This section examines whether the Palestinian Authority has put in place processes for monitoring and reviewing the existing stock of regulations and laws, including how it undertakes reforms to improve regulation in specific areas or sectors to reduce administrative burdens or evaluate the overall effectiveness of regulation.

Rule of Law and Governance in the Palestinian Authority

10. Management of the Existing Stock of Regulations

Abstract

The statute book is uniquely complex and fragmented, containing laws issued under different regimes dating back to the era of the Ottoman Empire. This in turn means that is difficult for regulated subjects to understand and navigate existing rules. This section therefore recommends that policies and mechanisms need to be established to ensure that this stock of legislation undergoes some form of ex post reviews over time, to ensure that it remains fit for purpose.

The existing body of law has been issued under several political regimes (see Chapter 1 “Political context”). The law is a blend of Islamic customary law, Urf, and the principles of Islamic Shari’a (the main source of legislation), the stock of legislation applied or enacted under the Ottoman Empire (1516-1917), British Mandate Law (1917-1948), Jordanian legislation applied to the West Bank and Egyptian legislation applied to the Gaza Strip (1948-1967) and, of course, legislation enacted by the Palestinian Authority since 1994. This legacy creates a significant challenge when drafting new legislation. In addition, the political split between Gaza and the West Bank with the different legal traditions has far-reaching implications for the legislative process and impedes consolidation efforts for the Palestinian legal system. (OECD, 2011[1])

The PA has not yet put in place a comprehensive set of policies and mechanisms to ensure that the existing laws and regulations on the statute book will be monitored and reviewed as to their effectiveness. There are occasional, limited, elements of ex post review requirements in its current legislative drafting and consultation guidelines, and some forms of ex post evaluation are being implemented by certain line ministries on an ad hoc basis (Ministry of Justice of the Palestinian Authority, 2018[2]). However, ex post evaluation does not take place systematically across line ministries, and civil servants lack guidance and methodologies, as well as sufficient training, to carry such reviews out.

Ex post evaluation

OECD best practice suggests that regulations should be periodically reviewed to ensure that they remain fit for purpose. Regulations that are efficient today may become inefficient tomorrow, due to social, economic, or technological change. Most OECD countries have enormous stocks of regulation and administrative formalities that have accumulated over years or decades without adequate review and revision. The accumulated costs of this in economic or social terms can be high.

Ex post evaluations complete the “regulatory cycle” that begins with ex ante assessment of proposals and proceeds to implementation and administration. The importance of using ex post evaluations to assess the ongoing worth of regulations is recognised in the OECD Recommendation on Regulatory Policy and Governance [OECD/LEGAL/0390] (see Box 10.1). It states that Member governments should “conduct systematic reviews of the stock of regulation … to ensure that regulations remain up to date, ... cost effective and consistent, and deliver the intended policy objectives” [OECD/LEGAL/0390].

Box 10.1. The fifth recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance

Conduct systematic programme reviews of the stock of significant regulation against clearly defined policy goals, including consideration of costs and benefits, to ensure that regulations remain up to date, cost justified, cost-effective and consistent and delivers the intended policy objectives.

The methods of Regulatory Impact Analysis should be integrated in programmes for the review and revision of existing regulations. These programmes should include an explicit objective to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the regulations, including better design of regulatory instruments and to lessen regulatory costs for citizens and businesses as part of a policy to promote economic efficiency.

Reviews should preferably be scheduled to assess all significant regulation systematically over time, enhance consistency and coherence of the regulatory stock, and reduce unnecessary regulatory burdens and ensure that significant potential unintended consequences of regulation are identified. Priority should be given to identifying ineffective regulation and regulation with significant economic impacts on users and/or impact on risk management. The use of a permanent review mechanism should be considered for inclusion in rules, such as through review clauses in primary laws and sunsetting of subordinate legislation.

Systems for reviews should assess progress toward achieving coherence with economic, social and environmental policies.

Programmes of administrative simplification should include measurements of the aggregate burdens of regulation where feasible and consider the use of explicit targets as a means to lessen administrative burdens for citizens and businesses. Qualitative methods should complement the quantitative methods to better target efforts.

Employ the opportunities of information technology and one-stop shops for licences, permits, and other procedural requirements to make service delivery more streamlined and user-focused.

Review the means by which citizens and businesses are required to interact with government to satisfy regulatory requirements and reduce transaction costs.

Source (OECD, 2012[3]).

