Andrea Garnero

Alexandre Georgieff

Alexander Hijzen

Andrea Garnero

Alexandre Georgieff

Alexander Hijzen

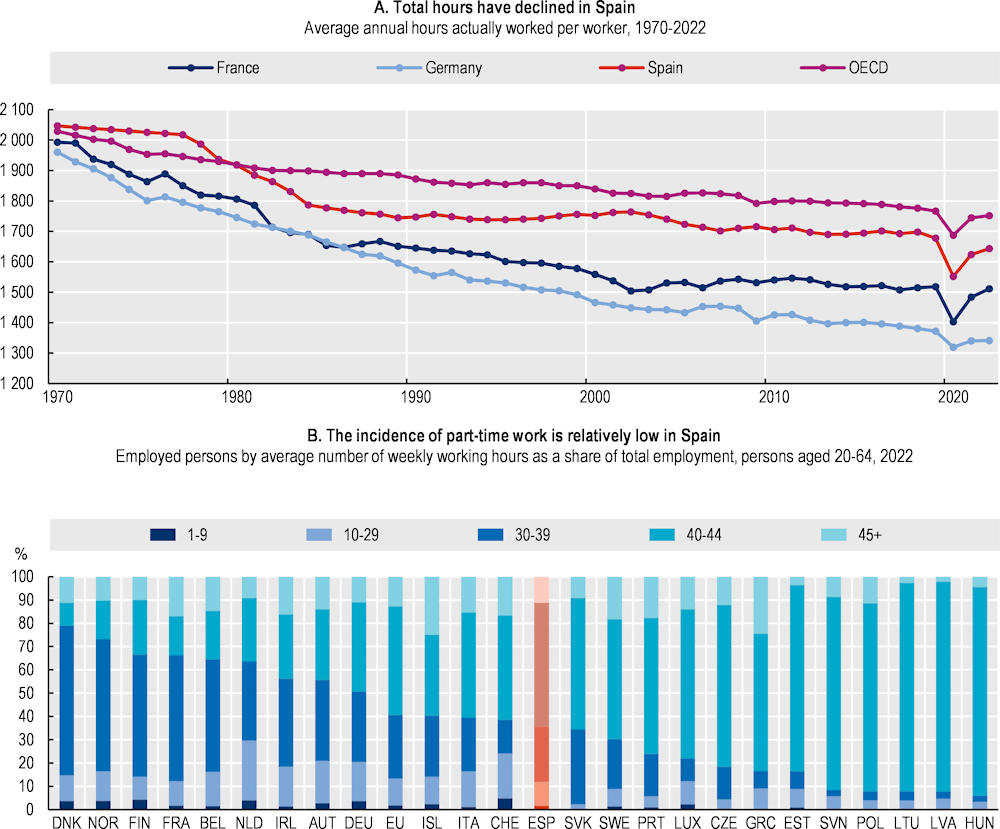

This chapter discusses the role of labour market policies in supporting broadly shared productivity gains. Particular emphasis is placed on the recent labour market reforms in relation to wage‑setting institutions, employment protection and job retention support. It provides three key insights. Wage‑setting institutions in the form of minimum wages and collective bargaining have been significantly strengthened to promote a broader sharing of productivity gains with workers, particularly those with low wages. The use of temporary contracts has been significantly restricted to combat labour market duality. This has resulted in a sharp decline in the number of temporary contracts and an equally sharp increase in the number of permanent contracts in the year following the reform. Job retention support in the form of ERTE has been reformed, defining the parameters of the permanent scheme, while introducing an innovative mechanism for scaling up support in emergency situations (the so-called “RED mechanism”).

The objective of this chapter is to discuss the role of labour market policies in reviving productivity growth and ensuring that productivity gains are broadly shared through higher wages and better employment opportunities, particularly for groups with a weak position in the labour market.

The labour market policies considered in this chapter are primarily designed to promote working conditions in terms of wages (minimum wage and collective bargaining), job security (employment protection and job retention schemes) as well as other work arrangements (working time), consistent with the OECD framework for the measurement and assessment of job quality (Cazes, Hijzen and Saint-Martin, 2015[1]). These policies primarily seek to promote a broader sharing of productivity gains by setting legal minima for wages or non-wage working conditions or indirectly by supporting the bargaining position of workers. However, they also can have important implications for productivity as well as employment.

The OECD Jobs Strategy of 2018 argues that good working conditions can contribute to raising productivity within firms by fostering long-term employer‑employee relationships, and by doing so, strengthen incentives to invest in skills, technologies and innovation and the adoption of high-performance work and management practices (OECD, 2018[2]). The challenge for policy is to provide the conditions for learning and innovation in the workplace while, at the same time, provide sufficient flexibility to allow for the efficient reallocation of workers between firms that differ in their productivity.

Relatively little is known about the productivity effects of wage‑setting institutions (e.g. minimum wages, collective bargaining). In the OECD Jobs Study of 1994, wage‑setting institutions were regarded with considerable skepticism due to the risk of pricing low-skilled workers out of the market, and hence further increasing unemployment at a time when this was a primary policy concern, and the risk of undermining the efficient allocation of workers across firms by mitigating incentives for job mobility and investing in human capital (OECD, 1994[3]). The contrast with the new OECD Jobs Strategy of 2018 is striking (OECD, 2018[2]). Because of the greater emphasis on job quality, wage‑setting institutions are seen as an integral part of the toolkit to promote good jobs for all workers by ensuring that productivity gains are broadly shared. Indeed, the focus is on how the effectiveness of wage‑setting institutions can be enhanced and any potentially adverse consequences mitigated. The more positive view on wage‑setting institutions also reflects a stronger recognition of the role of firms in wage‑setting. Whereas according to the traditional view wages are fully determined by the demand and supply for skills, it is now widely recognised that wages also depend on the firm for which one works, as firms have some power to set wages due to the presence of labour market frictions (OECD, 2021[4]).

The main insight provided in this section is that wage‑setting institutions, in the form of both statutory minimum wages and collective bargaining, have been significantly strengthened in Spain in recent years. The minimum wage was increased from a relatively low level in 2018, well below the OECD average, to a level well above the OECD average in 2023. Similarly, the 2021 labour market reform significantly strengthened collective bargaining, notably at the sectoral level. These reforms are likely to contribute to a broader sharing of productivity gains with workers, particularly those with low wages and as such counter the decoupling of wage growth from productivity growth since the global financial crisis (see Chapter 2). It is too early to provide a full assessment of their effects reforms for employment and productivity. An early assessment of the 2019 minimum wage reform suggests that it significantly boosted the wages of directly affected workers, without significantly reducing their employment (Hijzen, Pessoa and Montenegro, 2023[5]). The section concludes with a number of considerations that may help to further improve the role of wage‑setting institutions in promoting broadly shared productivity gains in Spain.

The statutory minimum wage was introduced in Spain in 1964. Initially, the minimum wage was differentiated across regions and sub-minima existed for teenagers below 18. Since 1998, there has been a unique national minimum wage for all workers, irrespective of their age or region where they work. The minimum wage is set each year by the Spanish Government by Royal Decree. Decisions are made on a discretionary basis in consultation with the social partners, taking account of past and predicted inflation as well as general economic conditions. Since 2021, an advisory commission provides independent recommendations on the desired future evolution of the minimum wage.

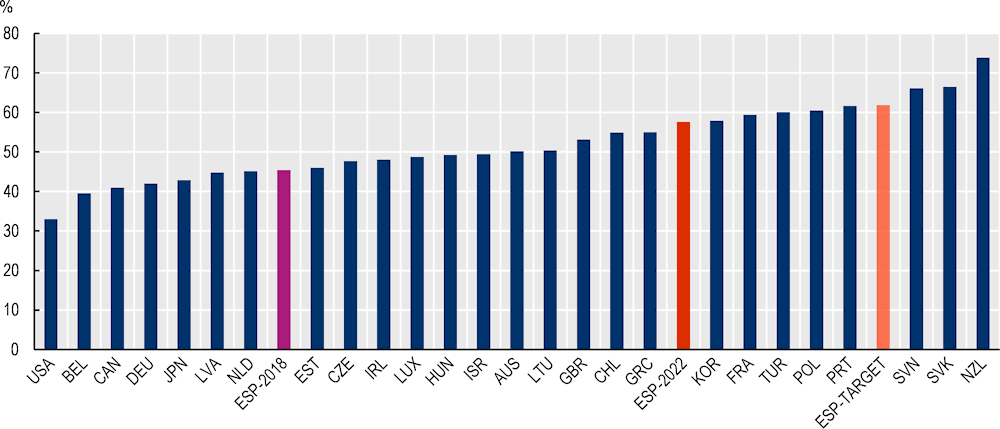

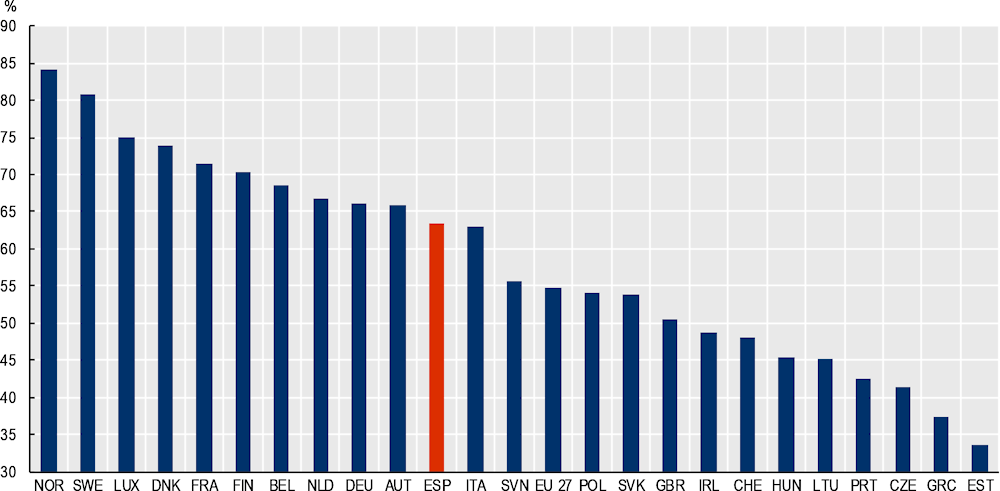

The minimum wage has gained significantly in importance as a policy tool in recent years in Spain (Figure 3.1, Panel A), in line with a more general global trend.1 Until 2018, it played only a modest role as it was set at a relatively low level by OECD standards, around 45% of the median wage in the private sector. However, it has increased rapidly since to 58% of the median wage in 2022, with most of the increase taking place in 2019 when it was increased by 22% in a single step. In 2020, an advisory commission (Comisión asesora para el análisis del salario mínimo, CASSMI) was created by the government. It consists of experts from academia, social partners and the Ministry of Labour and Social Economy, the Ministry of Finance and the Ministry of Economic Affairs and Digital Transformation. Its first main task was to define a path towards reaching a MW at 60% of the average net wage by 2023, which corresponds to about 62% of the gross median wage.

