This section focuses on Norway’s digital performance and marries it with a more in-depth discussion of the policies that underpin each dimension of the Framework. Norway requires policy decisions grounded in solid evidence to shape its digital future. Overall, the economic outlook for Norway is characterised by high inflation and weakening domestic demand, with growth expected to slow in 2024 (OECD, 2023[24]). Norway’s strong reliance on natural resources such as oil and gas have led to an underinvestment in innovation. The country’s inward orientation has also limited the effects of productivity-related technology spillovers from foreign direct investment (FDI) and trade. With regard to the digital aspects of the economy and society, Norway performs well overall, albeit with some areas in which it could catch up.

Shaping Norway’s Digital Future

Section 3. Situating norway’s digital performance and outlook in its policy context

The digital growth outlook for Norway

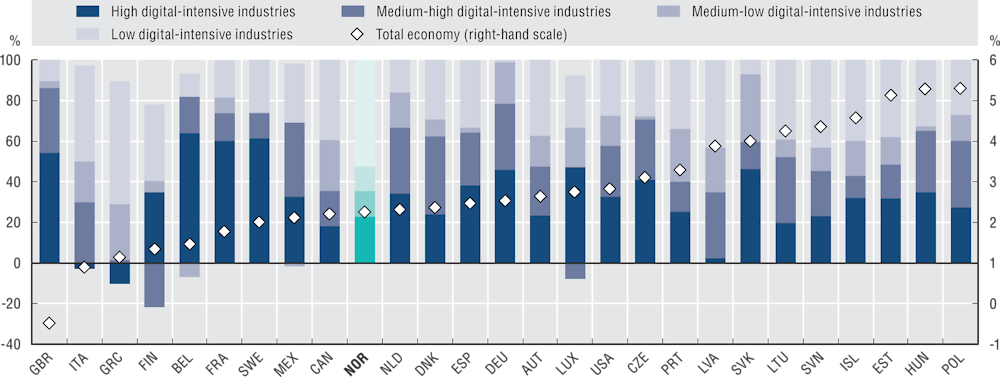

Measuring the size of the digital economy is complex, in part because digital technologies and data are everywhere. The contribution of high and medium-high digital-intensive sectors to value-added growth is a proxy for the contribution of the “digital economy” to growth (Figure 12)1. Digital-intensive sectors are characterised by high and medium-high digital intensity.2 In Norway, these sectors account for 35% of value-added growth, well behind Sweden (74%), Denmark (62%) and Iceland (43%), though above Finland (13%). With its resource-rich economy, primary products such as oil, gas and fisheries contribute heavily to Norway’s gross domestic product (GDP). The relatively low contribution of highly digital sectors to growth relative to its neighbours suggests further opportunities to benefit from productivity-related spillovers from highly digitalised sectors.

Figure 12. Contribution of digital-intensive sectors to value-added growth

Real value-added growth as a percentage of annual growth in real value added, chain-linked volumes, 2018 (or latest available)

Note: The growth contributions shown for each country are calculated in absolute terms and add up to 100% (or sometimes 99.9% due to rounding).

Source: OECD (2024[89]), OECD Going Digital Toolkit, based on the OECD Structural Analysis (STAN) database, http://oe.cd/stan, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/indicator/08.

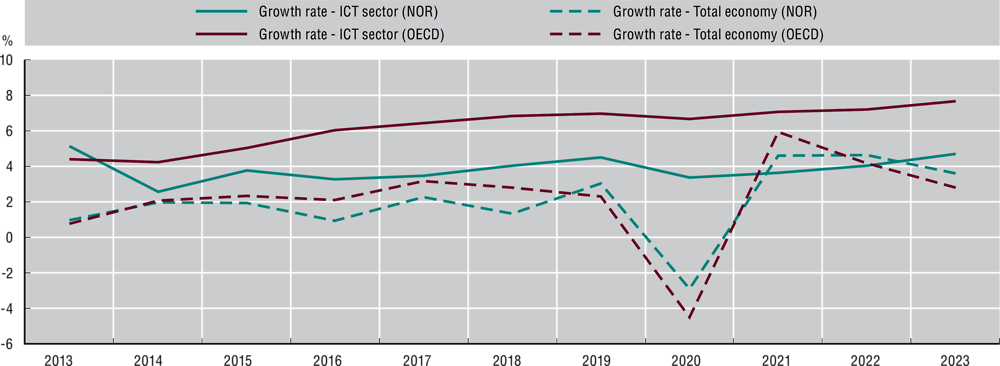

While all economic sectors are somewhat digitalised, the information and communication technology (ICT) sector remains at the core of digital transformation, and critical to further digital innovation. However, sectoral growth rates in official statistics have a considerable lag. New estimates of ICT sector growth in real time provide insights into its performance, which will in turn help inform policy decisions that affect this sector in the future. The estimates are based on an artificial neural network model that leverages online search data (OECD, 2024[25]).

Figure 133 shows the evolution of ICT sector growth and total economic growth in Norway and the OECD over the past decade. While ICT growth in Norway has been consistently positive during this period – even in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic – it has been well below the OECD average. In 2023, ICT sector growth in Norway was estimated at 4.7%, below the OECD average of 7.6%.

Figure 13. The growth outlook for Norway

ICT sector and total economy, 2013-23

Source: Data for 2013-18 come from the OECD STAN Database http://oe.cd/stan; nowcast estimates of the growth rate of the ICT sector for 2019-23 come from OECD (2024[25]); and nowcast estimates of total economic growth for January 2019 to April 2023 come from the OECD Weekly Tracker, www.oecd.org/economy/weekly-tracker-of-gdp-growth.

Norway’s digital performance through the lens of the Framework

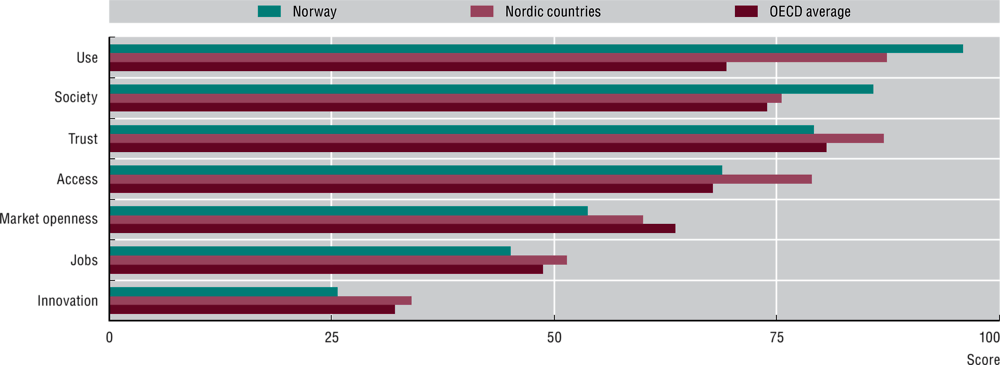

The Framework provides a useful lens to assess digital performance. The Nordic region is generally a strong digital performer, and Norway is no exception. Norway is a digital front-runner in indicators related to effective use of digital technologies and the societal dimension of digital transformation, and it outperforms the OECD and Nordic averages (Figure 14 and Figure B.1). Indeed, Norway is the best performing OECD country in select indicators in both the Use and Society dimensions, particularly in Use, where it is best in class.

Figure 14. Overview of Norway’s digital performance

By dimension of the Framework, 2023

Note: Scores express each country value as a proportion of the best performing country value, which is set equal to 100.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD (2024[95]), “Norway”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/en/countries/nor.

Norway performs strongly in Trust in digital environments and in Access to communications infrastructures, services and data. Market openness in digital business environments and Jobs fit for the digital age are the next best-performing dimensions. Indicators related to teleworking, training and low barriers to digital services show outstanding performance. At the same time, Norway has opportunities to catch up in indicators related to the number of science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) graduates, jobs in digital-intensive sectors and cross-border e-commerce. Furthermore, it clearly lags in digital Innovation, performing below the OECD average in all of that dimension’s indicators and behind the Nordic average overall.

Access to communications infrastructure, services and data

Communications infrastructures and services are the backbone of digital transformation, facilitating interactions between connected individuals, organisations and machines. Ensuring access to high-quality communication networks and services at competitive rates is essential for driving digital transformation. Demands for networks are growing as more people, things and activities go on line. Likewise, data are increasingly recognised as a foundation for digital transformation, fuelling economic activity and productivity.

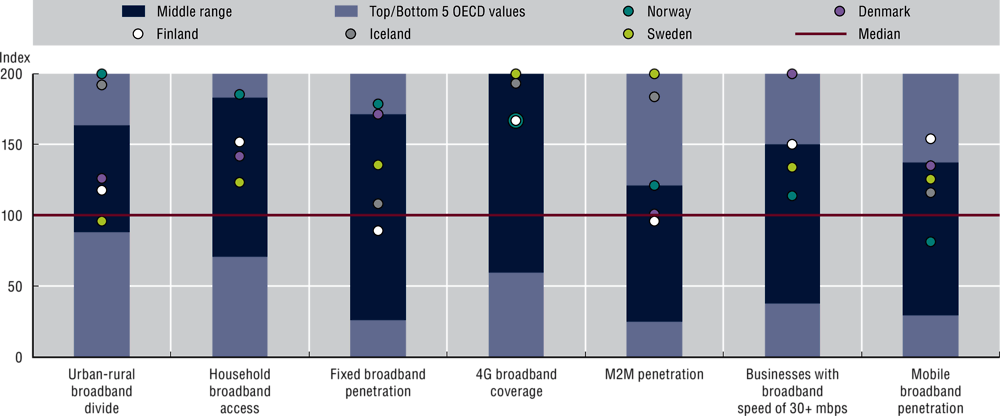

With much of Norway’s population and landmass situated north of the Arctic Circle, it is no small task to connect its citizens to essential services and the rest of society in all seasons. Moreover, while digital technologies can provide seamless connectivity, they depend on a reliable power supply and resilient physical infrastructure. Despite the geographical hurdles, Norway is within the top tier of the best performing OECD countries in some Access indicators. It is also at or above the OECD median in all but two indicators (Figure 15)4.

