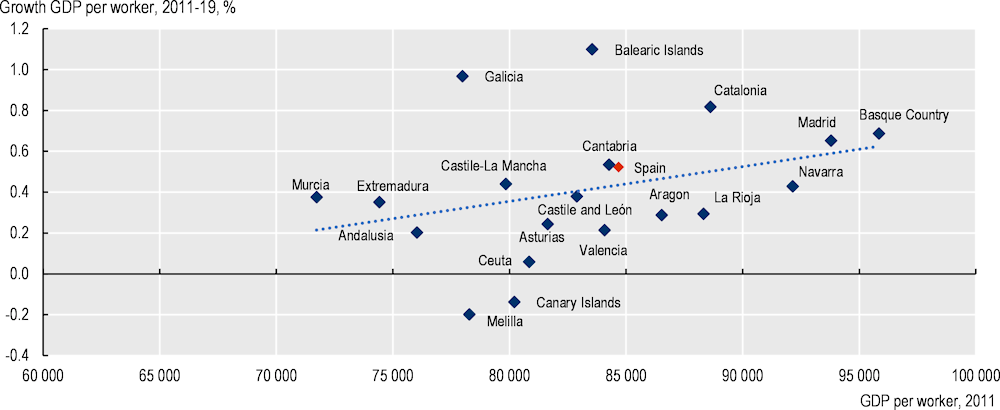

Disparities in productivity growth across Spanish regions (autonomous communities) are significant and have tended to widen (Figure 2.4). Over the period 2000‑19, average annual productivity growth was the strongest in the Balearic Islands and Galicia, about twice the nation-wide growth rate. In contrast, productivity declined somewhat in the Canary Islands and Melilla. There is no indication that lagging regions are catching up with higher productivity ones. On the contrary, productivity growth tends to be lower in regions with low levels of productivity, so that regional disparities are widening.2 For example, the Canary Islands exhibit both low levels of productivity and strong declines in productivity, while regions in the North-East tend to exhibit high productivity levels and high growth.

Note: GDP per worker is measured in constant prices, with 2015 as the base year. Region is the autonomous community of work (not residence).

Source: OECD Regional Statistics Database.

In theory, labour productivity growth can be promoted either by increasing the amount of capital per hour worked, i.e. capital deepening, or by improving the efficiency with which labour and capital are used in the production process, i.e. multifactor productivity (MFP). Aggregate MFP is primarily intended to reflect the efficiency of the production process (management practices, economies of scale and scope) and the efficiency of the allocation of resources across firms (including through firm entry and exit). However, since labour quality is not taken into account in the estimation of MFP, it may also capture the role of worker skills in practice.

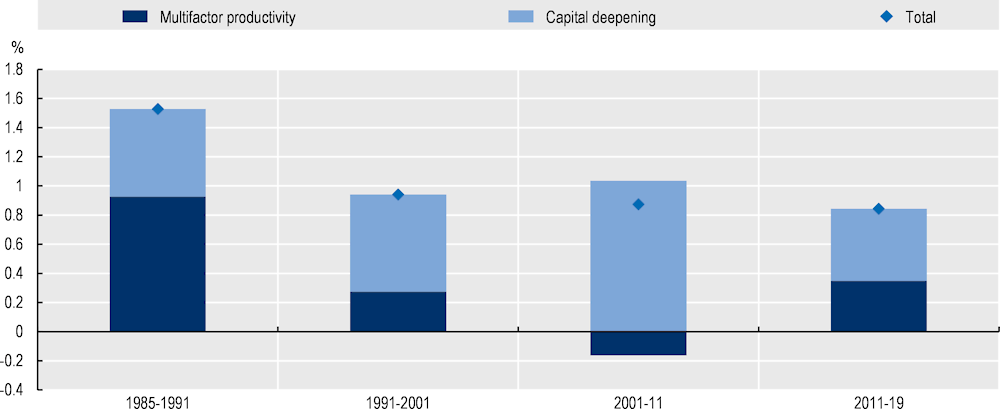

The slowdown in labour productivity growth since the 1990s in Spain was largely driven by slower MFP growth. MFP growth fell from about 1% in the late 1980s to about 0.25% in the 1990s and even turned slightly negative to ‑0.2% in the 2000s. (Figure 2.5). During the 1990s and 2000s, labour productivity growth remained broadly constant as lower MFP growth was offset by increased capital deepening. Since the early 2010s, labour productivity growth remained low as capital deepening slowed following the global financial crisis despite the return to positive, although still weak, MFP growth.

Average annual growth in Spain, percentage

Note: Data are measured in constant prices.

Source: OECD estimates based on OECD Productivity Statistics Database.

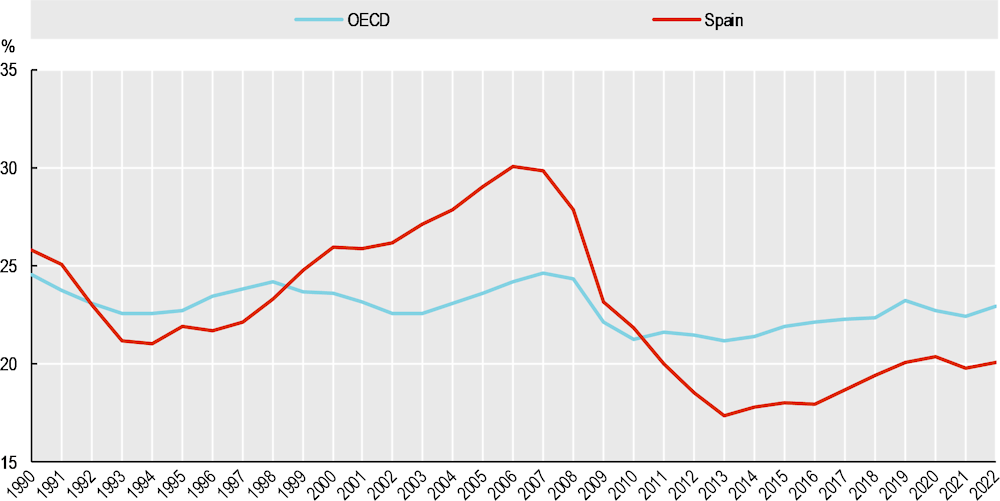

The reduction in capital deepening can be attributed to a significant and persistent decline in investment following the global financial crisis. Spain was highly susceptible to the crisis due to the presence of a housing and real estate bubble, as well as the banking sector’s exposure to the housing sector. Before the global financial crisis, investment as a share of GDP was well above that of the OECD average, partly fuelled by the boom in construction (Figure 2.6). When the global financial crisis hit, investment declined sharply across the OECD, but particularly in Spain, bringing investment down to a level well below the OECD average. The recovery in investment has been weak and incomplete across the OECD, including Spain. Investment in Spain remains below its level at the onset of the global financial crisis as well as its historical average.