With the sharp rise in prices in most OECD countries, minimum wages have become an even more important tool to protect the standard of living of low-paid workers. The recent increases in 2022 and 2023 in Spain have allowed the minimum wage to keep up with inflation (OECD, 2023[6]). While such upratings of the minimum wage have been crucial to protect the standard of living of low-wage workers, they have also raised concerns in some OECD countries, notably those where inflation remains high.

In an inflationary context, one concern is that minimum-wage increases could contribute to a wage‑price spiral. Most empirical studies agree that part of minimum-wage increases is passed onto consumers – see e.g. Harasztosi and Lindner (2019[7]). However, the extent to which this is the case depends on the bite of the minimum wage as well as on the way it is set.2 ECB (2022[8]) and OECD (2023[6]) show that in most countries the effects of minimum-wage increases on aggregate wage growth are quite limited. This is even the case for major increases due to the limited number of workers directly affected by them. While there is no direct evidence for Spain, given the bite of the minimum wage and the current level of inflation, the risk of a wage‑price spiral driven by increases in the minimum wage appears very limited. Moreover, in Spain like in other OECD countries, profits have increased more than labour costs, which suggests that there is room for profits to absorb some further increases in wages to mitigate the loss of purchasing power, at least for the low paid, without generating significant additional price pressures.

Another potential concern relates to the consequences of wage compression for employment and productivity growth. Increases in the minimum wage without similarly sized increases in wages higher up in the distribution induce wage compression. In principle, a squeezing of the wage distribution could reduce employment among low-wage workers, while weakening incentives to move to better firms, slowing efficiency-enhancing job reallocation. It could also reduce incentives of higher-wage workers to provide effort. That said, there is limited empirical evidence on the importance of these mechanisms and the effects of wage compression on employment and productivity more generally. This is an important area for future research.

Minimum wage as a share of median wage, 2022 unless indicated otherwise

Notes: The figure represents the minimum gross wage in 1 January 2022 as a share of the 2022 gross median wage in the private sector (unless stated otherwise). ESP‑2018 refers to the 2018 minimum gross wage as a share of the gross median wage for 2018. ESP‑target refers to the target minimum gross wage equivalent to 60% of the average net wage as a share of the median gross wage in 2022.

Source: OECD Tax-Benefit model.

Despite the growing interest in minimum wages as a policy instrument to promote fair wages and broadly shared productivity gains, some controversies remain about their alleged employment effects. A traditionally influential view based on the competitive‑market paradigm holds that minimum wages reduce employment by pricing low-skilled workers out of the market. This view was however challenged in the ground-breaking study by Card and Krueger (1994[9]) that showed that minimum wages may have positive rather than negative employment effects. This is consistent with the presence of labour market frictions that confer wage‑setting power to employers. Subsequent studies have sought to improve on data and research designs, while shedding light on the underlying mechanisms. While the majority of studies does not show large negative employment effects, the issue continues to be debated (see, among others, Manning (2021[10]), Dube (2019[11]) and Neumark et al. (2021[12]) for recent surveys).

A number of recent studies have analysed the 2019 minimum wage hike in Spain. There is a broad consensus that the increase in the minimum wage significantly increased the wages of low-wage workers, reduced wage inequality and alleviated in-work poverty (Arranz and García, 2022[13]; Cárdenas et al., 2022[14]; Granell, Fuenmayor and Savall, 2022[15]). At the same time, there is little indication that the increase in minimum wages has significantly reduced employment among low-wage workers. While a number of ex ante studies, including one by the Bank of Spain (2017[16]), raised significant concerns about job losses, these concerns have not materialised to the expected extent. Ex post studies by Gorjon et al. (2022[17]) and Hijzen at al (2023[5]) point to small negative employment effects (see Box 3.1), while larger negative estimates are reported in Barcelo et al. (2021[18]). All in all, the emerging evidence for the 2019 minimum wage hike suggests that the minimum wage increase of 2019 boosted the wages of low-wage workers and reduced wage inequality, without significantly undermining job opportunities for low-wage workers.

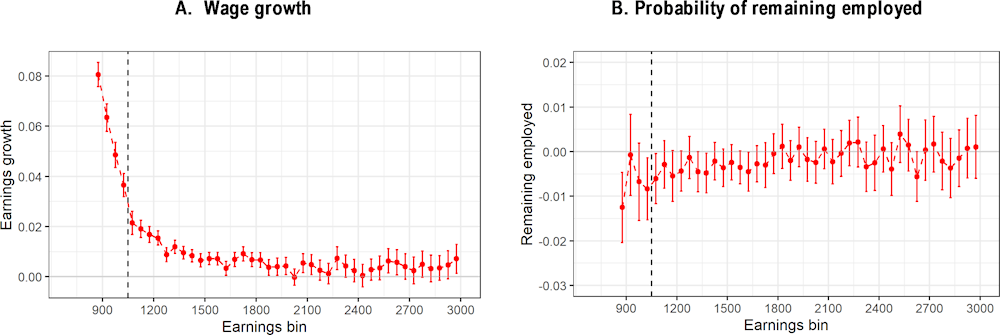

In recent OECD work, Hijzen et al (2023[5]) provide an assessment of the 2019 minimum-wage hike in Spain. This increased the minimum wage by 22% in a single step and directly affected about 7‑8% of dependent employees. The assessment is based on an individual-level analysis that follows the outcomes of workers that were employed in the year before the reform over time. Among directly affected workers, the hike in the minimum wage increased full-time equivalent monthly earnings by on average 5.8% and reduced employment by 0.6% (about 7 000 jobs), which implies a small own-wage labour-demand elasticity of ‑0.1. Further analysis suggests that estimated job losses tended to be concentrated among workers on fixed-term contracts. In sum, the hike in the minimum wage significantly increased the wages of low-wage workers, but only resulted in a very limited reduction in the probability of remaining employed.

Change in outcome between 2018 and 2019 relative to that between 2017 and 2018

Notes: Estimated coefficients plus 95% confidence intervals based on clustered standard errors by province, industry and wage bin.

Source: (Hijzen, Pessoa and Montenegro, 2023[5]), “Minimum wages in a dual labour market: Evidence from the 2019 minimum-wage hike in Spain”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 298, https://doi.org/10.1787/7ff44848-en.

The minimum wages may affect aggregate productivity directly through their effect on the productivity of firms (upgrading) and indirectly through changes in the structure of employment across firms that differ in their productivity (efficiency-enhancing job reallocation).3

Productivity effects within firms due to the minimum wage may arise for different reasons, and if they arise, are most likely to be positive. A higher wage may induce workers to exert more effort as implied by efficiency-wage theory (Akerlof, 1982[19]; Georgiadis, 2013[20]). Higher labour costs may also induce firms to invest in capital or to adopt more efficient working practices, based on for example long-term contracting and investment in firm-specific training, to boost the productivity of workers. There is some empirical evidence that the introduction of the minimum wage in the United Kingdom increased firm productivity through the adoption of more efficient work practices (Riley and Rosazza Bondibene, 2017[21]). From a policy perspective, the key challenge is to support firms employing minimum-wage workers with raising their productivity. As discussed in Chapter 2, this includes, amongst others, policies that support investment in human capital and other intangible assets, promote framework conditions for the digital age and improve access to digital infrastructures (OECD, 2021[22]).4

Aggregate productivity effects may also reflect the impact of the minimum wage on job reallocation between less and more productivity firms. Such reallocation effects will be positive and more pronounced when i) firms that make intensive use of minimum-wage workers are less productive, ii) firms that make intensive use of minimum-wage workers are more negatively affected by a minimum wage increase in terms of profitability (Draca, Machin and Van Reenen, 2011[23]; Bell and Machin, 2018[24]), employment and firm survival (Luca et al., 2019[25]); and iii) more productive firms respond by creating more jobs (Drucker, Mazirov and Neumark, 2019[26]; Dustmann et al., 2021[27]). Such “firm-driven” reallocation may, however, be mitigated by slower “worker-driven reallocation” as the minimum wage compresses wage differences between firms, weakening incentives for voluntary job mobility from less to more productive firms (OECD, 2018[2]).

The cost and benefits of changes in job reallocation driven by an increase in the minimum wage are likely to depend on the ease with which displaced workers can find new jobs. Finding a new job following displacement is likely to be easier in market-reliant countries that emphasise flexible product and labour markets as well as in countries with a strong emphasis on public policies to support job transitions. Among a sample of European countries, Bertheau et al. (2022[28]) point in particular to the importance of comprehensive activation policies in limiting the earnings losses of job displacement due to time spent out of work. To promote worker-driven job mobility between firms, activation services should also be made available to workers who are stuck in low-quality jobs and would like to make a career change.

The effectiveness of the minimum wage in boosting the incomes of workers and their families and its consequences for employment and productivity depend importantly on the way it is designed.

The process for adjusting minimum wage rates varies across OECD countries. In most OECD countries, the minimum wage tends to be adjusted annually with a short delay between the decision and the application. In other countries, the minimum wage is adjusted annually or biannually but with a slightly longer delay which may make a difference in times of high and/or rising inflation. In some countries, there is no regular adjustment, which may result in long delays and major losses in purchasing power. In the United States, for instance, the federal minimum wage has not been increased since 2009 (while minimum wages at state and local level have been updated much more regularly). In years of high inflation, multiple increases in minimum wages can take place during the year in comes countries (e.g. Belgium, France and Luxembourg).

The revision of minimum wages may be subject to government discretion or can take place automatically in the case of indexation. In some OECD countries – notably, Belgium, Canada (since April 2022), Costa Rica, France, Israel, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Poland – there is a form of automatic indexation of the minimum wage to the nation-wide level of wages or prices. Minimum wages are for instance indexed to negotiated wages (i.e. wages defined in collective agreements) in the Netherlands, and to actual wages in Israel. Indexation to (past) prices occurs in countries such as Belgium, Canada, France5 and Luxembourg.6 Poland links its minimum wage to future price developments and corrects it ex post in case of differences between the forecasts and the realised rates. A few countries have a form of indexation that kicks in only if social partners fail to find an agreement (Colombia and the Slovak Republic).

In several OECD countries, minimum wage commissions provide advice (more or less binding) in setting the level the minimum wage (including Australia, France, Germany, Greece, Korea, Ireland, Mexico, the United Kingdom). The operation of these bodies varies from country to country in terms of the advisory (e.g. France) or legally binding (e.g. Australia) nature of their recommendations, the extent to which the view of the social partners are taken into account and their independence. In France, for instance, the commission has only an advisory role on the discretionary increase that the government can add to the automatic increase due to price and productivity increases. In Ireland and the United Kingdom, the commissions are composed of experts and representatives of the social partners and the governments can deviate from the recommendations but have to justify the deviation in parliament. In Germany, the government can refuse the recommendation of the minimum wage commission, which is composed by social partners and two experts without voting rights but cannot change it. In Australia, the Fair Work Commission is entirely independent, and its decisions are legally binding.