Figure 15. Norway’s performance in the Access dimension

Normalised index of performance relative to the OECD median (index median = 100), 2023 (or latest available)

Note: Norway’s performance is compared to the median value observed in the OECD area, i.e. the middle position among OECD countries for which data are available.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD (2024[87]), “Access”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/dimension/access.

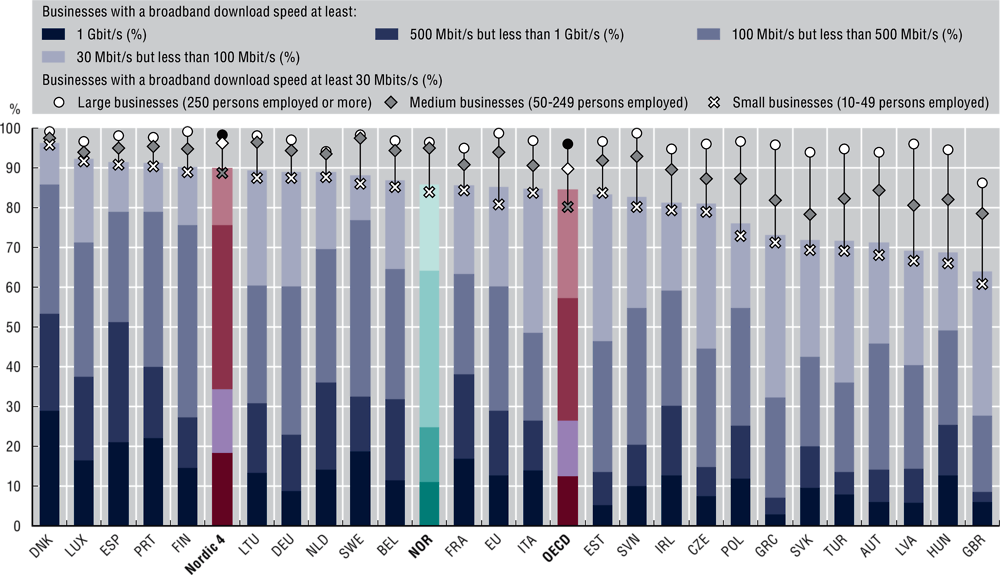

Access to communication infrastructures and services is unparalleled for a country of Norway’s size. As of 2023, fixed or mobile broadband services, with an advertised speed of at least 256 kilobits per second (Kbps), reached an impressive 99% of households in rural and large urban areas. This level of access was behind only Korea and Switzerland. Moreover, Norway consistently secures a top position in fixed broadband penetration. Since 2010, it has maintained the highest subscription rates, alongside countries like Denmark, France, the Netherlands and Switzerland (OECD, 2024[26]). The share of enterprises with a contracted broadband speed of 30 Mbps or more is 86%, close to the Nordic (87%) and OECD (84%) averages. However, there is a noticeable gap between small enterprises (83%) compared to their large (96%) and medium-sized counterparts (95%) (Figure 16)5.

Performance noticeably drops off at higher speed tiers. Norway falls below the OECD average for businesses connected to broadband services of 500 Mbps. It is also falling behind both the OECD average and the performance of other Nordic nations for businesses connected to broadband services of at least 1 gigabit per second (Gbps) (OECD, 2024[4]). These higher speed tiers are more likely to be required for digital-intensive businesses, including implementation of data-heavy technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual reality.

Figure 16. Share of businesses with broadband contracted speed of 30 Mbps or more

All businesses (excludes financial sector) with 10 employees or more, 2022

Note: Fibre covers fibre to the premises and fibre to the building.

Source: OECD (2024[4]), “Share of businesses with broadband contracted speed of 30 Mbps or more”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, based on the OECD ICT Access and Usage by Businesses Databases (https://oe.cd/dx/ict-access-usage), https://goingdigital.oecd.org/indicator/14.

Performance is mixed for the uptake and use of mobile broadband. By 2021, nearly all Norwegians were served by at least a 4G mobile network (OECD, 2024[5]), which is essential for the rollout of the Internet of Things (IoT). Machine-to-machine communication penetration – which enables applications and services based on data collected from devices and objects – has also increased rapidly in the last few years. The number of machine-to-machine SIM cards6 used in the country increased from 33 per 100 inhabitants in 2018 to 72 in 2022, although this is still below the Nordic average of 110 (OECD, 2024[27]).

Despite this performance, the share of Norwegian households with mobile broadband Internet access at home (40%) lags both the OECD average (58%) and other Nordic countries (OECD, 2024[28]). Mobile data usage in Norway (12 GB/subscription/month) exceeds the OECD average (10 GB/subscription/month). However, the next closest Nordic country (Sweden) uses over 50% more data per mobile subscription per month (19 GB) (OECD, 2024[29]). This suggests either that Norwegians tend to use less data-intensive mobile applications or that pricing or infrastructure quality is restricting more intensive use.

Norway’s policy landscape related to Access

Norway’s position as a digital front-runner is in part due to its excellent connectivity. Not surprisingly, the Access dimension is both one of the most well-funded and well-covered dimensions in Norway’s digital policy landscape. Norway’s main policy initiative in the Access dimension is “Our common digital foundation” (Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2021[30]). It sets ambitious targets such as universal coverage of 100 Mbps broadband and the expansion of gigabit coverage to certain sectors such as public administration, education, traffic hubs and emergency services by the end of 2025. This initiative also set an objective for 2025 to provide 5G coverage to all areas covered by 4G as of 2020.

Given more than a quarter of Norway’s population live in remote areas (compared to an OECD average of just under 10%) (OECD, 2024[31]), policies to ensure equitable Internet access for all citizens have particular salience. To achieve this, the Norwegian government has two distinct yet linked policy initiatives. First, bidders in the 2021 spectrum auction that agreed to provide broadband services of 100 Mbps in rural areas were eligible for an optional discount of up to NOK 560 million. Second, as a complement to the discount, the broadband support scheme provides an annual state aid grant to connect premises not covered by commercial deployment. In 2024, the government approved NOK 400 million (about EUR 35 million) for this broadband support.

Beyond investment, connectivity and regional development, the Norwegian government has initiatives to increase the security and resilience of the telecommunications network. While power outages in Norway are relatively rare, severe weather events such as heavy snowfall and high winds are the main cause of disruption. Research shows communications network outages are the primary concern of Norwegian households in the event of electricity disruption (Wethal, 2023[32]). Given the government has emphasised preparations for the digital and green transitions, action in this area is sensible; climate change will likely cause more disruptions in future. In 2024, the Norwegian government will spend NOK 188 million to improve security and resilience in the Norwegian electronic communications networks. Among other actions, this includes power backup on mobile stations and improved resilience in vulnerable regions.

For Norway, the challenge in the Access dimension is less about getting ahead than staying ahead. In future, achieving universal coverage of 100 Mbps broadband in such a challenging geography for communications infrastructure and delivering the gigabit speeds needed will be much more demanding. Wireless technology cannot reliably deliver such speeds, especially over the long distances required to serve Norway’s rural communities. Getting the next generation of connectivity policies right will require maintaining a thriving and competitive commercial market. At the same time, Norway needs sufficient investment to ensure Norway’s rural north is not left behind for access to next generation communication networks.

Effective use of digital technologies and data

The power and potential of digital technologies and data for individuals, governments and firms hinge on their effective use. Promoting adoption, diffusion and proficient use of advanced digital tools is crucial, especially among small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Policies aimed at training people to use digital technologies effectively, and at promoting the adoption and diffusion of advanced digital tools, can boost productivity growth in firms and enhance the reach and quality of public services.

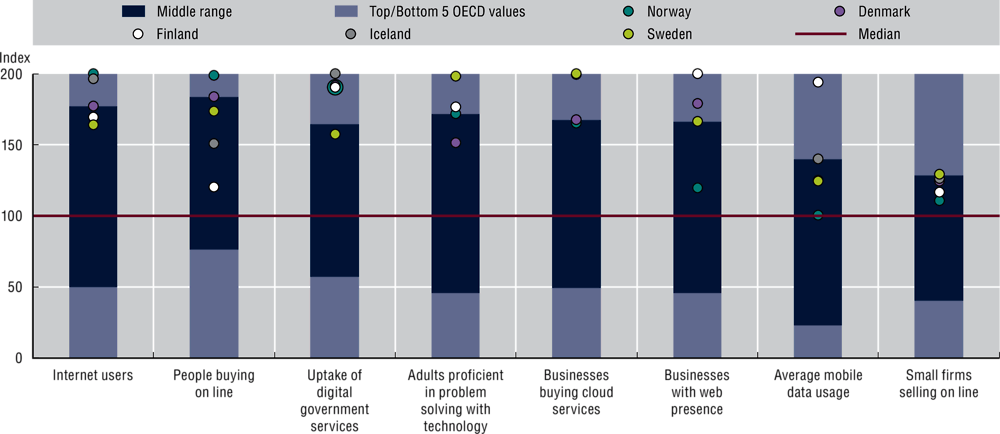

Norway has identified a range of priorities relevant to the Use dimension. These priorities include developing the data economy; increasing digitalisation of SMEs; digitalising the public sector; and promoting digital inclusivity, particularly in the context of an ageing society. Overall, Norway excels in the effective use of digital technologies – the country is among the first tier of best performing OECD countries (Figure 17)12.

