This chapter provides an assessment of Chile. It begins with an overview of Chile’s context and subsequently analyses Chile’s progress across eight measurable dimensions. The chapter concludes with targeted policy recommendations.

SME Policy Index: Latin America and the Caribbean 2024

16. Chile

Abstract

Overview

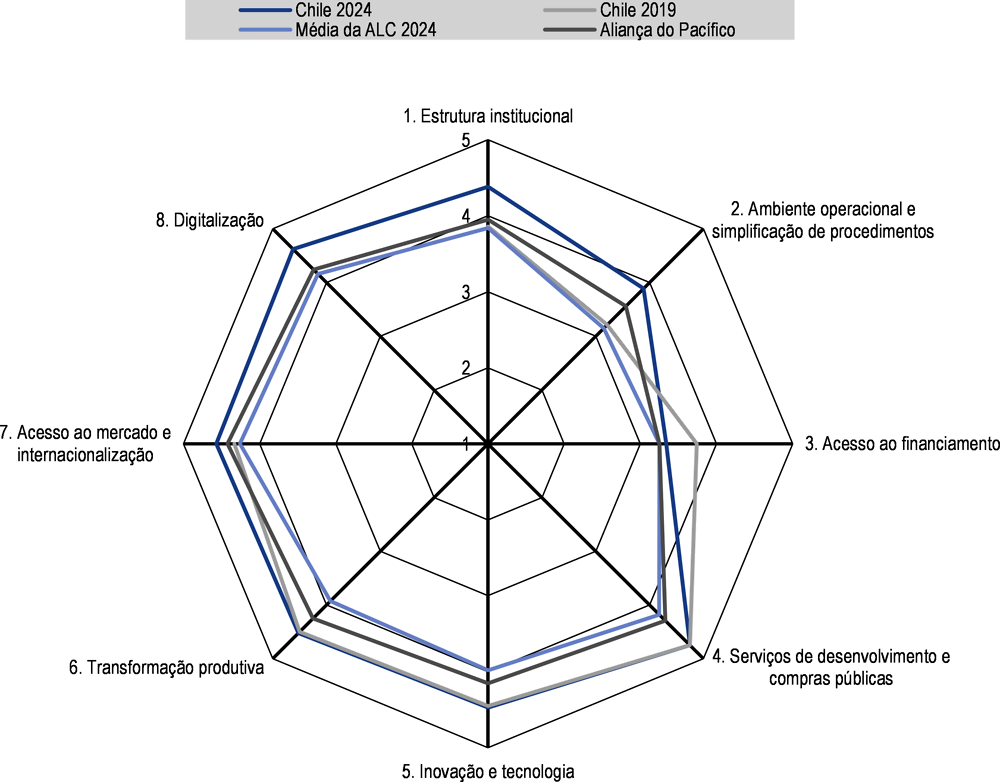

Figure 16.1. 2024 SME PI Chile's score

Note: LAC average 2024 refers to the simple average of the 9 countries studied in this 2024 report. There is no data for the Digitalisation dimension in 2019 as the 2019 report did not include this dimension.

Chile demonstrates top performance in this second SME Policy Index assessment (see Figure 16.1), ranking as the leading LA9 performer in all dimensions except for Access to Finance (Dimension 3). This success is attributed to an advanced framework for SME policy, which includes clear mandates for policy formulation and oversight, a relatively robust operational environment, and a wide array of SME support services available across all dimensions.

However, Chile could benefit from the elaboration and approval of the new SME strategic development plan that incorporates advanced monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. Prioritising the integration of policy actions to support SME digital transformation within this framework could be a key focus moving forward. Additionally, as will be further detailed throughout this chapter, Chile could develop a more comprehensive innovation strategy that includes detailed proposed policy actions, responsible implementation entities, timelines, objectives, key performance indicators, and targets.

Context

Chile witnessed a steady recovery in 2021, recording a GDP growth rate of 11.9% (OECD, 2024[1]) as it rebounded from the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Key drivers of this growth included increased consumption fuelled by pension fund withdrawals, direct fiscal support, and the nation's rapid vaccination campaign (World Bank, 2022[2]) However, in 2022, the economy decelerated to 2.5. Output is projected to grow by 2.3% in 2024 and 2.5% in 2025 (OECD, 2024[3]).

Inflation has receded since reaching its peak in 2022, driven by a gradual resolution of macroeconomic imbalances. During 2021-2022, the Central Bank steeply increased its policy rate (from 0.5% to 11.25%). This played a central role in moderating consumption and narrowing the output gap, consequently leading to a decline in inflation. The recovery in household disposable income, driven largely by the process of inflation convergence, will continue to support this performance (CBC, 2023[4]). Inflation will converge to the 3% target in mid-2025 (OECD, 2024[3]).

The recovery in the labour market has been gradual, with 60% of the jobs lost in 2020 being recovered by 2021 (World Bank, 2022[2]). By 2023 the employed managed to surpass pre-pandemic levels by maintaining a significant gap (500,000 people) with respect to the trend. The unemployment rate remains at higher levels than before the start of COVID-19. However, in this case, the economic slowdown has an important influence (Bastidas and Vergara, 2023[5]).