The experience of minimum wage commissions in OECD countries shows that they are particularly well placed to give objective recommendations, based on a wide range of economic and social factors. The work of the Spanish CASSMI should continue to be supported. Its contribution to produce and commission independent research on a range of issues related to the minimum wage has enriched the public debate and provided a useful evidence base for the government. Social partners, including the employers’ organisations, which decided not to take part to the latest deliberations, should continue to be closely involved in the process and the government should commit to respect the advice of the commissions, or in the alternative, explain in a public statement why it disagrees. The resources available to CASSMI should be strengthened to monitor and evaluate the effects of the minimum wage on the labour market. This also requires mobilising administrative data that allow tracking the wages of individual workers in a timely manner (the social security data provide the ideal source for this in the case of Spain).

|

Delay between the decision and application lower or equal to two months |

Delay between the decision and application higher than two months |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Regular adjustment on a fixed date |

Australia Canada (Federal) Colombia Costa Rica France Hungary Japan Luxembourg Mexico Poland Portugal Slovenia Switzerland (5 Cantons) Türkiye |

Estonia Germany Ireland Korea Lithuania Netherlands New Zealand Slovak Republic Spain United Kingdom |

|

No regular adjustment |

Belgium Chile Czech Republic (Czechia) Greece United States (Federal) |

Latvia |

Note: Switzerland (5 Cantons) refers to the five cantons with a statutory minimum wage: Canton of Basel-Stadt, Canton of Geneva, Canton of Jura, Canton of Neuchâtel, and Canton of Ticino.

Source: OECD (2023[6]), OECD Employment Outlook 2023: Artificial Intelligence and the Labour Market, https://doi.org/10.1787/08785bba-en.

|

Country |

Indexation mechanism |

|---|---|

|

Belgium |

The minimum wage is indexed to the so-called “health index”, i.e. past CPI excluding alcohol and tobacco and petrol but including heating fuel, gas, and electricity (every time the index increases by 2% or more since last increase) |

|

Canada |

The minimum wage at the federal level is indexed to the Consumer Price Index for the previous calendar year. Also, nine provinces and territories have a form of indexation. |

|

Costa Rica |

The minimum wage is indexed on the living cost; and the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth. |

|

France |

The minimum wage is indexed to past CPI for the bottom quintile and revised annually or as soon as the CPI increases by 2% or more since last minimum wage increase). Annual revisions also incorporate half real salary increase of blue‑collar workers (only if positive). |

|

Israel |

The minimum wage is anchored to 47.5% of the average wage. |

|

Luxembourg |

All wages are indexed to past CPI (every time CPI increases by 2.5% or more since the last semester) |

|

Netherlands |

The minimum wage is indexed to the predicted wage developments for the next six months using a basket of collectively agreed wages. |

|

Poland |

The minimum wage is indexed to future inflation + 2/3 of future GDP growth if, in the first quarter of the year, the amount of the minimum wage is lower than half of the average wage. If the inflation forecasts differ from the realised evolution of the price index, a correction takes place in the following year. |

|

Switzerland |

In the canton of Neuchâtel, the cantonal minimum wage is automatically adjusted each year to the consumer price index. In the canton of Basel-Stadt, the minimum wage is adjusted (only upwards) according to a mixed index (average of nominal wage and consumer price index). In the canton of Geneva, the minimum wage is indexed to the consumer price index (only upwards). In the canton of Ticino, the government adjusts the lower and upper limits of the cantonal minimum wage annually according to the development of the national price index. |

|

United States |

The federal minimum wage is not indexed. Currently, 13 states and the District of Columbia index state minimum wages to a measure of inflation. In addition, another 6 states are scheduled in a future year to index state minimum wage rates to a measure of inflation. |

Note: In Belgium, it is important to note that all wages are indexed but rules may vary across sectors depending on the collective agreement. Moreover, wage increases in general are capped by a “wage norm” (a ceiling which takes into account weighted wage developments in France, Germany and the Netherlands). In addition, in Colombia, the minimum wage is indexed to prices if social partners fail to find an agreement. In the Slovak Republic, the minimum wage is set at 57% of the average wage of two years before if social partners fail to find an agreement.

Source: OECD (2023[6]), OECD Employment Outlook 2023: Artificial Intelligence and the Labour Market, https://doi.org/10.1787/08785bba-en.

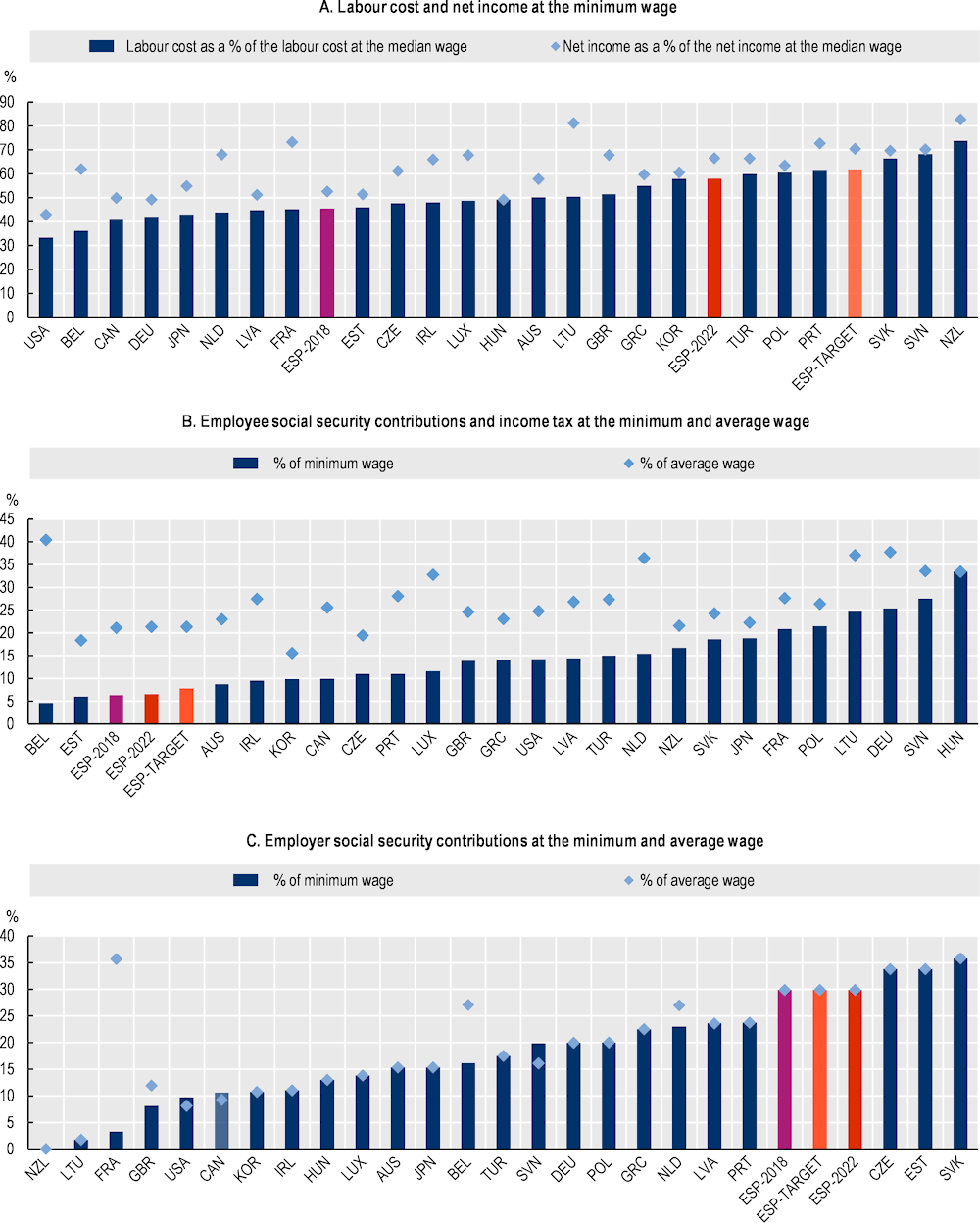

Co‑ordination with the tax-benefits system can help to increase the effectiveness of the minimum wage to make work pay, while mitigating its effects on labour costs and competitiveness. In principle, this can take the form of targeted reductions in employer social security contributions for low-wage workers (e.g. France) or make‑work pay measures targeted at low-wage workers (e.g. France, Ireland, the United Kingdom), including targeted reductions in income taxes or employee social security contributions or the use of tax credits and in-work benefits. France is an example of country with a relatively high gross minimum wage by OECD standards and relatively important tax-benefit measures targeted at low-wage workers. It uses targeted reductions in employer social security contributions to contain the impact of the minimum wage on labour costs and competitiveness and in-work benefits to enhance the effectiveness of the minimum wage in terms of take‑home‑pay.7 As a result, there is a large difference in the labour costs of minimum wage workers for employers and the take‑home pay for minimum wage workers relative to the median (Figure 3.3, Panel A).

2022 unless stated otherwise

Source: OECD Tax-Benefits model.

At present, there is little co‑ordination between the minimum wage and the tax-benefits system in Spain, likely reflecting the fact that, until recently, the need for co‑ordination was limited given the low minimum wage. In Spain, there is currently a small difference between the labour costs for employers and the take‑home pay for workers at the minimum wage relative to the median. As in most OECD countries, minimum wage workers in Spain are exempt from personal income taxes, resulting in somewhat smaller tax wedge for minimum wage workers than those at the median. However, employer and employee social security contribution rates are the same for low and median-wage workers. Moreover, no specific benefits complement take‑home pay for minimum wage workers. With the recent revaluation of the minimum wage, the case for co‑ordination may have become stronger and the different ways in which this could be done deserve to be explored and analysed.

In principle, one option could be to introduce targeted reductions in employer social security contributions, to promote job opportunities for low-skilled workers. While in Spain, employer social security contributions at the minimum wage are among the highest in the OECD, its employment-incentive model already provides an important set of temporary exemptions from employer social security contributions for the hiring of low wage workers, not taken into account by the OECD Tax-Benefits model (Panel C). The pros and cons of permanent exemptions for low-wage workers as in France relative to temporary exemptions for the recruitment of low-wage workers as in Spain are not obvious. While permanent incentives in principle may be more effective in creating job opportunities for low-wage workers, they also come at a significantly higher fiscal cost and carry a larger risk of distorting employment towards low-wage and low-productivity firms, with potentially adverse effects for aggregate productivity growth.

Another option would be to explore how the effectiveness of the minimum wage in reducing in-work poverty could be enhanced further. While employee social security contributions and personal income taxes at the minimum wage are already quite low (Panel B), it may be possible to complement the minimum wage with an in-work benefit for workers in low-income households. In-work benefits represent a more direct tool for addressing in-work poverty than the minimum wage (OECD, 2009[29]), but one that does not carry the risk of pricing low-workers out of the market and supports efficiency-enhancing job reallocation by preserving incentives for job mobility across firms. The recent revaluation of the minimum wage, moreover, may further increase the effectiveness of in-work benefits as a policy tool by reducing the risk that employers use their bargaining position to appropriate in-work benefits intended for workers by lowering their wages. Indeed, this is why the OECD advocates the use of in-work benefits in combination with a moderate minimum wage (OECD, 2018[2]).