Figure 17. Norway’s performance in the Use dimension

Normalised index of performance relative to the OECD median (index median = 100), 2022 (or latest available)

Note: Norway’s performance is compared to the median value observed in the OECD area, i.e. the middle position among OECD countries for which data are available.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD (2024[105]), “Use”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/dimension/use.

Norway has consistently led the way in Internet adoption, with an impressive 96% of people aged 16-74 being frequent Internet users (OECD, 2024[33]). The prevalence of Internet users purchasing on line (92%) is among the highest in the OECD, along with the Netherlands and the United Kingdom (OECD, 2024[34]). In addition, Norway stands out for its robust online business presence. In all, 83% of Norwegian companies maintained a website or homepage in 2022, although this is slightly behind the Nordic average of 90% (OECD, 2024[35]).

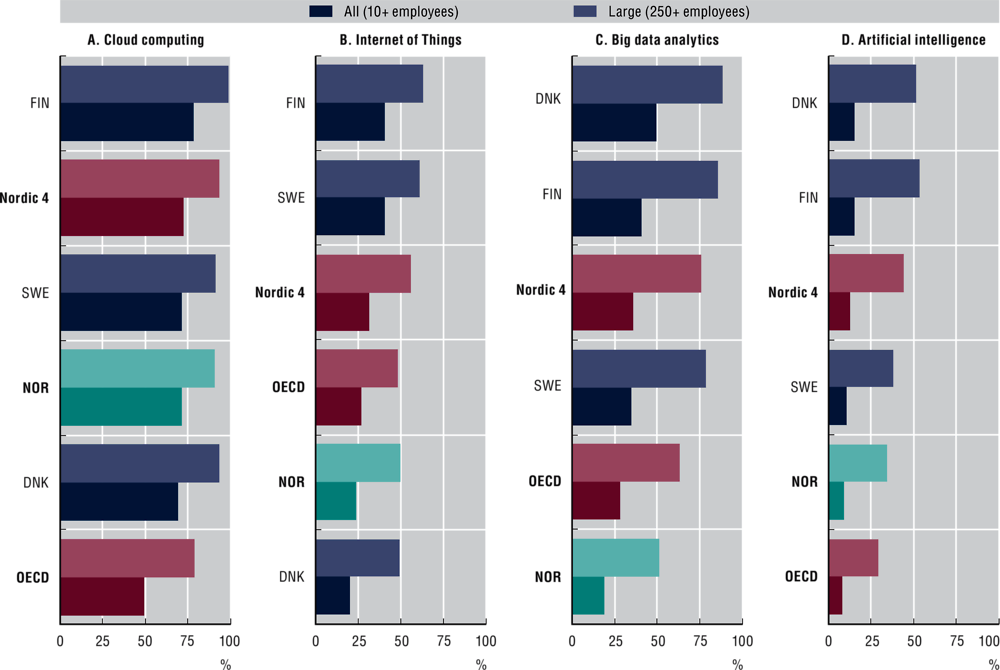

As digital transformation continues, digital tools have become indispensable for the effective use of technology. Sophisticated technologies such as cloud computing, IoT, big data analytics and AI are crucial for improving business efficiency. In particular, Norwegian companies with ten or more employees have widely adopted cloud computing, closely matching the Nordic average and exceeding the OECD average. However, adoption of IoT technologies, big data analytics and AI is relatively low and lags the Nordic average (Figure 18)7. Larger companies are more likely adopters of these advanced technologies, highlighting the importance of further investment in skills. For all firms, a shortage of more advanced ICT skills appears to be slowing the rate of digitalisation in the private sector (KPMG, 2020[36]).

Figure 18. Adoption rates of cloud computing, IoT technologies, big data analytics and AI

As a percentage of businesses with 10 employees or more and 250 employees or more, 2021-23

Note: Enterprises with ten employees or more in the business sector (excluding financial services).

Source: OECD (2024[88]), ICT Access and Usage Databases, https://oe.cd/dx/ict-access-usage.

Norway’s policy landscape related to Use

Norway’s impressive Internet usage statistics point to a population of early adopters with a solid foundation of basic skills. Use is the dimension that corresponds to the highest number of Norway’s national digital priorities. Therefore, achieving success in this area is critical as Norway plans for the future. With over NOK 1 billion allocated over three large, multi-year policy initiatives, Norway has clearly made it a priority to provide and improve digital public services, teach foundational skills and ensure as much of Norwegian society as possible can benefit from digital transformation.

The Norwegian government’s digital government strategy is “One digital public sector” (Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Regional Development, 2019[37]). However, a new comprehensive strategy encompassing digital government and the digital economy is under development. This strategy, supported by a budget of NOK 1 billion, aims to boost the digitalisation of Norway’s public sector in three ways. First, it will improve the quality and breadth of digital public services. Second, it will increase co-ordination within the public sector and co-operation between the public and private sectors by creating a common ecosystem and improved procurement processes. Third, it will build the digital competences of public sector employees. Beyond this, other initiatives in the Use dimension focus on improving basic ICT skills for all citizens and improving the innovative potential of the public sector.

Norway is responding to policy gaps in two key areas: increasing business dynamism and helping SMEs to digitalise, which is a priority for Norway. A new plan aims to help the education sector better nurture the skills needed for a modern, digital economy (Norwegian Ministry of Education, 2023[38]). In addition, the trade organisation Digital Norway, backed by the government, provides guidance and short training courses for SMEs seeking to digitalise. Despite these efforts, there is scope for additional policy development in this area. More incentives to encourage firm digitalisation, for example, could result in higher uptake of available courses. Norway could also increase expenditure on ICTs, which is relatively low for a country so digitally advanced.

Through the new national digital strategy (NDS), Norway could promote a culture that encourages more risk taking to strengthen the dynamism of SMEs. Norwegian firms seem reticent to build on successful limited pilots with large-scale digital transformation projects. In part this may be due to a historically strong economy based on extraction of raw materials, where the business case for digitalisation is not always clear-cut. As another potential factor, the national business culture often does not encourage risk taking. For the forthcoming NDS, Norway may wish to consider policies to increase business dynamism, such as changes to insolvency regimes to make bankruptcy less penalising (Adalet McGowann and Andrews, 2018[40]).

Data-driven and digital innovation

Innovation helps push out the frontier of what is possible in the digital age, driving job creation, productivity and sustainable growth. The formation of new companies, and the spread of new ideas in existing ones, leads to better and more effective service. It also creates new products and business models that can have profoundly positive effects on society at large.

Progress in the Innovation dimension requires specific measures to support and stimulate innovative entrepreneurs and SMEs, alongside balancing competition regimes to allow new entrants to disrupt existing markets. Discovery is an important enabler of innovation, which requires stimulation and commercialisation of scientific research. Sectors such as healthcare, agriculture and the public sector need to be ready to experiment and implement new technologies. This, in turn, may require reforms and dedicated strategies or policy measures.

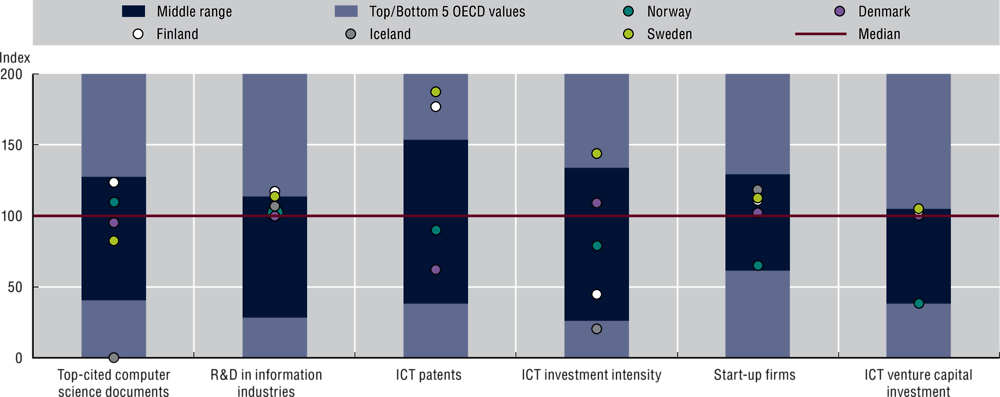

Norway has prioritised increasing the digitalisation of SMEs and the public sector, as well as developing the data economy. These are all priorities relevant to the Innovation dimension, making progress paramount. This is especially true as Norway lags the other Nordic countries and ranks below the OECD median for most related indicators (Figure 19)12.

While Norway is a strong innovator overall, it faces challenges in catching up to its Nordic neighbours in terms of digital innovation performance. Unlike Sweden and Finland, which are home to globally recognised companies like Spotify and Nokia, Norway’s industrial innovation is not heavily focused on ICT companies (Parmiggiani and Mikalef, 2022[41]). As a result, Norway is far from realising its full digital innovation potential.

Figure 19. Norway’s performance in the Innovation dimension

Normalised index of performance relative to the OECD median (Index median = 100), 2022 (or latest available)

Note: Norway’s performance is compared to the median value observed in the OECD area, i.e. the middle position among OECD countries for which data are available.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD (2024[92]), “Innovation”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/dimension/innovation.