The SME sector in Chile, comprising 98.6% of all enterprises, has been particularly impacted by the pandemic and subsequent macro-economic disruptions. Among these enterprises, 75.5% are micro-enterprises, 20.2% are small enterprises, and 2.9% are medium-sized (OECD, 2022[6]). Despite their numerical dominance, large firms (1.5% of total enterprises) contribute significantly to total sales, comprising 86.9%, while SMEs account for only 13.1% (OECD, 2022[7]). Chile's solid institutional framework, along with recent government efforts, has enabled a more integrated approach to SME recovery. The government has implemented various measures to support the sector, including initiatives to boost investment, develop infrastructure, streamline bureaucratic procedures, and promote innovation (Ministry of Economy, Development and Tourism Chile, 2023[8]).

Chile's business environment presents significant opportunities, driven by its integration into foreign trade, favourable regulatory conditions, and credit market conditions. The country has established 31 economic-trade agreements covering 65 economies globally, representing 88% of the world's GDP and providing access to a potential market of more than 5 billion people worldwide (SUBREI, n.d.[9]).

Dimension 1. Institutional Framework

Chile has established an advanced framework for SME policy, with clear mandates for policy elaboration and supervision assigned to the Ministerio de Economía, Fomento y Turismo (Ministry of Economy, Development, and Tourism). Policy implementation is delegated to two specialised agencies Corporación de Fomento de la Producción (Production Promotion Corporation, CORFO) and the Servicio de Cooperación Técnica (Technical Cooperation Service, SERCOTEC) with substantial operational autonomy.

CORFO's mission is to promote investment, entrepreneurship, innovation, and competitiveness. Established in 1939 with the mandate to implement the country's industrial policy, the agency manages a series of investment and R&D incentives, as well as a credit guarantee fund open to all classes of enterprises. CORFO is governed by a collegial body chaired by the Minister of Economy, Development, and Tourism, and composed of representatives from other ministries and two independent members nominated by the President of the Republic. The agency has a total staff of over 1000 and offices across the country.

SERCOTEC, established in 1952, has a mission to provide training and technical assistance programmes to micro and small enterprises and new entrepreneurs. Like CORFO, it has a network of regional offices, and its total staff consists of 240 units. Both agencies enjoy significant operational autonomy and receive adequate funding. Additionally, CORFO has its own monitoring and evaluation department.

In addition to well-defined mandates for policy formulation and oversight, the country has demonstrated effective practices in public-private consultations and has implemented measures to reduce labour and enterprise informality. This commitment is reflected in its overall score for the SME Institutional Framework dimension, which stands at 4.38.

Chile's SME definition which scores 4.5 has been established by Law 20.416 and adopted in 2010. This definition encompasses micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises and relies on two parameters: annual sales and employment. Sales values are expressed in unidades de fomento (support units), an accounting unit adjusted in line with inflation. The SME definition is widely used throughout the public administration.

In the Strategic Planning, Policy Design, and Coordination sub-dimension Chile's performance remains robust, with a score of 4.56. The mandate for SME policy is assigned to the Ministry of Economy, Development, and Tourism, specifically to the Directorate for Small Enterprises within the Sub-secretariat for the Economy as outlined in the 2010 Law on SMEs. The same law also established the Consejo Nacional Consultivo de la Empresa de Menor Tamaño (National Consultative Committee for Small Scale Enterprises), composed of the seven most representative trade associations in the country, together with representatives of local governments (municipalities), higher education institutions, and non-governmental entities (NGOs) with a mission to promote entrepreneurship.

The strategic directions of SME policy are incorporated in the Chile Apoya Plan 2022-2023, which covers the recovery phase from the economic crisis generated by the COVID-19 pandemic. The plan, developed in collaboration with the private sector, is in its final implementation phase. Simultaneously, a Strategic Development Plan for SMEs has been in the works since 2023. Developed in partnership with the trade associations comprising the Advisory Council of Smaller Companies, this initiative aims to establish consensus on strategic objectives guiding the design and execution of public policies, fostering the sustained growth of SMEs over the medium and long term.

The Ministry of Economy, Development, and Tourism has identified digitalisation as a key priority, alongside the enhancement of services for entrepreneurs and investors provided by the two main implementation agencies, CORFO and SERCOTEC, and the registration of informal enterprises. The Ministry, in collaboration with CORFO and SERCOTEC, has recently launched a programme called Digitaliza tu PyME which seeks to promote digital transformation in SMEs and reduce the digitalisation gap between large and small-scale enterprises.

Furthermore, Chile has a well-established practice of Public-Private Consultations (PPCs), as reflected in its score of 4.33 for this sub-dimension. The law recommends that public deliberations related to the introduction of new legislative acts, policy plans, and programmes should undergo public consultations. Typically, a period of 15 days is allocated for public consultations, and each ministry has its own digital consultation platform.

The Consejo Nacional Consultivo de la Empresa de Menor Tamaño (National Consultative Committee for Small Scale Enterprises) serves as the primary consultation channel for SMEs. Chaired by the Minister of Economy, Development, and Tourism, the council meets several times per year, and private sector representatives have the authority to propose legal acts and policy measures for discussion.