In-work benefit (IWB) schemes are designed to create a significant gap between the incomes of people in work as compared with the income that they would get if they were out of work, thereby making work pay, while supporting the incomes of the most vulnerable in or out of work. They pursue, therefore, the twin goal of, on the one hand, enhancing employment and the movement of workers up the earnings ladder and, on the other hand, ensuring a greater inclusiveness of the labour market. In order to avoid creating new disincentives higher up the earnings ladder, IWB must avoid threshold effects by maintaining a sufficiently large phase‑out region over which benefits are withdrawn gradually.

The effectiveness of IWB depends on their targeting, the duration for which they are provided and the way they are operated. First, the effects of in-work benefits on work incentives are more pronounced when targeted at groups that are more sensitive to financial incentives such as lone parents (Immervoll and Scarpetta, 2012[30]). Moreover, in-work benefits are more effective when they are provided permanently, i.e. as long as needed, rather than for a limited maximum duration. The evidence suggests that temporary in-work benefits have limited effects on poverty in the longer-term (Van der Linden, 2016[31]). Finally, IWB systems tend to be more effective when they are operated in a simple and transparent way. If potential beneficiaries do not understand the IWB system, the desired labour-supply response tends to be smaller (Chetty, Friedman and Saez, 2013[32]). This is more likely when the interaction with other taxes and benefits is complex.

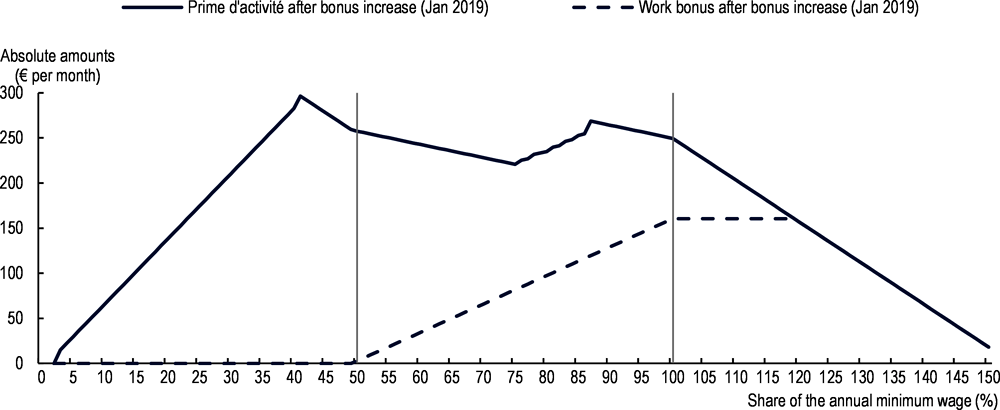

As an illustrative example, Figure 3.4 documents the level of in-work benefits along the wage distribution (expressed as a share of the minimum wage) for the Prime d’Activité in France. As in most other countries, the Prime d’Activité is characterised by a phase‑in region, a plateau and a phase‑out region. The benefit consists of two components: a lump-sum amount that varies by family composition and a work bonus based on individual earnings that phases in at 0.5 times the full-time minimum wage level, from which household income is deducted.

Monthly benefit in euros, 2019

Note: Simulations refer to single household without children after taking account of other taxes and benefits.

Source: Carcillo et al. (2019[33]), “Assessing recent reforms and policy directions in France: Implementing the OECD Jobs Strategy”, https://doi.org/10.1787/657a0b54‑en.

Evidence on the link between collective bargaining and social dialogue on the one hand and productivity is relatively scarce. In principle, their impact on productivity may go in different ways (Freeman and Medoff, 1984[34]). By strengthening the bargaining power of workers, collective bargaining tends to increase wages at the expense of profits, and when conducted at the sector-level, also induces a more compressed wage structure across firms (“monopoly” channel). This has sometimes raised concerns about its potentially adverse effects on investment and resource allocation. These concerns may be more pronounced when collective bargaining is centralised and wage co‑ordination is weak. But by providing a voice for workers and better outcomes, social dialogue and collective bargaining can also help overcome common challenges (e.g. adoption of new technologies or the prevention of work‑related health problems), while strengthening the commitment of workers to their firms, which may raise productivity (“voice” channel). This is more likely when social partners are well-organised and benefit from broad memberships (OECD (2018[35]). This allows social dialogue and collective bargaining to be widespread at the firm-level and social partners to be representative also at higher levels (e.g. sector, country).

The discussion below focuses on two aspects of collective bargaining that have received considerable attention in the discussion on productivity: i) the degree decentralisation of collective bargaining systems, which refers the scope for negotiations at the firm-level, for reallocation and innovation; ii) the degree of wage co‑ordination across collective wage agreements for macroeconomic performance and international competitiveness. It also discusses how collective bargaining can help to enhance a fair sharing of the burden of inflation between firms and workers.

Decentralised collective bargaining has often been linked with better productivity performance (OECD, 2019[36]). Decentralised systems can take two different forms. Collective bargaining may take place predominantly at the firm-level, as in “fully or largely decentralised systems” (e.g. Central and Eastern Europea countries as well as OECD countries outside Europe). While this typically provides more flexibility to firms and may support productivity, it tends to be associated with low and declining collective bargaining coverage. Alternatively, decentralisation can take place within sector-level bargaining by allowing substantial scope for further negotiation at the firm-level (upwards and downwards), as in “organised decentralised systems” (e.g. Nordic countries, Germany and the Netherlands). This also provides some flexibility to firms but does not result in lower collective bargaining coverage. In centralised systems, sector-level agreements do not leave (significant) scope for deviations downward at the firm-level (the terms of conditions can only be more favourable). While following the global financial crisis, Spain introduced more decentralisation in its system of sector-level bargaining, this has been partially reversed by the latest labour market reform of 2021 (see Box 3.3).

Until 2012, collective bargaining in Spain was largely centralised. Collective bargaining took predominantly place at the sector-level through either nation-wide or regional agreements. Firm-level agreements were rare and could only be used to top up sector-level agreements (favourability principle).

In 2012, a controversial labour market reform was undertaken, without the support of the social partners, to embark on a process of organised decentralisation of collective bargaining by allowing firm-level agreements to deviate downwards from higher-order agreements and introducing opt out clauses. Moreover, the validity of collective bargaining agreements beyond their formal end date in the absence of a new agreement was reduced to one year (ultra‑activity). The hope was that by providing more wage flexibility this would promote labour market resilience and support a job-rich recovery from the global financial crisis (OECD, 2014[37]). It is not clear to what extent these expectations have materialised. While the reform does not appear to have led to a significant increase in the use of firm-level agreements, possibly due to the absence of recognised worker representatives in most firms, the use of opt-out clauses was relatively common among firms (about 20% in 2019), particularly large firms and firms in the hospitality and arts sectors (OECD, 2021[38]). While the latter may have enhanced the alignment of wages and productivity across firms, it may also have weakened sector-level bargaining and have contributed to the decoupling of wage from productivity growth (see Chapter 2).

In a major labour market reform in 2021, based on a broad-based agreement between the social partners, these changes were partially reversed by restoring the principle of favourability with respect to base pay, allowances and bonuses and bringing back ultra‑activity. The reform also specified that in the case of sub-contracting the sector-level collective agreement of the activity in question prevails. However, some room to derogate from sector-level agreements was preserved as working time and other non-wage working conditions continue to be governed by the principle of favourability of firm-level agreements and the use of opt out clauses – arguably the key element of the 2012 reform – was not affected. Apart from increasing the centralisation of collective bargaining, an important aim of the reform was to strengthen bargaining position of trade unions and in doing so, promote a broader sharing of productivity gains.

The importance of decentralisation for productivity mainly resides in its ability to provide wage flexibility to firms. This can help to enhance the allocation of resources across firms that differ in their productivity. Indeed, in a frictional labour market, wage differences between firms tend to reflect differences in productivity and act as an allocative device by providing incentives for workers to move to more productive firms.8 Wage flexibility can also contribute to the adaptability of firms to changes in business conditions (including idiosyncratic shocks). As a result, average firm wages in decentralised systems tend to be more strongly aligned with differences in productivity across firms and over time (Berlinghieri, Criscuolo and Blancenay, 2019[39]; OECD, 2021[4]). Other reasons why decentralised collective bargaining may be associated with better productivity performance are that it requires the presence of worker representatives within the firm, which also enables social dialogue in the workplace, and that it tends to be associated with a higher prevalence of performance pay (see Box 3.4)

Empirically, it is difficult to analyse the importance of decentralised collective bargaining systems for productivity. However, there is some indication that countries with more decentralised collective bargaining systems – including those with organised decentralised systems – tend to have better productivity outcomes (OECD, 2019[36]; OECD, 2018[2]). Garnero et al. (2020[40]) study the effects of firm-level bargaining on wages and productivity in Belgium, whose collective bargaining system shares several features with the Spanish one.9 They show that firm bargaining increases both wage costs and productivity (with respect to sector-level agreements). In the case of Belgium, the productivity premium associated with firm-level agreements is smaller than the corresponding wage premium. This suggests that firm-level agreements help to redistribute income from capital to wages, particularly when product market competition is low and the rents to be shared between workers and firms are relatively high.

The empirical evidence on social dialogue and collective bargaining in the workplace tentatively suggests either no or small positive net effects on firm productivity, with considerable heterogeneity across workplaces, industries and countries – e.g. Hirsch (2004[41]), Addison (2016[42]), Doucouliagos et al. (2018[43]). The effects are likely to be more positive the better the quality of labour relations (Krueger and Mas, 2004[44]; OECD, 2016[45]), the higher the degree of product market competition (Freeman and Medoff, 1984[34])and when collective worker representation in the workplace is present (OECD, 2018[35]). It may also help if the voice and monopoly channels are clearly separated as is the case in dual systems that combine sector‑level collective bargaining with works councils in the workplace (Marsden, 2015[46]; Freeman and Lazear, 1995[47]).

The 2021 labour market reform moved towards more centralised collective bargaining, restoring the principle of favourability with respect to base pay, allowances and bonuses. This means that firm-level agreements can no longer deviate downwards from high-order collective agreements with respect to pay. The practical importance of this may be modest since firm-level agreements remain relatively rare and, overall, its use does not appear to have significantly increased since the reform of 2012 when favourability was removed (although this may be different in specific sectors and companies, particularly in multi-service companies). This may be because firm-level agreements require having a trade union or recognised worker representative in the firm which is not always the case. At the same time, some room to derogate from sector-level agreements was preserved as non-wage working conditions continued to be under the principle of favourability of firm-level agreements and the use of opt out clauses – arguably the key element of the 2012 reform – was not affected. Given the alleged importance of decentralised collective bargaining and social dialogue in the workplace for productivity, an ex post assessment of the impact of the recent labour market reform would be useful.

