This chapter focuses on women’s economic empowerment in Tanzania, building on data collected within the framework of the SIGI Tanzania. The first section explores different aspects of women’s participation in the labour market, ranging from access to employment to the type of jobs and sectors in which they work. The section also highlights how social norms, including those limiting women’s education, and traditional views of women’s roles, affect their status and position in the labour market. The second section of the chapter examines women’s access to agricultural land, a critical productive asset in Tanzania. It assesses the current situation of women regarding ownership and control over agricultural land, highlighting recent legal changes that may yield positive benefits. The section also shows how women’s low ownership and control over land results from discriminatory customs, inheritance practices and norms that establish men as the majority owners and decision makers in this area. The chapter concludes with some concrete and actionable policy options aimed at improving women’s access to the labour market and land ownership in Tanzania.

SIGI Country Report for Tanzania

2. Women’s economic empowerment

Abstract

Key takeaways

Access to the labour market

Women’s participation to the labour force is high at 80% in 2019. However, it remains below that of men with a gender gap of 7 percentage points, which is in line with Tanzania’s neighbour countries and lower than sub-Saharan Africa average at 12 percentage points (ILO, 2021[1]). Among respondents to the SIGI Tanzania, 63% of women were in the labour force compared to 75% of men.

Women’s high rate of labour force participation is rooted in social norms that expect women to work and support their participation in income-generating activities, albeit under the control of men.

Women’s employment, as with that of men, is concentrated primarily in the agricultural sector, reflecting the structure of Tanzania’s economy.

Non-agricultural sectors are characterised by horizontal segregation in Tanzania. Women are significantly more likely to work in the wholesale and retail sector and accommodation and food services, where they are overrepresented. Conversely, men are more likely to work in the manufacturing, construction and transportation sectors, where they are overrepresented.

Women are more likely than men to work as unpaid family workers or own-account workers. Consequently, their work often involves vulnerable and informal arrangements with limited social protection, no formal contracts and low access to benefits such as maternity leave.

Discriminatory social norms curtail women’s access to the labour market and affect their job status and positions through four main factors:

Social norms that associate men’s role with guardianship and control over women limit women’s agency and choice of activities.

Social norms and traditional forms of masculinity dictate that men should be breadwinners, while women should undertake the brunt of unpaid care and domestic work (see Chapter 3).

o Women have lower levels of education than men due to norms that favour the education of boys over girls.

Social norms that ascribe certain types of professions to women perpetuate occupational segregation.

On average, young and married men with low levels of education and from poorer households are more prone to hold discriminatory norms that curtail women’s access to labour. For instance, 79% of men without formal education believes that men should decide whether a woman can work outside the house, compared to 62% of men who went to university.

Access to agricultural land

In a context where agriculture accounts for one-third of Tanzania’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and two-thirds of total employment, women’s ownership of agricultural land is significantly lower than that of men, particularly in rural areas and regions dominated by the agricultural sector.

When women do own land, they are more likely than men to have joint ownership, which entails a lower degree of control over the land in question.

Most landowners do not possess any formal legal documentation testifying to their ownership.

Women’s low ownership of land results primarily from two types of discriminatory social norms:

Despite existing formal and/or religious laws that may protect women’s rights, informal and customary practices dictate that land belongs to men and shape inheritance practices by favouring sons over daughters and other male family members over widows.

Social norms shape intra-household dynamics and establish the man as the family’s primary decision maker.

The economic dimension is central to women’s empowerment and includes the ability to participate in the labour market and earn an income, as well as the ability to access, inherit and control productive land and financial resources. Women’s economic empowerment encompasses a wide set of issues, notably control over their own time, lives and bodies, and meaningful participation and representation in economic decision-making processes at all levels – ranging from within the household to the highest economic and political positions (UN Women, 2020[2]). While such empowerment focuses primarily on women’s capacity to make strategic choices and exercise agency in the economic sphere, it also paves the way for changes in other dimensions of their lives related to well-being, social empowerment, health and education (Kabeer, 2015[3]; Kabeer, 2009[4]).

Both Mainland Tanzania and Zanzibar have dedicated strategies and action plans to promote women’s economic empowerment. The National Strategy for Gender Development (NSGD), launched in 2006, focuses, inter alia, on women’s access to education, training and employment as well as economic empowerment and poverty eradication. In Mainland Tanzania, the policy framework for women’s economic empowerment is governed by the Five Year Development Plan (FYDP) III (2021/2022 – 2025/26) and the Tanzania Development Vision 2025. The FYDP III aims to realise the country’s vision to become a semi-industrialised middle-income country by 2025 (The United Republic of Tanzania, 2021[5]). Vision 2025 is organised around four priority areas – economic transformation, human capital and social services, governance and resilience, and infrastructural linkages – and seeks, among other goals, to ensure that by 2025 economic activities cannot be classified by gender (The United Republic of Tanzania, n.d.[6]). In Zanzibar, efforts to strengthen women’s economic empowerment are guided by the Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty – MKUZA III (2016–2020), and the Zanzibar Development Vision 2050, which prioritise inclusive and pro-poor policies with economic, social, political and environmental dimensions. Sector-specific policies and strategies further aim at promoting women’s and girls’ economic empowerment (The Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar, 2020[7]). These include Zanzibar’s Education Development Plan (2017/18 – 2021/22), the Zanzibar Land Policy (2017) and Zanzibar’s Economic Empowerment Policy (2019). The latter promotes women’s increased participation in trade sectors that are currently male-dominated but considered as drivers for economic development.

The present chapter is divided into two main sections. The first examines women’s access to the labour market in Tanzania; the second assesses women’s access to productive assets, specifically agricultural land and financial services. Both sections commence with an overview of the current situation of women in Tanzania and across the country’s 31 regions. They then explore the role played by discriminatory social institutions, notably social norms, attitudes and stereotypes, in explaining Tanzania’s unequal outcomes, specifically women’s marginalisation in the labour market, their lower job status compared to men, and their limited ownership of agricultural land and financial assets. Finally, they uncover some of the main determinants of these discriminatory social norms and attitudes that constrain the economic outcomes of Tanzanian women.

Access to the labour market

Women’s access to the labour market, and specifically to quality jobs, is an essential dimension of their empowerment. Access to the labour market provides women with an income and control over economic resources, while generating numerous positive externalities. For instance, controlling an income of their own enables women to leave a violent situation in the home, if necessary, while women’s control over economic resources increases investment in children’s education and health. The gains benefit not only women but society as a whole. Given a similar distribution of innate abilities among women and men, sex-driven labour imbalances artificially reduce the pool of skilled workers from which economic actors can draw, thereby reducing the overall economic growth of a given country (Ferrant and Kolev, 2016[8]). In this regard, increasing women’s participation to the labour market and ensuring that no structural barriers create artificial imbalances can yield significant economic gains for Tanzania. In an effort to implement different national action and priority plans to enhance women’s employment, Tanzania has supported various programmes and services (Box 2.1).

Box 2.1. Programmes and services supporting women’s access to labour markets and financial services in Tanzania

Enhancing women’s economic activity and their access to labour markets

Tanzania has implemented infrastructure programmes with the objective of reducing the time burden of domestic work that women face and increasing women’s productivity and livelihoods. These include the Rural Electrification Programme, which aims to electrify all villages in Tanzania by 2021 and the development of road networks by the Tanzania Rural Roads Agency. The latter seeks to facilitate women’s transportation and access to market places outside of their communities.

The Public Procurement Act of 2011 (amended in 2016) directly supports women’s economic activity by foreseeing an allocation of 30% of total procured services for women and youth. Specific economic groups receive support: the Zanzibar Economic Empowerment Fund (ZEEF), for example, provides financial support, entrepreneurship and marketing training for women-run vegetable and fruit projects.

Entrepreneurship among women is fostered throughout the country, for example via the Zanzibar Technology of Business Incubation Centre launched in 2015. Since its establishment, a total of 1 117 youths, the majority of whom are girls, have been trained in bakery skills, entrepreneurship, preparation of business plans, agro-processing and the preparation of soap, resulting in the establishment of 40 business companies. In Mainland Tanzania, 449 vocational training centres have been set up to enhance entrepreneurial and business skills. Vocational Trainings and Focal Development Colleges have also been established to enhance the education and skills of youth including adolescent girls.

Promoting women’s access to financial services

The 2018 amendment of the Local Government Authority Financial Act aims to ensure women’s financial inclusion and access to credit. Specifically, the newly added Section 37A requires all local government authorities to set aside 10% of their revenue collection to fund interest-free loans for women (4%), youth (4%) and persons with disabilities (2%).

In Zanzibar, the ZEEF provides soft loans to women entrepreneurs. In Mainland Tanzania, soft loans are provided to women via the Women Development Fund. The government’s contribution to the fund increased from TZS 3.4 billion (EUR 1.3 million) in 2014 to TZS 16.3 billion (EUR 6.2 million) in 2018.

The Market Infrastructure, Value Addition and Rural Finance (MIVARF) programme was implemented across the country to enhance access to formal financial services for Mainland Tanzania’s and Zanzibar’s rural population. Under the programme participants are provided with agricultural processing machines, equipment and training, as well as capacity building on agricultural or value chain issues.

Source: (Government of Tanzania, 2019[9]), Country Report on the Review and Progress made in Implementation of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action – Beijing +25, https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/CSW/64/National-reviews/United-Republic-of-Tanzania-en.pdf.