The OECD has defined three overarching principles for instituting ex post evaluation with public administrations (OECD, 2020[4]):

Regulatory policy frameworks should explicitly incorporate ex post evaluations as an integral and permanent part of the regulatory cycle;

A sound system for the ex post evaluation of regulation would ensure comprehensive coverage of the regulatory stock over time while "quality controlling" key reviews and monitoring the system's operations as a whole; and

Reviews should include an evidence-based assessment of the actual outcomes from regulations against their rationales and objectives, note any lessons and make recommendations to address any performance deficiencies.

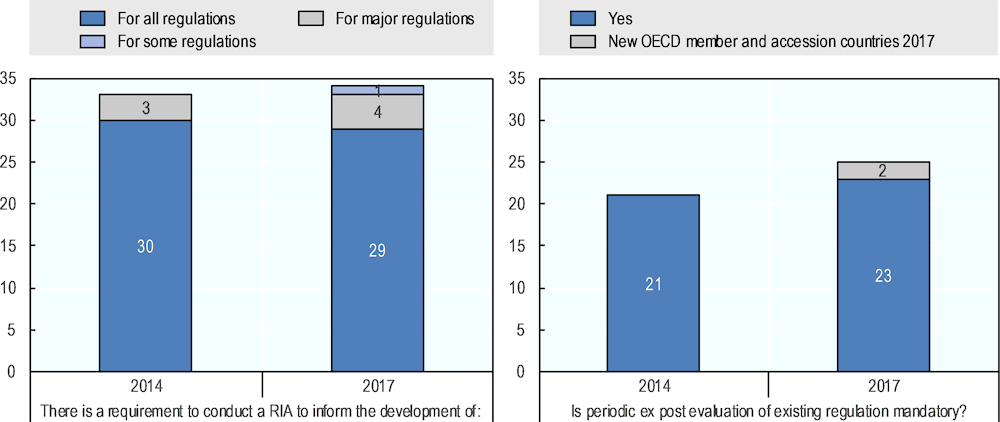

However, based on the Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance surveys, systems for the ex post evaluation of regulation remain less developed across OECD Member countries than for other components of the regulatory cycle, particularly ex ante RIA, with fewer countries having formalised arrangements. For example, some form of ex post evaluation was recorded as obligatory by only 60% of Member countries, compared to around 90% for ex ante RIA (OECD, 2020[4]).

Figure 10.1. Requirements to conduct RIA and ex post evaluation

Note: Data for OECD countries is based on the 34 countries that were OECD Member countries in 2014 and the European Union. Data on new OECD Member and accession countries 2017 includes Colombia, Costa Rica, Latvia and Lithuania.

Source: Indicators of Regulatory Policy and Governance Surveys 2014 and 2017, http://oe.cd/ireg.

A “portfolio” of approaches to the ex post evaluation of regulation will generally be needed (see Box 10.2). Most countries have adopted more than one of these approaches utilising forms of review within each category listed below, which draw upon a taxonomy developed by the Australian Productivity Commission. Practical ways to embed ex post evaluation in a country’s policy system include sunset clauses to require governments to review a regulation a certain amount of time after it has been promulgated, scheduled reviews that look at whole policy frameworks for different areas and specialised standing bodies that have a mandate to review regulations and to make recommendations for improvement.

Box 10.2. Approaches to regulatory reviews

A “portfolio” of approaches to the ex post evaluation of regulation will generally be needed. In broad terms, such approaches range from programmed reviews, to reviews initiated on an ad hoc basis, or as part of ongoing “management” processes. Most countries have adopted more than one of these approaches utilising forms of review within each category listed below, which draw upon a taxonomy developed by the Australian Productivity Commission.

“Programmed” reviews

For regulations or laws with potentially important impacts on society or the economy, particularly those containing innovative features or where their effectiveness is uncertain, it is desirable to embed review requirements in the legislative/regulatory framework itself.

Sunset requirements provide a useful “failsafe” mechanism to ensure the entire stock of subordinate regulation remains fit for purpose over time.

Post-implementation reviews within a shorter timeframe (1 to 2 years) are relevant to situations in which an ex ante regulatory assessment was deemed inadequate (by an oversight body for example) or a regulation was introduced despite known deficiencies or downside risks.

Ad hoc reviews

Public “stocktakes” of regulation provide a periodic opportunity to identify current problem areas in specific sectors or the economy as a whole.

