This chapter provides an assessment of Uruguay. It begins with an overview of Uruguay’s context and subsequently analyses Uruguay’s progress across eight measurable dimensions. The chapter concludes with targeted policy recommendations.

SME Policy Index: Latin America and the Caribbean 2024

15. Uruguay

Abstract

Overview

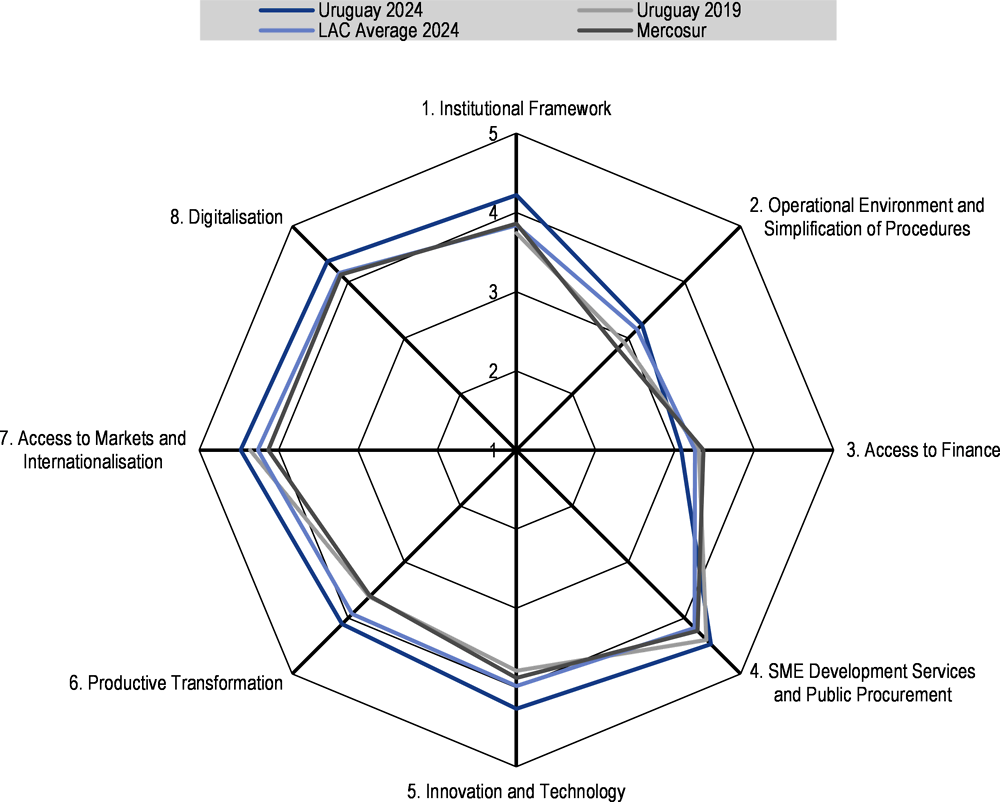

Figure 15.1. 2024 SME PI Uruguay's score

Note: LAC average 2024 refers to the simple average of the 9 countries studied in this 2024 report. There is no data for the Digitalisation dimension in 2019 as the 2019 report did not include this dimension.

Uruguay stands out with significant improvements in 6 out of the 7 dimensions evaluated in the 2019 edition, positioning itself above the regional average for LA9 countries, and showcasing its commitment to adopting previous recommendations. This progress is supported by a wide range of SME support services. At the same time, the country demonstrates a remarkable performance in the new Digitalisation dimension. However, key opportunities for improvement for Uruguay remain in the area of Access to Finance (Dimension 3), where the country could benefit from peer learning, as well as its monitoring and evaluation capacity to enhance the overall effectiveness of its policy interventions supporting SMEs.

Uruguay has a clearly assigned policy mandate, a medium-term development strategy for SMEs, an independent agency which works together with the the Ministerio de Industria, Energía y Minería (Ministry of Industry, Energy, and Mining, MIEM) for policy implementation, and effective mechanisms for public-private consultations. Nevertheless, it could review its SME development strategy (2020-2025) in light of the economic crisis triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent recovery phase in view of a new strategy. Going forward, Uruguay could further strengthen its SME development programmes and services to continue improving and become a top performer among LA9 countries.