Collective bargaining systems that leave scope for firms to tailor the conditions set in higher-level agreements tend to be associated with higher productivity growth. In other words, some degree of flexibility at the firm level is required to ensure productivity growth. However, a pre‑condition for this to happen is to have representative forms of worker representation at the firm-level, including in SMEs.10

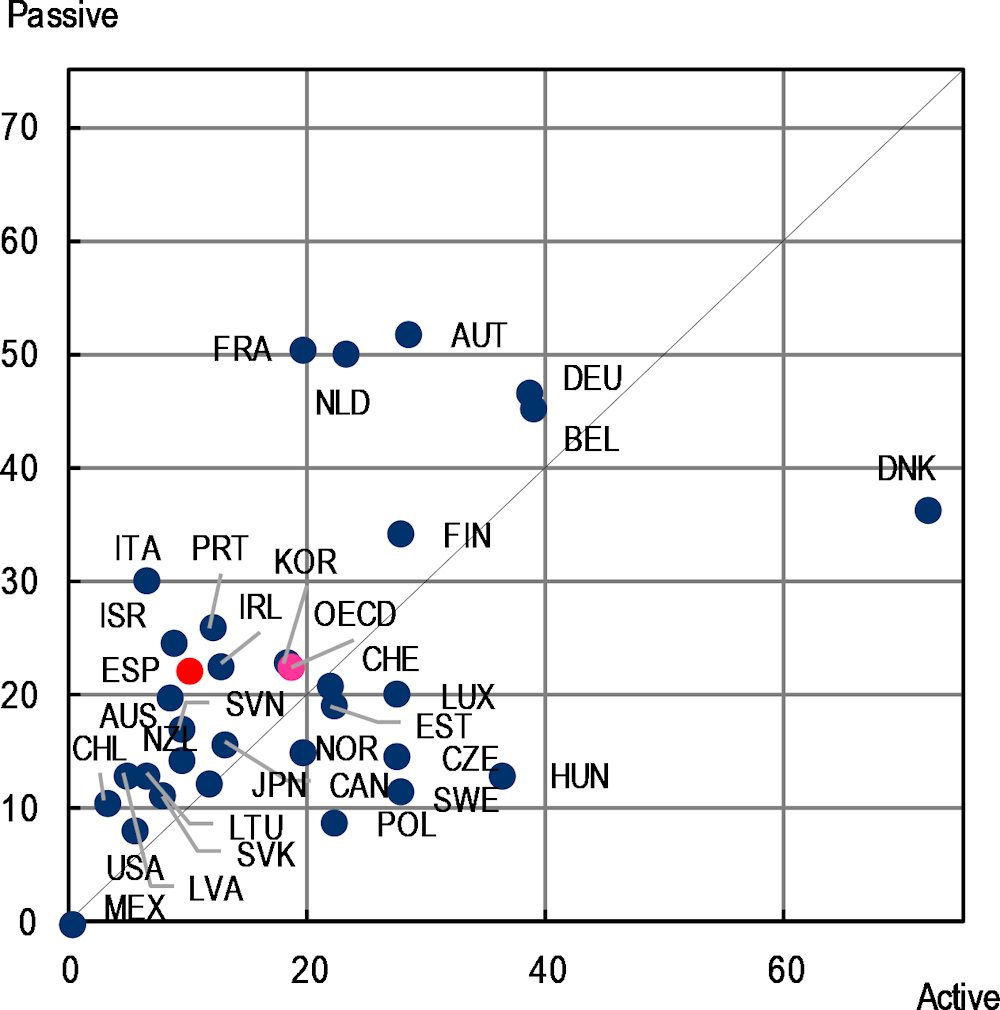

There are large differences in the degree of workplace representation across countries (Figure 3.5). Interestingly, the coverage of firm-level representation is not particularly high in EU countries where firm-level bargaining dominates, although institutions of workers representation are indispensable pillars of collective bargaining in single‑employer systems. Worker representation at the firm-level tends to be relatively high in multi-level bargaining systems, where sectoral bargaining is complemented by firm-level bargaining levels (notably in the Nordic countries, Germany or the Netherlands). By contrast, firm-level representation is low in countries characterised by sector-level bargaining with only limited bargaining at the firm-level, such as Greece or Portugal (OECD, 2019[36]). In Spain, workplace representation is about 60%, lower than in most other countries with multi-level bargaining, but higher than the EU average. In order to support social dialogue and organised decentralisation, local representation of workers in firms could be promoted further, particularly in SMEs.

Employees represented at workplace by trade union, works council or similar body as a percentage of employees

Source: OECD calculations based on the European Working Conditions Telephone Survey 2021.

To extend social dialogue to all segments of the economy, some governments have tried to promote social dialogue in SMEs. For instance, in Italy, the government in 2017 increased tax incentives to promote negotiations on performance‑related pay and welfare provisions at the firm level with the stated aim of extending firm-level bargaining to medium and small firms and strengthen the link between productivity and wages at the firm level (D’Amuri and Nizzi, 2017[48]). The evidence discussed in Box 3.4 suggests that this may have contributed to increased labour productivity at the firm level.

Performance pay can positively contribute to labour productivity (Lazear, 2000[49]). In principle, performance pay can help to attract more capable employees, encourage higher effort and quality of work, increase investment in employee training, reduce turnover and absenteeism, and improve teamwork and co‑operation. Moreover, performance pay also provides wage flexibility in firms, which may be important in countries where flexibility in base pay and employment is limited (Stokes et al., 2017[50]). However, performance pay also can have drawbacks, such as the incentive to skimp on quality and other difficult to observe aspects of performance. Pay based on individual performance may also weaken incentives for co‑operation. Empirical studies suggest that performance pay is usually associated with improved employee productivity (Damiani, Pompei and Ricci, 2022[51]).

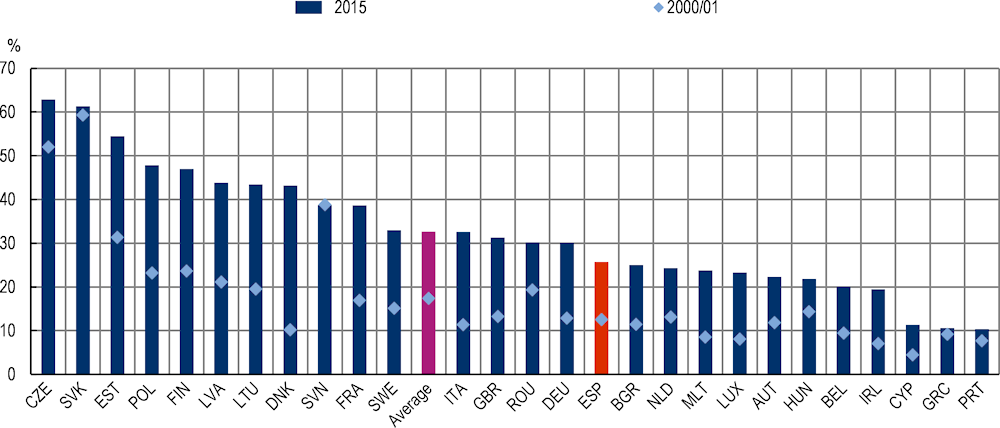

In almost all EU countries, the use of performance pay has increased in recent last decades (Figure 3.6). This has gone hand-in-hand with a decline in the coverage of collective pay agreements. Trade unions have often been reluctant to agree on the use of performance pay as they undermine the goal of more uniform and egalitarian pay policies. In fact, Zwysen (2021[52]) find that in firms where employee representation is present, performance pay is more equally divided. The use of performance pay also tends to be more prevalent in countries in which collective bargaining coverage is low or it is more decentralised.

Like in most other EU countries, the share of workers receiving some form of performance pay in Spain doubled from 13 to 26% during the period 2000 to 2015. However, the use of performance pay remains below the EU average (32.6%) and below nearby countries such as France (38.6%) and Italy (32.6%). The increased use in performance pay reflects the growing use of bonuses linked to individual performance, that of the team or the firm as a whole. By contrast, the share of workers who receive their entire salary based on their own performance pay has declined.

The restoration in the 2021 reform of the principle of favourability with respect to bonuses might slow the increasing trend in the use of performance pay and a specific monitoring could be put in place. In addition, the Spanish Government can promote the use of bonuses through information dissemination and advice on best practices as well as by providing direct fiscal incentives. Italy introduced a tax break for performance pay in 2015. The evidence shows that this increased labour productivity (Damiani, Pompei and Ricci, 2022[51]).

Percentage of employment, 2000/01‑2015

Note: The figure shows the share of any type of performance pay (financial participation, team performance, individual performance, piece‑rate) over time by country.

Source: Zwysen (2021[52]), Performance pay across Europe.

The effective co‑ordination of negotiated wages across bargaining units can help to enhance macroeconomic performance, including productivity. First, wage co‑ordination can help align wages with productivity at the aggregate level, consistent with full employment, similar to centralised bargaining (OECD, 2006[53]; Aidt and Tzannatos, 2008[54]). When unemployment is high, the main focus tends to be on wage moderation. In the context of high price inflation and labour shortages that characterises most OECD countries, co‑ordination may also support stronger wage growth, depending on the way it is done. Second, wage co‑ordination can play an important role in promoting labour market resilience by facilitating adjustments in wages and working time in response to macroeconomic shocks and thereby mitigate the unemployment impact of recessions (OECD, 2012[55]; OECD, 2017[56]). Third, wage co‑ordination can help to promote international competitiveness and balanced growth by ensuring that wages remain well aligned with productivity in exporting sectors while preventing wages in other sectors, notably non-tradables, from diverging too much and undermining international competitiveness.11 Fourth, wage co‑ordination necessarily implies some degree of wage compression across sectors and this, in combination with wage moderation, could strengthen incentives for investment in sectors that are highly profitable and support aggregate productivity growth (Barth, Moene and Willumsen, 2014[57]).12

Wage co‑ordination takes different forms in different countries. Co‑ordination is strongest when it is based on strict statutory controls (state‑imposed co‑ordination). This is the case in Belgium where wages are indexed to increases in living costs but capped by an explicit wage norm based on wage developments in neighbouring countries.13 In Nordic countries, as well as Austria, Germany and the Netherlands, a lead sector sets the wage norm, usually the manufacturing sector, and others follow (pattern bargaining). (Fougère, Gautier and Roux, 2018[58])14 In several other countries, peak-level organisations set guidelines that should be followed when bargaining at lower levels (peak-level bargaining). The way wage co‑ordination is organised could have important implications for the way it affects macroeconomic performance, including productivity. For example, pattern bargaining is more likely to be associated with wage moderation even when inflation is high, whereas this is less obvious in the case of peak-level bargaining.