Stocktake-type reviews can also employ a screening criterion or principle to focus on specific performance issues or impacts of concern.

“In depth” public reviews are appropriate for major regulatory regimes that involve significant complexities or interactions, or that are highly contentious, or both.

“Benchmarking” of regulation can be a useful mechanism for identifying improvements based on comparisons with jurisdictions having similar policy frameworks and objectives.

Ongoing stock management

There need to be mechanisms in place that enable “on the ground” learnings within enforcement bodies about a regulation’s performance to be conveyed as a matter of course to areas of government with policy responsibility.

Regulatory offset rules (such as one-in one-out) and Burden Reduction Targets or quotas need to include a requirement that regulations slated for removal, if still “active”, first undergo some form of assessment as to their worth.

Review methods should themselves be reviewed periodically to ensure that they too remain fit for purpose.

Source: (OECD, 2020[4])

The review of the regulatory stock as part of the ex post review process is particularly important since it can help reduce administrative burdens for citizens and businesses as well as improve public sector efficiency. Countries can use a checklist to decide whether certain regulations should be kept, scrapped or modified. Such a checklist was used for example in Croatia (see Box 10.3) and a template was developed by the OECD to provide countries with guidance in developing and implementing better regulation (see Box 10.4).

Box 10.3. Regulatory guillotine in Croatia

To improve the regulatory environment in Croatia, a short-term statute law revision (regulatory guillotine) project, known by its Croatian acronym as HITROREZ, was launched in 2006. The Government initiative co-founded by USAID and UNDP aimed at counting, reviewing and streamlining business regulations in Croatia.

The regulatory guillotine was conducted in the following phases:

First, the government asked all ministries and agencies to prepare inventory lists of their regulations by a certain date. Each administrative body in co-operation with stakeholders from the private sector prepared a complete list of all regulations with an impact on businesses and people and submitted the list to the Special Unit of HITROREZ together with all associated forms. The process was overseen by a central body.

Then, Government authorities reviewed each business regulation and its associated forms and fees based on standardised criteria and a questionnaire. Each business regulation was assessed with a recommended action: keep, change or cancel. Those identified as unnecessary, outdated or illegal were excluded from the list.

The special Unit for HITROREZ reviewed each business regulation taking into account feedback from government authorities and the business community, as well as comments from consultations with other relevant stakeholders. The Unit developed final recommendations and presented it to the government of Croatia. As a result, 27% of business regulations were eliminated and 30% were simplified.

Source: (OECD, 2019[5])

Box 10.4. 1995 OECD Recommendation on Improving the Quality of Government Regulation

In 1995, the OECD adopted the Recommendation on Improving the Quality of Government Regulation [OECD/LEGAL/0278] to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of government regulation by upgrading the legal and factual basis for regulations, clarifying options, assisting officials in reaching better decisions, establishing more orderly and predictable decision processes, identifying existing regulations that are outdated or unnecessary, and making government actions more transparent. In order to provide guidance for countries in developing and implementing better regulation, a Reference Checklist for Regulatory Decision-making was issued containing the following ten questions:

Q1. Is the problem correctly defined?

Q2. Is government action justified?

Q3. Is regulation the best form of government action?

Q4. Is there a legal basis for regulation?

Q5. What is the appropriate level (or levels) of government for this action?

Q6. Do the benefits of regulation justify the costs?

Q7. Is the distribution of effects across society transparent?

Q8. Is the regulation clear, consistent, comprehensible, and accessible to users?

Q9. Have all interested parties had the opportunity to present their views?

Q10. How will compliance be achieved?

Source: (OECD, 1995[6])

Current procedures

The PA has placed consolidating the body of law as one of its strategic policy objectives. Under Pillar 1 of the “National Policy Agenda 2017-22: Putting Citizens First” (also see the sub-section “Vision for Regulatory Policy”), the PA has committed to consolidating and modernising PA’s body of law to ensure consistency with international obligations (Pillar 1, National Policy 3). The document states:

“Our national unity will be further advanced by establishing a modern, coherent body of law reflecting our international commitments and replacing the unwieldy mix of Palestinian, Jordanian, Egyptian and Ottoman laws that derives from colonisation and occupation.”

However, the PA has not yet put in place strong formal requirements or guidance material to ensure that ex post evaluations are systematically carried out by line ministries. The legislative drafting guidelines (see 6.5), introduced by the Council of Ministers Resolution No. (17/174/07), state that a key step in the legislative process is “follow-up and evaluation: the party responsible for oversight must evaluate the outcomes and compare them with performance indicators to determine the extent of success of the solution mechanisms in addressing the problem and resolving it.