Context

Within Latin America, Uruguay distinguishes itself with a high per capita income and low levels of inequality and poverty. Relatively, it boasts the largest middle class in the Americas, encompassing over 60% of its population (World Bank, 2022[1]). However, prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the country's inclusive growth model began showing signs of decline. GDP growth, which stood at 4.6% in the first decade of the millennium, diminished to 0.8% in 2019, and poverty reduction had stagnated with indications of an increase in 2019 (World Bank, 2022[1]). In 2020, following 17 consecutive years of expansion, GDP contracted by 6.3% (ECLAC, 2021[2])Through a combination of factors such as a manufacturing boost, an early vaccination campaign, robust exports, and the country's social compact, the economy rebounded by 5.3% in 2021 (BCU, 2021[3]).The momentum persisted in 2022, with GDP growing by 4.9%, fuelled by significant investments in cellulose, paper, and wood pulp manufacturing by the Finnish company UPM-Kymmene Corporation, along with strong foreign trade performance in the first half of the year. However, economic activity declined in the latter half of the year due to a severe drought affecting agricultural production and exports, coupled with the completion of the UPM2 works. In 2023, the economy experienced a slowdown with 1.3% growth, primarily attributed to contractions in the agricultural, fishing, mining, electricity, gas, and water sectors, strongly impacted by the drought (BCU, 2023[4]).

Inflation reached 7.5% in 2023 and is projected to further decrease to 6.2% in 2024. Recognising signs of a slowdown, the Banco Central del Uruguay (Central Bank of Uruguay, BCU) became the first central bank in the region to lower the policy rate, reducing it by 0.25 percentage points to 11.2% at its April meeting. This adjustment followed a peak at 11.5%, starting from 4.5% in September 2020 when it was negative in real terms to mitigate the effects of the pandemic (BBVA, 2023[5]). The overall public sector deficit concluded 2022 at 3.2% of GDP and excluding extraordinary revenues from the Fidecomiso de la Seguridad Social (Social Security Trust Fund, FSS), it would have stood at 3.4%. This marked an improvement of 0.7 percentage points compared to 2021, representing three consecutive years of compliance with the target (BBVA, 2023[5]).

Regarding the labour market, in December 2021, the activity rate in Uruguay was 62%, the employment rate was 57.7%, and the unemployment rate stood at 7% (INE, 2021[6]). This represented a notable improvement of 4 percentage points in the unemployment rate compared to 2020, reaching pre-pandemic levels. Moving to December 2022, the labour market remained stable, with the activity rate at 62.7%, the employment rate at 57.7%, and the unemployment rate at 7.9% (INE, 2022[7]). The informality rate in 2022 was 20.5%, showing a decrease of 1.8 percentage points in year-on-year terms (CINVE, 2022[8]). In December 2023, the activity rate increased to 63.8%, the employment rate to 58.9%, and the unemployment rate to 7.8% (INE, 2024[9]).

Dimension 1. Institutional Framework

Uruguay stands out with a significant improvement in the institutional framework dimension, achieving a score of 4.22. This reflects the establishment of a relatively well-structured framework for SME policy, leveraging some of the recommendations from the 2019 SME PI. Key features include an operational definition of SMEs, a clearly assigned policy mandate, a medium-term development strategy for SMEs, an independent agency responsible for policy implementation, and effective mechanisms for public-private consultations. Additionally, Uruguay has successfully contained the size of its informal sector compared to other Latin American countries, attributed to the implementation of flexible tax regimes. However, there is room for improvement in Uruguay's monitoring and evaluation capacity to enhance the overall effectiveness of its policy interventions supporting SMEs.

The country achieves the highest score (4.7) in the SME definition sub-dimension among the LA9 countries, primarily attributed to methodological adjustments in the individual weighting values assigned to the assessed elements. The current SME definition was established by Decree 504 issued in 2007 and is grounded in two parameters: sales and employment. Values are denominated in Unidades Indexadas (UI), subject to periodic adjustments aligned with the inflation rate. The definition incorporates an independence clause stipulating that an enterprise must not be under the control of a large enterprise to be classified as an SME. Furthermore, SMEs are required to register in the Registro Pyme, managed by MIEM, and renew their registration annually to confirm their SME status and access SME support programmes.

The SME policy mandate is entrusted to the MIEM, specifically the Dirección Nacional de Artesanías, Pequeñas y Medianas Empresas (National Directorate of Crafts, Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises, Dinapyme). Until 2020, SME policy objectives were outlined in two key strategic documents. The first document presented the strategic guidelines for 2015-2020 within the MIEM. The second significant document was the National Plan for Productive Transformation and Competitiveness (2017-2021), implemented by the inter-ministerial coordination system known as Transforma Uruguay. The plan aimed to foster the country's productive transformation, encompassing projects related to innovation, human capital development, attracting foreign direct investment (FDI), and supporting SMEs, such as the establishment of enterprise innovation centres. A new SME development strategy (2020-2025) has been crafted as part of the government plan.

Furthermore, the Agencia Nacional de Desarrollo (National Development Agency, ANDE), the Agencia de Gobierno electrónico y Sociedad de la Información de Uruguay (E-Government and Information Society Agency of Uruguay, AGESIC), and the Instituto Nacional de Empleo y Formación Profesional, (National Institute for Employment and Vocational Training, INEFOP) collaborated in 2022 to initiate a multi-year programme aimed at promoting enterprise digitalisation. This programme is backed by a USD 15 million loan from the IADB and is executed by ANDE, which is also responsible for implementing SME support programmes and delivering business services to SMEs. The Agencia Nacional de Investigación e Innovación (National Agency for Research and Innovation, ANII), manages innovation programmes and provides support to innovative SMEs.