Finally, for the sub-dimension of measures to reduce informality, Chile receives a score of 3.94. Despite a significant growth in employment and business opportunities over the last decade, labour and enterprise informality remains high. In 2021, it was estimated that one in four jobs were informal. The government has prioritised the reduction of labour and enterprise informality and has implemented various measures. These include the strengthening of the Registro de Empresas y Sociedades plataform, aimed at simplifying company registration, PyME Ágil to reduce administrative burdens on small-scale enterprises and expedite the issuance of local business licenses, and the programme Formalízate implemented by SERCOTEC, which is a competitive fund that supports the formalisation and start-up of new businesses with the opportunity to participate in the market, financing a work plan aimed at implementing a business project. This is complemented by workshops on formalisation conducted by the Centros de Desarrollo de Negocios (Business Development Centres) to encourage the registration of informal enterprises.

The way forward

Finalise the elaboration and approval of the new SME strategic development plan, incorporating advanced monitoring and evaluation mechanisms. Additionally, integrate policy actions to support SME digital transformation within the framework of the new strategic development plan.

Ensure ongoing consultations with representatives of young entrepreneurs and start-ups, and design support measures implemented by SERCOTEC and CORFO to encompass all types of enterprises with growth potential.

Evaluate the measures introduced to reduce informality, assess their impact over time, and draw lessons for the next policy phase.

Dimension 2. Operational environment and simplification of procedures

The operational environment for SMEs in Chile is reasonably functional, with the country obtaining a score of 3.89, the highest among the assessed Latin American countries. Procedures are relatively simple, and the administrative burden is lighter than in other Latin American countries. Chile is making progress in the application of Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA) and in the provision of government services. Although procedures for filing and paying taxes remain relatively complex, a comprehensive tax reform is under implementation. Currently, Chile does not have a medium-term legislative simplification and regulatory reform plan in place but has adopted a case-by-case approach.

The country began taking steps to introduce the use of RIA in 2017, with the issuance of Presidential Instructive No. 2. This directive instructed economic ministries to conduct RIAs focusing on the impact of new legislative or regulatory acts on productivity during the approval process. The methodology, called Productivity Impact Assessment, was in line with standard RIA methodologies.

In 2019, Presidential Instructive No. 3 further promoted the application of RIA, and a RIA manual was developed by the General Secretariat of the Presidency (SEGPRES), the body responsible for supervising RIA application. While RIA is not yet systematically applied, there is a legal obligation to conduct RIAs for all major legal and regulatory acts, and all RIA reports are made public. However, there is no specific RIA SME test requirement.

Law No. 20.416, approved in 2010, establishes that all laws and regulations affecting SMEs must be subject to a simple impact evaluation. These changes are reflected in Chile's score of 4.00 for the Legislative Simplification and Regulatory Impact Analysis sub-dimension, which is higher than its performance in the 2019 assessment.

Furthermore, the company registration process in Chile is relatively well-structured, with a score of 4.20. The new enterprise receives a single identification number issued by the tax administration, the Rol Único Tributario (Unique Tax Number, RUT), valid for all interactions with the public administration. One-Stop-Shops are in place, and it is possible to conduct the company registration procedures online through the Registro de Empresas y Sociedades platform. Following a recent evaluation, company registration procedures have been further simplified.

In the sub-dimension of ease of filing taxes, Chile obtains a score of 3.22. SMEs in Chile have to deal with a relatively complex tax regime. While the number of tax payments per year and the tax and social contribution on total profits are below the OECD average, the number of hours for tax filing and paying taxes in a year (256) is significantly higher than the OECD average (158.8).

Nevertheless, a comprehensive tax reform is under implementation. Among other measures, it includes the introduction of a VAT regime on the sale of services. The reform maintains a special tax regime for SMEs and establishes a new tax regime for startups and for enterprises that go through the formalisation process, with incentives to facilitate the transition from the special SME tax regime to the standard corporate tax regime.

Chile has started to develop e-government (score: 4.20) services with the launch of the Digital Agenda 2020 in 2015. The policy direction for the digitalisation of government services has been set by Ley N°21.180 de Transformación Digital del Estado (Digital Transformation of the State). A particular focus has been assigned to promote interoperability across the data banks managed by different public administrations. The function of policy coordination is performed by the Digital Government Division of SEGPRES.

The range of e-government services is evolving and currently covers tax-filing, data reporting, and company registration procedures. Assistance in the use of e-government by SMEs and to promote digital transformation is provided by the platform Digitaliza tu PyME.

The way forward

Undertake regulatory reform in areas where it exhibits relative weaknesses. To develop a focused regulatory reform and legislative simplification agenda, an in-depth assessment of the business environment should be conducted, utilising methodologies such as the OECD regulatory reform tools.

Consider formally implementing an SME RIA test to better assess the impact of new legislation and regulations on different categories of SMEs.

Complete the implementation of the tax reform and monitor the effective tax rate imposed on different types of SMEs as a result of the reform.

Dimension 3. Access to finance

Chile scores 3.34 in the Access to Finance dimension, slightly above the regional average. In the Legal Framework sub-dimension, Chile achieves a score of 3.28, standing out for its solid development in asset registration and securities market regulation. However, it shows lower performance in the area of guarantees for SMEs. The country has advanced regulations and institutionalisation concerning the registration of tangible and intangible assets, with an accessible online registry system for the public and an online registry of movable property rights. However, movable property as collateral is accepted only by some banks or large borrowers.