Box 10.5. The Legislative Drafting Guidelines – ex post evaluation

The legislative drafting guidelines were prepared in 2018 by a working group led by the Ministry of Justice in cooperation with EUPOL COPPS. They build on earlier versions of the guidelines developed in 2000 and evaluated by the OECD in 2011. The legislative drafting guidelines have been approved by the Council of Ministers pursuant to Resolution No. (17/174/07) of 2017 on 10/10/2017 and are considered binding.

Part One:

Follow up and evaluation: To enable us to know the extent of the correct action taken to solve the problem, the party responsible for oversight must evaluate the outcomes and compare them with performance indicators to determine the extent of success of the solution mechanisms in addressing the problem and resolving it. This however, requires compliance with certain criteria that identify the points of strength and weakness in the legislation after implementing it and determining the procedures that should be reconsidered. The following are among the mechanisms that contribute to the performance of an accurate evaluation:

Preparation of periodical reports.

Field visits.

Obtaining the points of view of the members of the community.

Preparation of statistics and comparing them with previous statistics to determine if there is an increase or decrease in same.

Monitor the performance indicators and finding out extent of same.

To achieve a successful follow-up and accurate evaluation, we have to determine in advance during the preparation of the document the parties responsible for this, the monitoring fields, who will do the monitoring and the implementation mechanism.

In addition, the Guidelines on Public Consultation (see Box 9.2 in chapter 9) issued by the Ministry of Justice in 2018, stipulate that evaluation is a key stage in the public consultation process:

“Evaluation process: this process starts after preparing and issuing the legislation it includes follow-up, evaluation, monitoring, and revision of the drafted law after implementation. The process is initiated to measure the law’s success in arriving at the targets it was set to facilitate.”

The OECD were informed that there is a complaints department within the OoP that deals with stakeholder complaints about existing legislation. In addition, the OECD were made aware of a number of ad-hoc initiatives for reviewing legislation, undertaken by different parts of the PA.1 The focus of these reviews have mainly been on addressing any shortcomings and inconsistencies within the legislation or harmonising the legislation with international standards, as opposed a detailed evaluation of the impacts of the legislation. For example:

The Ministry of Transport have stated that regulations are reviewed in order to remove ambiguity or to harmonise the system, especially since certain regulations have become incompatible with international standards. For example, a regulation contained a provision with names of degrees of driving licenses, which had become incompatible with international classifications. This led to the amendment of the regulation in order to be compatible with those classifications.

The Diwan have stated that a review has been conducted on legislation related to women. The review examined the legislation from a number of lenses, including social, economic, educational, competitiveness, rights and obligations, and recommendations were made to the Cabinet, to amend some legislation and introduce new legislation.

There have been some initiatives from the PA to introduce e-government services, with the aim of reducing administrative burdens on people. As mentioned in the previous Section “Transparency and e-government”, some ministries, the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology in 2018 launched an online portal called "My Government" in cooperation with the Land Authority, the Ministry of Labour, and the Ministry of Transport and Communications.

However, despite the existence of these strategic policy objectives and high-level requirements, in practice, ex post evaluation is not yet systematically carried out on existing laws and regulations. There is not currently an explicit policy and guidelines for ex post evaluation in place, clearly assigning roles and responsibilities of the actors involved in the review process, or a clear set of requirements for ministries to carry out ex post evaluations for existing regulations in the Palestinian Authority .

There is also an absence of a specific methodology for ex post review, to assist with identifying priorities for reviews and identifying and measuring the impacts of regulation, including administrative burdens and wider costs and benefit to the economy, society and the environment. Reviews are presently carried out on an ad hoc basis according to the modalities of the particular regulation in question. This is very important as there are a number of different approaches that can be taken to institutionalise ex post evaluation within an administration’s policy process (see Box 10.6). It should be noted that the forthcoming OECD Good Practices Manual for the Palestinian Authority will provide selected practical guidance on how regulatory management tools can be implemented, although detailed methodological guidance will still be required (OECD, forthcoming).

Practical ways to embed ex post evaluation in a country’s policy system include sunset clauses to require governments to review a regulation a certain amount of time after it has been promulgated. For regulations or laws with potentially important impacts on society or the economy, particularly those containing innovative features or where their effectiveness is uncertain, it is desirable to embed review requirements in the legislative/regulatory framework itself. A selection of international examples of how these approaches have been embedded into government’s rule making processes is included in Box 10.6.