The implementation of Dinapyme's programmes and tools are monitored on a regular basis, which produces a detailed annual activity report integrated into the MIEM annual report. These concerted efforts have contributed to Uruguay achieving a score of 4.23 in the sub-dimension of Strategic Planning, Policy Design, and Coordination, surpassing the score of 3.59 in the 2019 assessment, showcasing the positive strides the country is making in this area.

Furthermore, demonstrating progress, public-private consultations emerge as another sub-dimension with a notable score of 3.93. At citizen level, the government has established a digital public consultation platform managed by the AGESIC-Gobierno Abierto (Open Government). Additionally, each ministry conducts public consultations through their respective websites, as well as on the Open Government website.

At the enterprise level, private sector organisations are consulted during various phases of the elaboration and approval of legislative and regulatory acts. These consultations are conducted ad hoc, with invitations issued by the MIEM.

Finally, the informal sector in Uruguay is relatively smaller than in other Latin American countries, as the country was one of the first to systematically address the issue of labour and enterprise informality. This initiative began with the introduction of the Monotributo in 2007. According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), informal labour accounts for around 25% of total employment. Data on informal labour are regularly collected through the Continuous Household Survey. In addition to the Monotributo, the government has introduced several incentives to promote labour and enterprise formalisation. Dinapyme sponsors the organisation of workshops to encourage the formalisation of new enterprises and individual entrepreneurs (score for Measures to Tackle Informal Economy: 4.00).

The way forward

Review the SME development strategy (2020-2025), considering the impact of the economic crisis generated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent recovery phase.

Systematically collect data on the implementation of the SME Development strategy and various SME support programmes to enhance monitoring mechanisms and establish the basis for programme evaluations.

Ensure regular consultation of SME representatives throughout all phases of SME policy, including design, elaboration, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation, encompassing all categories of enterprises.

Dimension 2. Operational environment and simplification of procedures

Uruguay faces a relatively complex operational environment for SMEs. The process of regulatory reform has slowed in recent years. While there has been some advancement in simplifying the process of starting a business and streamlining tax filing procedures for SMEs, several areas continue to be burdened by complex procedures and heavy administrative requirements. Notably, significant progress has been achieved in the development and provision of e-government services.

As indicated by a score of 1.87 the operational environment for SMEs in Uruguay is still marked by significant administrative burdens. Initial regulatory reform actions were conducted within the framework of the Transforma Uruguay plan. However, since the plan's completion in 2021, no new plan has been launched, and actions are taken only on a case-by-case basis. Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) is not systematically applied.

The process of starting a business in Uruguay is relatively simple and can be completed in a short time, requires a total of five procedures and is completed in 6.5 days. Upon registration, the new enterprise receives a single identification number that can be utilised across the public administration, the Registro Único Tributario (Single Tax Register, RUT) issued by the Dirección General Impositiva (General Directorate of Taxation). There is no One-Stop-Shop (OSS) in place, but instead, a system based on several windows operating in the same location. Online company registration is available through the Empresa en el Día platform, although it does not cover the entire registration process. Uruguay scores 3.48 in the Company Registration sub-dimension.

Furthermore, the administrative tax burden for SMEs is relatively light compared to other LAC countries, with a score of 3.48 in the sub-dimension of Ease of filing taxes. A notable aspect of the tax system is the high frequency of tax payments per year (20) and the relatively high rate of corporate taxes and social contributions on total profits (41.8%).

SMEs enjoy a reduced income tax rate initially. However, they encounter a significant tax rate increase when transitioning from the small-scale enterprise regime to a standard Impuesto a las Rentas de las Actividades Económicas (Tax on Income from Economic Activities, IRAE) tax regime. This transition occurs under two possible scenarios: (1) If an enterprise, which is taxed under the Small Business Value Added Tax (VAT), exceeds 305,000 UI in turnover, it then shifts to the IRAE regime. If the following year's turnover falls below the Small Business threshold, it can revert to the previous regime. (2) If an enterprise, taxed under the Small Business VAT, voluntarily opts for the general regime, it must remain in that regime for three years before reverting to the Small Business VAT regime.

Finally, Uruguay's best performance in the second dimension is on the e-government sub-dimension (4.70). The country has actively promoted the digital transformation of state administration and the development of e-government services for over a decade, achieving substantial progress in this area. One of the measures taken to streamline procedures has been to increase the exchange of files in digital format. Uruguay ranked 35 out of 193 countries covered by the UN Electronic Government Survey, the highest in Latin America, with an E-Government Development Index (EGDI) of 0.85 out of 1.