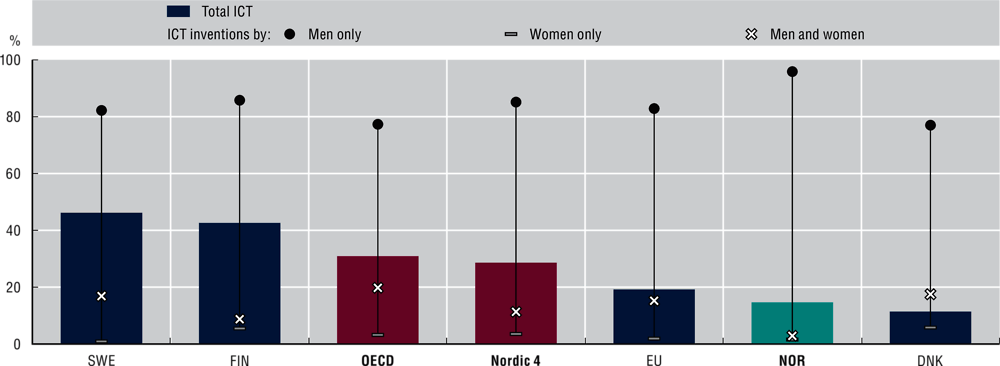

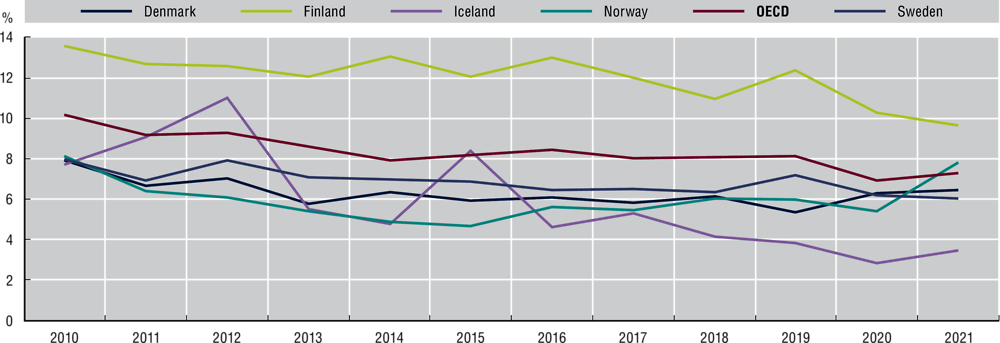

Promoting digital innovation requires intangible assets such as patents and software. Yet Norway faces a notable disparity when compared with its Nordic counterparts in terms of intellectual property related to the ICT sector. Data from 2019 reveal that only 14% of all Nordic patents in Norway were in ICT, a substantial lag behind Sweden (46%), Finland (42%) and the Nordic (29%) and OECD (31%) averages (Figure 20, Panel A)8. Furthermore, Norway’s share of the top 10% of most-cited documents in computer science as a share of the top 10% in all fields has consistently remained below the Nordic and OECD averages since 2010 (Figure 20, Panel B)9. Adding to this, Norway’s investment in ICT as a share of GDP has tended to remain at low levels. In 2022, ICT investment as a share of GDP was 2%, below the Nordic (3%) and OECD (3%) averages (OECD, 2024[42]).

Figure 20. Innovation activity in Norway

Panel A. Patents in ICT technologies as a share of total IP5 patent families, 2019

Note: Patents protect technological inventions (i.e. products or processes providing new ways of doing something or new technological solutions to problems).

Source: OECD (2024[97]), “Patents in ICT technologies as a share of total IP5 patent families”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, based on the OECD STI Micro-data Lab: Intellectual Property Database (http://oe.cd/ipstats), https://goingdigital.oecd.org/indicator/33.

Figure 20. Innovation activity in Norway

Panel B. Top 10% most-cited documents in computer science as a share of the top 10% ranked documents in all fields, 2010-21

Note: Top-cited publications are the 10% most-cited papers normalised by field and type of document (articles, reviews and conference proceedings).

Source: OECD (2024[102]), “Top 10% most-cited documents in computer science, as a share of the top 10% documents ranked in all fields”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, based on OECD calculations using Scopus Custom Data, Elsevier, and Scimago Journal Rank from the Scopus journal title list, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/indicator/32.

Norway lags other OECD countries for venture capital (VC) investment in ICT firms, with negative consequences for start-ups in information industries. Access to finance is an essential part of the digital innovation landscape, and VC investment is an important source of funding, especially for high-risk and innovative firms. However, VC investment in firms within the ICT sector in Norway is among the lowest across the OECD, accounting for only 1% of the GDP in 2022 (OECD, 2024[12]). This extends to VC investments in AI, where Norway’s share is relatively low considering GDP (OECD, 2024[43]). The shortfall of VC investment can affect the start-up ecosystem, hindering essential resources for young firms to thrive. Norway trails other Nordic countries in terms of start-up firms in information industries.10 In 2021, the share of start-up firms in information industries was as low as 24%, below the Nordic average of 32% (OECD, 2024[44]). In addition, Norway is only home to just over a quarter of the number of unicorns – tech companies valued at over USD 1 billion – as neighbouring Sweden (11 versus 42) (Dealroom.co, 2024[45]).

In recent years, Norway has been allocating less of its GDP to research and development (R&D), which may also be undermining digital innovation. Norway experienced robust growth in R&D as a share of GDP in 2015 (9%) and 2017 (7%). However, the following years saw lower increases of 2-3%. In 2020, Norway allocated 2% of its GDP to R&D with the private sector contributing to almost half of the investment (The Research Council of Norway, 2021[16]). In the information industries, which are crucial for digital innovation, business expenditure on R&D as a share of GDP in Norway (0.4%) is below Finland (0.7%), Sweden (0.7%) and the Nordic average (0.5%) (OECD, 2024[46]).

Nonetheless, Norway has made efforts to foster digital innovation in the public sector. This is evident in its commitment to delivering innovative services (OECD, 2017[47]) and developing integrated digital systems for data sharing across sectors. This commitment has led to the early creation of innovative public portals such as Altinn and ID-porten. These portals facilitate digital communication, identification and authentication between public authorities, citizens and businesses (Parmiggiani and Mikalef, 2022[41]; Government of Norway, 2024[48]). These efforts produced an impressive result: in 2022, 91% of the Norwegian population used the Internet to interact with public authorities (OECD, 2024[49]).

Norway’s policy landscape related to Innovation

Somewhat paradoxically, Norway has the highest number of major digital initiatives, especially with respect to data, in the Innovation dimension. In 2021, Norway published “Data as a Resource” – a landmark policy paper backed with NOK 300 million of investment. The paper set out the immense potential for value creation in both the public and private sectors from increased sharing of, and innovation with, data (Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2021[50]). This document shows that Norway is at the front of the pack for developing policies to foster data-driven innovation and its potentially positive impacts on all parts of the economy and society.

This culture of data innovation is further reinforced by two separate regulatory sandboxes. Datatilsynet stimulates responsible AI innovation through free guidance to a selection of qualifying companies of various size and across different industries (Datatilsynet, n.d[51]). For its part, Finanstilsynet has run a similar initiative since 2018. It aims to help fintech firms gain better understanding of regulations so they can launch innovative products. In return, the supervisory authority can gain useful insights into new technological developments that help it anticipate regulatory challenges.

Norway is building on the strength of its hydropower industry and climate to develop a data centre industry that can serve foreign clients. Norway has an abundance of clean energy generated by an advanced hydropower industry (Business Norway, 2023[52]). This foundation, combined with an Arctic climate and excellent connectivity, gives Norway natural potential for data centres. Indeed, in its 2021 data centre strategy, the Norwegian government aims to facilitate the sustainable development of the data centre industry by providing specific guidance for foreign companies (Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2021[53]).

Norway has also produced extensive work in the science and technology policy domain, laying the foundation for major investment in AI research. The latest iteration of Norway’s “Long-term Plan for Research and Higher Education” (Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research, 2023[54]) was published in 2023. The new strategy sets out ambitious proposals to enhance Norwegian competitiveness and innovation capacity. At the same time, it seeks to boost scientific research in six priority areas, including a range of industrial technologies such as AI, advanced robotics and quantum technology. The strategy includes an objective to increase R&D expenditure from business and industry to 2% of GDP by 2030. To that end, the government announced its intention to dedicate NOK 1 billion to AI research over the next five years.

Norway could harness its forthcoming NDS to update its approach to AI. Norway’s 2020 “National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence” addresses emerging challenges related to ethics, infrastructure and skills. These are issues that Norway must solve to realise its potential as an AI leader (Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2020[55]). The strategy is designed to be open-ended in recognition of the rapidly evolving policy environment. With this in mind, the forthcoming NDS could be an opportunity to refresh the current position in light of the recent emergence of large language models.

While the government encourages innovation, it could do more to help young firms access funding. The government-founded Innovation Norway provides funding and guidance to innovative companies, including those in early-stage development. However, additional policies to stimulate entrepreneurship and SME growth could help young companies to thrive. These could include building incubators or increasing access to patient and risk-tolerant capital at seed stage. The latter would recognise that firms in emerging areas may not guarantee immediate returns or success.

Finally, Norway could benefit from policies that encourage a greater spirit of entrepreneurship and competition. A culture of risk aversion among Norwegian businesses and investors could hinder the country’s ability to fully capitalise on its innovative potential. In response, it could design policies to encourage start-ups from research institutions and introduce reforms to ensure business failure or insolvency is not overly penalised. Together, these changes may help foster a more entrepreneurial spirit and lead to value creation through increased start-up success. In addition, Norway could encourage new market entry and disruption and further boost its innovative potential. This could include a review of regulatory frameworks to ensure they do not favour incumbents.