Box 10.6. International examples of approaches to ex post evaluation

New Zealand

In New Zealand, the Public Service Act stipulates five public service principles. One of them is “stewardship”, which explicitly includes within its scope the stewardship of all legislation administered within the public service. This “regulatory stewardship” responsibility views regulation (regulatory systems) as a set of national assets that require proactive monitoring, care and maintenance to deliver effectively over time.

Good regulatory stewardship practice includes:

Monitoring the performance and the state of the regulatory systems and of the regulatory environment, assessing the regulatory system and evaluating whether it is suitable for the regulatory objective and reporting on regulatory systems

Systematic assessment of risks and impacts of regulations prior to any changes and enabling interested parties to contribute to the design of regulations

Providing information and support to regulated parties

Providing training to regulatory personnel.

European Commission

The European Commission’s “evaluate first” principle is a key aspect of its regulatory framework. The “evaluate first” principle calls for the review of regulations before any new proposal is made in an area concerned by the foreseen regulation and that timely and relevant recommendations are given to regulators to support their decision-making. In addition, the evaluation of regulations aids the decision-making process by contributing to the design of future policies.

Source: (OECD, 2021[7])

Furthermore, there has been little attempt to date by the PA to evaluate and reduce the administrative burdens caused by the stock of regulation, despite the aforementioned attempts to introduce e-government initiatives. It appears to be particularly difficult and time consuming for external stakeholders (e.g. Small and Medium Sized Enterprises and people) to understand and navigate existing rules.

OECD best practice points to a range of initiatives that have been undertaken internationally to implement administrative simplification strategies, including attempts to quantify regulatory burdens to businesses and people through well understood methodologies such as the Standard Cost Model (SCM). Governments have also attempted to introduce more ‘bottom-up’ approaches to understanding regulatory burdens through working closely with stakeholders to identify issues of most concern to them (see Box 10.7). One-stop shops have also been introduced to many OECD countries part of broader administrative simplification strategies.2

Box 10.7. International examples of administrative burden reduction

The Netherlands carried out a study comparing regulatory burden for SME’s in the bakery sector across selected EU Member States. The evaluation compared the impact of the regulatory frameworks in the Netherlands, Lithuania, Spain and Ireland. The objective was to assess whether significant differences existed in the implementation of national and EU legislation resulting in unnecessary regulatory burdens. The review concluded that the use of exemptions and lighter-touch regulatory regimes for SME bakeries in EU laws could reduce regulatory burdens and improve their economic viability.

In Denmark, the Ministry for Business and Growth launched the Danish Business Forum in 2012 to identify and discuss the compliance and administrative burden that businesses face. The members of the forum include industry and labour organisations, businesses, as well as experts with expertise in simplification. The forum gathers 3 times a year and sends common proposals to the government on the possible avenues for regulatory simplification. These proposals are subject to a “comply or explain” approach whereby the government is obliged to either pursue the proposed initiatives or to explain why these are not pursued. As of 2016, 603 proposals had been made by the forum of which 191 were fully and 189 partially implemented. The total savings to businesses from the implementation of these simplification measures were estimated to amount to 790 million Danish crowns.

In Germany, The Federal Statistical Office was commissioned by the Federal government in 2015 to conduct surveys of individuals and companies on their subjective perception of public authorities and the body of law in specific life events. The survey exercise aims to identify measures for a more noticeable bureaucracy reduction and will be repeated every two years. The approach identified typical life events in which citizens people and companies interact with public authorities. 22 life events for individuals were selected ranging from the birth of a child to marriage, unemployment and need for long-term care. Similarly, 10 events for companies based on a company’s life cycle were selected, including business start-up, the appointment of employees, and business discontinuation. For every life event, an interactive customer-journey map was constructed displaying the typical and most important offices citizens or businesses have to contact and the procedures they have to complete to obtain the respective service.

Source: (OECD, 2020[4]), (OECD, 2016[8])

Analytical capacities for ex post evaluation

The challenge facing ministries due to understaffing and a lack of analytical resourcing has already been highlighted earlier in the report (see Section 3 “Capacities”). It logically follows that the same capacity challenges clearly exist for successfully implementing ex post evaluation. There is a lack of expertise in staff able to analyse wider social and economic impacts and carry out cost-benefit-analysis. There is also a lack of practical guidance available to civil servants, explaining the different tools and approaches to carrying out ex post evaluations. Furthermore, there are no training programmes available to civil servants on how to carry out ex post evaluations in practice. Box 10.8 provides some examples of building capacity and providing support to evaluators in OECD countries.