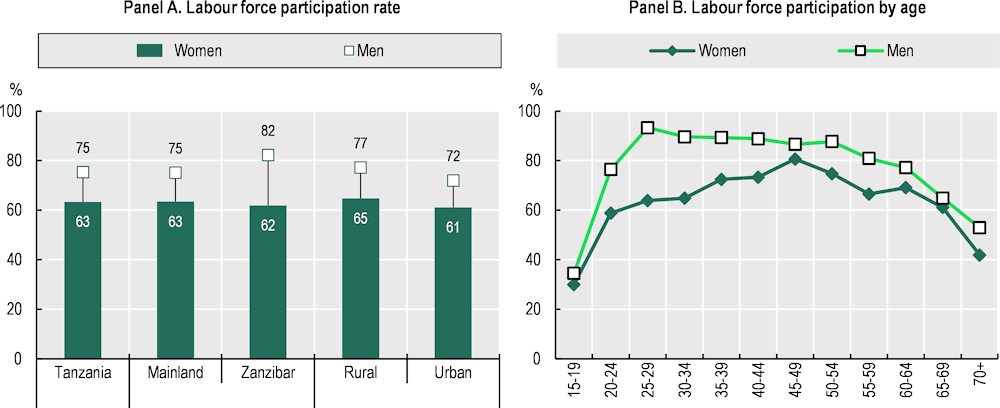

Women in Tanzania have less access to the labour market than men, remain confined to certain sectors of the economy and occupy positions of lower status

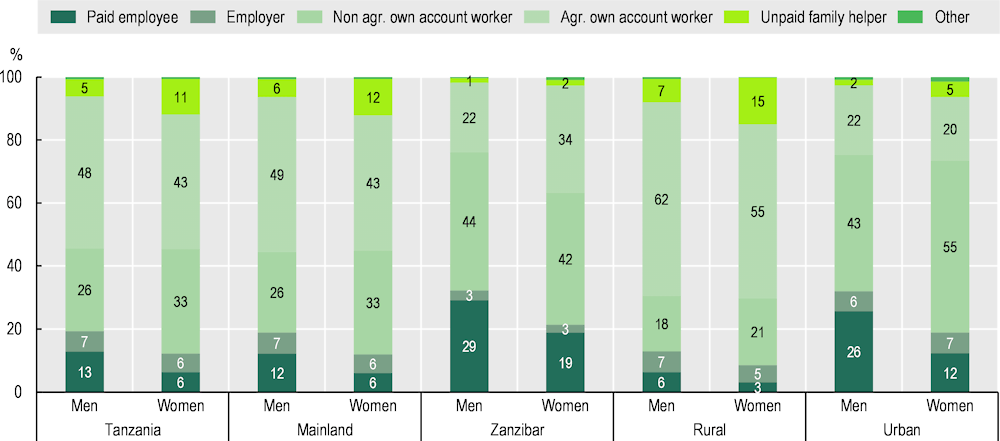

Women’s access to the labour market is high, but still lower than that of men. Controlling for various socio-demographic factors, men are significantly more likely than women to be employed.1 At the national level, 80% of working-age women are in the labour force2 and 78% are employed. In comparison, 87% of working-age men are in the labour force and 86% are employed (ILO, 2021[1]). In the SIGI Tanzania sample, 63% of working-age women are in the labour force3 and 58% are employed, compared to 75% and 69% of men, respectively. Differences are particularly marked in Zanzibar where the gender gap in labour force participation reaches 20 percentage points and the employment gap stands at 28 percentage points (Figure 2.1, Panel A).

The gender gap in labour force participation in the SIGI Tanzania sample is particularly wide among young men and women, reaching 29 and 25 percentage points for individuals aged 25 to 29 years and 30 to 34 years, respectively. However, the labour force participation gap between men and women is much smaller for older generations (Figure 2.1, Panel B). Furthermore, data show that women attain their employment peak later than men. Across all age brackets, the age at which women’s labour force participation rate is highest is older than for men. Men attain their employment peak between the ages of 25 and 29 years old. During this period, 93% of men are in the labour force and 84% are employed. In contrast, women attain their employment peak between the ages of 45 and 49 years, with 81% in the labour force and 75% employed. These distinct age profiles suggest that many women delay their entry into the labour market, most likely due to childbearing and childcare. Cross-country4 evidence indicates that marriage and increase in women’s domestic responsibilities can have a strong negative effect on women’s labour characteristics (Dieterich, Huang and Thomas, 2016[10]).

Figure 2.1. Women’s participation in the labour market is significantly lower than that of men

Note: Labour force participation is calculated for the population aged 15 years and above. Differences in men's and women's mean rate of labour force participation are significant at the 1% level in Tanzania, Mainland Tanzania, Zanzibar, rural and urban areas.

Source: (OECD, 2021[11]), SIGI Tanzania database, https://stats.oecd.org.

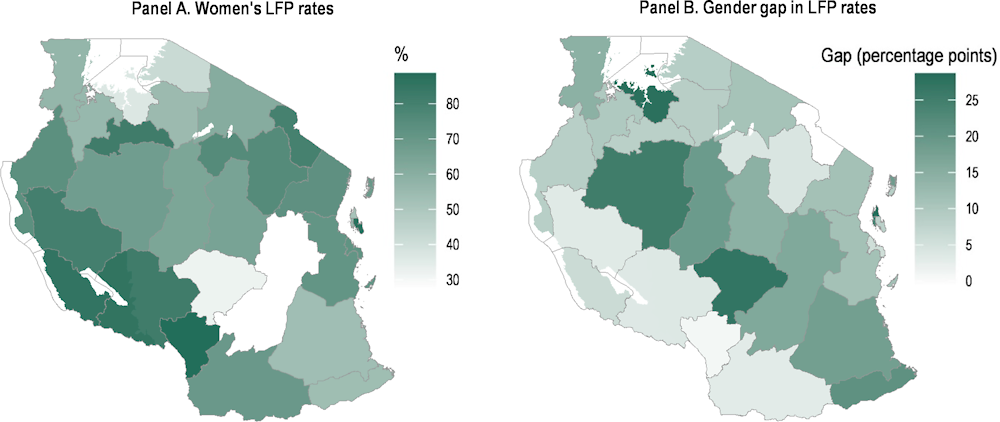

Wide variations in labour force participation exist across regions reflecting the fact that women’s inclusion in the labour market is higher in urban than in rural areas and in Mainland Tanzania than in Zanzibar. While more than 80% of women form part of the labour force in seven regions5 of Tanzania, in 11 other regions,6 this rate falls below 60% (Figure 2.2, Panel A). Incidentally, many of these 11 regions are also among those where the difference in labour force participation between men and women is the highest. For instance, in Mwanza, the gender gap in labour force participation reaches 28 percentage points. Likewise, in five other regions – Iringa, Kaskazini Unguja, Mjini Magharibi, Mtwara and Tabora – the difference in labour force participation between men and women is greater than 20 percentage points (Figure 2.2, Panel B). Women’s employment rate follows a similar pattern with more than 80% employed in some regions, while in others less than 50% of women are employed.

Figure 2.2. Women's labour force participation varies widely across Tanzania's regions

Note: The gender gap in labour force participation (LFP) rates is calculated as the difference between men's LFP rates and women's LFP rates.

Source: (OECD, 2021[11]), SIGI Tanzania database, https://stats.oecd.org.

The agricultural sector remains the main source of employment for both women and men, and accounts for about one-third of Tanzania’s GDP (World Bank, 2020[12]; World Bank, 2017[13]). At the national level, 61% of employed women in the SIGI Tanzania sample work in agriculture, compared to 65% of men. Not surprisingly, the proportion of men and women working in this agricultural sector is much higher in rural areas than in urban areas, although the proportion of the urban population reaches 30%. Overall, women engaged in agricultural activities are more disadvantaged than men and face higher constraints. They tend to own smaller plots than men, have lower levels of education, enjoy lower yields, have more limited access to markets, use less improved seeds and rely less on agricultural technologies (World Bank Group, 2017[14]). Agricultural employment is also more limited in Zanzibar where other sectors – mostly related to tourism – provide a more important source of employment for men and women.

Women’s employment is also characterised by certain specific forms of employment such as unpaid family workers or own-account workers. Women’s waged employment is extremely limited with only 6% of working women in paid employment compared to 13% of working men. Conversely, 11% of women work as unpaid family helpers compared to 5% of working men (Figure 2.3). Overall, women work primarily as own-account workers, either in the agricultural sector (43% of working women) or in non-agricultural sectors (35%). Women’s employment is slightly different in Zanzibar, due primarily to differences in the economic structure. Because Zanzibar’s economy is less dependent on agriculture and much more oriented towards tourism and services, women are less prone to work as own-account agricultural workers or as unpaid family helpers – which usually involves farming work on the household’s plots. As a result, 19% of working women are employed as paid employees – a share that is lower than that of men (29%). Conversely, the share of women working as own-account workers in the agricultural sector is lower than in Mainland Tanzania and only 2% of working women are unpaid family workers.

The extremely limited proportion of workers engaged in waged employment means that only a very small share of the working population is entitled to paid paternity or maternity leave schemes, which, by law, are provided by the employers.7 At the national level, only 4% of respondents from the SIGI Tanzania survey confirmed an entitlement to paid paternity and maternity leave, with the proportion between men and women being similar. The share of workers entitled to such leave was significantly higher in urban areas than in rural areas (9% and 2%, respectively) as well as in Zanzibar compared to Mainland Tanzania (14% and 4%, respectively). These differences directly mirror distinct situations in terms of waged and formal employment.