In Spain, wage co‑ordination tends to be relatively weak. While peak-level organisations play an important role in developing shared responses to key challenges, their role in wage co‑ordination across industries is generally limited. Wages are more strongly aligned with productivity across sectors than in countries where wage co‑ordination is important (OECD, 2019[36]). Guidelines for wage‑setting are not binding and have little impact in practice due to the fragmented nature of employer and employee organisations, the low quality of labour relations and the lack of trust between the social partners. Whether measured in terms of the number of days lost due to strikes, the perceived quality of labour relations by senior executives or the degree of trust by the population in trade unions, Spain is well below the OECD average (OECD, 2019[36]). That said, with the revaluation of the statutory minimum wage, the minimum wage is likely to have become a more important reference point for wage negotiations, potentially increasing the effective degree of wage co‑ordination between sectors (similar to France).

The sudden and surprise increase in inflation since the second half of 2021 represents a new and significant challenge for collective bargaining systems in all OECD countries. Negotiated real wages have plummeted in all OECD countries where data are available (OECD, 2023[6]). Several factors can explain why negotiated nominal wages, on average, have not managed to keep up with inflation. Most importantly, the staggered and rather infrequent nature of wage agreements implies that negotiated wages do not adjust immediately to unexpected price inflation.

Spain is one of the few OECD countries where collective agreements can include indexation clauses Table 3.3). According to the Bank of Spain (Banco de España, 2022[59]), in 2022 among the workers covered by a collective agreement, 45% had their negotiated wages indexed to inflation, up from 17% on average in 2014‑21, but still lower than at the beginning of the 2000s, when 70% of workers with a collective agreement had such clause. Collective agreements are typically indexed to headline inflation, which includes energy prices. Most workers are covered by annual indexation clauses, but in some cases, there are multi-year indexation clauses. In this case, possible wage adjustments would be determined based on how inflation behaves over the full term of the collective agreement (which can help smoothing the impact of a temporary spike in inflation). Most indexation clauses (75%) include caps, which limit the extent to which inflation is reflected into higher wages.

Wage indexation ensures that employees’ salaries keep pace with the cost of living, which can help maintain their purchasing power and provide a sense of security. Additionally, it can help reduce conflicts between employers and employees over wage increases. In 2022, there were relatively few strikes in Spain, in comparison with the historical pattern as well as other OECD countries (OECD, 2023[6]). However, wage indexation can lead to higher labour costs for employers, which can negatively impact their profitability and competitiveness. Moreover, wage indexation can contribute to an inflationary spiral, where prices rise in response to wage increases. For now, it seems that nominal wage adjustments to higher inflation have not fuelled a wage‑price spiral. In Spain, like in most of other OECD countries, unit profits have increased by more than unit labour costs between 2021 and 2022 (OECD, 2023[6]). This suggests that many firms were able to increase prices by more than the increase in costs (e.g. higher energy prices, wages), contributing to domestic price pressures. It also means, as mentioned above, that there is some room for profits to absorb further adjustments in wages – at least for the most vulnerable workers – without generating significant price pressures or resulting in a fall in labour demand.

|

Country |

Inflation-indexed (or other indicator) pay scales |

Formula |

Automatic correction |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Belgium |

Yes, in all sectors. |

“Health index”, i.e. past CPI excluding alcohol and tobacco and petrol but including heating fuel, gas, and electricity |

No |

|

Germany |

Yes, but only in few sectors |

The agreement is renegotiated if inflation exceeds a specific rate. |

No |

|

Italy |

Yes, in all sectors |

Forecast HICP index without imported energy goods. |

Yes, both upwards and (but rarely or never applied) downwards |

|

Luxembourg |

Yes, in all sectors |

Past CPI |

No |

|

Netherlands |

Yes, but only about 5% of the agreements |

Past CPI in period t‑1 |

n.a. |

|

Spain |

Yes, but only in some sectors |

No general rule, but usually CPI in past |

Yes, but only upwards (if realised inflation is higher than the indicator of reference) with a maximum cap. |

|

Switzerland |

Yes, but only in few sectors |

It varies depending on the agreement |

Yes, but only upwards (if realised inflation is higher than the indicator of reference) |

Note: n.a.: information not available.

Source: OECD Questionnaire on recent measures to deal with inflation pressure on wages (February 2023).

As discussed in the OECD Jobs Strategy of 2018, the involvement of the social partners is essential for building consensus, maintaining social peace, and ensuring the legitimacy of policy decisions (OECD, 2018[2]). It allows for the representation of diverse perspectives and helps to balance the interests of different stakeholders. The involvement of the social partners can also help to make policy more forward-looking. This requires identifying potential challenges and opportunities ahead of time, rather than firefighting problems when they arise. Anticipating future challenges and opportunities, finding solutions, and managing change proactively, can be achieved more easily and effectively if employers, workers and their representatives work closely together with the government in a spirit of co‑operation and mutual trust. This has been crucial for the 2021 labour market reform and the co‑ordination of collective bargaining through the social pact in May 2023. The government needs to continue supporting the efforts of social partners to reach broad and forward-looking agreements and involving them in the development and implementation of future reforms.

This is particularly relevant in times of high inflation. Blanchard and Pisani-Ferry (2022[60]) have argued that a forum in which trade unions, employers’ organisations and the government agree on how to share the burden of inflation would likely allow a fairer outcome and lower risk of second-round inflation (e.g. a pass-through of inflationary shocks through wages on prices, thereby triggering a price‑wage spiral), making the job of monetary policy easier. Tripartite agreements, including on wages, were relatively common in the heydays of collective bargaining, but they are now very rare. However, the 2022 tripartite agreement on wages and competitiveness in Portugal as well as the May 2023 bipartite agreement in Spain show how social dialogue can help ensuring a fair share of the costs of high inflation and promote broadly shared productivity gains more generally.15

Job security provisions, whether in the form of employment protection or job retention schemes, can have important implications for broadly shared productivity growth. They can contribute to stronger productivity growth by strengthening incentives for the accumulation and preservation of firm-specific human capital in the workplace by promoting long-term employer-employee relationships and the use of high-performance work and management practices. However, they can also undermine productivity growth. By reducing the tendency of firms to adjust employment in line with changing business conditions and weakening the incentives of workers to move to more productive firms, they may undermine efficiency-enhancing job reallocation across firms. Evidence for OECD countries suggests that strict employment protection may also strengthen incentives for the use of flexible work arrangements, resulting in labour market duality. While a limited use of flexible work arrangements can support labour market efficiency by enhancing the matching process between workers and firms, an excessive use risks undermining incentives for on-the‑job learning and hence productivity growth. From a productivity perspective, it is therefore crucial that job security provisions strike the right balance between supporting job reallocation across firms and providing incentives for learning and innovation.

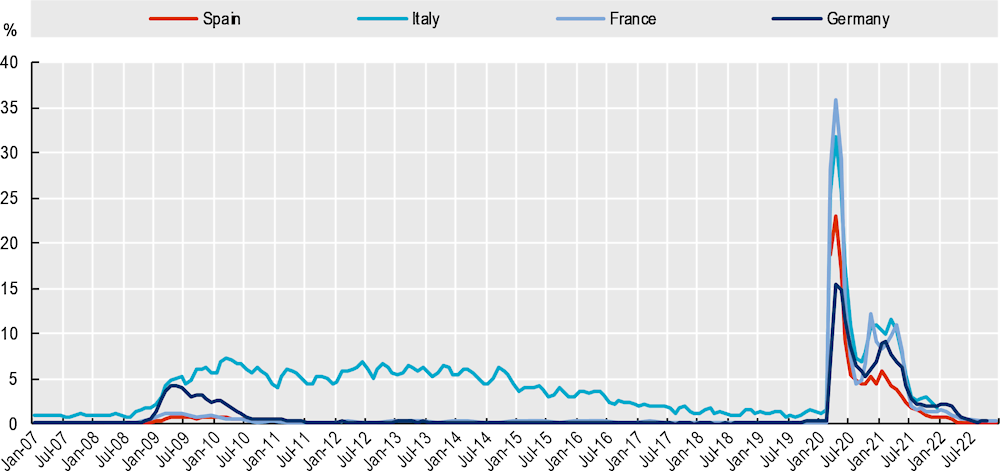

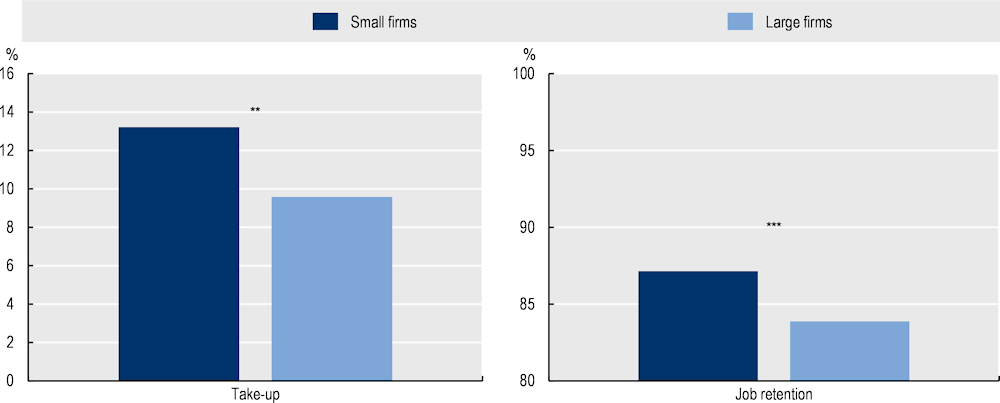

The main insight of this section is that the recent labour market reform of 2021 significantly reduced labour duality and supported labour market resilience through the enhanced design of job retention support (ERTE). More specifically, by restricting the use of temporary contracts, there has been a remarkable shift from temporary contracts to permanent contracts, without any apparent effects on overall employment so far. While these initial outcomes are encouraging, the increase in the use of permanent contracts has to some extent taken the form of intermittent open-ended contracts, which provide more job security than temporary contracts, but not necessarily more income security, since working hours vary, depending on the length of the period of activity and the season, within the limits established in the applicable sectoral collective agreement. The massive use of job retention support during the COVID‑19 crisis has prevented a surge in unemployment and stands in sharp contrast with the experience during the global financial crisis when the use of job retention support was negligeable, and unemployment increased massively. The 2021 labour market reform builds on the recent experience with ERTE during the COVID‑19 crisis by defining the parameters of the permanent scheme and introducing an innovative mechanism for scaling up support in emergency situations (the so-called RED mechanism).

Employment protection legislation defines the rules that govern the hiring and firing of workers. It is generally justified by the need to protect workers against unfair behaviour on the part of their employers and the need to induce employers to internalise the negative consequences of dismissals on society in terms of higher expenditures on unemployment benefits and the destruction of human capital following job loss and joblessness (Pissarides, 2010[61]). This sub-section starts by benchmarking employment protection rules for permanent and temporary contracts in Spain before the recent labour market reform, then proceeds by discussing the 2021 labour market reform and its effects and concludes with some considerations for the future.