Regarding the securities market, there are regulations for SMEs and government provisions to facilitate compliance with listing requirements. However, certain types of securities offerings are not considered public and are therefore exempt from certain information and oversight obligations. Nevertheless, the absence of a specific securities market for low-capitalisation SMEs negatively impacts this aspect. Moreover, one of the challenges facing Chile in this area relates to the terms of guarantees required for medium-term loans aimed at SMEs. The high percentage of required collateral represents a significant obstacle for these enterprises.

Chile ranks fifth in the alternative sources of financing indicator, scoring 4.49, distinguished by its robust framework covering all recommended elements. The country offers a wide range of competitive and diversified financial products, with specific support programmes for SMEs seeking international expansion.

Among these programmes are coverage for bank loans to exporters, such as CORFO's COBEX, operated by both banking and non-banking institutions. Also relevant are refinancing programmes, managed by non-banking financial institutions, setting limits on interest rates for factoring.

The Fondo de Garantía para Pequeños Empresarios (Small Business Guarantee Fund, FOGAPE) stands out, providing bank guarantees to facilitate access to credit for small businesses with limitations on their credit lines or lacking the collateral required by commercial banks. Furthermore, the granting of digital financing with digital guarantees is promoted.

In addition to these initiatives to improve access to traditional banking, Chile has a microfinance system that includes nationwide institutions and a variety of alternative asset-based financing sources, crowdfunding, and private equity investment tools. The Fintech Law (Law No. 21,521, 2022) is a prominent example in this field, promoting competition and financial inclusion through innovation and technology in the provision of financial services.

Chile leads in financial education for SMEs with a score of 3.75 points. The country has conducted financial capability surveys in collaboration with CAF and the OECD, as well as financial literacy assessments among 15-year-olds as part of OECD's PISA evaluations.

The country also has a Estrategia Nacional de Educación Financiera (National Financial Education Strategy, ENEF) approved at the end of 2016. The ENEF includes action plans for financial education programmes for SMEs and entrepreneurs, with institutions such as CORFO, the Servicio Nacional del Consumidor (National Consumer Service, SERNAC), and BancoEstado offering comprehensive programmes covering accounting modules, business planning, and access to financing information. Financial education is included in the secondary school curriculum as a mandatory subject for all students, and training courses are provided for teachers. The Comisión del Mercado Financiero (Financial Market Commission, CMF) has established guidelines on financial education for supervised entities, aligned with international best practices.

Chile shows a significant lag in public policies related to corporate bankruptcy and insolvency compared to other countries in the Pacific Alliance regional bloc, with a score of 1.83 in LA9. Although it has a regulatory framework and procedures for insolvent companies, these need further development to align with international standards. Key areas for improvement include the implementation of early warning systems and the facilitation of less onerous out-of-court settlements. Additionally, existing laws do not apply to state-owned enterprises (SOEs).

Finally, while the legal framework for secured transactions exists, it has opportunities for improvement. For instance, allowing secured creditors the ability to seize their collateral after reorganisation and ensuring that creditor consent is obtained for reorganisation processes are crucial steps. These improvements could strengthen the business environment and improve Chile's standing in this area.

The way forward

Promote that movable assets are accepted and used as collateral by the entire financial system. Review downward the weighting of collateral for medium-term loans to SMEs.

Promote a separate securities section or market for SMEs with low capitalisation.

Design and implement a National Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS) and establish governance and coordination mechanisms between the NFIS and the ENEF.

Periodically conduct a survey to measure SMEs' financial capabilities in order to have timely information on their needs for effective programme design.

Strengthen the existing regulatory framework related to bankruptcy and insolvency policies including the development of early warning mechanisms.

Promote other out-of-court mechanisms for bankruptcy cases that can be more cost and time efficient for the parties.

Establish an automatic mechanism, which removes companies and individuals from official bankruptcy and insolvency registers when the situation is resolved, in line with international best practices.

Dimension 4. SME development services and public procurement

Chile is the top performer in this dimension, with a score of 4.75. The highest performance is registered in the business development services sub-dimension (4.80), and public procurement services (4.80), followed by entrepreneurial development services (4.67). Back in the 2019 evaluation, Chile also registered the highest performance in this dimension, which points to a strong SME policy consistency over the years.

The delivery of business development services for SMEs is contemplated in the National Programme of Government 2022-2026, which prioritises the economic recovery from the pandemic and the development of the capacities and competitiveness of SMEs and co-operatives. Key areas of action identified include access to finance, markets, and innovation, improving enterprise capabilities, supporting co-operatives, and supporting workers. The programme, however, does not provide details on specific measures, targets, and responsibilities for the provision of BDS to address those areas, at least in its publicly available version. The publication of such details is necessary to understand the priorities, actions, and targets of SME policy in general and BDS in particular, as well as how SME policy objectives link to the wider national development and transformation ambitions.