The government has launched and implemented a series of Digital Strategies, with the latest one covering the period 2021-2025. The implementing agency is the AGESIC, located under the Presidencia de la República de Uruguay. There is already a good range of e-government services in place.

The way forward

Consider launching a new programme of legislative simplification and regulatory reform, capitalising on the experience gained through the implementation of the Transforma Uruguay programme. In close cooperation with private sector organisations, the government should identify the areas that are most critical for the improvement of the operational environment and formulate a plan of action for reform.

Take steps for the application of RIA on the most relevant new legislative and administrative acts. To proceed in this direction, the government should identify a public institution that could act as a coordinator and supervisor of RIA applications and form a team of RIA specialists.

There is room for further simplification of company registration procedures. In this context, the government should consider establishing a network of One-Stop-Shops.

Dimension 3. Access to finance

Uruguay obtains an overall score of 3.08 in the Access to Finance dimension. It also achieves a score of 3.45 in the Legal Framework sub-dimension, slightly below the LA9 regional average. This result is mainly due to the development of the asset register and a high score in the collateral weighting, although it has a slightly lower score in the regulation of the securities market.

Compared to other LA9 countries, the regulation regarding the percentage of collateral required for medium-term loans to SMEs is relatively low in Uruguay. However, the country boasts a functional cadastre accessible to the public online. Furthermore, Uruguay has a fully operational registry of security interests in movable assets, which is partially available online, facilitating the documentation of pledge ownership. This system ensures that movable assets are widely accepted as collateral in the financial system, thereby providing additional avenues for SMEs to access financing.

Regarding the development of the legal framework for access to finance, there is no special regulation in the capital market for SMEs, although regulations on Simplified Issuances with Public Offering have been issued. However, there is no separate section or market in the stock market for these small-cap companies, and there is no strategy to help them comply with listing requirements.

In the sub-dimension of Diversified Sources of Enterprise Finance, Uruguay scores 4.40, reflecting its broad array of financial products available to SMEs. Particularly noteworthy is the facilitated access to commercial credit through the Sistema Nacional de Garantías para Empresas (National System of Guarantees for Enterprises, SIGA), which plays a vital role in supporting small entrepreneurs. Additionally, Uruguay benefits from the presence of several entities specialised in offering financial solutions to SMEs, providing access to multiple asset-based lending (ABL) instruments. Moreover, the country regulates alternative financing mechanisms, such as crowdfunding platforms, in accordance with the provisions of Law 19820 and the resolution of the Banco Central del Uruguay (Central Bank of Uruguay, BCU), thus integrating Fintechs into the regulatory framework.

In the Financial Education dimension, Uruguay has achieved a total score of 2.55, marking an increase compared to the 2019 edition. Unlike other LA9 countries, Uruguay does not have national financial inclusion and financial education strategies coordinated by a national committee. However, it does have public policies at national level in these areas. Specifically, a national financial inclusion public policy has been developed and is led by the Ministerio de Economía y Finanzas (Ministry of Economy and Finance, MEF).

Moreover, Uruguay has a national economic and financial education programme led by the BCU, which involves agreements, conventions, and contributions from various national entities such as the public education system, the Ministerio de Educación y Cultura (Ministry of Education and Culture, MEC), the University of the Republic (UDELAR), the trade union center, and all public and private actors in the financial system. Although this programme is not specifically focused on micro-entrepreneurs, it serves to enhance financial literacy across the population. Recently, the BCU, with the support of CAF, conducted a survey in 2023 to measure financial capabilities.

In the sub-dimension of Access to Finance, which assesses the Efficient procedures for dealing with bankruptcy, and mechanisms to facilitate the productive reintegration of unsuccessful entrepreneurs, Uruguay scores 1.92 points. This performance, measured only in the policy design and implementation phase, is due to an underdeveloped regulatory framework, based on internationally accepted principles, which does not apply to state-owned enterprises.

Uruguay has an early warning system for insolvency and bankruptcy situations through the clearing of reports and the National Register of Legal Entities in the National Commercial Registry Section. In addition, there is the possibility of resorting to out-of-court settlements that are less onerous than declaring bankruptcy, through Private Reorganisation Agreements.

A noteworthy aspect in Uruguay is the existence of formal procedures for exemption from bankruptcy liability through the Bankruptcy Process Law number 18.837, which regulates exonerations from liability in specific cases, without establishing deadlines. It also provides for a formal procedure for bankruptcy and liquidation of companies, which includes the classification of fault and fortuitous.

When a company is declared insolvent, its details are stored in special registers that are not accessible to the public. Uruguay does not have a system of automatic removal of this information from all registers when the situation is remedied. Nor does it offer exclusive capacity building for entrepreneurs whose initial ideas did not prosper.