Box 10.8. Building capacity and providing support to evaluators

In Canada, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) Regulatory Affairs Sector initiated a number of measures to assist in building evaluation skills across federal departments and agencies, including:

the development of a core curriculum by the Canada School of Public Service, which features also a course on “Regulatory performance measurement and evaluation”;

the creation of the Centre of Regulatory Expertise (CORE), which provides technical support concerning cost-benefit analysis, risk assessment, performance measurement and evaluation of regulations; and

the establishment of the Centre of Excellence for Evaluation (CEE), which serves as a help-desk body in the planning and implementation of evaluations. This includes supporting the competent departments and agencies in the implementation and utilisation of evaluations, and helping to promote the further development of evaluation practices, not least through guidelines and manuals.

In the European Commission, in the framework of the Smart Regulation strategy, central support and co-ordination is ensured by the Secretariat-General. The latter issues guidance; provides in-house training; and organises dedicated workshops and seminars. The Secretariat-General oversees the EC’s evaluation activities and results and promotes, monitors and reports on good evaluation practice. Evaluation units are present in almost all Directorates-General. Several “evaluation networks” dedicated to specific policy areas are also at work (for instance in relation to research policy or regional policy).

Also in Switzerland, despite the fact that there is no central control body for the implementation and support of evaluation in the federal administration, experiences and expertise is shared thanks to an informal “evaluation network”. The network exists since 1995 and is directed at all persons interested in evaluation questions, and comprises around 120 members from various institutions.

Source: (OECD, 2018[9]).

Data availability and accessibility

Earlier in this report, the difficulties facing the PA regarding data availability for the assessment of regulatory impacts were discussed (see sub-section “Data availability and accessibility”) A lack of, availability of or access to relevant data significantly hampers objective and effective regulatory analyses and evidence-based decision-making.

OECD best practice states that data requirements for ex post evaluation are best considered at the time a regulation is being made, as part of wider consideration of the type of evaluation that would be most appropriate. Evaluations can fail to produce credible findings and recommendations for lack of adequate “evidence”. Standard data collections within the administration may not have the granularity or specificity needed to evaluate all relevant impacts of a regulation. (OECD, 2020[4])

Regulatory oversight

There is no body responsible for systematically supporting and controlling the quality of ex post evaluations, which is the same challenge facing RIA (see sub-section “Regulatory oversight of impact assessment”). OECD best practice states that there needs to be oversight and accountability systems within public administrations to provide ongoing assurance that significant areas of regulation will not be missed and that reviews are conducted appropriately. If regulatory agencies and their ministries are left entirely to their own devices, there is a risk that important areas of regulation will not be reviewed, or that reviews will sometimes occur too late (in response to a mishap or “crisis”) or that they will not be conducted sufficiently.

In addition, successful international best practice points to benefits in institutional arrangements that combine oversight of the processes for ex ante as well as ex post assessment. In particular, there is a connection between ex ante and ex post evaluations, with the former setting up the latter and ex post reviews being conducted in the light of ex ante assessments, as well as helping to inform further evaluations of new or amended regulation (see Box 10.9).

Box 10.9. Examples linking ex ante and ex post regulatory oversight in OECD Member countries

Austria has established the system of “Wirkungsorientierte Folgenabschätzung”, which introduces systematic requirements for both ex ante and ex post assessments, and requires major regulations to be evaluated after five years. The Federal Performance Management Office is responsible for ensuring the quality of both ex ante and ex post assessments. In its 2017 report, a regulatory proposal relating to Funding Alpine Infrastructure was highlighted as it explicitly stated that in order to assess the regulation’s actual success, impact-orientated data would be required that would allow for progress to be accurately measured. The evidence base would then be expected to form the basis of the ex post evaluation when the regulation was due for review.

The Regulatory Scrutiny Board of the European Commission conducts reviews of ex ante impact assessments, as well as selected ex post evaluations. Its 2017 annual report analysed how impact assessments and ex post evaluations were assessed when regulatory proposals were subject to an informal “upstream meeting” early in the review process with staff of the Commission’s services. It generally found that the final impact assessment result had improved where upstream meetings took place – which also tended to be in more complex regulatory areas. The same could not be said for ex post evaluations and it was queried whether the limited impact was due to the upstream meeting taking place too late in the evaluation process.