As in 2019, various agencies are devoted to the support of different types of SMEs, including CORFO for innovative and high-potential businesses, SERCOTEC for the provision of training and financing of more traditional businesses, the Instituto de Desarrollo Agropecuario (Institute for Agricultural Development, INDAP) for agricultural businesses, and Pro-Chile for internationally oriented firms. Those agencies also provide targeted services for entrepreneurs and start-ups. For example, CORFO sponsors incubators, accelerators, and technology centres in collaboration with private sector actors whereas SERCOTEC works through private consultants (Agentes operadores) in the provision of its programmes. This contributes to the development of a market for BDS in the private sector and the long-term sustainability of the support, as opposed to models purely dependent on state institutions and funded by public resources, debt or international aid. In addition, Chile has a functional system to track the participation or the reach of beneficiaries from its programmes and provides general information for entrepreneurs on how to create a firm, what procedures and authorities need to grant approvals, and what private organisations provide support to entrepreneurs. Other measures aimed at facilitating SME participation in public procurement include a mechanism allowing for the simplification of low-value tenders (Compra Ágil) and a mandate to comply with strict payment deadlines of no more than 30 days, reflected in Law 21.131, which helps to prevent the unlawful financing of government activities through SMEs.

As noted above, Chile continues to have a performing public procurement system facilitating the participation of SMEs in this important market. As in the 2019 edition of the SME PI, the legal framework for public procurement is provided by the Public Procurement Law (Ley de Compras Públicas) 19.886 of 2003, which establishes the rules and procedures for the procurement of goods, services, and works by public entities. The law is administered by the Directorate of Procurement and Public Works (Dirección de Compras y Contratación Pública or Chile Compra) and foresees the possibility, but not the obligation, to break tenders that surpass a given value into smaller lots and hence facilitate SME participation in bidding processes. The law also allows for the formation of consortia of SMEs to participate in joint bidding but does not permit or mandate set-asides or quotas for SMEs in public procurement. In mid-2023, Law No. 21.634 was enacted, modernising Law No. 19.886 and other legal frameworks with the objective to enhance the quality of public expenditure, elevate standards of integrity and transparency, and introduce principles of circular economy. This modernisation also aimed to promote the participation of SMEs in public procurement by facilitating agreements with regional organisations to enhance SMEs' access to public procurement processes, as well as local suppliers and women-led businesses. It sought to enhance differentiated pricing for SMEs' entry into the Supplier Registry in Compra Ágil and strengthen and formalise the concept of Unión Temporal de Proveedores (Temporary Union of Suppliers, UTP) as a mechanism for joint participation in tenders.

In addition, Chile does not impose pre-qualification requirements for firms to participate in public procurement (e.g., minimum levels of revenue, guarantees, and deposits to participate in tenders, qualifications, etc.). According to the government responses for this assessment, the approach in Chile is to actively favour SME involvement in public procurement, and to remove any barriers that may prevent their participation due to their size. Chile undertook an assessment of the main barriers facing small firms in public procurement and devised measures to address those barriers, which include the large size of contracts, a limited knowledge of procedures, a lack of capacity and time to prepare bids, excessive bureaucracy, late payments, high qualification requirements, etc.

Chile has a fully-fledged electronic procurement system through Chilecompra.cl, which comprises the publication of all relevant information and the management of the different stages of the procurement process. It also includes information on how to use the system and comprises a registry of suppliers that facilitates the participation of bidders in various processes. The use of the electronic platform is mandatory for all agencies and processes.

Overall, Chile displays a strong performance in this dimension, with a diversity of services and initiatives for the development of SMEs, entrepreneurs, start-ups, and their participation in public procurement opportunities. It is not very clear, however, how the different measures under this dimension relate to the National Development Programme 2022-2026 and its broad objectives including the recovery from the pandemic and the achievement of a sustainable and inclusive development model.

The way forward

Explicitly identify how BDS and services for entrepreneurs link to the National Government Programme 2022-26 and how specific actions and responsible actors operate to advance the objectives stated in the Programme.

The above includes specifying how key agencies and initiatives such as CORFO, SERCOTEC, Start-Up Chile, Pro-Chile, and others, advance the national strategic objectives on SMEs and entrepreneurship.

Dimension 5. Innovation and technology

Chile has an overall score of 4.47 in the Innovation and Technology dimension. Chile’s strong performance is driven predominantly by excellent financing supports for innovation, as well as its wider network of support services and innovation infrastructure.

There is a large number of entities involved in the delivery of innovation supports in Chile, including CORFO under the Ministry of Economy, Development and Tourism, the Chilean Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (National Agency for Research and Development, ANID) under the Ministry of Science, Technology, Knowledge, and Innovation, and the Fundación para la Innovación Agraria (Foundation for Agricultural Innovation, FIA) under the Ministry of Agriculture. This amplifies the importance of having an institutional framework with structures that facilitate inter-governmental co-ordination. This is achieved in Chile through the inter-ministerial committee of the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología, Conocimiento e Innovación para el Desarrollo (National Council of Science, Technology, Knowledge, and Innovation for Development, CTCI). The CTCI’s 2022 National Strategy of Science, Technology, Knowledge, and Innovation for Development identifies the need for technological upgrading and digitalisation within SMEs, and it presents a number of initiatives to promote SME innovation. Importantly, the private sector was consulted during the development of the strategy, as stipulated by Law No. 20 500, and there are formal records of the inputs received during these consultations. However, the strategy does not include measurable targets, which inhibits future monitoring and evaluation efforts to determine its effectiveness. It also lacks implementation timelines for specific actions. These factors contribute to a score of 4.34 in the Institutional Framework sub-dimension.