Figure 2.3. Women’s employment is characterised by lower forms of employment such as unpaid family worker or own-account worker

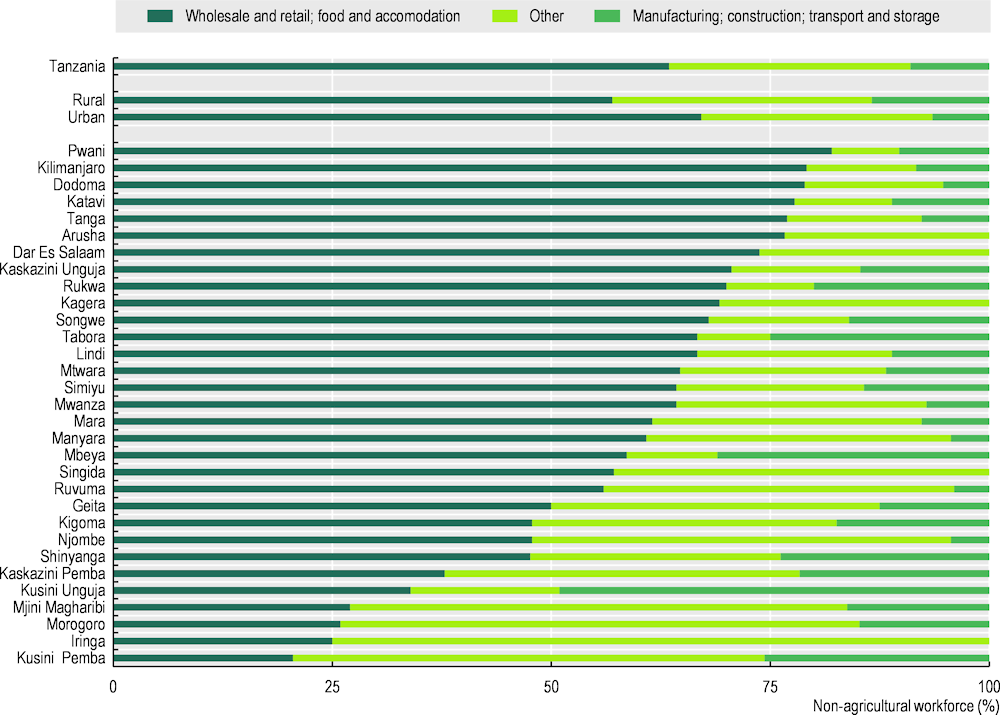

In non-agricultural sectors, horizontal segregation8 results in the concentration of women in sectors with low productivity. Controlling for various socio-demographic factors, the likelihood of women working in the wholesale and retail sector and accommodation and food services is significantly higher than for men.9 Excluding the agricultural sector, at the national level, 45% of women work in the wholesale and retail sector compared to 23% of men, while 19% of women work in the accommodation and food sector compared to 3% of men. In urban areas, in particular, 48% of women from the non-agricultural workforce are employed in the wholesale and retail sectors. Likewise, in 22 out of Tanzania’s 31 regions, more than 50% of women from the non-agricultural workforce are employed in wholesale and retail or the accommodation and food sectors (Figure 2.4). Conversely, men are more likely to work in the manufacturing, construction and transportation sectors, in which they are overrepresented compared to women. In 24 regions, the share of women from non-agricultural sectors working in the manufacturing, construction or transportation sectors is below 20% (Figure 2.4). This high horizontal segregation has notable downstream consequences since the sectors in which women are overrepresented are also those where value-added per worker is the lowest, leading to differences in economic gains between men and women – in salaries or in profits (World Bank Group, 2017[14]). In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and its socio-economic consequences, this horizontal segregation also has disproportionate effect on women’s employment as sectors such as wholesale and retail or food and accommodation services have been the hardest hit.

Figure 2.4. Horizontal segregation of the non-agricultural workforce is significant

Note: Sectors are classified by three categories. Women working in the wholesale and retail sector and the accommodation and food services sector (considered as more appropriate for women) are grouped into one category. Women working in the manufacturing, construction, transportation and storage sectors (considered as more appropriate for men) are grouped into a second category. Women working in all other sectors (considered as relatively gender neutral) are grouped into a third category.

Source: (OECD, 2021[11]), SIGI Tanzania database, https://stats.oecd.org.

Discriminatory social norms, barriers to education and traditional perceptions of gender roles affect women’s status and position in the labour market

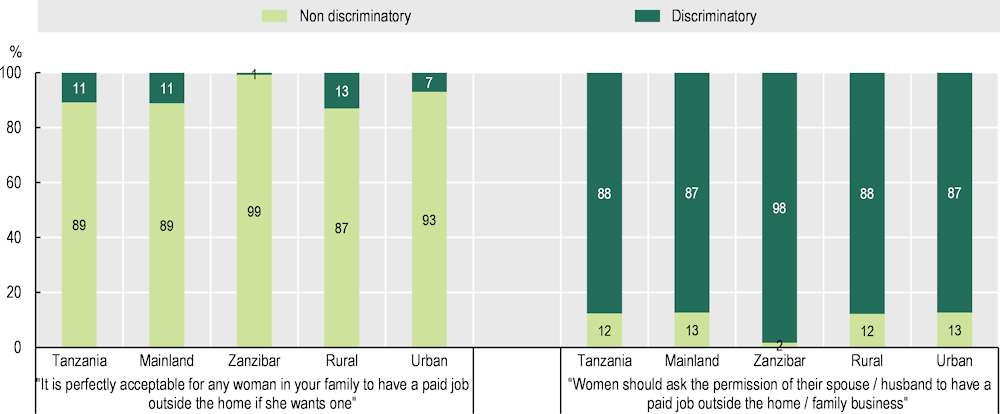

The high female labour force participation rate in Tanzania is linked to the absence of strong discriminatory social norms opposing paid work for women. However, as with many other African and/or lower middle-income countries, women in Tanzania are also responsible for unpaid care and domestic labour, while expected to contribute to the household income alongside men (Kabeer, 2015[3]). This is particularly true in rural areas and in households engaged in agricultural activities, where women often represent a valuable resource for labour-intensive activities. This dynamic results in relatively high rates of female labour force participation, with 80% of Tanzanian working-age women employed in the workforce (ILO, 2021[1]). The population appears to be fairly of women’s right to work, regardless of their place of residence. For instance, 87% of the population agrees or strongly agrees with the statement: “It is perfectly acceptable for any woman in your family to have a paid job outside the home if she wants one” (Figure 2.5, Panel A). Discriminatory attitudes relating to women’s right to work are almost non-existent in Zanzibar and only slightly higher in rural areas than in urban ones.

However, several underlying factors constrain women’s employment in Tanzania by limiting their opportunities and access to certain types of jobs. Although other factors may operate, data and analysis of the SIGI Tanzania highlight the role played by the four following factors in limiting women’s labour outcomes:

Social norms, and notably norms of restrictive masculinities, associate men’s role with guardianship and control over women.

Social norms and views on traditional gender roles in the household dictate that men should be breadwinners, while women should undertake the brunt of unpaid care and domestic work.

Women have lower levels of education than men partly due to a combination of multiple discriminatory social norms, including girl child marriage, adolescent pregnancies and long-established trends and choices at the household level favouring the education of boys over girls.

Social norms ascribe certain types of professions to women.

Social norms that associate men’s role with guardianship and control over women limit women’s agency

In Tanzania, social norms dictate that men should control whether a woman is allowed to work outside the household. Discriminatory attitudes restricting women’s free choice to have a job are widespread, with 88% of the population agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statement “Women should ask the permission of their spouse/partner to have a paid job outside the home/family business” (Figure 2.5, Panel B). This share reaches 98% in Zanzibar, where qualitative research has found that cultural and religious norms do not prohibit a woman from seeking work as long as she has the permission of her husband – or her parents if she is not married (Mbuyita, 2021[15]).

Adherence to such social norms associated with men’s guardianship of the household and control over women reinforces existing gender inequalities in the public and economic spheres and severely constrains women’s agency (OECD, 2021[16]). These restrictive norms go beyond men’s control over women’s economic activity. For instance, 93% of the population who believe that women should ask permission from her husband or partner to have a paid job outside the home, also hold the view that a woman should seek permission to travel to another city or abroad. Likewise, 87% are of the opinion that a woman should ask permission to visit her family. Restricting women’s mobility may also serve as a means to maintain traditional gender divisions of labour, ensure that women stay at home and preserve control over women’s sexuality by limiting external social contact (Porter, 2011[17]).

Figure 2.5. Social norms support women’s labour force participation but dictate that women should ask permission

Note: Discriminatory attitudes regarding women's ability to work outside the household are measured as the share of the population strongly disagreeing or disagreeing with the statement “It is perfectly acceptable for any woman in your family to have a paid job outside the home if she wants one.” Discriminatory attitudes regarding women having to ask permission to work outside the household are measured as the share of the population strongly agreeing or agreeing with the statement “Women should ask the permission of their spouse/husband to have a paid job outside the home/family business.”

Source: (OECD, 2021[11]), SIGI Tanzania database, https://stats.oecd.org.

Social norms view men as breadwinners and dictate that women should undertake the brunt of unpaid care and domestic work

In Tanzania, traditional social norms also dictate that men are the breadwinners of the household – a salient characteristic of being a “real” man that persists across time, space and cultures (OECD, 2021[16]). Despite the significant shares of women participating in paid labour, norms associating masculinities with paid work and the role of financial provider remain strong: 92% of the population considers that a “real man” should be the breadwinner. Likewise, a large share of the population (16%) considers that working for pay should be the exclusive responsibility of a man, whereas only 6% of the population considers it the exclusive responsibility of women – and 78% perceives it as a shared responsibility. In Zanzibar and rural areas, the share of the population that considers working for pay to be the sole responsibility of men is 20% and 17%, respectively.

These restrictive norms of masculinities have a significant impact on whether individuals believe that men should have priority in terms of employment or not. Individuals considering that paid work should be a man’s exclusive responsibility or that a “real man” should be the breadwinner are significantly more prone to believe that men should have priority over women where employment is concerned.10

At the same time, social norms and views on traditional gender roles in the household dictate that women should undertake the brunt of unpaid care and domestic work (see Chapter 3), with women’s place largely believed to be in the household. Focus group discussions in Zanzibar highlighted the view that women are expected to stay at home, give birth, and take care of the husband and family (Mbuyita, 2021[15]). At the national level, women undertake the lion’s share of unpaid care and domestic work, spending three times more time on unpaid care and domestic work than men. Moreover, their unpaid work burden consists largely of basic and routine household tasks such as cleaning, cooking and taking care of the children (see Chapter 3).