Uruguay has regulations for secured transactions that prioritise secured creditors in the liquidation of a bankrupt company. However, this regulation does not provide for secured creditors to seize their collateral after reorganisation, nor does it provide for certain restrictions to be respected when a borrower files for reorganisation, such as the consent of creditors. In addition, tax debts have priority over any other debts in bankruptcy.

The way forward

Make the registry of security rights over movable assets fully operational and online.

Promote special regulation in the capital market for SMEs, and disseminate it widely, promote a separate section or market in the stock market for SMEs, and establish a strategy to help SMEs comply with listing requirements.

Facilitate assistance and training programmes for SMEs through available credit guarantee schemes. It could also promote the development of credit guarantee systems while encouraging the participation of the private sector in its management.

Design a National Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS) and a National Financial Education Strategy with governance schemes that allow the coordination of policies and improve the effectiveness of programmes, as well as periodically conduct financial capability surveys for SMEs in order to have updated information for the design of financial education programmes. Similarly, design and implement a follow-up, monitoring and evaluation system for both policy and programmes.

Strengthen the existing regulatory framework related to bankruptcy and insolvency policies according to internationally accepted principles and extend its application to state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

Strengthen its procedures for handling bankruptcy by implementing an official bankruptcy registry that is freely accessible to the public and has an automatic mechanism to remove companies from the registry when the situation is resolved, in line with international best practices.

Design and implement training programmes for second chances, targeting individuals whose businesses have gone bankrupt.

Dimension 4. SME development services and Public Procurement

Performance in SME development services and public procurement for Uruguay is solid, with a score of 4.47, above the regional average of 4.18. Key strengths are in entrepreneurial development services (4.71) and public procurement (4.60), with a slightly lower score in Business Development Services (4.19).

As in the 2019 assessment, Uruguay is one of the very few countries to implement a strategic approach towards the provision of business development services and support for startups and entrepreneurs. Those support services consider the wider national economic development and transformation goals as reflected in the SME development strategy 2020-2025 (see Dimension 1. Institutional Framework). The offer of Business Development Services (BDS), however, has not been based on the development of a detailed study of the needs of the SME sector, according to the responses to the questionnaire for this assessment.

The array of BDS and programmes for entrepreneurs comprises advice, trainings, subsidies, support in the obtention of quality certificates, internationalisation, commercialisation, design, energy, etc. Services are delivered by various institutions including the MIEM, ANDE, INEFOP, and the exports and investment agency, Uruguay XXI, among others. Services are also provided through a network of SME Centres across the territory (formerly known as the Competitiveness Centres). In addition, programmes exist to co-finance the provision of services by private sector providers. According to the questionnaire for this assessment, the funding is adequate for the BDS to achieve their objectives.

Public procurement is governed by a series of laws and regulations, including the Texto Ordenado de Contabilidad y Administración Financiera (Ordained Text of Accounting and Financial Administration, TOCAF), which establishes how the state should procure the goods and services it needs. The public procurement regime establishes that contracts above a certain size should be divided in lots, allows for the formation of consortia of SMEs, includes set-asides for SMEs and establishes framework agreements. The regulations, however, do not decree any penalties or measures to ensure timely payments in public procurement. Additionally, Article 43 of Law No. 18,362 of October 6, 2008, established the Public Procurement for Development Programme. Its objective is to employ special procurement regimes and procedures that promote the development of domestic suppliers and stimulate scientific-technological development and innovation.

As in the 2019 SME PI, Article 50 of TOCAF establishes the mandatory character of e-procurement. It notes that public administrations should publish their procurement offers (including their specific conditions, modifications, or clarifications) through the website of the Agencia Reguladora de Compras Estatales (Contracting and Purchasing Agency of the State, ARCE).

The way forward

In general, Uruguay continues to display a solid performance in this dimension, with some areas to work on going forward:

Developing comprehensive diagnostics on the demand and offer of business development services across the country, so that the SME strategies can be better informed and targeted.

Strengthening the public procurement system by introducing measures and penalties to ensure that payments are made on time.

Dimension 5. Innovation and technology

Uruguay’s overall score of 4.27 in the Innovation and Technology dimension is the second highest in the LAC region. This is underpinned by strong scores across each of the three sub-dimensions. ANII is the primary implementing body for innovation programmes. ANII’s board of directors include representatives from key ministries and the Consejo Nacional de Innovación, Ciencia y Tecnología (National Council of Innovation, Science and Technology, CONICYT), which represents an important tool for horizontal co-ordination of innovation policies. CONICYT, which is represented by private sector representatives, academia, and relevant government ministries, is responsible for preparing proposals for innovation policies and priorities. Since 2007, Uruguay’s innovation strategy has historically been relatively broad in its focus. However, from 2023, an increased emphasis is being placed on advanced digital technologies, green tech, and biotech. These features of Uruguay’s framework for innovation policy support a score of 4.29 in the Institutional Framework sub-dimension.