In contrast to the global financial crisis, most firms were able to preserve their investment capacity during the COVID‑19 crisis. This reflected in part the fact that the financial system remained in good health during the COVID‑19 crisis and in part the exceptional financial-support measures that were adopted by governments in response to the crisis (e.g. bank loan guarantees, deferrals of taxes and social-security contributions, and wage bill subsidies including through job retention schemes (OECD, 2020[11]). As the situation evolved, crisis-support measures were increasingly replaced by recovery measures under the National Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan (RTRP) and the EUs Next Generation programme (OECD, 2023[3]). These often take the form of public investment through public-private partnerships in strategic sectors where private investment is deemed insufficient.

Going forward, there is considerable uncertainty about the investment outlook given the tightening of monetary policy in the context of still high inflation and geopolitical instability as a result of Russia’s war of aggression in Ukraine (OECD, 2023[12]). While investment in Spain has held up well since the COVID‑19 crisis up until 2022, thanks in part to the role of crisis-support and recovery packages put in place by governments, it remains well below the average level in the OECD or nearby countries such as France and Italy. According to the government, the RTRP and associated reforms will boost GDP by about 3 percentage point in 2023 and 2024 (Ministerio de Asuntos Económicos y Transformación Digital, 2023[13]).

Gross fixed capital formation, total economy, percentage of GDP

Source: OECD Annual National Accounts database.

The slowdown in MFP growth is largely structural in nature and reflects a combination of long-standing challenges:

The difficulty of workers to adapt to changing work practices and the use of new technologies, including those requiring digital skills.

The difficulty of firms to innovate, adopt new technology and introduce more efficient management and working practices.

Large and growing disparities in productivity between regions.

Each of these challenges is likely to be affected by the transformative processes that were triggered or reinforced by the COVID‑19 crisis. The pandemic accelerated the use of digital technologies in the workplace (e.g. video conferencing, cloud computing, and team-working tools) and the adoption of remote working practices. This shift allowed for greater flexibility and reduced commuting time, leading to improved productivity. The pandemic also expedited the adoption of automation and generative artificial intelligence (AI). The automation of routine tasks and increasingly also non-routine tasks enable employees to focus on more complex and value‑added activities, increasing their productivity.

While these developments are likely to support stronger productivity growth, there is considerable uncertainty about the size of these effects and the extent to which the new opportunities provided by digitalisation, automation and generative AI can be effectively seized upon without first addressing the deeper structural challenges that have held back productivity growth during the past three decades. This further highlights the importance of addressing long-standing structural challenges for reviving productivity growth.

Weak productivity growth in Spain reflects a combination of long-standing structural challenges, mostly specific to Spain, and more recent challenges related to the broader global economic context. This section, however, will mainly focus on the deeper structural factors that were already holding back productivity growth in Spain before the global financial crisis. These are: i) the scarcity of skills needed to fully exploit the potential of new technologies, ii) structural barriers to productivity gains and innovation for firms, and iii) large and growing disparities in productivity between regions. This section describes these challenges and discusses a number of policy measures that could help address them. The specific role of labour market policies will be discussed separately in Chapter 3.

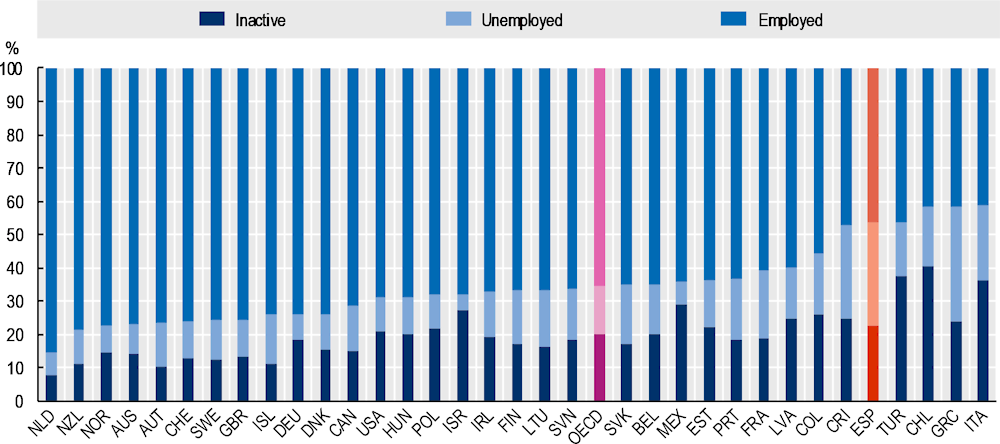

In Spain, a significant skills mismatch between the skills provided by workers and those required by employers hamper productivity growth. Compared with other OECD countries, skill shortages are particularly marked in a number of areas important for innovation and the use of technology, such as engineering, computers and electronics, and may have contributed to underskilling, i.e. the share of workers reporting that they lack some of the qualifications required to perform their job (OECD, 2021[14]). These shortages have become more pronounced in recent years, as the demand for labour rose sharply during the economic recovery from the COVID‑19 crisis (Salvatori, 2022[15]). At the same time, new labour market entrants continue to have difficulty finding a job despite progress in recent years (Figure 2.7). In 2021, among young Spaniards aged 18‑24 who are not in education or training, more than half are unemployed or inactive, compared with about a third for the OECD average. This may reflect having low qualifications in general, but also and perhaps more importantly, not having the right skills for the jobs that are available. The latter may contribute to overskilling, i.e. the share over workers reporting that they have higher qualifications than required for their job. Addressing skills imbalances requires i) preventing early school leaving; ii) building stronger linkages between the worlds of work and education; and iii) promoting adult education and training.

Labour market status of youth aged 18‑24 not in education or training, 2021, percentage

Note: OECD unweighted average.

Source: OECD (2024), “Education at a glance: Transition from school to work”, OECD Education Statistics (database), https://doi.org/10.1787/58d44170‑en.