This has consequences for women’s choices regarding the labour market. Although women undertake the majority of unpaid care and domestic work, social norms in Tanzania also expect them to work, which translates into a double burden of paid and unpaid work. As a result, women undertake, on average, 4.4 hours of unpaid care and domestic work per day compared to 1.4 hours for men and also work 5 hours per day daily compared to 6 hours for men. In total, women spend 9.4 hours every day on unpaid and paid work compared to 7.4 hours for men (see Chapter 3). At the global level, women’s disproportionate burden of unpaid care and domestic work is closely associated with their low participation in the labour market, notably by constraining the allocation of their time, their mobility and their employment opportunities (OECD, 2021[18]; OECD, 2019[19]). However, in Tanzania, no association has been found between women’s labour force participation and the female-to-male ratio of unpaid care and domestic work. Even in regions where the sharing of household tasks is the most unequal, women’s participation in the labour market remains high. This double hardship often requires women to make labour choices that allow them to remain flexible in regard to their household duties, such as working in the informal sector or close to the home.

Women’s lower levels of education limit their access to quality jobs and formal employment

Women’s employment is constrained by their low level of education. In Tanzania, women’s likelihood of becoming part of the workforce or being employed rises significantly as their educational level increases.11 While 59% of women with no formal education are in the workforce, this share increases to 65% and 85%, respectively, for those with a primary education and a university degree. Yet, women’s level of education remains significantly lower than that of men. At the national level, 20% of women have no formal education, compared to only 9% of men. In contrast, 11% of women have completed secondary education compared to 17% of men.

These differences in educational attainment between men and women stem from multiple factors, including girl child marriage, adolescent pregnancies and long-established trends and choices at the household level favouring the education of boys over girls. In Tanzania, girls who are married young are more likely to achieve lower educational attainment and in many instances, child marriage may lead to the interruption of girls’ schooling (see Chapter 3). Because it is unlawful in Mainland Tanzania for any person to marry a girl who attends primary or secondary school, families that desire to marry their daughters might be tempted to remove them from school before organising the marriage. A husband may also oppose his young bride attending school and may expect her to care for the household instead. At the same time, girl child marriage significantly increases the likelihood of adolescent pregnancies (see Chapter 3). Constrains resulting from adolescent pregnancies and related to childrearing can impede girls from continuing their education. Qualitative research also uncovers that past behaviours that only started to change recently and that denied girls the opportunity to attend school have contributed to a high number of women having no or low levels of formal education today (Mbuyita, 2021[15]). These low levels of education have profound impacts on women’s ability to join the formal public or private sectors.

Social norms ascribing certain types of professions to women perpetuate labour segregation

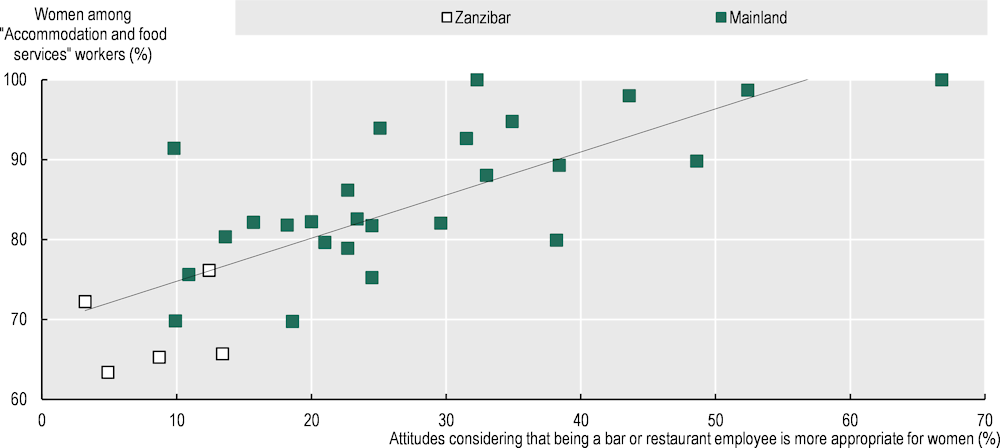

Social norms that ascribe certain types of professions to women perpetuate the horizontal and vertical segregation of Tanzania’s labour market. Biases and stereotypes regarding the type of job that may be fit or appropriate for a woman or a man tend to confine women to certain sectors or positions. For instance, results at the regional level show that the share of the population who believes that being a bar or a restaurant employee is a job more appropriate for women, is reflected in the larger share of women among workers in the “Accommodation and food service” sector (Figure 2.6).

Figure 2.6. Gendered views and stereotypes regarding jobs and occupations lead to horizontal segregation

Note: The figure shows the correlation between the share of women among workers in the “Accommodation and food services” sector and the share of the population considering that being a bar or a restaurant employee is more appropriate for women. Data presented are fitted values from an OLS regression with women's share among workers in the “Accommodation and food services” sector as the dependent variable. Attitudes considering that being a bar or a restaurant employee is more appropriate for women is the main independent variable. Coefficient and marginal effects are significant at 10%. Control variables include the urbanisation rate, localisation in Mainland or Zanzibar, and wealth levels.

Source: (OECD, 2021[11]), SIGI Tanzania database, https://stats.oecd.org.

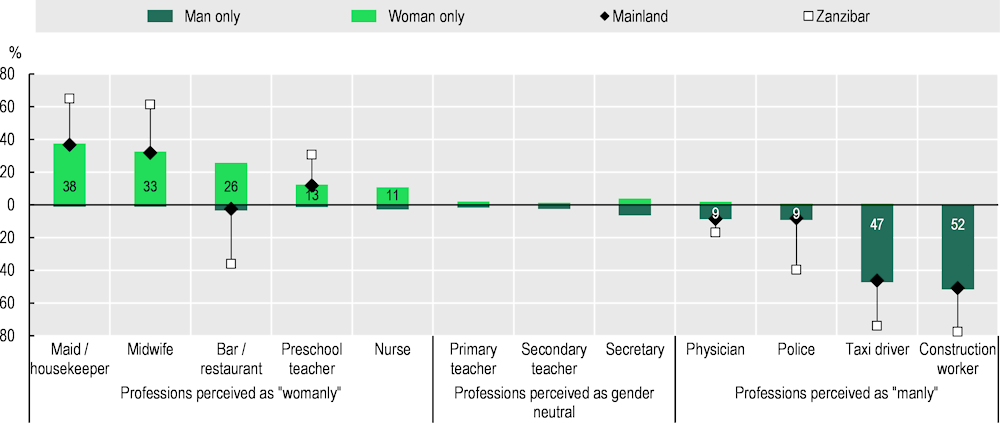

As in many cultures and countries across the world, views on jobs and occupations are highly gendered in Tanzania. On the one hand, some jobs are perceived as “womanly”. For instance, 38% of the population considers being a maid or a housekeeper to be a job for women, 61% believe that the profession may be appropriate for both men and women, and only 1% consider it to be a job for men. Likewise, 33% and 26% of the population, respectively, consider that being a midwife and working in a bar or a restaurant to be more appropriate jobs for women. On the other hand, some jobs are perceived as “manly”. More precisely, 47% and 52% of the population, respectively, believe that being a taxi driver and working in construction are jobs more appropriate for men. Less than 1% of the population thinks that these occupations are more appropriate for women (Figure 2.7). These patterns highlight a defining feature of restrictive masculinities in Tanzania that is also found in many other cultures and countries. The social definitions of jobs as either “manly” or “womanly” correspond not only to the sex to which these jobs typically apply but also to sex-based associations about the traits that make an individual suited for the work (OECD, 2021[16]; Buscatto and Fusulier, 2013[20]). In this regard, jobs such as fishers, taxi drivers, masons and carpenters are viewed as more suitable for men based on the belief that physical strength is a masculine trait. Conversely, occupations such as midwives, nurses, housekeepers and preschool teachers are seen as more appropriate for women based on their association with care and attentiveness to others, which are typically viewed as feminine traits (OECD, 2021[16]).

These stereotypes are not uniform across Tanzania and tend to be stronger in Zanzibar. For instance, 65%, 61% and 31% of the population there consider that being a maid or housekeeper, a midwife or a preschool teacher, respectively, is more appropriate for women. Perceptions of certain jobs as more suited to men are also more polarised. For example, about three-quarters of Zanzibar’s population considers that being a taxi driver and working in construction are jobs more appropriate for men (Figure 2.7). Interestingly, the case of Zanzibar shows that social norms may vary significantly across places. Culture and customs shape how people associate certain traits with certain occupations, resulting in opposite results for the same norms. While 26% of the population in Mainland Tanzania considers that being a restaurant or bar employee is more appropriate to women, this share drops to 7% in Zanzibar. Conversely, while only 3% of Mainland Tanzania’s population perceives working in bars or restaurants as “manly”, 36% of Zanzibar’s population believes that this type of work is more appropriate for men (Figure 2.7).

Figure 2.7. Certain jobs are highly gendered

Note: The figure presents the share of the population that considers certain jobs to be more appropriate for women only or for men only. Shares considering that a given job is more appropriate for women only shown in the top half of the figure; shares considering that a given job is more appropriate for men only are shown in the bottom half. Mainland – Zanzibar differences are indicated only for jobs and sizes that are relevant. The difference between the shares considering a job to be more appropriate for women or man only is the share of the population that considers a job appropriate for both men and women.