Source: (OECD, 2020[4]).

Recommendations

The PA has not yet put in place strong formal requirements or guidance material to ensure that ex post evaluations are systematically carried out by line ministries. This is despite the fact PA has set out a strategic policy objective to consolidate and modernise its statute book in the “National Policy Agenda 2017-22”. The PA has also included references to monitoring and evaluation in the legislative drafting guidelines. However, as with ex ante RIA, roles and responsibilities of the different actors who would be involved in the review process have not been clearly assigned. There is also no clarity as to when a review should be carried out.

The PA does not have a specific methodology for ex post evaluation. As a result, there is no systematic approach to ex post evaluation across the administration. Presently, any reviews are generally carried out on an ad hoc basis by line ministries, on a regulation by regulation basis, although the Diwan has informed the OECD that they have carried out a thematic review examining legislation relating to women. Line ministries do not have any guidance as to the different approaches for selecting areas of regulation for review, or how to use different tools (e.g. Cost-Benefit Analysis) to help them understand the impacts of regulations to businesses and society.

There has not been a significant effort to implement administrative simplification strategies. There have been some welcome approaches at implementing e-government initiatives, such as the “My government” online portal. However, PA has an exceptionally complex and fragmented statute book, containing laws issued under different regimes. It is also facing the unique challenge of the political split between Gaza and the West Bank, whereby the two authorities do not enact legislative acts issued by the other. This in turn means that is difficult for external stakeholders (e.g. Small and Medium Sized Enterprises and people) to understand and navigate existing rules. Consolidating and simplifying the statute book will be an ongoing, long term effort across the administration. There are numerous examples internationally of OECD Member countries who have undertaken such efforts. An international example of codification has included Greece, which has been carrying out several reforms of its regulatory framework, including the establishment of a long-term codification plan of the main regulations in 2016 and creation of an electronic portal for the access to regulations as well as simplification of law in selected areas (labour law, VAT) in 2015. (OECD, 2018[10])

A regulatory oversight mechanism to ensure that evaluations are actually carried out, and to a certain quality standard, has yet to be introduced. Ex ante RIA is facing the same challenge (see sub-section “Regulatory oversight of impact assessment”). OECD best practice suggests that there are benefits in institutional arrangements that combine oversight of the processes for ex ante as well as ex post assessment.

The PA faces significant difficulties regarding data availability for the assessment of regulatory impacts. A lack of availability to relevant data significantly hampers objective and effective regulatory analyses and evidence-based decision-making. There is also potential for greater coherence between ex ante RIA and ex post evaluation requirements. OECD Best Practice states that ex ante RIAs should establish monitoring indicators and data gathering to enable ex post evaluation to take place (OECD, 2020[11]).

Recommendation 10.1 - Engage with stakeholders to identify the most burdensome areas of existing legislation.

Identify the sectors of the economy and society with the most burdensome regulations. Such an exercise would also help generate some momentum behind simplifying the stock of regulations. It should focus ex post evaluation efforts on priority areas, which is crucial as OECD experience has shown that the “Pareto principle” can be applied to regulatory burdens – 20% of regulations usually cause 80% of the administrative burden. (OECD, 2010[12]). The PA could run a series of workshops to identify together with stakeholders major policy areas and sectors with the corresponding ministries. This will later enable the PA to implement pilot in-depth reviews of these problematic areas of regulation (see Recommendation 5.2). Beyond looking at regulations in isolation, regular review of regulations and policy measures in key policy areas and sectors that are identified to be of particular economic or social importance can have very high returns.

Draw upon the e-hub portal currently under development by the Council of Ministers (see the section “Transparency and e-government” to support the identification of the most salient regulatory burdens. This portal could provide an open channel for complaints and suggestions concerning existing legislation from the public.

Ensure the coordination and monitoring of the programme’s implementation by the General Secretariat of the Council of Ministers. However, line ministries should also have a prominent role in running the programmes of engagement with their key stakeholders, for the respective areas of regulation they oversee.

Recommendation 10.2 - Develop a methodology and guidance for ex post evaluation of existing legislation and run pilot tests with ministries.