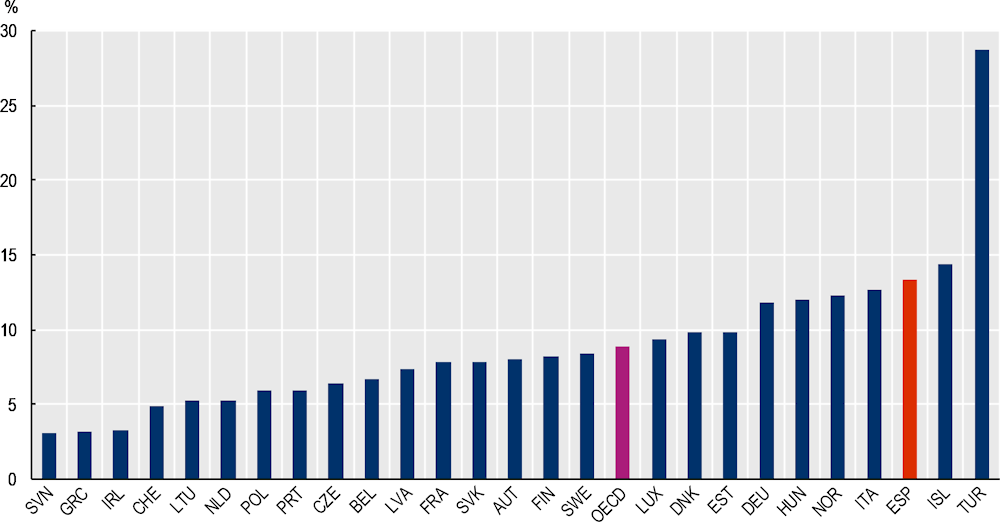

Many early school leavers are not well equipped to take advantage of new technologies. Spain continues to have one of the highest early school leaving rates in the OECD despite significant progress in recent years: in 2021, 13% of the 18‑24 year‑olds leave school without having gone beyond lower secondary education, almost half the level a decade earlier, but still considerably higher than the OECD average of 9% (Figure 2.8). Early school leaving is particularly an issue for boys and young persons from poor households. Early school leaving significantly reduces the chances of making a smooth transition from school to work. It is associated with a higher risk of unemployment, and fewer job opportunities based on the use of new technologies. In particular, many early school leavers will remain poorly educated later in life (OECD, 2023[3]). Moreover, low skills are more likely to become obsolete as automation progresses, while high skills can make work more productive by complementing new technologies (Autor, Levy and Murnane, 2003[16]; Nedelkoska and Quintini, 2018[17]; Georgieff and Hyee, 2021[18]).

Early school leavers, share of 18‑24 year‑olds, 2021 or latest, percentage

Note: OECD is the unweighted average among the countries analysed.

Source: OECD (2023[3]), OECD Economic Surveys: Spain 2023.

Early childhood education and care (ECEC) can influence learning dispositions later in life and is particularly important for children from disadvantaged backgrounds (OECD, 2006[19]). Expanding access to early childhood education has been a government priority since 2021. Participation in early childhood education is now above the OECD average. However, access to early childhood education for poor families remains a challenge (OECD, 2023[3]). Early warning indicators and tailored support for students at risk of dropping out via specific programmes could lower early school leaving further. Spain’s Territorial Co‑operation Programmes, such as the Educational Guidance, Advancement and Enrichment Programme (PROA+), which provides support to students with educational problems, and the Programme of Accompaniment Units, which provides guidance to students and families from disadvantaged backgrounds, are welcome. For those who have already left school, adult learning programmes can offer a second chance, provided that they are sufficiently comprehensive and offer recognised training. A recent example of Vocational education and training (VET) reform going in the right direction is the 2020 Plan for the Modernisation of Vocational Training. It allows students from upper-secondary vocational education to move on to higher education and provides accreditation for skills acquired outside the formal education system. In 2022/23, about 100.000 students were enrolled in Centres for Adult Teaching geared towards obtaining a degree.

For those who have completed higher education, a significant mismatch between the skills acquired at school and those required by firms may prevent them from making full use of their abilities and hence result in overskilling. Tertiary education in Spain is not well aligned with firms’ needs: only a small share of university graduates are enrolled in Science, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) courses, and the incidence of over-qualification remains relatively high compared to other OECD countries (OECD, 2023[3]).

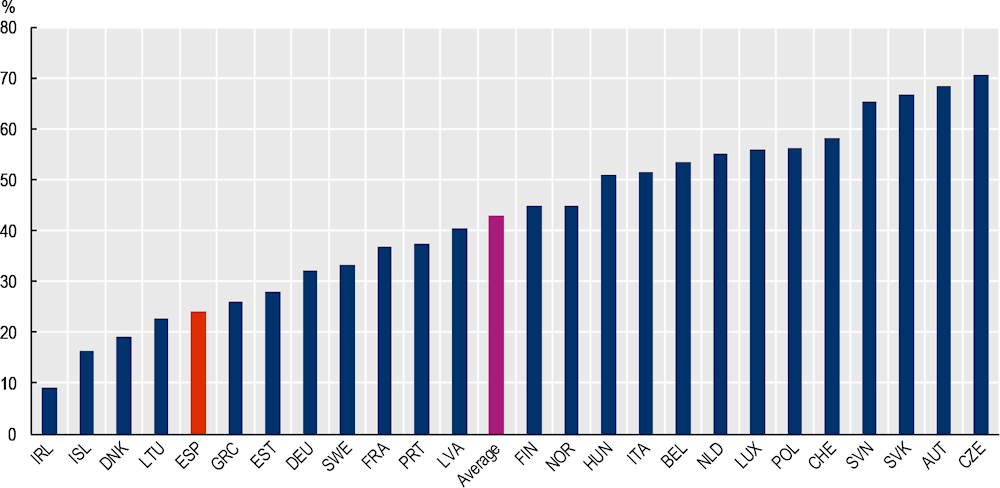

VET could be effective in providing specific technical skills that are lacking (Boto-García and Escalonilla, 2022[20]). However, in 2021, only 24% of Spanish students in upper-secondary education were enrolled in VET, compared to an OECD average of 43% (Figure 2.9). The Organic Law on Vocational Education of March 2022 aims at promoting, modernising and making vocational training more appealing. Moreover, it seeks to make all vocational training dual by combing school-based learning with learning in the workplace. The effectiveness of the reform hinges crucially on its implementation and in particular its ability to induce firms to offer more training places and to attract more students into the system. To increase the number of training places, it is essential to involve small firms (OECD, 2023[3]). This can be achieved by ensuring that vocational programmes cater to the needs of small firms and by reducing the financial and administrative costs of participating. This could take the form of direct financial incentives or the pooling of administrative and educational processes across firms. For example, the Tknika centre in the Basque Country gives firms, especially SMEs, access to specific services and infrastructure (OECD, 2021[14]). The attractiveness of VET programmes for students hinges mainly on their ability to improve career prospects and working conditions, but also on the conditions of the training contract. The new training contract introduced as part of the 2021 Labour Market Reform guarantees minimum wage levels for VET students.3 Moreover, the Organic Law on Vocational Education foresees more attention for career guidance in the education and validation processes.