Source: (OECD, 2021[11]), SIGI Tanzania database, https://stats.oecd.org.

The consequences of these stereotypes and opinions are far reaching, as jobs deemed more appropriate for women also have lower levels of income than those traditionally held by men. During focus group discussion, many female respondents stated that only a few women currently hold professional positions (e.g. medical doctors, engineers, lecturers, teachers, etc.) or are engaged in types of work that in the past used to be perceived as masculine (e.g. construction and mining) (Mbuyita, 2021[15]). However, value-added per worker in sectors such as utilities, construction or finance in Tanzania is found to be much higher than in sectors such as commercial activities, including wholesale and retail (World Bank Group, 2017[14]). As a result, stereotypes regarding the sector or type of jobs deemed appropriate for women tend to naturally orient women towards low productivity sectors characterised by lower wages, perpetuating women’s economic disempowerment.

Married men and young men with low levels of education and from poorer households are more likely to hold discriminatory norms that curtail women’s access to labour

In the SIGI Tanzania sample, men were more likely to hold discriminatory attitudes that constrain women’s participation in the labour market. More specifically, men are less likely than women to consider that it is perfectly acceptable for a woman to pursue a paid job outside of the home, and are also more likely than women to think that women should ask their partner or spouse for permission if they want to have a paid job outside of the home or family business. In addition, men are also more likely to consider that they should take decisions regarding women’s economic activity outside the house (Table 2.1).

Table 2.1. Determinants of discriminatory attitudes curtailing women’s labour participation

Marginal effects and significance of key characteristics on discriminatory attitudes

|

|

Dependent variable: discriminatory attitudes regarding the statements |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(i) |

(ii) |

(iii) |

||

|

“It is perfectly acceptable for any woman in your family to have a paid job outside the home if she wants one” |

“Women should ask the permission of their spouse or partner to have a paid job outside the home or family business” |

“Men should decide whether a woman can work outside the house” |

||

|

Independent variables |

||||

|

Being a woman |

||||

|

Living in urban areas |

o |

o |

o |

|

|

Age |

||||

|

Age squared |

||||

|

Education (omitted: no formal education) |

Primary incomplete |

o |

o |

|

|

Primary complete |

o |

o |

||

|

Secondary complete |

o |

|||

|

University complete |

o |

o |

||

|

Marital status (omitted: married) |

Living together |

o |

o |

o |

|

Single |

||||

|

Size of the household |

o |

o |

||

|

Wealth (omitted: 1st quintile) |

2nd quintile |

o |

o |

o |

|

3rd quintile |

o |

o |

||

|

4th quintile |

o |

|||

|

5th quintile |

o |

|||

Note: The table reports the sign of independent variables from three probit models where the dependent variables are (i) the share of the population who strongly disagrees or disagrees with the statement “It is perfectly acceptable for any woman in your family to have a paid job outside the home if she wants one”; (ii) the share of the population who strongly agrees or agrees with the statement “Women should ask the permission of their spouse or partner to have a paid job outside the home or family business”; and (iii) the share of the population who strongly agrees or agrees with the statement “Men should decide whether a woman can work outside the house”. Additional control variables include regional dummies. o = no significant effect; = a significant positive effect; = a significant negative effect.

Source: (OECD, 2021[11]), SIGI Tanzania database, https://stats.oecd.org.

Age, marital status, education and wealth are key determinants of discriminatory social norms and attitudes. For all three attitudes measured, the likelihood of holding discriminatory attitudes towards women’s access to labour seems to decrease as age increases. Marital status also appears to constitute a strong determinant of holding discriminatory attitudes: individuals who are single are significantly more likely to hold attitudes favourable to women’s access and labour market participation compared to those who are married or living together (Table 2.1).

The likelihood of holding discriminatory social attitudes decreases with increasing educational levels. Individuals with higher educational attainment are more likely to find it acceptable for a woman to have a paid job outside the home, as well as to disagree with the fact that men should take decisions over women’s economic activity outside the house (Table 2.1). This effect becomes stronger as education increases and is found to be strongest among individuals with secondary education and/or university education level. For instance, 95% of individuals who have completed secondary education find it acceptable for a woman to have a paid job outside the household if she wants, compared to 83% for individuals with no formal education. Likewise, 80% of individuals with no formal education believe that men should decide whether a woman can work outside the house, compared to 69% and 59% of individuals with complete secondary schooling and university-level education, respectively.

Similar to education, individuals from wealthier households are less likely to hold discriminatory attitudes that restrict women’s access to the labour market. This is particularly the case in regard to acceptance of women having a paid job outside the house (column (i) in Table 2.1) and not believing that men should take decisions over women’s economic activity (column (iii) in Table 2.1). In both cases, the effect is strongest for individuals belonging to the two highest wealth quintiles. These results are not surprising given the strong interlinkages between education and wealth.

Access to agricultural land

In Tanzania, the agricultural sector continues to account for about one-third of the country’s GDP and around two-thirds of employment for both men and women (World Bank, 2020[12]; World Bank, 2017[13]). Against this backdrop, women’s ownership of productive assets such as agricultural land is critical to their economic empowerment. The essential link between livelihoods, food security, nutrition and agriculture in Tanzania puts access to and control over land at the heart of poverty eradication and sustainable development. In the context of climate change and increased risks of adverse climate episodes, such as droughts or floods, secured ownership of land becomes vital to limit women’s vulnerability to the socio-economic effects of these events. At the same time, female land owners can become active and effective agents and promoters of adaptation and mitigation of climate change, notably through knowledge and expertise (Merrow, 2020[21]; Osman-Elasha, n.d.[22]).

Women’s access to and ownership of land may also have important consequences for other aspects of their economic empowerment such as access to financial services and the ability to seek and obtain credit. The gender gap persists in the banking system – which remains heavily fragmented and weak in terms of capital – with 45% of women having a bank account, microfinance account or mobile money services compared to 57% of men (OECD, 2021[11]). Improving women’s access to agricultural land and providing them with secured land rights would help strengthen their access to financing, with positive spillovers for business creation and economic growth.

In this context, evidences show that women continue to face severe constraints. It is worth noting, however, that some legal obstacles have recently been abolished. In 2019, Tanzania adopted the Village Land Act and the Land Act which, respectively, govern the management and administration of land collectively owned by villages and allocated to individuals, and the management and administration of general land. The Village Land Act establishes clearly that customary law or decisions regarding land held under customary tenure are void if they deny women’s lawful access land ownership (Government of Tanzania, 2018[23]; Government of Tanzania, 2018[24]). Nevertheless, conflicts with other legal instruments may arise as the National Land Policy of 1997 clearly reinforces customary practices of property ownership which, in most cases, discriminate against women and girl children. In particular, the National Land Policy states that inheritance of clan land will continue to be governed by custom, and states that this is not contrary to the Constitution (Government of Tanzania, 1997[25]). Other obstacles are structural in nature and relate to representation in decision-making bodies. At the village level, the dominance of men in local governance structures such as land tribunals and councils, which are instrumental in land adjudication processes, lessens women’s voice in important decisions. Women are also frequently excluded from specific processes related to land use planning, parcelling and land registration, which effectively obstructs their involvement in the overall process of land administration and the provision of land titles. Heavy bureaucratic land administration processes associated with high related costs and extended periods of time may also impose limitations on women’s ownership (UN Women, 2018[26]).

Women’s low ownership of agricultural land and related decision-making power affects their economic empowerment and food security

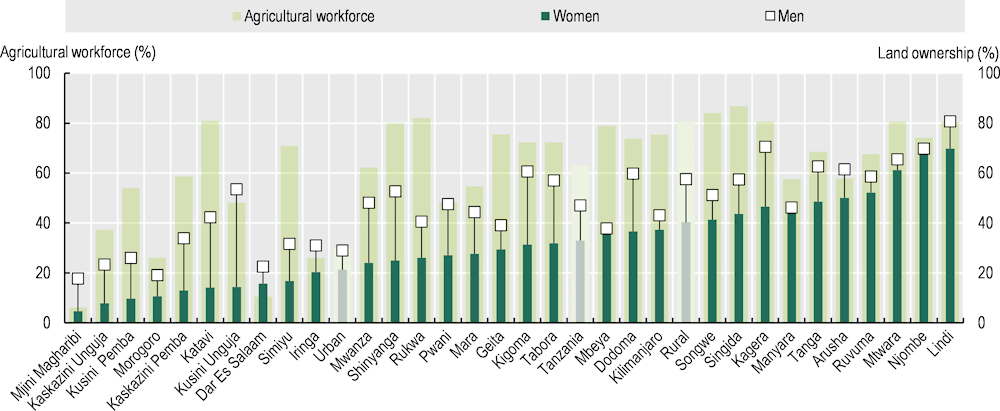

Women’s ownership of agricultural land is significantly lower than that of men. At the national level, controlling for various socio-demographic factors, men are significantly more likely than women to own agricultural land:12 33% of women own agricultural land compared to 47% of men. This disparity translates into a gender gap of 14 percentage points.

Differences in land ownership between men and women are larger in rural areas and in regions where the majority of the population relies on agriculture. In rural areas, where 81% of the workforce works in the agricultural sector – and 78% of employed women – the gender gap in agricultural land ownership reaches 17 percentage points. This gender gap is found systematically across all regions of Tanzania and reaches more than 20 percentage points in 10 regions.13 It is particularly elevated in regions where a large share of the population relies on agriculture as the main source of employment. For instance, in Katavi, Shinyanga and Kagera, the gender gap reaches 28, 28 and 24 percentage points, respectively. In these regions, more than 80% of the labour force works in the agricultural sector (Figure 2.8).

Figure 2.8. Women's ownership of agricultural land is significantly lower than that of men

Note: “Agricultural workforce” (left-hand axis) represents the share of the total workforce employed in the agricultural sector.