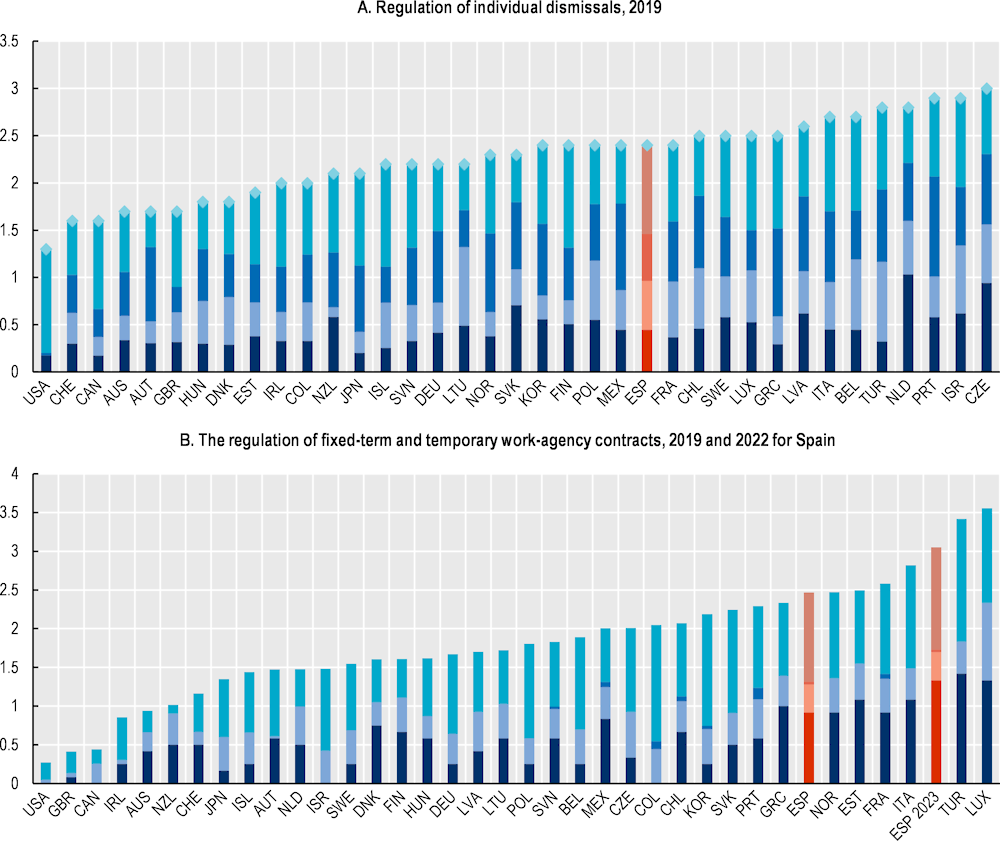

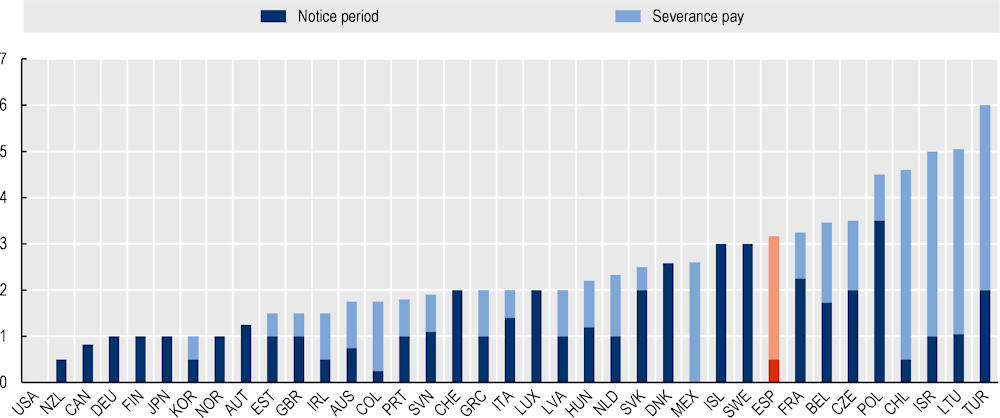

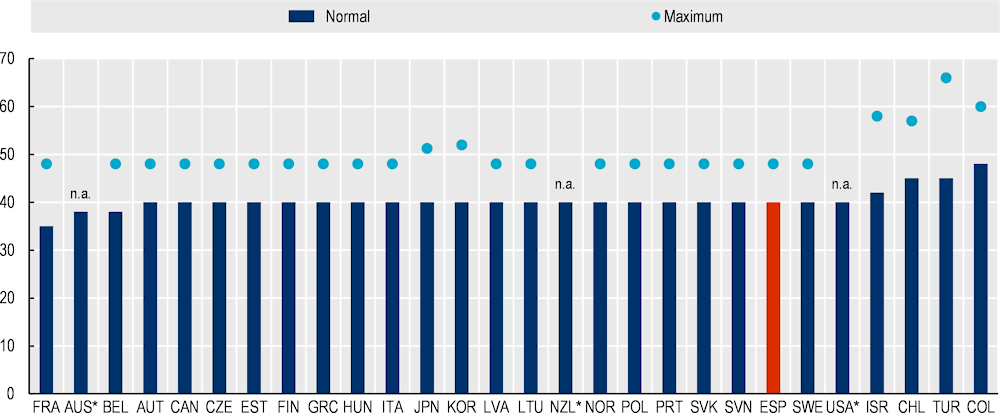

According to the OECD employment protection index of the stringency of individual dismissals of workers on open-ended contracts, Spain is among the top third of countries where regulation is the strictest (Figure 3.7, Panel A). This mainly reflects the high level of severance pay that is due in the case of fair dismissal and the strict enforcement of unfair dismissal regulation. The latter relates to provisions that limit the scope for challenging dismissals in court or which facilitate the termination of employment contracts by mutual consent. Procedural inconveniences for employers engaging in a dismissal process, such as notification and consultation requirements, do not stand out as being particularly strict. Similarly, the framework for unfair dismissals, which relates to the permissible grounds for fair dismissals and the repercussions for the employer if a dismissal is found to be unfair, is not particularly strict. The rules for collective dismissal are broadly similar as those for individual dismissal.16

Similarly, according to the OECD employment protection index on the stringency of regulations on the use of temporary contracts, Spain was among the top fifth of countries with the strictest rules, even before the recent labour market reform (Panel B). The regulation of fixed-term and temporary work-agency contracts (temporary contracts in short) relates to the circumstances where they can be used, the number of times they can be renewed and their cumulative duration. In Spain, fixed-term contracts can only be used for “objective” reasons, such as a temporary task or a temporary increase in workload, while in most other countries, no justification is required for hiring a worker on a temporary contract or specific exemptions apply. The maximum cumulative duration of fixed-term contracts varies according to the reasons for using them from 90 days per year in the case of foreseeable temporary increases in workload to 6 months in the case of an unforeseeable increase in workload or 12 months if specified in the sectoral collective agreement or in the case of training contract (2 years maximum in case of contrato de formación en alternancia which combines training with work). Fixed-term contracts can usually be renewed only once within the maximum cumulative duration. Similar rules apply to temporary work-agency employment.

Index, 0‑6, 2019

Note: Range of indicator scores: 0‑6. Panel A: The four broad categories of dismissal regulation determine with equal weight the aggregate score. Panel B: The aggregate indicators assign the same weight to hiring regulation for fixed-term contracts, hiring regulation for temporary work agency contracts and termination of fixed-term contracts. The two indicators for terminating fixed-term contracts before and at the end date contribute in equal shares to the indicator.

Source: OECD EPL database.

Strict employment protection for permanent workers has sometimes raised concerns about its implications for aggregate productivity growth for two reasons. First, strict employment protection tends to reduce job mobility among permanent workers, with potentially adverse consequences for the efficiency of job reallocation between firms that differ in their productivity. Employment protection of permanent workers not just reduces job dismissals as envisioned, but also incentives for hiring workers on permanent contracts, and hence overall labour market fluidity (Micco and Pagés, 2006[62]; OECD, 2010[63]; Bartelsman, Haltiwanger and Scarpetta, 2013[64]).17 While the reduction in worker flows is intended to some extent, if it is reduced beyond its optimal level, it can have adverse implications for aggregate productivity growth (Bassanini, Nunziata and Venn, 2009[65]), by undermining the efficiency of job reallocation across firms (Andrews and Cingano, 2014[66]; Bottasso, Conti and Sulis, 2017[67]). Second, employment protection rules may influence the use of temporary contracts. Evidence for OECD countries suggests that strict rules for permanent workers can strengthen incentives for the use of temporary contracts (OECD, 2018[2]).18

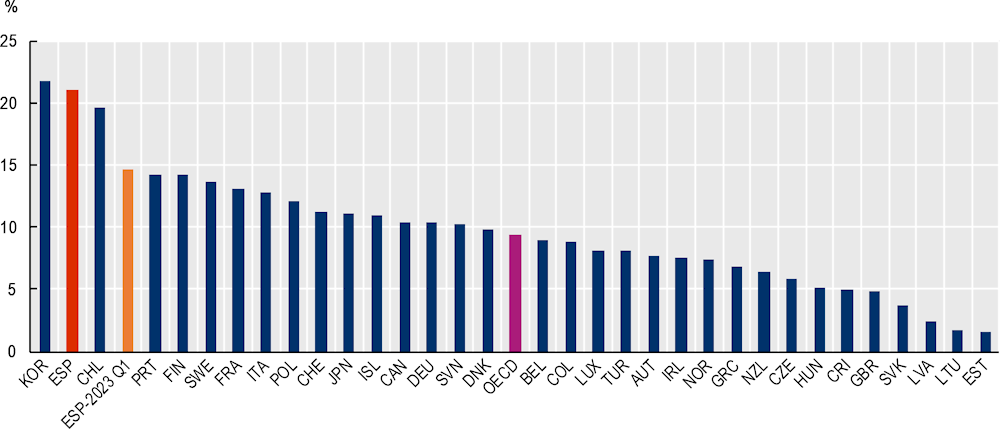

The strict regulation of fixed-term contracts has not always been found to have a significant impact on their use. Indeed, before the labour market reform of 2021, Spain had relatively strict rules for the use of temporary contracts, but its incidence in employment was the second highest in the OECD (Figure 3.8). This most likely reflects non-compliance. This is an issue in many OECD countries since workers typically face weak incentives to challenge the inappropriate use of temporary contracts in court, given their weak position in the labour market and the short duration of their contract.19 That said, a very high use of temporary contracts raises important concerns about productivity growth as well as inclusiveness. While in principle temporary contracts can help promote labour market efficiency by making permanent jobs more accessible for unemployed workers, when their use is too widespread, as was the case in Spain before the 2021 reform, they no longer provide effective stepping stones to permanent jobs but rather tend to replace them, with adverse consequences for average job quality, skill development and productivity growth (OECD, 2018[2]).

Percentage of total employment, 2021 for all countries and Q1 2023 for Spain

Source: OECD Employment database, http://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TEMP_D and Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

To tackle labour market duality and revive productivity growth, a more balanced approach to employment protection is needed. In principle, this could be achieved through a number of different approaches (OECD, 2018[2]):

Restricting further the use of temporary contracts (see Box 3.5);

Easing the employment protection of permanent workers;

Aligning termination costs across contracts.