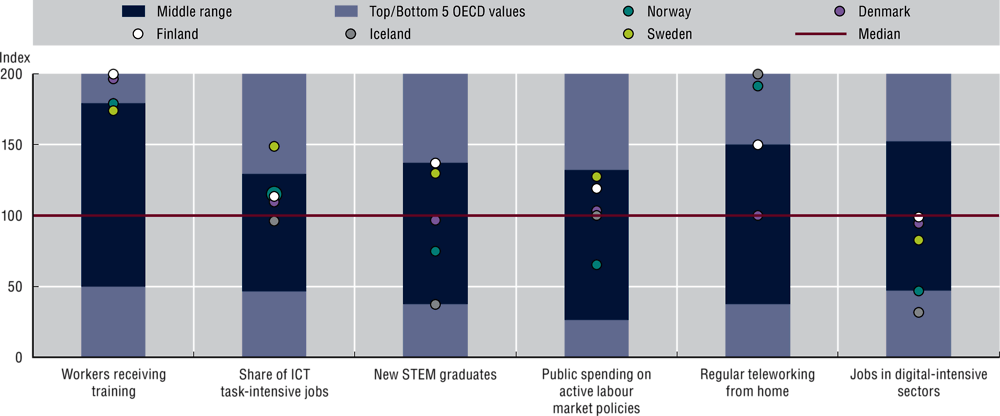

Jobs fit for the digital age

Digital transformation leads to creative destruction, with some jobs lost and others created. As labour markets transform, many new jobs are likely to be in unfamiliar areas. It is thus essential to empower people with the mix of skills to succeed in a digital world of work. This includes improving education and training systems throughout the life cycle, facilitating job-to-job transitions and ensuring adequate social protection. Some workers are likely to benefit more from digital transformation than others. Thus, an adequate safety net is needed to ensure a successful and fair transition for all. Overall, Norway’s performance in the Jobs dimension falls within the mid-range among OECD countries but lags behind most of its Nordic counterparts (Figure 21)12.

Figure 21. Norway’s performance in the Jobs dimension

Normalised index of performance relative to the OECD median (index median = 100), 2022 (or latest available)

Note: Norway’s performance is compared to the median value observed in the OECD area, i.e. the middle position among OECD countries for which data are available.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD (2024[93]), “Jobs”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/dimension/jobs.

Norway’s performance in the Jobs dimension is mixed. High levels of digital literacy, a well-educated population and a high employment rate11 in Norway mask some alarming trends. Attainment in foundational subjects such as mathematics, science and reading is declining (see Society section). Meanwhile, inequality of education is increasing alongside the skills gap reported by Norwegian companies (NHO, 2022[56]). In one notable concern, the labour market has tightened in recent years, measured by the number of vacancies per unemployed person (OECD, 2023[57]). This situation reflects, among others, a mismatch between available and demanded skills in the country, particularly among high and middle-skilled occupations (OECD, 2022[58]).

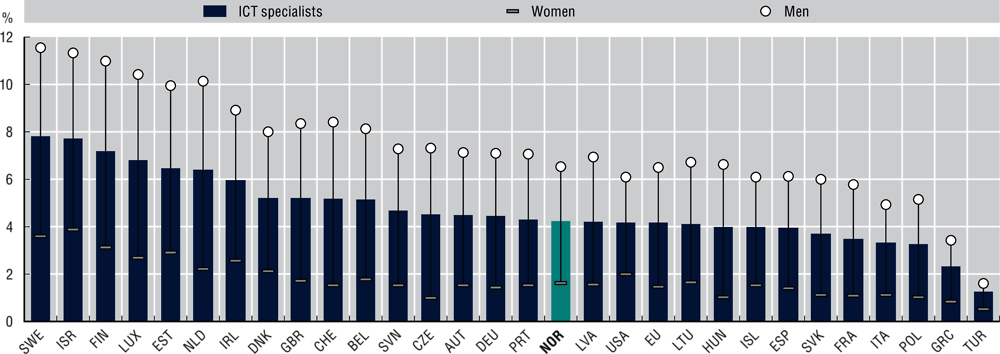

The lack of specialised and skilled workers across sectors is a prevailing concern among Norwegian stakeholders and researchers. Professional competence gaps are identified as a prominent barrier for labour market participation, hindering companies from fully benefiting from digital transformation (KPMG, 2020[36]). In all, 46% of companies in Norway surveyed in 2023 tried to recruit without obtaining the desired expertise (NHO, 2023[39]). Indeed, Norway’s share of ICT specialists lags most of its Nordic neighbours, with a worrying five percentage point gap between men and women (Figure 22)12.

Norway could better align its workforce to the demands of a highly digital economy. As use of digital technologies in the workplace continues to grow, and technological advancements unfold rapidly, the demand for a workforce adept in ICT-related tasks and in digital-intensive industries intensifies. However, the share of employees engaged in ICT-related tasks has remained relatively stable in Norway over the last decade. In contrast, countries like the Netherlands and Sweden have seen this proportion increase by seven percentage points over the same period (OECD, 2024[59]). In addition, the share of the labour force employed in high and medium-high digital-intensive industries hovers around 43% in Norway, slightly below the OECD (50%) and Nordic (45%) averages in 2018 (OECD, 2024[60]). This points to a potential area of improvement to align Norway’s workforce composition with the evolving demands of a highly digital economy.

Part of the mismatch between labour supply and demand could reflect inadequate levels of active labour market programmes. Not all workers will adapt quickly to the evolving demands of digital technologies. Consequently, adequate social protection becomes crucial to successfully match the new needs of businesses with supply. This involves providing displaced workers with active labour market programmes that include job search services and training. In recent years, Norway has performed below the Nordic and OECD averages in this area. Public spending on active labour market programmes is also notably low, accounting for only 25% of GDP, below the OECD (52%) and Nordic (55%) averages. In particular, public spending on training has fallen significantly in recent years, which could explain the current skill mismatch in the country (OECD, 2024[61]).

Figure 22. ICT specialists

ICT specialists as a percentage of all occupations, by gender, 2022 (or latest available)

Source: OECD (2024[59]), “Share of ICT task-intensive jobs”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, based on European Labour Force Surveys, national labour force surveys and other national sources, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/indicator/40.

Norway’s policy landscape related to Jobs

With one exception, Norway lacks a wide range of major policy initiatives related to the digitalisation of labour markets. While Norway has generally robust labour market policies, it has only a single policy focused on digitalisation. “Overview of Skills Needs in Norway” (Norwegian Ministry of Education, 2023[38]), launched in 2023, recognises the size of the skills challenge, offering constructive approaches towards tackling it. For example, it focuses on investment in skills provision to working-age adults outside of the labour market. It also proposes reforms to university funding mechanisms to incentivise lifelong learning and professional retraining. In addition, given the concentration of educational institutions in Oslo, it suggests changes to spread skills provision throughout the country.

While “Overview of Skills Needs in Norway” does not identify ICT skills as a government priority, it clearly acknowledges the need for long-term reforms in the education system. Apart from an increasingly digitalised world, the education system faces challenges such as an ageing population and the green transition. In addition, the government has also committed to publishing an additional skills reform targeted at working life, expected in the course of 2024. This offers an opportunity to further develop policies to maximise the benefits and mitigate the disruptive effects of increased levels of digitalisation (Norwegian Ministry of Education, 2023[38]).

Despite the positive steps by Norway in the Jobs dimension, a number of domains remain underexplored. Early consideration of labour market policies may be warranted to ensure successful and fair transitions of workers between industries and jobs. In addition, Norway could develop a detailed plan to ensure it can produce enough advanced ICT specialists to complement its high level of foundational skills. Changing careers can be difficult. Therefore, Norway might benefit from an evaluation of social policies. This could consider whether those working in jobs most at risk of automation have access to the requisite advice and guidance, including support for job searches.

In addition, notwithstanding Norway’s excellent social safety net, new models of employment – such as the platform economy – may alter the landscape for labour. Consequently, it could reflect on how these protections could be maintained as new employment models take hold. While studies suggest the number of platform economy workers in Norway is marginal (Ilsøe and Jesnes, 2020[62]), this growing phenomenon may require a novel policy response.

A prosperous and inclusive digital society

Societal effects of digital transformation are complex because overall impacts are often not clear-cut, and they do not affect all segments of society equally. Action in the Society dimension helps ensure every citizen can share in the benefits of digital transformation. It also minimises the number of people who find themselves excluded due to their age, gender, economic circumstances or level of educational attainment. In addition, it provides opportunities to enhance access to information via a free and interconnected Internet and improve information integrity. Moreover, it aims to ensure that societal challenges are realised, including those related to providing quality healthcare, supporting a modern and digital government, and ensuring the green transition.

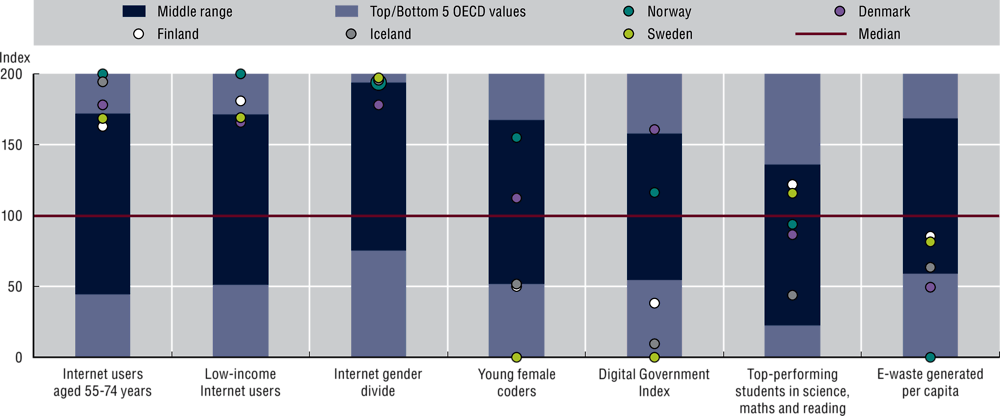

Norway has identified a range of priorities relevant to the Society dimension that can support its overall ambitions for its digital future. Key priorities for the Society dimension include supporting the green transition, digitalising the public sector and promoting digital inclusivity, particularly in the context of an ageing society. It is therefore essential to focus on the Society dimension to achieve Norway’s policy ambitions. Overall, Norway excels in this dimension, outperforming both the OECD median value and the Nordic countries (Figure 23)12.