Source: (OECD, 2021[11]), SIGI Tanzania database, https://stats.oecd.org.

Women are significantly more likely than men to share ownership of agricultural land with someone else, rather than being the sole owner. Whether women and men share the ownership of agricultural land with someone else, and with whom this ownership is shared, is of critical importance as the form ownership takes often has important repercussions for the ability of individuals to make meaningful decisions regarding the land owned. To obtain a clearer picture, the SIGI Tanzania collected information on land ownership, with a focus on whether agricultural land was owned solely or jointly held with someone else (Box 2.2). Among individuals that own land, 56% of men own agricultural land on their own compared to 45% of women. A similar proportion of men and women (respectively 8% and 7%) own land both solely and jointly with someone else. Finally, while 36% of men own land jointly with someone else, this share reaches 48% for women. For both men and women, in 90% of the cases where agricultural land is jointly owned with someone else, the ownership is shared with the spouse.

Box 2.2. How the SIGI Tanzania measures agricultural land ownership

Ownership of agricultural land is a complex phenomenon to measure. To capture a full picture of land ownership, the data gathered must extend beyond the simple fact of whether individuals own or do not own a plot of land. To obtain a more granular picture of agricultural land ownership, it is essential to collect information on characteristics related to the surface owned, the way the land is used, the number of different owners, the identities of those who can make decisions over its use and so forth.

Sole ownership vs joint ownership

Knowing whether women and men share ownership of agricultural land with someone else, and with whom this ownership is shared, is critical. The SIGI Tanzania collected this information by asking successively whether respondents (i) owned agricultural land on their own, and (ii) owned agricultural land jointly with someone else. For each of these types of ownership, the survey contained specific follow-up questions related to the possession of a formal ownership document, the identity of those who have the right to sell or rent the land, and more.

This approach enabled statistics on land ownership to be disaggregated by three types of ownership.

Individuals who are the sole owners of all agricultural land plots they own.

Individuals who co-own agricultural land jointly with at least one other official owner.

Individuals who own agricultural land solely and jointly with someone else.

Land in Tanzania is obtained through three main channels – purchase, inheritance or allocation by the family, clan or traditional authorities. A large amount of land in Tanzania is subject to customary tenure systems and is held in village settings (UN Women, 2018[26]). Data from the SIGI Tanzania show that, on average, around 40% of the agricultural land has been purchased, 30% has been inherited, 20% has been allocated by the family, clan or another traditional authority, and the rest has been acquired through other means. The importance of inheritance as a channel of acquisition is slightly greater in Zanzibar where 38% of the owners of land held alone (43% of women) and 65% of the owners of land held jointly (61% of women) had inherited the agricultural land they owned. The modes of acquisition are similar for both land owned alone and land owned jointly.

A lack of formal documentation may leave individuals, and especially women, vulnerable to land grabbing and other unlawful practices. At the national level, only 38% of agricultural landowners have a formal document that can legally prove their ownership of the land. The proportion is similar for men and women owners, regardless of whether they live in urban or rural areas. This lack of formal documentation exposes owners of agricultural land to several risks, including the enforcement of customary and traditional practices to the disadvantage of women. Women may be particularly vulnerable to these threats as they have less means to uphold their rights. For instance, women’s limited representation on land tribunals and councils in charge of land adjudication processes and resolving conflicts at the village level may weaken their ability to ensure their rights are upheld (UN Women, 2018[26]). Likewise, legal contradictions between the Village Land Act and the National Land Policy limit women’s ability to inherit clan land on equal terms as men (Government of Tanzania, 2018[24]; Government of Tanzania, 1997[25]).

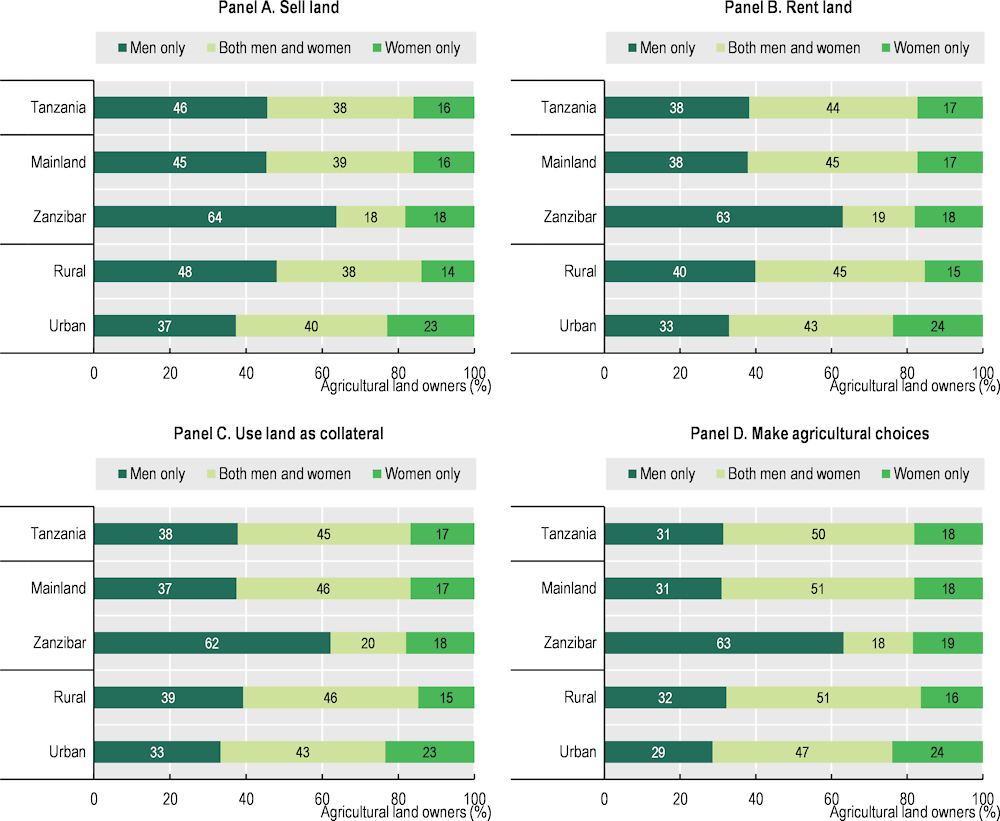

Beyond ownership, women’s control over the use of land and the ability to make decisions related to its administration remain limited in many parts of Tanzania. Among individuals who own agricultural land, and regardless of the sex of these owners, nearly half reported that only a man had the right to sell the land in question. Some 38% of owners reported that both men and women had the right to sell the land, while 16% reported that only female individuals retained this right (Figure 2.9). These discrepancies between men and women are similar for other types of actions related to land, including renting, using the land as collateral and making agricultural choices. They highlight the degree to which less autonomy is given to women in the administration of land and assets. Moreover, even in instances where both men and women have the right to make critical decisions such as selling or renting, intra-household dynamics and power imbalances between men and women may undermine their ability to have equal decision-making power.

The discrepancies also reflect existing differences between men and women in terms of land ownership as well as whether land is owned alone and/or jointly. In this regard, Zanzibar stands out primarily because (i) the proportion of women among agricultural landowners is much lower at 26%, which automatically drives down the opportunities for women to be among those with decision-making power over land; and (ii) individuals owning agricultural land are much more likely to own land alone than jointly, which increases the opportunities for men to be exclusive decision makers. Among individuals that own land in Zanzibar, 81% of men and 73% of women own agricultural land on their own.

Figure 2.9. Women’s control over the use of land remains limited

Note: For each type of action (sell, rent, use as collateral and make agricultural choices), the figure identifies those who have the right to make such actions. The sample is the entire population declaring that they own agricultural land. “Make agricultural choices” implies being the decision maker regarding input use, crop choices and the timing of crop activities for the agricultural land owned.

Source: (OECD, 2021[11]), SIGI Tanzania database, https://stats.oecd.org.

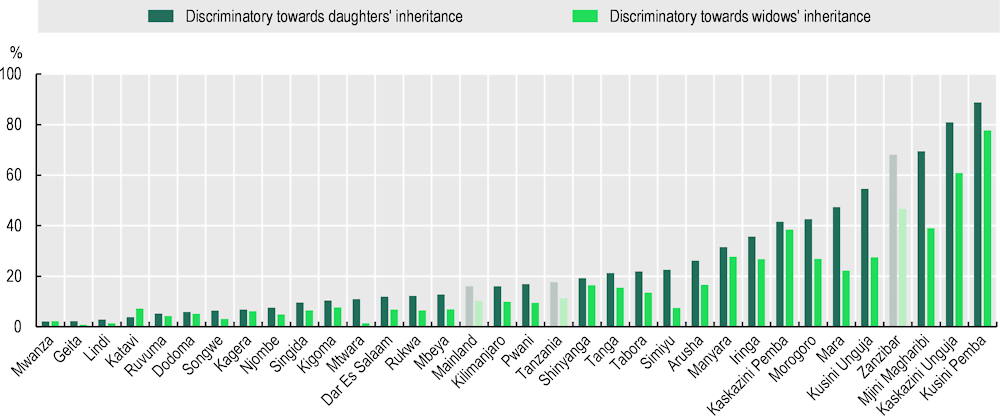

Women’s low ownership of land stems from customs that associate ownership with men and condone discriminatory inheritance practices

The Tanzanian population surveyed by the SIGI Tanzania supports equal ownership and decision-making power over agricultural land. More than 90% of Tanzania’s population believes that women and men should have equal access to agricultural land ownership and equal decision-making power in this regard. However, discriminatory attitudes restricting women’s inheritance rights are still widespread. At the national level, 18% of the population believes that a daughter should not have the same opportunities and rights as a son to inherit from land assets. Likewise, 11% of the population holds the view that a widow should not have equal rights and opportunities as a widower in regard to land inheritance. The prevalence of these discriminatory attitudes varies greatly across Tanzania’s regions. While almost non-existent in certain parts of the country, they are very high in other regions and in Zanzibar where 68% and 47% of the population deny equal inheritance rights to daughters and widows, respectively (Figure 2.10).