Furthermore, Chile excels in the provision of supports for SME innovation, with a score of 4.35 in the Support Services sub-dimension. CORFO is active in this area, including through the promotion of the CTeC Technology Park and the operation of the Start-Up Chile public business accelerator. CORFO also hosts a registry of incubators for innovative start-ups on its website. Again, stakeholder consultation is a strength for Chile, with SMEs having been formally engaged through consultations and surveys in order to identify their innovation policy needs.

Chile has a score of 4.72 in the Financing for Innovation, which is by some margin the highest in the LAC region. A large number of financing supports are available for SMEs to help them to innovate, including grants, vouchers, and co-financing instruments implemented by CORFO via InnovaChile. There are also financing programmes that target specific groups, including the Expande programme for high-growth enterprises and the Capital Abeja Emprende programme, which targets women. R&D tax credits are also available, with a high uptake among SMEs. Chile also conducts regular monitoring and independent impact evaluations of its financing supports for innovation, which sets it apart from most other countries in the LAC region. One potential gap in the policy support framework is the absence of demand-side measures to support innovative SMEs. In other countries, public procurement for innovation schemes have been an effective tool for stimulating demand for innovative SMEs’ products or services.

The way forward

Going forwards, Chile could consider:

Introducing a public procurement for innovation programme, to provide another source of potential funding for innovative firms.

Elaborating the innovation strategy to include further detail on proposed policy actions, with responsible implementation entities, timelines, objectives, key performance indicators, and targets.

Ensuring the CTCI is represented by all public entities with responsibility for the design or delivery of innovation policies.

Dimension 6. Productive transformation

Chile obtains the highest score among the LA9 countries in the Productive Transformation dimension, reaching a score of 4.52. This notable performance is propelled by the SME-focused axis of the Productivity Agenda unveiled in 2023. Chile registers an improvement in the scores of the first two-sub-dimensions and a decline in the integration into global value chains sub-dimension compared to its 2019 results. This decline is primarily due to methodological changes detailed in the assessment's methodology section, but which also highlights a great opportunity to improve monitoring and evaluation systems.

Chile's Productivity Agenda stands as a well-coordinated collaborative initiative involving the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Economy, Development and Tourism, and the Ministry of Labour and Social Security, in conjunction with various business associations and the country's primary workers' organisation. This joint effort materialises through the implementation of 40 measures encompassed in nine axes, one of which prioritises the productivity of SMEs. This prioritisation involves promoting measures to streamline administrative processes the redesigning of the Digitaliza tu PyME programme and the broadening of the PyME Ágil platform. Chile's commitment to creating strategies to enhance productivity is reflected in its 4.75 score for the first sub-dimension, surpassing the regional average and their performance in the 2019 assessment (4.52).

Chile excels in the measures to improve productive associations sub-dimension boasting a score of 4.84. This is attributed to the ongoing implementation of the Programas Estratégicos de Especialización Inteligente led by CORFO, which were in their initial phase of implementation at the time of the 2019 assessment. These programmes emerged from a collaborative effort between the public and private sectors and feature a sophisticated and multi-faceted monitoring and evaluation system based on IADB recommendations. They leverage CORFO's programmatic offerings to stimulate the creation of networks, promote innovation, and enhance competitiveness in enterprises. Furthermore, since 2015, SERCOTEC, drawing inspiration from international experiences and fostering strong public-private coordination tailored to the Chilean context, has spearheaded the Strengthening of the Programa de Barrios Comerciales. The primary objective is to enhance the commercial offer and urban environment of commercial neighbourhood through collaborative efforts. This involves providing technical support and financing for investment aimed at reinforcing associativity and improving the commercial offerings of SMEs. The programme seeks to elevate the identity and communication of the neighbourhood, enhancing safety, sustainability, and urban infrastructure. Since its inception, the programme has made significant strides, reaching a third of the country's municipalities.

There is some room for improvement with respect to the Integration into Global Value Chains sub-dimension, where Chile scored slightly lower at 4.12. While Chile demonstrates commendable performance in the thematic blocks of Planning and Design, coupled with the implementation of this sub-dimension, these achievements are somewhat overshadowed by the comparatively limited efforts of its new programme in Monitoring and Evaluation. Chile's well-established and long-standing Programa de Desarrollo de Provedores (Supplier Development Programme, PDP) serves as an exemplary model with robust monitoring and evaluation frameworks. Meanwhile, recent endeavours to promote support programmes for the integration of SMEs into global value chains, including the pilot programme Pymes Globales, showcase Chile's commitment to evolving strategies. Initiated by SERCOTEC and building on the 2021 version Orgullo Chileno, this programme aims to propel SMEs to expand their sales channels and take initial steps towards internationalisation. It offers a 10-month advisory and specialised technical assistance programme to position the company in international marketplaces, accompanied by co-financing for promotional materials. While the programme is only in its second call for applications, Chile's score could be enhanced by reinforcing monitoring and evaluation practices and conducting reliable assessments of the impacts of the Pymes Globales programme.