Figure 23. Norway’s performance in the Society dimension

Normalised index of performance relative to the OECD median (index median = 100), 2023 (or latest available)

Note: Norway’s performance is compared to the median value observed in the OECD area, i.e. the middle position among OECD countries for which data are available.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD (2024[101]), “Society”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/dimension/society.

Norway has been successful in addressing societal challenges related to digitalisation. Notably, there has been significant progress in narrowing age disparities in Internet usage since 2018. The elderly population (aged 55-74) has made notable progress in catching up with the overall population’s Internet usage. In 2022, the gap between daily Internet usage among the elderly and the wider population (aged 16-74) was only five percentage points compared to nine in 2018 (OECD, 2024[33]). Looking beyond Internet use, the population in Norway is among the most digitally literate across OECD countries, along with other Nordic countries (Iceland and Finland) and the Netherlands.

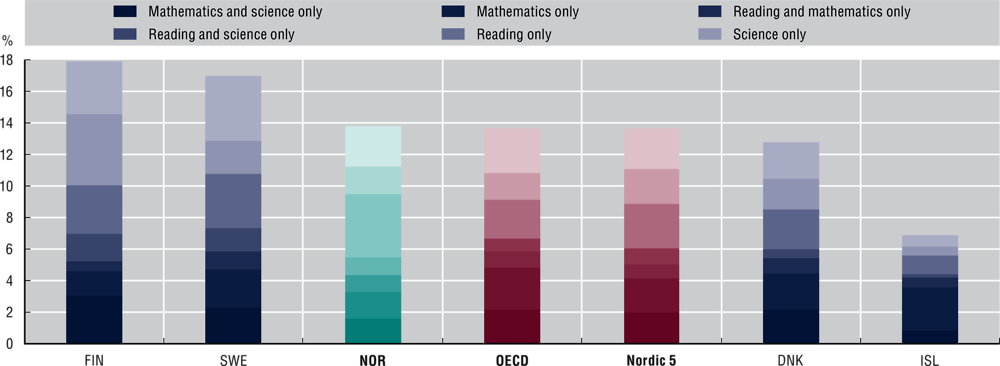

However, recent data suggest a need for improvement to ensure that individuals can meet the demands of an increasingly digital economy and society. Insights from the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) indicate a significant decline in Norway’s performance in science, mathematics and reading – critical skills to thrive in the digital economy. Norway’s performance in 2022 marks the lowest scores ever recorded in the survey, with mathematics suffering the highest decline in the short term (-32.5% from 2018 to 2022) (OECD, 2023[63])13. Despite this decline, Norway remains in line with the average across OECD countries, although below the performance of Finland and Sweden (Figure 24)14.

PISA also highlights another concerning trend in Norway: an increase in educational inequality. The gap in learning outcomes of reading and science between the best and the worst students has increased since 2018. The survey also shows a widening gap between the performance of the most advantaged and disadvantaged students in terms of socio-economic status from 2012 to 2022 in Norway. Most OECD countries did not experience such a downward trend (OECD, 2023[63]).

Norway also faces challenges in encouraging students to pursue degrees in ICT and other STEM fields, a critical aspect to succeed in technology-rich work environments. In 2021, the number of students in Norway graduating in ICT or STEM fields lagged all countries for which data are available, except Brazil. This lag existed despite the government’s special emphasis on ICT-related study programmes since 2015. Data indicate a noticeable gender gap, with only 2% of women graduating in ICT degrees in 2021 compared to 11% of men (Eurostat, 2023[64]). This gender disparity extends to programming skills, with only 21% of women having coding skills compared to 29% of men (OECD, 2024[65]). Norway also trails the OECD average in terms of the availability of workers with AI skills, a critical capability in an increasingly digital economy and society (OECD, 2024[66]).

Figure 24. Top-performing students in science, mathematics and reading

Percentage of 15-16 year-old students, 2022

Source: OECD (2024[103]), “Top-performing 15-16 year old students in science, mathematics and reading”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, based on the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) Database (https://oe.cd/pisa), https://goingdigital.oecd.org/indicator/52.

Norway’s policy landscape related to Society

Norway is taking action to ensure all segments of society are competent in digital technologies. Norway’s “Digital Throughout Life” strategy, published in 2021 and supplemented with an accompanying Action Plan in 2023, identifies and seeks to address a range of issues that might lead to digital exclusion (Norwegian Ministry of Digitalisation and Public Governance, 2021[67]; Norwegian Municipal and District Ministry, 2023[68]). The strategy acknowledges that Norway has a highly skilled population with excellent basic skills and a propensity to use digital technologies regularly.

Despite Norway’s overall digital competence, some segments of society tend to be left behind. These include the elderly, those with health challenges, people of working age not in education or employment, and first-generation non-western migrants (particularly women). The strategy proposes several policy measures to address these gaps. First, it seeks to expand basic digital competence training delivered through local hubs such as libraries. Second, it commits to designing digital government services so they are accessible even to those with little or no ICT skills. Third, it plans information campaigns to ensure that schools teach fundamental concepts such as data protection and cybersecurity.

A new long-term strategy sets out a vision for healthcare in Norway. As highlighted in Section 1, Norway is a leader in the sharing of health data and a pioneer in using electronic health records and advanced technologies, like AI, for enhancing innovation in healthcare (Trocin et al., 2022[69]). Last year, the Norwegian government set out its long-term vision for the future of digital health. Norway delivers healthcare through a constellation of different organisations and authorities. With this in mind, the strategy establishes high-level objectives for ensuring digital technologies contribute towards a high-quality, sustainable and innovative health and care sector in Norway. It is hoped the wider Norwegian health and care ecosystem will incorporate these objectives into its strategic planning (Norwegian Directorate of e-health, 2023[70]).

Overall, the action by the Norwegian government to date shows a clear focus on the Society dimension. Norway should ensure that progress in this dimension continues in the next NDS. In addition, while Norway has set a clear target of adapting to the climate transition, it has scope for further policy action to assess how digital technologies can help meet this goal.

Trust in the digital age

Trust is a vital precondition to ensuring the digital ecosystem flourishes effectively. Citizens and businesses must feel safe, secure and empowered as they interact and share data in digital environments to realise the full potential of data-driven technologies. Policies in the Trust dimension help protect citizens and firms by increasing digital security and protecting user privacy. The number of products and services purchased and consumed on line has grown significantly. As a result, ensuring consumer protection laws are appropriate for new forms of commerce is an important part of this dimension.

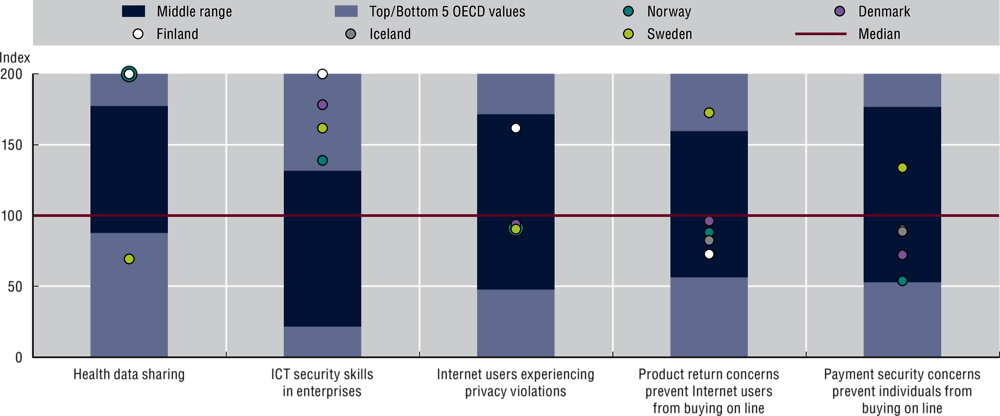

Achieving success in the Trust dimension is foundational to many of Norway’s digital policy priorities. Norway aims to foster data protection and information security, develop the data economy, increase the digitalisation of SMEs and promote an inclusive digital society in the context of an ageing population. All these objectives rely on adequate protections to allow Norwegian citizens to actively participate on line with confidence. Research also underscores the strong culture of trust and collaboration among public authorities, businesses and citizens in Norway, with the government seen as a trusted data steward (Overby and Audestad, 2022[71]). Norway’s performance in the Trust dimension is in the top tier of the best performing OECD countries and in line with Nordic countries for most indicators (Figure 25)12.

Figure 25. Norway’s performance in the Trust dimension

Normalised index of performance relative to the OECD median (index median = 100), 2022 (or latest available)

Note: Norway’s performance is compared to the median value observed in the OECD area, i.e. the middle position among OECD countries for which data are available.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD (2024[104]), “Trust”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/dimension/trust.

Survey data show that Norwegians have high levels of trust in how public agencies handle their personal data (Datatilsynet, 2020[72]). In all, 84% of respondents expressed great or at least some trust in the data-handling practices of public agencies, particularly in the tax and health sectors. In contrast, less than 13% reported similar trust in how private enterprises managed their data. This low level of trust was especially true in those offering services through social media, messaging platforms and search engines. The survey also revealed that over half of respondents refrained from using certain services due to uncertainties regarding data-handling practices. Moreover, the low incidence of personal information or privacy violations, standing at 3%, significantly contributes to fostering a trustworthy environment in Norway (OECD, 2024[73]).