Figure 2.10. Discriminatory attitudes restricting women’s rights to inheritance of agricultural land vary greatly across regions

Note: Discriminatory attitudes regarding daughters' inheritance rights are measured as the share of the population disagreeing with the statement: “A daughter should have equal opportunity and rights as a son towards inheritance of land assets”. Discriminatory attitudes against widows' inheritance rights are measured as the share of the population disagreeing with the statement: “A widow should have equal opportunity and rights as a widower towards inheritance of land assets”.

Source: (OECD, 2021[11]), SIGI Tanzania database, https://stats.oecd.org.

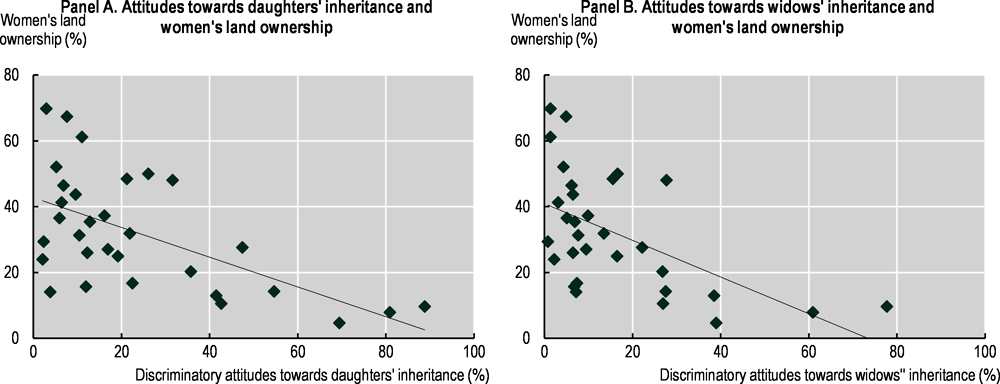

These discriminatory social norms pose a critical challenge to women’s ownership of agricultural land and partly explain their limited access to this important resource. Any sex-based limitations placed on any of the three main channels of acquisition of land in Tanzania – purchase, inheritance or allocation – likely decreases the ability of women to acquire and own agricultural land. In Tanzania, discriminatory social norms limiting women’s inheritance of land and favouring sons over daughters – or other men from the family over widows – are significantly associated with lower rates of land ownership among women (Figure 2.11).14 They reflect the fact that inheritance practices provide more chances and opportunities for men than women to acquire land, except in a few circumstances where a woman is the only heir (Mbuyita, 2021[15]). Participants in qualitative study groups all described similar cases, particularly in rural areas, where a woman whose husband passes away would leave the home without receiving anything as her share, regardless of the number of years spent living and earning with her husband. Very often, male relatives from the deceased husband such as in-laws or uncles take the lead in deciding what happens to the property and assets, especially when no children are left behind, or when the children are minors. This results in widows and daughters rarely receiving any significant or fair share of the distributed property (Mbuyita, 2021[15]). As inheritance disputes are often regarded as private family matters, the police and the judicial system rarely get involved, which often leaves widows and daughters with little legal protection (Ezer, 2006[27]).

Figure 2.11. Discriminatory social norms denying women’s inheritance rights limit their ability to own land

Note: Panel A and B present fitted values from two OLS regressions performed at the regional level on the share of women who own agricultural land. The main independent variables are the share of the population holding discriminatory attitudes towards the equal inheritance rights of daughters (Panel A) and the share of the population holding discriminatory attitudes towards the equal inheritance rights of widows (Panel B). Control variables include the urbanisation rate and localisation in Mainland Tanzania or Zanzibar. Coefficients and marginal effects of discriminatory attitudes towards the equal inheritance rights of widows of daughters are significant at 10%.

Source: (OECD, 2021[11]), SIGI Tanzania database, https://stats.oecd.org.

These attitudes towards inheritance are upheld by social norms and traditional views dictating that land belongs to men. In the context of a largely agriculture-based economy, land is a critical asset that may bring not only wealth but also political and social power. Historically, land ownership accompanies political power, especially in agrarian societies (Holcombe, 2020[28]). Ownership of land is also essential to access financing as it usually serves as the primary source of collateral for credit and as means to save for the future. Against this backdrop, qualitative research in Tanzania has shown that men perceive themselves as the rightful candidates within the family to own land and other assets. Furthermore, sons are valued as the only members of the family able to become leaders and to perpetuate the clan’s name. Consequently, as explained by a participant in focus group discussions, “it is the right of men to own everything on behalf of the family” (Mbuyita, 2021[15]).

Unequal inheritance practices for assets and properties also highlight issues related to the distribution of assets within married couples. Individuals, and particularly men, tend to justify their opinion in favour of unequal inheritance rights for widows on the basis that, in many instances, on entering marriage their husband already owns the assets later included in the division of the inheritance upon his death (Mbuyita, 2021[15]).

Women’s limited control over land stems from norms shaping intra-household dynamics and establishing the man as the primary decision maker

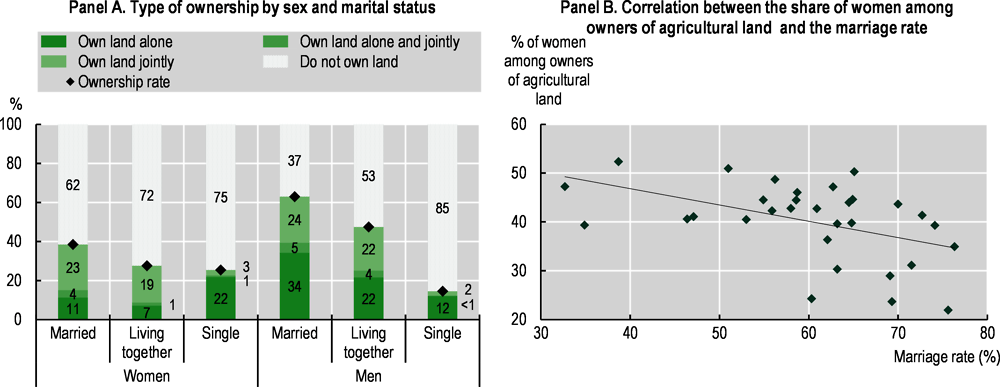

Marriage constitutes a strong determinant of women’s ownership of agricultural land. Controlling for various socio-demographic characteristics, married women are much more likely than single women to own agricultural land.15 While 26% of single women own agricultural land, this share rises to 29% for unmarried women living together with a partner and to 38% for married women. Moreover, as the marital status of individuals changes, the form of ownership evolves. For instance, whereas 22% of single women own agricultural land individually – meaning that the land is owned solely by them – only 11% of married women are sole owners. Conversely, the share of women jointly owning land with someone else increases from 3% for single women to 23% for married women (Figure 2.12, Panel A). This increase in joint ownership is mirrored among men. Data show clearly that the share of men jointly owning agricultural land increases considerably with marriage.

Figure 2.12. Marital status strongly influences the level and type of women's ownership of agricultural land

Note: Panel B shows presents the fitted values from an OLS regression at the regional level with the share of women owners of agricultural land sector as the dependent variable. The share of the population who is married is the main independent variable. Coefficient and marginal effects are significant at 5%.

Source: (OECD, 2021[11]), SIGI Tanzania database, https://stats.oecd.org.

However, unlike among women, this increase in joint ownership is not accompanied by a decrease in men’s individual ownership. On the contrary, men’s individual ownership rate increases from 12% for single men to 34% for married ones (Figure 2.12, Panel A). The results and the inverse dynamics between men and women suggest that as women marry, formal ownership of agricultural land is partly transferred to their husband, switching their status of ownership from “alone” to “jointly”. Once married, any new land acquired is owned by the husband, to the detriment of the married woman. A different way to look at this phenomenon is to observe whether the share of women among those that own agricultural land evolves as the marriage rates increases. Results at the regional level show distinctly that as the share of married women increases, the share of women among agricultural owners significantly and largely decreases16 (Figure 2.12, Panel B). As men continue to consider land ownership their prerogative, focus group discussions suggest that many married women may resort to buying land secretly without their husband’s knowledge, in order to retain control and ownership (Mbuyita, 2021[15]).

Discriminatory social norms restricting women’s access to land ownership are primarily upheld by men and poorer individuals with a low educational background

Women are less likely to condone discriminatory attitudes that restrict women’s ownership of and control over agricultural land. Men are significantly more likely than women to think that widows or daughters – compared to widowers and sons – should not enjoy equal inheritance rights in relation to land assets. The effect of being a man on holding discriminatory attitudes is even stronger in regard to women’s equal access to and decision-making power over land assets. Age also seems to matter. Results show that as age increases, individuals are more likely to be in favour of men and women enjoying equal access or decision-making power over land. However, younger individuals are more likely to support granting daughters and sons the same inheritance rights to land assets (Table 2.2).

Education and wealth are key determinants of whether an individual holds discriminatory social norms and attitudes curtailing women’s ownership of agricultural land, particularly in relation to the inheritance rights of daughters and widows. Individuals who have completed at least primary education are more likely to believe that widows and widowers as well as daughters and sons should have equal rights and opportunity to inherit land assets. They are also less likely to hold discriminatory attitudes towards women’s and men’s equal decision-making power over land. The effect of primary education is particularly strong for both attitudes towards equal inheritance and towards equal decision-making power (Table 2.2). A similar relationship can be observed between wealth and attitudes on women’s inheritance rights, which is consistent with the strong interlinkages between education and wealth. Wealthier individuals – those belonging to the fourth or fifth wealth quintile – are more likely to be in favour of equal inheritance rights between men and women, and the effect is strongest for the wealthiest quintile (Table 2.2).