The way forward

Chile has showcased notable progress since 2019, but there is room for further improvement in its monitoring mechanisms. Strengthening existing efforts could involve establishing KPIs with well-defined lines of action and objectives. This enhancement is particularly pertinent when assessing the impacts of initiatives like the Pymes Globales programme.

Dimension 7. Access to market and internationalisation of SMEs

Chile has achieved a notable score of 4.57 in the Access to Markets and Internationalisation dimension, reflecting its efforts to boost the foreign trade of Chilean SMEs through well-formulated policies and specific measures on issues such as trade facilitation, e-commerce, and quality standards.

Regarding internationalisation policies and programmes, Chile has scored 5.0, indicating satisfactory compliance in the design, implementation, and evaluation of programmes. The agency ProChile, responsible for promoting exports and investments, has played a crucial role in this aspect since its autonomy in 2019. Through ProChile, policies aimed at supporting Chilean companies in promoting and diversifying their exports are coordinated and implemented, with special attention to exporting SMEs and priority sectors such as audiovisual arts, energy efficiency, and seafood.

ProChile programmes, such as "ProChile a tu medida" and "Global X", are designed to enhance competitiveness and accelerate SME participation in the international market. Additionally, training and financing opportunities are offered to enhance international businesses, with competitive funds and specific programmes according to the sector and stage of the companies in their export process.

In terms of promotion and financing to boost international businesses, both ProChile and CORFO offer a wide range of programmes and activities to support the internationalisation of Chilean companies. ProChile provides funds for activities such as international fairs, trade missions, and establishing offices abroad. Meanwhile, CORFO provides financing through programmes such as COBEX, Associative Network, and CORFO SMEs Credit, facilitating credit operations, leasing, and factoring. These initiatives aim to boost the success of companies in international markets.

In 2022, ProChile achieved significant coverage of continuous and intermittent exporters, generating a significant impact on employment. Although activities are monitored, there is still lacking information about the impact of implemented programmes. ProChile has also established feedback mechanisms from the private sector, including satisfaction surveys and regional export councils, demonstrating a comprehensive approach to the needs and concerns of Chilean companies in the international arena.

In the trade facilitation sub-dimension, Chile stands out with a score of 4.73, surpassing the LA9 average. ProChile provides export guides called "Exporta paso a paso," while the Subsecretaría de Relaciones Económicas Internacionales (Undersecretariat for International Economic Relations, SUBREI) develops export and import manuals updated according to current International Trade Terms. Additionally, the National Customs Authority, along with ProChile, offers workshops on the benefits and procedures of Authorised Economic Operator (AEO) certification. The single window "SICEX" ensures interoperability of agencies involved in the import and export process, and Chile benefits from its membership in the Inter-American Network of Single Foreign Trade Windows of the IADB (REDVUCE). Although Chile generally exceeds or matches the LA9 average performance in Trade Facilitation Indicators (TFI), it is below the overall OECD average performance in all TFI indicators (1.46 vs. 1.67, respectively), especially in appeal procedures and cooperation among border agencies.

In the e-commerce sub-dimension, Chile scored 4.17. In 2022, the "Digital Agenda 2035" was launched, addressing seven fundamental axes for long-term digital development. Although previous digital agendas were implemented, they lacked a solid and continuous strategic framework beyond presidential cycles. Although there is no website to monitor its implementation, data from the Santiago Chamber of Commerce indicates that 50% of SMEs used e-commerce in 2023, representing 37% of their total sales.

In January 2021, the Electronic Commerce Regulation was approved to strengthen transparency and quality of information on e-commerce platforms. Additionally, the Consumer Rights Law establishes a regulatory framework for consumer protection online. On the other hand, ProChile implements the "E-commerce Export" programme to boost sales and exports through digital channels. It offers guidance, training, and consultancy to companies to enter and position themselves in key international digital channels. This programme includes market research, training on marketplaces, logistics, and digital marketing, and an implementation stage with the support of an e-commerce accelerator.

In the quality standards sub-dimension, Chile scored 4.31. CORFO administers the Quality Promotion Programme (FOCAL), which supports the incorporation of management standards in SMEs. In 2022, this programme supported 87 companies with a disbursement exceeding USD 300 thousand. The Chilean Agency for Food Quality and Safety also assists SMEs in creating and reviewing quality standards, subsidising the application of these norms.

ProChile's training programmes also promote product improvement and management protocols. However, monitoring and evaluation efforts in this area are limited to counting the number of beneficiaries and the budget invested, without performance or impact indicators currently available. Private sector consultations for policy formulation are conducted through specific business associations.

Finally, in the sub-dimension on the benefits of LAC integration, Chile scored 3.91 points. The Multilateral Regional Integration Division of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs coordinates the country's foreign policy. Its participation in the Pacific Alliance (PA) stands out, where it is part of the "SME Technical Group," focusing on projects on trade facilitation, business development, and public procurement. During the XIII AP Summit in 2018, the Global Value Chains and Productive Linkages Committee (CCGVyEP) was created, aiming to promote productive linkages among member countries. Through the committee, business matchmaking platforms are promoted, such as CORFO Connect.