Prepare a comprehensive and clear guidance and methodology for ex post evaluations. This methodology should introduce a requirement to assess laws and regulations sometime after their implementation to ensure they meet their objectives. It should clarify when an ex post evaluation needs to be carried out (e.g. x number of years after a regulation is published), as well as the processes to be followed and the different tools that ministries can employ to assess impacts. The different types of ex post evaluation are set out in Box 10.2. The new methodology should be tested through a series of pilots, focused upon the areas of the economy identified in Recommendation 5.1. These pilots should further be supported by clear guidelines.

Train staff in ministries to conduct evaluations or ensure the quality of evaluations contracted out to academics and to use evaluations of existing regulations before amending regulations. All evaluations should be published online in a central place that is easily accessible to the general public. Resources for evaluation could be focused on high-impact regulations to avoid evaluation fatigue.

Establish ex post evaluation working groups could be established containing representatives from the key line ministries, as well as Diwan, to support implementation of the new methodology in practice, for initiatives of significant importance, and leverage policy integration and structurally sharing multi-disciplinary expertise.

Ensure the coordination and monitoring of the programme’s implementation by the General Secretariat of the Council of Ministers. The Secretariat could co-ordinate ex post evaluation efforts to identify priority areas for review together with stakeholders within and outside the administration. In a first step, the body could support ministries in evaluating key policy areas.

Designate an oversight body to carry out quality control of ex post evaluations, in addition to ex ante RIAs.

Recommendation 10.3 - Carry out a comprehensive review of the stock of regulations.

Prepare a long term plan with the aim of consolidating and simplifying the exceptionally complex and fragmented Palestinian statute book - a key strategic policy objective under Pillar 1, National Policy 3 of the “National Policy Agenda 2017-22”. The plan could look to undertake a process of consolidation or codification of the statute book, with a view to achieving clearer language, increased capacity for compliance amongst the regulated population. An example of such an attempt to improve the regulatory environment can be seen in Croatia, where until the early 2000s, the public administration had almost no experience with assessing the consequences of its actions on businesses and people. The first attempt to improve the regulatory environment in Croatia followed in 2006 with the regulatory guillotine project HITROREZ (see Box 10.3).

Ensure the coordination and monitoring of the programme’s implementation, as a cross-administration initiative, by the General Secretariat of the Council of Ministers. However, it will be critical to the success of the programme that line ministries have ownership in their areas of regulation.

Ask line ministries to compile a database of the existing regulations within each of their respective areas of policy as a starting point. Following this, ministries can undertake a relatively simple exercise by scrutinising their databases of regulation and utilise a set of simple questions or checklist to decide whether certain regulations should be kept, scrapped or modified.

References

[2] Ministry of Justice of the Palestinian Authority (2018), “The Legislative Drafting Guidelines”.

[7] OECD (2021), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2021, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/38b0fdb1-en.

[13] OECD (2020), One-Stop Shops for Citizens and Business, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b0b0924e-en.

[11] OECD (2020), Regulatory Impact Assessment, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/7a9638cb-en.

[4] OECD (2020), Reviewing the Stock of Regulation, OECD Best Practice Principles for Regulatory Policy, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/1a8f33bc-en.

[5] OECD (2019), Regulatory Policy in Croatia: Implementation is Key, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b1c44413-en.

[10] OECD (2018), OECD Regulatory Policy Outlook 2018, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264303072-en.

[9] OECD (2018), Regulatory Policy in Slovenia: Oversight Matters, OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264291690-en.

[8] OECD (2016), Pilot database on stakeholder engagement practices in regulatory policy, First set of practice examples, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://www.oecd.org/gov/regulatory-policy/pilot-database-on-stakeholder-engagement-practices.htm.

[3] OECD (2012), Recommendation of the Council on Regulatory Policy and Governance, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0390 (accessed on 7 November 2018).

[1] OECD (2011), Regulatory Consultation in the Palestinian Authority, https://www.oecd.org/mena/governance/50402841.pdf (accessed on 26 March 2021).

[12] OECD (2010), Why Is Administrative Simplification So Complicated?: Looking beyond 2010, Cutting Red Tape, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264089754-en.

[6] OECD (1995), Recommendation of the Council on Improving the Quality of Government Regulation, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0278.

Notes

← 1. This information regarding examples of types of reviews was provided to the OECD by the PA in response to a questionnaire on regulatory policy.

← 2. For more information on one-stop shops, see the OECD Best Practice Principles for One‑Stop Shops for Citizens and Business. (OECD, 2020[13])