Involving businesses in the design of vocational and university degrees can also help improve the match between the skills acquired in education and labour market needs (OECD, 2023[3]). In line with this objective, the Organic Law on Vocational Education will involve companies in the process of accrediting skills acquired through professional experience. The Basque University+Business Strategy provides an example of such an initiative at the regional level. It integrates business training, as well as joint education and knowledge‑transfer projects, into university programmes. Regular evaluations of the relevance of study programmes could also help ensure that curricula evolve in line with changing labour market needs. For example, the Catalan quality assurance agency (AQU Catalunya) provides regular information on the relevance of educational programmes for the labour market, taking into account the labour market outcomes of graduates and the views of employers on the skills of recent graduates.

Share of students enrolled in upper secondary vocational education, 15‑19 year‑olds, 2021, percentage

Note: Average is the unweighted average among the countries analysed.

Source: OECD (2023[3]), OECD Economic Surveys: Spain 2023.

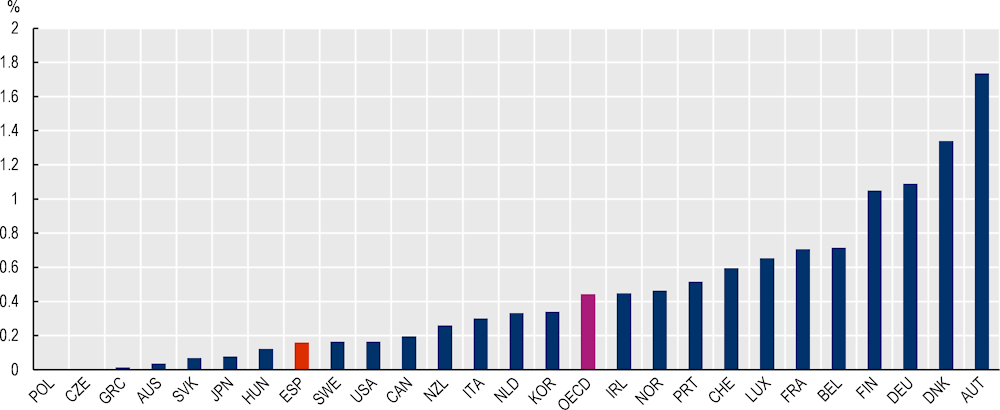

Later in life, adult learning programmes (e.g. reskilling and upskilling) can equip individuals with the skills in demand on the labour market. However, adult training opportunities for the unemployed are limited in Spain: public expenditures on training per unemployed worker only amount to 0.16% of GDP per capita worker, compared with an average of 0.44% in the OECD countries analysed (Figure 2.10).4 There is therefore scope for increasing public spending on adult learning in Spain. If carefully designed, individual learnings accounts can help to assign individuals training rights and reinforce individual choice by tying these rights to the individual rather than to the job (see Box 2.2).

Public expenditures on training, per unemployed, as a share of GDP per capita, 2019

Source: Calculations from OECD data on Labour Market Programmes, National Accounts, OECD Labour Force Statistics.

There has been a renewed interest by policy makers in individual learning accounts as a way of tying training rights to the individual rather than to the job. While in principle individual learning accounts present attractive features (e.g. empowering individual choice), their effectiveness depends critically on their design. In particular, there is a risk that, if badly designed, they may widen participation gaps between over- and underrepresented groups. The features of a well-designed individual learning account include: simplicity; adequate and predictable funding; greater generosity for those most in need; provision of effective information, advice and guidance; a guarantee of access to quality training; and an explicit accounting of the links with employer-provided training.

Three types of individual learning schemes can provide an individual entitlement to training:

Individual Learning Accounts are virtual individual accounts in which training rights are accumulated over time. They are virtual in the sense that resources are only mobilised if training is actually undertaken. The only real example of an Individual Learning Account is the French Compte Personnel de Formation (CPF).

Individual Savings Accounts for Training are real, physical accounts in which individuals accumulate resources over time for the purpose of training. Unused resources remain the property of the individual and, depending on the scheme, may be used for other purposes (e.g. retirement). A few such schemes have been implemented in the past, generally as a pilot scale (e.g. learn$ave in Canada or the Lifelong learning accounts in the United States)

Training vouchers provide individuals with direct subsidies for training purposes, often with co-financing from the individual. They do not allow for any accumulation of rights or resources over time. This is the form of individual learning scheme most frequently implemented. While many individual learning schemes are called “individual learning accounts”, most of these schemes actually function as vouchers.

Source: OECD (2019[21]), “Individual Learning Accounts: Design is key for success”, Policy Brief on the Future of Work, OECD, Paris, www.oecd.org/employment/individual-learningaccounts.pdf

Low productivity growth in Spain mainly reflects low growth among low-productivity firms whereas growth among frontier firms has remained robust. This section therefore mainly focuses on policies to support the diffusion of new technologies to lagging firms and the reallocation of resources from less to more productive firms. It also discusses avenues for ensuring that productivity growth among frontier firms remains robust.

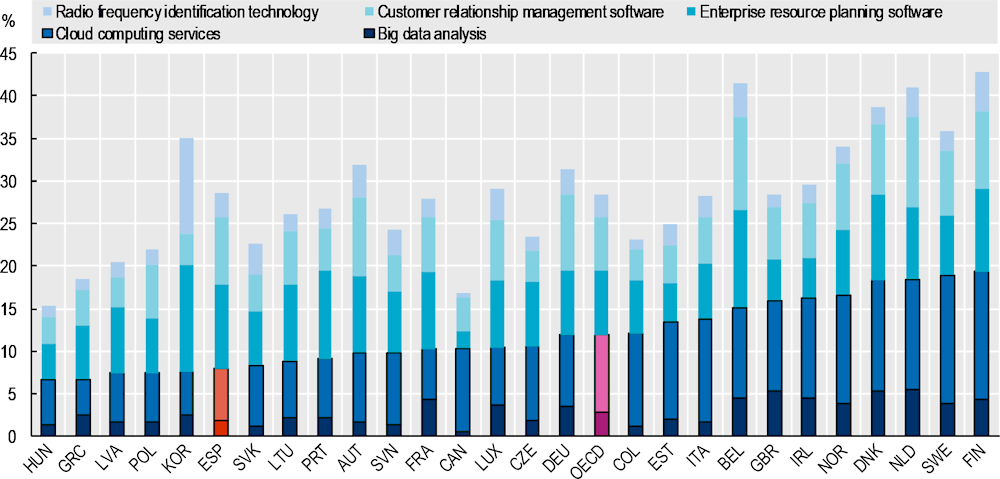

A key challenge for Spain is to promote the diffusion of advanced technologies to lagging firms. Consistent with a slow diffusion of technologies across firms, the adoption rate of advanced digital technologies is among the lowest in the OECD. Adoption rates for Big Data analysis (1.8%) and cloud computing services (6.2%) are one‑third lower than the OECD average (Figure 2.11). This suggests that the adoption of such technologies is largely limited to frontier firms. Spain performs relatively well in the adoption of basic digital technologies (IMF, 2023[22]), including enterprise resource planning and customer relationship management software. A key challenge is therefore to promote the adoption rate of advanced digital technologies across firms.