A key pillar of Uruguay’s support services for innovation is the Uruguay Innovation Hub, which is led by ANII and a number of other government ministries and entities. The initiative seeks to establish a technology-based accelerator focused on promoting the internationalisation of Uruguayan start-ups, an innovation campus within the LATU Technology Park, and open innovation labs across the country. These measures would strengthen an already robust system of innovation support services and facilities, delivered through a range of programmes, incubators, and science and technology centres. Uruguay has a score of 4.23 in the Support Services for Innovation sub-dimension, which is the third highest in the region.

The non-financial innovation supports are complemented by a strong offering of financial support measures. Uruguayan SMEs can apply to ANII for funding to strengthen their internal innovation capabilities, for instance through the hiring of international experts, the use of consulting services, and spending time at technology centres or foreign universities and companies. There is also a public procurement for innovation scheme, through which public entities can identify challenges associated with improving their public services. However, it is reported that the complexity of the reglementation has reduced engagement. Another source of financing support for innovation is delivered through R&D tax credits. These appear to have strong uptake among SMEs, supported by pro-active outreach efforts through social media channels, business fairs, exchanges with business representative organisations, and the provision of information on ANII’s website. This strong provision of financial support for SME innovation contributes to a score of 4.29 in the Financing for Innovation sub-dimension.

The way forward

Engaging with public entities to raise awareness and buy-in across government on public procurement for innovation. These outreach efforts can be complemented by training and capacity building to overcome technical and legal skills gaps that can inhibit public entities from participating in public procurement for innovation.

Conducting robust evaluations of current and planned initiatives of the Uruguay Innovation Hub. The introduction of these new initiatives provides a good opportunity to embed strong monitoring and evaluation procedures within the schemes from their inception.

Dimension 6. Productive transformation

Uruguay's commitment to enhancing productive transformation and strengthening monitoring and evaluation systems in this dimension is evident in its commendable score of 4.11, surpassing the regional average (3.93). Following the conclusion of Transforma Uruguay and its first strategic plan, evaluated during the 2019 assessment, Uruguay delineates its long-term strategy for Development 2050. Launched in 2019 after a thorough process with coordinated leadership from the Office of Planning and Budget (OPP) through the Directorate of Planning, one of these axes is specifically dedicated to sustainable productive transformation. However, despite these advancements, Uruguay's institutional environment, once simplified by Transforma Uruguay, remains complex. Notably, Uruguay's score for the sub-dimension of Strategies to enhance productivity (3.82) is bolstered by the establishment of the Industrial Productivity Monitoring Indicators System (SIMPI). This system aims to obtain total factor productivity measures by sector and is intended to be used for informed decision-making, as well as for proposing, executing, and evaluating public policies.

Furthermore, Uruguay has a long-standing experience with support programmes aimed at enhancing productive associations. Presently, ANDE oversees various initiatives, notably the SME Centres and the Associative Practices programme. SME Centres serve as hubs for supporting and advising SMEs in their development and growth. They play a crucial role in the framework of the Associative Practices programme, which seeks to support groups of SMEs from the same sector, value chain, or territory, with financial resources to implement joint actions.

In terms of industrial parks, the new regime, based on Law No. 19,784 and regulated by Decree No. 79/2020, introduces, for the first time in law, the concept of Scientific-Technological Parks, while maintaining the concept of Industrial Parks, and defining the Specialised Park modality. It facilitates more accessible rates or conditions for public services and establishes a regime of control and sanctions. Uruguay's positive shift is evident in reaching a score of 4.16 for the Productive Association-Enhancing Measures sub-dimension.

Finally, Uruguay excels in the Integration into Global Value Chains sub-dimension, achieving a score of 4.49, the highest among the LA9 countries. The UPM Supplier Development Programme aims to promote the integration of national suppliers and services into the value chain associated with the UPM Project. This initiative encourages the adaptation of the productive conditions of national companies, it is implemented by ANDE and falls withing the framework of the Fondo de Innovación Sectorial (Sectorial Innovation Fund, FIS).

The way forward

Uruguay could strengthen its commitment to fostering productive transformation by:

Formulating a comprehensive action plan that spans various government sectors. This plan should articulate clear objectives, measurable indicators, and specific timelines to effectively guide the country's transformation initiatives. Drawing insights from successful models within the region, such as Colombia's CONPES 3866 Action Plan and Peru's Competitiveness Agenda.

Dimension 7. Access to market and internationalisation of SMEs

Uruguay stands out in the Access to market and internationalisation dimension, scoring 4.48. Its overall score is bolstered by its strong performance in the Support Programmes for Internationalisation sub-dimension, where it achieves a score of 4.50. This success is largely attributed to Uruguay’s robust policies and programmes in this area. The agency in charge of promoting investment, exports, and the country brand, Uruguay XXI, leads the strategy in this area, based on five key pillars:

promoting internationalisation and business competitiveness;

attracting productive foreign investment;

generating strategic information;

positioning Uruguay in the international arena; and

improving the national business environment.