The way forward

To strengthen Chile's performance in dimension 7, Chile could consider:

Improving the monitoring and evaluation of policies implemented in the medium- and long-term. This will allow better adjustments to programmes, as well as better design of new ones. In addition, the publication of these evaluations could serve as a guideline for each programme.

Expand programmes and activities focused on scaling up SME operations through digital channels. This will favour the growth and consolidation of local and cross-border e-commerce.

Generate greater dissemination of the benefits available to SMEs in the various programmes and policies to support internationalisation. This includes digital platforms, business intelligence, logistics, cross-border e-commerce, trade fairs, among others.

Move forward with the implementation of programmes for the certification of a greater number of SMEs as AEO.

Enhance the benefits of sub-regional integration through trade promotion and SME internationalisation programmes, standardised, and with interoperability of the different export promotion agencies of the Pacific Alliance.

Dimension 8. Digitalisation

Chile achieves an overall score of 4.62 in the Digitalisation dimension. The driving force behind Chile's robust performance lies primarily in its outstanding National Digitalisation Strategy, coupled with its broadband connectivity infrastructure and digital skills initiatives.

Chile is rapidly advancing its digital landscape through a comprehensive National Digitalisation Strategy (NDS), serving as a blueprint to leverage technology for the betterment of citizens' lives. The NDS places significant emphasis on supporting small businesses, streamlining government services, and providing digital literacy education. It underscores Chile's commitment to fostering an inclusive digital society, highlighting the importance of digital governance to ensure accessibility to government services irrespective of location or background. By implementing efficient digital solutions, Chile enhances the overall quality of public services, drives economic growth, and empowers its people. These factors contribute to an impressive score of 4.80 in the National Digitalisation Strategy sub-dimension, surpassing the regional average.

Chile excels in providing digital infrastructure, earning a score of 4.33 in the Broadband Connection sub-dimension. Through its Zero Digital Divide Plan, Chile is ambitiously working to bridge the digital gap, ensuring even remote areas have internet access to promote social inclusion and economic development. The government invests in building a robust digital infrastructure, facilitating seamless connectivity across the country. Additionally, recognising the importance of reliable and affordable internet access in education, Chile provides schools and educational institutions with high-speed internet. This initiative enriches the learning experience and prepares students for the digital future.

In the Digital Skills sub-dimension, Chile boasts a score of 4.73. Empowering citizens with digital skills are a cornerstone of Chile's digital transformation efforts. Schools nationwide integrate technology into their curriculum, equipping students with essential digital skills from an early age. Adult education programmes help older generations adapt to the digital world, ensuring broad participation in the digital economy. Chile's focus on digital education extends beyond formal settings, with the government collaborating with non-profit organisations to organise workshops and training sessions in local communities. These initiatives aim to enhance digital literacy among adults, enabling them to access online services, apply for jobs, and connect with others in the digital sphere.

At the same time, the Digitaliza tu Pyme programme is a noteworthy example of Chile's efforts to enhance and assess the digital maturity of SMEs in the country. The programme provides a diverse array of events, workshops, training sessions, and tools. It also establishes a network of partners aimed at fostering the adoption of digital technologies, particularly focusing on SMEs.

The way forward

Going forwards, Chile could consider:

Establishing a framework for continuous feedback and improvement in digital skills policies, ensuring they are aligned with the evolving needs of SMEs.

Encouraging public-private partnerships to enhance digital infrastructure, with a focus on supporting SMEs in both urban and rural areas.

References

[5] Bastidas, F. and R. Vergara (2023), “Tendencias en el Mercado Laboral postpandemia en Chile”, Punto de Referencias. Economía y Políticas Públicas. No. 674, septiembre, pp. 1-21, https://www.cepchile.cl/investigacion/tendencias-en-el-mercado-laboral-postpandemia-en-chile/ (accessed on 11 March 2024).

[4] CBC (2023), Informe de Política Monteria: diciembre 2023, Management of Institutional Affairs Division of the Central Bank of Chile, https://www.bcentral.cl/contenido/-/detalle/informe-de-politica-monetaria-diciembre-2023.

[8] Ministry of Economy, Development and Tourism Chile (2023), Pacto Fiscal incluye nuevas medidas para Pymes: ruta del emprendimiento y monotributo, https://www.economia.gob.cl/2023/08/07/pacto-fiscal-incluye-nuevas-medidas-para-pymes-ruta-del-emprendimiento-y-monotributo.htm#:~:text=La%20llamada%20%22Ruta%20del%20Emprendimiento,Pymes%20hacia%20el%20r%C3%A9gimen%20general. (accessed on 11 March 2024).

[3] OECD (2024), OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2024 Issue 1: Preliminary version,, OECD Publishing, https://doi.org/10.1787/69a0c310-en.

[1] OECD (2024), Real GDP forecast (indicator), https://doi.org/10.1787/1f84150b-en (accessed on 13 March 2024).

[6] OECD (2022), Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2022: An OECD Scoreboard, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e9073a0f-en.

[7] OECD (2022), Financing SMEs and Entrepreneurs 2022: An OECD Scoreboard, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e9073a0f-en.

[9] SUBREI (n.d.), Chile y comercio exterior, https://www.subrei.gob.cl/.

[2] World Bank (2022), Chile Overview, https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/chile/overview.