The 2021 labour market reform in Spain represents an important step in this direction by restricting the use of temporary contracts, while preserving the changes that were made as part of the 2012 labour market reform that eased the employment protection of permanent workers.

In recent years, a number of OECD countries have conducted labour market reforms that restrict the use of temporary contracts by limiting the circumstance in which they can be used and their maximum cumulative duration.

These reforms in many cases reversed labour market reforms in the 1980s and 1990s that sought to tackle persistent unemployment by liberalising the use of temporary contracts. Today’s evidence suggests that these reforms did little to promote overall employment or reduce unemployment, but instead resulted in the substitutions of permanent contracts by temporary ones (Kahn, 2010[68]; Daruich, Di Addario and Saggio, 2023[69]), with adverse consequences for job quality, inclusiveness and productivity growth. Consequently, one would expect the reforms that go in the opposite direction by restricting the use of temporary contracts to have positive outcomes in terms of labour market performance.

Examples of countries that restricted the scope for use temporary contracts:

Denmark introduced the obligation to make temporary employment conditional on objective reasons in 2013.

Italy introduced the obligation to provide a rationale when using a fixed-term contract for more than 12 months in 2018. The reform reversed the 2014 Poletti decree that abolished the obligation to provide a rationale when using fixed-term contracts and allowed for five successive renewals.

Slovenia outlawed the recruitment of different workers in the same position using temporary contracts for more than two years in 2013. In addition, a maximum limit was imposed on the use of temporary agency work in a firm.

Examples of countries that introduced legal limits for the cumulative duration of temporary contracts:

Poland reduced the maximum cumulative duration of temporary contracts to 33 months in 2016.

Germany reduced the maximum cumulative duration of temporary work agency assignments to 18 months in 2017.

Slovak Republic reduced the maximum cumulative duration for temporary work agency assignments to 2 years in 2015.

The Netherlands reduced the maximum cumulative duration of successive temporary contracts from three to two years in 2014.

Japan made it possible for workers who have had a fixed-term contract for at least five years to have their contract automatically converted into a permanent one in 2013.

Source: OECD (2020[70]), “Recent trends in employment protection legislation”, in OECD Employment Outlook 2020: Worker Security and the COVID‑19 Crisis, https://doi.org/10.1787/af9c7d85-en.

In an effort to reduce contractual segmentation, the 2021 labour market reform restricted the use of temporary contracts. From its entry into force in February 2022, permanent contracts became the default contract, while the use of temporary contracts has been strictly limited to temporary staff needs. More specifically, i) the very flexible and widely used contract for work and service (Contrato por obra o servicio) has been abolished, ii) the duration of the existing training contracts (contrato de trabajo en prácticas and contrato para la formación y el aprendizaje), which had a maximum cumulative duration of 2 and 3 years respectively, has been reduced to one year (contrato para la obtención de la práctica profesional) and two years respectively (contrato de formación en alternancia); and iii) the requirements to justify the temporary nature of needs have been strengthened. As a result, Spain has become the country with the third strictest rules in the OECD (Figure 3.7).

Another important part of the reform, but one that is not reflected the OECD Employment Protection indicators, is the increased scope for the use of open-ended intermittent contracts (Contrato fijo-discontinuo). Whereas before the reform their use was strictly limited to seasonal work, the reform extended its scope to all intermittent activities, temporary agency work, and contract work. Consequently, open-ended intermittent contracts can be used for many of the activities that were previously conducted with temporary contracts. In principle, such contracts are preferable to workers since they provide more stability and a stronger protection against the risk of dismissal. That said, their implications for income security are not entirely clear. While the law requires that open-ended intermittent contracts specify in advance the expected period and hours of work, it does not guarantee a minimum amount of activity. The regulation of a minimum guaranteed number of working hours and several other aspects of these contracts is left to collective agreements.20

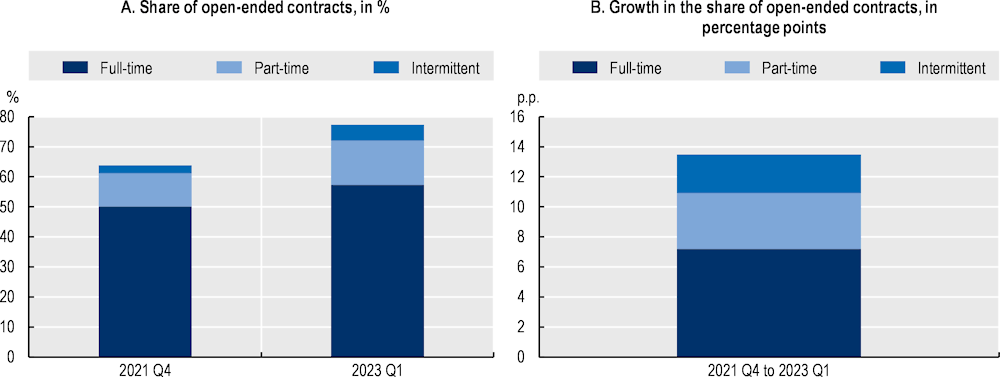

At first glance, the reform seems to have achieved its objective, as it has been followed by a sharp reduction in temporary employment and a surge in permanent employment, particularly among young people (Figure 3.9). The reduction in the incidence of temporary work is sizeable. It declined from more than 20% in 2021, more than double the OECD average, to a less than 15% in Q1 2023, but still about 1.5 times the OECD average. Since the reform has only just been implemented, it is too early to say anything about its implications for productivity growth in the medium and longer term. Consequently, the effects of the reform will need to be monitored closely.

Recent evidence on a similar reform in Portugal indicates a limited impact on employment and a reduction in the incidence of temporary employment (Cahuc et al., 2023[71]) – with positive consequences for job security and job quality, but also for productivity (OECD, 2018[2]; OECD, 2020[70]).21 One reason is that limited opportunities for career advancement in the firm for people in temporary jobs tend to reduce their commitment to the job and thus their incentives to invest in firm-specific knowledge and skills.

Number of permanent and temporary employees (thousands), difference compared to Q4 2021

It should be noted, however, that the rise in permanent employment at least to some extent reflects the increased use of open-ended intermittent contracts (Muñoz de Bustillo Llorente, 2022[72]). The share of open-ended contracts increased from 64% to 77% on average between 2021Q4 and 2023Q1, with about 20% of this increase due to open-ended intermittent contracts (Figure 3.10). Its incidence in employment doubled, from 2.7% in 2021Q4 to 5.3% in 2023Q1, but still remains modest in proportion to the total number of jobs.

As mentioned above, such contracts offer more employment stability than temporary contracts, but not necessarily more income security. Although working hours are known in advance, they might vary depending on the length of the period of activity and the season, within the limits of the applicable sectoral collective agreement. There is also a potential risk that it could increase unemployment benefit expenditures since suspended workers do not need to actively look for another job in contrast to unemployed workers whose temporary contract expired or was terminated. Depending on how firms will use open-ended intermitted contracts, there may be a need to regulate the minimum number of hours in a given period for all sectors, which for now is mostly left to sectoral collective agreements, and for measures that require firms to internalise some of the fiscal costs incurred by the use of these contracts. For example, employers’ social security contributions could be linked to a firm’s past use of unemployment benefits by workers on open-ended intermittent contracts on their payroll. See Box 3.7 for a description of experience‑rated unemployment benefits systems in France and the United States.

Promoting transitions from open-ended intermittent contracts (as well as from temporary contracts) to regular open-ended contracts is particularly important. The reform already pays considerable attention to this issue by obliging companies to inform workers on intermittent contracts and their legal representatives of any vacancies for regular open-ended contracts. In addition, workers on intermittent contracts have priority access to vocational training opportunities in the workplace during periods of inactivity. These actions are very much welcomed, and indeed it may be possible to go further. For example, it may be possible to give workers on open-ended intermittent contracts access to career guidance and develop flexible courses that can be combined with variable work schedules.

Source: Spanish Ministry of Inclusion, Social Security and Migration.

While the initial effects of the recent labour market reform are promising, it may be possible to go further by reforming the employment protection of workers on permanent contracts. Such reforms are notoriously difficult to implement given their large distributional implications. Indeed, this is the reason why many countries in the 1980s and 1990s, including Spain, opted for partial labour market reforms that liberalised the use of temporary contracts. However, this does not mean that the regulation of permanent contracts cannot be enhanced to provide a better balance between flexibility for firms and security for workers. The Italian Jobs Act provides a nice example. Amongst others, this introduced severance pay for economic dismissal which previously did not exist, increasing the de jure level of employment protection. This was expected to reduce incentives to challenge dismissals in court, reducing legal uncertainty for employers. Consequently, workers were better protected against the risk of economic dismissal, while at the same time, the effective dismissal costs for firms were reduced by reducing legal uncertainty. The remainder of this section considers a number of reforms for the regulation of open-ended contracts that do not reduce the effective protection of workers but may help to reduce its effective costs for employers. The next sub-section discusses how internal flexibility, as provided by job retention support, can help to share the costs of economic downturns more evenly across the workforce.

A first possibility could be to make it easier to terminate permanent contracts by mutual consent, as it is rather difficult in Spain in comparison with other OECD countries. Unlike in many other OECD countries, workers who end their contract by mutual consent are not entitled to unemployment benefits in Spain and cannot easily access public employment services related to job-search assistance, career counselling and training. This could reduce the willingness to terminate contracts by mutual consent and increase uncertainty about the cost of dismissal for firms. A number of countries have established specific pre-termination resolution mechanisms to secure job termination for employers (OECD, 2013[73]). For example, France introduced a formalised scheme of termination by mutual agreement in 2008 (rupture conventionnelle). The agreement must be approved by the Labour Ministry and is subject to a cooling-off period, after which the employee is entitled to standard severance pay (or more) and unemployment benefits. Strengthening activation services can further help to alleviate concerns that workers who become unemployed do not actively engage in job search (Box 3.6).

A second possibility could be to adjust the balance between the length of notice period and other aspects of employment protection such as severance pay (Figure 3.11). Severance pay for permanent workers is relatively high in Spain in international comparison. It amounts to 20 days of pay per year service up to a maximum of 12 months.22 At the same time, notification periods are relatively short. Compared with severance pay, notice periods tend to be less costly for employers since the worker is in principle required to continue working during the notice period whereas it can be more protective for workers, by allowing the public employment services to intervene before the dismissal takes place, thereby facilitating the transition to another job (OECD, 2018[74]). Spain may therefore be able to strike a better balance between the costs and benefits of employment protection for regular workers by increasing the length of notification periods, while adjusting other aspects of employment protection to keep the overall stringency of employment protection constant (OECD, 2020[70]). This would also increase the scope for offering employment services to workers during the notice period before the contract ends. It has been shown that this can be particularly effective in reducing the costs of job displacement (Box 3.6).

Workers on permanent contracts, four years of job tenure, measured in months of pay after dismissal notice, 2019