Direct support measures for lagging firms could help with the adoption of advanced technologies by reducing financial frictions and market distortions (Arregui and Shi, 2023[23]; Berlingieri et al., 2020[8]; Pisu et al., 2021[24]). This could, for example, take the form of better access to finance (e.g. via the development of equity markets), targeted support for intangible investment (e.g. training for managers, software and R&D), or increased non-monetary support (e.g. access to data, less stringent regulation). R&D support has a particular role to play in providing lagging firms with the managerial and organisational capital that is needed for the adoption of advanced digital technologies, including efficient management practices (Berlingieri et al., 2020[8]). By engaging in R&D, lagging firms not only innovate, but also accumulate tacit knowledge that enables managers to understand and assimilate advanced technologies. Grants, loans and credit guarantee schemes are particularly suitable for reducing the cost of R&D and improving access to finance in lagging firms.

The development of digital infrastructure is also key to foster the adoption and diffusion of advanced digital technologies in lagging firms (Pisu et al., 2021[24]). Fiscal incentives can encourage private investment in underserved areas. Direct public investment is essential where private investment is not commercially viable. Regulatory restrictions on the deployment of technology could be reduced, as was done by the 2022 Telecommunications Act, which relaxes public domain use rights and the requirement for public authorities to provide a local urban planning (OECD, 2023[3]).

Adoption rate of digital technologies among firms, 2020 or latest, percentage

Note: The height of the bar gives the average adoption rate across the five technologies. The five components give the contribution of the adoption of each technology to the overall average. Only enterprises with ten or more employees are considered. OECD is the unweighted average among the countries analysed.

Source: OECD ICT Access and Usage by Businesses Database.

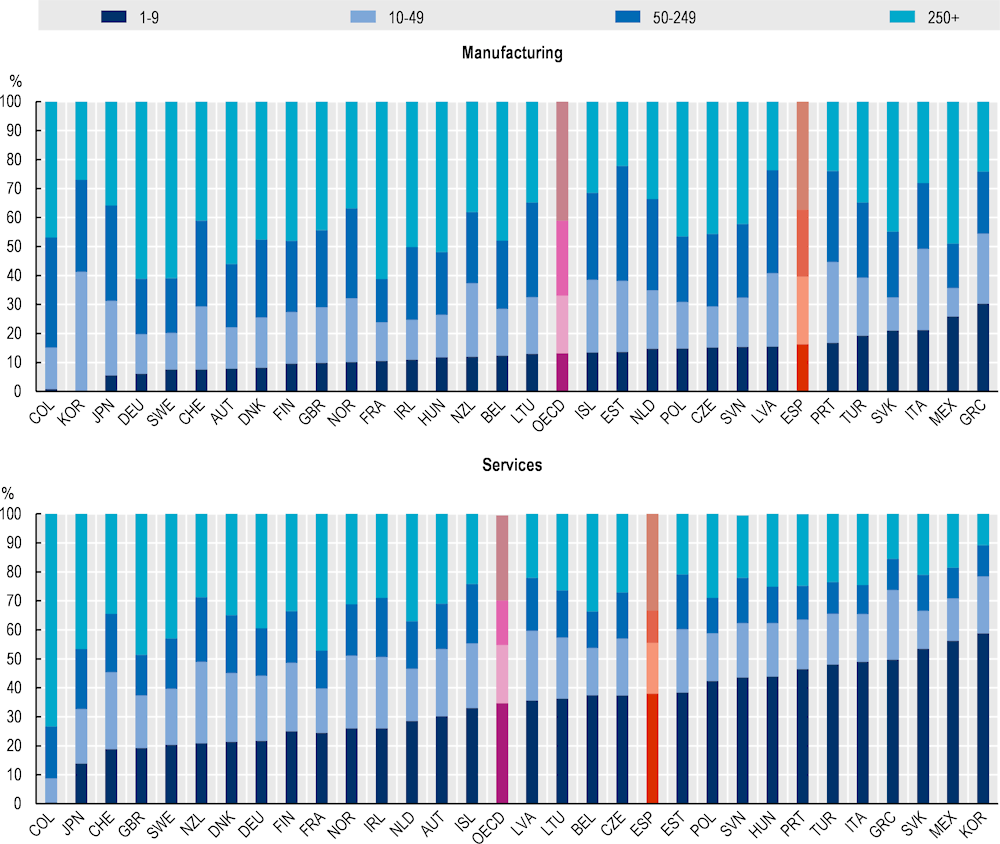

One important factor that is holding back productivity growth among lagging firms and the adoption of advanced digital technologies is the high incidence of small and micro firms in Spain. Firms with less than ten employees account for 16% of employment in manufacturing and 38% in services compared with 13% and 35% on average across the OECD (Figure 2.12). Small firms tend to be less productive (OECD, 2023[25]) and tend to exhibit lower productivity growth than larger firms (Berlingieri et al., 2020[8]). Low productivity growth in small firms is likely to reflect a variety of factors, including access to credit for investment and the capacity to invest in training, adopt new technologies and innovate (Lopez-Garcia and Montero, 2012[26]). There are several factors that could limit the growth of firms, including access to finance, regulatory barriers, and inadequate managerial skills.

Regulatory barriers mainly relate to size‑contingent regulations, differences in regulations between regions and direct support measures targeted at small firms. Size‑contingent regulations are used in many different areas including taxation, labour, accounting and finance (Arregui, 2023[27]). They weaken incentives for small firms to grow their business and provide an unfair competitive advantage to small firms (González Pandiella, 2014[28]). Differences in regulations across regions constrain firm growth by limiting market size. Harmonising regulations across regions, in line with the Market Unity Law, could help to promote business growth, by increasing effective market size, supporting economies of scale, and strengthening competition between firms (Adalet McGowan and San Millán, 2019[29]; OECD, 2023[3]). Finally, direct support measures should be targeted primarily at young firms rather than small firms as this has been shown to increase the effectiveness of public spending (OECD, 2018[30]). Depending on their precise implementation, size‑based measures also carry the risk of further weakening incentives for small firms to grow.

Distribution of employment by firm-size group, 2020 or latest

Note: Services include non-financial market services. OECD is the unweighted average among the countries analysed.

Source: OECD Database on Structural and Demographic Business Statistics (SDBS).