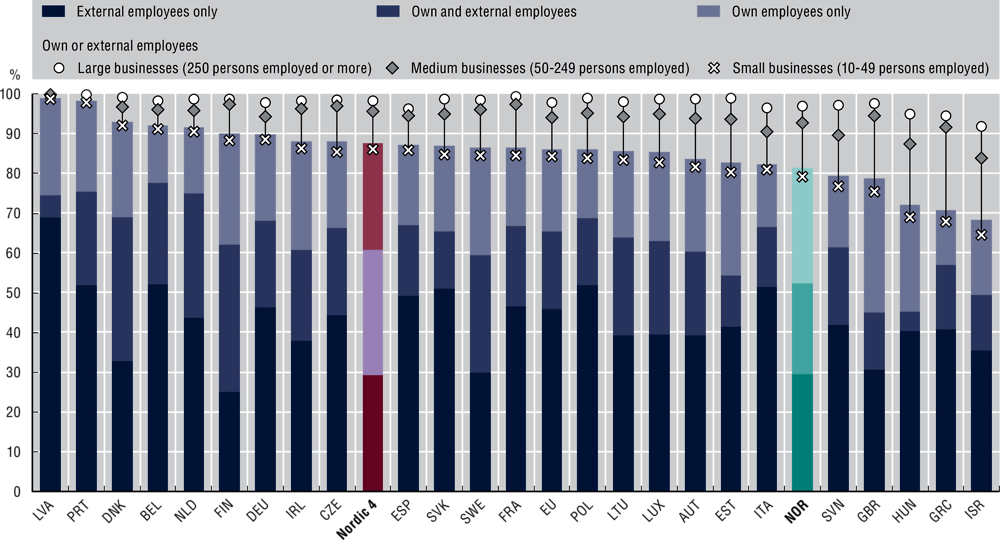

Digital security risk management plays a key role in ensuring trust. Employees engaged in ICT security-related activities, such as testing, training and resolving incidents, are key drivers of cybersecurity risk management. In Norway, the proportion of firms with in-house ICT security (52%) is below the Nordic average (58%). Larger enterprises are more likely to integrate cybersecurity risk management skills into the firm than to outsource to other firms (Figure 26)15. Having in-house cybersecurity personnel is not always efficient, especially for small firms. However, cybersecurity skills should exist within the firm or through external service providers. Small firms in Norway lag their Nordic neighbours and many other OECD countries in this respect.

Figure 26. Share of enterprises in which own employees carry out ICT security

All businesses (excludes the financial sector, 10 persons employed or more), 2019

Source: OECD (2024[99]), “Share of enterprises in which own employees carry out ICT related activities”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, based on the Eurostat Digital Economy and Society Statistics Comprehensive Database, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/indicator/60.

Norway’s robust trust culture plays a pivotal role in promoting data sharing across individuals, as well as among private and public sectors (Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2021[50]). The country is at the forefront of understanding the growing importance of data sharing as a basis for developing the digital economy. Successful data-sharing initiatives have already made an impact in various sectors, including banking and agriculture. Endeavours like “AquaCloud” and “Trondheim” underscore the potential to enhance efficiency in industries such as fish farming and maritime (Norwegian Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, 2021[74]).

Norway’s policy landscape related to Trust

The fourth version of Norway’s cybersecurity strategy covers many elements in the Trust dimension. From a policy perspective, the Trust dimension is dominated by the 2019 National Cyber Security Strategy for Norway (Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security and Norwegian Ministry of Defence, 2019[75]), which is backed by NOK 1.6 billion of investment. Norway’s inaugural cybersecurity strategy in 2003 was one of the first of its kind in the OECD. The fourth and most recent iteration aims to protect Norwegian citizens and businesses by both expanding national cyber capabilities and building individuals’ cybersecurity awareness and skills. It contains more than 50 separate policy measures – from establishing a national cybersecurity centre to recommending 10 ways for companies to improve their cyber hygiene. Overall, it is a comprehensive strategy, covering a significant amount of the domains in the Trust dimension. At the same time, uncertainty related to cyber risks persists (see Figure 3), highlighting the need to stay focused on keeping people, firms and the government secure.

Beyond security issues, Norway uses EU regulations for some areas in the Trust dimension. Notably, as a European Economic Area country, Norway follows the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) (European Union, 2016[76]). The GDPR is an important standard for empowering individuals to control their personal data, and has been replicated in many jurisdictions. While much of the GDPR is standard for all participating countries, some areas such as enforcement allow derogations. Consequently, in April 2023, Norway introduced legislation to provide additional protection to consumers of online services (Norwegian Ministry of Justice and Public Security, 2023[77]), based on similar EU legislation enacted in 2019 (European Union, 2019[78]).

Market openness in digital business environments

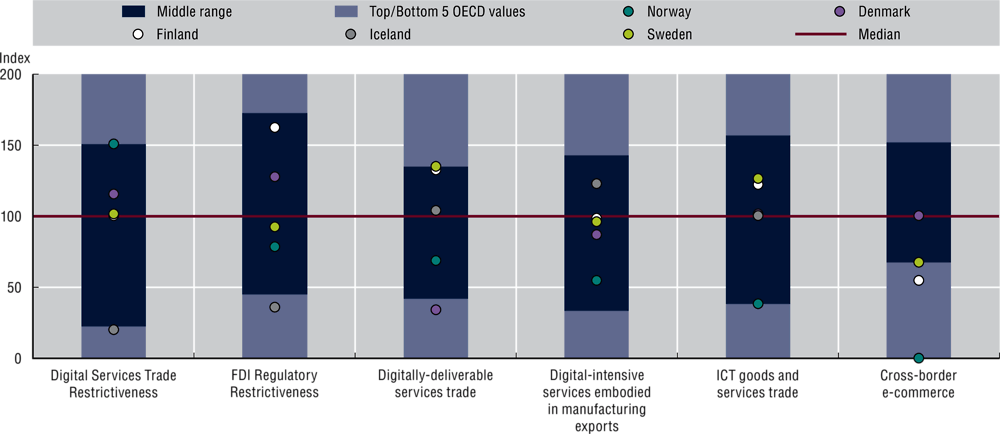

Digital technologies transform the way firms interact with each other and their consumers, enabling them to grow by expanding into new markets. They help open new frontiers for trade and competition, facilitating co-ordination of global value chains. As frontier technologies, applications and processes diffuse through open markets, open trade and investment regimes can create new avenues to upgrade technologies and skills rapidly, and increase specialisation. Norway has prioritised developing its data economy, which is related to the Market openness dimension. Overall, Norway’s performance in the Market openness dimension ranks in the lowest tier among OECD countries and falls below the level of other Nordic countries (Figure 27)12.

Figure 27. Norway’s performance in the Market openness dimension

Normalised index of performance relative to the OECD median (index median = 100), 2022 (or latest available)

Note: Norway’s performance is compared to the median value observed in the OECD area, i.e. the middle position among OECD countries for which data are available.

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on OECD (2024[94]), “Market openness”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/dimension/market-openness.

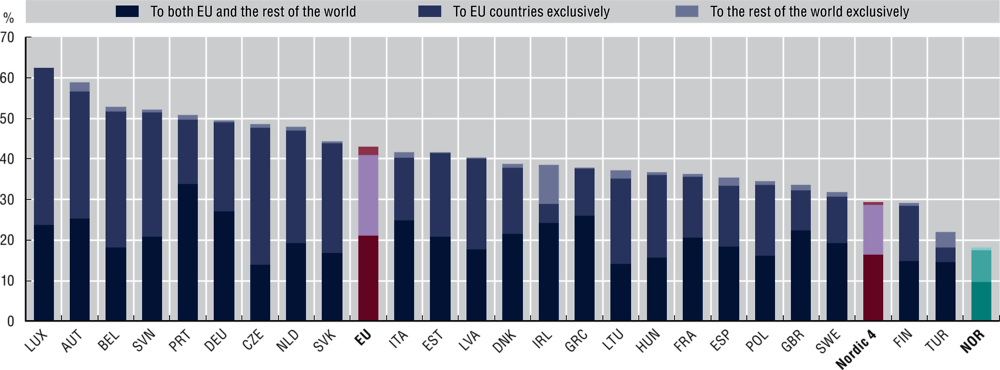

As its economy shifts from oil and gas, Norway needs policies to ensure SMEs can grow into global exporters. Norway’s exports rely heavily on natural resources, with crude oil and natural gas contributing to 73% of total exports of goods in 2022.16 Only 2% of exports in 2022 were ICT goods and services, such as computers, communication and consumer electronic equipment, well below the Nordic average of 8% (OECD, 2024[79]). As Norway’s economy continues its transition away from oil and gas, new companies, including those in service industries, are beginning to emerge. Helping these companies grow from high-potential innovative SMEs to large global exporters requires a dedicated policy response. Such firms, for example, need better access to international risk-tolerant and patient capital17. Financial markets and competition must also enable new market entrants to thrive, while protecting citizens from any negative impacts.

E-commerce lags in Norway in comparison to other Nordic and OECD countries. As digital transformation accelerates, e-commerce emerges as a promising avenue for businesses to reach diverse markets. However, cross-border e-commerce sales in Norway have consistently remained among the lowest among countries for which data is available since 2010, hitting a record low of 18% in 2020 (Figure 28)18. Digitalisation also increases exports of digitally deliverable services. However, Norway exhibits low shares of such services, representing only 23% of total commercial services trade in 2020. This was below the OECD (30%) and Nordic (31%) averages (OECD, 2024[80]). The low share of cross border e-commerce sales and digitally deliverable services suggests an inward orientation, driven either by explicit trade barriers or other factors. Since 2017, for example, there has been growing concern in Norway about payment security on line in contrast to a declining trend observed on average across Nordic and OECD countries (OECD, 2023[81]).