Uruguay XXI offers a comprehensive suite of tools and services to support the growth and diversification of Uruguayan SMEs, as well as the promotion of an exporting culture. These include advisory services on the export process, facilitating access to international markets, and organising trade promotion activities in collaboration with both public and private institutions. All these efforts are encapsulated within the Uruguay 2050 development plan, which prioritises international integration and export promotion, ensuring that the country's businesses are well-equipped to compete and thrive in the global market. Additionally, it maintains a constantly updated Exporters Information System.

In terms of financing for SMEs, the Superintendencia de Servicios Financieros (Superintendence of Financial Services, SSF) has developed an Action Plan for 2020-28, which includes measures to increase access to credit through sustainable guaranteed systems. Initiatives for financing through capital market have also been explored in coordination with ANDE and the stock exchanges. ANDE offers various financing programmes, such as Crédito SOS PyMEs and the Fondo de Diversificación de Mercados (Market Diversification Fund, FODIME), to promote exports. While Uruguay's main challenge lies in the monitoring and evaluation of its export promotion strategies, the country maintains a constant dialogue with the private sector to make informed decisions.

On the other hand, in the Trade Facilitation sub-dimension, Uruguay obtained a score of 4.35. Uruguay XXI, through its Export Promotion Department, provides a fundamental guide for SMEs starting their export process, offering practical guidance and quick consultation. In addition, the "TUexporta" programme facilitates exports by exempting the payment of taxes and duties for shipments up to USD 2000, streamlining customs procedures through the Foreign Trade Single Windows (VUCE). In November 2023 the One Stop Investment Shop (VUI) was launched. The National Customs Directorate provides certification as an Authorised Economic Operator (AEO). Despite the overall good performance, Uruguay is below the Latin American average in terms of trade facilitation-related procedures (LAC: 1,558; URY: 1,429) and documents (LAC: 1,591; URY: 1,333).

In the Use of e-commerce sub-dimension, Uruguay achieved a solid score of 4.46, reflecting strong performance in this area. The country has enacted Law No. 19210, which regulates electronic payments and provides a legal framework for the sector's development. Additionally, the Uruguay Digital Agenda 2025, aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals and other international initiatives, aims to promote digital transformation and empower SMEs to enhance their sustainability and competitiveness. Uruguay XXI supports e-commerce through the "E-Commerce Directory," facilitating access to information and resources for businesses to establish their online presence. Furthermore, Uruguay has Law No. 18331 on personal data protection (IMFO, 2008[10]), which led to the creation of the Regulatory and Control Unit of Personal Data, ensuring mechanisms for the protection of personal data rights.

In the quality standards sub-dimension, Uruguay achieved an outstanding score of 5.0. This high performance is attributed to the country’s strong institutional infrastructure in quality standards. Support for SMEs to improve their quality standards is integrated into most business promotion and development programmes. Various institutions are dedicated to training personnel in the implementation, evaluation, and improvement of quality management systems under international standards.

The Uruguayan Institute of Technical Standards (UNIT) plays a crucial role in this field, providing ISO-9001 certifications and training for the implementation of quality standards. In 2022, UNIT trained 4,921 individuals through over 300 courses, both in-person and virtual. Additionally, the Technological Laboratory of Uruguay (LATU), established in 1965, offers services oriented toward the production chain and supports quality certification through industrial and agro-industrial analysis. The Uruguayan Accreditation Body (OUA) is responsible for accrediting national conformity assessment bodies.

Uruguay also achieved a notable score of 4.05 in the sub-dimension concerning the benefits of regional integration. The country excels due to its well-defined strategies through Mercosur and its trade policy, addressing aspects such as common nomenclature and tariffs, trade agreements, rules of origin, and special regimes. Information dissemination about the opportunities arising from sub-regional integration is conducted through institutional pronouncements, dissemination actions, and communication policies with citizens. Information is shared in dialogue and consultation instances with the private sector, and initiatives such as "Exporta Fácil" are promoted through its web platform.

General guidelines for sub-regional integration are outlined in the Strategic Plan for Foreign Policy 2020-2025, focusing on revitalising Mercosur's internal agenda and projecting towards the Pacific Alliance. The Directorate of Trade and Investment Promotion Intelligence (DIPCI) of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs plays a fundamental role in promoting exports and attracting investments. It participates in programmes for SMEs, organises trade missions abroad, and supports companies through the diplomatic network. A notable tool is the "Exporter’s Route," developed by Uruguay XXI, which provides updated and free information on the steps in the internationalisation process for businesses.

The way forward

Promote SME certifications as Authorised Economic Operators through differentiated and strategic support, establishing particular benefits and improving communication channels on benefits such as international trade facilitation, cost reduction, and improved supply chain security.