Apart from supporting the productivity in less productive firms, there is also a need to allocate resources more efficiently between less productive firms with structural difficulties to more productive firms with healthy growth prospects.

Indeed, there are signs that the process of job reallocation from less to more productive firms has become less effective over time in Spain as well as in many other OECD countries. Across the OECD, there has been a secular decline in firm entry and exit rates and the speed of job reallocation from less to more productive firms over the past couple of decades (Adalet McGowan, Andrews and Millot, 2017[31]; Calvino, Criscuolo and Verlhac, 2020[32]). Moreover, in almost all major OECD countries, and in particular in Spain, employment has shifted from manufacturing to service sectors (e.g. restaurants, health and residential care activities), where productivity tends to be lower (Sorbe, Gal and Millot, 2018[33]; OECD, 2018[4]). This has been a moderate but persistent drag on labour productivity growth.

An issue that is particularly relevant for Spain is the relatively high share of firms that are no longer competitive but remain active (OECD, 2019[34]). Since these firms typically exhibit low levels of productivity, their continued survival prevents resources from flowing to more productive firms, holding back productivity growth (Banerjee and Hofmann, 2018[35]). Indeed, in a well-functioning market, insolvent firms, sometimes called “zombie firms”, exit the market, encouraging business creation and entrepreneurship. One reason why this may not happen sufficiently in Spain may be its insolvency regime. An efficient insolvency regime encourages entrepreneurs to take the risk to start a new business and is positively associated with entrepreneurship and productivity growth. As an important step in this direction, Spain has reformed its insolvency regime in 2022 by facilitating pre‑insolvency actions and out-of-court negotiations (OECD, 2023[3]).

Employment protection regulation, which is relatively strict in Spain (see Chapter 3), may also slow the process of efficient job reallocation and hence productivity growth (OECD, 2020[36]). It can do so by reducing the ease with which firms can adjust employment in response to changing business conditions and by weakening the incentives of workers to move to more productive firms (for example because they would lose accumulated entitlements to severance pay). Yet, employment protection can also support productivity growth by strengthening incentives for the accumulation and preservation of firm-specific human capital in the workplace and by promoting the use of high-performance work and management practices based on long-term employer-employee relationships. In the end, therefore, the key question is whether employment protection strikes the right balance between supporting job reallocation and providing incentives for learning and innovation in the workplace. The role of employment protection for productivity growth, including the 2021 reform, is discussed in detail in Chapter 3.

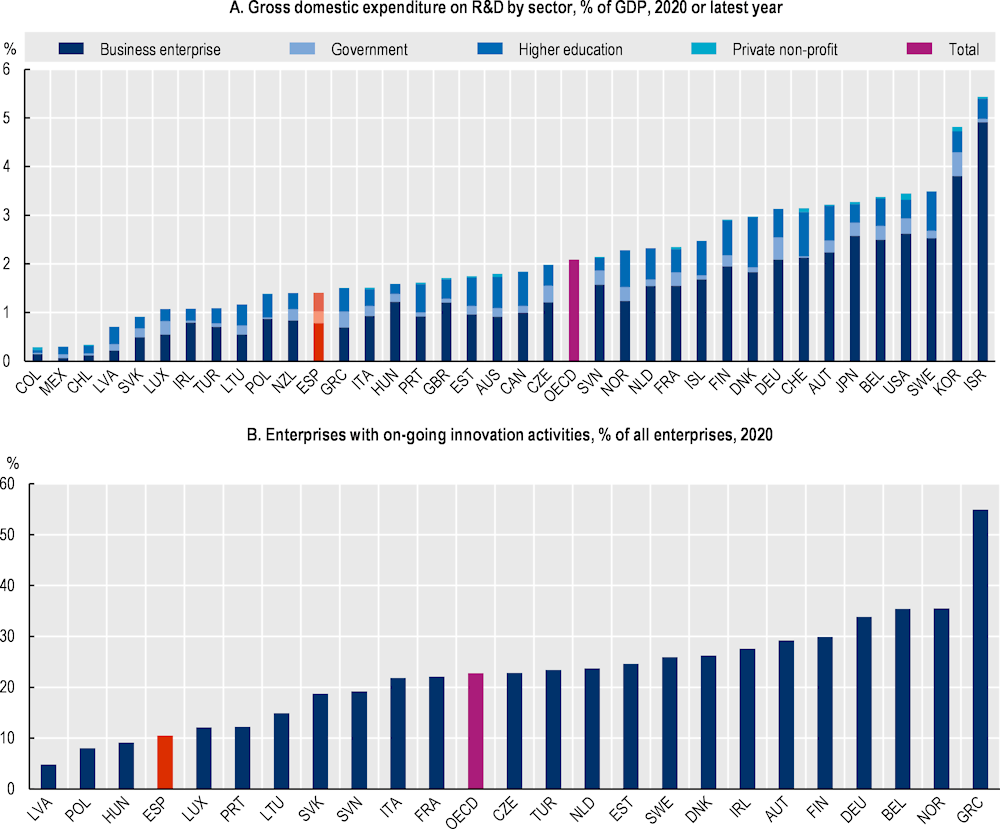

While productivity growth among frontier firms has remained robust, there are concerns about their ability to do so in the future since innovation is rather low. Indeed, Spain is among the OECD countries that spend the least on innovation. Only 1.4% of GDP is spent on R&D, two‑thirds of the OECD average (Figure 2.13, Panel A). Spanish firms also lag behind in terms of public-private partnerships (OECD, 2021[14]), process innovations and non-R&D innovative spending (Arregui and Shi, 2023[23]). In addition, Spain is among the OECD countries with the lowest share of innovative firms. In 2020, 11% of firms had ongoing innovation activities, half the OECD average (Figure 2.13, Panel B).

Collaboration between private firms and public research institutions in particular can be an effective approach to promote innovation (OECD, 2023[3]). In this spirit, the new public-private partnerships implemented under the Recovery, Transformation and Resilience Plan have been created to bring together various actors, including SMEs in technology clusters. Industry and civil society could play a stronger role in the university governance system, and firms should be encouraged to hire PhDs. To enhance the effectiveness of measures to support innovation their rigorous assessment is crucial. The reformed Law on Science, Technology and Innovation goes in the right direction by giving a Science, Technology and Innovation Advisory Board the responsibility to promote the introduction of evaluation mechanisms. A strengthened evaluation framework in turn could facilitate performance‑based funding. Given the major role played by regions in the design and implementation of innovation policy, improving co‑operation between regions, but also with central government, could increase the effectiveness of innovation policies through synergies and knowledge spillovers (Adalet McGowan and San Millán, 2019[29]).

Note: OECD is the unweighted average among the countries analysed.