Figure 28. Share of businesses making e-commerce sales that sell across borders

All businesses (exclude financial sector, ten persons employed or more), 2020

Source: OECD (2024[98]), “Share of businesses making e-commerce sales that cross borders”, OECD Going Digital Toolkit, based on the Eurostat Digital Economy and Society Statistics Comprehensive Database, https://goingdigital.oecd.org/indicator/72.

Norway could reduce barriers to foreign investment in the financial services sector to enhance innovation. Reducing barriers to international investment is key for advancing digital transformation. Such investments not only allocate resources to more productive uses, but also foster an environment in which firms improve their efficiency. The OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index measures statutory restrictions on FDI. Overall, Norway’s FDI restrictiveness (0.08) slightly exceeds Nordic (0.07) and OECD averages (0.06). Notable restrictions are observed in the financial services sector (0.07) compared to neighbouring countries like Finland (0.01), and Denmark and Sweden, both of which have no restrictions in this sector (OECD, 2024[82]). This underscores areas in which Norway may consider improving its regulatory environment to attract more international investment to become more digital and innovative.

Norway’s policy landscape related to Market openness

Norway has no dedicated policy initiatives related to Market openness within its digital policy landscape. However, the government set up Innovation Norway to improve innovation and digitalisation in Norwegian businesses and help them expand abroad. Innovation Norway provides financing, training, advice, and promotion and networking for businesses in Norway, alongside tourism promotion. In 2022, it contributed over NOK 7.1 billion to development and innovation in industry and commerce. Of this, NOK 1.5 billion was allocated to companies less than three years old. It has offices in 23 different countries and works closely with Norwegian consulates to assist Norwegian businesses to access, and develop in, overseas markets.

Market openness appears to be one of the ripest areas for development of Norwegian digital policy. Stakeholder feedback characterises the Norwegian economy as traditionally insular and dominated by larger companies in traditional goods-based industries such as fossil fuels and fish. As discussed in the Innovation section, Norway clearly has vast innovative potential. Past success stories such as the ed-tech unicorn Kahoot! have shown what is possible. For companies like Kahoot! to continue to grow and thrive, further development of Market openness policies is essential.

Notes

← 1. For visualisation purposes, the contributions of any sectors that acted as a drag on economic growth in the period analysed are plotted below the x-axis (i.e. in negative space) to indicate that their contribution was contractionary. In contrast, any sectors that contributed positively to value-added growth are plotted above the x-axis (i.e. in positive space), including in cases where value-added growth in the country was negative overall. Data for Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Portugal and Switzerland relate to 2017.

← 2. Digital intensity is defined according to the taxonomy described in: Calvino et al., (2018[107]). High digital-intensive sectors include (ISIC Rev.4 Divisions): Transport equipment (29 to 30); Telecommunications (61); IT and other information services (62 to 63); Financial and insurance activities (64 to 66); Professional, scientific and technical activities; administrative and support service activities (69 to 82); and other service activities (94 to 96). Medium-high digital-intensive sectors include (ISIC Rev.4 Divisions): Wood and paper products; printing (16 to 18); Machinery and equipment (26 to 28); Furniture, other manufacturing, repair and installation of machinery and equipment (31 to 33); Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles (45 to 47); Publishing, audiovisual and broadcasting activities (58 to 60); Public administration and defence; compulsory social security (84); and Arts, entertainment and recreation (90 to 93). Medium-low digital-intensive sectors include (ISIC Rev.4 Divisions): Textiles, wearing apparel, leather and related products (13 to 15); Chemical, rubber, plastics, fuel products and other non-metallic mineral products (19 to 23); Basic metals and fabricated metal products, except machinery and equipment (24 to 25); Education (85); and Human health and social work activities (86 to 88). Low digital-intensive sectors include (ISIC Rev.4 Divisions): Agriculture, hunting, forestry and fishing (01 to 03); Mining and quarrying (05 to 09); Food products, beverages and tobacco (10 to 12); Electricity, gas and water supply, sewerage, waste management and remediation activities (35 to 39); Construction (41 to 43); Transportation and storage (49 to 53); Accommodation and food service activities (55 to 56); and Real estate activities (68).

← 3. The ICT sector is defined as the following three divisions of the 2-digit ISIC Rev.4 industry classification: Computer, electronic and optical products (D26), Telecommunications (D61), Information technology and other information services (D62-63/D62T63). The OECD average is calculated based on 27 countries: Austria, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Mexico, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States.

← 4. For 4G broadband coverage, because there are nine countries with maximum values, the top five are all 200. Consequently, no top tier area is visible in the figure. All indicators are standardised into indices and presented on a common scale ranging from 0 to 200, where 0 represents the lowest OECD value, 100 denotes the median value and 200 signifies the highest value. This standardisation ensures comparability across indicators, facilitated by an established methodology (OECD, 2014[85]). Benchmark charts further elucidate the distribution by highlighting the positions and spread of the top five and bottom five OECD values. When data are not available, the country’s relative position does not figure on the graph. Given  the indicator for country c at time t, and

the indicator for country c at time t, and  ,

,

, the respective OECD maximum, median and minimum values for this indicator, the country index

, the respective OECD maximum, median and minimum values for this indicator, the country index  is calculated as follows:

is calculated as follows:  = 100 + (

= 100 + ( –

–  )/

)/ ;

;  = 100 –(

= 100 –( –

–  )/

)/ .

.

← 5. The data refer to uptake of fixed broadband by firms in the year indicated, although some countries may use different periods and the period may vary over time. The OECD ICT Access and Usage Databases include data from Eurostat. In 2020, Eurostat changed the way this survey question is asked, which may affect responses. The Nordic 4 is a simple average of the values from Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden.

← 6. Machine-to-machine SIM cards refer to SIM cards that are sold specifically for use in machines and devices (e.g. smart meters and surveillance cameras) and are not part of a consumer subscription.

← 7. Data relate to 2023, except for IoT (2021). Data refer to “data analytics” instead of “big data analytics” for the Nordic 4 countries. For all panels, the Nordic 4 is a simple average of the values from Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden.

← 8. The Nordic 4 is a simple average of the values from Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden.

← 9. The Scimago Journal Rank indicator is used to rank documents with identical numbers of citations within each class. This measure is a proxy indicator of research excellence. Estimates are based on fractional counts of documents by authors affiliated to institutions in each economy. Documents published in multidisciplinary/generic journals are allocated on a fractional basis to the ASJC codes of citing and cited papers. The field Computer Science comprises the following sub-fields: Artificial Intelligence, Computational Theory and Mathematics, Computer Graphics and Computer-Aided Design, Computer Networks and Communications, Computer Science Applications, Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Hardware and Architecture, Human-Computer Interaction, Information Systems, Signal Processing and Software.

← 10. Information industries combines the OECD definitions of the “ICT sector” and the “content and media sector”, described in: (OECD, 2011[86]). While this definition includes detailed (three- and four-digit) ISIC Rev.4 industrial activities, in this analysis it is approximated by the following ISIC Rev.4 (two-digit) Divisions, due to limited data availability: “Computer, electronic and optical products” (26), “Publishing, audiovisual, and broadcasting activities” (58 to 60), “Telecommunications” (61) and “IT and other information services” (62 to 63).

← 11. More information available at: www.ssb.no/en/arbeid-og-lonn/sysselsetting/statistikk/arbeidskraftundersokelsen (accessed on 25 January 2024) (Statistisk sentralbyrå [Statistics Norway], 2024[109]).

← 12. ICT specialist occupations are identified by three-digit classes of the 2008 revision of the International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08): Information and communications technology service managers (133), Electrotechnology engineers (215), Software and applications developers and analysts (251), Database and network professionals (252), Information and communications technology operations and user support (351), Telecommunications and broadcasting technicians (352) and Electronics and telecommunications installers and repairers (742). The Nordic 5 is a simple average of the values from the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden).

← 13. Norway’s performance is in line with the average for OECD countries. There was a record drop in performance in mathematics, reading and science.

← 14. Top performers in science, mathematics and reading are students aged 15-16 years who achieved the highest level of proficiency (i.e. Levels 5 and 6) on the OECD PISA assessment. The Nordic 5 is a simple average of the values from the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden).

← 15. Small firms are defined as enterprises that have between 10 and 49 employees, medium firms as enterprises with between 50 and 249 employees, SMEs as enterprises with between 10 and 249 employees, and large firms as enterprises with 250 or more employees. For Canada, medium-sized enterprises have 50-299 employees and large have 300 or more employees. For Japan, data refer to enterprises with 100 or more employees instead of 10 or more. Medium-sized firms have 100-299 employees and large firms have 300 or more employees. The Nordic 4 is a simple average of the values from Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden.

← 16. More information available at: www.norskpetroleum.no/en/production-and-exports/exports-of-oil-and-gas (accessed on 15 February 2024) (Norwegian Petroleum, 2023[110]).

← 17. Risk-tolerant and patient capital refer to investments by investors willing to fund riskier business models with short-term returns that are not guaranteed.

← 18. An e-commerce transaction is the sale or purchase of goods or services, conducted over computer networks by methods designed to receive or place orders. The goods or services are ordered by those methods, but the payment and the ultimate delivery of the goods or services do not have to be conducted on line. An e-commerce transaction can be between enterprises, households, individuals, governments, and other public or private organisations (OECD, 2011[86]). E-commerce sales (orders received over computer networks) include orders for goods or services placed via a website or apps and sales made via Electronic Data Interchange type messages, but do not include sales via manually typed e-mail orders. For Mexico, data refer to businesses receiving orders via the Internet, instead of over computer networks. The data refer to businesses making e-commerce sales that also sell across borders in the year indicated, although some countries may use different periods and the period may vary over time.