Continue to strengthen and promote e-commerce as a strategic tool for exporters, through programmes that provide SMEs with knowledge and concrete tools for its implementation.

Continue to improve the monitoring and evaluation mechanisms of the internationalisation programmes for SMEs implemented, highlighting the use of quantifiable indicators that allow the process of improvement to be accelerated.

Strengthen the mechanisms for SMEs to access and benefit from the integration processes in which Uruguay participates, with defined and inter-institutionally articulated programmes.

Dimension 8. Digitalisation

Uruguay's overall score of 4.37 in the Digitalisation dimension surpasses the regional average in the LAC region, supported by robust scores in each of the three sub-dimensions. The country's National Digital Strategy, as outlined in the Agenda Uruguay Digital 2025 objectives, serves as a comprehensive roadmap, demonstrating Uruguay's commitment to digital transformation. This strategy places a strong emphasis on digital inclusion as a fundamental right, ensuring that all citizens can exercise their rights and responsibilities in the digital realm. Objectives such as improving digital competencies and skills across all educational levels, integrating digital education into formal curricula, and promoting digital citizen participation highlight Uruguay's dedication to cultivating a digitally literate society. These aspects contribute to Uruguay's score of 4.80 in the National Digitalisation Strategy sub-dimension.

Uruguay adopts a robust approach to connectivity, exemplified by a national digital policy based on the Uruguay Digital Agenda. This agenda encompasses initiatives for the development of digital policies executed by the Public Administration, with a vision for national reach, aimed at narrowing the digital divide. The plan involves extensive infrastructure development to improve coverage, service quality, and the deployment of new technologies, ensuring internet access even in remote areas. The success of this plan is attributed to effective public-private partnerships, which play a crucial role in establishing digital infrastructure. Additionally, Uruguay's commitment to the access of digital services is evident through initiatives such as the virtual police station, providing citizens with 24/7 access to essential services. In the Broadband Connection sub-dimension, Uruguay achieves a score of 4.00.

Digital skills are a focal point of Uruguay's educational agenda, with the National Digital Strategy placing significant emphasis on integrating digital competence into the national curriculum. While digital competence is not yet part of the primary education curriculum, it is incorporated into vocational education and training. The strategy also prioritises lifelong learning, offering non-formal courses to enhance digital skills for the general population. Initiatives such as "Young People to Program" and various STEM education programmes actively promote women's participation, fostering gender inclusivity in digital education and careers. This substantial support for SME upskilling contributes to a score of 4.32 in the Digital Skills sub-dimension.

The way forward

Looking ahead, Uruguay could consider:

Develop policies specifically tailored to address the unique needs and challenges of SMEs in the digitalisation process. This includes ensuring inclusive broadband access, especially in rural areas.

Advocate for enhanced data transparency and standardisation of indicators to facilitate more accurate and comparable assessments of digitalisation progress across the region. This will provide a clearer picture of the impact of digital policies on SMEs and help refine strategies for better outcomes.

References

[5] BBVA (2023), , https://www.bbvaresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Editorial_Uruguay_Economic-Outlook_2023.pdf.

[4] BCU (2023), Informe de política monetaria, https://www.bcu.gub.uy/Politica-Economica-y-Mercados/Paginas/Informe-de-Politica-Monetaria.aspx.

[3] BCU (2021), Cuentas Nacionales e Internacionales y Sector Externo. Producto Interno Bruto y Medidas de Ingreso, https://www.bcu.gub.uy/Estadisticas-e-Indicadores/Paginas/Producto-Interno-Bruto.aspx.

[8] CINVE (2022), Monitor Mensual del Mercado Laboral, https://www.observatorioseguridadsocial.org.uy/images/12_2022_Monitor_Laboral.pdf.

[2] ECLAC (2021), Estudio Económico de América Latina y el Caribe, Uruguay, https://repositorio.cepal.org/bitstream/handle/11362/47192/79/EE2021_Uruguay_es.pdf.

[10] IMFO (2008), Ley No. 18331 Ley de Protección de Datos Personales, https://www.impo.com.uy/bases/leyes/18331-2008.

[9] INE (2024), Actividad, Empleo y Desempleo (ECH) Diciembre 2023, https://www.gub.uy/instituto-nacional-estadistica/comunicacion/publicaciones/actividad-empleo-desempleo-ech-diciembre-2023 (accessed on 14 June 2024).

[7] INE (2022), Boletín Técnico. Actividad, empleo y desempleo, https://www.gub.uy/instituto-nacional-estadistica/comunicacion/publicaciones/actividad-empleo-desempleo-ech-diciembre-2022.

[6] INE (2021), Boletín Técnico. Actividad, empleo y desempleo, https://www3.ine.gub.uy/boletin/Informe_MT_Diciembre_2021.html#fnref1.

[1] World Bank (2022), Uruguay overview, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/Uruguay/overview (accessed on 12 March 2024).