Source: OECD (2023[3]), OECD Economic Surveys: Spain 2023.

Tackling disparities in productivity requires place‑based policies to support disadvantaged regions and policies that can promote geographical mobility from disadvantaged regions to high-performing regions.

Public investment in public employment services, education and infrastructure is key to support disadvantaged regions and facilitate the diffusion of innovation and good practice between regions. To effectively administer and implement large‑scale investment projects, education and employment programmes, a good co‑operation between national, regional and local governments is essential. To ensure efforts are focused on the most promising projects, it is important to have well-established and transparent procedures for their selection and the way they are awarded to private contractors (OECD, 2018[1]).

Supporting skills development in disadvantaged regions is particularly important. The supply of skills in some regions may be as low as in some of the lowest-performing OECD countries, as shown in Figure 2.14 focusing on mathematical skills. Redirecting resources for education, training and employment policies towards lagging regions would enhance the career opportunities of workers in these regions and enable firms to find the skills they need in the local workforce and develop new opportunities for investment.

Apart from mobilising more resources, it is also important to increase policy effectiveness. Benchmarking services and evaluating polices at the regional level are crucial in this regard (Adalet McGowan and San Millán, 2019[29]). Greater interregional co‑operation could help to enable regions with insufficient resources to carry out high-quality evaluations. This co‑operation could take the form of an independent National Evaluation Agency responsible for regularly evaluating regional policies. It could build on the existing sectoral conferences, which aim to co‑ordinate policies between regional authorities and central government. Evaluations can be used to identify best practices as well as cases where improvements are needed. Policy guidance and funding could be provided to promote the adoption of best practices in lagging regions, in line with the recent Programa de Aprendizaje Mutuo (Adalet McGowan and San Millán, 2019[29]) or the 2023 Employment Law that seeks to modernise active labour market policies, by standardising basic services and promoting impact analysis.

Mean PISA scores in mathematics, 2018

Note: In 2018, some regions in Spain conducted their high-stakes exams for tenth-grade students earlier in the year than in the past, which resulted in the testing period for these exams coinciding with the end of the PISA testing window. Because of this overlap, a number of students were negatively disposed towards the PISA test and did not try their best to demonstrate their proficiency. Although the data of only a minority of students show clear signs of lack of engagement (see PISA 2018 Results Volume I, Annex A9), the comparability of PISA 2018 data for Spain with those from earlier PISA assessments cannot be fully ensured. OECD is the unweighted average among the countries analysed.

Source: OECD (2019[37]), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en.

Spain’s high degree of decentralisation and large regional disparities can hamper the efficient allocation of labour (Adalet McGowan and San Millán, 2019[29]), as workers and jobseekers may find it difficult to move from one region to another: the annual regional migration rate in Spain was only 1.2% during 2017‑21, less than half the OECD average (2.6%) (Figure 2.15).

Policy measures to promote labour mobility are those that limit the potential losses of workers and jobseekers moving from one region to another. First, one can ensure that social assistance and ALMP entitlements are transferable between regions. A recent example is the “social card”, which centralises all non-contributory benefits received, regardless of their source (national, regional or local) (Adalet McGowan and San Millán, 2019[29]). Second, ensuring availability of affordable housing also can help to promote geographical mobility. Housing allowances, rent ceilings or social housing, targeted to those most in need are useful tools. For example, the 2018‑21 National Housing Plan includes a housing allowance for low-income youth and families (Adalet McGowan and San Millán, 2019[29]).

Annual regional migration rate (Flows across TL3 regions, average 2017‑21, percentage of total population)

Note: Average 2017‑21, otherwise available years: 2017 for Chile, Poland and the United States; 2017‑18 for Australia and Italy; 2019‑21 for France and Latvia. OECD is the unweighted average among the countries analysed.

Source: OECD Regional Database.

Note: Data are measured in constant prices 2015 USD purchasing power parities. OECD is the unweighted average among the countries analysed.

Source: OECD Productivity Statistics Database.

Productivity growth in Spain has been persistently weak for several decades. Productivity growth started slowing in the mid‑1990s, earlier than in most other OECD countries, and its slowdown has been particularly pronounced. In recent years, it averaged just 0.5% per year, compared with 1.2% for the OECD as whole. As a result, productivity performance has fallen below the OECD average, with important implications for real wage growth and the standard of living. In fact, real wage growth since the 1990s has been close to zero, as it failed to keep up even with weak productivity growth.

The slowdown in productivity growth reflects three key challenges. While many OECD countries have been confronted with similar challenges, they have tended to be more pronounced in Spain.

Lower multi-factor productivity (MFP) growth. Low MFP growth is in part due to difficulties with adapting to technological change and globalisation. This reflects barriers to the adoption of more efficient technologies and work practices in firms and a mismatch between the skills of workers and those required by employers.

Lower capital deepening. Lower capital deepening is largely due the persistent decline in investment following the global financial crisis. The decline in investment was particularly sharp in Spain due to the collapse of the housing bubble and the ensuing banking crisis. It has failed to fully recover due to low MFP growth, high economic uncertainty and enduring financial weaknesses.

Growing disparities in productivity. Growing disparities mainly reflect lagging productivity growth in low productivity firms and regions. This reflects the slow diffusion of new technologies from frontier firms to other firms and inefficiencies in the allocation of resources from low to high productivity firms. Productivity growth has remained robust in frontier firms.

The recent acceleration in the importance of digital technologies and the development of generative artificial intelligence (AI) creates important new opportunities for productivity growth. However, if history is a guide, seizing upon them may be a challenge unless the causes of weak productivity growth are effectively addressed.

To revive productivity growth, it will be important to address persistent skill imbalances that limit the adoption of new technologies, promote the development of more efficient technologies and their diffusion to less productive firms, reduce regulatory barriers for firms to grow and flourish, and tackle regional disparities in productivity.

Investing in education and training. The education and training system could become more inclusive by continuing efforts to reduce early school leaving and remedying skills gaps through second-chance schools, and more responsive to evolving labour market needs by expanding enrolment in vocational education and training based on a combination of school and work-based learning, reinforcing the culture of life‑long learning, and involving employers more strongly in the education and training system.

Supporting productivity growth in firms. This requires promoting the adoption of advanced digital technologies in lagging firms by increasing access to digital infrastructure and access to credit to promote investment in intangible assets, including managerial and organisational capital (e.g. management practices). It also requires supporting the reallocation of resources from low-productivity firms with structural difficulties to more productive firms with healthy growth prospects.

Tackling regional disparities in productivity. This requires public investments in the quality of education, employment services and infrastructure in lagging regions, including by identifying best practices and providing technical and financial support to local providers, and supporting regional mobility by ensuring social entitlements are portable across regions and promoting the availability of affordable housing in more advanced regions.