Having daughters or sons seems to play a role in shaping one’s attitudes towards women’s ownership and inheritance of land. The more daughters that an individuals has, the likelier they are to believe that a daughter should have the same opportunity and rights as a son towards the inheritance of land assets. In this regard, data seem to suggest that having daughters helps shape perceptions and attitudes in the direction of more equitable norms regarding women’s inheritance. Conversely, the more sons an individual has, the more likely they are to hold discriminatory attitudes that disfavour widow’s inheritance or to believe that men and women should not have equal control and decision-making power over agricultural land (Table 2.2).

Table 2.2. Determinants of discriminatory attitudes curtailing women’s ownership of agricultural land

Marginal effects and significance of key characteristics on discriminatory attitudes

|

Dependent variable: discriminatory attitudes on the statements |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(i) |

(ii) |

(iii) |

(iv) |

||

|

“A widow should have equal opportunity and rights as a widower towards inheritance of land assets” |

“A daughter should have equal opportunity and rights as a son towards inheritance of land assets” |

“Women and men should have equal access to agricultural land ownership” |

“Women and men should have equal decision-making power over agricultural land” |

||

|

Independent variables |

|||||

|

Being a woman |

|||||

|

Living in urban areas |

o |

o |

|||

|

Age |

o |

||||

|

Age squared |

o |

||||

|

Education (omitted: no formal education) |

Primary incomplete |

o |

o |

||

|

Primary complete |

o |

||||

|

Secondary complete |

o |

||||

|

University complete |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

|

Marital status (omitted: married) |

Living together |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

Single |

o |

o |

o |

||

|

Size of the household |

o |

o |

o |

||

|

Number of daughters |

o |

o |

o |

||

|

Number of sons |

o |

||||

|

Wealth (omitted: 1st quintile) |

2nd quintile |

o |

o |

o |

|

|

3rd quintile |

o |

o |

o |

o |

|

|

4th quintile |

o |

o |

|||

|

5th quintile |

o |

o |

|||

|

Zanzibar’s regions |

|||||

Note: The table reports the sign of independent variables from four probit models where the dependent variables are (i) the share of the population who disagrees with “A widow should have equal opportunity and rights as a widower towards inheritance of land assets”; (ii) the share of the population who disagrees with “A daughter should have equal opportunity and rights as a son towards inheritance of land assets”; (iii) the share of the population who strongly disagrees or disagrees with “Women and men should have equal access to agricultural land ownership”; and (iv) the share of the population who strongly disagrees or disagrees with “Women and men should have equal decision-making power over agricultural land”. Additional control variables include regional dummies. o = no significant effect; = a significant positive effect; = a significant negative effect.

Source: (OECD, 2021[11]), SIGI Tanzania database, https://stats.oecd.org.

Policy recommendations

Access to the labour market

Consider putting in place retention measures for girls dropping out of school (e.g. by facilitating the re-entry of pregnant adolescent girls into the school system) and guaranteeing pregnant adolescents the right to stay in school.

Establish sensitisation campaigns against girl child marriage inside and outside of schools to address girls’ dropout rate at the secondary level.

Design and implement innovative programmes to provide girls with access to secondary school facilities, particularly in rural areas (e.g. through safe transportation schemes between households and schools, subsidised safe housing programmes and the development of more public boarding secondary schools open to girls).

Consider the establishment of programmes such as conditional cash transfers to incentivise households in investing further in girls’ secondary and upper-level education.

Address gender norms and structural biases that contribute to horizontal segregation and prevent women from entering certain sectors. In particular:

Institutionalise gender mainstreaming in learning institutions to encourage more young women to pursue subjects and courses where men are traditionally over-represented.

Establish academic orientation sessions and individualised coaching at school to sensitise girls and women to opportunities in sectors other than agriculture and food and accommodation. Promote career guidance services, especially at the college level (technical and vocational training centres and universities), to help young women make informed educational choices based on demands and opportunities in the labour market.

Conduct a full review of school material to identify and remove gender-based biases that shape social norms and views on sectors or types of jobs that are deemed appropriate for men and women.

Eliminate gender stereotypes by introducing specific modules dedicated to comprehensive sexual and reproductive health, human and child rights, and gender equality.

Work with learning institutions and universities to undertake labour market assessments in order to clearly inform the design of the curriculum and the type of classes offered. Support educational institutions in undertaking gender and social inclusion analyses in order to identify the key drivers of gender inequality in these institutions. Based on these analyses, formulate retention policies targeted towards young women.

Measure, recognise and start reducing and redistributing women’s disproportionate share of unpaid care and domestic work that constrains their access to formal work outside of the household (see Chapter 3). In particular:

Leverage infrastructure development projects to provide communities with enhanced access to basic services – especially water and electricity – in order to reduce women’s and girls’ share of unpaid care and domestic work.

Invest in public and formal childcare services such as family day‑care, centre‑based out-of‑school hours care, centre-based day‑care and kindergarten. Design cash-transfer programmes to encourage the uptake of child care services.

Develop and run advocacy campaigns designed to inform communities of the benefits of women’s participation in the labour market.

Focus targeted and support measures for the post-COVID-19 economic recovery on sectors in which women are overrepresented, including wholesale and retail and food and accommodation services.

Set aside public procurement contracts for women-led businesses, especially in sectors where women are underrepresented such as construction and mining and quarrying.

Access to agricultural land

Integrate all three SDG indicators on land and gender (1.4.2, 5.a.1 and 5.a.2) into the national monitoring framework.

Strengthen existing legal frameworks at the national and sub-national levels. In particular:

Ensure that gender equality provisions established by the Land Act and the Village Land Act are not undermined by other policies, such as the National Land Policy, or laws, such as the Marriage Act, especially regarding inheritance practices and the transmission of land.

Conduct a full review of inheritance laws and regimes in Tanzania and enact uniform legislation that protects the rights of widows and daughters to inherit assets, especially agricultural land.

Consider implementing quotas to guarantee women’s equal representation in land governance bodies such as land tribunals and councils.

Strengthen the accountability of individuals and institutions in charge of land use planning and the issuance of land titles or certificates of customary right of occupancy.

Establish capacity-building programmes for government officials at the national and sub-national levels on how to implement gender-responsive planning and budgeting.

Improve the dissemination of gender and land rights data by providing free legal aid to women and organising information campaigns in the media (radio and newspapers) on the resources available to women.

Continue efforts to sensitise the population on issues related to women’s rights, land rights and the SDGs.

Strengthen and expand the financial access of women. In particular:

Encourage the development of financial services in the private sector that are gender sensitive and oriented towards agricultural activities in order to improve women’s access to capital and funding.

Develop communication and awareness programmes specifically targeting women’s agricultural co-operatives and self-organised groups, to provide them with information on how to access critical financial services.

Improve rural women’s financial literacy through dedicated training programmes and workshops targeted at schools and consider the integration of compulsory financial education modules into school curricula.

Strengthen women’s capacities and position in the agricultural sector. In particular:

Develop mentorship programmes and peer-support groups for women working in agriculture with the objective of developing valuable business networks.

Establish collaboration schemes and training programmes for women in agriculture to ensure they can gain access to larger markets, are positioned to take advantage of intra-regional trade and know the processes to follow to sell products on international markets.

References

[20] Buscatto, M. and B. Fusulier (2013), “Presentation. “Masculinities” Challenged in Light of “Feminine” Occupations”, Recherches sociologiques et anthropologiques, Vol. 44/2, pp. 1-19, https://doi.org/10.4000/rsa.1026.

[10] Dieterich, C., A. Huang and A. Thomas (2016), “Women’s Opportunities and Challenges in Sub-Saharan African Job Markets African Department Women’s Opportunities and Challenges in Sub-Saharan African Job Markets”, IMF Working Paper, Vol. WP/16/118, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2016/wp16118.pdf.

[30] EIGE (n.d.), Glossary and thesaurus: Horizontal segregation, https://eige.europa.eu/thesaurus/terms/1247 (accessed on 21 September 2021).

[27] Ezer, T. (2006), “Inheritance law in Tanzania: the impoverishment of widows and daughters”, The Georgetown journal of gender and the law, Vol. 7/3, p. 599, https://www.law.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Inheritance-Law-in-Tanzania-The-Impoverishment-of-Widows-and-Daughters.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2021).

[8] Ferrant, G. and A. Kolev (2016), “Does gender discrimination in social institutions matter for long-term growth?: Cross-country evidence”, OECD Development Centre Working Papers, No. 330, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jm2hz8dgls6-en.

[9] Government of Tanzania (2019), Country Report on the Review and Progress made in Implementation of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action - Beijing +25, https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/CSW/64/National-reviews/United-Republic-of-Tanzania-en.pdf.

[23] Government of Tanzania (2018), Land Act [CAP. 113 R.E 2018], https://tanzlii.org/tz/legislation/act/2019-26 (accessed on 8 November 2021).

[24] Government of Tanzania (2018), Village Land Act [CAP. 114 R.E 2018], https://tanzlii.org/tz/legislation/act/2019-27 (accessed on 8 November 2021).

[25] Government of Tanzania (1997), National Land Policy, http://www.tzonline.org/pdf/nationallandpolicy.pdf (accessed on 8 November 2021).

[28] Holcombe, R. (2020), “Power in Agrarian and Feudal Societies”, in Coordination, Cooperation, and Control, Springer International Publishing, Cham, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-48667-9_6.

[1] ILO (2021), Labour force participation rate by sex, ILOSTAT, https://ilostat.ilo.org/data/ (accessed on November 2021).