[31] Adalet McGowan, M., D. Andrews and V. Millot (2017), “The Walking Dead?: Zombie Firms and Productivity Performance in OECD Countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1372, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/180d80ad-en.

[29] Adalet McGowan, M. and J. San Millán (2019), “Reducing regional disparities for inclusive growth in Spain”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1549, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9acff09a-en.

[7] Ahmad, N., J. Ribarsky and M. Reinsdorf (2017), “Can potential mismeasurement of the digital economy explain the post-crisis slowdown in GDP and productivity growth?”, OECD Statistics Working Papers, No. 2017/9, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/a8e751b7-en.

[10] Andrews, D., C. Criscuolo and P. Gal (2016), “The Best versus the Rest: The Global Productivity Slowdown, Divergence across Firms and the Role of Public Policy”, OECD Productivity Working Papers, No. 5, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/63629cc9-en.

[27] Arregui, N. (2023), Labor Productivity Dynamics in Spain: A Firm-Level Perspective, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/Selected-Issues-Papers/2023/English/SIPEA2023002.ashx.

[23] Arregui, N. and Y. Shi (2023), Labor Productivity Dynamics in Spain: A Firm-Level Perspective, International Monetary Fund, https://www.imf.org/-/media/Files/Publications/Selected-Issues-Papers/2023/English/SIPEA2023002.ashx.

[16] Autor, D., F. Levy and R. Murnane (2003), “The Skill Content of Recent Technological Change: An Empirical Exploration”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 118/4, pp. 1279-1333, https://doi.org/10.1162/003355303322552801.

[35] Banerjee, R. and B. Hofmann (2018), “The rise of zombie firms: causes and consequences”, BIS Quarterly Review, https://www.bis.org/publ/qtrpdf/r_qt1809g.htm.

[8] Berlingieri, G. et al. (2020), “Laggard firms, technology diffusion and its structural and policy determinants”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 86, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/281bd7a9-en.

[20] Boto-García, D. and M. Escalonilla (2022), “University education, mismatched jobs: are there gender differences in the drivers of overeducation?”, Economia Politica, Vol. 39, pp. 861–902, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40888-022-00270-y.

[6] Brynjolfsson, E., D. Rock and C. Syverson (2021), “The Productivity J-Curve: How Intangibles Complement General Purpose Technologies”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 13/1, pp. 333-372, https://doi.org/10.1257/mac.20180386.

[32] Calvino, F., C. Criscuolo and R. Verlhac (2020), “Declining business dynamism: Structural and policy determinants”, OECD Science, Technology and Industry Policy Papers, No. 94, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/77b92072-en.

[9] Gal, P. et al. (2019), “Digitalisation and productivity: In search of the holy grail – Firm-level empirical evidence from EU countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1533, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5080f4b6-en.

[18] Georgieff, A. and R. Hyee (2021), “Artificial intelligence and employment : New cross-country evidence”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 265, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c2c1d276-en.

[28] González Pandiella, A. (2014), “Moving Towards a More Dynamic Business Sector in Spain”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1173, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5jxszm2k7fnw-en.

[22] IMF (2023), “IMF Country Report 23/33: Spain 2022 Article IV Staff Report”, International Monetary Fund.

[26] Lopez-Garcia, P. and J. Montero (2012), “Spillovers and absorptive capacity in the decision to innovate of Spanish firms: the role of human capital”, Economics of Innovation and New Technology, Vol. 21/7, pp. 589-612, https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2011.606170.

[13] Ministerio de Asuntos Económicos y Transformación Digital (2023), Plan de Recuperación. Impacto macroeconómico.

[17] Nedelkoska, L. and G. Quintini (2018), “Automation, skills use and training”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 202, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/2e2f4eea-en.

[25] OECD (2023), OECD Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2023, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/74623e5b-en.

[12] OECD (2023), OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report March 2023: A Fragile Recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/d14d49eb-en.

[3] OECD (2023), OECD Economic Surveys: Spain 2023.

[14] OECD (2021), OECD Economic Surveys: Spain 2021, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/79e92d88-en.

[2] OECD (2021), OECD Employment Outlook 2021: Navigating the COVID-19 Crisis and Recovery, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5a700c4b-en.

[11] OECD (2020), “COVID‑19: From a health to a jobs crisis”, in OECD Employment Outlook 2020: Worker Security and the COVID-19 Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/cea3b4f4-en.

[36] OECD (2020), “Recent trends in employment protection legislation”, in OECD Employment Outlook 2020: Worker Security and the COVID-19 Crisis, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/af9c7d85-en.

[34] OECD (2019), In-Depth Productivity Review of Belgium, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/88aefcd5-en.

[21] OECD (2019), “Individual Learning Accounts: Design is key for success”, Policy Brief on the Future of Work, https://www.oecd.org/employment/individual-learningaccounts.pdf.

[37] OECD (2019), PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en.

[1] OECD (2018), Good Jobs for All in a Changing World of Work: The OECD Jobs Strategy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264308817-en.

[4] OECD (2018), OECD Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/pdtvy-2018-en.

[30] OECD (2018), OECD Economic Surveys: Spain 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-esp-2018-en.

[19] OECD (2006), Starting Strong II: Early Childhood Education and Care, Starting Strong, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264035461-en.

[24] Pisu, M. et al. (2021), “Spurring growth and closing gaps through digitalisation in a post-COVID world: Policies to LIFT all boats”, OECD Economic Policy Papers, No. 30, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b9622a7a-en.

[15] Salvatori, A. (2022), “A tale of two crises: Recent labour market developments across the OECD”, in OECD Employment Outlook 2022: Building Back More Inclusive Labour Markets, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/ddfa64a7-en.

[33] Sorbe, S., P. Gal and V. Millot (2018), “Can productivity still grow in service-based economies?: Literature overview and preliminary evidence from OECD countries”, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1531, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/4458ec7b-en.

[5] Ward, A., M. Zinni and P. Marianna (2018), “International productivity gaps: Are labour input measures comparable?”, OECD Statistics Working Papers, No. 2018/12, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/5b43c728-en.

← 1. This is true when measuring labour productivity in terms of total hours worked or the number of persons employed (see Figure 2.16).

← 2. The correlation coefficient between productivity levels and productivity growth across regions is positive but relatively weak (0.3).

← 3. The minimum wage level is 60% of the wage for the equivalent category of employee in the first year of education and 75% in the second year, subject to the interprofessional minimum wage.

← 4. Spain is above average in terms of total expenditure on training as a percentage of GDP. This may suggest that the challenge is mainly one of targeting resources to those who need training the most rather than the overall level of spending.